ABSTRACT

Advances in technology have transformed our daily life communication activities. These days, online communication has become a norm and universally follows patterns of mass information sharing. In the Indigenous context, the community is inundated with the sheer volume of data available online. Thus, the capability of retrieving Elders’ knowledge relies on access to modern technology and the competency of end users. These issues may pose a challenge to the library and information services sector (LIS), as well as for Indigenous Elders who may have limited access to present technologies. This article synthesises the importance of understanding the Indigenous wisdom in engaging with Aboriginal people while emphasising the reciprocated relationship as opposed to a partnership approach. The authors drew on the value of Elders stories and shared learning practices expressed in the findings. Video dialogue process of unstructured interview was employed using visual ethnographic approach within the Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) paradigm. Data collected from three prominent Elders. Video recording had provided research participants with a voice adding rigour and accuracy to the information gathered, as contrasting to traditional observations. The video recording has led to approaches to work for and with Indigenous people ethically comprising valuable information significant to LIS.

Abbreviations: Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR), Library and Information Sciences (LIS), Conversational Analysis (CA)

Introduction

This article is part of a larger project, and it primarily focuses on designing frameworks for the ethical recording of Indigenous stories significant to library and information services sector (LIS). These days, online communication has become a norm and traverse universal patterns of mass information sharing. In the Indigenous context, the community is inundated with the sheer volume of data available online. Thus, the capability of retrieving Elders’ knowledge relies on the access to modern technology and the competency of end users. These issues may pose a challenge to the LIS sector specifically on integrating traditional storytelling with today’s digital tools for preservation and managing Indigenous stories collaboratively. Nakata, Byrne, Nakata, and Gardiner (Citation2005) stated that Indigenous knowledge is part of the heritage and history of the nation and therefore important to be considered and understood using both the Indigenous ways of knowing and LIS principles and values. Barnhardt (Citation2014) emphasise that Indigenous people are reaffirming their worldviews and ways of knowing to locally-recognised existing knowledge and cultural practices as the bases for LIS learning research (p. 13). Barnhardt (Citation2014) added that one of the vehicles for bringing coherence to LIS study is to recognise that Elders knowledge is as ‘valid for today’s generations as they were for generations past’ (p. 5). Today, Elders are concerned that knowledge published online presents a particular challenge as they imagine the Internet may replace the traditional ways of storytelling. In some cases, evidence of misrepresentation and exploitation of traditional knowledge purported through unethical research conducted by past researchers still lingers. As a result, Elders are reluctant to decide who is given the right to traditional knowledge specifically when stories are seen as sacred or secret and only accessible by initiated Elders of a specific gender (Dyson, Citation2011). This article synthesises the importance of understanding Indigenous wisdom and brings traditional knowledge, from the standpoint of the academic domain.

In this research, we were guided by three prominent Elders who are customarily educated with intergenerational stories passed on by their ancestors. Their stories evoke the value of Indigenous wisdom through both practical and historical experiences. Excerpts of research participants’ stories draw on the holism of knowledge rather than as an individual. The potential significance of video to record Elders stories ethically is worth pursuing as it can incorporate shared learning practices and enable the probable implications to LIS. In doing so, we were inspired to interrogate the following questions:

What are the knowledge tools used to record, disseminate and preserve Indigenous peoples’ stories?

Can new technology help preserve the embodied value of traditional stories?

By citing our previous works, we validate and acknowledge research participants’ sense of belonging to their identity. We have capitalised the words ‘Indigenous’ and ‘Elder’ as these terms are used to identify a person’s ethnicity and belief system (Haines, Du, Geursen, Gao, & Trevorrow, Citation2017, p. 2). The words ‘Aunty’ and ‘Uncle’ in this study refer to the Elders and are terms that are collectively used to show respect for their status in the community (Haines et al., Citation2017, p. 3). Referring to such communications as personal communication is another cultural parameter that we are proposing as part of ethical research and include the dates on which the interviews were recorded (Haines et al., Citation2017, p. 2).

Methodology

Visual Ethnography and Community-Based Participatory Research in Practice

This research used a qualitative method and employed a visual ethnographic approach within the community-based participatory research (hereafter abbreviated as CBPR) paradigm. The fusion of community-based participatory research and visual ethnography played a dual role in generating visual information that parallels to Indigenous culture and traditions of storytelling. The used of visual ethnography serves rational models to engage and investigate a specific aspect of the participants’ cultural practices and artistic knowledge (Haines et al., Citation2017; Pink, Citation2013). The visual ethnographic process is a descriptive method that uses video and photographic images to capture unobserved information that is problematic to contextualise in written text alone. The use of photographic and film images is an innovative process to gain useful insights into the participant’s behaviour of generating new knowledge in less time (Haines et al., Citation2017). It is a symbolic practice that enriches visual text through cultural immersion and by implementing appropriate methods for assessing Elders stories. It serves as an active research tool in the quest to collect and analyse empirical evidence for ethical dissemination of research findings (Schembri & Boyle, Citation2013).

CBPR is an ideal approach to generate a collaborative relationship that equitably involves the Indigenous community members, organisations’ representatives and academic researchers in all aspects of the research process. In addition, the principles of reciprocity resonate with visual ethnography and informed consent to ensure that confidentiality and transparency of information gathered underpin respect in advancing outcomes directed to the research participants (Haines et al., Citation2017). Rodgers et al. (Citation2014) viewed CBPR as a useful method because it engages the community, but it may present challenges for both the academics and the community involved. These challenges can be seen in the Indigenous participatory research process where the participants’ social protocols, cultural and environmental structures could influence research participants’ availability (Roberts, Citation2013). Hence, there is the need to build a relationship and trust rather than just a partnership, and the issues are controlled by the community’s lens. In this manner, a deeper understanding of community’s concerns is addressed and focused on a two-way knowledge approach with the communities for co-creation and dissemination of research findings (Mikesell, Bromley, & Khodyakov, Citation2013). Cobus (Citation2008) indicates that LIS can be the forefront in promoting CBPR principles for active community involvement in the processes that shape ethical research strategies while leveraging community’s strengths, knowledge and resources.

LIS – Community Convergence Procedure for Reciprocated Relationships Practices

The dialogic research process is essential to establish a real relationship rather than a partnership the latter, which tends to be seen as a business transaction (Castleden & Kurszewski, Citation2000). In contrast, sustaining a research relationship with the Indigenous community is less a transaction and instead enacted through a mutual commitment and collective trust (Israel et al., Citation2006; Sieber, Citation2010). CBPR is about creating a space for research participants to contribute toward utilising Indigenous ways of knowing and interpreting data ‘within a cultural context’ (Haines et al., Citation2017; p. 2; LaVeaux & Christopher, Citation2009; p. 7). Furthermore, Castleden, Mulrennan, and Godlewska (Citation2012) suggest that creating a shared relationship and learning together is to build trust and respect as well as reciprocity in strengthening the intended purpose of the CBPR framework privileging the Indigenous voice. CBPR is about valuing a collective research outcome to generate a sustainable participation, and shared power in decision-making between the researchers and the community involve (Mikesell et al., Citation2013). To do this is to respect and ‘recognise that members of the community under study are the experts of their knowledge’ (Haines et al., Citation2017, p. 2). Lavallée (Citation2009) added that CBPR principles are an ideal method for developing an ethical research relationship when working with Indigenous people. In practice, research with the Indigenous community is a commitment that extends well beyond the final report, dissertation, peer-reviewed article submission, and completion of the research project (Lavallée, Citation2009). When the community contacts the researcher, the team must be prepared to assist with their requests. Therefore, both CBPR and visual ethnography systematically take advantage of what modern technology offers to preserve and retain the integrity of the research participants’ voices, and in turn, illustrate the social responsibility and foundation of ethical research practices (Haines et al., Citation2017).

According to Mehra and Srinivasan (Citation2007), LIS needs to be proactive and be a social catalyst for the preservation of Elder’s knowledge (p. 5). The critical issue to note here is that LIS can act a referral agent for local community information resources and support services that make them directly relevant to the needs of the community (Mehra and Srinivasan (Citation2007). Russell and Huang (Citation2009) suggest that the most effective way to sustainable research relationship with Indigenous communities is providing ongoing information structure that supports communities’ daily life activities. Provided that, collective responsibility is required to recognise communities, collective rights and freedom of expression (Roy & Hogan, Citation2010). In addition, Nakata et al. (Citation2005) noted the following:

LIS has a role in serving marginalised communities

There is a community-focused referral role for libraries with respect to significant community issues of diversity and intellectual freedom, ethical documentation of stories and truthful Indigenous knowledge management

Libraries have a role which includes to participate more fully in community activities and as proactive catalysts of social change.

Although CBPR has the capability for genuine connection, to build a sustainable relationship with the Indigenous people, the process should be ongoing. Burns, Doyle, Joseph, and Krebs (Citation2009) indicate that improving the public library services for Indigenous Australians is to raise the profile of Indigenous people in libraries, particularly at the State Library level. It must be noted that increasing Indigenous employment and librarian training opportunities would create a balance between the Indigenous community and LIS knowledge.

Research Design

The collaborative methodology is placed at the centre of the research design and key focus on maintaining the principles of CBPR (Becvar & Srinivasan, Citation2009). Given the cultural sensitivity of the data gathered, we insured that informed consent and transparency of data results were established before the research begun and a representative Elder from the community is a co-author of this paper. Our 18 years of connection with the Elders at the Camp Coorong community had provided space for ongoing conversation. A new cultural parameter in our design is to transcribe the video excerpts as the participants expressed. This approach was to ensure that the knowledge shared by the Elders is cherished and respected.

Research Location and Ngarrindjeri Participants

Camp Coorong is located about 200 km Southeast of Adelaide, adjacent to Bonney Reserve and South Australia’s Coorong National Park. Camp Coorong is a community-based education facility and tourism enterprise centre. The Aboriginal Land Trust purchased the land for Camp Coorong with the intention that it will be a place for South Australia’s schoolchildren to learn about the Ngarrindjeri culture and history, with the long-term aim that this experience will contribute to the reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Camp Coorong was our host community.

The research participants were purposefully selected based on their role as an Elder in the community. Data were collected from three Elders that included two female and one male Elder, aged between 63 and 83 years old, guided us culturally, and were keen to share their stories. All three Elders are the descendants of the stolen generation. Therefore, their practical experiences as cultural educators, mentors and storytellers were crucial to the development of this paper and future projects. Data were gathered during field appointments between September 2016 and January 2018, and follow-up visits were necessary. This ensures that transcribed data were interpreted truthfully in collaboration with the Elders. Aunty Ellen Trevorrow, Aunty Hilda Blessios and Uncle Moogy Sumner consented to be photographed and video recorded, and excerpts of their stories are embedded in the findings adding rigour and transparency of transcribed data. In addition, Elders’ active involvement on this project strengthens our shared research practices and recognises their significant contribution to this paper as co-researchers during the editing process of the paper (Haines et al., Citation2017).

Data Analysis and Collection Methods

Conversational Analyses of Video Social Interaction

Conversational analysis (CA) is an appropriate method for this research. Using CA, we explore the connection of stories through social interaction between individual participants. CA’s focus was on the everyday conversations of participants’ stories. The knowledge contained in stories provide rich information, revealing subtle yet analytic resources of recorded cultural activities as it happens, augmented by fieldwork. Video of social interaction captures recordings of unwritten actions and practices, such as body gestures, expressions and voice intonations during the dialogue interview (Goodwin & Heritage, Citation1990). Analysis of unstructured interviews demonstrates a strong connection to values and beliefs. To capture participant’s expression, we routinely left the camera in a free-standing holder with a movable handlebar to accommodate changes in participants’ movements and in order not to distract participants’ attention. In this case, it enabled us to assess the fine, seemingly trivial stories and understand the importance of traditional stories.

The analysis of the video interviews with three Elders outlines a strong connectedness to values, namely kinship, stories, ceremony, traditional laws and culture. Research participants’ philosophies have guided their way of life in making sure that their stories survived. They shared their wisdom about what it means for them to live on their land and their great passion for successfully passing on their knowledge to the next generation. By focusing our discussions on the practicality of video dialogue, we transcribed the data collected from three prominent Elders. Personal behaviour and mannerisms are challenging to capture by audio recording alone. Consequently, the video footage was used to capture verbal expression, social interactions between participants, emotion, body language and gestures. The transcribed video data were open-coded and supported the development of the framework that deployed interdisciplinary ways of transmitting and disseminating the Ngarrindjeri knowledge ( and ).

Table 1. Interdisciplinary ways of learning.

‘Weave and Talk’ or ‘Lakun Wanyali Thungari’ Data Gathering Tools

In this research, we coin and propose a new approach that is culturally and ethically affirmed interdisciplinary ways of data collection. This process allows the research participants to convey their voice about their weaving practices without the interference from the researchers (Galla & Goodwill, Citation2017). ‘Weave and Talk’ is a creative method to understand the collective knowledge and resilience of the Ngarrindjeri weaving. Weaving is one of the prevalent knowledge tools used by the Ngarrindjeri women. It is viewed as a ceremonial process, a cultural metaphor for promoting the knowledge continuity of stories by transmitting stories to the younger generation. To ‘Weave and Talk’ or ‘Lakun wanyali Thungari’ in the Ngarrindjeri word expresses the identity and culture of the weavers and continuing sense of belonging to the Ngarrindjeri Ruwe (Ngarrindjeri country). The act of weaving itself refers to the visual ethnographic significance of the everyday life practices of the Ngarrindjeri weavers and the economic value of it as a trade item. Weaving is an interdisciplinary platform for multi-disciplinary approaches to understanding life experiences on traditional land. Weaving is a process involving embodied values and wisdom, a participatory process with spontaneous modes of social engagement in rhythmic practices of weaving.

To build a positive relationship for, and with, Indigenous people, ‘Lakun wanyali Thungari’ was an ideal strategy for data collection that embraced every aspect of dialogic learning. This method implied the reliability of recording cultural stories that necessitate respect, trust and reciprocity. The knowledge of weaving is constantly evolving – re-strengthening its commitment and dedication to the culture of weaving. The data collection was divided into two parts: the dialogue session was first conducted before we started the weaving session, and the second part was during the active sessions of weaving. The ‘Lakun wanyali Thungari’ session lasted for 1–3 h with frequent breaks. It is a method that takes time and perseverance in eliciting data that could not otherwise be possible to obtain using conventional procedures.

Findings and Discussion

Indigenous Wisdom through Storytelling

Indigenous wisdom is woven into the landscape, entrenched in localised ecosystems passed down through generations and systematically used, tested and improved by each generation (Hendry, Citation2014). Findings showed that Indigenous wisdom offers insights into a worldview of relatedness to values of kinship, stories, culture, ceremony and traditional laws. In addition, the Elders demonstrate their sense of connectedness to their values and beliefs, as guides, to make sure that their stories survive. Therefore, Elders are respected as knowledge keepers of great wisdom, imparting generational beliefs systems and everyday life practices. Indigenous wisdom synthesises a living library of knowledge that integrates experiences and a deep understanding of the land, adaptability, tolerance and resilience. Evidence also shows that the tacit and explicit nature of Indigenous wisdom relied on the continuing work of knowledge holders in successfully passing on their stories to the next generation. Stresser-Péan and Austin (Citation2009) indicated that Elders have a vital role in the contemporary Indigenous society due to the particular knowledge and practicality that they use in everyday life practices, as visualised in . Knowledge holders are always on call as they find it hard to say no when it comes to communication and the preservation of culture and traditions. This view is manifested in the ways the Elders are cared for and respected as knowledge holders not only by their communities but also by outsiders. To understand Indigenous wisdom, it is necessary to walk alongside the Elders, as Uncle Moogy advised:

As an Elder, it’s not an easy job; I am on call. In saying that…to have a full understanding of our culture, you need to learn the whole thing, it might take time, but it’s not going to work with me if you only want to learn a little bit. You have to understand the whole process, and we talk about ceremonies…like the men’s ceremony, we talk to people about it…we have to do it properly, but it is going to take time because we have so much in our plate and we have so many responsibilities today…so, all of that, no matter where you are and where you came from everything is similar…our songs, there’s dance, our stories, there’s law – there’s punishment…understand and respect is very important (Sumner, M, personal communication, 17 June 2016)

It is clear from the excerpt that Indigenous wisdom is formed on five pillars of knowledge, as we mentioned above. Significantly, this knowledge is not merely the revival of the tradition of the past but expresses the participants’ behaviours towards the future that their traditional knowledge face against the untimely passing of knowledge holders and the demands of modern technology.

As noted earlier, Uncle Moogy explained the importance of Indigenous wisdom to the real-world as follows:

….it’s about learning, as you working, you are receiving the wisdom from the Elders…you are the artist, you just can’t paint without learning unless he/she an artist shows different ways how to look a light on a painting, we are good at different things, but we have to share our knowledge for the future generation and left something for the next generation to come (Sumner, M, personal communication, 17 June 2016).

Here is a video excerpt that occurs during our face-to-face interaction with Aunty Ellen Trevorrow (Kissmann (Citation2009). She illustrates the centrality and importance of understanding our Miwi (inner spirit/gut feeling) wisdom and explicitly stated as follows:

Miwi gives you signs, and it’s important to know it…it’s like a six sense, it comes from your tummy…your Pulanggi (inside your navel), at the back of your tummy within your stomach…and most importantly, we gonna take care of it. You know, if you are in the wrong place….we had our good times, we had our bad times, and we have our hard times and…you gonna let that Miwi talk and let it help us to get through. The old fellows all did it that way. I know myself that….not letting it talk, a little bit if we got problems the Miwi sorts it out, it gives you thought and its right direction…we gonna make sure that we action our Miwi within us, you know, caring and making sure everything is correct. It is so sad when things go wrong; it’s like your Miwi gonna talk extra harder to you. The old fellows we need to call on them, just like what Uncle Moogy does during the welcome ceremony. We gonna things right and be able to enjoy what we do…there’s always job needs to be done; it’s like healing. (Trevorrow, E., personal communication, 17 August 2017).

Findings suggest that the Miwi wisdom is part of participants’ social beliefs that promote cautionary intuition on dealing with logical emotion, specifically in making any decisions. Miwi wisdom is viewed as the powerful guiding spirit, which addresses care and truthful actions.

Aunty Hilda Blessios’ emu stories express practicality – they are stories of resilience and reflect the ingenuity of living on traditional land. This is the first time that Aunty Hilda’s stories have been recorded on video. Although this is significant, it is the legitimacy of the story that brings meaning and the entirety of knowledge transmission. The emu story video clip published in Vimeo provides visual records with unprecedented access to such complex tasks of unpacking oral stories (see the link, https://vimeo.com/254150935). Within the dominant oral culture, the video recording of the emu stories unified the past with the present and allowed the future to continue to enjoy the past for its continued existence. In this context, the emu stories tell explicit memories of wisdom about hunting, family gathering and social interactions of life experiences. There is also an indication that Elders who are firmly connected to the land are extraordinarily knowledgeable, expressive, and passionate storytellers. Aunt Hilda’s stories illustrate the practice of detailed storytelling shared by Aunt Hilda Blessios.

1. What are the knowledge tools used to record, disseminate and preserve Indigenous peoples’ stories?

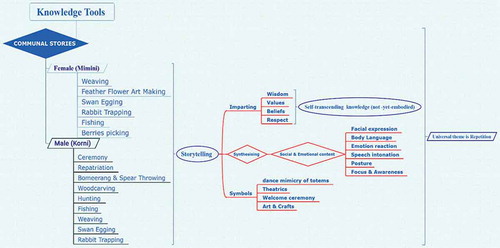

Disseminating Indigenous stories involves social interactions and meaning-making whether through verbal or non-verbal communication. Meaning-making is about how the socio-cultural context of defining Indigenous stories’ importance during the process of interaction. In the light of all this, Indigenous stories are expressed in metaphors and cultivated through the use of knowledge (survival) tools (). These knowledge tools consist of female (Mimini) and male (Korni) communal stories. They are regarded as universal stories because they are shaped out of a cyclic retelling of stories during cultural and ceremonial activities. These developments enrich participants’ emotions and conscious thoughts of eliciting stories, for example, the story of basket weaving brings up a whole host of associated stories. It is a dialogic practice of engagement where Elders correlate memories of facts and experiences through storytelling. It is an approach to make sense of their everyday life practices. In cultural terms, survival tools are used to impart knowledge, retain, reiterate and safeguard the integrity of the stories.

This is something to posit that the participants dynamically generate communal stories as they reminisce and integrate new information with their present-day knowledge ( and ). The data suggest that stories become a cultural artefact as a community and each knowledge tool form stories that shape the community; they are also respected as a method for preserving stories. Data also suggest the knowledge boundaries between male and female information sharing is continually carried out.

Dialogic conversations with Uncle Moogy suggest as follows:

There was some sharing of knowledge but not in some cases/places; there’s a specific law for women and law for men …means that nothing to be shared apart from communal stories…because you got different types of societies…different laws, different places where they practice and…you know, we have our sacred stories, but stories were not being told the people (Sumner, M., personal communication, 17 June 2016).

2. Can new technology help preserve the embodied value of traditional stories?

Increasingly, the advancement of technology can substantiate the preservation of Elders wisdom for the future generation and scientific knowledge. Nonetheless, determining appropriate technology capable of modifiable features to preserve the embodied value of traditional stories still pose a challenge largely for the Elders and create obstacles between generations. Given that the opportunities of technology support the preservation of traditional stories, researchers need to make sure that misrepresentation and exploitation of traditional knowledge are avoided once Elders’ stories are published online. The digital dissemination of Elders’ knowledge can be another method to unite the gaps between the Elders and the younger generation to enable dialogic engagement.

Evidence shows that digital technologies offer avenues for the younger generation to retrieve information concerning Indigenous stories. is an image featuring a child watching and listening to Aunty Ellen’s video recording instructing her on how to weave a basket. The instructional video was created to be used as envisioned. However, when the child was inaccurate in her stitching, she needed Aunty Ellen’s personal assistance to repair an area of the basket. In this context, results demonstrate that Elders’ personal guidance is critical in accurately passing knowledge to younger generations. This shows that digital recording can never be a substitute for traditional ways of teaching. The legitimacy to see and hear the teachings directly from the Elders creates that meaning-making. It provides a visual context as well as a sense of connection, feeling, passion, empathy, resilience and human touch – all the senses that you do not fully grasp from reading alone or watching recorded stories. However, it can be argued that technology can be utilised with appropriate competencies to digitally circulate Aunty Ellen’s basket weaving sensitively and ensure that ongoing engagement of a younger generation with their traditional knowledge continues (). Findings expressed the likelihood of technology in enhancing Elders’ knowledge of weaving.

We indicate that the relationship contains a truthful research approach as opposed to the identification of the research participants as partners. At its best, a dialogic conversation starts with the perception of listening and understanding what the research participants can contribute to the research (Arnett, Bell, & Fritz, Citation2010).

Interdisciplinary methods of learning may benefit from the incorporation of technology to highlight the intricacies of Elders’ stories by adding their voices to the research. In the Indigenous context, learning is not one-way traffic. It is viewed as a continuous process of adaptation and incorporation of new learning principles to enhance the traditional wisdom further. We must take significant efforts to incorporate interdisciplinary ways of learning to help bridge the existing gap between mainstream knowledge and Indigenous wisdom. We envisage that using Elders wisdom as a community resource with the assistance of technological innovation design will stimulate Indigenous communities’ interest (). The oppression suffered by the Indigenous community was taken into account by past research, which in doing so, ensured systematic, participatory research. Bringing traditional knowledge into the literature can help preserve valuable skills held by remaining Elders.

A Conceptual Framework for Interdisciplinary Ways of Learning Together

To achieve interdisciplinary ways of learning is to acknowledge the importance of Indigenous wisdom in establishing collaborative research. proposes a two-way knowledge approach practices that will play a valuable role in community-based participatory research. At face value, the process of interdisciplinary ways of learning is to listen to the needs of the community involved and to ensure that they are not left dissatisfied as a result of the project (Okorafor, Citation2010).

Conclusion

Results highlight that participants knowledge included in this study are recognised for its significance and impacts on disseminating accurate conclusions. Outcomes reveal that Indigenous wisdom is an amalgamation of generational life experiences and provide a significant impact on Elders’ knowledge journey. Research participants’ strong connection to ancestral culture and the land are valuable knowledge assets that need protection ( and ). Indigenous ways of teaching using the knowledge tools are taught as real-life learning experiences drawn from a personal connection to country (). Findings show that stories are central and considered as a part of knowledge that comes from localised learning. It was also noted that gaining wisdom from the Elders will take time as learning the knowledge is measured as the whole process, though stories are told incrementally to make sure that knowledge pass on is respected and valued. Therefore, misinterpretation of stories is evaded. In the same way, understanding Indigenous wisdom is about learning by doing, and so, a mere revival of the knowledge is insufficient. Metaphorically, Indigenous wisdom is equivalent to looking at a Library of Congress, with diverse subjects dedicated to various cultures, traditions, values, beliefs and practices from around the world, with an open mind. In this study, Elders are seen as the carriers of living knowledge. For example, the Miwi wisdom, which promotes a cautionary intuition (gut feeling) to rationalise emotions in decision-making, are, also imbued with a guiding spirit. Hence, it may be said that both life experiences and generational stories play a vital role in Elders’ professional life.

Current findings show that interdisciplinary methods of learning benefited from incorporating modern technology to record the complexities of Elders’ stories digitally. The result reveals that to strengthen the interdisciplinary ways of learning is to add participants’ voices on research outcomes and take advantage of modern technology to preserve Indigenous stories ethically. Results also reveal that Indigenous wisdom plays a vital role in the interdisciplinary ways of learning while contributing to the continuing understanding of strengthening the interdisciplinary ways of learning together with Indigenous people and is relevant to information and library studies. The diversity of Indigenous wisdom will contest future research to find out technology interfaces that will have the competencies to record and represent Elders’ knowledge within the cultural context. Our next research is to generate a model that will successfully describe how research participants envision the impact of this study and points to a number of areas where further research would be invaluable for LIS.

Implications for practice

Build relationships as opposed to partnerships to preserve Indigenous wisdom.

Acknowledge Indigenous knowledge as a community resource.

Finding appropriate methodologies to work with and for Indigenous people and inform practice to integrate Indigenous and Western knowledge systems in teaching, shared research and collaborative Indigenous knowledge management.

Acknowledge Indigenous research participants as co-researchers.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship. The authors sincerely acknowledge the contributions of the Ngarrindjeri Cultural Mentors, Elders, participants and the Ngarrindjeri Land and Progress Association for welcoming us to the community. We thank anonymous reviewers for their valuable contribution to improving the quality of this paper. Sincere thanks to the first author’s other supervisors Dr Joanne Evans, Dr Jing Gao and Prof. Gus Geursen for their moral support and comments of this research.

Disclosure statement

This work was supported by the Research Training Program (formerly APA), Department of Education and Training.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jelina Haines

Jelina Haines is a PhD student of Information Studies in the School of Information Technology and Mathematical Sciences at the University of South Australia. Her current PhD research interest focuses on Indigenous Elders knowledge journey practices observed during the cyclical process of knowledge creation, synthesis, translation, ethical knowledge dissemination and preservation of Elders stories using video dialogue diary. She can be contacted at [email protected]

Jia Tina Du

Jia Tina Du is Senior Lecturer of Information Studies in the School of Information Technology and Mathematical Sciences, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia. Tina is also an Australian Research Council (ARC) DECRA Fellow (2017-19). Tina holds a PhD in information studies from Queensland University of Technology, Australia. Her research focuses on understanding the interplay between humans, information and technology, including theories and applications related to user-Web interactions, human information behaviour and social impact of the Internet. Dr Du can be contacted at [email protected]

Ellen Trevorrow

Mrs Ellen Trevorrow is a Ngarrindjeri Elder and world-renown artist and cultural weaver with over 37 years’ experience and lives and works in the Ngarrindjeri country at Camp Coorong. She is the manager of Camp Coorong, Centre for Cultural Education and Race Relations as part of the Ngarrindjeri Land and Progress Association. Mrs Trevorrow can be contacted at [email protected]

References

- Arnett, R. C., Bell, L. M., & Fritz, J. M. H. (2010). Dialogic learning as first principle in communication ethics. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 18(3), 111–126.

- Barnhardt, R. (2014). Creating a place for indigenous knowledge in education: The Alaska native knowledge network. In Place-based education in the global age (pp. 137–158). Routledge.

- Becvar, K., & Srinivasan, R. (2009). Indigenous knowledge and culturally responsive methods in information research. The Library Quarterly, 79(4), 421–441.

- Burns, K., Doyle, A., Joseph, G, & Krebs, A. (2009). Indigenous librarianship. In M. J. Bates, & M.N. Maack (Eds.), Encyclopedia of library and information sciences (3rd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis.

- Castleden, H., & Kurszewski, D. (2000). Re/searchers as co‐learners: Life narratives on insider/outsider collaborative re/search in indigenous communities. In Proceedings of the 41st Annual Adult Education Research Conference, ed. T. Sork, V. Chapman, & R. St. Clair. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia, 71–75.

- Castleden, H., Mulrennan, M., & Godlewska, A. (2012). Community‐based participatory research involving indigenous peoples in Canadian geography: Progress? An editorial introduction. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Ccanadien, 56(2), 155–159.

- Cobus, L. (2008). Integrating information literacy into the education of public health professionals: Roles for librarians and the library. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA, 96(1), 28–33.

- Dyson, L. (2011). Indigenous peoples on the internet. The Handbook of Internet Studies, 11, 251.

- Galla, C. K., & Goodwill, A. (2017). Talking story with vital voices: Making knowledge with indigenous language. Journal of Indigenous Wellbeing, 2(3), 67–75.

- Goodwin, C., & Heritage, J. (1990). Conversation analysis. Annual Review of Anthropology, 19(1), 283–307.

- Haines, J, Du, J. T, Geursen, G, Gao, J, & Trevorrow, E. (2017). Information research. Understanding Elders’ Knowledge Creation to Strengthen Indigenous Ethical Knowledge Sharing, 24(4), 1-15. Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/22-4/rails/rails1607.html

- Hendry, J. (2014). Science and sustainability: Learning from indigenous wisdom. USA: Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

- Israel, B. A., Krieger, J., Vlahov, D., Ciske, S., Foley, M., Fortin, P., … Tang, G. (2006). Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: Lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle Urban Research Centers. Journal of Urban Health, 83(6), 1022–1040.

- Kissmann, U. T. (2009). Video interaction analysis. In Methods and methodology. Frankfurt/M: Peter Lang. GmbH.Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften, Germany.

- Lavallée, L. F. (2009). Practical application of an indigenous research framework and two qualitative Indigenous research methods: Sharing circles and anishnaabe symbol-based reflection. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 21–40.

- LaVeaux, D., & Christopher, S. (2009). Contextualising CBPR: Key principles of CBPR meet the indigenous research context. Journal of Indigenous Wellbeing, Te Mauri - Pimatisiwin, 7(1), 1–25. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2818123/

- Mehra, B., & Srinivasan, R. (2007). The library-community convergence framework for community action: Libraries as catalysts of social change. Libri, 57(3), 123–139.

- Mikesell, L., Bromley, E., & Khodyakov, D. (2013). Ethical community-engaged research: A literature review. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), e7–e14.

- Nakata, M., Byrne, A., Nakata, V., & Gardiner, G. (2005). Indigenous knowledge, the library and information service sector, and protocols. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 36(2), 7–21.

- Okorafor, C. N. (2010). Challenges confronting libraries in documentation and communication of indigenous knowledge in Nigeria. The International Information & Library Review, 42(1), 8–13.

- Pink, S. (2013). Doing visual ethnography. (3rd ed). London.Pink, S.: Sage Publications Ltd. (2013).London: Sage.

- Roberts, L. W. (2013). Sustaining the Partnership. In Community-Based Participatory Research for Improved Mental Healthcare. New York, NY: Springer.

- Rodgers, K. C., Akintobi, T., Thompson, W. W., Evans, D., Escoffery, C., & Kegler, M. C. (2014). A model for strengthening collaborative research capacity: Illustrations from the Atlanta Clinical Translational Science Institute. Health Education & Behavior, 41(3), 267–274.

- Roy, L., & Hogan, K. (2010). We collect, organize, preserve, and provide access, with respect: Indigenous peoples’ cultural life in libraries. Beyond Article 19 Libraries and Social and Cultural Rights, 113(148), 113–148. Litwin Books in association with GSE Research.

- Russell, S., & Huang, J. (2009). Libraries’ role in equalizing access to information. Library Management, 30(1–2), 69–76.

- Schembri, S., & Boyle, M. V. (2013). Visual ethnography: Achieving rigorous and authentic interpretations. Journal of Business Research, 66(9), 1251–1254.

- Sieber, J. E. (2010). Life is short, ethics is long. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics: an International Journal, 5(4), 1–2.

- Stresser-Péan, G., & Austin, A. L. (2009). The sun god and the savior: The Christianization of the Nahua and Totonac in the Sierra Norte de Puebla, Mexico. Boulder CO: University Press of Colorado.