Abstract

The original description of the fan worm Parasabella fullo (Grube, 1878) is brief and mainly focused on the color. This paper provides a redescription based on syntype material from northern Japan kept at Museum für Naturkunde of Berlin and new records in California (USA). Diagnostic characters used in redescribing the species are the shapes of inferior thoracic notochaetae, ventral thoracic shields and dorsal collar margins. Although this Japanese species was collected on vessels’ hulls in California, it is not clear if and where the species is established here, due to past difficulties in identification without well-defined characters. Nevertheless, a resident population appears to exist in the region, given the species occurrence on local recreational vessels. The redescription provides information to distinguish it from the local Californian indigenous species Parasabella pallida Moore, 1923.

Introduction

In a recent taxonomic analysis of invertebrates collected from the hulls of vessels in California, USA, the western Pacific polychaete Parasabella fullo (Grube, Citation1878) was identified by L. H. Harris (Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, Allan Hancock Foundation), representing a first record for the state, and reported by Ashton et al. (Citation2012). Although distinct from the California native Parasabella pallida Moore, Citation1923, these congeners are challenging to distinguish from each other based on existing descriptions.

Parasabella fullo was originally described from northern Japan, but drawings or diagnostic features were not included by Grube (Citation1878). Zachs (Citation1933) also reported Sabella fullo from northern Japan, suggesting it belonged to the genus Demonax Kinberg, Citation1867. Zachs (Citation1933) also suggested the species was possibly synonymous with D. leucaspinus (sic) (Kinberg Citation1867), a species originally described from Peru, based on illustrations of thoracic and abdominal chaetae provided by Johansson (Citation1925: 24, fig. 8) for D. leucaspius (sic). Later, Annenkova (Citation1938), Uschakov (Citation1955) and Buzhinskaja (Citation1967) also reported S. fullo in the northwestern Pacific under D. leucaspius (sic), probably following Zachs (Citation1933). It is remarkable that S. fullo was not mentioned in any contributions by Johansson (Citation1922, Citation1925, Citation1927) on sabellid polychaetes for this region.

Tovar-Hernández and Harris (Citation2010) replaced the name Demonax with Parasabella and recognized 25 species in the genus Parasabella, but P. fullo was omitted. Subsequently, Buzhinskaja (Citation2013) placed S. fullo within Parasabella, although a diagnosis or redescription of the species was not included. To date, P. fullo is only known to have established populations in northern Japan and eastern Russia (Zachs Citation1933; Annenkova Citation1938; Uschakov Citation1955; Buzhinskaja Citation1967). Capa and Murray (Citation2015) considered P. fullo to be a valid taxon, and they highlighted the translocation of some species of Parasabella beyond their natural distribution. Notwithstanding the foregoing work, a full redescription and illustrations are still needed to properly identify and detect P. fullo, especially outside of its native range where other congeners occur.

This study examines and characterizes the syntypes of P. fullo, providing a formal redescription. We also examine records of P. fullo and P. pallida in California, stressing the main characters to discriminate indigenous from non-indigenous species of Parasabella along the northeastern Pacific.

Material and methods

Syntype material of Parasabella fullo (Grube, Citation1878) from Museum für Naturkunde Leibniz in Berlin (Germany) (ZMB-5731) and syntypes of P. japonica (Moore & Bush, Citation1904) from the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA (ANSP 1082) were requested and examined. These were compared to specimens of P. fullo and P. pallida from California, deposited at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Invasion Lab (SERC). Only entire, complete syntypes of P. fullo were photographed.

The specimens from California were collected from three locations in previous studies (). In San Francisco Bay, fouling panels were deployed for 3 months during summer and retrieved in September 2016 for analysis of benthic invertebrates (see Bastida-Zavala et al. Citation2017 for description). In Santa Barbara Harbor and San Diego, the hulls of recreational vessels were surveyed and sampled by divers, to analyze associated benthic invertebrate species (Ashton et al. Citation2012). These two studies are referenced in this paper as the panel and vessel surveys, respectively.

Taxonomic accounts

Systematics

Order SABELLIDA Latreille, Citation1825Family SABELLIDAE Latreille, Citation1825Genus Parasabella Bush, Citation1905

Parasabella fullo (Grube, Citation1878), redescription–

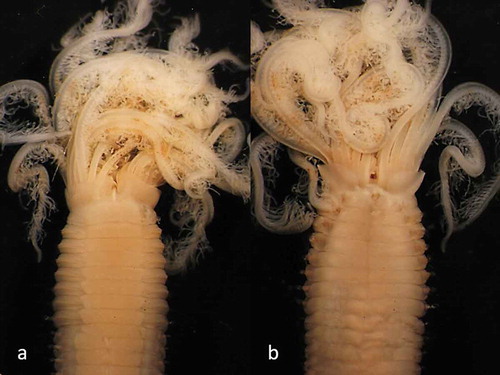

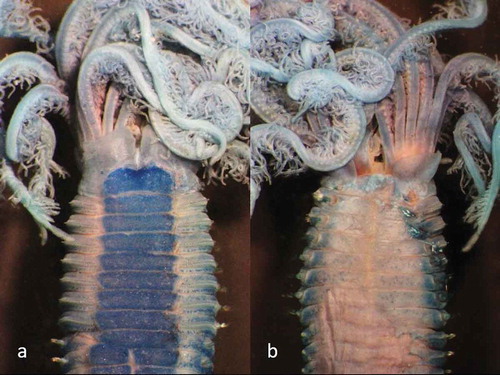

Figure 3. Parasabella fullo syntype ZMB 5731 stained with methyl green: (a) thoracic ventral view (b) thoracic dorsal view

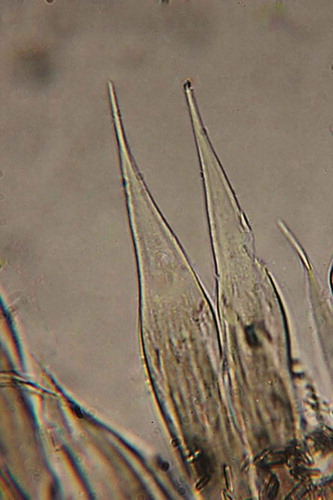

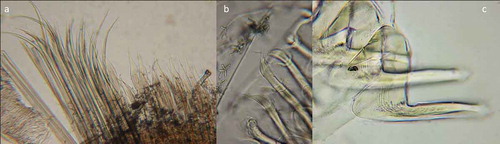

Figure 5. Parasabella fullo syntype ZMB 5731: (a) notopodial thoracic chaetae (b) neuropodial thoracic companion (c) thoracic uncini

Sabella fullo Grube, Citation1878: 105.

?Demonax fullo. — Zachs Citation1933: 134. — Buzhinskaja Citation1985: 188, Figure 22.

Demonax leucaspius (sic). — Annenkova Citation1938: 213–214 (non D. leucaspis (Kinberg)).

Demonax (sic) leucaspius. — Uschakov Citation1955: 412, Figure 156 J–I. — Buzhinskaja Citation1967: 115–116 (non D. leucaspius Kinberg).

Parasabella fullo. — Buzhinskaja Citation2013: 12. — Capa & Murray Citation2015: 768, figures 4–C, 5–O.

Examined material

Parasabella fullo (Grube, Citation1878), ZMB 5731, five complete syntypes (three entire, two broken in two parts under histolysis) and one detached crown plus one specimen of Bispira spirobranchia (Zachs, Citation1933). Parasabella fullo (Grube, Citation1878), recreational boats’ project: California, USA. SERC: 2 specimens from the 2011 vessel survey previously identified by Leslie Harris and deposited in Invasion Lab at SERC collection (Maryland). Vial # 147893 (1 specimen): collected on 13 July 2011 from a recreational boat hull berthed (visiting) in Santa Barbara Harbor (34°24ʹ21.38”N, 119°41ʹ33”W). Vial # 162979 (1 specimen) collected on 25 October 2011 from recreational boat hull berthed (visiting) in San Diego Police Dock (32° 42ʹ 35” N, 117° 14ʹ 03” W).

Additional material examined

Parasabella japonica (Moore & Bush, Citation1904), syntype, ANSP 1082.

Diagnosis

Radiolar eyes absent. Broad radiolar flanges along radioles. Radiolar tips medium-length (the length of two thoracic segments), digitiform. Dorsal lips broad basally, with radiolar appendages (mid-rib) and a long filament, which is longer than dorsal lips lateral lamellae length. Dorsal collar margins long, flap-like. Thoracic ventral shields in contact with neuropodial tori. Inferior thoracic notochaetae broadly hooded with progressively tapered tips (type Aaccording to Capa & Murray Citation2015).

Redescription of syntypes and Californian specimens (SERC)

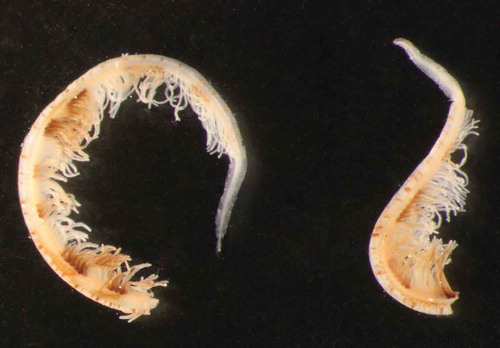

Min-Max body length 18–58 mm (syntypes), 16–37 mm (SERC). Min-Max body width 2–4.5 (syntypes), 2.3–3 mm (SERC). Min-Max radiolar crown length 4.5–14 mm (syntypes), 5.5–8 mm (SERC). Pairs of radioles: 12–26 (syntypes), 13–19 pairs (SERC). Thorax with eight segments (syntypes, SERC). Abdomen with 67–108 segments (syntypes), 52–84 (SERC). Radiolar crown with basal lobes as long as 1.5–2 thoracic segments, arranged in two semicircles, involute ventrally in largest syntype and specimens from recreational boat in California (, and ). Radioles spotted in Californian specimens (); although not seen in preserved syntypes but present at least at the base of the radioles and mentioned in original description, this feature may have been diminished due to preservation (). Radiolar tips bare, digitiform, as long as the length of two thoracic segments, with broad flanges (). Broad radiolar flanges present along the entire radiolar length. Number of skeletal cells were not counted but more than 30 were reported by Capa and Murray (Citation2015). Dorsal lips as long as 5–6 thoracic segments, broad basally, with radiolar appendages (mid-rib) tapered distally. The tip projection of the radiolar appendages is longer than the lateral lamellae length of the dorsal lip. One or two pairs of short pinnular appendages attached on the first two dorsal radioles. Ventral lips rounded, slightly folded and short. Parallel lamellae prominent, arising from the anterior margin of collar ventral shield, and covering the entire margin of ventral peristomium. Brown spots, unequal in size along radiolar rachis (fade off in some syntypes). Collar as long as three thoracic segments in dorsal view (from the anterior margin of collar to the first intersegmental division), covering the base of radioles. Low ventral lappets with rounded anterior margins, separated completely by a long incision () and )). Dorsal collar margins not fused to faecal groove () and )), flap-like. Ventral shield of collar incised median-anteriorly by a small notch ()), from where lamellae arise. Collar chaetae elongate, narrowly hooded. Thoracic ventral shields similar in size, two times wider than long, in contact and indented by adjacent neuropodial tori () and )). Brown spots located between thoracic neurochaetal tori and notochaeta. Superior thoracic notochaetae elongate, narrowly hooded ()); inferior group with two rows of shorter, broadly hooded chaetae of type B ()), with hoods 1.5–2 times width of the shaft (A/B), and 3–4 times as long as maximum width (C/B) (). Thoracic neuropodial uncini with about seven to nine rows of similar-sized teeth above main fang, covering half the length of main fang, neck shorter than breast or as long as breast (E/F), well-developed breast and long handles (2.5–3 times the distance from main fang to breast) (H/G) ()). Thoracic neuropodial companion chaetae with subdistal end enlarged, and thin distal mucro compressed laterally ()). Abdominal chaetae narrowly hooded in both anterior and posterior rows, uncini with 7 to 10 rows of similar-sized teeth above main fang covering about half the length of main fang, breast well-developed and medium-size handle (1–1.5 times the length of the distance between breast and main fang). Pygidium forming a rounded lobe with approximately 25 black eyespots, all unequal in size in California records (eyespots not seen in syntypes, perhaps they faded off).

Distribution

Northern Japan, Eastern Sea of Russia, California (Ashton et al. Citation2012). Although detected in California, this species is not known to be established here (see Discussion), as it was found only on two vessels to date.

Remarks

Parasabella fullo was originally described as Sabella by Grube (Citation1878) from northern Japan. Unfortunately, drawings or diagnostic features were not included in his original description in German: “Weisslich mit roth-brauner Unterseite oder ganz blassbraun, jederseits 18 blass rothbraune Kiemenfäden, ihr Schaft mit 2 Längsreihen abwechselnd kreideweisser schmalen unregelmässigen bräunlichen Binden. Eine Basalmembran an den Kiemen nicht wahrnehmbar; letztere 7, der Leib 24 mm lang” that can be translated as: Whitish with a brownish-brown background, or entirely pale brown, 18 pale red-brown radioles on each side, with two longitudinal chalky-white narrow bands alternated by irregular brownish bandages. A basal membrane not visible on the crown; the latter 7 mm long, while the body is 24 mm.

In the contribution by Capa and Murray (Citation2015), a description of P. fullo is not provided, but they include some characters in their table 2: P. fullo do not present radiolar eyes; the thoracic ventral shields are in contact with the neuropodial tori; and type B inferior thoracic notochaetae (broadly hooded with progressively tapered tips). Also, they reported a drawing of numerous rows of axial cells supporting the radioles at their base (>30 cells, Fig. 4C in Capa and Murray (Citation2015)) and long-handled thoracic uncini (2.5 times the distance between the fang and the breast, Fig. 5O in Capa and Murray (Citation2015)).

The redescription, provided in the present study, in addition to the features proportioned by Capa and Murray (Citation2015), includes the presence of broad radiolar flanges along radioles; radiolar tips digitiform, of medium-length; dorsal lips broad basally, with radiolar appendages (mid-rib) and a long filament that it is longer than the lateral lamellae of dorsal lips; and dorsal collar margins flap-like.

In Japan, in addition to P. fullo, other three species of the genus have been described: P. aulaconota (von Marenzeller, Citation1884) from Nagasaki; P. albicans (Johansson, Citation1922) from Misaki among holfasts of the alga Laminaria; and P. japonica (Moore and Bush, Citation1904) from Suruga Bay. At the present, the co-occurrence of multiple Japanese species create challenges in individual species identification, because original descriptions are brief, illustrating only chaetae and uncini (except for P. albicans, where a collar in dorsal view was illustrated by Johansson Citation1922, pl. I, fig. 7). These and subsequent records do not include a comparison of morphological features useful for identification (e. g. Okuda Citation1938; Imajima & Hartman Citation1964; Uchida Citation1968). Capa and Murray (Citation2015) examined types of P. aulaconota and P. albicans and some features for both species were included in their table 2, and these are used below for comparative purposes with P. fullo, as well as the examination of the type of P. japonica (ANSP 1082 reviewed in the present study).

Parasabella aulaconota have 8–10 vacuolate cells of the cross-section radiole near the base, while more than 30 cells are present in P. fullo (Capa & Murray Citation2015). Parasabella albicans shows radioles with short tips, and the tips are medium-length in P. fullo. In P. japonica, ventral shields are not in contact with neuropodial tori, and those in P. fullo are in contact with neuropodial tori.

For the USA west coast, three different species of Parasabella have been described: P. pallida Moore, Citation1923 from Santa Cruz, California; P. media (Bush, Citation1905) from Alaska to Monterrey Bay; and P. rugosa (Moore, Citation1904) from San Diego, California. Types of P. rugosa were examined by Banse (Citation1979), and Perkins (Citation1984) provided redescriptions of all three species. These species were found from the intertidal to 140 m depth, in a variety of habitats: rocky crevices, shell and mud, in seagrass, associated with pilings, and on vessel hulls ().

Table I. Species of Parasabella described from California (USA)

For P. fullo and P. pallida, radiolar eyes are absent, the thoracic ventral shields are in contact with neuropodial tori, and both have thoracic chaetae type B (). However, these species also have some dissimilarities: the dorsal collar margins are longer in P. fullo than P. pallida (as long as three thoracic segments in the former, as long as two thoracic segments in the second); P. fullo have medium-size, digitiform radiolar tips with broad flanges, whereas P. pallida shows long-size, filiform tips with narrow flanges; in P. fullo radiolar appendage projection of dorsal lips is longer than dorsal lip lateral lamellae length compared to the projection of P. pallida that is shorter than the length of the dorsal lip lateral lamellae. Moreover, P. fullo has larger basal radiolar lobes than P. pallida (length of 1.5–2 thoracic segments in P. fullo versus one segment in P. pallida), and P. fullo has a higher number of radiolar cells than P. pallida (>30 versus 8–10 in P. pallida) ().

Table II. Comparison between Parasabella fullo (Grube, Citation1878) and P. pallida Moore, Citation1923

Parasabella pallida Moore, Citation1923

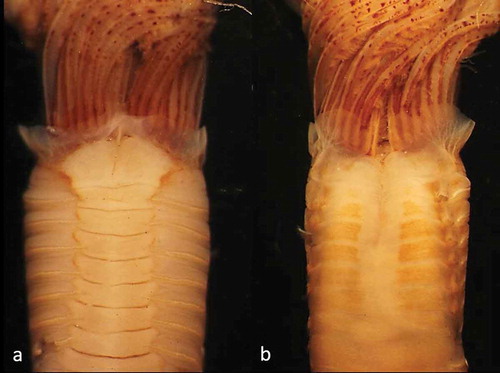

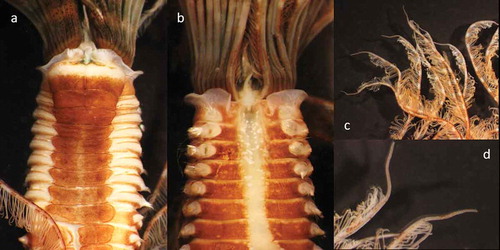

Figure 8. Parasabella pallida (SERC, Vial 239815) from San Francisco Bay: (a) thoracic ventral view; (b) thoracic dorsal view; (c) (d) tips of radioles

Parasabella pallida Moore Citation1923: 241, 242. — Loi Citation1980: 144. — Tovar-Hernández & Harris Citation2010: 15. — Bastida-Zavala et al. Citation2016: 407–408, figs 2 (map), 10D.

Sabella media. — Hartman, Citation1944: 285 [in part, not pl. 23, fig. 42] fide Perkins Citation1984.

Demonax medius. — Hartman, Citation1969: 675, 676 [in part, not figs 1–5] fide Perkins Citation1984.

Demonax pallidus. — Perkins Citation1984: 313–315, figs 15–16. — Tovar-Hernández et al. Citation2009: 325–326, figs 2b, f, 3c–d, 4c–e.

Examined material

Parasabella pallida Moore, Citation1923. San Francisco Bay, Ballina Island Marina collected on 13 September 2016: plate 18320: vial # 222933; plate 18229: vial # 222943; plate 17859b: vial # 239815; Lake Merritt Boat House collected on 16 September 2016: plate 18343: vial # 239817; plate 18192: vial # 239944. Deposited in Invasion Lab at SERC collection (Maryland).

Diagnosis

Radiolar eyes absent. Narrow radiolar flanges along radioles. Radiolar tips long-length (the length of three thoracic segments), mostly filiform. Dorsal lips broad basally, with radiolar appendage (mid-rib) and a filament that is shorter than dorsal lips lateral lamellae length. Dorsal collar margins short, flap-like. Thoracic ventral shields in contact with neuropodial tori. Inferior thoracic notochaetae broadly hooded with progressively tapered tips (type A according to Capa & Murray Citation2015).

Description of Californian specimens

Min-Max body length 28–33 mm. Body width 3.5 mm. Min-Max radiolar crown length 14–17 mm. Pairs of radioles: 22–24. Thorax with eight segments. Abdomen with 52–68 segments. Radiolar crown arranged in two semicircles, involute ventrally with basal lobes as long as one thoracic segment (longitudinal length). Radiolar tips bare, slender, and filiform as long as approximately three thoracic segments. Narrow radiolar flanges present along the entire radiolar length. Dorsal lips as long as five thoracic segments, broad basally with a radiolar appendage (mid-rib) that projects anteriorly as a filament. This filament is shorter than dorsal lip lateral lamellae length. Two-three pairs of short pinnular appendages attached on the first two dorsal radioles. Ventral lips rounded, and short. Parallel lamellae arising from the anterior margin of ventral shield of collar, and covering the entire margin of ventral peristomium. Crown with brown bands, each band extending over three pinnules; radiolar rachis with numerous brown-coloured spots, unequal in size, distributed irregularly along radiolar length. Collar as long as two thoracic segments in dorsal view (from the anterior margin of collar to the first intersegmental division), covering slightly the base of radioles. Low ventral lappets with rounded anterior margins; dorsal collar margins not fused to faecal groove, flap-like. Ventral shield of collar M-shaped, incised median-anteriorly by a small notch, from where a large parallel lamellae arises. Collar chaetae elongate, narrowly hooded. Thoracic ventral shields similar in size, two times wider than long, in contact and indented by adjacent neuropodial tori. Brown spots between thoracic neurochaetal tori and notochaeta absent. Superior thoracic notochaetae elongate, narrowly hooded; inferior group with two rows of shorter, broadly hooded chaetae of type B with hoods 1.5–2 times width compared to the shaft (A/B) or 4–5 times as long as maximum width shaft (C/B). Thoracic uncini avicular with 6–7 equal-size teeth above main fang and covering half of the main fang length, neck shorter than breast (E/F), breast well-developed, medium-size handle, 1–1.5 times the distance from main fang to breast (H/G); companion chaetae with very long, tapered mucros. Abdominal uncini with 6–7 equal-size teeth above main fang, similar to those in thorax but shorter. Pygidium rounded with irregularly arranged eyespots.

Distribution

Southern California, southern Gulf of California (Tovar-Hernández et al. Citation2009) and southern Mexican Pacific (Bastida-Zavala et al. Citation2016).

Remarks

Capa and Murray (Citation2015), based on papers by Perkins (Citation1984) and Tovar-Hernández et al. (Citation2009), reported that Parasabella pallida has inferior thoracic chaeta of type A (with broad hoods and distal ends narrowing abruptly, nearly paleate shape) (see Capa and Murray (Citation2015)’s Figure 2A and table 2). However, specimens from San Francisco, California, herein examined, present chaetae type B, which are observed also in P. pallida from Southern Gulf of California, Mexico, as reported in Tovar-Hernández et al. (Citation2009, figure 4d).

In addition, dorsal lips of P. pallida were reported as short in Capa and Murray (Citation2015), although measurements were not provided. In specimens from San Francisco, dorsal lips are as long as five thoracic segments, and therefore described as long in our description (–)).

Perkins (Citation1984) already commented about the difficulty to distinguish juveniles of P. media, P. pallida and P. rugosa, since these are very similar. He also noted that the degree of spiralling is size-related (PerkinsCitation1984: 295); consequently, it is not a reliable character to distinguish among these three species. Perkins also reported 20–60 vacuolated cells supporting radioles in P. media, 33–41 in P. rugosa and 8–10 in P. pallida. A more useful character observed in all adult stages of the specimens examined in the present study could be the shape of the dorsal lips. In fact, the dorsal lips of P. media and P. rugosa are triangular and tapered (lateral lamellae are narrow, covering the radiolar appendage or mid-rib, that ends as a long filament); in P. pallida, dorsal lips have a broad, rounded base formed by lateral lamellae and a medium-size distal filament.

In , Capa and Murray (Citation2015) suggested some characters to distinguish the different species of Parasabella. One of the characters considered useful to distinguish P. fullo from P. pallida was reported to be the type B inferior thoracic notochaetae in the first and type A in the latter, respectively. However, this appears to be in error. Our analysis found that specimens of P. pallida from San Francisco Bay have the same type of chaetae of P. fullo.

Ventral shield of collar about twice broader than long 2

- Ventral shield of collar about three times broader than long 3

Radiolar tips digitiform with broad flanges; dorsal collar margins as long as 3 thoracic segments in dorsal viewP. fullo (Grube, Citation1878)

- Radiolar tips filiform with narrow flanges; dorsal collar margins as long as 2 thoracic segments in dorsal view P. pallida Moore, Citation1923

Radioles in partial-spiraled arrangement at least in large specimens P. rugosa (Moore, Citation1904)

- Radioles in semicircular arrangement on all sizes P. media (Bush, Citation1905)

Key to the species of Parasabella in California

Conclusive remarks

The analysis and re-description of Parasabella fullo is important to clarify the characters and provide elements for identification, especially considering biogeography and detecting new invasions by non-indigenous species. The recent confirmed records of P. fullo suggest the species may have invaded the coast of California, being detected in two different bays several hundred kilometers apart in 2011 (), but it is not yet clear whether there are established populations here. It is noteworthy that (a) the specimens examined in our analysis were collected only on small boats, which are transient, rather than resident substrate in these bays, and (b) this species was not detected in 2017 and 2018 during our more recent panel surveys (n > 50 panels analyzed in each year; Ruiz et al., unpublished data) in Long Beach, California, which occurs between San Diego and Santa Barbara. Thus, while record of the species occurrences in California are reported by Ashton et al. (Citation2012), and it is listed in the recent regional checklist by SCAMIT (Citation2018), careful analysis of past records of Parasabella spp. and additional surveys are needed to confirm whether and where the P. fullo has established populations in the region. We hope the diagnostic characters outlined in this paper will facilitate such analysis and future detection.

Despite the limited records on transient vessels, we nonetheless hypothesize that P. fullo is established in California waters, because the type of small vessels involved in California are primarily involved in regional routes (Zabin et al. Citation2014); moreover, visits to ports in Japan and Russia are extremely rare for any single one of these vessels, let alone two. Small recreational and fishing boats likely play an important role in the secondary, coastwise spread of NIS (Zabin et al. Citation2014). Therefore, we surmise that one or more populations of P. fullo is likely to exist along the northeastern Pacific, allowing colonization of vessels operating within (and restricted to) this region.

The potential impact of an invasion by P. fullo in California and the northeastern Pacific is poorly understood. If established in one or more bays, the species has the opportunity to spread coastwise across latitudes, as most introduced species to this coastline have undergone secondary spread to additional bays (Ruiz et al. Citation2011). However, the effects of most introduced marine species are not known (Ruiz et al. Citation1999; Ojaveer et al. Citation2015), as these are quantified for relatively few species. Even when documented, such effects vary in space and time, causing high uncertainty in predictions of new invasions. More specifically, for Parasabella species, relatively little is known about its ecological effects. In Southern Gulf of California, P. pallida reaches densities of 400 ind/m2 on buoys during summer (Tovar-Hernández & Yáñez-Rivera Citation2010, technical report). Tovar-Hernández et al. (Citation2017) reported transverse fission and regeneration in P. columbi (Kinberg, Citation1867) as a common phenomenon, suggesting the potential for both sexual and asexual propagation and spread. This characteristic is similar to that present in Branchiomma bairdi (McIntosh, 1885), which may contribute to its high abundance and geographic spread. Another sabellid worm, Sabella spallanzanii (Gmelin, 1791), has invaded Australia and New Zealand and had significant impacts on infaunal community composition (Ahyong et al. Citation2017). Since species of the genus Parasabella have some ecological, reproductive and physiological traits similar to S. spallanzanii and B. bairdi, this suggests they also may have the potential disperse, colonize, invade and impact new habitats (Read et al. Citation2011; Tovar-Hernández et al. Citation2011; Ahyong et al. Citation2017), but studies are critically needed to understand the role of P. fullo and other NIS Parasabella species in new habitats.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Curator Birger Neuhaus of the Museum für Naturkunde Leibniz in Berlin (Germany) and Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (Pennsylvania) for the syntype material, to Ian Davidson and Gail Ashton to provide the material from Recreational Boat project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahyong ST, Kupriyanova E, Burghardt I, Sun Y, Hutchings PA, Capa M, Cox SL. 2017. Phylogeography of the invasive Mediterranean fan worm, Sabella spallanzanii (Gmelin, 1791), in Australia and New Zealand. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 97(5):985–991. DOI: 10.1017/s0025315417000261.

- Annenkova NP. 1938. Polychaetes of the Northern part of the Sea of Japan and their facies and vertical distribution. – Trudy Gidrobiologicheskoj Ekspeditsii ZIN AN SSSR na Japonskoe more. Proceedings of Hydrobiological Expedition of the Zoological Institute at the Sea of Japan 1:81–320. (In Russian).

- Ashton VG, Zabin C, Davidson I, Ruiz G. 2012. Aquatic invasive species vector risk assessments: Recreational vessels as vectors for non-native marine species in California. Report. pp. 75. USA, California Ocean Science Trust. Available: http://www.opc.ca.gov/webmaster/ftp/project_pages/AIS/AIS_RecVessel.pdf Accessed Jan 2020 30.

- Banse K. 1979. Sabellidae (Polychaeta) principally from the Northeast Pacific Ocean. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada 36(8):869–882. DOI: 10.1139/f79-125.

- Bastida-Zavala JR, McCann LD, Keppel E, Ruiz GM. 2017. The Fouling serpulids (Polychaeta: Serpulidae) from the coasts of United States coastal waters: An overview. European Journal of Taxonomy 344:1–76. DOI: 10.5852/ejt.2017.344.

- Bastida-Zavala JR, Rodríguez Buelna AS, de León-González JA, Camacho-Cruz KA, Carmona I. 2016. New records of sabellids and serpulids (Polychaeta: Sabellidae, Serpulidae) from the Tropical Eastern Pacific. Zootaxa 4184(3):401–457. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4184.3.

- Blake JA, Ruff E. 2007. Polychaeta. In: Carlton JT, editor. The Light and Smith Manual. Intertidal invertebrates from Central California to Oregon. 4th ed. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. pp. 309–410.

- Bush KJ. 1905. Tubicolous annelids of the tribes Sabellides and Serpulides from the Pacific Ocean. Harriman Alaska Expedition 12:169–346.

- Buzhinskaja GN. 1967. On the ecology of polychaete worms (Polychaeta) from Possiet Bay of the Sea of Japan. Issledovanija Fauny Morej Explorations of the Fauna of the Seas 5(13):78–124.

- Buzhinskaja GN. 1985. Polychaeta of the shelf off south Sakhalin and their ecology. Akademia nauk Zoologicheskii Institut Issledovania fauna morei 30:72–224. (In Russian).

- Buzhinskaja GN. 2013. Polychaetes of the Far East of Russia and adjacent waters of the Pacific Ocean: Annotated checklist and bibliography. Moscow: KMK Scientific Press. pp. 131.

- Capa M, Murray A. 2015. Integrative taxonomy of Parasabella and Sabellomma (Sabellidae: Annelida) from Australia: Description of new species, indication of cryptic diversity, and translocation of some species out of their natural distribution range. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 175:764–811. DOI: 10.1111/zoj.12308.

- Grube AE. 1878. Einige neue anneliden aus Japan. Jahres-Bericht der Schlesischen Gesellschaft für Vaterländische Cultur 55 [1878 for 1877]:104–106.

- Hartman O. 1944. Polychaetous annelids from California, including descriptions of two new genera and nine new species. Part VI Paraonidae, Magelonidae, Longosomidae, Ctenodrilidae, and Sabellariidae. Allan Hancock Pacific Expeditions 10(2):239–388.

- Hartman O. 1969. Atlas of the Sedentariate Polychaetous Annelids from California. Allan Hancock Foundation, University South California, Los Angeles.

- Imajima M, Hartman O. 1964. The polychaeatous annelids of Japan. Part II. Allan Hancock Foundation Occasional Paper 26:1–452.

- Johansson KE. 1922. On some new tubicolous annelids from Japan, the Bonin Islands and the Antarctic. Arkiv för Zoologi 15:1–11.

- Johansson KE. 1925. Bemerkungen über die Kinberg’schen Arten der Familien Hermellidae und Sabellidae. Arkiv for Zoologi 18A:1–28.

- Johansson KE. 1927. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Polychaeten–Familien Hermellidae, Sabellidae und Serpulidae. Zoologiska Bidrag från Uppsala 11:1–184.

- Kinberg JGH. 1867. Annulata nova. Öfversigt af Königlich Vetenskapsakademiens förhandlingar, Stockholm 23(9):337–357.

- Latreille PA. 1825. Familles Naturelles du Règne Animal exposées succinctement et dans un ordre analytique avec l´indication de leurs genres etc. Paris: J.B. Baillière. pp. 590.

- Loi T-N. 1980. Catalogue of the types of polychaete species erected by J. Percy Moore. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia 132:121–149.

- Moore JP. 1904. New Polychaeta from California. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 56:484–503.

- Moore JP. 1923. The polychaetous annelids dredged by the USS “Albatross” off the coast of southern California in 1904. IV. Spionidae to Sabellaridae. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 75:179–259.

- Moore JP, Bush KJ. 1904. Sabellidae and Serpulidae from Japan, with descriptions of new species of Spirorbis. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 56:157–179.

- Ojaveer H, Galil BS, Campbell ML, Carlton JT, Canning-Clode J, Cook EJ, Davidson AD, Hewitt CL, Jelmert A, Marchini A, McKenzie CH, Minchin D, Occhipinti-Ambrogi A, Olenin S, Ruiz G. 2015. Classification of non-indigenous species based on their impacts: Considerations for application in marine management. PLoS Biology 13(4):e1002130. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002130.

- Okuda S. 1938. Polychaetous annelids from the Ise Sea. Dobutsugaku Zasshi 50:122–131. (In Japanese).

- Perkins TH. 1984. Revision of Demonax Kinberg, Hypsicomus Grube, and Notaulax Tauber, with a review of Megalomma Johansson from Florida (Polychaeta: Sabellidae). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 97:285–368.

- Read GB, Inglis G, Stratford P, Ahyong ST. 2011. Arrival of the alien fanworm Sabella spallanzanii (Gmelin, 1791) (Polychaeta: Sabellidae) in two New Zealand harbours. Aquatic Invasions 6(2):273–279. DOI: 10.3391/ai.2011.6.3.04.

- Ruiz GM, Fofonoff P, Hines AH, Grosholz ED. 1999. Nonindigenous species as stressors in estuarine and marine communities: Assessing impacts and interactions. Limnology and Oceanography 44:950–972. DOI: 10.4319/lo.1999.44.3_part_2.0950.

- Ruiz GM, Fofonoff PW, Steves B, Foss SF, Shiba SN. 2011. Marine invasion history and vector analysis of California: A hotspot for western North America. Diversity and Distributions 17:362–373. DOI: 10.1111/ddi.2011.17.issue-2.

- SCAMIT. 2018. A taxonomic listing of benthic macro- and megainvertebrates from infaunal & epifaunal monitoring and research programs in the Southern California Bight. 12th ed. Cadien DB and Lovell LL (eds). pp. 167. Los Angeles, Southern California Association of Marine Invertebrate Taxonomists. Available: https://www.scamit.org/publications/SCAMIT%20Ed%2012-2018.pdf Accessed Jan 2020 30.

- Tovar-Hernández MA, De León-González JA, Bybee D. 2017. Sabellid worms from the Patagonian Shelf and Humboldt Current System (Annelida, Sabellidae): Phyllis Knight-Jones’ and José María Orensanz’s collections. Zootaxa 4283(1):1–64. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4283.1.1.

- Tovar-Hernández MA, Harris LH. 2010. Parasabella Bush, 1905, replacement name for the polychaete genus Demonax Kinberg, 1867 (Annelida: Polychaeta: Sabellidae). ZooKeys 60:13–19. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.60.547.

- Tovar-Hernández MA, Méndez N, Villalobos-Guerrero TF. 2009. Fouling polychaete worms from the southern Gulf of California: Sabellidae and Serpulidae. Systematics and Biodiversity 7(3):319–336. DOI: 10.1017/S1477200009990041.

- Tovar-Hernández MA, Yáñez-Rivera B. 2010. Poliquetos invasores (Annelida: Polychaeta) del Puerto de Mazatlán, Sinaloa. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Unidad Académica de Mazatlán, Laboratorio de Invertebrados Bentónicos II. Informe final SNIB-CONABIO. Proyecto No. GN002. México D.F. 18 páginas, 5 anexos y una base de datos (BIOTICA), Mazatlán.

- Tovar-Hernández MA, Yáñez-Rivera B, Bortolini-Rosales JL. 2011. Reproduction of the invasive fan worm Branchiomma bairdi (Polychaeta: Sabellidae). Marine Biology Research 7(7):710–718. DOI: 10.1080/17451000.2010.547201.

- Uchida H. 1968. Polychaetous annelids from Shakoten (Hokkaido). Journal of Faculty of Science Hokkaido University Series VI. Zoology 16:595–612.

- Uschakov PV. 1955. Polychaeta of the Far Eastern Seas of the USSR (Polychaeta). Opredeliteli po faune SSSR [Definition Keys to the Fauna of the USSR] 56:1–445. (In Russian).

- von Marenzeller E. 1884. Südjapanische Anneliden. II. Amphareten, Terebellacea, Sabellacea, Serpulacea. Denkschriften der Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien 49(2):28.

- Zabin JC, Ashton VG, Brown WC, Davidson CI, Sytsma DM, Ruiz GM. 2014. Small boats provide connectivity for nonindigenous marine species between a highly invaded international port and nearby coastal harbors. Management of Biological Invasions 5(2):97–112. DOI: 10.3391/mbi.2014.5.2.03.

- Zachs IG. 1933. On the annelid fauna of the Northern Sea of Japan. Issledovanija Morej SSSR [Explorations of the Seas of the USSR] 19:125–137. (In Russian).