Abstract

RATIONALE

A comprehensive understanding of the burden of illness and management strategies for severe asthma (SA), especially by disease control, is lacking in Canada.

OBJECTIVES

The objectives of this study were to describe treatments, exacerbation outcomes and healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) for patients with controlled and uncontrolled SA in Alberta, Canada.

METHODS

A retrospective cohort of SA patients 12+ years (April 1, 2011 to March 31, 2020) was identified from administrative health data, based on medication dispensed for controlling asthma symptoms, stratified by disease control at index. Treatment patterns were analyzed for incident SA patients. Annualized exacerbation incidence rate ratios (IRR) were estimated throughout follow-up and stratified by disease control at index. Asthma-specific HCRU and direct costs were calculated.

RESULTS

The study cohort included 74,134 patients (12.4% of eligible asthma patients) of whom 71,099 (95.5%) were classified as controlled and 3,035 (4.1%) as uncontrolled at index. Inhaled corticosteroid + long-acting beta agonist (ICS + LABA) was the most frequent first-line therapy among incident SA patients (n = 53,084), received by 42.7% of patients. A minority received >2 lines of therapy; few received triple therapy. The uncontrolled (at index) versus controlled (at index) cohort had a 5.5 times higher exacerbation rate (IRR: 5.5, 95% CI: 5.1–5.8; p < 0.001), higher HCRU, and higher associated annual costs (mean [SD]: $3,799 [$6,668] uncontrolled vs $1,339 [$2,515] controlled).

CONCLUSIONS

SA, whether controlled or uncontrolled at index, was associated with ongoing exacerbations and HCRU despite treatment intensification that identified patients as having SA. Some treatment patterns appeared misaligned with guidelines, suggesting potential need for better recognition of asthma severity and escalating therapies.

RÉSUMÉ

JUSTIFICATION:

Le Canada ne dispose pas d’une compréhension globale du fardeau de la maladie et des stratégies de prise en charge de l’asthme sévère, en particulier en ce qui concerne la lutte contre la maladie.

OBJECTIFS:

Décrire les traitements, les résultats des exacerbations et l’utilisation des ressources de soins de santé pour les patients atteints d’asthme sévère maitrisé et non maitrisé en Alberta, au Canada.

MÉTHODES:

Une cohorte rétrospective de patients atteints d’asthme sévère âgés de 12 ans et plus (entre le 1er avril 2011 et le 31 mars 2020) a été constituée à partir de données administratives sur la santé, sur la base des médicaments administrés pour maîtriser les symptômes de l’asthme, stratifiés en fonction de la maitrise de la maladie au départ. Les schémas de traitement ont été analysés pour les patients atteints d’asthme sévère incident. Les ratios de taux d’incidence des exacerbations annualisés ont été estimés tout au long du suivi et stratifiés en fonction de la maitrise de la maladie au départ. L’utilisation des ressources de soins de santé spécifique à l’asthme et les coûts directs ont été calculés.

RÉSULTATS:

La cohorte de l’étude comprenait 74 134 patients (12,4 % des patients asthmatiques admissibles), dont 71 099 (95,5 %) étaient classés comme maitrisés et 3 035 (4,1 %) comme non maitrisés au départ. ICS + LABA était le traitement de première intention le plus fréquent chez les patients atteints d’asthme sévère incident (n = 53 084), reçu par 42,7 % des patients. Une minorité a reçu >2 lignes de traitement; peu ont reçu une trithérapie. La cohorte non maitrisée (au départ) par rapport à la cohorte maitrisée (au départ) avait un taux d’exacerbation 5,5 fois plus élevé (RTI : 5,5, IC à 95 % : 5,1-5,8; p < 0,001), une utilisation des ressources de soins de santé plus élevée et des coûts annuels associés plus élevés (moyenne [ET] : 3 799 $ [6 668 $] non maitrisé comparativement à 1 339 $ [2 515 $] maitrisé).

CONCLUSIONS:

L’asthme sévère, qu’il soit maitrisé ou non maitrisé au départ, était associé à des exacerbations continues et à l’utilisation des ressources de soins de santé malgré l’intensification du traitement chez les patients ayant été recensés comme ayant un asthme sévère. Certains schémas de traitement semblaient mal alignés avec les lignes directrices, ce qui porte à croire qu’il existe un besoin potentiel d’une meilleure reconnaissance de la gravité de l’asthme et de l’escalade des traitements.

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic lung disease affecting approximately 8–10% of the population across Europe and North America.Citation1–4 Asthma exacerbations are characterized by wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness and cough, which may be triggered by exercise, allergens or irritants or viral respiratory infections.Citation5,Citation6 While mitigation strategies can help control asthma symptoms, severe asthma (SA) is particularly burdensome, requiring extensive medication use to help control symptoms. Furthermore, uncontrolled asthma is a persistent problem marked by continuing symptoms and/or frequent or serious exacerbations.Citation7

SA comprises approximately 5–10% of asthma diagnoses yet is responsible for up to 50% of direct costs.Citation8 A Canadian study estimated annual direct costs in mild asthma to be $279.48 per patient, increasing to $2,709.91 in SA.Citation9 Evidence from Europe and North America supports this pattern;Citation10 the added expense can be largely attributed to high levels of medication use and more frequent exacerbations, emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions.Citation7 Individuals with SA also experience lower quality of life (QoL) than those with milder forms of the disease. Heavy symptom burden, frequent exacerbations and medication side effects can interfere with activities of daily living, sleeping, and the socioeconomic aspects of life.Citation8,Citation9,Citation11 Cumulatively, this translates into higher indirect costs to society via absenteeism and presenteeism.Citation10,Citation12

The most recent Canadian guidelines recommend initiating treatment with short-acting beta agonists (SABA) and/or inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) before increasing ICS doses or adding additional therapies.Citation13 If asthma remains uncontrolled after high-dose ICS plus long-acting beta agonists (LABA), then phenotyping and subsequent consideration of biologic therapy is advised.Citation8 Despite improved SA treatment options over time, epidemiological studies worldwide generally show that a high burden of illness remains, and uncontrolled symptoms persist in a subset of individuals.Citation11

Asthma control is a key determinant in the individual and economic burden of the disease, driving costs and impacting QoL.Citation4,Citation14 Uncontrolled asthma is generally considered to reflect poor symptom control, frequent severe exacerbations, airflow limitation or any combination of these criteria.Citation8 A clearer understanding of uncontrolled SA, including treatment patterns and HCRU, is crucial for identifying areas of unmet need and informing solutions to improve quality of care. Although previous publications have examined this, there is marked heterogeneity in the clinical definitions and experimental designs employed, and limited real-world, population-level data to inform patient management more broadly.Citation15

Here we aimed to understand the burden of SA overall and in subcohorts with controlled versus uncontrolled SA. Our objectives were to describe the treatment patterns, exacerbations and HCRU and costs among patients living with SA in Alberta, Canada.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective population-based cohort study of patients identified as having SA in Alberta, Canada. Population-based administrative data were acquired from the province-wide universal healthcare system, Alberta Health (Online Supplementary Material 1).

Case definitions

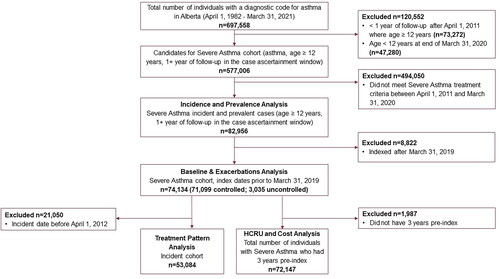

The SA cohort was derived from individuals aged 12+ identified in Alberta Health’s asthma chronic disease cohortCitation16 between April 1, 1982 and March 31, 2020. The 12+ age cutoff aligned with adolescent and adult Canadian guidelines for managing SA.Citation8 Specific inclusion criteria are in Online Supplementary Material 2. SA patients were identified based on medications dispensed in concordance with the 2017 CTS SA guidelines (ie, a high average daily dose of ICS) plus a second controller medication in the year prior to index (defined a subsequent section), or use of an oral corticosteroid (OCS) for 50% of the days in the year prior.Citation8 The initial case ascertainment period for identifying SA patients was April 1, 2011 to March 31, 2020. Prevalent cases, identified prior to the study period, were assigned an index date of April 1, 2011. Incident patients indexed in fiscal year 2019 were excluded to allow adequate follow-up time.

Index date was the first date a patient satisfied all SA inclusion criteria. Each patient was followed from their index date until date of death, discontinuation of registration in Alberta or end of study period; whichever occurred first. Patients satisfying the SA definition were stratified as controlled or uncontrolled (defined in Online Supplementary Material 2) based on individual exacerbation history in the pre-index year.

Patient characteristics at index and exacerbation episodes were studied for the total SA cohort (with 1 year of follow-up). A treatment-pattern analysis was performed on incident SA patients, to capture treatment regimens (referred to here as lines of therapy) from 1 year pre-identification of SA and during follow-up. HCRU and costing analyses were restricted to patients with at least 3 years of pre-index data and 1 year of post-index follow-up, to observe the impact of treatment intensification.

Variables

Demographic and clinical variables included age at index date, sex, geography/health zone of residence, comorbid COPD, chronic OCS use and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). The CCI was derived using weights from Quan et al.Citation17 based on information in the Discharge Abstract Database (DAD), National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS), and Practitioner Claims 1 year prior to and including index date. Methods for classifying medications and analyzing lines of therapy are provided in the Online Supplementary Material 3.

Outcome variables included hospitalizations, ED visits, physician encounters and medication use. Exacerbation episodes were identified as a hospitalization or ED visit with asthma in the primary diagnosis position or an OCS burst. Bursts were defined as ≥1 OCS dispensation with an average daily dose of ≥20 mg of prednisone for 3-28 days, and 1 physician visit or an ED visit with a primary diagnosis of asthma within 7 days of the pharmacy dispense. Although linking the OCS burst to a physician or ED visit provided a conservative estimate of OCS-burst exacerbations, it prevented the overestimation that would occur if based solely on OCS dispenses. Exacerbation events within 48 h of each other were combined into a single exacerbation episode. A hierarchy was used to classify exacerbations events, to prevent double counting, where hospitalizations > ED visits > OCS bursts. Exacerbation duration was based on all events within a single episode (eg, OCS burst time and hospitalization time).

Asthma-specific HCRU was counted whenever an asthma ICD10-CA or ICD9-CM code was recorded in the first diagnosis position, or for SA medication dispenses. SA-related direct cost estimates are described in Online Supplementary Material 4. Statistics Canada’s all-items Consumer Price Index was used to normalize all costs to April 2022 constant Canadian dollars.Citation18

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were summarized descriptively. Lines of therapy (ie, switching patterns or changes in drug class combination) among incident SA patients were analyzed starting from 1 year pre-index and ending at each patient’s end-of-follow-up or fourth-line treatment, whichever came first. The number and proportion of patients receiving each medication type/combination was calculated. To depict lines of therapy, medications were grouped into classes (Online Supplementary Material 3) and evaluated as monotherapy or combinations over time.

The annualized rate of exacerbation episodes per patient and the episode duration were summarized using descriptive statistics, for the total SA cohort and by control status at index. Exacerbation incidence rate ratios (IRR) of index symptom control status were modeled using a multivariate negative binomial regression with cluster-robust standard errors to account for repeat observations for the same individual over time, adjusting for sex, age at index and CCI category at index. Results were derived using generalized estimating equation (GEE) methodology.

For hospitalizations and ED visits, the proportion of patients with at least 1 event and the average duration of stay was reported.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). This study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board of Alberta–Community Health Committee (HREBA.CHC-21-0011). Authors followed reporting standards from the STrengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.Citation19

Results

Patient characteristics

The prevalence of SA increased over the study period (Online Supplementary Material 5). The total SA cohort, as the basis for analyzing patient characteristics and exacerbations, comprised 74,134 patients, which was 12.4% of all eligible asthma patients aged 12+ years in the case ascertainment window ( and Online Supplementary Material 5). Overall, 71,099 (95.9%) were classified as controlled and 3,035 (4.1%) as uncontrolled at index. The minimum number of post-index follow-up years was 1; the maximum was 9 (mean [SD]: 5.3 [2.6] years).

The mean (SD) age at index date was 47.0 (19.6) years; over half were female (58%; ). More patients in the uncontrolled versus controlled at index cohort had CCI scores of 1+ (100% vs 77.8%), indicating comorbidities, and more patients had comorbid COPD (15.0% controlled vs 8.3% uncontrolled at index). Most patients lived in urban areas (71.2%); in the uncontrolled cohort the proportion was lower (62.3%).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for the severe asthma cohort by disease control at index date; Alberta, Canada.

Treatment patterns

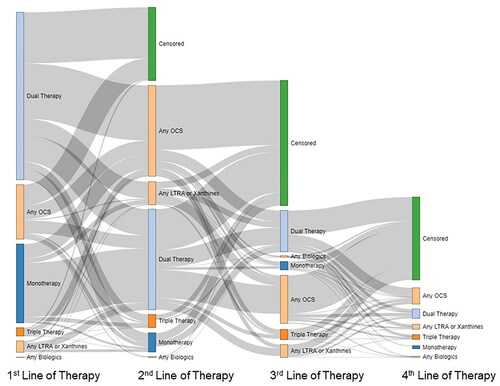

Among 53,084 incident SA patients, most were dispensed combination therapy of inhaled corticosteroid + long-acting beta agonist (ICS + LABA) (42.7%) or SABA monotherapy (16.7%) as the first line of treatment in the pre-index year. First-line OCS alone was dispensed to 7.9% of patients, and few received first-line LABA monotherapy (0.2%). Over three-quarters of patients (77.2%) received second-line treatment, 38.2% received third-line treatment and 12.4% received fourth-line treatment. The proportions initiating treatment during the pre-index year were 75.7, 47.0 and 24.2% for the second-, third- and fourth-line treatments, respectively (Online Supplementary Material 6).

By the fourth-line, OCS add-on therapy (ie, any combination with OCS) was the top fourth-line treatment (37.6%), and triple combinations of ICS + LABA + long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) became more common, yet still infrequent (10.9%). Biologic dispenses were uncommon (3.1%; Online Supplementary Material 6). Patients’ switching patterns are presented in .

Figure 2. Treatment patterns among individuals age 12+ years identified as having severe asthma in Alberta, Canada; fiscal years 2011–2019. The first four lines of therapy were assessed from 1-year pre-index. The height of each bar represents the proportion of patients on each line of therapy. Curves represent the proportion of patients transitioning from one line of therapy to the next. Treatment combinations are defined in Online Supplementary Material 3. Abbreviations: LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; OCS, oral corticosteroid.

Exacerbations

The SD annualized rate of exacerbation episodes per patient during follow-up was 0.11 (0.33), with the uncontrolled versus controlled at index cohort having a 5.5 times higher rate (IRR: 5.5, 95% CI: 5.1–5.8; p < 0.001). Rates in the uncontrolled at index cohort were also higher for inpatient, ED visits, and OCS burst exacerbation types (). Overall, the SD duration of exacerbation episodes was 6.7 (5.7) days (median [IQR]: 5 [4–8] days); hospital-based episodes were notably longer (SD: 10.3 [9.6] days; IQR: 7 [5–13]), both for the controlled and uncontrolled cohorts.

Table 2. Asthma exacerbation episodesa during follow-up by disease control; Alberta, Canada, fiscal years 2012-2019.

HCRU and associated costs

Annualized rates of hospitalization, ED admissions, GP visits and specialist visits were higher for the uncontrolled versus controlled at index cohort (). Within the uncontrolled at index cohort, the annualized medication dispensation rates increased from pre-index to post-index (SD: 10.5 [12.4] to 14.4 [19.1] dispenses), consistent with our definition of SA. The proportion of patients with 1 or more hospitalization or ED admission decreased (27.5-11.9% for hospitalizations; 75.1-46.6% for ED; ).

Table 3. Asthma-specific HCRU by disease controla,b pre-index and during follow-up; Alberta, Canada, fiscal years 2008-2019.

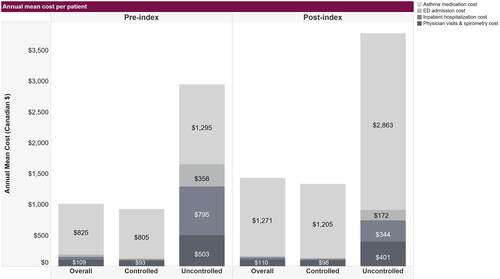

Annual SA-related costs were approximately three times higher for the uncontrolled at index cohort (SD: $2,950 [$4,011] pre-index; $3,799 [$6,668] post-index) than the controlled at index cohort (SD: $933 [$1,566] pre-index, $1,339 [$2,515] post-index). From pre-index to follow-up, the uncontrolled at index cohort had the highest increase in mean medication costs, and a decrease in cost of ED admissions, inpatient hospitalizations and physician visits ().

Figure 3. Annual mean healthcare costs associated with severe asthma in individuals age 12+ years in Alberta, Canada; fiscal years 2012–2019. Costs are per patient in Canadian dollars relative to patient index dates when severe asthma was identified. Some values are not shown; specifically, the pre-index annual mean costs of ED admission and inpatient hospitalizations, respectively, were $35.00 and $44.00 overall and $21.00 and $13.00 in the controlled cohort. The post-index annual mean costs of ED admission and inpatient hospitalizations cost, respectively, were $23.00 and $32.00 overall, and $17.00 and $19.00 in the controlled cohort. Abbreviations: ED, emergency department.

Discussion

The prevalence of SA was observed to increase over time. While our data suggest most SA was controlled (96.0% of patients at index based on exacerbation history), exacerbations persisted throughout follow-up. Although this was true for both patients controlled and uncontrolled at index, patients uncontrolled at index had an annualized rate of exacerbation episodes 5.5 times higher than those with controlled SA at index, as well as higher HCRU and costs. These findings suggest the SA burden, particularly uncontrolled, is considerable, and there may be opportunities to improve symptom management.

Internationally, the published prevalence of uncontrolled SA varies substantially due to differing data sources and definitions of disease control including self-reported control status, with a systematic literature review reporting ranges from 8.0 to 87.4% of individuals with SA.Citation4 As our estimate of 4.1% seems comparatively low, it is possible we underestimated the true prevalence of uncontrolled disease. Our use of administrative data meant that symptoms and clinical characteristics (eg, Asthma Control Test [ACT] score) were not included in our definition, unlike the CTS guidelines.Citation13 Instead, our identification of uncontrolled SA depended on serious exacerbations captured as hospitalizations, ED visits and OCS bursts, which was an operationalized definition of the CTS guidelinesCitation13 and similar to previous studies.Citation20 This approach possibly resulted in a more severe definition. Our lower estimate could have also resulted from our methodological decision to study exacerbation episodes, where exacerbation events within 48 h of each other were combined and counted as a single episode.

It is possible that between-cohort differences at index contributed to the observed differences between controlled and uncontrolled SA patients. Notably, the uncontrolled at index (vs controlled at index) cohort was younger on average, and older adults may have better rates of adherence to asthma medications than their younger counterparts.Citation21 Additionally, a slightly higher proportion of the uncontrolled at index cohort lived in rural areas, where healthcare access may differ. Also, the uncontrolled cohort had higher CCI scores and comorbid COPD, suggesting a larger proportion of unwell patients.

Literature suggests that people with SA, especially when uncontrolled, have higher exacerbation rates and use more healthcare resources than those with mild forms of the disease, and subsequently incur more healthcare costs.Citation4,Citation20 This pattern was supported by our work, and the trends we observed between controlled and uncontrolled at index cohorts aligned with trends reported previously in a United States and United Kingdom study of real world data.Citation20 Despite limited hospitalizations, our estimated post-index annual costs of $1,339 and $3,799 per patient for the controlled and uncontrolled at index cohorts, respectively, align with a previously published estimate of $2,710 based on a small sample of SA patients in Quebec.Citation9 Although the uncontrolled-SA-at-index- cohort accounted for the highest economic burden and HCRU, the controlled-at-index cohort still regularly interacted with the healthcare system, contributing to overall costs. While we did not measure indirect costs, 46% of the SA population was between the ages of 18-49. As such, exacerbations likely had meaningful impacts on work and school absenteeism and presenteeism, possibly contributing to lost productivity.Citation10,Citation12

Although higher costs remained post-index among the uncontrolled-at-index patients, the observed reduction in HCRU suggests that identifying uncontrolled SA, and escalating treatment, may have improved disease control for these patients. If so, then developing strategies for early identification and intervention could be beneficial for reducing healthcare system burden and improving QoL, particularly in those remaining uncontrolled in our cohort.

Although the CTS publishes guidelines on the treatment of asthma, our results indicate that real-world treatment patterns do not always align with these recommendations.Citation8,Citation22 A very small proportion of patients in our incident cohort received LABA and LAMA monotherapies, recommended as add-on or combination therapies, respectively. As both LABA and LAMA monotherapy are recommended to treat COPD, it is possible these treatments corresponded to individuals with comorbid COPD.

SABA monotherapy was identified as a pre-index first-line treatment in 16.7% of patients in our cohort, aligning with previous work.Citation23 While the 2012 CTS guidelines recommended SABA use in mild asthma,Citation22 they also highlighted that persistent/frequent use of SABA is indicative of poor disease control and merits reevaluation of the treatment approach. As the current work focuses on SA, treatment escalation beyond SABA and ICS monotherapies would be expected as an important step in disease management. Our data showed progression to additional lines of therapy both pre- and post-index; however, ICS or SABA monotherapy were still present as fourth-line treatment (typically post-index) in 3.0% and 1.7% of patients, respectively, perhaps as a rapid reliever. Interestingly, more-recent Canadian guidelines from 2021Citation13 suggest an ICS + LABA inhaler may be an alternative to SABA, with some international 2022 recommendationsCitation7 preferring ICS + LABA use given the reduced risk for severe exacerbations and potential for chronic SABA overuse. However, these 2021/2022 guidelines are likely not reflected in our study given the assessment period. Our results, in accordance with recent literature,Citation24,Citation25 did identify ICS + LABA as a common early treatment option and in general, the dual therapy regimens had lower rates of patients requiring subsequent treatment regimens. Biologics in the current study were commonly provided as advanced treatment options, aligning with national and international recommendations. Importantly, biologics other than omalizumab only became available on the public formulary in Alberta in 2018; consequently, our ability to longitudinally track biologic treatment patterns was limited. Additionally, as our treatment-patterns analysis was specific to incident SA patients, it did not reflect all biologic therapy use.

A strength of our study was the use of large, population-based datasets to understand the burden of SA in Alberta. Additionally, this study used a long look-back period (3 years pre-index), enabling ascertainment of historical care information.

While administrative data provided a unique opportunity for real-world evaluation of this topic, there were limitations. Data were not collected for research purposes but for the needs of healthcare administration, which limited our ability to accurately classify patients. Clinical characteristics such as the ACT scores, lung function and other clinical measures were unavailable; we therefore used medication dispensation and HCRU as surrogates to identify SA and classify patients by disease control. Misclassification bias is possible: some patients may have been inaccurately categorized as controlled/uncontrolled at index or as having/not having SA. However, we explored a different categorization of controlled/uncontrolled based on post-index control, in a supplementary post hoc analysis. We found that categorizations based on index symptom control were highly predictive of future control (Online Supplementary Material 7).

Furthermore, while the definition of an OCS-burst exacerbation included a physician or ED visit to increase specificity, it may have underestimated the true number of exacerbations (ie, reduced sensitivity). Additionally, the Pharmaceutical Information Network (PIN) data only captures medication dispensations, not real use or adherence. Therefore, there is potential of misclassification bias if patients were identified as SA based on drug dispensation that did not reflect actual usage. Similarly, while we assumed that two drugs prescribed in an overlapping timeframe indicated simultaneous use, this assumption cannot be confirmed and may have influenced the estimated proportions of patients on combination therapies. Moreover, the intended use and rationale of medication regimens (eg, SABA monotherapy) were not available from administrative data.

Crucially, this study did not examine causal relationships between treatment intensification, exacerbations and HCRU; it identified associations. Further research may help to understand whether treatment adherence rates differ between controlled and uncontrolled patients, and the factors driving changes in treatment regimens. Given the higher proportion of comorbidities in the uncontrolled cohort, further research is warranted exploring the relationship between comorbidities, physician prescribing behavior and responses to treatment.

In conclusion, many patients were identified as having SA in Alberta between 2011 and 2020. Although SA was controlled in 96% of patients when identified as severe, a meaningful proportion still experienced exacerbations over follow-up. These episodes may have contributed to SA burden from a direct medical-economic perspective, as we observed, and to a meaningful quality-of-life and indirect costs. Although relatively few patients appeared to have uncontrolled SA, our study identified gaps in treatment and disease management in this population. Exacerbation rates were nearly 6 times higher for patients uncontrolled versus controlled at index, contributing to higher HCRU and costs. This burden suggests a need for better recognition of asthma severity, earlier identification of patients having difficulty controlling their symptoms, and a need to consider improvements in current management strategies.

Author contributions

All authors contributed substantially to the design of the study and provided their approval of the final version to be published. E.G. was involved in the acquisition and analysis of data. P.M. was involved in the analysis, interpretation and writing of the draft manuscript. L.G. and S.M. were involved in the acquisition, analysis, interpretation, and writing of the initial draft of the manuscript. J.M.R., A.R., C.S. and A.F. contributed to the interpretation of the study and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (160.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Heather Neilson, Kate Brown, Tram Pham and Adaeze Nwigwe who contributed to the writing of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

This study is based in part by data provided by Alberta Health and Alberta Health Services. The interpretation and conclusions are those of the researchers and do not represent the views of the Government of Alberta. Neither the Government of Alberta nor Alberta Health express any opinion in relation to this study.

L. Geyer, P. Manivong, E. Graves, and S. McMullen are employed by Medlior Health Outcomes Research Ltd., which received funding for the study from AstraZeneca Canada (AZ). A. Randhawa, C. Shephard and A. Foster are employed by AstraZeneca Canada who funded this study. J.M. Ramsahai has received consulting fees and honoraria, and participated in clinical trials with AZ, Novartis, Sanofi and GSK.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Report From the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System: Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) in Canada, 2018. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2018.

- Center for Disease Control. Most recent national asthma data. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm. Accessed October 10, 2022.

- Asher MI, García-Marcos L, Pearce NE, Strachan DP. Trends in worldwide asthma prevalence. Eur Resp J. 2020;56(6):2002094.

- Chen S, Golam S, Myers J, Bly C, Smolen H, Xu X. Systematic literature review of the clinical, humanistic, and economic burden associated with asthma uncontrolled by GINA steps 4 or 5 treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(12):2075–2088. doi:10.1080/03007995.2018.1505352.

- Asthma Canada. Asthma facts and statistics. Accessed April 5, 2021. https://asthma.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Asthma-101.pdf.

- Asthma Canada. Understanding asthma. Accessed April 5, 2021. https://asthma.ca/get-help/understanding-asthma/.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2022. www.ginasthma.org.

- FitzGerald JM, Lemiere C, Lougheed MD, et al. Recognition and management of severe asthma: A canadian thoracic society position statement. Can J Resp Crit Care Sleep Med. 2017;1(4):199–221. doi:10.1080/24745332.2017.1395250.

- Ismaila A, Blais L, Dang-Tan T, et al. Direct and indirect costs associated with moderate and severe asthma in Quebec, Canada. Can J Resp Crit Care Sleep Med. 2019;3(3):134–142. doi:10.1080/24745332.2018.1544839.

- Bahadori K, Doyle-Waters MM, Marra C, et al. Economic burden of asthma: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9(1):1–16. doi:10.1186/1471-2466-9-24.

- Côté A, Godbout K, Boulet L-P. The management of severe asthma in 2020. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;179:114112. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114112.

- Hiles SA, Harvey ES, McDonald VM, et al. Working while unwell: workplace impairment in people with severe asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2018;48(6):650–662. doi:10.1111/cea.13153.

- Yang CL, Hicks EA, Mitchell P, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society Guideline – a focused update on the management of very mild and mild asthma. Can J Resp Crit Care Sleep Med. 2021;5:205–245. 2021: doi:10.1080/24745332.2021.1877043.

- Sadatsafavi M, Lynd L, Marra C, et al. Direct health care costs associated with asthma in british columbia. Can Respir J. 2010;17(2):74–80. doi:10.1155/2010/361071.

- Czira A, Turner M, Martin A, et al. A systematic literature review of burden of illness in adults with uncontrolled moderate/severe asthma. Respir Med. 2022;191:106670. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106670.

- Government of Alberta: Alberta Health and Performance Reporting Branch. Interactive Health Data Application: Asthma, 2022.

- Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–682. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq433.

- Statistics Canada. Consumer Price Index (CPI) statistics, measures of core inflation, and other related statistics - Bank of Canada definitions. 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1810000401. Accessed October 19, 2022.

- Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573–577. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010.

- Suruki RY, Daugherty JB, Boudiaf N, Albers FC. The frequency of asthma exacerbations and healthcare utilization in patients with asthma from the UK and USA. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12890-017-0409-3.

- Hassan M, Davies SE, Trethewey SP, Mansur AH. Prevalence and predictors of adherence to controller therapy in adult patients with severe/difficult-to-treat asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Asthma. 2020;57(12):1379–1388. doi:10.1080/02770903.2019.1645169.

- Lougheed MD, Lemiere C, Ducharme FM, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society 2012 guideline update: Diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers, children and adults. Can Resp J. 2012;19(2):127–164.

- Bleecker ER, Gandhi H, Gilbert I, Murphy KR, Chupp GL. Mapping geographic variability of severe uncontrolled asthma in the united states: management implications. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;128(1):78–88. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2021.09.025.

- Gibbons DC, Aggarwal B, Fairburn-Beech J, et al. Treatment patterns among non-active users of maintenance asthma medication in the united kingdom: A retrospective cohort study in the clinical practice research datalink. J Asthma. 2021;58(6):793–804. doi:10.1080/02770903.2020.1728767.

- Bengtson LG, Yu Y, Wang W, et al. Inhaled corticosteroid-containing treatment escalation and outcomes for patients with asthma in a us health care organization. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(11):1149–1159.