ABSTRACT

Population ageing, and the decline in the working-age population, represent a profound global demographic shift. What political consequences do ageing populations have for the economies of advanced democracies? To address this question, we carry out a wide-ranging, systematic literature review using network-based community detection algorithms and manual coding to select almost 150 articles. We find that research in this area typically focuses on a few mechanisms and is therefore – by design – unable to identify gaps in existing knowledge or assess interactions between different strands of literature. Our review suggests that ageing has important implications for a variety of domains including electoral behaviour, social policy preferences, and public spending. Taken together, the political consequences of population ageing are likely to have previously overlooked and indirect impacts on economic outcomes. Future research should, therefore, examine how population ageing shapes political dynamics and policy choices in ways that also affect the economy.

Introduction

What are the political consequences of ageing on western countries’ economies? This question is important for three reasons. First, most of the world is ageing (Harper Citation2014). Nearly 20% of the EU’s population was 65 years old or more in 2018Footnote1 and the share of elderly is forecasted to reach nearly 30% in the EU by 2050 (European Commission Citation2014, 410). Second, ageing has widespread fiscal, political, and economic implications: the share of those working falls, just as demands on pensions, health, and social care increase. Third, analysing the process of ageing represents an opportunity to explore how changes in the composition of electorates influence broader political and economic dynamics. Indeed, the distinctive socio-economic position of the elderly is likely to give them distinct political preferences and behaviours.

While there is a large literature on the consequences of ageing, the topic has tended to be studied from disparate and distinct methodological and substantive angles depending on the discipline. Political scientists have analysed the implications of ageing for participation in elections (e.g. Bhatti and Hansen Citation2012; Blais et al. Citation2004), party choices (e.g. Tilley Citation2002), or preferences for public spending (e.g. Busemeyer, Goerres, and Weschle Citation2009; Lynch and Myrskylä Citation2009). Others have examined the pressures that ageing puts on the budgets for pension, education, and healthcare spending (Breyer, Costa-Font, and Felder Citation2010; Hicks and Zorn Citation2005; Tepe and Vanhuysse Citation2009). Largely separate from the aforementioned studies is a vast body of economic research investigating the consequences of demographic change for asset and house prices, productivity and growth, as well as savings and consumption behaviour (Acemoglu and Restrepo Citation2017; Cutler et al. Citation1990; Feyrer Citation2007; Hansen Citation1939; Mahlberg et al. Citation2013; Poterba Citation2001; Summers Citation2015; Takáts Citation2012).

Within this wide range of topics, most scholarship tends to focus on one or two specific outcomes and mechanisms. What is therefore missing is a more integrated account that brings together the findings of disparate studies to examine the strength of the evidence for particular conclusions, point out gaps and unappreciated connections for future research to address. A wide-ranging and interdisciplinary perspective is especially relevant because ageing can affect outcomes of interest through multiple political and economic channels that can mutually reinforce – or undermine – one another.

This article seeks to fill this gap by systematically reviewing research on the political implications of ageing for the economies of Western countries. Our search strategy deliberately starts by casting a wide net capturing tens of thousands of papers but we then employ a variety of quantitative and qualitative tools to refine and further restrict our search results. This allows us to select nearly 150 papers, capturing different strands of the literature, which we then analyse in greater detail.

Our findings suggest widespread political consequences of ageing. Older people are distinctive in terms of their policy preferences, in particular their low levels of support for education spending, and their political behaviour, especially their higher electoral turnout. Population ageing appears to be associated with reduced education spending and increased healthcare spending, both within and between countries. However, the effects of ageing on pension spending are less clear: while population ageing does seem to be associated with greater pension spending overall, individual pension entitlements appear to be less generous when demand is greater.

Our review also illustrates some gaps in – and previously unidentified implications of – existing research. For example, more research needs to explore the intermediate steps between population ageing and policy outcomes, such as the ways in which population ageing shapes the positions that political parties take on social and economic policy. Furthermore, we will argue that the political consequences of population ageing may have important and understudied impacts on economic outcomes. For example, the elderly may push for spending on pensions or social care, at the expense of investments in human capital that promote long-term growth or of spending on active labour market policies to address unemployment problems. Population ageing may also shape a range of other economic outcomes: examples include the role of pensions as an automatic stabiliser reducing macroeconomic volatility, and the consequences of the elderly’s policy preferences in domains ranging from immigration to taxation.

Population ageing could also affect economic policy through retrospective economic voting. The elderly might for example be more sensitive to high inflation (Bojar and Vlandas Citation2021; Vlandas Citation2018) than to low growth, and as a result population ageing can enhance or limit important feedback loops incentivising governments to pursue different economic objectives. In extreme cases, ageing could limit politicians’ incentives to pursue economic growth since the median voter might no longer be in a position to effectively sanction economically inefficient governments (see Iversen and Soskice Citation2019).

The rest of this paper unfolds as follows. The next section presents our research design and discusses our approach to searching, identifying and summarising relevant journal articles from different disciplines in the social sciences. We then structure our review in three sections: the first examines age differences in political behaviour; the second differences in policy preferences; while the third focuses on the impact of ageing on public spending. Next, we identify some gaps in existing literature, in particular the potential for population ageing to affect economic outcomes through political channels.The last section concludes.

Research design and search strategy

As is commonly recommended when conducting systematic reviews (Sundberg and Taylor-Gooby Citation2013), we carried out our searches using two databases: the ProQuest International Bibliography for the Social Sciences (IBSS) and Web of Science (WoS). The IBSS database covers over 2800 journalsFootnote2 and contains over 3 millionFootnote3 records covering economics, political science and sociology, amongst other disciplines. The WoS database contains 159 million recordsFootnote4 covering various disciplines.

For both databases, we restricted the search results in two ways. First, we focused on outputs published between 2000 and 2019. This helped limit the number of results, and allows our analysis to complement that of older reviews drawing on research from the 1980s and 1990s (Taylor-Gooby Citation2002; Uhlenberg Citation1992). Second, we only include journals in the social sciences, specifically: economics, public administration, political science, social policy and sociology. This reduces the volume of search results substantiallyFootnote5 and is more likely to produce results that address the debate on the economic and political consequences of ageing. In order to implement this disciplinary restriction, we extract a list of all journals from Scimago in the following categories: Economics and Econometrics, Political Science and International Relations, Public Administration, Sociology and Political Science. After manually eliminating those that were clearly irrelevant, we were left with 791 journals. We combined journals and keywords restriction to identify a first sample of articles.

Given the large sample size of papers that both databases returned (between 13,000 and 21,000 depending on the precise search terms), we had to adopt a quantitative way of classifying articles into relevant and non-relevant groups. We used network-based community detection algorithms to identify clusters of articles based on common citation patterns (Blondel et al. Citation2008; Raghavan, Albert, and Kumara Citation2007). By coding a random subsample of results as relevant based on their abstracts, alongside relevant articles generated using subject matter knowledge, we identified clusters of results containing many relevant papers. We iteratively refined our keywords and search strategy to minimise the risk of missing out on important articles while also ensuring the final numbers of articles to be reviewed was manageable. The search strategy, including details on search terms, clustering algorithms and the process of iterative refinement is described in more detail in section A1 in appendix. This process yielded a more manageable number of articles – circa 4300 articles.

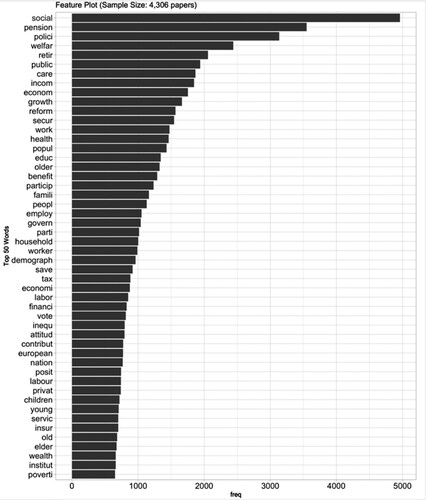

plots the frequency of the 50 most common words included in the title or abstract of papers in our final sample after common pre-cleaning steps have been conducted (e.g. removal of punctuation; numbers and stop words; transformation to lower cases; stemming). The figure illustrates that the community-detection algorithms successfully identify clusters of papers relevant to the study of population ageing and the economy. For instance, pension and retirement related terms such as ‘pension', ‘retir', ‘older' and ‘demograph' rank among the top 50 terms. In addition, terms referring to various welfare state domains (‘health', ‘care', ‘employ', ‘family', ‘educ' and ‘children') were also common, as were words denoting political processes (such as ‘reform', ‘particip', ‘vote', ‘attitud', and ‘govern'). This suggests that our results cover economic, political, and policy-related subfields of ageing research.

Figure 1. Frequency plot of 50 most frequent terms appearing in title or abstract in the final sample of research articles.

Note: The plot shows the number of occurrence of the 50 most frequent terms appearing in the abstract or title in the final samples after common pre-cleaning steps (removal of punctuation, numbers and stop words; transformation to lower cases; stemming). N = 4306 papers.

We then manually screened these papers based on their titles and abstracts. Only those articles that presented original empirical research covering OECD countries using data from 1990 or later were coded as relevant at this stage. Our coding schema can be found in table A2. This process identified 143 journal articles which were then reviewed in depth. In reporting the findings of our review, we choose to focus on research that improves our understanding of the political consequences of population ageing, including for citizen policy preferences, political behaviour, and policy outcomes. As a result, we pay less attention to research which looks at the direct effects of population ageing on economic outcomes including economic growth and productivity, savings and investment behaviour, and housing and financial markets. These areas have been covered by existing reviews (e.g. Banks Citation2006; Harper Citation2014; Hassan, Salim, and Bloch Citation2011; Martín, del Amo Gonzalez, and Cano Garcia Citation2011), whereas our focus on the political consequences of ageing on the economy has not (to our knowledge) been addressed by a wide-ranging review using a systematic search protocol.

Previous reviews have focused mainly on the pension system (de Walque Citation2005; Nishiyama and Smetters Citation2014; Taylor-Gooby Citation2002) or on formal theory rather than empirical findings (Casamatta and Batté Citation2016). Our aim here is not to review every single empirical study of a particular dependent variable, which would require reviewing hundreds of articles on each outcome. Instead, we first map out the different types of effects ageing can have on political phenomena.Footnote6 We then set out the wider implications of the literature we have reviewed, showing how the political consequences of population ageing might have important, and underappreciated economic consequences.

Grey power and politics

This section begins by reviewing the literature on age differences in political behaviour, before moving on to consider policy preferences, and finally policy outputs such as pension and health care spending.

The political behaviour of the elderly

We start by reviewing the literature on the association between age and party choice, voting behaviour and other forms of political behaviour. Population ageing could in principle be associated with changing party choice for three reasons. First, older people may become more likely to support certain parties – an ‘age effect’. Thus for instance, Tilley (Citation2002) as well as Tilley and Evans (Citation2014) find that life-cycle effects are important influences on party choice – with older people becoming more likely to vote Conservative.Footnote7 This is complemented by Dassonneville’s (Citation2013) finding that party choice becomes less volatile with age and Dassonneville, Hooghe, and Vanhoutte (Citation2012) showing that party identification becomes more likely with age. Second, a large cohort of older people like the baby boomers might have been socialised in a specific way, which in turn shapes their views, attitudes, and hence ultimately their party choice – a ‘cohort effect’ (Grasso et al. Citation2019a; Tilley Citation2002). Third, population ageing might shape aspects of political context that then affect party choice – a ‘period effect’.

With respect to party choice, ageing seems to be associated with voters being increasingly conservative and less volatile. This latter result seems hard to reconcile with aggregate trends of increasing electoral volatility and decreasing party identification, although it is possible that the greater stability of the elderly is more than overtaken by much greater volatility for the rest of the population. The ways in which population ageing might shape political context (e.g. party strategies or positioning, macroeconomic environment) in ways that might benefit or hurt support for certain parties does not seem to be considered in this literature.

A large number of studies consider the relationship between age and voting in general. While some articles frame their analyses as explaining generational differences in turnout patterns, using data from only one time point (Furlong and Cartmel Citation2012; Wass Citation2007) complicates empirical distinctions between age, cohort, and period effects.Footnote8 Berry (Citation2014) focuses directly on population ageing to argue that a combination of the greater numbers, higher registration and turnout of older citizens in the UK is likely to lead to substantial decline in political influence among the young. Age differences in turnout are very consistent across studies, increasing with age, but declining among the oldest age groups (or put differently, having a positive linear term and a negative quadratic term).Footnote9 These patterns can also be observed in studies based on high quality register data from Finland (Martikainen, Martikainen, and Wass Citation2005) and Geneva (Tawfik, Sciarini, and Horber Citation2012). There is also evidence that age differences vary by type of election, for instance in Switzerland (Tawfik, Sciarini, and Horber Citation2012) and the US (Kogan, Lavertu, and Peskowitz Citation2018).

Focusing on electoral registration rather than voting, Ansolabehere, Hersh, and Shepsle (Citation2012) argues that lower levels of registration among the young are essentially a mechanical consequence of registration being voluntary and a function of geographical location. Gimpel, Morris, and Armstrong (Citation2004) confirm the importance of residential location and mobility by showing that age gaps in turnout between US counties are largest in areas where the population is increasing, implying substantial in-migration. Overall, the evidence therefore conclusively shows that older people are more likely to vote, thereby increasing the electoral influence of large cohorts as they pass into middle age and then retirement.

If older people are more likely to vote, then one might assume that population ageing is associated with higher turnout. Puzzlingly, population ageing actually coexists with well-known decline in voting in almost all rich democracies. Another strand of literature in our results uses repeated cross-sectional survey data to explain falling turnout. Blais et al. (Citation2004), Lyons and Alexander (Citation2000), Smets and Neundorf (Citation2014), and Persson, Wass, and Oscarsson (Citation2013) report results from single country studies (US, Canada, Sweden), while Gallego (Citation2009) looks at three countries (Norway, Germany, Sweden), and Bhatti and Hansen (Citation2012) analyse European Parliament elections.

These studies find two consistent patterns. First, age has a U-shaped relationship with turnout, where middle aged and newly retired cohorts having especially high turnout. Second, baby boomer cohorts tend to have substantially higher turnout than younger cohorts. Thus, neither the increasing average age of the population, nor the large size of the baby boomer cohort can explain turnout decline – indeed ceteris paribus the opposite should be true. As a result, we can rule out population ageing as a direct cause of turnout decline. It is however possible that population ageing could indirectly lead to turnout decline if political parties systematically focus on the preferences of older generations to the exclusion of issues relevant to the young, hence driving a sense of political disengagement and alienation amongst these groups (Furlong and Cartmel Citation2012).

The policy preferences of the elderly

In the next paragraphs, we review the literature on the elderly’s welfare state preferences. We start with redistribution preferences, and then discuss the findings on preferences for pension benefits, which have attracted most of the attention in the existing literature. We then turn to research on education and health care preferences.

While age commonly appears as a control in the large literature on redistribution preferences (Alesina and La Ferrara Citation2005; Ansell Citation2014; Corneo and Gruner Citation2002; Rueda and Stegmueller Citation2016), it is rarely the focus of studies and there are therefore relatively few articles on this topic appearing in our search results. In the UK, which has been the focus of many studies considering the impact of ageing on political dynamics, older people appear less supportive of redistribution and welfare spending net of generational differences. However, the evidence suggests that age effects are substantially smaller than generational differences (Grasso et al. Citation2019a).

An interesting contrast is observed in another liberal market economy (Hall and Soskice Citation2001), the US, where Lin, Kamo, and Slack (Citation2018) find that older people are also less supportive of redistribution, but cohort effects can be explained away by controls.Footnote10 In a study drawing on cross-national surveys of European countries those aged 46+ in 2004–2005 (born before 1958) are generally more supportive of redistribution, especially if they are not property owners (André and Dewilde Citation2016). This finding is broadly consistent with that of Grasso et al. (Citation2019a) who emphasise that young people in Britain are less supportive of redistribution relative to ‘Wilson’s/Callaghan’s children’ – i.e. those born 1945–1958.

The most obvious place to start when thinking about effect of age on preferences for policies is pensions, since these policies have the greatest and most direct effect on the living standards of the elderly. A large literature explores this question with mixed findings. For instance, using cross-national data Lynch and Myrskylä (Citation2009) find no evidence that those deriving more income from pensions are less supportive of pension reform. By contrast, Fernández and Jaime-Castillo (Citation2013) find that older people are more opposed to decreasing pension generosity, and want those still working to work longer. Busemeyer, Goerres, and Weschle (Citation2009) suggest that the age cleavage in pension support is very heterogeneous across countries, though pensions are always more favoured by the old. These age cleavages are partially – but not entirely – confounded by cohort differences (Sørensen Citation2013). Studies which use data from a single country tend to find more consistent results. Older people are generally more supportive of social security spending increases in the US (Quadagno and Pederson Citation2012), Finland (Muuri Citation2010), spending on the old in Sweden (Svallfors Citation2008) and on elderly care in Norway (Rattsø and Sørensen Citation2010).

Age differences in support for pensions do not necessarily imply the existence of intergenerational conflict. Indeed spending on the old is popular relative to spending on childcare across all age groups in Sweden (Svallfors Citation2008) and Norway (Rattsø and Sørensen Citation2010). Some US studies also contest that there are significant intergenerational conflicts over pensions. Several authors argue that younger people are as supportive (Fullerton and Dixon Citation2010) or even more supportive (Grafstein Citation2009; Silverstein et al. Citation2000; Street and Cossman Citation2006) of social security spending than the elderly or middle aged, or that other cleavages such as race are more relevant (Hamil-Luker Citation2001).

In addition, there are age differences in other aspects of pension attitudes: in Finland, elderly people are more critical of social welfare services (Muuri Citation2010), and likely to perceive injustice in the pension system in Germany and Israel (Sabbagh and Vanhuysse Citation2014).Footnote11 However, they are also more likely to feel an obligation to pay for pensions (van Oorschot Citation2002). This suggests a general pattern where the elderly are more invested in the pension system. They therefore support higher spending but are also more critical of perceived problems.

Surprisingly, our sample of articles provides no evidence that the generosity of pensions systems either in terms of individual income or at aggregate level shapes support for pension spending or pension reform. Thus overall, while there is some support for the argument that elderly are more supportive of pensions than other age groups, it does not automatically follow that there are intergenerational conflicts, perhaps because younger people have an interest in supporting generous future pension entitlements (Prinzen Citation2015). This raises the question of whether pensions are the right place to look for age-based self-interest in attitudes. Another unexplored question stems from the fact that none of the articles reviewed seeks to understand how support for pension spending translates into age differences in party choices or differences in party manifestos regarding pension spending.

While young people have an interest in generous pension entitlements in the future, older people, who have passed the age at which they are likely to have school-aged children, have very little incentive to support spending on education. Many studies on age differences in support for education spending ask how support varies across contexts and compared with other policy areas as well as the extent to which age differences are driven by self-interest considerations. Overall, there is evidence that, across 12 OECD countries, the elderly generally exhibit lower support for education (Busemeyer, Goerres, and Weschle Citation2009). The age cleavage is substantively and statistically significant since it is larger than the income cleavage in most countries. It is also a larger cleavage than for many other kinds of public spending, although there is substantial cross-national heterogeneity in cleavage size (Busemeyer, Goerres, and Weschle Citation2009).

However, the size of the demographic cleavage tends to be reduced when adjusting for cohort and period effects, although authors disagree on the extent to which cohort effects are entirely responsible for the observed differences. Sørensen (Citation2013) argues that in a cross-national context older people are less supportive of education spending even after adjustment for cohort effects. Focusing on the US, Fullerton and Dixon (Citation2010) come to the opposite conclusion – namely, that older people are more supportive of education spending after adjusting for cohort effects. In a similar vein, Street and Cossman (Citation2006) and Plutzer and Berkman (Citation2005) contend that cohort replacement in the US is leading the elderly to become increasingly more supportive of education spending.

Older people’s support for childcare varies based on ‘inter-generational solidarity’ e.g. contact with grandchildren (Goerres and Tepe Citation2010), but young people’s support for elderly care does not exhibit similar dynamics (Rattsø and Sørensen Citation2010). Nonetheless, there exists evidence in many contexts that the elderly are less willing than the young to support increased education spending. Thus for instance, in Switzerland older people are less keen on expanding education spending as well as less willing to pay taxes to do so, and tend to prioritise instead health and social security spending over education spending (Cattaneo and Wolter Citation2009). In Norway, older people are more supportive of spending on care for elderly and less supportive of childcare and school spending (Pettersen Citation2001; Rattsø and Sørensen Citation2010). In the US, older white people are less likely to support education spending (Tedin, Matland, and Weiher Citation2001) especially at state level and when the share of children from minority backgrounds is higher (Brunner and Balsdon Citation2004). However, there are also findings contradicting these results, for instance by Street and Cossman (Citation2006) who show that in the US elderly individuals are more supportive of education than social security.

Overall, the main conclusion from these studies is that older people are less supportive of education spending. As in the case of support for pension spending, this literature leaves partly unanswered whether this effect is mostly because of life-cycle driven self-interest or cohort differences, but in some ways this distinction does not change the likely consequences of this preference distribution since the numerical size of ageing cohorts is increasing over time. Similarly, existing studies which try to untangle self-interest and social affinity find some support for both, in particular for affinity through social contact (Goerres and Tepe Citation2010; Rattsø and Sørensen Citation2010) and ethnic identity (Brunner and Balsdon Citation2004). While recognising the presence of alternate perspectives (e.g. Street and Cossman Citation2006), moderating variables, and cross-national variations, the literature generally points in a direction consistent with age-based self-interest: the elderly are more supportive of pension spending and less supportive of education spending.

The policy implications of ageing

What is the effect of ageing on public spending? The studies captured in our sample provide some, albeit mixed, support for the idea that the increased number, and hence political influence, of the elderly leads to an increase in public spending. In two separate articles, Tepe and Vanhuysse (Citation2009, Citation2010) use OECD panel data and find evidence that pension spending is greater when the old age dependency ratio is higher.Footnote12 Shelton (Citation2008) finds a similar relationship for overall welfare spending, while Breyer, Costa-Font, and Felder (Citation2010) show that healthcare spending is higher when longevity is greater, although the magnitude of the effect is very small.

By contrast, Tepe and Vanhuysse (Citation2009) find that the generosity of pensions is actually lower when the dependency ratio is higher, suggesting that higher spending is driven by higher need, and possibly by past entitlements, rather than a ‘grey power’ hypothesis. Rattsø and Sørensen (Citation2010) similarly find that spending per person on elder care is lower when there are more elderly people. As a result, increasing pension spending seems more likely to be a mechanical consequence of an increasing number of people with pension entitlements than the elderly distorting the political process to allocate more resources to increase pension generosity.

On the other hand, there is no evidence that ageing populations lead to welfare retrenchment. Hicks and Zorn (Citation2005) claimed that this was the case, however a later errata suggests their findings were an artefact of data errors (‘Errata’ Citation2007). Qualitative comparative analyses suggest that the policy response to population ageing varies systematically across welfare regimes, potentially reinforcing historical institutional trajectories (Anderson Citation2015). Indeed, Kim and Lee (Citation2008) argue that the response to population ageing in pension and labour market policy varies substantially by welfare state, and that some countries with high dependency ratios maintain high support for the income security of older individuals. Aysan and Beaujot (Citation2009) argue that liberal and south European welfare regimes aim at recommodification, whereas social democratic regimes aim at cost containment. Overall, we note that few studies look at the generosity of benefits, which are at least as relevant to the grey power hypothesis as levels of overall spending, and more relevant to the living standards of older people.

With respect to education spending, results generally indicate that higher elderly populations, or higher spending on the elderly are associated with reduced spending on the young. This finding is well established in the US where Harris, Evans, and Schwab (Citation2001) for instance show that states, and to a lesser extent school districts, with greater elderly populations spend less on education. Ladd and Murray (Citation2001) find no relationship at the level of counties, although this is perhaps less relevant given that education spending actually takes place on the scale of school districts (and to some extent states). Krieger and Ruhose (Citation2013) find similar evidence on a cross-national scale. Bonoli and Reber (Citation2010) using a panel of OECD countries, and Rattsø and Sørensen (Citation2010) using Norwegian local data, both find evidence of crowding out: higher spending on elderly is associated with lower support for spending on childcare and schooling. Baek, Ryu, and Lee (Citation2017) argue that such trade-offs between family and old age spending are more likely when family policies are less mature and entrenched. One potential complication when attempting to extrapolate from such analyses is that if an increase in the elderly population is associated with a decline in the child population rather than a decline in the working age adult population, a decrease in overall spending is still compatible with constant, or even increasing spending per child (Kurban, Gallagher, and Persky Citation2015).

Some evidence that political mechanisms play an important role (at least in the US) comes from Kogan, Lavertu, and Peskowitz (Citation2018). They study how the timing of referenda to raise funding for schools affects the composition of the electorate who turn out, and the chances of funding measures successfully passing.Footnote13 They find that referenda that are held off the main electoral cycle have more elderly electorates and are less likely to pass. However, the latter effect is not observed in Texas, where the elderly are exempted from rises in local property taxes – suggesting that part of elderly opposition to school funding is mitigated when they can benefit from local uplifts in property values without paying taxes.

The role of political ‘second order’ mechanisms, and especially the potentially offsetting effect where the elderly benefit from increased local education spending through an increase in the property prices, deserves further attention. In particular, it is difficult to make sense of these results in a comparative perspective: the age cleavage in support for education is actually highest in countries like the USA, Australia, and Canada (Busemeyer, Goerres, and Weschle Citation2009) which have decentralised education systems.

Finally, the articles we have reviewed suggest a broad consensus that population ageing is associated with greater healthcare spending (though some conflicting evidence is presented in Martín, del Amo Gonzalez, and Cano Garcia Citation2011). This is the case for OECD countries (Breyer, Costa-Font, and Felder Citation2010; Noy Citation2011), over time in the USA and Switzerland (Colombier Citation2018; Karatzas Citation2000), and at the regional level in Japan (Tamakoshi and Hamori Citation2015). However, there are shortcomings in the evidence for this claim in the cross-national literature: Breyer, Costa-Font, and Felder (Citation2010) focus on life expectancy rather than population ageing – which may exhibit different trends if increases in life expectancy are driven by mortality decreases at younger ages. Noy (Citation2011) finds that the association between ageing and expenditure is reduced by controls for trade openness and foreign direct investment – suggesting confounding effects by other features of the economy associated with population ageing. This literature is quite different in approach from research on other kinds of spending. With the exception of Noy’s article, it does not integrate the study of healthcare spending with other social policy areas and does not include the political and institutional covariates seen in research on overall spending or education spending.

Bringing politics back into the study of ageing and the economy

In this section, we bring together the disparate strands of literature we have reviewed and illustrate some of their broader implications. In particular, we argue that the political consequences of population ageing may have important and understudied indirect effects on economic outcomes. These political paths are rarely considered by research in economics, which tends to focus on the direct economic consequences of demographic change.

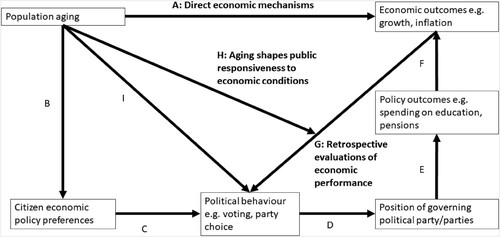

presents a conceptual framework illustrating a variety of possible causal pathways from population ageing to economic outcomes, operating through distinct mechanisms. We distinguish between direct economic mechanisms (path A) and a variety of political mechanisms that can have effects on economic outcomes. The studies we reviewed provide strong evidence for some pathways, while the evidence for other pathways should be explored in future research. We discuss each of these causal pathways in turn, both to systematise the findings of our review, and also to illuminate the potential economic consequences of population ageing that take place through political mechanisms.

To simplify the discussion, we focus in particular on how population ageing shapes support for education spending, and its’ downstream consequences for economic growth, as this is one of the best evidenced areas in our review, though we also briefly discuss other examples.

While not the focus of this review, our search results revealed a great deal of research that seeks to understand the impacts of population ageing on economic outcomes through direct economic mechanisms (path A). In particular, we found research that seeks to understand the economic impacts of population ageing on asset and house prices (Eichholtz and Lindenthal Citation2014; Poterba Citation2001; Quayes and Jamal Citation2016; Takáts Citation2012), productivity (Feyrer Citation2007; Mahlberg et al. Citation2013), and savings and consumption behaviour (Demery and Duck Citation2006; Horioka Citation2010; Lim and Zeng Citation2016). These studies often focus on economic mechanisms, especially the implications of the Permanent Income Hypothesis: that individuals will save and purchase economic assets while working so that they can maintain a constant level of consumption after they retire. In turn, the combined effect of these dynamics on economic growth have been debated (Acemoglu and Restrepo Citation2017; Cutler et al. Citation1990; Gordon Citation2016; Hansen Citation1939; Summers Citation2015). On the one hand, many have argued that secular stagnation in the form of declining growth rates in developed countries can be partly explained by population ageing, for instance because of its effect on savings, investment and lower productivity and innovation. On the other hand, some have argued that ageing leads to automation, which in turn spurs economic growth.

Turning now to the topics covered by our review, we found many studies of the relationship between ageing and policy preferences, denoted in by path B. For instance, we found evidence for the claim that the elderly are less supportive of spending on education than younger people (Busemeyer, Goerres, and Weschle Citation2009; Sørensen Citation2013). These findings are more mixed in the US (Plutzer and Berkman Citation2005; Street and Cossman Citation2006), while in other countries this association can be moderated by social contact with the young (Goerres and Tepe Citation2010; Rattsø and Sørensen Citation2010). Assuming that these findings hold at an aggregate as well as an individual level, population ageing appears to be associated with lower support for spending on education.

The total impact of population ageing on the position of governing political coalitions comes through two distinct paths. In the first path, population ageing shapes policy preferences (path B), which influence party choice (path C), and hence the position of governing parties (path D).Footnote14 In the second path, population ageing directly affects the composition of the electorate through age differences in turnout (path I), and hence the composition of the government (path D). One of the most consistent findings from this review is that turnout peaks among the middle aged and retired (Bhatti and Hansen Citation2012; Blais et al. Citation2004; Tawfik, Sciarini, and Horber Citation2012), thus exacerbating the electoral impact of large cohorts of older people. Paths D and E are especially neglected in the literature we review. Path D is the responsiveness of governing party positions to the vote choice of the electorate. Path E is the extent to which governing parties are able to turn their positions into policy outcomes without, for example, intervention from veto players such as the judiciary or policy failure due to a lack of administrative capacity.Footnote15

Path D is important because previous studies have shown that political parties react strongly to preferences of their electorates. As electorates age, the relative weight of elderly voters increase relatively to the young. If party positions simply reflect the preferences of the median voter (e.g. Conesa and Krueger Citation1999; Galasso and Profeta Citation2007) then age differences in preferences and vote choices will be translated directly into policy positions. In this case, population ageing will lead parties to pay greater attention to the interests and preferences of older voters. However, if older people have strong and long-lasting attachments to certain parties, (e.g. Butler and Stokes Citation1983; Goerres Citation2009) such as conservative parties, that are partly independent of their policy platforms, then such parties will retain strategic room to prioritise policies that are unpopular with elderly voters without necessarily being punished electorally.

Other theories of policy responsiveness hold that the government ‘stays closely attuned to the ebb and flow of public opinion and adjust policy accordingly' when in power (Wlezien and Soroka Citation2007, 805) and adjusts policy positions accordingly in order to avoid protests or future electoral penalties (Brooks and Manza Citation2006; Hollibaugh, Rothenberg, and Rulison Citation2013). If older people are more interested in politics, more knowledgeable about how proposed policies affect their own interests, or more likely to participate in politics through non-electoral means (Grasso et al. Citation2019b), then governments may be more responsive to their preferences than to other segments of the electorate. Thus, future research should investigate the extent to which party positions and policy outcomes disproportionately reflect the preferences of elderly voters, building on the large body of work on differential responsiveness by income and gender (Erikson Citation2015; Gilens and Page Citation2014; Weber Citation2020).

Researchers should also aim to strengthen the evidence for gaps in the causal chain between population ageing and policy or economic outcomes. An example of how to do this can be seen in the case of population ageing and inflation (for economic research on this topic see Andrews et al. Citation2018; Gajewski Citation2015). Older people are expected to be more concerned than the young by inflation because they derive income from savings or other financial assets rather than labour income. For instance, Vlandas (Citation2018) not only finds that the share of the population aged 65 and over is associated with lower inflation, but also brings a variety of additional empirical evidence into play. He shows that older people are not only more inflation averse and punish incumbents for high inflation, but also that population ageing affects the extent of economic orthodoxy of party manifestos and central bank independence. In doing so, he provides evidence for multiple steps of the causal chain from voter preferences to policy outputs, instead of assuming policy responsiveness to the preferences of the median voter.

However, despite some important gaps, taken together the literature we reviewed provides strong evidence that population ageing affects economic outcomes through political channels. For example, population ageing reduces popular support for education spending, which appears to be translated into spending by a disproportionately elderly electorate. Levels of education spending have substantial effects on economic outcomes (path F). Not only is human capital seen as a major determinant of long-term growth by many economists (e.g. Barro Citation2001; Temple Citation1999), but it is likely to have an especially important role in ageing societies. Growth in middle aged and older cohorts is associated with increased economic growth when levels of tertiary education is high (Ang and Madsen Citation2015; Castelló-Climent Citation2019; Marconi Citation2018), perhaps because highly educated workers in knowledge economy occupations are productive for longer than less educated workers. The articles we reviewed thus suggest that population ageing can undermine long-term growth by reducing public spending on education.

Other examples include investment in younger generations in the form of social investment policies (Hemerijck Citation2018; Morel, Palier, and Palme Citation2011) or spending on retraining and active labour market policies (e.g. Vlandas Citation2013) which are crucial to address unemployment among lower skilled workers. While these examples concern economic change over the long-run, pension spending might also have an impact on short run economic volatility. Population ageing has economic consequences partly because it is associated with increased spending on pensions, which can crowd out other spending priorities or limit the political capital to introduce liberalisation reforms (e.g. Simoni and Vlandas Citation2021). However, public pension spending may also act as an automatic stabiliser that limits the extent to which negative economic shocks translate into higher output gap. Public pension provision may enable individuals to select into early retirement during recessions, thereby reducing labour market pressure and increasing counter-cyclical spending, in contrast to pro-cyclical defined contribution private pension schemes (Darby and Mélitz Citation2008; Ghilarducci, Saad-lessler, and Fisher Citation2012). The economic consequences of population ageing could run through preferences for taxation in addition to preferences towards spending. Indeed, the higher support for conservative parties among the elderly suggests that they are likely to be opposed to higher taxation. However, some evidence suggests that older people support both higher and more progressive income taxation (Barnes Citation2015; Hennighausen and Heinemann Citation2015). Their attitudes towards wealth taxes are less well understood, but are likely to be more negative, given this groups’ reliance on income from assets and property rather than labour (c.f. Ansell Citation2019).

There may even be indirect effects of ageing on the economy that operate through fairly distant policy domains such as immigration policy. The elderly have been found to hold more anti-immigration attitudes (Caughey, O’Grady, and Warshaw Citation2019; Hainmueller and Hiscox Citation2007) and more likely to vote for far right parties (e.g. Halikiopoulou and Vlandas Citation2020) which may lead to popular support for restrictions on immigration that limit labour supply. On the other hand, retired people may worry less about direct labour market competition with immigrants and hence may support immigration when it benefits them, for instance by providing labour to compensate for shortages of careers for the elderly. In sum, ageing can shape economic outcomes not just through demographic and economic mechanisms, but through a variety of political ones as well.

Moreover, there is another pathway through which population ageing can affect political outcomes that has been largely neglected by the literature we reviewed. It is well known in political science that voters retrospectively evaluate governments by their economic performance (path G), punishing incumbents for poor economic performance by voting for other parties (Erikson, MacKuen, and Stimson Citation2000; Norpoth Citation1996; Stegmaier and Lewis-Beck Citation2013). However, the impact of economic outcomes on party choice (G) could be conditioned by population ageing (path H) if there are systematic differences in the economic outcomes that older and younger people care about. Recent research suggests that the elderly are more likely to punish incumbents for high inflation and poor stock market performance, and less likely to punish them for low economic growth than the working age population (Bojar and Vlandas Citation2021; Vlandas Citation2018). As a result, the elderly may be less likely to punish incumbents for low economic growth than the working age population.

The implications of this differential responsiveness are potentially far-reaching. In a recent book Iversen and Soskice (Citation2019) argue that retrospective economic voting incentivises governments to prioritise income growth for the median voter. As a result they are incentivised to prioritise investment in growth enhancing social investment policies (Hemerijck Citation2018; Morel, Palier, and Palme Citation2011). If ageing populations fail to punish incumbents for low growth, this feedback loop is broken, and governments no longer have the incentive to enact growth-enhancing but politically costly reform programmes. As a result, differential responsiveness to economic outcomes is another way in which population ageing can shape economic outcomes through political channels.

Thus, our literature review suggests that the economic impact of population ageing can work through political channels as well as the economic and demographic mechanisms traditionally studied. While there is strong evidence for some parts of the causal chain connecting population ageing to economic outcomes, such as age differences in turnout, others have been explored much less often, such as the differential responsiveness of older people to economic outcomes. These issues should take centre stage in future work seeking to understand the politics and economics of ageing.

Discussion and conclusion

This article carries out a systematic review to summarise the key findings of a large body of literature on the economic, political, and policy consequences of population ageing. Exploiting the ability of algorithmic network analysis techniques to identify clusters of relevant literature, alongside hand coding, we identified and reviewed 143 articles on a wide variety of topics across several disciplines including political science, social policy, and economics.

In terms of their policy preferences, we find that the elderly are generally more supportive of pension spending, although this policy can also be popular with younger people. Older people are notably less supportive of spending on childcare and education than the young, albeit with substantial heterogeneity across countries. These differences in policy preferences matter politically not only because the elderly are numerous, but also because they are more likely to vote, across a wide variety of countries and elections. When the elderly do vote, they both vote for more conservative parties, and are more loyal to the parties they have supported in the past. Given these preferences and political behaviours, population ageing is in turn associated with lower education spending, and possibly with greater healthcare and pension spending. We find little indication in the literature that population ageing leads to mass pension retrenchment, but there is some evidence that pension generosity fails to keep up with a growing population of recipients.

Our review suggests there are some areas that have been neglected in existing literature. One gap concerns the distributive consequences of ageing. For instance, does generous public pension provision compress the income distribution and reduce poverty? Does the liquidation of assets for consumption purposes among the old transform wealth inequalities into consumption inequalities more starkly among the elderly than among other age groups (Lim and Zeng Citation2016)? Does the risk of poverty among pensioners drive support for redistributive policies more broadly, or do the elderly constitute a key electoral veto player against increased taxation on wealth?

The systematisation of our findings in reveals several gaps in the causal chains linking population ageing to policy and economic outcomes of interest. We found little evidence about how population ageing affects the positions that political parties take on public spending and economic policy (for an exception, see Vlandas Citation2018). Comparative manifesto data is increasingly being used to link party position to both public opinion and policy outputs (e.g. Kohl Citation2018; O’Grady and Abou-Chadi Citation2019). Scholars could use such data to empirically investigate the support for their assumptions about policy responsiveness to the preferences of ageing voters, by delineating the role that political party positioning plays in linking population ageing to policy outcomes.

Another gap in existing literature concerns the ways in which population ageing affects economic outcomes through political rather than purely economic channels. Our findings suggest that population ageing might lead to reduced investment in human capital, which is necessary for long-term growth. Future research could provide more detail on the magnitude of this effect, as well as looking at how population ageing shapes support for other growth-enhancing policies such as infrastructure spending or support for research and development. We point to some other areas that would benefit from further study, including the impact of the policy preferences of the elderly on taxation and immigration policy.

A related area for further study concerns how population ageing alters the public’s retrospective evaluations of economic performance and policy choices. Recent research has revealed that elderly voters are more willing to punish incumbents for high inflation but less likely to punish them electorally for high unemployment (Bojar and Vlandas Citation2021). However, we still know little about the extent to which these differences in retrospective economic voting lead to systematic changes in policy choices and public spending. In particular, does population ageing make austerity programs more likely by insulating governments from electoral backlash when retrenching welfare benefits and public services aimed at children or the working age population?

In the long run, continued population ageing is likely to lead to a growing share of the electorate exiting the labour market and relying on pensions and income streams from assets (especially home ownership). The findings of this review suggest that these profound demographic changes have important political consequences, which may in turn reshape the debated relationship between democracy and capitalism. As a result, investigating the political effects of ageing on the economy is of vital importance for future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

5 Without disciplinary restrictions in the WoS, more than 220k search results were returned.

6 We focus on articles in peer reviewed journals, and do not cover monographs, edited volumes, or policy reports and working papers, as outputs of this type are much harder to systematically search.

7 This perspective may neglect heterogeneity within the older population – older people who benefited from government spending in the US are more likely to vote Democrat (Lacy Citation2014).

8 This is a consequence of the perfect linear relationship between age, cohort, and period. If one uses data from only one period, all individuals who are the same age will be in the same birth cohort, and the two cannot be empirically disentangled.

9 Górecki (Citation2015) argues that it is probably social ageing, rather than the experience of participating in more elections, that drives the development of habitual voting.

10 See also Fisher (Citation2008) for further evidence on age differences in left-right orientation in the US.

11 Other studies focus on confidence in the pension system among working age adults (Bay and Pedersen Citation2004).

12 Though there are also studies suggesting no association between population ageing and welfare spending (Gizelis Citation2005).

13 Brunner and Ross (Citation2010) study Californian referenda to show how population age structure affects support for lowering the threshold majority required for school funding referenda to pass.

14 While recognising that party choice is shaped by a range of factors other than policy preferences, we do not discuss pathway C any further, as none of the studies we reviewed provided strong reason to think that this pathway operates differently according to age.

15 This is another path that we do not discuss in detail given space limitations.

References

- Acemoglu, D., and P. Restrepo. 2017. “Secular Stagnation? The Effect of Aging on Economic Growth in the Age of Automation.” American Economic Review 107 (5): 174–179.

- Alesina, A., and E. La Ferrara. 2005. “Preferences for Redistribution in the Land of Opportunities.” Journal of Public Economics 89 (5–6): 897–931.

- Anderson, K. M. 2015. “The Politics of Incremental Change: Institutional Change in Old-Age Pensions and Health Care in Germany.” Journal for Labour Market Research 48 (2): 113–131.

- André, S., and C. Dewilde. 2016. “Home Ownership and Support for Government Redistribution.” Comparative European Politics 14 (3): 319–348.

- Andrews, D., J. Oberoi, T. Wirjanto, and C. Zhou. 2018. “Demography and Inflation: An International Study.” North American Actuarial Journal 22 (2): 210–222. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10920277.2017.1387572.

- Ang, J. B., and J. B. Madsen. 2015. “Imitation Versus Innovation in an Aging Society: International Evidence Since 1870.” Journal of Population Economics 28 (2): 299–327.

- Ansell, B. 2014. “The Political Economy of Ownership: Housing Markets and the Welfare State.” American Political Science Review 108 (2): 383–402.

- Ansell, B. 2019. “The Politics of Housing.” Annual Review of Political Science 22 (1): 165–185.

- Ansolabehere, S., E. Hersh, and K. Shepsle. 2012. “Movers, Stayers, and Registration: Why Age is Correlated with Registration in the U.S.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 7 (4): 333–363.

- Aysan, M. F., and R. Beaujot. 2009. “Welfare Regimes for Aging Populations: No Single Path for Reform.” Population and Development Review 35 (4): 701–720.

- Baek, S. H., Y. K. Ryu, and S. S. Lee. 2017. “The Political Economy of Changes in Family and Old-Age Welfare Policy Spending: Analysis of OECD Countries, 1998–2011.” International Journal of Social Welfare 26 (2): 116–126.

- Banks, J. 2006. “Economic Capabilities, Choices and Outcomes at Older Ages.” Fiscal Studies 27 (3): 281–311.

- Barnes, L. 2015. “The Size and Shape of Government: Preferences Over Redistributive Tax Policy.” Socio-Economic Review 13 (1): 55–78.

- Barro, R. J. 2001. “Human Capital and Growth.” American Economic Review 91 (2): 12–17.

- Bay, A. H., and A. W. Pedersen. 2004. “National Pension Systems and Mass Opinion: A Case Study of Confidence, Satisfaction and Political Attitudes in Norway.” International Journal of Social Welfare 13 (2): 112–123.

- Berry, C. 2014. “Young People and the Ageing Electorate: Breaking the Unwritten Rule of Representative Democracy.” Parliamentary Affairs 67 (3): 708–725.

- Bhatti, Y., and K. M. Hansen. 2012. “The Effect of Generation and Age on Turnout to the European Parliament – How Turnout Will Continue to Decline in the Future.” Electoral Studies 31 (2): 262–272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2011.11.004.

- Blais, A., E. Gidengil, N. Nevitte, and R. Nadeau. 2004. “Where Does Turnout Decline Come From?” European Journal of Political Research 43 (2): 221–236.

- Blondel, V. D., J. L. Guillaume, R. Lambiotte, and E. Lefebvre. 2008. “Fast Unfolding of Communities in Large Networks.” Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 10: P10008.

- Bojar, A., and T. Vlandas. 2021. “Group-Specific Responses to Retrospective Economic Performance: A Multi-Level Analysis of Parliamentary Elections.” Politics & Society. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329221989150.

- Bonoli, G., and F. Reber. 2010. “The Political Economy of Childcare in OECD Countries: Explaining Cross-National Variation in Spending and Coverage Rates.” European Journal of Political Research 49 (1): 97–118.

- Breyer, F., J. Costa-Font, and S. Felder. 2010. “Ageing, Health, and Health Care.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 26 (4): 674–690.

- Brooks, C., and J. Manza. 2006. “Social Policy Responsiveness in Developed Democracies.” American Sociological Review 71 (3): 474–494.

- Brunner, E., and E. Balsdon. 2004. “Intergenerational Conflict and the Political Economy of School Spending.” Journal of Urban Economics 56 (2): 369–388.

- Brunner, E. J., and S. L. Ross. 2010. “Is the Median Voter Decisive? Evidence from Referenda Voting Patterns.” Journal of Public Economics 94 (11–12): 898–910. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.09.009.

- Busemeyer, M. R., A. Goerres, and S. Weschle. 2009. “Attitudes Towards Redistributive Spending in an Era of Demographic Ageing: The Rival Pressures from Age and Income in 14 OECD Countries.” Journal of European Social Policy 19 (3): 195–212.

- Butler, D., and D. Stokes. 1983. Political Change in Britain. London: MacMillan Press.

- Casamatta, G., and L. Batté. 2016. The Political Economy of Population Aging. Handbook of the Economics of Population Aging (1st ed.). Elsevier B.V. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.hespa.2016.07.001.

- Castelló-Climent, A. 2019. “The Age Structure of Human Capital and Economic Growth.” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 81 (2): 394–411.

- Cattaneo, M. A., and S. C. Wolter. 2009. “Are the Elderly a Threat to Educational Expenditures?” European Journal of Political Economy 25 (2): 225–236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2008.10.002.

- Caughey, D., T. O’Grady, and C. Warshaw. 2019. “Policy Ideology in European Mass Publics, 1981–2016.” American Political Science Review 113 (3): 674–693.

- Colombier, C. 2018. “Population Ageing in Healthcare – A Minor Issue? Evidence from Switzerland.” Applied Economics 50 (15): 1746–1760. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2017.1374538.

- Conesa, J. C., and D. Krueger. 1999. “Social Security Reform with Heterogeneous Agents.” Review of Economic Dynamics 2 (4): 757–795.

- Corneo, G., and H. P. Gruner. 2002. “Individual Preferences for Political Redistribution.” Journal of Public Economics 83: 83–107.

- Cutler, D. M., J. M. Poterba, L. M. Sheiner, and L. H. Summers. 1990. “Aging Society: Opportunity or Challenge?” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 21 (1): 1–73.

- Darby, J., and J. Mélitz. 2008. “Social Expenditure and Automatic Stabilisers in the OECD.” Economic Policy 23 (56): 715–756. http://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/8709/.

- Dassonneville, R. 2013. “Questioning Generational Replacement. An Age, Period and Cohort Analysis of Electoral Volatility in the Netherlands, 1971–2010.” Electoral Studies 32 (1): 37–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.09.004.

- Dassonneville, R., M. Hooghe, and B. Vanhoutte. 2012. “Age, Period and Cohort Effects in the Decline of Party Identification in Germany: An Analysis of a Two Decade Panel Study in Germany (1992–2009).” German Politics 21 (2): 209–227.

- Demery, D., and N. W. Duck. 2006. “Demographic Change and the UK Savings Rate.” Applied Economics 38 (2): 119–136.

- de Walque, G. 2005. “Voting on Pensions: A Survey.” Journal of Economic Surveys 19 (2): 181–209.

- Eichholtz, P., and T. Lindenthal. 2014. “Demographics, Human Capital, and the Demand for Housing.” Journal of Housing Economics 26: 19–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2014.06.002.

- Erikson, R. S. 2015. “Income Inequality and Policy Responsiveness.” Annual Review of Political Science 18: 11–29.

- Erikson, R. S., M. B. MacKuen, and J. A. Stimson. 2000. “Bankers or Peasants Revisited: Economic Expectations and Presidential Approval.” Electoral Studies 19 (2–3): 295–312.

- Errata. 2007. International organization.

- European Commission. 2014. The 2015 ageing report underlying assumptions and projection methodologies. Brussels.

- Fernández, J. J., and A. M. Jaime-Castillo. 2013. “Positive or Negative Policy Feedbacks? Explaining Popular Attitudes Towards Pragmatic Pension Policy Reforms.” European Sociological Review 29 (4): 803–815.

- Feyrer, J. 2007. “Demographics and Productivity.” Review of Economics and Statistics 89 (1): 100–109.

- Fisher, P. 2008. “Is There an Emerging Age Gap in US Politics?” Society 45 (6): 504–511.

- Fullerton, A. S., and J. C. Dixon. 2010. “Generational Conflict or Methodological Artifact? Reconsidering the Relationship Between Age and Policy Attitudes in the U.S., 1984–2008.” Public Opinion Quarterly 74 (4): 643–673.

- Furlong, A., and F. Cartmel. 2012. “Social Change and Political Engagement Among Young People: Generation and the 2009/2010 British Election Survey.” Parliamentary Affairs 65 (1): 13–28.

- Gajewski, P. 2015. “Is Ageing Deflationary? Some Evidence from OECD Countries.” Applied Economics Letters 22 (11): 916–919. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2014.987911.

- Galasso, V., and P. Profeta. 2007. “How Does Ageing Affect the Welfare State?” European Journal of Political Economy 23 (2): 554–563.

- Gallego, A. 2009. “Where Else Does Turnout Decline Come From? Education, Age, Generation and Period Effects in Three European Countries.” Scandinavian Political Studies 32 (1): 23–44.

- Ghilarducci, T., J. Saad-lessler, and E. Fisher. 2012. “The Macroeconomic Stabilisation Effects of Social Security and 401(K) Plans.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 36 (1): 237–251.

- Gilens, M., and B. I. Page. 2014. “Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens.” Perspectives on Politics 12 (3): 564–581.

- Gimpel, J. G., I. L. Morris, and D. R. Armstrong. 2004. “Turnout and the Local Age Distribution: Examining Political Participation Across Space and Time.” Political Geography 23 (1): 71–95.

- Gizelis, T. I. 2005. “Globalization, Integration, and the European Welfare State.” International Interactions 31 (2): 139–162.

- Goerres, A. 2009. The Political Participation of Older People in Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Goerres, A., and M. Tepe. 2010. “Age-Based Self-Interest, Intergenerational Solidarity and the Welfare State: A Comparative Analysis of Older People’s Attitudes Towards Public Childcare in 12 OECD Countries.” European Journal of Political Research 49 (6): 818–851.

- Gordon, R. J. 2016. The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Liv- ing Since the Civil War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Górecki, M. A. 2015. “Age, Experience and the Contextual Determinants of Turnout: A Deeper Look at the Process of Habit Formation in Electoral Participation.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 25 (4): 425–443.

- Grafstein, R. 2009. “Antisocial Security: The Puzzle of Beggar-Thy-Children Policies.” American Journal of Political Science 53 (3): 710–725.

- Grasso, M. T., S. Farrall, E. Gray, C. Hay, and W. Jennings. 2019a. “Thatcher’s Children, Blair’s Babies, Political Socialization and Trickle-Down Value Change: An Age, Period and Cohort Analysis.” British Journal of Political Science 49 (1): 17–36.

- Grasso, M. T., S. Farrall, E. Gray, C. Hay, and W. Jennings. 2019b. “Socialization and Generational Political Trajectories: An Age, Period and Cohort Analysis of Political Participation in Britain.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 29 (2): 199–221.

- Hainmueller, J., and M. J. Hiscox. 2007. “Educated Preferences: Explaining Attitudes Toward Immigration in Europe.” International Organization 61 (2): 399–442.

- Halikiopoulou, D., and T. Vlandas. 2020. “When Economic and Cultural Interests Align: The Anti-Immigration Voter Coalitions Driving Far Right Party Success in Europe.” European Political Science Review 12 (4): 427–448. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S175577392000020X.

- Hall, P. A., and D. W. Soskice. 2001. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hamil-Luker, J. 2001. “The Prospects of Age War: Inequality Between (and Within) Age Groups.” Social Science Research 30 (3): 386–400.

- Hansen, A. H. 1939. “Economic Progress and Declining Population Growth.” American Economic Review 29 (1): 1–15.

- Harper, S. 2014. “Economic and Social Implications of Aging Societies.” Science 346 (6209): 587–591.

- Harris, A. R., W. N. Evans, and R. M. Schwab. 2001. “Education Spending in an Aging America.” Journal of Public Economics 81 (3): 449–472.

- Hassan, A., R. Salim, and H. Bloch. 2011. “Population Age Structure, Saving, Capital Flows and the Real Exchange Rate: A Survey of the Literature.” Journal of Economic Surveys 25 (4): 708–736.

- Hemerijck, A. 2018. “Social Investment as a Policy Paradigm.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (6): 810–827.

- Hennighausen, T., and F. Heinemann. 2015. “Don’t Tax Me? Determinants of Individual Attitudes Toward Progressive Taxation.” German Economic Review 16 (3): 255–289.

- Hicks, A., and C. Zorn. 2005. “Economic Globalization, the Macro Economy, and Reversals of Welfare: Expansion in Affluent Democracies, 1978–1994.” International Organization 59 (3): 631–662.

- Hollibaugh, G. E., L. S. Rothenberg, and K. K. Rulison. 2013. “Does It Really Hurt to Be Out of Step?” Political Research Quarterly 66 (4): 856–867.

- Horioka, C. Y. 2010. “The (Dis)Saving Behavior of the Aged in Japan.” Japan and the World Economy 22 (3): 151–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2010.02.001.

- Iversen, T., and D. Soskice. 2019. Democracy and Prosperity: Reinventing Capitalism Through a Turbulent Century. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Karatzas, G. 2000. “On the Determination of the US Aggregate Health Care Expenditure.” Applied Economics 32 (9): 1085–1099.

- Kim, K., and Y. Lee. 2008. “A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Strategies for an Ageing Society, with Special Reference to Pension and Employment Policies.” International Journal of Social Welfare 17 (3): 225–235.

- Kogan, V., S. Lavertu, and Z. Peskowitz. 2018. “Election Timing, Electorate Composition, and Policy Outcomes: Evidence from School Districts.” American Journal of Political Science 62 (3): 637–651.

- Kohl, S. 2018. “The Political Economy of Homeownership: A Comparative Analysis of Homeownership Ideology Through Party Manifestos.” Socio-Economic Review 0 (0): 1–26. https://academic.oup.com/ser/advance-article/doi/https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwy030/5051712.

- Krieger, T., and J. Ruhose. 2013. “Honey, I Shrunk the Kids’ Benefits-Revisiting Intergenerational Conflict in OECD Countries.” Public Choice 157 (1–2): 115–143.

- Kurban, H., R. M. Gallagher, and J. J. Persky. 2015. “Demographic Changes and Education Expenditures: A Reinterpretation.” Economics of Education Review 45: 103–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.01.001.

- Lacy, D. 2014. “Moochers and Makers in the Voting Booth.” Public Opinion Quarterly 78 (S1): 255–275.

- Ladd, H. F., and S. E. Murray. 2001. “Intergenerational Conflict Reconsidered: County Demographic Structure and the Demand for Public Education.” Economics of Education Review 20 (4): 343–357.

- Lim, G. C., and Q. Zeng. 2016. “Consumption, Income, and Wealth: Evidence from Age, Cohort, and Period Elasticities.” Review of Income and Wealth 62 (3): 489–508.

- Lin, Y. F., Y. Kamo, and T. Slack. 2018. “Is it the Government’s Responsibility to Reduce Income Inequality? An Age-Period-Cohort Analysis of Public Opinion Toward Redistributive Policy in the United States, 1978 to 2016.” Sociological Spectrum 38 (3): 162–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2018.1469443.

- Lynch, J., and M. Myrskylä. 2009. “Always the Third Rail?” Comparative Political Studies 42 (8): 1068–1097.

- Lyons, W., and R. Alexander. 2000. “A Tale of Two Electorates: Generational Replacement and the Decline of Voting in Presidential Elections.” Journal of Politics 62 (4): 1014–1034.

- Mahlberg, B., I. Freund, J. Crespo Cuaresma, and A. Prskawetz. 2013. “Ageing, Productivity and Wages in Austria.” Labour Economics 22: 5–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2012.09.005.

- Marconi, G. 2018. “Education as a Long-Term Investment: The Decisive Role of Age in the Education-Growth Relationship.” Kyklos 71 (1): 132–161.

- Martikainen, P., T. Martikainen, and H. Wass. 2005. “The Effect of Socioeconomic Factors on Voter Turnout in Finland: A Register-Based Study of 2.9 Million Voters.” European Journal of Political Research 44 (5): 645–669.

- Martín, J. J. M., M. P. L. del Amo Gonzalez, and M. D. Cano Garcia. 2011. “Review of the Literature on the Determinants of Healthcare Expenditure.” Applied Economics 43 (1): 19–46.

- Morel, N., B. Palier, and J. Palme. 2011. Towards a Social Investment State? Bristol: Policy Press.

- Muuri, A. 2010. “The Impact of the Use of the Social Welfare Services or Social Security Benefits on Attitudes to Social Welfare Policies.” International Journal of Social Welfare 19 (2): 182–193.

- Nishiyama, S., and K. A. Smetters. 2014. “Financing Old Age Dependency.” Annual Review of Economics 6: 53–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080213-041304.

- Norpoth, H. 1996. “Presidents and the Prospective Voter.” Journal of Politics 58 (3): 776–792.

- Noy, S. 2011. “New Contexts, Different Patterns? A Comparative Analysis of Social Spending and Government Health Expenditure in Latin America and the OECD.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 52 (3): 215–244.

- O’Grady, T., and T. Abou-Chadi. 2019. “Not So Responsive After All: European Parties do not Respond to Public Opinion Shifts Across Multiple Issue Dimensions.” Research and Politics 6: 4.

- Persson, M., H. Wass, and H. Oscarsson. 2013. “The Generational Effect in Turnout in the Swedish General Elections, 1960–2010.” Scandinavian Political Studies 36 (3): 249–269.

- Pettersen, P. A. 2001. “Welfare State Legitimacy: Ranking, Rating, Paying: The Popularity and Support for Norwegian Welfare Programmes in the mid-1990s.” Scandinavian Political Studies 24 (1): 27–49.

- Plutzer, E., and M. Berkman. 2005. “The Graying of America and Support for Funding the Nation’s Schools.” Public Opinion Quarterly 69 (1): 66–86.

- Poterba, J. M. 2001. “Demographic Structure and Asset Returns.” Review of Economics and Statistics 83 (4): 565–584.

- Prinzen, K. 2015. “Attitudes Toward Intergenerational Redistribution in the Welfare State.” Kolner Zeitschrift fur Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 67: 349–370.

- Quadagno, J., and J. Pederson. 2012. “Has Support for Social Security Declined? Attitudes Toward the Public Pension Scheme in the USA, 2000 and 2010.” International Journal of Social Welfare 21 (SUPPL.1): 88–100.

- Quayes, S., and A. M. M. Jamal. 2016. “Impact of Demographic Change on Stock Prices.” Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 60: 172–179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2015.08.005.

- Raghavan, U.N., R. Albert, and S. Kumara. 2007. “Near Linear Time Algorithm to Detect Community Structures in Large-Scale Networks.” Physical Review E 76 (3): 036106.

- Rattsø, J., and R. J. Sørensen. 2010. “Grey Power and Public Budgets: Family Altruism Helps Children, But Not the Elderly.” European Journal of Political Economy 26 (2): 222–234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2009.11.010.

- Rueda, D., and D. Stegmueller. 2016. “The Externalities of Inequality: Fear of Crime and Preferences for Redisitribution in Western Europe.” American Journal of Political Science 60 (2): 472–489.

- Sabbagh, C., and P. Vanhuysse. 2014. “Perceived Pension Injustice: A Multidimensional Model for Two Most-Different Cases.” International Journal of Social Welfare 23 (2): 174–184.

- Shelton, C. A. 2008. “The Aging Population and the Size of the Welfare State: Is There a Puzzle?” Journal of Public Economics 92 (3–4): 647–651.

- Silverstein, M., T. M. Parrott, J. J. Angelelli, and F. L. Cook. 2000. “Solidarity and Tension Between Age-Groups in the United States: Challenge for an Aging America in the 21st Century.” International Journal of Social Welfare 9 (4): 270–284.

- Simoni, M., and T. Vlandas. 2021. “Labour Market Liberalization and the Rise of Dualism in Europe as the Interplay Between Governments, Trade Unions and the Economy.” Social Policy & Administration 55 (4): 637–658. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12648.

- Smets, K., and A. Neundorf. 2014. “The Hierarchies of Age-Period-Cohort Research: Political Context and the Development of Generational Turnout Patterns.” Electoral Studies 33: 41–51.

- Sørensen, R. J. 2013. “Does Aging Affect Preferences for Welfare Spending? A Study of Peoples’ Spending Preferences in 22 Countries, 1985–2006.” European Journal of Political Economy 29 (1): 259–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2012.09.004.

- Stegmaier, M., and M. S. Lewis-Beck. 2013. “The VP-Function Revisited: A Survey of the Literature on Vote and Popularity Functions After Over 40 Years.” Public Choice 157 (3/4): 367–385.

- Street, D., and J. S. Cossman. 2006. “Greatest Generation or Greedy Geezers ?” Social Problems 53 (1): 75–96.

- Summers, L. H. 2015. “Demand Side Secular Stagnation.” American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 105 (5): 60–65.

- Sundberg, T., and P. Taylor-Gooby. 2013. “A Systematic Review of Comparative Studies of Attitudes to Social Policy.” Evidence and Evaluation in Social Policy 47 (4): 416–433.

- Svallfors, S. 2008. “The Generational Contract in Sweden : Age-Specific Attitudes to Age-Related Policies.” Policy and Politics 36 (3): 381–396.

- Takáts, E. 2012. “Aging and House Prices.” Journal of Housing Economics 21 (2): 131–141.

- Tamakoshi, T., and S. Hamori. 2015. “Health-Care Expenditure, GDP and Share of the Elderly in Japan: A Panel Cointegration Analysis.” Applied Economics Letters 22 (9): 725–729. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2014.972540.

- Tawfik, A., P. Sciarini, and E. Horber. 2012. “Putting Voter Turnout in a Longitudinal and Contextual Perspective: An Analysis of Actual Participation Data.” International Political Science Review 33 (3): 352–371.

- Taylor-Gooby, P. 2002. “The Silver Age of the Welfare State: Perspectives on Resilience.” Journal of Social Policy 31 (4): 597–621.

- Tedin, K. L., R. E. Matland, and G. R. Weiher. 2001. “Age, Race, Self-Interest, and Financing Public Schools Through Referenda.” Journal of Politics 63 (1): 270–294. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-3816.00068.

- Temple, J. 1999. “A Positive Effect of Human Capital on Growth.” Economics Letters 65 (1): 131–134.

- Tepe, M., and P. Vanhuysse. 2009. “Are Aging OECD Welfare States on the Path to Gerontocracy? Evidence from Democracies, 1980–2002.” Journal of Public Policy 29 (1): 1–28.

- Tepe, M., and P. Vanhuysse. 2010. “Elderly Bias, New Social Risks and Social Spending: Change and Timing in Eight Programmes Across Four Worlds of Welfare, 1980–2003.” Journal of European Social Policy 20 (3): 217–234.

- Tilley, J. 2002. “Political Generations and Partisanship in the UK, 1964–1997.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A: Statistics in Society 165 (1): 121–135.