Abstract

Knowing people are willing to protect wildlife when they feel connected with nature, we used owls as a case study to review owl symbolism in Greek history (2900 BC − 2000 AD). For five millennia, Greek civilization thrived and used owls as a dominant symbol in major cultural expressions. Consequently, a broad spectrum of social beliefs evolved towards owls. Until 1500 BC, they were mainly used as decorative attributes. During the Mycenaean era, though, owls began to be worshipped as eerie creatures in funeral rituals, inducing fear and respect. When Greek civilization peaked during the Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic periods, an important shift is noticed in social perceptions. Owls are transformed into major symbols of wisdom, power, justice and divinity, connected to the goddess Athena and the city of Athens. Their significance faded in the subsequent Roman period and was absent throughout the Byzantine era, for 1500 years. When owls reappeared after 1800 AD in cultural aspects of modern Greece, society again considered them fearsome creatures. We finalize our historical review with a recent survey in Greece, capturing up-to-date trends. Our survey indicates that today: (i) owls are mostly considered beneficial and deserving of protection, but part of the population still perceives owls as bad omens, powerful and scary; (ii) elementary concepts of raptors’ importance in ecosystems are still unknown to many; (iii) a small but impactful percentage still deliberately kill house-nesting owls, outlining the need to educate and provide nest-boxes as a relocation solution. By performing a thorough review of historical perceptions toward owls, important insights are offered on how to positively connect people with their wildlife and cultural heritage. We claim that people who understand how nature was related to their country in the past are inspired and more inclined to protect it.

Human societies have always co-existed with wildlife, with a mutual and profound impact on the historical evolution of both (Conover Citation2001). Considering human impact and current trends of biodiversity loss globally, it is essential to continue exploring social aspects of human–nature interactions (Decker & Enck Citation1996; Decker & Chase Citation1997). As human dimensions, attitudes and beliefs shape human–wildlife relationships, they should be included in management decisions for successful conservation (Decker & Enck Citation1996; Manfredo & Dayer Citation2004; Treves et al. Citation2006; Ehrlich & Pringle Citation2008).

In Greek history, birds, mammals and fish always played an important role as symbols in societal aspects (Bakaloudis & Vlachos Citation2009). As Greek civilization evolved, it included wildlife fauna in multiple concepts of religion, politics, mythology, common beliefs, art and clothing (Blondel & Aronson Citation1999; Voultsiadou & Tatolas Citation2005; Gilhus Citation2006). Supporting evidence originates from the epics of Homer, the very first documented literature written 5000 years ago (Yunis Citation2003; Voultsiadou & Tatolas Citation2005). This long history also explains the use of so many Greek words in the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (Ride et al. Citation1985). The contribution of the Greek element to the scientific terminology for animal groups, such as Chordata, reaches up to 80% (Voultsiadou & Gkelis Citation2005; Voultsiadou & Tatolas Citation2005).

Owls specifically, due to their secretive nocturnal nature, held a special place in social aspects of major importance in Greek culture (Voultsiadou & Gkelis Citation2005; Voultsiadou & Tatolas Citation2005). Their expressions in Greek civilization evolved continuously and took many shapes, in different historical periods. Consequently, we focus on owls because they attract great attention due to their nocturnal activity, they generate contradictory expressions in culture and human perception, and they were dominant symbols in Greek history, forming a unique case study (Renfrew Citation1967; Finley Citation1982; Masseti Citation1997; Sverdrup & Schlyter Citation2012). We performed a historical review for the last 5000 years, starting from the Bronze Age, and conclude with a recent survey realized both in insular and mainland Greece. We explored how owls were perceived by society, how this perception changed over time, and how it shaped beliefs, attitudes and behaviors through different historical periods until today, and we offer insights with respect to human dimensions for future management and conservation.

Methods

Historical review

We used a linear historical timeline for our assessment. As a starting point, we consider the end of the Neolithic period in Greece at 2900 BC until the Early Helladic Era at 2000 BC, which corresponds to the Greek Bronze Age (Finley Citation1982; Valamoti Citation2004). We then review the Minoan Age, from 2000 BC until 1600 BC (Antonopoulos Citation1992); the Mycenaean period, from 1600 BC until 1100 BC (Morris Citation1987); and the Dark Age of Greece from 1100 BC until 750 BC, which also includes the Geometric Period (Snodgrass Citation2000). Greek civilization peaked during the Archaic Period, from 750 BC to 480 BC, during the famous Classical Period from 480 BC to 320 BC and during the Hellenistic Period from 320 BC to 146 BC (Boardman et al. Citation2001), which we assessed as one period, globally known as the “Ancient Greece” period. We continue our review with the subsequent Greco–Roman Period from 146 BC to 30 BC, which actually denotes the end of “ancient Greece” and forms the beginning of the early Christian era (Jeffers Citation1999), beginning soon after the Roman Greece Period (30 BC − 330 AD) (Goldhill Citation2001). In the Results section, the Greco–Roman and the Roman Greece periods are also explored as pooled, since the former was the initiation of the latter. We also review the Byzantine Empire Period (330−1453 AD) (Treadgold Citation1997) and the Ottoman Empire Period (1453−1800 AD) (Shaw Citation1976), reaching finally the current state of the Modern Greek Period at the dawn of the 21st century (1800 AD – present day).

In order to perform our historical assessment, we reviewed sources from: (1) scientific literature that mentions and describes the importance of owls in Greek culture and civilization, (2) Important ancient and modern texts that analyze cultural aspects of different Greek periods related to owls. To compile information a number of databases were accessed: Google Scholar, Google Search, ISI Web of Knowledge (Web of Science), JSTOR, Lexicon of Greek Grammarians of Antiquity, Oxford Journals, SAGE Journals, Scopus, SpringerLink, Wiley Online Library, National Greek Documentation Centre, and Thesaurus Linguae Graecae. We used a number of keywords during our search, such as {owls}, {owl}, {ancient Greece}, {Greece}, {symbol}, {perception}, {feeling}, {culture}, {civilization}, {fear}, {power}, {divinity}, {wisdom}, {apotropaic}, {heritage}, {attribute}, and various combinations.

Survey data analysis

We completed our historical review with a recent survey in Greece. We studied up-to-date human dimensions in respect to attitudes, perceptions and behaviors toward owls, based on structured questionnaires organized into five sections (). The first section required personal information regarding the interviewee. The second section recorded the interviewee’s general knowledge about owls, exploring each individual’s baseline background. The third section focused on attitudes and perceptions toward owls in Greece, and the fourth section dealt with human dimensions of a more sentimental nature, recording the interviewee’s attitudes based on feelings toward owls. Finally, the fifth section explored some additional aspects of a more “extreme” behavioral nature, such as killing owls. A total of 17 interviewers participated as focal points from mainland and insular Greece, and realized all in situ interviews by picking people randomly in the street and recording their answers, until they reached a total of 20 interviewees each, controlling for equal gender participation.

Table I. Questionnaire sections and types of variables of each question.

The questionnaires were designed to capture various aspects of human dimensions, in order to provide additional data that could help conservation of owls (conceptual thinking, beliefs, feelings, background knowledge) (Fox et al. Citation2006; Gorenflo & Brandon Citation2006; Berkes Citation2007; Fischer & Young Citation2007). Similar survey designs and social research, combining social aspects in various ecological themes for a more successful biodiversity conservation, have been discussed and suggested in the literature (e.g. Salafsky & Wollenberg Citation2000; Mascia Citation2003; Mascia et al. Citation2003; Saunders Citation2003; McShane et al. Citation2011; Alves et al. Citation2013; Castillo-Huitron et al. Citation2020). We explored statistical differences between interviewees’ answers using chi-square tests (Rao & Scott Citation1981, Citation1984) and subjected major findings to analysis via pivot tables and visualization (Grieneisen et al. Citation2012). Chi-square tests were performed with Statistica vs 10 software.

Multivariate assessment of the historical framework

According to our review, owl significance in Greek culture and civilization can be categorized in eight discrete groups, as a symbol of: (1) divinity and god-like worship; (2) wisdom, knowledge and literacy; (3) power; (4) apotropaic protectors of deceased people’ spirits, having the power to avert evil influences or bad luck; (5) bad omens of death and sorrow; (6) good omens of success and victory; (7) eerie and unearthly creatures; and (8) simple biological entities mainly inspiring casual decorative items. These eight categories were used as response variables in order to explore how they shifted through different historical periods in Greek civilization. Our sample pool comprised cultural expressions. From every relative reference we studied, we extracted and categorized these relative cultural expressions according to how owls were mentioned.

A response matrix was constructed using (i) as response variables (columns) the eight different owl symbolic meanings, and (ii) as samples (rows) the different sources of owl references from our sampling pool as aforementioned; and (iii) we counted the total number of respective owl references per each row–column (Leps & Smilauer Citation2003). Similarly, a predictor matrix was constructed using the same samples–sources as rows, but this time columns included the different historical periods for which all respective owl-references were extracted. The total counts of owl references per historical period and symbolic meaning was recorded in the matrices in absolute frequency values (Leps & Smilauer Citation2003). Ordination techniques were applied in order to explore relationships in a multi-dimensional space, and represent multivariate relationships in low-dimensional space simultaneously (Jongman et al. Citation1995). The goal of any ordination is to summarize the variability within the composition of response variables, which is explained by the measured explanatory variables, for a set of samples or plots (Gauch Citation1982; Jongman et al. Citation1995; Ter Braak & Smilauer Citation2012). They visualize various dimensions simultaneously, represent important and interpretable explanatory and response gradients, and produce graphical results which often lead to ready and intuitive interpretations (Gauch Citation1982; Jongman et al. Citation1995). Analysis was performed using CANOCO 5 software (Ter Braak & Smilauer Citation2012).

An unconstrained ordination (principal component analysis, PCA) is firstly performed on the response dataset, after standardizing data as percentages and performing an arcsine transformation. PCA produces measurements of gradient lengths, which represent a measure of variability in the dataset composition (the extent of groups’ turnover) along the individual independent gradients (ordination axes). Unconstrained ordination values are compared by default with a threshold of 3, indicating whether linear or unimodal modelling (respectively <3 and > 3) should be applied in the follow-up constrained ordination, which will include both the response and predictor datasets (Ter Braak & Smilauer Citation2012). Finally, the produced canonical eigenvalues actually measure the amount of variation in the response dataset that is explained by the explanatory variables. Monte Carlo permutations were used to test the statistical significance of the first ordination axis as well as that of all canonical axes.

Results

Multivariate assessment

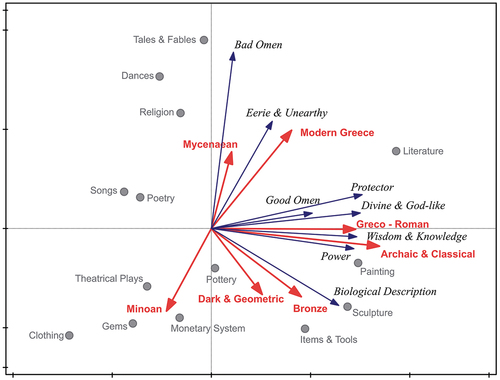

An unconstrained ordination (PCA) indicated that a linear model should be applied to both matrices (gradient length < 3). For this reason, we applied a redundancy analysis (RDA) to explore constrained ordination relationships, which is actually a linear method of canonical ordination. RDA detected patterns of variation in the owl symbolisms that were largely explained by the first two constrained axes produced (), summarizing effectively their variation in different periods of Greek civilization. RDA produced a significant model both on the first two axes (F = 2.72, P = 0.012) and on all the canonical axes (F = 2.62, P = 0.002), indicating that the response matrix variability is adequately represented in the constrained ordination space. Moreover, the first two canonical constrained axes explained 70% of the response dataset variability (), which is visualized in .

Figure 1. Graphical representation of the redundancy analysis-constrained ordination model. Blue-headed arrows with italic-letters represent different owl symbolisms (response variables). Red-headed arrows with bold red letters represent different eras in Greek civilization (explanatory variables). Circular plots with normal small font represent different samples (cultural expressions). Arrows describing Greek periods as well as owl symbolism arrows point in the direction of the steepest increase of their values in their explanatory and response dataset, respectively. The length of the arrow is a measure of fit. The angle between arrows indicates the sign of the correlation between them: the approximated correlation is positive when the angle is sharp, negative when the angle is larger than 90 degrees and neutral when it is at 90 degrees exactly.

Table II. Results of redundancy analysis and permutation test on both response and explanatory matrices after 999 permutations.

“Bronze” and “Minoan” ages (the primary periods of Greek history) produced vectors that extend to the lower part of the ordinational space (). They spread with a strong fit among cultural expressions such as “Clothing”, “Gems”, and “Items & Tools”. Adjacent to the “Bronze” vector, the “Dark & Geometric” vector also extends toward the lower right part of the multivariate space. The “Bronze” and “Dark & Geometric” historical periods appear correlated as explanatory vectors. “Bronze”, though, due to its better fit and sharpest angle, is the one that mainly defines the response variable “Biological Description” of owls. In contrast, the explanatory variable “Mycenaean” age ranges to the upper part of the ordination, among the negative spiritual dimensions related to owls, specifically the response variables “Bad Omen” and “Eerie and Unearthy”. In the ordinational space, the “Archaic-Classical” vector demonstrates the strongest fit of all. In contrast to the “Minoan”, “Bronze”, “Dark & Geometric”, “Mycenaean” and “Modern Greece” periods, it occupies the right part (first and second quadrant) of the ordination. Moreover, it highly correlates with response variables that refer to positive social beliefs about owls in the context of “Power”, “Wisdom”, “Divine”, “Protector” and “Good Omen”. The “Greco–Roman” period extends as well in the same ordinational direction (between the first and the second quadrant of the graph), but with less fit (vector length). As an explanatory variable, it is correlated to the same response variables as the “Archaic-Classical” vector. The final Greek period, “Modern Greece”, extends toward the upper part of the multidimensional graph, along with the explanatory vector of “Mycenaean” age, correlated as well with the “Eerie & Unearthly” and “Bad Omen” response variables.

Survey data analysis

A total of 340 completed personal questionnaires were acquired. Mainland questionnaires dominated the survey (80%), whereas island participants accounted for 20% of the respondents, following the population distribution in mainland and insular Greece. Female and male respondents were sampled at same proportions between islands and mainland as well as between regions of all population sizes (villages to metropolis) (). In addition, female and male interviewees of all age classes participated equally in the survey, and age-class distributions were equal between island and mainland areas ().

Table III. Chi square tests of independence applied on interviewees’ survey responses.

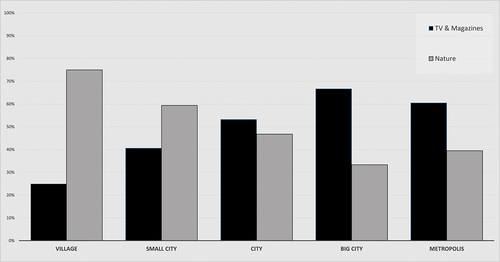

The responses given to baseline questions about nocturnal raptors indicate that the great majority of people know that owls are avian species (97.8% of the responses), and nearly all of the respondents had heard (95.1%) and/or seen an owl (97.8%). A statistical difference occurs between regions of different population size as to whether there are owl species in the region where the interviewees reside (). According to the responses, a larger percentage of people who answered that they “are not sure” (15%) are located in large urban centers, compared to only 3% found in villages and small cities (). Moreover, interviewees from large urban centers have mainly observed owls in media or zoos and not in their natural grounds, with a statistical difference from rural areas’ respondents who have had immediate contact with various owl species in nature () (). Νo differences appeared between female and male respondents from urban-vs-rural areas or mainland-vs-island regions concerning owls’ main prey types, with the majority recognizing small mammals as the main prey type ().

Figure 2. Percentage of interviewees in rural areas and urban centers who answered whether they know if there are any owl species in the regions where they reside.

Figure 3. Percentage of interviewees from rural areas and urban centers who have directly observed an owl in nature or in other ways.

Another aspect that was explored through multiple choice questionnaires is personal beliefs about owls. In respect to the question “what is your personal belief about owls”, the majority responded that owls are just birds (32%), but an important percentage still consider them to be wise beings (27%). To a lesser extent, it is believed that they are bad omens (12%), powerful spirits (6.4%), scary or dangerous (4.9%), and creator beings (3.2%). To a similar question asking how each interviewee considers owls, the highest percentages indicated that owls are considered to be harmless, important and beneficial for the environment (86.2% pooled data). In all aforementioned answers about personal beliefs, there is no statistical difference between urban centers and rural areas, or between mainland and island regions, and this is true for both male and female interviewees (). The only exception concerns the fact that a significantly larger percentage of female respondents believes that owls are still powerful spirits (18.4%), in contrast to males (5.1%).

From a conservation point of view, the great majority of interviewees support that owls should be protected by legislation (96.4%), a belief that is similar in island and mainland regions, in rural areas and urban centers, and between male and female respondents. However, 9.4% of respondents admitted to having killed an owl, 6.3% deliberately (they considered owls to eat pigeons and domestic poultry, or to be nesting in chimneys and roofs), and 3.1% by accidental collision with cars. There is no statistical difference between people who have killed owls in rural and urban areas, or mainland and island regions, but a significantly higher percentage of males (14.0%) had killed an owl in comparison to female respondents (5.0%) ().

In the context of questions concerning various superstitions and “feelings” about owl species in the respondents’ beliefs, there is a significantly larger percentage of interviewees from urban centers (62.7%) in comparison to rural areas (43.0%) who know at least one local or national legend concerning owls (). In addition, mainland areas hold a significantly higher percentage of interviewees, in comparison to insular regions, who know at least one owl legend () (). No differences occur between the various age classes or between female and male respondents on the same questions. On the other hand, in respect to whether the respondents actually believe in any of these owl legends that they are familiar with, the pattern changes with only a minimum percentage responding positively (11.3%), with no statistical difference between island and mainland answers, male and female interviewees, or rural and urban areas (). With respect to the four questions that refer to feelings produced by owls, when respondents talk or hear stories about owls, they present high percentages of neutral feelings (69.5% and 62.8% neutral feelings respectively when one talks about owls and when one hears stories about owls). In contrast, a “happy” feeling is mainly created when the respondents actually observe an owl (46.4%), whereas what mostly scares the interviewees is when they hear an owl screech (14.2%). In all the above four cases, there is no statistical difference between age groups, males vs. females, island vs. mainland regions or rural vs. urban areas.

Figure 4. Answers from rural areas and urban centers in island and mainland regions in respect to whether the interviewees are familiar with at least one local or national owl legend.

Finally, a very low percentage of interviewees has admitted that they have eaten owl meat in the past (1.3%) or used owl eggs (0.9%), a fact that was due to hunger during post Second World War periods.

Discussion

Major shifts of owl symbolism in Greek civilization: summarizing five millennia of history

Human perception toward owls shifted upon four major axes during 5000 years of Greek history, including the “dormancy” period. Using the literature, we corroborate these findings by assessing the effect of each different historical period on owl symbolism and social expressions including our survey of contemporary Greece. We structure the approach based on the sources, which also functioned as our sampling pool for the construction of the historical datasets. Finally, we discuss the implications of our study on owl conservation.

The initiation: owls as simple biological entities

Αt the dawn of Greek civilization, in the Bronze and Minoan Age (2900 BC − 1600 BC), owl symbolism began to be included in a limited number of societal aspects. The Bronze Age is mainly known for the introduction of bronze metal, which changed social classes, transformed burial systems, and increased trade in the Aegean (Renfrew Citation1967; Finley Citation1982). The subsequent Minoan civilization arose on the island of Crete, and its cultural influence reached Cyclades, the mainland of Greece, Egypt and Cyprus (Hornblower et al. Citation2012). Minoans had developed highly advanced technologies for groundwater exploitation and water management (Koutsoyiannis & Angelakis Citation2003), exceptional art in pottery, architecture, clothing, religion, and agriculture, and used their own written and spoken language, sometimes referred to as Eteocretan (Hornblower et al. Citation2012).

As explanatory vectors, “Bronze” and “Minoan” ages appear strongly correlated to the response variable “Biological Description” (). That correlation denotes that the Bronze and Minoan ages shaped owl symbolism in terms of simple decorative and descriptive representations. According to Weingarden (Citation1992) and Krzyszkowska (Citation2005), as trade intensified in the Aegean during the Bronze Age, it required a safer distribution of goods. Therefore, seals, made mainly of perishable wood, started to be used to affix and secure lids of storage jars. Such seals were engraved with a variety of designs, many of them inspired by the natural world using plant motifs, wild goats, insects, lions spiders, and birds (Kenna Citation1968; Ruuskanen Citation1992; Krzyszkowska Citation2005). Owls were included, but not often; particularly Scops owl (Otus scops), Long-eared owl (Asio otus), Eagle owl (Bubo bubo) and Little owl (Athene noctua) (Ruuskanen Citation1992; Haarmann Citation1996). In Minoan art as well, a few owl representations have been found, such as clay rattles for babies carved in the shape of owls (Hornblower et al. Citation2012). A major representative of the Minoan Age in respect to owl symbolism is an earring adorned by double looped chains, which hold golden discs with flying (Little) owls (Masseti Citation1997). This simplified owl symbolism in societal aspects of the Bronze and Minoan Ages is summarized in the lower part of the ordinational space, where the response vector “Biological Description” dominates (). The Dark Age and Geometric period also extend to the lower part of the graph, with a weaker fit (vector length) due to limited findings in the literature .

Fear and respect: owls as unearthly creatures linked to the afterlife

The next important shift in owl significance is noted during the Mycenaean Age (1600 BC − 1100 BC). The kingdom of Mycenae in Peloponnese featured bold traders, excellent engineers and high cultural achievements. The Mycenaeans established trade with Mediterranean and European countries, and created unique burial systems, in which owls played a major ritualistic role (Mylonas Citation1948; Morris Citation1987). It is in the Mycenaean Age that owls became a primary symbol of religious worship in Greece. As an explanatory vector, the “Mycenaean” Age stands among negative spiritual dimensions, at the upper part of the multidimensional space (). The beginning of that perception appears in the early 17th century near Corinth, when religious dances that mimicked owls’ movements started to be performed near tombs during the night. They were probably funeral rituals, very important for the society (Lawler Citation1939, Citation1952). Mycenaeans worshipped and feared owls as chthonic demons, as an incarnation of death and night, and performed this ritual near tombs after dusk in order to be observed by owls (Lawler Citation1939). Owls were also used as a means to protect the dead’s spirit and accompany it to the afterlife. The Mycenaeans buried owls, in the form of golden statuettes, along with their deceased in circular, high-roof “beehive tombs” (Laffineur Citation1981, Citation1983). Various legends of the period further attest to that apotropaic respect, like the legends of Ascalaphus, and Glaucus-Polyidus (Lawler Citation1939; Berens Citation2013). This trend is summarized in the upper part of the constrained ordination plot, where the Mycenaean Age highly correlates with the “Eerie & Unearthly” and “Bad Omen” vectors (). They are response variables, which include social beliefs toward owls which consider them apotropaic protectors, unearthly fearful entities, and a link to the after-death journey. The Mycenaean Age explanatory vector also demonstrates an opposite direction in respect to Bronze and Minoan ages (), denoting the strong differences in owl significance between the historical periods.

The climax: owls as symbols of power, wisdom and divinity

An important shift is noted once again in the significance of owls, as Greek society reaches its civilization peak in the Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic periods (750 BC − 146 BC). The “Archaic-Classical” vector extends to a completely different angle in the ordinational space, in respect to the Mycenaean, Bronze and Minoan periods. It occupies the x axis in the second and third quadrants, indicating a distinct, different owl symbolism during that period (). This change in owl symbolism coincides with Homer’s works in the beginnings of Ancient Greece, the famous epic poet who wrote the Iliad and the Odyssey in the 8th century BC (Powell Citation1996). A total of 1283 animal references are found in the Iliad and 783 in the Odyssey, with the Little owl as the most frequently cited species, mentioned 27 times in the Iliad and 50 in the Odyssey (Voultsiadou & Tatolas Citation2005; see also Lesky Citation1971; Easterling & Knox Citation1985). The importance of owls in Ancient Greece is also found in many texts of important philosophers, historians, writers and lexicographers of the time, such as Homer, Sophocles, Aristofanes, Aristoteles, Aelius, Euripides, Plutarchus, Hesiodus, Hesychius, Pindarus, Lucianus, Theocritus, Atheneaus, Empedocles, Pausanias, and more. A thorough review of the total references to owls in these scriptures was undertaken by Mourmouras (Citation2013a). He focused on tallying the number of times the following words were found in ancient passages: (1) “γλαυξ” (glaux – meaning owl, a word used mainly in ancient texts) was found in 169 passages (Mourmouras Citation2013c), (2) “γλαυκώπις” (glaucopis – the epithet often used to describe the goddess Athena) was mentioned in 333 passages (Mourmouras Citation2013b), and (3) “γλαύκα” (glauca – meaning owl, a word also used today in Modern Greek language) with a total of 236 references, Most references mention the owl as a symbol of wisdom or power, a protector of Athens city, and as a symbol of gods. One of the most famous passages is found in the works of Hesychius from Alexandria (Gershenson Citation1994), describing an owl that flew before the naval battle of Salamis, as a clear harbinger of victory against the Persians (Strauss Citation2004). An identical claim is also found in Aristophanes’ theatrical play Wasps (Reckford Citation1977; Konstan Citation1985), the most important representative of “Athenian comedy” in the Classical Period (Silk Citation2002).

The high correlation between ancient Greece and positive social beliefs toward owls is also observed in the constrained ordination. The “Archaic-Classical” vector appears to shape beliefs toward owls as symbols of divinity, symbols of power and wise beings that protect the Greeks (). The Little owl became the actual sacred symbol of the city of Athens and the goddess Athena, deeply worshipped by Athenians (Watson-Williams Citation1954; Lamberton & Rotroff Citation1985; Voultsiadou & Tatolas Citation2005). During the Panathenaic games of the Classical Period, which later developed into the famous Olympic Games, prize amphoras were awarded as the ultimate honor to the successful competitors. The amphoras usually depicted the goddess Athena in full armor with one or two Little owls at her side (Lamberton & Rotroff Citation1985). Similar paintings in amphoras of the late Archaic Period are exhibited in various museums of the world, like the famous example at the Uppsala Museum (Douglas Citation1912), as well as in various vases and gems of the period (Douglas Citation1912). The unbreakable bond between the Little owl, the goddess Athena and the city of Athens has also been demonstrated in the Acropolis, home of the most important monument of Greece, the Parthenon. The Parthenon has given shelter to two of the most famous Athena statues, the Bronze Statue of “Athena Promachos” made by Pheidias (Lundgreen Citation1997) and the Wooden Statue of “Athena Polias” (Kroll Citation1982; Hurwit Citation1999). Although neither of the two statues has been found, ancient texts and representations in ornaments, pottery and statuettes suggest that both statues held in their hands (or had somewhere in the whole sculpture context) the emblem of the goddess Athena, and the Little owl (Herington Citation1955; Hurwit Citation1999).

The multitude of references that connect owls to a great number of major civilization aspects explains the strong fit of the “Archaic-Classical” vector in the ordinational space. Owl symbolism in Ancient Greece, though, was also used as a major symbol in daily aspects. Owls were depicted in bronze weights which were used in trade, in cosmetic boxes called “pyxis” (Hoffmann Citation1997), and even in boards of the early Archaic Period, such as the renowned fragment of a Corinthian Pinax held in Berlin Museum (Douglas Citation1912). Little owls often decorated ordinary drinking cups of the Classical Period, called “kantharos” and “skyphoi” (Lamberton & Rotroff Citation1985). They were designed mainly for drinking wine during rituals devoted to Dionysus, god of wine and fertility (Sparkes Citation1991). Sotades, a famous artist who painted owl schemes on “kantharos” cups, produced important examples which survive to the present day (Hoffmann Citation1997). According to Hoffmann (Citation1997), whenever owls and olive branches appeared together in Sotades’ work, they denoted the city of Athens and its protector the goddess Athena. “Skyphoi” cups as well included a special category called “glaux-skyphos” (Beazley Citation1963; Boardman Citation1989). They were designed to resemble an owl, and decorated as well with repeated patterns of Little owls (Johnson Citation1955; Hoffmann Citation1997; Watson Citation1998; Crawford Citation1999).

The most important use of Little owl symbolism, though, in daily life of Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic Greece, was the bird’s representation on ancient Greek coins. The Athenians started to mint their own coins as early as 575 BC, and the series of these Athenian coins were named “owls” (Sverdrup & Schlyter Citation2012). The goddess Athena was carved on the obverse of the coin, and her emblem the Little owl, on the reverse. Eight major types of the Athenian “owls” are distinguished from 561 BC to 42 BC. All of them maintained the emblematic Little owl and goddess Athena on their sides, as emblems unchanged for 500 years, with different versions portrayed for each period (Sverdrup & Schlyter Citation2012). Athenian “owls” were arguably the most influential of all coins as the first widely used international currency (Sverdrup & Schlyter Citation2012). The use of the “owls” silver coinage ended in the middle of the 1st century BC.

For at least six centuries, owls became iconic and emblematic symbols characterizing the peak of Greek civilization. As history continues to the subsequent Greco-Roman and Roman-Greece period, similar positive perceptions toward owls are maintained, but their importance fades. That is primarily denoted by the explanatory vector that extends toward the same direction in the ordinational space as the “Archaic-Classical” vector, but with less fit. Secondly, it is further corroborated by the fact that Roman Greece maintained owl symbols in certain cultural expressions. The “Athenian Owls” silver coinage, for instance, may have ended in the middle of the 1st century BC, but some currency featuring an owl continued in the Roman period until 267 AD (Alocock et al. Citation2001; Sverdrup & Schlyter Citation2012). The Roman goddess Minerva was equated with the goddess Athena, and Romans continued to use the Little owl as her symbol. They added an epithet to her description and called her “Athena Minerva” (Snowball Citation2008). One of the most famous Athena Minerva statues, holding a Little owl, is still exhibited in the Louvre museum. Furthermore, during the Greco-Roman and Roman Greece period, a stylized ritualistic owl dance was performed during social events, as a weakened form reminiscent of the earlier Mycenaean owl dances (Lawler Citation1939). Finally, owls were very seldom found in literature during the Greco-Roman period, with the rare Merope-Agron myth included in the “Metamorphoseon Synagoge” being one example (Celoria Citation1992).

“Dormancy” period: the disappearance of owl symbolism

Before the final shift in owl significance, owl symbolism goes dormant for more than 1500 years in Greek civilization, during the periods of hte Byzantine Empire (330−1453 AD) and the Ottoman Empire (1453−1800 AD). The Byzantine Empire was one of the longest periods in Greek history, spanning a total of 11 centuries. The main theme of the Byzantine Empire was the expansion of Christianity. Consequently, most animal symbols in religion, including owls, were treated as pagan and heretic (Gilhus Citation2006; Clogg Citation2002; Shaw Citation2003). Although certain Byzantine flags and family insignia used animal species (e.g. a double-headed eagle), and signs such as the tetragrammic cross, owls were not represented (Vasiliev Citation1952; Elsner Citation1988). Similarly to the Byzantine period, the Ottoman Empire, having emerged from a completely different geographic and geo-political region (i.e. Turkey), with a very different culture, did not include owls as a symbol, during the four centuries that Greece was governed by the Ottomans.

One step ahead, one step back: owls at the end of the 20th century, as bad omens of death

The final Greek historical period, after 1800 AD, occupies the upper part of the multidimensional graph driving Greek society, once again, toward negative beliefs for owls (). After 1821 in early Modern Greece, owls initially reappear as positive cultural expressions, in symbols of the Greek revolution against the Ottomans (Clogg Citation2002; Shaw Citation2003). They were featured on rebel and naval flags as attacking or eating a snake. At the time, the snake represented the conqueror and the owl the revolutionists (Aggelidou Citation1909; Nouhakis Citation1909; Mazarakis-Ainian Citation1996a, Citation1996b). Although the representation is not clear and it could be thought to resemble any bird, historians and analysts propose that it most probably depicts the Little owl (Mazarakis-Ainian Citation1996a, Citation1996b). Nonetheless, in the second half of the 19th century, owls only appear in literature movements of Greece with negative perceptions: the “Rebel romanticism movement”, the “Ionian School” and the “Bucolic movement”. An explicit example of the rebel romanticism poetry is found in Aristotelis Valaoritis’ poem “Thanasis Vagias” (Valaoritis Citation1867). There, an owl calls upon the grave of a man, pleading for him to rise and walk again among the world of the living. Similarly, in a series of poems published in the literature magazine Illisos (1868–1872) and the newspaper Asty (Ambelas Citation1868; Avvakoum Citation1885; Kollatos Citation2008; National Documentation Centre - Ilissos Magazine Citation2013), the owl is again presented as a fearsome night symbol, a species related to psychological pain and lamentation, and a bad omen that preannounces death. Julius Typaldos, the most important representative of the “Ionian School” movement (National Book Centre of Greece Citation2008a), describes in one of his poems a conversation between a Little owl and a Scops owl. Both owls are disappointed because although their voices are the ones heard at night, people disapprove of them as unearthly voices and praise the Common Nightingale (Luscinia megarhynchos) instead. The “Bucolic” movement, finally, differed from the previous two because it was inspired by the struggle of people who lived in rural areas, based on real life. Nonetheless, special references to owls were once again related to death. Kostas Krystallis, a major representative of Bucolic poetry (National Book Centre of Greece Citation2008b), describes in his poem “The Sunset” the repeated call of the Scops owl. He claims that it is a lament-call to his brother, whom he had murdered in anger when they both had human form, and, due to his sorrow, he was transformed into a Scops owl. Similarly, in the trilogy of Xristos Vasileiou called The Love, published in 1906 (National Book Centre of Greece Citation2008c), owl species are described as eerie, unearthly and fearful night creatures (Xristovasilis Citation1906). When heard hooting from the roof of a house, they were considered a bad omen that preannounces death.

Consequently, at the end of the 20th century in Greece, owls were presented as major signs of bad luck and death. As such, the “Modern Greece” vector occupies the same ordinational space as the Mycenaean Age and both are correlated with the “Eerie & Unearthly” and “Bad Omen” response vectors. On the other hand, negative social perceptions toward owls in Modern Greece no longer include any element of worship or respect due to fear, as in the Mycenaean Age. Therefore, although owls in the Mycenaean age induced fear they were also worshipped and respected (Lawler Citation1939), whereas after 1800 AD owls were mainly considered a bad omen, that preannounces death or bad luck (Ambelas Citation1868; Avvakoum Citation1885; Xristovasilis Citation1906). That fact may have placed additional pressure on owls since people, absolved from fear and religious worship, could be more inclined to displace, disturb and even hunt down animals which are considered to be bad omens and bad luck.

History meets the present: how past perceptions evolved into recent social beliefs

As the 21st century unfolds, ecological movements are rising, and non-governmental organization (NGO) campaigns are increasing. With the expansion of the internet, society is receiving more messages about ecological aspects and natural processes, and is experiencing a higher concern about human impact on nature. In Europe, the creation and expansion of the Natura 2000 network has also significantly altered social perceptions and attitudes. In post-war Greece, it is only after 1950 that owls slowly began to be used again as simple symbols, without a negative attribution, in diverse social occasions. They start decorating primary and secondary school uniforms in the early 1950s, and military uniforms as well; they are engraved in Greek euro coinage after 2002; and they become the emblem of the national Greek Organization for the Publishing of Educational Books (OEDB Citation2008; EKEBI Citation2008). As our survey findings indicate, a large part of Greek society today is well informed with respect to elementary ecological aspects concerning owl species. That fact denotes that basic information has reached the broader population, possibly through a combination of the education system and online accessible information. Reasonably enough, residents of smaller urban regions were more aware whether there were owls living in their region (). Similarly, residents of urban centers mainly had secondary contact with owl species, through media (). Both outcomes were expected, but pinpoint nonetheless an important target for awareness and actions.

Although elementary knowledge about owls is widespread in Greece today, an important part of the population, mainly females, still believe that owls are wise beings. That could be an effect of the owl being used in school books as a symbol/logo of wisdom, or due to owl symbolism as wise beings in Ancient Greece. Most responses, though, attributed that perception to the use of logos, detached from the important historic role of owls. Furthermore, about 10% still believe in superstitious owl legends today, and report being overwhelmed with fear when hearing an owl screech, considering it a bad omen. Apparently, the recent 20th century, with a multitude of negative references toward owls, has instilled part of the society with strong negative perceptions toward owls. As our survey captures, on one hand, knowledge about nature and ecological awareness has apparently increased in recent Greece. On the other hand, this new trend collides with a segment of society who adopt negative 20th century perceptions toward owls, while probably being unaware of the positive symbolism of owls in Ancient Greece.

Within that context, another highly contradictory pattern is the following: Greek society seems to accept owls widely in very high percentages, as beneficial for the environment, and as species that should be protected by legislation. One would expect that this fact would at least minimize the motivation for killing owls intentionally, if not increase individual actions for conservation. On the contrary, though, a small but quite impactful number of interviewees (just over 6%), mostly male respondents, admit to killing owls on purpose due to attacks on domestic birds and to nesting in chimneys. In terms of owls eating domestic poultry, at least, a thorough literature review of the owl diet, proves that this is actually very rare (Roulin Citation2004; Roulin & Dubey Citation2012, Citation2013). In addition, the fact that owls are still considered by part of the population to be bad omens and a lack of education possibly function synergistically as motivation for someone to kill an owl. Consequently, important education and awareness actions are still and urgently needed, to untangle the problem of deliberate owl killing. Finally, the aspect of consuming owl meat and owl eggs in Greece appeared at very low frequency, and also took place only during the Second World War,decades ago, due to hunger.

Implications for owl conservation

By combining recent attitudes and beliefs toward owls in Greece with the long historical importance of the species in Greek civilization, we define which human attitudes remain at present, and how recent perceptions, attitudes and behavior are shaped toward owls. We outline below, from the combination of these two aspects, the main socio-ecological points that could be considered in future management.

Basic information in respect to owl biology and ecology is lacking in age classes of 20 to 50 years old. An important part of educative and informative actions should be directed there, in order to eliminate gaps and create a robust background for adults, who will most likely be called on to implement or comply with conservation actions and legislation. Along with educational efforts on ecological aspects, the historical importance of owls in Ancient Greece should be applied as an inspiration. Efforts should be targeted especially to rural populations who are in direct contact with wildlife.

Inhabitants of large urban centers, and specifically children from large population areas, abstain from natural contact with fauna generally, including owls. Considering that children, as tomorrow’s adults, will form an active part of society and our ecosystems as well, an increase in natural contact as an integral part of educative actions should be directed to this group. Such educative actions could include cooperation with rehabilitation centers and civil society organizations that could bring children near individual owls through field trips or nest box visits, and through informative programs with audio-visual context in classrooms.

A percentage of the population (15%), equally divided across mainland and islands, rural and urban areas, and age classes, supports that owl species are neutral for the environment. Nonetheless, high-level predators in ecosystems are quality indicators, and especially owls, as possible natural agents for pest control, are of high ecological importance. Therefore, we suggest to enrich informative campaigns with (a) the significance of the ecological niches of owls in both natural ecosystems and in rural areas which suffer from rodent population explosions, (b) how owls function in ecosystems as quality indices and top-level predators, and (c) why owls are important biodiversity indicators.

Greek society appears to be at a mature point to accept further legislative actions on protection and conservation of owls, since the great majority of the interviewees attests to that fact. This is a very important point to be considered, at both central and decentralized levels, and such an agenda should be pursued with effective cooperation among civil society organizations, nature conservation organizations and responsible governmental bodies, to build together a new legislative context.

A persistent segment of the population still considers owls a bad omen that induces fear and relates to death, as a remnant of negative 20th century cultural references. Informative campaigns to alter that perception can be based on two pillars: (i) biological traits: the positive role of owls in our ecosystems; and (ii) sociological traits: juxtaposing the perception of owls as bad omens due to their secretive nature and screeching cry with the historical positive meaning of owls as a symbol of power, divinity and protection, and as a good omen.

In order for any conservation measure to come into effect, we must consider the 6.3% of the population that openly admits to killing owls deliberately for attacking poultry and nesting in house chimneys. Considering that we refer to the deliberate killing of animals which are already under national protection in the legislation, in the 21st century, that percentage is considered high. Immediate actions should focus on that segment of the population, mostly men, and offer environmental awareness seminars. As additional leverage, the high connection between owl symbolism and the prosperous Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic periods could be used. It would probably inspire a sense of pride and affection toward owls as cultural heritage, and change perception toward species that people observe nesting in their surroundings. Recognizing the importance of owls as natural pest control agents would also certainly instill a positive connection between people and owls.

As alternative solutions to the above point, we suggest to introduce the context of artificial nest boxes in a national scheme of funding, perhaps under the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) agro-environmental scheme, as a possibility for owl relocation due to undesired nesting within human constructions which are in use. In respect to the belief that owls attack domestic poultry, a thorough literature review of owl diet proves that this is erroneous (Roulin Citation2004; Roulin & Dubey Citation2012, 2013), therefore it is only a matter of proper environmental awareness and informing.

Conclusions

As a concluding remark, we suggest that the historical role of owls in Greek civilization could function as leverage for people to commit to owl conservation. Scientific knowledge per se is not enough for nature protection, especially when rural stakeholders are involved. Furthermore, in countries with long histories like Greece, modern societies may be detached from many millennia of positive symbolism between natural elements and social perceptions. Owls in particular were connected with a strong bond to humans during the long trajectory of five millennia of Greek history. They shaped social expressions, and human beliefs shaped attitudes and behaviors toward owls. The fact, though, that owls played a major role in Greek civilization (Ancient Greece) but that their symbolic importance became dormant for more than 1500 years (Byzantium Age and Ottoman period) gave birth to a post-Ottoman Greece (1800 AD–today) which was cut off for almost two millennia from the civilization that endorsed owls. Apparently, recent Greek society could not adopt a similar state of mind toward owls. Furthermore, after Greece succeeded the Byzantine period (where owls were considered pagan symbols) and four centuries of Muslim symbolism, the country entered into two centuries of war and turbulence (1800–1975 AD). Consequently, modern Greek society was more prone to adopt a negative and superstitious attitude toward secretive, mysterious and nocturnal fauna species. Although Greek history is rich with positive perceptions toward owls, the 19th and 20th centuries were mainly characterized by a negative attitude.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (5.1 MB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (59.5 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the following people for their help in conducting in situ interviews as focal points all over Greece: Foto Konsola, Anastasios Xenos, Dimitra Nikiforidou, Christos Damianidis, Elias Pappas, Georgios Bakaes, Alexandros Gasios, Ioannis Sidiropoulos, Mixalis Mavromichalis, Kostas Mavromichalis, Akis Stefanou, Liana Ganigianni, Akis Giapis, Antonis Stagogiannis and Anastasios Sakoulis. We also specifically thank Professor Kassiani Gogou and her team for their extended historical research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/24750263.2023.2254823

References

- Aggelidou N. 1909. The Greek flag - Its historical evolution from Ottoma occupation till today. Athens, Greece: The printing Office of Pan-hellenic state. p. 96.

- Alocock SE, Cherry JF Elsner J, eds. 2001. Pausanias: Travel and memory in Roman Greece. New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Alves F, Filho WL, Araujo MJ Azeiteiro UM. 2013. Crossing borders and linking plural knowledge: Biodiversity conservation, ecosystem services and human well-being. International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development 7(2):111–125. DOI:10.1504/IJISD.2013.053323.

- Ambelas TD. 1868. The glaux. Ilissos 1(1):28–29. in Greek Available: file:///C:/Users/User/Downloads/iliss_may1868.pdf

- Antonopoulos J. 1992. The great Minoan eruption of Thera volcano and the ensuing tsunami in the Greek archipelago. Natural Hazards 5(2):153–168. DOI:10.1007/BF00127003.

- Avvakoum. 1885. The glaux. Asty 1(12):3.

- Bakaloudis D Vlachos C. 2009. Chapter 1: Introduction to wildlife management. In: Wildlife management: Theory and applications, Bakaloudis D Vlachos C, editors. Thessaloniki, Greece: Tziola Publications. pp. 25–32. in Greek

- Beazley JD. 1963. Attic red-figure vase-painters. 2nd ed. New York: Hacker Art Books. p. 2036.

- Berens EM. 2013. The myths and legends of ancient Greece and Rome. Dogma, Bremen Deutchland: A handbook of mythology.

- Berkes F. 2007. Community based conservation in a globalized world. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104(39):15188–15193. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0702098104.

- Blondel J Aronson J. 1999. Biology and wildlife of the Mediterranean region. New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Boardman J. 1989. Athenian red figure vases, the Classical period: A handbook. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Boardman J, Griffin J Murray O. 2001. The Oxford illustrated history of Greece and the Hellenistic world. New York, USA: Oxford Illustrated Histories, Oxford University Press.

- Castillo-Huitron NM, Naranjo EJ, Santos-Fita D Estrada-Lugo E. 2020. The importance of human emotions for wildlife conservation. Frontiers in Psychology 11:1277. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01277.

- Celoria F. 1992. The metamorphoses of Antoninus Liberalis: A translation with a commentary. 1st ed. London: Routledge. p. 256. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315812755/metamorphoses-antoninus-liberalis-francis-celoria-antoninus-liberalis.

- Clogg R. 2002. A concise history of Greece: Cambridge Concise Histories. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Conover M. 2001. Resolving human-wildlife conflicts the science of wildlife damage management. 1st ed. Boca Raton Florida: CRC Press. p. 440. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.1201/9781420032581/resolving-human-wildlife-conflicts-michael-conover-michael-conover.

- Crawford L. 1999. Some thoughts on the owl skyphoi in the Antiquities museum. Queensland Friends of the Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens 29:6–10.

- Decker DJ Chase LC. 1997. Human dimensions of living with wildlife – a management challenge for the 21st century. Wildlife Society Bulletin 25(4):788–795.

- Decker DJ Enck JW. 1996. Human dimensions of wildlife management: Knowledge for agency survival in the 21st century. Human Dimensions of Wildlife an International Journal 1(2):60–71. DOI:10.1080/10871209609359062.

- Douglas EM. 1912. The owl of Athena. The Journal of Hellenistic Studies 32:174–178. DOI:10.2307/624140.

- Easterling PE Knox BMW. 1985. The Cambridge history of classical literature. I: Greek Literature. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK [Greek translation by N. Konomi, C. Griba and M. Konomi, 1999, Papademas Press, Athens].

- Ehrlich PR Pringle RM. 2008. Where does biodiversity go from here? A grim business-as-usual forecast and a hopeful portfolio of partial solutions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105(1):11579–11586. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0801911105.

- EKEBI. 2008. National book Centre of Greece: Ministry of education, and religious affairs, culture and sports. Available: http://www.ekebi.gr/frontoffice/portal.asp?cpage=NODE&cnode=138&clang=1

- Elsner J. 1988. Image and iconoclasm in Byzantium. Art History 11(4):471–491. DOI:10.1111/j.1467-8365.1988.tb00319.x.

- Finley MI. 1982. Early Greece: The Bronze and Archaic ages (ancient culture and society). 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company. p. 149.

- Fischer A Young JC. 2007. Understanding mental constructs of biodiversity: Implications for biodiversity management and conservation. Biological Conservation 136(2):271–282. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2006.11.024.

- Fox EH, Christian C, Nordby JC, Pergams ORW, Peterson GD Pyke CR. 2006. Perceived barriers to integrating social science and conservation. Conservation Biology 20(6):1817–1820. DOI:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00598.x.

- Gauch Jr. HG. 1982. Multivariate analysis in community ecology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Gershenson DE. 1994. Hesychius Γεννὁν or rather Γεννών. Revue des Etudes Juives 153(1–2):153–158. DOI:10.2143/REJ.153.1.2012638.

- Gilhus IS. 2006. Animals, gods and humans: Changing attitudes to animals in Greek, Roman and early Christian ideas. 1st ed. London and New York: Routledge. p. 336.

- Goldhill S, ed. 2001. Being Greek under Rome: Cultural identity, the second sophistic and the development of the empire. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Gorenflo LJ Brandon K. 2006. Key human dimensions of gaps in global biodiversity conservation. Bioscience 56(9):723–731. DOI:10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[723:KHDOGI]2.0.CO;2.

- Grieneisen ML, Zhang M von Elm E. 2012. A comprehensive survey of retracted articles from the scholarly literature. PlosOne 7(10):e44118. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0044118.

- Haarmann H. 1996. Early civilization and literacy in Europe: An inquiry into cultural continuity in the Mediterranean. In: Series: Approaches to semiotics, De Gruyter. DOI:10.1515/9783110869057.

- Herington CJ. 1955. Athena Parthenos and Athena Polias: A study in the religion of Periclean Athens. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Hoffmann H. 1997. Sotades: Symbols of immortality on Greek vases. New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Hornblower S, Spawforth A Eidinow E, editors. 2012. The Oxford Classical dictionary. New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Hurwit JM. 1999. The Athenian Acropolis: History, mythology, and Archaeology from the Neolithic era to the present. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Jeffers JS. 1999. The Greco-Roman world of the new Testament era: Exploring the background of early Christianity. London: IVP Academic. p. 352.

- Johnson FP. 1955. A note on owl skyphoi. American Journal of Archaeology 59(2):119–124. DOI:10.2307/501102.

- Jongman RHG, Ter Braak CJF van Tongeren OFR. 1995. Data analysis in community and landscape ecology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Kenna VEG. 1968. Studies of birds on seals of the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean in the Bronze Age. OpAth 8:23–38.

- Kollatos T 2008. Pleias: Asty, University of Patras. Available at: http://xantho.lis.upatras.gr/pleias/index.php/asty [in Greek].

- Konstan D. 1985. The politics of Aristophanes’ “Wasps”. Transactions of the American Philological Association 115:27–46. DOI:10.2307/284188.

- Koutsoyiannis D Angelakis AN. 2003. Hydrologic and hydraulic science and technology in ancient Greece. In: Stewart BA HowellT, editors. Encyclopedia of water science. New York: Dekker. pp. 415–417.

- Kroll JH. 1982. The ancient image of Athena Polias. Hesperia Supplements: Studies in Athenean Architecture, Sculpture and Topography 20:65–76. DOI:10.2307/1353947.

- Krzyszkowska O. 2005. Aegean seals: An introduction. In: Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. London, UK: University of London Press. p. 455. https://library.biaa.ac.uk/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=169663.

- Laffineur R. 1981. Le symbolisme funeraire de la chouette. L’ Antiquite Classique 50(1/2):432–444. DOI:10.3406/antiq.1981.2024.

- Laffineur R. 1983. Early Mycenaean art: Some evidence from the west house in Thera. Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 30(1):111–122. DOI:10.1111/j.2041-5370.1983.tb00440.x.

- Lamberton RD, and Rotroff SI. 1985. Birds of the Athenian Agora. In: Agora picture book 22. New Jersey: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Princeton University Press. p. 36.

- Lawler LB. 1939. The dance of the owl and its significance in the history of Greek religion and the drama. Transactions and Proceedings of the 71st American Philological Association 70: 482–502. https://www.jstor.org/stable/283107.

- Lawler LB. 1952. Dancing herds of animals. The Classical Journal 47(8):317–324.

- Leps J Smilauer P. 2003. Multivariate analysis of ecological data using CANOCO. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Lesky A. 1971. Geschichte der Griechischen Literature. Bern: Francke. [Greek translation by A. Tsopanakis, 2003. Kyriakidis Press, Thessaloniki].

- Lundgreen B. 1997. A methodological inquiry: The great Bronze Athena by Pheidias. The Journal of Hellenic Studies 117:190–197. DOI:10.2307/632558.

- Manfredo MJ Dayer AA. 2004. Concepts for exploring the social aspects of human wildlife conflict in a global context. Human Dimensions of Wildlife an International Journal 9(4):1–20. DOI:10.1080/10871200490505765.

- Mascia MB. 2003. The human dimension of coral reef marine protected areas: Recent social science research and its policy implications. Conservation Biology 17(2):630–632. DOI:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01454.x.

- Mascia MB, Broscius JP, Dobson TA, Forbes BC, Horowitz L, McKean MA Turner NJ. 2003. Conservation and the social sciences. Conservation Biology 17(3):649–650. DOI:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01738.x.

- Masseti M. 1997. Representations of birds in Minoan art. International Journal of Osteoarcheology 7:354–363. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1212(199707/08)7:4<354:AID-OA387>3.0.CO;2-R.

- Mazarakis-Ainian IK. 1996a. Flags of freedom. Historical and Ethnological Society of Greece [In Greek]. p. 184.

- Mazarakis-Ainian IK 1996b. The history of the Greek flag. Cultural Foundation of Cyprus Bank , Lefkosia[in Greek].

- McShane TO, Hirsch PD, Trung TC, Songorwa AN, Kinzig A, Monteferri B, Mutekanga D, Thang HV, Dammert JL, Pulgar-Vidal M, Welch-Devine M, Broscius JP, Coppolillo P O’Connor S. 2011. Hard choices: Making trade-offs between biodiversity conservation and human well-being. Biological Conservation 144(3):966–972. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2010.04.038.

- Morris I. 1987. Burial and ancient society. The rise of the Greek city-state. New Studies in Archeology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Mourmouras D 2013a. The symbol of wisdom the Little owl: An historical fraud. [in Greek]. Available: http://dimitriosmourmouras.blogspot.gr/2013/01/blog-post_5.html

- Mourmouras D 2013b. The symbol of wisdom the Little owl: An historical fraud. References to the Word “glaukopis” [In Greek]. Available: http://www.physics.ntua.gr/~mourmouras/agxivasihn/glaukopis/glaukopis.pdf

- Mourmouras D 2013c. The symbol of wisdom the Little owl: An historical fraud. References to the word “glaux” [in Greek]. Available: http://www.physics.ntua.gr/~mourmouras/agxivasihn/glaukopis/glaux.pdf

- Mylonas GE. 1948. Homeric and Mycenaean burial customs. American Journal of Archaeology 52(1):56–81. DOI:10.2307/500553.

- National Book Centre of Greece. 2008a. Archive of Greek litterateurs: Julius Typaldus. Available: http://www.ekebi.gr/frontoffice/portal.asp?cpage=NODE&cnode=461&t=578 [in Greek].

- National Book Centre of Greece. 2008b. Archive of Greek litterateurs: Kostas Krystallis. Available: http://www.ekebi.gr/frontoffice/portal.asp?cpage=NODE&cnode=461&t=243 [in Greek].

- National Book Centre of Greece. 2008c. Archive of Greek litterateurs: Xristos Vasileiou. Available: http://www.ekebi.gr/frontoffice/portal.asp?cpage=NODE&cnode=461&t=416 [in Greek].

- National Documentation Centre – Ilissos Magazine. 2013. Available at: http://openarchives.gr/set/1242 [in Greek].

- Nouhakis I. 1909. Our Flag.

- OEDB. 2008. Organization for the Publishing of educational books: Digital library. Available: http://www.oedb.gr:8080/oedvLibrary/user/ [in Greek].

- Powell BB. 1996. Homer and the origin of the Greek alphabet. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Rao JNK Scott AJ. 1981. The analysis of categorical data from complex sample surveys: Chi-squared tests for goodness of fit and independence in two-way tables. Journal of the American Statistical Association 76(374):221–230. DOI:10.1080/01621459.1981.10477633.

- Rao JNK Scott AJ. 1984. On Chi-squared tests for multiway contingency tables with cell proportions estimated from survey data. The Annals of Statistics 12(1):46–60. DOI:10.1214/aos/1176346391.

- Reckford KJ. 1977. Katharsis and dream-interpretation in Aristophanes’ “Wasps”. Transactions of the American Philological Association 107:283–312. DOI:10.2307/284040.

- Renfrew C. 1967. Cycladic metallurgy and the Aegean early Bronze Age. American Journal of Archeology 71(1):1–20. DOI:10.2307/501585.

- Ride W, Sabrosky C, Bernardi G Melville R, eds. 1985. International code of zoological nomenclature. London: Great Britain International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature and University of California Press.

- Roulin A. 2004. Covariation between plumage colour polymorphism and diet in the Barn owl Tyto alba. Ibis 146(3):509–517. DOI:10.1111/j.1474-919x.2004.00292.x.

- Roulin A Dubey S. 2012. The occurrence of reptiles in Barn owl diet in Europe. Bird Study 59(4):504–508. DOI:10.1080/00063657.2012.731035.

- Roulin A Dubey S. 2013. Amphibians in the diet of European Barn owls. Bird Study 60(2):264–269. DOI:10.1080/00063657.2013.767307.

- Ruuskanen JP. 1992. Birds on Aegean Bronze Age seals: A study on representation. Series: Studia Archaeologica Septentrionalia, Pohjois-Suomen Historiallinen Yhdistys (Publisher).

- Salafsky N Wollenberg E. 2000. Linking livelihoods and conservation: A conceptual framework and scale for assessing the integration of human needs and biodiversity. World Development 28(8):1421–1438. DOI:10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00031-0.

- Saunders CD. 2003. The emerging field of conservation psychology. Human Ecology Review 10(2):137–149.

- Shaw MKW. 2003. Possessors and possessed: Museums, archaeology, and the visualization of history in the late Ottoman Empire. University of California Press

- Shaw SJ. 1976. History of the Ottoman empire and modern Turkey: Volume 1, Empire of the Gazis: The rise and decline of the Ottoman empire 1280-1808. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Silk MS. 2002. Aristophanes and the definition of comedy. New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Snodgrass AM. 2000. The dark age of Greece. Edinburgh University Press

- Snowball JD. 2008. Measuring the value of culture: Methods and examples in cultural economics. Verlag Berlin Heidelberg: Springer.

- Sparkes BA. 1991. Greek pottery: An introduction. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Strauss B. 2004. The battle of Salamis: The naval encounter that saved Greece and the Western civilization. New York, USA: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, Rockefeller Center.

- Sverdrup HA Schlyter P. 2012. Modeling the survival of Athenian owl tetradrachms struck in the period from 561-42 BC from then to present. Paper presented at the 30th International Conference of the System Dynamics Society, St. Galen, Switzerland.

- Ter Braak CJF Smilauer P. 2012. Canoco reference manual and user’s guide: Software for ordination, version 5.0. Ithaca, USA: Microcomputer Power.

- Treadgold W. 1997. A history of the Byzantine state and society. Stanford, California, USA: Stanford University Press.

- Treves A, Wallace RB, Treves LN Morales A. 2006. Co-managing human-wildlife conflicts: A review. Human Dimensions of Wildlife an International Journal 11(6):383–396. DOI:10.1080/10871200600984265.

- Valamoti SM 2004. Plants and people in late Neolithic and early Bronze Age Northern Greece: An Archaeobotanical Investigation. Bar International Series, British Archeological Reports.

- Valaoritis A. 1867. Thanasis Vagias. In: A romantic: The anthologist ermis series. Vol. 14. Athens, Greece: Ermis Publishing. pp. 112–118.

- Vasiliev AA. 1952. History of the Byzantine Empire. Wisconsin, USA: The University of Wisconsin Press.

- Voultsiadou E Gkelis S. 2005. Greek and the phylum Porifera: A living language for living organisms. Journal of Zoology 267:1–15. DOI:10.1017/S0952836905007326.

- Voultsiadou E Tatolas A. 2005. The fauna of Greece and adjacent areas in the Age of Homer: Evidence from the first written documents of Greek literature. Journal of Biogeography 32(11):1875–1882. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01335.x.

- Watson M. 1998. The owls of Athena: Some comments on owl-skyphoi and their iconography. Art Bulletin of Victoria 39:35–44.

- Watson-Williams E. 1954. Γλαυκώπις Αθήνη (Glaucopis Athene). Greece and Rome Second Series 1(1):36–41. DOI:10.1017/S0017383500012286.

- Weingarden J. 1992. The multiple sealing system of Minoan Crete and its possible antecedents in Anatolia. Oxford Journal of Archeology 11(1):25–37. DOI:10.1111/j.1468-0092.1992.tb00254.x.

- Xristovasilis X 1906. The Love: Trilogy. Printing Office P.A. Petrakou, Athens, Greece.

- Yunis H. 2003. Written texts and the rise of literature culture in ancient Greece. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. DOI:10.1017/CBO9780511497803.