ABSTRACT

Differentiated integration (DI) in the European Union has recently attracted considerable scholarly and political attention. Yet, we know rather little about where scholars’ normative support of DI begins and where it ends, and whether there is scholarly consensus about which type of DI warrants support. This contribution addresses which type of DI scholars support, and which policy areas should be exempt. It explores these questions by means of a novel expert survey (n = 95). Three broad observations can be made. First, whilst support for DI is strong in the abstract, it becomes much weaker when empirically applied. Second, the high levels of support are not necessarily in tune with the perceived risks of DI. Third, there is a fair amount of expert disagreement around DI. We defend the view that the type of disagreement we see in the findings is valid and substantively relevant because it highlights genuine diffusion (as opposed to conceptual confusion) in the distribution of preferences among experts that has previously been largely obscured. The article thereby also makes a contribution to the literature on expert surveys, discussing the distinction between benchmarking and non-benchmarking expert surveys, and the legitimacy of expert disagreement.

Introduction

Since the 2010s, scholars have increasingly addressed the issue of differentiated integration (DI) in the European Union (EU). DI allows some member states to opt out of, or be exempted or excluded from, participation in certain existing EU policies, and other member states to cooperate in new policy areas and integrate further than some may be willing or able to do. The result is that not all policies and standards apply uniformly across the EU (Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2020). A reaction to increased diversity after Eastern enlargements, on the one hand, and increased levels of Euroscepticism, on the other, DI offers the prospect of a more flexible Europe (Bellamy, Kröger, and Lorimer Citation2022), capable of combining the demand for unity advocated by supporters of greater integration with the on-going claims for the recognition of diversity insisted on by its critics. This article sets out to explore the levels of support for DI among academic experts.

Recent scholarship on DI has focused on its conceptualization and empirical mapping (Schimmelfennig, Leuffen, and Rittberger Citation2015; Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2020) whereas normative analysis remains scarce (with a few exceptions, see Bellamy, Kröger, and Lorimer Citation2022; Eriksen Citation2018; Lord Citation2021). Because of the descriptive and explanatory focus of the literature, we know very little about where scholars’ own support for DI begins and ends, and whether there is a scholarly consensus on which type of DI warrants support. This is where the present contribution steps in. It addresses a number of key questions: which type of DI do scholars consider legitimate? Do capacity and sovereignty DI, which serve different purposes, enjoy different degrees of support?Footnote1 Which policy areas do experts consider should be exempt from DI, if any? Do all experts keep with the EU mantra that the Single Market is indivisible? What about democratic backsliding by means of DI? This article sets out to answer these questions by means of a novel expert survey (n = 95).

Why does it matter how academics answer these questions? The normative assessments of academics (not just of DI) standardly remain in the dark (normative contributions apart), either because (empirical) scholars do their best to hide their personal normative preferences in their academic contributions, or because policy advice is usually given in closed settings.Footnote2 However, both contexts – academic and policy-making – would benefit from an improved understanding of what experts think of DI. As regards the former, whilst there now is an abundant literature on DI, it is by and large conceptual and explanatory and does not tell us much about the more normative assessments scholars might have of DI. By contrast, the findings of the present survey help us to identify which types of DI experts support. Identifying the levels of support for specific types of DI within the expert community in turn helps to detect potential disagreements amongst experts as to which kinds of DI, if any, they support.

As regards policy-making, two parallel developments make the assessment of experts’ views of DI particularly important. On the one hand, the salience of DI has increased ever since the Maastricht Treaty and the breakdown of the ‘permissive consensus’ (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009), as indicated by the increasing acceptance of DI, both within the European Commission (Citation2017) and amongst leading politicians. The war in Ukraine and related enlargement ambitions have only served to reinforce talk about a multi-layered EU. In such a political context, one would want to know what experts think of DI, and where their support of DI ends.

On the other hand, academics are increasingly requested to demonstrate the ‘impact’ of their research, implying an increased pressure to reach out to policy-makers so as to try and influence them in one way or another. Furthermore, policy-makers, not least in the European Commission, are ever more dependent on scholarly expertise, given the rising complexity of policy problems as well as the lack of in-house expertise. Indeed, recent research shows that EU scholarship does find its way into the policy-making process, and that 72% of Commission officials draw on EU scholarship to ‘improve their work’s quality, boost its credibility internally and with the EP and Council, and justify it publicly’ (Duina Citation2021, 4). It is in this broader context that policy-makers as much as the academic community needs a better understanding of the normative underpinnings of experts’ views of DI. Do the views of those who seek to influence policies to reflect an expert consensus or at least a majority in the scholarly community or is there widespread disagreement among scholars as to the advisability of DI? By means of this study, we find out how representative individual scholarly assessments of DI are of the wider expert community.Footnote3

In doing so, we are employing the expert survey method in a nonstandard, but not unprecedented, manner. Instead of using the expert survey as a benchmarking exercise for identifying an academic consensus on concepts or empirical data, we are employing it to explore the extent to which systematic agreements or divisions exist in experts' normative assessment of DI. We take this approach in order to draw out and clarify the collective preferences, priorities and correlations held by experts with regard to DI, which have hitherto been hidden. This research addresses an important gap in the literature and is relevant also insofar as it helps to avoid the emergence of a false or assumed consensus about the value of DI.

Our analysis has produced five main findings. First, experts are generally fairly positively minded towards institutional flexibility by means of DI. Second, amongst both supporters and opponents of a flexible Europe, the support for DI varies depending on whether experts look at capacity or sovereignty DI, with the former commanding more support than the latter. Third, there are different assessments of DI's benefits and risks both between and among supporters and opponents of DI. These differences particularly relate to their assessment of the different types of DI (capacity and sovereignty). Fourth, the large majority of experts consider that not all policy areas should be open to DI. Experts are particularly critical of DI in the areas of the Single Market, Fundamental Rights and the Rule of Law, though with marked differences between these areas. Fifth, a case study of the four demands Prime Minister David Cameron sought to negotiate before the Brexit referendum confirms the above trends. It showed how those experts who either consider capacity DI legitimate or oppose DI more generally are particularly likely to believe that the EU should reject future demands similar to those made by David Cameron in 2016. Interestingly, even amongst those who consider sovereignty DI highly legitimate and thought that DI should be possible in any policy area, a high percentage agreed that such demands should be rejected in the future.

All in all, three broader observations can be made. First, whilst support for DI is strong in the abstract, it becomes much weaker when applied to more concrete questions and cases. Second, the high levels of support are not necessarily in tune with the perceived risks of DI. Third, there is a fair amount of expert disagreement around DI. Whilst some might see this as problematic, we will defend the view that the type of disagreement we see in the findings is valid and substantively relevant because it highlights genuine diffusion (as opposed to conceptual confusion) in the distribution of preferences among experts that has previously been largely obscured.

The paper proceeds as follows. The first section lays the conceptual foundations of the analysis. The second section describes the method and data set. This will involve a review of the added value of an expert survey such as this, a discussion of questions of reliability and validity as well as the description of our data set. The third section displays the findings of the expert survey. We will move from more general questions related to DI, its different types and the policy areas in which experts consider it should not take place, to a more specific study of the types of exemptions David Cameron sought for the UK prior to the membership referendum in 2016 and what our experts thought of their acceptability. The fourth section discusses the findings, not least the disagreement found between experts. The final section wraps up and indicates avenues for future research.

The potential boundaries of differentiated integration

We begin this section by reviewing normative appreciations of legal fragmentation. We then introduce the distinction between capacity and sovereignty DI, which is crucial for the analysis. As regards policy areas that might constitute a red line for experts so far as their support for DI is concerned, we look at the Single Market and why it has been considered indivisible, as well as respect for fundamental values as expressed in Article 2 of the Treaty of the European Union.

This is not the place to look into the benefits and risks of DI in great detail ( Kröger and Loughran Citation2022; Leruth, Gänzle, and Trondal Citation2019). Suffice it to say that in the limited normative appraisals that exist, its gains and drawbacks are contentious. On the positive side, many acknowledge that DI offers a means of reconciling continued integration with an ever more heterogeneous membership (Bellamy and Kröger Citation2017; Lord Citation2015) and call for a pragmatic approach to EU law that accommodates the dynamics of integration and disintegration within the EU legal order (Dehousse Citation2003). In a more heterogeneous EU, a multi-speed approach and some concentric circles or variable geometry allow member states to choose policies more aligned to their needs and preferences (Lord Citation2015). Likewise, it might make decision-making more efficient. On the negative side, critics fear it erodes solidarity between member states and constitutes a challenge to any prospect of developing the EU into a political community based on shared rights and obligations of membership. They argue that opt-outs undermine the legal unity and authority of the EU (Curtin Citation1993; Scott and de Búrca Citation2000) as well as the uniform composition of EU institutions. As a result, they worry it creates differentiated citizenship across the EU. Others worry about the possibility of domination, whereby participants in a policy area can make decisions that adversely impact on those excluded or exempted from it, without having to consult the preferences or interests of these outsiders (Eriksen Citation2018). Moreover, the contrary may also occur, whereby the domestic decisions of those outside a policy area arbitrarily undermine the decision-making of those inside it. In sum, not supporting a specific type of DI can be motivated by a number of concerns, such as legal fragmentation, reciprocity of rights, de facto domination and/or injustice, the erosion of values and norms, or concerns over the creation of divisions. However, whilst there are select instances of normative appraisal of ‘flexible Europe’ (Bellamy, Kröger, and Lorimer Citation2022), the large bulk of the literature is empirical and conceptual and seeks to avoid explicitly normative assessments of DI.

Not all the cases of DI are the same. DI can be of different nature – temporary or permanent – and driven by different factors. In the literature, the terminology that best captures these differences and that has been largely adopted by interested scholars distinguishes between capacity and sovereignty DI (Winzen Citation2016).Footnote4 Capacity DI is mainly ‘motivated by efficiency and distributional concerns’ linked to EU enlargements (Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2014, 355). It occurs when either existing member states temporarily exclude new member states from certain policy areas because they ‘fear economic and financial losses as a result of market integration with the new member states, the redistribution of EU funds or weak implementation capacity’ (Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2014, 361); or new member states seek to be exempted temporarily from integration in a given area and be granted more time to adapt to EU rules and market pressures. In such constellations, DI is seen as a temporary and transitional measure that ideally aids both sides.

By contrast, sovereignty DI tends to be permanent and occurs most commonly when competences in core state powers are transferred to the EU in the context of treaty revisions, and a government successfully negotiates a Treaty opt-out of a policy transfer due to constitutional and/or identity issues (see Winzen Citation2016). These issues may reflect ideological or pragmatic preferences by certain political actors, as when governments of largely Eurosceptic countries, which either are ideologically opposed to further integration or fear domestic opposition to it, seek a permanent or temporary opt-out. However, they may also reflect deeper cultural and political differences in core areas about which a government or citizens feel strongly, such as those related to marriage and divorce, abortion and euthanasia, or the use of stem cell research. In such areas, some governments may be reluctant to integrate a policy and seek to opt out if it is integrated, so as to protect the predominant cultural values of their citizens. Or sovereignty DI may result from diverging views about how much political integration is desirable. In other words, sovereignty DI is usually guided by the perception of a member state’s government that in these areas the EU is ‘the inferior legislator’ (Winzen Citation2016, 103).

Capacity DI has been linked to the idea of a ‘multi-speed’ Europe. On this account, though some states may integrate faster than others, all are assumed to eventually integrate to the same extent. By contrast, sovereignty DI has been allied to a Europe of ‘concentric circles’ or ‘variable geometry’, whereby different geographic areas have different levels of integration (for an overview, see Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2020). Whilst the vocabulary of capacity (instrumental) and sovereignty (constitutional) DI is well established in the interested literature, we do not know how strongly scholars support either of these forms of DI, and our study aims at clarifying precisely that.

Historically, capacity DI has related to secondary law whereas sovereignty DI relates to primary law and requires Treaty opt-outs. In other words, the EU makes it harder to achieve opt-outs from its core policies such as the Single Market, the Euro or Schengen. Whereas opt-outs of the Euro and of Schengen have been achieved by a number of member states, the Single Market has so far been treated as non-negotiable by the EU. This makes it a good case to explore the limits of acceptability of DI amongst experts.

So why does the EU insist on the indivisibility of the four freedoms that constitute the Single Market? The core of the answer to this question is that EU law governs the relationship between states and persons, and that partial participation in it raises normative problems. EU Single Market law establishes equal rights for the contracting states’ nationals and corresponding duties for the contracting states. As a result, contracting states’ nationals have equal market rights and cannot be discriminated against on the basis of nationality or residence (Weiss and Blockmans Citation2016, 9). If there was a differentiation in Single Market law, the distribution of market rights would no longer be the same for all individuals but would vary with a person’s nationality and/or location, and this inequality in rights is deemed unjustifiable. Further to requiring law that regulates the relationship between Single Market states and Single Market nationals, the Single Market also requires both to be subjected to the same independent institutions that execute the law.

On this account, the reciprocity of Single Market rights that nationals enjoy across the participating states is crucial. Each member state agrees to grant nationals of each of the contracting states the exact same set of rights. In other words, if a national enjoys right A in its ‘home’ country (A), the same right must be granted to a national (B) from another participating state (B) in country A, and vice versa. This reciprocity of rights explains why states and their nationals feel comfortable signing up to the Single Market in the first place. It translates into a mutual trust that the related rights will be mutually available and enforceable, even in the absence of a state-like system of coercion:

In a “Community of law”, (…) law is respected because – and as long as – it is equally applied in all cases. (…) For every individual, the trust in the full respect of equally applicable terms of law by all the others justifies its own obedience. There cannot be privileges nor discrimination. It is ultimately the reciprocity of such mutual trust among citizens as much as among Member States which allows a legal system to function, at the national level as well as the European. (Pernice Citation2010, 40)

Preserving the integrity of the Single Market excludes participation based on a sector-by-sector approach. A non-member of the Union, that does not live up to the same obligations as a member, cannot have the same rights and enjoy the same benefits as a member. In this context, the European Council welcomes the recognition by the British Government that the four freedoms of the Single Market are indivisible and that there can be no “cherry picking”. (European Council Citation2017, 3)

The (lack of) consistent application of EU law across all the member states has also attracted increased political and academic attention in the context of a Rule of Law crisis referring to the nonobservance of Article 2 by some member states, notably Hungary and Poland. As is known and documented, these member states have actively engaged in democratic backsliding for a number of years, not least by insisting that there is no common model of democracy for all EU member states, and that taking a ‘differentiated’ path of democratic development was thus fully justified and in line with EU membership. The issue so far as DI is concerned is therefore whether there could be DI with regard to Article 2, thereby allowing these (and potentially other) states from diverging from EU law and undermining the independence of their courts and media, respect for fundamental rights, etc. (Bellamy and Kröger Citation2021; Kelemen Citation2019). The worry here is not only about the respect for these fundamental values and rights, but also that this could lead to EU law not being consistently and equitably applied across the EU. However, the consistent domestic observance of EU law is crucial given the EU’s limited financial and administrative resources, as without it the entire apparatus of the EU would break down. The EU depends on the implementation of its law by domestic courts and administrations to achieve its policies, and some member states not observing it will have immense knock-on effects on all member states, as rule-observing member states will begin to question the judgments of courts (in backsliding states) which are not independent. Trust will wane and mutual recognition, on which the EU is built, will cease (Kelemen Citation2019, 252). Given the centrality of the Rule of Law for the workings of the EU as a whole as well as the protection of its core norms, we will also include it in our analysis.

Method and data

Expert surveys

In order to establish the distribution of normative views of DI among experts, we employ an expert survey approach. The expert survey method is the most appropriate and efficient means for empirically exploring diffusion in the distribution of expert opinion, given that these sorts of appraisals tend to be hidden within the largely conceptual and explanatory academic literature on DI. While using expert surveys to explore disagreement (as well as consensus) within an expert community is a relatively nonstandard application of the method, we contend that it is a valid and relevant approach as it reflects genuine diversity in the preferences of experts rather than conceptual fuzziness. In the following, we defend this approach in more detail.

In political science, the standard rationale for utilizing an expert survey is that the positions of experts can be used to establish a consensus on an objective benchmark for the distribution of a latent concept. The most prominent example is the positioning of political parties within the abstract ideological space (Hooghe et al. Citation2010). This usually (although not exclusively) involves a focus on quantifying abstract supply side concepts that cannot be measured meaningfully using standard public opinion surveys because either the concepts require an in-depth expert understanding, or an objective assessment would be difficult or impossible to attain through other means (Benoit and Laver Citation2006; Castles and Mair Citation1984; Hooghe et al. Citation2010; Laver and Hunt Citation1992; Laver Citation1998; ). Assuming the conditions of objectivity among experts are met, these benchmarking exercises can be used to measure change over time (Benoit and Laver Citation2006). Another use of expert surveys, and one that has more in common with our aim as regards its focus on an obscured distribution of preferences, is to use them to establish an expert consensus on a topic that may be hidden to scholars due to its sensitive or restricted nature. For example, expert surveys are often used by scholars of International Relations to establish the likely intentions of hostile or repressed actors (Irvine Citation2017).

In our study, we are not concerned with using the expert survey method as a means of establishing a benchmark measure. We believe that it is more relevant for the academic and policy-making debate on DI to highlight disagreement within the expert community in order to avoid the danger of a false consensus becoming established. Our contention is that in a context where the debate regarding the normative value of DI is unsettled, exploring the distribution of preferences towards DI within the expert community is a valuable exercise in its own right and an efficient method of establishing the extent of these disagreements, not least because of experts’ influence in policy-making. In contrast to the standard rationale, our expert survey has been purposefully constructed to capture the diffuse distribution of preferences among experts as regards DI. In other words, the disagreement that we expect to find in our view reflects the lack of expert consensus in this area rather than a problematic measurement issue or source of systematic personal bias (Bakker et al. Citation2015; Budge Citation2000).

Some hold the view that expert disagreement by definition weakens the related survey (Benoit and Laver Citation2006, 9). We adopt a different take on this question. We consider that any expert survey is prone to different types of biases that cannot be eliminated fully through research design and can at best be acknowledged and reflected upon. This view rests on a specific epistemological position which leads to a different position about expert disagreement in expert surveys than conventional surveys convey.

As regards the creation of knowledge, there are a number of persistent sources of methodological disagreements (Hammond Citation1996). This is certainly not the place to address or discuss them in depth. Instead, we will merely clarify our own position on this point. We concur with those who consider that social science is impossible without value judgements (Jasanoff Citation1990; Taylor Citation1967). Indeed, any explanatory framework carries with it a ‘value slope’ (Taylor Citation1967, 569; see also Mumpower and Stewart Citation1996). We are not suggesting that this implies a crude, deliberate skewing of answers to fit one’s biases, but instead a more subtle role of bias in expert surveys and (political) science more generally, because of an inherent entangling of facts with values. As a result, disagreements amongst experts may not reflect different scientific or technical judgements about ‘what is’, but rather different conclusions about ‘what ought to be’. Particularly in a survey that addresses the normative views of experts on a given issue – here DI – it is extremely likely that the responses involve such value judgements. We do not consider this a problem to be eliminated. Instead, we are precisely interested in what those disagreements might be (not in why they are what they are).

In exploring expert disagreement, we draw on the work of Charles Taylor (Citation1967) regarding the role of expertise. Taylor argues that it is important to recognize that when expertise is invoked in either public or academic debate, it often tends towards two related pathologies. Firstly, that there is an assumption that expertise reflects an objective consensus among a community of experts whereas in reality established positions are often developed through intense technical and normative disagreement and hierarchical relationships within the expert community. Secondly, that expert communities, even when pursuing nominally objective methodologies and modes of thought, tend to maintain a set of normatively unquestioned underlying assumptions regarding what is considered as a valid lens to apply towards the object of study. Taylor argues that both of these tendencies are generally (and often deliberately) obscured and that for expertise to have a valid role it must be rendered transparent, particularly if there is a chance that it will have a direct impact beyond the expert community itself. Relatedly, our assumption is that there are genuine disagreements among the DI expert community and that the systematic nature of these disagreements has remained obscured. Our expert survey intends to systematically capture the diffusion of preferences within the expert community and thus render it transparent.

In summary, there are two reasons for using an expert survey to capture the normative views of experts on DI. First, it allows us to capture the distribution of the normative attitudes towards DI amongst the expert community and thus to establish the levels of agreement and disagreement amongst experts as regards DI. This is important not only to advance knowledge in the field, for which both agreement and disagreement are relevant, but also, because of the involvement of EU experts in policy-making (see Duina Citation2021). Second, it crystallizes the nature of the academic debate on DI in order to explore there is any kind of systematic relationship between underlying assumptions and preferences for certain types of policies.

Data set

The analysis in this article is based on an expert survey of 95 respondents from across the EU. For an expert survey, this is a large sample. The population of experts from which the sample is drawn comprises the members of three different EU-funded consortiums working on DI between 2020 and 2023 and cooperating in the context of the network structure ‘Differentiation: Communicating Excellence’Footnote5; as well as scholars who are not part of these consortiums, but have previously published on DI and were identified through google scholar searches including the term ‘differentiated integration’. They are mostly political scientists, but also include legal scholars and sociologists.

Are the experts we use appropriate witnesses to the phenomenon we seek to capture? As has been pointed out, there is no ‘single valid indicator of scientific expertise’ that has been established to convey expert judgements on policy problems (Mumpower and Stewart Citation1996, 193). In general, scholars will face a tradeoff between the level of expertise and the size of the informant pool (Maestas, Buttice, and Stone Citation2014), though even the best-informed experts can be victims of bias. Still, scholarly thinking seems to converge around the idea that potential individual bias is best corrected through the 'wisdom of crowds’, i.e. including a larger pool of informants. Crowds would produce a high level of accuracy even though some of the informants might have imperfect information (Surowiecki Citation2004). For this survey, we follow the advice of James Shanteau (Citation1992) and define experts to be those who are regarded as such by others within their field.

Demographic data and the personal ideological positions of the experts are not captured. As stated above, we are taking the position that expert surveys measure preferences based on a commitment to objective expertise within the expert community (Benoit and Laver Citation2006). The survey is not concerned with testing whether the expert views are biased in certain political or demographic directions. Instead, we are assuming that the divisions within the expert community we highlight are based on differing assessments of the normative value and impact of DI. The survey was initialized on 9 October 2020 and ran for two months, with several follow-up invitations sent out to the experts.Footnote6 The response rate was 68.3%.Footnote7

The survey addressed a range of normative aspects of DI (see below). It mainly contained closed questions that asked experts to rank their views of a specific aspect of DI on either a 10-point scale or a standard 5-point agree/disagree Likert scale. However, it also contained several open-ended questions which allowed experts to expand on the meaning of their answers and their specific definitions of DI in more depth. The survey contained 20 questions and was organized into five sectionsFootnote8:

General questions, which addressed experts’ views regarding the overall desirability of a flexible Europe and different types of DI, as well as on which policies should not be differentiated.

Benefits and risks – this section asked experts to rate items from a list of benefits of DI (and then a list of risks) that have been acknowledged in the academic literature on a 0–10 scale.

Democracy and differentiated integration – this section asked experts to rate the impact of DI on various aspects of democracy both between and within EU member states.

Brexit and DI – this section explored experts’ views on the relationship between Brexit and DI.

External differentiation – this section asked experts to express their views on the acceptability of different models of external DI.

Impact of DI – the final section asked experts to predict what the overall impact of DI on the EU was likely to be.

This paper focuses on analyzing the interaction between responses to the first, second and fourth sections of the above – general questions on types and areas of DI, views of risks and benefits, and on select Brexit questions.

The list of benefits and risks experts were asked to assess in significance (each on a 0–10 scale, not a relative rank order) can be seen in . The statements on the benefits and risks have been directly derived from the range of perspectives on DI expressed in the normative academic literature briefly reviewed above. Experts were also given the opportunity to state an ‘other’ option and indicate how significant they believed this was, but very few did so which provides a secondary validation that our list of the risks and benefits is comprehensive and representative of the academic debate.

Table 1. List of the Benefits and Risks of DI.

The analysis below primarily focuses on the bivariate relationships between experts’ appraisal of capacity and sovereignty DI, the significance the experts assigned to the different benefits and risks, as well as on experts’ views on whether DI should be allowed in all policy areas, and if not, which areas should be exempt. This analysis is used to establish where the expert community draws the theoretical boundaries of DI and how perceived differences in the acceptable boundaries vary between supporters of capacity and sovereignty DI respectively. The analysis then considers David Cameron's pre-referendum demands as a brief case study in order to explore whether experts’ theoretical understandings of the limits of DI are consistent with a recent high-profile and real-world example of strong demands for DI. It will focus on the relationship between support for capacity and sovereignty DI and specific support for the type of demands David Cameron put to the EU prior to the British EU membership referendum in 2016.

Empirical map of the perceived boundaries of differentiated integration

In this account of the findings, we shall move from the most general item of interest to the most specific one, thereby seeking to focus on what drives support for DI by experts, and what limits that support.

We begin with the amount of general support for a flexible Europe as expressed by different forms of DI. shows the first finding that experts are fairly positively minded towards institutional flexibility by means of DI in general. When asked about the acceptability of this type of flexibility on a scale from 0 to 10, only 15.8 per cent displayed a low degree of acceptability (0–3) whereas 53.7 per cent displayed a high degree of acceptability, with a mean of 6.27.

Table 2. Percentage levels of support for differentiated integration within the overall sample of experts.

Second, also shows that support for DI is qualified depending on the specific type of DI. As explained above, we distinguish between capacity DI, which is temporary and links to the idea of a multi-speed Europe, and sovereignty DI which tends to be permanent and links to the ideas of a Europe of concentric circles or variable geometry. Whereas the support for capacity DI was higher (mean of 7.63) than the general support for a flexible Europe, the support for sovereignty DI was lower (mean of 6.09). More concretely, 77.9 per cent of all experts expressed strong support for capacity DI, with only 10.5 per cent expressing low levels of support. By contrast, only 45.3 per cent expressed strong support for sovereignty DI whereas 21.1 per cent expressed low levels of support. These different levels of support for capacity and sovereignty DI respectively suggest that the difference between temporary and permanent DI is key for experts’ support of it.

Third, levels of support for the two types of DI are driven by different perceptions of their benefits and risks by supporters and opponents of DI ( and ). In the following, we will first look at the strong supporters of DI (scores of 7–10) before looking at its strong critics (scores of 0–3) and focus on the perceived benefits and risks of capacity and sovereignty DI which attracted strong scores (7–10).

Table 3. Perceived risks and benefits of DI among expert supporters of capacity and sovereignty DI.

As regards the perceived benefits of DI, for those who strongly support capacity DI two benefits stand out, namely that it allows the EU to move forward (82.2 per cent) and that it helps overcoming collective action problems (73 per cent), followed by the possibility to pioneer new measures (63.5 per cent). Strong supporters of sovereignty DI rated its perceived benefits considerably higher than strong supporters of capacity DI, thereby indicating a stronger general support for DI. Amongst this group of experts, the four perceived benefits that enjoyed the strongest support are that sovereignty DI allows the EU to move forward (86 per cent), that it recognizes the diversity of policy preferences (83.7 per cent), that it helps to overcome collective action problems, and that it recognizes that one size does not fit all (each 72.1 per cent).

As regards the risks, strong supporters of capacity DI saw its greatest risks in its ability to reinforce divisions (48.6 per cent) and increase the likelihood of member states free-riding on others (43.8 per cent). Strong supporters of sovereignty DI perceived the same two risks as strongest, just at a lower level (39.5 per cent and 30.2 per cent respectively). This confirms that those who strongly support sovereignty DI not only lend even greater support to the perceived benefits of DI overall but also are less concerned about the potential risks of DI than those who strongly approve of capacity DI.

Moving to those who strongly oppose either type of DI, it is not surprising that the numbers are somewhat inverted to those of the strong supporters of DI. Given the number of strong opponents of capacity DI is very small (10.5 per cent), we will not look into their assessments of benefits and risks as the bivariate relationships are too volatile. As regards the strong opponents of sovereignty DI and perceived benefits of DI, 45 per cent of them perceived the possibility of member states pioneering new measures as a strong benefit of DI, and 40 per cent positively credited DI for allowing the EU to move forward. As regards the risks, the concerns about divisions (75), challenges to the Rule of Law (70) and the DI weakening mutual trust (70) receive the strongest support.

To further specify when experts support DI and when they do not, and fourth, we will now look at which policy areas experts thought should be open to DI and which should be excluded from it. A very large majority of our experts thought that not all policy areas should be open to DI. 80.4 per cent considered that DI should not be permitted in certain policy areas, while only 19.6 per cent considered that DI should be permitted in all policy areas ().

Table 4. Perceived risks and benefits of DI among expert opponents of capacity and sovereignty DI.

We can now analyze whether these preferences for excluding certain policy areas are related to different levels of general support for DI and where supporters of different types of DI see the limits of DI in terms of specific policy areas. shows the strong supporters of capacity and sovereignty DI respectively do not actually differ so much in their assessment of whether DI should be permitted in all areas or not, when one might have expected strong supporters of sovereignty DI to show even greater acceptance of DI in all policy areas. It will not come as a surprise that those who credit capacity and sovereignty DI with low levels of legitimacy are 100% against permitting DI in all areas.

Table 5. Expert views of whether DI should be permitted in all policy areas by their support for capacity and sovereignty DI.

To identify which policy areas are considered as core policies in which all member states must participate, we asked our experts an open question about which policy areas they thought DI should not be permitted. For this survey item, we received 69 entries. This constitutes 72.6% of the respondents.

Which policy areas did experts think should be excluded from DI? In the discussion in section 1, we suggested that the Single Market would figure prominently as a policy area that experts would like to see exempted from DI, and that the Rule of Law would also attract considerable attention in this regard. Our analysis shows that these two areas do indeed figure prominently though perhaps differently than one might have thought. Whilst the Single Market does receive the most mentions, it is not as sacrosanct to experts as the prevailing EU doxa might lead one to believe. Out of the 69 entries for this item, only 40 explicitly mentioned the Single Market. When combining the 29 experts who did not mention the Single Market in the open question with the 18 experts who thought that DI should be possible in all policy areas, we find that only 48.8 per cent of our experts considers that the Single Market should be excluded from DI.

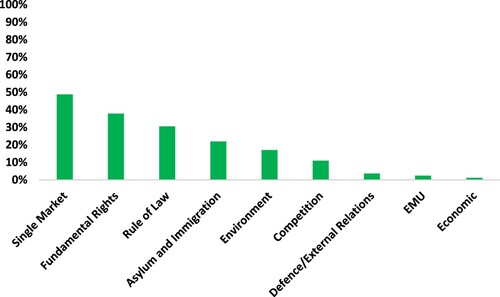

Other policy areas attract even less attention than the Single Market. demonstrates that whilst Fundamental Rights and the Rule of Law received a number of mentions, they are considerably behind the Single Market, with 31 mentions (37.8 per cent of the respondents) and 25 mentions (30.5 per cent of the respondents) respectively. In a context in which there has been systematic democratic backsliding in several member states over a number of years, these numbers appear rather low. Yet further behind are Asylum and Migration (18; 21.95 per cent) and Environment (14 mentions; 17.1 per cent), with a number of experts indicating high externalities in these policy areas as the reason why they put them down.

Figure 1. Experts views of the policy areas in which DI should not be permitted (as percentage of overall sample).

We will refrain from further bivariate analysis for all but one of these policy areas because of the fairly low number of responses per policy area. However, given its prominence in political and academic discussions, let us briefly have a closer look at the Single Market. If we combine the refusal to accept DI in the Single Market with our central analytical distinction between capacity and sovereignty DI, we see that for once, there are hardly any differences between these two sub-samples in their rejection of DI in the Single Market. demonstrates that of the strong supporters of capacity DI, 36.5 per cent considered that the Single Market should be exempt from DI, while 37.2 per cent of strong sovereignty DI supporters held the same view. This might appear as surprisingly low numbers. However, it is worth bearing in mind that they only reflect 28% and 16% per cent of the respondents of experts. Again, it is not surprising that strong opponents of either type of DI rejected the idea of exemptions in the Single Market by 100 per cent.

Table 6. Expert views of whether the Single Market should be exempt from DI by support for sovereignty and capacity DI.

The case of pre-Brexit demands of differentiated integration

As a last step in our analysis, we have a closer look at how our experts assessed the demands that David Cameron put to the EU at its Spring Council in 2016, prior to the British membership referendum, in an attempt to reach concessions which he hoped would help keep the UK in the EU. These demands related to competitiveness (reduce red tape), sovereignty (exempting the UK from the Treaty’s commitment to an ‘ever closer union of peoples’ and granting national parliaments the right to block EU legislation), economic governance (making sure the Eurozone cannot outvote the UK on issues affecting the Single Market, recognition that the euro is not the only currency of the EU, and assurance that the UK will not have to contribute to Eurozone bailouts), as well as migrants and welfare benefits (excluding newly arrived immigrants from in-work benefits as well as from Council housing for a number of years and a ban on sending child benefit money to countries of origin). In sum, these demands sought to mitigate certain effects of the Single Market. As such, they are the most far-reaching real-world attempt of DI yet and thus provide a useful case study to analyze how far scholars are willing to go in terms of accepting DI.

It was not much of a surprise that not all these demands were accepted by the other member states, and that the last demand in particular met with rejection. It was ‘so diametrically opposed to the principle of nondiscrimination on the ground of nationality as enshrined in the Treaties, that it was hard to see how the UK could be accommodated without damaging the fabric of the internal market and thereby the EU as a whole’ (Weiss and Blockmans Citation2016, 9). In other words, ‘the integrity of the internal market was a fundamental principle for all Member States’ (Schimmelfennig Citation2018, 1166) which proved non-negotiable.

highlights how our experts assessed the acceptability of these types of demands. We asked our experts to tell us how the EU should respond to a similar scenario in the future, where 0 means that the EU should accept any demands for less integration that would prevent a member state from leaving the Union, and 10 means that the EU should reject any demands for less integration from a member state that is threating to leave the Union. Again, we grouped the answers into three groups where 0–3 means ‘accept’ such demands, 4–6 are the middle scores where experts were fairly undecided and 7–10 are grouped to mean ‘reject’ such demands. As demonstrates, only 11 per cent of our sample thought that similar demands should be accepted in the future, while 51.6 per cent considered that they should be rejected, with the rest undecided, suggesting that for them, the specifics of the case would be decisive. It is interesting to see that the numbers of those who would like to see such demands accepted in the future do not increase dramatically even amongst those who consider capacity DI highly legitimate (12.7 per cent) and those who consider sovereignty DI highly legitimate (19 per cent), and also stay fairly stable when it comes to rejecting such demands (49.3 and 42.9 per cent respectively). They confirm that those who are strongly in favor of sovereignty DI have a slightly higher tolerance of demands for flexibility, including when it is more permanent or is in areas that were hitherto untouchable, such the Single Market.

Table 7. Levels of expert support for future pre-Brexit demands by DI type and support for DI exemptions.

Interestingly, only 41.2 per cent of those who considered that DI should be accepted in all policy areas thought that similar future demands should be accepted. This amounts to 6.65 per cent of the respondents, thereby indicating very low tolerance of the type of demands Cameron made even amongst the most fervent supporters of DI. Similarly, only 15.7 per cent of those who more generally thought that the Single Market should be open to DI would accept similar demands in the future in order to help prevent further disintegration (with 37.3 per cent of this sub-sample rejecting such demands), amounting to 7.6 per cent of the respondents. Looking at the risks that strong supporters of DI associated with it, one is led to believe that experts felt that giving into such demands would increase the risk of free-riding on other member states and also reinforce divisions. At the same time, the benefits that experts credited highest would not materialize through such demands, quite the contrary, whereas only the benefit that was by some distance rated the lowest would materialize, i.e. paying into rising levels of Euroscepticism. In sum, this data confirm the trends above of experts becoming more cautious when confronted with more concrete cases of DI.

Discussion

Our survey shows that the idea of a flexible Europe enjoys fairly high levels of support amongst experts in general, with capacity DI enjoying considerably higher levels of support than sovereignty DI. These results might not surprise and be found to reflect the mood of the time in which broadly integration-friendly scholars see DI as the second-best way of moving the European integration process forward. The concept of capacity DI in particular, which is linked to the idea of a multi-speed EU, generates high levels of support amongst scholars. These high levels of support, however, are not necessarily in tune with the perceived risks of DI. Almost half of the strong defenders of capacity DI consider its ability to reinforce divisions and increase the likelihood of member states free-riding on others as two very important risks. And, yet the perception of these risks does not lead these experts to have a more cautious endorsement of capacity DI overall. This suggests that they assess the benefits of DI as more important: namely, the potential for moving European integration forward and overcoming collective action problems. For the time being, it is unclear why these efficiency-related benefits trump the more normative concerns of free-riding and reinforcement of divisions. The situation is slightly different for strong supporters of sovereignty DI, who give less emphasis to potential risks overall than do strong defenders of capacity DI. Still, one could ask a similar question in future research.

The picture becomes even more complex when considering the next finding of our survey: namely, that the large majority of experts considers that not all policy areas should be open to DI. Experts are particularly critical of DI in the areas of the Single Market, Fundamental Rights, and the Rule of Law, with DI in Asylum and Migration also attracting opposition from more than a fifth of our respondents. These areas cover important elements of EU policies, and again one can ask how these findings chime with the overall strong support for a flexible Europe if a considerable part of our respondents considers that the above-mentioned policy areas should be exempt from DI altogether.

The emerging picture is further developed by our brief case study of the four demands that Prime Minister Cameron put to the EU in 2016, prior to the membership referendum. Whilst it is unsurprising that opponents of a flexible Europe would dismiss the idea of agreeing to such demands in the future, it is interesting that defenders of capacity DI would likewise reject such demands. More strikingly still, even amongst those who consider sovereignty DI highly legitimate and thought that DI should be possible in any policy area, a high percentage agreed that such demands should be rejected in the future. Given that this group of experts thought that the strongest benefits of DI were that it allows the EU to move forward, that it recognizes the diversity of policy preferences, that it helps to overcome collective action problems, and that it recognizes that one size does not fit all, this is an unexpected outcome as one could argue that Cameron’s demands were in line with some or even all of these points. Overall, what these findings show is that there is a considerable gap between experts’ support for the abstract idea of a flexible Europe and their assessments of concrete examples of it. We consider that this gap between the strong support of the abstract idea and fairly low support for concrete examples is linked to the current state of the literature on DI. Fairly little is known about the effects and tradeoffs of DI, and the normative literature on DI is only slowly emerging, with so far little impact on the empirical literature. As a result, it is possible that many experts’ abstract normative assessment of DI is more positive than the reality merits.

There is a second story to be told from the findings, which is one of considerable expert disagreement about DI, and we will use the remainder of this discussion to reflect on this fact. Disagreements between experts can arise from a variety of reasons which have been discussed elsewhere (Mumpower and Stewart Citation1996). They are often linked to measurement error relating to different information or data, missing or poor feedback, different context or the characteristics of the experts themselves. By contrast, we consider that the type of disagreement we see in the findings, particularly on the benefits and risks of DI, highlights genuine disagreement (as opposed to conceptual confusion) among experts.

We consider that the disagreement originates not in measurement error, but in two other sources. First, the fact that the support for benefits and risks is quite unevenly distributed amongst supporters of DI shows that value judgements differ between scholars. Some might say that the different weights given are because of information asymmetries. However, even if these existed, we would not expect them to impact the results as much. Instead, what we see is that scholars value different functions of DI to considerably different extents. Not everybody is concerned about XY as much as they are concerned about AB, etc., which is the expression of a value judgement that AB is more important than XY. Given the extent to which this varies not only between supporters and opponents of DI, but also within supporters of DI, it is impossible to reduce the disagreements to measurement error. Instead, they must originate in different value judgements not only of what the benefits and risks of DI are, but also of what is desirable for the EU.

This brings us to the second reason for the disagreements we see. Just as the benefits and risks of DI are assessed differently, it is well documented that there is persistent disagreement amongst scholars as to what the EU is and what it should be (see Moravcsik Citation1998 and Habermas Citation2003 for two opposing views). Some consider the EU a supranational polity or think it ought to develop into such a polity, others think of it as an intergovernmental organization. Which view scholars adopt in regard to these larger questions will inevitably influence their assessment of DI, along with different assessments of which subset of desiderata are more important than others and can best be achieved with or without DI.

According to the standard benchmarking approach to expert surveys, the multipolarity in our expert responses is a key limitation. We do not agree that multipolarity is automatically a problem for the validity of non-benchmarking expert surveys such as ours, provided that this reflects genuine disagreement in expert opinion rather than a lack of conceptual clarity. As Ian Budge has noted (2000), the assumption that collecting judgements from experts would result in them judging the same issue in exactly the same way is both theoretically and empirically incorrect. Experts might not be measuring the same object or understand metrics differently; some experts might have more relevant or better information than others. More importantly for our study, chances are that experts are influenced by their ontological assumptions about the EU and their related ideological preferences (Budge Citation2000; Levick and Olavarria-Gambi Citation2020; Maestas, Buttice, and Stone Citation2014; Martinez i Coma and Van Ham Citation2015; Steenbergen and Marks Citation2007).

Does the presence of the ‘value slope’ and resulting expert disagreement imply that the respective expertise is without added value? Certainly not. From a philosophical perspective, one can never be certain about the validity of a measure (Herrera and Kapur Citation2007; Munck and Verkuilen Citation2002). But also, and as importantly, convergence is not required for progress, and disagreement does not stand in the way of progress (Dellsen, Lawler, and Norton Citation2022) though it makes it more difficult to know which theories are accurate and which are not. Indeed, there are also potential benefits to academic disagreement. On the one hand, it can help generate new evidence and reevaluate existing evidence and theory as well as mitigate confirmation bias (De Cruz and de Smedt Citation2013, 176). In our case, the disagreement found is valid and substantively relevant in that it highlights a distribution of preferences that was hitherto hidden. On the other hand, expert disagreement might help render the experts more trustworthy in the public’s eyes when experts do not seek to hide disagreement over questions that involve value judgements (Dellsen Citation2018). The above then chimes with a view of experts-as-advisors rather than experts-as-authorities (Lackey Citation2018), where experts offer guidance rather than ultimate ‘truths’ to lay citizens.

Of course, we recognize some limitations of our study. First, it could only look at academic experts and so is limited in its scope. Whilst we have argued that it is nonetheless relevant, future expert surveys should try and enlarge the circle of experts to policy-makers in particular. Furthermore, whilst our study was able to uncover the distribution of expert preferences so far as DI is concerned, we were limited in explaining the levels of their support. Future (qualitative) research might wish to probe into the sources of the disagreement we found (see below). Finally, we appreciate that the circumstances surrounding Brexit make for quite an extreme real-world case study. It is reasonable to think that academics might be basing their assessment on what subsequently occurred (i.e. Brexit) rather than the relative merits of the exemptions that Cameron was asking for. It would be interesting for future research to see if there was such a discrepancy between abstract and real-world views if a less consequential example of exemption requests was used.

Conclusion

In this article, we have engaged with variation in the levels of support for DI in the EU by academic experts. Following the literature, we distinguished between capacity and sovereignty DI. The former tends to be temporary and linked to a lack of economic and/or administrative capacity and is generally associated with the idea of a multi-speed Europe. The latter tends to be permanent and linked to different integration preferences or value judgements of incumbent governments. We then reviewed the risks and benefits that scholars have associated with DI, the idea of the indivisibility of the Single Market – a doxa that EU institutions, policy-makers and numerous academics have long held – as well as the increased attention paid to the observance of the Rule of Law before turning to the empirical analysis.

Our findings showed that there is a fair amount of support in favor of a flexible Europe in general, with a considerably higher level of support for temporary capacity DI than for permanent sovereignty DI. We established that experts’ views on the benefits and risks of DI are diverse and contingent on their level of support for sovereignty and capacity DI. Both sub-samples perceive the same or similar benefits and risks, but attribute different levels of importance to them, with strong supporters of sovereignty DI more attached to national preferences and less concerned about free-riding in particular. We then explored the extent to which this is consistent with expert attitudes to DI in specific policy areas and the real-world example of the demands that the UK made before the UK membership referendum. Our data showed that DI in the Single Market finds the least support amongst experts while considerably fewer thought that the Rule of Law ought to be exempt from DI. Furthermore, the support for DI dramatically weakened when confronted with demands for more radical exemptions or opt-outs from specific policies, where experts are much more cautious in their assessment and tend to either reject them or to be less sure than when asked in the abstract. Not least given their role in policy-making, it is important that the assessment of more concrete cases and questions begin feeding into experts’ overall assessment of DI, so that experts do not convey a more optimistic picture about DI to the public and policy-makers than what their own assessment of concrete examples warrants.

As expected, our expert survey highlighted important disagreement within the academic community regarding preferences and priorities towards DI. While this makes it impossible for us to discuss ‘expert opinion’ towards DI as a homogenous set of preferences, it means that we have been able to make transparent the nature and extent of these divisions. This is useful for interested scholars and critical for policy-makers who can now recognize that expert views on DI are systematically divided according to a number of key dimensions and clusters of preferences. It is important that future research takes this into consideration and looks to uncover the sources of this diffusion of opinion within the expert community.

More specifically, the two gaps that we uncovered warrant more attention: on the one hand, the gap between the fairly high levels of support for a flexible Europe more generally and very concrete instances of it; on the other hand, the gap between high support for DI and the perceived risks, amongst the same group of respondents. What are the benefits that seem to balance those risks out, in many experts’ views, would be relevant to uncover. Looking into the tradeoffs of DI in our view requires a closer interaction between empirical and normative scholars of DI as well as more dialogue between those who are supportive of DI and those who are more critical.

Ethics approval

The research that led to this article received ethics approval from the University of Exeter, with the ethics committee reference number 201920-109.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the three anonymous reviewers of PRX for their insightful and constructive criticism. The authors are also grateful for the feedback received at the 2021 ECPR General Conference as well as in the online webinar series DI Garage, in November 2021. The authors furthermore would like to thank Richard Bellamy for constructive feedback and language editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For a discussion of capacity and sovereignty DI, see the next section (Taylor 1969).

2 See Charles Taylor’s criticism of the so-called neutrality of empirical political science and its ‘value slope’ (Taylor Citation1967).

3 Apart from these reasons, focusing on academic experts also closes a gap in the literature. Whilst there is increasing evidence how the public (de Vries and de Blok Citation2022; Leuffen, Schuessler, and Gómez Díaz Citation2022) and how governments (Telle, Badulescu, and Fernandes Citation2022) think of DI, we do not know so far what the more normative views of experts are as regards DI.

4 Frank Schimmelfennig and Thomas Winzen previously spoke of ‘instrumental’ and ‘constitutional’ DI (Citation2014) and use both pairs interchangeably.

6 A pilot study of the survey was run in early September 2020.

7 A total of 95 respondents from a target population of 139 (which represents the number of experts in the database).

8 The full set of survey questions can be found at: https://doi.org/10.24378/exe.4124. The full data set can be found at: https://doi.org/10.24378/exe.3904.

References

- Bakker, R., C. de Vries, E. Edwards, L. Hooghe, S. Jolly, G. Marks, J. Polk, J. Rovny, M. Steenbergen, and M. A. Vachudova. 2015. “Measuring Party Positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File, 1999–2010.” Party Politics 21 (1): 143–152. doi:10.1177/1354068812462931.

- Bellamy, R., and S. Kröger. 2017. “A Demoi-Cratic Justification of Differentiated Integration in a Heterogeneous EU.” Journal of European Integration 39 (5): 625–639. doi:10.1080/07036337.2017.1332058.

- Bellamy, R., and S. Kröger. 2021. “Countering Democratic Backsliding by EU Member States: Constitutional Pluralism and ‘Value’ Differentiated Integration.” Swiss Political Science Review 27 (3): 619–636.

- Bellamy, B., S. Kröger, and M. Lorimer. 2022. Flexible Europe. Differentiated Integration, Fairness and Democracy. Bristol: Bristol Policy Press.

- Benoit, K., and M. Laver. 2006. Party Policy in Modern Democracies. London: Routledge.

- Budge, I. 2000. “Expert Judgements of Party Policy Positions: Uses and Limitations in Political Research.” European Journal of Political Research 37 (1): 103–113.

- Castles, F. G., and P. Mair. 1984. “Left–Right Political Scales: Some ‘Expert’ Judgments.” European Journal of Political Research 12 (1): 73–88. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1984.tb00080.x.

- Council EU. 2019. Council Conclusion on EU Relations with the Swiss Confederation. Press Release 116/19, February 19, 2019.

- Curtin, D. 1993. “The Constitutional Structure of the Union; A Europe of Bits and Pieces.” Common Market Law Review 30: 17–69. doi:10.54648/COLA1993003.

- De Cruz, H., and J. de Smedt. 2013. “The Value of Epistemic Disagreement in Scientific Practice. The Case of Homo Floresiensis.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A 44: 169–177. doi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2013.02.002.

- Dehousse, R. 2003. “La méthode communautaire a-t-elle encore un avenir?” In Mélanges en hommage à Jean-Victor Louis, 1(5), 95–107. Bruxelles: Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles.

- Dellsen, F. 2018. “When Expert Disagreement Supports the Consensus.” Australasian Journal of Philosophy 96 (1): 142–156. doi:10.1080/00048402.2017.1298636.

- Dellsen, F., I. Lawler, and J. Norton. 2022. “Would Disagreement Undermine Process?” The Journal of Philosophy. Accessed 7 July 2022. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/20759/.

- De Vries, C. E., and L. de Blok. 2022. Differentiated Integration: Blessing and Curse? EUI, Policy Brief, 2022/28, April 2022.

- Duina, F. 2021. “Is Academic Research Useful to EU Officials? The Logic of Institutional Openness in the Commission.” Journal of European Public Policy 28 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1080/13501763.2020.1859600.

- Eriksen, E. O. 2018. “Political Differentiation and the Problem of Dominance: Segmentation and Hegemony.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (4): 989–1008. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12263.

- European Commission. 2017. “White Paper on the Future of Europe.” Brussels. Accessed 15 July 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/info/future-europe/white-paper-future-europe/white-paper-future-europe-five-scenarios_en.

- European Council. 2017. “Guidelines Following the United Kingdom’s Notification Under Article 50 TEU.” Brussels: 29 April.

- Gstöhl, S., and C. Frommelt. 2017. “Back to the Future? Lessons of Differentiated Integration from the EFTA Countries for the UK’s Future Relations with the EU.” Social Sciences 6 (121): 1–17.

- Habermas, J. 2003. “Making Sense of the EU. Toward a Cosmopolitan Europe.” Journal of Democracy 14 (4): 86–100. doi:10.1353/jod.2003.0077.

- Hammond, K. R. 1996. Human Judgment and Social Policy: Irreducible Uncertainty, Inevitable Error, Unavoidable Injustice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Herrera, Y. M., and D. Kapur. 2007. “Improving Data Quality: Actors, Incentives, and Capabilities.” Political Analysis 15 (4): 365–386. doi:10.1093/pan/mpm007.

- Hooghe, L., R. Bakker, A. Brigevich, C. De Vries, E. Edwards, G. Marks, J. Rovny, M. Steenbergen, and M. Vachudova. 2010. “Reliability and Validity of Measuring Party Positions: The Chapel Hill Expert Surveys of 2002 and 2006.” European Journal of Political Research 49 (5): 687–703. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01912.x.

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2009. “A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus.” British Journal of Political Science 39 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1017/S0007123408000409.

- Irvine, R. 2017. “Nationalists or Internationalists? China’s International Relations Experts Debate the Future.” Journal of Contemporary China 26 (106): 586–600. doi:10.1080/10670564.2017.1274822.

- Jasanoff, S. 1990. The Fifth Branch: Science Advisors as Policymakers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Kelemen, D. 2019. “Is Differentiation Possible in Rule of Law?” Comparative European Politics 17: 246–260. doi:10.1057/s41295-019-00162-9.

- Kröger, S., and T. Loughran. 2022. “The Risks and Benefits of Differentiated Integration as Perceived by Academic Experts.” Journal of Common Market Studies 60 (3): 702–720.

- Lackey, J. 2018. “Experts and Peer Disagreement.” In Knowledge, Belief, and God: New Insights in Religious Epistemology, edited by M. A. Benton, J. Hawthorne, and D. Rabinowitz, 228–245. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Laver, M. 1998. “Party Policy in Britain 1997: Results from an Expert Survey.” Political Studies 46 (2): 336–347. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00144.

- Laver, M., and W. B. Hunt. 1992. Policy and Party Competition. New York City, NY: Routledge.

- Leruth, B., S. Gänzle, and J. Trondal. 2019. “Differentiated Integration and Disintegration in the EU After Brexit: Risks Versus Opportunities.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 57 (6): 1383–1394.

- Leuffen, D., J. Schuessler, and J. Gómez Díaz. 2022. “Public Support for Differentiated Integration: Individual Liberal Values and Concerns About Member State Discrimination.” Journal of European Public Policy 29 (2): 218–237. doi:10.1080/13501763.2020.1829005.

- Levick, L., and M. Olavarria-Gambi. 2020. “Hindsight Bias in Expert Surveys: How Democratic Crises Influence Retrospective Evaluations.” Politics 40 (4): 494–509. doi:10.1177/0263395720914571.

- Lord, C. 2015. “Utopia or Dystopia? Towards a Normative Analysis of Differentiated Integration.” Journal of European Public Policy 22 (6): 783–798. doi:10.1080/13501763.2015.1020839.

- Lord, C. 2021. “Autonomy or Domination? Two Faces of Differentiated Integration.” Swiss Political Science Review 27: 546–562. doi:10.1111/spsr.12472.

- Maestas, C. D., M. K. Buttice, and W. J. Stone. 2014. “Extracting Wisdom from Experts and Small Crowds: Strategies for Improving Informant-Based Measures of Political Concepts.” Political Analysis 22 (3): 354–373. doi:10.1093/pan/mpt050.

- Martinez i Coma, F., and C. Van Ham. 2015. “Can Experts Judge Elections? Testing the Validity of Expert Judgments for Measuring Election Integrity.” European Journal of Political Research 54 (2): 305–325. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12084.

- Matthijs, M., C. Parsons, and C. Toenshoff. 2019. “Ever Tighter Union? Brexit, Grexit, and Frustrated Differentiation in the Single Market and Eurozone.” Comparative European Politics 17 (2): 209–230. doi:10.1057/s41295-019-00165-6.

- Moravcsik, A. 1998. The Choice for Europe: Social Purpose and State Power from Maastricht to Messina. London: Routledge.

- Mumpower, J. L., and T. R. Stewart. 1996. “Expert Judgement and Expert Disagreement.” Thinking & Reasoning 2 (2-3): 191–212. doi:10.1080/135467896394500.

- Munck, G. L., and J. Verkuilen. 2002. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: Evaluating Alternative Indices.” Comparative Political Studies 35 (1): 5–34.

- Pernice, I. 2010. “Costa v ENEL and Simmenthal: Primacy of European Law.” In The Past and Future of EU Law. The Classics of EU Law Revisited on the 50th Anniversary of the Rome Treaty, edited by L. Azoulai and M. Poiares Maduro, 47–59. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

- Schimmelfennig, F. 2018. “Brexit: Differentiated Disintegration in the European Union.” Journal of European Public Policy 25: 1154–1173.

- Schimmelfennig, F., D. Leuffen, and B. Rittberger. 2015. “The European Union as a System of Differentiated Integration: Interdependence, Politicization and Differentiation.” Journal of European Public Policy 22 (6): 764–782. doi:10.1080/13501763.2015.1020835.

- Schimmelfennig, F., and T. Winzen. 2014. “Instrumental and Constitutional Differentiation in the European Union.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52 (2): 354–370. doi:10.1111/jcms.12103.

- Schimmelfennig, F., and T. Winzen. 2020. Ever Looser Union? Differentiated European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Scott, J., and G. de Búrca. 2000. Constitutional Change in the EU: from Uniformity to Flexibility? Oxford: Hart.

- Shanteau, J. 1992. “The Psychology of Experts: An Alternative View.” In Expertise and Decision Support, edited by G. Wright and F. Bolger, 11–23. New York: Plenum Press.

- Steenbergen, M. R., and G. Marks. 2007. “Evaluating Expert Judgments.” European Journal of Political Research 46 (3): 347–366. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00694.x.

- Surowiecki, J. 2004. The Wisdom of Crowds. New York: Doubleday.

- Taylor, C. 1967. “Neutrality in Political Science.” In Philosophy, Politics, and Society, edited by P. Laslett and W. G. Runciman, 25–57. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Telle, S., C. Badulescu, and D. Fernandes. 2022. “Attitudes of National Decision-Makers Towards Differentiated Integration in the European Union.” Comparative European Politics 16 (1): 1–30.

- Weiss, S., and S. Blockmans. 2016. The EU Deal to Avoid Brexit: Take it or Leave. CEPS Special Report 131. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies.

- Winzen, T. 2016. “From Capacity to Sovereignty: Legislative Politics and Differentiated Integration in the European Union.” European Journal of Political Research 55 (1): 100–119. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12124.