?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This article carries out a quantitative analysis of the military behaviour of Italy from 1946 to 2010 using neoclassical realism as the theoretical framework. By overcoming the limits of traditional explanations of Italian security and defence policies, neoclassical realism provides new insight into Italy’s involvement in militarized interstate disputes by taking into account both systemic and domestic variables. The method used is a combination of dyad analysis introduced by Stuart Bremer in 1992 and the analysis of unit-level variables, which is distinctive of neoclassical realism. An analytical model is developed, and bivariate and multivariate analyses are performed to explain the impact of the variables. By empirically testing a set of hypotheses, the study argues that Italian military behaviour is a function of the country’s relative power as well as the levels of elite instability and regime vulnerability, the extraction capacity of the state, and the degree of elite consensus. The study contributes to the existing scientific debate on the determinants of Italian international behaviour and to the literature on neoclassical realism by demonstrating that its main propositions apply to a case of middle power and that these propositions can be tested on a large scale through quantitative approaches.

Introduction

Using neoclassical realism as the theoretical framework, this article carries out a preliminary quantitative analysis of the impact of both international and domestic variables in explaining Italy’s military behaviour. The period considered spans from the end of World War II to 2010.Footnote1 The method used is a combination of dyads analysis introduced by Stuart Bremer in 1992 and the analysis of unit-level variables, which is distinctive of neoclassical realism. In the first section, the traditional accounts of Italian military behaviour are examined, and their limits and shortcomings in explaining how and why Italy became involved in military disputes are highlighted. In the second section, the neoclassical realist approach is presented as an effective alternative that can enhance our understanding of Italian military behaviour. In the third section, the analytical model is delineated, hypotheses are formulated, and the variables are operationalized. In the fourth section, the empirical data are analysed, and in the conclusion the evidence is summarized and discussed.

The article presents the argument that – as correctly predicted by our neoclassical realism-inspired model – Italian military behaviour represents reactions to changes in the balance of power, but at the same time, it is also a function of the country’s levels of elite instability and regime vulnerability, the extraction capacity of the state, and the degree of elite consensus regarding the perception of an external threat and the best way to confront it.

The results of the bivariate and multivariate analysis show a substantial consistency between the hypotheses generated by neoclassical realism and the Italian military behaviour. The findings demonstrate that variations in the balance of power prompt Italy to adopt a more assertive military behaviour, but that the systemic-induced effects can be mitigated or enhanced by important domestic conditions, such as the level of regime vulnerability or consensus among the political elites.

Through a theoretically grounded and methodologically rigorous analysis, this study contributes to the existing scholarship on Italy’s foreign policy by providing a general explanation of its military behaviour since the end of World War II. Moreover, the study also contributes to the scientific debate on neoclassical realism by demonstrating that its main propositions apply to a case of middle power such as Italy and that these propositions can be tested on a large scale through quantitative approaches.

Competing explanations for Italy’s military behaviour

The main interpretations of Italy’s international behaviour address, in a somewhat contrasting way, either the constraining effect of international structure or the overriding role played by bottom-up domestic pressures.

According to the first perspective, since the end of the Second World War, Italy’s political and military posture and actions have been constrained by the international system in which the country operated.Footnote2 Pasquino (Citation1974), Di Nolfo (Citation1977, Citation1979), and Santoro (Citation1991) underscored the idea that the advent of the Cold War and its unique ideological character, in addition to its intimate relationship with Western political and military organizations, were cardinal factors that dictated the nature of Italy’s political behaviour for decades. During the course of the Cold War, the bipolar nature of the international system relegated Italy to a marginal international security role as compared to the main rival superpowers. Moreover, Italy’s security interests were assured through its membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Italy, therefore, played a rather passive role in its relationship with the United States (US), typically acquiescing in the political decision-making by Washington’s political elites.

The problem with interpretations centred on external factors is that global structures do not have straightforward effects on a nation’s international behaviour, and different, if not contradictory outcomes, remain a possibility. To understand the direction that a country will assume, one needs to examine unit-level variables (Lobell, Ripsman, and Taliaferro Citation2009).

Internal explanations have provided the basis for opposite accounts of Italy’s international behaviour and its foreign policy directions. Kogan (Citation1963) and Panebianco (Citation1982) postulated that Italy’s post-World War Two international behaviour and trajectory was the by-product of intrinsic socio-political dynamics. That is, Italy’s passive role within the international arena could be traced back to its socio-political traits. As Kogan asserts, the inward-looking essence of Italian political elite is a major determinant of its disinterest in international politics. Italy’s interest in what takes place beyond its borders is potentially rooted in threats toward, or opportunity for, parochial interests of the Italian ruling class. Similarly, Panebianco argues that a passive foreign policy allowed Italy to avoid exacerbating discord or schisms in the realm of domestic politics. Thus, Italy’s political elites abandoned the idea of becoming deeply involved and even enmeshed in controversial political and military actions beyond Italy’s border throughout the Cold War period.

The main limit of these interpretations is their underestimation of systemic effects on Italy’s international behaviour and the range of constraints and opportunities they impose on its foreign and security policy.

The literature produced in the post-Cold War period on Italy’s international behaviour largely replicates the limits of earlier research. Some studies stress the persistent negative impact of highly contentious domestic politics on Italy’s capacity to pursue a more assertive foreign and military policy. The work of Silvestri (Citation1990) and Dottori and Laporta (Citation1995), for example, emphasizes Italy’s difficulties in pursuing a foreign policy tailored to the interests of a middle power, due to the constraints posed both by the functioning of its policy making process (the troubled coordination between the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defence), and a party system that remained fragmented and polarized concerning international affairs (as in the case of the first and second Prodi governments, which encountered numerous problems in managing the country’s foreign policy). Panebianco (Citation1997), analyzing the relations between western democracies and military behaviour, highlights the differences between Italy and the other European democracies in terms of their approach toward the use of force. While other key democracies (such as the US, the UK and France) can be depicted as ‘warrior democracies’ – countries that are prepared to defend their national interests through the use of force, where necessary – Italy always tended to prefer peaceful options. Where it does use force, this is within peacekeeping or peace enforcement missions, under the cover of a multilateral organization’s political umbrella.Footnote3

Other analyses stress the impact of the strategic culture on Italy’s international behaviour (Pirani Citation2008; Rosa Citation2014, Citation2016). The main goal for this branch of research is to explain elements of continuity – rooted in persistent cultural traditions – in Italy’s international behaviour, which appears fundamentally unaltered over time despite structural changes in the international system.

During the past ten years, a new collection of studies on Italian foreign and military behaviour has appeared with more far-reaching and theoretically grounded considerations on the interplay between domestic and international variables. Some are consistent with the model advanced in this research (Newell Citation2011; Walston Citation2011; Brighi Citation2013),Footnote4 and some of them are also based on an explicit neoclassical realist framework (Cladi and Webber Citation2011; Davidson Citation2011).

Elisabetta Brighi’s work is a theoretically informed analysis of Italian foreign policy, from its unification to the post-Cold War period that explores the interplay of context, strategy and discourse. She discusses many aspects of Italy’s international behaviour that are consistent with the present article, but that also differ on important areas. In our view, a neoclassical realist framework offers a better explanation of Italian military behaviour because the role of power and changes in relative power remain at its core and because it provides an in-depth explanation of how domestic factors constrain responses to external events: unit-level variables represent an intervening factor between international stimuli and national responses. Conversely, in Brighi’s analysis, the weight and role of different variables at different level change according to periods and issue-areas. Therefore, it suffers from some form of ‘ad hocism’.

Work by James Newell and James Walston analyses the interplay of domestic politics and foreign policy. As is the case in Brighi’s book, they present many aspects that are consistent with our argumentations. Newell’s analysis of the impact of the transformation of domestic politics on Italy’s foreign policy decisions is particularly interesting and offers many useful insights. However, the period considered is very limited (the post-Cold War period). The same temporal shortcoming is the main limit of Walston’s analysis.

Contrary to previous studies proposing an original theoretical framework or following the tradition of Putnam’s two-level game, both the article by Lorenzo Cladi and Mark Webber and Jason Davidson’s book are clearly embedded in a neoclassical realist approach. Cladi and Webber (Citation2011) advance a neoclassical realist explanation of Italian foreign policy in the post-Cold War period. However, they propose only a narrative interpretation of the 1994–2008 period, and in this respect the present quantitative analysis adds to their more discursive study.

Jason Davidson’s book (Citation2011) offers the most sophisticated neoclassical realist study of Italian foreign policy in the post-Cold War period. Davidson analyses two cases from the Cold War period and five cases from the post-Cold War period. Nevertheless, the analysis defines the role of domestic variables in a very limited way, reducing these to the influence of public opinion and its electoral connection. Another limit is that only a few dramatic cases of alliance politics are taken into account, rather than all the military disputes in which Italy has been involved, thus greatly impeding upon the generalizability of his findings.

To sum up, the main limits of these studies are that they either consider short time frames,Footnote5 focus on a small number of case studies, or take into accounts a limited number of variables. Our ambition is to offer a general model to explain Italian military behaviour in both the Cold War period and in the post-Cold-War period that considers all relevant neoclassical realist variables.

Neoclassical realism seems particularly suitable to understand Italy’s military behaviour: it considers – theoretically framing the direction of causal links – both the pressures stemming from changes in the balance of power and the domestic influences that a highly fragmented political system such as Italy’s exerts on decisions about how to respond to international stimuli. The key features of this perspective are highlighted in the next section.

A neoclassical realist explanation

Neoclassical realism represents a ‘from-within-the-realist-school’ response to the disinterest of Waltz’s structural realism for a theory of foreign policy (Waltz Citation1979).Footnote6 It is a realist response given that it maintains the basic tenets of political realism: Nation-states are the main actors in international politics and the most important input to their behaviour is a balance of power calculus. To this assumption, neoclassical realism adds two important caveats: state (re)action to international stimuli is not straightforward; the shape and pace of a state’s (re)action depends on the characteristics of society and policy makers that act as a sort of ‘transmission belt’ between international events and foreign policy behaviour (Rose Citation1998; Lobell, Ripsman, and Taliaferro Citation2009).

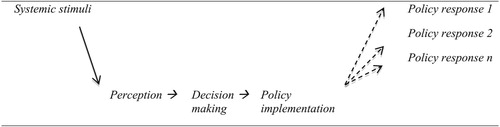

Neoclassical realism analyses three intervening mechanisms that mediate between international stimuli (changes in the balance of power) and national behaviour. The first, located at the individual level, includes the external perceptions of political elite (the central decision makers); the second, located at the domestic level, is the policy-making processes; and the third (also located at the domestic level of analysis) is the operational process of policy implementation. These three mechanisms are influenced by several factors, including: individual belief systems; strategic cultures; governments’ capacity of extracting economic/political resources from society; domestic political/social struggle (Ripsman, Taliaferro, and Lobell Citation2016) (see ).

Figure 1. A neoclassical realist explanation of foreign policy decisions. Source: Ripsman, Taliaferro, and Lobell (Citation2016, 31).

Based on this framework, several general propositions can be inferred in order to explain Italy’s military behaviour. The neorealist baseline proposition is:

P 1. Growth in national power will produce a more assertive foreign policy and military behaviour.

The neoclassical realist propositions are:

P 2. Growth in national power will produce a more assertive foreign policy and military behaviour only if the unit-level variables – the state’s extraction capacity, strategic culture, belief systems, intra-elite relations and regime stability – do not push aside security matters.

P 2.1. If the domestic environment is characterized by a unified elite with a consensual outlook, regime stability, a warlike strategic culture, and a high level of extraction capacity, the most likely result will be assertive military behaviour.

P 2.2. If the domestic environment is characterized by a divided elite, a low level of extraction capacity, a pacifist strategic culture, and regime vulnerability, the most likely result will be low-profile military behaviour.

Research design

Neoclassical realists mostly use qualitative methods to test their research propositions.Footnote7 The use of quantitative methods in the field of international relations has often been criticized either because its main concepts are difficult to measure or because studies were poorly devised in terms of statistical methods and disconnected from relevant theories.Footnote8 We contend that quantitative methods are better suited for the present analysis, for they allow studies to perform tests on a large number of cases and/or across long periods of time and to identify correlation patterns on a large scale with a certain degree of confidence and, from them, draw generalizable conclusions on the process under study. While acknowledging the limitations that are inherent the use of quantitative methods in the analysis of the international behaviour of states, we resort to these methods with the aim of reaching generalizable conclusions regarding the impact of both systemic and domestic variables on the military behaviour of a middle power, Italy, across a large time-span, ranging from the end of the World War Two until 2010. By resorting to quantitative methods, the analysis can exclude that the associations between systemic and domestic variables and Italy’s military behaviour are not only due to chance or idiosyncrasies of a specific moment of international or internal politics, but rather representative of more fundamental patterns of behaviour of the state in the international realm resulting from the interplay of systemic with domestic factors.

Through these methods, the study takes up the task of testing the hypothesis emerging from an established theory, rather then the task of building a new or updated version of the neoclassical realist one. In so doing, the study not only investigates the determinants of Italy’s military behaviour but, most importantly, it tests whether the tenets of neoclassical realism hold in the case of a middle power such as Italy. With this endeavour, the study contributes to the existing research with generalizable findings that analysis based on qualitative interpretations that focus on limited time periods have not been able to produce.

Our model asserts that the military behaviour of Italy (MiB) is a function of its relative power (RP), the levels of elite instability (EI) and regime vulnerability (RV), the extraction capacity of the state (ExC), and the degree of elite consensus (EC) regarding the perception of an external threat and the best way to tackle it:The assumed directions of the relations are as follows:

The greater the RP, the more assertive the MiB (the neorealist baseline proposition).

The lower the EI, the more assertive the MiB.

The lower the RV, the more assertive the MiB.

The greater the ExC, the more assertive the MiB.

The greater the EC, the more assertive the MiB.

From this model, it can be inferred that the positive effects of an increase in military power on a nation’s military assertiveness can be hampered by a non-permissive domestic environment (elite and regime instability, a low level of extraction capacity, inconsistent elite perceptions of external threats, and an anti-militarist strategic culture).

Given the resilience of Italy’s strategic culture during the period considered, its contribution to the explanation of Italy’s military behaviour is excluded from this model. A strategic culture approach is more useful for explaining resistance to change and policy continuity (Swidler Citation1986; Johnston Citation1995). Thus, we can assume, as a rule, that the Italian strategic culture will produce a consistent preference for a diplomatic, accomodationist, and multilateral approach to international disputes over the entire period under consideration.Footnote9

Dependent variable

The dependent variable of the study is Italy’s involvement in militarized interstate disputes (MIDs). An MID refers to threat, display, or use of force against another sovereign state. It is operationalized using the Correlates of War (COW) dataset (Jones, Bremer, and Singer Citation1996).Footnote10 To test whether Italy’s military behaviour changes as a function of the systemic and domestic factors discussed above, all the possible dyads that include Italy during the period 1946–2010 are considered and the characteristics of the more conflict-prone dyads in which Italy participated analysed. Dyads analysis was introduced by Bremer (Citation1992) to overcome the limits of analyses of conflictual behaviour centred on the characteristics of the international system (polarity, alliance networks, level of economic interdependence, among others) and of analyses centred on national attributes (type of political regime, decision-making process, belief system, style of leadership, and so on), all of which suffer from the same problem of a limited number of cases (small n), especially for the dependent variable.Footnote11 In this article, we have adopted an in-between approach: the use of dyads analysis to study the behaviour of a single country. In this respect, our unit of analysis is not a dyad but the ‘nation in a dyad per year’: we do not analyse all dyads in a given year, we consider all dyads that include our observed state. The value of this choice is the elimination of the problem of a small n, which would otherwise affect the analysis of a single nation’s behaviour. By not considering the behaviour of Italy in each year from 1946 to 2010 (n = 65) but the likelihood of Italy’s behaviour in every dyad in which it could potentially have been involved throughout this timespan, we can perform a statistical analysis of Italian military behaviour on a larger number of cases (N = 9,283).

Following the conceptualization provided above, Italy’s military behaviour is considered assertive if in a specific year of the dyad it has threatened, displayed, or used force against the other state of the dyad. Accordingly, the variable takes the value of 1 if in a specific dyad-year Italy was involved in an MID with the other state of the dyad, 0 if it was not.

Independent (systemic) variable

The independent variable, relative power (RP) is a measure of national power relative to other states, where states’ national capabilities are used as a proxy for power. The variable is operationalized using the COW’s Comprehensive Index of National Capabilities (CINC). To underline the relative nature of power, Italy’s index has been compared with the indices of the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. Accordingly, Italy’s capability variation is assessed vis-à-vis the share of total power possessed by the most important European nations. The index formula is It/(It + UK + Fr + Ger), and ranges from 0 to 1.Footnote12 The trend (increasing or decreasing) has been calculated by comparing the index at year t with the average index for the period: power is considered high if it is one standard deviation above the average and low if it is one standard deviation under the average. High power not only means an increase in the capacity for force projection but also greater international responsibility. We compare the behaviour of Italy in the dyads in which it acted from a position of high power with its behaviour in the group of dyads in which it held low power. The first hypothesis is as follows:

H1. Under the condition of high power (number of dyads in which Italy’s RP score is one standard deviation above the average), Italy’s military behaviour will be more assertive, and, accordingly, there will be an increase in the likelihood of MID involvement.Footnote13

Unit-level variables (neoclassical realism’s contribution)

Our baseline hypothesis is integrated by the effects of domestic and individual variables, as foreseen by neoclassical realism. The general hypothesis is that the stimuli produced by a change in the balance of power could have limited effects if domestic conditions hamper the conduct of foreign policy.

The first domestic variable considered is elite instability (EI) and measures the state’s domestic political stability. This variable is operationalized using the number of changes of government over a given period: if the number of governments is greater than expected (i.e. one government for each five-year-long legislative session), EI is high and the capacity of the state to effectively use power resources and behave assertively decreases (Hagan Citation1993, Citation1995).Footnote14 To measure elite stability/instability, the technique of the ‘moving average’ has been used. A mean value is calculated based on the two years preceding and following the reference year: e.g. if in 1947 there is one government and in the two previous and subsequent years there are three and two different governments, respectively, this means that there are five changes of government and the index value for 1947 is 1 (five changes of government in five years). When there is no change of government, the value is 0 (maximum stability). Thus, the second operational hypothesis is as follows:

H2. Under the condition of low elite instability (number of dyads in which Italy’s EI score is one standard deviation below the average), Italy’s military behaviour will be more assertive, with an increase in the likelihood of MID involvement.Footnote15

H3. In a situation of low regime vulnerability (number of dyads with Italy showing an RV score in the first tertile), Italy’s military behaviour will be more assertive, and, accordingly, there will be an increase in the likelihood of MID involvement.

H4. Under the condition of a high level of public support for the use of force (number of dyads in which Italy’s ExC score is one standard deviation above the average), Italy’s military behaviour will be more assertive, as national capabilities are more easily transformed into military power for international goals, with a greater likelihood of MID involvement.Footnote21

H5. Under the condition of a high level of elite consensus (number of dyads with Italy showing an EC score in the third tertile), Italy’s military behaviour will be more assertive and, accordingly, there will be a greater likelihood of involvement in an MID.

To test the hypotheses of the study, the analysis is conducted first in a simple bivariate form to assess whether the systemic and domestic factors have an impact on Italy’s military behaviour. Next, a multivariate analysis is performed to measure the effect of each single variable while considering the other variables and controlling for them.Footnote24 The multivariate analysis is carried out through a multilevel binomial logistic regression that includes the main independent variable of the study, RP, and all the other domestic variables.Footnote25 Finally, we use the estimates of the multivariate analysis to compute the probability of Italy’s involvement in an MID conditional on a change in RP, the systemic stimuli, and whether such a probability varies depending on the domestic factors. By doing so, the study will draw conclusions as to whether the baseline proposition holds, namely whether systemic stimuli induce a more assertive military behaviour, and whether domestic factors could alter such an effect, as postulated by the neoclassical realists.

Data analysis

To test the factors that increase or decrease the likelihood of involvement in a military conflict, an analysis has been run on all the MIDs in which Italy was involved in the period 1946–2010. The results are presented in .

Table 1. Conditional probabilities of Italy’s involvement in MIDs by NcR variables, 1946–2010.

With regard to the relative power variable (RP), the data present a picture that is consistent with our baseline assumption. There is a significant impact of relative power on Italy’s inclination to be involved in an MID, as the likelihood for Italy’s involvement in an MID increases considerably in periods of high RP. The probability for Italy to be involved in an MID in a period of high power is almost two times (.0073) the unconditional probability (pu = .0039) and the difference is statistically significant (Z score 2.15, p < .05). These data are in line with the realist (without adjective) proposition that a change in the balance of power is a relevant factor in foreign policy-making and in explaining states’ reaction to international stimuli. Thus, even a middle power such as Italy – that during the Cold war was strongly constrained by its alliance subordinated position – becomes more militarily assertive when its relative power increases.

To integrate the performance of the RP variable, it is necessary to consider unit-level variables (both domestic and individual). The central assumption of neoclassical realism is that domestic factors can trump international considerations and prevent the transformation of national capabilities into a tool of international influence. All the unit-level variables considered act in the direction predicted by the model. However, some are not statistically significant.

Two out of three domestic variables (EI and RV) act in the expected direction. The presence of a low level of elite instability increases the probability of MID involvement from .0039 (pu) to .0073 (low EI). The difference is statistically significant (Z score 2.66, p < .01). Italy’s likelihood to be involved in an MID is roughly two times greater when there is a stable political elite. These data are consistent with the idea that the functioning of domestic politics can condition the effect of a power rise on a nation’s reaction to international events. Thus, the functioning of domestic institutions and their frailty can represent a hurdle to an assertive foreign policy. This result is consistent with the domestic explanation of Italy’s international behaviour (Panebianco Citation1982, Citation1997).

A reduction in regime vulnerability (RV) increases the probability of Italy’s MID involvement from .0039 (pu) to .0065 (low RV), and this difference is statistically significant (Z score 2.38, p < .05). A shift from a situation of high vulnerability to one of low vulnerability increases the probability of MID involvement from .0019 (high RV) to .0065 (low RV). In other words, the risk of Italy being involved in an MID is approximately three times greater in periods of a regime’s ‘good health’. This finding is consistent with the idea that for Italy, social turmoil is more a source of a low-profile foreign policy than a source of diversionary adventures abroad.

The third domestic variable, ExC, does not play an important role. A high level of extraction capacity only increases the likelihood of MID involvement from .0048 (pu) to .0053 (high ExC). This variable does not affect Italy’s military behaviour in a significant way (Z score .23). Comparing situations of low and high ExC, the shift in the likelihood of MID involvement changes from .0052 (low level of ExC) to .0053 (high level of ExC). From these data, it seems that a public support for military behaviour is an irrelevant factor.Footnote26

At the individual level, the most important variable is elite consensus (EC). This is a crucial factor given that, as Schweller states, policymakers’ perceptual consistency ‘is the most proximate cause of a state response or nonresponse to external threats’ (Schweller Citation2006, 47). The critical role attributed by Schweller to leaders’ perception is confirmed in the case of Italy. The EC variable affects the likelihood of Italy’s involvement in MIDs in a significant way. In a situation of high consensus, the probability of MID involvement increases to .0067 vis-à-vis the .0039 score for unconditional probability and is more than three times the probability of involvement in a military dispute when the level of elite consensus is low (.0020). The corresponding Z score of 2.82 is highly significant statistically (p value: p < .01). The crucial role played by this factor is confirmed by the fact that in five cases of Italy’s MID involvement under conditions of low or stable levels of relative power, the scores for the EC variable are high.

To summarize, the analysis of the impact of our international and unit-level variables is consistent with neoclassical realism’s tenets. The variables that more affect the probability of Italy’s military intervention are, in order of importance: the relative power, the elite instability, the level of elite consensus, and the level of regime vulnerability. A high level of relative power (H1), a low level of elite instability (H2), a high level of elite consensus (H5), and a low level of regime vulnerability (H3) increase the likelihood of Italy’s involvement in an MID in a dramatic way. The last variable (ExC) does not work as assumed by the model (H4); even if the association is positive for high ExC, it does not yield statistically significant results.

We now shift to a multivariate analysis in an effort to explain the impact of the variables and, at the same time, the correlations between them. In this way, further light can be shed on the performance of our model, since, as mentioned previously, the positive effect of a high level of power on Italy’s international behaviour can be overridden by a low level of elite consensus, political instability, regime vulnerability, and a limited extraction capacity.

A multilevel binomial logistic regression was run on the 9,283 dyads to test the joint impact of the international and unit-level variables on Italy’s involvement in a militarized dispute. Because the data on extraction capacity are not available before 1981, we have omitted this variable from the analysis. In order to test the impact of the changes in international system (the end of the Cold War and the 9/11terrorist attack) we have introduced two dummy control variables: Cold War (CW), that permits to consider the impact of the end of the confrontation with the former USSR on Italy’s military behaviour, and the 9/11 terrorist attack, that permits to test the effect of the ‘War on Terror’ (WoT) on Italian posture. The results are shown in : Model I considers the whole period 1946–2010; Model II introduces the CW control variable; Model III Introduces the WoT control variable.Footnote27

Table 2. Logit model: Italy’s involvement in MIDs, 1946–2010.

The results present a complex and mixed picture. The logistic regression confirms the central role played by the power variable (Model I). Even taking into account the effects of domestic variables on power politics logic, the positive effect of an increase of RP on Italy’s assertive behaviour still holds. It is statistically significant and acts in the right direction. When considered alone (bivariate analysis), a situation of high RP increases of 87% the probability of Italy’s involvement in an MID;Footnote28 such an increase – in the case of multivariate analysis – is of 100[Exp(B)−1] = 154%. This result can be viewed as very consistent with the neoclassical realist model, which maintains that the effect of power can be modified by the actions of unit-level variables such as regime vulnerability, elite instability, and the level of elite consensus. In our case, a high level of EC and a low level of RV amplify in an impressive way the positive effect of relative power on Italy’s military behaviour. The introduction of control variables CW and WoT (Model II and III) – that weigh the impact of the end of the Cold War and the effect of the emergence of terrorist issue in international agenda – does not produce a great effect on RP. This conclusion, clearly, is not very consistent with the neorealist expectation about the decisive role of international transformation.

The direction of the impact of the unit-level variables is partially confirmed by the multivariate analysis: two out of three domestic and individual variables (RV and EC) act as expected. Conversely, and unexpectedly, elite instability (EI) is not statistically significant and acts in the wrong direction. Of the three domestic variables considered, two are statistically significant: EC (p < .1)Footnote29 and RV (p < .05). This result represents a partial confirmation of neoclassical realism’s framework.

The case of EI is rather puzzling, considering its good performance in bivariate analysis. Perhaps the multivariate inconsistency of this factor can be explained by the fact that, as some scholars of the Italian political system have argued, changes of governments in Italy do not necessarily result in a change of ministers; in other words, governments may change, but not the people holding key political positions (Calise and Mannheimer Citation1982).Footnote30 For example, in the period 1996–2001, there were four governments (Prodi, D’Alema 1, D’Alema 2, Amato), one Minister of Foreign Affairs, and three Ministers of Defence. Thus, when there is a strong policy consensus facilitated by ministers’ stability, the EI variable possibly becomes insignificant in explaining Italy’s MID involvement.Footnote31

In contrast, the RV variable remains significant in the multivariate analysis and its trend is consistent for all three periods (Model I, II and III). Even when considering the joint effects of the four variables, the level of social instability continues to be a good predictor of Italian military behaviour: Italy is always very reluctant to get involved in a military dispute under a condition of regime vulnerability. A shift from a low to a high level of RV decreases by 73% the likelihood of MID involvement.Footnote32

The important role of elite perception (EC) is confirmed by the multivariate analysis. A high degree of elite consensus increases the likelihood of MID involvement. More to the point, a shift of EC from low to high increases by 100[Exp(B)−1] = 122% the likelihood of MID involvement (Model I). In this case, the significance of the variable results more robust when we separate the Cold War period (1946–1989) from the post-Cold War period (1990–2010) (in Model II, EC has a p value < .05). This fact can be interpreted as a confirmation of the constraining impact played by international structure on Italian domestic politics during the Cold War’s years and the altered role played by the unit-level variables under different international conditions (Pasquino Citation1974; Gourevitch Citation1978). By separating the Cold War period from the post-Cold War period, both the weight of RV and EC increase (Model II).

A tentative interpretation of logistic regression’s substantive results is presented in .

Table 3. Determinants of Italy’s military behaviour: predicted probability of involvement in MIDs.

Figures highlight the change in probability in high power situations (systemic variable) and the change in probability in high power conditions depending on the domestic condition (systemic variable plus domestic variable). What can be inferred from these data is that the level of RP, RV and EC is a good predictor of Italy’s involvement in MIDs. More to the point:

The MID involvement probability increases when RP is high (neorealist proposition, significant effect);

The MID involvement probability increases further if there is high elite instability (effect contrary to expectations but not statistically significant);

The MID involvement probability increases further if there is a low vulnerability regime condition (neoclassical realist proposition, RP effect significantly enhanced);

The MID probability decreases following an international stimuli if there is a low elite consensus (neoclassical realist proposition, RP effect significantly mediated).

The neorealist hypothesis is not very consistent with the results of our analysis. If neorealist assumptions were correct, unit-level intervening variables should not change the role of power and Italy’s external behaviour, and, above all, the change of international system (Model II and III) should produce more dramatic effects (this is not the case). In the Waltz’s version of neorealism (Waltz Citation1979; Moravcsik and Legro Citation1999), power distribution is the only significant variable that explains the change of state behaviour in the international arena: states, in deciding how to respond to an international event, are uniquely influenced by their material capabilities (means determine goals). Their choices are dictated by their position in the international structure and not by the parochial interests of individual policy makers or by inputs from society and polity. As Kevin Narizny (Citation2017, 158) states:

Waltz’s status as exemplar of the modern realist paradigm is complicated by the fact that one of the central elements of his theory sharply limits its analytic utility: the distinction between international politics and foreign policy. International politics is about systemic outcomes (e.g. “balances will form against powerful states”); foreign policy is about state behaviour (e.g. “state A will balance against state B”). Waltz argues that his theory explains only the former, not the latter. In his view, the logic of anarchy is so strong that it creates selection pressures on state preferences.Footnote33

That said, it is clear that neorealism and neoclassical realism both belong to the realist family and both stress the paramount role of power. However, ‘NcR constructs a theory of foreign policy wherein the structural environment provides the starting point, but domestic variables play a significant role, in determining foreign policy outcomes’ (Kitchen Citation2020, 11).

As Schweller aptly noted (Citation2004, Citation2006), in order to understand how states translate their political resources in international influence, we need to consider the role of unit-level variables.Footnote34

Conclusion

The approach of neoclassical realism has more than twenty years of history behind it, and it has been refined and applied to numerous studies.Footnote35 These studies have largely relied on qualitative analyses, such as historical-comparative method. As the three most important representatives of this approach state, ‘Since neoclassical realism requires researchers to investigate, among other factors, the role of idiosyncratic state institutions and process on policy choices, it lends itself to careful, qualitative case studies, rather than large-N quantitative analysis’ (Ripsman, Taliaferro, and Lobell Citation2016, 131). Despite this assertion, the study has shown that it is not only possible to resort to quantitative methods but that these methods are well suited for studies that aim to empirically test the propositions of neoclassical realist theory.

In this article, we have developed a statistical model, based on neoclassical realism, that specifies empirically verifiable hypotheses. This attempt encountered some challenges, especially due to the scarcity of reliable data and the difficulty in operationalizing some of the variables. Ultimately, however, the model worked satisfactorily and produced interesting results. The complex and mutually interweaving effects between the systemic variables and the unit-level variables emerged in a clear and significant manner in explaining Italy’s military behaviour over the past half-century. The analysis sheds light on the impact of a change in relative power on Italy’s likelihood of intervening abroad militarily and strongly confirmed the decisive role played by domestic variables in the country’s foreign policy-making process.

Our results support the notion that a middle power such as Italy is responsive to increases or decreases in national strength, but the resulting military policy is highly dependent upon and constrained by domestic considerations that shape the type, direction and pace of the country’s reaction to external stimuli. In particular, the analysis provides sound empirical evidence that Italy is more prone to intervene militarily when it experiences conditions of relative internal stability and elite consensus regarding the need to resort to military means. In the highly fragmented and fragile Italian domestic political context, military assertiveness is deemed a very risky policy to pursue in the absence of support, at a minimum, from the mainstream political forces, which can keep the ‘radical’ and ‘isolationist’ forces in check (Forte and Marrone Citation2012, 20–22). This finding also corroborates many of the qualitative studies on peacekeeping and multilateral peace operations that discuss the reasons for active Italian participation in this field over the past few decades (Ignazi, Giacomello, and Coticchia Citation2012; Tercovich Citation2016; Carati and Locatelli Citation2017).

The second important and original aspect of our article is the attempt to combine Stuart Bremer’s dyads analysis with the study of a single country, thus establishing a theoretical bridge between the quantitative analysis of conflicts and foreign policy analysis. The use of dyads analysis to explain the military behaviour of Italy between 1946 and 2010 proved to be very valuable. For the Italian case, the bivariate analysis showed remarkable consistency between the hypotheses generated by neoclassical realism and the country’s military behaviour. Both the systemic variable (balance of power) and the unit-level variables (domestic and individual) operated according to the model’s expectations and were statistically significant. The hypotheses not verified relates to the extraction capacity variable, for which the analysis has not returned any statistically significant results. Since many other studies highlighted the importance of this variable (Krasner Citation1978; Snyder Citation1991; Christensen Citation1996; Zakaria Citation1998; Taliaferro Citation2006), and given the above-mentioned problem of operationalization, it may be appropriate to consider this evidence not particularly robust.

In shifting from the bivariate to the multivariate analysis, the model showed that some of the bivariate associations were spurious. Of the four variables considered in the multivariate analysis, three (RP, RV and EC) continued to function according to the model’s expectations, while EI was statistically non-significant and with the opposite sign vis-à-vis the bivariate analysis. Without repeating the technical and substantive reasons for these results (see the aforementioned observations), it is clear that more in-depth investigations of the partial inconsistency between the bivariate and multivariate analysis will be necessary.

The analysis conducted here presents both positive and negative aspects. Among the positive is certainly the empirical test of hypotheses derived from neoclassical realism using quantitative techniques and the satisfactory performance of the model in this respect. The study was able to confirm that some of the neoclassical realist propositions are applicable to the case of a middle power such as Italy and, by doing so, to provide a contribution with generalizable findings that existing studies on Italy’s military behaviour have not been able to produce. Among the negative aspects are some limitations that the analysis has highlighted: some may be theoretical, while others may be related to problems in operationalizing the variables or are due to the unavailability of data. Both of these problems can be corrected with further research combining both dyads analysis and single-country studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This timespan was chosen on the basis of the limitation of data regarding militarized disputes after the year 2010.

2 For an introduction to Italian foreign policy after WWII, see Graziano (Citation1968); Bosworth and Romano (Citation1991); Gaja (Citation1995); Ferraris (Citation1996); Varsori (Citation1998); Coralluzzo (Citation2000); Romano (Citation2002); and Mammarella and Cacace (Citation2008).

3 On this point see also Foradori and Rosa (Citation2007, Citation2010) and Ignazi, Giacomello, and Coticchia (Citation2012).

4 See in particular the book edited by Carbone (Citation2011).

5 A notable exception is Brighi’s book which embraces Italian foreign policy from the liberal era to the post-Cold War period.

6 For a different view about the possibility of a neorealist theory of foreign policy, see Elman (Citation1996), and the response by Waltz (Citation1996).

7 Finel (Citation2001/Citation02); Lobell, Ripsman, and Taliaferro (Citation2009); Taliaferro, Ripsman, and Lobell (Citation2012); Ripsman, Taliaferro, and Lobell (Citation2016); Rathbun (Citation2008); Devlen and Özdamar (Citation2009); Kitchen (Citation2010); Toje and Kunz (Citation2012); Schweller (Citation2004, Citation2006); Rosa and Foradori (Citation2017).

8 For a review on the use of quantitative methods in the field of international relations and the associated pros and cons see: Braumoeller and Sartori (Citation2004); Huth and Allee (Citation2004); Mansfield and Pevehouse (Citation2008).

9 This factor has been omitted because it doesn’t change in the period considered (Repubblican Italy), thus it is impossible to measure its weight. For an in-depth analysis of the change of Italy’s strategic culture in the Liberal, Fascist and Republican periods, see Rosa (Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2018).

10 We have introduced some changes to the MID dataset: the crisis in Kosovo, which is dated in 1998 in the dataset, has been placed in 1999 for Italy, as the Italian Government made all of its main decisions in that year: ‘Operation Allied Force’ took place from March 1999 to June 1999. In addition, the Italian participation in ‘Operation Enduring Freedom’ has been added to the year 2001. Oddly, version 4.03 has no entry for Italy for the period 2001–2010. For the period 2001–2010, we have used Italian yearbooks such as Politica in Italia and L’Italia nella politica internazionale, and Ignazi, Giacomello, and Coticchia (Citation2012). The final number for the period 1946–2010 is 36 MIDs.

11 For classical studies on this topic, see Singer (Citation1968), Bremer and Cusack (Citation1995), Vasquez and Henehan (Citation1992), Vasquez (Citation2012), and McLaughlin Mitchell and Vasquez (Citation2014).

12 For the rationale of this formula, see Schweller (Citation1998). This choice is dictated by the fact that – for both the Cold War and post-Cold War period – Italy’s international posture has been strongly affected by perception of its rank compared to other European middle powers (on this point, see Santoro Citation1991; Ferraris Citation1996; Panebianco Citation1997; Coralluzzo Citation2000; Romano Citation2002). Thus, a simple analysis of Italy’s power index is less relevant than an analysis of its change vis-a-vis reference group.

13 The mean value of RP is .1866, and the standard deviation (SD) is .0299.

14 For a slightly different view on this point, see Kaarbo (Citation2012, Citation2015, Citation2017). In her studies, she demonstrates that even coalition cabinets can have an assertive foreign policy. However, her independent variable – coalition cabinet – is not synonymous of government instability (as used in our analysis) and, moreover, her study demonstrates clearly the important delaying effect that coalition politics can have on the foreign-policy making process (Kaarbo Citation2017).

15 The mean value of EI is .8985, and the SD is .2939.

16 In the literature on diversionary war, both inflation rate, unemployment rate and misery index (inflation rate plus unemployment rate) are used alternatively as a proxy for social instability. They present a very high correlation; therefore, they are interchangeable (DeRouen Citation1995; Mclaughlin Mitchell and Prins Citation2014).

17 In the case of RV, we have classified the data by tertiles because the use of standard deviations (above/below the average) is too demanding to single out cases of low vulnerability.

18 The Italian anti-militarist strategic culture is, of course, a strong impediment to the state’s extraction capacity (Rosa Citation2016).

19 On this point, see Thomas Christensen’s analysis of the impact of domestic politics on Sino-American Relations (Christensen Citation1996), and Fareed Zakaria’s explanation of the late rise of America to a world power status (Zakaria Citation1998).

20 We have used the World Value Survey data (several years), Transatlantic Trends data (several years), and Difebarometro data (Archivio disarmo, Roma, several years).

21 The mean value of ExC is −.231, and the SD is .297.

22 The construction of the EC index is mainly based on an analysis of the literature (see note 2). To integrate historical sources, a small group of Italian experts in diplomatic history and Italy’s foreign policy has been consulted. The final index is the result of an analysis by the authors of the different assessments.

23 In the case of EC, we have classified the data by tertiles because of small variability of the index.

24 For the purpose of the statistical analysis, we refrain from referring to the domestic variables using the term ‘intervening variables’, as it is common in the neoclassical realist scholarship. While neoclassical realists refer to this type of variable to indicate a factor that intervenes in the causal path between other variables, altering or mitigating the effect that one has on the other, in statistics the term intervening variable indicates a ‘variable that explains a relation, or provides a causal link, between other variables’ (Vogt and Johnson Citation2015). Following this definition, rather than factors that intervene in the causal process from A to B, intervening variables are factors that are caused by the independent variable and in turn determine a change in the dependent variable. Following the example in the Sage dictionary of statistics and methodology (Vogt and Johnson Citation2015), high income (A) is not directly associated with longevity (B), but rather high income determines access to better health care (C), which in turn increases longevity (B). As none of the domestic factors in this study is determined by the main independent variable RP, referring to them as intervening variables would create confusion. For the purpose of the statistical analysis we decided to refer to the domestic variables simply as independent variables rather than intervening variables given that the meaning associated to this term by the neoclassical realist scholarship is different from the one normally associated to it in statistics.

25 The methodological choice of employing a multilevel regression instead of a standard, single-level regression originates from the structure of the data. When the data are clustered and longitudinal, single-level regression models are not appropriate as they produce inaccurate estimates of the error terms and, consequently, of the significance levels from which the main conclusions are drawn. Multilevel regressions, instead, take into account the clustered structure of the data and the non-independence of the unit-level observations within the clusters, thus producing reliable estimates (a discussion regarding the inner workings of the multilevel regression and the motivations for employing it falls beyond the scope of this paper; for a more detailed discussion see: Gelman and Hill Citation2007; Fox Citation2016; Agresti Citation2019). In this specific case, as it is plausible that the unconditional probability of a MID for some dyads is close to 0 (i.e. Italy vs. Australia) while it is not for some others that are more conflict-prone (i.e. Italy vs. former Yugoslavia), the multilevel logistic regression models have been fit so to allow the intercept to vary by dyad.

26 It is likely that the poor performance of the ExC variable is deeply affected by the different/limited timespan considered. Another problem may be the choice of indicator, which is perhaps not as valid as expected.

27 In the multivariate analysis, the data were rearranged in binary form (0/1), by collapsing the intermediate category. RP above median 1; EI above median 1; RV above median 1; EC above median 1.

28 100[1.87−1] = 87.

29 This is not a very robust result. In Model II, EC produces a more robust statistical significance.

30 For an alternative explanation of this puzzle, see Kaarbo (Citation2012, Citation2015, Citation2017).

31 A technical reason for the contradictory operation of EI is that the bivariate analysis considered all of the variables after recoding into three tiers, that is, ‘High’, ‘Medium’ and ‘Low’, whereas the multivariate analysis considered the same variables after recoding into two tiers: ‘Above median’ and ‘Below median’. The motivation for this choice is that the multivariate analysis, with four variables and three tiers, brought about a standard error so high that no tested ‘variable/tier’ pair was different from zero. To decrease the variability, we were required to recode the variables into two tiers before we could determine a causality relation. It could be the case that EI triggers its effects only when it takes extreme values, but we cannot detect its effects in the multivariate case because we do not have enough data. However, the opposite interpretation is also possible: The effects of EI is not detected because its relation with MID involvement is spurious. The important variables that cause variation in both the likelihood of MID involvement and the value EI are RP, EC and RV. As a consequence, we may observe an impact of EI that disappears when the multivariate analysis is performed.

32 100[Exp(B)−1] = −73.

33 See also John Vasquez’s definition of neorealism (Citation1997, 202): ‘Waltz centers on two empirical questions: (1) explaining what he considers a fundamental law of international politics, the balancing of power, and (2) delineating the differing effects of bipolarity and multipolarity on system stability’.

34 On this point, also Narizny agrees (Citation2017), his hard critique of neoclassical realism notwithstanding.

35 See note 7.

References

- Agresti, A. 2019. An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Bosworth, R. J. B., and S. Romano ( a cura di). 1991. La politica estera italiana, 1860–1985. Bologna: il Mulino.

- Braumoeller, B. F., and A. E. Sartori. 2004. “Empirical-quantitative Approaches to the Study of International Relations.” In Models, Numbers, and Cases: Methods for Studying International Relations, edited by D. F. Sprinz and Y. Wolinsky-Nahmias. Ann Arbor: The Michigan University Press.

- Bremer, S. 1992. “Dangerous Dyads: Conditions Affecting the Likelihood of Interstate War, 1816–1965.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 36 (2): 309–341. doi:10.1177/0022002792036002005.

- Bremer, S. A., and T. Cusack, eds. 1995. The Process of War: Advancing the Scientific Study of War. Luxembourg: Gordon and Breach Publishers.

- Brighi, E. 2013. Foreign Policy, Domestic Politics and International Relations: The Case of Italy. London: Routledge.

- Calise, M., and R. Mannheimer. 1982. Governanti in Italia. Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Carati, A., and A. Locatelli. 2017. “Cui Prodest? Italy’s Questionable Involvement in Multilateral Military Operations Amid Ethical Concerns and National Interest.” International Peacekeeping 24 (1): 86–107. doi:10.1080/13533312.2016.1229127.

- Carbone, M., ed. 2011. Italy in the Post-cold War Order. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Christensen, T. J. 1996. Useful Adversaries: Grand Strategy, Domestic Mobilization, and Sino-American Conflict, 1947–1958. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Cladi, L., and M. Webber. 2011. “Italian Foreign Policy in the Post-cold War Period: A Neoclassical Realist Approach.” European Security 20 (2): 205–219. doi:10.1080/09662839.2011.565052.

- Coralluzzo, V. 2000. La politica estera dell’Italia repubblicana (1946–1992). Milano: Franco Angeli.

- Davidson, J. 2011. America’s Allies and War: Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- DeRouen, K. 1995. “The Indirect Link: Politics, the Economy and the Use of Force.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 39 (4): 671–695. doi:10.1177/0022002795039004004.

- Devlen, B., and O. Özdamar. 2009. “Neoclassical Realism and Foreign Policy Crises.” In Rethinking Realism in International Relations: Between Tradition and Innovation, edited by A. Freyberg-Inan, E. Harrison, and P. James. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Di Nolfo, E. 1977. “Dieci anni di politica estera italiana.” In La politica estera italiana: autonomia, interdipendenza, integrazione e sicurezza, a cura di N. Ronzitti. Milano: Ed. Comunità.

- Di Nolfo, E. 1979. “Sistema internazionale e sistema politico italiano: interazione e compatibilità.” In La crisi italiana, a cura di L. Graziano e S. Tarrow. Torino: Einaudi.

- Dottori, G., and P. Laporta. 1995. “La definizione e la rappresentanza degli interessi nazionali dell’Italia nel nuovo sistema multi-istituzionale di sicurezza europea.” Rivista Militare 68: 111–148.

- Elman, C. 1996. “Horses for Courses: Why not Neorealist Theories of Foreign Policy?” Security Studies 6 (1): 7–53. doi:10.1080/09636419608429297.

- Evans, P., D. Rueshemeyer, and T. Skocpol, eds. 1985. Bringing the State Back in. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ferraris, L. V. ( a cura di). 1996. Manuale della politica estera italiana. Bari-Roma: Laterza.

- Finel, B. I. 2001/02. “Black Box or Pandora’s Box: State Level Variables and Progressivity in Realist Research Programs.” Security Studies 11 (2): 187–227. doi:10.1080/714005331.

- Foradori, P., and P. Rosa. 2007. “Italy: New Ambitions and Old Deficiencies.” In Global Security Governance: Competing Perceptions of Security in the 21st Century, edited by E. Kirchner and J. Sperling. London: Routledge.

- Foradori, P., and P. Rosa. 2010. “Italy: Hard Tests and Soft Responses.” In National Security Culture, edited by E. Kirchner and J. Sperling. London: Routledge.

- Forte, S., and A. Marrone ( a cura di). 2012. “L’Italia e le missioni internazionali.” Documenti IAI 12 (5).

- Fox, J. 2016. Applied Regression Analysis and Generalized Linear Models. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Gaja, R. 1995. L’Italia nel mondo bipolare. Bologna: il Mulino.

- Gelman, A., and J. Hill. 2007. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Gourevitch, P. 1978. “The Second Image Reversed: The International Sources of Domestic Politics.” International Organization 32 (4): 881–912. doi:10.1017/S002081830003201X.

- Graziano, L. 1968. La politica estera italiana nel dopoguerra. Padova: Marsilio.

- Hagan, J. D. 1993. Political Opposition and Foreign Policy in Comparative Perspective. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Hagan, J. D. 1995. “Domestic Political Explanations in the Analysis of Foreign Policy.” In Foreign Policy Analysis, edited by L. Neack, J. Hey, and P. Haney. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- Huth, P., and T. Allee. 2004. “Testing Theories of International Conflict: Questions of Research Design for Statistical Analysis.” In Models, Numbers, and Cases: Methods for Studying International Relations, edited by D. F. Sprinz and Y. Wolinsky-Nahmias. Ann Arbor: The Michigan University Press.

- Ignazi, P., G. Giacomello, and F. Coticchia. 2012. Italian Military Operations Abroad: Just don’t Call it War. London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Johnston, A. I. 1995. “Thinking about Strategic Culture.” International Security 19 (4): 32–64. doi:10.2307/2539119.

- Jones, D. M., S. A. Bremer, and J. D. Singer. 1996. “Militarized Interstate Disputes, 1816–1992: Rationale, Coding Rules, and Empirical Patterns.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 15 (2): 163–213. doi:10.1177/073889429601500203.

- Kaarbo, J. 2012. Coalition Politics and Cabinet Decision Making: A Comparative Analysis of Foreign Policy Choices. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Kaarbo, J. 2015. “A Foreign Policy Analysis Perspective on the Domestic Politics Turn in IR.” International Studies Review 17 (2): 189–216. doi:10.1111/misr.12213.

- Kaarbo, J. 2017. “Coalition Politics, International Norms, and Foreign Policy: Multiparty Decision-making Dynamics in Comparative Perspective.” International Politics 54 (2): 669–682. doi:10.1057/s41311-017-0060-x.

- Kitchen, N. 2010. “Systemic Pressures and Domestic Ideas: A Neoclassical Realist Model of Grand Strategy Formation.” Review of International Studies 36 (1): 117–143. doi:10.1017/S0260210509990532.

- Kitchen, N. 2020. “Neoclassical Realism as a Theory of International Politics.” International Studies Review 36 (1):1–28. doi:10.1093/isr/viaa018.

- Kogan, N. 1963. The Politics of Italian Foreign Policy. New York: Frederick A. Praeger.

- Krasner, S. 1978. Defending the National Interest. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Levy, J. 2011. “The Diversionary Theory of War: A Critique.” In Handbook of War Studies, edited by M. Midlarsky. London: Routledge.

- Lobell, S. E., N. M. Ripsman, and J. W. Taliaferro, eds. 2009. Neoclassical Realism, the State, and Foreign Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mammarella, G., and P. Cacace. 2008. La politica estera dell'Italia: dallo stato unitario ai giorni nostri. Bari-Roma: Laterza.

- Mansfield, E. D., and J. C. Pevehouse. 2008. “Quantitative Approaches.” In The Oxford Handbook of International Relations, edited by C. Reus-Smit and D. Snidal. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mclaughlin Mitchell, S., and B. C. Prins. 2014. “Rivalry and Diversionary Uses of Force.” In Conflict, War, and Peace: An Introduction to Scientific Research, edited by S. Mclaughlin Mitchell and J. A. Vasquez. London: SAGE/CQ Press.

- McLaughlin Mitchell, S., and J. Vasquez, eds. 2014. Conflict, War, and Peace: An Introduction to Scientific Research. London: SAGE/CQ Press.

- Moravcsik, A., and J. Legro. 1999. “Is Anybody Still a Realist?” International Security 24 (2): 5–55. doi:10.1162/016228899560130.

- Narizny, K. 2017. “On Systemic Paradigms and Domestic Politics.” International Security 42 (2): 155–190. doi:10.1162/ISEC_a_00296.

- Newell, J. L. 2011. “Italian Politics After the End of the Cold War: The Continuation of a Two-Level Game.” In Italy in the Post-Cold War Order, edited by M. Carbone. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Panebianco, A. 1982. “Le cause interne del basso profilo.” Politica internazionale X: 15–21.

- Panebianco, A. 1997. Guerrieri democratici. Bologna: il Mulino.

- Pasquino, G. 1974. “Pesi internazionali e contrappesi nazionali.” In Il caso italiano, a cura di F. Cavazza, S. Graubard. Milano: Garzanti.

- Pirani, P. 2008. “‘The Way We Were’: Continuity and Change in Italian Political Culture.” Political Studies Association, http://www.psa.Ac.uk/journals/pdf5/2008/pirani.pdf.

- Rathbun, B. 2008. “A Rose by Any Other Name: Neoclassical Realism as the Logical and Necessary Extentions of Structural Realism.” Security Studies 17 (2): 294–321. doi:10.1080/09636410802098917.

- Ripsman, N. M., J. W. Taliaferro, and S. E. Lobell. 2016. Neoclassical Realist Theory of International Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Romano, S. 2002. Guida alla politica estera italiana. Milano: Rizzoli.

- Rosa, P. 2006. Sociologia politica delle scelte internazionali. Un’analisi comparata delle politiche estere nazionali. Bari-Roma: Laterza.

- Rosa, P. 2014. “The Accommodationist State: Strategic Culture and Italy’s Military Behaviour.” International Relations 28 (1): 88–115. doi:10.1177/0047117813486821.

- Rosa, P. 2016. Strategic Culture and Italy’s Military Behavior. Between Pacifism and Realpolitik. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Rosa, P. 2018. “Pattern of Strategic Culture and the Italian Case.” International Politics 55 (2): 316–333. doi:10.1057/s41311-017-0077-1.

- Rosa, P., and P. Foradori. 2017. “Politics does not Stop at the ‘Nuclear Edge’. Neoclassical Realism and the Making of China’s Military Doctrine.” Italian Political Science Review 47 (3): 359–384.

- Rose, G. 1998. “Neoclassical Realism and Theories of Foreign Policy.” World Politics 51 (1): 144–172. doi:10.1017/S0043887100007814.

- Santoro, C. M. 1991. La politica estera di una media potenza: l’Italia dall’Unità a oggi. Bologna: il Mulino.

- Schweller, R. 1998. Deadly Imbalances: Tripolarity and Hitler’s Strategy of World Conquest. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Schweller, R. 2004. “Unanswered Threats. A Neoclassical Realist Theory of Underbalancing.” International Security 29 (2): 159–201. doi:10.1162/0162288042879913.

- Schweller, R. 2006. Unanswered Threats: Political Constraints on the Balance of Power. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Silvestri, S. 1990. “L’Italia: partner fedele ma di basso profilo.” In La difesa europea: proposte e sfide, a cura di L. Caligaris. Milano: Edizioni di Comunità.

- Singer, J. D., ed. 1968. Quantitative Interational Politics. New York: The Free Press.

- Snyder, J. 1991. Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambitions. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Swidler, A. 1986. “Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies.” American Sociological Review 51 (2): 273–286. doi:10.2307/2095521.

- Taliaferro, J. W. 2006. “State Building for Future Wars: Neoclassical Realism and the Resource-Extractive State.” Security Studies 15 (3): 464–495. doi:10.1080/09636410601028370.

- Taliaferro, J. W., N. M. Ripsman, and S. E. Lobell, eds. 2012. The Challenge of Grand Strategy: The Great Powers and the Broken Balance between the World Wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tercovich, G. 2016. “Italy and UN Peacekeeping: Constant Transformation.” International Peacekeeping 23 (5): 681–701. doi:10.1080/13533312.2016.1235094.

- Toje, A., and B. Kunz, eds. 2012. Neoclassical Realism in European Politics: Bringing Power Back in. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Varsori, A. 1998. L’Italia nelle relazioni internazionali dal 1943 al 1992. Bari-Roma: Laterza.

- Vasquez, J. A. 1997. “The Realist Paradigm and Degenerative versus Progressive Research Programs: An Appraisal of Neotraditional Research on Waltz's Balancing Proposition.” American Political Science Review 91 (4): 899–912. doi:10.2307/2952172.

- Vasquez, J. A., ed. 2012. What do We Know about War? Lanaham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Vasquez, J. A., and M. T. Henehan, eds. 1992. The Scientific Study of Peace and War: A Text Reader. Lanaham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Vogt, W., and R. Johnson. 2015. The SAGE Dictionary of Statistics & Methodology: A Nontechnical Guide for the Social Sciences. 5th ed. Thousands Oaks: SAGE publications.

- Walston, J. 2011. “Italy as a Foreign Policy Actor: The Interplay of Domestic and International Factors.” In Italy in the Post-Cold War Order, edited by M. Carbone. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Waltz, K. 1979. Theory of International Politics. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- Waltz, K. 1996. “International Politics is not Foreign Policy.” Security Studies 6 (1): 54–57. doi:10.1080/09636419608429298.

- Zakaria, F. 1998. From Wealth to Power. The Unusual Origins of America's World Role. Princeton: Princeton University Press.