Abstract

The three earliest – all eighteenth-century – illustrated accounts of birds’ eggs were by Luigi Marsili (or Marsigli): Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus, Giuseppe Zinanni (or Ginanni): Delle Uova e dei Nidi degli Uccelli, and Jacob Theodor Klein: Ova avium plurimarum ad naturalem magnitudinem delineata et genuinis coloribus picta. Marsili’s account describes and illustrates the nests and eggs of just 15 different birds (whose identity is sometimes uncertain), which together with 59 plates of birds forms part of a multi-disciplinary account of the River Danube. Zinanni’s volume (which also includes an appendix on grasshoppers) describes the nests and eggs of 106 birds, and is more extensive and accurate since he shot the adult birds attending nests from which the illustrated eggs were collected. Zinanni’s book includes 34 black-and-white engraved plates each with between one and nine eggs of species that (excluding domesticated or exotic species) were probably those that occurred around his home in north-east Italy. Klein’s volume includes 145 coloured plates of eggs – the first published coloured images of eggs – and his classification of birds based on feet and toes. We present some biographical information and details of each author’s career and a summary of their books’ contents. The text of Zinanni’s volume is the most “philosophical” of the three and includes a discussion – based on the writings of Lorenzo Bellini and Antonio Vallisneri – of what he calls “airways” within the egg that have apparently not been noticed or commented on by subsequent researchers.

Introduction

The huge encyclopedias of natural history and ornithology by Gessner (Citation1555), Belon (Citation1555), Aldrovandi (Citation1599–Citation1603) and Jonston (Citation1657) included very few descriptions of birds’ eggs and no more than one or two “incidental” images of eggs. The eggs of wild birds became objects of curiosity and were accumulated in the personal “cabinets” of “curious” individuals only in the middle of the seventeenth century at the start of the scientific revolution. Among the first of those to possess collections of eggs were Sir Thomas Browne (1605–1682) and Francis Willughby (1635–1672) (Birkhead et al. Citation2016).

Ray’s Ornithology of Francis Willughby (Citation1676, Citation1678), based in part on Willughby’s notes and his and John Ray’s joint investigations, is generally considered to be the first “scientific” book on birds (e.g. Newton Citation1896; Stresemann Citation1975). The Ornithology [we refer to both editions, the Latin (Ray Citation1676) and the English (Ray Citation1678), together as “the Ornithology”; the two editions are similar (but see Birkhead et al. Citation2016 for differences)] provides accurate descriptions and identifications that Willughby and Ray used to create the first biologically meaningful classification of birds. Their volume included images of almost all (~500) bird species thought to exist at that time, and although the eggs of a small number of species are described in the text, the Ornithology contains only a single, incidental image of an egg (of an ostrich; pl. 25). As pointed out elsewhere, the lack of consistent descriptions of eggs in the Ornithology is surprising because it is known that Willughby made a collection of birds’ eggs (Birkhead et al. Citation2016; Birkhead Citation2018). Similarly, the Ornithology includes a few comments on birds’ nests, but no systematic account of them.

Our aim in this paper is to provide an account of the three earliest books on birds’ eggs: (i) Marsili’s Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus (Citation1726); (ii) Zinanni’s Delle Uova e dei Nidi degli Uccelli (Citation1737); and (iii) Klein’s Ova avium plurimarum ad naturalem magnitudinem delineate et genuinis coloribus picta (Citation1766). Little appears to have been written about these books or their authors, and given the current “renaissance” in the study of birds’ eggs (Cassey et al. Citation2011; Birkhead Citation2017), it may be useful to review the beginnings of this scientific endeavour.

Earlier Italian books on birds focus on bird keeping and include no information about birds’ eggs (e.g. Manzini Citation1575; Aldrovandi Citation1599–Citation1603; Valli da Todi Citation1601; Olina Citation1622).

Marsili’s Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus (Citation1726)

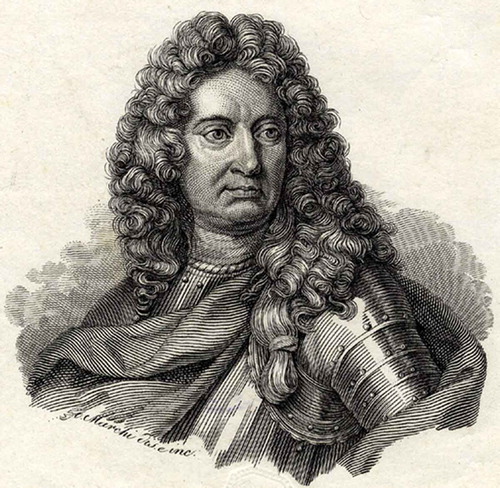

Luigi Ferdinando Marsili (1658–1730) () was an Italian aristocrat, soldier, scholar (elected Fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1691) and naturalist who published on a wide range of topics (Stoye Citation1994). His lavishly illustrated six-volume multi-disciplinary account of the river Danube, Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus (Marsili Citation1726), whose full title in English is Geographic, astronomic, hydrographic, historic and physical observations on the Mysian Pannonian, explored, and arranged in six volumes by Aloysio Ferdinando Marsili, Fellow of the Royal Society of Paris, London and Montpellier, includes (in volume 5) details of the birds, their nests and eggs of the river.

Figure 1. Portrait of Luigi Ferdinando Marsili (1658–1730) (from http://badigit.comune.bologna.it/mostre/archeologia/bacheca%203/big/37_ct_01.JPG).

In the general introduction to volume 5 Marsili presents a classification of birds, based, he says, on Willughby’s Ornithology (i.e. Ray Citation1676). His first group is of birds that live beside water, but do not swim in it. The second group he divides into “Fissipedes-Longicrures” (birds whose toes are separated, with long legs) and “Palmipedes-Brevicrures” (birds with webbed feet and short legs). Birds in each group are further subdivided into “Advenas” and “Inquilinas”. The former (literally “foreigners”) are either summer or winter visitors. The “Inquilinas” (literally inhabitants) are the birds that are resident throughout the year. All these birds, he says, differ in their diet: (a) some feed on fish, but also on plants, mud (literally) and insects, that he calls “piscivorous” (and states that these are the birds with the stronger odour); (b) “Limofuguas” (literally: slime-eaters, i.e. waders; see Ray Citation1678, pp. 9, 273); (c) “Insectivoras” (insectivorous), (d) “Seminivoras” (seed eaters), and (e) herbivores.

Marsili also states that his aim is to provide information on nesting, which no one has done previously, despite its importance. Finally, he states that while referring to the species described by Willughby, he also includes species whose description he was unable to find in Willughby, but that he says he has seen himself, indicating these in the text as “Nova species”, all herons: Ardea cinerea flavescens (p. 20), identity unknown; Ardea viride-flavescens (p. 22), identity unknown; and Ardea fusca (p. 24), which according to later authors (e.g. Schembri Citation1846) should be the little bittern Ardeola minuta. None of these names occurs in Aldrovandi (Citation1599–Citation1603) or Ray (Citation1676). Finally, Marsili provides a dichotomous table (p. 3) where the groups of birds are classified according to the above criteria (swimmers and not swimmers) and other criteria, such as body size, length of leg and bill, webbed foot or not, number of toes (three or four), the shape of the bill (narrow-wide, long-short, straight-curved), habitat (marine, or freshwater), and short or long wings.

Stoye (Citation1994, p. 157) in his detailed appraisal states that “Marsigli did not normally parade an enthusiasm for ornithology in his writings, as he does for geology and certain other branches of natural history”, suggesting that birds were not a major priority in his overview of the Danube. This may explain Marsili’s less than careful identifications and text.

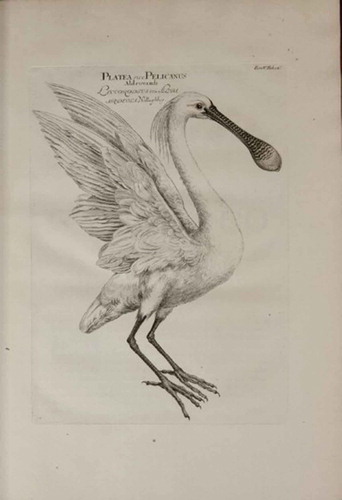

The main bird section following the Introduction (pp. 5–123) includes a brief description and illustrations of 59 birds () after the drawings by the Italian artist Raimondo Manzini (1658–1730), court painter to the Duke of Modena and the Margrave Ludwig-Wilhelm of Baden-Baden (Anker Citation1938). The 59 birds are not 59 “species” because it is clear that Marsili struggled to identify some birds, even though he clearly used reference books such as Gessner (Citation1555), Jonston (Citation1657) and Ray (Citation1676), thus emphasising how difficult unambiguous bird identification was at that time. In several instances Marsili’s illustrations are of immature birds (e.g. gulls and terns), and in some cases the names are ambiguous. The birds included are all aquatic species, and comprise herons, waders, grebes, cormorant and waterfowl.

Figure 2. An example of one of the bird plates, in this case the Eurasian spoonbill, from Marsili’s account.

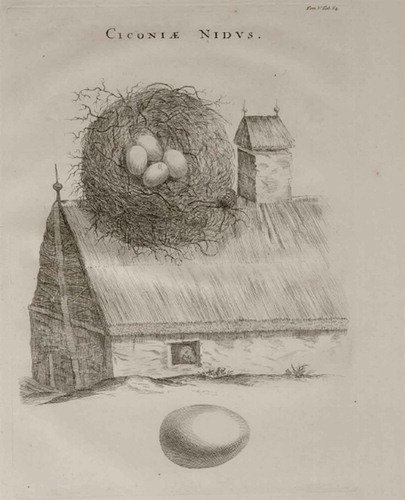

The section on nests and eggs (pp. 123–156), accompanied by illustrations of 15 nests with eggs (), starts with a one-page account in which Marsili states his aim of describing the shape of nests, the type of material used and the number, size and colour of eggs. He also includes some general statements, including: (i) that the eggs of aquatic birds have a stronger shell that those of terrestrial birds; (ii) that eggs have four membranes: two external ones containing the albumen (the shell membrane and egg membrane – for details of avian egg structure and terminology see Romanoff & Romanoff Citation1949); an internal one containing the yolk (the perivitelline layer), and an intermediate one separating the thicker and the liquid parts of the albumen (in fact, there is no membrane separating the two types of albumen) – this information is from William Harvey’s Exercitationes de generatione animalium (Citation1651, see Whitteridge Citation1981); (iii) that the eggs of aquatic birds contain (relatively?) more albumen than those of terrestrial birds, and are usually “healthier” (in Latin “sanus”), meaning more likely to hatch. Marsili repeats what some previous authors had (incorrectly) assumed: that the embryo derives its nutrition from the albumen rather than the yolk. However, Marsili also says that the eggs of aquatic birds have a (relatively) long incubation period, and may fail to complete their development because of the humidity or the cold they are subjected to as a result of being incubated so close to water.

Figure 3. Example of one of the nest and egg plates from Marsili, in this case the white stork Ciconia ciconia. Note that the building and nest and eggs are not to scale.

The rest of this section comprises descriptions of the nests and eggs of just 15 birds, several of whose identities are unclear to us. They may, of course, have been unclear to Marsili, since without seeing or killing the adults attending a nest, identification is often difficult (cf. Zinanni below). Those birds whose identity we are fairly certain of in Marsili’s account include the common crane Grus grus, white stork Ciconia ciconia, great cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo, mute swan Cygnus olor, lapwing Vanellus vanellus and great-crested grebe Podicpes cristatus (although Marsili refers to it only as a grebe). Marsili provides information on clutch size, egg colouration and egg dimensions (length and breadth) in “inches” and mass (in “pounds”), but as there was no standardisation of measurements at this time, it is not clear how his measurements relate to those in use today. As an aside, it is interesting that Marsili refers several times (e.g. pp. 58, 60, 86) to the beautifully illustrated unpublished manuscript produced by Leonhard Baldner (1612–1694) during the 1660s, on the birds of the Rhine. Marsili must have seen this when visiting Strasbourg in 1682 (Stoye Citation1994), where Baldner lived (Lauterborn Citation1903; Fluck & Scharbach Citation2016).

Marsili’s work seems to have been cited (and usually only briefly) by relatively few authors, including Zorn (1742–1743), who had probably not actually seen it, Nitze Citation2001), Wirsing (Citation1772), Newton (Citation1896), Thompson (Citation1917), Wood (Citation1931) and Anker (Citation1938), although we have not made an exhaustive search for such citations.

Zinanni’s Delle Uova e dei Nidi degli Uccelli (Citation1737)

The full title of Zinanni’s book in English is: Of the eggs and the nests of the birds. First book of the Count Giuseppe Zinanni, from Ravenna, with the addition of some observations, with description, on various species of grasshoppers.

Giuseppe Zinanni, or Ginanni (1692–1753) (), was born in Ravenna, north-east Italy, on 7 November 1692. His parents, Count Prospero and Countess Isabella Fantuzzi, died when Zinanni was young and he was raised by his paternal grandparents. After they died (when he was just seven), he was sent to a Jesuit school. In 1715, at the age of 23, Zinanni visited Antonio Vallisneri (1661–1730) who held the chair of medicine at Padua, and who encouraged Zinanni’s interest in natural history. Although Zinanni focussed initially on botany, from 1732 to 1737 he made a special study of birds’ eggs and it was this work that resulted in his book. Zinanni became a fellow of Italy’s premier scientific society, the Accademia dei Lincei di Rimini, and of the Accademia dell’Istituto delle Scienze di Bologna after the publication of his book (Ongaro Citation2000).

Figure 4. Portrait of Giuseppe Zinanni (from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Giuseppe_Ginanni.jpg, in the public domain).

Zinanni states that because other published accounts are incomplete and sometimes inaccurate, the aim of his book is to provide an account of birds’ eggs. Interestingly, he does not mention Marsili’s book, possibly because he did want to acknowledge any competition, or because he was unaware of it, although the latter seems unlikely. Zinanni describes the ground colour, the colour and type of maculation, the nature of the eggshell (its thickness, whether it is fragile or robust, its surface: smooth, uneven, shiny), and the presence of visible pores. There is no mention of egg size or shape in the text, presumably because this can be derived from the plates. Indeed, in the description of the eggs of the peafowl Pavo cristatus, Zinanni states (p. 26) that he “will not mention the size of the eggs of this nor any species in the book, as they are represented in their natural size in the plates”.

Zinanni also presents a description of each species’ nest, its location (e.g. on the ground, in a tree), clutch size, the timing of breeding and the number of broods each year. His account is restricted to species that he was able to collect personally, or that were provided to him as fresh samples by collaborators. Zinanni states that the adult birds attending the nest were killed, and identified using the books by Aldrovandi (Citation1599–Citation1603) and Willughby (Ray Citation1676). Eggs were collected (where possible before embryo development started), emptied, dried and placed in his personal collection, Piccolo Museo di cose naturali, at his home. In addition to such personal collections Zinanni encourages “official” museums to make similar collections, not least, he says, because eggs retain their colours so well after they are emptied.

After Zinanni’s death, his nephew, Francesco Zinanni, published an account of the collections of eggs and other “natural things” comprising G. Zinanni's museum (Zinanni Citation1762). From this we know that Zinanni probably continued to add to his collection after his own book was published since the list of eggs F. Zinanni notes in the museum (pp. 142–161) includes species not mentioned in the book. Interestingly, apart from eggs and nests, only the head and the legs of the birds were preserved in Zinanni’s museum, presumably because taxidermy techniques at that time did not allow good preservation of the body. This is confirmed in Zinanni’s (Citation1737) book, when in trying to convince the reader of the value of collecting and preserving eggs, he states: “considering that it is impossible to preserve the birds because they get rotten, at least it will be possible to show the eggs from which each bird species was originated” (pp. 8–9). We know from F. Zinanni’s book that nests, eggs and adults were not always collected simultaneously (which as Zinanni states in the introduction is essential to guarantee the correct identification of eggs and nests). Indeed, the year after publishing his book, G. Zinanni wrote (20 January 1738) to the French naturalist René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur, admitting that he had made a mistake and that the nest and the eggs of what he thought was the long-tailed tit Aegithalos caudatus were actually those of a penduline tit Remiz pendulinus. He states that the mistake occurred because a nest with eggs and the bird were provided by a collaborator from Tuscany, where the local name of the long-tailed tit is “pendolino” (which also was, and still is, the Italian name for the penduline tit). (Zinanni Citation1762, n. 287, pp. 151–152).

During the time G. Zinanni was collecting and studying eggs he maintained a vigorous correspondence with the physician and scientist Giovanni Bianchi (also known as Iano Planco; 1693–1775) from Rimini. There are 78 letters (dated between 1730 and 1752) between Zinanni and Bianchi preserved in the Fondo Gambetti at the public library of Rimini. The first letter mentioning the preparation of G. Zinanni’s book is dated 8 January 1735. From a subsequent letter by Zinanni (22 January 1735) it is clear that Bianchi had encouraged Zinanni to complete the book. On 25 March 1735 Zinanni tells Bianchi that the engraving of the egg plates has started, although in a later letter he complains that the engraver is not proceeding as fast as he would like. Then on 24 September (1735) Zinanni writes to tell Bianchi that the book will be ready at the end of the 1735–1736 winter. In a letter dated 28 January 1736, Zinanni informs Bianchi that he has been told of “the existence of a textbook on birds by Willughbeio”. To “see what this author has written about birds” Zinanni purchases not only the Ornithology (Citation1676) but also Willughby’s book on fishes, Historia Piscium (Ray Citation1686). Zinanni complains to Bianchi that the Ornithology was expensive (nine gold scudi), but also says that the books were worth their price, because “the English man makes perfect descriptions of the birds, and their eggs and nests” (This is not true: Ray (Citation1676) includes very little information on eggs). Zinanni further states that Willughby’s Ornithology will not affect the importance of his own book, since he will describe the eggs of a greater number of species and will also – unlike Willughby – provide illustrations of the birds’ eggs (letter from Zinanni to Bianchi dated 28 January 1736, Fondo Gambetti, Public Library of Rimini, Italy; see also Montanari Citation2002).

Zinanni’s book was printed in Venice at the beginning of 1737 (probably in March). Books authored by citizens of the Papal State had to be granted “imprimatur”, an official licence issued by the Sant’Uffizio (the censoring authority of the Roman Catholic Church), even if the publisher was outside the Roman state (such as in Venice). Failure to obtain this permission could result in the book being added to the list of those forbidden by the Sant’Uffizio. Apparently unaware of the necessity for official permission, Zinanni went ahead with the printing and the Sant’Uffizio blocked the circulation of the book. However, on 16 July 1737, he received official approval and was able to legally send copies of his book to colleagues. However, it seems likely that some copies were available before 16 July since it was on the basis of this book that Zinanni was elected to the Accademia dell’Istituto delle Scienze di Bologna on 8 July 1737 (Ongaro Citation2000).

Delle Uova e dei Nidi contains some novel taxonomic suggestions (discussed below), but Zinanni’s objective was not to provide a new taxonomy. Instead, he states that the taxonomies presented by previous authors, including Aldrovandi (Citation1599–Citation1603), Jonston (Citation1657) and Willughby (Ray Citation1676), are adequate. Nonetheless, he introduces his own taxonomy (based on the utility of birds and the effect they have on our senses), because, he says, it is easier to understand by those lacking access to the classic ornithological texts.

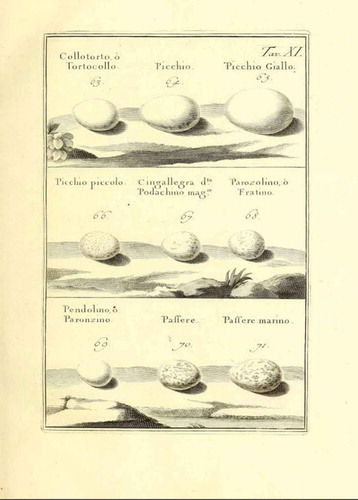

Zinanni’s book is illustrated with 34 black-and-white plates each containing between one and nine eggs of some 106 “species” (). Eleven of these are domesticated or exotic species, several of whose eggs are illustrated twice (e.g. peafowl Pavo cristatus and white peafowl; canary Serinus canaria, both green [i.e. wild type] and white [domesticated]). Although it is not possible to identify with certainty all the species whose eggs are illustrated by Zinanni, we estimate that they comprise around 75 different species, all of which could have been obtained locally near his home in north-east Italy (see below).

Figure 5. Example of a plate from Zinanni’s book, showing (from left to right), first row: wryneck, great spotted woodpecker (64), lesser spotted woodpecker 65; second row: treecreeper (66); great tit (67); blue tit (68); third row: penduline tit (erroneously attributed by Zinanni to long-tailed tit – see text and ); house sparrow (70); rock sparrow? (71).

Structure of the book: introduction part 1

Zinanni’s book comprises a lengthy two-part introduction, followed by individual species accounts. In the first part of the introduction Zinanni describes how he came to write the book. He is surprised, he says, that despite the recent publication of beautifully illustrated books on the way molluscs and plants reproduce through the production of eggs and seeds, respectively, no one had previously thought doing the same for birds, given that they are so diverse, and beautiful. Zinnani cites here the work on snails by Filippo Bonanni (1638–1723), probably referring to his book Ricreatione dell’ occhio e della mente (Bonanni Citation1681), the first book completely dedicated to seashells; on plant seeds by the French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656–1708); and on fungi by Pier Antonio Micheli (Italian botanist, 1679–1737), curator of the Florence Botanical Garden and professor at the University of Pisa, best known for discovering the spores of mushrooms.

Zinanni states that although previous authors such as Pliny and Aldrovandi showed an interest in the variety of birds’ eggs, they failed to provide comprehensive accounts of the interspecific variation in egg shape and colour, and Pliny in particular made mistakes in his account. Zinanni cites Pliny’s description of some eggs: “Ovorum alia sunt candida, ut in Columbix et Perdicibus: alia pallida, ut in aquaticis: alia punctis distincta, ut in Melleagradi: alia rubris coloris, ut in Phasianis” (Plinius, lib. X, p. 52; translation: “Other eggs are white, as in pigeons and partridges; others are clearly spotted, as in the Numidia fowl, whereas others are red, as in pheasants”). Aldrovandi, Zinanni says (p. 4), corrected Pliny’s statements in his Ornithologiae vol. XIII, p. 51: “Ova quedam punctis distincta sunt, ut Melleagridum et Phasianorum: Rubrum Tinnunculi” (translation: “Some eggs are distinctly spotted, as in the Numidia fowl [Guinea fowl Numidia spp.] and in pheasants, whereas they are red in kestrel” [presumably common kestrel Falco tinnunculus]). Thus, pheasants’ eggs are not red, as Pliny suggested, but spotted. Furthermore, Zinanni says, partridges’ eggs are not white, but rather grey (p. 5). Zinnani notes that although some eminent ornithologists, such as Aldrovandi and Willughby, had published excellent books on birds, they gave little information on egg colour and shape, nest structure, or the timing of reproduction.

Zinanni adopted a precise protocol to collect the information necessary for his book: before collecting the eggs in a bird’s nest, the bird was killed and accurately compared with the description given by Aldrovandi and Willughby. The nest structure was noted, and the eggs were emptied, dried and preserved in Zinanni’s personal collection. This approach, Zinanni says (p. 8), allows the egg colour to be preserved. For each species, Zinanni provides a reference to the figures in Aldrovandi and Willughby’s books, to minimise the risk of misidentification.

This section is followed by information on the timing of breeding, which he says has not been published previously. He also states (p. 11) that his observations on the timing of breeding (and number of broods per year) are original, but cautions that breeding seasons can vary depending on whether it is a cold or warm spring.

To reinforce the importance of his book, Zinanni reminds readers that birds’ eggs and embryo development have attracted the attention of many great scientists, including Fabricius, William Harvey and Marcello Malpighi. Zinanni refers to Fabricius’s book De formatione ovi et pulli (Citation1621), Harvey’s Exercitationes de generatione animalium (Citation1651), and Malpighi’s De Formatione de pulli in ovo (Citation1673).

It is in this first part of the introduction that Zinanni presents a brief account based on the writings of Bellini (Citation1695, Citation1710)) and Vallisneri (Citation1733), of what he (in translation) calls “airways” within the egg, that, he says (incorrectly), are connected to the eggshell pores and transport the air from one end of the egg to other. The airways described by Zinanni have been largely ignored in the subsequent oological literature and we therefore provide here a more precise account of the literature cited by Zinanni. Zinanni’s account of the “airways” in birds’ eggs is difficult to follow, as are the sources he cites (i.e. Vallisneri Citation1733 and Bellini Citation1710), but a letter from Bellini to Vallisneri published by Vallisneri in Citation1710 in the scientific journal Giornale De’ Letterati D’Italia provides a clearer, more detailed description.

In his 1710 letter to Vallisneri, Bellini describes two types of airways: the pores, which are in the eggshell, and a series of “channels” that are formed between the egg and shell membranes. The original description of the “airways” appeared in Bellini’s book Opuscula aliquot de urinis, de motu cordis, de motu bilis, de missione sanguinis (Bellini Citation1695, pp. 46–60). He says that these airways run from the pointed end of the egg to the blunt end, and that the channels are darker than the membranes and can be easily distinguished. To do so, first the egg should be cut into two parts along a section passing through the egg’s two ends. The shell should be allowed to dry a little and then the pores in the eggshell can be observed as Vallisneri also described. Upon illuminating the inside of the shell, directly or through the shell, according to Bellini the channels should also become visible. Bellini suggests separating the membranes from the eggshell by pulling the membrane from the blunt end to the pointed end of the egg. Then the membranes can be observed using both direct illumination (the light is between the eye and the membrane) and indirect illumination (the membrane is between the light and the eye). In the first case the channels appear to be dark, and in the second case they are translucent, like the airways in plants. He says that it seems to be clear that the airways (and the air itself) run lengthways from the pointed end to the blunt end of the egg. Bellini also says that these channels communicate with the eggshell pores, which are distributed all over the shell, but the air goes only from the pointed end to the blunt end (Vallisneri Citation1710).

Bellini implies that the notion of “airways” in birds’ eggs was inspired by Malpighi’s discovery of the existence of “airways” in the seeds of plants and the notion that the early development of plants was dependent on air. Bellini apparently assumed that like plants, the avian embryo required air too – as indeed it does. However, there is no evidence that that the longitudinal lines seen by Bellini, Vallisneri and Zinanni are airways per se.

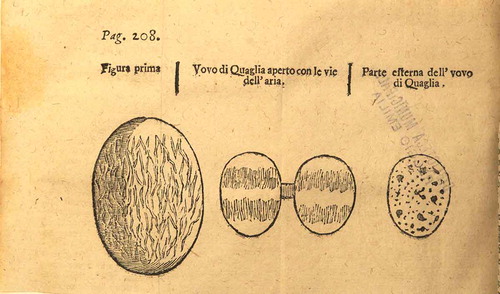

While not discounting the idea that the striations inside the egg are airways, Vallisneri (Citation1710) says that he was unable to confirm Bellini’s observation that the “airways” start at the pores in the eggshell, although he accepts that they pass quite close to them. Some other observations by Vallisneri (Citation1710) are relevant. For example, he states that the pattern of “airways” differs between species that he has examined (chicken, goose, duck, quail and corncrake), and that their distribution differs in different regions of the egg, being more obvious towards the poles of the egg. He also comments that the “airways” are apparent only on the outer (i.e. the shell-) membrane. Finally, Vallisneri (Citation1710) confirms that the airways are difficult to see in freshly laid eggs but become more apparent with time. Our observations (unpublished) confirm Vallineri’s concerning interspecific differences, regional differences within eggs and striations being confined to the outer (shell-) membrane ().

Figure 6. Original illustration of the egg airways from Antonio Vallisneri (Citation1710) Prima Raccolta d’Osservationi, e d’Esperienze del Signor Antonio Vallisnieri de’ Nobili di Vallisniera, Pubblico Professore di Medicina Teorica di Padoa ec. Cavata dalla Galeria di Minerva. Girolamo Albrizzi, Venezia (courtesy of Biblioteca Panizzi, Reggio Emilia, Italy, all rights reserved) (left: chicken egg airways; centre: quail egg airways; right: quail egg).

Remarkably, the striations in egg membranes have not, as far as we can tell, been commented on by other biologists. Neither William Harvey (see Whitteridge Citation1981) nor Romanoff and Romanoff (Citation1949) in their encyclopedic account of the avian egg mention them. And none of the poultry (egg) biologists one of us (TRB) consulted was aware of these striations.

In Vallisneri’s (Citation1733, p. 368) account, he states:

Since we started to talk about the Bellinian airways in the eggs, I think I have to explain more clearly how these airways can be found, as it was initially described by Bellini in his “De motu cordis; Propositione IX”, and later Bellini himself explained to me in a letter [6 March 1700], accompanied by a figure, that he sent me and that I have published in the Giornale de’ Letterati d’Italia [Citation1710], vol. 2, pp. 41–67 and to which I will refer. A chicken egg should be taken. The egg must not be fresh, because, as mentioned before, the air needs to have had time to enter the egg and distend the airways. The egg must be divided into two parts, leaving the membrane (“sottil pellicella” = thin skin/membrane [presumably the egg and shell membrane together]) that is internally, while the albumen and the yolk can be discarded. The eggshell is then held with the hand closed all around the margin of the egg (to form a sort of tube with the fingers bent against the thumb, with the egg closing the distal end of the tube). Then one eye is applied to the opposite end of the “tube” and the shell is observed in the darkness against a light source (in a room with closed windows and the light of a candle). When this is done, it will be possible to see very clearly the air ways, their position and size, as they can be seen in the figure that Bellini sent to me, or in the collection done by Albrizzi [a printer in Venice], although the quality of the wood print was very low [see ].

It seems easy now that the method has been discovered, but before Bellini showed me how to see these airways, I tried several different preparations that all failed: leaving the egg in vinegar, liquor, either cooking or not, it was impossible to observe the air ways, because the more the egg is moved from its original status, the more its structures are altered and eventually hidden.

Another way to see the air pores [in the shell] is to take a non-fresh egg, put it in glass of water, which is then put inside a pneumatic vacuum machine. Once the air is taken out from the machine, the air will start first to leave the water. If one continues to extract the air, that inside the egg will start to come out, in the form of fine lines of bubbles coming out from the eggshell. … In order to be sure that the air is coming from the egg and not from the water, air extraction can be first done on the water alone, and subsequently the egg is added to the water and the operation repeated. [Vallisneri is referring here to the vacuum pump invented in the 1650s, and refined by Robert Boyle (West Citation2005).]

Structure of Zinanni’s book: introduction part 2

The second part of the “Introduction” comprises a discussion of Zinanni’s taxonomic criteria for birds, which he compares with those of Aldrovandi (Citation1599–Citation1603) and Jonston (Citation1657). Zinanni says it is necessary to divide the birds and eggs into classes and then into orders to facilitate readers’ understanding. The divisions used by his predecessors are, Zinanni says, no doubt laudable, but he thinks his classification, based on the interest (litt. in Italian “affezione”) that birds have for common persons, is easier to remember.

Zinanni’s classification is not based on eggs or nests, but on three major “classes”: (i) terrestrial birds (non-raptors); (ii) raptors, and (iii) aquatic birds. Within each class there are several orders, based mainly on the utility of each species such as their palatability (e.g. non-raptors), or whether they can be used for hunting (i.e. used in falconry, or used as lures to attract other birds, such as owls). Zinanni uses the Italian phrase “delizia delle mense” (meaning literally “delight of the table”) when referring to certain birds, which we interpret as birds considered a gastronomic delicacy, and refer to here for simplicity as “delicious”.

In the first class (terrestrial birds – non-raptors) he identifies nine orders: (1) birds that are delicious and that amuse the eye (e.g. peacock, Indian cock, pheasant, grouses, etc.); (2) birds that are only delicious (e.g. corn crake, quail, ortolan bunting); (3) birds that are eaten but are not considered a delicacy (e.g. swallows, wagtails); (4) birds that are delicious and amuse the ear with their song (e.g. nightingale, skylark); (5) birds that amuse both the eye and the ear (e.g. goldfinch, bullfinch); (6) birds that amuse only the ears (e.g. canary finch, linnet); (7) birds that are garrulous (e.g. magpie, jay); (8) garrulous birds that can be eaten but are not delicious (e.g. roller Coracias garrulus; starling Sturnus vulgaris); and (9) birds that are not attractive in any sense (e.g. rook, carrion crow, house sparrow, woodpeckers). In other words, Zinnani uses four categories to rank birds according to their palatability, birds that are: (1) a delight for the table; (2) admitted to the table but are not a delicacy like swallows (“[uccelli] che sono ammessi nelle mense, ma che non servono per delizia, come le Rondini, i Codatremoli, ecc.”, p. 21); (3) not very good as food, but whose value is to delight the eye of the observer, like cranes, white storks, spoonbills (“[uccelli] che poco sono buoni a mangiarsi ma il loro pregio è il dilettar l’occhio de’ riguardanti”, p. 23); and (4) are not edible (“[uccelli che non sono] buoni ad essere mangiati”, p. 23).

The second class (terrestrial raptors) Zinanni divides into seven orders: (1) uncommon raptors, such as the eagles, and other raptors that are of no use for human purposes (e.g. kites and buzzards); (2) raptors that are used by hunters to capture other birds, such as for example vultures [sic – possibly an error by Zinanni], goshawk Accipiter gentilis, falcons; (3) raptors that can be eaten, although they are not delicious (e.g. shrikes); (4) vociferous raptors (parrots); (5) nocturnal raptors that are edible but not delicious (e.g. nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus); (6) nocturnal raptors that are used by hunters to lure other birds, and that are considered to bring bad luck because of their song (e.g. little owl Athene noctua, long-eared owl Asio otus); (7) all the other nocturnal raptors that have no specific characters apart from the fact that simple-minded, uneducated people think that they are sign of bad luck because of their calls (e.g. tawny owl Strix aluco, scops owls Otus scops).

The third class comprises aquatic birds, and is divided into four orders, birds that are: (1) delicious (e.g. woodcock Scolopax rusticola, snipe Gallinago gallinago and plovers); (2) eaten but are not delicious (e.g. geese, ducks, mergansers); (3) very poor for the table, but amuse the eye (e.g. crane Grus grus, storks, presumably both white stork Ciconia ciconia and black stork C. nigra, spoonbill Platalea leucorodia); and (4) are inedible and do not provide any amusement to the ear or the eye, and that have no commercial value (e.g. gulls, knots Calidris tenuirostris and possibly other small waders, cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo, kingfisher Alcedo atthis). Zinanni states that although the kingfisher is considered a terrestrial bird by Willughby, he agrees with Aldrovandi that it should considered an aquatic bird, because it is always found in the vicinity of water.

Part 2 of Delle Uova e dei Nidi

The second part comprises accounts of 109 birds. Not all of these are separate species; for example, Zinanni includes three varieties of domestic fowl (with one egg plate for each of the three). He also includes two species of buzzard, referring apparently to two different species, one described by Aldrovandi (p. 368) and one by Willughby (Ray Citation1676, p. 35, plate V). It seems unlikely that Zinanni refers here to the common buzzard Buteo buteo and the European honey-buzzard Pernis apivorous. As shown elsewhere, there was considerable confusion in the identification of these two species, exacerbated by their physical similarity and the plumage variability in the common buzzard. While Willughby and Ray did make the distinction and were the first recognise the honey-buzzard as a distinct species (Birkhead et al. Citation2018), neither of the two descriptions of buzzard species in Zinanni seems to refer to the honey-buzzard.

For each “species” Zinanni gives the Italian and Latin name, and references to the illustrations and descriptions in both Aldrovandi’s (Citation1599–Citation1603) and Willughby’s (Ray Citation1676) books, which he says can be used by the readers for identification. A brief description of the species is given, along with number of the table where the egg is illustrated and the number of the egg figure within the table. Zinanni then describes for each species the “generation” (time of the year when the bird breeds, the number of broods per year, clutch size), the “nest” and the “egg” itself.

At the end of the book Zinanni provides an index of the birds, eggs and nests described in the book. The index contains only 104 names, so Zinanni may have missed a few. The index is in alphabetical order and gives the page where the species is described and the plate in which the egg is illustrated. A second index, also in alphabetic order, provides the Latin names of the “species” he has described together with the reference to either Aldrovandi (Citation1599–Citation1603) or Willughby (i.e. Ray Citation1676) and the plate number where the bird is illustrated in Aldrovandi (Citation1599–Citation1603) and Ray (Citation1676). A list of species whose eggs and nest are described by Zinanni is given in .

Table I. List of species in Zinanni’s book. The first column refers to the number and name in Zinanni’s egg plates. The second and the third columns refer to the species name and the page in Ray’s Ornithologiae (Orn.) and in Aldrovandi's books, respectively. The fourth column contains the modern species names (where different from those in the Ornithologiae) and notes to the identification. Our identification is from matching names in Zinanni’s text and the English edition of Willughby’s Ornithology (Ray Citation1678). Note that the text on plates in Zinanni (Citation1737) does not always agree with text in the main body of the book.

Klein’s Ova avium plurimarum ad naturalem magnitudinem delineate et genuinis coloribus picta (Citation1766)

Jacob Theodor Klein (1685–1759) was born in Königsberg (now Kaliningrad, Russia). He studied natural history and was elected to the Royal Society in 1759. He published several natural history books and, taking advantage of his position as secretary to the city of Gdansk, in 1718 founded there a botanical garden that was later expanded to include his large collections of animals, plants and fossils.

The text of Klein’s book is presented in two columns, one in Latin and the other in German. Starting with a “Praefatio” (Forward), Klein comments on some of the previously published books on bird eggs: both Pliny and Aldrovandi, he says, made many mistakes, but Willughby and Ray and both Marsili and Zinanni were more careful. Klein describes Zinnani’s illustrations as “high quality”, but being in black and white, he says, required verbal descriptions of the colours, which although necessary were unsatisfactory. Finally in this section, Klein describes how he was able to access egg collections from which he created the 21 colour plates illustrating the eggs of around 140 different species of birds, that enrich his book (p. 7). He thanks (p. 8) René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur (1683–1757), the French naturalist who devised processes for preserving birds and eggs. Thanks to Reaumur’s method of preserving eggs, Klein was able to obtain eggs from any part of the world (although most of the species presented in his book are actually European).

Klein based his paintings on preserved eggs from several collections made by Helvingius (Hamburg), Friedrich Samuel Bock (1716–1785, University of Königsberg), arranged according to his own classification system based mainly on birds’ feet and toes (see Stresemann Citation1975).

For some of the species, Klein provides a brief description of the typical habitat, a description of the nest position and structure, and the colour and structure of the eggs, but provides no information on either clutch size or breeding season.

Klein provides images of three eggs of the domestic fowl (Gallus domesticus, pp. 31–32, table XIII, n. 1–3). The first is a typical egg, but Klein says it is well known that they can vary considerably in size and that “sometimes an egg within egg can be found”. The second is an unusually shaped egg laid during the solar eclipse that occurred on 25 July 1748, and originally given to the King of Sardinia (Carlo Emanuele III). The third is a monster egg, very similar to those described by Aldrovandi (original illustrations, vol. 3, p. 155, http://aldrovandi.dfc.unibo.it/pinakesweb/main.asp?language=it).

As well as describing and illustrating more species (including tetraonids and the black stork) than Zinanni – some 140 in total – Klein’s main contribution to oology is in providing the first colour illustrations of eggs. Colour printing was just beginning in the mid-eighteenth century (Peddie Citation1914), but Klein’s images, which Anker (Citation1938) refers to as “crude” (as indeed they are), were hand-coloured metal engravings (engraved by Gust. Phil. Trautner, as indicated on the first plate).

Discussion

The accounts of birds’ eggs and nests by Marsili, Zinanni and Klein have not been widely cited, and were not, for example, mentioned in the wide-ranging and scholarly reviews of eggs and the history of ornithology by Romanoff and Romanoff (Citation1949), Schönwetter (Citation1960–1992) or Stresemann (Citation1975). One possible reason why these books were not cited by these authors, even as the first examples of oological books, is because they were numerically, biologically and geographically limited in their scope. Marsili, for example, describes the eggs and nests of just 15 aquatic birds whose identifications are in some cases uncertain. Zinanni describes more birds (106), mainly those occurring in north-east Italy. Even so, he decided at the outset to limit himself to around 100 species (letter from Zinanni to Bianchi dated 4 June 1735; see Antonio Montanari http://digilander.libero.it/monari/spec/ginanni.681.html). Klein illustrates around 140 species of birds’ eggs, again mainly local birds, but his text is less comprehensive than Zinanni’s.

A further issue, certainly in Zinanni’s and Klein’s case, that might have reduced their success in the eyes of subsequent ornithologists is that even though they used the “authority” of Aldrovandi (Citation1599–Citation1603) and Willughby (i.e. Ray Citation1676) to verify their identifications, they added confusion rather than clarity by introducing their own classificatory criteria (e.g. Zinanni’s ideas of whether birds taste “delicious” or not), devaluing their own scientific credibility. Moreover, by supplementing Willughby and Ray’s classification they probably alienated subsequent authors, almost all of whom recognised the outstanding practicality of the Willughby and Ray classificatory system. Finally, compared with Willughby and Ray, in terms of their ornithological knowledge and the care they took with their studies, the efforts of Marsili, Zinanni and Klein seem rather amateurish.

More positively, these three books were pioneering in that they were the first to recognise that birds’ nests and eggs were worthy of attention for their own sake. It would have been interesting to establish what, other than increasing curiosity about the natural world, inspired these to authors to focus on nests and eggs.

A few other authors from this time provided written descriptions of birds’ eggs, including Caspar Schwenckfeld (Citation1603) who described the nests, eggs and clutch size of some 150 birds in his regional avifauna Theriotropheum Silesiae (Stresemann Citation1975). Ray (Citation1676, Citation1678) included descriptions of the eggs of some species. Eleazar Albin’s three-volume A Natural History of Birds (Citation1731–1738) contained the first coloured illustrations of native and non-native British birds, but no images of their eggs. However, his more modest A Natural History of English Song-Birds, published in 1737, contained black-and-white illustrations of 20 native species (and the canary Serinus canaria and northern cardinal Cardinalis cardinalis) commonly kept in captivity, 18 of which are accompanied by an image (and a written description) of their egg. The species whose eggs were not illustrated were the northern cardinal Cardinalis cardinalis (a North American species, popular as a cage bird, imported into Europe), lesser redpoll Acanthis cabaret (whose nest he had presumably failed to find), and the Eurasian siskin Spinus spinus, whose nest was notoriously difficult to find (see Feldner Citation2002).

In 1742 and 1743 Johann Heinrich Zorn produced a two-volume work, Petino-Theologie, on birds that contains descriptions (but no illustrations) of the nests and eggs of around 140 bird species from the Pappenheim (near Nuremberg) area of Germany. Zorn was a self-educated but perceptive observer, commenting, for example, that the reason hole-nesting birds produce white eggs is so that (thanks to the Wise Provider) the parents can see them in the dark (Nitze Citation2000). Zorn (Citation1742–1743) mentions Zinanni’s book, but as Nitze (Citation2001) has pointed out, it seems unlikely he ever saw it for himself. However, Zorn’s collection of nests and eggs appeared to be the basis, in part, for a four-volume book by Frederick Christian Günther published between 1722–1786, comprising descriptions and large coloured plates of nests and eggs (see Nitze Citation2001). The illustrations, engraved by Adam Ludwig Wirsing, are highly stylised, with both the eggs and nest material heavily delineated, in what some might consider an unaesthetic manner.

Of the three books discussed here, Zinanni’s is the most interesting from both a biological and a historical perspective. His scholarship seems to have been greater than Marsili’s, at least in relation to birds’ eggs, referring to the works of Harvey, Fabricius and Malpighi, and his discussion of Bellini’s and Vallineri’s observation of the “airways” in eggs indicates a deep curiosity. Oddly perhaps, one of the more interesting aspects of Zinanni’s book is what his classification system tells us about attitudes towards birds in Italy in the mid-eighteenth century. As Willughby and Ray became aware during their time in Italy in 1663–1664, Italians killed and ate birds in prodigious quantities, and routinely consumed some species that were not eaten in England (Birkhead et al. Citation2016; Birkhead Citation2018). Zinanni’s “classification” based on the usefulness of different birds provides us with a clear indication of both their gustatory value and their value as songbirds. The cultural significance of bird catching, bird keeping and the eating of birds in Italy is apparent from numerous books (e.g. Manzini Citation1575; Valli da Todi Citation1601; Olina Citation1622), but also from references to bird catching in theatre, such as that by the playwright Carlo Goldoni (1707–1793) and the composer Niccolo Jommelli’s (1714–1774) opera “L’uccellatrice” (The fowler lady) (Goldoni Citation1772).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Marie Attard, Ann Datta, Josef Feldner, Duncan Jackson, Tom Pizzari, Douglas Russell (curator of eggs at the Natural History Museum, Tring, UK), Karl Schulze-Hagen, Rolf Schlenker and Ann Sylph (Zoological Society for London), and to an anonymous referee, for useful comments. We are also very grateful to Giancarlo Fracasso, who kindly reviewed our list of the birds in Zinanni’s book. We thank the following poultry researchers for their comments: P. Hocking, Y. Nys and N. Sparks. We thank Harry Taylor and the Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London, for permission to use the images from Zinanni’s book, the Royal Society of London for the images from Marsili’s book and Chiara Panizzi of the Panizzi Library of Reggio Emilia, Italy, for permission to use the image from Vallisneri’s (Citation1710) book.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Albin E. 1731–1738. A natural history of birds (3 vol.). London: William Innys.

- Aldrovandi U. 1599. Ornithologiae hoc est de avibus historiae libri XII. Bologna: Giovan Battista Bellagamba. p. 982.

- Aldrovandi U. 1600. Ornithologiae tomus alter cum indice copiosissimo variarum linguarum. Bologna: Giovan Battista Bellagamba. p. 862.

- Aldrovandi U. 1603. Ornithologiae tomus tertius ac postremus. Bologna: Giovan Battista Bellagamba. p. 560.

- Anker J. 1938. Bird books and bird art, an outline of the literary history and iconography of descriptive ornithology. Copenhagen: Levin and Munksgaard. p. 251.

- Bellini L. 1695. Opuscula aliquot, ad Archibaldum Pitcarnium, professorem Lugduno-Batavum. Pistoia: Stefano Gatto. p. 261.

- Bellini L. 1710. Lettera intorno alle vie dell’aria nell’uovo. Giornale de’ Letterati d’Italia 2:41–71.

- Belon P. 1555. L’Histoire de la Nature des Oyseaux. Paris: Gilles Corrozet.

- Birkhead TR. 2017. The most perfect thing: Inside (and outside) a bird’s egg. London: Bloomsbury. p. 304.

- Birkhead TR. 2018. The wonderful Mr Willughby: The first true ornithologist. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 368.

- Birkhead TR, Charmantier I, Smith PJ, Montgomerie R. 2018. Willughby’s Buzzard: Names and misnomers of the European Honey-buzzard (Pernis apivorus). Archives of Natural History 45:80–91.

- Birkhead TR, Smith P, Doherty M, Charmantier I. 2016. Willughby’s Ornithology. In: Birkhead TR, editor. Virtuoso by nature: the scientific worlds of Francis Willughby FRS (1635–1672). Leiden: Brill. pp. 268–304.

- Bonanni F. 1681. Ricreatione dell’occhio e della mente nell’osseruation’ delle chiocciole. Roma: Varese. p. 384.

- Cassey P, Maurer G, Lovell PG, Hanley D. 2011. Conspicuous eggs and colourful hypotheses: Testing the role of multiple influences on avian eggshell appearance. Avian Biology Research 4:185–195.

- Fabricius ab Aquapendente H. 1621. De Formatione ovi et pulli tractatus. Padua: Aloysius Bencius.

- Feldner J. 2002. Benediktinerpater Leopold Vogl – Ein früher Verhaltensforscher im ausgehenden 18 Jahrhundert. Vogelkundliche Nachrichten aus Oberösterreich, Naturschutz aktuell 10:3–13.

- Fluck H-R, Scharbach A. 2016. Leonhard Baldner – Zu seinem Testament und Nachlassverzeichnis. Revue d’Alsace 142:283–297.

- Gessner K. 1555. Historia Animalium. Frankfurt: Froschauer.

- Goldoni C. 1772. L’ uccellatrice intermezzo a due voci. Lucca: Filippo Maria Benedini. p. 21.

- Harvey W. 1651. Exercitationes de generatione animalium. London: Typis Du-Gardianis; Impensis O. Pulleyn. p. 350.

- Jonston J. 1657. Historiae naturalis de avibus libri VI. Amsterdam: J. J. Schipperi.

- Klein JT. 1766. Ova avium plurimarum ad naturalem magnitudinem delineata et genuinis coloribus picta. Leipzig: Johann Jacob Kanter. p. 36.

- Lauterborn R. 1903. Leonhard Baldner: vogel—, Fisch‐ und Thierbuch, 1666. Handschrift Ms20 phys. et hist. nat. 3 der Murhardschen Bibliothek der Stadt Kassel und Landesbibliothek. Faksimileausgabe mit über 130 ganzseitigen Aquarellen, rd. 400 Seiten in 2 Bänden. Mit zwei Beiheften: einführung von Robert Lauterborn (63 S.) und Erläuterungen zu den Tafeln von Robert Lauterborn, Horst Janus und Claus König (40 S.). Stuttgart: Verlag Müller und Schindler.

- Malpighi M. 1673. Dissertatio epistolica de formatione pulli in ovo. London: Joannem Martyn.

- Manzini C. 1575. Ammaestramenti per allevare, pascere et curare gli uccelli. Milano: Pacifico Pontio. p. 58.

- Marsigli LF. 1726. Danubius Pannonico-Mysicus: de avibus circa aquas Danubii vagantibus, et de ipsarum nidis, Volume 5. Amsterdam: Gosse, Alberts, de Hondt. p. 154.

- Montanari A. 2002. L’ Accademia dei Lincei riminesi 1745: breve storia con in appendice una biografia del suo Restitutore Giovanni Bianchi (Iano Planco, 1693-1775). Rimini, privately published. p. 40.

- Newton A. 1896. A dictionary of birds. Black: London.

- Nitze W. 2000. Nachlese zu Johann Heinrich Zorn (1698–1748) sowie zur Entdeckung des Weißenburger Malers von Vogel-, Nester-und Eierzeichnungen Georg Thomas Tröltsch (1709–1748). Rudolstädter nat hist Schriften 10:117–131.

- Nitze W. 2001. The creation of the 18th-century oological work ‘Sammlung von Nestern und Eyern verschiedener Vögel’ [A collection of nests and eggs of various birds] by Friederich Christian Günther (1726-1774). Anzeiger des Vereins Thüringer Ornithologen 4:189–210.

- Olina GP. 1622. Uccelliera. Roma: Andrea Fei. p. 340.

- Ongaro G 2000. Giuseppe Ginanni. Treccani: Dizionario biografico degli italiani 55: 5–7. Available: http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giuseppe-ginanni_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed Nov 2018 8.

- Peddie RA. 1914. The history of colour printing. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 62:261–270.

- Ray J. 1676. Ornithologiae libri tres: in quibus aves omnes hactenus cognitae in methodum naturis suis convenientem redactae accuratè descripbuntur, descriptiones iconibus. London: John Martyn.

- Ray J. 1678. The Ornithology of Francis Willughby. London: John Martyn.

- Ray J. 1686. Historia Piscium. London: Royal Society.

- Romanoff AL, Romanoff AJ. 1949. The avian egg. New York: John Wiley.

- Schembri A. 1846. Vocabolario dei sinonimi classici dell’Ornitologia Europea. Bologna: Sassi Nelle Spaderie. p. 437.

- Schönwetter M. 1960–1992. Handbuch der Oologie. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

- Schwenckfeld C. 1603. Therio-Tropheum Silesiae: in quo animalium, hoc est quadrupedum, reptilium, avium, piscium, insectorum natura, vis et usus sex libris perstringuntur. Lignicii: Albert.

- Stoye J. 1994. Marsigli’s Europe 1680-1730: The Life and Times of Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli, Soldier and Virtuoso. Yale: Yale University Press. p. 368.

- Stresemann I. 1975. Ornithology from Aristotle to the present. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Thompson DAW. 1917. On growth and form. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 793.

- Valli da Todi A. 1601. In canto de gl’augelli. Roma: Nicolò Mutij.

- Vallisneri A. 1710. Prima raccolta d’osservationi, e d’esperienze del signor Antonio Vallisnieri de’ Nobili di Vallisniera, pubblico professore di Medicina Teorica di Padoa ec. Cavata dalla Galeria di Minerva. Consacrata al Molto Illustre Sig. Dottor Giacomo Giacomoni. Venezia: Girolamo Albrizzi.

- Vallisneri A. 1733. Opere fisico-mediche stampate e manoscritte del kavalier Antonio Vallisneri, raccolte da Antonio suo figliolo 3 vol. Venezia: Sebastiano Coleti.

- West JB. 2005. Robert Boyle’s landmark book of 1660 with the first experiments on rarified air. Journal of Applied Physiology 98:31–39.

- Whitteridge G. 1981. Disputations touching the generation of animals. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Wirsing AL. 1772. Sammlung von Nestern und Eyern verschiedener Vogel. Nürnberg: Campe.

- Wood CA. 1931. An introduction to the literature of vertebrate zoology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zinanni F. 1762. Produzioni naturali che si ritrovano nel museo Ginanni in Ravenna, metodicamente disposte, e con annotazioni illustrate. Lucca: Giuseppe Rocchi. p. 259.

- Zinanni G. 1737. Delle uova e dei nidi degli Uccelli. Venezia: Antonio Bortoli. pp. 130+55.

- Zorn JH. 1742–1743. Petino-Theologie oder Versuch, Die Menschen durch nähere Betrachtung Der Vögel Zur Bewunderung, Liebe und Verehrung ihres mächtigsten, weissest- und gütigsten Schöpffers aufzumuntern (2 vol.). Pappenheim: Rau.