?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Objectives

The objective of this study was to assess the outcomes of the use of electrodiagnosis in the diagnosis and management of discrete nerve injuries in patients with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).

Design

This study is a secondary retrospective cohort analysis of patients diagnosed with CRPS from a single outpatient physical medicine and rehabilitation clinic and included all patients who had abnormal electrodiagnostic findings, in addition to CRPS.

Results

Sixty patients of 248 diagnosed with CRPS underwent electrodiagnosis, 41 of whom had abnormal electrodiagnostic findings indicating a discrete nerve injury. Only 51% of the 41 referrals had indicated the suspicion of a nerve injury. Nearly all patients had undergone physiotherapy. Forty-one percent responded to treatment with oral prednisone alone, 54% had a functional improvement after a combination of treatments including corticosteroids, and 5% improved with treatments that did not involve corticosteroids. Surgical interventions for nerve injuries were required for 34% of patients in the cohort. All surgeries involved the median or ulnar nerve, with the exception of one fibular nerve. After treatment, 39 of 41 patients had functional recoveries or better.

Conclusions

Electrodiagnosis can inform diagnosis of nerve injury and direct intervention including the need for surgical intervention. Electrodiagnosis should be considered for patients with initial signs of concomitant discrete nerve injury or with CRPS who are not responding to treatments because a nerve injury may be underlying.

What is Known

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is a poorly understood pain condition. CRPS has been divided into two subtypes, the second subtype involves a discrete nerve injury with pain that extends beyond the territory of the nerve injury.

What is New

We observed that nerve injuries that may require surgical intervention are diagnosed just over half of the time upon initial assessment in patients with suspected CRPS. We observed that nerve injuries frequently required specifically directed interventions in place of or in conjunction with CRPS treatments. We suggest that electrodiagnosis is an important part of the triage protocol for CRPS II to reveal discrete nerve injuries that may be hidden. We recommend that electrodiagnosis be considered for patients with initial signs of concomitant discrete nerve injury or for CRPS patients who do not improve with medical therapies.

Plain Language Summary

CRPS typically occurs after an injury or inciting event and can be accompanied by severe pain, sensitivity, swelling, changes in the color of the skin, changes in the texture of the skin, changes in hair and nail growth, weakness, muscle wasting, range of motion reduction, and temperature changes in the affected area. Little is known about type II CRPS, which may present with all of the same signs and symptoms as above but with damage to a nerve in the area. This study examined cases of CRPS where patients had electrodiagnostic findings that suggested a nerve injury. We found that the referring physicians reported nerve injuries in just over half of the cases. Oral prednisone was often the chosen treatment for these patients, although many required additional treatments, including surgery, to address their nerve injury. We recommend that electrodiagnosis be considered for patients with CRPS who are not responding to corticosteroids because a nerve injury could be preventing CRPS symptoms from resolving. When the CRPS trigger was a trauma that likely simultaneously injured the nerve, patients needed to have surgery more frequently than those with atraumatic onsets.

RÉSUMÉ

Objectifs: L’objectif de cette étude était d’évaluer les résultats de l’utilisation de l’électrodiagnostic pour le diagnostic et la prise en charge des lésions nerveuses discrètes chez les patients souffrant du syndrome de la douleur régionale complexe (SDRC).

Devis: Cette étude est une analyse de cohorte rétrospective secondaire de patients ayant reçu un diagnostic de SDRC d’une seule clinique de médecine physique et de réadaptation ambulatoire et incluait tous les patients pour lesquels les résultats de l’électrodiagnostic étaient anormaux, en plus du SDRC.

Résultats: Soixante patients sur les 248 ayant reçu un diagnostic de SDRC ont subi un électrodiagnostic, parmi lesquels 41 ont obtenu des résultats anormaux indiquant une lésion nerveuse discrète. Il était indiqué qu’une lésion nerveuse était soupçonnée pour seulement 51 % des 41 références. Presque tous les patients avaient reçu des traitements de physiothérapie. Tandis que 41 % ont répondu au traitement par prednisone orale seule, 54 % ont présenté une amélioration fonctionnelle après une combinaison de traitements comprenant des corticostéroïdes, et 5 % ont présenté une amélioration avec des traitements qui n’impliquaient pas de corticostéroïdes. Des interventions chirurgicales pour les lésions nerveuses ont été nécessaires pour 34 % des patients de la cohorte. Toutes les chirurgies concernaient le nerf médian ou ulnaire, à l’exception d’un nerf fibulaire. Après le traitement, 39 des 41 patients ont connu des récupérations fonctionnelles ou mieux.

Conclusions: L’électrodiagnostic peut éclairer le diagnostic de lésion nerveuse et l’intervention directe, y compris la nécessité d’une intervention chirurgicale. L’électrodiagnostic doit être envisagé pour les patients présentant des signes initiaux de lésions nerveuses discrètes concomitantes ou qui sont atteints du SDRC mais ne répondent pas aux traitements parce qu’une lésion nerveuse peut être sous-jacente.

Ce qui est connu

Le syndrome douloureux régional complexe (SDRC) est une affection douloureuse mal comprise. Le SDRC a été divisé en deux sous-types, le deuxième sous-type implique une lésion nerveuse discrète avec une douleur qui s’étend au-delà du territoire de la lésion nerveuse.

Ce qui est nouveau

Nous avons observé que les lésions nerveuses pouvant nécessiter une intervention chirurgicale sont diagnostiquées un peu plus de la moitié du temps lors de l’évaluation initiale des patients chez lesquels on soupçonne un SDRC. Nous avons observé que les lésions nerveuses nécessitaient souvent des interventions spécifiquement dirigées à la place des traitements pour le SDRC ou en conjonction avec ceux-ci. Nous avançons que l’électrodiagnostic constitue une partie importante du protocole de triage pour le SDRC-II afin de révéler des lésions nerveuses discrètes qui peuvent être cachées. Nous recommandons que l’électrodiagnostic soit envisagé pour les patients présentant des signes initiaux de lésion nerveuse discrète concomitante ou pour les patients atteints du SDRC dont l’état ne s’améliore pas avec les traitements médicaux.

Résumé vulgarisé

Le SDRC survient généralement après une blessure ou un événement déclencheur et peut s’accompagner d’une douleur intense, de sensibilité, d’enflure, de changements dans la couleur et la texture de la peau, de changements dans la croissance des cheveux et des ongles, de faiblesse, d’une atrophie musculaire, d’une réduction de l’amplitude des mouvements et d’un changement de la température dans la région touchée. On sait peu de choses sur le SDRC de type II, qui peut se présenter avec tous les mêmes signes et symptômes que ci-dessus, mais avec des lésions nerveuses dans la région.

Cette étude a examiné des cas de SDRC où les résultats de l’électrodiagnostic des patients laissaient croire à une lésion nerveuse mineure. Nous avons constaté que les médecins référents signalaient des lésions nerveuses dans un peu plus de la moitié des cas. La prednisone orale était souvent le traitement choisi pour ces patients, bien qu’un grand nombre d’entre eux aient dû se soumettre à des traitements supplémentaires, y compris la chirurgie, pour traiter leur lésion nerveuse. Nous recommandons que l’électrodiagnostic soit envisagé pour les patients atteints de SDRC qui ne répondent pas aux corticostéroïdes parce qu’une lésion nerveuse pourrait empêcher les symptômes du SDRC de se résorber. Lorsque l’élément déclencheur du SDRC était un traumatisme ayant vraisemblablement endommagé le nerf en même temps, les patients ont dû subir une intervention chirurgicale plus fréquemment que ceux pour qui le déclenchement était d’origine atraumatique.

Introduction

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) remains a debated and poorly understood pain condition. CRPS may follow various inciting injuries, most commonly fractures of the distal upper extremity.Citation1–3 CRPS presents as a regional pain that is out of proportion to the inciting event, accompanied by allodynia, dysesthesia, temperature asymmetry, edema, and often decreased function.Citation4,Citation5 The International Association Study for the Pain (IASP) criteria (also known as the Budapest criteria) remain the most commonly used assessment and divides CRPS into two types: type I and type II. CRPS II is less common and presents similarly to CRPS I but is associated with discrete nerve damage.

CRPS II may not present as a territorial pain typical of neurological injuries. In the presence of overt trauma, such as a fracture, and its sequelae, physicians may not recognize a discrete neurologic injury and may not investigate for one. The regional involvement of CRPS that spreads beyond an expected joint or dermatome further adds to the diagnostic challenges, potentially hiding the presence of a discrete nerve injury ().Citation4 Clinicians must perform a neurological examination, electrodiagnostic studies, or another objective test to diagnose CRPS II.Citation4 Typically, practitioners forgo electrodiagnostic studies unless paresthesia, numbness, or autonomic dysfunction are present in addition to the CRPS signs and symptoms. Patient intolerance early on usually prevents the assessment. The early onset of swelling and edema, common in CRPS cases, may hide the tell-tale sign of atrophy in the distal limbs. Ideally, CRPS should be treated within months of onset to modify the disease process. Corticosteroids, such as oral prednisone, have been recommended and endorsed as first-line treatment for subacute CRPS because of their anti-inflammatory properties. Harden et al. opined that oral corticosteroids are the only anti-inflammatory drugs for which there is direct clinical trial evidence in CRPS (level 1 evidence).Citation6 Two recent review articles have supported their effectiveness in reducing CRPS symptoms.Citation7,Citation8

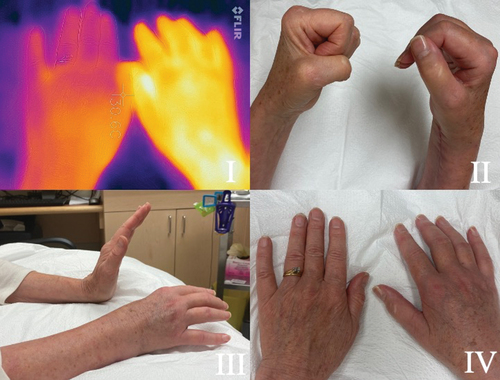

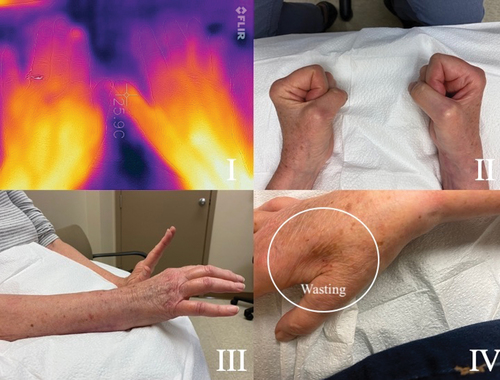

Figure 1. (a) A 64-year-old female presented two months after ORIF for a distal right radial and ulnar fracture. There is involvement of the wrist and all fingers. I. FLIR ONE imagery of the dorsal aspect of each hand shows temperature asymmetry. The affected side is notably warmer than the unaffected. A II,III, IV show the reduced range of motion and swelling of the joints. (b) After three weeks on prednisone. The temperature on FLIR imaging (1BI) , swelling and range of motion (1B II III) have improved. The wasting of the first dorsal interossei (FDI) (1B IV) and weak intrinsic muscles is now apparent. Nerve conductions reveal the ulnar nerve has a small amplitude of 3mV, with no slowing at the elbow. The ulnar sensory was normal. The EMG to the FDI showed florid denervation, with no motor units recruiting. The adductor digiti minimi had 2+ denervation with reduced polyphasic recruitment, while the flexor carpi ulnaris was normal. Ulnar nerve entrapment at the wrist was diagnosed. Ulnar nerve decompression was performed at the wrist. Full resolution of all symptoms was achieved.

Electrodiagnosis is not required for the Budapest criteria. This study evaluated the use of electrodiagnosis in a cohort of patients diagnosed with CRPS. The electrodiagnosis was used at the discretion of the treating physical medicine and rehabilitation physician to identify the presence of discrete nerve injuries when a nerve injury was suspected, to direct management of the CRPS. Nerve-specific treatments included corticosteroids for both CRPS type I and the neuritis of CRPS II as well as for surgical intervention.

Methods

The local research ethics board (Vancouver Island Health Authority; harmonized review with the University of Victoria and University of British Columbia) approved this retrospective chart review study (Protocol H21-01520) and issued a consent waiver.

Study Methodology

This study conforms to all Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines and reports the required information accordingly.Citation9 An International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code search of a single physiatrist’s electronic medical records identified any charts flagged for CRPS (causalgia) between May 2013 and September 2021. A second search identified any charts that included electrodiagnostic studies. describes the participant selection process. Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).Citation10

All charts identified by the ICD code searches were read in their entirety to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. The results of the electrodiagnostic studies in all charts that met the inclusion criteria were reviewed and findings were recorded by the study team. Data collected for the study included demographic information, date of injury and consultation, findings of nerve conduction studies (including electrodiagnosis), treatment(s), and outcome. Outcomes were assessed using the scale provided in .

Table 1. Criteria for assessing patient outcomes.

Some residual symptoms were likely a product of the CRPS inciting injury and not directly attributable to the CRPS itself; for example, stiffness with incomplete range of motion in the finger joints. In such instances, patients are not reported as having complete resolution despite the CRPS having resolved because of self-report of ongoing impairment.

Inclusion Criteria

Participants were included in this cohort study only if they had been clinically diagnosed with CRPS as per the Budapest criteria. Within this cohort, a smaller subset of patients was identified who had undergone electrodiagnosis and had findings indicative of a nerve injury, including peripheral neuropathies, plexopathies, or radiculopathies in the region affected by CRPS, coinciding temporally with their positive CRPS diagnosis.

Exclusion Criteria

Participants who had positive electrodiagnostic findings only in regions separate from their CRPS were excluded from the study. Participants whose diagnosis was changed from CRPS after further investigation were excluded from the study. Participants who underwent electrodiagnosis but had normal findings were excluded.

Results

The initial ICD code search yielded 286 charts for review: 248 were diagnosed with CRPS using the Budapest criteria; 60 patients underwent electrodiagnostic studies, and 19 had normal findings. The 41 abnormal studies fit the inclusion criteria (17 males, 24 females). This represents 17% of patients diagnosed with CRPS in the review. The 41 patients were naturally divided into three categories: the first two categories included those where the nerve injury was felt to be contributing or the cause of CRPS and there was either an identifiable traumatic injury or disease onset and those with an atraumatic, more gradual onset, and the third category included a small group of four in which the electrodiagnostic findings were felt to be of delayed onset and not contributing to the CRPS. Nearly all patients included in the study had attended physiotherapy or occupational therapy as part of their normal care.

Nerve Injury Coincided with CRPS Onset

This first category included 21 participants with electrodiagnostic findings that suggested that the nerve injury coincided with the CRPS inciting event such as an acute trauma that damaged the nerve or disease process. Sixteen of these 21 patients had injuries of the upper limb, 4 the lower limb, and 1 the cervical spine. The median time from the initial trauma to assessment in the clinic was 113 days (σ = 162.05; = 154.67; min = 5; max = 664). Ten participants in this category had fracture as their CRPS inciting event (48%). Other mechanisms included elective surgery, laceration, and infection. Each participant in this category’s presentation is summarized in .

Table 2. Patients whose CRPS onset coincided with the nerve injury’s presentations, treatments, and outcomes sorted by initial treatment, additional treatments, and outcome.

Electrodiagnostic findings for category 1 participants included neuropathies, plexopathies, and radiculopathies. The most frequently affected nerves were the median nerve (33%) and ulnar nerve (33%); these nerves were often both affected. Each category 1 patient’s electrodiagnosis is presented in . Nerve injuries were suspected or confirmed by the referring physician in 12 of 21 charts (57%).

Overall, 19 of the 21 participants had at least a functional recovery after all interventions (90%; 7 completely resolved, 12 mostly resolved). One participant did not return for follow-up and their outcome is unknown. One participant had only partial resolution of their symptoms. Oral prednisone was the initial treatment for 17 of the 21 participants in category 1 (81%). Seven participants improved with corticosteroids alone (oral plus minus corticosteroid injections). All other participants required additional interventions to address their nerve injuries. Surgery was required to resolve nerve injuries in 9 of the 21 participants (43%). Surgery was the initial treatment for just 2 participants; the others had an initial course of oral prednisone first ().

CRPS after Chronic Median Entrapment Neuropathy

Category 2 consisted of 16 patients who presented with chronic signs and symptoms of median entrapment neuropathies at the wrist. The median duration of CRPS symptoms before being assessed in the clinic was 92 days (σ = 95.93; = 114.44; min = 39; max = 437). Of the 16 participants, 6 in category 2 had a fracture as the CRPS inciting event (38%) but the CRPS emerged slowly after. Other mechanisms included elective surgery, laceration, carpal tunnel syndrome, and stroke. Two participants had no clear cause for their CRPS. Nerve injuries were reported by the referring physician in 9 of 16 charts (56%).

All participants in this category had at least a functional recovery. Oral prednisone was the initial treatment for all except one patient in this category; this participant had steroid injections instead. Ten participants improved with just steroids (oral or injected), and 4 participants required carpal tunnel decompression surgery to address the nerve injury ().

Table 3. Patients whose nerve injury predated the onset of CRPS’s presentations, treatments, and outcomes sorted by initial treatment, additional treatments, and outcome.

Nerve Injury Emerged after CRPS Onset

The final category of four participants had late onset of nerve symptoms, long after their CRPS symptoms emerged; thus, the nerve injury was not felt to be a cause of the CRPS. All four had injuries affecting the upper limb. The median duration of CRPS symptoms before being assessed in the clinic was 71.50 days (σ = 20.80; = 78; min = 61; max = 108). CRPS was caused by fracture in two cases, a dislocation in one case, and one case had no clear cause. No nerve injuries were suspected by any referring physicians; electrodiagnosis revealed median or ulnar neuropathies in all participants in this category.

All participants in this category had at least a functional recovery after all treatments. All participants in this category had oral prednisone as the initial treatment. All but one participant in this category responded to oral prednisone alone. The final participant required surgery to address their nerve injury .

Table 4. Patients whose CRPS onset predated nerve injury’s presentations, treatments, and outcomes sorted by initial treatment, additional treatments, and outcome.

Discussion

This retrospective review analyzed the 41 patients who were diagnosed with discrete nerve injuries using electrodiagnosis (17%), out of 248 patients with CRPS. However, only 51% of the 41 referrals referenced a suspected nerve injury. Nearly all patients had a course of oral prednisone or corticosteroid injection; however, more than 30% of all patients required surgical interventions to resolve their discrete nerve injuries. Following our algorithm of oral prednisone, cortisone injections, and surgery, 24% participants had complete resolution of CRPS symptoms, and an additional 71% had a near-complete resolution of CRPS symptoms. Overall, 95% of the cohort reported at least a functional recovery from CRPS. It is important to note that in patients whose inciting injury was traumatic, residual effects from this traumatic injury or joint contractures are factors that could have prevented a full recovery.

Our patient population is in alignment with the expected epidemiology of CRPS.Citation1–3 A Mayo Clinic study found that fracture is the leading cause of CRPS, accounting for 46% of all cases.Citation11 CRPS affects females more than males, and upper extremities are more commonly affected.Citation3,Citation11,Citation12 In our cohort, 46% of patients had a fracture preceding CRPS, 59% were women, and 88% had upper extremity involvement.

A discussion of the evidence for using corticosteroids is not the objective of this article, because oral prednisone has been noted to be effective in managing acute CRPS symptoms.Citation8,Citation13–15 Because most patients in our cohort were seen within 6 months of onset of CRPS, lumbar and cervical sympathetic blocks were not utilized because blocking the sympathetic nervous system is no longer considered a first-line therapy.Citation5,Citation14,Citation15 In our cohort of patients with discrete nerve injuries, many patients did not respond fully to corticosteroids alone. Surgery for discrete nerve injuries was required for 34% of the 41 participants.

Without a neurological assessment, a nerve injury may not be identified. The inflammation of CRPS may hide the tell-tale signs of the injury and be revealed only after the treatment of swollen inflammatory features. For example, first dorsal interossei (FDI) wasting, indicative of ulnar neuropathy, is camouflaged by edema in . The lack of recognition of the presence of CRPS type II could negate the opportunity for a nerve-specific treatment, such as a surgical decompression at Guyon’s canal for this example. In some patients whose nerve injury predated CRPS onset, surgery may have been an additional inciting trauma; CRPS II has been linked to carpal tunnel release surgeries.Citation16–18 In this group, treatment with oral prednisone led to positive outcomes, likely due to its documented benefits for neuritis and similar compression conditions.Citation19,Citation20 However, four of these patients still required a surgical release for functional recovery (25%). In patients whose nerve injury emerged after the onset of CRPS, we hypothesize that entrapment neuropathy may have been a mechanical sequela of the swelling induced by CRPS I and not the cause of the CRPS. One participant in this group required a surgical intervention (25%). Surgical intervention or corticosteroid injections should be considered in the treatment of CRPS II, especially when an optimal outcome is not achieved from an initial course of oral prednisone.

Electrodiagnostic testing in patients with CRPS revealed that the distinction between CRPS I and II is not straightforward. The 14 patients who required surgical decompression demonstrate the precise relationship between ongoing CRPS symptoms and discrete nerve injury: both must be resolved for symptoms to abate. It is notable that the anti-inflammatory principles of prednisone can influence nerve injury caused by compression, as evidenced by the use of corticosteroids in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome.Citation21,Citation22 For disease processes such as neuritis, corticosteroids are considered to be first-line treatment in the acute phase.Citation19,Citation20

There are limitations to this study. All patients were treated by the same physical medicine and rehabilitation specialist, and almost all of the nerve studies were performed by them. Not all patients can tolerate electrodiagnosis, particularly prior to treatments, and swelling may make studies technically difficult. This study followed a cohort of only 41 participants, and data were compiled retrospectively, though the sample size included in this study is comparable to that of many other published CRPS studies, which remains a poorly understood and underinvestigated condition.

Conclusions

CRPS remains a challenging diagnosis due to the condition’s progressive nature. Electrodiagnosis could improve diagnosis and treatment outcomes for patients with CRPS. In this study, 60 of 248 patients diagnosed with CRPS underwent electrodiagnostic findings, 41 of whom had positive findings. Only 51% of the nerve injuries were identified by referring physicians. The presentation of CRPS can hide the tell-tale signs of nerve injury, and nerve-specific interventions like surgical decompression or targeted cortisone injections may be required for complete resolution. Therefore, electrodiagnosis should be considered for patients with CRPS in the acute or subacute phase who do not respond to initial treatment with corticosteroids and or rehabilitation.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Dijkstra PU, Groothoff JW, Duis HJ, Geertzen JHB. Incidence of complex regional pain syndrome type I after fractures of the distal radius. Eur J Pain. 2003;7(5):457–9. doi:10.1016/S1090-3801(03)00015-6.

- Jellad A, Salah S, Ben Salah Frih Z. Complex regional pain syndrome type I: incidence and risk factors in patients with fracture of the distal radius. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(3):487–92. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2013.09.012.

- Goh EL, Chidambaram S, Ma D. Complex regional pain syndrome: a recent update. Burns Trauma. 2017;5:5. doi:10.1186/s41038-016-0066-4.

- Goebel A, Birklein F, Brunner F, et al. The Valencia consensus-based adaptation of the IASP complex regional pain syndrome diagnostic criteria. Pain. 2021;162:2346–48. Publish Ah. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002245.

- Harden RN, Bruehl S, Stanton-Hicks M, Wilson PR. Proposed new diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain Med. 2007;8(4):326–31. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00169.x.

- Harden RN, Oaklander AL, Burton AW, Perez RSGM, Richardson K, Swan M, Barthel J, Costa B, Graciosa JR, Bruehl S, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: practical diagnostic and treatment guidelines, 4th edition. Pain Med (United States). 2013;14(2):180–229. doi:10.1111/pme.12033.

- van den Berg C, de Bree Pn, Huygen FJPM, Tiemensma J. Glucocorticoid treatment in patients with complex regional pain syndrome: a systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2022;26(10):2009–35. doi:10.1002/ejp.2025.

- Kwak SG, Choo YJ, Chang MC. Effectiveness of prednisolone in complex regional pain syndrome treatment: a systematic narrative review. Pain Pract. 22:381–90. Published online November 25, 2021. doi:10.1111/papr.13090.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies*. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(11):867–72. doi:10.2471/BLT.07.045120.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

- Sandroni P, Benrud-Larson LM, McClelland RL, Low PA. Complex regional pain syndrome type I: incidence and prevalence in Olmsted county, a population-based study. Pain. 2003;103(1):199–207. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00065-4.

- de Mos M, de Bruijn Agj, Huygen FJPM, Dieleman JP, Stricker CHBH, Sturkenboom MCJM. The incidence of complex regional pain syndrome: a population-based study. Pain. 2007;129(1):12–20. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.008.

- Jamroz A, Berger M, Winston P. Prednisone for acute complex regional pain syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. Pain Res Manag. 2020;2020:1–10. doi:10.1155/2020/8182569.

- Birklein F, Dimova V. Complex regional pain syndrome–up-to-date. Pain Rep. 2017;2(6):e624. doi:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000624.

- Birklein F, O’Neill D, Schlereth T. Complex regional pain syndrome: an optimistic perspective. Neurology. 2015;84(1):89–96. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001095.

- Chang C, McDonnell P, Gershwin ME. Complex regional pain syndrome – false hopes and miscommunications. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18(3):270–78. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2018.10.003.

- Koh SM, Moate F, Grinsell D. Co-existing carpal tunnel syndrome in complex regional pain syndrome after hand trauma. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2010;35(3):228–31. doi:10.1177/1753193409354015.

- Buller M, Schulz S, Kasdan M, Wilhelmi BJ. The Incidence of complex regional pain syndrome in simultaneous surgical treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome and dupuytren contracture. HAND. 2018;13(4):391–94. doi:10.1177/1558944717718345.

- da Costa VV, de Oliveira SB, Fernandes M, do CB, Saraiva RÂ. Incidência de síndrome dolorosa regional após cirurgia para descompressão do túnel do carpo: existe correlação com a técnica anestésica realizada? Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2011;61(4):429–33. doi:10.1590/S0034-70942011000400004.

- van Eijk Jjj, van Alfen N, Berrevoets M, van der Wilt Gj, Pillen S, van Engelen Bgm, van Eijk JJJ, van der Wilt GJ, van Engelen BGM. Evaluation of prednisolone treatment in the acute phase of neuralgic amyotrophy: an observational study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(10):1120–24. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2008.163386.

- van Alfen N, van Engelen Bg, Hughes RA. Treatment for idiopathic and hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy (brachial neuritis). Cochrane Database Syst. Published online July 8, 2009. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006976.pub2.

- Schäfer L, Maffulli N, Baroncini A, Eschweiler J, Hildebrand F, Migliorini F. Local corticosteroid injections versus surgical carpal tunnel release for carpal tunnel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Life. 2022;12(4):533. doi:10.3390/life12040533.