ABSTRACT

Since their transition to democracy in the 1970s, Spain and Portugal have been ‘immune’ to the success of populist radical right (PRR) parties. This exceptional situation, however, came to an end: Chega’s leader, André Ventura, was elected in the Portuguese parliament, while VOX has become the third most voted political party of Spain. Using new online survey data from the Spanish and Portuguese national elections in 2019, we find that the Iberian PRR electorate is mostly in line with the characteristics of the PRR electorate in Western Europe when it comes to socio-demographics, political dissatisfaction, media diet, and the rejection of immigration and feminism. Interestingly, however, the support for Chega and VOX does not come from economic losers of globalization. Finally, both parties capitalize on country-specific issues —national unity in Spain and welfare in Portugal— but PRR parties might struggle to establish themselves within the party system of the two Iberian countries.

Introduction

Between 2018 and 2019, Iberian exceptionalism came to an end: VOX gained 12 seats in the regional parliament of Andalusia and subsequently became the third most voted party at the national level, while Chega was the first radical right party to obtain a seat in the Portuguese parliament and its leader came third at the 2021 presidential elections. For the first time since the end of the authoritarian regimes of Francisco Franco and António Salazar, populist radical right (PRR) parties obtained representation in the political systems of the two Iberian countries. The electoral success of PRR parties is common in Europe, but since their return to democracy in the mid-1970s Spain and Portugal were two countries considered ‘immune’. With the end of Iberian exceptionalism, it is time to analyze the demand-side factors driving the vote for VOX and Chega to understand whether their electorate presents the characteristics described in the relevant literature and to what extent the electoral breakthrough of PRR parties in formerly negative cases is linked to peculiar factors.

No country is immune to nativism, authoritarianism, and populism —the key ideological elements of PRR parties (Mudde Citation2019) – hence, the end of Iberian exceptionalism should not come as a complete surprise. However, Portugal and Spain represent particularly interesting cases for the study of PRR parties for at least three reasons. First, they both expressed a very strong resilience against PRR parties (Alonso and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2015; da Silva and Salgado Citation2018), a fact that has only a few parallels in Europe.Footnote1 Second, the end of this exceptional situation followed an almost identical timing, with VOX gaining representation for the first time in 2018 in the regional elections of Andalusia and confirming its performance at the national level in the following April, and Chega electing its leader André Ventura in parliament in October 2019, later coming third in presidential elections in January 2021.Footnote2 Third, Spain and Portugal are two comparable countries because they followed similar political trajectories; they have a similar political and electoral system; and they both suffered the consequences of the Great Recession and the subsequent socio-economic crisis.

Empirically, we use new online survey data from the 2019 national elections in both countries to determine how different sets of variables affect respondents’ self-reported probabilities to vote (PTV) as well as vote choice for VOX and Chega. We demonstrate that on the one hand Chega and VOX attract supporters with expected characteristics: young, religious men with low education from (in the case of Chega) rural areas. Further, political dissatisfaction and a media diet based on Facebook and tabloids predict the vote for the two PRR parties. But while VOX and Chega voters are clearly opposed to cultural openness, and show strong anti-immigration, anti-globalization, and (in the case of VOX) anti-feminism feelings, they cannot necessarily be characterized as economic globalization losers. Another element that makes the supporter of VOX and Chega stand out is their position on very salient issues in the respective countries — territorial unity in Spain, and welfare in Portugal.

We study the type of electorate of VOX and Chega to assess if it corresponds to the kind of PRR voters usually identified in the literature. Our aim is to understand whether the electorate of VOX and Chega is comparable to the electorate of PRR parties across Europe, and to what extent the end of the Iberian exceptionalism relies on specific elements.Footnote3 For this purpose, we structure the article as follows: first, we describe the two PRR parties and their background, to then review the relevant literature and develop our hypotheses on which factors could explain the vote for both Chega and VOX. Next, we describe the data we use and proceed to the empirical analysis, concluding with the implications and limitations of this study.

VOX and Chega

This section sketches a brief history of VOX and Chega, their leaders, their ideological characteristics, and their position on particularly relevant issues, arguing that these two parties are comparable. First, both Chega and VOX show the three characteristics common to every PRR party (Mudde Citation2007): the use of a populist rhetoric, separating society in a Manichean way between the pure people and corrupt elites; the presence of nativism, promising to protect native born inhabitants against migrants; and authoritarianism, advocating for a strictly ordered society and therefore placing strong emphasis on the importance of law and order. Both parties show these characteristics and therefore they have been classified as belonging to the family of the populist radical right (Rooduijn et al. Citation2020).Footnote4

Concerning the use of a populist discourse, both Chega and VOX articulate a classic ‘us vs. them’ rhetoric that separates Portuguese and Spaniards from alien groups such as migrants and mainstream political elites while challenging basic features of liberal democracy such as social diversity and respect for minority rights. At the same time, both parties claim to represent the ‘voice of the people’ in opposition to the political correctness of mainstream politics (Mendes and Dennison Citation2020). The two parties present a slightly different type of nativism, because Roma communities are Chega’s main target while VOX is against migrants in general and Muslim ones in particular.Footnote5 Both Chega and VOX focus on ‘crime and security’ as well as ‘law and order’, proposing an authoritarian vision of society (Ferreira Citation2019), which insists on traditional gender norms and opposes feminism (Bernardez-Rodal, Requeijo Rey and Franco Citation2020; Mendes and Dennison, Citation2020). In particular, VOX compares feminism to a violent ideology —‘the feminist jihad’— where feminists —‘Feminazis’— are part of a ‘progressive dictatorship’ (Ribera Payá and Díaz Martínez Citation2020). Similarly, Chega considers abortion as tyranny, and claims to fight against the ‘dictatorship of gender ideology’ (Chega Citation2019).Footnote6

The leaders of VOX and Chega followed similar political trajectories as well: they both started within the mainstream right but eventually decided to form a more radical party. André Ventura has enjoyed a significant visibility as football commentator for a national TV channel between 2014 and 2020, and he was a member of the mainstream —and despite the name right-wing— Social Democratic Party (Partido Social Democrata – PSD). Ventura resigned in October 2018 and created Chega in April 2019, becoming only a few months later Member of Parliament for the Lisbon constituency. Similarly, Santiago Abascal was city councillor and member of the Basque Parliament representing the People’s Party (Partido Popular – PP), until he grew disillusioned with the PP and created VOX in December 2013. The fact that both leaders have a background in mainstream right-wing parties might have helped them to receive greater visibility and a less stigmatized image from the media (Mendes and Dennison Citation2020). In conclusion, VOX and Chega are two comparable PRR parties that experienced an electoral breakthrough in two countries traditionally considered ‘immune’, and the next section advances several hypotheses concerning their electorate.

Hypotheses to explain the vote for VOX and Chega

In order to identify the demand-side factors linked to the support for VOX and Chega, we formulate several hypotheses based on the literature on PRR parties. We recognize that the electorate supporting PRR parties, the demand-side, interacts with supply-side factors, including how these parties act within the political opportunity structure and the political space left open by the competitors (Eatwell Citation2003; Golder Citation2016). This exploratory study, however, does not try to provide an all-encompassing picture of the political opportunity structure available to VOX and Chega or a global account of their electoral performance. We focus on the potential electorate of VOX and Chega to understand to what extent it is comparable to the electorate of similar parties across Europe, and to what extent it shows peculiar elements.

To formulate our hypotheses, we rely on a strand of literature that considers the demand for PRR parties as a reaction to phenomena such as modernization (Betz Citation1994) and globalization (Kriesi et al. Citation2008). Citizens who feel ‘left behind’, or who believe that their social status is threatened (Elchardus and Spruyt Citation2016; Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck Citation2016; Gidron and Hall Citation2020), are often found to be among the electorate of PRR parties because these parties intercept their ‘grievances’ (Rydgren Citation2007). As a result of deindustrialization a large number of less qualified jobs in manufacturing were lost and the manual working class increasingly constitutes the core constituency of the radical right, indicating a process ‘proletarianization’ of the radical right’s support base (Ignazi Citation2003; De Lange Citation2007; Minkenberg and Perrineau Citation2007). In particular, the relative decline in the social hierarchy has been found to make (male) routine workers susceptible to the nativist platforms of PRR parties (Kurer Citation2020). Furthermore, voting for PRR parties is considered as an expression of distrust towards the political elite (Fieschi and Heywood Citation2004), dissatisfaction with the way democracy works (Betz Citation2002), and a rise in public disenchantment with traditional parties (Rooduijn, Van der Brug and de Lange Citation2016).

In addition, we consider a complementary strand of literature on ‘mediatization of politics’ (Esser Citation2013): the media-logic and the political-logic are converging in providing emotional and conflictive stories, and political actors are increasingly aware of how to ‘use’ the media to gain visibility, a process called ‘self-mediatization’ (Strömbäck Citation2008). In this scenario, supporters of PRR parties have a particularly low trust in mainstream media (Fawzi Citation2019), and for this prefer online news (Tsfati Citation2010). The use of social media can influence the electoral performance of populist parties for two reasons: first, social media are especially suited for the communication of populist radical right messages because they allow bypassing the intervention of elite gatekeepers (Engesser et al. Citation2017), and second, populist parties employ populist content and style more frequently on Facebook and Twitter than in political talk shows (Ernst, Blassnig, et al. Citation2019). Political information is a key aspect of voting behaviour and mobilization (Brady, Verba and Schlozman Citation1995), and knowing that political misinformation relates positively to support for right-wing populist parties (van Kessel, Sajuria and van Hauwaert Citation2020), we consider this aspect as very relevant to understand the electorate of PRR parties in a comparative perspective.

Combining these strands of literature and relying on existing empirical studies testing these theories, we derive our hypotheses on the socio-demographic characteristics of citizens supporting PRR parties and their levels of political dissatisfaction, investigating to what extent they can be characterized as economic and cultural ‘losers of globalization’, as well as their media diet. Finally, we formulate a hypothesis about the impact of country-specific issues because the support for PRR parties partially depends on contextual factors (Muis and Immerzeel Citation2017a) and on the levels of politicization of particularly salient topics in the public debate (Grande, Schwarzböz and Fatke Citation2019).

First, we focus on the sociodemographic profile of traditional supporters for PRR parties. The vast literature on the topic suggests that, despite the impossibility to define every characteristic of PRR voters (Rooduijn Citation2018), several elements are consistently present while others depend on context (Muis and Immerzeel Citation2017a). Voters for PRR parties tend to be men more often than women (Harteveld et al. Citation2015; Mudde Citation2019)Footnote7, young (Tillman Citation2021; Zagórski, Rama and Cordero Citation2021)Footnote8, religious (Arzheimer and Carter Citation2009; Zúquete Citation2017)Footnote9, and living in rural rather than urban areas (De Lange and Rooduijn Citation2015; Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018).Footnote10 Lastly, PRR voters also tend to have a low education (Ivarsflaten and Stubager Citation2013; van Hauwaert and van Kessel Citation2018), which is also in line with the arguments of Kriesi et al. (Citation2008).

H1: Young, religious men with low education and living in rural areas are more prone to cast a vote for VOX and Chega.

H2: Those who are more politically dissatisfied are more prone to cast a vote for VOX and Chega.

H3a: Economic ‘losers of globalization’ are more prone to cast a vote for VOX and Chega.

H3b: Cultural ‘losers of globalization’ are more prone to cast a vote for VOX and Chega.

H4: Those who rely on tabloids and social media to gather political information are more prone to cast a vote for VOX and Chega.

In Spain, the centre-periphery cleavage has always been relevant (Morlino Citation1998) and, after having been ‘frozen’ during the Franco era, it re-exploded in recent years, culminating in the Catalan Independence Referendum and the consequent constitutional crisis. As a result, the issue of territorial unity was highly salient in the 2019 elections (Mendes and Dennison Citation2020). Crucially, VOX’s core values include Spanish nationalism, territorial unity and the refusal of regional autonomies, systematic repression of pro-independence movements (Turnbull-Dugarte, Rama and Santana Citation2020), calling for the suspension of the autonomous independence of the Catalan region and the constitutional prohibition of any party that seeks separatist objectives (Turnbull-Dugarte Citation2019). Recent studies found that criticizing the PP for being too tolerant towards regional nationalisms (Vampa Citation2020) VOX was able to gain votes (Rodríguez-Teruel Citation2021).

H5a: Those who are in favor of national unity and against regional separatism are more likely to vote for VOX.

H5b: Those who are in favor of liberalizing and privatizing welfare while reducing public spending are more likely to cast a vote for Chega.

Data

To test our hypotheses, we make use of online survey data collected in 2019, when both Spain (April 28) and Portugal (October 6) held legislative elections. The survey is a representative two-wave panel online survey (one pre – and one post-electoral wave) with a sample of ∼3000 respondents in Spain and ∼1500 respondents in Portugal and fulfils a crossed quota of gender (2 categories), age (3 categories) and education (3 categories).Footnote11 While nonprobability online surveys are less established than probabilistic face-to-face surveys and tend to differ in their marginal distributions, they have been shown to yield very reliable results especially when it comes to causal inferences and explanatory models such as vote choice (Dassonneville et al. Citation2020), which is what we do in this paper.

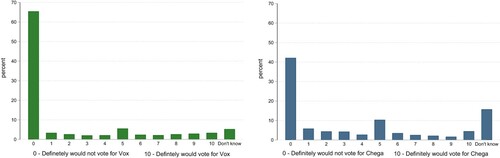

Following Turnbull-Dugarte et al. (Citation2020), we use two dependent variables: self-reported probability to vote (PTV) and vote choice (recall) for VOX and Chega. The PTV item asks respondents to indicate the probability that they would vote for a party on a scale from 0 (definitely would not vote for this party) to 10 (definitely would vote for this party), thus offering a more long-term perspective into the potential electorate of both parties. shows the distribution of this variable for the two PRR parties we analyze. We can see that Chega is less known amongst respondents than VOX, while VOX has a higher percentage of respondents indicating that they would definitely not vote for this party. Given that Chega is a very new party that was only founded a few months before the 2019 elections, this is an expectable pattern.

Indeed, we decided to use the second wave of the online survey that was fielded right after the elections, as the prominence of Chega —and hence the validity and comparability of the PTV measure— is higher than before the elections. For the analysis, we recoded PTV to a 0–1 scale. Compared to actual vote choice, PTV has the advantage that it allows us to analyze a larger N, given that we have data from the whole sample.

Second, and to make sure our results are valid, we replicate the analysis using vote recall (equally from the second wave) as a dependent variable (0 – voted for other parties, 1 – voted for Chega/VOX).Footnote12 This variable captures short-term, election-specific support for both parties (Turnbull-Dugarte, Rama and Santana Citation2020). Especially in the case of Chega, this variable is relying on a rather small set of voters: in the post-electoral survey, we only have 46 respondents who indicated that they had voted for this party, out of 987 who casted a valid vote. In the case of VOX, we have 257 (out of 2243) respondents having voted for them. However, as the next section will show, results are very comparable between PTV and vote recall, with some effects (expectedly) losing significance for Chega when using vote recall, most likely due to the small sample.

Our independent variables are grouped in five categories, and to ease comparison between effect sizes, we equally recode all of them to a scale ranging from 0 to 1 in order to make effect sizes comparable. To test the first hypothesis about sociodemographic factors, we use gender, age (in years, from old to young), education (8 categories, from high to low), religiosity (4 categories), and the area where respondents live (urban to rural, 4 categories). To test our second hypothesis, we use different variables that capture political dissatisfaction: respondents dissatisfaction with the performance of the current government (PS in Portugal, and PSOE in Spain), and for Spain their dissatisfaction with the performance of the previous PP government, given that the government changed only four month prior to the elections; dissatisfaction with democracy (all on a 5-point scale); and the perception of corruption amongst political parties (11-point scale). We also control for ideology (left-right-placement, 11-point scale) in this model. To test the third hypothesis about ‘losers of globalization’, we use two sets of variables: for the economic dimension, respondents’ household income (5-point scale, high to low); their ownership of assets (4 categories; owning a residence, a business/property/land, stocks, or savings; reversed to indicate no assets); and their assessment of the national economic situation as well their personal economic situation (5-point scales). For the cultural dimension we use respondents’ opinion on globalization being bad for their country; their position on immigration (support for a more restrictive immigration policy) and on feminism (the right to abortion in Portugal, acceptability of violence against women in Spain), all 5-point scales.

To test the fourth hypothesis, we use different variables that capture respondents’ media diet: how often they use different online tools to obtain political information (forums, Facebook, and Twitter, all on a 4-point scale); as well as their preferred newspaper, where we code tabloids as 1 (Correio da Manhã in Portugal, ABC in Spain) and other newspapers as 0. To test our fifth hypothesis, we use respondents’ positions on country-specific political issues. For Spain, we use respondents’ positions on Catalan independence, which we measure with two variables: the rejection of autonomy for Catalonia (‘Catalonia has reached too much autonomy’, dichotomous variable) and the support for a centralized state (5-point scale). For Portugal, we use two questions on welfare, asking respondents if they agree that public services should be cut in order to reduce taxation, and if they want the national health system to be privatized, both on an 11-point scale. For descriptive statistics of all variables, see table A4 in the online appendix.

Analysis

Using the data described in the previous section, we test our hypotheses by running simple regression models in the two countries to determine how different sets of variables affect respondents’ self-reported probabilities to vote (PTV) as well as their actual vote (vote recall) for VOX and Chega. Given the relatively small sample size (especially in the case of Portugal), and as we are using a rather large set of independent variables, we decided for a step-wise approach, by running separate models for each hypothesis and each set of predictors to avoid multicollinearity and an over-fit model. All models, however, include the initial set of sociodemographic variables (gender, age, education, rural-urban, religion) as controls. Moreover, full models including all independent variables at once are available in the online appendix (Table A5).

The following figures plot the resulting coefficients (i.e. effect sizes) and 95% confidence intervals for the two parties and for both dependent variables. Note that the models with PTV as a dependent variable are linear regressions, and report regression coefficients. The models with vote recall as a dependent variable are logistic regressions, and coefficients are reported in odds ratios to allow a substantial interpretation. The full models can be found in (PTV) and (vote recall) in the appendix.

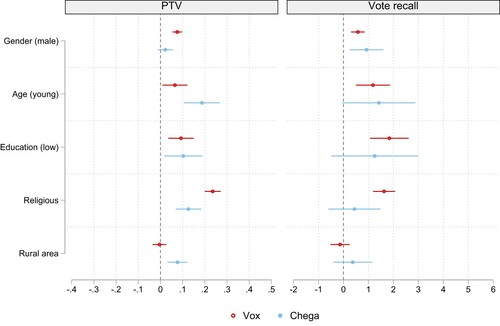

shows how sociodemographic factors influence PTV and vote: we can see that in accordance with our first hypothesis, young men with lower education are more likely to sympathize with and vote for both VOX and Chega.Footnote13 Moreover, VOX and Chega sympathizers and voters tend to be above-average religious, and Chega supporters are more likely to live in rural rather than in urban areas. For Spain, these findings are mostly in line with a recent study by Turnbull-Dugarte et al. (Citation2020), which finds VOX voters to be male, younger, and more religious than average. Contrary to their findings, however, we cannot confirm that VOX supporters are more urban and more educated. The positive effect of low education in both countries is in line findings from Kriesi et al. (Citation2008), and points to the importance of educational differences in triggering ‘cultural voting’ for the radical right (Bornschier Citation2018).

Figure 2. Sociodemographic factors (H1).

Linear regression coefficients (PTV) and odds ratios from logistic regression (vote recall). Full models in and in the Appendix. Data: authors own online survey, wave 2.

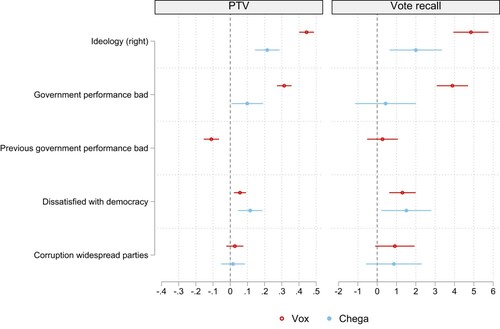

shows the effects of political dissatisfaction. As the following figures, these models include all previously discussed sociodemographic variables as controls. The results mostly confirm our second hypothesis, which assumes that political dissatisfaction increases the likelihood to support VOX and Chega. Indeed, negatively evaluating the performance of the current government (PSOE in Spain and PS in Portugal, both centre-left) strongly increases the likelihood to vote for both VOX and Chega, although for Chega this effect loses significance in the vote recall model, and the effect is generally stronger for VOX. Interestingly though, negative evaluations of the previous PP government actually decrease the PTV for VOX and do not affect vote choice, implying that VOX supporters were rather satisfied with the performance of the PP when it was in power and suggesting that many former PP voters are now sympathizing with —or even voting for— VOX. Dissatisfaction with democracy, as expected, increases the PTV and vote for both VOX and Chega. Despite both parties regularly insisting on the corruption of the political system, the perception that corruption amongst political parties is widespread is not significant in its effect on PTV, and only slightly significant for the vote recall for VOX.Footnote14 When it comes to ideology, as expected, being right leaning is the strongest predictor of support and vote for both parties. In the case of Spain, these results fully support previous findings by Turnbull-Dugarte et al. (Citation2020) as well as Rama et al. (Citation2021), pointing to a strong effect of political dissatisfaction, especially dissatisfaction with democracy, on support for VOX.

Figure 3. Political dissatisfaction (H2).

Linear regression coefficients (PTV) and odds ratios from logistic regression (vote recall). All models additionally control for gender, age, education, religion and rural vs. urban. Full models in and in the Appendix. Data: authors own online survey, wave 2.

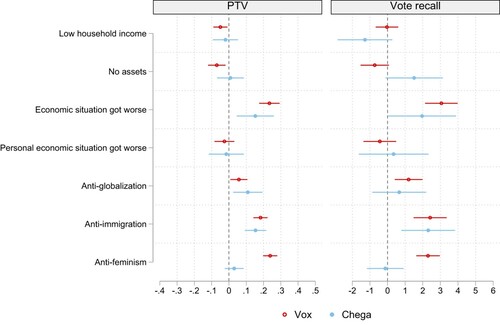

shows our third hypothesis which claims that ‘losers of globalization’ are more likely to cast a vote for VOX and Chega. We test two dimensions: economic as well as cultural ‘losers of globalization’. This model, as all others, controls for socio-economic factors, most importantly education, which Kriesi et al. (Citation2008) found to be a key variable identifying the losers of globalization. In the economic dimension, the results cannot fully confirm this hypothesis: a lower household income and owning no assets actually decrease the PTV, and (to a lesser degree) the vote choice for VOX, while the PTV for Chega is not significantly determined by income or assets. The vote for Chega, however, is actually positively affected by not owning any assets. Both Chega and VOX voters are, on the other hand, strongly convinced that the national economic situation got worse in the past year, but they do not think that their personal economic situation got worse.

Figure 4. Globalization losers (H3).

Linear regression coefficients (PTV) and odds ratios from logistic regression (vote recall). All models additionally control for gender, age, education, religion and rural vs. urban. Full models in and in the Appendix. Data: authors own online survey, wave 2.

In the cultural dimension, the results are clearer: anti-globalization and anti-immigration feelings have a strong effect. Moreover, opposition to feminism also increases the likelihood to vote for VOX, but not significantly for Chega. In conclusion, VOX and Chega voters are not necessarily clear economic globalization losers themselves, but they are critical of the economic situation, and strongly feel as cultural losers of globalization. A positive relationship between a high economic status and support for VOX is in line with the results of by Turnbull-Dugarte et al. (Citation2020). However, contrary to other studies (Ortiz Barquero Citation2019; Turnbull-Dugarte Citation2019) we find a significant relationship between opposition to immigration and the vote for VOX. Importantly, those results hold while controlling for the (positive) effect of low education, which, as previously discussed, is an important factor in explaining economic and cultural attitudes of demarcation (Kriesi et al. Citation2008).

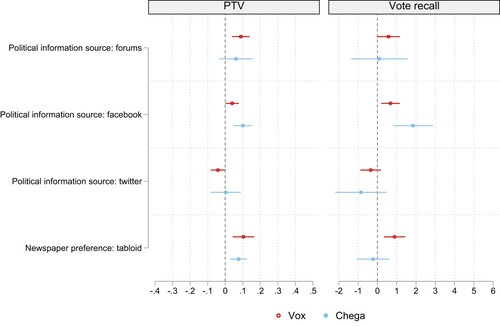

displays the effects of ‘media diet’ on respondents’ voting behaviour, and mostly confirms our fourth hypothesis: using Facebook and (in the case of VOX) internet forums as a source of political information increases the probabilities to vote for a PRR party, while, at least for VOX, using Twitter to obtain political information decreases this probability. Moreover, reading tabloids rather than other newspapers also significantly increases the likelihood to support and vote for both Chega and VOX (however becoming non-significant for Chega’s vote recall). This again confirms the findings of Turnbull-Dugarte et al. (Citation2020) about VOX voters being more likely to follow the election campaign on social media.

Figure 5. Media diet (H4).

Linear regression coefficients (PTV) and odds ratios from logistic regression (vote recall). All models additionally control for gender, age, education, religion and rural vs. urban. Full models in and in the Appendix. Data: authors own online survey, wave 2.

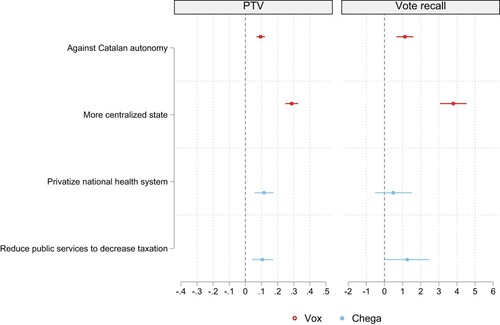

Finally, shows the results for country-specific issues that we expect to drive the vote. In accordance with our last hypotheses and previous findings from Turnbull-Dugarte et al. (Citation2020) country-specific issues significantly affect the vote likelihood for the two PRR parties: in Spain, rejecting Catalan autonomy and supporting a centralized state strongly increases the likelihood to vote for VOX. And similarly, support for a privatized health system and for a reduction in public services increases the likelihood to vote for Chega in Portugal —although to a lesser extent than the Catalan issue in Spain— confirming both H5a and H5b.

Figure 6. Country-specific issues (H5).

Linear regression coefficients (PTV) and odds ratios from logistic regression (vote recall). All models additionally control for gender, age, education, religion and rural vs. urban. Full models in and in the Appendix. Data: authors own online survey, wave 2.

Overall, the results are very consistent using both vote recall and PTV as a dependent variable. The models for Spain replicate almost perfectly the results using PTV, while the results for Portugal are in some cases slightly weaker in their significance than the PTV models. This was to be expected, considering the very small sample of Chega voters. However, the fact that even with the small Portuguese sample all effects still hold their direction, and most remain significant, shows that our findings are robust. Robustness tests using all independent variables at once (Table A5 in the online appendix) show equally consistent results, with directional effects remaining the same despite sometimes lower levels of significance due to the relatively small N. Moreover, we can confirm most of the findings from previous work on the determinants of support for VOX (Turnbull-Dugarte Citation2019; Turnbull-Dugarte, Rama and Santana Citation2020), while adding new findings and being able to compare, for the first time, VOX voters to the Chega electorate.

Conclusions

Since their transition to democracy, the electorates of Spain and Portugal seemed to reject PRR parties, reminiscent of long-lasting right-wing dictatorships under Francisco Franco and António Salazar. Between 2018 and 2019 the so-called ‘Iberian exceptionalism’ ended with VOX and Chega breaking through the Iberian political system and getting their representatives elected. This marked a watershed moment in Portuguese and Spanish democratic history, generating a series of questions about what made this unprecedented electoral breakthrough possible. A well-established strand of literature has been studying the electorate of PRR parties, and our aim was to establish whether the support for VOX and Chega follows a similar pattern. Using online survey data from the 2019 legislative elections in Spain and Portugal, we run country-wise regression models to determine how different sets of variables affect respondents’ vote choice as well as probabilities to vote (PTV) for VOX and Chega.

The results of this analysis indicate that on the one hand Chega and VOX attract voters with expected characteristics, while on the other hand their support also shows some peculiar traits. Concerning socio-demographic elements, those more likely to vote for VOX and Chega follow a pattern in line with previous studies on PRR parties: they are young, highly religious men with low education, and in the case of Chega, they live in rural areas. The fact that PRR parties in Spain and Portugal attract young voters might have a long-term impact and suggests that VOX and Chega do not simply attract old-style voters, nostalgic of the authoritarian regimes of Franco and Salazar, but a more modern electorate.

Political dissatisfaction is, as expected, a strong predictor of support for the two PRR parties, although corruption perception is not a driving reason.Footnote15 Also, VOX voters interestingly are only dissatisfied with their current PSOE government, but not with the previous PP administration. This might indicate that many of those who used to vote for the PP switched to VOX or are at least considering it. In addition, their media diet is in line with the expectations generated by the relevant literature: those more likely to vote for Chega and VOX use Facebook and tabloids as sources of political information. Additionally, VOX supporters are more likely to use online forums as a source of political information, but less likely to use Twitter. Finally, in line with other PRR parties, VOX and Chega voters can also be qualified as cultural globalization losers: they are driven by anti-globalization, and anti-immigration feelings, and —although only in in the case of VOX and not Chega— reject feminism.Footnote16

Interestingly, however, we also found that support for VOX and Chega does not follow the script in every regard, thus suggesting that the end of Iberian exceptionalism might be partially linked to country-specific reasons and not only to a generic wave of support for PRR parties that is characterizing most countries in Europe and across the world (Mudde Citation2019). For example, it is impossible to classify those more likely to vote for Chega and VOX as obvious economic ‘losers of globalization’: while they do believe that the general economic situation is worsening, their personal economic situation is not affected. To the contrary, those supporting VOX cannot be classified as poor by any means; in fact, their income and assets are clearly above average, supporting findings by Turnbull-Dugarte et al. (Citation2020). While Chega voters actually do show below-average assets, but still seem unaffected by personal economic circumstances. In sum, our evidence does not clearly support the hypothesis that economic hardship drives the vote for PRR parties, and rather points to the cultural dimension of globalization skepticism, as well as to the strong influence of education. This is in line with recent studies claiming that middle-income and high-status groups also vote for PRR parties because anxiety about losing subjective social status proves to be more important than actual decline (Engler and Weisstanner Citation2020), and pointing to the important role of education in PRR support (Bornschier Citation2018). Overall, we do not find empirical support for the idea that the radical right attracts economic globalization losers, while the cultural dimension of globalization is definitely linked to the support for PRR parties. Whether this is specific to the two Iberian countries, or a general European trend, should be the object of future research.

Another interesting characteristic about the support for VOX and Chega is their position on very salient issues in the respective countries, confirming that voter profiles are context dependent (Burbank Citation1997) and that the support for PRR parties partially depends on contextual factors (Muis and Immerzeel Citation2017b). Being against Catalonia’s independence and in favour of the centralization of the state excellently predicts support for VOX. Since this was the most salient issue at the time of the 2019 elections, it is possible to argue that it can explain not only the end of ‘Spanish exceptionalism’ but also the much bigger success enjoyed by VOX compared to Chega. In Portugal, the most salient issue lies on the socio-economic axis of competition: public services and the welfare system. While we show that support for Chega is indeed linked to a preference of privatization over public services, one could argue that welfare is comparatively less salient than the Catalan issue and does not polarize the public debate and the party landscape to the same degree. Together with the fact that VOX, but not Chega, capitalizes on strong anti-feminism feelings, this could explain the sharp differences in the electoral success of the two parties.

This study has several limitations that need to be highlighted. First, there are factors that would deserve to be considered in order to offer a more comprehensive explanation, but that go beyond the scope of this study. For example, future research should consider the role of stigmatization of the authoritarian past and its impact on the electoral breakthrough of Chega and VOX. Interestingly, in both Spain and Portugal there is a strong evidence of the so-called antidictator bias, which brings people as well as parties to self-identify as left-wing because of the stigma associated with the past authoritarian regime (Dinas and Northmore-Ball Citation2020). For this reason, right-wing parties in Portugal and Spain have been constantly treated by their electorates as the most right-wing in Europe, despite these parties holding relatively moderate positions according to their manifestos (Dinas Citation2017). Future studies should investigate whether the stigmatization of the authoritarian past is fading in both countries with a similar timing, opening up opportunity structures for the success of PRR parties (Manucci Citation2020).

Moreover, we focused on demand-side factors and did not analyze supply-side factors. Future studies might therefore explore the role of the media in legitimizing PRR parties in Spain and Portugal, which is certainly a relevant opportunity structure for PRR parties (Ernst, Esser, et al. Citation2019). Another direction for future research is the role of charismatic leadership, given that populists are more likely than other candidates to exhibit traits that are associated with it (Nai and Martínez i Coma Citation2019). We also lacked items to measure nationalism as well as populist attitudes, which recent studies confirm being present in both Spain and Portugal (Marcos-Marne, Plaza-Colodro and Freyburg Citation2020; Santana-Pereira and Cancela Citation2021).

In sum, our findings imply that VOX’s and Chega’s electorates follow patterns that are largely in line with what the literature on PRR parties predicts, but with two important caveats concerning the necessity to distinguish between economic and cultural ‘losers of globalization’, and the relevance of salient topics in the public debate that can transfer votes from the mainstream to the radical right. These results contribute to the literature on populist and radical right parties beyond the Iberian countries in two ways. First, our results indirectly illuminate the different electoral performance of the two parties suggesting that the saliency of different topics in the public debate matter: it is true that VOX exists since 2013 and had a more established voter base by 2019 than Chega, but crucially Chega, contrary to VOX, could not (yet?) exploit a very salient and polarized issue like the national unity in Spain, and thus remains electorally weaker. Second, our results show that PRR parties in Spain and Portugal do not attract economic losers of globalization, suggesting that the success of PRR parties depends on their ability to connect voters with cultural grievances over immigration to the group of voters with economic grievances over immigration (Halikiopoulou and Vlandas Citation2020). The Iberian exceptionalism came to an end, but PRR parties might fail to establish themselves after their initial breakthrough for very ‘Iberian’ reasons. Those who voted VOX might choose to support the mainstream PP in case it takes a more decisive position about Catalonia, and Chega will thrive only if the public debate will revolve around highly salient cultural rather than socio-economic issues as in the rest of the continent.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (37.7 KB)Acknowledgements

This article results from data collected and research undertaken in the MAPLE project (ERC-Consolidator Grant, 682125) as well as the POPULUS project (financed by the FCT, PDTC/SOC-OC/28524/2017). We are grateful to the participants of the SPARC seminar at the ICS-ULisboa for their valuable feedback on this project, especially to Marina Costa Lobo, Pedro Magelhães, Enrico Borghetto, Mariana Mendes, Stuart Turnbull-Dugarte and Steven Van Hauwaert. We are also grateful to the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Ireland, Luxembourg, and Malta might be the only remaining countries in Europe that did not experience the electoral breakthrough of PRR parties.

2 The electoral success of VOX might have constituted an advantage for Chega’s breakthrough, whose voters received signals of electoral viability from a party that is ideologically very close. This is in line with recent studies that propose a model based on the transnational and interdependent diffusion of far right parties and voters (Kuyper and Moffit Citation2019; Van Hauwaert Citation2019). However, the direct contacts between the two parties have been unsystematic, also because they belong to different European groups, and until now (September 2021) the two leaders never had an official meeting.

3 The success of any political party is linked, at least to some extent, to specific or peculiar elements. At the same time, as it will be clarified below, theories and empirical studies allow to identify demand-side explanations for the success of PRR parties that are generalizable.

4 Other datasets based on expert surveys (Meijers and Zaslove Citation2020; Norris Citation2020) consider VOX as a PRR party, but do not have data available for Chega yet, which is however described as populist and extreme right by Fernandes and Magalhães (Citation2020). The only book entirely devoted to VOX (Rama et al. Citation2021) considers it a PRR party, and a recent study concludes that populism in VOX is present although subordinated to nationalist and traditionalist elements (Marcos-Marne, Plaza-Colodro and O’Flynn Citation2021). While a binary classification of parties ignores possible nuances, we are confident that VOX and Chega can be defined as PRR parties.

5 A video from 2018 in which VOX warned against the potential dangers of Islam caused much controversy, conjuring a future in which Muslims had imposed sharia in southern Spain, turning the Cathedral of Córdoba back into a mosque and forcing women to cover up. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Chega’s leader Ventura took the opportunity to define Roma people as a threat to public health, proposing a plan based on confinement and surveillance for Roma communities.

6 At the 2020 Chega convention, the party leader André Ventura tried to pass a motion calling for the removal of ovaries from women who have abortions.

7 Men vote for PRR parties more than women because of gender differences regarding socio-economic position and lower perceptions regarding the threat of immigrants, as well as differences in socialization and populist attitudes (Spierings and Zaslove Citation2017; Harteveld and Ivarsflaten Citation2018).

8 Studies indicate both old (Lubbers, Gijsberts and Scheepers Citation2002) and young people (Arzheimer Citation2012) as those more likely to vote for PRR parties, but also the youngest and oldest citizens (Arzheimer and Carter Citation2006), while a meta-analysis shows the relationship is complex and situational (Stockemer, Lentz and Mayer Citation2018). We expect younger voters to support VOX and Chega for two reasons. First, younger voters are less likely to have formed party attachments and this increases the likelihood that they will vote for newer parties such as VOX and Chega (Tillman Citation2021). Second, young people tend to vote for PRR parties when the job market is less promising and more precarious for their cohort (Zagórski, Rama and Cordero Citation2021) and because young voters are less biased against PRR parties given the fading stigmatization of the authoritarian past (Dinas Citation2017).

9 We are aware that religiosity does not explain voting for PRR parties in every context (Lubbers, Gijsberts and Scheepers Citation2002; Norris Citation2005). However, given the relatively high levels of religiosity in Spain and Portugal, and in line with the existing studies on VOX (Turnbull-Dugarte, Rama and Santana Citation2020; Rama et al. Citation2021) we expect VOX and Chega to attract religious voters.

10 Non-urban areas usually show higher unemployment rates, lower education and income levels, and lower shares of immigrants.

11 See table A3 in the online appendix for more information on the survey, and table A6 for a representativeness analysis of the online survey data. Table A6 compares the fit of the survey’s unweighted sociodemographic distribution with population benchmarks and adds the same information for two standard face-to-face surveys, the ESS and the EB, from the same year. Our online survey is significantly more representative than both face-to-face surveys, especially when it comes to age and education.

12 Abstention, null and blank vote are coded as missing in order to compare PRR voters only to those respondents who made a valid vote choice.

13 In addition to the direct effect, we also tested for a curvilinear effect of both age and education but did not find any evidence for either.

14 This low significance might be due to a very low variance on the corruption variable: most respondents tend to believe that parties are corrupt.

15 Given the repeated corruption scandals that plagued the political systems of both countries, and particularly Spain, this finding is surprising. Our results seems to confirm studies that consider the politicization of corruption an element which is not unique to PRR parties (Engler Citation2020). Moreover, as already explained, the lack of statistical significance might be due to the fact that voters of most parties think corruption is widespread.

16 The difference between VOX and Chega could be linked to two factors: first, as explained in the data section, the questions used in the countries are different (acceptability of violence against women in Spain, and rejecting the right to abortion in Portugal), and second, anti-feminism might be more salient for VOX and less relevant for Chega.

References

- Alonso, S., and C. Rovira Kaltwasser. 2015. “Spain: No Country for the Populist Radical Right?” South European Society and Politics 20 (1): 21–45.

- Arzheimer, K. 2012. “Electoral Sociology: Who Votes for the Extreme Right and Why – and When?” In The Extreme Right in Europe. Current Trends and Perspectives, edited by U. Backes, and P. Moreau, 35–50. Göttingen: Vendenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Arzheimer, K., and E. Carter. 2006. “Political Opportunity Structures and Right-Wing Extremist Party Success.” European Journal of Political Research 45 (3): 419–443.

- Arzheimer, K., and E. Carter. 2009. “Christian Religiosity and Voting for West European Radical Right Parties.” West European Politics 32 (5): 985–1011.

- Bågenholm, A., and N. Charron. 2014. “Do Politics in Europe Benefit from Politicising Corruption?” West European Politics 37 (5): 903–931.

- Bernardez-Rodal, A., P. Requeijo Rey, and Y. G. Franco. 2020. “Radical Right Parties and Anti-Feminist Speech on Instagram: Vox and the 2019 Spanish General Election.” Party Politics, doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820968839 .

- Betz, H.-G. 1994. Radical Right-Wing Populism in Western Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Betz, H.-G. 2002. “Conditions Favouring the Success and Failure of Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Contemporary Democracies.” In Democracies and the Populist Challenge, edited by Y. Mény, and Y. Surel, 197–213. New York: Palgrave.

- Bornschier, S. 2010. “The New Cultural Divide and the Two-Dimensional Political Space in Western Europe.” West European Politics 33 (3): 419–444.

- Bornschier, S. 2018. “Globalization, Cleavages, and the Radical Right.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, edited by Jens Rydgren, 212–238. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bowler, S., et al. 2017. “Right-wing Populist Party Supporters: Dissatisfied but not Direct Democrats.” European Journal of Political Research 56 (1): 70–91.

- Brady, H. E., S. Verba, and K. L. Schlozman. 1995. “Beyond SES: A Resource Model of Political Participation.” American Political Science Review 89 (2): 271–294.

- Burbank, M. J. 1997. “Explaining Contextual Effects on Vote Choice.” Political Behavoir 19 (2): 113–132.

- Chega. 2019. “Programa Político.” https://partidochega.pt/programa-politico-2019/.

- da Silva, F. C., and S. Salgado. 2018. “Why no Populism in Portugal?” In Changing Societies: Legacies and Challenges. Vol. ii. Citizenship in Crisis, edited by M. C. Lobo, F. C. da Silva, and J. P. Zúquete, 249–268. Lisbon: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais.

- Dassonneville, R., et al. 2020. “The Effects of Survey Mode and Sampling in Belgian Election Studies: A Comparison of a National Probability Face-to-Face Survey and a Nonprobability Internet Survey.” Acta Politica 55 (2): 175–198.

- De Lange, S. L. 2007. “A new Winning Formula? The Programmatic Appeal of the Radical Right.” Party Politics 13 (4): 411–435.

- De Lange, S. L., and M. Rooduijn. 2015. “Contemporary Populism, the Agrarian and the Rural in Central Eastern and Western Europe Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.” In Rural Protest Groups and Populist Political Parties, edited by D. Strijker, G. Voerman, and I. J. Terluin, 163–190. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

- Dinas, E. 2017. “Political Socialisation and Regime Change: How the Right Ceased to be Wrong in Post-1974 Greece.” Political Studies 65 (4): 1000–1020.

- Dinas, E., and K. Northmore-Ball. 2020. “The Ideological Shadow of Authoritarianism.” Comparative Political Studies 53 (12): 1957–1991.

- Eatwell, R. 2003. “Ten Theories of the Extreme Right.” In Right-Wing Extremism in the Twenty-First Century, edited by P. Merkl, and L. Weinberg, 45–70. London: Cass.

- Elchardus, M., and B. Spruyt. 2016. “Populism, Persistent Republicanism and Declinism: An Empirical Analysis of Populism as a Thin Ideology.” Government and Opposition 51 (1): 111–133.

- Engesser, S., et al. 2017. “‘Populism and Social Media: how Politicians Spread a Fragmented Ideology.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (8): 1109–1126.

- Engler, S. 2020. ““Fighting Corruption” or “Fighting the Corrupt Elite”? Politicizing Corruption Within and Beyond the Populist Divide.” Democratization 27 (4): 643–661.

- Engler, S., and D. Weisstanner. 2020. “The Threat of Social Decline: Income Inequality and Radical Right Support.” Journal of European Public Policy 28 (1): 153–173.

- Ernst, N., et al. 2017. “‘Extreme Parties and Populism: An Analysis of Facebook and Twitter Across six Countries.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (9): 1347–1364.

- Ernst, N., and S. Blassnig, et al. 2019. “Populists Prefer Social Media Over Talk Shows: An Analysis of Populist Messages and Stylistic Elements Across Six Countries.” Social Media + Society 5 (1): 1–14.

- Ernst, N., and F. Esser, et al. 2019. “Favorable Opportunity Structures for Populist Communication: Comparing Different Types of Politicians and Issues in Social Media, Television and the Press.” International Journal of Press/Politics 24 (2): 165–188.

- Esser, F. 2013. “Mediatization as a Challenge: Media Logic Vs Political Logic.” In Democracy in the Age of Globalization and Mediatization. Challenges to Democracy in the 21st Century, edited by H. Kriesi, et al, 155–176. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fawzi, N. 2019. “Untrustworthy News and the Media as “Enemy of the People?” How a Populist Worldview Shapes Recipients’ Attitudes Toward the Media.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 24 (2): 146–164.

- Fernandes, J. M., and P. C. Magalhães. 2020. “The 2019 Portuguese General Elections.” West European Politics 43 (4): 1038–1050.

- Ferreira, C. 2019. “Vox Como Representante de la Derecha Radical en España: un Estudio Sobre su Ideología.” Revista Española de Ciencia Política 51: 73–98.

- Ferreira da Silva, F., and M. Mendes. 2019. “Portugal – A Tale of Apparent Stability and Surreptitious Transformation.” In European Party Politics in Times of Crisis, edited by S. Hutter, and H. Kriesi, 139–164. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fieschi, C., and P. Heywood. 2004. “Trust, Cynicism and Populist Anti-Politics.” Journal of Political Ideologies 9 (3): 289–309.

- Gidron, N., and P. A. Hall. 2020. “Populism as a Problem of Social Integration.” Comparative Political Studies 53 (7): 1027–1059.

- Golder, M. 2016. “Far Right Parties in Europe.” Annual Review of Political Science 19: 477–497.

- Gómez-Reino, M., and C. Plaza-Colodro. 2018. “Populist Euroscepticism in Iberian Party Systems.” Politics 38 (3): 344–360.

- Grande, E., T. Schwarzböz, and M. Fatke. 2019. “Politicizing Immigration in Western Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (10): 1444–1463.

- Halikiopoulou, D., and T. Vlandas. 2020. “When Economic and Cultural Interests Align: The Anti-Immigration Voter Coalitions Driving far Right Party Success in Europe.” European Political Science Review 12 (4): 427–448.

- Hameleers, M., L. Bos, and C. de Vreese. 2017. ““They Did It”: The Effects of Emotionalized Blame Attribution in Populist Communication.” Communication Research 44 (6): 870–900.

- Harteveld, E., et al. 2015. “The Gender Gap in Populist Radical-Right Voting: Examining the Demand Side in Western and Eastern Europe.” Patterns of Prejudice 49 (1–2): 103–134.

- Harteveld, E., and E. Ivarsflaten. 2018. “Why Women Avoid the Radical Right: Internalized Norms and Party Reputations.” British Journal of Political Science 48 (2): 369–384.

- Helbling, M., and S. Jungkunz. 2020. “Social Divides in the age of Globalization.” West European Politics 43 (6): 1187–1210.

- Ignazi, P. 1992. “The Silent Counter-Revolution: Hypotheses on the Emergence of Extreme Right-Wing Parties in Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 22 (1): 3–34.

- Ignazi, P. 2003. Extreme Right Parties in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Inglehart, R. 1977. The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ivarsflaten, E., and R. Stubager. 2013. “Voting for the Populist Radical Right in Western Europe: The Role of Education.” In, ed. J. Rydgren, 122–137. Abingdon: Routledge.” In Class Politics and the Radical Right, edited by J. Rydgren, 122–137. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Kitschelt, H., and J. A. McGann. 1995. The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Kriesi, H., et al. 2008. West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kurer, T. 2020. “The Declining Middle: Occupational Change, Social Status, and the Populist Right.” Comparative Political Studies 53 (10): 1798–1835.

- Kuyper, J., and B. Moffit. 2019. “Transnational Populism, Democracy, and Representation: Pitfalls and Potentialities.” Global Justice: Theory Practice Rhetoric 12 (2): 27–49.

- Lipset, S. M., and S. Rokkan. 1967. Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York: The Free Press.

- Lubbers, M., M. Gijsberts, and P. Scheepers. 2002. “Extreme Right-Wing Voting in Western Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 41 (3): 345–378.

- Mair, P. 1998. “Representation and Participation in the Changing World of Party Politics.” European Review 6 (2): 161–174.

- Manucci, L. 2020. Populism and Collective Memory: Comparing Fascist Legacies in Western Europe. New York: Routledge.

- Marcos-Marne, H., C. Plaza-Colodro, and T. Freyburg. 2020. “Who Votes for new Parties? Economic Voting, Political Ideology and Populist Attitudes.” West European Politics 43 (1): 1–21.

- Marcos-Marne, H., C. Plaza-Colodro, and C. O’Flynn. 2021. “Populism and New Radical-right Parties: The Case of VOX.” Politics. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/02633957211019587 .

- Meijers, M. J., and A. Zaslove. 2020. “Measuring Populism in Political Parties: Appraisal of a New Approach.” Comparative Political Studies 54 (2): 372–407.

- Mendes, M., and J. Dennison. 2020. “Explaining the Emergence of the Radical Right in Spain and Portugal: Salience, Stigma and Supply.” West European Politics 44 (4): 752–775.

- Minkenberg, M., and P. Perrineau. 2007. “The Radical Right in the European Elections 2004.” International Political Science Review 28 (1): 29–55.

- Mols, F., and J. Jetten. 2017. The Wealth Paradox: Economic Prosperity and the Hardening of Attitudes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Morlino, L. 1998. Democracy Between Consolidation and Crisis: Parties, Groups, and Citizens in Southern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mudde, C. 2004. “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition 39 (4): 542–563.

- Mudde, C. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, C. 2019. The far Right Today. Cambridge: Polity.

- Mudde, C., and C. Rovira Kaltwasser. 2018. “Studying Populism in Comparative Perspective: Reflections on the Contemporary and Future Research Agenda.” Comparative Political Studies 51 (13): 1667–1693.

- Muis, J., and T. Immerzeel. 2017a. “Causes and Consequences of the Rise of Populist Radical Right Parties and Movements in Europe.” Current Sociology Review 65 (6): 909–930.

- Muis, J., and T. Immerzeel. 2017b. “Causes and Consequences of the Rise of Populist Radical Right Parties and Movements in Europe.” Current Sociology Review 65 (6): 909–930.

- Müller, P., and A. Schulz. 2019. “Alternative Media for a Populist Audience? Exploring Political and Media use Predictors of Exposure to Breitbart, Sputnik, and Co.” Information, Communication & Society 24 (2): 277–293.

- Nai, A., and F. Martínez i Coma. 2019. “The Personality of Populists: Provocateurs, Charismatic Leaders, or Drunken Dinner Guests?” West European Politics 42 (7): 1337–1367.

- Norris, P. 2005. Radical Right: Voters and Parties in the Electoral Market. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Norris, P. 2020. “Measuring Populism Worldwide.” Party Politics 26 (6): 697–717.

- Ortiz Barquero, P. 2019. “The Electoral Breakthrough of the Radical Right in Spain: Correlates of Electoral Support for VOX in Andalusia (2018).” Genealogy 3 (4): 189–202.

- Pop-Eleches, G. 2010. “Throwing Out the Bums: Protest Voting and Unorthodox Parties After Communism.” World Politics 62 (2): 221–260.

- Rama, J., et al. 2021. VOX: The Rise of the Spanish Populist Radical Right. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Ribera Payá, P., and J. I. Díaz Martínez. 2020. “The end of the Spanish Exception: The far Right in the Spanish Parliament.” European Politics and Society, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2020.1793513 .

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2018. “The Revenge of the Places That Don’t Matter (and What to do About it).” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (1): 189–209.

- Rodríguez-Teruel, J. 2021. ‘Polarisation and Electoral Realignment: The Case of the Right-Wing Parties in Spain’, South European Society and Politics. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2021.1901386 .

- Rooduijn, M. 2018. “What Unites the Voter Bases of Populist Parties? Comparing the Electorates of 15 Populist Parties.” European Political Science Review 10 (3): 351–368.

- Rooduijn, M., et al. 2020. The PopuList: An Overview of Populist, Far Right, Far Left and Eurosceptic Parties in Europe. Available at: www.popu-list.org.

- Rooduijn, M., and B. Burgoon. 2018. “The Paradox of Well- Being: Do Unfavorable Socioeconomic and Sociocultural Contexts Deepen or Dampen Radical Left and Right Voting Among the Less Well-Off?” Comparative Political Studies 51 (13): 1720–1753.

- Rooduijn, M., W. Van der Brug, and S. L. de Lange. 2016. “Expressing or Fuelling Discontent? The Relationship Between Populist Voting and Political Discontent.” Electoral Studies 43: 32–40.

- Rydgren, J. 2007. “The Sociology of the Radical Right.” Annual Review of Sociology 33 (1): 241–262.

- Santana-Pereira, J., and J. Cancela. 2021. “Demand Without Supply? Populist Attitudes and Voting Behaviour in Post-Bailout Portugal.” South European Society and Politics 25 (2): 205–228.

- Sauer, B. 2020. “Authoritarian Right-Wing Populism as Masculinist Identity Politics. The Role of Affects.” In Right-Wing Populism and Gender. European Perspectives and Beyond, edited by G. Dietze, and J. Roth, 23–40. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

- Spierings, N., and A. Zaslove. 2017. “Gender, Populist Attitudes, and Voting: Explaining the Gender gap in Voting for Populist Radical Right and Populist Radical Left Parties.” West European Politics 40 (4): 821–847.

- Spruyt, B., G. Keppens, and F. Van Droogenbroeck. 2016. “Who Supports Populism and What Attracts People to It?” Political Research Quarterly 69 (2), doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912916639138 .

- Stockemer, D., T. Lentz, and D. Mayer. 2018. “Individual Predictors of the Radical Right-Wing Vote in Europe: A Meta-Analysis of Articles in Peer-Reviewed Journals.” Government and Opposition 53 (1): 569–593.

- Strömbäck, J. 2008. “Four Phases of Mediatization: An Analysis of the Mediatization of Politics.” International Journal of Press/Politics 13 (3): 228–224.

- Teney, C., O. P. Lacewell, and P. De Wilde. 2014. “Winners and Losers of Globalization in Europe: Attitudes and Ideologies.” European Political Science Review 6 (4): 575–595.

- Tillman, E. R. 2021. Authoritarianism and the Evolution of West European Electoral Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tsfati, Y. 2010. “Online News Exposure and Trust in the Mainstream Media: Exploring Possible Associations.” American Behavioral Scientist 54 (1): 22–42.

- Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J. 2019. “Explaining the end of Spanish Exceptionalism and Electoral Support for Vox.” Research and Politics 6 (2): 1–8.

- Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J., J. Rama, and A. Santana. 2020. “The Baskerville’s dog Suddenly Started Barking: Voting for VOX in the 2019 Spanish General Elections.” Political Research Exchange 2 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/2474736X.2020.1781543.

- Vampa, D. 2020. “Competing Forms of Populism and Territorial Politics: The Cases of Vox and Podemos in Spain.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 28 (3): 304–321.

- Van Hauwaert, S. M. 2019. “On far Right Parties, Master Frames and Trans-National Diffusion: Understanding far Right Party Development in Western Europe.” Comparative European Politics 17: 132–154.

- van Hauwaert, S., and S. van Kessel. 2018. “Beyond Protest and Discontent. A Cross-National Analysis of the Effect of Populist Attitudes and Issue Positions on Populist Party Support.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (1): 68–92.

- van Kessel, S., J. Sajuria, and S. van Hauwaert. 2020. “Informed, Uninformed or Misinformed? A Cross-National Analysis of Populist Party Supporters Across European Democracies.” West European Politics 44 (3): 585–610.

- Zagórski, P., J. Rama, and G. Cordero. 2021. “Young and Temporary: Youth Employment Insecurity and Support for Right-Wing Populist Parties in Europe.” Government and Opposition 56 (3): 405–426.

- Zulianello, M., A. Albertini, and D. Ceccobelli. 2018. “A Populist Zeitgeist? The Communication Strategies of Western and Latin American Political Leaders on Facebook.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 23 (4): 439–457.

- Zúquete, J. P. 2017. “Populism and Religion.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, edited by C. Rovira Kaltwasser, et al, 445–466. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Appendix

Table A1. Explaining the probability to vote for VOX and Chega (full models to figures 2–6, left panel).

Table A2. Explaining the vote choice for VOX and Chega (full models to figures 2–6, right panel).