ABSTRACT

The De La Salle University (DLSU) Libraries organised the first Human Library in the Philippines in August 2014. The initial target audience were undergraduate and graduate students of the University. In 2016, the Integrated School Libraries organised Human Library sessions for grade school, junior high school, and senior high school students. The activity allowed them to engage with human books actively, facilitating an innovative learning experience. This paper describes the Human Library program of the DLSU Integrated School Libraries. The program aims to promote respectful dialogue between human books and students, foster the culture of diversity and difference, and reduce prejudice and discrimination against people with different social and cultural backgrounds. The program has been integrated with the school curriculum, thus allowing students to have the opportunity to dialogue with human books from different backgrounds, such as people with a tattoo, members of LGBTQ community, people with mental health issues, people with bipolar disorder, and people with eating disorders among others. Through this learning experience, students are expected to appreciate diversity and are more open-minded at an early age, be more accepting and kinder to others, empathetic, and respectful.

Introduction

The idea of a modern library is not just limited to collections of reference materials, books that support school curriculum, general books not specific to any subject area, periodicals, newspaper, audiovisual materials, government publications, and electronic and online journals. These resources enable the library to serve its role in the community to provide information and support the success of the education of the communities they serve. Still, libraries are also service organisations and strive to instil social awareness and community involvement and serve other purposes like socioeconomic and political changes because they organise and make available the written history, culture, and knowledge of the human race (Patel, Citation2011). Implementing a Human Library program is just one of the ways that libraries can attain this purpose. This program can fulfil the educational role of the library to promote respectful dialogue and develop an individual’s open outlook without any discrimination, stereotypes, and prejudice.

The Human Library in the Philippines

The Human Library was conceptualised in Copenhagen in 2000 by Ronni Abergel, his brother Danny, and colleagues Asma Mouna and Christoffer Erichsen (The Human Library Organization, Citation2019). This project is a global innovative, hands-on learning platform where real people are on loan to readers. It is a learning platform where personal dialogues challenge stigma and stereotypes and create a safe space for dialogue. The concept of the project employs the traditional role of a regular library where users can request a specific book of their choice. In the human library concept, members of the minority volunteer and play the role of ‘human book’ and are ‘borrowed’ for conversations. Throughout the session, they share their personal histories and experiences. ‘Readers’, in turn, asks questions that the human book can answer provided that the living books are comfortable in answering it and does not offend him/her in any way (Groyecka et al., Citation2019). There are two types of Human Libraries, open and dedicated ones. A dedicated library is organised for members of a specific group like students, while sessions done in public libraries is free for everybody who would like to participate in it (Abergel, Citation2005).

Today, the Human Library hosts events at libraries, festivals, conferences, public schools, high schools, higher learning institutions for the public and private sectors. The Human Library Organisation has rich experience of 19 years. The organisers of the Human Library are scattered in 80 countries, six continents. In Asia, Human Library events are already being organised in Korea, Thailand, China, Hong Kong, India, and Malaysia. The first-ever Human Library event organised in the Philippines was launched by the De La Salle University (DLSU) Libraries on 14 August 2014 (De La Salle University Libraries, Citation2014).

The idea of organising the event started in January 2014 when DLSU Libraries received an invitation from the Rajamangala University of Technology Isan in Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand, to attend the 2014 International Forum on Human Library Development for ASEAN++. The forum, which was attended by the Director of Libraries, helped provide a better understanding of the concept. It also offered ideas on how the concept can be adopted in the DLSU Libraries.

In August 2019, the DLSU Libraries celebrated the fifth-year anniversary of the program. As part of the DLSU Libraries’ aim to cultivate an image of a sensible and sensitive community of Lasallians towards social issues, this activity is an alternative way of learning, which may promote dialogue, reduce prejudice, and encourage understanding of people from different walks of life.

During the launching year in 2014, 10 human books representing different types of prejudices served as living books and were tagged as (1) The Unbearable Lightness of Being Me by Maria Vanessa Medina (lightweight); (2) Pride vs. Prejudice: Making the World More LGBT-Friendly by Eric Julian Manalastas (Gay); (3) Proud Tibo, Proud Nanay by Ma Luisa Toribio (Lesbian); (4) The Tattoo Artist by Alfred K. Guevara (Tattooed); (5) Heavily Fluffy But Happy by Adolf Rey Duquez (Obese); (6) Mga Karanasan ng Isang Bading by Ron de Vera (Gay); (7) Geographies of Gender by Mylene De Guzman (Lesbian); (8) Let Me Be by Ruth Mae Nichole Taduran (Teenage Mom); (9) Babaylan by Gabriel ‘Heart’ Diño (Transgender); and (10) Lola Monching by Ramon O. Ramos (Tattoed).

The DLSU Libraries held Human Library sessions regularly every three months, every term. Human books are only available on specific set dates, usually one full day for the Integrated School Libraries in the Laguna Campus and half-day at the Learning Commons-Manila Campus. The sessions start with an opening ceremony, followed by orientations for human books and readers. During the orientation, organisers discuss the expectations of readers and human books. Human books are expected to be truthful in sharing their stories. The focus of the conversations and questions should be on the identified prejudice, stereotype, or topic. Books and readers are always expected to keep decorum. Human books must wear the Human Library t-shirt provided by the organisers during the session.

Sessions are usually informal and come in the form of conversation or dialogue between the living book and the reader. The DLSU Libraries follow the ‘group reading’ type of session where three to four people get to ‘read’ one book simultaneously. Living books are individually stationed inside discussion rooms, and the readers get to choose the book they would want to ‘read’ by going inside the room of the preferred human book. For the sessions held in the Integrated School, human books are stationed inside the classrooms.

Since 2014, in the Manila Campus, the DLSU Libraries organised nine sessions wherein 84 human books were invited and willingly volunteered to share their personal stories. A total of 1,712 readers, consisting of college students, graduate students, teachers, school administrators, and non-DLSU members from different schools participated. A total of 55 unique prejudices, stereotypes, and discrimination topics were covered. The average numbers of readers per reading session are 4–6, and the average duration of one reading session lasts for 45 minutes. The program is supported by university partners, which include the DLSU College of Law, DLSU Archers Network (student organisation), DLSU Green Giant FM Radio, Chinese Corner, American Corner-Manila, and Catholic Educational Association of the Philippines (CEAP).

In January 2017, the Philippine Association of Academic and Research Librarians (PAARL), Inc. conferred its ‘Outstanding Library Program of the Year Award’ to the De La Salle University Libraries’ Human Library Program. The award is given to an academic or research library in recognition of its outstanding library program that contributes to Philippine academic librarianship and library development in the Philippines. DLSU’s Human Library was commended as ‘an innovative ongoing outreach program’ for its strong impact on the library community, innovation, and sustainability that it may be replicated in other library communities or institutions.

To promote the Human Library, before the scheduled sessions, announcements were published in some major daily newspapers in the Philippines. There were also written news and feature articles about the Human Library in DLSU student publications and coverage in the university FM radio station, Green Giant.

Research Objectives

This paper describes the Human Library program of the DLSU Integrated School Libraries. This paper also examines the experiences of human books and readers based on completed evaluation forms. It further analyses the personal reflections of the students after attending the sessions to understand the impact of the Human Library in their lives as learners. This paper aims to recognise the challenges and opportunities of the Human Library in promoting diversity, inclusion, and equity in the school environment.

Research Problems

What are the personal experiences of human books and readers during human library sessions?

What are the challenges and opportunities of the Human Library in promoting diversity, inclusion, and equity in the school environment?

Literature Review

There are Human Library research studies conducted worldwide since its inception in 2000. Most of the studies explore the effectiveness of the Human Library project on the full effect of decreasing prejudice and stereotypes among the readers of the living books. Dobreski and Huang (Citation2016), for instance, cited the eight benefits from Human Library sessions, namely: helping others, teaching, making connections, learning, self-expression, reflection, therapeutic benefits, and personal enjoyment. Inkster et al. (Citation2016), in their study of the Human Library in Bolton, found the activity successful in its aim to challenge prejudice in healthcare, for hearing stories of discrimination make them more understanding of patient’s natural fear which could be heightened by past personal experience of prejudice.

Groyecka et al. (Citation2019) conducted a pre-post intervention study that examined the effectiveness of the Human Library in Wroclaw, Poland, in reducing the social stigma towards particular prejudices – Roma, Muslims, dark-skinned and transgender people, as well as in decreasing homonegativity. In this paper, they also measured whether participation in the Human Library changes individual attitudes towards diverse workgroups. Their findings show that the Human Library decreased social prejudice towards Muslims. They likewise observed an increase in positive affective attitude towards working in diversified groups.

A study by Orosz, Bánki, Bőthe, Tóth-Király, and Tropp (Citation2016) researched whether Hungarian teenagers taking part in the Human Library intervention changed their attitudes towards Roma and LGBT people. The study revealed a significant difference in perceived prejudice towards both groups. The event was dedicated solely to high school students and was not open to the general public. The groups towards which the shift in attitudes was tested are somewhat limited, considering the problems with discrimination that the many minorities in Eastern Europe struggle with.

In the Philippines, several studies were done by librarians from DLSU. Yap and Labangon (Citation2015) discussed in their paper in their paper that the human library proved to be an alternative way of learning for both the reader and the human book. The sessions create a liberating moment for both parties as they share their experiences. It empowers people to accept the differences among individuals.

Yap, Labangon, and Cajes (Citation2017) present the role of libraries in promoting dialogue to reduce discrimination, share how libraries document human library sessions as a form of oral history, and provide information on the effect of human library sessions to readers. Their paper documented the DLSU human library program as an alternative source of information that promotes cultural diversity to improve many facets of literacies, which include media and information literacy.

The study reported in this paper describes the Human Library program of the DLSU Integrated School Libraries, based on the research questions about the experience of the participants themselves, and their perceptions of any benefits to them.

Research Design

This paper is a descriptive study where data were collected before and after eight Human Library sessions at the Integrated School in DLSU Laguna Campus. The authors analysed the students’ learning experiences after attending the Human Library session based on the completed evaluation forms (see and 2). A total of 973 readers and 26 human books participated in the evaluation. Data were collected from SY2016-2017 to SY2018-2019. The authors used Microsoft Excel to process the data. NVivo was also used to analyse the sentiments of students’ qualitative comments in response to the open questions.

Research Findings

The Human Library and the DLSU Integrated School

The Human Library at DLSU Integrated School aims to challenge stereotypes, stigma, prejudice, and discrimination that grade and high school students have formed about a person (subject) and that in the end, these are reduced, if not eradicated. Likewise, it aims to foster an understanding of people of what they are or what they do. While the Human Library’s objectives can be flexible in responding to localised contexts, DLSU opted to stick to its original objectives. However, in the future, the organisers may consider realigning the concept to support the programs and services of the University. The Integrated School Libraries at the DLSU Laguna Campus hosted the seventh session of the Human Library on 3 March 2017, from 8:00 am-11:00 am. This session covered human books on the following subjects: Martial Law victim, LGBT representative, Catholic layperson, tattoo artist, person with ADHD, professional squatter, jobless person, person with tattoo, human rights activist, and reformed drug addict.

This specific session targeted Grade 10 and Grade 11 students. What sets this session apart is that it was held in the classrooms with 25 or more readers per human book. Separate sessions were given to each grade level. The teacher advisers introduced the human books to the class. At the end of each session, the students should be able to: (1) demonstrate an understanding of people’s diverse socio-cultural background; (2) describe the different prejudices, stereotypes, and discriminations faced by marginalised and underserved groups of the society; and (3) recognise various strategies to break stereotypes, eliminate prejudice, and stop discrimination in the school.

shows that since 2017 the Integrated School Libraries organised eight sessions wherein 42 human books were invited and willingly volunteered to share their personal stories. A total of 2,275 readers consisting of Grade 5, 6, 10, and senior high school students, teachers, school administrators, and non-DLSU members from different schools participated.

Table 1. Summary of Human Library Sessions.

The number of sessions, human books, and readers increased yearly. For SY2016-2017, there was one session recorded with seven human books and 533 readers composed of grade 10 and 11 students. In SY2017-2018, there were four sessions with 21 human books and 744 readers consisting of grades 5–6 and 10–12 students. In SY2018-2019, there were eight sessions with 14 human books and 998 readers composed of grades 6 and 10–12 students. As shown in –, the human book's topic varied depending on the audience or readers per grade level. Among the topics covered were victims of martial law, human rights activist (enforced disappearances), religious person, professional squatter (informal settlers), ex-drug addict, people with tattoos, person with bipolar disorder, LGBTQ person, unemployed person, and tattoo artist. In SY2017-2018 Human Library sessions, topics included non-sensitive topics intended for the grade 5–6 readers like the least favourite subject in school focusing on social science, art, mathematics, Catholic faith and Filipino. The focus of discussions with the grade 10–12 readers was based on person with psoriasis, person with bipolar disorder, a young businessperson, son of a teenage single mom, a cancer patient, and a Muslim person.

Table 2. List of Human Books, AY2016-2017.

Table 3. List of Human Books, AY2017-2018.

Table 4. List of Human Books, AY2018-2019.

Table 5. Human Books’ Experience

In SY2018-2019, for grade 6 readers, the topics discussed were soldier, police, and religious representatives. In contrast, topics of human books for grades 10–12 readers are millionaire (since birth or rags-to-riches), martial law, bipolar, adopted child, working student, ex-convict, artist, broken family, overweight/obese, disabilities, mental disorders, gender preference, person with HIV and women in male-dominated professions.

Human Books and Lasallian Students Experience

Organisers distributed evaluation forms to readers and human books after each session from 2016 to 2019 (see Annexe 1 and 2). The instruments used a combination of closed and open-ended questions. The questions included in the tools are statements about the Human Library session, their previous and future participation of readers and human books, challenging experiences as a human book, and the most memorable experience of the readers.

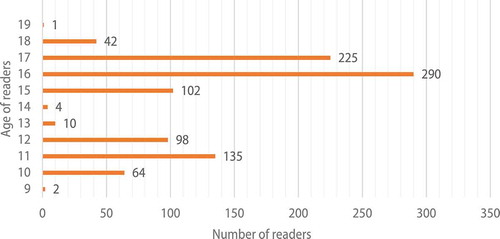

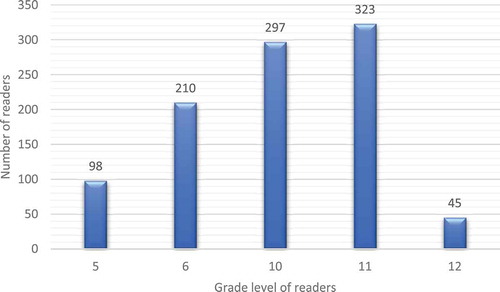

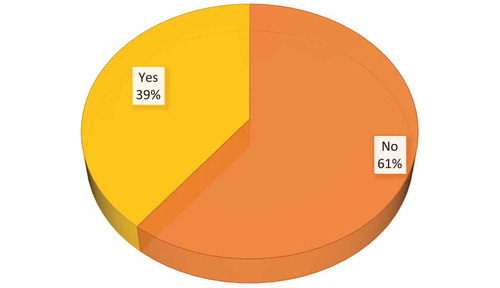

shows the distribution of human readers by age. The majority of the readers are 16 years old. The age of human readers ranges from 9 to 19, with most readers in the age group 15–17. The highest number of readers in the sessions were composed of grades 10–11 students. Thirty-nine per cent of the participants have already participated in the Human Library events before. Most of them are grade 11 (); 61% of the respondents have not participated in other human library events previously as shown in .

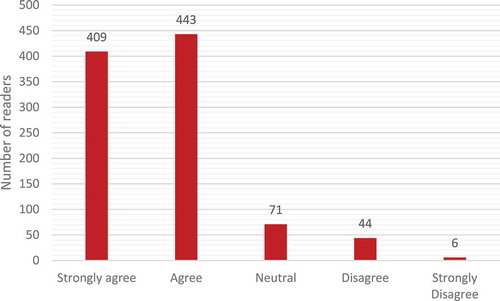

When talking about the readers’ experience of the Human Library sessions, shows that in general, many respondents have a positive attitude towards diversity of prejudices stereotypes, and topics that are available to them. The organisers chose the topics of prejudices and stereotypes based on the survey conducted to determine students’ interests.

In terms of the helpfulness of the organisers, many of the respondents showed a favourable agreement to the statement in . The librarians and support staff at the Laguna Campus are the main organisers of the Human Library sessions, in close coordination with the school’s subject coordinators and teachers.

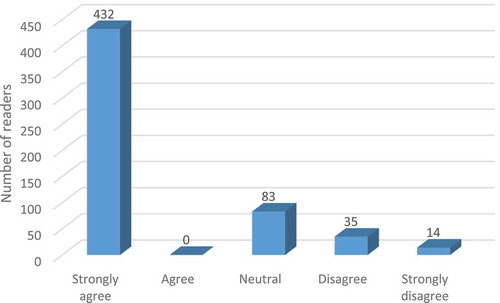

shows that most of the respondents strongly agreed that the time allocated for the reading session was sufficient, while 35 respondents disagreed, and 14 strongly disagree with this statement. The entire reading session is about 45 minutes. In the Manila Campus, each reader can read a book for 15 minutes, so in one Human Library session, they can read three books. In the Integrated School sessions, students are only allowed to pick one human book to read. Reservations are made a day before the actual session.

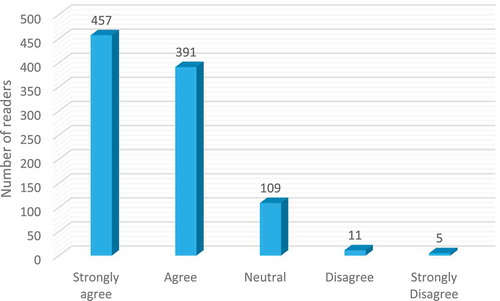

When it comes to the impact of the sessions, shows that almost 50% of the total respondents strongly agree with the statement, ‘the reading session helped my prejudice on the topic’. In comparison, 10% of them are neutral or have no opinion. Only 16 students showed contrary agreement with the statement. The data show that there is a positive impact on the prejudices of grade school and high school students.

In terms of the overall rating of the sessions conducted, 64% of the respondents gave an excellent rating of their Human Library experience, as illustrated in . When the respondents were asked if they still have other prejudices that they want the organisers to consider in the next Human Library sessions, 75% of them responded no, I do not have any.

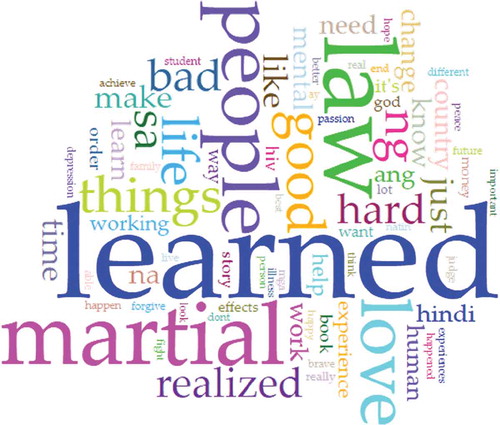

Using the web-based Voyant Tools to generate a word cloud of the key terms found in the reflection of the students, we were able to determine the most-commonly occurring words and themes in their comments. shows that learned, martial, people, and law are the most-commonly occurring themes.

Using the Nvivo software, shows that the difference between negative and positive sentiments in students’ comments is not significantly high. However, positive views still are higher than those negative ones.

When it comes to the Human Books’ own experience, they all agreed on having a pleasant experience volunteering as a human book (see ). Note that only 26 human books are in this study. The Human Books said that the readers agreed that they actively participated during the reading session. The orientation provided by the organisers on the role of the human book was beneficial. The organisers/librarians were very helpful. The duration of the reading hours was sufficient and that the reading session provided them with the opportunity to promote understanding between people of opposing views. Notice that several human books rated the statements ‘the readers actively participated during the reading session’ and ‘the duration of the reading hours is sufficient’ negatively.

The majority of Human Books agreed on having the willingness to participate again as a human book in the future. They likewise would recommend to their friends or others to participate in a human library event either as a reader or a living book, as shown in and , respectively.

Figure 12. Recommend to your friend/others participation in a human library event either is a ‘reader’ or a living book.

In the evaluation form, the human books wrote the following comments.

Good to be more participative

Continue to promote HL

Awesome project

They also shared some areas for improvement to make it more effective. They suggested giving ample time for the students to read them and listen to their stories, especially when readers are actively participating in the conversation. They hope to receive background information about human readers before the reading session so they could prepare to make the dialogue appropriate for their age level. Some of the human books had few readers. They suggested that the library should find ways to increase their readers.

When the human books shared the most challenging part of being a human book, they expressed the difficulty of sharing their personal experiences and relating it to a younger audience. They feared that the readers might ask sensitive questions or have unpleasant comments. Keeping the readers’ interest, student engagement, and convincing the students proved to be another challenge as well as ensuring that readers understand the topics and concepts. They also experience feeling the pain of what they have been through when they are sharing past experiences. Another difficulty was classroom management and ensuring active listening for the big audience, especially for human books, with no experience dealing with the younger student audiences. Human books also had difficulty eliciting questions from the readers because they are shy to ask questions. They also perceived that once the students ask questions, the time allotted was not enough to answer all the questions.

Issues and Challenges

There are specific issues and challenges that the organisers faced during the planning and implementation of the program. For every session, they have encountered different problems. One of their foremost difficulties was the limited topic of prejudices that are appropriate for younger readers. In the planning stage, the organisers did conduct surveys to check the interest of the students. The initial survey conducted showed that the students, at their age, already have prejudices on sensitive topics such as strippers, prostitutes, mistresses, drug addicts, and battered wives. Another challenge during the implementation stage is the need to strategise and enable the students to read more than one human book as well as to get them to participate and ask questions during the sessions.

When it comes to looking for human books, since the schedule must fit the program partners’ availability, the organisers have difficulties in inviting possible human books due to changes and conflict in the schedule. The changes in the schedule lead to the shorter lead time for leg work and preparations. Another challenge for the organisers is the limited time given by the program partners for the sessions because of the possibility of class disruption. The location of the school also proves to be a challenge to potential human books.

Conclusion

This paper focuses on four aspects: describe the human library program of the DLSU Integrated School Libraries, examine the experiences of human books and readers during human library sessions, analyse the personal reflections of the human books and students after attending the Human Library sessions, and recognise the challenges and opportunities of the Human Library in promoting diversity, inclusion, and equity in the school environment.

The program helped in drawing awareness and promoting respectful dialogue, diversity, and empathy among grade and high school students as it resulted in reducing prejudices among the student readers after the session. The purpose of Human Library sessions was achieved, as Human Books related having had a wonderful experience volunteering as a human book. The readers have actively participated during the reading session and that the reading session provided them with the opportunity to promote understanding between people of opposing views.

The program will continue in the following years, but changes will be made based on the results of this study. The number of readers per human book will be less. The organisers will explore the possibility of offering human library sessions to lower grade levels (Grades 3–4, Grade 7–8) to focus on building a culture of diversity, openness, and empathy among grade school and high school students.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Candy May N. Schijf

Candy May N. Schijf is a graduate of Saint Louis University in Baguio City, Philippines. She is currently affiliated with the DLSU Libraries. Her research interest includes collection management, program assessment, and information literacy.

Julieta F. Olivar

Julieta F. Olivar Olivar took her Master's degree in Library Science at Manuel L. Quezon University in 2008. She has been with DLSU for the past 16 years. Guided by her zest for life, sense of wonderment and love for children, she is currently the Preschool Librarian in DLSU Integrated School, Laguna Campus.

Jorge B. Bundalian

Jorge B. Bundalian finished his Master's degree in Library and Information Studies at the University of the Philippines in 2016. He is employed in DLSU since 1994 and presently working as a Reader's Services Librarian of DLSU - Laguna Campus College Library.

Marian Ramos-Eclevia

Marian Ramos-Eclevia works at the DLSU Libraries as Assistant Director for Operations. She holds a bachelor's and master's degree in library and information science from the UP School of Library and Information Studies. She has more than a decade of experience in the field of reference and information services in an academic library setting. Her research interests focus on use and user studies, digital reference services, collection analysis, bibliometrics, and leadership in LIS education.

References

- Abergel, R. (2005). Don‘t judge a book by its cover!: The living library organiser‘s guide. Budapest: Council of Europe.

- De La Salle University Libraries. (2014). The DLSU Libraries launched the first human library in the country. Retrieved from http://librarynewsette.lasalle.ph/2014/08/launch-first-human-library.html

- Dobreski, B., & Huang, Y. (2016). The joy of being a book: Benefits of participation in the human library. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 53(1), 1–3.

- Groyecka, A., Witkowska, M., Wrobel, M., Klamut, O., & Skrodzka, M. (2019). Challenge your stereotypes! Human library and its impact on Prejudice in Poland. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 29, 311–322. doi:10.1002/casp.2402

- Inkster, C., St. Jean, L., Elliott, P. & Leach, M. (2016). Challenging prejudice in healthcare: The human library. Retrieved from https://www.nwpgmd.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/The%20Human%20Library%20for%20Healthcare%20Learners%20%282%29.pdf

- Orosz, G., Bánki, E., Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., & Tropp, L. R. (2016). Don’t judge a living book by its cover: Effectiveness of the living library intervention in reducing prejudice toward Roma and LGBT people. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 46(9), 510–517.

- Patel, U. (2011). Social awareness and community involvement through library services. Paper presented at the Dept. of Library & Inf. Sc. & Alumni Association DLIS V V Nagar, Gujarat, India. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292274979_SOCIAL_AWARENESS_AND_COMMUNITY_INVOLVEMENT_THROUGH_LIBRARY_SERVICES

- The Human Library Organization (2019, July 23). The human library. Retrieved from https://humanlibrary.org/about

- Yap, J. M., & Labangon, D. L. G. (2015). Embedding corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities in an academic library: Highlights on the social aspects of the human library. PAARL Research Journal, 2(1), 14–24.

- Yap, J. M., Labangon, D. L. G., & Cajes, M. L. (2017). Defining, understanding and promoting cultural diversity through the human library program. Pakistan Journal of Information Management and Libraries, 19, 1–12.

Appendix 1.

Evaluation for Readers

Name (optional): __________________________________________________________________

Age: _______________________ Sex: ☐ Male ☐ Female

Academic Status:

☐ Junior High student ☐ Master’s degree holder

☐ Senior High student ☐ PhD degree holder

☐ Undergraduate student ☐ Out-of-school youth

☐ Bachelor’s degree holder ☐ Others, please specify:____________________________

If student, year level: ____________________________________________________________

If employed, occupation: _________________________________________________________

1. How did you learn about the human library event?

☐ Email/Helpdesk announcement ☐ Radio announcement

☐ Friend/Referral ☐ Social Media

☐ Newspaper ☐ Television

☐ Posters ☐ Others, please specify:__________________

2. Have you ever participated in other human/living library events before?

☐ Yes ☐ No

3. Which book/s did you “read” today? Please write down the “titles”.

a. _________________________________________________________________________

b. _________________________________________________________________________

c. _________________________________________________________________________

d. _________________________________________________________________________

e. _________________________________________________________________________

4. The selection of human books made available to the “readers” is sufficient.

☐ Strongly agree ☐ Disagree

☐ Agree ☐ Strongly disagree

☐ No opinion

5. The organizers/librarians were very helpful.

☐ Strongly agree ☐ Disagree

☐ Agree ☐ Strongly disagree

☐ No opinion

6. The duration of the “reading” hours is sufficient

☐ Strongly agree ☐ Disagree

☐ Agree ☐ Strongly disagree

☐ No opinion

7. The “reading” session helped reduced my prejudice on the topic.

☐ Strongly agree ☐ Disagree

☐ Agree ☐ Strongly disagree

☐ No opinion

8. My overall rating of the Human Library:

☐ Excellent ☐ Fair

☐ Very Good ☐ Poor

☐ Good

9. What was the most memorable experience you had while “reading” the book/s?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________

10. Would you be willing to participate again as a “reader” in the future?

☐ Yes ☐ No

11. Would you recommend to your friend/others participation in a human library event either as a “reader” or a living book?

☐ Yes ☐ No

12. Would you have other prejudices that you would want the DLSU Libraries to consider in its next

Human Library session?

☐ Yes, I have ☐ No, I don’t have

13. If yes, please list down your prejudice/s.

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________

14. Please list down other comments/suggestions you may have to help us improve the Human Library sessions/programs?

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________

Thank you for taking the time to complete this form!

Appendix 2.

Evaluation for Human Books

Name (optional): ________________________________________________________________

Age: ________ Sex: ☐ Male ☐ Female

Academic Status:

☐ Junior High student ☐ Master’s degree holder

☐ Senior High student ☐ PhD degree holder

☐ Undergraduate student ☐ Out-of-school youth

☐ Bachelor’s degree holder ☐ Others, please specify:________________________

1. Were you invited as a human book to represent an organization?

☐ Yes ☐ No

2. If yes, please write down the name of your organization? _______________________________

3. How many readers did you have during the Human Library session?

☐ 1 to 3 ☐ 9 to 12

☐ 4 to 6 ☐ 13 or more

☐ 7 to 9

4. I had a wonderful experience volunteering as a human book.

☐ Strongly agree ☐ Disagree

☐ Agree ☐ Strongly disagree

☐ No opinion

5. The “readers” actively participated during the “reading” session.

☐ Strongly agree ☐ Disagree

☐ Agree ☐ Strongly disagree

☐ No opinion

6. The orientation provided by the organizers on my role as a human book was very helpful.

☐ Strongly agree ☐ Disagree

☐ Agree ☐ Strongly disagree

☐ No opinion

7. The organizers/librarians were very helpful.

☐ Strongly agree ☐ Disagree

☐ Agree ☐ Strongly disagree

☐ No opinion

8. The duration of the “reading” hours is sufficient.

☐ Strongly agree ☐ Disagree

☐ Agree ☐ Strongly disagree

☐ No opinion

9. The “reading” session provided me with the opportunity to promote understanding between people of opposing views.

☐ Strongly agree ☐ Disagree

☐ Agree ☐ Strongly disagree

☐ No opinion

10. What do you think was the most challenging part of being a human book?

__________________________________________________________________________

11. Would you be willing to participate again as a human book in the future?

☐ Yes ☐ No

12. Would you recommend to your friend/others participation in a human library event either as a “reader” or a living book?

☐ Yes ☐ No

13. Please list down other comments/suggestions you may have to help us improve the Human Library sessions/programs?

__________________________________________________________________________

Thank you for taking the time to complete this form!