ABSTRACT

This article documents the Health Libraries for the National Standards (HeLiNS) research project. The project received the ALIA 2016 research award and was undertaken by a collaboration of the ALIA/Health Libraries Australia and Health Libraries Inc groups. The research aimed to explore the contributions made by Australian hospital libraries to assist their organisations to achieve accreditation against the National Safety and Quality for Health Services (NSQHS) Standards. The research clearly demonstrates that hospital libraries are integral to a hospital’s quality and safety systems. They make substantial and essential contributions through their professional information/knowledge management services and by ensuring access to evidence-based resources. The research found that there are varying levels of contributions, however, and it is suggested that these differences may be influenced by variables such as location and size of hospital. It is further suggested that for hospitals without a library service, or those with libraries that have limited capacity to deliver professional services and resources, there is likely to be an ‘evidence-accessibility gap’, and they may be at risk and not performing as well as they could in regard to NSQHS accreditation standards, and safety and quality systems.

Introduction

Background to the Research

The National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS) Standards (Citation2012) were developed by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) in collaboration with the Australian Government, state and territory partners, consumers, clinicians, and policymakers within the public and private sector. A brief description of each Standard follows:

Standard 1. Governance for Safety and Quality in Health Service Organisations – describes the quality framework required for health service organisations to implement safe systems.

Standard 2. Partnering with Consumers – describes the systems and strategies to create a consumer-centred health system by including consumers in the development and design of quality healthcare.

Standard 3. Preventing and Controlling Healthcare-Associated Infections – describes the systems and strategies to prevent infection of patients within the healthcare system and to manage infections effectively when they occur to minimise the consequences.

Standard 4. Medication Safety – describes the systems and strategies to ensure clinicians safely prescribe, dispense and administer appropriate medicines to informed patients.

Standard 5. Patient Identification and Procedure Matching – describes the systems and strategies to identify patients and correctly match their identity with the correct treatment.

Standard 6. Clinical Handover – describes the systems and strategies for effective clinical communication whenever accountability and responsibility for a patient’s care are transferred.

Standard 7. Blood and Blood Products – describes the systems and strategies for the safe, effective and appropriate management of blood and blood products so the patients receiving blood are safe.

Standard 8. Preventing and Managing Pressure Injuries – describes the systems and strategies to prevent patients developing pressure injuries and best practice management when pressure injuries occur.

Standard 9. Recognising and Responding to Clinical Deterioration in Acute Healthcare – describes the systems and processes to be implemented by health service organisations to respond effectively to patients when their clinical condition deteriorates.

Standard 10. Preventing Falls and Harm from Falls – describes the systems and strategies to reduce the incidence of patient falls in health service organisations and best practice management when falls do occur.

The aim of the NSQHS Standards is to ‘protect the public from harm and improve the quality of healthcare. They describe the level of care that should be provided by health service organisations and the systems that are needed to deliver such care’. (ACSQHC, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/assessment-to-the-nsqhs-standards/Accessed 1 May 2018)

The second edition of the NSQHS Standards was released in November 2017 to commence from 1 January 2019. The revised Standards promote a more patient-centred approach to accreditation with the intention of increasing efficiency and effectiveness at the point of care. Although the research project was conducted when the first edition was in force, the findings are equally applicable to the second edition, which integrates and strengthens the original themes.

The HeLiNS Research Project

The HeLiNS (Health Libraries for the National Standards) research project was conducted between November 2016 and May 2018. The research aimed to explore the contributions made by Australian hospital libraries in assisting their organisations to achieve accreditation against the NSQHS Standards (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care [ACSQHC], Citation2012).

Health Libraries in Australia

A census of health library and information services had found that there were 95 hospital libraries of a total of 328 Australian health library and information services; and around 70% were located in capital cities (Kammermann, Citation2016). Almost two-thirds of health libraries were found in the public sector, followed by the not-for-profit sector (around one-fifth) and the private sector (around one-seventh). The HeLiNS research used the census findings as the population from which to draw its sample.

Literature Review

Health services accreditation is a process of external peer review to assess the performance of a healthcare facility in relation to agreed healthcare accreditation standards (Swiers & Haddock, Citation2019, p. 2). Its purpose is to provide assurance that the facility meets minimum agreed standards at a point in time.

Accreditation of Health Services – A Brief History

Current models of accreditation programmes for healthcare facilities were developed in the United States and Canada in the 1950s. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) was formed by peak US and Canadian medical, surgical and hospital associations, and began offering accreditation to hospitals in 1953; it has been a major provider in the US since then. Canada commenced its accreditation programme in 1959. A 2003 overview of the global quality and accreditation landscape by the World Health Organisation found similar programmes in more than 70 countries (World Health Organization [WHO] & Shaw Citation2003). In addition to whole-of-hospital accreditation, there are specialist programs such as the Magnet Recognition Program® for nursing practice.

The American external peer review model was adopted in Australia (Scrivens, Klein, & Steiner, Citation1995). The Australian Hospital Standards Committee (later known as the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards or ACHS) formed in 1972 and granted its first accreditation certificate to Geelong Hospital in November 1974 (McIntosh, McManus & Party, Citation2015 p. 2). ACHS continues as a key independent assessor of performance, assessment and quality for Australian healthcare organisations.

Quality improvement initiatives in healthcare systems progressed in parallel with accreditation from the late 1970s onwards, accentuated after revelations in the 1990s of the adverse events – including deaths – which were attributable to failures in hospital systems (Brennan et al., Citation1991; Wilson et al., Citation1995). Subsequent government action in Australia included establishment of the Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care, which evolved into the Australian Commission for Safety and Quality in Healthcare in 2006. The Commission released its NSQHS Standards in June 2012, and these became mandatory for all Australian hospitals and day procedure organisations at the start of 2013.

Concerns have been expressed for some time about the lack of strong evidence that accreditation is effective in improving patient safety, clinician performance or hospital quality. For example, a Cochrane review by Flodgren, Goncalves-Bradley & Pomey (2011, updated in Flodgren, Goncalves-Bradley, & Pomey, Citation2016) and a systematic review by Brubakk, Vist, Bukholm, Barach, and Tjomsland (Citation2015) concluded it was not possible to determine any link between accreditation and measurable changes in quality of care. Lam and colleagues examined US hospital data for 2014–2017, and found that accreditation by an external body was not associated with lower mortality, and was only weakly associated with reduced readmission rates (Citation2018).

Greenfield and colleagues reached a different conclusion after conducting a longitudinal study of 311 Australian hospitals participating in the ACHS accreditation programme. They found that performance in clinical care and human resource management processes improved during the 8-year timespan of two accreditation cycles, and concluded that accreditation programmes can facilitate continual and systematic improvement changes to hospital sub-systems (Greenfield, Citation2019 p. 664).

Libraries in the Accreditation Standards

Health libraries have generally been supportive of their institutions’ undergoing external accreditation. The process has been seen as an opportunity for the library service to demonstrate its impact on the overall goal of provision of evidence-based care, with the added benefit of greater visibility within the institution. To this end, health librarians have pushed to have libraries and library services included in accreditation standards.

However, this goal required strategic advocacy by librarians working with the accreditation bodies. Foster (Citation1979 p. 226)) notes that the first edition of the JCAHO accreditation standards described the medical library as “a desirable but not an absolute prerequisite for hospital accreditation” (p. 226). By the time of the 1971 Accreditation Manual, the standards for library services were presented as guidelines or suggestions. In addition, critics complained that the early accreditation standards for libraries were not robust. In Citation1980 Topper et al. commented:

Before 1978, the JCAH standards for professional library services were so vague as to provide little basis for the librarian to prepare for an accreditation visit, or for a surveyor to judge the caliber of library services provided (p. 218).

Flower (Citation1978) also noted the potential gap between theory and reality:

Finally, as important as it is to articulate hospital library standards, it is even more important to make them stick … There is as yet no evidence that the accreditation of any particular hospital will really be affected either way by the caliber of its library (p. 301).

Associations of health library professionals realised their input was vital to boost the provisions for libraries in the accreditation standards. A working party of Canadian health librarians had developed the Canadian Standards for Hospital Libraries in 1973–4, and succeeded in having them incorporated into the Canadian Guide to Hospital Accreditation 1977 edition (Flower, Citation1978). In the United States, the Medical Library Association (MLA) contributed to the revision of the JCAH’s standards, resulting in improved and more flexible requirements in the 1978 edition of the Accreditation Manual (Foster, Citation1979, p. 227).

A decade later, the JCAHO undertook a major revision to the evaluation process for hospitals. There was a shift from standards for individual departments to standards for hospital-wide functions. This approach entailed the removal of any mandate for the existence of a hospital library or a librarian, and in the 1994 Accreditation Manual the Professional Library Services chapter was deleted. Among the new function areas was the Management of Information (IM) function, highlighting the importance of information and information managers to the provision of patient care. The IM function also defined four types of information, and significantly one of these was knowledge-based information (KBI), which was specified in depth in standard IM9.

This emphasis was not accidental: JCAHO’s IM Task Force included three representatives from MLA who ‘advised JCAHO in creating the KBI standards that formed part of the revised IM9 chapter’. Rand and Gluck (Citation2001, p. 26) described four areas in which the Task Force members successfully argued for the inclusion of specific reference to librarians and libraries in the final revision of the 1994 Accreditation Manual. Dalrymple & Scherrer also noted that members of the JCAHO IM Task Force and many MLA members had ‘worked to enhance the importance of the library and its place in the JCAHO standards’ (Citation1998, pp. 15–16).

Reaction by the US health library profession to these changes was positive, as it became clear the revised approach could provide many more opportunities for librarians. Doyle (Citation1994, p.85) commented:

Librarians will only be seen as true health care professionals if they make contributions to the organization outside of the library itself. Active participation in hospital committees, especially those relating to continuous improvement is very important.

Rand & Gluck also argued that librarians who chose ‘proactive’ roles would find many areas apart from the library in which their information management skills could be applied to JCAH functions (p. 27). Dalrymple & Scherrer asserted that the intent and structure of the new accreditation standards offered an expanded organisational role for librarians and library services: in education, performance improvement, leadership, human resources and management of information (Citation1998, pp. 15–16). Schardt concluded: ‘The hospital library’s most important contribution to the accreditation process may be in applying knowledge-based information resources and services to all pertinent chapters in the Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals’ (Citation1998, p. 507).

Consultation between accrediting bodies and health library representatives appears to have continued across North America and in England since that time. The US Medical Library Association recognises the Joint Commission as an ‘allied’ organisation; it appoints an official representative to the Joint Commission (Medical Library Association [MLA], Citation2019). Similarly, the Canadian Health Libraries Association/Association des Bibliotheques de la Sante du Canada (CHLA/ABSC) designates an official representative to Accreditation Canada (Canadian Health Libraries Association/Association des Bibliotheques de la Sante du Canada [CHLA/ABSC], Citation2019). In England, health library practice in public hospitals is embedded in Health Education England’s national policy, NHS Library and Knowledge Services in England (Citation2016). This policy has three key objectives: to develop NHS librarians and knowledge specialists’ expertise in gathering research-based evidence for use in decision-making in the National Health Service; to enable free access to library and knowledge services for the NHS workforce; and to bring NHS library and knowledge services into a coherent proactive national service that meets the needs of the NHS workforce.

Library Quality Assurance Standards

Health library professional bodies have long had an active interest in self-regulation and development of standards. The chronology by Harrison, de la Mano, and Creaser (Citation2014, pp. 14–23) traces these from 1953 to the mid-2000s. Harrison et al. positioned National Health Libraries standards in the broader context of increasing demands for health system accreditation: These [standards] have been considered ‘a necessary tool for measuring the quality of health library programs and services’ (Citation2014, p. 2).

In Europe, Ibragimova and Korjonen analysed the role of evidence and information governance (‘traditional fields of librarians’ expertise’, Citation2019, p. 66) in the context of Clinical and Health Governance (C/HG) of health organisations, an area that is critical to health services accreditation. They researched the ways that European health libraries contributed to specific components of C/HG, with a view to developing measures that would indicate impact in these areas. They concluded (p. 86): ‘librarians in health and hospital libraries do not only provide services and products within the library environment, but have greater engagement and participation in wider activities of their organisations’. Their research demonstrated that there were three groups of library activities that supported C/HG in healthcare organisations: infrastructure (staff and resources); programme management (library products and services); and, direct participation (needs assessment, committees, audits, HTA etc.).

Australian Health Librarians and Accreditation

Current requirements in the Australian accreditation standards focus on functions, following the JCAHO standards model. Service units (e.g. library services) submit evidence of their performance against the NSQHS Standards. In the first edition (ACSQHC, Citation2012) there was an Information Management (IM) standard, one of a handful which sat outside the core quality standards group. The IM standard was phrased more broadly than the US IM9 equivalent – for example, it referred to the collection, storage and use of information for strategic, operational and service improvement purposes. The second edition of the NSQHS Standards (ACSQHC, Citation2019), however, does not contain a specific IM standard; this function has been absorbed into the current eight standards.

Published examples of the proactive work of Australian health librarians for accreditation at their sites are provided by Cotsell (Citation2014), Beck-Swindale (Citation2016) and Orbell-Smith (Citation2017). These give a flavour of the wide span of standards to which the library services contributed. The professional bodies Health Libraries Australia (HLA) and Health Libraries Inc. have initiated detailed research and advocacy for the profession (reports and submissions derived from this work are listed on the respective websites). Most recently, HLA has developed and updated the profession’s specialist competencies (Australian Library and Information Association [ALIA], Citation2018) and the fourth edition of the Guidelines for Australian Health Libraries (ALIA, Citation2008) is currently under review.

Australian health library managers have identified the need to participate in the process of developing accreditation standards for the information management function in hospitals. ‘Recognition of hospital libraries as part of the national hospital accreditation process’ emerged as a key target in 2015 when senior hospital librarians discussed strategic priorities (Holgate & Schafer, Citation2015a, Citation2015b). In the following year, managers resolved to take an active role with evidence for accreditation and to align their efforts with the NSQHS Standards (Taylor, Citation2016, p. 29). The HeLiNS research was developed with this purpose in mind.

Objectives of the HeLiNS Research

The HeLiNS Research aimed to explore and record the contribution that health libraries make to the achievement of hospital accreditation, through their support of the Australian NSQHS Standards.

Objectives

Specific objectives of the research were:

Objective 1

To explore ways in which health libraries assist their organisations in achieving accreditation.

Objective 2

To design expert searches that will assist organisations in keeping current with the latest research-based literature (evidence) pertinent to the NSQHS Standards.

Objective 3

To assess the availability of resource materials referenced in NSQHS Standards documentation and workbooks.

Method

Two component studies were designed to address the three objectives. Each study comprised two parts.

Study 1: Survey of Hospital Libraries’ Accreditation Activities and Case Studies (Addressed Objective 1: to Explore Ways in Which Health Libraries Assist Their Organisations in Achieving Accreditation)

Study 1, Part 1: Survey

A national, web-based survey using SurveyMonkey (see Appendix A) collected data about current activities undertaken by hospital libraries in support of their organisations’ achieving accreditation against the NSQHS Standards.

Following a pilot in early 2017, the survey was emailed directly to hospital library managers and also distributed through two national library-centric e-lists (ALIAhealth and HLI e-lists).

The survey opened in mid-March 2017 and closed in mid-April 2017. During this time, reminders were sent to individual library managers.

The survey comprised 19 questions, in three sets:

Questions 1 to 4 asked about basic demographic information such as the Australian National Union Catalogue (NUC) symbol, type of hospital (public/private), state/territory, and location (metropolitan/regional/rural);

Question 5 asked about general library activities undertaken by libraries which affected all 10 NSQHS Standards, and questions 6 to 15 requested information about specific library activities undertaken which addressed one standard in particular;

Questions 16 to 19 covered additional topics, asking library managers:

whether accreditors had commented on the role of the library during their last accreditation visit;

to nominate their activities for a more in-depth case study;

to provide the names of other hospital libraries who were actively involved in supporting the NSQHS Standards, general comments or any other information.

Study 1, Part 2: Case Studies

Following the initial survey, case studies that elaborated on exemplary activities that libraries had undertaken in support of their hospital’s accreditation were developed. Key informants and self-nominated individuals who were willing to undertake more in-depth questioning about their particular programs and activities agreed to participate through phone or in-person interviews. Each interview lasted approximately 1 hour and followed a standard, 12-question schedule (See Appendix B). Eight case studies based on the interviews were developed between August and December 2017.

Study 2: Analysis of Availability of Documents Referred to in the NSQHS Standards and Designing Live Search Strategies

Study 2, Part 1: Analysis of Availability of Documents Referred to in the NSQHS Standards (Addressed Objective 3: To Assess the Availability of Resource Materials Referenced in NSQHS Standards Documentation and Workbooks)

Continuous improvement in quality and safety is a core concept of NSQHS accreditation. Information, particularly evidence-based information from external sources is required for assessing and improving the quality of clinical care. Much of this information appears in published medical literature, such as clinical trials, systematic reviews, and reports. Access to this information for hospital staff may not be uniform across Australia.

The aim of this part of the research was to gain an understanding of access to medical information relevant to NSQHS accreditation, as experienced by staff in Australian hospitals.

Citations of journal articles, books and other documents referenced in NSQHS publications were used as a representative sample of literature relevant to accreditation. Thirty-two NSQHS publications were selected and 322 citations were collated.

Online access to these citations was then determined and recorded as being either: ‘freely available on open access’, ‘available via a state-based information portal’, and/or ‘available via a library subscription’.

Using a convenience sampling method based on a total population of 95 hospital libraries identified in the national census (Kammermann, Citation2016), a stratified sample of 54 hospital libraries was created. The sample was designed to provide an approximately proportional mix of large, medium and small hospitals (public and private); metropolitan, regional and rural/remote areas; and covering all states/territories.

Thirty-two participants responded to the invitation to report on the availability of resource materials referenced in NSQHS Standards documentation and workbooks in their libraries/information services and state/territory-based portals (collections). Open-access availability in Australia was recorded for all participants by the Study Leader.

Limitations of Study 2, Part 1

The research was designed to gather data on current access to resources cited by the NSQHS Standards, in order to gain knowledge on how libraries contributed to and supported the accreditation of their respective health services. It was expected that this would be further understanding of the complex contribution of state/territory government-provided information portals, other state/territory-funded library resources and individual library services’ resources (public and private hospitals) which varies across jurisdictions. Given this was an exploratory study that focused on the availability of resource materials, economic analysis was considered out-of-scope for this research project.

It should also be noted that no analysis of interlibrary loans data was undertaken in this research. Any hospitals without a library would be unable to use inter-library loan/document delivery networks, thus further reducing the accessibility of citations which were not available either on open access or through a state/territory/national source, and increasing the ‘evidence-accessibility gap’ between hospitals with libraries and those without libraries. It is therefore likely that this gap has been underestimated.

Study 2, Part 2: Tested Search Strategies (Addressed Objective 2: To Design ‘Expert’ Searches That Will Assist Organisations in Keeping Current with the Latest Research-Based Literature (Evidence) Pertinent to the National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS) Standards)

Search strategies were designed for eleven topics to retrieve citations and the latest evidence relevant to the National Standards. An initial list of more than 30 topics was compiled by experienced health librarians, based on their practical experiences in supporting clinicians and other hospital staff in meeting accreditation standards. This was refined to a final list of eleven topics, according to perceived community need and practicality of execution. A Search Strategies subgroup was formed to support and advise the research librarian who led the development of the topical search strategies.

The searches were designed for the PubMed database, as this database is freely available online and provides wide subject area coverage relevant to the topics of interest.

For each of the 11 topics, a search strategy, limited to English citations from the previous 5 years, was placed on a ‘searches’ website where a user could execute the search in PubMed by clicking on a hyperlink. Six variations on each search topic were developed and made available on the website. These included searches limited according to refined criteria, such as ‘review articles only’, ‘most recent 12-months citations’.

The search strategies were designed over a four-month period, during which retrieval was tested by comparing the results against those derived from:

a sample set of references that had been compiled for each topic by the Project Team, Reference and Search Strategy Groups;

existing search strategies constructed by other health librarians.

Results

Study 1 Results

Study 1, Part 1: Survey of Hospital Libraries’ Accreditation Activities (See Appendix A for the Complete List of Survey Questions)

Of a possible 95 Australian hospital library services, 64 library managers completed the survey resulting in a 67.3% response rate for this part of the study. Ninety per cent were from the public sector and 10% were from the private sector.

Respondents were located in all states and territories (see ) and spread over metropolitan, regional and rural areas (see ). Numbers of respondents were approximately proportional to the distribution of total hospital libraries in these locations (as identified in the national census, Kammermann, Citation2016).

Table 1. Study 1: Survey respondents’ state/territory location.

Table 2. Study 1: Survey respondents’ area location.

Thirty-five respondents stated that they undertook ‘general library activities affecting all 10 Standards’. These were grouped thematically as:

Literature searches (n = 25)

Collection management (n = 20)

Training (n = 19)

Document delivery (n = 19)

Alerts (n = 16)

Twenty-seven respondents stated that they did not undertake ‘general library activities’ that affected all 10 Standards.

Activities and services that were mentioned multiple times included research support, reference services, LibGuides, dedicated subject guides for each standard, and evidence summaries.

In addition to the information about the ‘general library activities affecting all 10 Standards’, respondents identified and elaborated on their library activities relating to each specific NSQHS Standard in the next set of questions. Responses for each of the Standards are listed below.

Standard 1: Governance for Safety and Quality in Health Service Organisations

45 positive responses, 48 comments, including:

A range of library services conducted which related to governance documentation (guidelines, policies, procedures, etc.)

Ratification of governance documentation

Attending policy committee meetings

Looking after Australian Standards subscriptions organisation-wide

Development of corporate copyright policy

Digital repository for reporting research

Having a library advisory committee

Attending quality committee meetings

Standard 2: Partnering with Consumers

36 positive responses, comments, including:

Consumer Engagement Program sits under the Library & Literacy Department – includes the WISE program (Written Information Simply Explained)

Health Literacy Champions Program (6 modules)

Coordinating a Public Lectures series on a broad health topics

Setting up/maintenance of a patient library in the cancer unit

Linking to Consumer Health Information (including multilingual websites)

Consumer Information & Health Literacy Committee

Developing a policy on Using Information from the Internet

Digital repository

Historical repository – making the history of the organisation accessible to consumers

Health Literacy Week

Partnerships with other local health organisations/professionals

Program to introduce carers to online health information resources

Public resources page on the organisation’s website

Patient information delivered via the Patient Portal

Words for Wellbeing Program (public library partnership)

Separate consumer library – books, pamphlets, PC access, librarian, consumer resource website

Standard 3: Preventing and Controlling Healthcare-Associated Infections

32 positive responses, 34 comments, including:

Dedicated Hand Hygiene search filters in JBI and CINAHL

Library organises monthly Grand Round – topics have included information on this standard

Standard 4: Medication Safety

40 positive responses, 41 comments, including:

Resources purchased as listed in the Standard (print and online)

Hospital-wide survey on use of medication resources

Organising purchase of departmental collections (print and online)

Attending Medication Safety meetings

Dedicated Medication Safety search filters in JBI & CINAHL

Contributing content to medication newsletter

Combined policy with Pharmacy on medication resources

Training in use of drug resources

Library organises monthly Grand Round – topics have included information on this standard

The Library hosts the state-wide antimicrobial tool in the Library’s Digital Repository

Standard 5: Patient Identification & Procedure Matching

16 positive responses, 15 comments, including:

Working on animated tool with Quality Department – will be launched in May 2017

Standard 6: Clinical Handover

26 positive responses and comments, including:

Helped create an eLearning package on Clinical Handover for the organisation’s Learning Management System

Dedicated library bulletin on this topic

Scoping report on clinical handover for hospital to primary care

Standard 7: Blood & Blood Products

21 positive responses, 19 comments, but no notable library activities in addition to the ‘general library activities’ detailed in the earlier question.

Standard 8: Preventing & Managing Pressure Injuries

30 positive responses, 28 comments, incuding:

Dedicated Pressure Injuries and search filter in JBI & CINAHL

Library session on wound care resources incorporated into formal wound care course.

Standard 9: Recognising & Responding to Clinical Deterioration in Acute Healthcare

30 positive responses, 28 comments, including:

Library organises monthly Grand Round – topics have included information on this standard

Working with Advance Care Planning Team on information literacy project for 2017/18

Standard 10: Preventing Falls & Harm from Falls

35 positive responses, 33 comments, including:

Falls prevention display during Falls Week

Dedicated Falls Injuries search filters in JBI & CINAHL

Responses to Question 16

This question asked about accreditors’ comments and feedback made at a recent hospital accreditation visit. In preparation for a visit, hospital libraries along with other departments, contribute written evidence about programs and services and other activities they provide to support their hospitals’ accreditation. These comments from the surveyors are taken from statements made during meetings with the accreditors (attended by the librarians), at open forums at the end of the visits, and in surveyors’ written reports.

There were 32 responses to the question about accreditors’ comments during the hospitals’ most recent accreditation visit. Ten discussed how the library was seen as valued, using terms such as ‘essential’, ‘favourable’, ‘accessible’, ‘providing linking ability’, ‘of a high standard’ and ‘extensive’. Some specific library projects were named:

‘Fundamentals of research’ training program

Digital Repository

‘Pathways’ consumer engagement project

‘WISE and Consumer Representative’ consumer engagement programmes

There were 30 respondents who agreed that they would be willing to be contacted to explore their activities to develop more in-depth case studies.

Study 1, Part 2: Case Studies

The eight case studies that were developed following the initial survey conducted in Part 1 of Study 1 are reported in full and available on the ALIA/HLA web page (https://www.alia.org.au/helins-health-libraries-national-standards-outcomes-national-research-project)

The case studies covered a variety of topics and standards, chosen because they were unique examples that highlighted health librarians’ competencies and value relevant to their library and healthcare organisational contexts. These activities are worth highlighting because they demonstrate to administrators, other health professionals, health librarians and accreditors, the range of activities undertaken by hospital librarians. At the same time, they offer peer learning opportunities for other hospital librarians.

The case studies covered a variety of topics and standards. below gives a broad overview.

Table 3. Study 1: Case studies showcasing unique activities of hospital libraries supporting their hospitals’ accreditation.

Study 2 Results

Study 2, ‘Analysis of availability of documents referred to in the NSQHS Standards and designing live search strategies’ addressed Objectives 2 and 3.

Study 2, Part 1: Analysis of Availability of Documents Referred to in the NSQHS Standards

Overview

There were 35 organisations that provided data for this part of Study 2 (see ). Their results were collated to assess the availability of fulltext in the sample (‘test’) set of references. (The data sources from which the sample ‘test’ set of 322 references were derived are listed in Appendix C). The 322 references comprised:

306 journal articles, from 157 journal titles. Year of publication ranged from 1972 to 2016

4 Therapeutic Guidelines

4 standards (3 Australian, 1 ISO)

8 other publications/reports.

Table 4. Study 2: Organisations providing data to analyse the availability of references in the sample (‘test’) set of references.

Each of the state/territory-wide health library/information services (n = 4) and state/territory government-provided information portals (n = 3) was counted as a single data provider. Hospital libraries from the larger states whose libraries did not provide data as a single network (i.e. Queensland, n = 6; Western Australia, n = 6; New South Wales, n = 7; Victoria, n = 9) each provided data for their own libraries. Their results were averaged within their jurisdictions according to their hospital’s size (small, medium, large) and location (metropolitan or regional).

Summary of Results

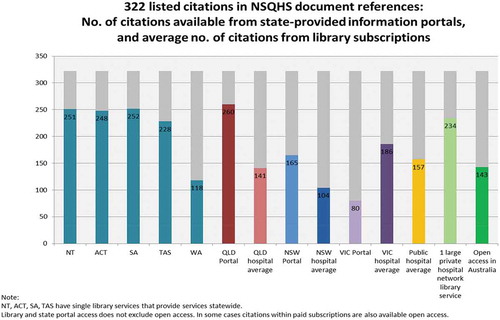

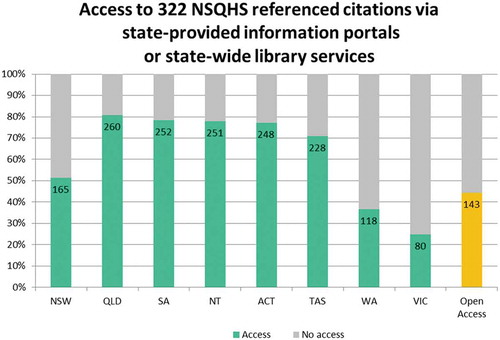

The results of Study 2, Part 1 are summarised in – below.

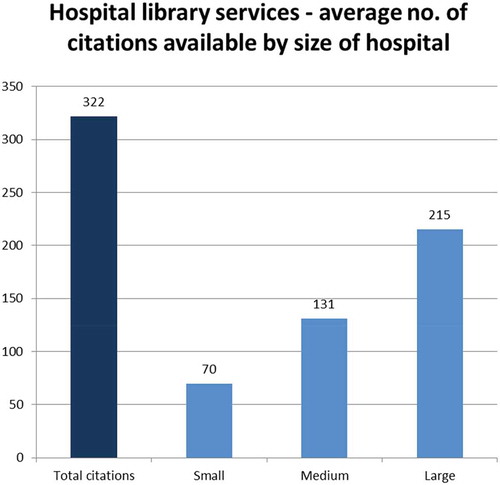

Figure 1. Number of citations available from state/territory-wide sources, hospital libraries (averages), a private hospital network, and national open access.

shows that of the total of 322 citations in the sample ‘test’ set, 143 (44.4%) or less than half of the total citations were available on open access in Australia. The ‘open access’ category includes any citations that were available through the Cochrane Library, which is the only nationally subscribed health resource that is accessible by anyone within Australia.

For more than half of the citations in the sample set that were not available via open-access (i.e.179 citations, 55.6%), accessibility of fulltext from the different sources varied greatly.

The variation in accessibility to more than half of the evidence resources was directly related to subscriptions (i.e. access rights) and whether or not an organisation paid for employees to access particular resources. The results show that there were three main factors that could influence accessibility:

location or jurisdiction (and thus having access to state/territory-wide library/information services or state/territory government-provided information portals) (see );

size of hospital (see ); and

whether the hospital had its own library service.

As there was only one large private hospital network library which provided data, the resultant data cannot be generalised to other private hospitals as it is likely this case would overestimate the number of citations available in other smaller private hospitals, especially as some may not have their own library services.

Figure 2. Citations available via state/territory-wide library and information services and state government-provided information portals.

shows that there was a large range of citations available from state/territory-wide library and information services and state government-provided information portals. The greatest number of citations (260) from a single provider was available from Queensland Health’s information portal (Clinical Knowledge Network, CKN), followed by the South Australia Health Library Service (SAHLS, 252) and the Northern Territory Health Library (251). The lowest number of citations (80) was from Victoria’s Clinicians Health Channel (CHC).

also shows the range of citations available from public hospitals (averages) in each state – the highest is Victoria (186), the lowest is NSW (104) with the average being 157.

It is likely that these variations in the balance of sources and availability reflect the different aims, budgets and purchasing priorities among the state/territory providers (See Appendix D for a summary table of the different providers).

It should be emphasised that the main aim of this research was to explore and record the contribution that health libraries make to the achievement of hospital accreditation. As noted in the Limitations section of Study 2, an analysis of the many complex and inter-related factors affecting ‘collecting’ policies and selection decisions, and therefore the probable reasons for this variability, were considered beyond the scope of this research. There is, however, a discussion of the implications of this variability in the Discussion section.

The study showed that size of hospital has an influence on the accessibility of citations. shows that on average, large hospital libraries provided access to a greater number of citations (215), than medium hospital libraries (131), and small hospital libraries (70).

An additional factor affecting access to evidence resources is whether the hospital has its own library service. As noted in the Limitations section of Study 2, only hospitals with a library would be able to use inter-library loan/document delivery networks, but an analysis of interlibrary loan/document delivery data was considered beyond the scope of this research. It can be inferred, however, that hospitals without a library would be further disadvantaged as they would be unable to tap into the national and international resource sharing services. Health professionals in the public sector would be dependent on the state/territory-provided sources and open access materials, and those in the private sector would only be able to view open-access materials. It is therefore likely that the ‘evidence-accessibility gap’ has been underestimated for smaller hospitals, private sector health facilities, and for any hospital without their own library service.

Study 2, Part 2: Tested Search Strategies (Addresses Objective 2 to Design ‘Expert’ Searches That Will Assist Organisations in Keeping Current with the Latest Research-Based Literature (Evidence) Pertinent to the National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS) Standards)

Eleven search strategies addressing the major topics covered in the NSQHS Standards were designed and tested using the PubMed database. The search strategies aimed to retrieve the latest evidence that would assist hospital clinicians, quality and safety, and other hospital staff in making their practices and policies (including clinical guidelines/protocols/procedures) compliant with the requirements of the Standards. The ultimate goal is thus to help all staff to maintain and continuously improve quality and safety in their organisations.

The search strategies focused on the following topics:

Advance care planning

Blood management

Clinical handover

Delirium

Deteriorating patient

Falls prevention

Infection prevention

Medication safety

Partnering with consumers

Pressure injuries

Wound management

The live searches may be accessed at: https://www.alia.org.au/groups/HLA/nsqhs-standards-live-literature-searches

Discussion

Responsibilities of Hospital Libraries

Health libraries serve the business purposes of their organisations. In a hospital, the ultimate goals relate to patient care and population health, and the scope and focus of hospital libraries’ activities are defined by reference to these primary areas of functional responsibility.

In general, hospital library services and systems operate in three main areas:

collections and knowledge resource management;

reference, research and information literacy training to support evidence-based practice;

collaboration, partnerships and networking to increase the knowledge base and capacity of individual library services.

With regard to the first area (collections and knowledge resources management), hospital libraries are accountable in their organisations for ensuring the efficient delivery of evidence-based information for patient care decision-making and policy development. Research-based, published evidence, together with internally generated policies, procedures and data-derived evidence, underpin all hospital employees’ decision-making and a hospital’s governance framework.

Within their organisations, hospital libraries develop their services and systems strategically, so they are tailored to meet the information needs of their particular client groups. Client groups’ information needs may vary according to a hospital’s location, clinical specialities and a hospital’s strategic priorities.

Hospital libraries can only ensure the delivery of efficient and effective services and systems when they are adequately resourced and staffed by professional subject-specialist librarians. This functional capacity, built on the expertise of staff and the ability to access collections of up-to-date health information and knowledge resources, is integral to an organisation’s governance framework. Thus, hospital libraries help to ensure that the work of a hospital’s employees – clinicians and other healthcare professionals, managers, administrators, educators, researchers, policymakers – is evidence-based and complies with safety and quality standards.

Hospital Libraries’ Accreditation Activities

The survey of health library managers in Study 1 sought information on how libraries contributed to accreditation – firstly, in general and relating to all the NSQHS Standards, and secondly, for each of the standards which health services are required to meet. Responses to these questions indicated that, on average, half of the libraries undertook activities specifically directed to helping achieve accreditation. The two highest positive responses were for contributions to Standard 1 – Governance for Safety and Quality (75% of libraries) and to Standard 4 – Medication Safety (66%). The two lowest positive responses were for Standard 5 – Patient Identification and Procedure Matching (27%) and for Standard 7 – Blood and Blood Products (35%).

Respondents listed a large number of activities as examples of their participation. Some of these could be styled conventional ‘library’ activities (e.g. reference and research services, literature searches, collection management, information literacy/user education, document delivery/interlibrary loans, and current awareness alerts). Some were detailed library ‘extension’ programs (e.g. research or institutional repositories, literature search filters, updating drug information material held in departments and clinical areas, linking to consumer health online resources). Others were notable examples of proactive library outreach in their organisations and communities, such as participating in policy or quality committees, organising public lectures for health consumers, promoting health literacy, and contributing to staff e-learning packages.

The range of activities illustrates the extent of library staffs’ interest and efforts in being fully engaged in quality and safety improvement at their health services. It also exemplifies a broadening of the health librarian’s role, moving from being collection ‘guardian’ to information manager and knowledge specialist in the healthcare organisation.

Nearly half the surveyed library managers, however, indicated they did not contribute to accreditation through activities relating to specific NSQHS Standards. Participation rates were notably low for the Standards which were aligned with routine clinical activities (e.g. patient identification) and the more highly specialised areas such as Blood Management. Low staff numbers and capacity might also be a factor for some health libraries. Nonetheless, it is concerning that a high proportion of the responding libraries did not see their activities as contributing to accreditation. It is possible that some respondents interpreted the question very literally, feeling that their activities would be required to show an explicit and direct link to one of the NSQHS requirements, and thus discounted some eligible activities. The survey question schedule did not probe reasons for not contributing to accreditation: this omission has limited the opportunity to learn from non-participants.

The eight case studies selected for this study illustrate a range of activities covering five of the ten NSQHS Standards topics. Five case studies referred to Standard 2 (Partnering with Consumers); three cases were relevant to each of Standard 1 (Governance) and Standard 4 (Medication Safety); one case study covered Standard 3 (Healthcare Infections), and one case study was relevant to Standard 8 (Preventing and Managing Pressure Injuries). The case studies highlight imaginative, collaborative or ground-breaking programs, each with sufficient detail to enable replication or adaptation. They will form the nucleus of a database of case studies which will be developed as an openly accessible peer-learning resource for health librarians.

Availability of Documents Referred to in the NSQHS Standards

Study 2, Part 1 addressed the third objective of the research, which was to analyse the availability of the sample ‘test’ set of 322 citations referenced in documents and workbooks in the NSQHS Standards.

Less than half of the citation sample ‘test’ set was available in Australia on open access on the internet (no direct cost to the user); access to more than half of the citations (the remaining 179 citations behind paywalls) varies for staff in health services. A representative sample of 28 health libraries around Australia provided data on the availability of the 322 citations in their collections. The study shows that availability depends on state/territory and metropolitan/regional location, size of hospital (large, medium, small), and whether or not the hospital has a library service.

The study shows that for accreditation purposes, hospitals with either no, or very small library services, or no access to a state/territory government-provided information portal will be significantly disadvantaged in information access, and an ‘evidence-accessibility gap’ exists.

In practice, these results indicate that:

a clinician in a rural hospital in New South Wales, Victoria or Western Australia would be unable to access scores of the citations in the test set, while a metropolitan hospital clinician in the same state may have ready access to most of them;

a clinician in a small to medium Victorian public hospital would have access to a lower number of citations than would a colleague in a similar-sized public hospital in the Northern Territory, Queensland, Tasmania or South Australia;

a clinician in a non-public hospital with no library service would only be able to access the open-access citations, i.e., less than half (143) of the citations in the test set.

It is further suggested that these differing and unequal levels of access will also apply to the broader health literature and evidence-based information relevant to accreditation and the NSQHS Standards in general.

In examining the provision of resources, the results of the data analysis point to three corollaries:

Health services that have a professionally staffed library service will have demonstrably greater access to information resources that can assist continuous improvement in quality and safety. At the very least, a library service will be able to utilise the interlibrary loan networks that enable reciprocal borrowing privileges between member organisations.

State/territory-wide library services and state government-provided information portals provide greater and more uniform access to relevant information resources in quality and safety; the ‘performance’ (in terms of the numbers of citations retrieved) of these portals and services, however, varies considerably by state/territory. Although it was not the intention of the HeLiNS Research Project to compare these models directly, this may be the first multi-state/territory assessment of the ‘performance’ of these information portals/services.

Where state/territory-wide provision of resources is comparatively low, there is an increased need for hospital libraries to fill the ‘evidence-accessibility gap’, pointing to the need for hospital libraries’ resources’ budgets to be maintained at levels that are aligned with local circumstances, i.e. specialisations and needs. Increased responsiveness to a particular hospital library’s clients’ information needs may, in fact, be advantageous in addressing local and more granular requirements. Thus, as long as a basic ‘core’ clinical collection is available, generic and homogenous collections may not be the optimum (and most cost effective) collection development model.

The present research is not intended to be an examination of the content or performance of state/territory-wide information portals, as such work would require consideration of financial and staff number (clinical workforce) information which is confidential to either providers or payers. However, the researchers note the work of other organisations in licencing e-resources for national customer groups. Examples in Australia include the national licence for the Cochrane Library, which is nationally funded by the Commonwealth Government; the Council of Australian University Librarians (CAUL) Electronic Information Resources Consortium for information resources in teaching, learning and research. In the United Kingdom, Health Education England organises a Core Content Procurement process and is currently arranging re-procurement of content for 2019–2022 (ref. http://kfh.libraryservices.nhs.uk/core-content-re-procurement-update/)

The national consortium approach would require consensus on the ‘core’ resources to include, as well as some process to reach agreement on contracting, licencing and sharing costs for general as well as more specialist content.

Tested Live Literature Search Strategies

The second objective of the HeLiNS Research was to design searches that would assist organisations in keeping current with the latest research-based literature (evidence) pertinent to the NSQHS Standards. Search strategies for eleven NSQHS-aligned topics were developed by an experienced health research librarian with advanced expertise in searching for evidence for healthcare. In this work, a pragmatic approach was adopted to ensure extensive internal testing, followed by review by a panel of health librarians with searching expertise and knowledge of the needs and interests of the target audience. The search strategies were designed for utility, but do not aim to be comprehensive. It was agreed they would be titled ‘tested’ not ‘expert’ searches: they are not presented as meeting the standards for objectively derived and validated search filters, although they have been created by librarians with expertise in search strategy design, and existing robust search strategies have been incorporated where relevant (e.g. for reviews or for clinical guidelines).

The searches are presented in a simple user-friendly ‘one-click’ format: the PubMed search script is embedded in a saved search string, which opens the database and runs the search. This presentation style was selected to make the searching as simple as possible for clinical staff, while also allowing more knowledgeable users to add to or adapt the searches according to their specific needs and the databases to which they subscribe.

It is hoped health librarians will use and highlight the searches widely in their organisations, embedding the links in library websites, subject guides and resource lists, as well as promoting the searches when teaching or demonstrating database searching.

Involvement in the Accreditation Standards

The somewhat limited involvement of some hospital libraries in the accreditation standards process noted in the literature review contrasts with the examples of two-way consultation with accrediting bodies that exist in the US, Canada and England.

The current research, however, has resulted in some advances with respect to involvement in the NSQHS Standards. To encourage dissemination of the tested literature searches developed for the research, the Project Team has been successful in approaching the standards peak body, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, with an offer to make the live searches freely available as a resource for the NSQHS Standards. The ‘Live Literature Searches’ are now linked from the Commission’s Resources list (https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/national-safety-and-quality-health-service-nsqhs-standards/resources-nsqhs-standards, linking to the Health Libraries Australia website: https://www.alia.org.au/groups/HLA/nsqhs-standards-live-literature-searches).

The Project Team acknowledges that the live search strategies produced in Study 2, Part 2, require expert maintenance and updating to ensure reliability and currency. Management of the search strategies website has been undertaken by Health Libraries Australia. This will ensure the strategies are periodically updated and will simplify the process of adding more searches as new topics arise. Usage and feedback about the searches will be the key metrics for this initiative; hence, ‘in-house’ hosting would be the optimum plan.

Future Directions

For the Australian health library community, another possible direction could be the development of specific indicators for health information services in the Australian context. Such measures could comprise a ‘checklist’ for those compiling evidence for accreditation visits, or they could be included in the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s nascent Australian Health Performance Framework (AHPF), which enables reporting on health and care indicators in the Australian setting (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2019). Currently, the AHPF lists clinical indicators (i.e. those directly affecting patient care). Future releases are planned to incorporate additional indicators, based on input from stakeholders, and authorities such as the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. The Health Performance Framework’s conceptual diagram already includes ‘Information, research and evidence’ as a component of the health system context: this could provide a basis to develop more far-reaching quality indicators for health library and information services.

Another way of making the contribution of health librarians to health services accreditation more visible could be to follow the European lead and develop a framework or tool for gathering evidence of impact in the area of health services governance standards. This tool could align with the forthcoming fifth edition which will revise the current Guidelines for Australian Health Libraries (ALIA, Citation2008).

Conclusion

The HeLiNS Research Project has demonstrated that Australian health librarians make a substantial contribution to support their organisations in successfully achieving accreditation. The research focused on two broad areas: the services provided by hospital librarians and access to the evidence-based literature relevant to the NSQHS Standards.

Study 1 found that there is a range of services and activities that hospital librarians perform which directly affect the achievement of the NSQHS Standards. Eight detailed case studies have been documented so that others in similar circumstances may learn from and apply these examples.

Study 2 of the research found that there were varying levels of access to fulltext in the sample ‘test’ set of citations, indicating a high probability that there are varied levels of access to evidence-based information relevant to NSQHS Standards in general. Study 2 produced 11 live searches on topics relevant to the Standards. The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care’s endorsement of the ‘Live Literature Searches’ as a Resource for the NSQHS Standards intrinsically recognises the value of health librarians’ professional expertise and contributions to hospital accreditation.

In conclusion, the research has shown that hospital librarians contribute in a variety of ways to hospital accreditation, making them integral to a hospital’s quality and safety strategy. There is not, however, a ‘level playing field’ in Australian hospitals in relation firstly, to the availability of services provided by professional librarians in well-resourced library services, and secondly, in having access to the literature that provides the evidence base for continuous improvement in quality and safety.

This study has suggested that a hospital library’s functional capacity is diminished if it is under-resourced in terms of staffing or in having the ability to provide access to evidence-based information and knowledge resources.

The research has further suggested that hospitals without a library service, or with limited library services, will be operating in an environment where there is an ‘evidence-accessibility gap’, and may be at a disadvantage and not performing as well as they could in regard to NSQHS Standards accreditation, and safety and quality systems.

The research received ethical approval from the ALIA Research Committee on 30 January 2017.

Appendices

Acknowledgments

Health Libraries Australia (HLA) and Health Libraries Inc (HLI) were awarded the 2016 $4,800 ALIA Research Grant. This collaborative research, known as the HeLiNS (Health Libraries for the National Standards) Research project was coordinated by Ann Ritchie (Convenor HLA) and Michele Gaca (President HLI). Gemma Siemensma and Jeremy Taylor led the two component studies, and Sarah Hayman conducted one part of the second study. (HLA and HLI each contributed $5000 to undertake the two component studies.) Cecily Gilbert was the Project Officer. A national reference group comprising representatives from all states and regions was convened to ensure the study had national relevance (see Appendix E). The research received ethical approval from the ALIA Research Committee.

Disclosure statement

There are no potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ann Ritchie

Ann Ritchie has many years’ experience managing health libraries, and until 2017, was the Director, Library and Literacy, Barwon Health (Victoria, Australia). She is now the National Manager, ALIA/HLA, and a consultant specialising in reviewing health libraries. Her professional and research interests are in continuing professional development, mentoring, health literacy, strategic marketing, and publishing.

Cecily Gilbert

Cecily Gilbert works with health informatics researchers at the University of Melbourne, following a long career as a health librarian and informatics professional. She has supported research in health service connectivity planning, falls monitoring technology, and recently collaborated in studies on the concept of the health information workforce.

Michele Gaca

Michele Gaca has had a varied career as an Information / Knowledge Manager, having worked at senior levels in the university, public and private sectors, specifically, research and evidence-based organisations in the disciplines of health, science and technology. Her career focus is to build services that encourage people to continue to learn, grow and be challenged.

Gemma Siemensma

Gemma Siemensma is the Library Manager at Ballarat Health Services. Her work interests relate to research, knowledge sharing and the integration of library resources for seamless access. In this role she ensures that health information is accessible across the health service so that evidence based information is used to help deliver the best clinical outcomes. She is the current Convenor, ALIA/HLA.

Jeremy Taylor

Jeremy Taylor is currently Chief Librarian at St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne. He has worked in the health library field for over 25 years, and has held several positions on committees such as Health Libraries Inc. and VALA.

References

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2012). National safety and quality health service standards. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20170830023505/https://safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/NSQHS-Standards-Sept-2012.pdf

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2019). The NSQHS standards. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2019, September 5). Australia’s health performance framework. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/indicators/australias-health-performance-framework

- Australian Library and Information Association. (2008). Guidelines for Australian health libraries, 4th ed. Deakin, ACT: ALIA. Retrieved from https://read.alia.org.au/guidelines-australian-health-libraries-4th-edition

- Australian Library and Information Association. (2018). ALIA HLA competencies, 4th ed. Deakin, ACT: ALIA. Retrieved from https://www.alia.org.au/sites/default/files/HLA%20Competencies_0.pdf

- Beck-Swindale, T. (2016). Beyond the shelf: Opportunities for connections outside the library walls. Health Inform, 25(2), 21–25.

- Brennan, T. A., Leape, L. L., Laird, N. M., Hebert, L., Localio, A. R., Lawthers, A. G., … Hiatt, H. H. (1991). Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard medical practice study I. The New England Journal of Medicine, 324(6), 370–376.

- Brubakk, K., Vist, G. E., Bukholm, G., Barach, P., & Tjomsland, O. (2015). A systematic review of hospital accreditation: The challenges of measuring complex intervention effects. BMC Health Services Research, 15(280). doi:10.1186/s12913-015-0933-x

- Canadian Health Libraries Association/Association des Bibliotheques de la Sante du Canada. (2019). CHLA/ABSC representative to accreditation Canada. Retrieved from https://chla-absc.ca/chla_absc_representative_to_ac.php

- Cotsell, R. (2014). New role for library in health accreditation. InCite, 35(9), 18.

- Dalrymple, P. W., & Scherrer, C. S. (1998). Tools for improvement: A systematic analysis and guide to accreditation by the JCAHO. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 86(1), 10–16.

- Doyle, J. D. (1994). Knowledge-based information management: Implications for information services. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 13(2), 85–97.

- Flodgren, G., Goncalves-Bradley, D. C., & Pomey, M. P. (2016). External inspection of compliance with standards for improved healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12, Cd008992.

- Flower, M. A. (1978). Toward hospital library standards in Canada. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 66(3), 296–301.

- Foster, E. C. (1979). Library development and the joint commission on accreditation of hospitals standards. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 67(2), 226–231.

- Greenfield, D., Lawrence, S. A., Kellner, A., Townsend, K., & Wilkinson, A. (2019). Health service accreditation stimulating change in clinical care and human resource management processes: A study of 311 Australian hospitals. Health Policy, 123(7), 661–665.

- Harrison, J., de la Mano, M., & Creaser, C. (2014) Health library quality standards in Europe (ELiQSR): A model. Results of an EAHIL 25th anniversary research project. Retrieved from old.iss.it/binary/eahi/cont/7_Janet_Harrison_Full_text.pdf

- Health Education England Library and Knowledge Services. (2016, 29 November). NHS library and knowledge services in England policy. Retrieved from https://kfh.libraryservices.nhs.uk/about-kfh/nhs-lks-policy/

- Holgate, J., & Schafer, R. (2015a). A health library managers’ think tank. Health Inform, 24(1), 18.

- Holgate, J., & Schafer, R. (2015b). Planning a vision for the future - NSW health library managers’ think tank strategy. Paper presented at the 12th Health Libraries Inc. conference, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne.

- Ibragimova, I., & Korjonen, M. H. (2019). The value of librarians for clinical and health governance (a view from Europe). International Journal of Health Governance, 24(1), 66–88.

- Kammermann, M. (2016). The census of Australian health libraries and health librarians working outside the traditional library setting: The final report. Canberra: ALIA. Retrieved from https://www.alia.org.au/sites/default/files/CENSUS%20of%20Aus%20Hlth%20Libs%202012-14_Final%20Report_2016.p

- Lam, M. B., Figueroa, J. F., Feyman, Y., Reimold, K. E., Orav, E. J., & Jha, A. K. (2018). Association between patient outcomes and accreditation in US hospitals: Observational study. BMJ, 363, k4011.

- McIntosh, A., McManus, I., & Party, C. (2015). A timeline through the ages: 40 years of ACHS history 1974-2014. Ultimo, NSW: Australian Council on Healthcare Standards. Retrieved from https://www.achs.org.au/about-us/40-year-anniversary/historic-timeline/

- Medical Library Association. (2019). Allied representatives. Retrieved from https://www.mlanet.org/p/cm/ld/fid=375

- Orbell-Smith, J. (2017). Accreditation: What does it mean to the health library? HLA News(Winter), 1–5. Retrieved from https://read.alia.org.au/hla-news-winter-2017

- Rand, D. C., & Gluck, J. C. (2001). Proactive roles for librarians in the JCAHO accreditation process. Journal of Hospital Librarianship, 1(1), 25–40.

- Schardt, C. M. (1998). Going beyond information management: Using the comprehensive accreditation manual for hospitals to promote knowledge-based information services. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 86(4), 504–507.

- Scrivens, E. E., Klein, R., & Steiner, A. (1995). Accreditation: What can we learn from the anglophone model? Health Policy, 34(3), 193–204.

- Swiers, R., & Haddock, R. (2019, May). Assessing the value of accreditation to health systems and organisations. (Evidence Brief No. 18). Deakin West, ACT: Deeble Institute for Health Policy Research.

- Taylor, J. (2016). Report on the health library managers forum, 8 July 2016. Health Inform, 25(2), 26–30.

- Topper, J. M., Bradley, J., Dudden, R. F., Epstein, B. A., Lambremont, J. A., & Putney, T. R., Jr. (1980). JCAH accreditation and the hospital library: A guide for librarians. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 68(2), 212–219.

- Wilson, R. M., Runciman, W. B., Gibberd, R. W., Harrison, B. T., Newby, L., & Hamilton, J. D. (1995). The quality in Australian health care study. Medical Journal of Australia, 163(9), 458–471.

- World Health Organization; Shaw, C. (2003). Quality and accreditation in health care services: A global review. Geneva: Author.

Appendix A.

Survey of Hospital Libraries’ Accreditation Activities

Question 1: Please enter your NUC symbol/s.

Question 2: What sort of hospital are you?

Question 3: Which state are you based in?

Question 4: Where are you located?

Question 5: Is there any general library activity (activities) which you undertake which affects all of the 10 Standards?

Question 6: Does your Library actively contribute to Standard 1: Governance for Safety and Quality in Health Service Organisations?

Question 7: Does your Library actively contribute to Standard 2: Partnering with Consumers?

Question 8: Does your Library actively contribute to Standard 3: Preventing and Controlling Healthcare-Associated Infections?

Question 9: Does your Library actively contribute to Standard 4: Medication Safety?

Question10: Does your Library actively contribute to Standard 5: Patient Identification & Procedure Matching?

Question 11: Does your Library actively contribute to Standard 6: Clinical Handover?

Question 12: Does your Library actively contribute to Standard 7: Blood & Blood Products?

Question 13: Does your Library actively contribute to Standard 8: Preventing & Managing Pressure Injuries?

Question 14: Does your Library actively contribute to Standard 9: Recognising & Responding to Clinical Deterioration in Acute Healthcare

Question 15: Does your Library actively contribute to Standard 10: Preventing Falls & Harm from Falls?

Question 16: In your last accreditation did the accreditors make any comments that you are aware of that particularly highlight the library or activities which stem from the library?

Question 17: We are seeking Health Library case studies to explore more in-depth the activities that Health Libraries undertake in relation to their hospital accreditation. If you answered YES to any of the previous responses and would be willing for your Library to be a case study please leave your contact details below.

Question 18: We might miss some other fantastic Health Libraries who do great work in relation to their hospital accreditation. If you can think of anyone we should contact please leave details below.

Question 19: Anything else you feel we need to know?

Appendix B.

Template of Questions for Case Studies’ Interviews

Can you tell us about your activity:

Describe activity in detail.

Where did the idea come from?

Who contributes to the activity – any other departments/communities?

How did you plan the activity?

How did you resource the activity, did it need to be budgeted for?

What are your goals/target areas for the activity?

How is it evaluated? What metrics are used to measure change?

How is this different from other libraries or what you used to do before?

How is it supported in the organisation?

What challenges did/do you face with undertaking this activity?

How does this link to the NSQHS Standard?

Did you have any documentation which you can share (reports, links, more information) that we can read/access to help me understand this particular activity?

Appendix C.

Study 2. List of Data Sources from Which The Sample ‘Test’ Set of 322 Citations was Derived

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2014). Accreditation workbook for mental health services. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications/accreditation-workbook-mental-health-services/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2014). Acute coronary syndromes clinical care standard. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications/acute-coronary-syndromes-clinical-care-standard/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2015). Acute stroke clinical care standard. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications/acute-stroke-clinical-care-standard/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2014). Antimicrobial stewardship clinical care standard. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications/antimicrobial-stewardship-clinical-care-standard/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2016). AURA 2016: First Australian report on antimicrobial use and resistance in human health. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/antimicrobial-use-and-resistance-in-australia/aura-2016/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2013). Australian open disclosure framework. Sydney: ACQSHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications/australian-open-disclosure-framework/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2016). Delirium clinical care standard. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications/delirium-clinical-care-standard/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2014). Evidence sources: Acute coronary syndromes clinical care standard. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications/acute-coronary-syndromes-clinical-care-standard/;

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2015). Evidence sources: Acute stroke clinical care standard. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/clinical-care-standards/acute-stroke-clinical-care-standard/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2015). Guide to the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards for community health services. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications/guide-to-the-nsqhs-standards-for-community-health-services-february-2016/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2016). Hip fracture clinical care standard. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications/hip-fracture-care-clinical-care-standard/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2016). National consensus statement: Essential elements for safe and high-quality paediatric end-of-life care. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications/national-consensus-statement-essential-elements-for-safe-and-high-quality-paediatric-end-of-life-care/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2016). National guidelines for on-screen display of consumer medicines. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications/national-guidelines-for-on-screen-display-of-consumer-medicines-october-2016/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2017). National infection control guidance: Non-tuberculous mycobacterium associated with heater-cooler devices. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications/national-infection-control-guidance-for-non-tuberculous-mycobacterium-associated-with-heater-cooler-devices/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (2012). National safety and quality health service standards. Sydney: ACQSHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications/national-safety-and-quality-health-service-standards/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2013). NSQHS guide for small hospitals. Sydney: ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications/nsqhs-standards-guide-for-small-hospitals/