ABSTRACT

The number of systematic reviews published each year has steadily increased over the past decade. At the University of Sydney Library, demand for systematic review support had reached unsustainable levels, and a reimagining of our service model was necessary. This paper documents our journey in using ‘service design thinking’ to develop a user-centred systematic review service. Using design thinking methods, we conducted user research to build empathy and understand the systematic review process from the user’s perspective. Using the principles of service design, we examined systematic review support holistically and reconsidered library services as part of a wider service ecology. We developed a suite of resources, including a service charter and an online, self-service toolkit. We also launched a systematic review mentoring program to increase the number of librarians able to deliver the service. By bringing design thinking and service design together, we were able to examine an old problem from a new vantage point. Through this process we discovered the transformational power of service design thinking and developed new solutions for our local context. We encourage other libraries to also embrace service design thinking to reimagine their own services from a new perspective.

Introduction

Systematic reviews are a form of research (or evidence) synthesis. They follow a methodological approach that includes: formulating a clear research question, creating a comprehensive search strategy, searching a range of databases and grey literature, screening results for relevance and quality, and often, but not always, synthesising results using statistical analysis. They are complex, time and effort consuming, and should be conducted by a team equipped with both domain expertise and methodological expertise (Lasserson, Thomas, & Higgins, Citation2019). Provided they have been conducted rigorously, systematic reviews are considered the highest level of evidence, and are used to inform health decision makers. They have started to gain traction outside the biomedical sciences, and over the past decade, have outpaced the publication rate of traditional, narrative literature reviews. The demographic profile of systematic review authors is also changing, with increasing numbers of postgraduate students writing systematic reviews as part of their degrees. Unlike traditional systematic review teams, students have limited resources and rely heavily on external support of librarians, statisticians, and other experts, who rarely offer their services in a coordinated manner.

At the University of Sydney Library, academic liaison librarians often provide individual consultations for both students and researchers conducting systematic reviews. While a positive experience for individual clients, this form of support was recognised by the library as being resource-intensive and inconsistent Thus, a new approach was required, and importantly, one that considered the service in a more holistic manner. This paper details our journey towards developing a scalable, sustainable, and user-centred systematic review service. We have described our process as ‘service design thinking’, encompassing both the use of design thinking methods and consideration of the entire systematic review ecosystem. Our journey could not be described as quick or straightforward, but it was revelatory for us, resulting in a number of discoveries that have improved the service for both researchers and librarians. Most importantly, the solutions we developed were driven by our environment and users, and should not be taken as ‘one-size-fits-all’. Instead, it is our process and methods that hold the most valuable lessons for other libraries looking to design the most appropriate solutions to reflect their needs and circumstances.

Literature Review

The literature that aided our efforts to create a holistic systematic review service is drawn from three distinct knowledge domains: librarians supporting systematic reviews, approaches to developing user-centred library services, and design thinking in libraries. While each domain has been explored in the literature to varying degrees, we found no existing work spanning across all three and sought to bridge this gap. We’ve introduced ‘service design thinking’ to describe our entire process of conceptualising, implementing and refining our systematic review service. We have summarised the recent literature from each domain below to demonstrate how our work builds on existing scholarship.

Librarians Supporting Systematic Reviews

Most of the literature on systematic review support is written from a health librarianship perspective, discussing the degrees of librarian involvement in systematic review process (Desmeules, Dorgan, & Campbell, Citation2016; Murphy & Boden, Citation2015; Ross-White, Citation2016; Spencer & Eldredge, Citation2018; Toews, Citation2019), the challenges of collaboration in multidisciplinary teams (Nicholson, McCrillis, & Williams, Citation2017), and the impact of librarian involvement on the quality of systematic reviews (Aamodt, Huurdeman, & Strømme, Citation2019). The rise in demand for systematic review support from academics and postgraduate students has not gone unnoticed (Gore & Jones, Citation2015; Hanneke, Citation2018; Wissinger, Citation2018), however very few studies detail how libraries have responded to the issue.

In one study, McKeown and Ross-White (Citation2019) report on how the health library of the Queen’s University, Ontario, Canada, developed ‘a structured service for systematic review support’ (p. 411) in response to increasing demand. Their approach to service design included a literature review and planning meeting, resulting in a two-tiered model; advisory service or collaboration. They also implemented a training program to boost the number of librarians capable of delivering the service, increasing their capacity from 3 to 6 librarians. These activities were supplemented by an online work plan to guide librarians through their initial consultation with researchers, as well as an online subject guide: ‘[w]hen researchers inquire about systematic review support, librarians can email them the link to the LibGuide and encourage them to peruse the content’ (p. 414). At first glance, this service model encompasses many of the elements that we ourselves developed during our journey, with two notable points of difference. Firstly, McKeown and Ross-White detail a traditional, library-centric approach to service design and delivery where all service elements are based on librarians’ assumptions about user needs, leaving the voices of the users unheard. Secondly, their approach, while comprehensive, does not conceptualise their service within a wider service ecology. These two elements, which we consider key to our approach, are drawn from the fields of user-centred design and service design thinking.

Developing User-centred Library Services and Design Thinking

Incorporating users into the process of design is not new to the library and information science (LIS) field. The concepts of user-centred design and user experience (UX) are well documented in the LIS literature, primarily in terms of usability testing (see comprehensive literature reviews in McLaughlin, Citation2015; Tempelman-Kluit & Pearce, Citation2014). Usability testing is limited in its interaction with the user, in that it concerns whether an interface works as intended, and is less about involving the user in the process of the interface design itself. This gap has been filled with such approaches as participatory design and UX, as well as design thinking.

A number of articles have also discussed how design thinking can be used as a method for improving the user experience of libraries (Bell, Citation2018; Luca & Narayan, Citation2016). Often these terms – user-centred design, UX and design thinking – are used interchangeably (Kautonen & Nieminen, Citation2018), but as McLaughlin (Citation2015) pointed out, each of them have individual histories and ‘distinct meanings in specific communities’ (p. 34). For the purposes of this review, it is important to emphasise the difference between a traditional approach to user-centred design as part of human-computer interaction (HCI), as distinct from design thinking methods.

In an insightful study, Culén and Gasparini (Citation2015) set out to establish how the choice of approach affected the design process and its results. The HCI design process is incremental and involves small changes, whereas ‘design thinking offers a possibility for radical innovation through divergent and convergent thinking … and [focuses] on proper framing of the problem (e.g. rather than solving a problem, solve the right problem)’ (Culén & Gasparini, Citation2015, p. 2). The authors concluded that while the two approaches employ different tools and pose different questions, they are ultimately complementary – ‘why is this so?’ in the case of HCI design, versus ‘how can I make this work?’ in design thinking (p. 2). Echoing Culén and Gasparini, Bell (Citation2018) argues that design thinking is the most effective problem finding approach: ‘thinking like a designer involves following a user-centred process that stresses problem finding as much as, if not more than, problem solving’ (p. 5). Though design thinking shares its toolbox with HCI, user-centred design and UX (Meier & Miller, Citation2016), it differs from them in its holistic approach to problem solving and its philosophy. It also offers something unique; the reason for its success lies in its emphasis on empathy, on striking the balance between utility and emotion.

During the process of creating our systematic review service, we found that it was the concept, and more importantly, the practice of empathy, that had the most transformative effect on us as librarians and, by extension, the quality of the service we designed. We’ve found that an integral part of the design thinking process, the concept of empathy, is insufficiently explored in the LIS literature. While some studies talk about changing focus and re-orienting the library towards users in ways that go beyond the usual terminology of user-centred design (Daigle, Citation2013; Harbo & Vibjerg Hansen, Citation2012), the use of the term ‘empathy’ itself is still fairly uncommon. One exception, an article tellingly titled ‘Service empathy’ (Fox, Citation2015), summarises the role of empathy and emotion in service design: ‘what makes a deeply satisfying experience using a tool or a service encompasses not only utility, but also a certain sense of emotional gratification or, at the very least, an avoidance of frustration and anger’ (p. 55). Empathy also requires the designer to share the experience of the user in using the tool or the service. Design thinking as an approach aims to avoid ‘breakage’, by thinking like a fish when designing for a fish and by involving a fish in the design process, to elaborate on Seth Godin’s well-known metaphor (Godin, Citation2006). It is empathy that enables designers to create services for the user, with the user.

Service Design Thinking

‘Service design thinking’ is a user-centred, co-creative, and holistic process that uses the methods of design thinking to understand a wider service ecology beyond its individual elements. The term ‘service design’ itself is often used interchangeably with design thinking, sometimes combined as ‘service design thinking’ (German, Citation2017), and sometimes described as ‘a lesser known cousin of the popular user experience’ (Johnson, Citation2016). Service design offers a bird’s eye view, allowing one to see ‘library processes as systems rather than individual service components’, because ‘users view service as how these components work together to put them in touch with resources needed’(McLaughlin, Citation2015, p.55). Service design thinking aims to understand user behaviour as part of a wider ecosystem (usually whole-of-library), and involves users in the process of creating and improving the service (Marquez & Downey, Citation2015). Where design thinking might be used to create a library mobile app that users find convenient and easy-to-use, service design thinking would explore how this app fits into existing library services as part of users’ overall information-seeking behaviours.

We’ve used the term ‘design thinking’ when describing the range of methods and tools used for conducting our user research and for creating specific objects and learning experiences, such as the systematic review workshops or the online toolkit. We’ve applied the term ‘service design thinking’ to the entire process of conceptualising, implementing and refining a multi-faceted systematic review service, where we brought together specific objects and learning experiences in a holistic and cohesive way. In our journey, we intuitively gravitated towards the holistic premise of service design thinking when contemplating a systematic review service that, although centred at the library, expands beyond it by seamlessly connecting researchers with other parts of the university where help is available. Although this part of the journey is yet to be fully realised, we still conceptualise our endeavours in terms of service design thinking.

Background

The University of Sydney is a research-intensive university spread across multiple campuses, with a strong focus on medical and health research. Academic liaison librarians provide one-on-one research consultations to students and staff as part of their support services. For the team supporting these disciplines, our internal statistics suggest that roughly 35% of consultations relate to systematic reviews. These consultations primarily involve developing a search strategy and providing methodological advice, with few requiring the librarian to work as part of a research team. Postgraduate students are our main clients when it comes to systematic review support, comprising around 77% of systematic review-related consultations. With increasing numbers of students requiring support, and greater awareness of our services among academic staff, the number of consultations continued to increase. Soon, questions arose regarding the sustainability of the service, and a more scalable solution had to be found.

Systematic Review Workshops

To address the growing demand for research consultations, a group of librarians designed a series of workshops aimed at postgraduate students and early career researchers working on systematic reviews in the biomedical sciences. The workshops mirrored the content of similar sessions delivered as part of existing courses with embedded library support. What made the workshops different was their ‘roadshow’ format, allowing the workshop to be conducted on demand at any location, either on campus or at a hospital-based clinical school. In 2016–17, nine workshops were delivered across various locations and were attended by approximately 200 participants, with demand still growing. Although the workshops were originally designed as an interim measure to relieve workload pressures, their success has meant that the library team have continued to deliver them as a standard offering for postgraduate students.

Since our first workshops, a number of articles on designing successful workshops for postgraduate students have been written and support our findings. To start, our choice of a workshop format was in line with user needs, as ‘graduate students prefer to learn research skills through formats they can access on demand or attend when they need them, rather than during class’ (Bussell, Hagman, & Guder, Citation2017, p. 993). Peacemaker and Roseberry (Citation2017) argued that a combination of work as a team – focus on promotion – experiment helped to ensure high attendance numbers and popularity of their graduate workshop series, as did co-presenting with faculty and other support services. To prevent drop-offs, Fong, Wang, White, and Tipton (Citation2016) suggest working closely with program administrators who can encourage their students to attend. The importance of collaboration with academic staff, and especially research supervisors, is also emphasised, as it adds ‘authority and credibility’ (Delaney & Bates, Citation2018, p. 79) to the workshops. Somewhat surprisingly, there is apparently no such thing as too many emails when it comes to promoting library services among postgraduate students, as they prefer to be over-informed than miss an important workshop (Smith et al., Citation2019).

Our first systematic review workshop was a collaboration between the library and the academics from the Charles Perkins Centre, who identified a skill gap among their postgraduate students and early career researchers and approached the library for help. The workshops were initially introduced by a keynote presenter from the host faculty, but as word spread, the need for an academic presenter diminished. Information about the workshops was shared by faculty research administrators via email lists and by postgraduate student leaders on social media. It wasn’t uncommon for supervisors to attend the workshop alongside their students, which further increased the workshops’ credibility.

The workshop was developed by a team of librarians and delivered in a fluid and collaborative team teaching environment. The team followed design thinking principles, especially empathising with the user, which resulted in changes to the materials to suit adult learning styles (see, for example, Mahan & Stein, Citation2014). The principles of prototyping, testing, and iterating were used, as we captured feedback from each workshop and used it to inform the next one. This process shares similarities with Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle (Citation1984), which encourages critical reflection on the practice of teaching. Through this process of iteration, the workshops reduced in length from five hours to three, with breaks, and the content became more user-centred as our participants shared their views on what could be improved. For example, having started with a librarian-selected topic as our example review question, we redesigned our approach to provide live, rapid feedback on each participant’s review question, making the workshop far more personalised and relevant. Discussing the review questions in the workshop also provided an opportunity for peer-to-peer learning and feedback, which was greatly appreciated by participants, who commented on the lack of such opportunities during their studies. The team continued to experiment with the content, finding more effective ways of explaining complex concepts by using infographics and short videos. As our collection of these learning objects expanded, less interactive aspects of the workshop, such as navigating database interfaces, have been transferred to an online module available through the university’s learning management system, Canvas. Our workshops are now delivered as a blended learning experience, where traditional ‘point-and-click’ style content is delivered online, leaving the valuable face-to-face time for higher order thinking skills, such as how to formulate a research question and select a relevant review type.

With most library services rapidly moving online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the workshop is now being delivered via Zoom teleconferencing software. Our understanding of the pedagogy behind different learning and teaching approaches allowed us to make the necessary modifications to translate a face-to-face class into an online format. For example, instead of offering rapid feedback on individual research questions live, we made the feedback available in written form post-workshop. Participants are still able to work on their research questions in small groups using the ‘breakout rooms’ feature. We are exploring ways to integrate other online tools and platforms (Kahoot!, Padlet, Mentimeter) into the workshop to deliver a more interactive user experience. Even in these early days, it seems that the various modes of communication (instant chat, the ‘raise hand’ function, and so on) allow students with different communication styles and preferences to participate in the discussion, at times even more successfully than in a face-to-face class.

User Research

The success of the systematic review workshops, and the iterative nature of their development and refinement, further established the need to develop a comprehensive and holistic systematic review service. From conversations with workshop participants and personal communication with researchers, a picture soon emerged of a stressed, stretched, and under-resourced postgraduate cohort, looking for help in the wrong place and not finding it at the right time. In 2017, the University of Sydney Library embarked on user research to gain a better understanding of the systematic review process from the point of view of researchers. With the help of our learning design graduate, who advised on design thinking methods, a team of librarians developed an online survey and a face-to-face user research workshop. The project was approved by the University of Sydney’s Human Ethics Committee (2018/269) and generated significant amounts of quantitative and qualitative data. For the purposes of this article, we will concentrate on those results that (a) illuminated differences between ‘librarian logic’ and ‘user logic’ (Harbo & Vibjerg Hansen, Citation2012); and (b) were directly acted upon in the development of our service.

Methods and Findings

We adopted a primarily qualitative approach to understand the experiences of researchers working on systematic reviews. This approach is common to social sciences research, as it enables the researcher to be seen as an insider and develop a close understanding of the research setting (Bryman, Citation2003). It is also consistent with the design thinking approach, which involves developing empathy with participants to discover multiple perspectives and imagine solutions ‘that are inherently desirable and meet explicit or latent needs’ (Brown, Citation2008, p. 3).

A preliminary questionnaire was shared in March 2018 to recruit participants for a face-to-face workshop. We received 103 completed responses, primarily postgraduate students in medicine and health sciences, followed by respondents from science, arts and humanities, and engineering. This spread was consistent with the experiences of librarians, who see the most demand from HDR students from the biomedical sciences.

The librarians organised a workshop in May, which was attended by 11 participants with three more interviewed via Skype. Most of the participants were postgraduate students (6) or early career researchers (5), with one mid-career researcher, one senior researcher, and one professional staff member. During the workshop, participants were asked to:

Identify the stages in the systematic review process

Identify the most helpful resources to support the process

Identify pain points of the process

Offer potential solutions

Participants identified stages in the systematic review process using the method of ‘freelisting’ (Wilson, Citation2011). This method is often used to understand users’ mental models, and also allowed us to consider both the frequency and order of the responses. An aggregated summary of those stages follows:

Preparation

Define Research Question

Plan Search Strategy and Select Databases

Develop and Register Protocol

Screen Results

Data Extraction and Appraisal

Analysis and Interpretation

Write and Publish

Steps that librarians saw as important, such as conducting a scoping search or running searches in databases, were not explicitly identified by participants as stages.

Next, we invited participants to list the resources that would help them to complete a systematic review. They provided more than 150 responses, which we grouped into the following categories: peer support, university (institutional) resources, external organisations, effective workflows, software, guidelines, or other support. Peer support (23%), such as access to subject matter experts or colleagues, was identified as the greatest source of help. This category also included mentions of the importance of a cohesive team, and having an involved supervisor. Within institutional resources (19%), the university library received the highest number of mentions. Consultations with academic liaison librarians were seen as a key source of support, with participants also identifying the library’s resource sharing services, collection, and systematic review workshops.

To identify the pain points of researchers, we asked participants to describe the issues they encountered when conducting a systematic review. The most significant issues related to participants’ (mis)understanding of the systematic review process. Interestingly, a lack of understanding of the process was not explicitly identified by participants themselves, but emerged as a category as we coded our findings (e.g., ‘inclusion & exclusion criteria drift/changes (sic) in the process’, (they shouldn’t), or ‘how to exclude body of literature you accidentally pick up’ (by applying selection criteria)). These misunderstandings represent valuable insights into our participants’ ways of thinking, and reveal stumbling blocks that would have otherwise been difficult to capture.

Closely connected to an understanding of the process was the issue of ‘defining a research question’. Our participants described this as ‘finding useful clinical message’ or writing ‘a tractable systematic review’. These issues show that finding the appropriate scope for a review question presents a real challenge to researchers, and they may require additional help while doing so. Another issue that was not directly identified was ‘understanding different types of systematic reviews’, indicating that more training is needed to help researchers to understand which type of review best suits their research question. One of the most surprising findings to us was the issue of ‘checking if another systematic review exists’. From a librarian’s point of view, locating existing systematic reviews on a given topic does not constitute a complex skill, yet this was mentioned six separate times and was clearly an issue for some participants.

To assist with prioritising, we asked participants to vote for the most pertinent sources of help or pain points by using stickers. This technique was used to help structure the user research process and not to generate statistically valid statements. When voting on key pain points, participants often selected issues related to access, availability or affordability of resources, including ‘access to full-text articles’, ‘access to a statistician’, and a ‘lack of available time’. Unlike librarians, researchers see the largest gap in services as access to resources, rather than a lack of knowledge or skills.

Lastly, we invited our participants to explore potential solutions to their identified issues using the ‘brainwriting’ method (Wilson, Citation2013). Brainwriting is a method where participants individually ideate as many different solutions as possible on a sheet of paper. Their sheet is then passed on to other participants in a series of timed stages to build on or refine their solutions, or think of new solutions altogether. We then asked participants to vote on the best idea on the sheet. The university library constituted the most voted for source for the solutions (25 mentions), which included various models for training opportunities and workshops. The preferred mode of delivery was face-to-face, followed closely by online. Librarians constituted a separate category for solutions (8 mentions). One of the most popular solutions in this category was a ‘continuing personalised service delivered by a dedicated librarian’.

The second most popular source for the solutions was software (22 mentions). Related solutions included the library purchasing institutional licences for additional software packages, and the library testing and recommending specific software. The next most popular solution was access to expert colleagues (14 mentions), which included access to subject matter experts, a ‘good’ supervisor, and a buddy/mentor program, delivered as a face-to-face solution. Among other experts, statisticians constituted a popular source of solutions, again with a clear preference for face-to-face delivery. Remaining solutions included gaining free access to Cochrane courses and self-help resources.

Discussion

Despite the relatively small number of participants, the user research workshop provided us with a rich picture of the entire systematic review process as seen by researchers themselves. However, the contribution of librarians to the process, most visible in the development of a search strategy, was noticeably absent from the user-generated list of stages. As we analysed the data, we realised that this omission represents a clear knowledge gap that participants need assistance with, but may not explicitly identify themselves. Some of the most practical findings came from researchers describing the various solutions and pain points they encountered when conducting a systematic review.

Researchers draw on a wide range of different resources or solutions. Our findings illustrate the importance of people – peers, teams, supervisors, and experts – to the success of the systematic review process. The fact that peer support was mentioned more often than software, services, or resources, points to a need to explore ways of facilitating university-wide peer-to-peer connections and learning. For postgraduate students, having an involved supervisor was seen as a key success factor. Having enough time to complete the review, and being deliberate in planning and keeping track of progress, was also critical and needs to be addressed by training programs in the future. While the library and the role of librarians was acknowledged as an important resource, we suspect that the high number of mentions could be partly attributed to a framing effect: the user research was situated in the library and conducted by library staff, which may have influenced participants’ judgements and perceptions.

Researchers encounter various pain points throughout the process, and these are particularly concentrated around the ‘preparation’, ‘plan search strategy and select databases’, and ‘analysis and interpretation’ stages. There was little consistency between the number of mentions and number of votes for each issue, suggesting that researcher needs are highly individualised and there remains a clear role for tailored, individual support. Moreover, the variety of solutions (and modes of delivery) proposed by researchers suggests they are unlikely to have all their needs met by one single form of support. Some of the issues that received a high number of votes, such as ‘selecting relevant terms’, sit well within the area of expertise of librarians. Other issues, such as ‘defining research question’ and ‘understanding inclusion/exclusion criteria’, may be better addressed by academic supervisors and other subject matter experts. This highlights the need for further partnership and coordination of effort between academic supervisors and the library in supporting postgraduate students.

Solutions

Using a design thinking approach proved transformational for our understanding of the scope of our systematic review service. While the library had supported researchers in this area for many years, and that support was valued by library clients, it was provided with limited understanding of the broader context in which researchers operated. Design thinking provided us with the tools to step outside a library-centred conception of the systematic review process, and instead consider it from a researcher, or user-centred, perspective. This allowed the librarian team to gain a rare insight into the thinking process of researchers, and also revealed some surprising frustrations and difficulties along the way. By seeing the process through the eyes of our users, we were able to make sense of our role within the broader systematic review ecosystem and see opportunities for future partnerships.

Systematic Review Service Charter

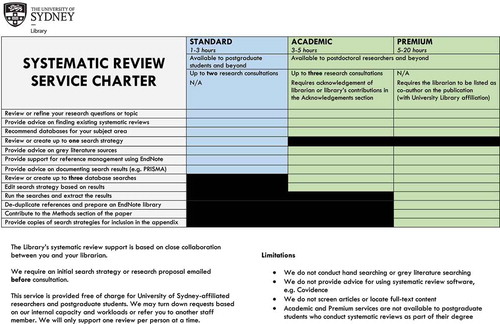

Our user research confirmed that researchers value face-to-face, individualised support for systematic reviews. We planned to continue this service, but acknowledged a need to reach consensus on what those consultations involved and what we were best placed to assist with. A significant finding from our research was that postgraduate students have specific needs as distinct from more established researchers. Postgraduate students may have limited contact with their supervisor, and are often reliant on support services within the university. In developing our service model, it was necessary to differentiate between (a) the support that we would provide for an academic who sees their librarian as a research collaborator; and (b) the support that we would provide for a student whose work would be submitted and assessed.

We decided to communicate our services by developing a service charter, with clear guidelines about the levels of support we could provide for each group. We conducted an environmental scan of existing service charters and models of support, particularly in the US, Canada, and the UK, and used those findings in conjunction with the key areas of support that had emerged from our user research.

Postgraduate students would be the primary audience for the service charter, as they represented 77% of our systematic review consultations. For this audience, individual consultations serve as a learning opportunity for acquiring knowledge and skills that are subsequently assessed as part of an assignment or degree program. With this in mind, we scaled our support for postgraduate students to advising on all relevant stages of the systematic review process, but excluded such services as running and refining multiple searches, extracting results, preparing an EndNote library, and contributing to the methods section of a protocol or publication. For researchers, we saw our role as one of collaboration or partnership. Depending on the number of hours invested in the systematic review by the librarian, the charter specifies either acknowledgement of the library or librarian’s contributions, or co-authorship on the publication (see Appendix A).

Since implementing the Systematic Review Service Charter in January 2019, 88% of our systematic review support that year was at Tier 1 (Standard), either supporting postgraduate students or providing standard support for academics. This level of service has proven to be sufficient for the majority of clients, though we have also provided additional support at Tier 2 (8%) and Tier 3 (4%).

The service charter can be accessed on the library website or provided upfront to a client. One of the benefits of having this document is that it provides a basis for negotiating support, and serves as a safety net for managing difficult client relationships where a client may demand a disproportionate amount of their librarian’s time. There have been a number of other benefits to implementing the charter. It has enabled a more consistent approach to the library’s delivery of the service, articulating key aspects of our approach to both clients and librarians alike. We have been able to use the charter to promote the service at faculty meetings, and it has given us a framework to track demand over time. It also provides a mechanism for tweaking our support model and achieving consensus in the librarian team. Finally, it has led the way in our library for the development of further service charters to describe and promote other areas of support.

Systematic Review Toolkit

With the implementation of the systematic review service charter, we continued offering individual support with a more sustainable, consistent approach. We also continued to deliver our workshop program. However, there still remained a gap in providing online, self-service support. As our user research had revealed, there were a number of different units across the university providing support for systematic reviews, but no one place where this information was available.

We realised that there would be value to creating a resource that brought all these disparate sources together. Our user research had provided us with a journey map of the systematic review process, and a comprehensive list of resources that researchers might turn to for support. When deciding on the information architecture of the future resource, we were able to supplement the researchers’ list of stages with those valued by librarians, thus arriving at a truly co-created result. We also had a clear sense of the pain points throughout the process, and where they might occur. We could use our findings to address those issues proactively, by signposting them throughout the resource. When we mapped the pain points and resources back to the stages of the systematic review process, a structure for each section began to emerge organically:

Summary: provides a concise definition of each part of the process, particularly as researchers may be more familiar with some parts than others. This summary is authoritative and supported by literature.

Tips: librarians often provide advice based on generally accepted or conventional wisdom to researchers during a consultation. Here, we had an opportunity to (a) document those conventions; and (b) support our advice through evidence. This section also incorporates university-specific information on navigating resources and finding contacts.

Tools & Resources: links to external tools and resources, as well as a number of internal guides and PDF documents widely used in training.

Need Help?: connects users with the other parts of the university for help and support, such as the Learning Centre, for academic writing support, and the Sydney Informatics Hub, for statistical and data storage support. This section is also useful for librarians when asked about a stage of the systematic review process that is outside their area of expertise.

References: lists the sources used in developing the content, and provides a pathway for users to access relevant literature and methods papers.

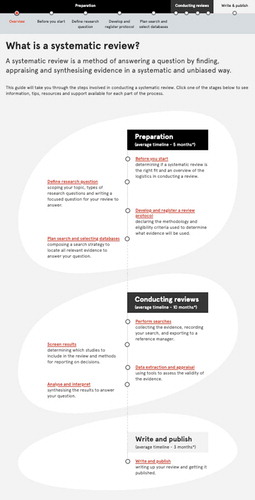

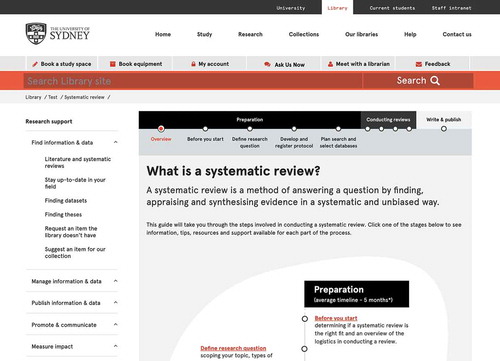

Following the principles of rapid prototyping we developed a low-fidelity prototype using SpringShare’s LibGuides platform. Ultimately we wanted the resource to be located on the main library website with its own distinctive look-and-feel, and not appear as another subject guide. To achieve this, we engaged an external UX consultancy company to help us develop the visual look and interface. They advised that we conducted additional user testing on the new interface, but this also provided us with an opportunity to test our newly developed content with users. With the consultant’s support, we developed a series of scenarios and questions to test content discoverability and navigation, text legibility, readability, and comprehension. The team identified two key user groups for the testing: postgraduate students from the biomedical sciences, and senior researchers who were teaching systematic review methods or supervising postgraduate students. The process of user testing resulted in a few additional changes. For example, we prototyped and tested an overarching three-part structure for the systematic review process: ‘Preparation’, ‘Conducting reviews’, and ‘Writing & publishing’. Now that there was a section titled ‘Preparation’, our users preferred ‘Before you start’ as the name of the first stage in the process. Our users also wanted an estimated timeframe for each section, so that they could plan their review accordingly. The final structure of the website is shown in .

Working with a low-fidelity prototype allowed us to quickly test and revise any changes, and prevented the team from becoming too wedded to any one element; every aspect of the site was up for discussion in line with user needs. We settled on the name Systematic Review Toolkit, as this resonated most with our users, and appeared to be the most accurate term for describing a ‘one-stop shop’ resource. Once we were satisfied that the toolkit had been thoroughly tested, the external team developed the final visual assets for us, and we populated their template with our content. We worked with our communications officer to promote the launch of the toolkit in June 2019, and were pleased to receive over 1,000 hits in its first two weeks on the library website. The final interface for the Systematic Review Toolkit is shown in .

Systematic Review Mentoring Program

Looking at our support from a service design thinking perspective allowed us to see that, although biomedical sciences remain the primary ecosystem for systematic reviews, a truly comprehensive service should strive to support a wider range of discipline areas. With this in mind, in 2019, we launched a staff development program with the view of increasing the number of librarians able to deliver systematic review support across multiple disciplines. This multifaceted program consisted of a number of steps and training opportunities, which are beyond the scope of this article. We opted for a mentoring format, where a group of novice (to systematic reviews) librarians were partnered with more experienced librarians in mentor-mentee pairs. The program opened with a comprehensive workshop that introduced the program and the basics of systematic review methods. Following the workshop, mentees attended research consultations delivered by their mentors and, when ready, ran consultations under supervision. The mentees also had access to a range of self-learning resources, and were encouraged to ask questions and to attend consultations by other program participants upon request. We concluded the program in 2020 with a wrap-up workshop that generated qualitative data about both the mentee and mentor experiences of the program. We are in the process of analysing the data and writing up the report, but the preliminary results of the program are positive, and the case for it to be repeated is strong. We are also considering how the learnings from this program might be applied to enhance the quality of research consultations more generally.

Future Directions: Systematic Review Working Group

Considering the ongoing development of our systematic review service, we can see that some elements require more maintenance than others. For example, the Systematic Review Toolkit has already generated a considerable amount of feedback that needs to be analysed and actioned. With a recent faculty restructure and the creation of a single Faculty of Medicine & Health at our university, we are excited by the opportunity to significantly scale up the systematic review workshop program. To keep pace with these developments, a dedicated working group was formed with a mandate to collect and action feedback, create and update documentation and training materials, and oversee the transition of our systematic review service to business as usual.

Conclusion

Two elements were critical on our journey in developing our systematic review service. Design thinking provided us with the tools to build empathy and conceptualise the process from our users’ perspective. Next, service design offered an approach to understanding the wider systematic review ecosystem, and where our library service intersected with other areas of support. The combination of the two approaches, through service design thinking, ultimately allowed us to transform our service. The development of new touchpoints in our service, including the charter and toolkit, and our ongoing work transitioning to business as usual, provides a meaningful opportunity to look back and reflect on the journey we have accomplished. We hope that this paper offers practical findings for librarians who support systematic reviews, but also provides inspiration for anyone looking to examine any library service from a new perspective. Ultimately, we hope that our methods and process are of most use to readers, as their application in another context will likely lead to new and exciting solutions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank everyone involved in the development of systematic review support at the University of Sydney. In particular, we would like to thank Joy Wearne, Heidi Laidler, Michelle Harrison, the systematic review champion group, and the Medicine & Health Cluster team.

Thank you to the University of Sydney Library for supporting costs associated with conference attendance and travel. We received no external funding for this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Edward J. Luca

Edward J. Luca is a library practitioner, researcher and MBA. He is currently Manager, Academic Services (Medicine & Health) at the University of Sydney Library. He previously worked as an Academic Liaison Librarian, and before that worked at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) Library. Edward writes and speaks on topics including design thinking, scholarly publishing and academic librarianship.

Yulia Ulyannikova

Dr Yulia Ulyannikova has been supporting Medicine and Health disciplines at the University of Sydney Library for the past five years. Her special interests are systematic review support and service improvement, with an emphasis on education and mentorship. She holds a Doctoral Degree in History from The University of Melbourne and a Master’s Degree in Information Management from RMIT.

References

- Aamodt, M., Huurdeman, H., & Strømme, H. (2019). Librarian co-authored systematic reviews are associated with lower risk of bias compared to systematic reviews with acknowledgement of librarians or no participation by librarians. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 14(4), 103–127.

- Bell, S. (2018). Design thinking + user experience= Better-designed libraries. Information Outlook, 22(4), 4–6.

- Brown, T. (2008). Design thinking. Harvard Business Review, 86(6), 1–10.

- Bryman, A. (2003). Quantity and quality in social research. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Bussell, H., Hagman, J., & Guder, C. S. (2017). Research needs and learning format preferences of graduate students at a large public university: An exploratory study. College and Research Libraries, 78(7), 978–998.

- Culén, A. L., & Gasparini, A. A. (2015). HCI and design thinking: Effects on innovation in the academic library. Proceedings of the international conference on interfaces and human computer interaction 2015 (pp. 3–10). Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain.

- Daigle, B. (2013). Getting to know you: discovering user behaviors and their implications for service design. Public Services Quarterly, 9(4), 326–332.

- Delaney, G., & Bates, J. (2018). How can the university library better meet the information needs of research students? Experiences from Ulster University. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 24(1), 63–89.

- Desmeules, R., Dorgan, M., & Campbell, S. (2016). Acknowledging librarians’ contributions to systematic review searching. Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association, 37(2), 44–52.

- Fong, B. L., Wang, M., White, K., & Tipton, R. (2016). Assessing and serving the workshop needs of graduate students. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(5), 569–580.

- Fox, R. (2015). Service empathy. OCLC Systems & Services, 31(2), 54–58.

- German, E. (2017). Information literacy and instruction: LibGuides for instruction: A service design point of view from an academic library. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 56(3), 162–167.

- Godin, S. (2006, September). Seth Godin: This is broken [ Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.ted.com/talks/seth_godin_this_is_broken

- Gore, G. C., & Jones, J. (2015). Systematic reviews and librarians: A primer for managers. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library & Information Practice & Research, 10(1), 1–16.

- Hanneke, R. (2018). The hidden benefits of helping students with systematic reviews. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 106(2), 244.

- Harbo, K., & Vibjerg Hansen, T. (2012). Getting to know library users’ needs - experimental ways to user-centred library innovation. Liber Quarterly: The Journal of European Research Libraries, 21(3/4), 367–385.

- Johnson, K. (2016). Understanding and embracing service design principles in creating effective library spaces and services. In The future of library space (Vol. 36, pp. 79–102). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Kautonen, H., & Nieminen, M. (2018). Conceptualising benefits of user-centred design for digital library services. Liber Quarterly: The Journal of European Research Libraries, 28(1), 1–34.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: PrenticeHall.

- Lasserson, T. J., Thomas, J., & Higgins, J. P. T. (2019). Starting a review. In J. P. T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, & V. A. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. London, UK: Cochrane. Retrieved from http://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Luca, E., & Narayan, B. (2016). Signage by design: A design-thinking approach to library user experience. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 1, 5.

- Mahan, J. D., & Stein, D. S. (2014). Teaching adults - Best practices that leverage the emerging understanding of the neurobiology of learning. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 44(6), 141–149.

- Marquez, J., & Downey, A. (2015). Service design: An introduction to a holistic assessment methodology of library services. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 1, 2.

- McKeown, S., & Ross-White, A. (2019). Building capacity for librarian support and addressing collaboration challenges by formalizing library systematic review services. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 107(3), 411–419.

- McLaughlin, J. E. (2015). Focus on user experience: Moving from a library-centric point of view. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 20(1/2), 33–60.

- Meier, J. J., & Miller, R. K. (2016). Turning the revolution into an evolution. College & Research Libraries News, 77(6), 283–286.

- Murphy, S. A., & Boden, C. (2015). Benchmarking participation of Canadian university health sciences librarians in systematic reviews. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 103(2), 73–78.

- Nicholson, J., McCrillis, A., & Williams, J. D. (2017). Collaboration challenges in systematic reviews: A survey of health sciences librarians. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 105(4), 385–393.

- Peacemaker, B., & Roseberry, M. (2017). Creating a sustainable graduate student workshop series. Reference Services Review, 45(4), 562–574.

- Ross-White, A. (2016). Librarian involvement in systematic reviews at Queen’s University: An environmental scan. Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association, 37(2), 39–43.

- Smith, S. A., Lubcke, A., Alexander, D., Thompson, K., Ballard, C., & Glasgow, F. (2019). Listening and learning: Myths and misperceptions about postgraduate students and library support. Reference Services Review, 47(4), 594–608.

- Spencer, A. J., & Eldredge, J. D. (2018). Roles for librarians in systematic reviews: A scoping review. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 106(1), 46–56.

- Tempelman-Kluit, N., & Pearce, A. (2014). Invoking the user from data to design. College and Research Libraries, 75(5), 615–640.

- Toews, L. (2019). Benchmarking veterinary librarians’ participation in systematic reviews and scoping reviews. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 107(4), 499–507.

- Wilson, C. (2011). Method 3 of 100: Freelisting. Retrieved from https://dux.typepad.com/dux/2011/01/this-is-the-third-in-a-series-of-100-short-articles-about-ux-design-and-evaluation-methods-todays-method-is-called-freeli.htm

- Wilson, C. (2013). Using brainwriting for rapid idea generation. Retrieved from https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2013/12/using-brainwriting-for-rapid-idea-generation/

- Wissinger, C. L. (2018). Is there a place for undergraduate and graduate students in the systematic review process? Journal of the Medical Library Association, 106(2), 248.