ABSTRACT

Classical electoral behaviour theories have associated possible benefits of negative campaigning with two-party plurality systems due to their zero-sum nature. Nevertheless, negative campaigning is a widely used electoral strategy outside of these contexts, despite scant evidence of its benefits for political parties and candidates who employ it. Our research question is simple – is negative campaign messaging effective for attackers in multiparty systems with multimember districts? Or does it create a ‘boomerang effect’ in this context, for which the producer of the message faces a backlash? Multiparty systems with multimember districts should, according to the literature, be scenarios where the effects of negative campaigning are most complex if not unpredictable. This paper uses Facebook political messages to inform a survey experiment design that tests the effects of negative political messaging on voters. We employ this survey in Ireland, which uses the single transferable vote, an electoral system which magnifies outcome uncertainty for attackers. Our results suggest that negative messaging in this context produces both the intended effect and a boomerang effect for the sponsor of the message. These countervailing results suggest a net null effect for the efficacy of negative messaging.

Introduction

Use of negative messaging (e.g. messages that focus on the weakness of a rival party or candidate), which is generally associated with two-party contexts such as the USA, is also a widespread political phenomenon in multiparty systems (Belt Citation2017; Duggan and Milazzo Citation2023; Elmelund-Præstekær Citation2008; Citation2010; Galasso, Nannicini, and Nunnari Citation2023; Hansen and Pedersen Citation2008; Walter Citation2014; Walter and van der Brug Citation2013). While its effects on voting behaviour are extensively studied in the two-party single-member district context of the USA (Haselmayer Citation2019; Lau and Pomper Citation2002), comparatively little is known about its efficacy outside of this context. This narrow focus in previous research also means that there is limited work on how the theoretical expectations and causal mechanisms related to negative messaging vary across different types of electoral and party systems (Haselmayer Citation2019; Somer-Topcu and Weitzel Citation2022; Walter 2014). This paper offers one of the first analyses that discusses theoretical expectations and implications, and estimates experimental treatment effects for both attackers and targets on voting behaviour in a multiparty system with multimember districts, which – according to the literature – represent contexts where the effects of negative campaigning are most complex if not unpredictable. Accordingly, our analysis offers a significant contribution to the existing knowledge base on negative messaging and provides a template that can be used in other contexts operating with similar political institutions.

Our research question is simple – is negative campaign messaging effective in influencing voting behaviour in multiparty systems with multimember districts? Or does it create a ‘boomerang effect’ in this context, for which the attacker faces a backlash? To shed light on this, we test the destabilizing and boomerang effects of negative campaign messages in a suitable context.

We choose Ireland as the focus of this study because its electoral and party systems identify it as a ‘most likely’ context for effects of negative campaigning. Ireland has a multiparty system with three main parties, five smaller parties with 2–5 per cent support,Footnote1 and a significant presence of independent politicians with 19 elected at the 2020 General Election (Gallagher Citation2021; Müller and Regan Citation2021). Ireland uses the single transferable vote system, which allows voters to rank candidates in three-to-five member districts with lower preferences often deciding the winner of the final seat in a given district (Farrell Citation2011; Gallagher and Mitchell Citation2005). This system allows voters to split their preferences across party lines, providing maximum flexibility in how they choose to rank candidates. This flexibility of voter choice and the presence of many ideologically proximate candidates in each district means there is greater scope for voter preferences to change as a result of negative messaging. However, it should also make it difficult for political parties who engage in negative campaigning to predict electoral gains compared to two-party systems or multiparty systems with single member districts. As a result, Ireland is a ‘most likely’ case for negative messaging effects but where the impact of such a strategy should be ‘most unpredictable’ for the attacker. This makes it a crucial case for the understanding of negative campaigning in circumstances of uncertainty.

We employ a novel survey experiment conducted with approximately 1,600 voters recruited through the polling company Ireland Thinks. As treatments, we use slightly edited video messages created by two important Irish political parties (Sinn Féin and Fine Gael) attacking each other. To account for content variation in the treatments, we include messages on housing, a salient policy issue, and a non-policy issue, namely attacks related to political integrity. This is a rare test of treatments which closely resemble real world messages.

Our respondents are typical voters of Sinn Féin and Fine Gael that expressed an intention to vote for either party at the last general election. By focusing exclusively on supporters of these two parties (and excluding supporters of other parties or undecided voters), we address an important trade-off of the study, internal and external validity. On one hand, by excluding other voters we limit the generalisability of the study’s results to other partisan or undecided voters. On the other hand, by limiting our study to this group we are able to offer a direct test of negative message effects for voters of both the attacker and target parties across two distinct issue areas. That is, we observe how supporters of both the attacker and the target react to negative messages. The advantage of such an approach is that it allows for a simultaneous observation of destabilization and boomerang effects for the attacker, which result in a net effect of negative campaigning that is rarely directly estimated (Lau, Sigelman, and Rovner Citation2007).

Our results suggest that negative messaging does have a statistically and substantively significant impact on partisan respondent choices. However, this involves both classic destabilization effects on target party voters and evidence of a boomerang response by a proportion of attacker party voters, illustrating the opportunities, but also the risks, of ‘going negative’ in multiparty systems with multimember districts. These results carry important implications for both political parties employing negative campaign messages and voters exposed to them.

Our paper is structured as follows. We first provide an overview of literature on negative campaigning, from which we derive our propositions applied to multiparty systems with multimember districts. We then discuss the rationale for studying the Irish case in detail, followed by an outline of our experimental design, survey data, and methods. We then present the results of our statistical analysis. We conclude our study with an in-depth discussion of our results and their theoretical and practical implications.

Negative campaigning

There are a number of dimensions along which campaign messages may vary. Our primary focus, in line with much of the established literature, is on messages that have a negative tone focusing on the limitations of opponents rather than a positive tone focusing on one’s own accomplishments (Brooks and Geer Citation2007). This negative campaigning involves the use of communication strategies which directly attack the programmes, ideas, accomplishments, qualifications, issue positions (and so on) of political opponents for electoral gain (Haselmayer Citation2019; Lau et al. Citation1999; Citation2007; Lau and Pomper Citation2002).

Among the primary gains political parties employing these strategies expect are direct impacts on the voting behaviour of citizens. Such strategies are, more precisely, designed to reduce and demobilize support for opponent parties and candidates (Krupnikov Citation2011; Citation2014; Skaperdas and Grofman Citation1995). We refer to these as ‘destabilising effects’. Despite the belief among political operatives that negative messaging may generate sizable effects (Nai and Walter Citation2015), its efficacy within the literature is contested.

Meta-analyses such as Lau et al. (Citation1999; Citation2007) suggest that the overall destabilizing effects of negative messaging on vote intentions are not only questionable but also highlight the systematic potential of producing unexpected effects that backfire against the promoter of the message, i.e. ‘boomerang effects’. Banda and Windett (Citation2016) find that a boomerang effect may materialize if voters sympathize with the targeted party and decide to support the target as a result. This may be because voters tend to dislike negativity (Ansolabehere et al. Citation1994) and react with cognitive dissonance to attacks they disagree with (Taber and Lodge Citation2006). clarifies the definitions of destabilization and boomerang effects.

Table 1. Overview and definition of destabilizing and boomerang effects in negative messaging.

Despite the results of these analyses, political actors continue to perceive some benefit to negative campaigning (as demonstrated by its continued use). It is possible that the large amount of heterogeneity inherent to negative messaging is responsible for disparate conclusions within the literature (Haselmayer Citation2019). To make sense of such complexity, previous studies have explored variations in content, intensity, policy area, context, partisanship, or voter characteristics as potential moderators of the impact on the efficacy of a given negative political message. For example, recent works have demonstrated the important moderating impact of partisanship in how negative messages are perceived by voters (Haselmayer, Hirsch, and Jenny Citation2020) and how voting preferences for the target are impacted (Somer-Topcu and Weitzel Citation2022). Other studies have explored how variation in characteristics such as political ideology (Jung and Tavits Citation2021) and personality traits (Nai and Maier Citation2021; Nai and Otto Citation2021) moderate the way voters are impacted by negative messaging. Additionally, while results are not always aligned with the researcher’s expectations (Carraro and Castelli Citation2010), previous literature tends to suggest that personal and ‘uncivil’ attacks tend to have greater impacts on voters’ evaluations of candidates (Brooks and Geer Citation2007; Fridkin and Kenney Citation2011; Hopmann, Vliegenthart, and Maier Citation2018).Footnote2 Carraro, Gawronski, and Castelli (Citation2010) find that personal attacks damage opinions of the attacking candidate while Mattes and Redlawsk (Citation2014) suggest that a boomerang effect is more likely when the content of an attack focuses on an opponent’s personal life.

Yet, the verdict on the impacts of negative campaigning on voters’ behaviour remains open with important gaps still to be filled. Primarily, while scholarly attention to negative messaging is increasing among European scholars, the impact of this strategy outside of the American context remains understudied. More specifically, because of the complex effects of negative messages illustrated in previous studies, the consequences of such campaigning on voting behaviour are generally studied in two-party systems such as the US or in multiparty systems with single member districts (for studies on the former: Ansolabehere et al. Citation1994; Garramone et al. Citation1990; Kahn and Kenney Citation2004; Lau and Pomper Citation2002; Merritt Citation1984; Phillips, Urbany, and Reynolds Citation2008; Pinkelton Citation1997; Roddy and Garramone Citation1988; for studies on the latter: Galasso, Nannicini, and Nunnari Citation2023; Roy and Alcantara Citation2016; Sanders and Norris Citation2005; Walter and van der Eijk Citation2019). As such, even when multiparty systems are considered, the context often remains limited to single-member districts, limiting voters’ alternatives to the strongest candidates. In these contexts, destabilizing voter preferences can be directly beneficial if the voter switches to the attacker (i.e. the only other viable party). It can also be indirectly beneficial by demobilizing opposition voters (Ansolabehere et al. Citation1994; Krupnikov Citation2011; Citation2014) or prompting them to ‘waste’ their vote on a third party. For example, Galasso, Nannicini, and Nunnari (Citation2023) innovatively tested both destabilization and boomerang effects in the Italian context. In this analysis, the target was unaffected while the attacker suffered sizable backlash effects. Importantly, they also found evidence of increased favourability for third candidates, that is neither the attacker nor the target. Their study, however, focuses on mayoral elections in a single member district. As such, these effects remain unexplored in a context like Ireland where there are both multimember districts and a diverse multiparty system. Given the flexibility of voter choice on the STV ballot, the low cost of changing your first preference vote, and the presence of many ideologically proximate candidates in each district, we might expect the target to also suffer negative effects, contrary to the findings of Galasso, Nannicini, and Nunnari (Citation2023).

Finally, while there have been a number of studies focusing on multiparty systems with multimember districts (for impact on attackers, see: Hopmann, Vliegenthart, and Maier Citation2018; Mendoza, Nai, and Bos Citation2024; Pattie et al. Citation2011; Poljak Citation2023; for targets, see: Somer-Topcu and Weitzel Citation2022), none of these offer direct experimental estimation of effects. Accordingly, our analysis offers the first large-N experimental estimation of effects in multiparty systems with multimember districts while also offering the first such analysis in the context of STV. The distinct ballot structure of STV in comparison to other multimember electoral systems found in Scotland or Germany (Pattie et al. Citation2011; Hopmann, Vliegenthart, and Maier Citation2018), or in many list systems in continental Europe (Poljak Citation2023; Somer-Topcu and Weitzel Citation2022) provide unique incentives for both political actors and voters. This allows us to offer novel contributions to the literature.

Negative political messages in multiparty systems with multimember districts

Walter (2014) provides the first major analysis of patterns of negative campaigning in a Western Europe setting. This analysis demonstrates significant variation in negative campaigning across European countries likely due to the variation in electoral systems, a primary reliance on issue-based attacks, and a lower aggregate level of negative campaigning than in the United States. While this analysis also found no evidence of a rise in negative campaigning across the period studied, the use of this electoral strategy remains substantial outside of the US context (Nai Citation2020; Walter 2014; Walter and Nai Citation2015).

However, in contrast with two party systems, research on its effects in multiparty systems with multimember districts is scant. Among the few existing studies, almost all link survey data on voter preferences to indirect measures of negativity such as media content (Somer-Topcu and Weitzel Citation2022), parliamentary questions (Poljak Citation2023), or expert coding (Mendoza, Nai, and Bos Citation2024). Additionally, Pattie et al. (Citation2011) use election survey data to find that voters in the 2007 Scottish Parliament election were less likely to back a party if they perceived their campaign to be negative. However, even if conducted in the additional member system of Scotland, this study focuses on what are predominantly single-member district races,Footnote3 where – even if alternative candidates are running – incentives for voters to divert votes to smaller parties are weak (Duverger Citation1963). To our knowledge no experimental studies on the impacts of negative campaigning in multiparty systems with multimember districts exist.Footnote4 This is a relevant gap considering the importance of this research design for establishing causal mechanisms, and links between political messages and voters’ behaviour in circumstances where alternative options are available and votes for small parties are not wasted.

This empirical gap in multiparty systems with multimember districts is related to the complexities associated with voting behaviour in such systems. These contexts tend to produce fragmented party systems and relatedly, coalition governments. The need to make deals with other parties may reduce the level and/or frequency of attacks against possible coalition partners (De Nooy and Kleinnijenhuis Citation2015) while the number of viable alternative candidates/parties that are ideologically proximate in such systems reduces the possible benefit of ‘going negative’ and increase uncertainty of the effect of any attack (Valli and Nai Citation2022). Electoral systems with open lists or single transferable votes facilitate effects of negative messages on changes in the order of voter preferences, introducing another layer of complexity and unpredictability for the message’s sponsor. Additionally, the cost of vote switching is much reduced under STV (even in comparison to other list systems) given that the voter has the flexibility to vote across party lists.Footnote5

In multiparty contexts with multimember districts, negative campaign messages may destabilize support for the target as in two party systems. However, given the presence of multiple alternative parties and candidates, it is not straightforward that these messages will be electorally beneficial for the attacker (Nai Citation2020). Rather than benefiting the attacker, negative messaging in such contexts may instead benefit idle candidates or parties, i.e. those that are not involved in the negative exchange (Galasso, Nannicini, and Nunnari Citation2023). This may be explained by voters’ general unease with aggressive campaigns and negative tones (Ansolabehere et al. Citation1994; Fridkin and Kenney Citation2011). Unlike two-party and single-member contexts, where negative attitudes towards aggressive campaigns can demobilize voters, in multiparty systems with multimember districts, voters can easily divert to third options, away from both attacker and target.

This risk is amplified by the potential of a straightforward boomerang effect; that is, hurting the attacker (Garramone Citation1984). In terms of cost–benefit analysis, the amplified risks of ineffective negative messaging alongside the persistent issue of potential backlash effects means ‘going negative’ is a risky strategy in multiparty systems with multimember districts; or at least, its benefits should be far less straightforward than in other contexts. While Valli and Nai (Citation2022) have offered some evidence that there is no difference in the frequency of negativity in such systems, there is no extant experimental study of the effectiveness of negativity in these systems. Building on the existing US scholarship, we develop hypotheses on the effects of negative messaging that apply to multiparty systems with multimember districts.Footnote6

Negative messaging, like all campaign messaging, may shape preferences through the provision of additional information that voters weigh in rational calculations. Political parties producing negative messages seek to select and highlight particular information that is intended to harm voters’ rational evaluation of the targeted party. Along with this mechanism of evaluation, negative messaging is shown to be effective due to ‘negativity bias’ with voters tending to give more weight to negative information (Soroka Citation2014).

There are reasons to believe that negative campaign messages may also impact voter preferences by providing cues that induce a negative affective response among the audience (Brader Citation2006; Marcus, MacKuen, and Neuman Citation2011). The role of emotional response is critical in our understanding of voter reaction to negative campaigning and draws on the theoretical framework of affective intelligence. Within this framework, emotional response precedes the process of rationality, and differential emotional responses may generate distinct mechanisms of effect on vote choice. For example, voters who are made to feel anxious about their political choice may seek out new information and reconsider their voting decision (Weeks Citation2015). Anger has also been associated with the same channel of emotional affect as anxiety, at least in some circumstances (Ridout and Searles Citation2011). In generating a sense of anger or anxiety towards the targeted party, voters inclined to vote for it form negative associations and may switch their vote or choose not to turnout. In this way, this causal mechanism for negative messages is typically framed as an emotional response that results in the destabilization of voter preferences.

However, there is also the potential for a negative affective backlash response among voters that are turned off by negative campaign tactics. Voters may disapprove of campaigning strategies which violate well-established expectations of how politicians are expected to communicate and may similarly disapprove of communication that violates social norms of polite and non-conflictual discourse (Fridkin and Kenney Citation2011). Messages that attack opponents’ policies or character can appear opportunistic, mean-spirited, and less cooperative than those that emphasize a party or candidate’s own strengths (Mendoza, Nai, and Bos Citation2024; Roy and Alcantara Citation2016). Another important role in such a mechanism is played by cognitive dissonance theory, i.e. an individual’s internal needs for consistency in attitudes and beliefs (Festinger Citation1957). However, voters may be less disapproving of negativity generated by parties they prefer, especially where there are few alternatives to switch to as a ‘punishment’ for such negativity (Haselmayer, Hirsch, and Jenny Citation2020). In contexts with multimember districts and multiple parties, the variety of options available can provide much greater ‘room to move’ for voters who disapprove of negative campaigning.

Based on the preceding discussion, it is possible to theorize that we would observe both destabilization and boomerang effects in a multiparty system with multimember districts. There are two key features of these systems that lead us to the two hypotheses listed below: (1) The existence of multiple viable and ideologically proximate candidates reduces the barriers and risks associated with voters changing their minds. In addition to ideological proximate options, the presence of alternatives that are within the same ‘qualitative party family’ provides even more choice for voters (Mendoza, Nai, and Bos Citation2024). (2) The proportional nature of the electoral districts means voters can change their mind without risk of wasting their vote, in contrast to single member districts. This cost is particularly low in the chosen context of STV given its flexible ballot structure and the option to vote across party lists.

Destabilizing effect – H1a: Negative campaign messages will destabilize the preferences of voters that intended to vote for the target of the negativity. (Measured through vote intention).

Boomerang effect – H1b: Negative campaign messages will ‘boomerang’ and negatively affect the preferences of voters that intended to vote for the attacker. (Measured through vote intention).

Case selection: negative political messages in Ireland

We select Ireland as a ‘most likely’ case to test for both destabilization and boomerang effects of negative campaigning due to the features of its electoral and party system. Specifically, the structure of the ballot, the presence of multiple ideologically proximate options, and the relatively low cost of vote switching. Additionally, we focus on two parties, Fine Gael and Sinn Féin, that we consider most likely to employ negative campaigning in the Irish context.

Elections in Ireland operate under the Single Transferable Vote (STV) electoral system. The system uses multimember districts which elect three, four, or five TDs (Members of Parliament). The ballot structure of STV allows the voter to cast preference votes from one to the number of candidates contesting the constituency, though they may opt to give a number of preferences less than the maximum. This ballot structure means the voter can choose a party and candidate for each of their preferences and allows for simultaneous inter – and intra-party competition. The threshold for election (quota) is defined as the valid votes divided by district magnitude plus one, ignoring any fraction, and adding one. In general, few candidates exceed the quota on the first count (e.g. only 13.3 per cent of elected candidates in the 2016 general election did). Accordingly, lower order preferences are vital in determining the eventual destination of most parliamentary seats.Footnote7

The Irish case has significant advantages that we leverage for our study, but also offers insights that are of broader applicability. First, while STV is not common, it is employed in a number of contexts beyond the Irish case.Footnote8 Second, given the greater complexity of the system (arising primarily out of the capacity to award multiple preferences and do so across party lists), the theory and analysis offered in this paper provides a useful template to extend research of this type to other multiparty European contexts. The structure of the political and electoral systems in Ireland, combined with the propensity for some of its larger parties to engage in negative campaigning, make it an ideal context in which to run our survey experiment. What our survey is, however, unable to account for are intra-party competition dynamics. This would have added an additional level of complexity to the experiment which is beyond the objectives of our research question. Nevertheless, one should be aware that, in ranking candidates, the Irish electorate is to some extent also influenced by intra-party competition within the constituency.

There are additional reasons that make Ireland an interesting case for the study of negative campaigning. The importance of political campaigns and access to campaign resources have been well-established in the context of Irish elections (Benoit and Marsh Citation2003; Citation2008; Citation2010; Leahy Citation2021; Marsh Citation2000; Citation2004; Citation2007; Sudulich and Wall Citation2010; Citation2011). In addition, Ireland has just experienced a decade of ‘change’ elections characterized by high levels of electoral volatility and coming at the end of a long period of partisan dealignment (Cunningham and Marsh Citation2021; Gallagher Citation2021). Within this context of electoral instability¸ the prospective impact of election campaigns and political messaging increases significantly with more of the public open to changing their vote. This point is further emphasized by exit poll data showing that over 50 per cent of voters claim to have decided their vote after the beginning of the campaign in every general election since 1997 (Cunningham and Marsh Citation2021). In this volatile and competitive electoral environment, there would seem to be increased incentive for some political parties to ‘go negative’ in an effort to make gains over their political rivals.

The environment in which Irish political parties produce and distribute negative messages is very different to the USA, where negative TV ads are the norm (Belt Citation2017). The use of radio and television for political broadcasts in Ireland is greatly restricted with paid broadcasts forbidden (Sudulich and Wall Citation2011).Footnote9 Accordingly, the new and unregulated space of online social networks is providing political parties with the ability to widely circulate video content in election campaigns for the first time.

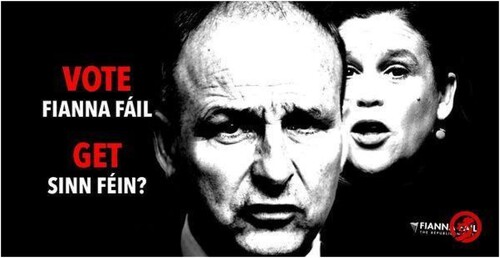

There are competing perspectives on whether Irish voters are resistant to negative campaigning but increasing evidence that Irish parties are turning towards this strategy, especially in their online messaging (McGee et al. Citation2020; Ryan Citation2020). In particular, increasing antipathy has been noted in the competing messaging of Sinn Féin and the traditionally dominant parties of Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil. Searching the Facebook ad library, which stores the social media’s paid political content,Footnote10 it is not a difficult task to find Irish examples of negative messaging ( provides an example). aligns well with negative ad types seen in the US context, i.e. the use of a black and white image starkly contrasted alongside a dark red colour in an effort to elicit a sense of fear (Brader Citation2006).

To investigate this new medium of Irish campaigning, we use videos produced by Fine Gael and Sinn Féin that engage in negative messaging as the treatment content for our survey experiment.Footnote11 These videos were simultaneously posted to both Facebook and Instagram. We use content posted on Facebook and Instagram as they are the two most used (non-messaging only) social media platforms in Ireland. A recent Irish poll showed that 66 per cent of respondents use Facebook while 55 per cent use Instagram (Reaper Citation2023).

Data and methods

Survey and survey implementation

Our survey experiment uses a within-group treatment approach to estimate the effect of negative campaign messaging on the vote intention of participants. It was conducted among 1,597 Sinn Féin and Fine Gael voters recruited by the polling company Ireland Thinks based on their vote recall for the 2020 general elections.Footnote12 The survey was in the field between 5 February and 3 May 2022. This was an off-year electorally in Ireland with no general, local, or European elections with relative stability in politics and polling support for the major parties for the first time since the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions in January 2022 (Arlow and O’ Malley Citation2024; Irish Polling Indicator Citation2024).Footnote13

In our experiment, we focus on voters of the two parties for which we design treatments. More specifically, our respondents are typical voters of Sinn Féin (SF) and Fine Gael (FG). Due to the significant number of parties represented in the Irish parliament (currently ten), our inclusion of issue variation in treatment content, and the strategy to examine destabilization, boomerang, and net effects, it was necessary to concentrate on voters from parties with theoretical significance and to recruit partisan respondents that would provide our treatment groups with adequate size and power to detect effects (Cohen Citation1988).

In addition, a consideration of campaign advertisements’ influences on partisan voters also provides a ‘hard test’ of both destabilization and boomerang effects given the effects of negative campaigning are likely to be significantly moderated by certainty of vote choice and partisanship. For example, Haselmayer, Hirsch, and Jenny (Citation2020) find that partisan respondents perceive negativity from a party they favour as less negative than non-partisans.

Sinn Féin and Fine Gael, and their supporters, are particularly suitable in terms of their significance in the current Irish political landscape. Sinn Féin, being an opposition party, should be more likely to make use of negative campaigning (Walter and van der Brug Citation2013) and these two parties currently constitute the main competing ideological poles of Irish politics. Sinn Féin, an Irish Republican and left populist party (Müller and Regan Citation2021), made very significant gains in the 2020 general election driven in particular by appealing to urban and rural working class voters (Bauluz et al. Citation2021; Cunningham and Elkink Citation2018) and have become the major challenger to Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, the two centre-right parties that have dominated Irish politics since the foundation of the state in 1922. Fine Gael has increasingly become the party representing centre-right and right voters (Müller and Regan Citation2021). According to the Irish Polling Indicator averageFootnote14 Sinn Féin and Fine Gael have consistently been the two highest polling parties since the February 2020 general election and the parties are notable for their focus on attacking each other in particular (e.g. Ryan Citation2020; McGee et al. Citation2020).

In sum, by focusing exclusively on these supporters – and excluding others – we (i) improve power in our analysis with sufficiently large treatment groups; (ii) examine differential effects of campaigning for government versus opposition parties; (iii) and finally, design a direct test of negative message effects for voters of both attacker and target. That is, we observe how supporters of both the attacker and the target react to negative messages. The advantage of this approach is that it allows for a simultaneous observation of both destabilization and boomerang effects for the attacker, which allows us to interpret a net effect of negative campaigning. While we focus on the voters of two parties to establish the effects of campaign messages, the ‘exit’ options that a multiparty system allows remain – supporters of attacking parties and targeted parties may select from the full range of alternative party (and non-party) options if the negative message influences them to do so. We therefore maintain the focus of our study on multiparty systems with multimember electoral districts.

On the other hand, this choice implies that our sample of respondents is, of course, not representative of the voting intentions of the Irish electorate. This represents one of the study’s main shortcomings. However, sample selection represents only ‘one […] of many considerations when it comes to assessing external validity’ (Druckman and Kam Citation2011, 20). Moreover, employing such a homogenous sample is only a problem for internal (rather than external) validity if a heterogeneous treatment effect is expected, that is some relatively constant factor in the sample, such as being a Fine Gael voter, is expected to moderate the effect of the treatment. We do not have reasons to expect such heterogeneous effects in either of our partisan samples given they are well balanced in terms of variables that have been shown to moderate effects in previous research (Fridkin and Kenny Citation2011, full details can be found in Appendix C). We also show that our data is similar to the Irish voting population when compared to the Irish National Election Study 2020 (Elkink and Farrell Citation2020).

Experiment design

The experiment was pre-registered at [Aspredicted.org, anonymous version in Appendix B].Footnote15 The implementation of the survey was fully managed by the polling company, who recruited respondents in three stages: stage 1 started in February 2022 (795 panellists); stage 2 in March-April (284 panellists); stage 3 in May (518 panellists). Respondents vary significantly in terms of interest in politics, engagement in political activity, and left-right self-placement (See Appendix A). The polling company carried out random assignment. Balance tests (in Appendix C) indicate randomization was successful, and we do not find reasons to believe that our analysis suffers from covariate imbalance (Hansen and Bowers Citation2008).

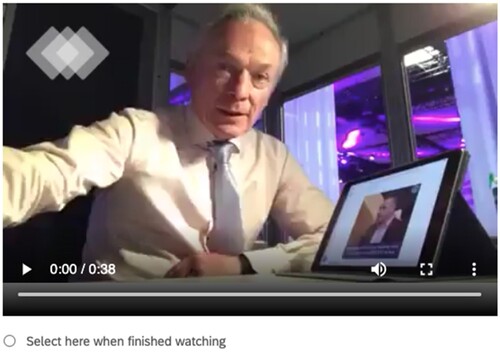

We designed the experiment around two treatment types. The first used existing short video messages taken from the Facebook/Instagram pages of both Fine Gael and Sinn Féin. These videos provide critical information about a political opponent’s policy on a salient issue in Irish politics, namely housing. The second video type attacks the integrity of a political opponent. All of these videos were a maximum of 60 s long. While we do not explicitly hypothesize differences, this twofold approach allows us to partially control for content variation, with attacks focusing either on policy or non-policy content (Chang Citation2001). By estimating effects across two distinct areas, we provide a robustness check of our findings. For each type of message, we created two experimental groups: one receiving the campaign message produced by Fine Gael attacking Sinn Féin; the second receiving a message produced by Sinn Féin attacking Fine Gael. shows one of the treatments where the producer of the message was Fine Gael and the content of the message attacked Sinn Féin on its housing policy (all material concerning the treatment in Appendix D).

Figure 2. Example of text and treatment design (housing policy treatment, message from Fine Gael attacking Sinn Féin).

Note: This part of the survey concerns electoral politics and political campaigning. Specifically, we are interested in how well people pay attention to information when it is communicated. We ask you to read two short Facebook posts, one from an Independent Councillor and one about an environmental campaign in support of reforestation. We also ask you to watch a short video (less than 1 min) published by Fine Gael on Facebook. Please pay careful attention, you will be asked to answer a short set of questions after.

We use a within-case design to compare respondents voting intention preference which we record before and after the treatment. Pre-test/post-test designs provide significant advantages in their ability to precisely detect smaller treatment effects with similar respondent pools (Clifford, Sheagley, and Piston Citation2021). To obscure the treatment, we accompany political messages with a short Facebook post published by a local politician on registering to vote for local elections (the Independent Councillor mentioned in the vignette in , full description in Appendix D), and a short message about environmental policy (the message about deforestation in the vignette of , full description in Appendix D).

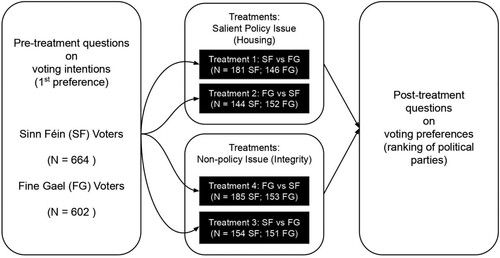

Each of the treatment groups were presented with a negative campaign message produced by one party in which they attack the other party. summarizes the number of participants organized by voting intentions for each treatment group (FG vs. SF and SF vs FG) assigned to each type of treatment (Housing and Integrity). As seen in , an approximately similar number of FG and SF voters is assigned to each treatment group and message type. As mentioned already, this allows us to simultaneously (but separately) observe destabilization and boomerang effects.

Figure 3. Experiment flow chart.

Note: These figures include a number of observations that are dropped for analysis due to various concerns. See results section for full details.

While the content and issue frame of the negative message was different (i.e. focusing on policy issues and integrity questions separately), these treatments constitute sub-types of the broader category of negative messages which are often used concurrently by parties in the real-world. Our choice of treatment design is based on striking the balance between experimental and mundane realism, that is the extent to which the treatments are realistic and are likely to be experienced in the real world (Aronson, Brewer, and Carlsmith Citation1985; Kinder and Palfrey Citation1993). If participants were to experience the treatment differently than other target groups, this would invalidate the generalisability of our results. However, our treatments are Facebook/Instagram videos, visible and accessible to a heterogenous population with relatively similar likelihood of encountering the message.Footnote16 In this way, we draw on the techniques of content creation and communication strategies employed by parties themselves in seeking to message to voters on these platforms. This means that while there are differences in message length and language employed as these vary in the real world, these treatments offer us a best initial assessment of the influence of these parties’ actual messaging strategies in real world multiparty elections. An obvious downside of having such differences is that levels of negativity or other aspects of the message are not exactly the same, making it difficult for the research to pinpoint which element of the ad causes the observed effect in the participant. The balance between internal and external validity in such experiments is the researcher’s crux in treatment design.

We also utilize the format of online social media political messages to hue as close as possible to how these materials are actually encountered by citizens. As we seek to make generalizable inferences about the effects of negative messages, approximating the messages that campaign strategists produce and employ is preferable.

To address possible memory effects induced for participants that may have seen these or very similar messages in the past and to address issues of potential fatigue with extended treatments, we edit the original video messages for length with the aim of reducing the chances that they would distort the participant’s reactions or incentivise box-ticking behaviour (e.g. Alvarez et al. Citation2019). We also include attention check questions post-treatment to ensure respondents effectively engaged with the survey. The attentiveness rate in our participant pool is strong (2.7 per cent of participants failed the attention check) and our results are not dependent on filtering out of the very small set of respondents who failed to correctly answer the attention checks (see Appendix E). Additionally, our results are robust to the exclusion of respondents that completed the survey either very quickly or very slowly (see Appendix E).

Dependent variable

In our pre-registration, we list four post-treatment questions for which we formulate hypotheses on the effect of negative campaigning. In this study, we focus on the change in voting intentions as our dependent variable. To construct this variable, we rely on two survey items. The first is a post-treatment question, which replicates a voting ballot under STV, where respondents could rank political parties by casting a minimum of 1 and maximum of 9 preferences. From this, we subtract first vote preferences collected through a survey item before the treatment. As such, our dependent variable represents change in voting intentions between pre – and post-treatment, and varies from 0 (meaning a party has retained the first preference of the respondent) to – 8 (meaning a party has dropped to being ranked last by the respondent).Footnote17 For example, participant X chooses Sinn Féin as their first preference in the first vote intention question before being assigned to the treatment. They are then shown an anti-Sinn Féin message. Subsequently, they choose Sinn Féin as their fourth preference in the post-treatment vote intention question. In this case, we would subtract one from four to provide a value of minus three. This corresponds to the fact that Sinn Féin has fallen three places in the participant’s list of preferences. Values of 0 indicate no change, while if the participant chooses not to give a party any preference after earlier giving them a first preference, we assign a value of minus eight. Nine is the lowest preference possible in the question asked and this allows us to estimate an effect from the missing value.Footnote18

Within our design, we use only respondents that gave a first preference to either Fine Gael or Sinn Féin in the pre-treatment section of our survey. As respondents were recruited with the aim of finding Fine Gael and Sinn Féin voters (due to the logistical challenges posed by multiparty systems outlined earlier), 97.4 per cent of our sample indicated a first preference for one of the two parties. Focusing only on these respondents has important implications for the dependent variable, i.e. it is unidirectional in that voter preference for the given party can only fall and not rise.Footnote19 This ceiling means we study voters’ downwards movements in their preferences for political parties. However, our design of the dependent variable provides a hard test of treatment effects because, by focusing only on downward trends, it benchmarks change in voting intentions to preference stability, which is the most likely outcome for the partisan participants in our experiment. A respondent’s voting preference is, in fact, much more stable than other variables that have been used in the literature such as favourability towards a party or certainty of vote intention. A respondent can quite easily indicate a decline in favourability or certainty for their preferred party after being exposed to a negative messaging treatment while still retaining the intention to vote for them. Additionally, by not looking at lower preferences, it is likely that we would underestimate rather than overestimate the impacts of negative messaging. Intuitively, voters would perceive the changing of lower order preferences to be less risky/costly than changing their first preference, and as already discussed, these lower preferences are often vital in deciding the allocation of seats in the Irish case (Farrell Citation2011; Gallagher and Mitchell Citation2005). As such, our dependent variable provides a conservative benchmark for the effects of negative messaging on the voting intentions of respondents.

The design of our experiment allows us to explore voting intentions ‘within-subjects’. Essentially, we take the group of participants that express a first preference choice for either Fine Gael or Sinn Féin at the beginning of the survey and that are exposed to the negative messages targeted against or employed by their preference choice (i.e. the treatment). The ‘within’ design is possible because the participants provide answers to a second question on vote intention asked after the treatment. We compare participant responses to both vote intention questions and estimate a treatment effect from this. In this design, the participant acts as their own control.

Results

Analyses were carried out using data for 1,148 valid responses from our full dataset of 1,597 participants. We removed respondents that: indicated more than one first preference post-treatment (18); indicated no first preference post-treatment (72); answered both attention check questions incorrectly (44); said that the video content failed to play (6); did not indicate a first preference for either FG or SF before the treatment (38). Finally, we dropped 271 respondents that were assigned to a control group that we employ in future analyses using between-design.

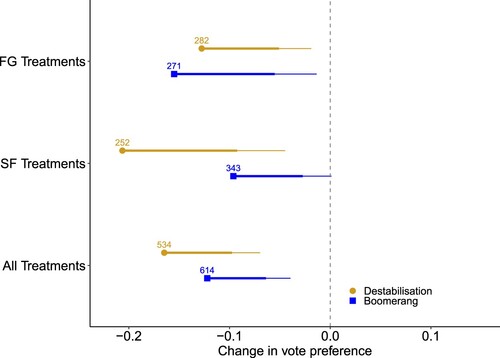

We present our key findings in and . We provide 95 and 99 per cent confidence intervals (narrow lines indicate 99 per cent CIs) and each estimate is accompanied by a figure indicating N for that subsample. Results testing H1a and H1b by means of one-sided t-tests are presented in .Footnote20 Destabilization effects (in yellow) in relate to H1a while boomerang effects (in blue) relate to H1b. ‘FG Treatments’ indicates the effect of a Fine Gael sponsored message against Sinn Féin. Conversely, ‘SF treatments’ indicates the effect of a Sinn Féin sponsored attack on Fine Gael. ‘All Treatments’ shows treatment effects when we pool voters. All six results in are statistically significant at the 0.05 level. These results suggest that negative messages trigger both destabilization and boomerang effects for a significant number of our respondents.

Figure 4. Aggregate treatment effects (Change in first preference vote).

Note: As a robustness check, within-design estimates were also calculated using Wilcoxon signed rank tests. All results were statistically significant at the 0.05 level using this approach. Results presented here are from one-sided tests. The point estimate on the x-axis can be interpreted as the mean decline in voting preference for respondents exposed to a particular treatment, see Appendix F for descriptives on the dependent variable.

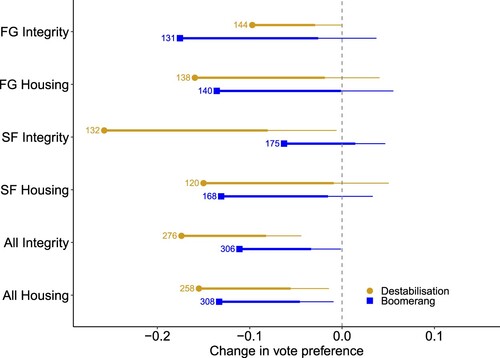

shows the same result, disaggregated by issue. ‘FG integrity’ indicates the effect of a Fine Gael sponsored message on integrity against Sinn Féin. Conversely, ‘SF housing’ indicates the effect of a Sinn Féin sponsored attack on Fine Gael housing policy.

Figure 5. Treatment effects (Change in first preference vote).

Note: Estimates were also calculated using Wilcoxon signed rank tests. All results were statistically significant at the 0.05 level using this approach. Results presented here are from one-sided tests. The point estimate on the x-axis can be interpreted as the mean decline in voting preference for respondents exposed to a particular treatment, see Appendix F for descriptives on the dependent variable.

In total, 11 out of 12 of the results in are statistically significant at the 0.05 level despite the relatively small N provided by some of our subsamples when split by party, hypothesis, and content (e.g. 131 Fine Gael voters for the estimation of boomerang effects in the integrity treatment). This adds robustness to our findings controlling for issue characteristics. Results from and suggest that exposure to negative messages can destabilize both the preferences of participants that intended to vote for the target (destabilization) and participants that intended to vote for the attacker (boomerang). These effects are consistent across issues (with the exception of ‘SF integrity’ for boomerang effects).

To add further depth to our results, we use post-treatment questions that asked respondents about their emotional responses to the treatments. We employ similar wording as used in Brader (Citation2006) and ask how the video message made the respondents feel (full details on the survey instruments can be found in Appendix E). Within our group of partisan respondents that switched their vote, 76 per cent indicated that the treatments made them feel both angry and anxious. A further 16 per cent said they felt angry only, 6 per cent indicated they felt anxious only, and six per cent said they felt neither emotion. These results align with work from other contexts showing the importance of emotional responses to negative messaging (e.g. Brader Citation2006). We also find a substantively significant difference in pre-treatment vote certainty for our vote switchers when compared with the rest of our sample, the mean for these groups was 6.15 and 8.39 respectively. This difference was statistically significant at the 0.001 level using a Welch two sample t-test. These results combined suggest that emotional response and level of vote certainty (even within a partisan sample) are key to understanding the effects of negative messaging and lend further confidence to the findings that our real-world treatments had a significant impact on respondents.

The above results show that parties fall down a voter’s preference list in a small but significant number of cases. In total, 49 respondents out of 1,148 changed their first preference vote after exposure to one of the negative messages, this constitutes 4.3 per cent of respondents. For H1a, 28 respondents out of 534 changed their vote intention (5.2 per cent) while for H1b, 21 respondents out of 614 changed their vote (3.4 per cent). These numbers seem small in real terms, but they are quite substantial given the often-tight margins by which elections are decided. For example, when looking at the final seat allocated in each constituency in the 2016 and 2020 general elections, 22 per cent were decided by approximately 1 per cent or less of the total valid votes cast in that constituency.Footnote21

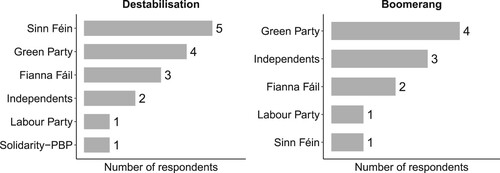

Interestingly, supporters of both attacker and target react to negative ads. As both H1a and H1b are confirmed, parties benefit and lose from using this strategy. In terms of respondents that changed their first preference vote, Fine Gael destabilized the preferences of 11 of their own supporters and 12 Sinn Féin voters (gaining only one of these votes for themselves). Sinn Féin managed to change the votes of 16 Fine Gael voters, including five that switched directly to Sinn Féin, but also lost 10 of their own supporters. In terms of direct benefit/loss then, Fine Gael lost 11 first preference votes and gained only one while Sinn Féin lost 10 and gained five. Relatedly, each party lost one voter to the other as a result of a boomerang effect (effectively cancelling each other out). The other changed votes (41 in total) were split across five other political parties and independent candidates on the mock ballot (presented in and ). This finding aligns with Galasso, Nannicini, and Nunnari (Citation2023) in suggesting that the main beneficiaries of negative messaging in multicandidate elections may be the idle candidates (i.e. the candidates that are not involved in the negativity). While the direct net effect for Fine Gael was more punitive, it is clear that neither party could be considered a clear winner as a result of their negative messaging in this experiment. This result chimes with much of the literature and with meta-analyses such as Lau, Sigelman, and Rovner (Citation2007) by indicating that there may be little benefit to negative messaging for the attacker.

This effect is also substantial in terms of how far the parties drop down the list of preferences. For 26.5 per cent of participants (13 out of 49) that changed their vote, the parties dropped from getting a first preference to getting no preference at all. Given the importance of both first preferences and lower preferences in STV elections, this can be considered a significant impact. The mean decline in vote preference is 3.33, i.e. the parties have fallen an average of 3.33 preferences across our 49 vote switchers. Two sample t-tests indicate that this effect is consistent across parties and for both destabilization and boomerang effects. In general, the prospect that 4.3 per cent of voters could be influenced by negative messages and that 26.5 per cent of these may give no preference at all to their previously preferred party is a significant consideration in terms of our understanding of electoral outcomes, especially when we consider that winning seats under STV is often decided by a handful of votes (Gallagher et al. Citation2023). This is also a significant impact when we consider that the treatments represent just one exposure to negative messaging. During a real campaign, voters are likely to have repeated encounters with such messaging and as such, the magnitude of the effects may be significantly larger.

Additionally, our oversampling of two parties in this case means that our data represents a more partisan collection of voters than the pool of all voters. This is indicated by very high levels of pre-treatment vote certainty (mean = 8.3; sd = 2.5). Combined with the earlier discussion on how the dependent variable design creates a high bar to detect effects, it is likely that our study underestimates the impact of negative messaging in this context as we focus on these ‘hard cases’. While this will have to be tested in future research, the effects observed here may be even more significant as vote certainty decreases.

Our analysis suggests that there are substantively and statistically significant effects of negative messaging in this case. Our analysis is also robust across two distinct areas (housing and integrity) which indicates that, at least in the case we studied, content variance may not play a decisive role in moderating the messages’ effects (Chang Citation2001). Additionally, one of our issue areas (housing) is a highly salient issue in Irish politics, about which most voters already have a significant amount of information and possibly strong views (Seeberg and Nai Citation2021). As such, it is notable that negative messages on this issue area moved the vote preferences of 21 respondents (42.9 per cent of all switchers).

In terms of the direction of the switches, our results unveil interesting differences between destabilization and boomerang effects, and opposition and government parties. and display which party vote switchers have transferred their preference to after having seen a negative message. The left-hand pane of each figure shows destabilization effects, i.e. effects for voters that initially supported the attacked party but then changed their mind. The right-hand panes show boomerang effects for voters initially supporting the attacker but then changed their preference. We display Fine Gael voters in while we show Sinn Féin voters in .

As seen in , five Fine Gael voters – after seeing a Sinn Féin sponsored message attacking Fine Gael – decide to switch to Sinn Féin. This is the only major direct switch that we find in the data and may be related to the ‘cost of governing’ (Müller and Louwerse Citation2020), i.e. voters are willing to punish governing parties for perceived failures and may switch to the party that looks most likely to win the next election. Generally, destabilized switchers, especially in the case of Sinn Féin, divert their first preference towards, what are considered, naturally transferable parties (Müller and Regan Citation2021). For example, seven Sinn Féin vote switchers move their first preference to the Social Democrats. 13 Fine Gael vote switchers divert to Fianna Fáil and the Green Party, both in government with Fine Gael. A viable alternative, in the case of a non-partisan vote, is to switch to independents, chosen by 12 switchers in total. The ideological proximity of post-treatment choices to pre-treatment choices in and is a notable result. This finding lends support to the argument outlined earlier that the presence of such ideologically proximate alternatives may reduce perceived barriers for voters to change their mind and could explain a greater impact of negative messaging in this and similar contexts. Additionally, our findings demonstrate evidence that some voters switch their first preference to a party that may be considered to be in the same ‘qualitative party family’ rather than the closest one ideologically (Mendoza, Nai, and Bos Citation2024). For example, a total of five respondents switch their votes from Sinn Féin to Fianna Fáil, these parties share a similar appeal to an ideology of Irish Republicanism (Coakley et al. Citation2023), which some voters may prioritize despite the spatial distance between these parties on economic and social issues.

In general, for both destabilization and boomerang effects, we observe a drift towards ‘close’ parties, like in the case of FG voters moving towards the Greens (their current government partner). However, we also see a greater preference towards independents when looking at boomerang effects. 33 per cent of switchers in the boomerang groups choose independent candidates in comparison to 18 per cent for those in destabilization groups. This may be interpreted as a way for voters to escape ‘uncivil partisan politics’ which they associate with unpalatable inter-party attacks.

Conclusion

In our survey experiment, we conduct a novel test of the destabilization and boomerang effects of negative campaign messages on voting intentions. Our main contribution lies in testing these effects in a multiparty setting with multimember districts. Specifically, we conduct our experiment in a context where effects of negative campaigning are most likely in the aggregate, but the net impact of negative campaigning is most unpredictable. Ireland uses the Single Transferable Vote system which is conducive to inter-party and intra-party competition dynamics which potentially magnify the effect of both destabilization and boomerang effects. This is because the presence of idle candidates/parties and multiple exit options represent an ideologically proximate alternative. Voters therefore expect that their vote will matter even if they do not vote for a larger party (in contrast to systems with single-seat districts) and have greater incentives to switch as a result of negative messaging. For parties utilizing these strategies though, there is substantial uncertainty about where voters will go and whether the attackers will benefit in net terms.

By assessing destabilization and boomerang effects simultaneously, we gauge benefits and losses for the sponsor of the message and produce an evaluation of the net effect of negative campaigning. To our knowledge, this is one of the first experimental studies attempting this in the context of multimember districts. Moreover, by focusing on the electoral preferences of voters of two main parties standing at the opposite end of the political spectrum, we produce a hard test for negative messages. In other words, the results here are conservative and future studies replicating our work in different PR systems or on a broader and more ideologically proximate sample of voters might find larger effects. In general, this paper contributes to a growing body of recent work that has looked to expand this literature beyond the US context by looking at new and unstudied electoral contexts (Galasso, Nannicini, and Nunnari Citation2023), extending analysis to systems with multimember districts (Mendoza, Nai, and Bos Citation2024), and exploring important moderating factors such as partisanship (Somer-Topcu and Weitzel Citation2022).

In our experimental analysis of the effects of negative campaigning in these contexts, we provide a novel examination of the effects of real-world political messages using video content designed and used by major political parties on social media. In this way, our analysis captures concretely the communication strategies, tone, and language that parties use to attack their opponents, drawn from the platforms where these attacks take place. We can therefore infer directly about how exposure to social media messaging of this sort can shape voters’ responses. Indeed, our design provides a one-shot illustration of effect patterns that likely accumulate through repeated exposure on social media.

Our results find strong evidence of both destabilization and boomerang effects at play across both sets of voters (FG and SF voters) and across two issues (housing and integrity). In 4.3 per cent of the cases, participants in our survey experiment change their first preference vote after being exposed to negative messages. We believe this to be a substantial effect considering elections are often won by only a handful of votes. The cases in which respondents change their vote are evenly split between instances where support for the attacked party deteriorates as a result of the message (destabilization) and instances where negativity backfires and harms the attacker (boomerang).

Most importantly, our results suggest that sponsors of negative messages have at least no net benefit from using this electoral strategy. Our findings suggest that vote switchers changed their vote preference to ideologically proximate parties or independents. Political parties tend to gain only as many votes from negative campaigning as they lose due to boomerang effects. In certain cases, such as Fine Gael in our analysis, negative campaigning may be closer to a net negative as boomerang effects can outweigh gains. With this in mind, it should be asked if parties are making strategic errors by engaging in negative messaging battles in multiparty systems with multimember districts. We believe this is an important question given that our results relate to a partisan sample with high pre-treatment certainty, and that they relate to a single treatment intervention. On the one hand, in a context of higher uncertainty and where messages are likely to be reinforced over time during a campaign, the effects found here are likely to be larger. On the other hand, messages in our experiment are experienced in a vacuum but would likely trigger a rebuttal or counter-attack in a real-life campaign. Despite these limits to the external validity of our experimental setting, we believe our results offer important insights for scholars of elections and public opinions as well as electoral strategists of political parties. What our study could not consider (among other things) is the extent to which negative messages demobilizes voters, whether negative messages on social media such as Facebook/Instagram impact voters differently than on other media, or whether the fact that our treatment was a video message as opposed to a printed material influenced respondents’ attitudes. On the latter, the specific use of language, tone or facial expressions could potentially play a role we could not account for.

Another limitation of our study relates to our research design choice to consider only stability and downwards trends in the ranking of preferences after exposure to negative campaigning. It is of course theoretically possible in STV, that voters bump up the attacker in the ranking of preferences, if they, for example, agree with the message and the aggressive tone. Likewise, voters may sympathize with the target and decide to place them higher in the ranking of the preferences. The operationalization of our dependent variable, as well as our focus on partisan participants who indicated either party as their first preferences, makes it impossible for us to observe such hypothetical positive trends. While we see this as a hard test of negative campaigning effects by benchmarking to preference stability, we encourage future researchers to consider this and to expand the number of participants to broader categories of voters in order to do so.

Finally, while our study unveils interesting dynamics around the effect of negative campaigns in multiparty and multimember district systems for both attackers and targets, it could not fully consider all complexities related to STV. We welcome studies that theorize further about the effects of negative campaign messages on the precise position of different parties in the ranking of preferences, as well as possible effects on intra-party competition that STV promotes. We believe these to be avenues of future research that could advance our understanding of the role of negative campaigning in contemporary democracies.

Ethical approval

This research was granted ethical approval by Trinity College Dublin and Queen’s University Belfast.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (42.4 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors are happy to make data available for an online appendix to accompany the published manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For current polling, see pollingindicator.com.

2 Studies like Mutz (Citation2015) have gone as far as analysing the effects of negative TV debates with close-up shots.

3 Scotland uses the Additional Members System whereby 57 per cent of seats are assigned via plurality.

4 See Haselmayer, Hirsch, and Jenny (Citation2020) for experimental work on the perception of negativity rather than its effects.

5 For example, it is possible to vote for Fine Gael with your first preference, Sinn Féin with your second preference, Fine Gael with your third preference and so on. This flexibility is not available in other list systems where you can give preferences only within a party list.

6 Our theoretical framework, hypotheses, and experimental design were pre-registered with aspredicted.org.

7 For more detailed information on PR-STV see Gallagher and Mitchell (Citation2005) and Farrell (Citation2011). We focus on the Irish context as an example of a system with multiparty competition in multimember districts rather than on the specifics of PR-STV in developing and testing our theory. We do not develop theoretical expectations specific to the mechanics of voting under PR-STV here as these were not pre-registered.

8 STV is used for national elections in Australia and Malta, and sub-national elections in the UK (e.g. Scottish councils), Australia (e.g. New South Wales legislature), New Zealand (e.g. Wellington City Council), and at various levels in the USA (e.g. 2024 City Council elections in Portland, Oregon).

9 Party political broadcasts are permitted during election periods provided they are equitably allocated and broadcast at similar times. These cannot be paid-for as paid political advertising is prohibited (BAI, Citation2018).

10 See https://www.facebook.com/ads/library/?active_status=all&ad_type=political_and_issue_ads&country=GB&media_type=all, last access February 21, 2023.

11 One of the housing treatment videos is a contrast message as there are some elements highlighting positive features of the attacker. This makes it slightly different than the other videos used. It was chosen because it closely hues to the parallel housing video in the terms of content and timing. We discuss the benefits and limitations of variation between real world treatments later in the paper.

12 We piloted this design with two survey experiments run with a total of 285 students enrolled in at two universities (omitted university name). The pilot and the experiment were approved by the research ethics committees of (omitted names of universities).

13 Running an experiment during an off-year has some disadvantages, related to the possibility of exaggerating the impact of negative campaigning due to atypical voter engagement, heightened reactions of participants due to limited exposure to electoral material, and a lack of comparative exposure outside the experiment’s context. These potential biases limit the external validity of the study but pose no concern to the internal validity of the experiment, which is of greater importance for this study.

14 See pollingindicator.com.

15 We pre-registered a higher number of hypotheses than we discuss in this paper. For clarity, the analysis in this paper aligns fully with the pre-registration document with one exception. This deviation is the addition of a secondary hypothesis (H1b). H1b is the inverse of the hypothesis listed as H1 in the pre-registration document and H1a in this paper. While pre-registered, our experiment did not include a ‘positive message’ for reasons related to cost-efficiency of implementing the experiment (see pre-registration document in Appendix B).

16 A potential concern for external validity is that these videos may not be encountered by both audiences of interest (i.e. people supportive of the attacking party and those supportive of the target). However, we have chosen videos that were posted on the party’s pages, this means they can’t be micro-targeted in the way that paid-for advertisements can. While the parties will tailor content for a target audience in many cases, they have no control over the diffusion of this content once it has been posted. The potential for users to share these posts and their simultaneous distribution on two platforms that have different demographic user profiles reduces this concern. Finally, these videos garnered a large number of views/shares (relative to the size of the Irish electorate) and as such, are almost certain to have reached heterogeneous audiences. We provide more details on this issue in Appendix F.

17 We also run our analysis using a binary dependent variable that is equal to one if a respondent changes their vote intention post-treatment and zero otherwise. Our findings are unchanged, see Appendix E.

18 This approach provides a conservative estimate of the treatment effect. In reality, the party has dropped further than ninth preference as they receive no preference at all.

19 See Appendix F for dependent variable descriptives.

20 We employ one-sided t-tests to account for the unidirectional design of the dependent variable.

21 This amounts to 17 seats out of 79. The median value for this measure is approximately 2.2 per cent, meaning that half of final seats allocated in these two elections were decided by 2.2 per cent or less of the valid votes cast in the constituency. Additionally, by looking only at the final count, we are not accounting for the marginality of votes in all preceding counts. To further illustrate, 4.3 per cent of Fine Gael and Sinn Féin voters at the 2020 general election would equate to approximately 43,000 individuals switching their first preference.

References

- Alvarez, R. M., L. R. Atkeson, I. Levin, and Y. Li. 2019. “Paying Attention to Inattentive Survey Respondents.” Political Analysis 27 (2): 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.57

- Ansolabehere, S., S. Iyengar, A. Simon, and N. Valentino. 1994. “Does Attack Advertising Demobilize the Electorate?” American Political Science Review 88 (4): 829–838. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082710

- Arlow, J, and E O'Malley. 2024. “Ireland: Political Developments and Data in 2023.” European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/2047-8852.12457

- Aronson, E., M. B. Brewer, and J. M. Carlsmith. 1985. “Experimentation in Social Psychology.” In Handbook of Social Psychology, 3rd ed., edited by G. Lindzey, and E. Aronson, 99–142. New York: Random House.

- Banda, K. K., and J. H. Windett. 2016. “Negative Advertising and the Dynamics of Candidate Support.” Political Behavior 38 (3): 747–766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9336-x

- Bauluz, L., A. Gethin, C. Martinez-Toledano, and M. Morgan. 2021. “Historical Political Cleavages and Post-Crisis Transformations in Italy, Spain, Portugal and Ireland, 1953–2020.” https://shs.hal.science/halshs-03131155/.

- Belt, T. L. 2017. “Negative Advertising.” In Routledge Handbook of Political Advertising, edited by C. Holtz-Bacha and M. R. Just, 49–60. New York: Routledge.

- Benoit, K., and M. Marsh. 2003. “For a few Euros More: Campaign Spending Effects in the Irish Local Elections of 1999.” Party Politics 9 (5): 561–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688030095003

- Benoit, K., and M. Marsh. 2008. “The Campaign Value of Incumbency: A New Solution to the Puzzle of Less Effective Incumbent Spending.” American Journal of Political Science 52 (4): 874–890. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00348.x

- Benoit, K., and M. Marsh. 2010. “Incumbent and Challenger Campaign Spending Effects in Proportional Electoral Systems: The Irish Elections of 2002.” Political Research Quarterly 63 (1): 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912908325081

- Brader, T. 2006. Campaigning for Hearts and Minds: How Emotional Appeals in Political Ads Work. 1st ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Broadcasting Association of Ireland. 2018. Rule 27 Guidelines: Guidelines for Coverage of General, Presidential, Seanad, Local and European Elections.

- Brooks, D. J., and J. G. Geer. 2007. “Beyond Negativity: The Effects of Incivility on the Electorate.” American Journal of Political Science 51 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00233.x

- Carraro, L., and L. Castelli. 2010. “The Implicit and Explicit Effects of Negative Political Campaigns: Is the Source Really Blamed?” Political Psychology 31 (4): 617–645. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00771.x

- Carraro, L., B. Gawronski, and L. Castelli. 2010. “Losing on all Fronts: The Effects of Negative Versus Positive Person-Based Campaigns on Implicit and Explicit Evaluations of Political Candidates.” British Journal of Social Psychology 49 (3): 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466609X468042

- Chang, C. 2001. “The Impacts of Emotion Elicited by Print Political Advertising on Candidate Evaluation.” Media Psychology 3 (2): 91–118. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0302_01

- Clifford, S., G. Sheagley, and S. Piston. 2021. “Increasing Precision Without Altering Treatment Effects: Repeated Measures Designs in Survey Experiments.” American Political Science Review 115 (3): 1048–1065. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000241

- Coakley, J., M. Gallagher, E. O' Malley, and T. Reidy. 2023. “The Context of Irish Politics.” In Politics in the Republic of Ireland, edited by J. Coakley, M. Gallagher, E. O' Malley, and T. Reidy, 1–94. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge.

- Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cunningham, K., and J. A. Elkink. 2018. “Ideological Dimensions in the 2016 Elections.” In The Post-crisis Irish Voter: Voting Behaviour in the Irish 2016 General Election, edited by M. Marsh, D.M. Farrell, and T. Reidy, 33–62. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Cunningham, K., and M. Marsh. 2021. “Voting Behaviour: The Sinn Féin Election.” In How Ireland Voted 2020: The End of an Era, edited by M. Gallagher, M. Marsh, and T. Reidy, 219–254. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- De Nooy, W., and J. Kleinnijenhuis. 2015. “Attack, Support, and Coalitions in a Multiparty System: Understanding Negative Campaigning in a Country with a Coalition Government.” In New Perspectives on Negative Campaigning. Why Attack Politics Matter, edited by A. Nai, and A. S. Walter, 77–93. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Druckman, J. N., and C. D. Kam. 2011. “Students as Experimental Participants.” In Cambridge Handbook of Experimental Political Science, edited by J.N. Druckman, D.P. Green, J.H. Kuklinski, and A Lupia, 41–57. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Duggan, A., and C. Milazzo. 2023. “Going on the Offensive: Negative Messaging in British General Elections.” Electoral Studies 83 (102600).

- Duverger, M. 1963. Political Parties: Their Organisation and Activity in the Modern State. New York: Wiley.

- Elkink, J., and D. Farrell. 2020. “2020 UCD Online Election Poll (INES 1).” Harvard Dataverse, V4.

- Elmelund-Præstekær, C. 2008. “Negative Campaigning in a Multiparty System.” Representation 44 (1): 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344890701869082

- Elmelund-Præstekær, C. 2010. “Beyond American Negativity: Toward a General Understanding of the Determinants of Negative Campaigning.” European Political Science Review 2 (01): 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773909990269

- Farrell, D. M. 2011. Electoral Systems: A Comparative Introduction. 2nd ed. London: Red Globe Press.

- Festinger, L. 1957. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Fridkin, Kim L, and Patrick Kenney. 2011. “Variability in Citizens’ Reactions to Different Types of Negative Campaigns.” American Journal of Political Science 55 (2): 307–325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00494.x

- Galasso, V., T. Nannicini, and S. Nunnari. 2023. “Positive Spillovers from Negative Campaigning.” American Journal of Political Science 67 (1): 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12610