ABSTRACT

This article examines the exploitation of political war myths within military patriotic youth clubs in Russia, predominantly based on content from social media accounts. These clubs frequently propped up the ongoing warfare in Ukraine with narratives and symbols, visual imagery, and reproduced slogans – all originating in the Second World War. The article coins the term ‘war merging’ to conceptualize the phenomenon and discusses its characteristics and implications. Only occasionally referring to actual historical events, this form of myth exploitation makes blatant appeals to learned symbolic attachments and dominating narrative templates of Russia at war. The practice seeks to legitimate the current warfare in Ukraine among the Russian youth, but also serves to guide the plotting of new memories for how this war will be remembered in the future. By merging these wars symbolically, the invasion of Ukraine is inscribed into Russian collective memory as just, defensive, and heroic – as a continuation of the mythologized ‘eternal war’ in Russian hegemonic culture.

Introduction

In the Russian public sphere, the ongoing warfare in Ukraine is frequently framed with reference to the Great Patriotic War (GPW), in the sense of a hegemonic and always developing political myth about the Soviet defence against, and subsequent victory over, Nazi Germany (1941−1945). The framing takes many forms, from explicit comparisons between aspects of the two wars, to commenting on the war by means of practices, labels, symbols, slogans, and phrases associated with the GPW. Employing the GPW to prop up a war of aggression against Ukraine, itself a major contributor to the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany, is teeming with narrative contradictions. Yet, it has been a recurring theme in Russian propaganda against its neighbour. The instrumentalization of the myth in Russian-Ukrainian hostilities has been evident since 2014 and even before (Zhurzhenko Citation2015). Following the invasion of February 2022, the kinetic warfare was coupled with an increased mobilization of mnemonical resources within Russian state and society.

This article considers instrumentalization of memories within so-called military patriotic clubs (MPCs) in the first three months following the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In the Kremlin’s rhetoric and mass media reports in the same period, the GPW-frame was one of several used to legitimize the war. Notably, the MPCs had a much more focused approach. These actors typically instrumentalize heroic historical narratives for indirectly supporting the contemporary military. From 2022, they did it more directly and bluntly than before. The resulting mix was a striking symbolic mishmash, in which the war in Ukraine is presented as a continuation of the GPW, or indeed as the one and same war – blurring out both the pastness of the past and the presentness of the present. In applying a GPW-frame to interpret what in reality was a very different kind of war, these mnemonical actors consistently resorted to vagueness and abstraction. They ended up employing symbols and traditions as purely emotional tools – grounded in their positive associations with the GPW but without any explanation to their relevance. The phenomenon, which this article discusses under the term of ‘war merging', was not simply trending in the period, but in fact the dominant way in in which the MPCs represented the war and expressed support for the Russian troops and Putin’s political regime.

As will be discussed at length later in this article, this choice of framing is not by chance. The GPW is by far the dominating historical frame employed in Russia, owing both to the event itself, the popular interest in it, and the event’s vociferous politicization through later Soviet and Russian history. Already under the auspices of general secretary Brezhnev, its commemoration became so hefty and ritualized that scholars have addressed it in terms of religion and cult (e.g. Kucherenko Citation2011; Domańska Citation2022). This uniquely elevated status of the GPW and its firm grip on popular consciousness has been paramount to make war merging feasible or indeed possible. As I will argue, war merging tends to draw on internalized (and misconceived) ‘deeper truths' and emotionally laden symbols rather than facts and arguments.

A few years ago, Julie Fedor and colleagues (Citation2017, 5) observed a tendency, ‘perhaps even a new phenomenon that goes beyond the usual instrumentalization of the past … a new temporality in which elements of past and present are fused together, and linear historical time collapses'. They elaborate: ‘The radical blurring, even dissolving, of the boundaries between past and present, and fantasy and reality, enacted through the performance of memory' (ibid., 6). The radicalism Fedor and colleagues point to is key here, as all myth making could be claimed to reject the historicity of events and insist on their continuing presence. Several other scholars have made similar observations since 2014, particularly with regards to Russian media coverage (e.g. Horbyk Citation2015; Snyder Citation2018; Luxmore Citation2019; Spiessens Citation2019; McGlynn Citation2020). The concept of war merging builds upon and extends these perspectives.

Methodology and structure

As its empirical point of departure, this study takes the public profiles of local and regional military patriotic clubs on the prominent Russian social media platform VK. I scrutinized club activities and practices, posted and shared content, and occasionally the links the clubs provided. Some of the material explored in this study may be semi-permanent by virtue of its electronic form, yet by function it represents something fleeting and nonpersistent. While the messaging may be consistent over time, the individual posts are everyday reports hardly intended for close scrutiny or contemplation. The research material consists of digital micro-sources, including short texts, photos, drawings and images, videos, audio-clips, and links.

My collection and approach to the material pursues two tracks, which follow from the different epistemological status of the material. For a large part, my interest lies with the physical reality and the local communities the groups are part of. As noted by Hauter (Citation2023), using new online media as a data source has huge potential far beyond the study of online environments as such. The study at hand is not concerned with researching digital culture or online communities (netnography) – nor primarily with the specific character of social media (SMR). Rather, this first track is basically making use of online sources as we would otherwise use organization reports, member bulletins, or local traditional media – as sources to the ongoing activity of the clubs. Compared with direct observation of practices, it allows the researchers to be in several places at the same time, including territories otherwise inaccessible. Storage makes it possible to move back and forth in time, and the amount of available data is practically endless for qualitative purposes. The researcher can examine the actors without interfering with their everyday activity. In short, online media provide (mediated) peepholes into local activity that is otherwise off bounds for most researchers in times of war.

Local clubs tend to be less concerned with what messages and information their convey through their facades than what would be true for their mother organizations. Several of the clubs post dozens of photos of a single activity, and sometimes long, seemingly unedited, movie clips from events. Caveats remain, however, and include possibly selective reporting, as well as reporting for the benefit of imitating activity (to fulfil quotas for presidential grants etc.) In comparison with direct observations, moreover, the richness of detail is obviously limited.

The second track of the analysis is more concerned with aspects of communication to an audience. Certainly, the communicative aspect is present for all data posted on social media, but for shared/reposted material it is our primary concern. These posts tell us more about the interests and identities of the posters than about actual activity. In the case of these local clubs, their everyday audience on social media is presumably limited to local communities, parents, teachers, enthusiasts, and neighbouring clubs – as well as mother organizations and perhaps other patrons monitoring and guiding their activity (and sometimes reposting their content). Most of the members of the VK-groups seem to be the MPCs members themselves, rather than other interested parties. I therefore approach the reposted content as examples of what the club members themselves are subjected to as part of their MPC engagement. The dynamics of reporting and reposting between various state and state-supported actors in terms of cross-checking, networking and prestige gathering would provide for interesting research, yet they are beyond this particular study.

I have reviewed the relevant public postings on VK from nine MPCs’ profiles in the Arkhangelsk and Murmansk regions between February 24th and May 24th, 2022. The sample includes a diversity of urban and rural clubs of different affiliations, containing clubs from the cities of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk, but also from the smaller settlements of Apatity, Pechenga, Zapolyar’e, Severomorsk and Nikel’. Among the nine clubs, five are squads (otryady) under the military patriotic movement Yunarmiya, and another is affiliated with the large (but much smaller than Yunarmiya) organization Vympel. The profiles belong to local clubs and local departments of clubs, typically with between 10 and 30 active members. Due to data sensitivity (the involvement of minors) and the limited expected audience of these clubs, exact actors will not be identified in the presented research.

The overarching purpose of the study is to assist our understanding of recent developments of memory politics in Russia, in particular in times of war. Mass consumption of online propaganda-material combined with GPW-monomania (see below) and a repressive and authoritarian political regime has paved the ground for intensified information campaigns to instrumentalize collective historical myths. The circulation, reproduction, and not least integration of these myths into public life bears direct impact on how the ongoing war is apprehended among the Russian population as well as how it will be remembered in the future. For this reason, war merging has significance both for those researching with political myths and collective memory and for those concerned with public support for Russia’s war in Ukraine.

The article answers a call for meso-level studies of memory politics (see Philpott Citation2014; Verovšek Citation2016), and the interaction between state and society in reproducing myths within authoritarian regimes. The youth organizations may be apprehended as the bottom layer of a ‘propaganda vertical' through which the authorities strive to convince the population that the war is just and necessary. The vertical, however, is not operating without horizontal input. Rather, the various club activities reveal how official policy is implemented in a complex environment, influenced by social practices, pedagogical norms, local specificities, and actor preferences. The visual material circulated by the clubs frequently consist of graphics, memes, and videoclips that appear as creative extensions of political brands of semi-official origin – everything filtered and selected by local club-leaders before introduced to their youth groups. The local MPCs are thus mediators between a securitized and centralized policy field of patriotic education, creative online communities producing shared content, and the local communities with whom they work. The MPC members may be seen as propagators of patriotic narratives in these communities. At the same time, they are also themselves a primary target of this propaganda.

Readers should note that when I employ ‘patriotic', ‘patriotism', and similar terms in this article, I do not make any assumptions about the actual patriotism of neither the clubs nor the policy makers. Rather, the terms in Russian context denominate a policy field and a discourse to which the actors subscribe. Also, I make no assumption that patriotism is an inherently good thing but rather see it as a phenomenon of political psychology that may take many different forms – including potentially harmful ones (see Bar-Tal and Staub Citation1997).

The article proceeds by introducing the readers to some aspects of Russian memory politics related to the legitimization of contemporary warfare. Afterwards, I move my attention to the war in Ukraine and zoom in on the responses to the 2022 invasion among the examined MPCs. Based on this initial review, I flesh out the concept of war merging to make sense of this new reality and link it to previous research and perspectives. Following this section, I present and discuss various examples of how the MPCs employ war merger tools in different ways, using examples and illustrations from the online field. On the last pages of the article, I discuss some lines of interpretation and their implications for memory politics in Russia as a research field.

Memory during wartime

When fighting a war, it is paramount to sustain support on the home front. Societal support is useful for ensuring a steady flow of motivated recruits, and the belief in a just cause will increase tolerance for the hardships the war entails for the population, including casualties and effects of sanctions. While ensuring support is important to any nation in war, Levite and Shimshoni (Citation2018, 98) find Russian warfare to have been particularly ‘society-centric' all the way back to tsarist times, meaning that Russia (and the Soviet Union) has put great emphasis on the civilian populations involved in wars – be it on the side of the enemy, its domestic audience, or third parties. Russian media has worked systematically to prop up Russian warfare in Ukraine since 2014 with historical narratives, and since 2022 Russia has gradually introduced wide reaching changes in school curricula as well as in legislation to control the dissemination of narratives. It has also engaged in large scale manipulation of the occupied population – using everything from mass media control, educational changes, and military patriotic education to outright deportations and more.

Historical analogies have been put to the service of building support for warfare at least since the previous century. Under the existential threat posed by Nazi Germany, for instance, the Soviet Union decided to speed up its policy of rehabilitating Russia’s imperial past, not least well-known heroes from its many battles (Brandenberger and Platt Citation2006). The Soviet effort to defend had barely begun when Emelyan Yaroslavskiy in a Pravda article dubbed it the ‘Great Patriotic War’ (Velikaya Otechestvennaya voyna), with an obvious reference to the ‘Patriotic War' (Otechestvennaya voyna) against Napoleon. While every international war since then have taken place outside Russian territory, both Soviet and Russian actors have since used the GPW to frame many of its adventures as legitimate, defensive, and just (Luxmore Citation2019). Already in 2014, the war in the Donbas was framed as a ‘re-enactment of The Great Patriotic War' in Russian mass media (Horbyk Citation2015, 50; see also Spiessens Citation2019; McGlynn Citation2020).

The 2022 invasion of Ukraine was of different proportions than previous military adventures of Post-Soviet Russia. Following up on its full-scale invasion, Russia introduced a more brazen regime of repression at home. Russian authorities securitized reporting on the war, and important independent news outlets were blocked, shut down or scared into exile. Even if not (yet) mobilized in a military sense, Russia was mobilizing both mnemonic and informational tools to support its kinetic warfare.

In his infamous speech on February 24th, President Putin claimed to be fighting Ukrainian ‘Nazism' above all. In the speech, he used the term in various forms a total of six times, mixing historical references with the situation of today (President of Russia Citation2022a). Important mnemonic actors followed suit, such as the Central Museum for the history of the GPW, which in June opened an exhibition which a Meduza journalist dubbed a ‘bizarre mishmash' for how it smeared together current and historical events (Koroleva Citation2022). State media, and in particular the main TV-channels, continued and expanded its role in casting the war as a renewed fight against Nazism in Ukraine, the US, Germany, and elsewhere. The Kremlin made use of other mnemonic resources from its arsenal too, building upon Putin’s repeated quasi-scholarly statements on Ukrainian history in recent years (Pertsev Citation2022). Within the military patriotic discourse, however, references to the GPW reigned supreme.

Apparently, the invasion came as a big surprise to most Russians, including both elites and the deployed troops. In Russia, as well as elsewhere, thousands of Russians went into the streets to protest. The international press worked overtime to produce updates and millions were glued to the news and discussed whether or not Kyiv would fall. At this point in time, however, the MPCs appeared completely unaware of the war’s existence. Most of them had not commented on current events previously and felt disinclined to change this modus operandi. It seems plausible to assume they would not risk sticking their neck out in support of whatever the announced ‘special military operation' would turn out to be. Instead, they apparently chose to wait it out and pretend nothing had happened. They posted activities as normal, commemorating the Day of the Defender of the Fatherland on February 23 without reflecting on the special situation. One club posted a long series of photos with members proudly posing with heaps of cardboard they would recycle. As late as March 22, a Yunarmiya squad in Arkhangelsk oblast arranged a somewhat bizarre event under the circumstances, ‘Russia smiles to the world', where a so-called flash mob (fleshmob) of children formed a giant smiley ‘to show that Russia speaks for peace and friendship'.

By the beginning of March, it had become evident that Ukraine would not collapse any day soon. It also became clear that Putin was determined to sustain a large war in an effort to eventually subdue Ukraine. Many countries joined an unprecedented sanctioning regime against Russia and provided weapons for its defence as well as economic and other support. A number of international companies withdrew from Russian markets, and Russia was expelled from numerous international events and organizations. The Western press and politicians poured out condemnations and reports of Russia’s indiscriminate bombing. A few days after the invasion, therefore, Russian authorities rolled out a series of events where they informed Russian schools, parents, and pupils that they were the targets of Western information warfare (Vinogradskaya Citation2022). This could be interpreted as a signal for the educational sector to take substantial measures and had obvious ramifications for the MPCs as well.

In response to these developments, the MPCs appeared to be feeling around for a new mode of operation. The first signs of a pro-war stance appeared for some clubs at the end of February, and for others as late as in mid-March, three weeks after the invasion commenced. Some of the clubs eventually commented on the war through participation in a wave of ‘all-Russian campaigns’ to be explored below. The language they used to express support was usually relatively moderate in comparison with the aggressive rhetoric in the Kremlin or provocative talk shows on Russian TV. Moreover, their attention to Ukraine did not seem to interfere with the everyday focus on sport events, military training, patriotic camps, and competitions. Rather, wartime support of the troops appeared at this point of time on top of, and sometimes entwined with, ordinary activities.

The intensive warfare in Ukraine the spring 2022 left footprints on the social media profiles of MPCs in several ways. Firstly, the MPC members participated in events of supporting the troops that had little to do with historical references. They reported from some pro-Kremlin rallies and partook in the wave of flash mobs that appeared all over Russia at the time, using their bodies to form the letter Z (and occasionally V) in the school yards or elsewhere – and sharing the photos online. Some of them also published declarations of support on their VK-profiles, void of direct historical references.

Secondly, the clubs wrote letters to (unknown) soldiers at the front, made drawings, and participated in Ukraine-related art competitions. Occasionally, the clubs also showed their support for the war through more performative or symbolic action with reference to the GPW. The MPCs often posted reports from these activities together with a rich selection of photos providing material for this research.

Finally, the clubs made various indirect declarations of support through posting and sharing relevant content on their social media profiles. Here, the diversity of the research material is much greater in both form and content, including videoclips, music, and graphics – often with short slogans or comments added by the MPC leaders before they post or repost. This material's source of origin is often unknown.

There were occasionally Ukraine-related posts that go beyond this rough classification, and I have no ambition to present all the posts in equal measure.

What is war merging?

To make dubious claims of historical continuity is part of what it means to be a nation. Russia’s hegemonic representation of its national history has arguably taken this to the extreme, portraying its entire history as that of a ‘thousand-year-old state' (Malinova Citation2017). In this storyline, perpetual warfare is a cornerstone. By a complex process driven along by state actors, professional historians, cultural entrepreneurs, and others, Russia’s wars through the centuries ‘are pushed into a single frame of reference that, as held in collective memory, fosters a distinct national identity both born and bred in war’ (Carleton Citation2017, 3). The ongoing war with Ukraine gives us live and online access to how a new war is plotted into this narrational and symbolic mainframe.

In line with Fedor and colleagues (Citation2017, 8), I seek to understand war merging’s significance as a war time phenomenon, and how it ‘can make people see the current war as an unfinished battle of World War II'. We can define war merging as a tool of manipulation that blurs the boundaries between contemporary wars and prevailing political myths about wars of the past. The practise is presumably motivated by the wish to either make sense of, or legitimize, contemporary warfare. War merging does not explicitly compare wars, as this would set them apart as much as to merge them. Rather, it appeals to emotions, associations, and the potency of internalized narrative templates for the ongoing war to appear as a continuation or a re-enactment of a pervious war.

Importantly, our concern here is not with the collective memories themselves, but with tools and a symbolic repertoire that refer to a hegemonic framing of them. War merging mediates and manipulates both the past and the present, but it is clearly the latter which is decisive. The historical past is represented only at a great level of abstraction – merely hinted at by mnemonical signifiers (Feindt et al. Citation2014) well known by the target group.

James Wertsch’s (Citation2021, 31−85) cross-disciplinarian perspective on narratives suggests that our ability to narrate stories is a vital part of our cognitive abilities as individuals. Not only is it fundamental to how our species sort our memories and over time turn them into mental habits. Also, these habits structure the ways new memories take hold – how ‘knowledge is acquired, stored, recalled, or extended to other domains' (Brubaker cited in Wertsch Citation2021, 78). By making cross-temporal references and merge wars, political myths are sustained and reproduced, as new experiences are regularly ‘slotted' into a pre-ordained narrative. Memory is therefore not only a vestige of the past used to interpret the present, but also crucial for the imprint of new memories. We may think of it as a symbolic anchoring of new experiences, so that citizens may mentally process them as fundamentally legitimate even in lack of real information. Through the practice of war merging, parts of the Russian public and youth experience the war not directly but mediated through state-approved symbols loaded with positive meaning. For some, these symbolic anchors may become a primary association by which they come to remember the war, at least its early phase.

War merging is hardly unique to Russia, but its blatancy and pervasiveness is none the less remarkable. This is due to several factors, including the unique role played by the GPW-narratives in today’s Russia, as well as the importance of the central state in promoting the hegemonic narratives top-down. These factors make it necessary to approach the implications and context of war merging in national context.

Military-patriotic clubs as an arena of war merging

Military patriotic education became state policy in Russia from the late 1990s, and has since steadily increased in prominence. Supporting the activities of MPCs was always an integral aspect of this policy, regulated and supported not least through designated ‘state programs' (Sanina Citation2017). From 2015/2016, the stress on MPCs in particular changed, as the Russian state decided to establish Yunarmiya as a ‘military patriotic movement' for Russian youth, in tight cooperation with the Russian ministry of defence and endorsed by Putin himself. Since then, many existing clubs have been co-opted into the movement – and many new ‘squads' has been established throughout Russia through the schooling system. In contrast to previous military patriotic initiatives, Yunarmiya aims to become a mass organization, and reportedly hit 1.2 million members by 2022 (yunarmy.ru keeps a running count, possibly exaggerated). It is also taking over much of the ‘patriotic infrastructure’ that has been available to most MPCs through state support mechanisms. At the same time, more or less independent MPCs still exist and are not marginalized within the policy field. Furthermore, the degree of coherence and unity within Yunarmiya is varying: Some co-opted squads largely pursue their old activities under new banners.

At a basic level, military patriotic activity in Russia is marked exactly by how it combines a focus on the contemporary Armed Forces (including basic military training) with historical themes and commemoration (Bækken Citation2022). The two components are implemented side by side and often entwined with each other. Frequently, military patriotic activity take place in specially prepared rooms in schools or in patriotic centres, including school war museums, ‘Yunarmiya rooms', or ‘Yunarmiya houses'. All of these may include artefacts from, or depictions of, WWII – along with photos of Putin and Sergei Shoigu as well as instructive posters on first aid and automatic rifles. The past is also utilized in the naming of sport events after war heroes, or in timing these contests to coincide with commemorative events. Sports venues as well as patriotic youth camps are often decorated by historical symbols. In the 2022 campaign 'Records of Victory', the value of sports and a healthy lifestyle was explained by reference to their usefulness for winning the GPW. In short, the military patriotic setting itself is construed to bring past wars closer to the realities of today – be it in peace or war.

War merging: a basic toolkit

War merging takes many forms, and most are less than subtle. The following review is intended to highlight some important ways in which war merging comes to bear in the examined material.

Instrumentalizing dates, places and historical practice

War merging can make use of both special commemorative events and places of memory to attach them to contemporary warfare. Some MPCs are well acquainted with local memorials and use them for various occasions – a way to connect the youth activity to the story of the GPW. Some of the Yunarmiya squads that partook in a campaign to write letters to Russian soldiers in Ukraine, also found it opportune to take the letters out for a photo session in front of a heroic war monument. The purpose of these visits was not made explicit on social media, but surely the Arctic winter hardly made it practical. Presumably, the symbolic act would somehow imbue the letters and their recipients with the ‘heroic spirit’ of the forefathers.

The past and the present may also be linked by the means of declaring support for the war on special commemorative dates or events. An event that may illustrate this took place on the ‘Day of the Khibin Front' to commemorate the Soviet defenders of the Arctic. At the occasion, a prominent MPC leader took the opportunity to conduct a car rally (avtoprobega) in support of ‘Putin and the Russian Armed Forces’ – purporting some kind of link between the invasion of Ukraine and the defence of the Arctic. In general, however, such exploitation of historical events is surprisingly rare in the material. A lack of war merging on May 9th, for instance, is striking in view of how Putin himself made use of the occasion (President of Russia Citation2022b). The same can be said of the so-called ‘Reunification Day' of March 18th when Russia annexed Crimea. An important caveat here relates to the type of data: examined for this study the VK material tends to be richer on photos than replications of uttered words. Speeches on commemorative dates may therefore follow Putin’s lead, even if the material cannot document it.

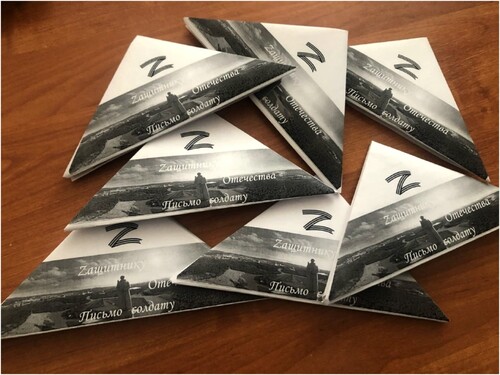

A practice that deserves mention is how some clubs folded their letters to Russian soldiers in a specific triangular shape (). Soviet soldiers often sent letters from the front to their families folded in this particular shape, which made them function both as letters and their own envelope – saving scarce paper. Triangular letters in the mailbox meant a friend or relative still alive on the front. While the role of the sender and the (purported) receiver here is reversed, the gesture functions as a sort of re-enactment that symbolically fuses the civilians and the soldiers together across time and space. The historical background is briefly explained by the MPCs in question, but it is not argued why these letter shapes would be relevant in today’s situation.

Joint symbols of victory

The St. George ribbon (grigoryevskaya lenta) is Russia’s most favoured symbol to support its troops. The ribbon is a symbolic merger in itself – a combination of military orders from imperial and Soviet history that continues to take on new forms and meanings (Kolstø Citation2016; Danko Citation2021).Footnote1 After the war, it became an important Soviet symbol of the 1945 victory, but it had nowhere near the status of today (ibid.). In the early 2000s, the ribbon was reinvented as a patriotic symbol and soon grew in prominence. From 2014, it was increasingly associated with Russia’s war in Ukraine and therefore shunned by many of Russia’s neighbours.Footnote2

In the reviewed material, the St. George ribbon appears very frequently and serves to bridge the gap between the Soviet and the Russian patriotic traditions. In the letter campaigns, for instance, the ribbon figured on many letters designs and drawings. It also figures in much shared content circulating amongst the clubs. While the ribbon’s symbolic content has been constantly evolving, the way it is used in conjunction with other symbols in the material indicates that it is still strongly associated with the GPW and 1945. One club declared its symbolic attachment explicitly, calling it ‘one of the most important symbols of the Great Victory'. An information video that was circulated among MPCs in May presents it as a ‘symbol of Victory Day', yet also of ‘military prowess and glory'. The club urged members to wear it ‘with pride in our Motherland’s heroic past'. Because of its symbolic plasticity, the St. George ribbon is used on everything from posters of soldiers in battle gear to children’s drawings hopeful of peace.

The other prominent symbol to declare support for the invasion is the (latin) letter ‘Z'. The Z was apparently first used as a sign to identify military hardware involved in the operation, but it quickly aquired additional meaning. Its rise to prominence was apparently spurred along with the help of state media and various state institutions (Kashperska Citation2021). Within the analysed material, the symbol appeared in three main ways: Firstly, it was the chief symbol of the flash mobs organized in support of Russian troops in Ukraine – where the participants together formed the letter ‘Z' (and occasionally ‘V’) with their bodies. Secondly, the Z appeared frequently in the graphical material the clubs put to use. Notably, it appeared most often as a St. George band folded in Z-shape, or alternatively drawn with orange and black stipes. Thirdly, the Z was used to substitute the corresponding Cyrillic letter in war time slogans, often with added hashtags. These were most frequently reproductions of GPW-slogans, such as ‘For peace!' (Za Mir!) or ‘For Victory!' (Za Pobedu!). Even when slogans are not distinctly Soviet —such as ‘For Truth!' (Za Pravdu!), ‘For the President!' (Za Prezidenta!) or ‘For Putin!' (Za Putina!)— they evoke associations to a whole set of Soviet slogans of similar type, perhaps most (in)famously ‘For the Motherland! For Stalin!' (Za Rodinu! Za Stalina!). To summarize, the war’s primary symbolic innovation, the Z, was quickly fortified by the use of GPW references.

Merging the enemies

To depict the enemies as representatives of eternal evils is common to justify extreme measures, including wars. While the noun ‘fascist' in Russian parlance may not quite signify an eternal evil, it has since long degraded into a general derogatory of Russia’s (purported or real) enemies. Whereas Western societies after WW2 war paid much attention to the internal workings of Nazism, its totalitarian ideology, anti-Semitism, and Holocaust, Soviet discourse focused more on Hitler’s dream of world dominance, the anti-Slavic aspects of Nazi ideology, and the war Hitler launched upon the Soviet Union (Luxmore Citation2019).

The framing of Russia’s enemies in Ukraine as fascist or (more recently) Nazi has been present in Russian state media at least since 2005, and mainstream since 2014 (Gaufman Citation2015). While it is frequently used in conjunction with (marginal) ultra-right groups in Ukraine or the partial rehabilitation of Stepan Bandera (Portnov Citation2017), Russia’s labelling should be understood in light of political developments in Russia itself – and its dependency upon GPW frames to mobilize support. Notably, labels like ‘fascist' and ‘Nazi' are also put on liberal critics of the Kremlin at home (Luxmore Citation2019, 826).

In the reviewed material, enemy labelling most often take place indirectly as part of positive messaging. The focus is not on why the fascists are enemies (the label says it all), but on how they are the targets of Russian warfare. One photo from a local patriotic gathering, for instance, reveals a background banner with the title ‘For Russia! (The fight against fascism past and present)’. More frequently, the (merged) fascist enemy is labelled by means of reposted graphical content. The centrepiece of one popular poster is a modern soldier with a statement superimposed on the graphic: ‘The Russian soldier is once again liberating Europe from Fascism!!!'. Labelling enemies as fascists and Russians as heroes is often two sides of the same coin: Whoever fighting Russians are fascist, and in turn the Russians are heroes because they are fighting fascists.

On occasion, the enemies are given certain attributes. In the wording of a reposted movie-clip from the ‘ultrapatriotic' and conspiratorial TV-channel Tsargrad, the Ukrainian ‘Nazis' keep children and mothers locked in basements without food and drink. One graphic/poster depicts soldiers on a background of fire and smoke with the following text accredited contemporary poet Dmitriy Rachuk: ‘The Fascists are crawling out of the cracks. Our grandfathers did not finish them off. From now on, the grandchildren have taken on the enemy, for the people of Donbas to live peacefully'. While it may bring associations with insects, the 'crawling' is more likely a reference to yet another label from WW2, namely ‘fascist reptiles' (fashistskiye gady). The poem is also a perfect illustration of what Fedor and colleagues noted in 2017 (8); the notion that WW2 is ‘unfinished'.

An atypically long post from as early as late February attempts to legitimize the war by calling upon the memory of the Odesa fire of 2014, in which many pro-Russian separatists died. He calls it the Khatyn of Odesa (Odesskaya Khatyn) – a reference to a well-known massacre in today’s Belarus where Ukrainian Nazi-collaborators participated (Rudling Citation2012). ‘Russia now fights a defensive war to protect our security and the rights of the Donbas population', the MPC leader continues; ‘We are cleaning our neighbouring country from ‘Nazi filth (skverna natsizma)'.

Historical Nazis appear in shared movie clips that are cross-cutting historical and contemporary content. One of the reviewed movie clips is particularly brazen in this exercise, pairing the ultra-nationalist group Pravyi Sektor (Right Sector) with historical Nazis and Swastikas.Footnote3 More often, however, it is not clear who exactly is labelled – Ukrainian nationalists, Zelensky’s government, the Armed Forces of Ukraine, or its Western supporters.

Except for the lone reference to Khatyn, the connection between the contemporary and the past enemy is rarely specified in any way. In the reviewed videoclips, for instance, not a single Ukrainian nationalist with a Nazi tattoo appears, and no explicit claims are made about enemy atrocities. Rather than providing any information that would undermine the moral integrity of the enemy directly, the producers and distributers of this material appear to believe that an unsubstantiated Nazi label is sufficient for mobilizing support for Russia’s war.

The pantheon of war

One of the original purposes behind the State Programs of Patriotic Education, active since 2001, was to revive Soviet traditions from the 1960s and 1970s (Bækken Citation2019). In the everyday life of Russian MPCs, the link is evident in everything from traditional Soviet military games, commemorative practices, and the replication of famous Soviet educational programs and slogans like ‘Ready for defence and labour!'. For Yunarmiya in particular, the aesthetics, colour-themes and organizational symbols also carry clear references to its Soviet predecessors. Much of the information on military history shared on the MPC for educational purposes (such as documentaries) are in fact Soviet productions.

In line with this ‘double commemoration’, in which GPW-commemoration itself is a reinvention of Soviet commemorative practices, the clubs also reproduce patterns from Soviet propaganda posters. In this context, one much used theme is to present soldiers of the past and the present side by side in the same pose, often with the past heroes figuring as ‘ghosts' in the background. This is visualizing the popular theme of grandfathers (dedy) and/or more distant ancestors (predki) fighting alongside their descendants (vnuki), thus presenting historical wars as chapters in the same book. In addition to this use of historical reference, the very theme is replicating Stalinist wartime propaganda, which in the same fashion imagined the struggle against Nazism as spiritually supported by heroes of past wars.

In several graphics and videos, time labels are used, but rather for combining than for fixing events in time. The most frequently appearing time stamp is ‘1941−2022', suggesting an ongoing struggle and an unfinished war. In other cases, visual cues make it hard to discern which war is depicted. When a child draws a smiling soldier with a red star on his helmet, an old-fashioned rifle, and a large missile labelled ‘Russia', it seems war mergers have been successfully spreading confusion.

The analysed material provides several other examples of how new heroes are added into the all-Russian pantheon of war as events unfold. Perhaps the most striking example is a shared videoclip in which Russian soldiers from today’s war are repeatedly crosscut with historical heroes from the GPW as well as those from famous battles in 1240, 1242, 1380, 1709 and 1812. The GPW is in other words not the only historical point of reference, even if it is by far the most prominent.

Victimhood

In times of a large war marked by high casualties on both sides, an overly strong focus on suffering and victimhood would possibly lead to dwindling popular support. The Russian actors thus censored, rather than exaggerated, Russian casualties and suffering. At the same time, the official storyline necessitates sacrifice and something to sacrifice for. At the outset, it therefore leaned heavily on the civilian suffering in the Donbas to bolster the image of the enemy as cruel fascists and necessitate war and sacrifice on the part of Russia as the story’s protagonist. Stories of victimhood therefore spun around Nazi atrocities and alleged parallels to Ukrainian treatment of the population in the eastern parts of the country (which Ukraine in fact did not control). These stories were important in constructing a justification before the invasion and in the first days of fighting, by alleging that Ukraine was planning or already conducting a ‘genocide’ against the Russian-speaking population in the Donbas.

In the reviewed material from the MPCs, stories of suffering and victimhood are quite limited. Moreover, in the few cases included, there are few obvious attempts at war merging. One club engaged the youth in collecting clothes for East-Ukraine under the hashtags #VremyaPomogat’ (Time to help) and #MyVmeste (We stand together). Other clubs shared a photo of a lit candle to commemorate victims of a much-reported incident in the Russian press, where 23 civilians were reportedly killed by a Ukrainian missile attack on Donetsk. Finally, one club shared a link to an all-Russian lesson on the crimes of Nazi Germany on occupied territories, part of the larger educational campaign ‘Without a period of limitation' (bez sroka davnosti). The focus was reportedly on crimes conducted by ‘Germany’s fascists, Ukraine’s Banderovites and Estonia’s chastisers' (Talanova Citation2022), thus clearly suggesting a link to today's warfare. The text accompanying the link, moreover, warns against present attempts to 'revise' the term 'genocide'.

The eternal victory

Instead of evaluating the development of the war on the ground, the patriotic crystal ball envisions victory based on a purportedly unbroken chain of victories in the past. The thesis that ‘Russia always wins' precedes the Bolshevik revolution and has been remarkably resistant to change even in face of considerable counterevidence (e.g. 1853−5, 1904−5, 1914−18) (Carleton Citation2017). In the Soviet Union, what is sometimes dubbed a Victory Cult was established after WW2 (Brunstedt Citation2021). Later, it came to survive the humiliating Soviet loss in Afghanistan as well as Russia’s inability to reaffirm its own integrity in Chechnya. Today, the thesis of eternal victory bolsters pride in Russia’s war: Russia is going to win because it always wins. And if Russia wins, its cause must be just. An event in mid-March is symptomatic: When the Russian offensive towards Kyiv had embarrassingly stalled North of the capital, a group of children from one Yunarmiya squad lined up with one paper sheet each, together spelling out the word ‘Victory'. The text accompanying a photo of the event links Yunarmiya's declared values of ‘honesty', ‘good deeds' and ‘kindness' to the necessity of supporting the Russian troops.

In one youth art contest on patriotic themes, one reposted drawing depicts a grey-haired Soviet soldier (ded) side by side with a younger one (vnuk)– presumably Russian. Both are wielding weapons developed later than WW2, which may be on purpose or not. In the right top corner, we see the text ‘Together for Victory for Russia', (with Latin Zs and Vs). The background is split into two parts by a wavy line indicating fluidity rather than separation. At the one side we see Soviet soldiers planting the Victory banner of 1945. On the other is a Russian flag attached to the top of what appears to be the President’s office in Kyiv. The helmets have a red star and a Z, respectively, and the St. George ribbon is tied to the young soldier’s gun. In the same way, all references to a future Victory in the material are detached from empirical backing, real or fake. In the entire material gathered from the clubs, there is not a single statement on whether the war is developing successfully – or indeed whether it is developing at all. Instead, one could frequently get the impression that an eventual victory is certain because it happened in 1945.

Symbolic saturation

It should be underscored how the various GPW-references rarely appear one at a time. Symbolic components, whose meaning may be flexible or unclear on their own, are clustered together to unambiguously tie them to the GPW and the war in Ukraine. When Yunarmiya squads brought soldier letters out to a local memorial, for instance, the letters had also been folded in the mentioned triangular shape, and both their insides and covers were full of visual GPW symbols as well as patriotic tropes.

Some cases of war time memes, graphics, or movie clips are incredibly rich in symbolic content – as if their creators are attempting to score as many points as possible within the short attention span of the viewer (consider ). In one movie clip, for instance, the scene constantly alternates between the present and the past. We see bombed houses, Ukrainian nationalists, soldiers of Nazi Germany, Babushka ZFootnote4 with a burning Z in the background, Russian soldiers shaking hands with civilians and cuddling cats, burning villages, and an icon of Jesus Christ. This mishmash is all flashing across the screen accompanied with the epic Soviet march Svyashchennaya Voyna (‘Holy War') from 1941. Towards the end, a crackling radio voice, probably Stalin’s, declares that ‘Victory will be ours'.

Figure 2. ‘[The] Russian soldier is once again liberating Europe from Fascism!!!'. Poster combining many aspects of war merging: enemy image, liberation, St. George Z (variant), historical and contemporary army symbols, imperial eagle, time stamp.

![Figure 2. ‘[The] Russian soldier is once again liberating Europe from Fascism!!!'. Poster combining many aspects of war merging: enemy image, liberation, St. George Z (variant), historical and contemporary army symbols, imperial eagle, time stamp.](/cms/asset/61ee0ab7-2c05-4e95-b864-f11e0798b000/prxx_a_2265135_f0002_oc.jpg)

In short, war merging may be abstract, but it is often less than subtle.

Explaining the GPW monomania

There are many reasons why the GPW has become the war of all wars in Russian political mythology, endlessly referred to in Russian patriotic discourse. The sheer scale and desperation of the war produced an enormous reservoir of memories. Some serve to prop up an extraordinary story of collective suffering, heroic acts and astonishing achievements, making them valuable assets for nation building purposes. At the same time, the war also contains large deposits of great horrors and shameful events, prompting official Russia to delimit their place in the popular consciousness. Together, this provides the perfect historical backdrop for a combined hyper-exploitation and securitization of the GPW as political myth (Bækken and Enstad Citation2020). The GPW is a mnemonic resource of great value, but also vulnerable and under sustained criticism from external others (Mälksoo Citation2015).

Moreover, the GPW provided Russia with an updated version of a national myth of exception that was already present before the war. In this way, the invasion and existential threat of 1941 came to confirm the Russian/Soviet view of itself and the world, and crowned the pre-existing story of Russian exceptionalism. In the terms of Wertsch (Citation2021, 135), the GPW is Russia’s ‘privileged event narrative' – at the same time a specific narrative and a realization of a more fundamental ‘narrative template'. Its mnemonical power is thus a derivate of two converging storylines, one more abstract than the other. War merging in the context of today’s warfare in Ukraine should therefore not be seen simply as the merging of two wars. Rather, we observe in real-time how yet another war is sucked into the memory grinder to become a part of an ‘eternal’ Russian story.

The differing storylines from the West have limited traction to change this narrative, so firmly linked to Russian exceptionalism. In a sense, the lacking Western acceptance of the narrative is already part of the story itself, and criticism may therefore be mistaken for proof. One illuminating study of how different national populations interpret the war documents how Russians are indeed outliers (Abel et al. Citation2019). Russians have a better knowledge of important historical events during the war than any other nationality examined. They also have a higher appreciation for their own country’s contribution to the Victory than the population of any other nation. More importantly, the gap between a nation’s self-evaluation and how its contribution is perceived appreciation by other national groups is greater in Russia than anywhere else. Finally, Russians also have the sample’s greatest degree of cohesion among themselves. The war’s privileged position in the collective memory, along with a lack of appreciation abroad, provides fertile ground for the development of national ressentiment and exceptionalism. Wertsch (Citation2021, 135) suggests that mnemonic communities tend to see privileged event narratives as ‘an obvious lens for viewing the past, present and future'. Abstract references to the GPW would hardly work as effectively without this firmly internalized metanarrative.

The historical references in the reviewed material overwhelmingly lack substantiation. Seldom or nowhere is any reason given to explain why the references to GPW would supposedly be relevant or sensible in a given context. The few videoclips of Russian soldiers greeting civilians or cuddling cats provide rare examples of how Russian troops are depicted as actually doing something good beyond abstracted glorious fights against ancient enemies or shooting at unidentified (in the movies) targets. For the most part, instead of explicitly telling fake or real stories from the front and presenting them as new manifestations of eternal Russian glory, suffering, or bravery, the actors are usually satisfied with drawing soldiers from GPW side by side with soldiers of today – providing nothing in the sense of documentation. By means of famous Soviet war hymns and crosscut videoclips from wars past and present, wars are merged without a single sentence being uttered or factual proposition made.

Two sides of dependency

In explaining why war merging is exceedingly abstract and lacking substantiation, two interpretations seem close at hand. First, abstraction may be a sign of weakness – a feature of a narrative that lacks grounding in reality. In this line of argument, Russia has nothing better to say. Its war is based on a failed gamble, and its mouthpieces resort to the GPW in a desperate search for legitimation for what cannot be legitimized.

A key aspect of the above perspective is what we could call lack of narrative fit. Carleton has formulated the following narrative core that binds the GPW to already dominant Russian myths: ‘A seemingly invincible demon invades from the west; again Russia is pushed against the wall; again its lands and cities burn; again the fate of the nation is decided in a titanic struggle on its own soil; again the war ends when Russians, at the head of a coalition of liberators, enter the enemy’s capital; again civilization is saved'. This metanarrative is hardly easy to employ on the war in Ukraine, even if seen from Russian perspective. If one would accept the premise that the war could be understood as a ‘pre-emptive strike', for instance, the template has no slot for such wars. Likewise, the enemy was seen as very much beatable, and no Russian cities burned as of spring 2022. Russia claimed to liberate a brother-nation somehow held hostage by a fascist government, yet all evidence indicates high popular support for Ukrainian authorities. Moreover, Russia found itself more isolated than ever, even if propaganda attempted to frame the self-proclaimed republics (DPR and LPR) and itself as ‘allied forces' (soyuznye sily). In fact, it was unclear to most Russians who was the real enemy and what exactly was the purpose of the war (Kashperska Citation2021). In terms of Carleton’s template, they cannot imagine what capital one should end up in this time.

The other line of interpretation would suggest that the abstraction is normal and useful. To be sure, collective memories have never been a predominantly intellectual affair. They do not represent our best approximation of a real past, but rather our emotions and identity. By its very definition, Russian official patriotism is an emotional, and not intellectual, commitment to one’s Fatherland. Rather than granting the youth a reason to love their country, such as social benefits or empowerment in shaping the policies, patriotic education predominantly aims to instil feelings and a sense of duty (Bækken Citation2019). One of Wertsch’s (Citation2021) central points is that when a narrative template is sufficiently entrenched, it can prove incredibly resilient and powerful. Carleton’s (Citation2017) analysis of Russian narratives of war throughout history led also him to a similar conclusion: No matter how harsh realities Russia has faced, Russian memory culture has retrospectively reworked them to fit the same storyline. While this sameness is arguably a matter of degree, Carleton documents how Russian historical-patriotic discourse has managed to ‘undo defeat' and find heroism where others see tragedy and failure.

Carleton analysis is founded on such sources as political speeches, history books, movies, and literary novels – all sources rich in content and elaborated narratives. In the fleeting everyday messaging of MPCs however, it seems less is more. It may appear that the leaders want the club members to notice the link to the past, but hardly to reflect upon it. Concretization may entail a challenge, because it can reveal falsehoods and/or differences which may undermine the usefulness of the link (Wertsch Citation2021, 113).Footnote5 A simple use of contextualization, war symbols and enemy images may therefore be safer than historical analogies. Their ‘falseness' is harder to pinpoint as they imply no factual claims. When historical analogies are too far-fetched, this form of history politics may alleviate a lack of narrative fit – perhaps even more so in case of fleeting messaging intended for instantaneous consumption.

Narratives templates are so vital to our mental functioning that they can be said to serve as ‘co-authors’ in our reflections upon the past (Wertsch Citation2021, 113). They ‘operate as underlying codes rather than explicit surface form’ (ibid., 85), which makes them particularly hard to discern and critically assess for their bearers. Rather than seeing them as templates, holders will claim (and believe) that they are simply reporting ‘what really happened' (Wertsch Citation2008, 144). These cognitive arrangements are fundamental to our biology, but the templates themselves are learned: They ‘emerge out of the repeated use of a standard set of specific narratives in history instruction, the popular media and so forth' (Wertsch cited in Philpott Citation2014, 316).

Constant exposure to certain (specific) narratives through childhood will not only provide a basis for arranging the told stories in accordance with a given template. It can also help develop cognitive tools to (mis)interpret future events. This forces us to take ‘deep’ disagreements of popular history very seriously – the templates are resistant to change, and not easily dispelled by their exposure to facts. In one conception, it is exactly the subscription to common narrative templates that defines mnemonic communities (Wertsch Citation2021, 76). Granted, collective memories are not straightforward, but established and remembered in a complex web of interlaying and not always coherent templates (Philpott Citation2014). Yet, some of these are dominating. In Russia, the scale and frequency of reproducing the GPW narrative of heroic defence against western (fascist) nations makes it one of unique importance. The concept of war merging describes one way in which pre-established templates are employed not only to make sense of events, but indeed to establish a frame for how millions of Russian minors will remember the ongoing war in the future. By means of war merging, Russian children are taught how to connect the dots in a way that the state approves.

Finally, we should note that ambitions do not equal outcomes. In order for the population to be successfully rallied though war merging, it would require of the politicized and arguably overused phrases and symbols an incredible emotional power. While it seems that the MPCs are indeed putting their trust in these symbols, we should not make the presumption of a real effect too easily – not even for MPC members. The limited ability of the state to impose its vision of patriotism on the younger population is a known concern, discussed by many researchers (e.g. Daucé Citation2015; Goode Citation2016; Bækken Citation2021; Krawtazek and Frieß Citation2022). Some of them claim that the historical perspectives do resonate with the younger audience, but that this fails to translate into popular support. These researchers often point to the general scepticism of political exploitation of the war: ‘Young people criticized the fact that those in power simply want to prove something without associating a nuanced historical meaning with the events' (Krawtazek and Frieß Citation2022, 11). The focus on war merging today will put these issues even more to the test.

Conclusions

This article has examined the way military patriotic clubs in Russia reacted to their homeland’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. After a period of initial silence, they gradually found new forms to express their supportive political stance without departing from their everyday modus operandi – and without diverging too much from each other. The most striking aspect of their reaction was the phenomenon I have dubbed 'war merging' and defined as a tool of manipulation that blurs the boundaries between contemporary wars and prevailing political myths about wars of the past. The phenomenon manifested on several arenas and in several practices, as well as in content circulated by MPCs on their social media profiles.

The instrumentalization of the political myth of the GPW to describe Russia’s current war in Ukraine is simultaneously a counter-intuitive and a natural choice. Counter-intuitive – because of the exceedingly poor narrative fit between the unfolding war and the established political myth of the GPW. But also natural – because of the well documented hyper-exploitation of history in contemporary Russia, and the unique position of GPW as a mnemonic resource here. As Russia’s ‘privileged event narrative', the GPW has a very strong emotional appeal – even if perhaps overused. Its deep roots in Russian society and its associations to Russian exceptionalism also makes it particularly resistant to external criticism.

As the war changes, and will continue to change, many aspects of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world, it will also shake up our apprehension of historical wars – with yet unforeseen consequences. We may be in a period of strong mnemonical drift with ‘conditions that make broader changes in the dominant frameworks of collective memory possible’ (Verovšek Citation2016, 538). As the last WW2 veterans are about to die of old age, the largest war in human history is passing from living memory only to be remembered indirectly. In this context, efforts by the state to shape and control collective memories will only become more powerful. At the very same moment, Europe is witnessing a new war that will change and update our mental and political conceptions of how inter-state wars are fought.

Entrenched political myths and narrative templates are resistant to change. What may still shake them, however, are ‘social revolutions' or ‘crushing military defeat’ (Smith Citation2003). In some scenarios, the efforts to connect the two wars may therefore have an adverse effect on the patriotic myth – tainting its sacred status with the everyday horrors and incompetence of today. The war merger is in this sense a gamble: In its efforts to legitimize today’s warfare, the Kremlin may in fact undermine the heroic memories that it has so solemnly sworn to protect.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the NORMEMO project group for valuable comments to previous versions of this draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Kolstø (Citation2016) links the symbol to an Order of the Guard (gvardeyskiy orden) of 1941, while Yana Prymachenko holds the Order of Glory (orden Slavy) from 1943 to be its key Soviet predecessor (in Danko Citation2021).

2 As of 2022, the St.George ribbon is banned in the Baltic countries and Moldova, as well as in Ukraine. Even Belarus quit using the ribbon on official occasions from 2015.

3 Swastikas are rarely seen in the material, presumably at least in part because their use is disallowed by Russian law – also if used in educational context.

4 Babushka Z or Babushka of Victory became a popular meme in Russian society in 2022, based on a short movie clip where an elderly woman greets Ukrainian soldiers with a large Soviet flag in her hands, and then refuses to take their food when she realizes they are not Russian. A rare golden nugget for Russian propaganda, the movie clip was quickly picked up by everything from Russian TV to online memes and patriotic street art. In May 2022, the Russian occupation regime of Mariupol had a statue erected of her.

5 Brandenberger and Platt (Citation2006, 166−7) make a similar argument in their analysis of Soviet politics of memory during WW2. While Stalin ‘encouraged the allegorical linking of the present with the [tsarist] past' he ‘did not tolerate more explicit associations'. The two scholars explain this policy in both positive and negative terms; relating it to the emotional power in these abstractions, but also to the potentially harmful ambiguities and contradictions that would follow concretization.

References

- Abel, M., S. Umanath, B. Fairfield, et al. 2019. “Collective Memories Across 11 Nations for World War II: Similarities and Differences Regarding the Most Important Events.” Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 8 (2): 178–188. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0101836.

- Bar-Tal, D., and E. Staub. 1997. “Introduction: Patriotism: Its Scope and Meaning.” In Patriotism in the Lives of Individuals and Nations, edited by D. Bar-Tal, and E. Staub. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

- Bækken, H. 2019. “The Return to Patriotic Education in Post-Soviet Russia. How, When, and Why the Russian Military Engaged in Civilian Nation Building.” Journal of Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society 5 (1): 123–158.

- Bækken, H. 2021. “Patriotic Disunity: Limits to Popular Support for Militaristic Policy in Russia.” Post-Soviet Affairs 37 (3): 261–275.

- Bækken, H. 2022. “Guns and Glory. A Dualistic Perspective on Resurgent Militarism in Russia.” In A Restless Embrace of the Past, edited by S. Šrāders, and G. S. Terry, 26–37. Tartu: University of Tartu Press. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/53132

- Bækken, H., and J. Enstad. 2020. “Identity Under Siege: Selective Securitization of History in Putin’s Russia.” The Slavonic and East European Review 98 (2): 321–344.

- Brandenberger, D., and K. M. F. Platt. 2006. Epic Revisionism: Russian History and Literature as Stalinist Propaganda. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Brunstedt, J. 2021. The Soviet Myth of World War II. Patriotic Memory and the Russian Question in the USSR. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carleton, G. 2017. Russia: The Story of War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Danko, V. 2021. “Whoever Disagrees with Russia is a Nazi and Fascist. Why Does the Kremlin Need the St. George Ribbon?” Stopfake.org, November 17. Accessed 17 August 2022. https://www.stopfake.org/en/whoever-disagrees-with-russia-is-a-nazi-and-fascist-why-does-the-kremlin-need-the-st-george-ribbon/.

- Daucé, F. 2015. “Patriotic Unity and Ethnic Diversity at Odds: The Example of Tatar Organisations in Moscow.” Europe-Asia Studies 67 (1): 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2014.988997.

- Domańska, M. 2022. “The Religion of Victory, the Cult of a Superpower. The Myth of the Great Patriotic War in the Contemporary Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation.” Institute of National Remembrance Review 2021/2022 (3): 77–125.

- Fedor, K., and L. Zhurzhenko. 2017. “Introduction: War and Memory in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus.” In War and Memory in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, edited by K. Fedor, and L. Zhurzhenko, 1–40. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Feindt, G., F. Krawatzek, D. Mehler, F. Pestel, R. Trimcev. 2014. “Entangled Memory. Toward a Third Wave in Memory Studies.” Source: History and Theory 53 (1): 24–44.

- Gaufman, E. 2015. “Memory, Media, and Securitization: Russian Media Framing of the Ukrainian Crisis.” Journal of Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society 1 (1): 141–174.

- Goode, P. B. 2016. “Love for the Motherland.” Russian Politics 1 (4): 418–449. https://doi.org/10.1163/2451-8921-00104005.

- Hauter, J. 2023. “Forensic Conflict Studies: Making Sense of War in the Social Media Age.” Media, War & Conflict 16 (2): 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/17506352211037325.

- Horbyk, R. 2015. “Little Patriotic War: Nationalist Narratives in the Russian Media Coverage of the Ukraine-Russia Crisis.” Asian Politics & Policy 7 (3): 505–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/aspp.12193.

- Kashperska, D. 2021. “Symbols of the Full-Scale Russian Federation Invasion of Ukraine: Public Relations Tools of Mythologization of the Military Aggression.” Political Science and Security Journal 3 (2): 3–10. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6801268.

- Kolstø, P. 2016. “Symbol of the War — But Which One? The St George Ribbon in Russian Nation-Building.” The Slavonic and East European Review 94 (4): 660–701.

- Koroleva, M. 2022. “‘Ordinary Nazism’ Bizarre Exhibition at Moscow’s Victory Museum Attempts to Draw Comparisons Between Nazi Germany and Modern-day Ukraine” Meduza, June 7. Accessed 8 November 2022. https://meduza.io/en/feature/2022/06/07/ordinary-nazism.

- Krawtazek, F., and N. Frieß. 2022. “Foundation for Russia. Memories of WW2 for Young Russians.” Nationalities Papers, https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2022.12.

- Kucherenko, O. 2011. “That’ll Teach’em to Love Their Motherland!: Russian Youth Revisit the Battles of World War II.” Contemporary Uses of the Second World War in Russia and the Former Soviet Republics 2011(12), https://doi.org/10.4000/pips.3866.

- Levite, A. E., and J. Shimshoni. 2018. “The Strategic Challenge of Society-Centric Warfare.” Survival. Global Politics and Strategy 60 (6): 91–118.

- Luxmore, M. 2019. ““Orange Plague”: World War II and the Symbolic Politics of Pro-State Mobilization in Putin’s Russia.” Nationalities Papers 47 (5): 822–839.

- Malinova, O. 2017. “Political Uses of the Great Patriotic War in Post-Soviet Russia from Yeltsin to Putin.” In War and Memory in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, edited by K. Fedor and L. Zhurzhenko, 43–70. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mälksoo, M. 2015. “‘Memory Must be Defended’: Beyond the Politics of Mnemonical Security.” Security Dialogue 46 (3): 221–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010614552549.

- McGlynn, J. 2020. “Historical Framing of the Ukraine Crisis Through the Great Patriotic War: Performativity, Cultural Consciousness and Shared Remembering.” Memory Studies 13 (6): 1058–1080.

- Pertsev, A. 2022. “Compassion, Tolerance, and Love for Others’ What the Kremlin’s Latest Propaganda Guides Tell pro-Government Media Outlets to say about the war”. Meduza, August 2. Accessed 17 October 2022. https://meduza.io/en/feature/2022/08/02/compassion-tolerance-and-love-for-others.

- Philpott, C. 2014. “Developing and Extending Wertsch's Idea of Narrative Templates.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 37 (3): 309–323.

- Portnov, A. 2017. “The Holocaust in the Public Discourse of Post-Soviet Ukraine.” In War and Memory in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, edited by K. Fedor, and L. Zhurzhenko, 347–370. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- President of Russia. 2022a. “Address by the President of the Russian Federation,” Kremlin.ru, February 24. Accessed 8 November 2022. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67843.

- President of Russia. 2022b. “Victory Parade on Red Square.” Kremlin.ru, May 9. Accessed 8 November 2022. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/68366.

- Rudling, P. A. 2012. “The Khatyn Massacre in Belorussia: A Histrorical Controversy Revisited.” Holocaust and Genocide Studies 26 (1): 29–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/hgs/dcs011.

- Sanina, A. 2017. Patriotic Education in Contemporary Russia. Sociological Studies in the Making of the Post-Soviet Citizen. Stuttgart: Ibidem Verlag.

- Smith, R. 2003. Stories of Peoplehood: The Politics and Morals of Political Membership. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Snyder, T. 2018. The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America. New York: Tim Duggan Books.

- Spiessens, A. 2019. “Deep Memory During the Crimea Crisis: References to the Great Patriotic War in Russian News Translations.” Target 31 (3): 397–419. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.18113.

- Talanova, D. 2022. “Kids with Guns. Russia’s Schoolchildren are Being Spoon-fed with ‘Patriotism’: They March Around Wearing Military Uniform, Hate Ukraine and NATO, and are Literally Taken on School Trips to Prisons. A Research by Novaya Gazeta. Europe.” Novaya Gazeta Europe, September 5. Accessed 29 September, 2022. https://novayagazeta.eu/articles/2022/09/05/kids-with-guns.

- Verovšek, P. J. 2016. “Collective Memory, Politics, and the Influence of the Past: The Politics of Memory as a Research Paradigm.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 4 (3): 529–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2016.1167094.

- Vinogradskaya, M. 2022. “Bitva za Khogvarts. S momenta nachala 'spetsoperatsii' nachalas' drugaya 'spetsoperatsiya', tsel' kotoroy - zavoevat' golovy rossiyskikh shkol'nikov.” Novaya Gazeta, March 15. Accessed 8 November 2022. https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2022/03/15/bitva-za-khogvarts.

- Wertsch, J. 2008. “Collective Memory and Narrative Templates.” Social Research: An International Quarterly 75 (1): 133–156.

- Wertsch, J. 2021. How Nations Remember. A Narrative Approach. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Zhurzhenko, T. 2015. Russia’s Never-Ending War Against ‘Fascism’. Memory Politics in the Russian Ukrainian Conflict”. Institute for Human Sciences (IWM). https://www.iwm.at/transit-online/russias-never-ending-war-against-fascism-memory-politics-in-the-russian. Accessed 4 November 2022.