ABSTRACT

Technology entrepreneurs have endorsed a universal basic income (UBI) as a remedy against disruptions of the work force due to automation. The advancement of information technologies could thus drastically reshape welfare state policy, but its impact on citizens’ preferences about UBI is unexplored. We extend previous research on citizens’ preferences showing a link between job automation and demand for redistribution to the case of UBI preferences. Using European Social Survey data in 21 countries, we find no association between risk of job automation and UBI support. Our findings suggest that UBI and redistribution preferences differ in two important ways: First, opinion formation about UBI is still ongoing. Second, demand for UBI is lower than demand for redistribution, and traditional supporters of redistribution are sceptical about an UBI. This points to the multidimensionality of policy preferences. Its universalistic nature could imply that UBI support is more culturally driven than traditional welfare policies.

Introduction

The universal basic income, the idea of ‘an income paid by a political community to all its members on an individual basis, without means test or work requirement' (Van Parijs Citation2004, 8), has been discussed in various countries as a response to technological change. The point of departure in these debates is that advances in information technology are profoundly shaking up the employment structure. Jobs that involve a high share of routine tasks are at risk of automation, as computers can substitute work in repetitive task structures by following explicit rules (Autor, Levy, and Murnane Citation2003; Autor and Dorn Citation2013; Goos, Manning, and Salomons Citation2014). The upshot is not that technological change leads to mass unemployment, but rather that the risk of unemployment or income loss is unequally distributed; it is particularly pronounced among middle-skilled individuals in routine occupations (Kurer and Gallego Citation2019). Most models in comparative political economy predict that this type of strong risk exposure creates a demand for non-market social insurance (Iversen and Soskice Citation2001; Rehm Citation2009, Citation2016).

The advancement of information technology and its induced changes of the workforce could thus require restructuring the welfare state, for example exploring a universal basic income. Recently, the idea gained renewed support from unexpected sources. Technology entrepreneurs, including SpaceX founder Elon Musk, as well as Facebook founders Chris Hughes and Mark Zuckerberg, have endorsed the universal basic income as a potential social policy solution to occupational risks from automation (see Hughes Citation2018).Footnote1 A candidate in the 2020 US Democratic Primaries (Andrew Yang) even ran his platform predominantly on this issue. In Switzerland, a popular initiative calling for a universal basic income amongst other with those arguments was rejected in 2016, and Finland implemented a large-scale experiment in 2016/2017 to test the consequences of such a scheme (Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont Citation2020). Finally, the Five Star Movement government in Italy launched a ‘citizens’ income' in 2019. This demonstrates that an UBI, and thus a possible solution for the consequences of technological advancement, has reached the policy making process.

Despite the attention that these statements generate, most attempts at implementing such a scheme have been rejected so far – given the likely costs of such a scheme, but also scepticism of replacing existing welfare state benefits with an unknown system. The idea behind a basic income has been around for a while and can be seen as a solution from quite diverse backgrounds for the changes induced by technological change (Cholbi and Weber Citation2019). The political feasibility of a universal basic income likely depends on public opinion support among citizens more broadly, and a few studies have explored general patterns of public support for a universal basic income using the European Social Survey (Martinelli Citation2019; Parolin and Siöland Citation2019; Vlandas Citation2019, Citation2020).Footnote2 Given the foreseeable changes of the workforce due to automation, could this change the feasibility of a basic income in public opinion? Against this background, this research note explores the politics of the universal basic income as a possible remedy against the disruptions from technological change, and therefore the role of information technologies in reshaping welfare state policy.

Two comparative studies, Kitschelt and Rehm (Citation2014) and Thewissen and Rueda (Citation2019), have found empirical support for the proposition that individuals in routine occupations are more likely to support redistribution, defined as agreement to the statement that the ‘government should take measures to reduce differences in income levels’. The study by Thewissen and Rueda (Citation2019), which is based on a direct measure for ‘routine task intensity', furthermore finds that this effect is stronger for high-income individuals that have more to lose from the risk of automation. In their model, redistribution preferences may be seen as a shorthand to capture both the redistributive and insurance functions of the welfare state. Changes in risk exposure, due to technological change, for example, create uncertainty about future income and this nurtures individuals’ demand for government redistribution (Rehm Citation2009).

However, it is equally possible that the effects of technological change vary in other social policy areas, and that there are policies which might be particularly popular as remedies against the disrupting effects from technological change, such as the universal basic income. In this research note, we test whether risk of automation affects individuals’ support for the universal basic income. Our empirical analysis replicates the analysis by Thewissen and Rueda (Citation2019), using the same data on routine task intensity on a different dependent variable: support for introducing a basic income scheme. Using data from the European Social Survey from 21 European countries in 2016/2017 (Wave 8), we first describe average support levels for the universal basic income across countries and then use multilevel regression analysis at the individual level.

Our main argument is that the politics of basic income differ in essential ways from the politics of redistribution. By and large, individuals with lower socio-economic resources and higher exposure to labour market risk are expected to support both a universal basic income and welfare policies more generally (Vlandas Citation2019, Citation2020). But policy preferences are multi-dimensional, and the particular characteristic of the basic income is its universalistic nature. From the welfare state literature, we can expect that this universality appeals more to the middle-class constituency of the ‘new left', such as socio-cultural professionals, than to the traditional working-class constituency of the ‘old left' (Beramendi et al. Citation2015; Gingrich and Häusermann Citation2015). The risks of job automation are disproportionally concentrated among routine workers in the middle of the skills and earnings distribution (Kurer and Gallego Citation2019), who have a strong interest in traditional income support but not necessarily in a universal system that would replace parts of the existing welfare system. Thus, we expect not only that the association with automation risk is weaker for UBI preferences than redistribution preferences, but also that the effects of other individual-level characteristics could differ between the two policy areas.

A caveat to our argument is that people may have vastly different conceptions and preferences about the design of a UBI. The design of a basic income scheme most notably has quite different possible levels of generosity, ranging from a minimum support on top of other welfare schemes to an extensive replacement of all other security nets (De Wispelaere and Stirton Citation2004; Van Parijs Citation2004; Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont Citation2020). In many ways, these questions about policy design are also an issue for redistribution and welfare preferences more broadly, since these preferences reflect policy feedbacks from existing welfare state institutions (for a recent overview, see Busemeyer et al. Citation2019). While we need to be cautious about the specific question formulation in the survey items with which we operationalize UBI support, we do not see the UBI support question to be more problematic than the question about redistribution. The only thing that is clearly likely is that the hypothetical nature of the UBI debate makes it difficult for individuals to take a clear position until country-specific proposals go into a clear direction. Hence, we expect that the opinion formation process is still ongoing with many respondents avoiding clear-cut positions.

The remainder of this research note puts our argument to an empirical test. In the next section, we describe our two main measures, support for the universal basic income and routine task intensity, as well as the control variables and empirical setup. We then present our findings, closely replicating the study by Thewissen and Rueda (Citation2019). In the concluding section, we discuss two features that make the universal basic income essentially different from traditional redistribution policy: first, the large share of undecided voters that indicate that the opinion formation process is still ongoing, and second, resistance against the UBI from traditional redistribution support groups (older, non-tertiary educated, trade union members). The latter finding highlights the importance to study the multidimensionality of policy preferences. Its universalistic nature could imply that UBI support is more culturally driven than other welfare policies.

Data

Support for universal basic income

Our dependent variable is support for universal basic income. In round 8 (2016/2017) the European Social Survey included a module on welfare attitudes, which also asked respondents if they would generally be in favour or against a universal basic income in their country. The description of the scheme was rather general and included the following features:

The government pays everyone a monthly income to cover essential living costs. It replaces many other social benefits. The purpose is to guarantee everyone a minimum standard of living. Everyone receives the same amount regardless of whether or not they are working. People also keep the money they earn from work or other sources. This scheme is paid for by taxes. (ESS 2016/2017)

Automation risk (routine task intensity)

Our key independent variable captures occupations’ vulnerability to technological change. We use the ‘routine task intensity’ (RTI) index from Goos, Manning, and Salomons (Citation2014), which builds on the distinction between routine, manual and abstract tasks in Autor, Levy, and Murnane (Citation2003). The RTI index is available at the occupational level. We convert the ESS’s four-digit occupational codes based on ISCO-08 (the International Standard Classification of Occupations) into ISCO-88 codes using the correspondence table by the International Labour Organization (ILO).Footnote3 Then we assign RTI scores from Goos, Manning, and Salomons (Citation2014) to these occupations.Footnote4 The RTI index ranges from –1.52 to 2.24; higher values indicate jobs with more routine task inputs and a higher risk of automation (under the assumption that technological change is routine-biased). While this measure has its limitations – it was originally developed by Autor, Levy, and Murnane (Citation2003) from a US occupational dictionary from the late 1970s – it is still widely used to measure the routineness of an occupation and is used as a proxy for automation by Thewissen and Rueda (Citation2019).

Model and control variables

We use cross-sectional data from 21 countries in the ESS survey (excluding Russia and Israel). For the model, we follow Thewissen and Rueda (Citation2019), first replicating their results for redistribution preferences, and then using the same models to estimate basic income attitudes. We mirror their approach using multilevel OLS models with random country intercepts.

Besides the attitude towards a basic income scheme and the automation risk, the models include the same control variables as Thewissen and Rueda (Citation2019). This includes household income rank (in country-specific deciles), the years of education (capped at 24 years), gender, age in years, membership in a trade union, the degree of religiosity, and if a respondent is unemployed. For the country level, we consider a lag of social spending and a lag of unemployment (source: AMECO database). Finally, we use the ESS question about whether the government should take measures to reduce differences in income levels as our measure for redistribution preferences (ranging from 1 ‘disagree strongly' to 5 ‘agree strongly'). Tables A1 and A2 in the online appendix show that our main results are substantively the same for different combinations of control variables.

Findings

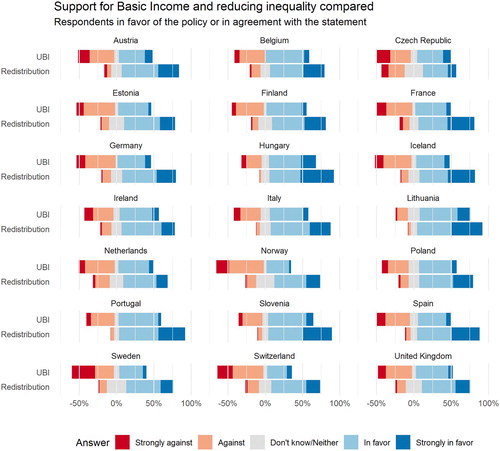

Before turning to the results from the replicated models, we look at the results of the question on the basic income in a descriptive way. presents the results for the 21 countries in the 2016/2017 ESS survey, splitting respondents by response. For each country, we show both the answer to the support for the introduction of a basic income, as well as agreement with the statement that government should reduce inequality.

As we can clearly see, opinion towards the basic income is not yet formed in most countries. Most citizens tend towards the less strong answers and the share of ‘don’t know' answers is substantial (seven percent across all respondents). Even in those countries with a public debate on the basic income opinions are not developed strongly. For example, in Switzerland, the data collection of the ESS wave 2016/2017 is documented to have started three months after a popular vote on a popular initiative for introducing the basic income, which was rejected by 76 percent of the people. Still, only a fraction of respondents to the ESS survey have a strong opinion towards a basic income. Similarly, in Finland, during the time of the ESS fielding in 2016/2017, an experiment was started and therefore present in the media – with notably no effect on a more developed public opinion compared to other countries without such established debates.

In comparison with basic income, we see generally higher support for redistribution policy and a higher share of strong agreement towards the statement that government should take measures to reduce inequality. Given the different type of question, the middle category has to be interpreted differently in for the answers to redistribution. The share of ‘neither' represents respondents who are neither rejecting nor supporting such a suggestion. Interestingly, in both cases, support for the two policies is lowest in Nordic countries, where the welfare state is much more developed – suggesting both that the call for redistribution is less strong with a generous welfare state, and suggesting that replacing an established generous welfare state with a basic income scheme is unpopular under the current conditions. A more distinct comparison is possible with the bivariate plot by country in Figure A1 available in the online appendix.

In a more systematic approach, we replicate the results for redistribution preferences by Thewissen and Rueda (Citation2019) with the new data of the ESS, and estimate the same models for the basic income. In , we present the full models for both policy domains, while Table A1 and A2 in the online appendix include the stepwise models for both redistribution and basic income support. Although we use more recent data with other countries included, the results in for redistribution support are almost identical to the results by Thewissen and Rueda (Citation2019, 184).

Table 1. Preferences for redistribution and universal basic income.

The main question of interest in both cases is about the effects of the risks of job automation, measured by the routine task intensity (RTI) index. For redistribution preferences, we can corroborate the finding of Thewissen and Rueda (Citation2019) that higher RTI is associated with more demand for redistribution. However, the picture is strikingly different with basic income preferences: individuals with higher RTI values are not more likely to support a basic income. The sign of the coefficient is even negative, though not statistically significant. Therefore, the basic income, discussed in the public as a specific solution to technological change involving automation, is not perceived as a solution to this problem by those whose occupations are most exposed to this development.

One reason that we do not find a significant (and substantively large) association between RTI and basic income support might be that respondents interpret the design for a new policy like the UBI in very different ways, resulting in opposing views within groups with similar RTI scores. The fact that confidence intervals for RTI, and other covariates, are comparable in size in both models, though, indicates that estimates for UBI support are not generally estimated more ‘noisily' than for redistribution support. It might be that people with similar levels of RTI simply disagree on implementing a UBI in practice.

The second noteworthy finding in the comparison of the two policy domains in is that the socio-economic characteristics between the two variables differ. Income, religiosity and being unemployed has a similar effect on both redistribution and basic income preferences. However, the effects of education and age go in different directions, whereas high-educated young respondents are opposed to reducing income differences but are in favour of a basic income. The same is true for men, who are more opposed to redistribution but tend more in favour to basic income compared to women (although the latter effect is not statistically perceivable). It is beyond the scope of this note to investigate this surprising finding, but it mirrors other findings that women tend to support social investment less than men (Garritzmann, Busemeyer, and Neimanns Citation2018, 856), and it is important to note that the gender effect is very heterogeneous across countries (Vlandas Citation2019, 15). Finally, trade union members are significantly more in favour of both policy domains than non-members, but the effect size is much smaller for basic income than redistribution.

To sum up, our findings indicate that individuals with jobs at risk of automation are not more supportive of a basic income. Moreover, it appears that the basic income is met with scepticism among traditional supporter groups of the welfare state: low-educated, older citizens, women and, to a lesser extent, union members. As indicated in the online appendix (Table A3), these findings are robust to different model specifications and different operationalization of the RTI index. We also find no evidence that the RTI effect is conditional on income, as Thewissen and Rueda (Citation2019) found for redistribution preferences, and our findings are substantially unaltered if we control for between-group differences in occupational status or social class, which both might confound the relationship between automation risk and preferences (see models A3.5-A3.7 in Table A3).

Conclusion

While the transformative nature of technological change is widely recognized, there is little agreement about whether and how governments should step in to compensate those facing risks in this process. The belief is that technological development, and notably the automation of job tasks, redefines many professions and replaces some completely, putting a large share of the work force in an uncharted place as to whether their job will still be available tomorrow, or if their skills are sufficient for new prerequisites of a developing profession. In principle, a universal basic income might be a remedy against these technological changes, therefore we have set out to analyse citizens’ preference on basic income against the background of their automation risks.

Our empirical analysis of ESS data in 21 countries in 2016–2017 finds that there is no association between job automation and basic income support. Being in a job with high routine task intensity leads to a call for redistribution (Thewissen and Rueda Citation2019), but not to support for a basic income, a policy that is advocated as a potential social policy reaction to occupational risks due to automation. Rather than those at risk of automation, we found that basic income support is particularly pronounced among high-educated, younger citizens. Hence, the political support coalition behind basic income appears to differ in essential ways from the policy domain of income redistribution. Although more systematic analysis is needed, our findings seem to be in line with research on multidimensional preferences, pointing to a divide in the political support coalitions of the welfare state between the old working class and the new middle-class (Beramendi et al. Citation2015; Gingrich and Häusermann Citation2015). Consistent with other findings that anti-immigration and welfare chauvinist attitudes are associated with lower UBI support (Parolin and Siöland Citation2019; Vlandas Citation2020), this would imply that the politics of UBI are rooted in socio-cultural divides – to a larger extent than traditional welfare policies.

We further showed that the majority of respondents does not hold a strong opinion about basic income and thus the patterns of support may yet shift in the future. It is noteworthy that our results, while finding no effect of the risk of job automation, show very clearly that unemployed individuals are much more likely to support a basic income. This implies that once individuals are actually affected by job loss, they become much more in favour of basic income, very similarly as they become more in favour of redistribution (cf. Martinelli Citation2019). The unknown consequences or design of a universal basic income leaves individuals in doubt about the possible effect of such a solution, and therefore sceptical about such a change to the welfare state. Those already depending on the welfare state, on the other side, would support unconditional policies which give them more freedom to gain a foothold in the economy.

It is no coincidence that this distinction between actual and potential decline features prominently on the research agenda about the consequences of economic changes for radical right party support (Gidron and Hall Citation2017; Kurer and Palier Citation2019; Engler and Weisstanner Citation2020; Kurer Citation2020), whereas actual job loss moves voters to the left (Wiertz and Rodon Citation2019). Our study contributes to this debate by showing that individuals whose job is at risk of being automated do not view a universal basic income as a viable remedy.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (215.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Tim Goedemé, Brian Nolan, Isabelle Stadelmann-Steffen, Tim Vlandas and the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 https://www.cnbc.com/2016/11/04/elon-musk-robots-will-take-your-jobs-government-will-have-to-pay-your-wage.html; https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2017/05/mark-zuckerbergs-speech-as-written-for-harvards-class-of-2017/.

2 Martinelli (Citation2019) follows a similar approach to our study and arrives at similar conclusions.

4 RTI scores are missing for six occupational groups. For robustness checks, we assign scores suggested by Thewissen and Rueda (Citation2019, 188) to these occupations. We obtain similar results (see Table A3 in the Online Appendix).

References

- Autor, D. H., and D. Dorn. 2013. “The Growth of Low-Skill Service Jobs and the Polarization of the US Labor Market.” American Economic Review 103 (5): 1553–1597. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.5.1553

- Autor, D. H., F. Levy, and R. J. Murnane. 2003. “The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (4): 1279–1333. doi: 10.1162/003355303322552801

- Beramendi, P., S. Häusermann, H. Kitschelt, and H. Kriesi. 2015. “Introduction: The Politics of Advanced Capitalism.” In The Politics of Advanced Capitalism, edited by P. Beramendi, S. Häusermann, H. Kitschelt, and H. Kriesi, 1–64. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Busemeyer, M. R., A. Abrassart, S. Nezi, and R. Nezi. 2019. “Beyond Positive and Negative: New Perspectives on Feedback Effects in Public Opinion on the Welfare State.” British Journal of Political Science, Online first: 1–26. doi: 10.1017/S0007123418000534

- Cholbi, M., and M. Weber. 2019. The Future of Work, Technology, and Basic Income. New York: Routledge.

- De Wispelaere, J., and L. Stirton. 2004. “The Many Faces of Universal Basic Income.” The Political Quarterly 75 (3): 266–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-923X.2004.00611.x

- Engler, S., and D. Weisstanner. 2020. “The Threat of Social Decline: Income Inequality and Radical Right Support.” Journal of European Public Policy, Online first: 1–21. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2020.1733636

- Garritzmann, J. L., M. R. Busemeyer, and E. Neimanns. 2018. “Public Demand for Social Investment: new Supporting Coalitions for Welfare State Reform in Western Europe?” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (6): 844–861. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2017.1401107

- Gidron, N., and P. A. Hall. 2017. “The Politics of Social Status: Economic and Cultural Roots of the Populist Right.” The British Journal of Sociology 68 (S1): S57–S84.

- Gingrich, J., and S. Häusermann. 2015. “The Decline of the Working-Class Vote, the Reconfiguration of the Welfare Support Coalition and Consequences for the Welfare State.” Journal of European Social Policy 25 (1): 50–75. doi: 10.1177/0958928714556970

- Goos, M., A. Manning, and A. Salomons. 2014. “Explaining Job Polarization: Routine-Biased Technological Change and Offshoring.” American Economic Review 104 (8): 2509–2526. doi: 10.1257/aer.104.8.2509

- Hughes, C. 2018. Fair Shot: Rethinking Inequality and How We Earn. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Iversen, T., and D. Soskice. 2001. “An Asset Theory of Social Policy Preferences.” American Political Science Review 95 (4): 875–893. doi: 10.1017/S0003055400400079

- Kitschelt, H., and P. Rehm. 2014. “Occupations as a Site of Political Preference Formation.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (12): 1670–1706. doi: 10.1177/0010414013516066

- Kurer, T. 2020. “The Declining Middle. Occupational Change, Social Status and the Populist Right.” Comparative Political Studies forthcoming.

- Kurer, T., and A. Gallego. 2019. “Distributional Consequences of Technological Change: Worker-Level Evidence.” Research & Politics 6 (1): 2053168018822142.

- Kurer, T., and B. Palier. 2019. “Shrinking and Shouting: the Political Revolt of the Declining Middle in Times of Employment Polarization.” Research & Politics 6 (1): 2053168019831164.

- Martinelli, L. 2019. Basic Income, Automation, and Labour Market Change. Bath: Institute for Public Policy Research, University of Bath.

- Parolin, Z., and L. Siöland. 2019. “Support for a Universal Basic Income: A Demand–Capacity Paradox?” Journal of European Social Policy 30 (1): 5–19. doi: 10.1177/0958928719886525

- Rehm, P. 2009. “Risks and Redistribution: An Individual-Level Analysis.” Comparative Political Studies 42 (7): 855–881. doi: 10.1177/0010414008330595

- Rehm, P. 2016. Risk Inequality and Welfare States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stadelmann-Steffen, I., and C. Dermont. 2020. “Citizens’ Opinions About Basic Income Proposals Compared – A Conjoint Analysis of Finland and Switzerland.” Journal of Social Policy 49 (2): 383-403

- Thewissen, S., and D. Rueda. 2019. “Automation and the Welfare State: Technological Change as a Determinant of Redistribution Preferences.” Comparative Political Studies 52 (2): 171–208. doi: 10.1177/0010414017740600

- Van Parijs, P. 2004. “Basic Income: A Simple and Powerful Idea for the Twenty-First Century.” Politics & Society 32 (1): 7–39. doi: 10.1177/0032329203261095

- Vlandas, T. 2019. “The Politics of the Basic Income Guarantee: Analysing Individual Support in Europe.” Basic Income Studies 14: 1. doi: 10.1515/bis-2018-0021

- Vlandas, T. 2020. “The Political Economy of Individual Level Support for the Basic Income in Europe.” Journal of European Social Policy (forthcoming).

- Wiertz, D., and T. Rodon. 2019. “Frozen or Malleable? Political Ideology in the Face of job Loss and Unemployment.” Socio-Economic Review.