ABSTRACT

Constituency service is a crucial concept for understanding the nature and intensity of the links between representatives and their constituents. However, studies have been inconsistent about the meaning of constituency service, its causes and consequences, justifying a systematic analysis of where we stand in this field of studies. This article conducts a scoping literature review of 198 studies on constituency service published between 1975 and 2021. It aims to answer the following questions: how has constituency service been defined? Which research designs are commonly used when studying it? And what are its driving factors and political effects? These questions are answered using a dataset that codes each study along several dimensions tapping into conceptualization, research design, explanatory factors, and effects. The analysis shows that this field of research has grown significantly over the last decade, covering more activities (inside and outside the geographic constituency) and countries, with increased methodological pluralism. This review makes an original contribution by charting the main trends in the study of constituency service, advancing a dynamic conceptualization of constituency service, and opening up new avenues for research on the subject.

Introduction

The link between representatives and constituents is a vital part of the life of any regime and particularly so in democracies. It can be studied by looking at either different components of political representation and/or responsiveness (Dovi Citation2015; Eulau and Karps Citation1977) or specifically at constituency service, which is the primary means used to respond to constituents’ needs (Eulau and Karps Citation1977).

Earlier studies defined constituency service as a nonpartisan and non-programmatic effort to advance and defend the particularistic interests of the constituents (Cain, Ferejohn, and Fiorina Citation1984), and conceived the ‘constituency’ as a set of concentric circles radiating from a personal (centre) to a geographic (outer) circle (Fenno Citation1978). Variations in the legislator’s behaviour were expected to depend on the priority given to links with the personal, primary, re-election or geographic constituency (Fenno Citation1978).

Research on constituency service is both rich and complex. First, the meaning and range of activities measured in the studies vary widely. While initial studies highlighted activities performed in the district, more studies are now observing constituency efforts in parliament and the digital sphere (Arter Citation2018; Crisp and Simoneau Citation2017; Gervais and Wilson Citation2019). Second, a constituency can mean different things, and legislators may have different incentives to cater to the interest of personal, primary, re-election or geographic constituencies (Fenno Citation1978). Third, the findings on the nature, drivers and consequences of constituency are highly context-dependent and are based predominantly on the observation of western democratic countries – initially the US and the UK, and later other European countries (Arter Citation2018). Although existing studies have increased our knowledge of constituency service, the diversity of definitions and activities as well as the unclear results make generalizations difficult. A more systematic analysis of where we stand in this field of studies is therefore crucial both to refine the concept (i.e. concept formation) and advance existing research agendas (i.e. theory building).

This article conducts a scoping literature review (SLR) of 198 studies published between 1975 and 2021 to document the main conceptual and empirical trends shaping the study of constituency service. This SLR aims to answer the following questions: how has constituency service been defined? Which research designs are commonly used when studying it? And what are its driving factors and political effects? To answer these questions, this study draws on a dataset that codes each considered study across dimensions such as conceptualization and measurement, research design, explanatory factors, and effects.

The analysis shows that studies on constituency service have grown significantly over the last decade, covering more activities and more countries with increased methodological pluralism. Nevertheless, work on the subject is still largely characterized by quantitative case studies focusing on the Global North. In terms of the dominant explanatory accounts, at the macro-level, most studies emphasize the role played by political institutions and district characteristics to explain variations in constituency service. At the MP-level, political career, election prospects, socio-demographics and personal motivation are the dominant explanations. At the citizen-level, the constituents’ socio-demographic profile, the expectations in relation to MPs’ role orientation, among others, seem to trigger both different expectations and experiences of constituency service provision. The review also shows that only a few studies investigate the consequences of constituency service, namely by assessing its influence on MPs’ electoral performance or on citizens’ evaluation of (or trust in) MPs. Building on this overview, we develop a conceptual approach for the study of constituency service comprising multiple indicators for measuring its key dimensions (service, representation/responsiveness and distribution/allocation) across different arenas (district, parliament and digital sphere). Then, we advance a set of topics that can shape future innovative research in both theoretical and methodological terms. Overall, this review makes an original contribution by charting the main trends in the study of constituency service, advancing a dynamic conceptualization of constituency service, and opening up new avenues for research on the subject. This not only has academic value, as exemplified by the growth in systematic reviews in political science, but also ‘real life’ relevance since it illuminates the connections between politicians and their constituents.

This study starts with an overview of constituency service to lay the ground for the systematic review. We then describe the protocol used in the design and implementation of the SLR, and discuss the challenges and limitations of this exercise. The main results of the SLR are set out in three sections: the first charts the temporal, geographic and methodological trends in the study of constituency service; the second identifies its key explanatory factors at the macro and micro level, and the third outlines its consequences. We conclude by advancing a conceptual framework for studying constituency service, proposing themes for a future research agenda, and summarizing the main findings and takeaways.

The puzzle of constituency service

Studies on constituency service span over four decades but many of the questions raised remain unresolved. The first question concerns the meaning(s) of constituency and constituency service. Legislators may perceive a constituency as a nest of circles that includes a geographic constituency with boundaries stipulated by law; a re-election constituency composed of people who elected the legislator; a primary constituency comprising his/her strongest supporters, and a personal constituency composed of private networks (Fenno Citation1978). However, most research underplays this heterogeneity by focusing mainly on the geographic and electoral constituencies. The meanings of constituency service are also diverse. Eulau and Karps (Citation1977) define it as service responsiveness, i.e. personalized and particularized forms of casework whereby legislators signal commitment to their constituents, distinguishing it from policy (representation of constituents’ policy interests), allocation (pork barrel) and symbolic (gestures that generate trust and continue support) responsiveness. Fenno (Citation1978) definition contemplates casework in the district (at home) but also some kind of reporting. The legislator home-style combines three ingredients seen as crucial for building trust and electoral support: ‘allocating resources, presenting themselves, and explaining their Washington activity’ (Citation1978, 50). Some elements of this conceptualization evoke what others have called personal vote, that is ‘that portion of a candidate’s electoral support which originates in his or her personal qualities, qualifications, activities, and record’ (Cain, Ferejohn, and Fiorina Citation1984, 111). Personal vote means using constituency service as a way to build an electoral connection rather than the vote itself.

Due to the various conceptualizations of constituency service, a plethora of activities are also associated to it. Fenno's (Citation1978, 101) distinction between casework, when the service benefits a few individuals, and project assistance, when a larger number of individuals benefit, exemplifies extant diversity. Hence, a first and more significant set of studies has investigated legislators’ casework activities, e.g. the time spent in their district, the meetings held with constituents, or their participation in political and social events in the district, inter alia (André and Depauw Citation2013; Norris Citation1997). A second set of studies has analysed project assistance by exploring how politicians channel funds and development projects to key groups or areas within their constituency (Bussell Citation2019; Mayhew Citation1974; Taylor Citation1992). However, this division is far from clear-cut. While some studies treat allocation responsiveness (i.e. project assistance or pork barrel) as a separate phenomenon (Eulau and Karps Citation1977) and discuss it within theories of distributive politics (Golden and Min Citation2013), others relate it more explicitly to constituency service (Ciftci and Yildirim Citation2019; Ellickson and Whistler Citation2001). The picture becomes even more blurred as more activities are included in the list. Indeed, a growing number of studies are investigating how legislators represent the district’s interests in parliament – via questions, bills and speeches (Dockendorff Citation2020; Martin Citation2011, Citation2013; Russo Citation2021); and how legislators use social media to develop digital home styles oriented towards specific demographic constituencies (Gervais and Wilson Citation2019).

A second question concerns the causes of constituency service. MPs’ decision to embrace his/her role as ‘good constituency member’ (Searing Citation1985) vis-à-vis other duties depends on multiple factors. Electoral motivations (re-election and re-selection) are important, as are electoral institutions, because candidate-centred electoral systems offer more incentives for constituency-focused behaviour than party-centred systems (Cain, Ferejohn, and Fiorina Citation1984; Crisp and Simoneau Citation2017). Additionally, MPs’ intrinsic motivations and perceptions (Giger, Lanz, and De Vries Citation2020; Yildirim Citation2020), their biographic ties to the district (Dockendorff Citation2020; Russo Citation2011, Citation2021) and the characteristics of the constituents (Habel and Birch Citation2019; Hayes and Bishin Citation2024; Landgrave Citation2021) may affect their decisions. Therefore, a complex set of factors at the macro and micro level constrain MPs choices, making it hard to disentangle which effects are the most relevant, and in which contexts. The final question, on the consequences of constituency service, is still understudied. The few existing studies are eclectic in that they survey the effects on re-election (Studlar and McAllister Citation1996), citizens’ evaluations of MPs (Sulkin, Testa, and Usry Citation2015) or the durability of authoritarian regimes (Distelhorst and Hou Citation2017; Ong Citation2015), but the findings are contextually-bounded. Therefore, a SLR can help clarify some of the conceptual and empirical challenges shaping the study of constituency service and, at the same time, contribute to both concept formation and theory-building.

Methods and data

Over the past decade, systematic reviews have gained prominence in political science literature, and their potential for synthesizing evidence, signalling gaps, and clarifying concepts is increasingly recognized (e.g. Bandau Citation2022; Cancela and Geys Citation2016; Dacombe Citation2018; Khan, Krishnan, and Dhir Citation2021; Lisi, Oliveira, and Loureiro Citation2023; Miljand Citation2020). The type of systematic reviews (systematic or scoping reviews) varies depending on the goals and the synthesis method in use. Systematic literature reviews are applied when the researcher seeks to identify relevant research on a precise question or hypothesis, whereas scoping literature reviews (SLR) are more open-ended and useful for identifying the types of available evidence in a given field, clarifying concepts and definitions, identifying gaps and factors associated with concepts, and summarizing findings (Munn et al. Citation2018).

What is crucial is that both systematic and scope reviews involve a protocol defining the question(s) or topic(s) of interest and setting the criteria for the selection and further inclusion/exclusion of studies (Liberati et al. Citation2009; Miljand Citation2020). In a subsequent stage, data is collected, processed and analysed either quantitatively (e.g. through meta-analysis) or qualitatively, involving the critical interpretation and thematic analysis of the studies under consideration (Liberati et al. Citation2009; Miljand Citation2020). These procedures ensure transparency, comprehensiveness, and reproducibility, unlike the ‘traditional’ type of literature review (Liberati et al. Citation2009; Miljand Citation2020).

In this study, we opt for a scoping review since constituency service is defined and operationalized differently across studies, and emerging evidence remains unclear. Therefore, mapping the field is a necessary step before more structured systematic reviews can be performed.

Search and selection process

The implementation of the SLR draws explicitly from the widely used PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Protocol, which sets clear criteria for selecting and screening studies (Liberati et al. Citation2009). To select the studies, we used two electronic repositories – Scopus and Web of Science – to avoid a possible bias in the database choice that could yield differing findings (Wanyama, McQuaid, and Kittler Citation2022). Both are commonly used in systematic reviews and allow for an exhaustive search by keywords of interest.

The definition of keywords relied on early works on political representation and constituency service (Cain, Ferejohn, and Fiorina Citation1984, Citation1987; Eulau and Karps Citation1977; Fenno Citation1978; Searing Citation1985), and more recent research and state of the field papers (Arter Citation2018; Bussell Citation2019; Crisp and Simoneau Citation2017; Russo Citation2021). Given the controversy on what counts as constituency service, we opted to use wide-encompassing keywords that would hint at constituency service or at representative-constituent relations. We purposely avoided terms that could associate constituency service with concrete tasks so that the meanings and findings could emerge inductively and not be pre-determined a priori. Simply put, we used keywords as a kind of ‘fishing net’ with which to ‘capture’ the prevailing meanings and findings. We devised a fairly exhaustive list of keywordsFootnote1 which were then systematically searched for in both electronic repositories: ‘constituency service’, ‘service responsiveness’, ‘constituency work’, ‘constituency focus’, ‘constituency effort’, ‘constituency representation’, ‘constituency preferences’, ‘constituency influence’, ‘constituency diversity’, ‘constituent preferences’, ‘constituent-representative’, ‘geographic representation’ ‘home style’, ‘district focus’, ‘political linkage’ and ‘local representation’.

The search in the electronic repositories covered studies published until December 2021 regardless of the disciplinary field; and considered whether the selected keywords were mentioned in an article’s abstract, title or keywords. We relied exclusively on English-language academic articles, which means that studies published in other languages and available through other sources and other formats were excluded (books, book chapters, conference papers, working papers and book reviews). This decision is in line with most systematic review studies (Khan, Krishnan, and Dhir Citation2021; Lisi, Oliveira, and Loureiro Citation2023; Tucker Citation2002).

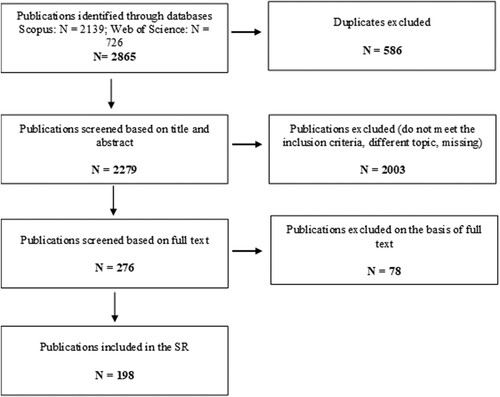

displays all stages from the selection of studies to screening and final sample. The initial search of all keywords resulted in 2865 articles: 2139 gathered through Scopus and 726 through Web of Science. In the first two stages, duplicates were excluded (N = 586), as well as studies that upon closer examination, were found not to be about constituency service (N = 2003). To give just some examples, the keywords ‘constituency preferences’, ‘constituency influence’ and ‘constituent preferences’ were included in the initial sample of numerous studies about how constituents influence legislators’ behaviour in parliament (particularly in the US); and about the congruency between representatives and their constituents. While these topics tap into the connections between representatives and their constituents, they are not about constituency service. Likewise, some keywords like ‘local representation’ or ‘geographic representation’ were identified in numerous studies in other disciplinary fields unrelated to politics. While most decisions concerning the inclusion/exclusion of articles were straightforward, several validation exercises were made to ensure that the correct decisions were taken at this stage, including a third-party screening of a sample of excluded studies (over 700 studies), and reading paper in full when the abstract was not enough.

In the following stage, from a sample narrowed down to 276 studies, we screened the full text of the articles, and excluded 78 articles that did not focus on constituency service. This was the case, for example, of some studies that mentioned constituency service briefly in the text but did not define it or empirically assess it. This reduced the final sample of the SLR to 198 studies. The authors coded between 24 and 64 articles each, utilizing a codebook that was iteratively constructed (see codebook in the supplementary material). The preliminary literature review conducted to identify the keywords helped elaborate a starting codebook. It informed the definition of initial dimensions and categories to map the goals/questions, the methodology, the meanings, causes and consequences of constituency service in each study. As the readings progressed, the initial coding scheme was enhanced with the inclusion of new categories, aided by regular meetings, double-checking procedures, and third-party validation. Therefore, the final codebook portrays the richness and diversity of extant approaches in the field.

Limitations

Before proceeding to the findings, we must acknowledge the study’s limitations. First, while SLR protocols ensure more transparency and rigour vis-à-vis ‘traditional’ literature reviews, they may also be problematic because studies are included/excluded on the basis of titles, abstracts and keywords. This means that we might have accidentally missed studies investigating phenomena related to constituency service that did not mention any of the selected keywords in the title, abstract or keywords. While our rationale for selecting keywords sought to mitigate this risk, we cannot disregard the possibility of accidental exclusions and their potential impact on some of our results. Secondly, the fact that constituency service is a fuzzy concept is an additional challenge: it can cover a broad range of activities and scholars give it different names. This proved challenging when it came to devising a list of keywords that would capture ‘all studies’ on the topic; we eventually opted to include keywords that were broad enough to cover the different terms and phenomena associated to constituency service, while avoiding more specific keywords such as ‘pork barrel’ or ‘personal vote’, among others.

We faced an additional hurdle as some terms are not always linked to constituency service and may be discussed within different streams in the literature. For example, pork barrel has been defined as a separate form of representation (Eulau and Karps Citation1977) and discussed within theories of distributive politics, while ‘personal vote’ is often studied in electoral and candidate selection studies (Shugart, Valdini, and Suominen Citation2005). Nevertheless, our strategy did identify studies that use pork barrel and personal vote as forms of constituency service – which means that our ‘open-ended’ approach yielded interesting results. Another approach would have been to include keywords for all possible phenomena related to constituency service; we ultimately decided against this as it would be difficult to ensure the inclusion of all phenomena and failing to do so would bias the analysis. The final sample allows for a diverse and unbiased sample and the outputs of this exercise can be used by future research to counter this limitation. The results displayed in the following sections should be interpreted with caution considering the limitations outlined above.

Constituency service: mapping the field

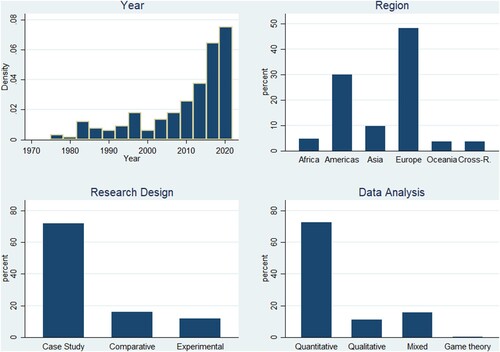

This section offers an overview of the studies published by year, region, research design and type of data analysis. As shown in , the number of published studies on constituency service was relatively low throughout the 1980s and 1990s but started to increase in the 2000s. The most visible upward inflection occurred in the past decade with 67% of the studies being published between 2010 and 2021. This attests to the new interest in constituency service within the discipline.

Figure 2. Constituency service: year, region, research design and type of data analysis. Source: Authors' elaboration.

Most studies (nearly 77%) centre on cases from Europe and America. The focus was initially primarily on the UK and US as their candidate-centred rules were conducive to constituency service, but the field has expanded to include institutionally diverse countries in Europe (Germany, Netherlands, Finland, Norway and the Netherlands) and the Americas (Canada and Latin American countries). In contrast, only a handful of studies have focused on countries in Asia (e.g. Japan, Malaysia and South Korea), Africa (e.g. Ghana, Uganda, South Africa, Kenya, Zambia) and Oceania (Australia and New Zealand), while cross-regional comparisons are scarce (7 out of 198). For example, Struthers (Citation2018) investigated green parties’ attention to local issues in two countries with different electoral systems: the UK, with a first-past-the-post system (FPTP), and New Zealand, with a proportional representation system (PR). Likewise, Heitshusen, Young, and Wood (Citation2005) examined the constituency focus of MPs in five countries – Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, and the UK – with varying electoral rules, ranging from preferential voting, to FPTP and closed-list PR. As explained later on, electoral systems are key institutional predictors of constituency service.

In terms of research design, the field has been characterized by single case studies, while comparative, and experimental designs are both less common and more recent. Lastly, around 68% (n = 134) of the studies employ quantitative methods, 11% (n = 21) mobilize qualitative methods, and only 15% (n = 29) combine the two. Most studies use extremely rich and diverse data. Quantitative studies rely on elite and citizen surveys, parliamentary data (speeches, questions, motions and bills, etc.), and constituency funds for example, while qualitative studies rely on fieldwork, interviews with elites, and participant observation.

This initial snapshot reveals that knowledge on constituency service is mainly shaped by case studies using quantitative approaches and conducted in the Global North, predominantly in consolidated democracies. Later on, we discuss how employing qualitative approaches, and diversifying the geographic scope of the studies can help advance research on this topic.

The ‘meanings’ of constituency service

The meanings of constituency service were extracted from the definition provided in each study, and we assigned as many codes as necessary to fully characterize the different connotations. As mentioned in the methodological section, we drew on a preliminary literature review to create a starting codebook, and established a-priori meanings of constituency service to get the coding exercise going. Subsequently, other categories were added as the coding of each study progressed in an effort to accurately portray the definition in use. This coding exercise was not always straightforward as some studies used the term constituency service loosely or used other terms to refer to it. When the study lacked a clear theoretical definition, the coders drew on the empirical operationalization to extract the meaning.

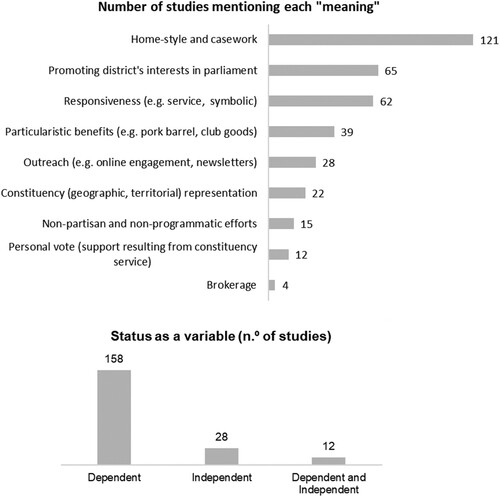

The constituency is treated as a geographic or electoral unit in most studies, with few looking into how constituency representation goes beyond geographic frontiers (Saalfeld Citation2011) and the socio-demographic diversity of the constituents (Habel and Birch Citation2019; Hayes and Bishin Citation2024). As for the meaning of constituency service, (upper graph) shows the most common categories (for the full list of ‘meanings’ see codebook, in the supplementary material). Since most studies display more than one meaning associated with constituency service – either by tackling different types of constituency-focused activities or by departing from broader definitions – the total count is higher than the number of studies considered.

In our sample, constituency service is equated primarily with casework and home-styles. Most studies try to understand how legislators behave in their district, be it from the time spent in (or number of visits to) their district or the set of activities they develop and type of constituents they encounter (André, Bradbury, and Depauw Citation2014; Norris Citation1996; Park Citation1988; Searing Citation1985). The second most common meaning refers to how MPs use parliamentary tools such as questions, bills, resolutions, or speeches to represent their geographic constituency. Contrary to studies on casework and home-styles, this is a more recent trend that builds on innovative methodologies of text analysis to investigate MPs’ representational focus. This is done by counting explicit geographic references to the constituency (Chiru Citation2018; Dockendorff Citation2020; Kartalis Citation2023; Martin Citation2011, Citation2013; Russo Citation2021) or by estimating the level of focus on topics that are of particular interest to the constituency (Borghetto, Santana-Pereira, and Freire Citation2020).

The third approach highlights different aspects of responsiveness. For Koop (Citation2012), for example, service responsiveness involves both service (efforts of representatives to assist constituents in dealing with government agencies) and allocative components (efforts to secure benefits from the government for their ridings). Bárcena Juárez and Kerevel's (Citation2021, 1387) notion of communicative responsiveness ‘indicates politicians’ openness to listen closely and understand constituent concerns before making any decision that might affect a polity’, whereas Taggart and Durant's (Citation1985, 490) symbolic responsiveness translates a diffuse ‘method of demonstrating to constituents that incumbents are fulfilling their representational role’. In all these definitions, there is a sense that representatives are bound to their constituents and must therefore act in their favour. The fourth approach perceives constituency service as a form of particularistic politics (e.g. pork barrel, allocation of club or private goods). This is present in Lindberg’s (Citation2010, 120) definition of constituency service as ‘the provision of club goods (…) or purely private goods’, and Lancaster's (Citation1986, 68) statement that ‘pork barrel politics is a particular type of constituency service’ that ‘benefits the representative's geographic constituency as a collective good’.

As can be seen in (upper graph), existing studies have also emphasized outreach activities (Baxter, Marcella, and O’Shea Citation2016; Jackson and Lilleker Citation2011; Neihouser Citation2023), constituency representation (Russo Citation2011, Citation2021; Searing Citation1985), and personal vote – i.e. relying on constituency service to build a personalized local support base (Middleton Citation2019). Finally, more than one ‘meaning’ of constituency service was found in several studies. For instance, Ellickson and Whistler (Citation2001) investigated the time that US state legislators spent on both casework and public resource allocation and showed that legislators have different incentives to engage in these activities. Likewise, Ciftci and Yildirim (Citation2019, 369) analysed whether Turkish legislators had distinct motives to carry out different kinds of constituency-oriented activities such as ‘ensuring the provision of benefits to a district, spending time to help constituents, pursuing public investments for an electoral district, or by asking constituency-centred parliamentary questions (PQs) on the floor’. These are but a few examples of broader conceptualizations of constituency service found in the sample (see Chiru’s Citation2018, among others).

When accounting for the theoretical position occupied by constituency service in existing studies, we find that it is mainly treated as a dependent (N = 158) rather than independent variable (N = 28) (, lower graph). This means that we know more about the repertoires of constituency service and its causes than about its consequences. Moreover, only a few studies treat constituency service as both the dependent and independent variable (N = 12). Building on this, the next two sections discuss the explanatory factors and the consequences of constituency service hitherto researched.

Explaining constituency service

To map explanations of constituency service, the main independent variables in each study were coded and subsequently clustered into major explanatory accounts. The same strategy used when coding the meanings of constituency service was applied, starting with a set of pre-established variables drawn from a preliminary literature review and another variable set included mid-coding process.

We start by discussing macro-level explanations and then proceed to MP-level and citizen-level explanations. Studies sometimes test these sets of explanations in parallel, but by analysing them separately, we can duly synthesize the findings on each explanatory account. Descriptive data is complemented in each section with discussions of the key findings, drawing on a selected sample of studies. Given space limits, only the most frequent explanations were covered but the full list of variables is shown in the codebook (see supplementary material).

Macro-level explanations

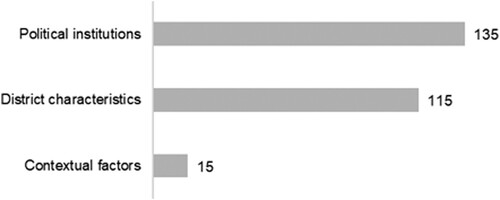

Macro-level explanations refer to institutional, structural and contextual characteristics that influence constituency service. As reveals, political institutions constitute the most frequent explanation of constituency service; being tested in more than half of the studies included in the SLR. Political institutions comprise electoral systems, political parties, party systems, parliament structure (bicameral or unicameral), system of government (federal or unitary), and candidate selection methods, among others. District characteristics arises as the second most-tested explanation, covering variables related to district’s demography (e.g. population size, age structure, and ethnicity), geography (e.g. rural/urban, centre/periphery), social cleavages and political culture, and electoral marginality. Finally, though less prevalent, contextual factors account for the impact of an economic crisis or election cycles on constituency service for example.

Figure 4. Macro-level explanations of constituency service. Source: Authors' elaboration.

Note: The graph displays the N, i.e. the number of studies.

Regarding the role played by political institutions, the main claim is that, as rules of the game, they influence MPs’ role orientation. The electoral system is the most researched political institution (tested in 43 studies); the expectation is that constituency service provision is higher where there are candidate-centred electoral rules (Single member districts-SMD/plurality/FPTP and open lists) as legislators’ re-selection and re-election prospects depend more on their ability to build a personalized support base in the district. In contrast, party-centred electoral rules (CLPR) offer no such incentives as MPs’ fate is tied to the party and their ability to win support within the party (Crisp and Simoneau Citation2017). However, findings have been inconsistent as far as these expectations are concerned.

Struthers (Citation2018), for example, found that Green Party MPs elected in nation-wide PR lists (New Zealand) devoted as much attention to local issues as Green Party MPs elected under the FPTP system (UK). Heitshusen, Young, and Wood (Citation2005) cross-national study shows that MPs elected in SMD, who are usually more dependent on local constituency support, are more likely to focus on the constituency than those elected in multi-member districts (MMD). However, the study also reveals that MPs elected in MMD (e.g. Ireland) feature a relatively high level of constituency focus. These studies show that there are incentives to focus attention on narrow local issues that are independent from the characteristics of electoral systems and that might be explained by individual and contextual factors.

Political parties and party systems are the second most researched political institutions (tested in 40 studies). Jackson and Lilleker (Citation2011) investigated patterns of Twitter usage to connect to voters in government and opposition parties in the UK, finding that the Labour and the Liberal Democrats used it for similar reasons: to better depict their views. Anagnoson's (Citation1991) study on New Zealand finds that MPs’ ties to local party organizations reinforce localism, that is, the need for MPs to remain locally active by attending local party meetings and holding surgeries.

A sample of studies explore the role of other political institutions but to a lesser extent (system of government, parliamentary systems, decentralization, etc.). Russell and Bradbury (Citation2007) find that the process of devolution in the UK after the transfer of competences from Westminster to local parliaments resulted in a general decrease in the amount of constituency casework done by Scottish and Welsh MPs, except in more competitive constituencies. Franks’ (Citation2007) analysis of the Canadian federal system contradicts the expectation that constituency service provision varies significantly across levels of government; members elected at different levels embrace it as part of their daily work. In both studies, constituency work is regarded by politicians, national and provincial/regional, as one of their most rewarding and satisfying functions, which to some extent explains the high level of dedication to constituents even in the presence of other political institutions that could potentially alleviate their workload (see also Bradbury Citation2007).

Regarding district characteristics, Dockendorff's (Citation2020) study of Chile tests, among other factors, whether the size of the population living in the constituency affects constituency focus in speeches, questions, resolutions and bills in parliament. The results go in the expected direction, i.e. the size of the constituency correlates negatively with all outcome variables, though only attaining statistical significance in half of the models. Martin’s (Citation2011) study on Ireland reveals that the central-periphery dynamic is crucial to understand the constituency focus of parliamentary questions. Specifically local questions were frequent from deputies from outside Dublin and as the distance from Dublin increased. Ellickson and Whistler (Citation2001, 563) add a different insight by showing that modalities of constituency service can be spatially diverse; while rural districts required time spent on casework, ‘urban districts required more pork’ (for different results see Costa and Poyet (Citation2016) study on France). Finally, Adler, Gent, and Overmeyer (Citation1998) find that the district’s electoral marginality influences the decision by the US House of the Representatives members to create an official homepage and to emphasize constituent casework in their official homepage.

Research has also considered, albeit to a lesser extent, a broad range of contextual variables – such as digitalization processes, election proximity, economic crisis, or countries’ different levels of welfare provision. For example, O’Leary (Citation2011) finds that the introduction of the internet has changed the way the Teachta Dála (TDs), or members of Ireland’s Dáil, interact with their constituents as it allows a larger number of citizens to engage with politicians, but it alters ‘the profile of constituents making contacts and the nature of their cases’ (342). Election proximity can also influence how MPs interact with their constituents, as seen by Baxter, Marcella, and O’Shea's (Citation2016) work on Scottish MPs’ use of Twitter and the impact of the proximity to the Scottish independence referendum. Finally, Kartalis’ (Citation2023) study on Greece reveals that economic performance is positive and significantly associated with tabling constituency-focused questions; however, this effect becomes less pronounced as MPs’ electoral vulnerability increases.

Macro-level explanations are undoubtedly crucial to understand constituency service, as MPs’ decisions are also formed on the basis of the ‘information’ received from the political, economic and cultural settings within which they operate. While most studies confirm macro-level effects, it is difficult to single out the most relevant factor as evidence emerges on specific cases studies and specific institutions. More cross-national studies are required to test (co)variation and whether some of these effects are generalizable.

MP-level explanations

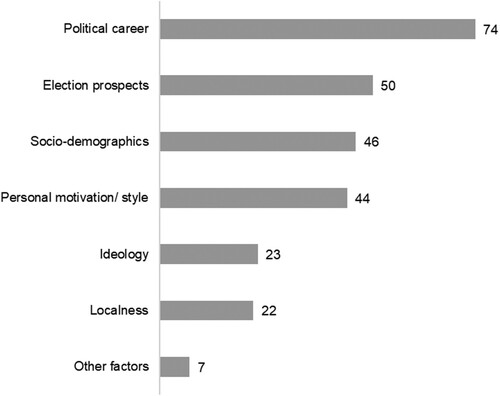

It is widely accepted that constituency service provision varies with MPs characteristics and displays those more frequently tested. It considers political career variables (e.g. seniority, incumbency, cabinet, legislative or party career), election prospects (e.g. electoral marginality/vulnerability/safety, expectations of win/defeat), socio-demographics (e.g. profession, class, education, age/cohort, gender, ethnicity), personal motivation/style (e.g. interest, motivation, ambition, self-expressed role orientation), localness (born, resident, or politician in the district)Footnote2 and ideology (party identification, policy preferences) and other factors.

Figure 5. MP-level explanations of constituency service. Source: Authors' elaboration.

Note: The graph displays the N, i.e. the number of studies.

Starting with political career variables, seniority emerges as crucial explanation affecting legislators’ decision to engage in constituency-oriented activities. The underlying assumption is that newcomers in parliament need ‘to reinforce their credibility by championing the interests of the constituency’ (Russo Citation2011, 294). In contrast, senior MPs – usually high-ranking politicians – can trade constituency work against other tasks that would favour career advancement (Fenno Citation1978). Thus, in the party-controlled assembly of Chile, first-term legislators are more likely to use the parliamentary floor to cater to district interests (Dockendorff Citation2020) and, in Turkey, junior legislators are more likely to focus on local issues during televised debates than their senior counterparts (Yildirim Citation2020). Studies have also tested the impact of incumbency as, in principle, it generates advantages in terms of access to resources (experience, expertise, and visibility) and channels through which MPs can publicize their activities. Nevertheless, the findings have not been conclusive. For instance, Neihouser (Citation2023) shows that the impact of incumbency on French MPs’ digital communication style depends on what MPs chose as their representational role. MPs following a ‘constituency focus model’ engage less with online communication tools; whereas those following a ‘trustee model’, and representing nation-wide interests, invest more in national media and personal branding, resulting in increased social media activity. Papp’s (Citation2015) analysis of Hungary’s party-centred parliament finds that although incumbents run more personalized and constituency-focused campaigns, this effect does not hold after controlling for their partisanship.

Election prospects, the second most common MP-level factor, is classically presented as the primary reason for legislators’ engagement in constituency service (Cain, Ferejohn, and Fiorina Citation1984, Citation1987; Fenno Citation1978). Simply put, legislators nurture connections with their constituents because they pursue re-election, and the more insecure they are about re-election the more they will nurture connections with constituents. This assumption has been confirmed in several studies, using different metrics of electoral safety/vulnerability, but there are some exceptions.

Kartalis (Citation2023) demonstrates that Greek parliamentarians table more constituency-focused questions when they are more vulnerable. Kellermann (Citation2013) finds similar results for the sponsorship of early day motions in the House of Commons, while an experimental study by Habel and Birch (Citation2019) shows that UK MPs from safer seats are slower to respond to citizens’ requests. However, other studies indicate that electoral insecurity is not always a strong predictor of constituency-focused behaviour (Martin Citation2011). Departing from these approaches, André, Depauw, and Martin (Citation2015), show that the effect of legislators’ vulnerability on constituency efforts depends on electoral system characteristics. On the one hand, district magnitude decreases constituency efforts in non-preferential systems, and this effect grows weaker as legislators become more vulnerable. On the other hand, district magnitude increases constituency efforts in preferential systems, and this effect grows stronger among more vulnerable legislators.

MPs’ socio-demographic profile is included in studies that explore the role of age, gender, race/ethnicity/nationality or social class on constituency service. Anagnoson’s (Citation1983) study on New Zealand reveals that younger MPs do more constituency work than older MPs and that legislators from regional cities, suburbs or urban areas tend to spend more time doing constituency service activities than MPs from rural areas. A survey-based study by Thomas (Citation1992) showed preliminary evidence indicating that both female and black politicians tended to dedicate more time to constituency service and to prioritize different parts of their constituencies when compared to their white male counterparts in the US. Likewise, Freeman and Richardson (Citation1996) assessed gender differences in constituency service provision in the US and found that female legislators placed more emphasis on constituency work than their male counterparts.

Personal motivation/style explanations contend that constituency service is driven by MPs’ inner motivations – sense of duty, inner satisfaction, beliefs and role perceptions (Giger, Lanz, and De Vries Citation2020; Norris Citation1997; Searing Citation1985). Giger, Lanz and De Vries’ (Citation2020) experimental study with Swiss candidates illuminates how both intrinsic and extrinsic (electoral) motivations determine candidates’ response rates to service requests from voters. The study shows, on the one hand, that candidates display high response rates to service requests from voters both within and outside their district (canton), indicating inner motivations to be responsive, regardless of their connection to the district. On the other hand, it shows that responsiveness is higher in more competitive districts, suggesting that extrinsic motivations for constituency work overrule intrinsic motivations.

Among the remaining explanatory factors, the role of localness – the MPs’ biographical ties to their geographic constituency – is considered. Localness carries different meanings: whereas being born in or residing in the geographic constituency signals a sense of identity and belonging to the local community, having local-level political experience in the geographic constituency attests to the ability to handle local problems (Shugart, Valdini, and Suominen Citation2005). MPs with strong local ties may more naturally embrace their roles as agents and promoters of the local community’s interests and thus engage more in constituency service than MPs without these ties. Across electoral institutions, it has been found that at least one form of localness shapes constituency service. In the case of Portugal, MPs who have previously been elected local representatives in their districts table more questions on issues that are relevant for their district constituents (Borghetto, Santana-Pereira, and Freire Citation2020). In Italy, MPs who have been elected in the region in which they were born and live are more likely to table parliamentary questions mentioning it (Russo Citation2021) – and similar results were found in Chile (Dockendorff Citation2020).

The most common expectation concerning ideology is that MPs of leftist or liberal parties prioritize constituency service more than those of right-wing parties (Butler, Karpowitz, and Pope Citation2012; Campbell and Lovenduski Citation2015). Butler, Karpowitz, and Pope (Citation2012) experimental study unveils that Democrat members of Congress (US) are more responsive to service requests than to policy when compared to their Republican counterparts. Campbell and Lovenduski (Citation2015) survey to British MPs confirms that Liberal Democrat MPs are likely to prioritize constituency items in their top three roles as an MP more often than MPs from other parties.

The role of individual characteristics, motivations and preferences cannot be overlooked when defining the degree of constituency service, which seems to be higher when MPs fear being unseated and when they are less experienced. However, in addition to career-incentives – which are clearly more tested than other factors – we find that MPs’ role orientation is strongly determined by their identities (e.g. being black or female, left or right). This should encourage further integration of different MP-level variables into study designs.

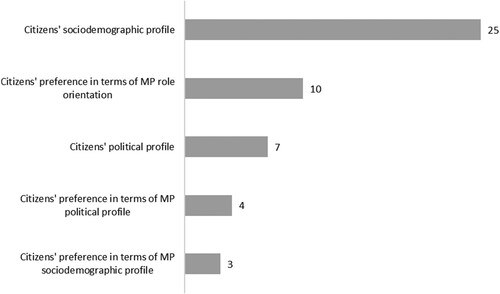

Citizen-level explanations

Citizen-level explanations are less covered when compared with the previous explanations. clusters different explanations, namely, what citizens value or prefer in terms of MPs’ sociodemographic and political profile and in terms of their role orientation,Footnote3 and citizens’ own characteristics, that is, their own sociodemographic and political profile.Footnote4 The main claim is that the social and political profile of constituents and how they evaluate MPs makes it possible to account for the variation in expectations and experiences of constituency service provision.

Figure 6. Citizen-level explanations of constituency service. Source: Authors' elaboration.

Note: The graph displays the N, i.e. the number of studies.

Vivyan and Wagner's (Citation2015) study illustrates citizens’ preferences regarding MPs from various perspectives. Drawing on a survey-based experience with UK citizens they find that individuals preferred MPs that prioritize spending time on the constituency and on local issues, but are, nonetheless dedicated to their national policy work. In terms of MPs’ policy positions, citizens showed a preference for MPs that represent constituents’ interests rather than ‘their own beliefs and principles’. Additionally, while citizens generally preferred MPs from their own party (in the cases of Labour and Conservative supporters), they also support MPs who acted independently from party lines and were willing to vote/speak out against their own leadership.

Several papers test the effect of citizens’ characteristics through surveys or experiments. For instance, Lapinski et al. (Citation2016) investigate the question of what constituents want from their members of Congress, drawing on several surveys conducted among citizens in the US. The authors find that most respondents, particularly sorted partisans (Democrats and Republicans) and highly educated citizens, prioritize issue/partisan representation over constituency service. Their statistical models controlled for various other citizen characteristics, such as age, gender, income, and so forth. Campbell and Lovenduski (Citation2015), who surveyed not only MPs but also citizens about the characteristics of a good MP, examined the impact of gender and age. They anticipated that British women and older voters would lean more towards constituency orientation, and while they received clearer confirmation for the latter, the evidence for the former was less conclusive. Landgrave (Citation2021) uses a field experiment to investigate whether race affects how responsive US state legislators are to requests for help with voter registration. The study shows that state legislators are less responsive to requests from blacks than from whites, and this difference is even more pronounced among Republican legislators (in part explained by the racial composition of the parties). Moreover, minority state legislators responded much more frequently to the black alias than to the white alias. Further experimental studies have explored the role of class in the US (Hayes and Bishin Citation2024) and the UK (Habel and Birch Citation2019) but found limited evidence that legislators discriminate along those lines.

Constituency service has been defined as non-contingent, non-partisan attention to the needs of citizens (Cain, Ferejohn, and Fiorina Citation1984); however, these studies reveal that constituency service can be contingent and partisan, among other things. Such bias suggests a representation gap whereby some citizens (or communities) have difficulty accessing services.

Consequences of constituency service

As previously noted (), the number of studies analysing constituency service as an explanatory factor is significantly lower. In most of these studies, the primary goal is to examine whether investing in constituency service improves MPs’ electoral career – re-nomination or re-election. However, the results are unclear. Chiru and Gherghina's (Citation2020) research on Romania shows that MPs who raise local issues in their questions and interpellations are more likely to be nominated in mayoral elections. Similarly, a study on Nigeria shows that while sponsorship of constituency-targeted bills and motions does not impact the decision to compete in primaries or other election positions, it seems to impact the likelihood of winning in an election (Demarest Citation2021). In contrast, Studlar and McAllister’s (Citation1996, p. 69) study on Australia reveals that ‘dealing with constituents’ grievances reduces a legislator's vote, mainly because such activity displaces other, more electorally advantageous party-focused activities’ (69). Studies in the US (McAdams and Johannes Citation1988) and in France (François and Navarro Citation2019) also confirm that constituency service is not what counts most for re-election. These results reveal that even if MPs do constituency service mainly for electoral purposes, their efforts are not always match by citizens’ votes, even in countries with candidate-centred systems such as US and Australia.

The second set of papers aims to understand the impact of constituency service on citizens’ evaluation/perception of either the MPs themselves or their role as representatives. The study by Sulkin, Testa, and Usry (Citation2015), for example, demonstrates that legislators’ copartisan, outpartisan, and independent constituents respond in different ways. Whereas overall constituents prefer moderate legislators who do their jobs and attend to their constituents, copartisans react negatively to Congress members’ district attention and prefer party loyalists. Finally, a third group of papers is miscellaneous, encompassing an extremely wide range of research goals that go from investigating the impact of constituency service on the durability of an authoritarian regime, as in Singapore (Ong Citation2015) or China (Distelhorst and Hou Citation2017) to explaining its effects on ticket splitting, as in the US (Roscoe Citation2003).

As for the few studies that treat constituency as both dependent and independent variables, the work by Lawrence McKay on the UK (Citation2020) offers a good illustration. It investigates what determines citizens’ evaluation of MPs’ national or local focus, and the levels of trust in MPs. The analyses show that the more MPs raise constituency-focused questions in parliament, the more they are seen as having a constituency rather than national focus; and that constituents’ trust in an MP increases as his/her constituency-focused parliamentary activity increases. Park’s (Citation1988) study on the sources and consequences of constituency service in Korea offers additional illustration. It reveals that MPs will be more likely to invest in constituency service for electoral reasons, among other factors, and that constituents will be aware of MPs’ activity and are likely to reward them at the ballot box.

This SLR sheds light on a literature that was mostly unknown, highlighting the fact that studies which seek to tackle the consequences of constituency service focus mostly on MPs and either their re-nomination/re-election or voters’ attitudes towards them. Going beyond MPs to explore further possible effects of constituency service is much less common in the literature (but see Ong Citation2015 or Distelhorst and Hou Citation2017).

New roads ahead: future research on constituency service

This section proposes a conceptualization of constituency service, as well as a series of key topics that might shape future research on the subject. Based on the SLR, it can be safely argued that constituency service is a multidimensional concept that covers a wide range of activities carried out by MPs to serve, represent, and distribute/allocate benefits to their constituents across multiple arenas (the district, the parliament and the digital sphere). Thus, proposes a dynamic conceptual approach for measuring constituency service, covering key arenas, dimensions and indicators. Previous studies had proposed a two-fold typology of constituency service, considering service and representative aspects (Arter Citation2018), and we take this exercise further by contemplating distributive/allocation efforts, and by clarifying arenas and indicators of constituency service.

Table 1. Constituency service: dimensions, arenas and indicators.

This conceptual exercise involved revisiting Eulau and Karps’ (Citation1977) four components of responsiveness – policy, service, allocation and symbolic responsiveness – as they overlap with some of the categories displayed in . It is striking that extant approaches to constituency service have covered different facets of what Eulau and Karps (Citation1977) see as separate forms political representation/responsiveness. In this sense, constituency service covers a wide repertoire of distributional and representational tasks.

It is clear from that different configurations of constituency service can be investigated depending on whether we look at one or more dimensions, and whether we explore one or more arenas. The service dimension, which is more widely studied and connected to the concept, refers to a set of activities that constituents expect from representatives, and that representatives often perceive as being part of their role as good constituency members (Searing Citation1985). It includes more personalized and particularized forms of casework (e.g. requests to solve individual problems or those of specific groups of constituents), information provision in the district, digital home-styles, or advocacy in parliament. This dimension is often understood as a form of service provision rather than a form of responsiveness (as proposed by Eulau and Karps Citation1977).

Representation/responsiveness encompasses activities related to MPs’ efforts to represent constituents’ interests and respond to their needs in more substantive ways. Representatives are not only interested in providing a service, but more importantly, they listen and learn about their constituents to better inform policy decisions. This may include whether MPs respond to citizens’ requests, organize consultations and meetings in the district to better understand their needs, develop a set of initiatives in parliament (bills, questions, etc.) or solicit constituents’ views digitally. Finally, distribution/allocation refers to the representative’s efforts to obtain benefits for her/his constituency through distributive policies. These include ‘taxes and transfers, and in particular the decisions about allocations of government goods and services to identifiable localities or groups’ (Golden and Min Citation2013, 74). They might involve constituency development funds, subnational budget allocation, but also individual and collective pork- allocations (Bussell Citation2019; Golden Citation2003).

Building on this conceptualization, broader definitions of constituency service may include the activities carried out by MPs in the district, in parliament and the digital sphere, while narrower definitions focus on just some of these dimensions or arenas. By decomposing constituency service, it is possible to explore whether its dimensions are positively correlated and whether they behave the same across institutional settings. For example, one crucial debate in the literature is that constituency service is less relevant in CLPR than in plurality systems; this is because candidates in the latter are elected in single-member constituencies, which means they need to have a strong local base of support to win election. Several studies have shown that this is not always the case and that MPs in CLPR care about their constituents (Heitshusen, Young, and Wood Citation2005; Struthers Citation2018). However, this debate could be enriched by investigating which types of activities are more prevalent across electoral institutions and MPs. It may be that MPs in CLPR systems have more incentives to act in the parliamentary arena than to travel to their districts for casework as they can use the floor to raise constituency-focused questions.

So what data is particularly useful for capturing constituency service and how should it be approached methodologically? The SLR points to plural approaches, ranging from participant observation to text analysis via interviews and surveys, which suggests that there is no pre-determined methodological ‘toolkit’. However, given that the field has been dominated mainly by quantitative methods and data (), which have produced inconsistent findings, one way forward would be to focus on qualitative methods and data. Such an approach would help specify mechanisms and scope conditions for the occurrence of constituency service. More granular data on the demand-side (citizens) of constituency service is also crucial to map citizens’ attempts to make their voice heard and/or narrow the representation gap.

The SLR has also provided an opportunity to identify gaps and topics that can inform a future research agenda. Some works highlight the importance of the institutional capacity variable to understand different modalities of constituency service, but also the thin line between patronage and constituency service – a link that is worth exploring. Opalo's (Citation2022) work on the implementation of constituency developments funds in Kenya explains why MPs engage in more personalized and clientelistic forms of constituency service. Since MPs cannot rely on strong institutions to fulfil their representational tasks, they deploy their own personal resources to signal responsiveness to voters (Opalo Citation2022). In post-war Italy, in the context of an inefficient public administration, where appointments are made according to political patronage rather than meritocracy, Golden (Citation2003) finds that incumbents have more incentive to develop compensatory forms of constituency service. The study reveals that weak institutions can be purposely sustained by both politicians and voters for instrumental reasons: the former to pursue electoral gains and the latter to obtain particular benefits (Golden Citation2003). Brouard et al.’s (Citation2013, 157) study offers additional insight on weak institutional capacity by arguing that the institutional weakness of France’s National Assembly partly explains why MPs prefer constituency work over parliamentary work.

The role of parties is also neglected, particularly in party-centred systems where constituency service is seen as less valuable. Notwithstanding, a recent study on South Africa (Sanches and Kartalis Citation2024) reveals that constituency service is shaped by the type of party and whether or not the MPs is representing a stronghold, thus revealing that MPs may find good reasons to cater to district interests in party-centred environments.

Another promising research avenue emerges from a set of studies that seeks to explore the meaning and effects of constituency service in non-democratic governments (such as hybrid or authoritarian regimes) as highlighted by studies on Pakistan (Mangi, Soomro, and Larik Citation2021), Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan (Somfalvy Citation2021), Morocco and Algeria (Benstead Citation2016), Singapore (Ong Citation2015), China (Distelhorst and Hou Citation2017) and Malaysia (Weiss Citation2020). These studies have provided the opportunity to investigate constituency service in less conducive environments showing how it can contribute to ‘entrench authoritarianism and deter democratic pressures’ (Ong Citation2015, 363) and how it often overlaps with the development of clientelist relations between MPs and citizens (Weiss Citation2020). Future research should try to explore not only the dominant forms of constituency service in more autocratic settings, but also its relations with personalized forms of clientelism and with regime survival more broadly.

The SLR also suggests the need for more studies focusing on MPs’ strategies and calculations. For example, Saalfeld (Citation2011) offers important contributions to understanding electoral connection between voters and the MPs that go beyond the geographic boundaries of the constituency. His study shows that British MPs respond to electoral incentives arising from the socio-demographic composition of their constituencies regardless of their ethnic status. Minority and non-minority MPs tend to ask more questions that address minority concerns if they represent constituencies with a high share of non-White residents. While the study also finds that MPs with a visible-minority status do tend to ask significantly more questions about ethnic diversity and equality issues, the general findings point to the importance of analysing the representative connection between MPs and social groups that are geographically dispersed.

Another relevant question that warrants further research is why MPs prefer certain forms of constituency-focused activities to others. In the US, senior legislators prefer pork barrel activities over casework (Ellickson and Whistler Citation2001), while in Turkey legislators will engage in tasks that please the party leadership – submitting questions in parliament rather than doing casework and pork barrel activities if they perceive the party leader to be the most influential actor in re-selection (Ciftci and Yildirim Citation2019). These two studies are among the few that have aimed to explain why MPs select certain constituency-focused activities over others.

More research is also needed to better understand the classical question posed by Fenno (Citation1978): ‘What does an elected representative see when he or she sees a constituency?’. Miler (Citation2007) addresses this puzzle in innovative ways and shows, for example, that MPs see the constituents about whom they have more information, who offers them more (monetary) contributions or raise issues that are familiar to them. In relation to this, comparative approaches would help explore whether MPs’ perceptions of their constituency and constituency service vary across electoral systems, district and MPs characteristics. There is also a lack of studies that can inform us not only about citizens’ views but also the channels and mechanisms they use to make themselves ‘visible’ and heard by their representatives.

Scholars have also expanded on the limits of how we perceive and study the concept of constituency service by borrowing – both methodologically and theoretically – from other scientific areas, demonstrating how the concept can be understood through lenses other than those of political science. This is true for three studies in our sample, all focusing on the UK: Jackson and Lilleker (Citation2004) take on British MPs from a perspective of media, communication, and public relations, Warner's (Citation2021) social work approach (that employs notions such as emotions and empathy to characterize MPs’ constituency service), and Vivyan and Wagner (Citation2015) who use a marketing-inspired methodological approach to understand citizen preferences. This suggests that more can be done from a multidisciplinary perspective.

Moving beyond the prominence of quantitative approaches for studying constituency service, it could be fruitful to retrieve the ethnographic approach found in Fenno’s (Citation1978) seminal studies and follow the legislators in their travels, encounters, and everyday legislative activities. The latter would possibly intertwine and contribute to ongoing research on the everyday life of parliaments and legislators (e.g. Crewe Citation2021). Finally, in an area predominantly characterized by case studies (particularly western democracies), comparative work and more focus on Global South countries would be particularly welcome.

Conclusion

Constituency service is a key element of representation and feeds democratic legitimacy and accountability. However, an SLR is justified to better clarify the state of the field given that our understanding of constituency service, how it varies and what its consequences are remain contested. While we cannot discard of possibility of having accidentally excluded studies from the sample due to the plethora of meanings, terms and activities associated with constituency service, our results are revealing and meet the goals of an SLR. Constituency service has not been a mainstream topic of research in political science literature for a long time and yet our review suggests that this trend is shifting. The previous decade has presented us with new and exciting works that attempt to broaden the scope of this concept, via innovative methodological approaches (such as experiments, and mixed-methods), and more diverse case-studies (as is the case of autocracies and newer democracies from the Global South).

A lot has changed since Fenno (Citation1978) and, while his definition of constituency service remains as relevant as ever, notions such as the way citizens perceive politicians and what they expect from them, the means of communication between constituents and elected officials, and how politicians see themselves and their roles as representatives have gradually evolved over time. First, while there is still a clear focus on service activities (e.g. casework, home-styles), we are becoming increasingly aware of MPs’ representation/responsiveness activities (e.g. constituency-focused parliamentary activities) and distributive/allocation activities (e.g. project and budget allocation). Second, constituency service provision varies due to a wide range of macro-level (e.g. political institutions, district characteristics, and contextual factors), MP-level (e.g. political career, election prospects, ideology, and motivation) and citizen-level factors (e.g. socio-demographics, and political profiles). This makes it an exciting concept to focus on and future research – for example a meta-analysis – should help illuminate the most decisive set of explantory variables. Third, the research on the consequences of constituency service is relatively scarce, and mainly addresses its effects on the evaluation of MPs or their re-selection/re-election chances. Understanding the consequences of constituency service is important because it expresses the strength and vitality of the links between voters and representatives.

The study also advanced a dynamic conceptual approach for studying constituency service, which allows the mapping and measuring of the activities pursed by MPs to serve, represent and distribute goods to their constituencies, across different arenas (district, parliament, and digital sphere). This conceptualization can inform both broader and narrower operationalizations of constituency service. Finally, we identified several topics for developing a future research agenda. On the theoretical front, exploring the impact of (weak)institutional capacity, possible areas of overlap between clientelism and constituency service, the connection between MPs and geographically dispersed constituencies, and the consequences of constituency service, may prove itself extremely valuable to generate new knowledge and evidence on this phenomenon. On the methodological front, more research is needed on (non)democratic governments and Global South countries, in order to encourage within-region and cross-regional comparisons. Additionally, methodological pluralism and multidisciplinary lenses can offer new insights to a more complete understanding of constituency service.

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely thankful to the journal's Editors and five anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and constructive critique.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Earlier versions of this list were presented and discussed at the Project ‘How members of parliament in Africa represent their constituencies – HOME' (Ref. PTDC/CPO/4796/2020; https://doi.org/10.54499/PTDC/CPO-CPO/4796/2020) meetings. Keywords were also added following reviewers’ recommendations.

2 While some local ties refer to socio-demographics (being born or native in the district) and other to political career (having been a politician in the district), we decided to treat localness as a category as it is a very crucial concept in the field.

3 See codebook (supplementary material) for the full list of variables coded as MPs’ sociodemographic profile.

4 See codebook (supplementary material) for the full list of variables coded as Citizens’ sociodemographic and political profile.

References

- Adler, E. S., C. E. Gent, and C. B. Overmeyer. 1998. “The Home Style Homepage: Legislator Use of the World Wide Web for Constituency Contact.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 23 (4): 585–595. https://doi.org/10.2307/440242.

- Anagnoson, J. T. 1983. “Home Style in New Zealand.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 8 (2): 157–175. http://www.jstor.org/stable/439426.

- Anagnoson, J. T. 1991. “Home Style in New Zealand.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 16 (3): 375–392. https://doi.org/10.2307/440103.

- André, A., J. Bradbury, and S. Depauw. 2014. “Constituency Service in Multi-Level Democracies.” Regional and Federal Studies 24 (2): 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2013.858708.

- André, A., and S. Depauw. 2013. “Electoral Competition and the Constituent-Representative Relationship.” World Political Science Review 9 (1): 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1515/wpsr-2013-0013.

- André, A., S. Depauw, and S. Martin. 2015. “Electoral Systems and Legislators’ Constituency Effort: The Mediating Effect of Electoral Vulnerability.” Comparative Political Studies 48 (4): 464–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414014545512.

- Arter, D. 2018. “The What, Why’s and How’s of Constituency Service.” Representation 54 (1): 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2017.1396240.

- Bandau, F. 2022. “What Explains the Electoral Crisis of Social Democracy? A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Government and Opposition 50 (1): 183–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2022.10.

- Bárcena Juárez, S. A., and Y. P. Kerevel. 2021. “Communicative Responsiveness in the Mexican Senate: A Field Experiment.” Democratization 28 (8): 1387–1405. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1907348.

- Baxter, G., R. Marcella, and M. O’Shea. 2016. “Members of the Scottish Parliament on Twitter: Good Constituency Men (and Women)?” Aslib Journal of Information Management 68 (4): 428–447. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-02-2016-0010.

- Benstead, L. J. 2016. “Why Quotas Are Needed to Improve Women’s Access to Services in Clientelistic Regimes.” Governance 29 (2): 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12162.

- Borghetto, E., J. Santana-Pereira, and A. Freire. 2020. “Parliamentary Questions as an Instrument for Geographic Representation: The Hard Case of Portugal.” Swiss Political Science Review 26 (1): 10–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12387.

- Bradbury, J. 2007. “Conclusion.” Regional and Federal Studies 17 (1): 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560701189677.

- Brouard, S., O. Costa, E. Kerrouche, and T. Schnatterer. 2013. “Why Do French MPs Focus More on Constituency Work than on Parliamentary Work?” The Journal of Legislative Studies 19 (2): 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2013.787194.

- Bussell, J. 2019. Clients and Constituents: Political Responsiveness in Patronage Democracies. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Butler, D. M., C. F. Karpowitz, and J. C. Pope. 2012. “A Field Experiment on Legislators Home Styles: Service Versus Policy.” Journal of Politics 74 (2): 474–486. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381611001708.

- Cain, B. E., J. A. Ferejohn, and M. P. Fiorina. 1984. “The Constituency Service Basis of the Personal Vote for U.S. Representatives and British Members of Parliament.” The American Political Science Review 78 (1): 110–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/1961252.

- Cain, B., J. Ferejohn, and M. Fiorina. 1987. The Personal Vote: Constituency Service and Electoral Independence. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Campbell, R., and J. Lovenduski. 2015. “What Should MPs Do? Public and Parliamentarians’ Views Compared.” Parliamentary Affairs 68 (4): 690–708. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsu020.

- Cancela, J., and B. Geys. 2016. “Explaining Voter Turnout: A Meta-Analysis of National and Subnational Elections.” Electoral Studies 42:264–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.03.005.

- Chiru, M. 2018. “The Electoral Value of Constituency-Oriented Parliamentary Questions in Hungary and Romania.” Parliamentary Affairs 71 (4): 950–969. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsx050.

- Chiru, M., and S. Gherghina. 2020. “National Games for Local Gains: Legislative Activity, Party Organization and Candidate Selection.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 30 (1): 64–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2018.1537280.

- Ciftci, S., and T. M. Yildirim. 2019. “Hiding Behind the Party Brand or Currying Favor with Constituents: Why Do Representatives Engage in Different Types of Constituency-Oriented Behavior?” Party Politics 25 (3): 369–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068817720438.

- Costa, O., and C. Poyet. 2016. “Back to Their Roots: French MPs in Their District.” French Politics 14 (4): 406–438. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-016-0014-5.

- Crewe, E. 2021. An Anthropology of Parliaments. Entanglements in Democratic Politics. London: Routledge.

- Crisp, B. F., and W. M. Simoneau. 2017. “Electoral Systems and Constituency Service.” In The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems, edited by E. S. Herron, R. J. Pekkanen, and M. S. Shugart, 345–363. Oxford University Press.

- Dacombe, R. 2018. “Systematic Reviews in Political Science: What Can the Approach Contribute to Political Research?” Political Studies Review 16 (2): 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929916680641.

- Demarest, L. 2021. “Elite Clientelism in Nigeria: The Role of Parties in Weakening Legislator-Voter Ties.” Party Politics 28 (5): 939–953. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688211030219.

- Distelhorst, G., and Y. Hou. 2017. “Constituency Service Under Nondemocratic Rule: Evidence from China.” Journal of Politics 79 (3): 1024–1040. https://doi.org/10.1086/690948.

- Dockendorff, A. 2020. “When Do Legislators Respond to Their Constituencies in Party Controlled Assemblies? Evidence from Chile.” Parliamentary Affairs 73 (2): 408–428.

- Dovi, S. 2015. “Hanna Pitkin, the Concept of Representation.” In The Oxford Handbook of Classics in Contemporary Political Theory, edited by J. T. Levy, 1–15. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ellickson, M. C., and D. E. Whistler. 2001. “Explaining State Legislators’ Casework and Public Resource Allocations.” Political Research Quarterly 54 (3): 553–569. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290105400304.

- Eulau, H., and P. D. Karps. 1977. “The Puzzle of Representation: Specifying Components of Responsiveness.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 2 (3): 233–254. https://doi.org/10.2307/439340.

- Fenno, R. F. 1978. Home Style. House Members in Their Districts. Boston: Little Brown.

- François, A., and J. Navarro. 2019. “Voters Reward Hard-Working MPs: Empirical Evidence from the French Legislative Elections.” European Political Science Review 11 (4): 469–483. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773919000274.

- Franks, C. E. S. 2007. “Members and Constituency Roles in the Canadian Federal System.” Regional and Federal Studies 17 (1): 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560701189602.

- Freeman, Patricia K., and Lilliard E. Richardson. 1996. “Explaining Variation in Casework among State Legislators.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 21 (1): 41–56. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/440157. Accessed 9 July 2024.