Abstract

RATIONALE: Delivery of pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) varies widely across Canada. There is a need for evidence-based quality indicators (QI) that can be used to identify variations in the quality of PR with the aim of improving health outcomes.

OBJECTIVES: To use an evidence-based, systematic process to develop QI that addresses the process, structure and outcomes of PR.

METHODS: The development process was based on the modified RAND Appropriateness Method that included a systematic review of the literature to identify candidate QI and refinement of these QI by a Working Group before they were sent to a Delphi panel. Panel members rated the importance, scientific soundness, reliability, and feasibility of each candidate using an electronic survey. The results of the survey were distributed to panelists who deliberated by teleconference prior their re-rating the candidate QI.

RESULTS: The literature review identified 5490 titles and abstracts. A total of 1653 articles were retained after initial screening. After full text screening, 190 articles remained and were used to generate 90 candidate QI. The Delphi panel identified 56 QI: 19 structural, 29 process, 8 outcome. The Working Group distilled these to a shorter list of 14 core QI that defined the minimal requirements for PR.

CONCLUSIONS: This process resulted in a comprehensive set of 56 QI and a shorter list of 14 core QI that can be used for evaluation and feedback to improve PR and patient outcomes. Future research to determine standards for the QI will support the development and assessment of strategies to improve PR.

Résumé

JUSTIFICATION: La mise en oeuvre des programmes de réadaptation pulmonaire varie grandement d’un endroit à l’autre au Canada. Des indicateurs qualitatifs fondés sur les données probantes pouvant être utilisés pour cerner les variations dans la qualité de la réadaptation pulmonaire sont nécessaires afin d’améliorer les issues de santé.

OBJECTIFS: Utiliser un processus systématique fondé sur les données probantes afin d'élaborer des indicateurs qualitatifs portant sur le processus, la structure et les résultats de la réadaptation pulmonaire.

MÉTHODES: Le processus d’élaboration a été réalisé à l’aide de la version modifiée de la méthode RAND de détermination de la pertinence, comprenant une revue systématique de la littérature ayant pour but de répertorier les indicateurs qualitatifs candidats et de les soumettre à un groupe de travail pour qu’ils soient affinés avant d’être acheminés à un panel Delphi. Les membres du panel ont coté l’importance, la validité scientifique, la fiabilité et la faisabilité de chaque candidat par le truchement d’une enquête électronique. Les résultats de l’enquête ont été distribués aux membres du panel qui ont ensuite délibéré par téléconférence avant de coter à nouveau l’indicateur qualitatif candidat.

RÉSULTATS: La revue de littérature a permis de recenser 5 490 titres et résumés. De ce nombre, 1 653 articles ont été retenus après une première lecture. Après une lecture plus approfondie, 190 d’entre eux ont été retenus et ont été utilisés pour produire 90 indicateurs qualitatifs candidats. Le panel Delphi a recensé 56 indicateurs qualitatifs : 19 portant sur la structure, 29 sur le processus et 8 sur les résultats. Le groupe de travail a ensuite distillé ces indicateurs pour en arriver à une liste plus courte de 14 indicateurs qualitatifs de base définissant les exigences minimales pour la réadaptation pulmonaire.

CONCLUSIONS: Ce processus a produit un ensemble exhaustif de 56 indicateurs qualitatifs et à une liste de 14 indicateurs qualitatifs de base, qui peuvent être utilisés pour évaluer et fournir une rétroaction afin d’améliorer la réadaptation pulmonaire et les issues de santé des patients. D’autres études visant à déterminer les normes pour les indicateurs qualitatifs contribueront à l’élaboration et à l’évaluation des stratégies pour améliorer la réadaptation pulmonaire.

Introduction

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is a cornerstone therapy for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other chronic lung diseases.Citation1 In Canada, most PR programs are situated in urban hospitals, but there is a growing trend for programs to be in non-hospital locations, such as community or health centers in smaller communities.Citation2 This change in setting of PR programs is particularly pertinent for rural Canada, where there is a greater prevalence of chronic respiratory diseases such as COPDCitation3 and where the population in general experiences higher mortality, exposure to risk factors and hospitalization rates.Citation4

Although the expansion of programs into community, rural and remote settings may enable more participants to access PR, one challenge is ensuring high quality of care and minimizing unnecessary variation in clinical practice.Citation5,Citation6 A study by Yohannes et al found that of the 239 PR programs audited in the United Kingdom (UK), 51% of PR programs did not fully meet the required UK standards.Citation7 For instance, only 47% of programs met the standard of having a PR-trained healthcare professional supervising participants’ exercise training, and 6% of programs did not have any staff supervision of participants. The 2018 report by Steiner and colleagues reports the results of UK PR audits in 2015 and 2017.Citation8 They note progress in the number of programs meeting the quality standards but also that improvement is needed when, for example, only 27% of programs assess muscle strength. Similarly in Canada, the Canadian Thoracic Society PR survey found that while 90% of programs reported that they delivered resistance training, only one-third of them used an assessment of muscle strength to prescribe training intensity.Citation9 In addition, the most common method of prescribing aerobic exercise intensity was by measuring oxygen saturation and dyspnea, a practice that does not follow recommended guidelines of exercise prescription.Citation10 Twenty percent of Canadian programs did not have emergency equipment or protocols in place and 10% did not have supplemental oxygen for exercise training. The findings in the UK and Canada suggest that there is heterogeneity in the implementation of PR programs, which may affect the quality of patient care and outcomes. Many factors may contribute to this heterogeneity including differences in: health care professionals’ skill sets, funding methods, health authority policies and settings in which PR programs are delivered. However, it is important that PR programs follow best practices to ensure quality and consistency to improve patient outcomes.Citation8

An important step to confirm the quality of PR programs in Canada is to develop quality indicators (QI) to identify optimal program delivery.Citation5,Citation11 QI are statements that provide information about the quality of a specific healthcare service, and point to the necessary structures, processes and outcomes that must be in place. Quality indicators are different from clinical practice guidelines, which are statements that facilitate healthcare professional clinical decision making.Citation12 Although QI for PR have been developed in SpainCitation13 and the United Kingdom,Citation7 none have been developed for use in Canada. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to develop quality indicators for Canadian PR programs based on the most recently available literature.

Methods

Overview

A nine-person Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS) working group was created to guide QI development. Members of the working group were recruited from the COPD, ILD and Respiratory Health Professionals assemblies of the CTS. The committee consisted of nine academic clinicians and one graduate student in the disciplines of physical therapy, respirology and exercise physiology. Working group members had research and clinical expertise in pulmonary rehabilitation as well as experience in QI development. Quality indicators were developed using a process based on the Modified RAND Appropriateness Method.Citation14,Citation15 This consisted of a systematic review of the literature to identify potential QI, followed by a Delphi exercise to select the final QI.

Systematic review of the literature

We used the following question to guide our search: In hospital (inpatient and outpatient), community, home and telehealth settings, what are the evidence-based structural, process and outcome elements of pulmonary rehabilitation associated with such benefit that not having them will affect patient outcomes?

Search strategy

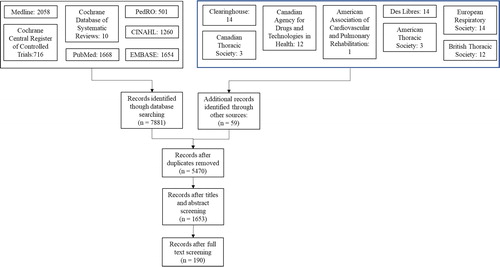

The search strategy was created with support from a medical librarian from the University of British Columbia. We searched for guidelines and statements, randomized clinical trials and gray literature related to PR and to exercise interventions for people with chronic lung disease. The search strategy (see Online Supplement) included terms aimed at identifying publications addressing pulmonary rehabilitation procedures including exercise in diseases commonly seen in PR (COPD, asthma, interstitial lung diseases, pulmonary hypertension, lung cancer and cystic fibrosis) and were limited to studies that recruited adults (19 years and older) and were written in English or French. The search strategy was performed in the following databases: Medline OVID, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDRo), Des Libres, National Guidelines Clearinghouse and Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). Guidelines and toolkits relating to PR were also searched in the following websites: American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (AACVPR), American Thoracic Society (ATS), Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS), European Respiratory Society (ERS) and British Thoracic Society (BTS).

Screening of titles and abstracts

The titles and abstracts were uploaded to the systematic review software Covidence (Covidence, Melbourne, Australia) for removal of duplicate titles and title/abstract screening based on pre-specified inclusion/exclusion criteria. Pulmonary rehabilitation was defined as an intervention lasting more than one session that included exercise training and education in the home, hospital, community, or telehealth settings. Articles were selected if they reported data about exercise training, education and self-management in PR programs; or were primary research studies on exercise training in chronic lung disease populations. We also included studies of exercise programs for people with chronic lung disease conducted in a research setting (with or without education or behavioral modification) that aimed to create potential QI specific to exercise. Studies from randomized controlled trials, observational studies, audits, technology reports, systematic reviews, consensus statements and guidelines were included. We excluded studies that solely investigated adjunct therapies in PR, such as Tai Chi, singing or dancing. Studies that focused on biomarkers or imaging measures as the primary research outcome were excluded. Two members of the research team screened all the titles and abstracts. Conflicts were resolved by another member of the research team.

Data collection

A data extraction form based on the work of Kelley and HurstCitation16 and DonabedianCitation17 was used and piloted on five eligible articles. After revision, the final data extraction form included 23 fields related to program structure, 35 fields related to program process and 12 fields related to program outcomes. Two reviewers extracted data from eligible articles. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer.

Systematic review data synthesis

Creation of candidate QI was guided by methods described by Zidarov et al.Citation18 The methods and results of each paper were examined to create candidate QI. Once all papers were reviewed and the list of candidate QI was created, a frequency count was generated to measure the number of times that an individual indicator appeared in the published literature.

Selection of quality indicators by a Delphi panel

Selection of panelists

The panel was composed of a multidisciplinary group of health professionals working or conducting research in PR programs in Canada and a patient who had participated in PR. In Canada, there are ten different healthcare disciplines typically involved in PR programs; however, only five of these (respiratory therapists, dietitians, physiotherapists, nurses, kinesiologists and physicians) are involved in more than 50% of the programs.Citation2 One to two professionals from each of these five disciplines were invited to be on the panel.

The potential list of candidates for the panel was generated from members of the Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS). The Working Group reviewed the characteristics of those who responded and invited individuals to be panelists based on discipline, geographic representation, and work setting. The invitation described the purpose of the study, the study methodology, including the systematic review used to generate the candidate QI and the Delphi process.

Rating of quality indicators

FluidSurveys online software (SurveyMonkey, Ottawa, ON, Canada) was used to rate the QIs. The panelists reviewed the definition, quality dimension (structure, process or outcome), supporting evidence, and frequency counts for each of the candidate QI. The survey also provided the bibliography and links to the pdfs that supported each candidate QI. Using the framework method developed by Kelley and HurstCitation16, the panelists rated each candidate QI on four criteria: importance, scientific soundness, reliability and feasibility of measurement, using a 9-point Likert Scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Undecided, 9 = Strongly Agree) (). Panelists could also add additional candidate QI if they wished and were invited to add comments throughout the survey. At the end of the four weeks the survey was closed, and the panel no longer had access to change their answers. The survey data was exported into spreadsheet for analysis.

Table 1. Definition of candidate quality indicator criteria.

Calculation of QI appropriateness, inappropriateness and disagreement scores

We followed the methodology of Fitch et alCitation19 and Esrailian et alCitation20 to determine if each candidate QI was considered “acceptable” or “not acceptable” based on the panelists’ scores. This assessment was applied to each criterion (importance, scientific soundness, reliability, feasibility) for each candidate indicator. A median Likert score of 7 to 9 identified acceptable QI; a median Likert Score 1 to 3 indicated QI were not acceptable, and QI had uncertain acceptability if the median Likert score was 4 to 6.

In addition to evaluating median scores, we calculated a disagreement index (DI) for each criterion for each candidate quality indicator to determine the amount of variability around the scores. The Likert scores’ interpercentile range (IPR) and the interpercentile range adjusted for symmetry (IPRAS) were calculated. The DI was calculated by dividing the IPR by the IPRAS. A DI greater than 1 indicated that the median and distribution of scores was outside the 30th and 70th percentiles even after adjusting for asymmetries. A DI less than 1 indicated agreement among the panelists.

Candidate QI that panelists agreed were unacceptable (all criteria: importance, scientific soundness, reliability and feasibility received a median Likert score between 1 and 3) were discarded. Candidate QI that the panelists agreed were acceptable (based on all categories receiving a median Likert score between 7 and 9) were retained. QI that were classified as uncertain (a Likert score on any category between 4 and 6) and/or a disagreement score greater than one (DI > 1) on any criterion were then discussed in a teleconference meeting of the expert panel.

Panel discussion and final round

Each panelist was invited to attend one of four panel discussions conducted via teleconference using Adobe Connect (Adobe, San Jose, CA). The panelists discussed each candidate indicator that had at least one criterion rated as ‘uncertain’ or with a DI > 1. Following the meeting, a transcript summarizing the content of all teleconferences was given to the panelists as a guide. Panelists re-rated each indicator discussed during the teleconferences via FluidSurvey. QIs were retained when there was agreement that all four criteria were acceptable.

Results

Systematic review

A total of 7940 titles and abstracts were retrieved from the databases and gray literature searches. After removal of duplicates, 5490 studies remained. A total of 1653 articles were retained after initial screening of titles and abstracts. After full text screening, 190 articles remained and were used to generate the candidate QI. From these articles, 90 candidate QI were identified: 22 structural indicators, 53 process indicators and 15 outcome indicators ().

Panelist characteristics

Fourteen Canadian PR experts were invited as panelists and 11 agreed to participate in the study. A patient also agreed to participate on the panel. The panelists represented different healthcare professions in PR (physical therapists, physicians, academics, nurses, pharmacists and respiratory therapists) and seven Canadian provinces. The patient had COPD and had completed a PR program approximately one year prior to the study. Panel members had 5 to 30 years’ experience working in PR. Six panelists had 5–10 years of experience, three panelists had 11–20 years of experience, and three had 21–30 years of experience. Many of our panelists were clinicians (9), involved in creating PR-related health policy (4), or had published peer-reviewed research in PR (3).

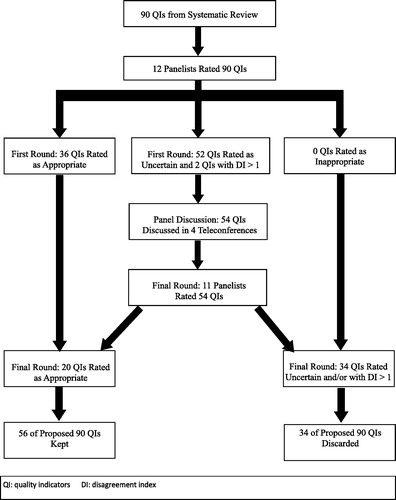

First round rating and panel discussion

displays the QI development process. Panelists rated 36 of the 90 candidate QIs (40%) as acceptable and the remaining 54 (60%) as either “uncertain” or there was disagreement on at least one of the four criteria. “Reliability” and “feasibility” were the two criteria with the lowest ratings. Ten of the 12 panelists participated in a TC to discuss the 54 candidate QIs that were uncertain or controversial. The purpose of the discussions was not to reach consensus, but rather to clarify misconceptions and expose each panelist to other perspectives they may not have considered when they were rating in the first round. Each discussion was two and a half hours long.

Final round rating

Following the teleconference discussion, the panelists re-rated the 54 candidate QI previously considered uncertain. Of these, 20 (37%) were deemed acceptable and were retained, and 34 (63%) were discarded, bringing the final list of QIs to 56 (36 from the first round, plus the 20 from the second round). The 56 QI consisted of 19 structural QI, 29 process QIs and 8 outcome QIs (see Online Supplement).

Core list of quality indicators

The Working Group then created a list of 14 “core” QI derived from the larger list of 56 QI. This process was achieved by determining which QIs could be combined (e.g. QI that specified similar lists of equipment and other physical resources), and QI that were clearly required for any health care intervention to occur (e.g., need for informed consent for treatment). Thus, the distinction between process, structure and outcome QI was not maintained in the core list. The purpose of the core list of 14 QI was to provide pulmonary rehabilitation programs with a short list of fundamental PR components, with accompanying guidance notes that can be used for frequent program quality audits ( and ).

Table 2. Core quality indicators for Canadian pulmonary rehabilitation programs.

Table 3. Guidance notes to assist interpretation of core indicators for Canadian pulmonary rehabilitation programs.

Discussion

We developed a comprehensive list of 56 QI using the Modified RAND Appropriateness Method. A Working Group representing members of the CTS with expertise in PR and QI conducted the systematic review that generated candidate QI. A Delphi process using the expertise of clinicians and academics with interest and experience in PR, and a patient representative rated the importance, scientific soundness, reliability and feasibility of each candidate QI to generate the final list of 56 QI. The Working Group distilled the list to 14 core items for pulmonary rehabilitation programs in Canada. These evidence-based QI represent a tool to assess the quality of PR across Canada, implement quality improvement strategies and subsequently evaluate the success of those strategies. Such activities can lead to improved outcomes for people attending PR and support initiatives to expand the availability of PR in Canada.

Although QI for PR have been developed in the UK and in Spain, neither explicitly described the methodology used in their development.Citation7,Citation13 Güell et al reported that their QI were developed by a single group of investigators.Citation13 Pairs of authors developed the QI for a particular patient population and these were subsequently reviewed by all the authors. Revisions were made until the group reached consensus. Yohannes et al reported that they developed their QI statements based on guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence and the BTS.Citation7 We used rigorous methodology based on the Modified RAND Appropriateness Method that allowed us to minimize biases that may have been inherent in the creation of QI in other jurisdictions. Development of our candidate QI was based on a systematic review of the literature and not limited to existing guidelines. This ensured that we had a comprehensive list of high quality QI. Our Working Group, consisting of academic clinicians with experience in QI development and PR, provided the necessary expertise to develop a realistic set of candidate QI. Using a Delphi process that included clinicians and academics, separate from the Working Group, as well as a patient to determine the final set of QI helped to reduce personal bias. Patients were not included in the development of either of the European QI sets. Voting on the candidate QI was done using an electronic survey system providing anonymity of responses. Appropriateness of the candidate QI was analyzed mathematically to further reduce bias. Therefore, we are confident that our development process and the decision makers involved have ensured an unbiased, comprehensive set of high quality QI.

The need for a unique set of Canadian QI was driven by the recognition that QI are not easily transferable among countries. For instance, Spruit et al noted that respiratory therapists, who are frequently involved in delivering PR in Canada, are not a recognized profession in Europe.Citation11 Similarly, Desveaux and her colleagues reported that physiotherapists played a key role in delivering PR in the UK, Sweden and Canada but they were employed in less than 50% of PR programs in the US.Citation21 The Spanish QI include respiratory physical therapy, which has no specific definition in Canada.Citation13 Güell et al organized the Spanish QI into 5 sections addressing: indications for PR, evaluation of participants, program components, program characteristics and administrative components in the implementation of RR.Citation13 These were assessed for each of 5 “disease groups,” which can make evaluating QI unwieldly. The UK QI focus on patients with COPD.Citation7 Our core set of 14 QI are largely applicable to any participant in PR. In addition to international differences in the appropriateness of QI, the Canadian survey highlighted a wide variation in delivery of PR across the country.Citation2,Citation9 Undoubtedly, most clinicians who deliver PR programs believed that they were delivering service according to current guidelines. However, Eccles et al reported that health care professionals overestimate their adherence to clinical guidelines by 20–30%.Citation22 Our QI are sensitive to this practice variation and provide specific criteria for exercise testing and prescription, in contrast to the UK QI set.Citation7 Thus, our QI have the potential to stimulate improvements in PR that are specific to the Canadian context.

Quality indicators have been the foundation of ongoing program audits in England and Wales.Citation8 Audits in 2015 and 2017 have demonstrated improvements in program completion rates that are known to result in better health outcomes, a greater number of written discharge exercise programs, and an increase in muscle strength assessments. Quality indicators can be valuable in guiding the development of new models of PR delivery and assessing their subsequent performance. The recent Canadian survey noted an increase in community-based and tele-rehabilitation programs. As well as home-based PR, these models offer ways to improve limited access to PR in Canada, which can occur due to distance from the program sites and the cost of transportation. However, it will be important to ensure program quality and associated health benefits linked to high quality PR are not compromised.Citation23

It is essential that QI are worded to facilitate an audit process. Our QI are explicit and have avoided the pitfalls of using terms like “should,” which has been used in previous QI.Citation13 We have also tried to avoid ambiguity that is demonstrated in the 2008 audit of UK PR programs.Citation7 In that document one quality indicator requires the program is delivered by a multidisciplinary team and that the indicator is ‘only partially met’ if the rehabilitation program has contributions from only physiotherapists and respiratory nurses. This implies that physiotherapists and respiratory nurses do not meet the definition of a multidisciplinary team but there is no guidance on how to achieve full compliance with the indicator. We believe our QI have clarity and specificity that will facilitate audit processes.

Limitations

There are some limitations in the QI we have developed. Most of the literature informing the list of candidate QI is based on PR for people with COPD. Increasingly people with interstitial lung diseases, asthma, lung transplantation, pulmonary hypertension and other respiratory conditions are enrolled in PR. Our QI may not reflect certain aspects of quality treatment for these patients. Although we included a patient representative with COPD on our Delphi panel, broader patient representation may have strengthened the development process.

We did not have the Delphi panel discuss the full list of 56 QI. It is possible that QIs considered “acceptable” or “unacceptable” could have had a different decision after a discussion. However, we believe that our list of 14 core competencies reflects high standards and would be feasible for use in an external or self-assessment audit. In addition, the full list of 56 QIs are presented such that programs that have the capacity may conduct a more detailed audit of their program. Although we took great care to limit personal bias in the development process, it is possible that the QI could change with a different Delphi panel. This is not unique to our work, but a potential limitation when utilizing this development methodology.

Conclusion

We used a rigorous evidence-based systematic approach, based on the modified RAND Appropriateness Method, to develop 14 core QI that address the key aspects of delivery and assessment of PR. The development process was informed by a systematic literature review, the results of the most recent Canadian PR survey, as well as quantitative and qualitative assessments by academic and clinical experts in the field of PR, and a patient representative. These QI can be used to develop and assess strategies to improve PR at the local, provincial or national level. The QI are based primarily on data from PR involving people with COPD but can be used as a framework to explore whether modifications for specific patient populations are needed. Future work needs to assess the feasibility of using these QI in varied PR settings in Canada, and globally. Finally, work to determine achievable benchmarks for each of the QI are needed such that this information can be combined with feedback on performance and goal setting to improve quality of care and patient outcomes.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17.4 KB)Additional information

Funding

References

- Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, et al. An official American thoracic society/European respiratory society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13–e64.

- Camp PG, Hernandez P, Bourbeau J, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation in Canada: a report from the Canadian thoracic society COPD clinical assembly. Can Respir J. 2015;22(3):147–152. doi:10.1155/2015/369851.

- Camp PG, Platt H, Road JD. Rural areas bear the burden of COPD: an administrative data analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:A634.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Disparities in primary health care experiences among Canadians with ambulatory care sensitive conditions CIHI; 2012. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/PHC_Experiences_AiB2012_E.pdf. Accessed September 2018

- Rochester CL, Vogiatzis I, Holland AE, et al. An official American thoracic society/European respiratory society policy statement: enhancing implementation, use, and delivery of pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(11):1373–1386. doi:10.1164/rccm.201510-1966ST.

- Holland AE. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: has it peaked? Respirology. 2019;24(2):103–104. doi:10.1111/resp.13447.

- Yohannes AM, Stone RA, Lowe D, Pursey NA, Buckingham RJ, Roberts CM. Pulmonary rehabilitation in the United Kingdom. Chron Respir Dis. 2011;8(3):193–199. doi:10.1177/1479972311413400.

- Steiner M, McMillan V, Lowe D, et al. Pulmonary Rehabilitation: An Exercise in Improvement. National Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Audit Programme: Clinical and Organisational Audits of Pulmonary Rehabilitation Services in England and Wales 2017. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2018.

- Dechman G, Hernandez P, Camp PG. Exercise prescription practices in pulmonary rehabilitation programs. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med. 2017;2:77–83. doi:10.1080/24745332.2017.1328935.

- Riebe D, Ehrman JK, Liguori G, Magal M, eds. Exercise prescription for populations with other chronic diseases and health conditions. In: ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2018.

- Spruit MA, Pitta F, Garvey C, et al. Differences in content and organisational aspects of pulmonary rehabilitation. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(5):1326–1337. doi:10.1183/09031936.00145613.

- Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall M. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11(4):358–364. doi:10.1136/qhc.11.4.358.

- Güell MR, et al. Standards for quality care in respiratory rehabilitation in patients with chronic pulmonary disease. Arch Broncopneumol. 2012;48:396–404.

- Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, et al. Improving the quality of health care: research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. Br Med J. 2003;326(7393):816–819. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7393.816.

- Shekelle PG, Kahan JP, Bernstein SJ, et al. The reproducibility of a method to identify the overuse and underuse of medical procedures. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(26):1888–1895. doi:10.1056/NEJM199806253382607.

- Kelley E, Hurst J. Health care quality indicators project: conceptual framework. Health Care. 2006;1–37.

- . Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):691–729. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x.

- Zidarov D, Visca R, Gogovor A, Ahmed S. Performance and quality indicators for the management of non-cancer chronic pain: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010487. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010487.

- Fitch K, Berstein S, Aguilar M, et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User’s Manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2001.

- Esrailian E, Spiegel BM, Targownik LE, et al. Differences in the management of Crohn’s disease among experts and community providers, based on a national survey of sample case vignettes. Aliment Pharmacol. 2007;26(7):1005–1018. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03445.x.

- Desveaux L, Janaudis-Ferreira T, Goldstein R, Brooks D. An international comparison of pulmonary rehabilitation: a systematic review. COPD J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis 2015;12(2):144–153. doi:10.3109/15412555.2014.922066.

- Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, et al. Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(2):107–112. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.09.002.

- Lacasse Y, Cates CJ, McCarthy B, Welsh EJ. This Cochrane review is closed: deciding what constitutes enough research and where next for pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;11:ED000107.