?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This article presents a quantitative method for mapping semantic spaces and tracing political frames’ trajectories, that facilitate the analysis of the connections between changes in ideas and socio-political phenomena. We test our approach in Spain, where the Catalan conflict fostered a competition in terms of decontestation of meanings of key political concepts. Using unsupervised machine learning, we track the salience, level of semantic fragmentation and fluctuations in meanings of 216 frames in the two largest Spanish newspapers, El País and El Mundo, throughout 8 years. This is achieved via the extraction, vectorization, and comparison of over 70,000 words. We apply Latent Semantic Analysis, an innovative methodology for the alignment of semantic spaces, and new institutional theory. Our exploratory study suggests that the evolution of many nationalism-related frames resembles a punctuated equilibrium model, and that political events in Catalonia, acted as critical junctures, altering the meanings reflected in the Spanish press.

Introduction

The political language is a medium of shared understanding with the capacity to shape attitudes and choices (Ross, Skinner, and Tully Citation1989, 1–5). Ideologies are not static but built upon concepts that are essentially ‘contestable’ and subject to evolving interpretations. The ‘decontestation’ of these concepts consists of assigning ‘uncontested’ meanings, controlling equivocal and contingent meanings by holding them constant (Freeden Citation2013, 23). Decontestation has become a central element in political competition and a useful concept to understand political communication and ideologies (Laycock Citation2014).

Millions of citizens consume read, watch, and listen to news media as primary source of political information. The ‘frame’ – how topics are presented to the public – impacts the way in which the public processes and reacts to that information. Parties compete to impose dominant interpretations of concepts such as ‘democracy’, ‘equality’, ‘sovereignty’, ‘justice’ and ‘the people’ to secure support. Those challenging the status quo and proposing radical policy changes, like populist parties, fight to contest language, symbols, and dominant conceptual foundations (Laclau Citation2005, 18–19, 74, 83; Laycock Citation2005). For them, decontestation becomes an important part in the process of creation and re-creation of political identities (Freeden Citation1996, 78). By decontesting certain concepts, political actors can narrow down the number of available frames or alternative versions regarding specific issues on the public sphere and thus, tip decision-making debates in their favour (Ranciere Citation1995, 11). Newspapers play an important role in this political struggle to impose certain interpretations.

Shedding light on how micro-level processes such as the formation of perceptions, beliefs and attitudes are linked to macro-level political events has been a difficult endeavour social scientists have struggled with. The relationship between language frames and political attitudes has been hard to test in a rigorous manner given the difficulties capturing and comparing ideational contexts and, in particular, the evolution of meanings and shared understandings of socio-political contexts.

This article paves the way for a new approach to comparative policy and social change analysis. It presents a new tool to capture numerically and represent visually the ideational context so to enable us to trace frame trajectories in written communication or transcripts of verbal one. It also provides an empirical contribution by showing that the secessionist crisis in Catalonia shaped the interpretations of a myriad of political frames in Spain. This study does not offer a full story of the changes in the ideational context, but it reflects the diversity in meaning trajectories triggered by key events – such as independence referendums – and illustrates the utilization of this new methodology.

Quantitative media analysis usually focuses on the frequency of key words in a selected corpus of news. Nonetheless, a simple measure of frequency or density does not allow to understand semantic centrality and changes in meaning over time. To illustrate how this methodology works, we track the relative salience, level of semantic fragmentation, semantic contours, and fluctuations in meanings of a set of key terms with political relevance in the two largest broadsheet newspapers in Spain El País and El Mundo throughout 8 years (2012–2019). This approach serves us to identify meaning trajectories and unveil critical junctures and significant sense changes at the ideational level. Changes in meanings of certain terms, as reflected by the press, can be constituted by, and constitutive of, changes in the ideational context, and as such relevant to understand political and sociological processes. To capture and compare changes in meaning we introduce a set of new semantic indices thanks to an unsupervised procedure of Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) (Dumais Citation2004).

This article is structured as follows. Firstly, it presents the key arguments in the literature justifying the need to look closer into the evolution of political frames, and the suitability of new institutional theory as analytical framework. Secondly, it briefly outlines the case-study: the political conflict in Catalonia and how it was reflected in the Spanish press. Thirdly, it provides an overview on the methodology and indices introduced in this paper. Fourthly, we show interesting patterns in the trajectories of political frames that seem to fit new institutional accounts and concepts. Finally, we discuss some limitations and potential applications of our tools in different contexts.

Literature review

Why analyzing political frames in media

The press plays a key role in the political arena because it influences voters and the ruling elites. Media frames shape how issues are interpreted and therefore the reaction triggered in the audience. Charles Fillmore, the pioneer of the study of frame semantics defines ‘framing’ as ‘the appeal in perceiving, thinking, and communicating, to structured ways of interpreting experiences’ (Fillmore Citation1976, 20). Acknowledging the influence of Wittgenstein, Erdmann and Rosch, he argues that perceptions and conceptions are shaped by pre-existing memories of prototypes to which they can be associated (Fillmore Citation1976, 24–25). Frames are central to the communication and comprehension processes and can be construed as ‘schemata of interpretation’ (Goffman Citation1974, 21) or lexico-grammatical provisions for naming and describing categories and their interrelations (Fillmore Citation1977). Words and expressions are associated in people’s minds to frames that can activate specific schemata – i.e. conceptual frameworks or cognitive structures representing generic knowledge – .

Indeed, people can understand each other only if the linguistic repertoires they use activate similar schemata (Fillmore Citation1976; Citation1977). As Lakoff (Citation1988) posits, cognition has an important experiential component. Individuals do not interpret words or symbols in an ‘objective’ manner by a simple reference to an external ‘reality’. Meanings are attributed to (often polysemic) words by personal sensorial, emotional, and social experiences (Lakoff Citation1988). In a similar vein, Halliday (Citation1967; Citation1973) introduces the concept of ‘transitivity’, to explain the process through which language users convey different versions of reality in their discourse by encoding in their communications their own internal consciousness and external world experiences via choices of words and syntactic structures. Information is arranged in specific ways to convey specific ideological positioning and interpretations of events (Halliday and Matthiessen Citation2014, 217; Bartley and Hidalgo-Tenorio Citation2015).

The relevance of frames in communications is not restricted to the field of linguistics. Political scientists, sociologists, psychologists, and experts in media have also demonstrated that small changes on how the information is presented may have sometimes a strong impact on public opinion (Iyengar Citation1987; Nelson and Kinder Citation1996; Chong and Druckman Citation2007; Díez Medrano Citation2021). Entman (Citation2010, 391) argues that framing is ‘an omnipresent process in politics and policy analysis’, and that fundamentally entails the selection of some aspects or dimensions of an issue and the attribution of salience (Entman Citation1993, 52). From a political behavioralist angle framing is ‘the process by which a communication source constructs and defines a social or political issue for the audience’ (Nelson, Oxley and Clawson Citation1997, 221). People’s overall attitudes toward specific policy issues are the result of the evaluation of perceived positive and negative aspects (Coppock, Ekins, and Kirby Citation2018). However, individuals attribute different value or weight to different dimensions of the same policy issue. The selective emphasis or omission of certain information aspects can significantly impact individuals’ values and policy choices (Kahneman and Tversky Citation1984), induce changes in the accessibility of groups sentiments, and alter the importance attributed to certain group attitudes (Nelson and Kinder Citation1996, 1073).

Thus, ‘frames in communication’ can help activate specific ‘frames in thought’ and to steer an individual assessment in an intended direction (Chong and Druckman Citation2007, 105–106). For instance, a political independence demand framed as ‘right of self-determination’ (derecho de autodeterminación) would probably trigger more positive attitudes in an audience than if it is framed as ‘separatism’ or ‘secessionism’. Political frames can be stated directly or suggested indirectly through a variety of verbal and visual symbolic elements – e.g. slogans, logos, metaphors, euphemisms, analogies, etc. – . They help define problems, diagnose causes, make moral judgements, and suggest solutions (Entman Citation1993, 52). Politicians, partisan elites, and mass media engage in the production of frames to mobilize voters and gain their fondness.

All of them compete to shape the understanding of the causes of societal issues, of the pertinence of policy alternatives, and of the beneficiaries and victims of such problems and proposed solutions (Nelson and Kinder Citation1996, 1055–1057). Political actors conceive media as instruments in their power struggles. They are aware of the capacity of media to define and interpret issues and take advantage from the momentum generated by media information (Van Aelst and Walgrave Citation2016, 496–499). At the same time, media can not only shape voters’ attitudes and how electoral campaigns are conducted and interpreted (Patterson Citation1993), but also constitute a preferent source of information for the ruling elites. The press has the capacity to increase or decrease the relevance of certain topics for politicians and elicit certain responses and communicative frames from them (Kingdon Citation1984; Van Aelst and Walgrave Citation2016, 501–503).

In the context of an identarian conflict, like the one in Catalonia, frames acquire a particular salience. The fight for political hegemony implies a fight at the ideational level and specially a competition in terms of decontestation of meanings of certain key concepts regarding the ‘collective self’ and the ‘other’ (Ranciere Citation1995; Freeden Citation1996; Citation2013; Laclau Citation2005; Laycock Citation2005). Societies undergo periodically processes of hegemonic rearticulations of dominant discourses and interpretations of reality (Laclau and Mouffe Citation2001, xii). Nation building requires the alignment of a plurality of citizens around shared understandings of what constitutes their demos, polity, common interests, and the boundaries of their society (Anderson Citation1983; Gellner Citation1983; Sutherland Citation2005).

In this sense, language is used to establish internal frontiers which in turn help defining concepts such ‘the people’, ‘class’ or ‘nation’ and fix political identities around them (Laclau and Mouffe Citation2001, 7–46; Laclau Citation2005, 18–19, 74, 83). Through a ‘logic of equivalence’ and a ‘logic of difference’ political frames play homogenizing/inclusion and heterogenizing/exclusion functions. They can convey a sense of mutual recognition, unity, and common purpose precisely via the discursive construction of equivalent demands and grievances against a ‘other’ (Laclau Citation2005, 18–19; Laclau and Mouffe Citation2001, 176–193; Olivas Osuna Citation2022). As such, conflicts revolving around identity politics, like the secessionist push in Catalonia, are not circumscribed to the institutional domain. The struggle over regulation, budgets, and degrees of political autonomy is mirrored on the ideational realm. Existing hegemonic interpretations become targets of political actors who seek to impose new frames and alter meaning trajectories.

Once we have established the relevance of the study of political frames in media, it is important to select a theoretical framework to analyze them. In the next section we argue that new institutional theory helps to provide parsimonious causal accounts of change and trajectories in semantic spaces, including political frames in media.

New institutionalism and the study of trajectories in political frames

The ideational domain became increasingly important in social research once rational choice theories and methodological individualism proved insufficient to capture many of the political and institutional changes observed in society (Goldstein and Keohane Citation1993; Blyth Citation1997; Hay Citation2004). Structural-functionalist and utility maximization accounts had downplayed the role of ideas in shaping policy choices in political science during the 1960s and 1970s (Hall and Taylor Citation1996, 936). Rationality is bounded (Simon Citation2000; Weyland Citation2008) and individuals are embedded in social structures or networks of interpersonal relations that contribute to shape their perceptions and behaviours (Granovetter Citation1985). Therefore, actors are not only strategic, but also socialized, and their actions are not a direct reflection of their own material interests but are mediated by the perceptions they have of their interests and of what constitutes socially acceptable behaviour in a specific context (Blyth Citation1997, 230; Checkel Citation1998, 326; Olivas Osuna Citation2014, 21–22).

‘New institutionalism’ emerged as a scholarly effort to break the analytical divide between interest, institutions and ideas and provide new explanations to political phenomena (March and Olsen Citation1989; Hall and Taylor Citation1996). Shared interpretations and normative principles influence decisions by specifying the nature of the problem, policy goals, and the more socially appropriate instruments or avenues to achieve them (Hall and Taylor Citation1996). New Institutionalist literature provides an explanatory framework that helps understand changes in the material world – e.g. organizations, budgets, political representatives, written laws, etc. – and in the ideational plane – like those observed in meanings and political frames – .

One of the central arguments in this literature refers to the discontinuity in change, and the long-term legacies of major historical events. Changes in the ideational plane are not always gradual but often abrupt and asymmetric and can leave longstanding legacies (Kuhn Citation1962; Hay Citation2011). Political and social developments across time alternate periods of stasis with others of radical change, following what has been termed in the literature as a ‘punctuated equilibrium’ model (Krasner Citation1984, 242–242; Baumgartner and Jones Citation2010, 9–14). A ‘critical juncture’ is a period of significant change that produces distinct legacies or paths (Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967, 37; Collier and Collier Citation1991, 29). Another key concept in this literature is that of ‘path dependency’, i.e. the idea that historical events trigger changes and activate self-reinforcing mechanisms and inertias that contribute to lock a system into specific trajectory that persist in the absence of the original event (e.g. David Citation1985; Pierson Citation2000). This notion was inspired by Stinchcombe’s ‘historical causation’, that refers to the process by which ‘the effect created by causes at some previous period becomes a cause of that same effect’ (Stinchcombe Citation1968, 103). ‘Historical causes’ provide, therefore, an explanation for trajectories in social and political systems in the absence of the ongoing impact of exogenous mechanisms or ‘constant causes’ (Stinchcombe Citation1968, 103; Thelen Citation2003, 214–217).

The indicators we build and test in this paper aim to capture trajectories in the meaning of hundreds of political frames. We are tracking frames used in the context of Catalan nationalism and assessing whether key events, such as the organization of the 2014 and 2019 independence referendums, impacted their meanings, and if neo-institutional concepts can be applicable to evolution observed in the semantic spaces we analyze.

The Catalan political crisis: a struggle at the framing level

The case of the Catalan sovereigntist challenge has been chosen to demonstrate the usefulness of our methodology given that it entails a strong ideational dimension. Both camps, ‘separatists’ and ‘unionists’, have attempted to impose their framing of the crisis. The ambitious nation-building programme set into motion by the former President of Catalonia Jordi Pujol in the late 1980s captures the efforts to achieve a new hegemonic collective interpretation that portrayed Catalan society, its past and its culture, as very different from the rest of Spain.

Although this programme did not make explicit references to independence, it set goals such as ‘making Catalan identity hegemonic’ and deepening the ‘Catalan differential factor’ (Pla de nacionalització 1990, 8). It sought the ‘Catalanization’ of education, sports, and entertainment programmes; the replacement of Spanish by Catalan as language in education, publicly funded media and formal communications; the creation of new universities with a ‘Catalan perspective’ and a Catalan news agency with a ‘nationalist spirit’; and the promotion of Catalan specific cultural content (Pla de nacionalització 1990).

In the following two decades, the Catalan government, Generalitat, actively implemented this nation-building initiative that sought to shape the ideational and interpretative context in which Catalans lived. The process of decentralization and transfer of powers to the Catalan authorities facilitated nation-building policies and the (re)construction of an increasingly distinct Catalan identity. Yet, support for independence remained below 20% until 2009. The Great Recession created a window of opportunity for pro-independence politicians to exploit grievances. Welfare chauvinism communication campaigns by nationalist parties – with slogans such as, ‘Spain steals from us’ and ‘the subsidized Spain is living from the productive Catalonia’ – became part of the ‘othering’ strategy that tried to emotionally detach Catalans from the rest of Spaniards (Moreno-Almendral Citation2018, 133; Newth Citation2021, 12–14). In 2010, the amendments introduced by the Spanish Constitutional Court to the new Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia, were also used by nationalist leaders to fuel public disaffection and mobilize Catalans (Domènech et al. Citation2020, 335–336).

Nationalist politicians adopted a populist discourse and performative style around divisive issues which salience they amplified (Barrio, Barberà, and Rodríguez-Teruel Citation2018). During the celebration of the National Day of Catalonia, Diada, on 11 September 2012, hundreds of thousands marched requesting that Catalonia becomes a new independent state (Humlebæk and Hau Citation2020). This event marked the transformation of secessionism from minority to mass movement (García Citation2021). Catalan press largely portrayed this as a unitary movement and incorporated nationalist political frames (Castelló and Capdevila Citation2015). Support for independence had jumped to 44.3% by November 2012.

Meanwhile, the conservative Catalan government, led by Artur Mas, was losing popularity due to several corruption scandals and the economic hardships derived from austerity policies (Rico and Liñeira Citation2014). To recover support from those who were veering toward the secessionist nationalist party Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC), Mas promised the celebration of a referendum of self-determination and steered his traditionally moderate party into more maximalist sovereigntist positions.

Despite successive warnings from the Constitutional Court, nationalist leaders launched two independence consultations – on 9 November 2014 and 1 October 2017 – and a unilateral declaration of independence on 27 October 2017. Several of them fled the country and others were tried and sentenced in 2019. A wave of mobilizations and protests actions, orchestrated by the pro-independence platform ‘Democratic Tsunami’ (Tsunami Democràtic), followed the sentences.

As a test of the effectiveness of the methodology we introduce in this article to track and compare meaning trajectories, we analyze Spanish mainstream, at a semantic level, during the conflict in Catalonia (2012-2019). Specifically, we investigate the evolution of hundreds of political frames frequently used by the pro-independence movement or when referring to it.

Methodology

Social science scholars have developed a variety of methodological approaches to study text and its relationship with politics and policy, such as content analysis, corpus-assisted discourse analysis and rhetoric analysis (Hidalgo-Tenorio, Benítez-Castro, and Cesare Citation2019) The advent of the internet and the popularization of high-level programing languages have opened new opportunities in terms of text analysis. Obtaining text, transforming text to data, quantitatively analyzing large amounts of data while ensuring robustness are now much easier processes for researchers (Wilkerson and Casas Citation2017). We use Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) which is a multistep process to grasp a corpus’ structure and conceptually similar to traditionally Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which is based in the transformation of the text corpus in a series of eigenvectors. This is widespread technique in social sciences to study synonymy, polysemy, and word association in text corpuses, and it does not require access to supercomputers (Valdez, Pickett, and Goodson Citation2018).

LSA has been widely studied in the field of concept representation and has been thoroughly tested overtime in a variety of empirical and methodological papers (Balbi and Esposito Citation1998; Jorge-Botana, Ricardo Olmos, and Luzón Citation2020; Martínez-Mingo et al. Citation2023). LSA key advantage vis-à-vis alternative methods is that it provides an orthonormal basis which is well-suited to apply space alignment, a procedure explained later in this article, necessary to make corpuses comparable (Jorge-Botana, Olmos, and Sanjosé Citation2017). Word2Vec is a factorization procedure (Mikolov et al. Citation2013; Levy and Goldberg Citation2014) considered as an alternative to LSA, however, orthogonality is not guaranteed in the embedding matrix (Jorge-Botana, Olmos, and Luzón Citation2019).Footnote1 The same limitation ruled out in this study the utilization of GloVe (Pennington, Socher, and Manning Citation2014) and new deep learning language models such as Recurrent Neural Network with Long Short-Term Memory (RNN-LSTM) and Transformers. However, RNN-LSTM and Transformers, provide a contextualized representation of words, that could be useful in further similar research to develop new measures and metrics in similar studies (Ethayarajh Citation2019; Goldstein et al. Citation2022).

Capturing semantic spaces

Using a Python coded algorithm, we scrape the libraries of two of the main newspapers published in Madrid: El Mundo and El País. We generate 15 corpora with the entirety of the text published during a year in each news outlet (the corpora are provided in the online appendix). Due to data availability, we include the 2012–2019 period in El Mundo and only from 2013 to 2019 in El País. All these corpora were processed independently with an LSA procedure.Footnote2 Frames were considered if they appeared in at least four different paragraphs during that year and included a word-paragraph matrix. Entropy smoothing and SVD (Furnas et al. Citation1988) are performed over that matrix and the 300 dimensions with highest singular values are preserved. Accordingly, each frameFootnote3 (meeting the abovementioned threshold) is represented by a vector with 300 latent dimensions, as has become the standard in LSA (Cai et al. Citation2018) in each newspaper/year semantic space (15 in total). To preserve the frequency sensibility, word/frame-vectors were not normalized.

Alignment strategy

Frame-vectors emerging from the LSA in each semantic space are expressed in coordinates relative to different bases. To make them comparable, we align the semantic spaces by expressing them on coordinates relative to 2019 in each newspaper. For this purpose, we use a Procrustes rotation technique (Jorge-Botana, Olmos, and Luzón Citation2018; Balbi and Esposito Citation1998) that entails adding to each corpus common 1000 ‘pivot paragraphs’ extracted from Wikipedia (in Spanish). Those paragraphs are assumed to be meaning constant. The choice of pivot texts to align semantic spaces is based on two underpinning criteria. First, the need to represent a structured yet, in theory, ideologically neutral source of language. Second, the need to use as reference no context specific paragraphs, so that meanings would not evolve throughout the period analyzed. Unlike texts in news outlets that are prone to adapt to temporal contexts of meaning and to convey certain ideological leaning, Wikipedia’s entries tend to be technical, scrutinized by editors to ensure political neutrality, and atemporal in spirit. Thirty words, representing six meta-topics – economics, politics, sports, international, war and events, and culture/leisure – were chosen as search items in Wikipedia to identify and collect the 1,000 pivot paragraphs, with a minimal length of 25 words.

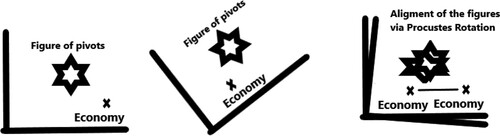

Following, the Procrustes approach, the 1,000 pivot paragraph vectors are rotated in each of the semantic spaces created with our LSA, until they overlap the 1,000 pivot paragraph vectors in the 2019 semantic space (in the corresponding newspaper). The distances of the coordinates of pivot paragraph vectors can be seen as a constellation of coordinates (see stars in ). We maximize the degree of overlapping by, minimizing the average distances between the coordinates of the vectors of the pivot paragraph we are rotating and those of the 2019 pivot paragraph. The degree of rotation calculated is then applied to the rest of the semantic spaceFootnote4 so that all spaces for each of the newspapers are expressed in terms of coordinates relative to the same basis, that of 2019. With this alignment process, we create a unique semantic space for each newspaper in which each frame is represented several times – one per year – . For example, the frame ‘economy’ in El Mundo is represented with eight different vectors, one for each year: .Footnote5

Indices based on importance and meaning change

Salience of a word in each year-newspaper. When we have all the spaces aligned with the fixed one (the 2019 space), the vector of each frame in each space has a vector length (a norm) that indicates the semantic salience of that frame relative to that space. The magnitude or length of a LSA vector indicates the importance degree in the space (Landauer, Foltz, and Laham Citation1998, 269; Steinberger and Jezek Citation2004). The importance of the frame ‘economy’ in 2012 is calculated by the norm, that is, the square root of the sum of each component of the vector squared.

Vector length is space-dependent, that is, it is directly related with the amount of text retrieved for each year. To make this measure comparable we apply a range normalization.

Semantic diversity of a word in each year. The Semantic Diversity (SemD) index to estimate the number of thematic units that a frame appears in. SemD helps overcome the limitations to previous approaches to the analysis of semantic ambiguity as provides an objective way of quantifying context-dependent variation in meanings. It gives room to subtle differences in meaning without imposing a limited number of discrete senses (Hoffman, Rogers, and Lambon Ralph Citation2011; Citation2013). A thematic unit is an abstraction that does not correspond with a set of specific documents or paragraphs, i.e. several paragraphs could belong to the same thematic unit. A high semantic diversity denotes that a frame is associated to a variety of thematic contexts. A low semantic diversity means that the frame is focalized in one or few thematic contexts. The formula is as follows:

where:

= Word of index I (the word we want to calculate the SemD)

m = number of paragraphs where word appears

= paragraphs of index j and k

= vector that represents paragraphs j and k

Overtime some frames expand their meanings while others focalize theirs. To make this measure more understandable, we transform semantic diversity into a focalization measure and rank each frame according to it.

We allocate frames into deciles according to the relative focalization of their meaning vis-à-vis the entire set of frames in the same semantic space. Thus 1 indicates that the frame is part of the 10% of frames with the lowest focalization and 10, that it would be part of the 10% of frames with the highest focalization score.

Continuity in meaning in consecutive years. A frame is represented with eight different vectors, one for each year (seven in El País). We can calculate vector similarities (cosine) to see to what extent the meaning of a frame has changed in consecutive years.

The higher the values in the sequence of similarities in consecutive years, the lower the degree of meaning volatility. A very low score suggests an important disparity in the sense of the word between two years.

Resonance of meaning of previous years in the last one. This index is like the continuity index, but the similarities are measured between a given year and then last one analyzed (in this case 2019). We also calculate a mean of resonance of each word. The sequence collected is then as follows:

Fragmentation over time. The fragmentation refers to the association of a frame to different semantic factors across the period analyzed. We perform a factor analysis with oblimin rotation and add the number of factors that remain statistically significant with p < 0.05 (Chi-Square) to construct our fragmentation index. Basically, this fragmentation index indicates the number of semantic factors that can be extracted for all the vectors representing a word in several years. Note that this measure does not consider the sequential nature of time spaces, and only measures the overall fragmentation.

Our open access dataset provides tables for all these indices mentioned above (salience, fragmentation, resonance and continuity). In the case of El Mundo, we supply indices for 56,695 words. In the case of El País, we supply indices for 74,795 words.Footnote6

Association with other frames. We identify the frames, within each semantic space more closely associated with a key frame of interest in the Catalan conflict (via cosines). We represent them in word clouds and assess the differences encountered across time as indication of changes and stability in the meaning of these key terms. Word clouds serve to visualize semantic neighbours. The Wordcloud R package is used here to facilitate the qualitative analysis. Different size of text and colours reflect the semantic distance between each word or expression and the frame of reference. We only use three frames of reference in this case, to illustrate the usefulness of this index (‘political prisoners’, ‘Catalanism’ and ‘third way’), but the analyses could be conducted in any other one included in the database.

Choice of frames

Although this study is exploratory and methodological in nature, we aim to provide some relevant empirical findings about the impact of the Catalan conflict on the Spanish ideational context. We combine deductive and inductive approaches in the selection of news frames (De Vreese Citation2005, 53–54) that would be relevant to understand this specific political phenomenon. First, we examine the literature on the Catalan conflict, nationalism, and Spanish politics, as well as many news articles related to Catalan politics to identify a first set of over 100 relevant concepts that can be considered a combination of issue-specific and generic frames (De Vreese, Peter, and Semetko Citation2001, 108–109). We include keywords and short expressions, mostly in Spanish, but also some Catalan neologisms commonly used in Spanish press, names of parties and political figures.

We then extract lists of terms semantically associated to these initial frames in each of the semantic spaces. We eliminate duplicates and those that are considered not directly linked to politics or the political events we want to study. This allows us to create a dictionary of 556 frames, that range from 1 to 7 words. This list incorporate slightly different iteration of similar concepts related to the Catalan political conflict, for instance to analyze the concept of ‘statute of autonomy’, we studied ‘estatuto’, ‘estatut’, ‘estatuto de autonomía’, ‘estatuto de Cataluña’, ‘estatut de Cataluña’, ‘estatuto catalán’, and ‘estatuto de autonomía de Cataluña’.Footnote7

We do not assume that similar, but not equal frames (including plurals) will share the same meaning path, hence the need to study them separately. Moreover, the semantic properties of words are not additive; therefore, we cannot assume that the indices calculated for the vectors of words contained in a frame can be added to produce the indices of the vector of a specific combination of such words. For example, the sum of vector for ‘Constitutional’ and that for ‘Court’ would unlikely display the same semantic properties of the vector for ‘Constitutional Court’.

We generate salience, focalization, continuity, and resonance indices for each of these 556 frames. Based on an assessment of these results we, then, eliminate those frames whose low frequency hindered some of the indices and shortlist 216 frames for our comparative quantitative and qualitative investigation. This list is not comprehensive but provides sufficient breadth as basis for meaningful empirical analyses and illustration of the variety of potential types of meaning trajectories that can be encountered.

Results

The findings presented in this section show the usefulness of each of the indices we introduce in our methodology and outline some relevant empirical observations regarding the evolution of frames’ meanings associated in our case study that may be applicable in other contexts. The choice of frames in this section seeks primarily to illustrate the impact of a political phenomenon – secessionist conflict in Catalonia – , in the semantic realm – the meanings of political frames in Spanish mainstream press published in Madrid – . Rather than providing a representative or holistic picture, the goal of this section is to show that critical junctures in society may trigger changes and diverse semantic paths in the frames used to interpret politics.

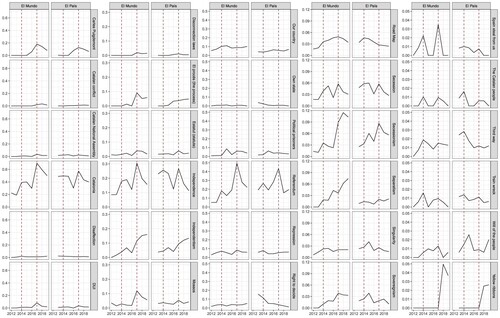

Salience

Unsurprisingly, as shows, the salience of many frames linked to Catalan politics and political self-determination increase in 2013 and 2014. This coincides with the ideological shift in the largest Catalan nationalist party Convergència i Unió (CiU), from autonomist to secessionist, and the preparation for the Scottish independence referendum as well as for the first Catalan one. Frames used by nationalist parties in their discourses – such as ‘sovereignism’ (soberanismo), ‘singularity’ (singularidad), ‘disaffection’ (desafección), ‘right-to decide’ (derecho a decidir), ‘road map’ (hoja de ruta), ‘Spain steal from us’ (España nos roba) and‘repression’ (represión) – gain significant centrality in both newspapers. Other expressions adopted by politicians and analysts to metaphorically describe the political conflict also gain salience, for instance ‘train wreck’ (choque de trenes) and ‘third way’ (tercera vía).

As nationalist parties in Catalonia intensified their commitment to achieve independence, several of the abovementioned terms lost salience and were replaced by new ones. Changes in the reporting of the crisis by Spanish mainstream newspapers seem to mirror the changes in the nationalist communication strategy. The merging of the main nationalist forces into the coalition Junts pel Sí (‘Together for the Yes’) whose goal was to achieve independence is reflected in the frames of El País and El Mundo. For example, frames such as ‘disconnection laws’ (leyes de desconexión) and ‘will of the people’ (voluntad popular) used by nationalists to refer and justify secession became common. Carles Puigdemont, who replaced Artur Mas, gained high levels of attention. It is also relevant that the press in Madrid embraces the utilization of Catalan neologisms, such as, ‘el procés’, ‘Mossos d’Esquadra’ (Catalan police) and ‘estatut’.

The impact of the second referendum and the unilateral declaration of independence in 2017 can be observed in salience peaks in frames such as ‘referendum’ (referendo), ‘independence’ (independencia), ‘unilateral declaration of independence’ (declaración unilateral de independencia), ‘Catalan National Assembly’ (Asamblea Nacional Catalana), and ‘secession’ (secesión). While some terms such as ‘secessionism’ (secesionismo), ‘independentism’ (independentistmo), and ‘separatism’ (separatismo) grew in both newspapers, others portray a distinct evolution. For instance, ‘referendum’ was a marginal frame until 2017 in El Mundo but increased its salience drastically henceforth. Meanwhile, in El País ‘sovereignism’ lost centrality. The ‘Catalan conflict’ (conflicto catalán) frame becomes salient two years earlier in El País than in El Mundo. ‘Own state’ (estado propio) and ‘the Catalan people’ (el pueblo de Cataluña) have significantly higher salience in El País, while expressions, such as ‘our country’ (nuestro país) or ‘separatism’, show more centrality in El Mundo. The utilization of the yellow ribbons as symbol for those demanding the release of the nationalist leaders imprisoned for organizing the illegal referendum is also noticeable; the term ‘yellow ribbons’ (lazos amarillos) becomes significant in both newspapers in 2018.

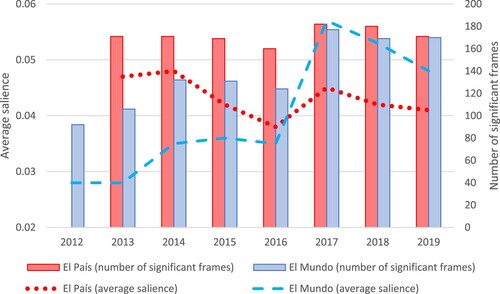

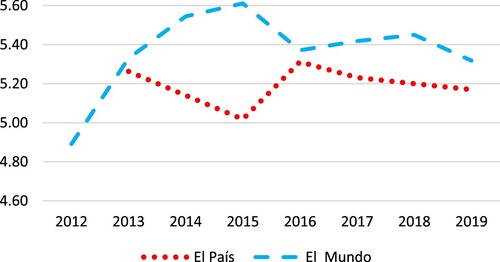

Finally, shows that the average salience of the set of 216 frames linked to the Catalan political conflict evolved differently in both newspapers. In El País we can observe a somewhat stable evolution, with high points in 2014 and 2017. In El Mundo we observe an extraordinary increase in the centrality of these expressions, that suggest a renewed concern about this issue. also shows the number of frames, out of the 216 highlighted in our analysis, that reach a minimum threshold of salience within each semantic space.

Semantic diversity

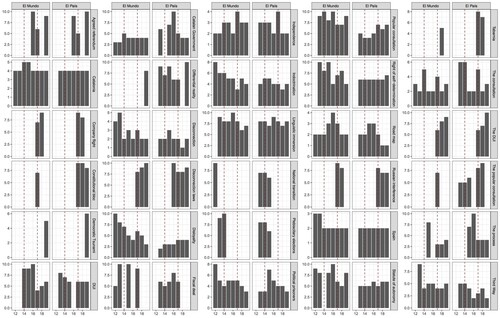

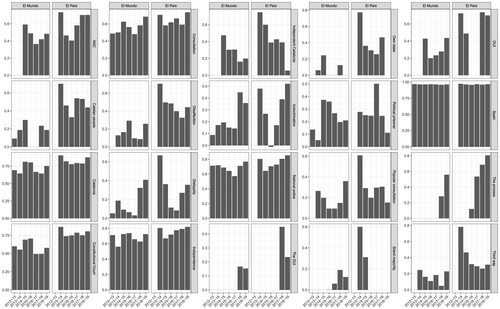

More interestingly, the events in Catalonia did not only serve to increase the salience of certain terms in the mainstream press edited in Madrid, which could be expected, but contributed to alter the meaning of many of them. Expressions that previously were utilized in a variety of topics and contexts and therefore enjoyed a significant semantic diversity, saw their meaning focalized into specific political senses. shows the meaning focalization decile for a set of analytically relevant frames for each year and newspaper, with 10 indicating maximum focalization of meaning and 1 maximum semantic diversity (0 values signify that the appearance of a specific frame was so marginal that did not reach the threshold for the semantic space of that year).

Several frames commonly employed by Catalan nationalists are associated across the period analyzed to a relatively low number of thematic units – their meanings in Spanish newspapers are usually associated to territorial politics. Many of them were commonly used before the period analyzed, such as ‘differential reality’ (hecho diferencial), and ‘linguistic immersion’ (inmersión lingüística). Other frames with a high degree of meaning focalization emerged during the crisis but their use quickly decreased later. For instance, frames such as ‘plebiscitary elections’ (elecciónes plebiscitarias) and ‘national transition’ (transición nacional) that were used by the nationalist camp until 2014, disappeared quickly afterwards (see also on salience) being replaced by others such as ‘agreed referendum’ (referendum pactado), ‘the unilateral declaration of independence’ (la DUI) and ‘Democratic Tsunami’. Similarly, highly focalized expressions, such as ‘constitutional bloc’ (bloque constitucionalista), ‘Tabarnia’,Footnote8 ‘Russian interference’ (injerencia rusa),Footnote9 and ‘company flight’ (fuga de empresas), that were used by those critical with the secessionist movement became visible in 2017.

The meaning of many relevant terms demonstrated a strong inertia and kept their semantic diversity overtime – such as, ‘independence’, ‘Catalonia’ (Cataluña) and ‘Spain’ (España) – other frames saw their semantic dispersion affected by political events. For instance, ‘the consultation’ and ‘the popular consultation’ (la consulta popular) see their meaning focalize on the years of the Catalan referendums, 2014 and 2017. ‘Road map’, an expression used before the 2017 referendum by the independence movement, loses focalization from 2017 onward. ‘Political prisoners’ (presos politicos) and ‘third way’ are also terms which level of semantic diversity experienced significant ups and downs. The frame ‘the process’ (el procés) was highly focalized during the buildup of the first referendum – when it was mainly used by the nationalist leaders – . However, from 2017, onward it became much more semantically diverse (and salient) as those critical with the secessionist process also adopted it.

As with salience, we observe that changes in focalization are not always symmetric. For instance, ‘disconnection’ reduces its level of focalization after 2014 in El Mundo, reflecting the abovementioned introduction of the euphemism ‘disconnection laws’ by nationalist politicians. There are many terms that appear with a much more focalized meaning in El Mundo than in El País – for instance, ‘indoctrination’ (adoctrinamiento), ‘popular consultation’ (consulta popular), ‘statute of autonomy’ (estatuto de autonomía), and ‘disloyalty’ – and vice versa – for example, ‘fiscal deal’ and ‘the government’ (el Govern). Therefore, certain expressions appear to be much more clearly associated to a specific context in one of the newspapers.

also shows that semantic diversity followed different paths in El Mundo and El País. In El Mundo, the level of relative focalization of key frames linked the Catalan conflict increased until 2015 and decreased afterwards. In El País these expressions and words kept in average a more stable trajectory. However, this variation may be impacted by the number of core frames associated to the Catalan political conflict that become statistically significant that in the case of El Mundo almost double (). These results suggest a new avenue of research to understand why some frames spread into many thematic contexts, while others remain circumscribed to few.

Table 1. Average focalization of frames (out of the 216 frames in the analysis)(N = number of frames reaching the minimum frequency threshold)

Continuity and resonance in meanings

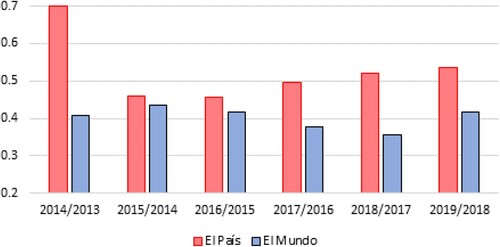

Continuity of sense and resonance in meaning are indices that capture inertias and volatility. The significant reduction in terms of meaning continuity between 2014 and 2015 in most terms analyzed in El País is one of the most striking results. This phenomenon may reflect not only the impact of the 2014 referendum and increasing concern about the Catalan conflict that intensified in 2013 and 2014, but also the arrival of a new director, Antonio Caño, and the reforms launched within the newspaper. Despite this initial significant decrease in vector similarities, overall semantic continuity was substantially higher in El País than in El Mundo across most terms related to the Catalan crisis ( and ). This suggests a higher degree of inertia in the former and a higher overall impact of the Catalan crisis on the latter.

Figure 7. Continuity in meaning in consecutive years for a set of frames associated to the Catalan political conflict.

shows a relatively high continuity in meaning in consecutive years in some general concepts – for instance, ‘Spain’, ‘Catalonia’, ‘independence’, and ‘Constitutional Court’ (Tribunal Constitucional). However, many other terms used in the framing of this crisis display a much lower vector similarity and/or a higher standard deviation which means changes in semantic contours across time. This indicates that some expressions employed by politicians in Catalonia, both opposing independence – such as ‘third way’, ‘indoctrination’, ‘disloyalty’ and ‘silent majority’ (mayoría silenciosa) – and promoting it – such as ‘political prisoner’, ‘popular consultation’ and ‘own state’ – ended up changing the meaning they evoked in the mainstream press in Madrid. While some frames have strong inertias and are less vulnerable to external shocks, others are more volatile and polysemic.

The resonance of meaning index helps understand how frames evolved and what periods left a stronger legacy and influenced the meaning of those same frames in the last period (semantic space) analyzed. As expected, some frames show an important degree of inertia in the semantic sphere (). Some expressions such as ‘Spain’, ‘Cataluña’, ‘National Police’ (Policía Nacional) and ‘consultation’ displayed high average resonance and low standard deviations, signaling that frames’ meanings in 2019 remained largely like those in previous years. The resonance of other frames, such as ‘ANC’Footnote10, ‘the process’, and ‘unilateral declaration of independence’ was in average lower but displayed significantly growing trend, which suggests that these frames are consolidating a certain degree of stability in their sense.

Table 2. Degree of resonance of the meaning of selected frames on the meaning of the same frame in 2019.

The meanings in the last period for some frames – such as, ‘third way’, ‘indoctrination’, and ‘independent Catalonia’ (Cataluña independiente) – do not resonate so strongly with those in previous years. The meanings of some frames in 2019, such as ‘Catalan people’ or ‘la DUI’ (Catalan and Spanish acronym for the ‘unilateral declaration of independence’) seem to evoke more those in 2017 than in 2018. This could indicate that during the trial of pro-independence leaders in 2019, some expressions were again used in semantic contexts close to those during the campaign and aftermath of the 2017 referendum.

Given the relatively short period analyzed we cannot confidently predict the long-term legacies in terms meaning of the euphemisms and other expressions utilized by Catalan political actors. Nonetheless, this methodology, when applied to longer periods, would help assessing whether some semantic changes are durable and generate sufficient inertia or, if in the absence of political agents promoting certain meanings, they end up reverting to previous semantic contexts.

Fragmentation over time (number of dimensions)

The level of fragmentation of meaning across the entire period studied can also serve as proxy to understand the potential impact of the political context on media frames. shows that the vectors of certain frames are associated to a single semantic factor – for example, ‘Catalan conflict’, ‘sovereignty’, ‘Catalan people’, ‘federalism’, ‘identity’ (identidad), ‘independentism’, and ‘nation of nations’ – , others are associated to two or three different semantic factors – for example, ‘indoctrination’, ‘train wreck’, ‘political prisoner’ and ‘singularity’, ‘disconnection’, and ‘disloyalty’.

Table 3. Number of meaning dimensions (factor analysis) (2012–2019).

As with previous indicators, we observe that many terms display different overall fragmentation degree in each of the newspapers. This suggests that the frequency with which certain frames are used in specific semantic contexts varies. However, there is no observed association between salience and meaning fragmentation.Footnote11 For instance, the term ‘Catalan nationalism’ (nacionalismo catalán) has much more salience and displays more fragmentation in El Mundo than in El País. Meanwhile, the frame ‘political conflict’ (conflicto politico), that is much more salient in El Mundo, has more fragmentation in El País.

Semantic diversity within each space is sometimes, but not always, reflected in the number of overall semantic factors across the period. Some highly focalized frames, such as ‘right of self-determination’, ‘Statute’ (EstatutFootnote12) and ‘Catalan National Assembly’, keep a low fragmentation across time (1 factor). However, we find also low focalized terms linked to a single factor – for example, ‘Autonomous Community’ (Comunidad Autónoma). The fragmentation index appears to be sensitive to homonymous concepts with separable meanings over time but not to polysemous concepts.

In this sense, the variability of our indicators for semantic diversity (see standard deviation ) is not consistently reflected in the number of factors generated following the Chi-square rule. For instance, ‘third way’ despite its higher focalization degree in El Mundo, displays a higher semantic diversity, standard deviation, and an overall more fragmented meaning (2 semantic factors) than in El País (1 factor). Meanwhile, ‘political prisoners’ has the same standard deviation, and a slightly higher focalization and continuity in El Mundo, however in El Mundo this word has more abrupt jumps.

Anyhow, these complex associations between the different indices suggest that they are not redundant, and that to understand the specific nature of the impact of changes in the political context we need to dig even further and undertake a qualitative scrutiny. In studies with a wider thematic scope, a larger variety of corpus sources and longer time span, it is likely that the number of meaning dimensions increases. This analysis ‘only’ covers eight years and two newspapers. This same methodology could be used to vectorize corpuses covering decades and combine multiple types of texts (for instance, parliamentary transcripts, books, court sentences, song lyrics, etc.).

Semantic association with other frames

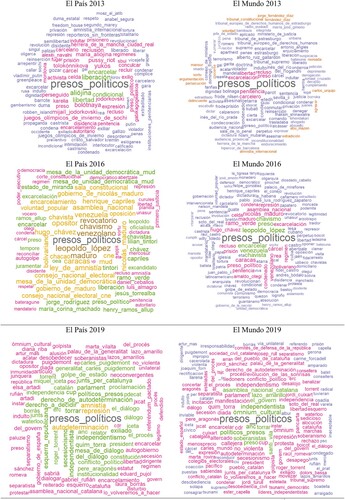

A qualitative analysis of the expressions associated with the frames studied in each semantic space is also useful to identify the impact of external shocks on the ideational spheres. For instance, in 2012, 2013 and 2014, ‘political prisoners’ was loosely associated to a variety of political contexts, such as Israel, Cuba, and the Basque Country, but mostly focused on the law and justice semantic realm and related to words, such as ‘sentence’ (condena), ‘jail’ (encarcelar) and ‘pardon’ (perdón). In 2015 and 2016 ‘political prisoners’ became largely associated to the Venezuelan political crisis, still without any relationship to Catalonia or Catalan politics. However, in 2017, expressions related to Catalan politics – such as ‘esteladas’ (Catalan independence flags) and ‘el procés’ (referring to secessionist process) – that during 2018 and 2019 almost completely replaced justice terminology and references to other political contexts as primary frames associated to ‘political prisoners’ (). This illustrates the relative success of the communication campaign by the nationalist camp that presented the jailed nationalist leaders charged for sedition and misuse of public funds, as political prisoners.

Figure 8. Frames cloud representing semantic association of ‘political prisoners’.Footnote13

This qualitative analysis also helps identify different political leaning in the newspapers reporting style. For instance, the term ‘catalanism’ (catalanismo) is initially associated to somewhat neutral concepts referring to political nationalism, such as ‘independence’, ‘Catalan nationalism’, ‘sovereignist process’, in both newspapers. However, in 2019, while in El País this term remains broadly associated to similar expressions, in El Mundo it becomes connected to frames that have a negative connotation such as ‘feudal’, ‘sabotage’, ‘segregation’, ‘rabble’ (chusma), ‘cowardice’ (cobardía) and ‘balcanization’ (balcanización) ().Footnote14 This diverse utilization of ‘catalanism’ exemplifies the process of competitive decontestation of meaning certain key terms in the public sphere.

Finally, this qualitative analysis illustrates how inertias in meanings vary across newspapers. The expression ‘third way’ changed drastically its sense in 2014 during the build-up of the referendum and the years that followed (, ). In both newspapers it became associated to the Catalan conflict in 2014, but El Mundo abandoned almost completely this semantic association in 2015 – it became linked to football in 2015 and to British politics in 2016 – meanwhile El País kept it for one more year (). Thus, ‘third way’ has a more stable pattern in El País (average of continuity of 0.46 versus 0.164 in El Mundo) but it is less focalized (average of 3.57 versus 5.14 in El Mundo).

Discussion and conclusions

Political frames are constructions that suggest ways in which policy issues should be thought about and dealt with. They help shed light on normative and empirical controversies and attest the power of mass communication in shaping our lives (Entman Citation1993, 395; Nelson and Kinder Citation1996, 1057–1058). As such, political frames can be considered essential elements in public policy and social research agendas. This article presents a new methodology to measure and understand the evolution of frames and to systematize our attempts to incorporate the analysis of the mutually constitutive relationship between politics and the ideational context in social scientific research. It introduces an unsupervised machine learning LSA technique to capture trajectories in meaning in very large corpus of texts.

We analyse the impact of the Catalan political crisis on the language used by newspapers in Madrid between 2012 and 2019 and identify changes in the semantic paths of key political frames that resonate with neo-institutional explanations. Our analyses reveal a variety of semantic dynamics worth studying in this and other case-studies. Further research would be required to triangulate the findings and analyse other communication corpuses to achieve a more complete understanding of the evolution in frames and the specific agents and micro-level causes that decisively contribute to the changes revealed.

The vectorization and scrutiny of the semantic spaces of El País and El Mundo show that the majority of the frames associated to the topic of Catalan politics gained salience in the semantic spaces of both newspapers during 2014 and 2017 coinciding with the organization of controversial independence referendums. These referendums and the political activism around them may be considered as ‘critical junctures’ (Collier and Collier Citation1991) not only at the level of party dynamics, but also at that of the ideational context. Catalan politicians and media generated external shocks that affected collective interpretations outside Catalonia. New political frames emerged, and others saw their meanings transformed or fragmented. In our empirical analysis we have revealed transformations, that from a neo-institutional perspective, can be construed as the opening of new semantic paths (the emergence of new words and expressions in a communicative context), as well as the branching (fragmentation of meanings), narrowing down (focalization of meanings), convergence (semantic association of different frames), and truncation of existing semantic paths. All these semantic dynamics, identified in the analysis of political frames in the Spanish press, may be encountered in other political contexts, and their analysis would likely contribute to a deeper understanding of the interplay between politics and language.

The introduction of politically loaded euphemisms and analogies to describe the Catalan conflict can be explained partly by the literal reproduction of speeches and responses of pro-independence and constitutionalist political leaders, as well as by a process of mimetic isomorphism (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983) by journalists and authors of opinion pieces, that end up adopting this new terminology. The increasing salience of Catalan neologisms, often replacing their Spanish translations – indicates that imitation was one of the mechanisms at play. As shown earlier, some new frames acquired an important degree of inertia and kept their semantic profile and salience for the rest of the period studied. Following a new institutional logic, the frequent use of some terms and the growing internalization by the readership, can be interpreted as self-reinforcing mechanisms that explain the consolidation of these new frames and connotations. Some of the dynamics observed at the ideational level in this study resemble the path dependent trajectories previously described by the neo-institutional literature at an organizational level (Mahoney Citation2000; Pierson Citation2000).

Meanwhile other expressions lost their centrality and/or reverted to previous meanings. The abandonment or replacement of these frames by new political tropes due to changes in the political context and communication strategies illustrate that not all frames are subject to path dependency and that sometimes frames require some ongoing exogenous mechanisms or ‘constant causes’ to supplement the initial impulse of the ‘historical causes’ activated at the critical junctures (Stinchcombe Citation1968, 103; Thelen Citation2003, 214–217). We show that despite many similarities, the overall semantic impact of this political crisis was higher in El Mundo than in El País. Not only the number and salience of frames revolving around the Catalan issue grew more significantly in the former, but also the continuity in meaning they display was weaker in the period analyzed.

The asymmetry and diversity in frame trajectories observed in our study suggest that media reporting on policy and political issues do not follow a somewhat linear Darwinian path, neither purely cyclical patterns (Downs Citation1972), but to a large degree bear a resemblance to a ‘punctuated equilibrium’ model (Krasner Citation1984; Baumgartner and Jones Citation2010; Holt and Barkemeyer Citation2012). The metaphor of punctuated equilibrium captures the branching and distinct evolution of different political frames. This argument has been previously used in area of linguistics to explain the rise and fall of languages through history (Dixon Citation1997) but never before to explain the evolution of specific political frames. The meaning trajectories of some key terms related to the Catalan political crisis appear to be impacted by contextual determinants such as the action of agents, the inertia of existing meaning structures, and interactions with competing frames. Historical or political events, such as in our case-study the secessionist challenge in Catalonia, become critical junctures that punctuate previous equilibria and generate new branching processes and inertias in the semantic realm. New equilibria were in some cases sustained by endogenous self-reinforcing mechanisms (within the Madrid’s press) and, in other occasions, by the continuous action of exogenous factors, such as political parties’ communication strategies.

Euphemisms and other political frames expanded impregnating and getting impregnated by a variety of semantic contexts that may end up provoking an important increase in the overall semantic diversity around Catalan politics. However, these multiple dynamics do not necessary produce an ever-expanding branching process, as that implicit in the speciation and genetic drift arguments in the original formulation of the punctuated equilibrium model in the paleobiology literature (Eldredge and Gould Citation1972). We show that frames sometimes converge and become tied to each other and that they can also revert to previous meanings.

The relationship among frames salience, semantic diversity and continuity of meaning is very complex and we do not observe collinearity at the level of aggregate sets of key frames. Further research at a more micro level may help understand better why sometimes an increase in the semantic salience of frames contributes to their semantic focalization and sometimes to a sort of spill-over effect by which these frames spread to neighbouring topics and become more semantically diverse.

Monitoring and comparing political frames become fundamental tasks to better understand ideas in power dynamics and evolving changes in public attitudes. Our goal was to introduce a tool that enables researchers to trace the salience and transformation of certain frames in communication. We used as illustration the changes in communication frames via the comparative analysis of semantic spaces in one specific case. In De Vreese’s (Citation2005) terminology, this study limits its scope to the area of ‘frame-building’ in the news but does not shed light on that of ‘framing-setting’ – the interactions between media frames and individuals that elicit effects in terms of information processing, attitudes, and behaviours. Further, research would be advised to elucidate the relationship between the changes observed in these frames and Spaniards’ political attitudes and preferences.

The relatively short period analyzed is another limitation that makes difficult assessing to what extent the evolution of frames can be also explained by incremental changes throughout longer periods of time, something that path dependence accounts tend to underestimate (Peters, Pierre, and King Citation2005, 1278). Likewise, we do not shed light on the micro processes of creation and reproduction of political frames, which could be either influenced by the editorial line, personal biases of influential journalists, pressures from political groups or simply adopted in a less purposeful way by imitation. This would require focusing on the trajectories of a smaller set of expressions and other methodologies. Although beyond of the scope of this paper, the indices presented above may be combined with sentiment analysis to try to clarify whether variations in frames’ salience and meaning were also accompanied by changes in terms of the sentiment they evoke.

New institutionalism has been considered more apt to explain stasis – path dependence, punctuated equilibriums, veto points – than change in systems, that is mostly attributed to exogenous factors (Blyth Citation2003, 701; Greif and Laitin Citation2004, 635-636). However, this is partly due to the relative scarcity of studies analyzing how systems are embedded within other systems and on the interaction between micro, meso and macro (material and ideational) structures. Exogenous factors become often endogenous when adopting a more macro perspective (Olivas Osuna Citation2014, 205–206, 215–217). By facilitating the quantification of semantic spaces and their evolution, we expect to contribute to open the range of plausible causal narratives that can be tested in social research. The ideational context is usually understudied and considered exogenous to policy dynamics and decision-making, largely due to the difficulties encountered in its measurement. We provide a method to capture an important part of the ideational domain so that it can be ‘endogenized’ in empirical studies.

In sum, the role of frames as sort of conveyor chains linking worldviews, institutions and actors operating at different levels deserves further academic attention. Our methodology bridges the gap between positivistic and constructivist stances on social sciences by enabling a reliable unsupervised quantification of the ideational context that can be then used to underpin comparative and constructivist explanations of policy and societal change.

Data

The corpora, matrices and scripts of this study are available at the following link: https://osf.io/rhtg4/?view_only=5612118ce3e54e049f3b36e43bdd1060 (XXXX 2023).

The dictionary containing the 216 frames used in the analyses regarding the case study: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/16zwYwGhChlm81vjiyud_yWuc_vBAdf51/edit?usp=drive_link&ouid=108517707969906445103&rtpof=true&sd=true.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Encarnación Hidalgo-Tenorio and Juan Rodríguez Teruel for their comments on early versions of the manuscript, and Enrique Clari for his help with the visualization of some indices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Although further re-orthogonalization using singular value decomposition (SVD) has been applied to mitigate this issue in some of the abovementioned alternatives (Hollis and Westbury Citation2016), some doubts remain about how to project new text units in the space generated (Lebret and Collobert Citation2015).

2 Text corpora, matrices and scripts used in this study are available: https://osf.io/rhtg4/?view_only=0c4468f462a24839ab3d2063f6bf9f98

3 Please note that the use of ‘frames' in this article refers sometimes also to individual words.

4 This means aligning pairs of years – i.e. 2012–2019, 2013–2019, and so on – so that all semantic spaces are expressed on the basis of that of 2019.

5 Both unique semantic spaces (one for El Mundo and one El País) are open access online in our dataset (see note 2). Each of them constitutes a matrix in which rows represent the frames/year. The words in these spaces are suffixed with the year they represent. For example, the row that represents the vector of the word freedom in the year 2017 will have the word ‘libertad_2017_’ in the beginning. In this way it will be comparable with for example ‘libertad_2019_’ measuring the change in meaning data.

6 See footnote 2.

7 The dictionary of frames created from the exploratory work is available online: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/16zwYwGhChlm81vjiyud_yWuc_vBAdf51/edit?usp=drive_link&ouid=108517707969906445103&rtpof=true&sd=true.

8 An imaginary region composed by the areas of Catalonia with low support for independence (Baldoli and Mocca Citation2021)

9 Reference to Russian presumed support to Catalan secessionism.

10 Catalan and Spanish acronym for Catalan National Assembly.

11 Low correlation (coefficient = 0.019, p-value = 0.788) based on the analysis of 210 frames without missing values.

12 Catalan term used often au lieu of ‘Catalan Statute of Autonomy'.

13 These frame clouds have been created using the ‘Wordcloud' package in R https://r-graph-gallery.com/wordcloud. The scripts, paper corpora and material are available online: https://osf.io/rhtg4/?view_only=0c4468f462a24839ab3d2063f6bf9f98

14 ‘Catalanism' has an average of continuity of 0.59 in El País, while 0.29 in El Mundo with even more abrupt jumps in focalization

15 This process follows a similar logic than that used in economics to compare sums of money overtime. You need to turn all amounts into a same basis that could be that of the first or last year, this is calculating either the Net Present Value or Net Future Value. The rotation parameter works similar to a financial discount rate.

16 Since each word has associated a fragmentation over time but the other two have one score for each comparison. Fragmentation over time is the number of factors estimated for the representations of a word along all years. For this reason, we measure the coincidence of this score in both spaces with Spearman correlation and the Kappa agreement coefficients. In the case of Continuity and Resonance we obtained score per pair of years – and

Seven in the case of El Mundo and six in the case of El País. We calculate in this case the Pearson correlation coefficients.

References

- Anderson, B. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Growth and Spread of Nationalism. New York and London: Verso.

- Balbi, S., and V. Esposito. 1998. “Comparing Advertising Campaigns by Means of Textual Data Analysis with External Information.” Actes des 4es Journées Internationales D’Analyse Statistique des Données Textuelles, UPRESA, Nice, 39–47.

- Baldoli, R., and E. Mocca. 2021. “Rescuing National Unity with Imagination: The Case of Tabarnia.” Nations and Nationalism 27 (4): 1063–1079.

- Barrio, A., O. Barberà, and J. Rodríguez-Teruel. 2018. “Spain Steals from us! The ‘Populist Drift’ of Catalan Regionalism.” Comparative European Politics 16 (6): 993–1011.

- Bartley, L., and E. Hidalgo-Tenorio. 2015. “Constructing Perceptions of Sexual Orientation: A Corpus-Based Critical Discourse Analysis of Transitivity in the Irish Press.” Estudios Irlandeses 10 (10): 14–34.

- Baumgartner, F. R., and B. D. Jones. 2010. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Blyth, M. M. 1997. “"Any More Bright Ideas?" The Ideational Turn of Comparative Political Economy.” Comparative Politics 29 (2): 229–250.

- Blyth, M. 2003. “Structures do not Come with an Instruction Sheet: Interests, Ideas, and Progress in Political Science.” Perspectives on Politics 1 (4): 695–706.

- Cai, Z., A. C. Graesser, L. Windsor, Q. Cheng, D. W. Shaffer, and X. Hu. 2018. “Impact of corpus size and dimensionality of LSA spaces from Wikipedia articles on AutoTutor answer evaluation.” Journal of Educational Data Mining.

- Castelló, E., and A. Capdevila. 2015. “Of war and Water: Metaphors and Citizenship Agency in the Newspapers Reporting the 9/11 Catalan Protest in 2012.” International Journal of Communication 9: 18.

- Checkel, J. T. 1998. “The Constructive Turn in International Relations Theory.” World Politics 50 (2): 324–348.

- Chong, D., and J. N. Druckman. 2007. “Framing Theory.” Annual Review of Political Science 10: 103–126.

- Collier, R. B., and D. Collier. 1991. Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Coppock, A., E. Ekins, and D. Kirby. 2018. “The Long-Lasting Effects of Newspaper Op-Eds on Public Opinion.” Quarterly Journal of Politics 13 (1): 59–87.

- David, P. A. 1985. “Clio and the Economics of QWERTY.” The American Economic Review 75 (2): 332–337.

- De Vreese, C. H. 2005. “News Framing: Theory and Typology.” Information Design Journal & Document Design 13 (1).

- De Vreese, C. H., J. Peter, and H. A. Semetko. 2001. “Framing Politics at the Launch of the Euro: A Cross-National Comparative Study of Frames in the News.” Political Communication 18 (2): 107–122.

- Díez Medrano, J. 2021. Framing Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- DiMaggio, P. J., and W. W. Powell. 1983. “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields.” American Sociological Review 48 (2): 147–160.

- Dixon, R. M. W. 1997. The Rise and Fall of Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Domènech, X., J. Moreno Luzón, M. L. Latorre, and J.-P. Rubiés. 2020. “El Procés de Cataluña en Perspectiva Histórica (Debate).” Ayer 120 (2): 327–355.

- Downs, A. 1972. “Up and Down with Ecology the ‘Issue-Attention Cycle’.” The Public Interest 28: 38–50.

- Dumais, S. T. 2004. “Latent Semantic Analysis.” Annual Review of Information Science and Technology 38: 188–230.

- Eldredge, N., and S. J. Gould. 1972. “Punctuated Equilibria: An Alternative to Phyletic Gradualism.” In Models in Paleobiology, edited by T. J. M. Schopf, 82–115. San Francisco: Freeman Cooper.

- Entman, R. 1993. “Framing: Towards Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” In McQuail’s Reader in Mass Communication Theory, edited by D. McQuail, 390–397.

- Entman, R. M. 2010. “Media Framing Biases and Political Power: Explaining Slant in News of Campaign.” Journalism 11 (4): 389–408.

- Ethayarajh, K. 2019. “How contextual are contextualized word representations? Comparing the geometry of BERT, ELMo, and GPT-2 Embeddings.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.00512.

- Fillmore, C. J. 1976. “Frame Semantics and the Nature of Language.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences: Conference on the Origin and Development of Language and Speech 280 (1): 20–32.

- Fillmore, C. J. 1977. “Topics in Lexical Semantics.” In Current Issues in Linguistic Theory, edited by R. Cole, 76–138. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Freeden, M. 1996. Ideologies and Political Theory: A Conceptual Approach. Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Freeden, M. 2013. The Political Theory of Political Thinking: The Anatomy of a Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Furnas, G. W., S. Deerwester, S. T. Durnais, T. K. Landauer, R. A. Harshman, L. A. Streeter, and K. E. Lochbaum. 1988. “Information Retrieval Using a Singular Value Decomposition Model of Latent Semantic Structure.” ACM SIGIR Forum 51 (2): 90–105.

- García, C. 2021. “When an Efficient Use of Strategic Communication (Public Diplomacy and Public Relations) to Internationalize a Domestic Conflict Is Not Enough to Gain International Political Support: The Catalan Case (2012-2017).” International Journal of Strategic Communication 15 (4): 293–309.

- Gellner, E. 1983. Nations and Nationalism. Cornell University Press.

- Goffman, E. 1974. Frame Analysis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Goldstein, J., and R. O. Keohane. 1993. “1. Ideas and Foreign Policy: An Analytical Framework.” In Ideas and Foreign Policy, 3–30. Cornell University Press.

- Goldstein, A., Z. Zada, E. Buchnik, M. Schain, A. Price, B. Aubrey, S. A. Nastase, et al. 2022. “Shared Computational Principles for Language Processing in Humans and Deep Language Models.” Nature Neuroscience 25 (3): 369–380.

- Granovetter, M. 1985. “Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness.” American Journal of Sociology 91 (3): 481–510.

- Greif, A., and D. D. Laitin. 2004. “A Theory of Endogenous Institutional Change.” American Political Science Review 98 (4): 633–652.

- Hall, P. A., and R. C. Taylor. 1996. “Political Science and the Three new Institutionalisms.” Political Studies 44 (5): 936–957.

- Halliday, M. A. 1967. “Notes on Transitivity and Theme in English: Part 2.” Journal of Linguistics 3 (2): 199–244.

- Halliday, M. A. 1973. Explorations in the Functions of Language. London: Edward Arnold.

- Halliday, M. A., and C. M. Matthiessen. 2014. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

- Hay, C. 2004. “Ideas, Interests and Institutions in the Comparative Political Economy of Great Transformations.” Review of International Political Economy 11 (1): 204–226.

- Hay, C. 2011. “Ideas and the Construction of Interests.” In Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research, edited by D. Beland and R. H. Cox, 65–82.

- Hidalgo-Tenorio, E., M.-Á. Benítez-Castro, and F. D. Cesare, eds. 2019. Populist Discourse: Critical Approaches to Contemporary Politics. Routledge.

- Hoffman, P., M. A. Lambon Ralph, and T. T. Rogers. 2013. “Semantic Diversity: A Measure of Semantic Ambiguity Based on Variability in the Contextual Usage of Words.” Behavior Research Methods 45: 718–730.

- Hoffman, P., T. T. Rogers, and M. A. Lambon Ralph. 2011. “Semantic Diversity Accounts for the “Missing” Word Frequency Effect in Stroke Aphasia: Insights Using a Novel Method to Quantify Contextual Variability in Meaning.” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 23 (9): 2432–2446.

- Hollis, G., and C. Westbury. 2016. “The Principals of Meaning: Extracting Semantic Dimensions from co-Occurrence Models of Semantics.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 23: 1744–1756.

- Holt, D., and R. Barkemeyer. 2012. “Media Coverage of Sustainable Development Issues–Attention Cycles or Punctuated Equilibrium?” Sustainable Development 20 (1): 1–15.

- Humlebæk, C., and M. F. Hau. 2020. “From National Holiday to Independence Day: Changing Perceptions of the “Diada”.” Genealogy 4 (1): 31.

- Iyengar, S. 1987. “Television News and Citizens’ Explanations of National Affairs.” American Political Science Review 81 (3): 815–831.

- Jorge-Botana, G., R. Olmos, and J. M. Luzón. 2018. “Word Maturity Indices with Latent Semantic Analysis: Why, When, and Where is Procrustes Rotation Applied?” WIRES Cognitive Science 9 (1): e1457.

- Jorge-Botana, G., R. Olmos, and J. M. Luzón. 2019. “Could LSA Become a “Bifactor” Model? Towards a Model with General and Group Factors.” Expert Systems with Applications 131: 71–80.

- Jorge-Botana, G., R. Olmos, and V. Sanjosé. 2017. “Predicting Word Maturity from Frequency and Semantic Diversity: A Computational Study.” Discourse Processes 54 (8): 682–694.

- Jorge-Botana, G., R. Ricardo Olmos, and J. M. Luzón. 2020. “Bridging the Theoretical Gap Between Semantic Representation Models Without the Pressure of a Ranking: Some Lessons Learnt from LSA.” Cognitive Processing 21: 1–21.

- Kahneman, D., and A. Tversky. 1984. “Choices, Values, and Frames.” American Psychologist 39: 341–350.

- Kingdon, J. W. 1984. Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies. New York: Harper Collins.

- Krasner, S. D. 1984. “Approaches to the State: Alternative Conceptions and Historical Dynamics.” Comparative Politics 16 (2): 223–246.

- Kuhn, T. S. 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.