ABSTRACT

This article aims to determine whether there are gender-based differences in using Twitter. For this purpose, 518,156 tweets from 280 Colombian Congress members were analysed. The study compares the number of tweets, audience, influence and efficacy of their messages on Twitter. Despite Colombia being below average in terms of political equality, research shows that a gender balance exists between Colombian male and female politicians on this social media channel. Members of the Colombian Congress use Twitter similarly, regardless of their gender: they are comparably influential in terms of volume, amplification, audience and efficacy of their messages. In fact, no significant gender differences exist regarding audience figures or amplification. However, the data show remarkable disparities regarding political party affiliation and ideological beliefs rather than gender.

Introduction

Although the number of women reaching leadership positions in politics, media, sports and business has increased over the last century, figures continue to show that women are still highly underrepresented at different levels, especially in politics. Although female representation in political parties in national Congresses and high-level political offices has increased over the last decades, this increment is still insufficient (Carty et al. Citation2021; UN Women Citation2021; Elder Citation2020; Bridgewater and Nagel Citation2020; Geertsema-Sligh Citation2018).

To explain women’s underrepresentation at the political level, several studies from sociology, psychology and communication fields have shown how gender can influence people’s political perceptions; male candidates are favoured while women are disabled towards political power (Fraile and Fortin-Rittberger Citation2020; Okimoto and Brescoll Citation2010; Ridgeway Citation2007; Rudman, Greenwald, and McGhee Citation2001; Ferré-Pavia, Abrego, and Gayà Morlà Citation2023).

This article focuses on the discipline of political communication and seeks to understand the differences in communication styles and visibility, under the premise that gender barriers exist (Sullivan Citation2021; Geertsema-Sligh Citation2018; Goodyear-Grant Citation2013; Lavery Citation2013; Brynstrom et al. Citation2004; Eagly and Karau Citation2002). This research analyses gender differences in using Twitter by Colombian members of Congress, and how this use can affect the amplification and effectiveness of their messages. To achieve the objective of this investigation, 518,156 tweets were analysed.

Colombia as a case of study

Colombia is a country with a presidential political system with many parties and movements reflecting political pluralism. Between 2018–2022, 13 political parties gained at least one seat in the Senate. However, the five parties with the most seats held an outright majority (71%); they belong to political parties marked by a right-wing or centre-right ideology. A similar case was noticed in the House of Representatives, where 16 political groups gained at least one seat, and the five political parties with the most seats gained 83% of the total seats available. All those political parties also had a right-wing or centre-right ideology. Although the official governing party did not accomplish an absolute majority in Congress, the president achieved governability, attributing to a coalition with the political parties with the largest representation.Footnote1, Footnote2

At this point, Colombian political history is marked by civil war and drug trafficking. In these circumstances, the left-wing political parties and movements have historically been associated with the guerrilla. Due to this political background, the country is undergoing an extreme polarization framed into two different visions of the State. Consequently, the presidential election of 2022 represented a radical change for the first time in Colombian history that had become accustomed to being ruled by right-wing politicians.Footnote3

From 2018 to 2022, only 32 of 171 seats in the Colombian House of Representatives were held by women. This scenario was similar in the Senate, where only 23 seats of 108 were held by female senators. This is equivalent to 19.9% representation of women in the national legislature (UN Women Citation2021). Based on these figures, the country ranked below the worldwide average, being only surpassed in the region by Brazil and Paraguay, countries that have an even lower female representation in Congress than Colombia.Footnote4

Regarding the number of congresswomen, 80% of women come from the strong representation of right-wing or centre-right political parties. This situation suggests that the female voice of Colombian congresswomen is highly conservative.

Finally, the authors chose Colombia as a case study since it is one of the countries in Latin America with the lowest levels of female political representation in Congress despite the existing gender quota law. Moreover, for the case of Twitter, even though the microblogging network does not disclose official figures, the industry estimates that about six million Colombians use this platform, placing Colombia above France and Germany (González and Richard Citation2020) in the number of users.

Literature review

Gender, leadership and empowerment in politics

Although different sectors have been working, intentionally or superficially, to achieve real parity between men and women in recent years, the figures presented at the beginning of this article reveal that there is still a long way to go in this regard. There are sobering indicators that gender inequalities persist, such as the number of women in positions of power in the political arena (Brown, Clark, and Mahoney Citation2022; UN Women Citation2021).

The literature shows that analysing stereotypes is relevant when addressing the concept of power. Some studies expose that pursuing power can be inconsistent with traditional female gender stereotypes, yet the opposite could be stated regarding male stereotypes. Although there are many definitions of stereotype (Hamilton and Trolier Citation1986; Rosenthal and Jacobson Citation1968; Lazarsfeld and Merton Citation1948), social psychologists agree that stereotypes are cognitive structures that contain the knowledge, beliefs and expectations about a person or group may cast some bias on perception, attributes and behaviours (Rudman and Glick Citation2008).

In this vein, existing cultural stereotypes generally describe women as communitarian, i.e. sensitive, warm, caring and nurturing. In contrast, men are seen as agents: dominant, assertive and competitive people (Okimoto and Brescoll Citation2010; Abele and Wojciszke Citation2007). These gender stereotypes have resulted in biases around which cultural attributes have been framed, often making women appear less suited to assume roles of power and leadership (García Beaudoux, D’Adamo, and Gavensky Citation2017; Fridkin and Kenney Citation2009; Fulton et al. Citation2006).

Rudman and Glick (Citation2008) found that women are perceived as less competent, ambitious and competitive than men and therefore are frequently not considered for leadership positions unless they present themselves as atypical women. Additionally, they warn that, on many occasions, women may be forced to decide between being liked and loved or being respected. In another study, Eagly and Karau (Citation2002) stated that there is an incongruence between the female gender role and leadership roles, leading to two forms of prejudice: (a) perceiving women less favourably compared to men seeking leadership roles and (b) assessing their behaviour in leadership positions less favourably. Consequently, it is more difficult for women to become leaders and succeed in leadership positions. Evidence reveals that although men and women perform in the same scenarios, the rules and conditions antagonize women.

In politics, these generalized expectations are usually supported by actions and decisions made by women and men when they assume positions of power; many of the actions they take while in office help reinforce existing cultural stereotypes and hierarchical relations (Duval and Bouchard Citation2021; Denemark, Ward, and Bean Citation2012; Ridgeway Citation2007; Rudman and Fairchild Citation2004; Jost, Banaji, and Nosek Citation2004; Koch Citation2000). Clearly, power continues to be a hostile territory for women because of the existing gender stereotypes and their relationship to leadership, alongside the influence of the media in perpetuating those biases and creating new cultural barriers that make it more difficult for women to become visible in positions of power and influence (García Beaudoux, D’Adamo, and Gavensky Citation2017; Jalalzai Citation2006).

In the digital era, such discrimination is also present in social networks (Krook Citation2022; Fosch-Villaronga et al. Citation2021). Regarding social politics, Beltran et al. (Citation2021) apply the Lasso logistic regression models to identify the linguistic features that most differentiate the language used by or addressed to male and female Spanish politicians. They found evidence of gender-specific insults and a disproportionate number of mentions of physical appearance and infantilising words addressed to female politicians. Politicians conform to gender stereotypes online, and citizens treat politicians differently depending on their gender.

This is also relevant during election periods. Voters’ attitudes towards gender also shape their electoral preferences. Long, Dawe, and Suhay (Citation2021) argue that the effects of gender attitudes are present in the voters’ preferences. However, they are not unidirectional: they interact in complex ways with the perceptions of candidates, depending not only on the candidates’ sex but also on their gender-relevant characteristics and values.

The use of social media to gain visibility?

Traditionally, media was considered one of the main barriers for women, and a less sexist media environment would allow more women to run for office (Haraldsson and Wängnerud Citation2019; Vann Citation2014).

Election campaigns show a clear example of female candidates failing to achieve media visibility because there are marked differences in the coverage and volume of news and stories published (Paatelainen, Kannasto, and Isotalus Citation2022; Goodyear-Grant Citation2013; Bode and Hennings Citation2012). However, these limitations are not only noticeable in electoral periods. Thomas et al. (Citation2020) reviewed the type of media coverage of female heads of government around the world; their findings display that, on average, fewer news stories are written about them, and coverage regarding women stereotypically features feminine gender identifiers, such as clothing or private lives.

This concern about the quality and type of coverage received by female politicians spread to different countries and regions worldwide. Although little was written about this phenomenon in Latin America, data exist evidencing that gender stereotypes are still present in journalistic imaginings when covering some news related to women’s candidacies or leadership (García-Beaudoux et al. Citation2020; Llanos Citation2013).

With this rigid background in mind, some authors have proposed that digital platforms became a lifeline for women seeking to avoid this often sexist and limited coverage, as they do not operate under the same logic as traditional media. They argue that social media has the potential to generate parity and equality in politics (Cardo Citation2021; Wagner, Gainous, and Holman Citation2017).

For example, Alotaibi and Mulderrig (Citation2021) concluded in their research that during the 2011 Arab Spring, women used social media as public platforms to highlight and contest the unequal social status of women in Saudi society. Because of its effectiveness, Saudi women have launched numerous social media campaigns since then.

At an academic level, special attention was given to Twitter as an opinion-generating platform, in presidential and parliamentary systems, in consideration of its growth rate, the ease of using its data, its logic and the topics that are discussed to generate more interactions with the audience (Gainous and Wagner Citation2014). In this regard, Twitter analysis was at the forefront because of the platform’s accessible data and the value placed on it by politicians and journalists, who frequently use Twitter trends as real-time indicators of public opinion, instead merely of its number of users (Hu and Kearney Citation2021; Jungherr, Schoen, and Jürgens Citation2016; Evans, Cordova, and Sipole Citation2014; Enli and Skogerbø Citation2013).

In the specific case of visibility, several studies have demonstrated Twitter’s ability to allow political candidates to broadcast their messages directly to the public and carry out transmedia communication actions, which aim to reach the largest number of users possible and transform supporters into active participants and content creators (Darwin and Haryanto Citation2021; Arifiyanti, Wahyuni, and Kurniawan Citation2020; Calzado Citation2020; Larsson Citation2020; Graham and Schwanholz Citation2020; Hemsley Citation2019; Correa and Camargo Citation2017; Jungherr Citation2014; Boynton Citation2014; O’Connor et al. Citation2010; Stromer-Galley Citation2002).

Some other studies show that although social networks can lower the barriers to access media coverage traditionally reproduced by the mass media, these problems are still present (Guerrero-Solé and Perales-García Citation2021; Hrbková and Macková Citation2021; Hosseini Citation2019). The significant differences towards gender regarding audience figures and amplification are still noticeable, as both male and female politicians retweet considerably more content posted by men than by women. However, on social networks, the communication style of female candidates does not differ significantly from that of male candidates.

Finally, other studies have shown the negative impact of such platforms. Social networks can increase online hostility (Esposito and Breeze Citation2022), hate speech and misogyny against women politicians (Fuchs and Schäfer Citation2021). As a result, it promotes a more aggressive discourse over women politicians (De Paula Trindade Citation2020; Hosseini Citation2019; Wagner, Gainous, and Holman Citation2017; Evans and Clark Citation2016; Erjavec and Kovačič Citation2012).

Therefore, considering the use of social networks by female politicians, this paper aims to contribute to the analysis of the differences in the use of Twitter by male and female politicians. For this purpose, the number of tweets, audience, influence and efficacy of the messages on Twitter were analysed. Moreover, the study compares the lexical recurrences characterizing Colombian congresswomen’s and men’s discourse on the social network.

Method

This paper pursues the following specific objectives to achieve the general objective: the analysis of gender differences in the use of Twitter:

To identify gender differences among Colombian members of Congress based on the number of tweets, audience, influence and efficacy of their messages on Twitter.

To compare the lexical recurrences characterizing Colombian congresswomen’s and men’s discourse on Twitter.

As a hypothesis, it is stated that:

(H1) Twitter allows equal visibility for men and female legislators.

(H2) A gender bias exists in the vocabulary use by congressmen and congresswomen.

System indicators

To this purpose, three indicators based on Guerrero-Solé and Perales-García (Citation2021) were developed:

Influence index: Number of tweets per author in a period of time (post, share, reply), divided by the total number of tweets in the sample and multiplied by the average number of followers gained by each author in the same period of time.

Efficacy index: Number of times an author was retweeted in a period of time (type of entry: post) divided by the average number of followers gained by each author in the same period and multiplied by the number of tweets issued.

Correlation index: This index determines the patterns of correlation and divergence in the words used by politicians analysed in this study. It seeks to demonstrate the existence or inexistence of gender stereotypes in the discourse.Footnote5 For this purpose, the Pearson’s statistical test was performed.

Lastly, it is important to note that this study’s limitations relate to the date of data collection, since users can delete past tweets, retweets, shares or comments. The data presented in the following section results from the distribution of members of Congress depending on gender and political party. Also, this study’s findings are limited to only the ten politicians with the greatest influence and effectiveness on Twitter.

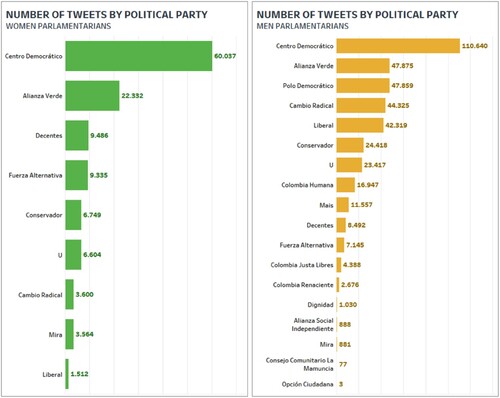

In this regard, it is noteworthy that the most active congresswomen on social networks belong to the Democratic Centre party (DC, right-wing party) and the Green Party (GP, centre-left party). Between these two parties, they post a little more than 66% of the messages published on Twitter by women. The DC party tweets almost three times more messages than the GP. In the case of men, the situation changes as there is a greater dispersion: 74% of the conversation is generated by congressmen belonging to five different political parties. In this list, the DC party stands out again, with more than twice as many messages as the second party in the list. For more details, see annex 1.

Sample

For this research, posted tweets, shares, replies and retweets were collected between June 1st, 2020, and August 1st, 2021, coinciding with a full year of the legislature. During this period, there were no electoral campaigns in the country, so the electoral cycle could not contaminate the study.

The sample comprised 518,156 analysed tweets collected using the web scraping technique through the Brandwatch platform. 76% of the total tweet samples correspond to congressmen, while the remaining 24% correspond to congresswomen. The R programming language was used for data processing, tidyverse and tidytext were the main digital libraries and Tableau was implemented for the visual analysis of results.

For data analysis, unnecessary characters, such as punctuation marks, numbers and stop-words, were removed from the list provided by @genediazjr. Repeated words without major relevance to the research were eliminated to refine the database. Data processing was focused on determining the general characteristics of the type of conversation that predominates in this social network and on finding the implications of the most important topics for each account, trying to identify frequencies, patterns and correlations.

Results

Gender, political parties and volume of conversation

When reviewing the sample, gender and political party were taken into account. shows that male and female members of Congress from right-wing parties posted the largest number of tweets during the period analysed. The members of Congress affiliated with the Democratic Centre party (the predominant right-wing party in the country) maintained the highest volume of conversations on Twitter during the same period.

Particularly in the case of female members of Congress, data indicate that the level of political pluralism is low. Thus, the number of parties that have elected congresswomen in Colombia is minimal and corresponds mostly to traditional and conservative political parties. Moreover, data reveal that most of the tweets posted by female politicians are also linked to right-wing parties. In this case, the number of messages from female legislators affiliated with the Democratic Centre party stands out. They posted almost twice as many messages as the congresswomen of the second-largest party, the Green Party. Women at the top of the table achieve their position, attributing to their ideology and the predominance of their parties; other women have a peripheral role.

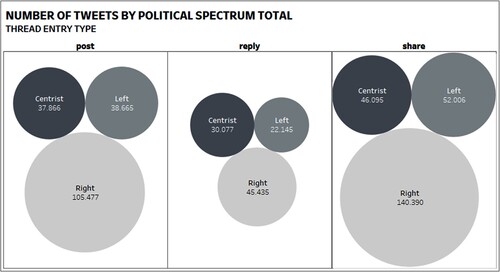

At this point, analysing the type of messages posted, their capacity to influence and effectiveness is more remarkable than the volume of messages in the conversation, especially for a social network such as Twitter. By clustering political parties in the spectrum of right, centre and left, reveals that men and women have a strong tendency to share content produced on other accounts rather than post original content or respond to comments by other authors.

Evangelizing through the message: influence and efficacy on Twitter

Regarding the influence and efficacy indices, and rank the 10 most influential and effective members of Congress on Twitter. The resulting evidence shows that the number of tweets each account posts is disproportional to the achieved amplification. Moreover, no correlation exists between the most influential and most effective authors. In the first case, they achieve a greater reach or visualization of their messages. However, in the second case, authors convert that reach into greater interactions and have a better follower conversion rate.

Table 1. Author distribution according to influence index.

Table 2. Author distribution according to efficacy index.

When data are cross-referenced against the influence index, the top 10 most influential members of Congress are evidently equally distributed among men and women. Hence, the number of accounts reached by chamber members on Twitter is similar to other users. The only account that stands out in this list for having an influence index well above the average is a senator and former presidential candidate, Gustavo Petro (@petrogustavo, of the Colombia Humana party). Something similar happens when comparing the list of the most effective authors: there is also a balanced distribution of accounts. However, in this case, most women, except for a right-wing party congresswoman, are at the bottom of the table.

Tell me what you talk about, and I’ll tell you who you look like

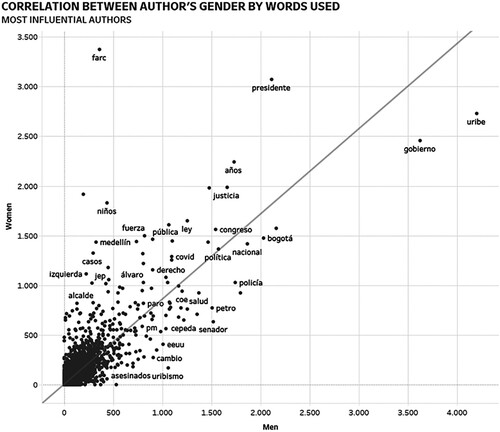

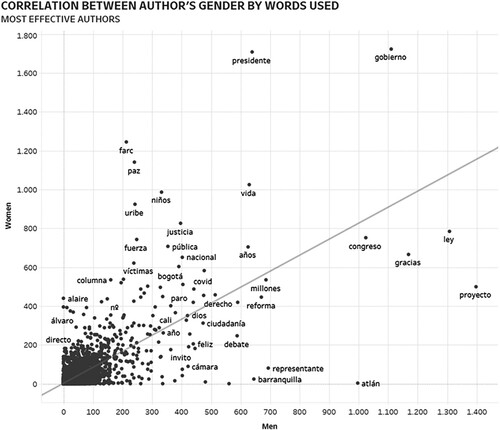

Lastly, this research identified the most frequently used words in Twitter accounts to understand whether there is any correlation with the content of their tweets. The results of and show no significant difference between the most used words mentioned by the most influential and most effective legislators.

Interestingly, words linked to attributes culturally defined as feminine or having a gender bias in political language do not exist. Conversely, there is a strong confrontational narrative related to political ideology.

Discussion of results

The methodology used to analyse the collected data sets the groundwork for determining whether there are gender-based differences in using Twitter. To identify these differences, the research compares the number of tweets, audience, influence and efficacy of the messages.

As a result, this article concludes that male and female members of the Colombian Congress use Twitter identically: they are as influential in volume, amplification, audience and efficacy. In fact, the list of the 10 most influential and effective politicians on Twitter is evenly distributed between women and men. This enabled us to corroborate the hypothesis (H1) by demonstrating that Twitter allows equal visibility for male and female legislators, at least in the case of the Colombian congressmen and congresswomen among the top 10 most influential and effective in this social network.

Nevertheless, while the central axis of this research sought to analyse the differences in Twitter usage by women and men politicians in Colombia, these differences are related to the political background of the actors in reality. In this particular case is the political ideology a key element required for understanding the capacity of influence and effectiveness of Colombian politicians on Twitter.

Meanwhile, (H2), which sought to determine whether or not there were lexical differences based on gender stereotypes, was discarded. Contrary to this idea, the words most used by congressmen and congresswomen are related to their political position and the polarization that the country is experiencing. The data show remarkable differences in speech based on the political party affiliation and the ideological tendency rather than gender. Male and female members of Congress tend to be closer in their rhetoric, creating great ideological proximity between them.

The findings presented here represent a challenge for future research. The data show that, at least in the Colombian case, providing an answer related only to gender issues is impossible when dealing with political matters. More comprehensive approaches that include context-related variables, political ideology and polarization are needed (Skoog and Karlsson Citation2022; Rojas Citation2008). Analysing investigations exploring issues related to political polarization on the Internet and its effects on the democratic debate is important.

Conclusions

Previous research has confirmed that when the emphasis is on leadership, communication and visibility of women politicians, traditional media become one of the main obstacles to access to power. Women who want to participate in politics must navigate in a context where media coverage is highly biased, both in the quantity and quality of the spaces available. This trend negatively affects women’s access to politics and contributes to the entrenchment of dominant political rhetoric and culture.

This research shows that the fact that Colombia is below average in political equality has consequences for the quantity of conversations that women politicians can generate on social networks, such as Twitter. However, the data presented here reflect ‘gender equality’ when measuring the most influential and effective Colombian politicians on Twitter despite fewer women in Congress. For this particular case, there are no significant gender differences in audience or message amplification.

The study demonstrates that barriers for women still exist. In the Colombian case, these challenges go beyond gender issues; they are linked to polarization and political ideology. These factors must be considered when analysing social networks’ use and media effects.

Meanwhile, it is important to mention the limitations of this research. First, this study analysed only the ten politicians with the greatest influence and effectiveness on Twitter, which limits the findings presented here. Second, the results of the case studies, including this one, are determined by the contextual characteristics of the place where the analyses are carried out and by the moment in which the data were collected. Elements such as the political context, the party in power, the electoral calendar and previous recognition of politicians, among other factors not analysed in this research, play an important role.

In the future, complementing this type of research with more cases and more qualitative data is important to better understand these results and their real implications, if any, for more and better women's political participation. Moreover, expanding this research from key concepts such as political ideology would be interesting. The data initially collected here suggest that differences in the type of conversations taking place on Twitter would be linked to a greater extent to the degree of polarization of the political scene.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This paper is a part of the PhD of the first author, with second’s permission. Angie K. González is advancing their doctoral thesis in the Department of Media, Communication and Culture of the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain.

2 The results of these elections can be consulted at https://www.registraduria.gov.co/-Historico-de-Resultados-3635-3635-3635-3635-3635

3 During the 2022 presidential elections, President Gustavo Petro was elected. Petro is a former member of one of Colombia’s most notorious guerrillas, the M19.

4 In 2023 the ranking will show different results, due to the outcome of the parliamentary elections held in Colombia in March 2022.

5 Authors, such as Eagly and Karau (Citation2002), have shown that there is a gender bias in political language that responds to the stereotype of women associated with family matters and private spaces.

References

- Abele, A. E., and B. Wojciszke. 2007. “Agency and Communion from the Perspective of Self Versus Others.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 93 (5): 751–763. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.751.

- Alotaibi, N., and J. Mulderrig. 2021. “Debating Saudi Womanhood: A Corpus-Aided Critical Discourse Analysis of the Representation of Saudi Women in the Twitter Campaign Against the ‘Male Guardianship’ System.” In Exploring Discourse and Ideology Through Corpora. Linguistic Insights: Studies in Language and Communication, 276, edited by M. Fuster-Marquez, J. Santaemilia, C. Gregori-Signes, and P. Rodriquez-Aburneiras, 233–262. Bern: Peter Lang. doi:10.3726/b17868

- Arifiyanti, A. A., E. D. Wahyuni, and A. Kurniawan. 2020. “Emotion Mining of Indonesia Presidential Political Campaign 2019 Using Twitter Data.” Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1569 (2): 022035. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1569/2/022035.

- Beltran, J., A. Gallego, A. Huidobro, E. Romero, and L. Padró. 2021. “Male and Female Politicians on Twitter: A Machine Learning Approach.” European Journal of Political Research 60 (1): 239–251. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12392.

- Bode, L., and V. M. Hennings. 2012. “Mixed Signals? Gender and the Media’s Coverage of the 2008 Vice Presidential Candidates.” Politics and Policy 40 (2): 221–257. doi:10.1111/j.1747-1346.2012.00350.x.

- Boynton, G. R. 2014. “The Political Domain Goes to Twitter: Hashtags, Retweets and URLs.” Open Journal of Political Science 04 (1): 8–15. doi:10.4236/ojps.2014.41002.

- Bridgewater, J., and R. U. Nagel. 2020. “Is There Cross-National Evidence That Voters Prefer Men as Party Leaders?” Electoral Studies 67), doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102209.

- Brown, N. E., C. J. Clark, and A. Mahoney. 2022. “The Black Women of the US Congress: Learning from Descriptive Data.” Journal of Women, Politics and Policy 43 (3): 328–346. doi:10.1080/1554477X.2022.2074757.

- Brynstrom, D. G., M. C. Banwart, L. L. Kayd, and T. A. Robertson. 2004. Gender and Candidate Communication: Videostyle, Webstyle, Newsstyle. London, Routledge.

- Calzado, M. 2020. “Election Campaign Audiences and Urban Security: Citizens and Elections Promises During a Mediatized Political Campaign (Argentina 2015).” Communication and Society 33 (2): 155–169. doi:10.15581/003.33.2.155-169.

- Cardo, V. 2021. “Gender Politics Online? Political Women and Social Media at Election Time in the United Kingdom, the United States and New Zealand.” European Journal of Communication 36 (1): 38–52. doi:10.1177/0267323120968962.

- Carty, E. B., M. Alcántara, M. García Montero, and C. Rivas Pérez, eds. 2021. “Politics and Political Elites in Latin America: Challenges and Trends.” Revista Latinoamericana de Opinión Pública 10 (1): 181–184.

- Correa, J. C., and J. E. Camargo. 2017. “Ideological Consumerism in Colombian Elections, 2015: Links Between Political Ideology, Twitter Activity, and Electoral Results.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking 20 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1089/cyber.2016.0402.

- Darwin, R. L., and N. Haryanto. 2021. “Women Candidates and Islamic Personalization in Social Media Campaigns for Local Parliament Elections in Indonesia.” South East Asia Research 29 (1): 72–91. doi:10.1080/0967828X.2021.1878928.

- Denemark, D., I. Ward, and C. Bean. 2012. “Gender and Leader Effects in the 2010 Australian Election.” Australian Journal of Political Science 47 (4): 563–578. doi:10.1080/10361146.2012.731485.

- De Paula Trindade, L. 2020. “My Hair, My Crown”. Examining Black Brazilian Women’s Anti-Racist Discursive Strategies on Social Media.” Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies / Revue Canadienne des Études Latino-Américaines et Caraïbes 45 (3): 277–296. doi:10.1080/08263663.2020.1769448.

- Duval, D., and J. Bouchard. 2021. “Gender, the Media and Parity: The Case of the 2018 Québec Election.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 54 (3): 637–654. doi:10.1017/S000842392100038X.

- Eagly, A. H., and S. J. Karau. 2002. “Role Congruity Theory of Prejudice Toward Female Leaders.” Psychological Review 109 (3): 573–598. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573.

- Elder, L. 2020. “The Growing Partisan Gap Among Women in Congress.” Society 57 (5): 520–526. doi:10.1007/s12115-020-00524-0.

- Enli, G. S., and E. Skogerbø. 2013. “Personalized Campaigns in Party-Centred Politics: Twitter and Facebook as Arenas for Political Communication.” Information, Communication and Society 16 (5): 757–774. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2013.782330.

- Erjavec, K. E., and M. P. Kovačič. 2012. “You Don’t Understand, This Is a New War! Analysis of Hate Speech in News Web Sites’ Comments.” Mass Communication and Society 15 (6): 899–920. doi:10.1080/15205436.2011.619679.

- Esposito, E., and R. Breeze. 2022. “Gender and Politics in a Digitalized World: Investigating Online Hostility Against UK Female MPs.” Discourse and Society 33 (3): 303–323.

- Evans, H. K., and J. H. Clark. 2016. “You Tweet Like a Girl!”: How Female Candidates Campaign on Twitter.” American Politics Research 44 (2): 326–352. doi:10.1177/1532673X15597747.

- Evans, H. K., V. Cordova, and S. S. Sipole. 2014. “Twitter Style: An Analysis of How House Candidates Used Twitter in Their 2012 Campaigns.” PS: Political Science and Politics 47 (2): 454–462. doi:10.1017/S1049096514000389.

- Ferré-Pavia, C., K. Abrego, and C. Gayà Morlà. 2023. Communicative Empowerment for Female Politicians: Moving Towards a Safe Space That Makes Them Visible in Social Media.” Working paper.

- Fosch-Villaronga, E., A. Poulsen, R. A. Søraa, and B. H. M. Custers. 2021. “A Little Bird Told Me Your Gender: Gender Inferences in Social Media.” Information Processing and Management 58 (3): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102541.

- Fraile, M., and J. Fortin-Rittberger. 2020. “Unpacking Gender, Age, and Education Knowledge Inequalities: A Systematic Comparison.” Social Science Quarterly 101 (4): 1653–1669. doi:10.1111/ssqu.12822.

- Fridkin, K. L., and P. J. Kenney. 2009. “The Role of Gender Stereotypes in U.S. Senate Campaigns.” Politics and Gender 5 (3): 301–324. doi:10.1017/S1743923X09990158.

- Fuchs, T., and F. Schäfer. 2021. “Normalizing Misogyny: Hate Speech and Verbal Abuse of Female Politicians on Japanese Twitter.” Japan Forum 33 (4): 553–579. doi:10.1080/09555803.2019.1687564.

- Fulton, S. A., C. D. Maestas, L. S. Maisel, and W. J. Stone. 2006. “The Sense of a Woman: Gender, Ambition, and the Decision to Run for Congress.” Political Research Quarterly 59 (2): 235–248. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4148091.

- Gainous, J., and K. M. Wagner. 2014. Tweeting to Power: The Social Media Revolution in American Politics. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- García Beaudoux, V., O. D’Adamo, and M. Gavensky. 2017. “Una Tipología de los Sesgos y Estereotipos de Género en la Cobertura Periodística de las Mujeres Candidatas.” Revista Mexicana de Opinión Pública 24: 113–129. doi:10.22201/fcpys.24484911e.2018.24.61614.

- García-Beaudoux, V., O. D’Adamo, S. Berrocal, and M. Gavensky. 2020. “Stereotypes and Biases in the Treatment of Female and Male Candidates on Television Shows in the 2017 Legislative Elections in Argentina.” RLCS. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 77: 275–293. doi:10.4185/RLCS-2020-1458.

- Geertsema-Sligh, M. 2018. “Gender Issues in News Coverage.” In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, edited by T. P. Hanusch, F. Vos, D. Dimitrakopoulou, M. Geertsema-Sligh, and A. Sehl, 1–8. Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/9781118841570.iejs0162.

- González, A., and E. Richard. 2020. “Hashtags y Discusión Política: Lo Que Twittearon los Candidatos a la Alcaldía de Bogotá.” In Elecciones subnacionales 2019: Una redefinición de los partidos y de sus campañas electorales, edited by F. Barrero and E. Richard, 643–668. Berlin, Konrad Adenauer Foundation.

- Goodyear-Grant, E. 2013. Media Coverage and Electoral Politics in Canada. Vancouver, UBC Press.

- Graham, T., and J. Schwanholz. 2020. “Politicians and Political Parties Use of Social Media in-Between Elections.” Journal of Applied Journalism and Media Studies 9 (2): 91–103. doi:10.1386/ajms_00017_1.

- Guerrero-Solé, F., and C. Perales-García. 2021. “Bridging the Gap: How Gender Influences Spanish Politicians’ Activity on Twitter.” Journalism and Media 2 (3): 469–483. doi:10.3390/journalmedia2030028.

- Hamilton, D. L., and T. K. Trolier. 1986. “Stereotypes and Stereotyping: An Overview of the Cognitive Approach.” In Prejudice, Discrimination, and Racism, edited by J. F. Dovidio and S. L. Gaertner, 127–163. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Academic Press.

- Haraldsson, A., and L. Wängnerud. 2019. “The Effect of Media Sexism on Women’s Political Ambition: Evidence from a Worldwide Study.” Feminist Media Studies 19 (4): 525–541. doi:10.1080/14680777.2018.1468797.

- Hemsley, J. 2019. “Followers Retweet! The Influence of Middle-Level Gatekeepers on the Spread of Political Information on Twitter.” Policy and Internet 11 (3): 280–304. doi:10.1002/poi3.202.

- Hosseini, B. 2019. “Women’s Survival Through Social Media: A Narrative Analysis.” Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 25 (2): 180–197. doi:10.1080/12259276.2019.1610612.

- Hrbková, L., and A. Macková. 2021. “Campaign Like a Girl? Gender and Communication on Social Networking Sites in the Czech Parliamentary Election.” Information, Communication and Society 24 (11): 1622–1639. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2020.1716040.

- Hu, L., and M. W. Kearney. 2021. “Gendered Tweets: Computational Text Analysis of Gender Differences in Political Discussion on Twitter.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 40 (4): 482–503. doi:10.1177/0261927X209697.

- Jalalzai, F. 2006. “Women Candidates and the Media: 1992–2000 Elections.” Politics and Policy 34 (3): 606–633. doi:10.1111/j.1747-1346.2006.00030.x.

- Jost, J. T., M. R. Banaji, and B. A. Nosek. 2004. “A Decade of System Justification Theory: Accumulated Evidence of Conscious and Unconscious Bolstering of the Status Quo.” Political Psychology 25 (6): 881–919. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00402.x.

- Jungherr, A. 2014. “Twitter in Politics: A Comprehensive Literature Review.” SSRN Electronic Journal, doi:10.2139/ssrn.2402443.

- Jungherr, A., H. Schoen, and P. Jürgens. 2016. “The Mediation of Politics Through Twitter: An Analysis of Messages Posted During the Campaign for the German Federal Election 2013.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 21 (1): 50–68. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12143.

- Koch, J. W. 2000. “Do Citizens Apply Gender Stereotypes to Infer Candidates’ Ideological Orientations?” The Journal of Politics 62 (2): 414–429. doi:10.1111/0022-3816.00019.

- Krook, M. L. 2022. “Semiotic Violence Against Women: Theorizing Harms Against Female Politicians.” Signs 47 (2): 371–397. doi:10.1086/716642.

- Larsson, A. O. 2020. “Right-Wingers on the Rise Online: Insights from the 2018 Swedish Elections.” New Media and Society 22 (12): 2108–2127. doi:10.1177/1461444819887700.

- Lavery, L. 2013. “Gender Bias in the Media? An Examination of Local Television News Coverage of Male and Female House Candidates.” Politics and Policy 41 (6): 877–910. doi:10.1111/polp.12051.

- Lazarsfeld, P. F., and R. K. Merton. 1948. Mass Communication, Popular Taste and Organized Social Action. Indiana, Bobbs-Merrill, College Division, pp. 95–118.

- Llanos, B. 2013. “OJOS QUE (Aún) NO VEN, Nuevo Reporte de Ocho Países: Género, Campañas Electorales y Medios en América Latina.” ONU mujeres. https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/ojos-que-a%C3%BAn-no-ven.pdf.

- Long, M., R. Dawe, and E. Suhay. 2021. “Gender Attitudes and Candidate Preferences in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Primary and General Elections.” Politics and Gender 18 (3): 830–857. doi:10.1017/S1743923X21000155.

- O’Connor, B., R. Balasubramanyan, B. Routledge, and N. Smith. 2010. “From Tweets to Polls: Linking Text Sentiment to Public Opinion Time Series. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media.” International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media 4 (1): 122–129. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/From-Tweets-to-Polls%3A-Linking-Text-Sentiment-to-O%27Connor-Balasubramanyan/3fee8e69b8e2df25030cf331b28b37f4dd13086c.

- Okimoto, T. G., and V. L. Brescoll. 2010. “The Price of Power: Power Seeking and Backlash Against Female Politicians.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36 (7): 923–936. doi:10.1177/0146167210371949.

- Paatelainen, L., E. Kannasto, and P. Isotalus. 2022. “Functions of Hybrid Media: How Parties and Their Leaders Use Traditional Media in Their Social Media Campaign Communication.” Frontiers in Communication 6: 817285. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2021.817285.

- Ridgeway, C. 2007. “Gender as a Group Process: Implications for the Persistence of Inequality.” In The Social Psychology of Gender, edited by S. Correll, 311–333. Amsterdam, Elsevier/North-Holland.

- Rojas, H. 2008. “Strategy Versus Understanding: How Orientations Toward Political Conversation Influence Political Engagement.” Communication Research 35 (4): 452–480. doi:10.1177/0093650208315977.

- Rosenthal, R., and L. Jacobson. 1968. “Pygmalion in the Classroom.” Urban Review 3 (1): 16–20. doi:10.1007/BF02322211.

- Rudman, L. A., and K. Fairchild. 2004. “Reactions to Counterstereotypic Behavior: The Role of Backlash in Cultural Stereotype Maintenance.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 87 (2): 157–176. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.157.

- Rudman, L. A., and P. Glick. 2008. The Social Psychology of Gender: How Power and Intimacy Shape Gender Relations. New York, Guilford Press. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2008.04.003.

- Rudman, L. A., A. G. Greenwald, and D. E. McGhee. 2001. “Implicit Self-Concept and Evaluative Implicit Gender Stereotypes: Self and Ingroup Share Desirable Traits.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 27 (9): 1164–1178. doi:10.1177/0146167201279009.

- Skoog, L., and D. Karlsson. 2022. “Perceptions of Polarization Among Political Representatives.” Political Research Exchange 4(1)), doi:10.1080/2474736X.2022.2124923.

- Stromer-Galley, J. 2002. “New Voices in the Public Sphere: A Comparative Analysis of Interpersonal and Online Political Talk.” Javnost – The Public 9 (2): 23–41. doi:10.1080/13183222.2002.11008798.

- Sullivan, K. V. R. 2021. “The Gendered Digital Turn: Canadian Mayors on Social Media.” Information Polity 26 (2): 157–171. doi:10.3233/IP-200301.

- Thomas, M., A. Harell, S. Rijkhoff, and T. Gosselin. 2020. “Gendered News Coverage and Women Heads of Government.” Political Communication 38 (4): 388–406. doi:10.1080/10584609.2020.1784326.

- United Nations Women. 2021. Mujeres en la política. Digital library. United Nations entity for gender equality and the empowerment of women & inter-parliamentary union. https://www.unwomen.org/es/news/stories/2021/3/press-release-women-in-politics-new-data-shows-growth-but-also-setbacks.

- Vann, P. 2014. “Changing the Game: The Role of Social Media in Overcoming Old Media’s Attention Deficit Toward Women’s Sport.” Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 58 (3): 438–455. doi:10.1080/08838151.2014.935850.

- Wagner, K. M., J. Gainous, and M. R. Holman. 2017. “I Am Woman, Hear Me Tweet! Gender Differences in Twitter Use Among Congressional Candidates.” Journal of Women, Politics and Policy 38 (4): 430–455. doi:10.1080/1554477X.2016.1268871.