?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study examined the key roles, responsibilities, and skills sought when advertising for the recruitment of Applied Performance Analysts (APAs) in UK and Irish professional sports settings. Deductive and inductive content analysis of the job descriptions and personal specifications of 130 job advertisements from 2021 to 2022 across the entire APA spectrum was undertaken. This encompassed 21 different specific role titles. Despite unified advertisement formats, noticeable variations emerged regarding length and content focus, regardless of First-team or Academy positions. The findings revealed a greater focus on Sports Performance Analysis (SPA), sports, and technical expertise coupled with professional behaviours in APA advertisements, with less priority shown to relationship-building skills. First-team positions particularly requested more skill-specific analysis expertise. Academy APAs were expected to focus on collecting data, facilitating feedback, in addition to creating and approving infrastructure for various age groups. Comparatively, First-team roles involved more complex data analysis tasks, including interrogating data, trend identification, and stakeholder reporting. The analysis not only highlights role discrepancies but also serves as a potential framework for employers when creating job advertisements, assists applicants in identifying the key skills to highlight, and informs curriculum and training programmes to cover the entire APA spectrum.

1. Introduction

The continuing rapid growth of Sports Performance Analysis (SPA) is recognised as essential for coaching and player development, notably in association football (Butterworth, Citation2023; Mackenzie & Cushion, Citation2013; Sarmento et al., Citation2018; Wright et al., Citation2014). This growth has led to increased diversification in the type of data used for decision-making and the roles of Applied Performance Analysts (APAs) in directly supporting the coaching process (Hughes, Citation2004; Martin et al., Citation2023). Whilst there is an increasing body of research surrounding objective data insights and their impact on individual and team success (Memmert & Rein, Citation2018), and how SPA is perceived by coaches, players, and support staff (Andersen et al., Citation2022; Reeves & Roberts, Citation2013), there is still a lack of both theoretical and practical guidance regarding the specific roles and responsibilities of APAs.

Hughes (Citation2004) argued APAs conduct tactical, technical, and movement evaluations of individuals and/or teams, build databases and create predictive models for coaches and players to use in making future decisions. As SPA has evolved, APAs developed advanced methods to capture in-depth, in-event and post-event information, necessitating different ways of presenting this information to inform the coaching processes, which has been facilitated thanks to technological advancements (Hughes, Citation2015). Wright et al. (Citation2013) reinforced many of these crucial principles and identified additional roles and skills APAs need, such as pre-event analysis to help coaches and players identify opponent’s strengths and weaknesses. Additionally, the paper shed light on the different approaches for feeding back information (e.g. group, unit, or individual presentations), through which APAs would be required to gain knowledge of and expertise in communicating the most important performance insights gleaned from the gathered and processed data.

The International Society of Performance Analysis in Sports (ISPAS) accreditation framework attempted to summarise APA’s roles (Hughes et al., Citation2020), but it focused heavily on technical skills of data collection and analysis, neglecting the importance of intra-/inter-personal skills that are required to translate key insights (Martin et al., Citation2021). Robertson (Citation2020) reiterated this emphasising the need for more knowledge of an APA’s soft skills. Subsequently, Martin et al. (Citation2021) proposed a comprehensive framework for APA practice, encompassing five areas of expertise ((i) “Contextual Awareness”, (ii)“Building Relationships”, (iii)“Performance Analysis and Sporting Expertise”, (iv)“Technical Expertise” and (v) “Professional Behaviours”) and nine components of APA practice ((i)“Establishing Relationships and Defining Roles”, (ii)“Needs Analysis and Service Planning”, (iii)“System Design”, (iv) “Data Collection and Reliability Checking”, (v) “Data Management”, (vi) “Analysis”, (vii) “Reporting to Key Stakeholders”, (viii) “Facilitation of Feedback to Athletes” and (ix) “Service Review and Evaluation”). The framework highlights the role of an APA involves more than data per se, but also learning from data, promoting behaviour changes, enhancing decision-making, and adding valuable performance knowledge. Mulvenna (Citation2023) emphasised the framework produced by Martin et al. (Citation2021) fails to acknowledge the complex nature of the sports landscape, and the socio-political influences, affecting a true reflection of the APAs role. Despite these points, there remains no consensus on the definition, objective, critical relationships, or competencies APAs require to determine an APA and SPA success (Robertson, Citation2020; Stanway & Boardman, Citation2020; Wright et al., Citation2013). Nevertheless, Martin et al. (Citation2021) framework provides valuable insight into the roles and responsibilities of APAs’ (Mehta et al., Citation2023).

We use the term SPA to represent what Martin et al. (Citation2021) refer to as “Performance Analysis” (PA) to differentiate it from the abbreviation often used for “Physical Activity”. This initial detailed examination of an APA’s role adds valuable knowledge and understanding to the discipline of SPA, benefiting novice and experienced APAs, educators and strategic managers in sporting settings (i.e. clubs, organisations, and governing bodies). The emergence of more specialised roles and tasks within a SPA department (e.g. coach analyst, GPS analyst) (Stanway & Boardman, Citation2020) has led to ongoing debates among APAs, sports settings and educators regarding the crucial tasks, obligations, and competencies APAs require, the potential deficit in applied practice in “value capture” (Martin et al., Citation2023) and how an APA’s skill set is integrated into the high-performance sport setting (Callinan et al., Citation2023). Whilst research has started to shed light on some of the core roles, responsibilities and skills required of an APA, there is still no understanding of whether sports settings align job descriptions and personal specifications with the recommendations made by the researchers in the field.

In the context of job advertisements, examining them is common practice in various fields to better understand the evolving requirements of workplace skills (Harper, Citation2012; Pitt & Mewburn, Citation2016). However, there remains limited research on how job advertisements specifically attract candidates’ interest. Petry et al. (Citation2021) highlighted that advertisements often convey conflicting messages between employers and applicants. Therefore, a close examination of how job qualities are portrayed in advertisements can provide job seekers with valuable insights into an employer’s beliefs, values, and job preferences (Guillot-Soulez et al., Citation2014).

Furthermore, job advertisements should not only provide comprehensive details about the employer but also provide information about the work culture, key objectives, job-related tasks, salary, remuneration information and opportunities for career advancement within the setting (Bernal-Turnes & Ernst, Citation2023; Ng et al., Citation2010; Petry et al., Citation2021). This comprehensive approach to job advertisements becomes particularly evident when considering a recent study of the profile of the skills, qualities, development, and career possibilities for sports scientists in Australia (Bruce et al., Citation2022). The study highlighted the expectation that future roles will require greater specialism, demanding specific technical and interpersonal skills.

This aspect is especially critical in the discipline of SPA, which has been lacking such reviews and analysis. This gap is further highlighted by the fact that popular APA posts in association football can attract over 100 candidates and these roles are progressively diversifying (Butterworth, Citation2023). As a result, the shortlisting of these roles is often a highly competitive process, with qualifications, skills, and the quantity and quality of applied experience serving as crucial criteria in the decision-making process for future APA appointments.

To address the knowledge gap in APA roles, this study examined the key roles, responsibilities, and skills sought when advertising for the recruitment of APAs in UK and Irish professional sports settings from 1st January 2021 to 31st December 2022. The insights gained from this study have the potential to assist sports settings in tailoring their advertisements to meet specific needs across the entire APA spectrum. Furthermore, the findings could offer valuable insights into the career paths taken by APAs, both in educational institutions and junior APA employment. This knowledge would potentially be instrumental in improving the recruitment process and supporting the development of future APA in SPA.

2. Methods

2.1. Job advert selection

For this exploratory study, text from 130 publicly available job advertisements was collected between 1st January 2021 to 31st December 2022. The selection of job advertisements followed a multistep process. Throughout the duration of the study, text was scraped from various websites, including thevideoanalyst.com/apfa.io, Jobs in Football, Jobs4Football, British Association for Sport and Exercise Science, UKSport, the English Football League, professional football clubs’ employment web pages and LinkedIn. Additional job advertisements were also obtained by using specific search strings through web browser search engines:

(job OR position OR post) AND (announcement OR ad OR advert OR advertisement OR description) AND (analysis OR performance analyst OR sports performance analyst). [all in the title]

To ensure a comprehensive collection of job advertisements, the researchers established automatic notifications of new job advertisements from the above-mentioned websites. Additionally, the researchers conducted manual searches at the beginning of each month to identify any job advertisements that may not have been captured through the automated notifications. Over the course of 24-months, this search process yielded 149 job adverts directly and indirectly related to APA roles within SPA. Job adverts were not considered if they did not include full-time positions within a professional sports setting where employment was within the United Kingdom or Ireland. Additionally, to ensure a sufficient sample size for analysis, a minimum of three advertisements over the two years were needed from a sport to be included in the study. These criteria reduced the list of job advertisements to 130 positions. Throughout the data collection processes, the list was continually checked to ensure content validity. Therefore, it is essential to acknowledge that our sample primarily reflects publicly advertised job opportunities across the broad spectrum of APA roles, acknowledging that other APA would have been recruited internally or without external advertisement during this time period.

2.2. Data preparation of eligible job adverts

Data from the 130 qualifying job advertisements were organised into three different tabs in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The first tab, named “Overview”, contained key information about each position including the Year, Sports Setting, Sport, Level, Specific Role Area, Gender, and Job Title, as well as information about the Frequency of Tasks/Responsibilities Requested, Frequency of Essential Components Requested, Frequency of Desirable Components Requested, and Salary Details. The second tab, labelled “Personal Specification”, comprised 1,609 rows of data. Each row represented the skill or experience requirement specified in the job advertisements. It also indicated whether the skill or experience was classified as essential or desirable for the role, along with demographic information. The third tab, named “Tasks”, contained data regarding the key tasks and responsibilities for each role. There were 1,408 rows of data, with each row representing a specified key task and demographic information about the role.

As part of the study, we were interested in exploring the differences between two generally defined APA roles: Academy and First-team. The term “Academy” was used to describe positions where more than 50% of their time was dedicated to developing athletes to compete at the highest level. Examples of roles falling under this category were “Pathway Analyst” for England Netball and distinct APA posts in academy association football related to the Foundation, Youth, and Professional Development Phases (FDP, YDP and PDP). While “First-team” referred to positions where more than 50% of the employee’s time was spent on performance-related tasks. This included positions like “Insight Analyst” at the Welsh Football Association as well as “First Team Performance Analyst” and “First Team Recruitment Analyst” in association football and “Assistant Performance Analyst” roles in rugby union. It is important to note that we identified a total of 21 different specific role title areas falling under the umbrella term of APA, in which we have referred to the spectrum of APA (see ). In some instances, “Head of Analysis” or “Lead APA”, which was featured 45 times, was used when the APA was the sole member of staff in the department, indicating a potential variation in the actual seniority of the roles represented by the title. Furthermore, our data inputting and cleaning processes revealed that leadership and management aspects were mentioned with similar frequency with “Head of Analysis”/“Lead APA” and non-head/lead roles in the tasks and personal specification sections of advertisements. Therefore, the data set contains the entire APA spectrum of roles from junior entry-level APAs through to senior APA roles, providing a balanced dataset for exploring the differences between Academy and First-team roles. The 130 job advertisements had an equal division between Academy APA roles (n = 65) and First-team APA roles (n = 65).

Table 1. Summary of specific role titles within APA advertisements.

2.3. Content categories

Content analysis of job advertisements provides a flexible method for detecting the current skill sets needed by different professions (Harper, Citation2012; Messum et al., Citation2016). This methodology involves segmenting data into linguistic units, locating specific words or phrases in the job advertisements, and providing a frequency of occurrences (Lipovac & Marina Bagić Babac, Citation2021).

In the coding process, we employed both deductive and inductive procedures (see Appendix: Code Book) to analyse the text. Initially, Martin et al. (Citation2021) framework was used to generate the codebook for the analysis and identify potentially problematic areas. The five areas of expertise were used as primary codes for analysing the content of the “Personal Specification” sheet. During the process, we encountered challenges with the “Contextual Awareness” area, ultimately deciding to align with Martin et al. (Citation2021, p. 13) comment that “contextual awareness and responding to context is the application of expertise in the other four domains”.

For the remaining four domains, we felt additional secondary codes needed to be generated to better capture the domain description from the original Martin et al. (Citation2021) paper. As a result, we generated six secondary codes under the primary code “Building Relationships”, including general relationships, sports setting staff, multidisciplinary team relationships, multidisciplinary team and external relationships, SPA-dyad relationships, and SPA-triad-parent relationships. Similarly, secondary coding was applied to the primary codes “PA and Sport Expertise”, “Technical Expertise” and “Professional Behaviours”. Each is outlined in the Code Book: 13 primary codes and 59 secondary codes.

Martin et al. (Citation2021) framework was then used to analyse the key tasks and responsibilities section of the job specification, mapping them to the nine components of APA practice. Each of the nine components was used as primary codes, and secondary codes were drawn from Martin et al. (Citation2021) “processes” columns, as presented in in her work. No additional primary or secondary codes were generated for this part of the analysis.

2.4. Procedure

The content analysis (Harper, Citation2012) process was undertaken manually by authors one and two from January to March 2023. Each task or personal specification text was assigned a single primary and secondary code using the created content categories. The primary coding for the 2021 job role data was completed by author one, while the primary coding for the 2022 job role data was completed by the second author. Following this, authors one and two collectively reviewed the primary codes together. Author one then performed the secondary coding for all the data, with author two independently cross-checking the coded data. The third author, an experienced APA and SPA researcher (10+ years) was also consulted throughout the first author’s secondary coding to gain their unbiased and unaffiliated opinions on the codes allocated. A new primary code labelled “Other” was introduced to the “Personal Specification” sheet to encompass details such as driving, language proficiency, location, and visa requirements. All three authors engaged in discussions and reached a consensus on all the primary and secondary coded data, ensuring a collaborative and thorough content analysis of the job advertisements.

2.5. Data analysis

Total frequency counts were calculated for each primary and secondary category code to explore the specific research aim and examine the overall distribution of codes across the dataset. Pearson’s Chi-square analysis and Crammer’s V (φc) analysis were also carried out to determine if there was a statically significant association between each of the primary and secondary codes, and “Level”. Additional descriptive data was generated relating to the sport, number of roles, “Level”, and means and standard deviations for the number of tasks or responsibilities requested, along with the number of essential and desirable characteristics. For data analysis and visualisation, the following packages in RStudio (2023.03.1 + 446) were used: GGplot2 (Wickham et al., Citation2023), Tidyr (Wickham et al., Citation2023), VCD (Meyer et al., Citation2023), and WordCloud (Fellows, Citation2018). All statistical tests were conducted at the 5% level of significance.

3. Results

3.1. General observations

During the two-year period, 65 Academy and 65 First-team job advertisements were obtained and analysed. These advertisements were for a total of 75 different sports settings posted openings (see ). Most recruiters advertised on one (n: 43) or two occasions (n:19) over the 24 months. Some sports settings advertised more frequently, with Swansea City AFC (Academy: 4; First-team: 2) and Reading FC (Academy: 5) being notable examples. Association Football APA positions dominated the data (n: 115; Academy: 59; First-team: 56), followed by smaller numbers in Cricket (n: 3; First-team: 3), Netball (n: 3; Academy: 1; First-team: 2) and Rugby Union (n: 9; Academy: 5; First-team: 4) (see ).

Figure 1. Word cloud summarising the frequencies of sporting organisations advertising APA roles (the larger the text, the higher the frequency count).

Table 2. Summary of general observations within APA advertisements.

The advertisements generally followed a default structure. They began with a summary of the sports settings and a key description of the job, often referred to as “Job Purpose”. This initial section often provided a suitable insight into the sports settings’ values, but not necessarily the specific SPA department or their SPA values. Several sub-sections followed, addressing the specific tasks or responsibilities expected of the successful applicant, as well as the skills and experience the recruiters were seeking. It is important to note the length and content of these sections differed greatly across our sample.

Within the sample, Academy APA roles typically had a larger number of tasks or responsibilities to cover compared to First-team, except for Cricket APA advertisements. For example, Aston Villa FC, Swansea FC, and Munster RFC had over 20 job responsibilities or tasks in their Academy advertisements (see Supplementary Data File). Furthermore, the personal specification section for Academy positions also tended to list a higher number of essential criteria that applicants must demonstrate, except for Rugby Union and Cricket.

A total of 23 of the 130 advertisements displayed any financial details. In the case of 15 Academy roles, salaries ranged from £15,000 to £29,000. The highest salary was attributed to a role involving leading the SPA provision for a Category One Football Academy, whilst the lowest salaried role was with Rugby Union overseeing the development of players across different age groups within a Premiership Rugby Academy. In contrast, eight First-team roles disclosed salary information ranging from £18,000 to £30,000. The lowest salary was advertised by a team competing in League One of the English Football League whilst the highest salary was offered by a team in League Two. Interestingly, there was no mention within any advertisement regarding career progression.

3.2. Personal specification observations

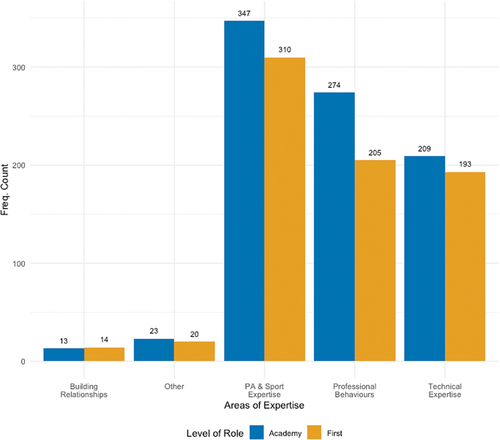

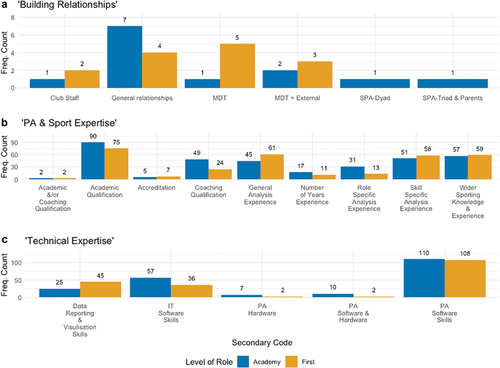

Analysis of the personal requirements in job advertisements show “PA and Sport Expertise”, “Technical Expertise”, and “Professional Behaviours” were requested more frequently than “Building Relationships”, regardless of job level (see ). Notably, the job advertisements for Academy positions emphasised “PA and Sport Expertise”, “Technical Expertise”, and “Professional Behaviours” to a greater extent than First-team roles. First-team roles requested more specific relationship expertise and experience at a higher frequency than Academy roles (see ). However, this area of expertise only featured 27 times in the 130 job advertisements.

Figure 3. Sub-areas of expertise (a: ‘building relationships, b: “PA & sport expertise” and c: “technical expertise”) underpinning APA against role level.

In the “PA and Sport Expertise” category, academic qualifications were frequently requested, with Academy roles often requiring them significantly more often than First-team roles ( (8, N = 657) = 19.786, p = 0.011, V = 0.174) (see ). It is worth noting that an undergraduate qualification is often an essential requirement (Academy: 48; First-team: 43), while only nine job advertisements listed it as desirable (Academy: 3; First-team: 6). Additionally, post-graduate qualifications, UEFA B licences or Level 2 coaching qualifications were more frequently requested for Academy roles compared to First-team roles (Academy: 91 – Essential: 17; Desirable: 74; First-team: 50 – Essential: 6; Desirable: 44). First-team advertisements typically requested general experience or skill-specific experience. In contrast, Academy advertisements typically sought role-specific experience working with specific age groups.

Significant differences were observed in the “Technical Expertise” category based on role level, with varying skill and knowledge requirements ( (4, N = 402) = 17.977, p < .001, V = 0.211) (see ). First-team roles requested “Data Reporting and Visualisation Skills” more frequently (Academy: 25; First-team: 45), whereas Academy roles emphasised “IT Software Skills” (Academy: 57; First-team: 36). “PA Software Skills” were commonly requested, with advertisements often referring to industry-standard SPA software. In some cases, advertisements made specific references to specific software: data capturing software (e.g. Hudl SportsCode, SBG Focus, Fulcrum Angles, NacSport) and handling and visualising software (Excel, Numbers, Tableau, PowerBI, Hudl Studio, Coach Paint, Piero, iMovie, Final Cut, R, Python).

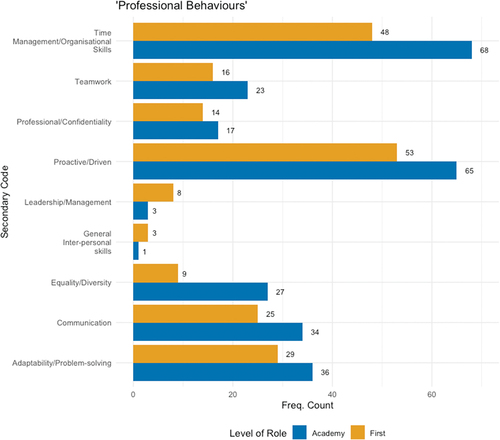

“Professional Behaviours” were frequently mentioned in job advertisements, with attributes such as being proactive, having good time-management skills, and effective communication being highly requested (see ). Noticeably, Academy positions placed a stronger emphasis on “Professional Behaviours”, except leadership qualities which were sought more frequently in First-team advertisements.

3.3. Tasks and responsibilities observations

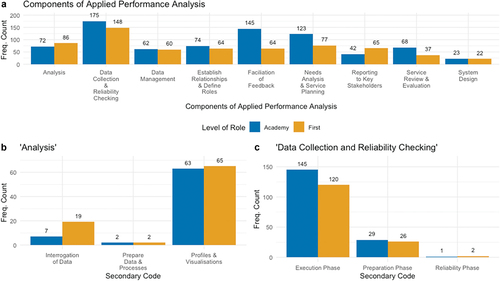

In the tasks and responsibilities sections, significant differences between Academy and First-team roles were identified ( (8, N = 1407) = 42.235, p < .001, V = 0.173) (see ). “Data collection and reliability checking” was the most frequently requested component, with Academy roles placing a higher emphasis (Academy: 175; First-team: 148). Academy positions requested “Facilitation of Feedback” (Academy: 145; First-team: 64) and “Needs Analysis and Service Planning” (Academy: 123; First-team: 77) more frequently than First-team roles. In contrast, “Analysis” and “Reporting to Key Stakeholders” were more frequently requested in First-team advertisements.

Figure 5. Components of APA practice (a) and sub-components of APA practice (b: “analysis” and c: “data collection and reliability checking”) against role level.

In the “Analysis” category, there were minimal numerical differences in the task of creating “Profiles and Visualisations” (Academy: 63; First-team: 65) (see ), while “Interrogation of Data” more frequently in First-team roles (Academy: 7; First-team: 19).

The “Execution Phase” was the most frequently requested task in the “Data Collection and Reliability” category (see ); particularly in Academy advertisements (Academy: 145; First-team: 120). It’s noteworthy, the “Reliability Phase” only appeared in three advertisements.

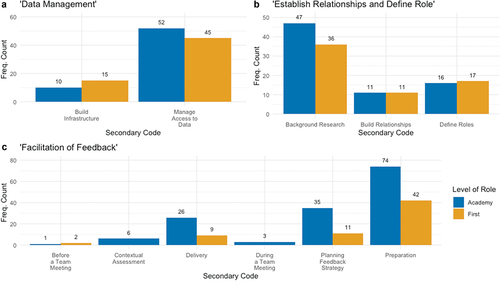

In the “Data Management” component (see ), Academy roles showed a higher frequency of requests for tasks related to “Manage Access to Data” (Academy: 52; First-team: 45), while First-team roles requested “Build Infrastructure” (Academy: 10; First-team: 15) tasks more frequently than Academy roles.

Figure 6. Sub-components of APA practice (a: “data management”, b: “establishing relationships and define role” and c: “facilitation of feedback”) against role level.

Tasks related to “Build Relationships” and “Define Roles” within the “Establish Relationships and Define Roles” component showed low-frequency counts and no notable differences (see ). “Background Research” was more frequently requested in Academy advertisements (Academy: 47; First-team: 36).

Academy advertisements emphasised tasks related to “Facilitation of Feedback” (see ); including “Planning Feedback Strategy” (Academy: 74; First-team: 42) and “Preparation” (Academy: 35; First-team: 11) of feedback. Despite being more frequently stated as a role in Academy advertisements, the “Delivery” of feedback (Academy: 26; First-team: 9) was not seen as an APA task in most advertisements.

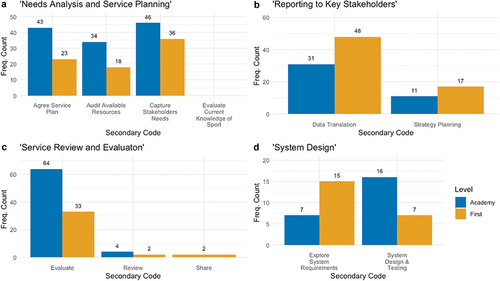

Within the “Needs Analysis and Service Planning” component (see ), Academy advertisements more frequently requested tasks related to “Agree Service Plan”, “Audit Available Resources” and “Capture Stakeholders Needs”.

Figure 7. Sub-components of APA practice (a: “needs analysis and service planning”, b: “reporting to key stakeholders”, c: “service review and evaluation” and d: “system design”) against role level.

First-team job advertisements placed a greater emphasis on “Reporting to Key Stakeholders” (see ), in particular, “Data Translation” (Academy: 31; First-team: 48) tasks were requested at higher frequencies.

The “Service Review and Evaluation” component was more prominent in Academy advertisements, particularly “Evaluate SPA Provisions” (Academy: 64; First-team: 33) (see ). The tasks of “Review” and “Share” recorded lower frequency counts, indicating less focus on formally capturing feedback and sharing practice, and a greater focus on APA reflecting on delivery in both roles.

The “System Design” component revealed significant differences between Academy and First-team roles ( (1, N = 45) = 6.412, p = .011, V = 0.377) (see ). First-team job advertisements emphasised “Explore System Requirements” (Academy: 7; First-team: 15), whereas “System Design and Testing” was mentioned more frequently in Academy advertisements (Academy: 16; First-team: 7).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the key roles, responsibilities, and skills sought when advertising for the recruitment of Applied Performance Analysts (APAs) in UK and Irish professional sports settings from 1st January 2021 to 31st December 2022. Our analysis encompassed APAs at all levels of the spectrum, ensuring a holistic view of the field. Despite variations in the quality and quantity of the content in the analysed job advertisements, our study identified distinct role and responsibility differences within the profession. By applying Martin et al. (Citation2021) framework, we have started to build an understanding of the similarities and differences recruiters seek when advertising for Academy APAs or First-team APAs.

4.1. Variations in job advertisements

Association football emerged as the dominant sport in terms of the number of roles, with the largest variations in content. The volume of roles in association football can be attributed to the Elite Player Performance Plan (EPPP) (Premier League, Citation2021), which outlines standards for SPA and APA within club academies to aid player development. However, Hounsell et al. (Citation2021) highlighted that Academy APAs juggle complex priorities over the use of SPA. In some instances, SPA is employed as a tool to solely enhance team performance, often taking precedence over the developmental aspects highlighted in the EPPP. This accentuates the significant role of comprehensive job profiles and frameworks within the industry.

Advertisements related to association football displayed the most substantial fluctuations in the number of requirements within tasks or personal specification sections, with wording varying significantly, from 4 or 5-word task descriptions to detailed 20+ word sentences explaining sports setting-specific tasks tailored to their language. In contrast, we observed more specific and detailed job advertisements by England Netball, supported by the England Institute of Sport (Citation2015) (now UK Sports Institute). This serves as a prime example of such a framework, clearly outlining role and responsibilities expectations associated with various salary scales. This comprehensive job profile, utilised across various sports sciences disciplines, including APA, plays a pivotal role in ensuring role clarity and enhancing the perceived value of the role of the APA position (Martin et al., Citation2023).

Given the absence of a widely adopted framework in APA, delineating the roles and responsibilities, coupled with a lack of professional regulation governing these duties and their associated salary scales, it is unsurprising that only 23 out of the 130 job advertisements analysed included payment information. This omission potentially reflects an underappreciation of the “value” of an APA, as suggested by Butterworth (Citation2023), Dickey et al. (Citation2022) and Martin et al. (Citation2021). It is crucial, however, to recognise that the advertised pay level constitutes a pivotal aspect in job advertisements due to its profound impact on prospective applications (Petry et al., Citation2021). Moreover, providing actual pay ranges has been found to be the most substantial advantage of salary information (Verwaeren et al., Citation2017).

Applicants often perceive base pay as a crucial insight into other symbolic attributes related to the job (Muskat & Reitsamer, Citation2020), including the potential for career progression. Notably, the absence of career progression information in all advertisements has profound implications. The inclusion of specific career progression details not only assists job seekers in making informed decisions but also contributes to the professionalisation of SPA and the role of the APA. This practice communicates the value the sports setting places on the growth and development of their APAs. However, when this information is omitted, it leaves potential applicants uncertain of how and where they could develop their skills and expertise within their role as an APA. This ambiguity is particularly concerning given the widespread perception that many Academy APA roles are considered entry-level positions despite being requested to have more skills and tasks than First-team roles.

This absence of clarity, regarding what sports settings are seeking and expertise along with what they are offering in terms of compensation and career growth, is noticeable within the field of APA, particularly in sports such as association football. It underscores the pressing need for stronger regulation and industry standards for practitioners (Martin et al., Citation2023). Here, professional organisations including the International Society of Performance Analysis in Sport (ISPAS), the British Association of Sport and Exercise Science (BASES), the UK Institute of Sport, and the Football Association could play a pivotal role.

A potential starting point could be the development and dissemination of “standardised” job profiles, establishing a common language and remuneration based on the necessary skills and competencies, similar to those used by the UK Sports Institute. These findings shed light on the need to address this critical gap and explore the potential impact of including specific salary information in job advertisements within the sports industry based on role tasks and expertise. To truly appreciate and value the contribution of APA, sports organisations must gain a comprehensive understanding of the nature of their work, their expertise, and the associated resources needed for the quantity of SPA requested. Addressing these issues will be a significant step in acknowledging and recognising the contributions of APAs in sports settings.

4.2. Qualifications, skills, and expertise

Recruiters consistently prioritised academic and/or coaching qualifications when recruiting APAs, and these qualifications were more frequently requested in Academy APA advertisements. This emphasis is supported by Wright et al. (Citation2013), who found that 58% of the respondents held coaching qualifications, while 85% had academic qualifications. These qualifications demonstrate an APA’s expertise in technical and tactical knowledge, underlining their understanding of the coaching processes (Butterworth, Citation2023).

While qualifications are pivotal for satisfying personal specification requirements, practical experience and proficiency in SPA software are key determinants of employability (Butterworth, Citation2023). This observation aligns with the 593 mentions of experience as an APA and proficiency in SPA software, again more frequently requested in Academy APA advertisements. These skills and experiences have remained important for APAs over time (Stanway & Boardman, Citation2020). However, the discipline is witnessing the emergence of various software skills and technologies (Robertson, Citation2020; Wright et al., Citation2013), complicating the choices for both recruiters and applicants. Previously, centred on data collection (Hughes, Citation2004) APAs are now expected to “generate, curate, and translate data” (Martin et al., Citation2023, p. 12) using specific software.

This evolution leaves recruiters unsure about whether to emphasise generic or specific software skills based on the sports setting’s infrastructure. This also leaves applicants uncertain about the number of software programmes to learn to demonstrate their SPA expertise. Additionally, roles are now diversifying (Stanway & Boardman, Citation2020). This evolution has led to dedicated APAs in First-team environments, focusing on specific functions that were traditionally consolidated into a single APA’s role. They have gained access to secondary data sources and now specialise in analysing their own team’s performance, monitoring opposition, evaluating goalkeepers, scrutinising set-pieces, and accessing training (Carling, Citation2019; Stanway & Boardman, Citation2020). Consequently, this transformation has liberated APAs from arduous data collection tasks, allowing them to concentrate on interpreting the data in their area of technical or tactical expertise. This shift marks a significant contrast when comparing job advertisements for Academy roles with those of a First-team. However, academies still adhere to the historical model of SPA in which the employment of a singular APA across multiple teams, functioning without the advanced tools and resources readily available in the First-team, arguably making an Academy role more challenging.

The job specifications extracted from the advertisements referred to 479 “Professional Behaviours”. This prominent observation aligns with the growing understanding of how APAs operate within high-performance environments, effectively transmitting their obtained knowledge to aid decision-making (Bateman & Jones, Citation2019; Butterworth & Turner, Citation2014). Bampouras et al. (Citation2012) also highlighted the interdependency between APAs and coaches, whereby APAs are responsible for capturing, evaluating, and providing feedback, reinforcing the need to have a range of interpersonal skills. Similarly, McKenna et al. (Citation2018) highlighted the pivotal role of building relationships in establishing an effective SPA provision. These relationships play a constraining role, influencing and shaping all aspects of an APA’s role and responsibilities. However, Pitt and Mewburn (Citation2016) highlight these interpersonal skills have not traditionally received due attention.

Within the advertisements, it becomes evident that time management and organisation skills, along with qualities like being proactive and driven, featured more prominently in Academy positions than in First-team positions. This distinction arises from the fundamental differences between these roles. Academy APAs often work across multiple squads or focus on one squad and assist the wider Academy SPA infrastructure. In contrast, First-team environments typically involve multiple APAs dedicated to a single team. As a result, the requirements for effective time management skills become more profound for Academy APA, given the necessity to coordinate various conflicting schedules. This coordination is essential for providing coaches with the necessary information to enhance their decision-making processes.

Academy roles are often viewed as entry-level APA positions, and it is commonly expected that individuals exhibit proactive and driven characteristics. This expectation aligns with the inherent need for good time management and organisation skills. As APAs begin their careers and enter new environments, they must learn to read the landscape and adapt to the expectations and demands of their roles. To establish job security and create a positive impression, APAs often find themselves going above and beyond what is expected of them (Butterworth & Turner, Citation2014; McKenna et al., Citation2018; Thompson et al., Citation2015). While these skills were more prominently requested in Academy roles, they remained a consistent theme throughout all advertisements, reinforcing the need to possess these skills in the context of high-performance sports. These demanding environments are often described as complex and somewhat messy (Wiltshire, Citation2014), making these skills invaluable in adding value as an APA. However, it is crucial to note these professional skills are not easily acquired through formal qualification programmes (Alfano & Collins, Citation2020; Butterworth, Citation2023). This emphasises the need for practical experience and on-the-job learning for the development and refinement of these essential professional skills.

4.3. Components of academy and first-team APA practice

Academy APAs were consistently tasked with “Data Collection and Reliability Checking” duties, reflecting previous research indicating their extensive involvement in filming and collecting primary data (McKenzie & Cushion, Citation2016). In contrast, First-team APAs often outsource these tasks to technology or external data providers (Robertson, Citation2020), such as Opta, StatsBomb or Wyscout. However, the reliance on external data providers, despite technological advancements, has raised questions about the quality and meaningfulness of the information provided (Worsfold & Macbeth, Citation2009). Carling (Citation2019) highlighted that even with these advancements, the challenges remain in producing meaningful and accurate information to inform practice that is aligned with the sports setting’s performance measures. Given that Academy APAs typically lack access to such advanced technology and continue to face resource constraints (Stanway & Boardman, Citation2020), the higher frequencies of “Data Collection and Reliability Checking” requests in job advertisements is unsurprising.

Interestingly, the “Reliability Phase” was rarely mentioned in job advertisements, suggesting that APAs may not consistently allocate time for data quality control. This contradicts recommendations by SPA researchers who emphasise the central importance of data validity and reliability (O’Donoghue & Hughes, Citation2020). Neglecting these crucial aspects may have a detrimental impact on the quality of data used to support vital decisions regarding tactics, match preparation and individual development, along with the value an APA can add to a sports setting.

First-team job advertisements highlighted a greater emphasis on “Analysis” and “Reporting to Key Stakeholders”. Wright et al. (Citation2013) and Callinan et al. (Citation2023) corroborated this, highlighting First-team APAs in association football dedicate over four hours per week to analysing their own team’s performance and opponents, whereas Academy APAs typically allocate up to three hours for similar tasks. First-team APAs typically engage in filtering and analysing complex metrics to communicate relevant information to key stakeholders (Wright et al., Citation2016). This critical step aids coaches in understanding what the numbers mean in a practical sense to inform strategic decisions. This pattern also emerged in the personal specification of job advertisements, where First-team advertisements more frequently emphasised “Data Reporting and Visualisation Skills”.

In contrast, Academy job advertisements placed a stronger emphasis on the role of “Facilitation of Feedback”. Academy APAs predominately are responsible for producing video compilations showcasing exemplary performances of other youth players and providing content of performance improvement (Carling, Citation2019). This emphasis on feedback and active self-reflection aligns with previous research and highlights the collaborative nature of feedback sessions involving the APA (Page, Citation2021; Stanway & Boardman, Citation2020; Wright et al., Citation2016). Importantly, the actions of delivering these insights were noted in only 35 advertisements, aligning with Wright et al. (Citation2013) findings from over a decade ago in which coaches predominantly led feedback sessions. This shift may be attributed to the increased requirements for coaching qualifications for APAs, highlighting the need for them to have coaching knowledge to lead sessions for players (Bateman & Jones, Citation2019). The analysed job advertisements support these findings, as Academy APA advertisements mentioned “Planning Feedback Strategy” and “Preparation” more frequently.

Moreover, Callinan et al. (Citation2023) highlighted that an APA’s role, regardless of the level, is responsible for using collected data to objectively interpret the game and provide information and feedback to key stakeholders. This aspect was also observed in certain job advertisements, where tasks such as “Develop and implement new strategies to enhance the player learning process” were mentioned (2022-Birmingham City FC-Women’s First Team APA). This aligns well with Martin et al. (Citation2021) perspective of APAs, where they focus on designing learning opportunities to facilitate the co-creation of knowledge, benefiting various stakeholders, and enhancing future decisions and judgements.

Expanding on this, Callinan et al. (Citation2023) emphasised the importance of establishing a strong alliance between the APA and the coach to fully maximise the potential of knowledge facilitation and its resulting benefits to stakeholders. This collaborative partnership between the APA and the coach is essential to ensuring a successful and effective support system for the players’ development, growth, and performance. While building strong relationships is crucial for maintaining effective communication, trust, and mutual understanding (Bampouras et al., Citation2012; Bateman & Jones, Citation2019), it is surprising that our analysis of the job advertisements reveals only 22 of the 130 advertisements mentioned the task of “Build Relationships”.

Sports settings might assume that APAs understand the importance of fostering positive relationships and creating a supportive environment, hence not explicitly mentioning it in the advertisements. However, tasks or responsibilities such as these should not be assumed by sports settings in advertisements (Petry et al., Citation2021; Pitt & Mewburn, Citation2016). Sports settings must acknowledge the value of this aspect in the APA’s role and actively promote the development of meaningful connections to optimise the overall coaching and SPA process. Communicating these assumed responsibilities and expectations in job advertisements is vital. Moreover, it enhances the overall efficiency of the sports setting’s recruitment process. Clear communication in job advertisements ensures alignment with the desired quality and responsibilities of prospective candidates, streamlining the selection of individuals who can contribute prospectively to the sports setting’s goals.

4.4. Limitations

Whilst our study is the first of its kind in the field of SPA, specifically concerning the role of the APA, it is important to acknowledge the limitations. We primarily analysed job advertisements in the UK and Ireland, potentially missing culturally significant aspects of APA practice in other parts of the world. However, the substantial weight of our analysis provides valuable insight into APA practice in this specific population.

Focusing solely on the comparisons between Academy against First-team job advertisements, we may have overlooked essential and desirable characteristics along with specific tasks or duties for specific role titles. There was a total of 21 different specific role titles identified, reflecting the increasing diversity of the APA’s role in the early 2020s. Future research should delve deeper into the data to examine role-specific skills and requirements, enabling a more comprehensive understanding. For instance, we did not explore roles like “Head” or “Lead”, which may involve higher levels of leadership and management compared to FDP (Foundation Development Phase) and YDP (Youth Development Phase) Academy APA. Notably, it is becoming increasingly common for APAs to be “brought in” when a new coach or a manager is appointed at an organisation, without publicly advertising the opportunities. These APAs are typically more senior, which could account for some of the observed differences. However, given that our sample included a range of junior and senior positions, we believe our study provides a realistic overview of the current landscape.

We primarily relied on Martin et al. (Citation2021) framework for our analysis, which may have limitations in capturing all nuances and dimensions of the APA role. The constant developments and variations in roles and responsibilities potentially require flexibility beyond a single deductive approach.

Our analysis was limited to the content of job advertisements, without insights from key stakeholders such as hiring managers, Human Resources professionals, and decision-makers. This omission may limit our understanding of the underlying motivations and expectations that shape the content of these advertisements.

4.5. Recommendations

Our study highlights the critical importance of clear and transparent communication in job advertisements to recognise and value the contributions of APAs, ultimately enhancing player development and team performance. To assist employers in designing effective job advertisements and developing comprehensive skills and competency training programmes for APAs, we highly recommend using the recommendations outlined in . These guidelines, inspired by concepts from the business world, emphasise the importance of providing detailed information about the sports setting, a clear description of job-related tasks, transparent information about salary and remuneration, and clear pathways for career advancement (Petry et al., Citation2021).

Table 3. Recommendations and guiding principles for organisations, applicants and employers when designing job advertisements.

Additionally, we encourage sports organisations and employers to refer to the framework developed by Martin et al. (Citation2021) as a valuable guide for creating effective job advertisements and enhancing skills and competency training programmes for APAs. These recommendations benefit not only employers but also provide valuable guidance for applicants and educational providers, contributing to the overall development of the APA role and the wider discipline of SPA. By adopting these strategies, recruiters can attract and retain talented APAs, fostering a more productive and successful environment for players and teams.

We further recommend that studies gather insights from both employers who create these advertisements for APAs and applicants who have experienced the recruitment processes. This approach enables researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the specific criteria, requirements, and expectations that sports settings prioritise when seeking APAs. Gathering insights from applicants can help identify discrepancies between employers’ preferences expressed in job advertisements and how applicants interpret and respond to them, revealing potential barriers or areas for improvement in the recruitment process. This approach leads to a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the APA job market and the factors influencing successful development of future APAs.

5. Conclusion

Our findings highlight the need for tailored job profiles and frameworks that communicate role expectations, emphasising the importance of job advertisement design. Job advertisements revealed notable differences, in particular, neglecting key APA aspects, such as intra- and inter-personal skills, along with varying length and level of detail in the advertisements’ narrative. Academy APA roles proved more demanding, encompassing a broader skill set and responsibilities. The absence of salary and career progression prospects suggests potential undervaluing of the APA position. We call upon professional organisations, academic institutions, and sports settings to establish standardised guidelines for job advertisements, including transparent salary details and career paths. Collaborative efforts are encouraged to develop comprehensive training programmes for APAs that align more closely with the skills and expertise requested in advertisements; ultimately enhancing the contributions of APAs in generating, curating, and translating insights to positively impact and inform decision-making for stakeholders.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alfano, H., & Collins, D. (2020). Good practice delivery in sport science and medicine support: Perceptions of experienced sport leaders and practitioners. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1727768

- Andersen, L. W., Francis, J. W., & Bateman, M. (2022). Danish association football coaches’ perception of performance analysis. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 22(1), 149–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2021.2012040

- Bampouras, T. M., Cronin, C., & Miller, P. K. (2012). Performance analytic processes in elite sport practice: An exploratory investigation of the perspectives of a sport scientist, coach and athlete. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 12(2), 468–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2012.11868611

- Bateman, M., & Jones, G. (2019). Strategies for maintaining the coach–analyst relationship within professional football utilizing the COMPASS model: The performance analyst’s perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(Article 2064), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02064

- Bernal-Turnes, P., & Ernst, R. (2023). More bang for your buck: Best-practice recommendations for designing, implementing, and evaluating job creation studies. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01199-8

- Bruce, L., Bellesini, K., Aisbett, B., Drinkwater, E. J., & Kremer, P. (2022). A profile of the skills, attributes, development, and employment opportunities for sport scientists in Australia. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 25(5), 419–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2021.12.009

- Butterworth, A. (2023). Professional practice in sport performance analysis. Routledge.

- Butterworth, A., & Turner, D. (2014). Becoming a performance analyst: Autoethnographic reflections on agency, and facilitated transformational growth. Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 15(5), 552–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2014.900014

- Callinan, M. J., Connor, J. D., Sinclair, W. H., Leicht, A. S., & Senel, E. (2023). Exploring rugby coaches perception and implementation of performance analytics. PLoS One, 18(1), e0280799. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280799

- Carling, C. (2019). Performance analysis: Working in football. In D. Collins, A. Cruickshank, & G. Jordet (Eds.), Routledge handbook of elite sport performance (pp. 99–114). Routledge.

- Dickey, L., Ramsey, C., Humphrey, R., Middlemas, S., Murray, E., & Spencer, K. (2022). The working conditions of performance analysts in Oceania. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 18(2), 532–538. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541221085775

- England Institute of Sport. (2015). EIS Competency Framework. England Institute of Sport.

- Fellows, I. (2018). CRAN - Package Wordcloud. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/wordcloud/

- Guillot-Soulez, C., Soulez, S., Parry, E., & Strohmeier, S., DR. (2014). On the heterogeneity of generation Y job preferences. Employee Relations, 36(4), 319–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-07-2013-0073

- Harper, R. (2012). The collection and analysis of job advertisements: A review of research methodology. Library and Information Research, 36(112), 29–54. https://doi.org/10.29173/lirg499

- Hounsell, T., Oxenham, P., & Mulvenna, C. (2021, November). The great balancing act-the art of performance analysis in academy soccer in England. Sport Performance and Science Report 149, (1), 1–3. https://sportperfsci.com/the-great-balancing-act-the-art-of-performance-analysis-in-academy-soccer-in-england/

- Hughes, M. (2004). Performance analysis – a 2004 perspective. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 4(1), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2004.11868296

- Hughes, M. (2015). An overview of the development of notational analysis. In M. Hughes & I. Franks (Eds.), The essentials of performance analysis: An introduction (2nd ed., pp. 54–88). Routledge.

- Hughes, M. T., James, N., & Hughes, M. (2020). Accreditation. In M. Hughes, I. Franks, & H. Dancs (Eds.), Essentials of performance analysis in sport (3rd ed., pp. 395–406). Routledge.

- Lipovac, I., & Marina Bagić Babac, M. (2021). Content analysis of job advertisements for identifying employability skills. Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems, 19(4), 511–525. https://doi.org/10.7906/indecs.19.4.5

- Mackenzie, R., & Cushion, C. (2013). Performance analysis in football: A critical review and implications for future research. Journal of Sport Sciences, 31(6), 639–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.746720

- Martin, D., O Donoghue, P. G., Bradley, J., & McGrath, D. (2021). Developing a framework for professional practice in applied performance analysis. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 21(6), 845–888. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2021.1951490

- Martin, D., O’Donoghue, P. G., Bradley, J., Robertson, S., & McGrath, D. (2023). Identifying the characteristics, constraints, and enablers to creating value in applied performance analysis. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541231180243

- McKenna, M., Cowan, D. T., Stevenson, D., & Baker, J. S. (2018). Neophyte experiences of football (soccer) match analysis: A multiple case study approach. Research in Sports Medicine, 26(3), 306–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438627.2018.1447473

- McKenzie, R., & Cushion, C. (2016). Player and team assessment. In T. Strudwick (Ed.), Soccer science (pp. 541–543). Human Kinetics.

- Mehta, S., Furley, P., Raabe, D., & Memmert, D. (2023). Examining how data becomes information for an upcoming opponent in football. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541231187871

- Memmert, D., & Rein, R. (2018). Match analysis, big data and tactics: Current trends in elite soccer. Deutsche Zeitschrift Fur Sportmedizin, 69(3), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.5960/dzsm.2018.322

- Messum, D., Wilkes, L., Peters, K., & Jackson, D. (2016). Content analysis of vacancy advertisements for employability skills: Challenges and opportunities for informing curriculum development. Journal of Teaching & Learning for Graduate Employability, 7(1), 72–86. https://doi.org/10.21153/jtlge2016vol7no1art582

- Meyer, D., Zeileis, A., Hornik, K., Gerber, F., & Friendly, M. (2023). CRAN - Package Vcd. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vcd/index.html

- Mulvenna, C. (2023). Identifying the characteristics, constraints and enablers to creating value in applied performance analysis: A commentary. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541231190798

- Muskat, B., & Reitsamer, B. F. (2020). Quality of work life and generation Y: How gender and organizational type moderate job satisfaction. Personnel Review, 49(1), 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2018-0448

- Ng, E. S. W., Schweitzer, L., & Lyons, S. T. (2010). New generation, great expectations: A field study of the millennial generation. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(2), 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9159-4

- O’Donoghue, P., & Hughes, M. (2020). Reliability issues in sports performance analysis. In M. Hughes, I. M. Franks, & H. Dancs (Eds.), Essentials of performance analysis in sport (3rd ed., pp. 143–160). Routledge.

- Page, T. (2021). A Critical Appraisal of Current Feedback Strategies Employed within Professional Football [ PhD Thesis].

- Petry, T., Treisch, C., & Peters, M. (2021). Designing job ads to stimulate the decision to apply: A discrete choice experiment with business students. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(15), 3019–3055. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1891112

- Pitt, R., & Mewburn, I. (2016). Academic superheroes? A critical analysis of academic job descriptions. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management, 38(1), 88–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2015.1126896

- Premier League. (2021). Elite Player Performance Plan - EPPP. https://www.premierleague.com/youth/EPPP

- Reeves, M., & Roberts, S. (2013). Perceptions of performance analysis in elite youth football. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 13(1), 200–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2013.11868642

- Robertson, P. S. (2020). Man & machine: Adaptive tools for the contemporary performance analyst. Journal of Sports Sciences, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2020.1774143

- Sarmento, H., Clemente, F. M., Araújo, D., Davids, K., McRobert, A., & Figueiredo, A. (2018). What performance analysts need to know about research trends in association football (2012–2016): A systematic review. Sports Medicine, 48(4), 799–836. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0836-6

- Stanway, B., & Boardman, P. (2020). The analysis process: Applying the theory. In E. Cope & M. Partington (Eds.), Sports coaching: A theoretical and practical guide (pp. 93–108). Routledge.

- Thompson, A., Potrac, P., & Jones, R. (2015). ‘I found out the hard way’: Micro-political workings in professional football. Sport, Education and Society, 20(8), 976–994. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2013.862786

- Verwaeren, B., Van Hoye, G., & Baeten, X. (2017). Getting bang for your buck: The specificity of compensation and benefits information in job advertisements. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(19), 2811–2830. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1138989

- Wickham, H., Chang, W., Henry, L., Pedersen, T. L., Takahashi, K., Wilke, C., Woo, K., Yutani, H., Dunnington, D., & Posit, P. (2023). CRAN - Package Ggplot2. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html

- Wickham, H., Vaughan, D., Girlich, M., Ushey, K., & Posit, P. (2023). CRAN - Package tidyr. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tidyr/index.html

- Wiltshire, H. (2014). Sport performance analysis for high performance managers. In T. McGarry, P. O’Donoghue, & J. Sampaio (Eds.), Routledge handbook of sports performance analysis (pp. 176–186). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203806913.ch15

- Worsfold, P., & Macbeth, K. (2009). The reliability of television broadcasting statistics in soccer. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 9(3), 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2009.11868491

- Wright, C., Atkins, S., Jones, B., & Todd, J. (2013). The role of performance analysts within the coaching process: Performance analysts survey ‘the role of performance analysts in elite football club settings. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 13(2), 240–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2013.11868645

- Wright, C., Carling, C., & Collins, D. (2014). The wider context of performance analysis and it application in the football coaching process. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 14(3), 709–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2014.11868753

- Wright, C., Carling, C., Lawlor, C., & Collins, D. (2016). Elite football player engagement with performance analysis. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 16(3), 1007–1032. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2016.11868945

Appendix

Areas of Expertise

Components of APA Practice