Abstract

Black kites of the nominal subspecies Milvus migrans migrans breed in Europe and winter regularly in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. As a new phenomenon, black kites with morphological characteristics of the subspecies Milvus migrans lineatus are observed in Europe. Based on observations of black kites in winter 2020/2021 summarized in this paper, based on other recent reports about wintering black kites in Europe and based on juvenile black kite tagged on Crete and tracked for two years, we conclude that hundreds to thousands of black kites are now regularly wintering in south of Europe, and in smaller numbers in other parts of Europe as well as in northern Africa. The growing number of wintering black kites in Europe is apparently caused by members of the population from a hybrid zone between M. m. migrans and M. m. lineatus breeding east of the Urals, i.e. from the area of the European part of Russia. This is consistent with the hypothesis of the spreading of M. m. lineatus and a subsequent hybridization zone between M. m. migrans and M. m. lineatus in a westerly direction from Siberia across continental Europe. Moreover, two black kites found dead on Crete were attributed to M. m. lineatus and M. m. migrans by cytochrome B gene sequence analyses. The juvenile black kite with lineatus features tagged on Crete and telemetrically tracked during the next two years moved to the south-western part of Russia during the next two summers, but did not breed. It spent the following two winters at the same landfill in south-western Turkey. It seems that an adaptation to food sources provided by municipal waste landfills is important for black kites wintering in Europe, the Middle East and Morocco.

Highlights

• Hundreds to thousands of black kites are now regularly wintering in Europe.

• The growing number of wintering black kites is caused by birds from a hybrid zone between Milvus migrans migrans and M. m. lineatus in eastern Europe.

• Municipal waste landfills are important as food sources for black kites wintering in Europe.

Introduction

Black kites of the nominal subspecies Milvus migrans migrans (Boddaert 1783) (western black kite) breed in Europe and winter regularly in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East (Ferguson-Lees & Christie Citation2001; Panuccio et al. Citation2013; Literák et al. Citation2020; Ovčiariková et al. Citation2020). As a new phenomenon, black kites with morphological characteristics of the subspecies Milvus migrans lineatus J. E. Gray, 1831 (black-eared kite) are observed in Europe, especially during the winter months (Ferguson-Lees & Christie Citation2001; Kralj & Barišić Citation2013; Forsman Citation2016; Skyrpan & Literák Citation2019; Skyrpan et al. Citation2021). Firstly, Corso (Citation2002) published observations of black kites with lineatus features (now referred to as eastern black kites) in Italy at the Strait of Messina. Black kites with lineatus features were lately observed in Zagreb, Croatia, and in Zhornyska, Lviv Region, Ukraine (Kralj & Barišić Citation2013; Skyrpan and Literak Citation2019). Dozens of black kites with lineatus features were observed wintering on Crete in January 2020 (Panter et al. Citation2020). Forsman (Citation2016) mentioned that black kites with features of lineatus have increased in Europe during the past two decades. In recent years, there has been a substantial increase in the number of sightings of black kites with lineatus features in the whole Europe (Skyrpan et al. Citation2021). Furthermore, it appears that the emergence of black kites with lineatus features in Europe coincides with a number of observations of wintering black kites in Georgia, Turkey, and the whole of southern Europe (Sunyer & Viñuela Citation1996; Tsvelykh & Panyushkin Citation2002; Sarà Citation2003; Biricik & Karakaș Citation2011; Molina et al. Citation2012; Palomino et al. Citation2012; Abuladze Citation2013; Mayordomo et al. Citation2015; Literák et al. Citation2017; Panter et al. Citation2020; Skyrpan et al. Citation2021).

Hybrids between M. m. migrans and M. m. lineatus are featured in a review of avian hybrids throughout the world (McCarthy Citation2006) based on weak references from Sibley and Monroe (Citation1990). Forsman (Citation2003, Citation2016) stated that a typical adult lineatus is easily distinguished from a typical adult migrans; however, a great deal of overlap in morphological characteristics is present between these two subspecies. All black kites with lineatus features in Europe should be considered hybrids between M. m. migrans and M. m. lineatus, as pure M. m. lineatus individuals only occur in east Siberia and Japan (Andreyenkova et al. Citation2021). Previous research has determined the western Siberian black kite population to more or less comprise migrans × lineatus hybrid birds (Stepanyan Citation1990; Karyakin Citation2017). The westward expansion of M. m. lineatus has increased since the 1990s owing to a drop in the numbers of M. m. migrans, with lineatus features apparently rapidly introgressing the European subspecies over the vast territory between Altai and the Urals (Karyakin Citation2017; Andreyenkova et al. Citation2021). A recent increase in the number of sightings of black kites with morphological features of lineatus in Europe suggests the spreading of M. m. lineatus and a subsequent hybridization zone between M. m. migrans and M. m. lineatus in a westerly direction from Siberia across continental Europe (Skyrpan et al. Citation2021).

The aim of this study, following recent works on the increasing number of wintering black kites in Europe (Literák et al. Citation2017; Panter et al. Citation2020; Skyrpan et al. Citation2021), is: (a) to estimate the total number of wintering kites in Europe at present and to define the areas with the highest density of wintering kites; (b) to characterize their subspecies status; and (c) using data from a telemetrically tracked black kite having some features of M. m. lineatus wintering on Crete and in Turkey, to characterize the behavioural ecology of this bird during wintering and during the following summer period.

Material and methods

Period of black kite wintering in Europe

Based on data from the autumn and spring migrations of M. m. migrans reviewed in detail by Panuccio et al. (Citation2013) and newly summarized for key flyways of black kites between Europe and Africa in the Strait of Gibraltar, Spain; Batumi, Georgia; and Northern Valleys, Israel, by Onrubia and Martín (Citation2021), we consider all observations of black kites in the period from November until January as observations of wintering birds out of the migration period of M. m. migrans.

Direct field observations and data from open-access bird observation databases

Records from open-access observation databases that included observations of black kites covering winter 2020/2021 were sourced from the following websites: https://www.artsobservasjoner.no; www.birdguides.com; https://birding.sk; www.birding.hu; www.birding.nl; www.clanga.com; https://ebird.org; https://netfugl.dk; https://ubird.ebitalia.it; https://www.ornitho.de; https://www.ornitho.it; www.rarebirdalert.co.uk; https://www.tarsiger.com; www.faune-france.org; www.birds.cz; www.waarneming.nl (accessed 31 March 2021). Collection of data from web databases was done by checking records on mentioned web pages every week, and specific data were recorded: date, geographical position (GPS coordinates), number of birds observed, author of the observation, and other details if the author provided them.

Black kites winter in small numbers in the Czech Republic and Slovakia and use communal roosting places with red kites (Milvus milvus) (Literák et al. Citation2019). In the Czech Republic and Slovakia, a regular census of the number of wintering red kites has been organized at communal roosting places. In our study, black kites observed at communal roosting places of red kites were recorded in the Czech Republic and Slovakia in the period from December 2020 to February 2021.

In some cases, black kite sightings in the surveyed databases were supplemented by photo documentation. In this photo documentation, we evaluated cases of birds in which it was possible to find morphological features of the subspecies lineatus. To create an overview of wintering birds with lineatus features, we used also records of these birds published recently in Skyrpan et al. (Citation2021). Finally, we also used reports of black kites with lineatus features from winter 2019/2020 and 2021/2022, which were sent directly to us by local field ornithologists.

All data of black kites wintering in Europe and the northern coast of Africa were processed and visualized using ArcGIS Pro (Esri, Redlands, CA, USA) and QGIS (www.qgis.org) geographic information software packages.

Telemetry tracking

Over a three-day period in January 2020, 157 kites were recorded at the surveyed landfill sites on Crete, Greece (Panter et al. Citation2020). Some 68 black kites, many of which had features of M. m. lineatus, two red kites (Milvus milvus) and a hybrid red kite × black kite were observed in Arkadi landfill. About two months later, on 2 April 2020, dozens of birds of various species were found to have died suddenly at the Arkadi landfill. They were poisoned by a toxic substance that travelled from the landfill to the birds’ water source. The affected birds became immobile and died in convulsions (https://www.rethemnosnews.gr/rethymno/631408_xafnikos-thanatos-gia-dekades-agria-poylia-gyro-apo-ton-hyta-amarioy, accessed 30 April 2021). Some birds, including one black kite, were rescued. This rescued juvenile black kite (2cy) was fitted with a 20 g OrniTrack-20 (solar powered GPS-GSM/GPRS tracker, Ornitela, Lithuania, www.ornitela.com) on 10 April 2020 and released back in the wild. As this bird had some features of M. m. lineatus (pale/bluish cere and legs, and pronounced dark eye mask), we supposed it to be a black kite originating from a hybrid zone between M. m. migrans and M. m. lineatus (). The bird was tracked until 8 January 2022 when the logger apparently failed and no more data were transmitted.

Figure 1. Black kite tagged on Crete on 10 April 2020. As this bird had some features of Milvus m. lineatus (pale/bluish cere and legs, and pronounced dark eye mask), we supposed it to be a black kite originating from a hybrid zone between M. m. migrans and M. m. lineatus.

The logger was fitted to the bird’s back using wing harnesses consisting of two loops of 6 mm Teflon ribbon that encircled the body around the base of the wings and joined in front of the breastbone (Thaxler et al. Citation2014). GPS positions were collected usually as one position fixed per 15 min. and sent as text messages by local mobile operators to Ornitela Centre in Lithuania where they were saved and archived. The obtained dataset was then analysed using ArcGIS Pro and QGIS.

Wintering, migration and stopovers

Spring and autumn migrations are part of annual movements that separate the winter and summer periods. We describe the beginning of those migrations as a day when a bird left the winter/summer area and flew north/south without returning in consecutive days. The end is defined as a day when a bird reached the summer or winter destination without continuing on its migration to the north or south. During both migrations, birds tend to use stopovers, defined as a day with less than 50 km of a directed flight (Literák et al. Citation2022). Winter home range sizes were calculated using the 95% kernel density estimate (KDE95) from locations obtained during winter period. To analyse the area requirements, we calculated KDE for each winter separately. To visualize the wintering of the tagged bird in Turkey, we used cumulative KDE95 values calculated from positions obtained during the second and third winters, for simplicity, as the bird used the same areas in an identical manner during its second and third winter. In this study, we did not calculate the size of a summer home range. To analyse the location of night roosts, we selected one last recorded location from each day (at 20 – 22 h.; UTC+3; Coordinated Universal Time). To compare the latitude of winter and summer areas used by the tagged bird between years of its life span, we defined checkpoints W1, W2, W3 and S1, S2 as night positions where the bird stayed on 31 January and 30 June, respectively, in subsequent years after tagging.

Mitochondrial cytochrome b gene (CytB) haplotype

Two black kites found dead on Crete were examined for their CytB haplotype. Black kite 1 was found in Vagionia (coordinates 35°00´ N, 24°59´ E) on 20 October 2020, black kite 2 was found in Amari landfill (35°17´ N, 24°38´ E) on 23 February 2021. Their tissue samples were stored in 96% ethanol. DNA was isolated using the Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Tissue) (Geneaid, Taiwan). The primers used for the amplification of the 924-bp CytB mitochondrial gene fragment were: F3 (5′-CCACCCCATCCTCAAAATAA-3′) and R8 (5′-ATTGTGCGCTGTTTGGACTT-3′) (Andreyenkova et al. (Citation2021). The thermal protocol consisted of an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 30 sec), annealing (60°C, 30 sec) and DNA extension (72°C, 40 sec), and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. Polymerase chain reaction fragments were sequenced in both directions by Macrogene Europe BV (The Netherlands). The haplotypes were determined by comparing the resulting sequences with the haplotype dataset (GenBank Accession Numbers MT024189–MT024234, Andreyenkova et al. Citation2021) using free software MEGA 7 (University of Kent, UK, https://www.kent.ac.uk/software/mega-7).

Results

Number of black kites wintering in 2020/2021 in Europe and Morocco

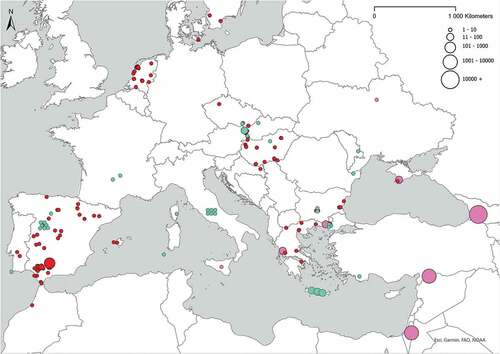

By direct observation or using databases, we registered 1104 observations of black kites in 228 reports in the period from 1 November 2020 to 31 January 2021 (Supplemental material Table S1; ). The distribution of observations was uneven both geographically and temporally. Most observations related to the Iberian Peninsula. Smaller numbers of observations were made in the south of France, in the Netherlands, in central and south-eastern Europe and in Morocco. Observations were rare in northern Europe (southern Sweden). A total of 400 birds, the largest number recorded at one time in one location, were recorded in Spain near the city of Córdoba on 14 November 2020. Dozens of wintering birds were observed at other Spanish locations in November 2020 and January 2021. Total numbers of observations of black kites in November and December 2020, and January 2021, were 734 (72 reports), 88 (80 reports), and 282 (76 reports), respectively.

Figure 2. Black kites wintering in Europe – numbers and distribution according to data from open-access bird observation databases and personal observations from winter 2020/2021 (this work) (red circles – subspecies status undetermined; green circles – observations of black kites with lineatus features), data from previously published papers (Shirihai et al. Citation2000; Tsvelykh and Panjushkin Citation2002; Sarà M. Citation2003; Domashevsky Citation2009; Biricik & Karakaș Citation2011; Abuladze Citation2013; Literák et al. Citation2017) (rose circles – subspecies status undetermined), and data from a recent paper depicting observations of black kites with lineatus features (Panter et al. Citation2020; Skyrpan et al. Citation2021) and four further observations of black kites with lineatus features (see ) (green circles). The cluster of circles in Italy does not represent true positions but the occurrence of wintering black kites in Italy, because exact locations were not available in www.ornitho.it.

Subspecies status of black kites wintering in Europe

From photographically documented observations from the winter of 2020/2021, we found black kites with lineatus features in 19 cases (Supplemental material, Table S1; ). An overview of observations of black kites with lineatus features in Europe in winters (each winter from November to January) from 1 May 2005 to 3 April 2020 (Skyrpan et al. Citation2021) shows 23 observations from the Iberian Peninsula, and from central and south-eastern Europe. A total of 153 black kites with morphological features of both subspecies (M. m. migrans and M. m. lineatus) were observed on Crete from 19 to 21 January 2020 (Panter et al. Citation2020). Another four observations of black kites with lineatus features, recorded in winter 2019/2020 and 2021/2022, are listed in . Two black kites found dead on Crete belonged to CytB haplotypes B6 (black kite 1) and A4 (black kite 2) attributed to M. m. lineatus and M. m. migrans, respectively.

Table I. Observations of black kites with lineatus features in winters 2019/2020 and 2021/2022 (observations from winter 2019/2020 are not included in the paper by Skyrpan et al. Citation2021).

Telemetry tracking of a tagged black kite

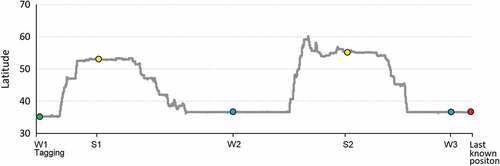

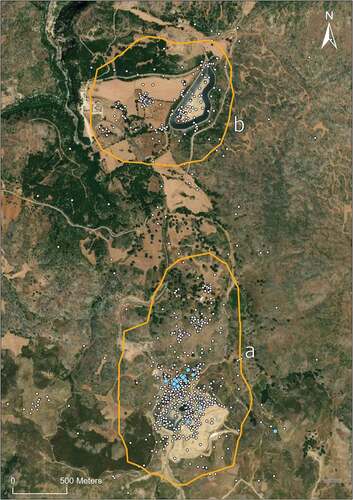

Beside direct observations and data obtained from online databases, we tagged one rescued black kite with features of M. m. lineatus on Crete, which we monitored from 10 April 2020 to 8 January 2022 (). After tagging and release, the bird stayed on Crete where it dwelled and roosted mainly near a landfill and close to a small artificial water reservoir (; ). It used a relatively small area of only 3.2 km2 (kernel density estimate 95%). On 15 May 2020, it began its spring migration to its summer ground in western Russia near Bryansk (; ).

Table II. Characteristics of winter grounds used by tagged black kite in years 2020 to 2022. W1, winter 2019/2020; W2, winter 2020/2021; W3, winter 2021/2022; * date of tagging; † date of last observation; Area, home range calculated as 95% kernel density estimate, see also ; Areas labelled ‘a’ represent landfills.

Table III. Characteristics of spring migrations (SM) and autumn migrations (AM) of tagged black kite during 2020 and 2021.

Figure 4. Migration routes, winter and summer areas of black kite tagged on Crete. Black dots represent stopovers. The green dot represents the place of tagging and winter area used in 2020. Yellow dots represent summer areas: S1 – 2020, S2 – 2021. The blue dot represents the winter area used in 2020/2021 and 2021/2022.

Figure 5. Latitudinal occurrences of tracked black kite throughout its lifespan. W1 refers to place of tagging and first winter location. W2 and W3 refer to the location of birds on 31 January 2021 and 2022, respectively; S1, S2 and refer to the location of birds on 30 June in 2020 and 2021.

Figure 6. Roosting and foraging areas used by tagged black kite on Crete. White dots represent all recorded positions, Blue dots refer to night roosts. The orange polygon represents the home range estimate as kernel density estimate 95%, a – landfill, b – small artificial water reservoir.

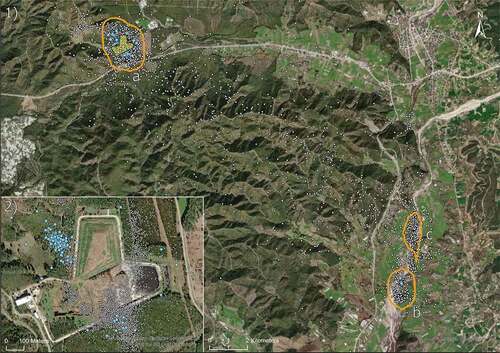

After the summer period, the tagged bird began its longest autumn migration, lasting 79 days with six stopovers, where it stopped for 46 days (). In comparison to the previous winter, it changed its destination and flew to winter in south-west Turkey, where it again dwelled and roosted near an area of another landfill, while regularly staying also near Koca Çay River (). During wintering in Turkey, it occupied a small area of 3.0 km2 and roosted exclusively in the vicinity of the landfill (). The next summer, the bird again changed its destination. It flew over 600 km farther north than in the previous year and spent the summer near Volokolamsk, Russia ().

Figure 7. Roosting and foraging areas used by tagged black kite in Turkey during winter 2020/2021 and 2021/2022. White dots represent all recorded positions. Blue dots refer to night roosts. The orange polygon represents the home range estimate as kernel density estimate 95%. The yellow polygon highlights the location of the landfill in 1) which is visible in detail in 2), a – landfill, b – and c – Koca Çay River.

On 3 September 2021, the bird left the summer ground and migrated to Turkey for the winter (), where it used the same place as the previous winter, in an identical manner. It used an area of 3.6 km2 and roosted mainly in the vicinity of the landfill while, again, also regularly staying near Koca Çay River. We received the last coordinates on 8 January 2022, while the bird was wintering in Turkey for the second time. The cause of the loss of signal remains unknown.

Discussion

Growing number of black kites wintering in Europe

Recently, black kites have commonly wintered in Spain, and sometimes dozens to hundreds of black kites have been observed in winter foraging on landfills (Molina et al. Citation2012; Palomino Citation2012; Mayordomo et al. Citation2015). It seems that wintering of black kites in Spain is now much more common than previously (Franco & Amores Citation1980; Sunyer & Viñuela Citation1996). Similarly, in Portugal, the occurrence of black kites in December and January formerly was considered very rare (Catry et al. Citation2010). Even if black kites were observed to winter in continental Greece in the past (Makatsch Citation1948), it seems that the dozens of wintering black kites in Greece represent a new phenomenon (Literák et al. Citation2017). During a study made by car transects in January 2009 and January 2010, a total of eight black kites were reported, one in Sicily and seven in Crete (Panuccio et al. Citation2019) Winter observations of black kites were rare in the tripoint border area of Austria, Czech Republic, and Slovakia until the year 2000, but from winter 1997/1998 black kites have wintered regularly in this area (Literák et al. Citation2017). In Switzerland, wintering black kites had been unknown until 2002/2003, when for the first time a black kite was recorded near Bern (Hans Schmid, Swiss Ornithological Institute, personal communication). Observations of wintering black kites in France, too, have been less rare in recent years. For example, 11 and six black kites, respectively, were registered during the January 2016 and January 2017 census of red kites (Fabienne David and Aurélie de Seynes, French Red Kite Network, personal communication). The process of black kite colonization in Sicily has been well documented (Sarà Citation2003; Panuccio et al. Citation2019). Moreover, six black kites apparently wintering were observed at the landfill near San Brancato (40°13´N, 16°17´E) in southern Italy, on 14 March 2017 (Rainer Raab, personal communication). No wintering black kites had been observed in Croatia in the past (Tutiš et al. Citation2013). Wintering black kites were firstly observed in the north-eastern part of Croatia in the winters 2014/2015 and 2015/2016, both seasons at the same location in Jagodnjak (45°42´N, 18°34´E) (Ivan Literák, Hynek Matušík, Lubomír Peške, Radim Petro, unpubl. data). Some black kites have in the past overwintered in Bulgaria, but the number of winter records increased after 2000 (Patev Citation1950; Kumerloeve Citation1956; Baumgart Citation1971; Simeonov et al. Citation1990; Golemanski et al. Citation2011). In Ukraine, wintering black kites have been observed since 1998 and their number rose to as many as 70 birds in the Danube Delta and Southern Crimea, where they often use communal landfills for foraging (Tsvelykh and Panjuskhin Citation2002; Domashevsky Citation2009). These observations coincided in time with observations of wintering black kites in Hungary, where the birds were seen individually wintering during the period 2010–2016 (László Haraszthy, personal communication). Black kites winter regularly but in small numbers also in the south of the European part of Russia (Melnikov & Sokolov Citation2020).

Based on observations in winter 2020/2021, summarized in this paper, and based on recent reports, which document dozens or hundreds of wintering black kites in Spain and Greece (Molina et al. Citation2012; Literák et al. Citation2017; Panter et al. Citation2020), and based on further European data referenced above, we can conclude that hundreds to thousands of black kites are now regularly wintering in southern Europe, and a smaller number of black kites winter commonly in other parts of Europe as well as in northern Africa.

These wintering areas now appear to be seamlessly following the wintering areas of black kites in Georgia, Turkey, and Israel, where tens of thousands of black kites winter (Shirihai et al. Citation2000; Abuladze et al. Citation2011; Biricik & Karakaș Citation2011; Abuladze Citation2013) (). Black kites always were by far the most numerous wintering raptor species in Georgia, with 3000 to 12,000 individuals wintering in this country (Abuladze et al. Citation2011; Abuladze Citation2013). Formerly, black kites were characterized as sporadically wintering in Turkey, and there were records from all regions of Turkey (Kirwan et al. Citation2008). Recently, a common wintering of black kites was described in south-eastern Anatolia, Turkey, from 2001 to 2010 (Biricik & Karakaș Citation2011). Most of them were recorded at landfills where household garbage was deposited, and around slaughterhouses where various parts of slaughtered animals were available. In December 2007, more than 1200 (the highest number counted) black kites wintered near Gaziantep-Oğuzeli. It was estimated that at least 7500 black kites wintered in the area during 2011. Previously, only exceptionally had wintering black kites been observed in the Middle East including Turkey, Syria, and Lebanon. Common observations of wintering black kites in Israel that are in contrast to the past, and some recent observations of wintering black kites in Egypt as well as in Morocco, lend support to this idea (Kumerloeve Citation1967; Shirahai et al. Citation2000; Ciach and Kruszyk (Citation2010, Citation2017).

Subspecies status of black kites wintering in Europe

When observing dozens of wintering black kites in mainland Greece during winters 2002/2003, 2015/2016 and 2016/2017, as no attention was paid to the subspecies status, the observed black kites were considered to belong to the nominal subspecies M. m. migrans (Literák et al. Citation2017). It was only discovered later, during further studies, that black kites with morphological features of M. m. lineatus, and therefore birds originating from the hybrid zone of M. m. migrans × M. m. lineatus, winter in Europe (Panter et al. Citation2020; Skyrpan et al. Citation2021). A number of wintering black kites with features of lineatus were observed from 2007 to 2020 throughout Europe, in areas including Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Austria, Czech Republic, Bulgaria and Romania (Skyrpan et al. Citation2021). Moreover, dozens of black kites with morphological features of M. m. lineatus were recorded at the surveyed landfills on Crete in January 2020 (Panter et al. Citation2020). The newly observed black kites wintering in Europe and Turkey prefer lowland habitats near water bodies and use landfills as a source of food (Tsvelykh & Panyushkin Citation2002; Biricik & Karakaș Citation2011; Molina et al. Citation2012; Literák et al. Citation2017; Panter et al. Citation2020) which is typical for black kites from the hybrid zone between M. m. migrans × M. m. lineatus or for pure M. m. lineatus originating from Siberia and wintering on the Indian subcontinent (Kumar et al. Citation2020; Literák et al. Citation2022). The black kite wintering population has increased dramatically in the northern Negev region of Israel over the past two decades, due to using landfills as reliable food source (Berkowitz et al. Citation2018). Unfortunately, the subspecies status was not determined for many black kites observed at a municipal landfill in Rome (De Giacomo & Guerrieri Citation2008).

A number of black kites apparently belonging to M. m. migrans were tagged in Europe in a breeding season and later tracked to reveal their migration/dispersal strategy (Sergio et al. Citation2014; Ovčiariková et al. Citation2020). We did not find any note/case of these tagged black kites wintering in Europe; rather, they all wintered in sub-Saharan Africa. Some of them stayed in Africa longer in the period of their first or even second year, and they usually bred in Europe when they were 3–6 years old (Sergio et al. Citation2014; Ovčiariková et al. Citation2020).

We can conclude that the growing number of wintering black kites in Europe is basically caused by members of the population from a hybrid zone between M. m. migrans × M. m. lineatus breeding in eastern Europe east of the Urals, i.e. more or less from the area of the European part of Russia. This conclusion is supported by the finding of a dead black kite on Crete, which we showed to possess the CytB haplotype B6. Haplotype B6 belongs to the haplogroup B, which has been recently attributed to M. m. lineatus (Andreyenkova et al. Citation2021).

Pure black kites Milvus m. migrans breeding in Europe from the Iberian Peninsula to eastern Ukraine still winter in sub-Saharan Africa (Sergio et al. Citation2014; Ovčiariková et al. Citation2020; Literák et al. Citation2021). Hence, our study does not seem to support a previous idea that a growing number of wintering black kites (considered M. m. migrans) in Europe coincides with climate warming in Europe and with negative changes in sub-Saharan Africa (e.g. an increasing density of human population and extensive use of pesticides in Africa), even if it was reported that the breeding behaviour of black kites (Milvus m. migrans) in Italy responded quickly to climate warming, and despite the fact that aerial and ground spraying of insecticides in Africa often wipes out the food resource of black kites and indirectly kills many individuals (Sergio Citation2003; Panuccio et al. Citation2013; Literák et al. Citation2017).

According to current estimates, 28,000–270,000 pairs of black kites nest in the European part of Russia, which allegedly represents 35–45% of black kites nesting in the whole of Europe (Melnikov & Sokolov Citation2020). The subspecies status of these birds remains unclear, but it can be expected that from the east (the Urals) to the western border of Russia, the proportion of birds in the hybrid population will decrease (see also Andreyenkova et al. Citation2021).

Life history of the tracked black kite with lineatus features

We tagged the black kite with features of M. m. lineatus that was rescued while wintering in Crete. Here, the bird dwelled most of the time in the vicinity of a landfill and water body, where it roosted and foraged. Identical behaviour was observed even when the bird changed its destination, wintering in Turkey in following two winters. Such behaviour has been recently observed in many black kites with morphological features of M. m. lineatus (Literák et al. Citation2017; Panter et al. Citation2020).

An adult black kite with lineatus features was captured, ringed, and tagged at the Dudaim landfill near Be’er Sheva in southern Israel (Daniel Berkowitz, personal communication). This bird was later observed at a landfill near the village of Nema in the Kirov Region (the European part of Russia west of the Urals) (Karyakin et al. Citation2018). These findings underline the role of landfills as roosting and foraging places for black kites with features of lineatus. Six recoveries of ringed black kites published recently show a connection between black kites originating from the European part of Russia and those wintering in Israel (Franks et al. Citation2022). We suppose these ringed black kites originated from the same hybrid zone between M. m. migrans × M. m. lineatus as did our tagged bird.

Black kites breeding in Europe, supposedly pure M. m. migrans, migrate through different corridors to reach their winter ground in sub-Saharan Africa (Sergio et al. Citation2014; Ovčiariková et al. Citation2020; Literák et al. Citation2021). Birds from Spain migrate though the Strait of Gibraltar to winter in north-west Africa (Sergio et al. Citation2014). Birds from central Europe migrate through various corridors and some birds cross through Greek islands or Turkey on their autumn migration, but do not stop there and continue south to winter in Africa (Lucia et al. Citation2011; Ovčiariková et al. Citation2020). Our bird chose the corridor following the west coast of the Black Sea during all its migrations to and from Turkey.

During the first year of monitoring it spent a summer in lower latitudes then in the following summer. A similar movement pattern was observed in black kites M. m. migrants originating from the population in central Europe, where young birds left their natal area and flew to winter in Africa (Ovčiariková et al. Citation2020). In subsequent years, birds tended to spend summer closer to the natal area until they reached maturity and spent the summer period back in their natal area. Such behaviour has also been described in other raptors, such as the short-toed snake eagle Circaetus gallicus and the European honey buzzard Pernis apivorus, migrating from Europe to Africa and back (Mellone et al. Citation2011; Vansteelant Citation2019). Interestingly, different behaviour was observed in black kites originating from Siberia, where the birds tend to spend each summer period at a similar latitude to their natal area (Literák et al. Citation2022).

Based on the ecology of black kites from different areas, and the tagged bird’s choice of migration corridor, to reach the winter and summer destination, we can assume it originated in the area of western Russia near Volokolamsk or possibly even from farther north near Cherepovets, as the bird visited this area on its last spring migration before spending the summer in Volokolamsk. Since black kites rarely migrate alone during autumn migration, we can assume that more birds from those areas are choosing Crete or Turkey as their winter destination (Panuccio et al. Citation2013). In contrast, black kites that migrate through Georgia around the eastern coast of the Black Sea to winter in Israel might originate from more eastern parts of European Russia (Panuccio et al. Citation2013; Karyakin et al. Citation2018). Such findings may reveal the origin of the increasing numbers of black kites wintering in southern Europe and present further evidence of the westward shift and expansion of the hybridization zone between M. m. migrans × M. m. lineatus (Skyrpan et al. Citation2021).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (28 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank all observers who provided records of wintering black kites, personally or through open-access bird observation databases. We thank Afroditi Kardamaki for black kite tissue samples from the collection of the Natural History Museum of Crete.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/24750263.2022.2137253

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abuladze A. 2013. Materials towards a fauna of Georgia, issue VI. birds of pray of Georgia. Tbilisi: Institute of Zoology and Ilia State University.

- Abuladze A, Kandaurov A, Edisherashvili G, Eligulaashvili B. 2011. Wintering of raptors in Georgia: Results of long-term monitoring. In Proceedings of International Conference “The Birds of Pray and Owls of Caucasus”, 26–29 October 2011, Tbilisi, Abastumani, Georgia.

- Andreyenkova NG, Karyakin IV, Starikova IJ, Sauer-Gürth H, Literák I, Andeyenkov OV, Shnayder EP, Bekmansurov RH, Alexyenko MN, Wink M, Zhimulev IF. 2021. Phylogeography and demographic history of the black kite Milvus migrans, a widespread raptor in Eurasia, Australia and Africa. Journal of Avian Biology 52:e02822. DOI: 10.1111/jav.02822.

- Baumgart W. 1971. Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Greifvögel Bulgariens. Beitrage zur Vogelkunde 17:33–70.

- Berkowitz D, Dor R, Leshem Y, Sapir N. 2018. The movement ecology of over-wintering Black Kite (Milvus migrans) in Israel with implications for aircraft collision risks. In Symposia Abstracts, 27th International Ornithological Congress, Vancouver.

- Biricik M, Karakaș R. 2011. Black Kites (Milvus migrans) winter in southeastern Anatolia, Turkey. Journal of Raptor Research 45:370–373. DOI: 10.3356/JRR-10-109.1.

- Catry P, Costa H, Elias G, Matias R. 2010. Aves de Portugal – Ornitologia do Território Continental. Lisbon: Assírio and Alvim.

- Ciach M, Kruszyk R. 2010. Foraging of white storks Ciconia ciconia on rubbish dumps on non-breeding grounds. Waterbirds 33:101–104. DOI:10.1675/063.033.0112.

- Corso A. 2002. Separation of Black Kite from Red Kite: The pitfall of the eastern form and rufous variants. Birding World 15:248–252.

- De Giacomo U, Guerrieri G. 2008. The feeding behaviour of the Black Kite (Milvus migrans) in the rubbish dump of Rome. Journal of Raptor Research 42:110–118. DOI:10.3356/JRR-07-09.1.

- Domashevsky SV. 2009. Pervaya registraciya chernogo korshuna v zimniy period na severe Ukrainy (First record of the Black Kite in winter in the northern part of Ukraine). Berkut 18:212–213. (In Russian with English summary).

- Ferguson-Lees J, Christie DA. 2001. Raptors of the world. Helm identification guides. London, UK: Christopher Helm.

- Forsman D. 2003. Identifcation of Black-eared Kite. Bird World 16:156–216.

- Forsman D. 2016. Flight identification of raptors of Europe. North Africa and the Middle East. London: Christopher Helm.

- Franco A, Amores F. 1980. Observación invernal de Milvus migrans en la Península Ibérica. Acta Vertebrata (Doñana) 7:266.

- Franks S, Fiedler W, Arizaga J, Jiguet F, Nikolov B, van der Jeugd H, Ambrosini R, Aizpurua O, Bairlein F, Clark J, Fattorini N, Hammond M, Higgins D, Levering H, Skellorn W, Spina F, Thorup K, Walker J, Woodward I, Baillie SR. 2022. Online atlas of the movements of Eurasian-African bird populations. EURING/CMS. https://migrationatlas.org Accessed May 2022 27.

- Golemanski V et al., editors. 2011. Red Data Book of the Republic of Bulgaria. Volume 2. Animals. Sofia: IBEI – BAS & MOEW.

- Karyakin I. 2017. Problem of identification of Eurasian subspecies of the Black Kite and records of the Pariah Kite in southern Siberia, Russia. Raptors Conservation 34:49–67. DOI: 10.19074/1814-8654-2017-34-49-67.

- Karyakin IV, Nikolenko EG, Shnayder EP, Babushkin MV, Bekmansurov RH, Kitel DA, Pimenov VN, Pchelinsev VG, Khlopotova AV, Shershnev MY. 2018. Results of work of the Raptor Ringing Center of the Russian Raptor Research and Conservation Network in 2017. Raptors Conservation 37:15–48. DOI:10.19074/1814-8654-2018-37-15-48.

- Kirwan GM, Boyla KA, Castell P, Demirci B, Özen M, Welch H, Marlow T. 2008. The birds of Turkey. The distribution, taxonomy and breeding of Turkish birds. London: Christopher Helm.

- Kralj J, Barišić S. 2013. Rare birds in Croatia. Third report of the Croatians rarities committee. Natura Croatica 22:375–396.

- Kumar N, Gupta U, Jhala YV, Qureshi Q, Gosler A, Sergio F. 2020. GPS-telemetry unveils the regular high-elevation crossing of the Himalayan by a migratory raptor: Implications for defnition of a “Central Asian Flyway”. Scientific Reports 10:15988. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-72970-z.

- Kumerloeve H. 1956. Der Schwarzmilan als Wintergast in Bulgarien. Vogelwelt 77:2.

- Kumerloeve H. 1967. Vom Überwintern des Schwarzmilan in Vorderen Orient. Falke 14:274–275.

- Literák I, Balla M, Vyhnal S, Škrábal J, Peške L, Chrašč P, Systad G. 2020. Natal dispersal of Black Kites from Slovakia. Biologia 75:591–598. DOI: 10.2478/s11756-019-00323-x.

- Literák I, Horal D, Alivizatos H, Matušík H. 2017. Common wintering of black kites (Milvus migrans migrans) in Greece, and new data on their wintering elsewhere in Europe. Slovak Raptor Journal 11:91–102. DOI: 10.1515/srj-2017-0001.

- Literák I, Horal D, Raab R, Matušík H, Vyhnal S, Rymešová D, Spakovszky P, Skartsi T, Poirazidis K, Zakkak S, Tomik A, Skyrpan M. 2019. Sympatric wintering of red kites and black kites in south-east Europe. Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 65:381–398. DOI: 10.17109/AZH.65.4.381.2019.

- Literák I, Ovčiariková S, Škrábal J, Matušík H, Raab R, Spakovszky P, Vysochin M, Tamás EA, Kalocsa B. 2021. Weather-influenced water-crossing behaviour of black kites (Milvus migrans) during migration. Biológia 76:1267–1273. DOI: 10.2478/s11756-020-00643-3.

- Literák I, Škrábal J, Karyakin IV, Andreyenkova NG, Vazhov SV. 2022. Black Kites on a flyway between Western Siberia and the Indian Subcontinent. Scientific Reports 12:5581. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-09246-1.

- Lucia G, Agostini N, Panuccio M, Mellone U, Chiatante G, Tarini D, Evangelidis A. 2011. Raptor migration at Antikythira, in southern Greece. British Birds 104:266–270.

- Makatsch W. 1948. Der Schwarze Milan als Wintergast in Griechenland. Ornithologische Berichte 1:143–145.

- Mayordomo S, Prieta J, Cardalliaguet M. 2015. Aves de Extremadura, vol. 5, 2009–2014. https://birds-extremadura.blogspot.com. Accessed March 2022 16.

- McCarthy EM. 2006. Handbook of avian hybrids of the world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mellone U, Yáñez B, Limiñana R, Muñoz AR, Pavón D, González JM, Urios V, Ferrer M. 2011. Summer staging areas of non-breeding Short-toed Snake Eagles Circaetus gallicus. British Birds 58:516–521.

- Melnikov VN, Sokolov AY. 2020. Chernyi korshun Milvus migrans Black Kite. In: Kalyakin MV, Voltzit OV, editors. Atlas of the breeding birds of European part of Russia. Moscow: Fiton XXI. pp. 172–174.

- Molina B, Prieta J, Lorenzo JA. 2012. Noticiario ornitológico [Ornithological rarities]. Ardeola 59:167–194. DOI:10.13157/arla.59.1.2012.167.

- Onrubia A, Martín B. 2021. Black Kite Milvus milvus. In: Pannucio M, Mellone U, Agostini N, editors. Migration strategies of birds of prey in Western Palearctic. Boca Raton, USA, Oxon, UK: CRC Press. pp. 165–179.

- Ovčiariková S, Škrábal J, Matušík H, Makoň K, Mráz J, Arkumarev V, Dobrev V, Raab R, Literák I. 2020. Natal dispersal in Black Kites Milvus migrans migrans in Europe. Journal of Ornithology 161:935–951. DOI: 10.1007/s10336-020-01780-x.

- Palomino D. 2012. Milano negro Milvus migrans. In: Del Moral JC, Molina B, Bermejo A, Palomino D, editors. SEO/BirdLife: Atlas de las aves en invierno en España 2007–2010. Madrid: Ministry of Agriculture, Food and the Environment, Spanish Ornithological Society/ BirdLife. pp. 162–163.

- Panter CT, Xirouchakis S, Danko Š, Matušík H, Podzemný P, Ovčiariková S, Literák I. 2020. Kites (Milvus spp.) wintering on Crete. The European Zoological Journal 87:591–596. DOI: 10.1080/24750263.2020.1821801.

- Panuccio M, Agostini N, Mellone U, Bogliani G. 2013. Circannual variation in movement patterns of the Black Kite (Milvus migrans migrans): A review. Ethology Ecology & Evolution 26:1–18. DOI: 10.1080/03949370.2013.812147.

- Panuccio M, Agostini N, Nelli L, Andreou G, Xirouchakis S. 2019. Factors shaping distribution and abundance of raptors wintering in two large Mediterranean islands. Community Ecology 20:93–103. DOI: 10.1556/168.2019.20.1.10.

- Patev P. 1950. Pticite v Balgarija (Birds of Bulgaria, in Bulgarian). Sofia: BAN Publishing.

- Sarà M. 2003. The colonization of Sicily by the Black Kite (Milvus migrans). Journal of Raptor Research 37:167–172.

- Sergio F. 2003. Relationship between laying dates of black kites Milvus migrans and spring temperatures in Italy: Rapid response to climate change? Journal of Avian Biology 34:144–149.

- Sergio F, Tanferna A, De Stephanis R, López Jiménez L, Blas J, Tavecchia G, Preatoni D, Hiraldo F. 2014. Individual improvements and selective mortality shape lifelong migratory performance. Nature 515:410–413. DOI:10.1038/nature13696.

- Shirihai H, Yosef R, Alon D, Kirwan GM, Spaar R. 2000. Raptor migration in Israel and the Middle East. Eilat: International Birdwatching Centre Eilat IBRCE, IOC, SPNI.

- Sibley CG, Monroe BL. 1990. Distribution and taxonomy of birds of the world. New Haven, USA: Yale University Press.

- Simeonov SD, Michev TM, Nankinov DN, editors. 1990. Fauna na Balgarija (Fauna of Bulgaria 20, Aves Vol. 1., in Bulgarian). Sofia: BAN Publishing.

- Skyrpan M, Literák I. 2019. A kite Milvus migrans migrans/lineatus in Ukraine. Biologia 74:1669–1673. DOI: 10.2478/s11756-019-00270-7.

- Skyrpan M, Panter C, Nachtigall W, Riols R, Systad G, Škrábal J, Literák I. 2021. Kites Milvus migrans lineatus (Milvus migrans migrans/lineatus) are spreading west across Europe. Journal of Ornithology 162:317–323. DOI: 10.1007/s10336-020-01832-2.

- Stepanyan LS. 1990. Conspectus of the ornithological fauna of the USSR. Moscow: Nauka. (In Russian).

- Sunyer C, Viñuela J. 1996. Invernada de rapaces (O. Falconiformes) en España peninsular e Islas Baleares. In: Muntaner J, Majol J, editors. Biología y conservación de las rapaces mediterráneas, 1994. Sociedad Madrid: Española de Ornitología. pp. 361–370.

- Thaxter CB, Ross-Smith VH, Clark JA, Clark NA, Conway GJ, Marsh M, Leat EHK, Burton NHK. 2014. A trial of three harness attachment methods and their suitability for long-term use on Lesser Black-backed Gulls and Great Skuas. Ringing and Migration 29:65–76. DOI: 10.1080/03078698.2014.995546.

- Tsvelykh AN, Panyushkin VE. 2002. Wintering of the Black Kite (Milvus migrans) in Ukraine. Vestnik Zoologii 36:81–83. (In Russian with English summary.).

- Tutiš V, Kralj J, Radović D, Ćiković D, Barišič S. 2013. Crvena knjiga ptica Hrvatske. Zagreb: Ministry of Environmental and Nature Protection.

- Vansteelant WMG. 2019. An ontogenetic perspective on migration learning and critical life-history traits in raptors. Abstracts of British Ornithologists´ Union 2019 Annual Conference Tracking Migration: drivers, challenges and consequences of seasonal movements, 26–28 March 2019, University of Warwick, UK.