Abstract

A stunning scarlet-coloured clearwing moth was found mud-puddling on a rainforest river bank in Malaysia and is described herein as a new genus and species, Scarlata nirvana gen. et sp. Nov.. This sesiid seems to be a rare case of a mimic of an assassin bug (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in a family otherwise known for hymenopteran mimicry. A high-quality video of the moth’s behaviour in its habitat is provided. Studies of the collections of the Natural History Museum in London revealed another member of the new genus, S. guichardii sp. nov. A third species, S. ignisquamulata Kallies, 2018 comb. nov. is transferred to Scarlata gen. nov. from the genus Aschistophleps Hampson, 1892. The second new lineage from Malaysia described here, Malayomelittia gen. nov., includes two species, Malayomelittia pahangensis Skowron, 2015 comb. nov. and M. ruficrista Rothschild, 1912 comb. nov. Additionally, Heterosphecia bantanakai Arita & Gorbunov, 2000 is placed as a junior synonym of H. hyaloptera Hampson, 1919 syn. nov. Morphological descriptions, remarks on behaviour, conditions of occurrence and a discussion about potential mimicry models are included. All new taxa are figured, including images of male genitalia.

https://urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:32AF6419-F859-4931-BCA7-848B636CC2EE

New genus Scarlata: https://urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:B8DC2871-DF12-49A9-A7A7-D67E60776E91

New genus Malayomelittia: https://urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:07B2830B-7E00-4B9D-9D5A-82A7538427F9

Introduction

Oriental clearwing moths (Lepidoptera: Sesiidae) are rarely encountered in nature, yet it has been observed in recent years that they come to river banks, streams, puddles and wet soil remaining after drying out of flowing water, seeking moisture and minerals (Gorbunov Citation2015; Skowron et al. Citation2015). The observation of this behaviour (known as puddling, or mud-puddling) has recently allowed for both taxonomic (Gorbunov Citation2015; Kallies & Štolc Citation2018; Skowron Volponi Citation2020) and novel behavioural studies (Skowron Volponi et al. Citation2018) of these elusive insects. Interestingly, this behaviour has been noted only for representatives of the tribe Osminiini in Asia and in one case for the tribe Similipepsini in Africa (Sáfián & Pühringer Citation2016). Exactly why sesiids come to the vicinity of flowing water and are not observed near lakes or at salt licks away from water sources remains to be elucidated. Clearwing moths are predominantly diurnal lepidopterans known for their often striking resemblance to hymenopterans. Mimicking features include narrow, at least partially transparent wings, bright colouration and sometimes narrowed or misleadingly coloured abdominal segments, resembling a wasp-waist. Several genera have characteristic tufts of elongated hair-like scales on the hind legs which further add to their hymenopteran-like appearance.

The Osminiini are probably the most diverse Sesiidae tribe in the Oriental region. This paper contributes to the process of taxonomic clarification within the group.

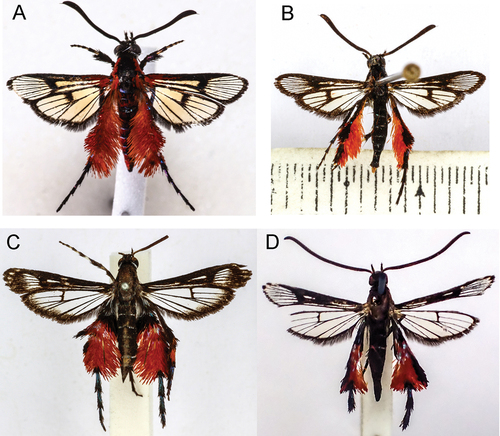

In their study from 2018, Kallies & Štolc proposed the genus Pyrophleps Arita & Gorbunov, Citation2000 to be a junior subjective synonym of Aschistophleps Hampson, Citation1892, arguing that the latter genus is more diverse than previously thought. Recently, Gorbunov (Citation2021) restored the genus Pyrophleps and described a new, closely related genus Nepyrophleps. Taking into account major morphological differences in genitalia, hind leg tufts, labial palps and eye shape in these Osminiini genera, I consider Pyrophleps and Nepyrophleps to be valid taxa. Based on new findings in Southeast Asia, as well as specimens from the Natural History Museum in London, I derive two further genera of the Osminiini tribe, Malayomelittia gen. nov. and Scarlata gen. nov., describe two new species, Scarlata nirvana sp. nov. (see suppl. video; , 3(a), 4(b) and 5) and S. guichardii sp. nov. ( (b) and 6), and transfer three species from the genera Aschistophleps Hampson, Citation1892 and Heterosphecia Le Cerf, 1916 (i.e. ruficrista, ignisquamulata, pahangensis, bantanakai).

Figure 2. Scarlata nirvana gen. et sp. nov. exposing its hind leg tufts in a common feeding position of this species.

Figure 3. (a) Scarlata nirvana gen. et sp. nov. holotype male; (b) S. guichardii gen. et sp. nov. holotype male; (c) Malayomelittia ruficrista comb. nov. holotype female; (d). M. ruficrista male NHMUK10605228.

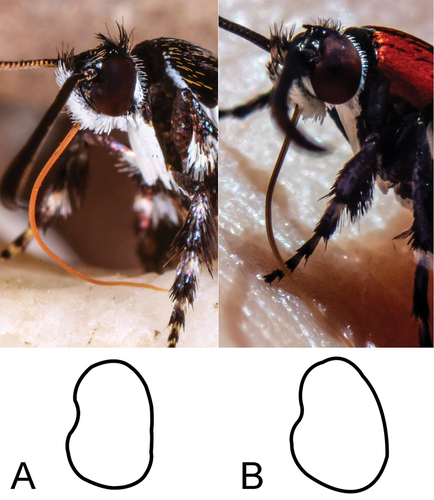

Figure 4. Details of the head and outline of the eye of: (a) Malayomelittia pahangensis comb. nov.; (b) Scarlata nirvana gen. et sp. nov. Note differences in the shape of the eye and in scaling of labial palp apically.

The type species of the new genera described herein, Malayomelittia pahangensis comb. nov. (figured and filmed in Skowron et al. Citation2015; Skowron Volponi et al. Citation2018, Citation2021) and Scarlata nirvana sp. nov., were both found puddling on banks of crystal clear rivers flowing through Malaysian rainforests. It is highly probable that their existence depends on the conservation of these pristine ecosystems.

Methods

The type specimen of S. nirvana, as well as all of the studied specimens of M. pahangensis, were collected without the use of synthetic sex attractants. Temperature and air humidity were measured with an electronic thermo-hygrometer placed in the shade.

Dissections were performed by abdomen lysis in proteinase K (55°C, overnight), and genitalia dehydrated by passing through ethanol solutions of increasing concentration. The genitalia were then mounted in Euparal. Specimens were studied and genitalia photographed with a Leica M80 stereomicroscope coupled with a Sony α6500 camera (S. guichardii and M. ruficrista) and Leica M205A stereomicroscope (S. nirvana).

Taxonomic accounts

Abbreviations. ATA = anterior transparent area, ETA = external transparent area, PTA = posterior transparent area.

Malayomelittia Skowron Volponi gen. nov.

Type species: Heterosphecia pahangensis Skowron, 2015.

Heterosphecia pahangensis: Skowron et al. Citation2015; Skowron Volponi et al. Citation2018, Citation2021

Small (alar expanse 10–17 mm) and slender clearwing moths with highly conspicuous tufts of elongated scales on the hind legs (resembling pollen baskets of bees in the type species). Representatives of Malayomelittia do not use their hind legs for locomotion but rather to expose the tufts of hair-like scales by making delicate flicking movements. Frons smoothly scaled; labial palps long and upturned, with wide, elongated, erect scales ventrally and elongated hair-like scales apically; proboscis long and well-developed; vertex with elongated scales. Thorax covered with smooth scales. Legs: fore, mid and hind femur smooth scaled; fore and mid tibia and tarsus with elongated scales gradually shortening towards the 5th tarsomere; characteristic tufts of erect hair-like scales on hind tibia and 1st tarsomere. Hind tarsi extend further caudally than abdomen. Both fore- and hindwings rather slender; forewing with well-developed transparent areas covered with semi-hyaline scales, vein R5 absent (possibly fused with R4), R3 and R4 separated basally, M1 terminating at apex, CuA1 and CuA2 arising from a common point, cross vein rugged, remnant of veins 1A+2A very short; hindwing transparent, partially covered with semi-hyaline scales, vein M2 arising from about middle of cross-vein, distance between origin of vein CuA1 and M3 more than seven times that between M3 and cross-vein, 1A well-developed, arising from 2A, remnant of veins 2A+3A fused distally. Abdomen smooth scaled, with narrow whitish bands, anal tuft very small. Male genitalia: valva broad with an upturned extension, mostly covered by long setae; gnathos developed, pointed distally; uncus covered with setae; tegumen somewhat narrowed distally; saccus quite long and thin, with a flat or slightly bifurcate base; aedeagus about twice as long as valva.

Differential diagnosis

The new genus appears to be closest to Aschistophleps Hampson, 1893, Scarlata gen. nov. and Heterosphecia Le Cerf, 1916 demonstrating a combination of their features (Arita & Gorbunov Citation1995, Citation2000). Hind tarsi extend further caudally than abdomen, they are not as long as in Aschistophleps, but longer than in Heterosphecia. Hind tibia and 1st tarsomere entirely, strongly tufted with hair-like scales (only apical half of hind tibia tufted in Aschistophleps). The shape of fore- and hindwings and venation differ from Heterosphecia (distance between base of vein CuA1 and M3 about seven times longer than that between M3 and cross-vein in Malayomelittia, these distances are of equal length in Heterosphecia) and more closely resemble the wings of Aschistophleps (except that veins R3 and R4 do not arise from a common point). The male genitalia differ from all other genera in the shape of the valvae and are most similar to Heterosphecia. However, they are not as robust as and can be further differentiated by the pointed gnathos and the rather long thin saccus. Furthermore, Malayomelittia differs from all species of Heterosphecia by the much less robust body and this is quite obvious when specimens, either pinned or alive, are seen next to each other. For differences between Malayomelittia and Scarlata, see differential diagnosis for Scarlata gen. nov. Representatives of Malayomelittia do not use their hindlegs at all for locomotion (see Suppl. video in Skowron et al. Citation2015), whereas species of Heterosphecia (see Suppl. Video of Skowron Volponi & Volponi Citation2017a), Melanosphecia (see Suppl. video in Skowron Volponi Citation2019) and Aschistophleps (see Suppl. video in Skowron Volponi & Volponi Citation2018) use them actively to move around and Pyrophleps (see Suppl. video in Skowron Volponi & Volponi 2017), as well as Scarlata keep their hindleg tarsi curled up, using them occasionally to tap the ground (Suppl. Video TC 02:41–02:47; ).

Composition: Only two known species belong to this newly described genus: Malayomelittia pahangensis (Skowron, Citation2015), comb. nov. and Malayomelittia ruficrista (Rothschild, Citation1912), comb. nov.

Etymology. The name derives from Malaysia, the country of origin of representatives of this genus, and the Greek “melitta” (bee), due to the type species’ splendid mimicry of Trigona bees. The gender is feminine.

Malayomelittia ruficrista (Rothschild, Citation1912), comb. nov..

Aegeria ruficrista Rothschild, Citation1912: 122. Holotype ♀ (not ♂!), ORIGINAL LABELS: “Type; 4th Mile Rock Road 21-4-09; Aegeria ruficrista Rothsch. Type; Tring Mus. 190; 2.; Rothschild Bequest B.M.1939-1.; BMNH(E) #846007; NHMUK010605231”.

Aschistophleps ruficrista: Arita & Gorbunov Citation1995: 83; Kallies & Štolc Citation2018: 597.

Pyrophleps ruficrista: Arita & Gorbunov Citation2000: 65; Skowron Volponi & Volponi 2017: 134.

MATERIAL. 2♂, 2♀, all in NHMUK. Holotype ♀, Borneo, Sarawak, Kuching, 4th Mile Rock Road, 21.IV.1909, W. Rothschild, NHMUK010605231; 1♂, same location, 06.VI.1909, W. Rothschild, NHMUK010605227; 1♂, same location, 08.IV.1909, W. Rothschild, NHMUK010605228, genitalia slide no. NHMUK010316680; 1♀, Borneo, Sarawak, Kuching, T. Hewitt [?], NHMUK010605226.

The original species description written by Rothschild (Citation1912) was based on the female holotype. However, Rothschild additionally collected two male individuals of this species (both of which are in the NHMUK collection, in a slightly worse condition than the female holotype) in the same location and period. This allowed me to perform genitalia dissection, whose morphology proved highly similar to that of M. pahangensis Skowron, Citation2015 comb. nov. Sexual dimorphism is not highly pronounced in M. ruficrista. However, the male has a more developed external transparent area of the forewing and less scaling on the hindwing margins than the female. The two studied males also have more black scales in the external part of the hindleg tuft in comparison to the female. However, this might only be intraspecific colour variation (M. pahangensis males differ greatly in hindleg tuft colouration), rather than sexual dimorphism.

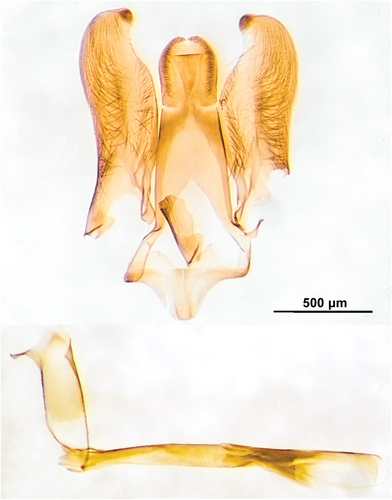

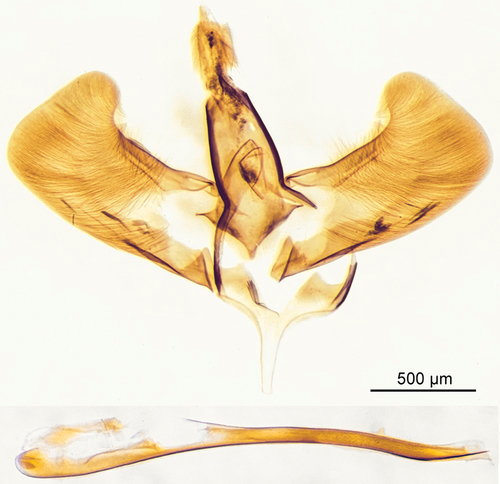

Male genitalia. Tegumen-vinculum form a perfectly round ring, tegumen gradually narrowing towards uncus; gnathos small and distally pointed; uncus covered with quite long delicate setae; valva broad, rectangular in proximal 2/3, distal 1/3 upturned and rounded, long setae covering nearly entire valva; saccus rather long and slender, gradually narrowing towards bluntly-ended apex; aedeagus almost twice as long as valva.

Scarlata Skowron Volponi gen. nov.

Type species: Scarlata nirvana Skowron Volponi sp. nov.

Small (wingspan 14–17 mm) and slender clearwing moths with scarlet coloured, conspicuous hindleg tufts of elongated scales. Antennae simple and clavate, frons covered with smooth scales, labial palpi mostly smooth-scaled with narrow elongated scales at tip and wide, slightly erected scales at base. Thorax and abdomen covered with smooth scales, either scarlet or black. Wings mostly transparent with broad black fore- and hindwing discal spots and margins. Male genitalia morphology distinct from other Osminiini: uncus with very short sclerotized setae on margins, similar setae forming a small patch or row at tip of valva, valva folded inwards subapically on coastal margin.

Differential diagnosis

Superficially similar to Malayomelittia and Aschistophleps but can be differentiated by the morphology of the male genitalia, the shape of the eye, scaling of labial palps (more hair-like scales apically in Malayomelittia), broader hindwing discal spot and the structure of the hindleg tuft: in Scarlata, the hair-like scales are strongly elongated on the inner margin, moving towards the dorsal side there is a narrow groove covered with shorter scales followed by a ridge of elongated scales dorsally, the tuft of elongated scales continues onto the proximal half of the 1st tarsomere only on the inner margin, on the hindleg outer side the scales are elongated only on the tibia, the 1st tarsomere is dorsally and externally smooth-scaled. Scarlata does not have a tuft of hair-scales on the midleg. In Malayomelittia the hindleg tuft is made of almost equally elongated scales dorsally and on both inner and outer sides of tibia and entire 1st tarsomere. Aschistophleps has a tuft of hairs on the midleg tibia and two small tufts on the hind leg which allows for the immediate differentiation from closely related genera. Overall, the hindleg tufts of the genera Scarlata, Malayomelittia and Heterosphecia are very conspicuous, made of dense, elongated scales. In the slender-bodied species of Pyrophleps, these tufts are much less impressive and scales less elongated.

In the field, representatives of the genus Scarlata can be differentiated from Malayomelittia and Aschistophleps by their posture, especially different ways of exposing the hind leg tufts. Scarlata species often spread out their wings (; Suppl. video TC 02:50–03:05), showing the bright red hind legs with tarsi curled up, not using them much to move around. Malayomelittia, when puddling, always keeps its wings folded back against the body and rises the hind legs upwards, often moving them slightly to expose the conspicuous tufts (see Suppl. video in Skowron et al. Citation2015), but never uses them to walk, whereas Aschistophleps, keeping its wings folded against its body and hind legs on the outer side of the wings, uses the hind legs actively for locomotion. Pyrophleps species do not expose hindleg tufts significantly but keep the hind legs close to their slender abdomens and most of the time concealed beneath the wings.

From the similarly-coloured species of Akaisphecia Gorbunov and Arita (1995), Scarlata can be distinguished by the absence of a filiform appendix on the abdomen, structure of hind leg tufts, well-developed forewing transparent areas and morphology of male genitalia.

Composition: This genus consists of three species: S. ignisquamulata Kallies, 2018 comb. nov.; S. nirvana Skowron Volponi sp. nov. and S. guichardii Skowron Volponi sp. nov.

Scarlata nirvana sp. nov..

Type material: Holotype ♂, pinned. Original labels: Malaysia: Pahang Merapoh, 04°39.04ʹN 102°01.80ʹE, 22 VII 2018, M.A. Skowron Volponi; Holotype ♂, Scarlata nirvana sp. nov., des. M.A. Skowron Volponi et al. Citation2021; Genitalia slide ♂, no. MSV-17. Will be deposited in NHMUK.

Wingspan: 16.5 mm

Head: Antennae black dorsally and at tip, admixture of yellow and orange scales ventrally, setae at tip black; small patch of smooth white scales near base of antennae; vertex with slightly elongated black scales; ocelli black; frons smooth-scaled, black in upper half, white in lower half; labial palpi white with black tip, slightly elongated scales towards tip; proboscis long, functional, brown; pericephalic hairs white ventrally and laterally, black with some pale yellow dorsally.

Thorax: Patagia black; thorax dorsally scarlet red with a wide black longitudinal stripe and two very thin black lines bilaterally; laterally black with silver sheen; scarlet setae at wing insertions.

Legs: Fore coxa white with several black and orange scales ventrally; fore femur black; fore tibia with black elongated scales: some with a red tinge to them; fore tarsi black with pale orange and white smooth scales at basal half; mid coxa black with silver sheen in basal half, white in distal half; mid femur black with individual beige and orange scales dorsally; mid tibia black with some elongated scales, spurs black, tarsomeres black with elongated white scales at base of 1st tarsomere and smooth creamy white scales at bases of tarsomeres 2–5; hind coxa white with some black scales; hind femur black; hind tibia entirely scarlet red with elongated scales dorsally and laterally forming a conspicuous tuft continuing to 1st tarsomere on inner margin, dorsal and outer part of 1st tarsomere smooth-scaled, scarlet in basal half and black in distal half; tarsomeres 2–5 smooth-scaled, black with admixture of pale orange scales at bases of tarsomeres 2 & 3 ventrally; upper spur white with some black scales; lower spur black ventrally and red dorsally, white scales at base of both spurs.

Forewing: Well-developed transparent areas with a blue sheen in sunlight; veins, margins and discal spot covered with black scales; scarlet red scales at base, along costal margin until about half the length of ATA and along cubital vein until about basal 1/3 of ATA; ATA densely covered with transparent scales, some transparent scales also in PTA and ETA; black scales from costal margin to vein R2. Each transparent cell in ETA divided by very thin longitudinal black stripes; ventrally scarlet scales along veins from base until discal spots; cilia black.

Hindwing: Transparent with black scales along veins, margins and on discal spot dorsally; some scarlet scales at basal part of margins and veins; some transparent scales in cell between veins 2A and 1A; ventrally scarlet red scales along veins from base until discal spots, along vein 2A and costal margin; 1A black; cilia black.

Abdomen: Scarlet red with black tergite margins dorsally and laterally; sternites 1–5 proximally black, distally white; sternites 6–7 black with faint white distal margin; sternite 8 black; anal tuft very small, black.

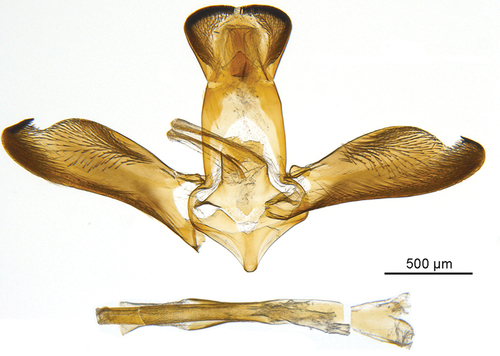

Male genitalia: Tegumen and uncus broad; uncus wider than tegumen, heart-shaped, with margins covered by very short sclerotized setae distally and slightly longer laterally; gnathos wide and triangular; valva elongated, arched costal edge with a distinct inward fold forming a tapered apex, short hair-like setae densely scattered on ventral margin and in apical area, more sparsely distributed near ventral margin and in medial part, small linear patch of short, well-sclerotized setae ventroapically; saccus short, triangular, rounded at tip; aedeagus simple, narrow, longer than valva.

Female unknown.

Differential diagnosis

This species is most similar to S. ignisquamulata. It can be differentiated primarily by the conformation of male genitalia (See in Kallies & Štolc Citation2018): triangular gnathos (rounded in S. ignisquamulata), shape of valva, especially the strongly arched coastal margin (straight in species compared), rounded tip of saccus (blunt in S. ignisquamulata), longer aedeagus. It additionally differs in details of colouration: labial palps with black tips (white with some brown scales in species compared), more black scales on thorax, less red scales on both fore- and hindwing, broader ATA and PTA, narrower hindwing discal spot. From S. guichardii sp. nov. it differs in the overall body colouration (mostly black in species compared) and conformation of male genitalia.

Etymology

This species is named after the Nirvana Asia Group, who co-financed the expedition to Malaysia during which this new species was discovered.

Behaviour, habitat and conditions of occurrence

Males of S. nirvana puddle on moist sand and rocks on river banks flowing through tropical rainforests in Malaysia. The sesiid often lands amongst hymenopterans, especially bees, but was not observed within butterfly aggregations nearby. Puddling behaviour of this species is most probably aimed at gaining salt because it readily licked sweat from human skin (Suppl. video TC 01:54–01:58). S. nirvana occurs on hot, sunny days only, with temperature ranging from 29°C to 32°C and air humidity 64–73%. S. nirvana holds its wings either folded back against the body, covering the hindleg tufts of elongated scales (tips of wings not overlapping, ), or spread out, exposing the scarlet red tufts on hindleg tibiae (). The hind legs are not actively used for locomotion, however the sesiid taps the ground with the curled-up tarsi when moving around. When flying within a small area, e.g. whilst searching for a puddling spot, the sesiid traces rugged trajectories low above the ground (Suppl. video TC 00:13–00:25; 00:50–01:00,02:12–02:24). However, when covering a larger distance or escaping from a puddling spot, S. nirvana flies in an almost vertical position, with the bright scarlet colouration of thorax, abdomen and hindleg tuft making it visible from a distance despite the moth’s small size. This peculiar position in flight resembles that of assassin bugs (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) often encountered in Malaysian rainforests.

Observations: Merapoh: one individual end of April 2016; two individuals seen in two consecutive days in July 2018. Royal Belum State Park: one individual beginning of August 2018, second near end of August 2019. Only one specimen was collected as the other from Merapoh escaped rapidly, whereas those observed in the protected Royal Belum forest could not be captured but were filmed in detail.

Scarlata guichardii sp. nov..

Type material: Holotype ♂, pinned. Original labels: SABAH: Poring Hot Springs 8.5.1973. K.M.Guichard; Brit. Mus. 1974–219; Fig’d in Smaller Moths of SE Asia – Robinson, Tuck & Shaffer, Citation1994; NHMUK010605230, genitalia slide no. NHMUK010316681 (NHMUK, misidentified as Aschistophleps ruficrista Rothschild, Citation1912).

Wingspan: 14 mm

Head: Antennae including setae at tip black; frons and vertex black; compound eyes black; labial palps white in basal ¾, black with some orange scales in distal ¼.

Thorax: Black and smooth-scaled, black setae at wing insertion.

Legs: Forelegs black with white coxae; midlegs black, hind legs dorsally black with tufts of scarlet hair-like scales on tibia and inner margin of 1st tarsomere; tarsomeres 2–5 black.

Forewing: Transparent with broad black discal spot (protruding slightly into ETA), black scales on margins, veins and running from costal margin to vein R2; each transparent cell in ETA divided by very thin longitudinal black stripes; several scarlet scales around discal spot ventrally; cilia black.

Hindwing: Transparent with black scales along veins; broad black scaling on margins, in distal part of cell between veins 1A and 2A, as well as on discal spot, which protrudes into cell between veins Cu1 and Cu2.

Abdomen: black, tergites with narrow white margins.

Male genitalia: Tegumen broad, slightly narrowing towards uncus, uncus oval, about as wide as tegumen with margins covered by very short sclerotized setae; gnathos triangular-shaped, rounded at tip; valva elongated with slightly arched coastal margin, inward fold subapically, small round patch of sclerotized short setae at apex, longer setae densely scattered along ventral margin into medial area but sparsely along coastal margin; saccus short and rounded basally; aedeagus simple, narrow, longer than valva.

Female unknown.

Differential diagnosis

S. guichardii is superficially most similar to M. ruficrista, from which it can be distinguished by the remarkably different morphology of the male genitalia. Without performing dissections it is possible to distinguish males of these two species by several external features: very long antennae in M. ruficrista (about length of forewing) and shorter in S. guichardii (about 2/3 of forewing); forewing discal spot has black extensions into ETA in S. guichardii (clearly separated from ETA in M. ruficrista); hindwing discal spot is broader in S. guichardii and extends to cell between veins Cu1 and Cu2; structure of the hind leg tuft: smooth scales externally on 1st tarsomere in S. guichardii, elongated scales on entire tibia and 1st tarsomere in M. ruficrista. From congeners it can be immediately distinguished by the mostly black colouration of the entire body (excluding the red hindleg tibia tufts). Male genitalia resemble those of S. nirvana and S. ignisquamulata but the uncus is narrower and more oval-shaped, whereas the gnathos and valva have an intermediate shape between that of the two congeneric species.

Etymology. This species is named after Kenneth Guichard, a hymenopterist who collected the holotype in 1973, probably whilst searching for wasps.

Habitat and conditions of occurrence

Only one museum specimen, herein designated as holotype, is known. The original label states that the specimen was collected in Poring Hot Springs (Sabah, Malaysia) in May. Poring Hot Springs are located in the Ranau District at an elevation of 550 m. Poring has a tropical climate with plenty rain year-round and temperatures between 20°C and 29°C. There are three rivers in the area providing potentially good habitats for puddling behaviour of insects, including sesiids.

Concluding remarks

Taxonomy

In 1892, Hampson described the genus Aschistophleps stating that it has “(…) mid legs with terminal tufts of hairs on the tibiae; hind legs with two strong tufts on the tibae, and first tarsal joint strongly tufted”. Despite numerous taxonomic changes having been introduced in this genus over the years, as well as the description of multiple new species of the tribe Osminiini, it seems Hampson’s generic description is still valid. The apomorphic character of Aschistophleps is the double tuft on the hind legs instead of one continuous tuft/blade of elongated scales, as in closely related genera. This criterion is currently met by three species only: A. lampropoda Hampson, Citation1892, A. longipoda Arita & Gorbunov Citation2000 and A. argentifasciata; Skowron Volponi, Citation2018 and all of the remaining species currently listed under Aschistophleps should be transferred to different genera. Scarlata ignisquamulata; Kallies & Štolc, Citation2018 has such distinct genitalia morphology that it does not belong in either Aschistophleps or Pyrophleps and the discovery of the two new species described herein has helped to identify its distinguishing features. Further species previously included in Aschistophleps, have been recently transferred to the new genus Aurantiosphecia; Skowron Volponi, Citation2020.

M. ruficrista, another species which was included in the genus Aschistophleps, was initially described as Aegeria ruficrista by Rothschild (Citation1912). The species was found in 1909 on Borneo: Rock Road, Kuching, Sarawak. M. ruficrista has perplexed entomologists for years since its discovery and its generic placement has changed multiple times. These transfers have been performed, however, without studying details of the species’ morphology; Robinson et al. (Citation1994) wrote: “this species is immediately recognizable by the stunning carmine tufts on the hind legs”, but we now know that red colouration of the hindleg tufts occurs not only in different species of Sesiidae, but in several genera. The dissection of M. ruficrista genitalia allowed for proper assignment of this perplexing sesiid. Comparisons of specimens from the NHM collection, including the holotype, with Malayomelittia pahangensis Skowron, Citation2015 revealed striking similarities of these two species and solid differences from all other Osminiini, indicating they constitute a separate lineage. It had already been apparent in the original description of M. pahangensis that it does not belong in the genus Heterosphecia; however, the lack of any other species confirming the existence of a separate lineage led a reviewer to insist on including it in Heterosphecia. This gap has now been filled after the re-examination of old specimens of M. ruficrista. The close relationship of these two Malaysian species is not surprising, as Peninsular Malaysia used to be connected to Borneo, being part of Sundaland 21–17,000 years ago (Woodruff Citation2003). Additionally, re-examination of known Heterosphecia species and DNA barcode analysis showed that Heterosphecia bantanakai Arita & Gorbunov, Citation2000 is in fact a junior synonym of H. hyaloptera Hampson, 1919 syn. nov. These findings will be further discussed in an upcoming paper.

Mimicry

Malayomelittia pahangensis is a fascinating example of bee mimicry, which is both morphologically and behaviourally complex (Skowron et al. Citation2015; Skowron Volponi et al. Citation2018). It has been recently suggested, however, that some clearwing moths may imitate insects other than hymenopterans. Akaisphecia melanopuncta Gorbunov and Arita (1995) is a pyrrhocorid bug mimic (Quicke et al. Citation2018) and at the same time, the first known example of hemipteran mimicry in the family. Scarlata nirvana, with its flashy scarlet colouration and characteristic flight posture does not resemble any sympatric hymenopteran but, especially in flight, seems to imitate aposematically coloured assassin bugs (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Reduviids are venomous and either predacious or hematophagous (with some rare phytophagous cases in South America). They use their venoms not only on their prey but also to defend themselves (Walker et al. Citation2016). Their warning signals have been exploited in the evolution of Batesian mimics, e.g. the Malaysian mantis Hymenopus coronatus Olivier, 1792, which before growing into a nearly perfect imitation of an orchid, in its first instar looks like a small red-and-black assassin bug (Gurney Citation1951). The same colour pattern is followed by S. nirvana (as well as the closely related S. ignisquamulata). These sesiids, red and black with white accents, are very similar to harpactorine reduviids such as Eulyes amoena Guérin, 1838 and Vesbius purpureus Thunberg, 1783 (Reduviidae: Harpactorini), both of which occur in Malaysian rainforests and could possibly have served as evolutionary models for S. nirvana. I believe it is necessary to observe a live individual and consider the natural body posture and behaviour of a species in order to determine its possible mimicry model. Only pinned specimens of S. guichardii and M. ruficrista have been examined.

Supplemental Material

Download MP4 Video (111.9 MB)Acknowledgements

I thank Paolo Volponi for his invaluable help in the field and in editing photos and videos. I am very grateful to Dr David Lees for granting me access to NHM’s collection, his hospitality and for reviewing an advanced version of this manuscript. Many thanks to EL Law for logistic support in Malaysia and help in finding funds. Thank you to Mr Tan Sri Kong Hon Kong, founder of Nirvana Asia Group, for his financial contribution to the expedition. I express my deep gratitude to S. Redza Hussein, Director of Perak State Parks Corporation, for his support in the Royal Belum State Park. My thanks also go to Tan Kar Hing, Chairman of Tourism, Art & Culture Perak (2018–2020) and Pua Kian Sien for their support and deep involvement in the project. I thank Dr Oleg Gorbunov for a productive and inspiring discussion on Southeast Asian Osminiini. I am grateful to Interfoto for lending me a Sony RX 10 III camera. Microscopic photographs of S. nirvana were taken at the Department of Invertebrate Zoology and Parasitology, University of Gdansk. I thank the Economic Planning Unit, Putrajaya for granting permission to perform research in Malaysia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here, and a video can be found at: http://vimeo.com/704171296

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arita Y, Gorbunov O. 1995. A revision of the genus Heterosphecia Le Cerf, 1916 (Lepidoptera: Sesiidae, Osminiini). Tinea 14(2):131–141.

- Arita Y, Gorbunov O. 2000. Notes on the tribe Osminiini (Lepidoptera, Sesiidae) from Vietnam, with descriptions of new taxa. Transacations of the Lepidopterological Society of Japan 51:49–74.

- Gorbunov O. 2015. Scientific note: Clearwing moths (Lepidoptera: Sesiidae) of Laos. I. Akaisphecia melanopuncta O. Gorbunov & Arita, 1995 (Sesiidae: Sesiinae: Osminiini). Tropical Lepidoptera Research 25(2):98–100.

- Gorbunov O. 2021. A new genus of the tribe Osminiini (Lepidoptera: Sesiidae) from the Oriental region. Far Eastern Entomologist 439:1–13. DOI: 10.25221/fee.439.1.

- Gorbunov O, Arita Y. 1995a. A new genus and species of the clearwing moth tribe Osminiini from the Oriental region (Lepidoptera, Sesiidae). Transacations of the Lepidopterological Society of Japan 46:17–22.

- Gorbunov O, Arita Y. 1995b. New and poorly known clearwing moth taxa from Vietnam. Transacations of the Lepidopterological Society of Japan 46(2):69–90.

- Gurney AB. 1951. Praying mantids of the United States, native and introduced. In: Annual report of the board of regents of the Smithsonian Institution. Washington: United States Government Printing Office. pp. 344–345. https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/annualreportofbo1951smit

- Hampson G. 1892. The fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Moths. Vol. I. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Kallies A, Štolc V. 2018. New species of Aschistophleps from Thailand and Laos, with a new generic synonymy (Lepidoptera, Sesiidae). Zootaxa 4446(4):596–600. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4446.4.11.

- Quicke DLJ, Skowron Volponi MA, Kitching IJ, Butcher BA, Giudici A. 2018. Scientific note: First record of the remarkable clearwing moth, Akaisphecia melanopuncta O. Gorbunov & Arita, 1995 (Sesiidae: Sesiinae: Osminiini), from Thailand, with comments on likely Batesian mimicry. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology 21:490–492. DOI: 10.1016/j.aspen.2018.02.002.

- Robinson GS, Tuck KR, Shaffer M. 1994. A field guide to the smaller moths of South-East Asia. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Nature Society.

- Rothschild, W. 1912. New Bornean Aegeriidae and Syntomidae. Novitates Zoologicae 19:122. Sep.

- Sáfián S, Pühringer F. 2016. New records of Similipepsis ekisi Wang, 1984 (Lepidoptera: Sesiidae) from Liberia, West Africa, and notes on its mud-puddling behaviour. Metamorphosis Lepidopterists’ Society of Africa 27:1–2. Jan.

- Skowron Volponi M. 2019. A new species of spectacular spider wasp mimic from Thailand is the first representative of the genus Melanosphecia Le Cerf 1916 (Lepidoptera: Sesiidae: Osminiini) to be filmed in the wild. Zootaxa 4695(3):295–300. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4695.3.4.

- Skowron Volponi M. 2020. A vivid orange new genus and species of braconid-mimicking clearwing moth (Lepidoptera: Sesiidae) found puddling on Plecoptera exuviae. Insects 11:425. DOI: 10.3390/insects11070425.

- Skowron Volponi M, Casacci LP, Volponi P, Barbero F. 2021. Southeast Asian clearwing moths buzz like their model bees. Frontiers in Zoology 18(1). DOI: 10.1186/s12983-021-00419-8.

- Skowron Volponi MA, McLean DJ, Volponi P, Dudley R. 2018. Moving like a model: Mimicry of hymenopteran flight trajectories by clearwing moths of Southeast Asian rainforests. Biology Letters 14:20180152. DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2018.0152.

- Skowron Volponi M, Volponi P. 2017a. A new species of wasp-mimicking clearwing moth from Peninsular Malaysia with DNA barcode and behavioural notes (Lepidoptera, Sesiidae). ZooKeys 692(692):129–139. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.692.13587.

- Skowron Volponi MA, Volponi P. 2017b. A 130-year-old specimen brought back to life: A lost species of bee-mimicking clearwing moth, Heterosphecia tawonoides (Lepidoptera: Sesiidae: Osminiini), rediscovered in Peninsular Malaysia’s primary rainforest. Tropical Conservation Science 10:194008291773977. DOI: 10.1177/1940082917739774.

- Skowron Volponi MA, Volponi P. 2018. A new species of bee-mimicking clearwing moth (Lepidoptera: Sesiidae) from Thailand, with description and video of its behaviour. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology 21(1):279–282. DOI: 10.1016/j.aspen.2017.12.007.

- Skowron MA, Munisamy B, Hamid SB, Węgrzyn G. 2015. A new species of clearwing moth (Lepidoptera: Sesiidae: Osminiini) from Peninsular Malaysia, exhibiting bee-like morphology and behaviour. Zootaxa 4032(4):426–434. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4032.4.7.

- Walker AA, Weirauch C, Fry BG, King GF. 2016. Venoms of heteropteran insects: A treasure trove of diverse pharmacological toolkits. Toxins 8(2):1–32. DOI: 10.3390/TOXINS8020043.

- Woodruff DS. 2003. Neogene marine transgressions, palaeogeography and biogeographic transitions on the Thai-Malay Peninsula. Journal of Biogeography 30:551–567. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2003.00846.x.