ABSTRACT

The Russian invasion at the beginning of 2022 forced many Ukrainians to find refuge in safer places. Using unique survey data collected in the early days of the war, this research note turns to Ukrainian refugees’ opinions in two host countries: Germany and Poland. We are interested in how this – otherwise hard-to-reach und so far understudied – group of people evaluated their country’s potential European Union (EU) accession at that very specific moment in time, whether there existed differences in perceptions between the interviewees in the two countries, and what the predictors might have been. Overall, our findings indicate that the Ukrainian refugees interviewed generally supported Ukraine's accession to the EU, with no significant differences observed between the two host countries. Furthermore, both utilitarian and identity-driven factors played minor roles in shaping support for a future EU membership. These insights are not only valuable for academic research but also hold relevance for political stakeholders at both national and EU level.

Introduction

On 24 February 2022, Russia openly invaded Ukraine. This war of aggression – decreed by Russian president Vladimir Putin – escalated the conflict ongoing in eastern Ukraine since 2014, to the entire Ukrainian territory. The war posed an imminent threat, leading to large-scale internal displacement, and ultimately causing many Ukrainians to flee their country to find protection from Russian attacks. As many men were drafted for military service, it was mainly women and children – and especially residents of eastern Ukraine – who made their way out (Botelho and Hägele Citation2023). The majority of people who left Ukraine fled to neighbouring countries; Poland taking in the highest numbers as of today, with other states, such as Germany also being frequent destinations (UNHCR Citation2024).

With a war on the European Union’s (EU) doorstep the community was faced with the responsibility to take a clear stance (Bosse Citation2022). In such cases, the performance of the EU is usually analysed through the lenses of EU member state’s policymakers or public opinion within those states (Genschel, Leek, and Weyns Citation2023; Steiner et al. Citation2023). However, a different perspective is to look at the evaluation by those on the recipient side. So far, the scientific discourse on Ukrainian refugeesFootnote1 has been limited – even though, nearly 35% of the Ukrainian population was displaced due to the war (IOM Citation2023) and according to current calculations, about 5.5 million Ukrainian refugees are currently recorded in Europe (UNHCR Citation2024). This leads to a major representation gap in public opinion research for this group of people. The perspective of those affected by the war is, however, crucial considering the potential future EU accession of Ukraine. Their views are not only relevant for academic discussions but also informative for shaping the future agenda of national and EU policymakers. Our research note aims to contribute to this currently unexplored research angle by focusing explicitly on the very early days of the full-scale Russian invasion.

We analyse unique survey data provided by the ‘Online Survey of Ukrainian Refugees' (OSUR) project which was collected from April to May 2022, i.e. shortly after the escalation of the war, from respondents recruited via social media in Germany and Poland. We seek to understand how these refugees perceived a potential EU membership of their own country, whether there existed differences in perceptions among people residing in the two countries, and what factors may underlie these associations. This is achieved by descriptively comparing the respondents in both states and carrying out regression analyses.

Our results indicate that most interviewed refugees in Germany and Poland would indeed support their country’s membership in the EU. While refugees in our German sample were slightly more supportive of the Maidan protests back in the day, they seemed to be a bit more critical towards their country’s current accession ambitions compared to the refugees interviewed in Poland. Both utilitarian and identity-driven factors played a minor role in shaping support for EU membership. This suggests that overall support for EU membership within war-ridden candidate nations tends to be high, although well-known explanations still subtly influence public preferences.

Our research note makes two important contributions: Firstly, we explicitly focus, for the first time, on studying attitudes towards the EU among Ukrainian refugees, a group that is typically challenging to access. The majority of Ukrainian refugees in our study express support for their country's accession to the EU, with this support also correlating with utilitarian and identity-driven considerations. Secondly, our research note examines the early stages of the escalating conflict. During this period, the political response from the EU and some member states remained hesitant. Despite this considerable uncertainty, the EU received positive evaluations from the surveyed respondents. This is an important signal for future engagement with the country.

Our research note proceeds as follows: In the first step, we engage with European integration theory, originally developed for the EU citizenry. We adapt these assumptions to our sample of Ukrainian refugees and their assessment towards EU accession. Rather than formulating strict hypotheses, our research note takes an explorative approach by asking and contributing to guiding research questions. In the second step, we incorporate insights into the evaluation of Ukraine's potential EU accession from the perspective of residents in Ukraine. We distinguish between previously published scholarly findings and recent surveys to offer a nuanced perspective. Next, we focus on the two refugee host countries central to this research note: Germany and Poland. We provide background information on the numbers of Ukrainian refugees entering these countries and the ‘welcoming culture’ they encounter. This context helps us understand how refugees are treated in these countries and how this might influence their evaluation of the EU. In the last part of the paper, we introduce our data and analysis strategy before presenting the results and concluding with an overarching discussion.

Public opinion towards the EU

Insights from European integration theory

Since the end of the permissive consensus among the EU population towards the European integration project, research has increasingly focussed on what might explain the emerging constraining dissensus (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009). Two explanatory models remain relevant to this day (Reinl and Braun Citation2023; Reinl and Evans Citation2021). The first are utilitarian considerations, suggesting that EU membership of a country is viewed by its population through the lens of classical cost-benefit considerations. If one expects economic advantages from the EU – either for oneself or one's country – or already experiences them, support for further integration is higher (Gabel and Whitten Citation1997; Boomgaarden et al. Citation2011; Vasilopoulou and Talving Citation2020). The second model refers to identity feelings, indicating that prevailing feelings of identity within the EU population play a significant role. If people identify with Europe, this also enhances their support for the integration project (Pryke Citation2020; Fligstein, Polyakova, and Sandholtz Citation2012). While European identity’s role in explaining EU attitudes increases, the explanatory power of utility does not decrease (Van Klingeren, Boomgaarden, and De Vreese Citation2013). The two explanatory factors, both on the individual as well as on the contextual level are based on similar propositions and thus are increasingly seen in interaction with each other (Katsanidou and Mayne Citation2024). On top of that, research has shown that these two influencing factors are not only evident among individuals already residing within the EU, but also exist within candidate countries. Utilitarian judgements are stronger when considering Romania and Bulgaria separately (Gherghina Citation2010), while human capital (Elgün and Tillman Citation2007) and benefits from political change towards liberalization and integration (Doyle and Fidrmuc Citation2006) are highlighted as more important drivers, and closer to identity when looking at the whole 2004 EU enlargement wave.

Following from that, we are leveraging these research insights and, for the first time, applying them to refugees from a candidate country seeking refuge within the EU. Much like individuals residing in candidate countries themselves, we posit that both cost-benefit analyses and identity considerations could be crucial for refugees’ assessment of the EU. The objective of our research note is to explore a novel research area that, to our knowledge, has not been studied scientifically before. Thus, we adopt an exploratory approach to examine public opinion among Ukrainian refugees by addressing two guiding research questions (RQs):

RQ1. Refugee EU support: Do the Ukrainian refugees surveyed in our study, on average, hold positive or negative views toward their country's EU membership?

RQ2. Observational linkage: What attitudinal connections are evident regarding refugees’ support for EU membership across the two countries?

Support for EU membership – snapshots from Ukraine before the full-scale invasion

Language and cultural heritage have long been cleavages dividing the pro-EU Ukrainian speaking population from the Russian speaking parts of the country (Pop-Eleches and Robertson Citation2018; White, McAllister, and Feklyunina Citation2010). In the early 2000s, the average supporter of Ukraine’s EU membership was relatively young, had a middle income, lived in the western parts of the country, and, above all, held a European identity. Conversely, the same analysis also indicates that those who predominantly opposed the EU were generally middle-aged (30–59) or older (over 60 years old) (White, Korosteleva, and Mcallister Citation2008).

The so-called ‘Euromaidan' protests emerging in 2013 made this division between citizens who supported a pro-Russian approach and those who were firmly pro-European even more apparent (Kulyk Citation2016). The Euromaidan protests were a wave of large-scale demonstrations directly responding to the unilateral decision of the then Ukrainian president Yanukovych to delay the signing of the European Union Association Agreement, starting on November 21st 2013, the day of the announced ‘pause' in relations with the EU (Sviatnenko and Vinogradov Citation2014). This president’s decision was also in defiance of the Ukrainian parliament which earlier that year had overwhelmingly approved finalizing the agreement with the EU. The scope of the protests widened with severe calls for the resignation of the second Azarov government, due to its abrupt policy shift from Pro-European to Pro-Russian. Police brutality magnified the scale of protest from November onwards, while in combination with anti-protest laws in January and February 2014 it radicalized the protesters and transformed the peaceful demonstrations into violent clashes of national scope against the government and what it represented. To calm things down the government backed down and struck a deal with the protesters. However, instead of bringing peace, this deal led to a further escalation of the conflict. As the protesters took control over Kyiv and president Yanukovych fled the city, the Ukrainian parliament voted to remove him from office (for a timeline see Zelinska Citation2017). The result was a pro-European turn in Ukrainian politics, including a ten-year ban on pro-Russian civil servants of the former Yanukovych government from office. The profile of the average protester was male, over 30 years of age, Ukrainian speaker, highly educated and in full time employment (Onuch Citation2014). Euromaidan protests bared similarities to the Orange RevolutionFootnote2 in that they were viewed differently by their sympathisers and by the Ukrainian government at the time. Sympathisers saw this as resistance against the corrupt authoritarian regime, while the regime framed it as a western intervention hostile to the country (Kulyk Citation2016). The Euromaidan protests were also followed by an Anti-maidan counter-movement, which initially voiced support for president Yanukovych and his policies, and later became the basis of pro-Russian public opinion (Zelinska Citation2017).

All these events led to significant shifts in public opinion towards the EU among the Ukrainian population. Public support for joining the EU increased somewhat in the aftermath of the Euromaidan, initially hesitantly (Pop-Eleches and Robertson Citation2018) and then more persistently (Yakymenko and Pashkov Citation2018). Compared to other Eastern European countries (such as Moldova and Belarus), the desire of Ukrainians to join the EU was significantly higher in 2018 (Toshkov, Mazepus, and Dimitrova Citation2023). Additionally, there was a decline in support for strong political and economic ties with Russia after the Euromaidan (Pop-Eleches and Robertson Citation2018), while Ukrainian national identity gained importance during this period (Kulyk Citation2016), not only in the western regions but also in the eastern regions of the countryFootnote3 (Gentile Citation2015).

Support for EU membership – Snapshots from Ukraine after the full-scale invasion

Since the escalation of the war happened not so long ago, scientific evidence on the topic is still quite scarce. Nevertheless, recent public opinion surveys on people still residing in Ukraine provide us with some initial insights. We would like to highlight two polls here in particular.

First, the National Democratic Institute (NDI) carried out nationwide telephone polls in Ukraine in May and August 2022 as well as in January and May 2023 to track public opinion against the backdrop of the war (NDI Citation2023). In their May 2023 poll, 92% of the survey respondents declared their support for joining the EU (lowest value in May 2022 with 90%). These surveys, however, failed to interview citizens from the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, the city of Sevastopol, and the Russian occupied Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts – the areas most affected by the Russian aggression.

Second, in April/May 2023 the Eighth Annual Ukrainian Municipal Survey (International Republican Institute Citation2023) collected public opinion data via face-to-face interviews in 21 regional capitals of Ukraine. Over-time trends revealed that public support for Ukraine joining the EU constantly rose in all municipalities between 2015 and 2023. In 2023, more than 80% of respondents preferred EU membership over the Customs Union of Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan or any other union. Only in the cities of Dnipro (79%), Mykolaiv (78%), Kharkiv (77%), and Odesa (66%) average support for joining the EU was somewhat lower. Yet upon comparing their local approval ratings from 2023 with earlier values, an immense increase of EU approval becomes apparent there, too. In Odesa, the pre-2021 approval rate was just around 30% for most of the years, rising by over 30 percentage points after the escalation of the war. It should be noted that this study was not fielded in rural areas, and once again warzones (Crimea, Simferopol, Donetsk, Luhansk, Mariupol, Sievierodonets, Kherson) were not part of the sample. Those Eastern Ukrainian regions, however, used to be the most anti-EU ones in the whole country (Gentile Citation2015).

Thus, despite the valuable insights provided by these two types of public opinion data collection, a significant limitation is their lack of representation across all areas within Ukraine. Additionally, they explicitly exclude Ukrainians who sought refuge abroad. With approximately 19% of Ukrainians (based on 2021 population figures) currently affected by this status, a significant portion of the population was not covered by either study, constituting a notable research gap.

Based on that, the objective of our study is to contribute exactly to this academic void and to shed light on the attitudes of those people who have left their home country due to the war. We do so by focussing on displaced Ukrainians in two refugee host countries, Germany and Poland, and their EU evaluation in the early days after the escalation of the war. The next section is devoted to describing the context in the two host countries in more detail, thereby providing important background information on the conditions prevailing there in spring 2022.

Ukrainian refugees in Germany in Poland

People fleeing Ukraine – what we know so far

By the end of 2022, about eight million people had crossed the border of Ukraine in search of security (Bird and Noumon Citation2022) and numbers are still counting. These people by no means perfectly represent their home population, neither in demographic nor socio-political terms. Instead, they provide insights into the refugee group itself. Refugees represent a self-selected group that had the will and (financial; health related) capabilities to flee. This leads to them heaving a very different set of experiences compared to those who stayed: being uprooted, receiving help, being relatively safer etc. Overall, Ukrainian refugees by the end of 2022 were mainly female (66%), relatively young in age (including 33% children) (Botelho and Hägele Citation2023), highly educated (69% holding at least a university degree) (UNHCR Citation2024) and comparatively wealthy (Kohlenberger et al. Citation2022; Panchenko Citation2022).

With regard to the two countries we are focussing on in this study – Germany and Poland – other non-probability surveys that collected their data approximately at the same time as OSUR have shown that refugees in Poland had less often a higher (tertiary) education – compared to Austria – (Kohlenberger et al. Citation2022).Footnote4 In contrast to that, Ukrainian refugees in Germany appeared to be highly educated (Panchenko Citation2022). Thus, it seems that more educated people were rather likely to reach out – cognitively and financially – to countries other than their immediate neighbours. In addition, people favouring living in Germany over another country mentioned that they had family or friends there (Panchenko Citation2022). This already existing social integration could have therefore been another distinguishing factor of refugees living in the two countries.

In summary, it can be assumed that more educated and financially prosperous Ukrainians might have sought asylum in Western European countries due to better economic conditions and job opportunities there. In contrast, less prosperous and less educated refugees might have chosen to leave the country towards Poland or another neighbouring state. A destination much closer to Ukraine – in geographical and cultural terms.

Public opinion in refugee host countries – what we know so far

By spring 2023, both Germany and Poland had already welcomed over one million Ukrainian refugees (UNHCR Citation2024). Compared to the situation faced by refugees entering Poland in 2015 and 2016, Polish people were much more welcoming this time (Hargrave, Homel, and Drazanova Citation2023). For polish citizens their acceptance of the refugees was mainly dependent on their predispositions to immigration, their European identity, and most importantly their perceptions of the war; the experience of having Russia invade a neighbour country shifted their perspective on refugees (Moise, Dennison, and Kriesi Citation2023). According to a Flash Eurobarometer of April 2022, Polish people gave a higher approval than the EU average to the EU policy of welcoming Ukrainian people fleeing the war (61% fully approved, as opposed to 55% in the EU-average) (Eurobarometer Citation2022). Moreover, they were also much more positive towards the statement that Ukraine should join the EU when it is ready with 81% of the respondents fully agreeing or tending to agree (66% of the Europeans did so). It is also important to note that Polish citizens predominantly supported economic sanctions against Russia (73% voiced full support, as opposed to 55% on EU-average) and banning state-owned Russian media from broadcasting in the EU (64%, as opposed to 41% on EU-average). Hence, Ukrainian refugees – on average – experienced a rather welcoming culture among the Polish host population. According to a 2023 poll in Ukraine, Poland and the Polish President Duda were considered to be the most important supporters of their country (The Kyiv Independent news desk Citation2023).

In Germany, too, the mood towards refugees from Ukraine seemed to be quite positive, especially at the beginning of the war. In the same Flash Eurobarometer fielded in April 2022 Germans were positive towards the EU policy of welcoming people fleeing the war, but much closer to the EU average (56%).Footnote5 Economic sanctions against Russia were fully supported by 57% of the respondents, but banning state-owned Russian media from broadcasting in the EU was not a significant issue in Germany (fully supported by only 39% of respondents). Moreover, the country was rather divided over delivering heavy weapons to Ukraine in April 2022 (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen Citation2022) and Germans were far more cautious regarding the question as to whether Ukraine should join the EU when it is ready. Only 26% fully agreed and 35% tended to agree, both lower than the EU average (Eurobarometer Citation2022; Höltmann, Hutter, and Rößler-Prokhorenko Citation2022; Mayer et al. Citation2022). Noteworthy is that Germans experienced the Russian invasion with lower perceptions of threat, while having lower cultural proximity to Ukraine, combining their attitudes more tightly to their previous predisposition towards immigrants (Moise, Dennison, and Kriesi Citation2023). Following from that, Ukrainians fleeing the war should fell at ease in Germany, but maybe their expectations of full and unconditional support have not been met.

Data and methods

Sample

In this research note we use survey data collected through the ‘Online Survey of Ukrainian Refugees’ project, conducted by GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences (Pötzschke et al. Citation2022). The survey was realized from April 15 to May 1, 2022, targeting individuals staying in Germany or Poland who had fled Ukraine since the beginning of 2022. Respondents were recruited via targeted advertisements on Facebook and Instagram. The aim of the project was to collect timely information on these forced migrants who left the country shortly after the escalation of Russia’s violence against Ukraine. However, most established sampling procedures are not well suited to recruit migrants shortly after their arrival in a country or while they are still on the move. Register-based approaches, such as used by Brücker et al. (Citation2022), for example, require that the target population is indeed registered in the databases that are used as sampling frame and that they have at least semi-stable accommodation where they can be reached. Consequently, the implementation of such an approach is only feasible after a certain amount of time has passed which is why the above-mentioned study started its data collection only in August 2022. In earlier cases of large refugee movements location-based sampling, i.e. recruitment in refugee housing facilities, has often been employed to produce timely information on the target population’s situation in Germany (e.g. Emmer, Richter, and Kunst Citation2016; Haug, Lochner, and Huber Citation2019). However, this methodological choice results in a sample that is recruited at a limited number of locations where research teams are furthermore likely to face gate keepers. Additionally, only individuals who are at such facilities at the time of sampling can be included.

Given these limitations, the present study used targeted advertisements on Meta’s social networking platforms to recruit respondents. Available sources indicate that Meta’s userbase in Ukraine corresponded to approx. 41% of the Ukrainian population aged 13 years or older in early 2022 and to roughly 50% of the country’s overall internet users (Kemp Citation2022).

In contrast to other sampling methods, the use of social networking sites allowed us to realize comparatively large samples shortly after the Russian invasion and the start of the refugee influx. It, furthermore, meant that these samples were not limited to individuals located in a select number of cities or municipalities at the time of the interview, in fact, it did not even necessitate them being stationary but allowed us to potentially survey refugees while they were still on route. Consequently, our data provides a snapshot of refugees’ attitudes at a very early stage of the intensified war and in a very rapidly changing context.

For our recruitment, we created short advertisements that included a link to an externally hosted survey and encouraged targeted users to click on said link to participate in the survey (see Figure A2 in the online Appendix for the overall sampling process). These advertisements were displayed to a subset of Meta users that corresponded to the targeting criteria we had defined in Meta’s advertisement interface (Facebook Advertisement Manager). More specifically, we targeted users of Facebook, Instagram, and the Facebook messenger who were categorized as people who live in or have recently been to Germany or Poland, being at least 18 years of age and using the Ukrainian language. This rather broad targeting was combined with an ad text clearly indicating that we were targeting recent Ukrainian refugees. Specific information on the targeting approach and examples of the advertisements can be found in the online Appendix. More general information on the sampling approach and its implementation is provided in Pötzschke et al. (Citation2023). In addition to the advertisements, we implemented a snowball element in the survey and posted an invitation to participate in select groups geared towards Ukrainians in Germany and Poland. Finally, respondents could reach our survey via its Facebook page. However, as expected based on previous research, almost all respondents were recruited through the advertisements (see Figure A2 in the online Appendix).

The mentioned advertisements and the accompanying Facebook page were designed and displayed in Ukrainian language only. This decision was based on previous research that had shown that most Ukrainian speaking migrants reacted very negatively when being exposed to advertisements in Russian language (Ersanilli and van der Gaag Citation2020). Likewise, the online questionnaire was fielded in Ukrainian language solely. The respondents did not receive an incentive for their participation.

In addition to the targeting, the questionnaire included instruments that allowed confirming that respondents belong to the target population. During data collection, the latter was defined as adult individuals that have been living in Ukraine before January 1, 2022, left the country thereafter and were located either in Poland or Germany at the time of the survey. In our advertisements we opted for January 1 as a reference date as some individuals might felt forced to leave the country in anticipation of the looming invasion shortly before it began.

We decided to focus on Germany and Poland as survey countries as they share several communalities but also differences that allow for meaningful comparisons. More specifically, both are similar in the sense that they received large numbers of Ukrainian refugees in the direct aftermath of the Russian invasion. This aspect was also an important inclusion criterion from a practical point of view as focussing on countries hosting comparatively small numbers of refugees would have resulted in smaller subsamples. However, Germany and Poland also differ in various relevant aspects such as their geographic and cultural proximity to Ukraine, the social structure of their pre-existing Ukrainian immigrant communities and the extent to which they provide refuge to individuals fleeing conflicts in other world regions.

Between 15 April and 1 May, a total of 1,158 adults participated in our survey and met the criteria of our target population, 668 (58%) were located in Germany and 490 (42%) in Poland. However, due to item nonresponse the sample size drops to 1,036 adults, which is also the sample size that we will refer to throughout our analyses.

Hence, the described sampling approach allowed us to realize a timely cross-national survey of recent forced migrants. However, it is important to note that, by employing Meta’s Social Networking Sites (SNS) for sampling purposes, we did not have control over any nonresponse mechanisms and respondents self-selection into the sample, which results in a nonprobability sample (Cornesse et al. Citation2020). The most important limitation resulting from this non-probability approach is that our descriptive results cannot be generalized to the larger group of interest. Despite this limitation, non-probability data can provide important first insights in times of rapidly developing migration movements, which led even German ministries to commission data collection endeavours combining location sampling and recruitment through refugee specific websites (BMI Citation2022).

Variables

In our analyses ( provides an overview of descriptive statistics for all variables), we focus on one outcome variable that has been selected to contribute to the research questions introduced in Section 2. We asked respondents to rate the following statement: ‘Ukraine should join the European Union' on a scale where 1 meant ‘fully disagree' and 4 ‘fully agree'.

Table 1. Outcome and predictor variables by current country of residence.

To determine whether respondents’ EU support is primarily motivated by identity or utilitarian driven considerations, we examine these links in our regression analysis.

To assess respondents’ utilitarian objectives, we utilize a survey question asking for current satisfaction with EU aid. Respondents were given the following question: ‘How satisfied are you with the overall support Ukraine has received from the European Union since February 24, 2022?'. The response scale ranged from 1 (‘very dissatisfied') to 7 (‘very satisfied'). The survey did not include any questions on the EU's impact on the national economy or individual economic benefits.

Considering respondents’ emotional attachment to Europe, we utilize a survey question that evaluates attitudes towards the past Euromaidan protests. This question effectively captures long-term support for European integration. Support for the Euromaidan protests in the past may positively influence one's current rating of the EU. Respondents were asked: ‘Do you think that the Euromaidan has brought more benefit or harm to Ukraine?'. The response categories were ‘More harm than benefit’ (1), ‘Neither nor' (2), and ‘More benefit than harm' (3).

Besides these two primary independent variables, satisfaction with the aid provided by the current host country could also influence the evaluation of EU membership. Therefore, we also take into account the following two questions: Support for Ukraine by host country: ‘How satisfied are you with the support Ukraine has received so far by your country of residence?' (1 ‘very dissatisfied' to 7 ‘very satisfied'). We assume that the greater the satisfaction with the assistance of the host country, the more positive the evaluation of Ukraine's accession to the EU. This assumption is made because respondents may find it difficult to distinguish between the different political layers and the host country could serve as a proxy for the entire EU. Personal support by host country: ‘How satisfied are you with the support you have personally received so far in your country of residence?' (1 ‘very dissatisfied' to 7 ‘very satisfied'). This variable could be highly correlated with the variables satisfaction with EU aid and support for Ukraine by host country; thus we are controlling for its effect.

Moreover, the following variables serve as additional predictor variables in our regression analyses. We draw on these variables as they generally demonstrated an effect on EU support (of people in the EU itself) in the previous literature (Boomgaarden et al. Citation2011) and supplement them with a Ukraine-specific indicator.

Female: Respondents who self-identify as ‘female' or ‘diverse' (3 respondents identify as ‘diverse') have been coded 1, whereas respondents identifying as ‘male' have been coded 0. We expect that men are more likely to support the EU than women (Mayne and Katsanidou Citation2023).

Age: Respondents have been asked for the year of birth, which then was used to create an age variable (in years). We expect a curvilinear relationship between EU support and age (with respondents in their mid-40s being the least likely to think EU membership is a good idea) (Mayne and Katsanidou Citation2023).

University: The dichotomous variable ‘university' is based on educational attainment with 13 response categories that have been collapsed into those with a ‘university degree' (1) and those without a ‘university degree' (0). The higher educated a person, the more likely it is that the person would support the EU (Hakhverdian et al. Citation2013).

Financial assessment of household: Participants were asked the following question: ‘Please remember the financial situation of your household in Ukraine in the second half of 2021. How would you rate your household income in the second half of 2021?'. The following response categories were offered: 1 ‘very difficult to get along', 2 ‘difficult to get along'. 3 ‘get along', 4 ‘live comfortably'. The wealthier a person’s household, the more likely it is that this person would support the EU (Gabel Citation1998).

Frontline oblast: We asked respondents in which Ukrainian oblast they lived for three or more months without interruption before leaving Ukraine. Based on this information, a dummy variable was created and set to 1 if respondents reported Luhansk, Donezk, Zaporizhzja, Kherson, Crimea, or Sevastopol. We suspect that if a person has previously lived in a border region that is heavily affected by the war, they are more likely to be in favour of joining the EU, as this could offer greater security for their region.

Analysis strategy

The statistical analyses will encompass two steps. First, we present univariate statistics describing the level of EU membership support from the perspective of refugees in Germany and Poland (RQ1). Second, we test for the determinants of EU membership support; referring to RQ2.

The outcome variable will be modelled utilizing linear regression analysis. However, since the outcome variable can also be considered to be ordinally scaled, we will back up our results by an estimating ordered logit model (Figure A4 in the Appendix). Furthermore, in terms of describing the uncertainty of the regression coefficients we will utilize a resampling approach (bootstrapping with 1000 replications per model) to calculate the respective standard errors. This is one recommended approach when dealing with nonprobability samples (see also last paragraph of Section 4.1), since they do not satisfy the statistical assumptions of probability-based samples (Baker et al. Citation2013a, Citation2013b). All analyses were conducted using Stata 17.0; we used the estout ado (Jann Citation2005, Citation2007) to create tables and the coefplot ado (Jann Citation2014) to plot the results of the regression models.

Results

Sample description

provides an overview of the outcome and predictor variables for the German and Polish sample of Ukrainian refugees (Table A1 in the Appendix provides a correlation matrix of all variables). Respondents in both countries were highly in favour of EU membership.Footnote6 With regard to our first research question (RQ1), we can thus say that support for Ukraine’s membership in the EU was high in both our samples and reached similar values as in the areas of Ukraine that have been covered by previous surveys (only covering oblasts currently not directly affected by the armed conflict). Moreover, we could not see (substantial) differences among the two host countries (see also Figure A3 in the Appendix). Even though average support among respondents in Poland was higher than in Germany, differences did not reach statistically significant ratios.

However, we did observe differences in terms of sample composition among both countries. Referring to utilitarian considerations, measured via satisfaction with EU aid provided to Ukraine, respondents in both countries were rather satisfied, but the overall picture was not entirely positive. The ratings were minimally higher in Germany compared to Poland, although this difference was not statistically significant. With view to European identity, participants staying in Poland were slightly more consent that the Euromaidan provided ‘More harm than benefit' to the Ukrainian society (14% vs 11%) than refugees staying in Germany (p = 0.11).

On top of that, we detected cross-country differences for the indicators university degree, financial assessment of household, and satisfaction with support by host country for oneself as well as Ukraine. That is, the sample of Ukrainian refugees staying in Germany was considerably wealthier and better educated (by about 13 percentage points). However, refugees staying in Poland reported much higher ratings when it comes to satisfaction with support for Ukraine by their host country (6.46 vs 4.27) as well as satisfaction with support for oneself (6.07 vs 5.66).

Multivariate analyses

Moving on to the second research question (RQ2), we are interested in explaining country differences by focussing on the sample composition in both countries. However, as shows, the Ukrainian refugees interviewed in Germany and Poland did not differ much in terms of respondents’ support for EU accession. Hence, we do not need to run any sophisticated model testing for composition effects but consider the drivers of our independent variables in country-specific regression models instead.

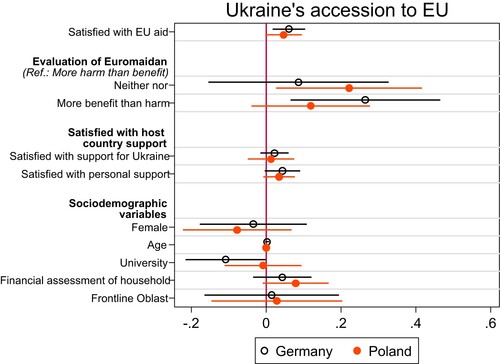

The estimation results of the linear regression model (by country) are presented in .

Figure 1. Predicting agreement to Ukraine’s accession to EU (OLS regression with 95% CI based on bootstrapped standard errors with 1,000 replications).

Let us first address the two variables intended to test the effect of utilitarian or identity-driven decisions. Looking at satisfaction with EU aid – our measure of cost-benefit calculations – a weak positive effect is found in both countries. If respondents were satisfied with EU aid to Ukraine, they were also more likely to agree that their country should join the EU. Regarding the influence of European identity, our analysis shows stronger effects, but these have very large confidence intervals. For respondents in Germany, the category ‘more benefit than harm' shows a significantly positive effect. If people thought that the past Euromaidan protests brought more benefit than harm, this also raised their support for joining the EU nowadays. This indicates that even during times of war, when direct cost-benefit considerations should prevail, pre-existing emotional attachment could still play a role, as seen with refugees interviewed in Germany. In Poland, however, we find such a positive effect only for the middle category ‘neither harm nor benefit.'

Regarding the remaining variables in the model, most factors did not yield significant effects. In both countries, respondents’ satisfaction with bilateral support for Ukraine and the assistance they personally received from their host country were positively associated with perceptions of Ukraine’s accession to the EU, even though the effects were minor and sometimes insignificant. Thus, satisfaction with a specific country's assistance may enhance the overall image of the EU and vice versa.

Discussion

This research note delivers first insights on a hard-to-reach sample of Ukrainian refugees and their evaluation of a potential EU membership since the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. While previous academic publications focussed on people still residing in Ukraine, our work allows for the first time an examination of the, in this respect, understudied group of Ukrainian refugees. Since this group of people constitutes a significant portion of the Ukrainian population, examining their attitudes is not only relevant with respect to the academic discourse, but also as doing so gives Ukrainian refugees in two EU countries a voice – a voice that has so far remained unheard.

Based on original survey data collected in Germany and Poland from April to May 2022, our research highlights that a majority of interviewed Ukrainian refugees supported their country's aspiration to join the EU. During times of war, citizens in EU candidate states tend to maintain strong backing for EU integration. This could be attributed to EU membership being perceived as one – or perhaps the only – viable path to escape Russia's influence. The focus during war shifts towards the survival and security of one's own country. However, the validity of these initial assessments remains speculative, as further research is needed to delve deeper into these dynamics. Moreover, the significance of identity and utilitarian-driven decisions underscores the complexity of public opinion. While pragmatic considerations were crucial for the refugees we interviewed, identity-related factors also influenced their perspectives on international alliances and integration.

Our research note does not come without flaws. First, we only surveyed people in two EU countries, which means we cannot make any statements about the attitudes of Ukrainian refugees in general. However, as Poland and Germany are two countries that both host a large share of refugees, and yet are very different in other regards, our results provide valuable insights. More generally, relying on a non-probability sample means that the reported distributions cannot be generalized to the target population in the two countries under examination. Furthermore, the survey did not include a wide array of value and attitudinal questions, limiting the potential of specification in our empirical models. In addition to specific limitations arising from our chosen methodology, our project is also subject to broader issues affecting the data and analysis of refugee surveys in general. One significant concern is the potential presence of self-selection bias, as traumatized individuals may be less inclined to participate in survey projects. Furthermore, future studies should explore the evolution of support for EU membership over time. These studies should ideally employ probability-based sampling methods, include refugees across a greater number of host countries, and gather more localized data to uncover nuanced levels of support for potential EU membership.

online appendix.docx

Download MS Word (576.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Please note that, throughout this paper, we use the term ‘refugee' in literal way referring to individuals who seek refuge in another country irrespective of their legal status.

2 The Orange revolution took place in Ukraine in late November 2004 to January 2005, as a response to an alleged rigging of the presidential election in favour of the pro-Russian candidate Viktor Yanukovych. The revolution was successful in annulling the elections and prompting their repetition.

3 In the Luhansk oblast, for instance, the pro-Western population was on average younger, more tolerant toward homosexuality and higher educated as opposed to a group of older, less educated, intolerant people who fell they belong to Russia (Gentile Citation2015).

4 Despite this difference, one needs to mention that the general level of education among people fleeing from Ukraine is much higher compared to the national average in Ukraine from 2019 (Kohlenberger et al. Citation2022).

5 In contrast, a survey conducted by the DeZIM Institute in February/March 2022 provides more positive figures, according to which more than 80% of all respondents in Germany in June 2022 supported the admission of refugees from Ukraine into the country.

6 In addition, we checked whether the respondents are generally in favour of simply joining any Western alliance, or whether the EU has a special status here. For this purpose, we compared the EU approval rates in the two countries with the approval rates for NATO membership. We found that, on average, respondents in both countries would also endorse joining NATO, but that their support for the EU was even higher.

References

- Baker, R., et al. 2013a. Non-Probability Sampling: Report of the AAPOR Task Force on Non-probability Sampling. AAPOR. Available at: https://www.aapor.org/Education-Resources/Reports/Non-Probability-Sampling.aspx (accessed: 26 October 2019).

- Baker, R., et al. 2013b. “Summary Report of the AAPOR Task Force on Non-Probability Sampling.” Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology 1 (2): 90–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/jssam/smt008.

- Bird, N., and N. Noumon. 2022. Europe Could Do Even More to Support Ukrainian Refugees. Greater integration into economies and labor markets would benefit Europe and refugees. In: IMFBlog. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/12/15/europe-could-do-even-more-to-support-ukrainian-refugees (accessed: 10 September 2023).

- Boomgaarden, H. G., et al. 2011. “Mapping EU Attitudes: Conceptual and Empirical Dimensions of Euroscepticism and EU Support.” European Union Politics 12 (2): 241–266. doi:10.1177/1465116510395411

- Bosse, G. 2022. “Values, Rights, and Changing Interests: The EU’s Response to the War Against Ukraine and the Responsibility to Protect Europeans.” Contemporary Security Policy 43 (3): 531–546. doi:10.1080/13523260.2022.2099713

- Botelho, V., and H. Hägele. 2023. Integrating Ukrainian refugees into the euro area labour market. In: The ECB Blog. Available at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/blog/date/2023/html/ecb.blog.230301~3bb24371c8.en.html (accessed: 10 September 2023).

- Brücker, H., et al. 2022. Geflüchtete aus der Ukraine in Deutschland: Flucht, Ankunft und Leben. Report, Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung. Wiesbaden, Deutschland.

- Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat (BMI). 2022. Geflüchtete aus der Ukraine. Available at: https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/veroeffentlichungen/nachrichten/2022/umfrage-ukraine-fluechtlinge.pdf.

- Cornesse, C., et al. 2020. “A Review of Conceptual Approaches and Empirical Evidence on Probability and Nonprobability Sample Survey Research.” Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology 8 (1): 4–36. doi:10.1093/jssam/smz041

- Doyle, O., and J. Fidrmuc. 2006. “Who Favors Enlargement?: Determinants of Support for EU Membership in the Candidate Countries’ Referenda.” European Journal of Political Economy 22 (2): 520–543. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2005.09.008

- Elgün, Ö, and E. R. Tillman. 2007. “Exposure to European Union Policies and Support for Membership in the Candidate Countries.” Political Research Quarterly 60 (3): 391–400. doi:10.1177/1065912907305684

- Emmer, M., C. Richter, and M. Kunst. 2016. Flucht 2.0: Mediennutzung durch Flüchtlinge vor, während und nach der Flucht. Institut für Publizistik- und Kommunikationswissenschaft, Freie Universität Berlin. Available at: https://www.polsoz.fu-berlin.de/kommwiss/arbeitsstellen/internationale_kommunikation/Media/Flucht-2_0.pdf.

- Ersanilli, E., and M. van der Gaag. 2020. Mobilise Data Report: Online Surveys. Wave 1. SocArXiv [Preprint].

- Eurobarometer. 2022. EU’s Response to the War in Ukraine. Available at: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2772 (accessed: 10 September 2023).

- Fligstein, N., A. Polyakova, and W. Sandholtz. 2012. “European Integration, Nationalism and European Identity.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 50(s1): 106–122. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2011.02230.x

- Forschungsgruppe Wahlen. 2022. Politbarometer April II 2022: Mehrheit unterstützt Lieferung schwerer Waffen an Ukraine – In der Krise: Viel Zustimmung für Baerbock und Habeck. Available at: https://www.forschungsgruppe.de/Umfragen/Politbarometer/Archiv/Politbarometer_2022/April_II_2022/ (accessed: 10 September 2023).

- Gabel, M. 1998. “Public Support for European Integration: An Empirical Test of Five Theories.” The Journal of Politics 60 (2): 333–354. doi:10.2307/2647912

- Gabel, M., and G. D. Whitten. 1997. “Economic Conditions, Economic Perceptions, and Public Support for European Integration.” Political Behavior 19 (1): 81–96. doi:10.1023/A:1024801923824

- Genschel, P., L. Leek, and J. Weyns. 2023. “War and Integration. The Russian Attack on Ukraine and the Institutional Development of the EU.” Journal of European Integration 45 (3): 343–360. doi:10.1080/07036337.2023.2183397

- Gentile, M. 2015. “West Oriented in the East-Oriented Donbas: A Political Stratigraphy of Geopolitical Identity in Luhansk, Ukraine.” Post-Soviet Affairs 31 (3): 201–223. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2014.995410

- Gherghina, S. 2010. “Unraveling Romance: An Assessment of Candidate Countries’ Support for the EU.” Comparative European Politics 8 (4): 444–467. doi:10.1057/cep.2009.6

- Hakhverdian, A., E. Van Elsas, W. Van der Brug, and T. Kuhn. 2013. “Euroscepticism and Education: A Longitudinal Study of 12 EU Member States, 1973–2010.” European Union Politics 14 (4): 522–541. doi:10.1177/1465116513489779

- Hargrave, K., K. Homel, and L. Drazanova. 2023. Public narratives and attitudes towards refugees and other migrants: Poland country profile.

- Haug, S., S. Lochner, and D. Huber. 2019. “Methodological Aspects of a Quantitative and Qualitative Survey of Asylum Seekers in Germany – A Field Report.” Methods, Data, Analyses 13 (2): 321–340.

- Höltmann, G., S. Hutter, and C. Rößler-Prokhorenko. 2022. Solidarität und Protest in der Zeitenwende: Reaktionen der Zivilgesellschaft auf den Ukraine-Krieg. Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, Berlin. Available at: https://bibliothek.wzb.eu/pdf/2022/zz22-601.pdf (accessed: 10 September 2023).

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2009. “A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From PermissiveConsensus to Constraining Dissensus.” British Journal of Political Science 39 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1017/S0007123408000409

- International Republican Institute (2023) Eighth Annual Ukrainian Municipal Survey. April–May 2023. Available at: https://www.iri.org/resources/eighth-annual-ukrainian-municipal-survey-april-may-2023/ (accessed: 10 September 2023).

- IOM. 2023. Ukraine & Neighbouring Countries 2022–2024: 2 Years of Response. Available at: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/documents/2024-02/iom_ukraine_neighbouring_countries_2022-2024_2_years_of_response.pdf.

- Jann, B. 2005. “Making Regression Tables from Stored Estimates.” The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata 5 (3): 288–308. doi:10.1177/1536867X0500500302

- Jann, B. 2007. “Making Regression Tables Simplified.” The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata 7 (2): 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0700700207.

- Jann, B. 2014. “Plotting Regression Coefficients and Other Estimates.” The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata 14 (4): 708–737. doi:10.1177/1536867X1401400402

- Katsanidou, A., and Q. Mayne. 2024. “Is There a Geography of Euroscepticism among the Winners and Losers of Globalization?” Journal of European Public Policy 31 (6): 1693–1718.

- Kemp, S. 2022. Digital 2022: Ukraine. Available at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-ukraine (accessed: 10 September 2023).

- Kohlenberger, J., et al. 2022. What the Self-Selection of Ukrainian Refugees Means for Support in Host Countries. In: EUROPP – European Politics and Policy. Available at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2022/09/07/what-the-self-selection-of-ukrainian-refugees-means-for-support-in-host-countries/ (accessed: 11 September 2023).

- Kulyk, V. 2016. “National Identity in Ukraine: Impact of Euromaidan and the War.” Europe-Asia Studies 68 (4): 588–608. doi:10.1080/09668136.2016.1174980

- The Kyiv Independent News Desk. 2023. Poll: 67% of Ukrainians are Against Any Compromises with Russia; 82% say Putin New Hitler. In: The Kyiv Independent. Available at: https://kyivindependent.com/over-67-of-ukrainians-say-no-compromises-with-russia-over-80-say-putin-new-hitler-poll-shows/ (accessed: 10 September 2023).

- Mayer, S. J., et al. 2022. Reaktionen auf den Ukraine-Krieg. Eine Schnellbefragung des DeZIM.panels. DeZIM Institut. Available at: https://www.dezim-institut.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Demo_FIS/publikation_pdf/FA-5328.pdf (accessed: 10 September 2023).

- Mayne, Q., and A. Katsanidou. 2023. “Subnational Economic Conditions and the Changing Geography of Mass Euroscepticism: A Longitudinal Analysis.” European Journal of Political Research 62 (3): 742–760. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12528

- Moise, A. D., J. Dennison, and H. Kriesi. 2023. European Attitudes to Refugees After the Russian Invasion of Ukraine, 1–26. West European Politics.

- NDI. 2023. Opportunities and Challenges facing Ukraine’s Democratic Transition. Available at: https://www.ndi.org/sites/default/files/May%202023_wartime%20survey_Public%20version_%20Eng.pdf (accessed: 4 October 2023).

- Onuch, O. 2014. “The Maidan and Beyond: Who Were the Protesters?” Journal of Democracy 25 (3): 44–51. doi:10.1353/jod.2014.0045

- Panchenko, T. 2022. “Prospects for Integration of Ukrainian Refugees Into the German Labor Market: Results of the IFO Online Survey.” CESifo Forum 23 (04): 67–75. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/263868.

- Pop-Eleches, G., and G. B. Robertson. 2018. “Identity and Political Preferences in Ukraine – Before and After the Euromaidan.” Post-Soviet Affairs 34(2-3): 107–118. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2018.1452181

- Pötzschke, S., et al. 2023. A Guideline on How to Recruit Respondents for Online Surveys Using Facebook and Instagram: Using Hard-to-Reach Health Workers as an Example. Survey Guidelines [Preprint]. https://doi.org/10.15465/gesis-sg_en_045

- Pötzschke, S., B. Weiß, A. Hebel, and J. Piepenburg. 2022. Online survey of Ukrainian refugees (OSUR). https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/4ZYWX.

- Pryke, S. 2020. “National and European Identity.” National Identities 22 (1): 91–105. doi:10.1080/14608944.2019.1590808

- Reinl, A. K., and D. Braun. 2023. “Who Holds the Union Together? Citizens’ Preferences for European Union Cohesion in Challenging Times.” European Union Politics 24 (2): 390–409. doi:10.1177/14651165221138000

- Reinl, A. K., and G. Evans. 2021. “The Brexit learning effect? Brexit negotiations and attitudes towards leaving the EU beyond the UK.” Political Research Exchange 3 (1): 1932533.

- Steiner, N. D., R. Berlinschi, E. Farvaque, J. Fidrmuc, P. Harms, A. Mihailov, M. Neugart, and P. Stanek. 2023. “Rallying Around the EU Flag: Russia's Invasion of Ukraine and Attitudes Toward European Integration.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 61(2): 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13449.

- Sviatnenko, S., and A. Vinogradov. 2014. “Euromaidan Values from a Comparative Perspective.” Social, Health, and Communication Studies Journal 1 (1): 41–61. Available at: https://journals.macewan.ca/shcsjournal/article/view/251.

- Toshkov, D., H. Mazepus, and A. Dimitrova. 2023. Framing International Cooperation: Citizen Support for Cooperation with the European Union in Eastern Europe. Comparative European Politics [Preprint].

- UNHCR. 2024. Operational Data Portal: Ukraine Refugee Situation. Available at: https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine (accessed: 21 June 2024).

- Van Klingeren, M., H. G. Boomgaarden, and C. H. De Vreese. 2013. “Going Soft or Staying Soft: Have Identity Factors Become More Important Than Economic Rationale When Explaining Euroscepticism?” Journal of European Integration 35 (6): 689–704. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.719506

- Vasilopoulou, S., and L. Talving. 2020. “Poor Versus Rich Countries: A gap in Public Attitudes Towards Fiscal Solidarity in the EU.” West European Politics 43 (4): 919–943. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1641781

- White, S., J. Korosteleva, and I. Mcallister. 2008. “A Wider Europe? The View from Russia, Belarus and Ukraine*.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 46 (2): 219–241. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00775.x

- White, S., I. McAllister, and V. Feklyunina. 2010. “Belarus, Ukraine and Russia: East or West?” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 12 (3): 344–367. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856X.2010.00410.x

- Yakymenko, Y., and M. Pashkov. 2018. Ukraine on the Path to the EU: Citizens’ Opinions and Hopes. Available at: http://www.tepsa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Ukrainian_brief_finalversion.pdf (accessed: 10 September 2023).

- Zelinska, O. 2017. “Ukrainian Euromaidan Protest: Dynamics, Causes, and Aftermath.” Sociology Compass 11 (9): e12502. doi:10.1111/soc4.12502