ABSTRACT

Background

Pulsed radiofrequency neuromodulation (PRFN) of greater occipital nerve (GON) is considered in patients with headaches failing to achieve sustained analgesic benefit from nerve blocks with local anesthetic and steroids. However, the evidence supporting this practice is unclear.

Aims

This narrative systematic review aims to explore the effectiveness and safety of GON PRFN on headaches.

Methods

Databases were searched for studies, published up to February 1, 2024, investigating PRFN of GON for adults with headaches. Abstracts and posters were excluded. Primary outcome was change in headache intensity. Secondary outcomes included effect on monthly headache frequency (MHF), mental and physical health, mood, sleep, analgesic consumption, and side-effects. Two reviewers screened and extracted data.

Results

Twenty-two papers (2 randomized controlled trials (RCT), 11 cohort, and 9 case reports/series) including 608 patients were identified. Considerable heterogeneity in terms of study design, headache diagnosis, PRF target and settings, and image-guidance was noted. PRFN settings varied (38–42°C, 40–60 V, and 150–400 Ohms). Studies demonstrated PRFN to provide significant analgesia and reduction of MHF in chronic migraine (CM) from 3 to 6 months; and significant pain relief for ON from six to ten months. Mild adverse effects were reported in 3.1% of cohort. A minority of studies reported on secondary outcomes. The quality of the evidence was low.

Conclusions

Low-quality evidence indicates an analgesic benefit from PRFN of GON for ON and CM, but its role for other headache types needs more investigation. Optimal PRFN target and settings remain unclear. High-quality RCTs are required to further explore the role of this intervention. PROSPERO ID CRD42022363234.

RÉSUMÉ

Contexte: La neuromodulation par radiofréquence pulsée (NRFP) du nerf grand occipital (NGO) est envisagée chez les patients souffrant de céphalées qui ne parviennent pas à obtenir un bénéfice analgésique durable à partir des blocages nerveux à l’aide d’un anesthésique local et de stéroïdes. Cependant, les données probantes à l'appui de cette pratique ne sont pas claires.

Objectifs: Cette revue systématique narrative vise à explorer l'efficacité et la sécurité de la NRFP du NGO sur les maux de téte.

Méthodes: Des bases de données ont été consultées pour trouver des études, publiées jusqu'au 1er février 2024, portant sur la NRFP du NGO chez des adultes souffrant de céphalées. Les résumés et les affiches ont été exclus. Le critére principal était le changement dans l'intensité des maux de téte. Les critéres secondaires comprenaient l'effet sur la fréquence mensuelle des céphalées, la santé mentale et physique, l'humeur, le sommeil, la consommation d'analgésiques et les effets secondaires. Deux examinateurs ont évalué et extrait les données.

Résultats: Vingt-deux articles (2 essais contrôlés randomisés, 11 cohortes et 9 rapports de cas/séries) portant sur 608 patients ont été recensés. Une hétérogénéité considérable a été observée en termes de devis de l'étude, de diagnostic des céphalées, de la cible et des paramétres de la FRP et de l'orientation de l'image. Les réglages de la NRFP variaient (38-42°C, 40-60 V, et 150-400 Ohms). Les études ont démontré que la NRFP procurait une analgésie significative et réduisait la fréquence des céphalées dans la migraine chronique de trois à six mois, et un soulagement significatif de la douleur pour la névralgie occipitale pendant six à dix mois. Des effets indésirables légers ont été signalés dans 3,1 % des participants de la cohorte. Une minorité déétudes ont fait état de résultats secondaires. La qualité des données probantes était faible.

Conclusions: Les données probantes de faible qualité indiquent un bénéfice analgésique de la NRFP du NGO pour la névralgie occipitale et la migraine chronique, mais son rôle pour d'autres types de céphalées doit être davantage étudié. La cible et les paramétres optimaux de la NRFP restent floues. Des essais contrôlés randomisés de haute qualité sont nécessaires pour explorer davantage le rôle de cette intervention.

Introduction

Headache disorders are a common affliction worldwide affecting approximately 15% of the world’s population.Citation1 There is a wide spectrum of headache disorders that are largely classified as either primary or secondary according to the International Classification of Headache Disorder–3rd Edition (ICHD-3).Citation2 Primary headache disorders include migraine, tension-type, and trigeminal autonomic cephalagias (TACs) that can all differ widely in their respective headache burden, pathophysiology, and management.Citation3,Citation4 Occipital neuralgia (ON), another notable headache diagnosis, is classified as a cranial neuropathy under part three of ICHD-3. Although, the medical management of these headache disorders has evolved and progressed substantially, it is estimated that more than 5% of patients remains refractory to treatments.Citation5

The trigeminocervical complex (TCC) has been proposed to play a major role in the central sensitization and pathogenesis of headaches.Citation6 The TCC is located within the brainstem and is the primary site where nociceptive, small-diameter cervical, dural, muscle and trigeminal afferents converge.Citation6 The greater occipital nerve (GON) carries with it the cervical, supratentorial dura (visceral) and muscle afferents that play a crucial role in the central sensitization and hyperexcitability of the entire converging neuronal network that forms the TCC.Citation6 As a result, in cases of refractory headache or craniofacial pain, prevailing theories support the notion that blocking or modulation the sensory inputs from the GON to the TCC may be helpful. The GON arises from the dorsal ramus of the C2 spinal nerve (dorsal root ganglion, ‘DRG’) and travels cranially in the suboccipital area through the semispinalis capitis muscle (SSCM) and the obliquus capitis inferior muscle (OCIM) before it arrives at the occiput and continues its course cranially over the skull along the occipital artery up to the vertex of the skull.Citation7

Landmark-guided (LMG) or ultrasound-guided (USG) GON blocks (GONB) with local anesthetics (LA) and/or steroids or botulinum toxin have proven their efficacy in reducing headache intensity and headache frequency for limited time.Citation8–10 Three targets for injecting or blocking the GON have been proposed: 1) close to the origin of the nerve at the level of C2 DRG (“DRG approach”); 2) along the proximal part of the GON while it is running suboccipital in the plane between the SSCM and OCIM (the “proximal approach”); or along the distal part of the GON at the level of the superior nucheal line (the “distal approach” approach). Image-guidance is required to perform the DRG-approach or proximal approach, but the distal approach is frequently performed under LMG. In terms of efficacy between targets, the literature on GON injections suggests similar results when comparing between the described distal and proximal approaches.Citation11–13 Adverse effects have been reported as minimal across studies regardless of approach.Citation11–14

Although beneficial, the literature on GONB with injectates as LA and steroid only suggests short-term efficacy from GONB lasting weeks to few months in the treatment of different headache disorders.Citation12,Citation14,Citation15 With hopes of extending the therapeutic benefit observed, a newer technique called pulsed radiofrequency neuromodulation (PRFN) has been proposed and investigated. This technique involves treating the nerves with radiofrequency waves generated by electric currents to prevent conduction of nociceptive signals. The mechanism of action is not yet fully understood but is thought to involve an alteration of the synaptic transmission, which creates a neuromodulatory-type effect.Citation16 Previous studies have identified PRFN as causing extended c-Fos activation in rats, potentially due to selective long-term depression in C-fiber–mediated spinal sensitization.Citation17 Other mechanisms proposed are possible microscopic thermal damage to thinly myelinated A-delta and unmyelinated C-fibers and reduction of proinflammatory cytokines.Citation18,Citation19 PRFN of a wide arrange of nerves and ganglions in the body, has proven to provide relief for several months to over a year, in the treatment of complex chronic pain states including axial pain, trigeminal neuralgia and facial pain, inguinal neuralgia, and other neuropathic pain states.Citation20–27

The therapeutic role of PRFN of the GON in the treatment of headache disorders has not been completely elucidated. Therefore, the objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the effectiveness and overall safety of PRFN of the GON in the treatment of headache disorders.

Methods

Registration

This systematic review (SR) was conducted according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration and was reported as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. The protocol of this SR was registered with PROSPERO (ID CRD 42022363234).

Data Sources and Search Strategy

We conducted a comprehensive search of the literature with the assistance of a medical information specialist from inception to November 1, 2022. An updated search was conducted over the same databases on February 1 2024.The following databases were searched: Embase Classic/Embase, 1947 onward; MEDLINE, 1946 onward; MEDLINE ePubs, In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations; Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2005 onward; and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, 1991 onward, (all using the Ovid Platform); and PubMed-NOT-MEDLINE (NLM NIH). We also searched Web of Science Core Collection, 1900 onward (Clarivate Analytics) and Scopus, 1960 onward (Elsevier). Clinical trial registries, ClinicalTrials.Gov (NIH) and WHO ICTRP (International Clinical Trials Registry Platform), were searched to identify trials. We restricted our search to human subjects. No language restrictions were implemented. For Embase, MEDLINE, Cochrane CENTRAL, and Scopus, both controlled vocabulary terms (Embase-Emtree; MEDLINE-MeSH) and text word searching were conducted. Both our initial and most recent Ovid MEDLINE detailed search strategies are provided in Appendices 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The studies were screened for eligibility based on title, abstract, and full text for the following criteria:

Population

This review included studies on human subjects of ≥ 18 years of age diagnosed with a headache disorder and/or ON according to the International Classification of Headache Disorder-3rd Edition (ICHD-3).Citation2 No restrictions were put in terms of duration and frequency of headache. Studies that investigated effects of PRFN on a mixed population of pain patients for which relevant data could not be extracted separately were excluded.

Intervention

The intervention was defined as PRFN of the GON. Any approach (distal or proximal approach on the GON or C2 DRG) was accepted. There was no limit on the duration of the treatment or number of treatments.

Comparator

Comparators included no treatment, placebo treatment or conventional medical management, which could include pharmacological, physical, psychological, and/or interventional therapies.

Outcome

The primary outcome of interest was the effect on pain (headache) intensity, as measured by the numeric rating scale (NRS) or visual analogue scale (VAS). Secondary outcomes of interest included: 1) headache frequency, 2) mental and physical outcome, 3) mood, 4) sleep, 5) analgesic consumption, 6) quality of life, 7) patient satisfaction.

Study Designs

The scope of studies included randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, observational or cohort studies, case-control studies, and case series/reports.

Study Selection Process

All citations were independently screened on title and abstract for eligibility by two reviewers (K.D. and N.D.) as per the inclusion criteria. Covidence® was used as a systematic review management tool. Papers of interest were then full text screened. Of the selected papers, data was independently extracted by two reviewers (K. D. and N.D.). Any apparent conflicts were resolved through discussion with senior author (Y.H.).

Data Extraction

The reference data, populations, and outcomes were extracted from the articles into pre-specified tables on a standardized data collection form in Microsoft Word that was pilot tested before use. Extracted data for each study included: general characteristics (first author, publication year, number of patients, and study design), patient characteristics (age, gender), clinical information (diagnosis, duration, baseline headache intensity and headache frequency), details of intervention (approach – C2 DRG/distal/proximal, PRFN settings, type of image guidance, duration of therapy) and comparator (dose, duration, regimen), data on primary and secondary outcomes of interest, follow-up time points, and adverse effects. For continuous data, means (or medians) and standard deviations (or interquartile ranges or ranges) were extracted.

Assessment of Quality as Risk of Bias

Two review authors (K.D. and N.D.) independently assessed the risk of bias for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool 2.0.Citation28 Any disagreement was resolved through discussion with senior author (Y.H.). The Robins-I was used to assess the risk of bias in observational studies.Citation29 For case reports/case series, the Quality Appraisal Tool for Case Series was used.Citation30

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We narratively synthesized the characteristics of all studies that met inclusion criteria. Study characteristics and study outcomes were summarized. No meta-analysis was performed due to the heterogeneity of data and small sample sizes reported.

Results

Search Results

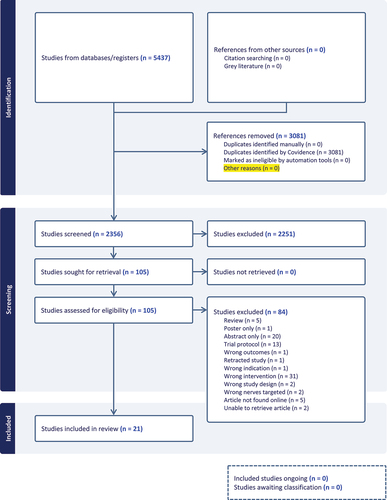

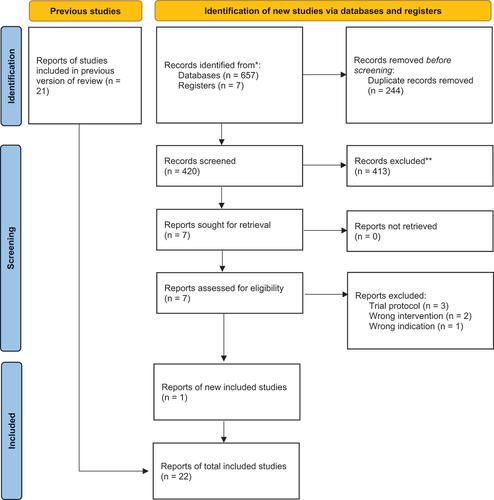

The initial search strategy retrieved a total of 2356 studies, of which 2251 studies were excluded at the screening stage. Full texts of 105 articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 21 studies deemed to meet all eligibility criteria for inclusion in this review. Our updated search retrieved an additional 664 studies, of which 657 studies were excluded at the screening stage. Full texts of 7 articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 1 study was deemed to meet all eligibility criteria for inclusion in this review. Finally, two RCTs,Citation31,Citation32 four prospective cohort studies,Citation33–36 seven retrospective cohort studies,Citation37–43 two case series,Citation44,Citation45 and 7 case reports were included.Citation46–52 A summary of the original search strategy is described in (PRISMA Original Search) and the updated search in (PRISMA Updated Search).

Figure 2. PRISMA Flow Diagram for Updated Systematic Review.

Risk of Bias for Included Studies

The results for assessment of the risk of bias for the included RCTs are summarized in . The overall risk of bias was deemed to be of “some concerns” for both included RCTs.Citation31,Citation32 The risk of bias assessment of the included cohort studies revealed five studies were deemed to be at moderate risk of bias,Citation34–38,Citation40-43 three studies were found to be at serious risk,Citation39-41,Citation42 and one critical ().Citation33 The risk of bias of the case series was moderate ().Citation44,Citation45

Study Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of all PRFN treated patients reported in the 22 included studies are summarized in . The use of PRFN for the management of a primary headache disorder (migraine disorder, tension type, TAC) was reported in six cohort studiesCitation43–48 and three case reports/series.Citation49–51 The use of PRFN for the management of a secondary headache disorder (cervicogenic headache or headache caused by atlantoaxial instability) was reported in seven studies: one RCT,Citation32 four cohort studiesCitation35,Citation40–42 and two case reports.Citation49,Citation52 PRFN was used in the management of ON in a total of six studies: one RCT,Citation31 four cohort studiesCitation34,Citation36,Citation37,Citation39 and one case report.Citation51

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review: participants, interventions, comparators and outcome measures.

Patient Characteristics

A total of 608 patients were included in this review, age ranging from 22 to 82 years. Gender was not included for 77 of the 608 patients.Citation34,Citation35 Of the remaining 531 patients, 52% were female. Two hundred and twenty-three (36.7%) subjects had a diagnosis of ON, 222 (36.5%) were afflicted with cervicogenic headaches (CEH), 118 (19.4%) suffered with chronic migraine (CM), and 15 (2.5%) experienced cluster headaches (CH). One patient each (0.16%) remained for short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT), tension type headache disorder (TTH), headache caused by atlantoaxial instability. Baseline headache intensity was moderate to severe, ranging from 4/10 to 9/10 on a Numerical Rating Scale (NRS).

PRFN Targets

Three different interventional targets were found: PRFN was applied at the level of C2 DRG in eight studies,Citation35,Citation40–42,Citation46,Citation49,Citation50,Citation52 as a “distal GON approach” in 11 studies,Citation31–34,Citation36,Citation37,Citation39,Citation43,Citation44,Citation47,Citation51 in a “proximal GON approach” in three studies.Citation38,Citation45,Citation48

PRFN Settings

Treatment parameters for PRFN consisted of one,Citation31–38,Citation40–43,Citation45,Citation46,Citation48–52 two,Citation39,Citation47 or threeCitation44 cycles on a temperature of 42°C for a duration of 9040 or 120Citation39,Citation42,Citation47,Citation49,Citation51 to 360Citation34,Citation38,Citation43,Citation45,Citation48 seconds at 40–60 volts.Citation31,Citation34,Citation36,Citation38,Citation39,Citation42,Citation43,Citation48,Citation50 Two outliers reported one cycle of 900 seconds.Citation35,Citation50 Pulse widths were indicated as either fiveCitation38,Citation43,Citation45,Citation48 or twenty milliseconds.Citation31,Citation35,Citation36,Citation39,Citation42,Citation44,Citation50,Citation51

PRFN Single Cycle

Nineteen out of 22 included studies utilized a single PRFN treatment cycle: all studies on use of PRFN at C2 DRG levelCitation35,Citation40–42,Citation46,Citation49,Citation50,Citation52 and at “proximal GON approach,”Citation38,Citation45,Citation48 and 8 out of 11 studies exploring PRFN at the “distal GON approach.”Citation31–34,Citation36,Citation37,Citation43,Citation51

Image Guidance

Five papers performed PRFN utilizing USG,Citation38,Citation45,Citation46,Citation48,Citation51 seven studies reported LMG technique,Citation31–34,Citation36,Citation39,Citation43 three studies used X-ray guidance (XRG),Citation37,Citation40,Citation52 one study used CT-guidance (CTG)Citation35 and one study combined CTG and USG.Citation50 The remaining five studies did not comment on use of image guidance.Citation41,Citation42,Citation44,Citation47,Citation49

Duration of Follow-up

Follow-up times ranged from one week,Citation35,Citation44 two weeks,Citation31,Citation46,Citation48 one month,Citation33,Citation34,Citation36,Citation38,Citation40,Citation45 two months,Citation42 three months,Citation32,Citation39 six months,Citation37 one yearCitation50, to two years after treatment.Citation41 In four studies, follow-up timepoints were not specified.Citation47,Citation49,Citation51,Citation52

Duration of Analgesic Benefit

Duration of analgesic benefit from PRFN was reported in a total of 21 studiesCitation31–50,Citation52 and ranged from 3 months,Citation34,Citation38,Citation39,Citation48 4 months,Citation45 6 monthsCitation31,Citation35,Citation39,Citation40,Citation43,Citation44,Citation49,Citation50,Citation52, 8 monthsCitation36,Citation41,Citation46, 9 monthsCitation32, 12 monthsCitation33,Citation42,Citation47, 15 monthsCitation39, 18 months to 2 years.Citation37,39

Secondary Health Outcomes

A total of eight studies reported on MHF.Citation31,Citation34,Citation38,Citation43–45,Citation47,Citation48 Eight studies reported on analgesic consumption.Citation32,Citation34,Citation36,Citation37,Citation42,Citation43,Citation45,Citation47 Four studies reported on QOL measures.Citation31,Citation36,Citation38,Citation41 Two studies reported on the impact of PRFN treatment on quality of sleep.Citation38,Citation41

PRF Effects on Headache Disorders Stratified by PRF Targets

C2 Drg

We found eight studies (four cohort studies,Citation35,Citation40–42 four case reportsCitation46,Citation49,Citation50,Citation52) examining the effects of PRFN treatment to the DRG of C2 for CEH,Citation35,Citation40–42,Citation52 CH,Citation46 CM,Citation50 and headache caused by atlantoaxial instability.Citation49 Two studies used an XRG technique,Citation40,Citation52 one study used CTG,Citation35 one study used USG,Citation46 and one case report used a combined approach with CTG and USG.Citation50 Three studies did not specify any use of image guidance technique.Citation41,Citation42,Citation49

Summary of Results with C2 DRG Approach

A total of 213 patients across eight studies were analyzed that utilized the C2 DRG approach to PRFN in the treatment of headaches.Citation35,Citation40–42,Citation46,Citation49,Citation50,Citation52 For CEH, two studiesCitation35,Citation41 and one case reportCitation52 (n = 161) out of five studies were deemed to demonstrate significant pain relief up to 6 monthsCitation35,Citation52 or a median duration of effect of 8 months.Citation41 We found one case report each for the indication of chronic CH, CM, and AAS, with patients having significant pain relief from 6 months up to 24 months.

CEH

Five studies (four cohort studies,Citation35,Citation40–42 one case reportCitation52) investigated the effect of PRFN on C2 DRG for patients suffering from CEH. ()

Table 2. Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review: follow-up times, results and adverse effects.

Table 3. Cochrane risk of bias tool for RCTs 2.0

Table 4. The Risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions (ROBINS-I) assessment tool

Table 5. Quality appraisal checklist for case series studies.

One study compared cervical epidural steroid injections (CESI) (n = 52) to CESI combined with PRFN (n = 87).Citation41 Significant long-term reduction in headache intensity was demonstrated in both groups, with the group combining CESI with PRFN (42°C, 60 Hz, 300s) to be found superior. Notably, in this study, 8 patients who failed to obtain relief from CESI were successfully treated with PRFN afterward. Five refractory patients from the PRFN + CESI group underwent a second PRFN treatment, with three patients experiencing subsequent relief. Median duration of pain relief was 8 months (CESI+PRFN cohort) versus 4 months (CESI group). In terms of secondary outcome measures, overall quality of life with respect to cognitive function (p = 0.026), emotional functioning (p < 0.001) and physical function (p < 0.001) was improved in the PRFN group versus comparator. Sleep quality was also significantly better in the PRFN group (p < 0.001).

Another retrospective cohort study assessed the analgesic effect of three PRFN cycles (42°C, 90s).Citation40 At 6 months post-intervention, 51% of patients demonstrated to have a 30% or more pain reduction from baseline.

In a third study, only 2 out of 4 patients receiving PRFN (42°C, 45 V, 20 ms PW, 120s) experienced successful pain reduction, lasting 18 and 24 months, respectively.Citation42 One patient experienced no pain reduction and one patient experience a worsening of pain at the 8-week follow-up timepoint. Analgesic intake was reported to be reduced in all four patients.

Another prospective cohort study involved 20 patients, of which two presented with CEH.Citation35 They were treated with a single cycle of USG PRFN (42°C, 65 V, 2 Hz, 20 ms PW, 900sec). Overall, there were significant decreases in both headache intensity and BPI scores at 6 months post-intervention (mean headache intensity from 7.1 to 1.75, p < 0.05).

We found one case report of two patients who were treated with XRG PRFN (42°C, 240 sec).Citation52 Baseline NRS pain intensities were moderate (4/10 and 5/10). Following treatment, both patients had complete resolution of pain lasting 6 months.

CM

In one case report, a female with CM was completely headache free up to one year, after a combined USG and CTG single-cycle PRF (42°C, 45 V, 2 Hz, 20 ms PW, 900 sec). The patient was able to return to work full-time with headache intensity (VAS) reduced from a baseline of 8/10 to 0/10 at 1-year post-treatment.Citation50

CH

In one case report, a male with chronic CH was treated with one session of PRFN (42°C, 90s) and reported complete pain relief of retrobulbar pain up to 8 months post-treatment. The patient was able to discontinue all analgesics.Citation46

Other

We found one case report investigating PRFN at C2 level for headache and neck pain due to atlanto-axial subluxation (AAS).Citation49 Baseline pain scores were high and refractory. After three cycles of PRFN (42°C, 120 sec), her neck pain intensity significantly decreased and occipital pain completely resolved at 6 months.

Distal GON Approach

We found 11 studies (two RCTs,Citation31,Citation32 six cohort studies,Citation33,Citation34,Citation36,Citation37,Citation39,Citation43 one case series,Citation44 two case reportsCitation47,Citation51) assessing the effect of PRFN treatment targeting the distal GON. Eight studies used LMG technique,Citation31–34,Citation36,Citation39,Citation43 one study used XRG,Citation37 and one case report USG.Citation51 The remaining two studies did not specify any use of image guidance technique.Citation44,Citation47

Summary of Results with Distal Approach

A total of 362 patients were analyzed in the 11 studies that utilized the distal approach to PRFN of the GON.Citation31–34,Citation36,Citation37,Citation39,Citation43,Citation44,Citation47,Citation51

For CEH, significant reductions in headache intensity and analgesic consumption were observed at 3 and 9 months in one pilot trial.Citation32 However, these findings in CEH should be noted with caution due to the study’s design as a pilot trial with a smaller sample size. For CM, two studiesCitation34,Citation43 (n = 65) reliably demonstrated significant relief in terms of pain relief up to 6 monthsCitation34,Citation43 and reduction in MHDCitation34,Citation43 up to 6 months, and reduction in analgesic intake.Citation43 For CH, the current evidence is inconclusive. For ON, one RCTCitation31 comparing PRFN to LA/steroid with sham PRFN and four out of five observational studiesCitation34,Citation36,Citation37,Citation39,Citation51 (n = 82) demonstrated significant pain relief from 6,Citation34,Citation36,Citation51 to 10 months. We found one case report for the indication of SUNCT, with significant decrease in terms of headache frequency and headache intensity, up to 12 months.Citation47

CEH

We found one pilot RCT applying PRFN to the distal part of GON for CEH disorder.Citation32 Patients were randomly allocated to single LMG PRFN treatment (42°C, 45 V, two cycles of 120 seconds) or GONB with LA and steroids. Authors concluded that both groups achieved significant reduction in headache intensity and analgesic consumption at 3 and 9 months, however these results need to be assessed under scrutiny due to the type of study (pilot trial).

CM

Two prospective cohort studiesCitation33,Citation34 and one retrospective cohort studyCitation43 employed the distal GON approach for PRFN in the management of CM. In the first prospective study, 30 patients received a LMG single PRFN treatment (42°C, 42 V, 180 seconds, 3 cycles).Citation33 NRS of 3/10 or less was achieved in 27 patients (90%) at 1 month, and in 28 patients (93%) at 6 and 12 months. However, the study was deemed to have a critical risk of bias due to confounding, missing data and lack of adequate outcome reporting.

In the second study, 57 patients received one LMG GON PRFN treatment (42°C, 40–60 V, 360 sec).Citation34 Thirty-eight patients within the cohort had a diagnosis of CM with an average baseline NRS of 8.45 (SD 1.28) and median 14.5 [interquartile range; IQR 8–25] headache days per month. Monthly headache days (MHD) was significantly reduced from baseline (14.5 [8–25] MHD) at one month (2 [4–15] MH; p = 0.0001), at 3 months (6.5 [2–12]; p = 0.0001), and at 6 months (6.5 [3–12]; p = 0.0001). Headache intensity was also significantly reduced from baseline (8.5 [8–10]) to 1 month (7 [5–8]; p = 0.0005), at 3 months (6 [5–8]; p = 0.0001) and at 6 months (6 [5–8]; p = 0.0001). There was no significant change in analgesic consumption.

In one retrospective cohort study, 27 migraine patients received a single PRFN treatment one month after inadequate response to GONB (42°C, 45 V, 360 sec at 5 Hz, 5 mm PW).Citation43 All patients had significant improvement post-PRFN as compared to baseline, up to 6 months, in terms of MHF (post-PRFN 2.00 ± 1.00 vs baseline 12.04 ± 2.83; p < 0.001), headache episode duration in hours (post-PRFN 6.00 ± 6.00 vs baseline 49.33 ± 19.78; p < 0.001), and total analgesic consumption (post-PRFN 2.00 ± 1.00 vs baseline 11.00 ± 4.10; p < 0.001).

CH

One prospective cohort study reported a significant difference in headache intensity at 3 months (NRS 9 [IQR 8–9] vs 8 [IQR 0–8]; p = 0.0313) but not at 6 months.Citation34 The MHD was significantly reduced from baseline (15 [IQR 15–30]) to 1 month (2 [0–15]; p = 0.0156) and at 3 months (2 [0–15]; p = 0.0156) but not at 6 months. No significant difference in overall analgesic consumption was reported.

In a second study, two out of four patients reported complete relief of CH up to 6 and 15 months, respectively, after one PRFN treatment.Citation44 For the remaining patients, PRFN treatment was repeated with subsequent complete relief up to 15 months.

ON

A total of six studies including one RCT and five observational studies evaluated the effects of GON PRFN in patients with a diagnosis of ON.Citation31,Citation34,Citation36,Citation37,Citation39,Citation51

We found one RCT comparing PRFN (42°C, 40–60 V, 20 msec PW, 3 × 120 sec) to GONB with LA and steroid followed by sham PRFN.Citation31 The PRFN group demonstrated significant and superior pain reduction up to 6 months post-intervention as compared to baseline. (mean change from baseline for the PRFN group versus steroid group: –1.413 ± 2.352 vs –0.33 ± 1.382; p = 0.017). No significant differences were noted between groups in terms of headache frequency, depression, rescue analgesic consumption, or quality of life.

A small retrospective study on 10 patients investigated the effect of single XRG PRFN (42°C, 240 sec/cycle, duration unspecified).Citation37 Mean pain scores were significantly improved from baseline to last follow-up at 10 months post-intervention (6.9 vs 0.8; p < 0.001). Analgesic consumption was significantly decreased.

A large retrospective observational study of 102 patients assessed the effect of LMG GON PRFN (42°C, 40–60 V, 150–500 Ω, 120 seconds/cycle).Citation39 The study was deemed inconclusive, as only 52 patients (52%) experienced greater than or equal to 50% pain relief and procedural satisfaction with GON PRFN treatment lasting a minimum of three months.

Another prospective cohort study investigated the effect of a single LMG PRFN (42°C, 45 V, 240 sec/cycle).Citation36 VAS headache intensity significantly reduced from baseline (mean 7.5 ± 0.4) to 1 month (3.5 ± 0.8; p < 0.001), at 2 months (3.5 ± 0.7; p < 0.001), and at 6 months (3.9 ± 0.8; p = 0.002). Disturbance of daily activity, mood and sleep disturbance and analgesic consumption each significantly improved at 1 month, 2 months, and 6 months follow-up, as compared to baseline.

Lastly, VanderHoek et al. described a case report of a 32-year-old male patient who received a single treatment of USG GON PRFN (38–42°C; 2 × 120 sec).Citation51 The patient experienced 100% pain relief for several months.Citation51

SUNCT

Only one study assessed PRFN of the distal GON in a 75-year-old female with longstanding history of SUNCT.Citation47 She had previously been treated with three GONB with LA and steroid with a positive response lasting 3–4 months but this effect started to wane. She was then treated with two PRFN treatments (42°C; 2 × 120 sec), each treatment 8 months apart, each treatment giving her 80% reduction in headache frequency and headache intensity, up to 12 months.

Proximal GON Approach

We only found three studies (one retrospective cohort, one case series, one case report)Citation38,Citation45,Citation48 utilizing a proximal PRFN approach, all performed with USG in patients with CM (n = 33).

Summary of Results with Proximal Approach

A total of 33 patients – solely CM patients – across three studies were analyzed using the proximal approach to PRFN of the GON.Citation38,Citation45,Citation48 All studies reported a substantial reduction in headache intensity and frequency from 3 monthsCitation38,Citation48 to 6 months.Citation45

CM

In a first retrospective cohort study (n = 25), patients received a single PRFN cycle of 360-second duration.Citation38 Headache intensity, MHD and average headache duration were significantly improved up to 3 months’ post-intervention. Significant improvements in sleep quality (as measured with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)) and overall migraine disability on patient life (as measured with the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS)) were also observed at both the one and three month follow up timepoints.

A small case series (n = 6) looked at the effect of a single 360 second cycle of USG PRFN.Citation45 NRS headache intensity and headache frequency decreased significantly from baseline up to 6 months (p < 0.05), with two patients remaining completely free of pain at 6 months post-PRFN. Three out of six patients were reported to have halved their daily analgesic consumption, and they began to appreciate again a positive effect from their abortive therapy (triptans and/or NSAIDs).

One case report on two patients with severe CM reported favorable outcomes in terms of headache intensity in both patients up to 3 months, but no significant change in headache duration or frequency.Citation48

Adverse Effects and Complications of PRFN Treatment

Only five studies reported on the adverse effects of PRFN treatment.Citation31,Citation32,Citation35,Citation39,Citation44 Four out of five studies employed the distal approach.Citation31,Citation32,Citation39,Citation44 Overall, only 3.1% of all study patients included in this review reported mild and temporary adverse effects that included worsened headache (<10 days), cervicalgia, local discomfort, dizziness, rash and localized swelling, pain at injection site lasting >24 hours, pain exacerbation or new onset retro-auricular pain, which subsided within 3 weeks. No serious complications were reported on the 3 PRFN approaches across all studies.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review analyzing the therapeutic role of PRFN of the GON in the treatment of headache disorders. Our extensive literature search found 22 studies of which only two RCTs, with the overall quality of evidence rated of low quality. The present data indicates an analgesic benefit from PRFN treatment for ON and CM with occipital tenderness. Studies demonstrated PRFN to provide significant analgesia and reduction of MHF in CM from 3 to 6 months; and significant pain relief for ON from 6 to 10 months. Mild adverse effects were reported in 3.1% of cohort. The analgesic benefit of PRFN for other headache disorders remains unclear at this time. There is no clear superiority of certain PRFN settings, anatomical approach or image guidance identified demonstrated in this review.

PRFN Impact on Headache Pain and Pain-Associated Domains

Current evidence indicates there is some evidence for analgesic benefit from PRFN for GON for ON and migraine with occipital tenderness. However, the analgesic benefit of PRFN for other headache disorders is unclear due to low number and quality of included studies and needs to be further investigated.

Most of the studies did not consequently investigate nor report impact of PRFN on pain-associated domains. Only eight studies reported impact on analgesic consumption, seven studies demonstrated a significant decrease Citation32,Citation36,Citation37,Citation42,Citation43,Citation45,Citation47 Furthermore, six out of only eight studiesCitation34,Citation38,Citation43–45,Citation47 reporting on MHF showed a significant decrease, of note the only RCT investigating this secondary outcome reported no significant decrease between groups. There is a lack of use of validated questionnaires to measure these secondary outcomes across all studies.

Impact of Choice of Target

Although the first impression of the data might suggest that PRFN of GON may be effective for all headache types and across all targets, new insights are gained when closer reviewing the data. As for the ON patient population, we only found studies targeting the GON at the distal approach. Therefore, no statements can be made as to the efficacy of PRNF on the other targets for this population. As for CM, there is currently only one case report to support the use of PRFN at the C2 level. The majority of evidence focuses and supports the use of distal and proximal GON approach, but no statement can be made as to target superiority due to lack of comparative study. We did find a previous study comparing the efficacy of distal versus proximal GONB for CM that demonstrated no significant difference in efficacy.Citation12

As for the CEH population, the majority of studies investigate and support the choice of C2 target for PRFN. Interestingly, we only found one study (RCT) concluding both PRFN and GONB with LA and steroid delivered significant pain relief when applied at the distal GONB approach.Citation32 Although not superior, this study indicates that PRFN could be applied with long-term effect in CEH patients when steroids are contra-indicated. We did not find any studies investigating the use of proximal PRFN for CEH.

Impact of Image Guidance

When comparing image guidance techniques in the included studies, we did not notice a substantial difference in efficacy. Our review only discovered three studiesCitation39,Citation40,Citation42 that reported a negative outcome of PRF of GON for headaches, one study using LMG,Citation39 one study using XRG,Citation40 and one study did not specify approach.Citation42 This small number makes it impossible to draw any conclusion about the potential correlation between efficacy and image guidance techniques.

The Use of PRFN versus GONB with LA/steroid

GONB has been shown to be a cost-effective, minimally invasive, and safe intervention for headache management.Citation53 However, (chronic) steroid exposure is associated with a wide range of harmful effects.Citation54 PRFN has been shown to be an easy-to-use interventional treatment associated with minimal tissue trauma without the risks associated with steroid administration.Citation55 The application of PRFN for other pain indications has been demonstrated to provide long-lasting relief, similar or even longer than the duration of LA and steroid.Citation26,Citation56 Our evidence also suggests that PRFN is associated with longer duration of relief versus GONB with LA/steroid for the indication of headaches. Thus, PRFN presents as a potentially more effective and safe treatment alternative for the headache patients, especially for those chronic headache patients refractory to standard treatment who are likely to return for repeated procedures.

Relation to Other Studies

Few systematic reviews have been published exploring the effectiveness of both PRFN and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) in the treatment of headache disorders and facial pain.Citation57–59 Two systematic reviews explored the efficacy of both PRFN and RFA to the zygapophysial joints of the cervical spine in the treatment of cervicogenic headaches only.Citation58,Citation59 The third systematic review explored the available evidence on both PRFN and RFA for a range of different anatomical targets (C1C2 joint, GON, suprascapular nerve) for headaches.Citation59 This review however only included literature published up to 2019 and the authors only included three studies on the use of PRFN for GON. Further, when presenting the evidence of PRFN for GON for headaches, the authors did not stratify the data according to anatomical GON target.

Our systematic review is the only systematic review focused solely on PRFN of the GON in the treatment of all headache types. Our review is unique in its organization and reporting of studies based on the three anatomical approaches targeting the GON, while giving a comprehensive overview of the evidence for each different headache type.

Safety Profile

PRFN has been widely accepted as a safe and effective analgesic treatment for different chronic pain syndromes.Citation60 The incidence of side-effects and complications in the studies reported in this review was low and most side-effects were mild and resolved spontaneously. Our review did not indicate any overt differences in safety across different PRFN settings. However, we did note that of the five studies that reported adverse effects, four studies had used a LMG approach when targeting the distal GON,Citation31,Citation32,Citation39,Citation44 advocating for image-guidance when performing nerve blocks. This is in concordance with previous studies in interventional pain practice, indicating that use of image-guidance improves safety and accuracy.Citation61 USG has been advocated as the safest option compared to CTG or XRG, due to the lack of radiation.Citation61

Limitations

This review has several limitations. Despite the potential for benefit of PRFN in the treatment of headaches, only a few high quality prospective RCTs have evaluated this question. The majority of the included data comes from observational studies, with inherent risk of bias and confounding. The quality of the included studies was moderate to low. Further, the majority of those studies did not include a control group. The heterogeneity across studies was also significant, with large differences in terms of headache indication, intervention parameters (e.g., anatomical PRFN target, PRFN settings, duration of treatment) image guidance technique, and comparators that made interstudy comparison challenging.

Future Research

Future comparative studies should therefore focus on determining the best anatomical target, optimal intervention parameters, and image-guidance technique for PRFN treatment for each headache disorder. Although the observational studies suggest a beneficial effect of PRFN for CM, high-quality comparative trials are needed to fully assess and establish the efficacy of PRFN as a treatment for headaches. Future trials could also benefit from focusing on secondary health outcome measurements in different headache populations, such as adding MHF, QOL, sleep, and validated headache questionnaires, such as HIT-6Citation62 or MIDASCitation63 to explore the full effects of PRFN treatment.

Conclusions

Low-quality evidence indicates an analgesic benefit from PRFN for GON for ON and migraine with occipital tenderness but more evidence is needed to clearly confirm that it is substantially better than a blockade with LA and steroids. The role of PRFN for other headache disorders needs to be more investigated. Due to considerable heterogeneity across studies and lack of comparative studies, it remains difficult to formulate clear recommendations as to optimal PRFN target, settings, and location. High-quality RCTs with allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors and participants are required to further explore the role of this intervention.

Acronym List

AAS: Atlantoaxial subluxation; CEH: Cervicogenic headache; CESI: Cervical epidural steroid injection; CH: Cluster headache; CM: Chronic migraine; CTG: Computed tomography guidance; DRG: Dorsal root ganglion; GON: Greater occipital nerve; GONB: Greater occipital nerve block(s); HIT-6: Headache impact test; ICHD: International classification of headache disorders; LA: Local anesthetic(s); LMG: Landmark-guided; MHD: Monthly headache days; MHF: Monthly headache frequency; MIDAS: Migraine disability assessment; NRS: Numeric rating scale; OCIM: Obliquus capitis inferior muscle; PRISMA: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis; PRFN: Pulsed radiofrequency neuromodulation; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; RFA: Radiofrequency ablation; SR: Systematic review; SSCM: Semispinalis capitis muscle; SUNCT: Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing; TAC: Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia; TCC: Trigeminocervical complex; TTH: Tension type headache; USG: Ultrasound-guided; VAS: Visual analog scale; XRG: X-ray guided.

Authorship Statement

Conception and design: KD and YH; Drafting of the article: KD and YH; Research into, design of, and execution of database search strategies: ME; Management and curation of database results, write up of search methodology; ME; Data acquisition, analysis & interpretation: KD, ND, GA and YH; Review and editing of manuscript: KD, ND, ME, AG and YH.

Attestation

Kyle De Oliveira participated in the conception of the review, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript.

Nina D’hondt participated in the acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data and review of manuscript.

Marina Englesakis participated in the execution of database search strategies, management of database results, and review of the manuscript.

Akash Goel participated in the interpretation of data and review of the manuscript.

Yasmine Hoydonckx participated in the conception of the review, acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, and drafting the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Stovner L, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton RB, Scher AI, Steiner TJ, Zwart J-A. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(3):193–21. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018 Jan;381:1–211.10.1177/0333102417738202

- Hoffman J, May A. Diagnosis, pathophysiology, and management of cluster headache. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(1):75–83. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30405-2.

- Pan W, Peng J, Elmofty D. Occipital neuralgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2021;25(9):61. doi:10.1007/s11916-021-00972-1.

- D’Antona L, Matharu M. Identifying and managing refractory migraine: barriers and opportunities? J Headache Pain. 2019 Aug 23;20(1):89. doi:10.1186/s10194-019-1040-x.

- Bartsch T, Goadsby PJ. The trigeminocervical complex and migraine: current concepts and synthesis. Current Pain Headache Rep. 2003;7(5):371–376. doi:10.1007/s11916-003-0036-y.

- Li J, Szabova A. Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks in the head and neck for chronic pain management: the anatomy, sonoanatomy, and procedure. Pain Physician. 2021 Dec;24(8):533–548.

- Ryu JH, Shim JH, Yeom JH, Shin WJ, Cho SY, Jeon WJ. Ultrasound-guided greater occipital nerve block with botulinum toxin for patients with chronic headache in the occipital area: a randomized controlled trial. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2019;72(5):479–485. doi:10.4097/kja.19145.

- Chowdhury D, Datta D, Mandra A. Role of greater occipital nerve block in headache disorders: a narrative review. Neurol India. 2021 Mar-Apr;69(Supplement):S228–S256. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.315993.

- Inan LE, Inan N, Unal-Artik HA, Atac C, Babaoglu, Babaoglu G. Greater occipital nerve block in migraine prophylaxis: narrative review. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(7):908–920. doi:10.1177/0333102418821669.

- Elsayed A, Elsawy TTD, Rahman AEA, Arafa SKH. Bilateral greater occipital nerve block distal versus proximal approach for postdural puncture headache: a randomized controlled trial. Pain Physician. 2023;26:475–483.

- Flamer D, Alakkad H, Soneji N, Tumber P, Peng P, Kara J, Hoydonckx Y, Bhatia A. Comparison of two ultrasound-guided techniques for greater occipital nerve injections in chronic migraine: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2019;44(5):595–603. doi:10.1136/rapm-2018-100306.

- Yoo MC, Kim H-S, Lee JH, Yoo SD, Yun DH, Kim DH, Lee SA, Soh Y, Kim T, Han YR, et al. Ultrasound-guided greater occipital nerve block for primary headache: comparison of two techniques by anatomical injection site. Clin Pain. 2019;18:24–30.

- Kissoon NR, O’Brien TG, Bendel MA, Eldrige JS, Hagedorn JM, Mauck WD, Moeschler SM, Olatoye OO, Pittelkow TP, Watson JC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of landmark-guided Greater Occipital Nerve (GON) block at the superior nuchal line versus ultrasound-guided GON block at the level of C2. Clin J Pain. 2022;38(4):271–278. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000001023.

- Chowdhury D, Mundra A. Role of greater occipital nerve block for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: a critical review. Cephalalgia Rep. 2020;3:1–20. doi:10.1177/2515816320964401.

- Chua NH, Vissers KC, Sluijter ME. Pulsed radiofrequency treatment in interventional pain management: mechanisms and potential indications-a review. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2011 Apr;153(4):763–771. doi:10.1007/s00701-010-0881-5.

- Cahana A, Van Zundert J, Macrea L, van Kleef M, Sluijter M. Pulsed radiofrequency: current clinical and biological literature available. Pain Med. 2006;7(5):411–423. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00148.x.

- Hamann W, Abou-Sherif S, Thompson S, Hall S. Pulsed radiofrequency applied to dorsal root ganglia causes a selective increase in ATF3 in small neurons. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:171–176. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.03.001.

- Sluijter ME, van Kleef M. Pulsed radiofrequency. Pain Med. 2007 May-Jun;8(4):388–389. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00304.x. author reply 390-1.

- Akbas M, Gunduz E, Sanli S, Yegin A. Sphenopalatine pulsed radiofrequency treatment in patients suffering from chronic face and head pain. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2016 Jan-Feb;66(1):50–54. doi:10.1016/j.bjane.2014.06.001.

- Grandhi RK, Kaye AD, Abd-Elsayed A. Systematic review of radiofrequency ablation and pulsed radiofrequency for management of cervicogenic headaches. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018 Feb 23;22(3):18. doi:10.1007/s11916-018-0673-9

- Abd-Elsayed A, Kreuger L, Seeger S, Dulli S. Pulsed radiofrequency for treating trigeminal neuralgia. Ochsner J. 2018 Spring;;18(1):63–65. doi:10.1177/0333102413485658.

- Chua NH, Halim W, Evers AW, Vissers KC. Whiplash patients with cervicogenic headache after lateral atlanto-axial joint pulsed radiofrequency treatment. Anesth Pain Med. 2012;1(3):162–167. doi:10.5812/kowsar.22287523.3590. Winter

- Xiao X, Chai G, Liu L, Jiang L, Luo F. Long-term outcomes of pulsed radiofrequency for supraorbital neuralgia: a retrospective multicentric study. Pain Physician. 2022 Oct;25(7):E1121–E1128.

- Makharita MY, Amr YM. Pulsed radiofrequency for chronic inguinal neuralgia. Pain Physician. 2015 Mar-Apr;18(2):E147–55.

- Chang MC. Efficacy of pulsed radiofrequency stimulation in patients with peripheral neuropathic pain: a narrative review. Pain Physician. 2018 May;21(3):E225–E234.

- Abd-Elsayed A, Martens JM, Fiala KJ, Izuogu A. Pulsed radiofrequency for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2022 Dec;26(12):889–894. doi:10.1007/s11916-022-01092-0.

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng H-Y, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi:10.1136/bmj.l4898.

- Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi:10.1136/bmj.i4919.

- Moga C, Guo B, Schopflocher D, Harstall C. Development of a quality appraisal tool for case series using a modified delphi technique. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: Institute of Health Economics; 2012.

- Cohen SP, Peterlin BL, Fulton L, Neely ET, Kurihara C, Gupta A, Mali J, Fu DC, Jacobs MB, Plunkett AR, et al. Randomized, double-blind, comparative-effectiveness study comparing pulsed radiofrequency to steroid injections for occipital neuralgia or migraine with occipital nerve tenderness. Pain. 2015;156(12):2585–94. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000373.

- Gabrhelik T, Michalek P, Adamus M. Pulsed radiofrequency therapy versus greater occipital nerve block in the management of refractory cervicogenic headache – a pilot study. Prague Medl Rep. 2011;112:279–187.

- Alkaabi R, Hussein HS. The role of pulsed radiofrequency for greater and lesser occipital nerves in the treatment for migraine. Eur J Mol Clin Med. 2020;7(1):104–109.

- Batistaki C, Madi AI, Karakosta A, Kostopanagiotou G, Arvaniti C. Pulsed radiofrequency of the occipital nerves: results of a standardized protocol on chronic headache management. Anesth Pain Med. 2021 October;11(5):e112235. doi:10.5812/aapm.112235.

- Li J, Yin Y, Ye L, Zuo Y. Pulsed Radiofrequency of C2 dorsal root ganglion under ultrasound-guidance and CT confirmed for chronic headache: follow-up of 20 cases and literature review. J Pain Res. 2020;(13):87–94.

- Vanelderen P, Rouwette T, De Vooght P, Puylaert M, Heylen R, Vissers K, Van Zundert K. Pulsed radiofrequency for the treatment of occipital neuralgia – a prospective study with 6 months of follow-up. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35(2):148Y151. doi:10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181d24713.

- Choi HJ, Oh IH, Choi SK, Lim YJ. Clinical outcomes of pulsed radiofrequency neuromodulation for the treatment of occipital neuralgia. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;51(5):281–285. doi:10.3340/jkns.2012.51.5.281.

- Guner D, Eyigor C. Efficacy of ultrasound-guided greater occipital nerve pulsed radiofrequency therapy in chronic refractory migraine. Acta Neurologica Belgica. 2022;123(1):191–198. doi:10.1007/s13760-022-01972-7.

- Huang JHY, Galvagno JSM, Hameed M, Wilkinson I, Erdek MA, Patel A, Buckenheimer IIIC, Rosenberg J, Cohen SP. Occipital nerve pulsed radiofrequency treatment: a multi-center study evaluating predictors of outcome. Pain Med. 2012;13(4):489–497. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01348.x.

- Lee HJ, Cho HH, Nahm FS, Lee PB, Choi E. Pulsed radiofrequency ablation of the C2 dorsal root ganglion using a posterior approach for treating cervicogenic headache: a Retrospective Chart Review. Headache. 2020;60(10):2463–2472. doi:10.1111/head.13759.

- Li S, Feng D. Pulsed radiofrequency of the C2 dorsal root ganglion and epidural steroid injections for cervicogenic headache. Neurol Sci. 2019;40(6):1173–1181. doi:10.1007/s10072-019-03782-x.

- Van Zundert J, Lame IE, de Louw A, Jansen J, Kessels F, Patijn J, van Kleef M. Percutaneous pulsed radiofrequency treatment of the cervical dorsal root ganglion in the treatment of chronic cervical pain syndromes: A clinical audit. Neuromodulation. 2003;6(1):6–14. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1403.2003.03001.x.

- Karaoglan M, Kucukcay B. Using GON block as a diagnostic block: investigation of clinical efficacy of GON radiofrequency treatmentfor migraine patients. Neurol Asia. 2022;27(4):991–999. doi:10.54029/2022sxa.

- Belgrado E, Surcinelli A, Gigli GL, Pellitteri G, Dalla Torre C, Valente M. A case report of pulsed radiofrequency plus suboccipital injection of the greater occipital nerve: an easier target for treatment of cluster headache. Front Neurol. 2021;12:724746. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.724746.

- Voloshin AG, Moiseeva IV. Combined interventional treatment of refractory chronic migraine. SN Compreh Clin Med. 2021;3(6):1320–1326. doi:10.1007/s42399-021-00868-6.

- Fadayomi O, Kendall MC, Nader A. Ultrasound-guided pulsed radiofrequency of C2 dorsal root ganglion as adjuvant treatment for chronic headache disorders: a case report. A&A Practice. 2019;12(11):396–398. doi:10.1213/XAA.0000000000000942.

- Gonzalez FL, Beltran Blasco I, Margarit Ferri C. Pulsed radiofrequency on the occipital nerve for treatment of short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache: a case report. Cephalalgia Rep. 2020;3:1–4. doi:10.1177/2515816320908262.

- Kwak S, Chang MC. Management of refractory chronic migraine using ultrasound-guided pulsed radiofrequency of greater occipital nerve: two case reports. Medicine. 2018;97(45):45(e13127. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000013127.

- Lee SY, II Jang D, Noh C, Ko YK. Successful treatment of occipital radiating headache using pulsed radiofrequency therapy. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2015;58(1):89–92. doi:10.3340/jkns.2015.58.1.89.

- Li J, Yin Y, Ye L, Zuo Y. Pulsed radiofrequency of C2 dorsal root ganglion under ultrasound guidance for chronic migraine: a case report. J Pain Res. 2018;11:1915–19. doi:10.2147/JPR.S172017.

- VanderHoek MD, Hoang HT, Goff B. Ultrasound-guided greater occipital nerve blocks and pulsed radiofrequency ablation for diagnosis and treatment of occipital neuralgia. Anesthesiology Pain Med. 2013;3(2):256–259. doi:10.5812/aapm.10985.

- Zhang J, Shi D, Wang R. Pulsed radiofrequency of the second cervical ganglion (C2) for the treatment of cervicogenic headache. J Headache Pain. 2011;12(5):569–571. doi:10.1007/s10194-011-0351-3.

- Wahab S, Kataria S, Woolley P, O’Hene N, Odinkemere C, Kim R, Urits I, Kaye AD, Hasoon J, Yazdi C, et al. Literature review: pericranial nerve blocks for chronic migraines. Health Psychol Res. 2023 Apr 29;11:74259. doi:10.52965/001c.74259.

- Simurina T, Mraovic B, Zupcic M, Zupcic SG, Vulin M. Local anesthetics and steroids: contraindications and complications—clinical update. Acta Clin Croat. 2019;Suppl. 1:53–61.

- Ahadian FM. Pulsed radiofrequency neurotomy: advances in pain medicine. Current Pain Headache Rep. 2004;8(1):34–40. doi:10.1007/s11916-004-0038-4.

- Park S, Park JH, Jang JN, Choi SI, Song Y, Kim YU, Park S. Pulsed radiofrequency of lumbar dorsal root ganglion for lumbar radicular pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Pract. 2024 Jan 31.

- Grandhi RK, Kaye AD, Abd-Elsayed A. Systematic review of radiofrequency ablation and pulsed radiofrequency for management of cervicogenic headaches. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2023;22(3):18. doi:10.1007/s11916-018-0673-9.

- Nagar VR, Birthi P, Grider JS, Asopa A. Systematic review of radiofrequency ablation and pulsed radiofrequency for management of cervicogenic headache. Pain Physician. 2015;18:109–30.

- Orhuru V, Huang L, Quispe RC, Khan F, Karri J, Urits I, Hasoon J, Viswanath O, Kaye AD, Abd-Elsayed A. Use of radiofrequency ablation for the management of headache: a systematic review. Pain Physician. 2021 Nov;24(7):E973–E987.

- Vanneste T, Van Lantschoot A, Van Boxem K, Van Zundert J. Pulsed radiofrequency in chronic pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017 Oct;30(5):577–582. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000000502.

- Aggarwal AK, Ottestad E, Pfaff KE, Huai-Yu Li A, Xu L, Derby R, Hecht D, Hah J, Pritzlaff S, Prabhakar N, et al. Review of ultrasound-guided procedures in the management of chronic pain. Anesthesiol Clin. 2023 Jun;41(2):395–470. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2023.02.003.

- Yang M, Rendas-Baum R, Varon SF, Kosinski M. Validation of the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) across episodic and chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2011;31(3):357–367. doi:10.1177/0333102410379890.

- Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner KB, Sawyer J, Lee C, Liberman JN. Validity of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score in comparison to a diary-based measure in a population sample of migraine sufferers. Pain. 2000 Oct;88(1):41–52. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00305-5.