?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper depicts the relationship between the EU and pensions by demonstrating the EU’s indirect pressure on pensions – spill-over from the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) – reflected through economic and fiscal policy coordination mechanism. Concretely, the paper examines how compliance with the fiscal and economic policy guidelines deriving from the European Semester shape prospects for pension adequacy in the euro area countries. Pension adequacy is understood as the ratio of available income in retirement relative to available income during employment. The results point to three empirically relevant economic-fiscal policy models/configurations under which adequate pensions are observed. The models are not universally based on compliance with the policy guidelines under the Semester and they differ in terms of the type of policy which is potentially conducive for adequate pensions. Diversity of the models thus implies that compliance with the guidelines works for some euro area countries whilst for others it does not. Consequently, the shaping prospects or the safeguarding capacity of the Semester’s policy guidelines in terms of adequate pensions are modest. The main method used in the paper is fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA).

Introduction

Economic integration, the intra-EU growing interdependencies and the enhanced role of the EU institutions in policy design and surveillance inevitably created a conundrum with regard to policy domains deemed ‘bastions' of national sovereignty. One such field is pension policy including its outcomes. The conundrum has become ever more salient in the contemporary, post-crisis, EU economic governance embodied in the European Semester. The Semester operates as an annual economic (and fiscal) policy coordination cycle. Existing evidence on the relationship between the EU including the European Semester has not been conclusive. Scholars predominantly aim to demonstrate whether a pension reform in a member state occurred because of the EU’s interventions. Nevertheless, this article approaches the above relationship differently. It exclusively focuses on a primary outcome of a pension system namely pension adequacy (see Holzmann Citation1998). To this end, it takes adequacy as given and primarily understands it as a function of economic and fiscal policies. Conceptually, for the purpose of the article, I understand adequacy through the notion of income replacement. Hence, I operationalize adequacy as the ratio of available income in retirement relative to available income during employment.

It is, however, important to emphasize that this article does not attempt to claim and/or unravel a causal relationship between the Semester and pension adequacy. Such an effort would be counter-productive and counter-intuitive as, causally, pension adequacy is the result of institutional developments of national pension (and socio-economic) systems and reforms therein. Instead, the main objective is to explore inductively under which economic-fiscal policy models/configurations (bounded by the Semester’s policy guidelines) adequate pensions are observed.

Hence, the main research question driving this article is: to what extent do the economic and fiscal policy guidelines under the European Semester shape the prospects for adequate pensions? Put differently, the analysis assesses the Semester’s safeguarding capacity for pension adequacy in terms of fiscal and economic fundamentals. I mirror the policy guidelines/strategy under the Semester through member states’ compliance with the Semester’s indicators (under the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP)) and their respective thresholds; as in the case of non-compliance, member states can (theoretically) be subject to sanctions. Such scholarly effort is sensible due to adequacy’s relevance within the EU economic governance. To start with, adequacy (as is the operation of a pension system) is interdependent with the socio-economic system including economic and fiscal policies by default (see Wehlau and Sommer Citation2004). Additionally, due to the unfavourable demographic trends, it is a common, long-term policy challenge for most of the EU member states (European Commission Citation2010; von Nordheim Citation2016). Moreover, it has become integrated into the Semester’s operations and outputs (Guardiancich and Natali Citation2017; Guidi and Guardiancich Citation2018). Therefore, in terms of prospects, adequate pensions are likely to be indirectly affected through economic and fiscal policy guidelines produced within the Semester cycle. Ergo, ‘indirect' effects refer to the forces of EU economic and fiscal policy coordination and are the focus of the analysis.Footnote1

I approach the research question from a configurational angle and thus use fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) as the main method. FsQCA detects combinations of factors that are conducive/sufficient for an outcome. Considering (non) compliance with the policy guidelines/thresholds produced by the Semester, the results yield three empirically relevant policy configurations/models under which adequate pensions occur. Interestingly, the models are not universally based on compliance with the policy guidelines. They suggest different types of economic-fiscal policies that are empirically conducive for adequate pensions. Diversity of the models thus implies that compliance with the guidelines works for some euro area countries whilst for some it does not (or is even detrimental for pension adequacy). Consequently, the safeguarding capacity of the Semester’s guidelines in terms of adequate pensions is modest. Interestingly, the models are not dependent on political identity of national governments – the main actor in the implementation of the recommended policy guidelines.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. The following section provides a literature review on the relationship between the EU and pensions, which helps structure the adopted analytical framework. The article then depicts the method and conceptualizes input and output factors for the analysis. The article then demonstrates the main findings of the analysis, focusing on alternative economic and fiscal policy configurations that are conducive for pension adequacy.

Understanding the contemporary role of the EU in pensions

The relationship between the EU and pension policy is complex and rather unsettled. A strand of Europeanization literature demonstrates a crucial role of the EU in shaping national welfare state systems by emphasizing eroded national sovereignty and detecting prominent channels of European influence (Leibfried Citation2010; Hemerijck Citation2006). Nonetheless, others hesitate to acknowledge meaningful impact of the EU (see Barcevicius, Weishaupt, and Zeitlin Citation2014). In the context of current EU economic governance, evidence about the relationship is not conclusive. On the one hand, the EU’s involvement in pension policy has increased as a consequence of the sovereign debt crisis through interactions with domestic actors and indirect pressures (Porte and Heins Citation2015; Sacchi Citation2015). Building on this, Windwehr (Citation2017) shows that the EU’s impact is visible only in member states hit the most by the crisis. Sacchi (Citation2015), for instance, demonstrates the implicit conditionality that explains the EU’s intervention in pension reforms in Italy. On the other hand, however, Hassenteufel and Palier (Citation2015) argue that the EU was not the main driver of pension reforms in France although the experience of the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) under the SGP has shaped the discourse around the reforms.

The inconclusive evidence suggests that the Semester’s link to pension reforms is case and context-sensitive, and predominantly derives from indirect pressures. The indirect pressures are spill-over from the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) reflected through economic and fiscal policy coordination mechanisms (see Leibfried Citation2010; Natali and Stamati Citation2013). The overarching focus of the above-mentioned studies was whether the pension reforms in the member states occurred due to the EU’s interventions. As indicated in the introduction, this article takes a fundamentally different approach to the relationship between the EU (the Semester) and pensions. Instead of unravelling whether a government enacted a reform under and/or because of the EU’s involvement, it explores whether fiscal and economic policy guidelines embedded in the Semester are conducive for shaping favourable pension policy outcome – pension adequacy. Economic and fiscal policies are particularly relevant for pension system outcomes considering that euro area retirees predominantly take-up their benefits from public pension schemes (see Bovenberg and van Ewijk Citation2011). More importantly, most public schemes are pay-as-you-go (PAYG) meaning that they are not pre-funded but current contributions (with subsidies from the government budget) are used to pay current benefits (European Parliament Citation2011, Citation2015; see Poteraj Citation2008 for an extensive overview).

The outlined focus is relevant due to developments within the socio-economic axis of the Semester, which focuses on the relationship and interaction between economic and social policy goals (see Verdun and Zeitlin Citation2018). First, the Semester has been ‘socialised'. This means that economic policy coordination increasingly accounts for social policy issues (e.g. labour market, pensions, poverty) by including them into the process from target setting to policy recommendations (Costamagna Citation2013; Degryse, Jepsen, and Pochet Citation2013; Urquijo Citation2017; Copeland and Daly Citation2018; Guidi and Guardiancich Citation2018; Zeitlin and Vanhercke Citation2018). Second, however, social concerns have been subjugated to economic (and fiscal) priorities (Bekker and Klosse Citation2013; Bekker Citation2015; Zeitlin and Vanhercke Citation2018). Thus, ‘[…] national budgetary discipline and the correction of macroeconomic imbalances have not only become the guiding principles […] but have been made the principles on which all other policy objectives are dependent' (Copeland and Daly Citation2015, 150). Third, EU economic governance has taken a hybrid form. Hybridity allows the EU to intervene in policy fields (e.g. pensions) in which it does not have exclusive legal competencies (Palinkas and Bekker Citation2012; see Armstrong Citation2012). As a result, governance under the Semester transposed features of hard law into soft law policy coordination (Bekker and Klosse Citation2013; Copeland and Daly Citation2015). Considering these developments, the effects of the EU policy guidelines on social outcomes are visible ‘at the end of the chain' (see below) and are therefore indirect as indicated in the introduction.Footnote2

Analytical framework

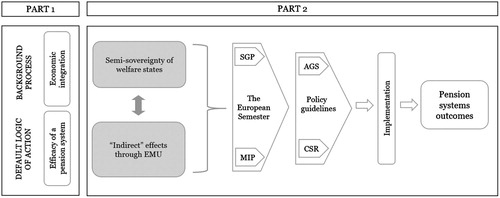

In the above-outlined governance context, I frame the changing role of EU policy coordination in pension policy within what I label as an evolutionary chain (see ). The chain consists of two interlinked parts. The first part includes a default logic of action and a background process. The default logic entails the general operation of a pension system implying that an individual must be an active part of the socio-economic system in order to be able to claim (adequate) pension benefits.Footnote3 To this end, the European Commission (Citation2010, 6) states that ‘future pensions will increasingly rest on good economic performance [and] ability of labour markets to provide opportunities for longer and less interrupted careers.' This statement draws on the relationship between the socio-economic system and pension adequacy, which are interdependent by default (Wehlau and Sommer Citation2004). Therefore, adequate pensions presumably derive from sound economic, fiscal and financial fundamentals (Zaidi Citation2010). Particularly, macroeconomic aggregates such as unemployment, labour mobility and costs, competitiveness and public/fiscal spending have an impact on pension adequacy, which is, however, visible only ‘at the end of the chain'. This implies that the relationship is not directly causal, especially in the EU governance context (see e.g. Bonoli Citation2003; Wehlau and Sommer Citation2004; Barr and Diamond Citation2006; Grech Citation2013). Fiscal and economic fundamentals are coordinated at the EU level. This is the result of European economic integration and increased interdependencies between the member states – the background process within the analytical framework. The two elements continuously trigger the EU’s involvement in pensions.

Figure 1. Evolutional chain-relationship between the EU economic governance and pension system outcomes.

Consequently, the second part of the framework consists of enabling factors (shaded rectangles in ) and specific channels (pentagons in ). They fill up the space created by the economic integration and operational logic of a pension system. Initially, the EU’s increased role in pensions results from gradually eroding national sovereignty (legal authority) and autonomy (policy capacity) in welfare policy (Hemerijck Citation2006; Leibfried and Pierson Citation1995; see Ferrera Citation2005). Put differently, welfare and social affairs, once bastions of national sovereignty have essentially become semi-sovereign with accompanying legal and policy implications (see Leibfried and Pierson Citation1995; Scharpf Citation2002; Taylor-Gooby Citation2005). Concerning the latter, the member states have lost full control over their welfare policies. Hence, pension matters cannot be understood entirely without acknowledging the EU’s role therein (Leibfried and Pierson Citation1995).

Moreover, the so-called indirect pressures – the result of spill-over from fiscal and economic policy coordination in the EMU – further enable EU interventions in pensions.Footnote4 Although pensions are officially coordinated through the open method of coordination (OMC), the spill-over has become more salient in the contemporary governance context. Simultaneously, the OMC has failed to deliver substantial policy coordination outcomes in terms of policy transfers and change. Thus, ‘open methods of coordination were gradually emptied of their substance’ (Degryse, Jepsen, and Pochet Citation2013, 37; see Jacquot Citation2008; Guardiancich and Natali Citation2017). Consequently, pensions have been indirectly subsumed under economic and fiscal policy coordination, which have been strengthened with the introduction of the Semester in the aftermath of the sovereign debt crisis (Armstrong Citation2012). The crisis served as a catalyst in enhancing the EU’s role in pensions considering that member states’ individual ability to tackle pension policy challenges has reduced thereafter (Parent Citation2011).

The Semester embodies specific channels of indirect pressures through its sanction-bearing mechanisms – the SGP and the MIP (Natali and Stamati Citation2013; Bekker Citation2015). Within the Semester, pensions constitute a significant element of priorities defined in the Annual Growth Survey (AGS) (Guardiancich and Natali Citation2017). Additionally, pensions are strongly represented in policy-oriented output of the Semester namely Country-Specific Recommendations (CSR) (European Commission Citation2012; European Parliament Citation2015; Guardiancich and Natali Citation2017; Copeland and Daly Citation2018; Kvist Citation2013). Overall, the EU’s indirect pressures represent the ‘front-runner’ in shaping the prospects for pension systems outcomes including adequacy.

The Semester’s mechanisms – the SGP and MIP – generate EU’s economic and fiscal policy priorities and recommendations for the member states. Under a theoretical threat of sanctions, member states are expected to comply with the recommendations. By looking at CSRs over the past seven years, it is evident that the EU prioritizes fiscal consolidation, improving economic growth and competitiveness whilst maintaining stability in the euro area. Implementation of policies to achieve these objectives, inevitably, although indirectly, affects pension adequacy ‘at the end of the chain'. This is due to the above-mentioned interdependence. For instance, in the aftermath of the sovereign debt crisis, member states were ‘compelled' to reduce pension adequacy (i.e. direct cuts of pension benefits from public schemes, tighter conditions for full retirement, recommending abolishment of early retirement) in order to pursue fiscal consolidation (see Guardiancich and Natali Citation2017; Parker and Pye Citation2018). Nevertheless, one should note that the EU also recommends reforms in the labour market, life-long learning, and old-age employment to name but a few. These measures seemingly enhance pension adequacy. The assumed implementation of recommended economic and fiscal policies is the penultimate link in the chain. It exposes the indirect impact of economic and fiscal fundamentals on adequacy. Hence, the actual (indirect) effects are only observable at the end of the evolutionary chain.

In sum, the adopted analytical framework unravels a complex relationship between economic and fiscal policies and pension adequacy considering the Semester’s coordination cycle. The framework justifies and ensures the validity of the research question and demonstrates the analytical and policy-relevant contribution of this study. Moreover, from a policy perspective, it meaningfully integrates the explanans and the explanandum of the empirical analysis, discussed in the following section.

Methodology and conceptualizations

To answer the research question, I employ a case-based fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA).Footnote5 FsQCA identifies necessary and sufficient conditions for an outcome of interest.Footnote6 The method yields combinations of factors/conditions conducive for an outcome (see Ragin Citation2008). FsQCA is ofhe configurational character, which is its main advantage for the purpose of this article. On the one hand, it enables the ‘correct' reading of the Semester’s indicators, by allowing for cross country comparison over time, suggesting possible implications of economic policy and interaction among the indicators (European Commission Citation2010, Citation2012; Bouwen and Fischer Citation2012; Šikulová Citation2015). On the other hand, fsQCA accounts for the hybrid character of the EU economic governance within which ‘[it] is not possible to predict which policy item will be explored via which coordination mechanism' (Bekker Citation2015, 13). Finally, pension adequacy as an outcome displays traits of equifinality. This means that it can be produced by alternative combinations which, in this case, constitute fiscal and economic policy models/configurations. Hence, the configurational approach aligns with the main objective of this article stated in the introduction.

FsQCA translates variables into conditions including an outcome through the process of calibration. When calibrating, scholars assign fuzzy scores (any value from 0 to 1) to raw data values across all cases included in the analysis. Assigning fuzzy scores is based on the criteria developed by using existing evidence and knowledge on a case and condition in question. It follows a certain logic that aligns with the research question and objectives. To this end, the main task of calibration is to define what is called qualitative anchors for each condition (and the outcome). The anchors determine qualitative difference between cases (see Ragin Citation2008).Footnote7 In fsQCA, conditions (and the outcome) are considered in their presence or absence.

For the purpose of this study, I calibrate four potentially relevant conditions for the outcome. I develop the conditions through the indicators operating under the Semester’s mechanisms – the SGP and the MIP. The SGP is entirely covered by the analysis while the selected MIP indicators adequately represent policy fields covered by it (see ). The four conditions (explanans) are compliance with the unemployment rate threshold (UR), compliance with the current account balance thresholds (CAB), strong compliance with nominal unit labour cost (ULC), and compliance with fiscal targets under the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP).Footnote8 I expect conditions to have an effect in their presence rather than absence considering that the main objective of the article. Overall, the four conditions display theoretical relevance to pension adequacy and are well-integrated into the above-depicted analytical framework – the evolutionary chain (see ). Therefore, the selected conditions (presumably) affect pension adequacy ‘at the end of the chain’.

Table 1. Operationalization of fsQCA conditions.

Table 2. Theoretical and expected connection between the conditions and the outcome.

The main criterion for assigning fuzzy scores is compliance with the indicators’ ex ante thresholds defined at the EU level. The better the compliance, the higher the fuzzy set score. In defining the three qualitative anchors for conditions (and the outcome), I build upon external criteria. These include the aims of the EU policy coordination, general rationales of economic policy and observations in data (see Appendix 1). I use external criteria due to the absence of direct (qualitative and/or quantitative) guidelines which would serve as a reference in assigning fuzzy scores.

The outcome (explanandum) is above median pension adequacy (PADEQ). Pension adequacy lacks a universally accepted definition (Grech Citation2015). In defining adequacy for the purpose of this article I draw on Walker's (Citation2005) arbitrary determination approach. The approach understands adequacy in terms of pension benefits levels, average incomes, minimum wages and their respective measurements. Additionally, it is favoured by international institutional structures including the EU. The main advantage of the approach are consistent and comparable data as well as consistency with the EU’s view on adequacy. To illustrate, the European Parliament (Citation2014) defines an adequate pension system as a guarantor against poverty and a mechanism that sufficiently replaces working life wage/income. Hence, I define adequacy as a given outcome of a (public) pension system estimating available income in retirement relative to available income during employment.

I operationalize the outcome with the aggregate replacement ratio (ARR) as a measure of pension adequacy. ARR is the gross median pension income of the 65–74 age group relative to gross median individual earnings in the employment of population aged 50–59, excluding other social benefits (Database-Eurostat Citationn.d.). It should be noted that the replacement rate ratio and its variants as measurements of pension adequacy have their limitations and drawbacks. They have been scrutinized for being overly simplistic and arbitrary, not having a universal definition, and not accounting for time horizon (Van Derhei Citation2006; Borella and Fornero Citation2009; see Bajtelsmit, Rappaport, and Foster Citation2013). However, replacement rate ratios are still the most widely used measurements of pension adequacy, especially in the EU context. Alternative measures such as pension wealth (see Grech Citation2015) diminish some of its drawbacks. Nevertheless, as pension wealth is based on income survey data, its ability to assess the relationship between policy changes and policy outcome is limited. It better reflects the design of a pension system over a longer time period which is not the focus of this analysis. Therefore, and due to lack of a universally accepted measurement of pension adequacy, I select ARR as an estimation of pension adequacy. In determining the three qualitative anchors for PADEQ, I combine distribution parameters such as median and percentiles of ARR with existing empirical estimations of both minimum and desired levels of replacement ratios (see Appendix 1). Appendix 2 summarizes all fuzzy scores.

The sample consists of 43 cases corresponding to incumbent governments (aligned with the election cycles) in euro area countries within the period of seven years (2011–2017). For instance, considering that Spain had three governments in this time period, each government constitutes an individual case even though the prime minister or the ruling party may not have changed. Nonetheless, in some countries the prime minister changed with the elections in the mentioned time period. I consider this a new case only when the new prime minister comes from a different political party.Footnote9

Results and discussion

FsQCA consists of necessity and sufficiency analyses in subsequent order (Schneider and Wagemann Citation2012). Nonetheless, as necessity analysis did not yield any necessary conditions for the outcome, I solely interpret sufficiency relations. After calibration, sufficiency analysis entails two stages: truth table algorithm and logical minimization. Truth table algorithm lists all logically possible combinations of conditions (see Appendix 3). Subsequently, fsQCA analysis uses Boolean algebra to minimize the truth table and yields combinations/paths of conditions that are sufficient for the outcome.

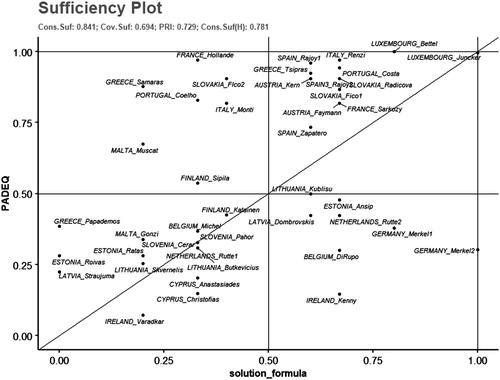

The strength of the results is assessed through consistency and coverage. Consistency indicates the degree to which a sufficient path and/or the solution formula deviate from perfect subset relation (consistency = 1).Footnote10 Coverage indicates how much of the outcome is covered/explained by a sufficient path/solution formula (Schneider and Wagemann Citation2012). summarizes consistency and coverage scores. The analysis yields four sufficient paths for the outcome which, connected with logical or (+), make the most parsimonious solution formulaFootnote11:

Table 3. Results of fsQCA analysis.

Consistency for the solution formula is 0.841 meaning that there is a (moderately strong) subset relation between the conditions and the outcome. Relatively high consistency makes the formula theoretically informative. Moreover, relatively high coverage (0.694) ensures empirical relevance of the formula. In other words, out of 21 cases that have fuzzy score in the outcome PADEQ higher than 0.5, 69.4 per cent is explained by the solution formula. Due to the word limit I discuss three out of four paths based on the number of covered cases. I interpret them in terms of economic and fiscal policy models under which above-median pension adequacy is empirically observed.

Model A – Fiscal obedience with strong competitiveness

Model A suggests that the combination of compliance with the fiscal targets (at least one) defined by the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and non-compliance with the current account balance threshold(s) (∼CAB) is sufficient for the outcome (PADEQ). Non-compliance with the current account balance implies declining competitiveness. However, declining competitiveness as a part of the sufficient path for adequate pensions is counter-intuitive as, theoretically, adequacy should improve in a competitive economy. A closer look at the cases covered by the model explains the confusion. The model covers five cases of which are two German (Merkel1 and Merkel2) and two Luxembourgish (Junker and Bettel) governments. The countries in question indeed breach the current account balance threshold but, on the surplus (6 per cent), not deficit (−4 per cent) side. This implies that Germany and Luxembourg as individual economies are highlycompetitive. Therefore, within model A competitiveness is conducive for pension adequacy. Nevertheless, from the euro-area perspective, high current account surplus in one country might imply current account deficit in another – that is why the surplus threshold was introduced in the first place.

Cases covered by model A are fiscally obedient in terms of the Stability and Growth Pact regulations and provisions. This points to consolidated government budgets and/or decreasing government debt levels in these countries. Consolidated budgets and restrictive fiscal policy should, in the long-run, be beneficial for pension adequacy as they positively affect pension sustainability (financing of pension systems that largely relies on public funding including general taxation) which is a pre-condition for adequate pensions (von Nordheim Citation2016). Nevertheless, sustainability and adequacy are often in a non-reciprocal, trade-off relationship. Expectedly, whilst sustainability increases, adequacy decreases and vice versa (see e.g. Mercer Citation2011). The trade-off induces complexity in the relationship between fiscal policy and pension systems. This becomes more prominent in the SGP context, as governments are restricted in manoeuvring fiscal policy. In theory, complying with the SGP thresholds substantially diminishes likelihood for member states to become subject to sanctions.

In sum, model A demonstrates that compliance with the most disputed part of EU policy coordination under the Semester – the SGP (see e.g. Heipertz and Verdun Citation2004; Begg and Schelkle Citation2004), in combination with a competitive economy enhance prospects for pension adequacy. From the perspective of an individual economy (that disregards breaching current account balance threshold on the surplus side), model A serves as an example of compatibility between economic/fiscal policy strategy advocated by the EU (including its overarching aims) and pension adequacy. Therefore, the EU policy guidelines safeguard pension adequacy ‘at the end of the chain'. However, the safeguarding argument is somewhat weakened due to the occurrence of the so-called deviant cases-consistency in kind (Germany_Merkel1, Germany_Merkel2) covered by model A. In the fsQCA research context, these cases are of substantial relevance. Ergo, I discuss them in a separate subsection.

Model B – Competitiveness measures to diminish cyclical unemployment

Model B consists of non-compliance with the unemployment threshold (∼UR) in combination with compliance with the current account balance threshold (CAB) and strong compliance with nominal unit labour cost (ULC). It is empirically the most insightful as it covers 11 cases.Footnote12 The cases predominantly include countries/governments from the so-called PIIGS group whose economies were heavily damaged during the European sovereign debt crisis. In addition, the model covers the Baltic trio. The cases suffer from similar economic problems with cyclical unemployment being the salient one.

Nonetheless, despite high unemployment (in terms of breaching the Semester’s threshold), adequate pensions are still observed in this model. This is partially due to the fact that pension systems in some countries covered by the model are traditionally generous, non-funded and financed through public budget (e.g. Italy and Spain). Another possible explanation entails high fuzzy scores in CAB and ULC conditions implying that covered cases perform relatively well along the competitiveness dimension. As stated throughout the article, theoretically, increased competitiveness that presumably reduces unemployment would have a positive effect on pension adequacy ‘at the end of the chain'.

Empirical evidence from model B only partially supports the EU’s economic policy strategy under the Semester in terms of prospects and safeguarding pension adequacy. This is due to the inclusion of non-compliance with the unemployment threshold in the model. As with model A, the safeguarding argument is additionally weakened as model B covers five deviant cases.

Model C – Fiscal disobedience with somewhat rigid labour markets

The third policy model implies that the combination of non-compliance with fiscal targets under the Stability and Growth Pact (∼SGP); compliance with current account balance threshold(s) (CAB); and weak compliance with nominal unit labour cost threshold (∼ULC) is sufficient for the outcome (PADEQ). Put differently, this configuration implies that pension adequacy is also observed under conditions of expansionary fiscal policy and not fully utilized competitiveness potentials. Five cases covered by this model (Austria_Faymann, Austria_Kern, Belgium_DiRupo, France_Sarkozy) persistently demonstrate budget deficits with slowly (or non-) decreasing government debt. Although none of the countries was subject to sanctions, theoretically, they are fiscally disobedient under the SGP.

Along the competitiveness dimension, weak compliance with nominal unit labour cost threshold suggests that labour markets in countries covered by model C are somehow rigid. CSRs regarding labour market issued by the Commission within the Semester support this. Particularly, in the period from 2011 to 2017, the Commission continuously recommended measures such as removing restrictions and barriers for companies and service providers, combating labour market segmentation, improving labour productivity and (consequently) competitiveness, fostering competition and efficiency in service and public sectors, reforming the wage-bargaining system, and strengthening the effectiveness of labour market policy based on flexibilization.Footnote13 Therefore, cases covered by this model only partially utilize competitiveness in terms of being sufficient for the outcome (compliance with the current account balance threshold).

Model C shows that adequate pensions can be observed under the conditions of (dominantly) non-compliance with the EU’s ex-ante defined thresholds. Partial competitiveness indicated by weak compliance with nominal unit labour cost (∼ULC) might presumably be compensated with relatively favourable current account balance (CAB). The occurrence of the outcome under the non-compliance with fiscal targets under the SGP (∼SGP) posits a more worrisome observation. First, it contradicts the model A in which pension adequacy occurs under the compliance with the SGP’s fiscal target(s). Second, it exposes the above-mentioned trade-off between pension adequacy and sustainability as within model C adequate pensions occur in countries with non-consolidated budgets and tendencies towards increased fiscal spending. Third, considering that pension-related issues are intimately linked to political legitimacy of an incumbent government, the incentive to comply with restrictive fiscal targets weakens (see Myles and Pierson Citation2001).

The structure of model C points to the everlasting debate of effectiveness of fiscal policy coordination under the SGP and its underlying ‘one-size-fits-all' approach. Overall, in regard to the prospects/safeguarding adequacy ‘at the end of the chain’, empirical evidence from model C exhibits the limits of the EU’s fiscal and economic policy strategy. Model C as well covers a contradictory case (Belgium_DiRupo) implications of which further disclose modest capacity of the EU’s economic policy strategy for safeguarding pension adequacy.

Implications of deviant cases

Deviant cases consistency in kind (contradictory cases) have a fuzzy score in the solution formula higher than 0.5 while their score in the outcome is lower than 0.5 (Schneider and Wagemann Citation2012; Schneider and Rohlfing Citation2013). The three models cover a total of sevencontradictory cases (lower right quadrant in ).Footnote14 From the safeguarding perspective, contradictory cases covered by models A and B are worrisome as these models are predominantly based on compliance with the Semester’s thresholds. In other words, these cases comply with the Semester’s thresholds, yet (still) have low (below median) pension adequacy.

To that end, in terms of policy prospects, contradictory cases expose potentially detrimental effects of EU economic and fiscal policy priorities on pension adequacy ‘at the end of the chain'. A relevant example of this are the Baltic countries/governments – contradictory cases covered by model B. Since the establishment of the European Semester, due to the austerity measures favoured by the EU, Baltic countries have substantially consolidated their public finances. During the period captured by the analysis, the three countries managed to maintain debt levels at one of the lowest rates in the EU. Additionally, concerning budget deficits, Estonia ran surpluses whilst Latvia and Lithuania significantly reduced them and got close to a balanced budget. Consequently, the Baltic countries have high fuzzy membership in the solution formula, yet pension adequacy as operationalized in this analysis remains low. Hence, in terms of adequate pensions, the added value of fiscal consolidation, and recognized effort to comply with other EU’s targets, has been modest (see Woolfson and Sommers Citation2016). Particularly, ‘austerity measures adopted by the Baltic governments have created societies that are, in terms of foreseeable prospects, neither socially sustainable nor capable of enduring economic recovery' (Woolfson and Sommers Citation2016, 79).

Surprisingly, a similar observation holds for Germany. Two German governments (Merkel1, Merkel2) are deviant cases in model A which, from a single country (not euro area) perspective, also relies on the EU’s policy guidelines. The two cases have a high fuzzy set score in the solution formula (Merkel2 even the maximum score), whilst in the outcome set their fuzzy set scores are below 0.5. Nonetheless, Luxembourg_Juncker case (a typical case – upper right quadrant above the diagonal in ) that is also covered by model A, has maximum fuzzy set membership in both the solution formula and the outcome. In terms of achieving pension adequacy, this points to discrepancies in the EU’s ‘one-size-fits-all' economic governance even within a specific policy configurationthat istheoretically conducive for the desired outcome. Put differently, both compliance and non-compliance with the EU’s thresholds (potentially) produce substantially different effects in different countries. This aligns with the suggested solutions for improving the efficacy of the Semester and EU policy coordination in general. The solutions include institutional (i.e. establishment of a European Fiscal Board and a National Competitiveness board, independent ‘structural council') and operational (i.e. simplification, decentralization, symmetric relationship between the mechanism, division of euro-area from country-specific concerns) changes (see Gros and Alcidi Citation2015; Benassy-Quere Citation2015; Darvas and Leandro Citation2015; Gren, Jannsen, and Kooths Citation2015). The EU has partially recognized the suggestions by, for example, simplifying CSRs.

A glimpse at governments and robustness of the solution formula

In addition to assigning fuzzy scores to cases, I categorize them in three groups (right, left, or grand) based on the political identity of the governing coalition in a country. The right category includes coalitions of right-wing, Christian-democratic, liberal-conservative and/or conservative nationalistic parties. The left includes coalitions consisting of left-wing, social-democratic, social-liberal, and/or green parties. Finally, I categorize a case as grand if the governing coalition in question consists of parties from both the right and left camps. The underlying logic behind clustering cases is to test the models against the type of governing coalition as governments are the main actors in adopting and implementing the EU’s policy guidelines and recommendations.

The results are shown between consistency (BECONS) and BECONS distance scores for coalition categories respective of the individual model (see ). BECONS measures cross-sectional consistency for each coalition category while BECONS distance effectively indicates how precise is consistency for the whole, non-clustered data sample (García-Castro and Ariño Citation2016). BECONS as well ranges from 0 to 1. Persistently high BECONS scores for each coalition category across all models and close to zero BECONS distances imply that the effect of an individual coalition category is not significant. In other words, compliance (or non-compliance) with the EU’s policy strategy under the Semester in terms of pension adequacy does not depend on the type of governing coalition. This is an interesting observation considering rising Euroscepticism and existence of ‘non-cooperative' governments in the EU (yet outside the euro area). More importantly, high BECONS scores indicate the robustness of the solution formula.

Table 4. BECONS and BECONS distance scores.

To test the robustness of the solution formula further, I conduct the alternative analysis using different operationalization of the outcome PADEQ. Instead of aggregate replacement ratio (ARR), I use simple pension adequacy indicator (SPAI) developed by Chybalski and Marcinkiewicz (Citation2016). SPAI is the ratio of relative median income for the population aged (65+) and at-risk-poverty rate of elderly people (65+). The indicator has no unit assigned and can (theoretically) range between zero and infinity. Nonetheless, higher values of the indicator mean higher pension adequacy and vice versa. SPAI is compatible with the arbitrary determination approach to pension adequacy adopted in this article. Moreover, it is suitable for a cross-country comparison. Thus, it is a sound measure for a robustness test although, admittedly, it may better reflect pension system design over a longer time period than (immediate) fiscal-economic policy effects. In calibration of the alternative outcome (SPAI_FS), I use the same criteria as in the original analysis concerning qualitative anchors (median and percentiles) and determining the consistency threshold.Footnote15

The results from the alternative analysis re-confirm the robustness of the original solution formula. Consistency score for the alternative parsimonious solution formula is relatively high (0.827), as it is the solution coverage (0.732). The alternative solution consists of four sufficient paths/models for pension adequacy (see Appendix 4). Two (SGP*∼CAB; ∼SGP*CAB*∼ULC) out of four models are identical to those generated by the original analysis. The remaining two models (∼UR*∼SGP*CAB; UR*∼CAB*ULC) reinstate the observation that adequate pensions occur under conditions of high unemployment, fiscal disobedience and partial utilization of economic competitiveness. Therefore, interestingly, the alternative analysis as well demonstrates (at best) modest capacity of the EU policy strategy and guidelines under the Semester to safeguard socially favourable policy outcomes such as pension adequacy.

Conclusion

Inspired by the enhanced role of the EU in pensions and recent developments within the socio-economic axis of the European Semester, the article examines how economic and fiscal policy guidelines under the Semester shape prospects/safeguard pension adequacy ‘at the end of the chain'. The main objective is to detect policy models bounded in the thresholds of the Semester’s mechanisms (SGP and MIP) under which adequate pensions can be observed. Fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) yields three empirically insightful models. Model A implies that fiscal obedience, i.e. respecting the SGP’s target(s), in combination with (individual) high competitiveness (large current account surplus) is sufficient for pension adequacy. From a point of view of an individual economy, model A potentially safeguards pension adequacy ‘at the end of the chain'. In model B, adequacy occurs under conditions of unemployment (non-compliance with the unemployment threshold) combined with policy efforts to boost competitiveness (compliance with competitiveness indicators – current account and nominal unit labour cost). The model is predominantly based on compliance with the Semester’s thresholds and thus points to its (partial) safeguarding capacity. In contrast, model C observes adequacy under the conditions of fiscal disobedience (non-compliance with the SGP’s targets) and partial competitiveness (compliance with the current account, yet weaker compliance with unit labour cost). The dominance of the non-compliance in model C implies a limited safeguarding potential ‘at the end of the chain'.

Empirical evidence demonstrated in this article implies the following conclusions. First, in the EU context, policy fundamentals potentially conducive for adequate pensions dominantly combine fiscal and economic measures. The fact that conditions are never sufficient on their own, yet always come in (predominantly fiscal-economic) combination, point to complexity in terms of favourable fiscal-economic policy ‘recipes' for adequate pensions.

Second, diversity of identified policy models suggests lack of unifying strategy for ensuring adequate pensions at the EU level that could be adopted by national governments. To this end, for instance, CSRs recommendations for adequacy predominantly come in pair with sustainability. Considering the possible trade-off between sustainability and adequacy, these recommendations may not work for both objectives. The Baltic countries – deviant cases – exemplify this. Instead, it may be beneficial to single-out pension adequacy as a policy challenge within the Semester’s operations as the first step in developing a strategy.

Third, to answer the research question, EU’s fiscal and economic policy guidelines have modest capacity to shape prospects/safeguard pension adequacy ‘at the end of the chain'. The capacity is further weakened due to the contradictory cases covered by policy models predominantly based on compliance with the Semester’s guidelines expressed as indicators’ ex ante defined thresholds. Put differently, despite diligent compliance, pension adequacy as operationalized in this article remains low. Nonetheless, in some cases, the EU guidelines are compatible with adequate pensions. Therefore, shaping the prospects for adequate pension is vastly case-sensitive, as suggested by empirical evidence depicted in the introduction even tough these studies pursued a (fundamentally) different aim. From a broader governance perspective, the above-presented evidence shows limitations of the ‘one-size-fit-all' approach to economic and fiscal policies within the euro area. However, recent empirical evidence points to improvements in this respect, al least concerning the content of CSRs (see D’Erman et al. Citation2019). Retrospectively, the discussion about ‘one-size-fit-all' re-opens the question of effectiveness of policy coordination under the Semester (see e.g. Benassy-Quere Citation2015).

Although empirically sound, the analysis has limitations. Most prominently, exclusive focus on economic and fiscal policies does not entirely capture pension adequacy both conceptually and empirically. To this end, adequate pensions can be explained by factors that are only marginally linked to contemporary economic and fiscal policies. The factors predominantly stem from strictly national social security/welfare traditions and inter alia include institutional structure of pension systems, power relations among societal actors (e.g. governments and trade unions), public-private sector relations, and legitimizing capacity of social policy. In addition, despite the fact that the EU’s role in pensions has increased, pensions have retained strong (and dominant) national character. As such, they are inherent part of national political agendas and often point of public disputes. To illustrate, the Croatian government attempted at reforming Croatian pension system in 2019 by largely following the EU’s rationales and recommendations. However, after a public campaign organized by the trade unions in the public sector, the reform package was almost entirely revoked. Similarly, as a reaction to protests, the French government withdrew and/or postponed some of the (relatively) recently proposed pension reforms.

In sum, by exploring adequate pensions inductively through economic and fiscal policy fundamentals enlightens, the above analysis unravels what might be called the ‘European' side of the relationship between the EU and national pensions. The other, ‘national' side consists of elements that are absent from the analysis. Ultimately, to link the two sides and put the pieces together, one might consider addressing issues such as convergence, adaptability of national pension systems to EU economic governance and portability of pensions within the EU as focal points for further research. The evidence presented in this article serves as a sound foundation for this aim as it analyses the appropriateness of the EU macroeconomic policy coordination guidelines for pension system outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Professor David Howarth and the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions that have substantially improved the quality of the article. The author also acknowledges the importance of the Luxembourg National Research Fund (FNR) funding and is grateful for its support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In contrast, ‘direct’ effects would then (hypothetically) encompass EU regulations concerning pensions and consequent reforms in a national pension system.

2 Within the chain, the EU policy priorities precede implementation by national governments. Subsequently, end effects of the EU policy guidelines on pension adequacy become visible.

3 Activities within a socio-economic system inter alia include employment, labour participation, duration and the amount of social security contributions and tax payments for re-distributive schemes.

4 Other EU’s intervention instruments include direct (directives and regulations), unintended (jurisprudence of the European Court of Justice), and voluntary (open method of coordination) actions (Pochet Citation2006).

5 The analysis was conducted in R software using QCA (Dusa Citation2019) and SetMethods (Oana and Medzihorsky Citation2018) packages.

6 A condition is necessary if across all cases included in a sample it has higher set-membership in it than in the outcome (super-set relation).

A condition is sufficient if it has lower or equal set-membership in it than in the outcome of interest (sub-set relation) (Schneider and Wagemann Citation2012, 330–333).

7 One needs to define qualitative anchors for full membership in a set/condition (1); full non-membership in a set/condition (0); the point of maximum fuzziness (0.5).

8 The SGP condition is a logical union of two fiscal indicators under the Stability and Growth Pact: government deficit and gross government debt.

9 Fuzzy scores were assigned to average values of raw data (Eurostat, Citationn.d.) corresponding to the duration of each government within the above-indicated time frame.

10 I set the consistency threshold at 0.89 considering the ‘gap’ in the consistency values for the truth table rows. Ergo, only those truth table rows that have higher consistency score than the threshold are included in the second stage – the logical minimisation.

11 See Appendix 3 for conservative and intermediate solution formulas.

12 Covered cases: Ireland_Kenny, Italy_Renzi, Portugal_Costa, Spain_Zapatero, Spain_Rajoy1, Spain_Rajoy2, Estonia_Ansip, Greece_Tsipras, Latvia_Dombrovskis, Lithuania_Kublisu, Slovakia_Fico1.

13 Recommended measures were aggregated from country-specific recommendation (CSR) documents for Austria (2011–2013, 2014–2017), Belgium (2011–2013) and France (2011–2017) and are available in the Official Journal of the European Union (accessed on August 25, 2019).

14 I consider Lithuania_Kublisu as a deviant (contradictory) case consistency in kind although its membership in outcome is exactly 0.5 (theoretically is should be lower). Netherlands_Rutte2 is not counted in total number of deviant (contradictory) cases consistency in kind as it is covered by the fourth sufficient path which is not interpreted in the article.

15 Consistency threshold for the alternative model is slightly lower (0.83) than for the original (0.89). This is due to using the same criteria for determining the threshold – considering the ‘gap’ in the consistency values for the truth table rows.

References

- Aggregate Replacement Ratio – Eurostat. n.d. Accessed 20 September 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/product?code=tespm100.

- Armstrong, K. A. 2012. “EU Social Policy and the Governance Architecture of Europe 2020.” Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 18 (3): 285–300. doi:10.1177/1024258912448600.

- Bajtelsmit, V., A. Rappaport, and L. Foster. 2013. “Measures of Retirement Benefit Adequacy: Which, Why, for Whom, and How Much?” Society of Actuaries. http://www.soa.org/files/research/projects/research-2013-measures-retirement.pdf.

- Barcevicius, E., T. Weishaupt, and J. Zeitlin. 2014. Assessing the Open Method of Coordination: Institutional Design and National Influence of EU Social Policy Coordination. Work and Welfare in Europe. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Barr, N., and P. Diamond. 2006. “The Economics of Pensions.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 22 (1): 15–39. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grj002.

- Begg, I., and W. Schelkle. 2004. “The Pact Is Dead: Long Live the Pact.” National Institute Economic Review 189 (1): 86–98. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/002795010418900109.

- Bekker, S. 2015. “European Socioeconomic Governance in Action: Coordinating Social Policies in the Third European Semester (pp.1).” OSE paper series. Brussels: Observatorie social europeen.

- Bekker, S., and S. Klosse. 2013. “EU Governance of Economic and Social Policies: Chances and Challenges for Social Europe.” European Journal of Social Law. Tilburg Law School Research Paper No 01/2014. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2367280.

- Benassy-Quere, A. 2015. “Economic Policy Coordination in the Euro Area under the European Semester.” European Parliament – Directore-General for Internal Policies I Economic Governance Support Unit.

- Bonoli, G. 2003. “Two Worlds of Pension Reform in Western Europe.” Comparative Politics 35 (4): 399. doi:10.2307/4150187.

- Borella, M., and E. Fornero. 2009. “Adequacy of Pension Systems in Europe: An Analysis Based on Comprehensive Replacement Rates.” ENEPRI Research Report No. 68. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2033652.

- Bouwen, P., and J. Fischer. 2012. “Towards a Stronger EU Surveillance of Macroeconomic Imbalances: Rationale and Design of the new Procedure.” Reflets et Perspectives de la vie économique 51 (1): 21. doi:10.3917/rpve.511.0021.

- Bovenberg, L., and C. van Ewijk. 2011. “Private pensions for Europe.” CEPR Policy Portal Columns. https://voxeu.org/article/private-pensions-europe.

- Chybalski, F., and E. Marcinkiewicz. 2016. “The Replacement Rate: An Imperfect Indicator of Pension Adequacy in Cross-Country Analyses.” Social Indicators Research 126 (1): 99–117. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-0892-y.

- Copeland, P., and M. Daly. 2015. “Social Europe: from ‘add-on’ to ‘Dependence-Upon’ Economic Integration.” In Social Policy and the Euro Crisis: Quo Vadis Social Europe, edited by A. Crespy, and G. Menz, 140–160. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Copeland, P., and M. Daly. 2018. “The European Semester and EU Social Policy: The European Semester and EU Social Policy.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (5): 1001–1018. doi:10.1111/jcms.12703.

- Costamagna, F. 2013. “Saving Europe ‘Under Strict Conditionality’: A Threat for EU Social Dimension?” LPF Working Paper, No. 7. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2230329.

- Darvas, Z., and A. Leandro. 2015. “The Limitations of Policy Coordination in the Euro Area under the European Semester.” Bruegel Policy Contribution Issue 2015/19. http://bruegel.org/2015/11/the-limitations-of-policy-coordination-in-the-euro-area-under-the-european-semester/.

- Database – Eurostat. n.d. Accessed 20 September 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database.

- Degryse, C., M. Jepsen, and P. Pochet. 2013. “The Euro Crisis and Its Impact on National and European Social Policies.” SSRN Electronic Journal, doi:10.2139/ssrn.2342095.

- D’Erman, V., J. Haas, D. F. Schulz, and A. Verdun. 2019. “Measuring Economic Reform Recommendations under the European Semester: “One Size Fits All” or Tailoring to Member States?” Journal of Contemporary European Research 15 (2): 194–211. doi:10.30950/jcer.v15i2.999.

- Dusa, A. 2019. QCA with R. A Comprehensive Resource. (version 3.4). Springer International Publishing.

- European Commission. 2010. GREEN PAPER – Towards Adequate, Sustainable and Safe European Pension Systems. SEC(2010)830. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission. 2012. An Agenda for Adequate, Safe and Sustainable Pensions: White Paper. Publications Office of the European Union.

- European Parliament. 2011. “Pension systems in the EU – contingent liabilities and assets in the public and private sector.” IZA research report No. 42. http://ftp.iza.org/report_pdfs/iza_report_42.pdf.

- European Parliament. 2015. “European Union Pension Systems. Adequate and Sustainable?” Briefing November 2015. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_BRI(2015)571327.

- European Parliament. 2015. “Prospects for Occupational Pensions in the European Union.” Briefing, September 2015. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_BRI(2015)568328.

- European Parliament-Directorate-General for Internal Policies. 2014. “Pension Schemes.” Study for the EMPL Committee.

- Ferrera, M. 2005. The Boundaries of Welfare: European Integration and the New Spatial Politics of Social Protection. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- García-Castro, R., and M. A. Ariño. 2016. “A General Approach to Panel Data Set-Theoretic Research.” International Journal of Management and Decision Making 1 (1): 11–41.

- Grech, A. G. 2013. “Assessing the Sustainability of Pension Reforms in Europe.” Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy 29 (2): 143–162. doi:10.1080/21699763.2013.836980.

- Grech, A. 2015. “Evaluating the Possible Impact of Pension Reforms on Elderly Poverty in Europe.” Social Policy & Administration 49 (1): 68–87. doi:10.1111/spol.12084.

- Gren, K.-J., N. Jannsen, and S. Kooths. 2015. “Economic Policy Coordination in the Euro Area under the European Semester.” European Parliament – Directore-General for Internal Policies I Economic Governance Support Unit.

- Gros, D., and C. Alcidi. 2015. “Economic Policy Coordination in the Euro Area Under the European Semester.” CEPS Special Report No. 123. https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/economic-policy-coordination-euro-area-under-european-semester /.

- Guardiancich, I., and D. Natali. 2017. “The Changing EU ‘Pension Programme’: Policy Tools and Ideas in the Shadow of the Crisis.” In The New Pension Mix in Europe. Recent Reforms, Their Distributional Effects and Political Dynamics, edited by D. Natali, 239–264. Brussels: PIE-Peter Lang.

- Guidi, M., and I. Guardiancich. 2018. “Intergovernmental or Supranational Integration? A Quantitative Analysis of Pension Recommendations in the European Semester.” European Union Politics, June, 1465116518781029. doi:10.1177/1465116518781029.

- Hassenteufel, P., and B. Palier. 2015. “Still the Sound of Silence? Towards a New Phase in the Europeanisation of Welfare State Policies in France.” Comparative European Politics 13 (1): 112–130. doi:10.1057/cep.2014.44.

- Heipertz, M., and A. Verdun. 2004. “The Dog That Would Never Bite? What We Can Learn from the Origins of the Stability and Growth Pact.” Journal of European Public Policy 11 (5): 765–780. doi:10.1080/1350176042000273522.

- Hemerijck, A. 2006. “Recalibrating Europe’s Semi-Sovereign Welfare States.” Discussion Papers, Research Unit: Labor Market Policy and Employment SP I 2006-103. WZB Berlin Social Science Center. https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/zbwwzblpe/spi2006103.htm.

- Holzmann, R. 1998. “A World Bank Perspective on Pension” SP Discussion Paper No.9807. http://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6314371.pdf.

- Jacquot, S. 2008. “National Welfare State Reforms and the Question of Europeanization: From Impact to Usages.” REC-WP Working Papers on the Reconciliation of Work and Welfare in Europe No. 01-2008. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1489862.

- Kvist, J. 2013. “The Post-Crisis European Social Model: Developing or Dismantling Social Investments?” Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy 29 (1): 91–107. doi:10.1080/21699763.2013.809666.

- Leibfried, S. 2010. “Social Policy Left to the Judges and the Markets?” In Policy-Making in the European Union 6th ed., edited by H. Wallace, A. Mark Pollack, and A. R. Young. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordpoliticstrove.com/view/10.1093/hepl/9780199689675.001.0001/hepl-9780199689675-chapter-11.

- Leibfried, S., and P. Pierson. 1995. European Social Policy: Between Fragmentation and Integration. Washington, DC: Brookings Inst Press. https://books.google.lu/books?id=K4fCAAAAIAAJ.

- Melbourne Mercer. 2011. “ Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index”. Australian Centre for Financial Studies.

- Myles, J., and P. Pierson. 2001. “Comparative Political Economy of Pension Reform.” In The New Politics of the Welfare State, edited by P. Pierson, 305–334. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Natali, D., and F. Stamati. 2013. “Reforming Pensions in Europe: A Comparative Country Analysis.” ETUI Working Paper 2013.08. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2376720.

- Nordheim, F. v. 2016. “‘The 2015 Pension Adequacy Report’s Examination Of Extended Working Lives as a Route to Future Pension Adequacy’.” Intereconomics 51 (3): 125–134. doi:10.1007/s10272-016-0590-2.

- Oana, I.-E., and J. Medzihorsky. 2018. SetMethods: Functions for Set-Theoretic Multi-Method Research and Advanced QCA. R Package Version 2.4. (version 2.4). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=SetMethods.

- Ostry, J. D., and A. R. Ghosh. 2013. “Obstacles to International Policy Coordination, and How to Overcome Them.” 13/11. IMF Staff Discussion Notes. International Monetary Fund. https://ideas.repec.org/p/imf/imfsdn/13-11.html.

- Palinkas, I., and S. Bekker. 2012. “The Impact of the Financial Crisis on EU Economic Governance: A Struggle between Hard and Soft Law and Expansion of the EU Competences?” Tilburg Law Review 17 (2): 360–366. doi:10.1163/22112596-01702025.

- Parent, A.-S. 2011. “Can the EU Achieve Adequate, Sustainable and Safe Pensions for All in the Coming Decades?” Pensions: An International Journal 16 (3): 168–174. doi:10.1057/pm.2011.13.

- Parker, O., and R. Pye. 2018. “Mobilising Social Rights in EU Economic Governance: A Pragmatic Challenge to Neoliberal Europe” Comparative European Politics 16 (5): 805–824. doi:10.1057/s41295-017-0102-1.

- Pochet, P. 2006. “Influence of European Intergration on National Social Policy Reforms.” Paper prepared for the conference A Long Goodbye to Bismarck? The Politics of Welfare Reforms in Continental Europe. Minda de Gunzburg Centre for European Studies, Harvard University 16/17 June 2006.

- Porte, C. D. L., and E. Heins. 2015. “A New Era of European Integration? Governance of Labour Market and Social Policy since the Sovereign Debt Crisis.” Comparative European Politics 13 (1): 8–28. doi:10.1057/cep.2014.39.

- Poteraj, J. 2008. “Pension Systems in 27 EU Countries”. MPRA Paper. University Library of Munich.

- Ragin, C. 2008. Redesigning Social Inquiry - Fuzzy Sets and Beyond. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Sacchi, S. 2015. “Conditionality by Other Means: EU Involvement in Italy’s Structural Reforms in the Sovereign Debt Crisis.” Comparative European Politics 13: 77–92. doi:10.1057/cep.2014.42.

- Scharpf, F. 2002. “The European Social Model: Coping with the Challenges of Diversity”. MPIfG Working Paper 02/8, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies.

- Schneider, C. Q., and I. Rohlfing. 2013. “Combining QCA and Process Tracing in Set-Theoretic Multi-Method Research.” Sociological Methods & Research 42 (4): 559–597. doi:10.1177/0049124113481341.

- Schneider, C., and C. Wagemann. 2012. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences – A Guide to Qaualtiative Comparative Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Šikulová, I. 2015. “Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure in The Euro Area–Ex Post Analysis.” European Scientific Journal, ESJ 11 (10), http://www.eujournal.org/index.php/esj/article/view/6147.

- Taylor-Gooby, P. 2005. Ideas and Welfare State Reform in Western Europe. 1st ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9781403993175.

- Urquijo, L. G. 2017. “The Europeanisation of Policy to Address Poverty under the New Economic Governance: The Contribution of the European Semester.” Journal of Poverty and Social Justice 25 (1): 49–64. doi:10.1332/175982716X14822521840999.

- Van Derhei, J. 2006. “Measuring Retirement Income Adequacy: Calculating Realistic Income Replacement Rates.” EBRI Issue Brief No. 297. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=931422.

- Verdun, A., and J. Zeitlin. 2018. “Introduction: The European Semester as a New Architecture of EU Socioeconomic Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (2): 137–148. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1363807.

- Walker, R. 2005. Social Security and Welfare: Concepts and Comparisons. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. https://books.google.lu/books?id=ciJHAAAAMAAJ.

- Wehlau, D., and J. Sommer. 2004. “Pension Policies after EU Enlargement: Between Financial Market Integration and Sustainability of Public Finances,” Working papers of the ZeS 10/2004, University of Bremen, Centre for Social Policy Research (ZeS). http://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/10941.

- Windwehr, J. 2017. “Europeanization in Pension Policy: The Crisis as a Game-Changer?” Journal of Contemporary European Research 13 (3), https://www.jcer.net/index.php/jcer/article/view/818.

- Woolfson, C., and J. Sommers. 2016. “Austerity and the Demise of Social Europe: The Baltic Model versus the European Social Model.” Globalizations 13 (1): 78–93. doi:10.1080/14747731.2015.1052623.

- Zaidi, A. 2010. “Sustainability and Adequacy of Pensions in EU Countries. A Cross-National Perspective.” European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research, Vienna. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Asghar_Zaidi2/publication/242640457_Sustainability_and_adequacy_of_pensions_in_EU_countries/links/53f3249f0cf2da8797445199.pdf.

- Zeitlin, J., and B. Vanhercke. 2018. “Socializing the European Semester: EU Social and Economic Policy Co-ordination in Crisis and Beyond.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (2): 149–174. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1363269.