ABSTRACT

Mis/disinformation has in recent political and health climates become increasingly spread through social media and the internet, drawing increased discussion on the role libraries play in countering and combating the spread of mis/disinformation. This study investigated the impact and management of mis/disinformation at university libraries in Australia through a survey of 88 library staff and interviews with 17 managers. Library staff believe they have a role in teaching skills such as critical thinking and evaluation, advocating in this space and maintaining credible, balanced and inclusive collections. Although combating mis/disinformation is a strategic priority for libraries, it is often not a priority for the institutions themselves, leading to barriers for staff who would like to devote more time and resources to teaching information literacy skills and assessing the credibility and accuracy of collections. While complaints about collection content are low and library managers’ view is that libraries should not censor materials, there is an increasing priority in Australia to address historical inaccuracies in content and build and maintain collections that are inclusive and culturally safe. Library staff in Australia would like support from national library bodies through training and resources and playing an advocacy role in national discussions around mis/disinformation.

Introduction

Fake news or mis/disinformation is not a new phenomena but has recently become a focus of concern due to the ease with which it can be spread through the internet and social media and the spread of mis/disinformation in recent political, social and health contexts such as elections and COVID-19. Fake news is generally defined in the literature as the spreading of rumours or false information that is biased and intended to be misleading with organisations such as the world economic forum describing it as a major threat to our society (Burkhardt, Citation2017; Lim, Citation2020; Revez & Corujo, Citation2021). Misinformation and disinformation are both defined as the spreading of false information with the main difference between the two being intent, with people deliberately or knowingly spreading disinformation (Chandler & Munday, Citation2020). Many librarians have seen this proliferation of mis/disinformation as an opportunity for libraries to combat mis/disinformation through information literacy and teaching of skills such as critical thinking and evaluating information and as an opportunity to show libraries’ expertise and value in this space (Batchelor, Citation2017; De Paor & Heravi, Citation2020; Eva & Shea, Citation2018). Libraries are also known as places where information can be accessed that is reliable, unbiased, and verifiable, (De Paor & Heravi, Citation2020) however within the higher education context the responsibility for collection development is increasingly being outsourced with reliance on subscription packages and vendor acquisitions, limiting direct oversight from librarians of quality control for collections.

Although there is literature on libraries combating fake news through information literacy, advocacy and library guides, there is limited literature around how mis/disinformation is managed in university library collections, including managing complaints, historical information and collection management policies. There is also limited research conducted specifically on the Australian context and whether mis/disinformation has any impact on academic libraries and how it is managed with university libraries, therefore this study is the first to explore the specific experiences collectively in Australian university libraries. This study also provides valuable insights around mis/disinformation and collections and contributes to the limited research in this area. This research study aims to explore the impact and management of mis/disinformation at university libraries in Australia. The objectives of the research are to explore the impacts of mis/disinformation on Australian university libraries, what role Australian university libraries play in combating mis/disinformation, what policies and procedures are in place to manage mis/disinformation in collections, investigate what resources and information literacy skills are being developed and taught and establish what are the barriers to and support needed to manage mis/disinformation at university libraries in Australia.

Literature Review

Literature on mis/disinformation in libraries tends to focus on information literacy with little published around mis/disinformation and collection management. Much of the literature focuses on information literacy, media literacy, fake news, libguides evaluating information and advocacy (De Paor & Heravi, Citation2020; Revez & Corujo, Citation2021). Mis/disinformation within academic libraries has been mainly addressed through information literacy lessons delivered to students, either through one-shot classes or workshops or content embedded into unit content (Auberry, Citation2018; Clough & Closier, Citation2018; Wade & Hornick, Citation2018), with one study showcasing a workshop with staff that sought to combat misinformation on minority groups (Krutkowski et al., Citation2020). The content delivered in these classes was often created in response to the proliferation of fake news that arose during the US elections and the COVID-19 pandemic (Addy, Citation2020; Albert et al., Citation2020) and aimed to increase students’ ability to determine and evaluate what is correct information and fake news (Auberry, Citation2018).

Many lessons on information literacy that address misinformation/disinformation draw inspiration from the ‘information as process’ frame from the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Framework (Musgrove et al., Citation2018). As such, they place a strong emphasis on checklist evaluative practices such as CRAAP (currency, relevance, authority, accuracy and purpose) and RADAR (rationale, authority, date, accuracy and relevance) (De Paor & Heravi, Citation2020; Neely-Sardon & Tignor, Citation2018). There is also a shift towards more problem-based learning rather than checklist-based evaluation (Auberry, Citation2018; Evanson & Sponsel, Citation2019). This problem-based learning has an emphasis on lateral reading and a move towards the psychology around deciphering fake news and approaches used in cognitive research and education technology (Faix & Fyn, Citation2020). Although there are case studies showcasing how libraries are combating mis/disinformation especially around information literacy and guides, there is little research or evidence showing if these strategies are having an impact (Revez & Corujo, Citation2021). Sullivan (Citation2019) advocates for LIS professionals to join with the wider research community to provide a multi-pronged approach to tackling fake news.

LibGuides are another resource that university libraries use to provide information on how to critically evaluate information and offer strategies such as the checklist evaluative practices (Neely-Sardon & Tignor, Citation2018). A recent study looked at how academic libraries help to combat misinformation around COVID-19 which included library guides with credible information, providing access to articles on COVID-19 on websites as well as listing books that are fake news on Library guides in order to stem fake information in collections (Bangani, Citation2021). Lim (Citation2020) conducted a content analysis study on library guides related to fake news and found that most guides advocated for a checklist approach to evaluating information and combating fake news.

Several researchers debunk the assumption digital natives who have always had access to the internet and technology will inherently have good information evaluation skills when it comes to critically analysing online content. Research shows that while digital natives often portray confidence in their ability to gauge mis/disinformation while interacting with library staff face-to-face, when completing assigned tasks, they lack the skills to critically evaluate information and are also increasingly sceptical of all information sources (Addy, Citation2020; Albert et al., Citation2020) (Hanz & Kingsland, Citation2020). Several studies have investigated how students evaluate information including news stories and information through social media. These studies found that students (high school and college) had challenges evaluating information on social media accurately including recognising information from fake URL’s, recognising bias and did not investigate the authority of the news stories outside of the social media platform (Evanson & Sponsel, Citation2019; Johnston, Citation2020).

In regard to mis/disinformation and library collections there is very little published research available. Bangani (Citation2021), describes purchasing credible material and fake news books which support research as a way that collection development can assist libraries combat misinformation. De Paor and Heravi (Citation2020) suggest that having news and current events print resources available will ensure that patrons are appropriately informed. There is some recent literature around the topic of decolonisation and libraries including the process of re-contextualising collections (Crilly, Citation2019), engaging in pluriversal knowledges (Jimenez et al., Citation2022) and valuing indigenous knowledge, the decolonisation of library collections and cultural safety (Mamtora et al., Citation2021). Censorship of collections which can be defined as restricting free access to information through political, social, legal and ethical means (Duthie, Citation2010) is also a topic of discussion in the literature where the professional stance is one of anti-censorship and ensuring unrestricted and open access to information for library users (Moody, Citation2005). Self-censorship through the selection process undertaken by librarians, reliance on subscriptions packages and vendor acquisitions, labelling of controversial materials, selection based on citations, and a lack of independently published materials can influence the collection held in an academic library (Moody, Citation2005; Steele, Citation2018). The reliance on outsourcing of collection development and information control means that librarians are often not evaluating information in their collection for mis/disinformation (Sullivan, Citation2019).

Methods

Research Approach

This study used an intrinsic case study approach. Case studies investigate an issue in depth and work well when studying processes and can based on and industry or country (Denscombe, Citation2014). The purpose of an intrinsic case study is to give a better and deeper understanding, for example, a service or process (Denscombe, Citation2014; Pickard, Citation2013). In this case, the researcher wanted to gain a deeper understanding of Australian university libraries experiences of managing of mis/disinformation in collections or services. Case study research is also an iterative process which allows the researcher to gain an insight into the issues surrounding the case as the case progresses, in this case allowing the research to gain insight based on the progression of the interviews (Pickard, Citation2013).

Research Participants and Sample

The study used purposive sampling which is used in case study design in order to identify information-rich sources to interview or contact for the study as well as a snowballing technique (Pickard, Citation2013). For the interviews, a sample of library managers that manage collections/library services and/or have known expertise through initiatives or programmes or knowledge around mis/disinformation or were contacted to participate in the interviews. The sample size for the interviews was 17 university library managers. For the survey, all library professionals working in university libraries were invited to participate in the survey through various communications through newsletters and email lists.

Recruitment

For the interviews, key library managers were contacted and recruited to the study who had expertise or manage services or collections. A snowballing technique was utilised where managers who were interviewed were also asked to recommend a colleaugue to be interviewed for the study. In case study research it is not necessary to have all of the key informants identified in advance as one respondent could lead to another key informant being identified that needs to be interviewed. Library staff were recruited to the survey through the following library newsletters and email lists; the CAUL newsletter, ALIA newsletter and email list for Deputy Univerity Librarians in Australia.

Data Collection

Data collection included document analysis (literature review and environmental scan of current research in Australia on fake news and mis/disinformation), interviews with key managers from university libraries and a survey to library staff working in university libraries. The interviews were conducted online through Microsoft teams. The survey was conducted in Qualtrics and gathered information from library staff about their experiences with mis/disinformation. The survey and interview questions were formulated after consultation with an expert academic/researcher who was undertaking similar research in public libraries through an ALIA research grant. The interview and survey questions included questions on what practical resources or classes were taught around mis/disinformation, how complaints are managed, if there were collection development policies related to mis/disinformation and general questions about the topic including key issues and barriers related to the research topic. This ensured the validity of the survey and interview questions and allows for future analysis of the combined results to inform an overall picture in Australia of this issue. Ethics approval was granted from Edith Cowan University. The survey and interview questions can be found in Appendices 1 and 2.

Data Analysis

The interviews were transcribed, and a thematic analysis of the data was conducted using NVivo. The survey results were analysed and cross-tabulated in Qualtrics.

Case study research allows for an iterative analysis of the data, therefore thematic analysis occurred throughout the overall process looking overall at the results from both the survey and interviews. The overall themes therefore iteratively emerged throughout the research.

Results

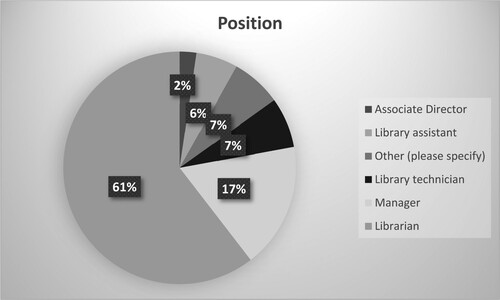

A total of 88 Library staff filled out the survey. 17 interviews were also conducted with library managers across universities in Australia. The interviewees were a mix of managers who manage services, scholarly communication and collections with the majority of the interviews being conducted with Associate Director level managers and above. As shown in , the majority of participants in the survey (61%) were librarians. 71% of respondents to the survey said they keep up to date on the topic through readings, conferences, workshops and social media.

Key Topics

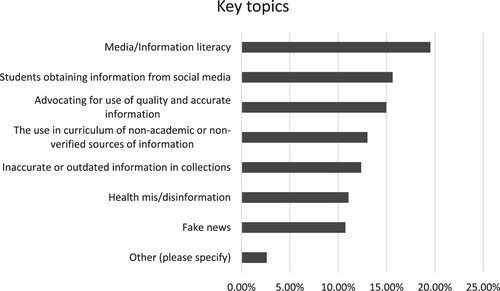

The key topics around mis/disinformation that staff felt were most important to university libraries were media/information literacy and students obtaining information from social media as shown in . Some other key topics mentioned were fake and misleading political discourse, critical literacy and teaching students how to recognise and evaluate reliable sources of information, predatory publishing and fake research and evolving technologies that create fake news or videos.

Current Practice and Skills Related to mis/Disinformation

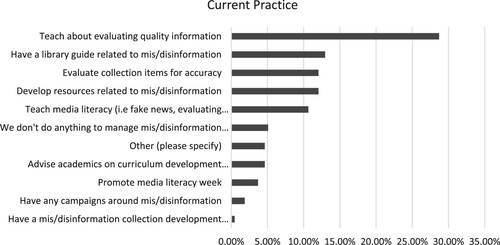

Respondents of the survey were asked about current library practices and skills needed to combat mis/disinformation. As shown in , 29% of respondents stated they teach about evaluating quality information followed by 13% having a library guide related to mis/disinformation. Less than 1% of respondents had a mis/disinformation collection development policy or procedure with less than 2% running any campaigns in this space. Other resources mentioned included a Canvas learning module, ensuring course readings are up to date and including collection items that discuss evaluating dis/misinformation.

Respondents were also asked to rank the most important skills needed to combat mis/disinformation. Critical thinking and evaluating information were seen as the most important skills with understanding digital manipulation of images, videos etc being considered the least important skill ().

Table 1. Skills to combat mis/disinformation.

Role of Libraries

Both respondents of the survey and interviews felt that the role of libraries in mis/disinformation is to advocate in this space and show the libraries expertise on this topic. Interviewees felt that the rise of mis/disinformation has provided opportunities for librarians to show expertise in this space.

An active role of advocacy, communication, research. Countering mis/disinformation is core to our work as educators about information phenomena, is critically important within the research ecosystem, and is directly relevant to our stewardship of collections. (Survey respondent)

I just think it's our profession, dealing with misinformation and disinformation is very much in our wheelhouse and always has been. So, I think the rise of it has actually presented us an opportunity to showcase our professional expertise really and really fight against it. (Manager 2)

However, as one survey respondents points out, the libraries expertise in this space may not always be recognised outside the library, indicating that the role of advocacy is an important one to ensure everyone is aware of libraries expertise.

I think we're perfectly situated to teach students to identify mis/disinformation but some in the university fail to recognise our expertise in the area. (Survey response)

Library staff and managers also felt that the libraries’ role is in providing services in this space including teaching skills around critical thinking, information literacy and evaluation.

So, I do think that there needs to be a greater focus on information literacy in this space and I guess better describing the complexity of the information landscape to our clients. There is a focus at universities especially on scholarly information, but I think that that can lead to disinformation when people take scientific studies and weaponise them to support points. And we've seen this a lot in COVID. (Manager 10)

Promoting critical thinking and teaching/developing resources to develop student skills in information evaluation/media literacy. (Survey respondent)

Library staff and managers also felt the libraries’ role was to ensure that our users are educated on the scholarly process including having conversations around critically evaluating academic information, the peer review process and bias in academia.

I think that there is an expectation around the people that we support, that information that they get through our services is somehow more credible, to be automatically trusted in a way that potentially information on the Internet is not. But I also think that in a large part we're not in control of our collections. We mostly get big deals through the publishers and we're providing a wide variety of information. So, I do think it's important that libraries don’t say, ‘Just because you're getting this through a library, it's automatically to be trusted’. I think that we need to do a lot more in this space around critical evaluation of information. (Manager 10)

Results also showed that respondents felt that it was important that as well as being able to have conversations around scholarly process, libraries also needed to ensure collections are credible and authentic.

Libraries should hold resources that reflect the validated truth at the time. Sources must be scrutinized for authenticity and credibility. (Survey response)

Barriers When Dealing with Mis/Disinformation

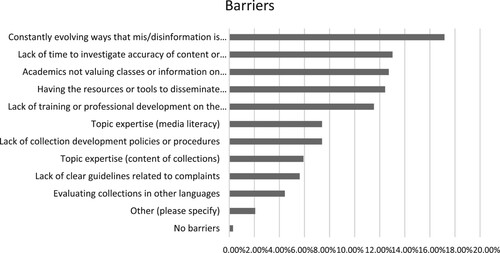

The biggest barrier respondents of the survey felt faced university libraries was the constantly evolving ways that mis/disinformation is spread and a lack of time to investigate accuracy of content or authority of authors in the collection. Managers responding to the survey differ slightly when it comes to which are the most relevant barriers with the highest barriers being concerns around academics not valuing classes or information or having the resources or tools to disseminate information. Librarians, technicians, and assistants all stated the constantly evolving ways that mis/disinformation is spread as the biggest barrier when it comes to mis/disinformation. Library staff felt that staff have a wide scope of responsibilities, and it is difficult to add new areas of expertise to existing roles. They also felt there were misconceptions across the university around the library’s expertise or available services in this area and often a lack of interest in the topic by students.

In the interviews, managers felt that time and resources, assessing collections, the complexity of the issue and teaching barriers were all barriers when managing mis/disinformation. Managers felt there was a lack of time to keep up to date and upskill in this area and a lack of time and resources to do training. There are also decreasing numbers of staff that can prioritise working in this space.

I think probably just time and being able to keep ahead or keep up with what's happening in this space. (Manager 14)

When it came to assessing collections as a barrier it was stated that it is difficult to continually assess large subscription-based collections, maintain subject expertise on content, keep up to date with identifying predatory journals and decide on criteria for how libraries should evaluate content.

I think resourcing, like it's actually quite resource intensive to continually assess your collections. (Manager 9)

Managers also noted the overwhelming amount of information that everyone needs to be aware of on this topic and the complexity of the issue.

When you're working with this kind of material and this sort of knowledge gap for students and staff the barrier is where to go in and where to focus and where to take those opportunities. (Manager 5)

Another major barrier that came up in the interviews was the lack of a priority for this topic in teaching at their universities. Managers felt academics do not also see this as a priority topic the same way library staff do. This barrier was a consistent finding from managers in both the survey and interviews ().

On the service side one of the things is definitely a lack of interest in the topic by our clients. But because I do think that a lot of us are in a position where we don't have endless resources, we need to focus our efforts in areas where we can demonstrate the impact that we're having. (Manager 10)

Guidelines

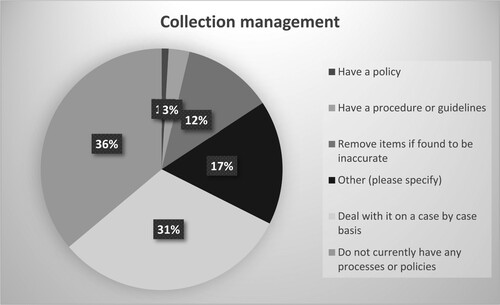

The majority of respondents in the survey stated that they either do not have a process or policy related to collection management and mis/disinformation or deal with it on an ad hoc basis. Some respondents were unsure if there was a policy ().

Results from the interviews revealed that most university libraries do not have any policies/guidelines in this space beyond collection development policies, that this is an emerging area, and that mis/disinformation is mostly not a strategic focus for universities.

We have a Collection Development Policy. Now what is actually in that? I don't know that it deals with misinformation or disinformation specifically … But I think the controversy is around items which would fit in with our collection development parameters and yet some people would still say, ‘well, that it might have research value, but it has unacceptable content in it and we need to warn people of that’. But at the moment we don't have any specific policies about that. It's a sort of an emerging area. (Manager 1)

It probably is a bit of a gap that we don't have a policy within the library that would at least guide the way we talk about this on the services side. (Manager 10)

Complaints

Only around 1% of respondents in the survey reported they had had a complaint or incident related to mis/disinformation. Managers also reported low numbers of complaints. If complaints are received, they are dealt with mostly on an ad hoc basis and there are no overarching guidelines from a university or national level, so libraries have to make decisions case by case. Libraries often use collection policies to argue that the library does not censor items. Libraries are more likely to limit access or provide a warning than remove items from the collection, although on occasion a discredited book or journal article has been removed from the collection. When complaints are received, they are most often related to outdated information, predatory or fake journal articles and complaints related to personal views on content.

Censorship

A strong theme in the interviews was around censorship and how censorship and mis/disinformation can cause conflicting views on the role libraries play in censoring and removing or highlighting instances of mis/disinformation. Questions arose during the interviews around if it is censorship to remove historical information and do libraries need to maintain their neutrality?

I mean the question is, do you consider that say that particular source with, whether it's primary or secondary, in its historical context and point that out to people? Or do you remove it from the collection, which becomes a form of censorship? (Manager 2)

You don't really want to get in the place of being the censor. Because if you start down that, that's a very slippery slope. In terms of collection decisions, some of the things that we've tried to do is have some guidelines that speak to the teaching and learning, and the research, so we collect in those areas. (Manager 4)

The managers felt there needs to be more discussion at a state and national level of the library’s role in countering historical mis/disinformation as there are differing opinions on this and some uncertainty as to our role in this space. Most managers believed that it is not the libraries role to censor materials, but it is useful to provide warning on records that it might no longer be relevant, but important as part of a historical context.

I think generally speaking libraries don't go in for censorship and I think we have the tools available to us if we choose to use them to maybe note the record if it's a controversial book, for example. But it's useful for the study of the history of a particular subject, even if what it contains is no longer relevant. (Manager 13)

The managers also point out that the priority is more around engaging with the users of the information around critically appraising the materials, rather than censorship.

There is so much information out there, both in our own collection but also in the wider sphere. So, we're not just about the books in our buildings and we haven't been for decades. I think it's how people engage with the information that it is more critical than the information itself. We don't want to get into the realm of censorship either. (Manager 5)

Indigenous Collections

A major finding from the interviews was that university libraries are prioritising or planning policies and initiatives related to indigenous collections and decolonising the collections.

I think a lot of libraries are moving into that space, particularly around decolonisation or particularly around diversifying views in the collection, deliberately creating a collection development policy that seeks to be a little bit more diverse. And it recognises we probably do have a bias towards Western information so we will make the effort. But that is not a step that we have reached yet. (Manager 10)

These initiatives include cultural protocols, appointing cultural advisers, indigenous knowledges, flagging incentive materials and setting up facets related to Indigenous collections and creating special collections.

We developed a series of cultural protocols for the library and had engaged with community around these kinds of issues. And we're in the process now of operationalising those protocols. Flagging materials that use kind of insensitive language, there's some practical things that we're working through. (Manager 15)

Industry Support

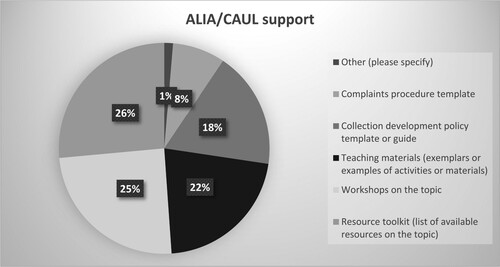

Respondents form the survey stated they would like support from ALIA or CAUL through teaching materials (exemplars or examples of activities or materials), workshops on the topic and resource toolkits ().

Both the surveys and interviews revealed that library staff would like access to national guidelines, toolkits/resources, training including advanced workshop and community of practices on this topic. Staff would like collection guidelines and training to help to manage mis/disinformation in collections and keep up to date on the issue.

The most obvious thing for me would be training and professional development which you know both organisations offer, but perhaps not quite as focused on this particular area … Guidelines around the balance between taking things away and making them inaccessible versus having something that's incorrect in the collection. (Manager 5)

Staff also pointed to good examples of toolkits, resources, forums and community of practices that have been established or could be established in other areas such open education/access and that would be beneficial on this topic as well.

[CAUL] created toolkits and guidelines and workshops and a whole range of things [on open access]. If they want to do something in that space around misinformation and disinformation, I think it would be wonderful. (Manager 16)

Respondents also felt that having national conversations around this topic would be beneficial to libraries.

Would be good to facilitate national conversations on the topic using researchers in this space from Australian universities as they have substantial knowledge of the area to share. (Survey respondent)

Discussion

Library staff believe they have a role in teaching skills such as critical thinking and evaluation, advocating in this space and maintaining credible, balanced and inclusive collections. Libraries often teach in this space or have a library guide on this topic which is also well documented in the literature as one of main roles academic libraries have in managing mis/disinformation (De Paor & Heravi, Citation2020; Revez & Corujo, Citation2021). Library staff face a number of barriers to being able to effectively manage mis/disinformation including the complexity of the issue, the constantly evolving ways that mis/disinformation is spread, a lack of time to investigate accuracy of content or authority of authors in the collection and time and resources to learn more about this topic. Some of these barriers could be alleviated through support from LIS bodies through training, provision of resources and advocacy from national bodies on the importance of critical information literacy and media literacy as skills to be prioritised in higher education.

Universities libraries don’t have guidelines or policies in this space beyond collection management procedures and deal with complaints on an ad hoc basis which is reflected in the lack of literature around collection management and mis/disinformation beyond recommendations to include materials on the topic itself in collections (Bangani, Citation2021). Libraries receive a low number of complaints related to collections mostly related to outdated information, personal views and predatory journals and are more likely to limit access to items than remove items after complaints. Most managers felt that it is not the library’s role to censor information, and there is a need to maintain historical records, but with warnings around content. Interestingly adding warnings or labelling controversial items is in itself can be seen as a form of self censorship within libraries (Moody, Citation2005). There are various aspects to collection management including physical and digital collections, with librarians having limited control of the content, with print collections often being purchased through recommendations and digital collections being purchased as large subscriptions. The way academic libraries manage digital acquisitions through large vendor subscriptions also means that it is becoming more difficult to maintain subject expertise including the ability to assess if the collection contains any mis/disinformation (Sullivan, Citation2019). Moody (Citation2005) also argues outsourcing acquisitions to vendors can create biased collections.

The interviews also showcased how university libraries are prioritising or planning policies and initiatives related to indigenous collections and decolonising the collections, an area increasingly being discussed in the literature as a way for libraries to value indigenous knowledge, create culturally and inclusively safe spaces, recontextualise collections and engage in pluriversal knowledge (Crilly, Citation2019; Jimenez et al., Citation2022; Mamtora et al., Citation2021). There is an interesting dichotomy currently at play in libraries concurrently balancing libraries anti-censorship stance by providing unrestricted access to information, managing historical records of information and decolonising collections with more discussion and leadership needed at a national level on the library’s role in countering historical mis/disinformation.

Conclusion

Library staff in Australian academic libraries convey that libraries play a major role in managing dis/misinformation, however there is often a disparity between the library’s view of the importance of their role and their university’s strategic priorities or lack of in this area. University libraries see their role as experts in this space, but often it is not a strategic priority of the university. Australian universities libraries do not have guidelines or policies on mis/disinformation beyond collection management procedures.

Many library staff participating in this study indicated there was a lack of discussion at a national level of the library’s role in countering historical mis/disinformation in their collections. Library staff also look to organisations such as ALIA/CAUL for support through guidelines, professional development and training, resources and community of practices to support them to continue to combat fake news, teach critical evaluation skills and maintain credible balanced and inclusive collections. This research has implications for library practice as it highlights the importance of the library’s role in combating mis/disinformation and library staffs’ expertise in this area, but that more advocacy and support is needed to continue to showcase this expertise and overcome barriers that library staff face in managing mis/disinformation. This research also has implications for future planning of collection management policies and guidelines with strategies and resources to help library staff identify mis/disinformation and manage historical misinformation in collections needed at an institutional and national level.

Recommendations

It is recommended that national and international associations advocate more around the importance of critical information literacy and the important role played by academic libraries in combating mis/disinformation through education and teaching, leading to essential lifelong critical evaluation skills for students.

It is recommended that Library associations develop guidelines or policies to help support librarians manage any mis/disinformation in their collections. This could include complaint procedures, example collection management policies or clauses or evaluation criteria for identifying mis/disinformation in collections.

It is recommended that professional development activities such as training, resource development and community of practices are developed on topics related to mis/disinformation and more research on mis/disinformation and library collections is conducted in Australia. This could include collation of resources already developing on the topic, information literacy training materials, development of media literacy courses, and a community of practice to share ideas and best practice and funding allocated to conduct research in this space.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nicole Johnston

Dr Nicole Johnston is the Associate University Librarian at Edith Cowan University in Perth Australia.

References

- Addy, J. M. (2020). The art of the real: Fact checking as information literacy instruction. Reference Services Review, 48(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-09-2019-0067

- Albert, A. B., Emery, J. L., & Hyde, R. C. (2020). The proof is in the process: Fostering student trust in government information by examining its creation. Reference Services Review, 48(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-09-2019-0066

- Auberry, K. (2018). Increasing students’ ability to identify fake news through information literacy education and content management systems. The Reference Librarian, 59(4), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2018.1489935

- Bangani, S. (2021). The fake news wave: Academic libraries’ battle against misinformation during COVID-19. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(5), 102390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102390

- Batchelor, O. (2017). Getting out the truth: The role of libraries in the fight against fake news. Reference Services Review, 45(2), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-03-2017-0006

- Burkhardt, J. M. (2017). Combating fake news in the digital age (Vol. 53). American Library Association.

- Chandler, D., & Munday, R. (Eds.). (2020). Misinformation. A dictionary of media and communication (Vol. 3). Oxford University Press.

- Clough, H., & Closier, A. (2018). Walking the talk: Using digital media to develop distance learners’ digital citizenship at the Open University (UK). The Reference Librarian, 59(3), 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2018.1468848

- Crilly, J. (2019). Decolonising the library: A theoretical exploration. Spark: UAL Creative Teaching and Learning Journal, 4(1), 6–15.

- De Paor, S., & Heravi, B. (2020). Information literacy and fake news: How the field of librarianship can help combat the epidemic of fake news. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46(5), 102218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102218

- Denscombe, M. (2014). The good research guide: For small-scale social research projects. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Duthie, F. (2010). Libraries and the ethics of censorship. The Australian Library Journal, 59(3), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049670.2010.10735994

- Eva, N., & Shea, E. (2018). Amplify your impact: Marketing libraries in an era of “fake news”. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 57(3), 168–171. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.57.3.6599

- Evanson, C., & Sponsel, J. (2019). From syndication to misinformation: How undergraduate students engage with and evaluate digital news. Communications in Information Literacy, 13(2), 228–250, 228A. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2019.13.2.6

- Faix, A., & Fyn, A. (2020). Framing fake news: Misinformation and the ACRL framework. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 20(3), 495–508. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2020.0027

- Hanz, K., & Kingsland, E. S. (2020). Fake or for real? A fake news workshop. Reference Services Review, 48(1), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-09-2019-0064

- Jimenez, A., Vannini, S., & Cox, A. (2022). A holistic decolonial lens for library and information studies. Journal of Documentation, 79(1), 224–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-10-2021-0205

- Johnston, N. (2020). Living in the world of fake news: High school students’ evaluation of information from social media sites. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 69(4), 430–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2020.1821146

- Krutkowski, S., Taylor-Harman, S., & Gupta, K. (2020). De-biasing on university campuses in the age of misinformation. Reference Services Review, 48(1), 113–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-10-2019-0075

- Lim, S. (2020). Academic library guides for tackling fake news: A content analysis. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46(5), 102195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102195

- Mamtora, J., Ovaska, C., & Mathiesen, B. (2021). Reconciliation in Australia: The academic library empowering the indigenous community. IFLA Journal, 47(3), 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035220987578

- Moody, K. (2005). Covert censorship in libraries: A discussion paper. The Australian Library Journal, 54(2), 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049670.2005.10721741

- Musgrove, A. T., Powers, J. R., Rebar, L. C., & Musgrove, G. J. (2018). Real or fake? Resources for teaching college students how to identify fake news. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 25(3), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2018.1480444

- Neely-Sardon, A., & Tignor, M. (2018). Focus on the facts: A news and information literacy instructional program. The Reference Librarian, 59(3), 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2018.1468849

- Pickard, A. J. (2013). Research methods in information. Facet.

- Revez, J., & Corujo, L. (2021). Librarians against fake news: A systematic literature review of library practices (Jan. 2018–sept. 2020). The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(2), 102304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102304

- Steele, J. E. (2018). Censorship of library collections: An analysis using gatekeeping theory. Collection Management, 43(4), 229–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2018.1512917

- Sullivan, M. (2019). Libraries and fake news: What’s the problem? What’s the plan? Communications in Information Literacy, 13(1), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2019.13.1.7

- Wade, S., & Hornick, J. (2018). Stop! don’t share that story!: designing a Pop-Up undergraduate workshop on fake news. The Reference Librarian, 59(4), 188–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2018.1498430

Appendices

Appendix 1. Survey Questions

Survey Questions

By completing this survey, you agree that the information will be reported on in reports, journal articles and conference proceedings. The survey is anonymous, therefore you cannot withdraw from the study at a later date once you have completed the survey.

What is your position?

Library assistant

Library technician

Librarian

Manager

Associate Director

Director

Other (please specify)

What do you think are key topic areas on mis/disinformation that are most important to Australian university libraries? (you can choose more than one)

Fake news

Inaccurate or outdated information in collections

Advocating for use of quality and accurate information

Media/Information literacy

Health mis/disinformation

The use in curriculum of non-academic or verified sources of information

Obtaining information from social media

Other (please specify)

At your university Library do you do any of the following?

Teach media literacy (i.e. fake news, evaluating information in media)

Teach about evaluating quality information

Have a library guide related to mis/disinformation

Develop resources related to mis/disinformation

Have a mis/disinformation collection development policy or procedure

Promote media literacy week

Have any campaigns around mis/disinformation

Advise academics on curriculum development related to mis/disinformation

Evaluate collection items for accuracy

Other (please specify)

Have you ever had an incident or complaint at your library related to mis/disinformation?

Yes

No

If yes, please specify what the complaint or incident

5. What skills do you think students need to combat mis/disinformation or fake news

Evaluating information

Critical thinking

Understanding bias (both self and information)

Read critically

Know how to find facts

Know how to establish authority

Understand digital manipulation of images, videos etc.

Recognise authority/verification in social media

Differentiate between fact and opinion

Other (please specify)

6. What type of barriers do you think exist for Australian university libraries when dealing with mis/disinformation?

Lack of training or professional development on the topic

Lack of clear guidelines related to complaints

Lack of collection development policies or procedures

Topic expertise (content of collections)

Topic expertise (media literacy)

Evaluating collections in other languages

Constantly evolving ways that mis/disinformation is spread

Having the resources or tools to disseminate information about mis/disinformation to students and academics

Academics not valuing classes or information on media, information or digital literacy

Lack of time to investigate accuracy of content or authority of authors in the collection

No barriers

Other (please specify)

7. Do you do any reading or keep up to date on the latest developments or issues in this area?

Yes, read peer reviewed articles on the topic

Yes, attend workshops or conferences on the topic

Yes, keep up to date through social media or industry updates

No, don’t keep up to date on the topic

Yes, Other (please specify)

8. How do you currently manage mis/information in your collections?

Have a policy

Have a procedure or guidelines

Deal with it on a case by case basis

Remove items if found to be inaccurate

Do not currently have any processes or policies

Other (please specify)

9. What resources would you like from organization such as ALIA or CAUL that could help you manage with mis/disinformation?

Teaching materials (exemplars or examples of activities or materials)

Resource toolkit (list of available resources on the topic)

Collection development policy template or guide

Workshops on the topic

Complaints procedure template

Other (please specify)

10. What role do you think university libraries play in countering mis/disinformation?

Open question

Other comments

Appendix 2. Interview Questions

Interview Questions

Tell me a little bit about your position.

To what degree do you think mis/disinformation is an issue in Australian libraries in general?

What about your own library?

What key topic areas on mis/disinformation do you think are most important to Australian university libraries?

–Do you do any reading or keep up to date on the latest developments or issues in this area?

Which area do you think mis/disinformation impacts more: services or collections?

–Why do think this is?

Do you have any resources, guides or policies related to mis/disinformation at your Library?

Do you teach any classes on mis/disinformation, fake news or media literacy?

Can you tell me about an incident or complaint at your own library related to mis/disinformation?

– How did you deal with this issue at the time?

– Was there anything at the time you wish you had known that you didn’t?

– Have you followed up with any other measures?

Have you ever had any mis/disinformation issues that have involved your collection?

–If so, tell me more about what happened.

–Would you like to have guidelines in how to deal with these issues?

What type of barriers do you think exist for Australian university libraries when dealing with mis/disinformation?

How do you think ALIA or CAUL could help information professionals deal with mis/disinformation?