?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The interlanguage of second and foreign language French learners presents certain patterns that offer a formal framework within the context of the Applicative Combinatory Categorical Grammar. These patterns manifest in the acquisition of object clitics which presents considerable difficulties for French second language learners. To address this, we thoroughly analysed the object clitic pronouns that appeared in a corpus of texts by examining the different facets of these pronouns. A formal analysis was then proposed. The objective of this research is to establish an automated system for processing learners’ interlanguage in terms of the ACCG.

1. Introduction

Research examining the object clitics (OC) in Romance languages in general, including the French language, constitute an inexhaustible source of information for linguists, as they are studied in terms of various aspects of language such as in syntax, phonology, morphology, semantics and in pragmatics. While native speakers generally have no significant difficulties in mastering OCs, French L2 learners face several challenges when it comes to their spoken and written productions (Grüter, Citation2005) as it requires a mental effort before selecting and placing the appropriate OC within a sentence. Additionally, Wust (Citation2010) suggests that the difficulties in acquiring OCs could be due to the syntactic complexity involved in their calculation and the overgeneralization of the subject clitics to the object clitics contexts.

Consequently, some learners, in some cases, may attempt to determine the accurate placement of the clitic within a sentence before selecting the appropriate pronoun. Some others resort to avoidance, a technique that French second language (L2) learners use when facing some challenging structures and contexts. This technique enables them to avoid the target language feature when they have difficulty with it. Indeed, some studies demonstrated that the omission of object clitics is more common than placement errors (Grüter, Citation2006; Paradis, Citation2004).

To assist L2 learners in mastering these complex language units, some researchers have proposed using action-oriented didactic tasks (Pirvulescu & Hill, Citation2012), while others believe that ICT and remote communication, among other action-oriented tasks, can enhance learners’ performance in this specific language area (Jebali, Citation2018). Yet, in addition to these proven effective strategies, we can provide a computerized tool based on a formal analysis of the productions of learners. This tool will allow learners to detect the most common errors and propose appropriate corrections and feedback.

To achieve our goals, we will start by analysing the interlanguage, with a focus on in its particularities which involve the clitics in question. This analysis will involve examining the documented use or omission of these OCs in the productions of French L2 learners. These productions will allow us uncover the regularities that characterize the linguistic system of the second and foreign language learners, known as the interlanguage. Once the analysis is complete, the different realizations of the OCs will then be formalized.

The following section presents the learner interlanguage while section 3 provides a literature review on the topic. Finally, section 4 discusses the formalization within the framework of Applicative and Combinatory Categorial Grammar (ACCG), which constitutes the main contribution of this paper. This marks the first application of a categorical model to provide a formal framework for interlanguage analysis.

ACCG is a lexicalized grammar. The rules of the model are fixed, uniform and language independent. As will be demonstrated in section 4, the types assigned to the lexical units allow for the identification of the role of each lexical unit. This approach is of great interest for language learning as it can be applied to different language structures without the need for the implementation of a large set of rules.

2. Interlanguage

2.1. The concept

Selinker (Citation1972) introduced the concept of interlanguage, which encompasses three interconnected systems involved in the process of L2 learning: the first language (L1, also called mother tongue or native language), the second language (L2, also called target language) and interlanguage. Interlanguage is defined as the language system that is used by the language learners that holds features from learner’s L1, the target language, and other potential sources. This language “system” is dynamic as it evolves during the learning process and is susceptible to external changes (social, psychological, etc.).

Despite its dynamic features, the interlanguage has common spheres that overlap regardless learners’ individual differences, L1 or the target language. In fact, the assessment of the various interlanguages revealed the presence of certain properties that are universal, meaning they are common and shared among all L2 learners. Selinker (Citation1972) highlights two noteworthy properties in this regard: the omission of functional categories (including OC pronouns) and the grammatical morphemes. In addition, several researchers have found that some L2 appropriation sequences can be classified as universal (Herschensohn, Citation2004; Jasmin, Citation1994).

2.2. French object clitics in the interlanguage

2.2.1. The acquisition of French object clitics

In French, object pronominalization is realized through OCs (me [me], te [you / singular], le [him], la [her], nous [us], vous [you], les [them], etc.) or weak pronouns (Grüter, Citation2005). OCs appear preverbally and cannot be separated from the verb, except by other clitics or the negation element ‘ne’. Also, OCs cannot occur alone and are generally a part of a cluster (subject and object).

Indeed, OCs are categorized into two groups: direct object clitics and indirect object clitics. The choice is made here according to the subcategorization grid of the verb. This feature increases the complexity for learning (Scheidnes et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, according to Scheidnes et al. (Citation2020) and Pirvulescu and Strik (Citation2014), clitics are phonetically reduced, i.e. deaccentuated, form a phonetic unit with the verb, cannot be coordinated and cannot be the complement of a preposition.

When it comes to the acquisition of the OC pronouns, Pirvulescu and Strik (Citation2014) cited that OCs are acquired later than subject and reflexive clitics. In fact, the following universal order was proposed:

The postverbal position: the production of the clitic in a position that the object phrase would occupy (example: Nous avons écrit l’article. – > *Nous avons écrit le).

The omission of the object (*Nous avons écrit) : no object is present whether a noun phrase or a clitic, which constitutes a mistake if the verb is transitive.

The intermediate position: the production of the clitic in an inappropriate position in relation to the auxiliary (*Nous avons l’écrit.),

The pre-finite position: the production of the expected correct form as in the target language (Nous l’avons écrit.).

These stages have been observed by Towell and Hawkins (Citation1994) in adult learners of French L2. These universal appropriation stages allow us to locate the regularities and to formalize the grammar of the interlanguage of French L2 learners.

2.2.2. Corpus

CEFLE (Corpus Écrit de Français Langue Étrangère) is a corpus of 460 texts written in French by Swedish learners of French L2. This corpus was developed by Ågren Malin at Lund University, Sweden, during the 2003/04 academic year for her Ph.D. dissertation. This dissertation examined French L2 number and gender features. The corpus was published online in 2009 at the following URL: https://projekt.ht.lu.se/cefle/.

For the purpose of our research, 400 texts were used from the transversal and longitudinal sub-corpuses. The texts were written by 110 high school French L2 learners encompassing four proficiency levels: beginners, elementary, intermediate, and low-advanced. We excluded 60 additional texts in the corpus produced by a control group of French native speakers as they were not relevant to our study. The 400 texts emerged from two primary tasks:

A narration task in which students are asked to narrate two essays on their lives: Me, my family and friends; and A trip memory.

A picture description in which students describe two sets of pictures created to elicit narratives: The man on the island and the trip to Italy.

All of the measures taken to ensure that the learners were in a stress-free environment while performing the tasks were described in detail by Ågren (Citation2008). Although this corpus was not originally designed to elicit OCs, it is considered as a valuable source for studying French L2 learners’ interlanguage. In fact, the absence of the targeted OCs in the original study ensures that these productions were not controlled. Therefore, this corpus provides an authentic representation of the spontaneous use or non-use of these pronouns by the learners. Helms-Park (Citation2016) confirms that “patterns based on elicited data may differ from those based on the production of spontaneous utterances, because careful elicitation generally compels the learner to commit to a response type, often prematurely” (p. 93). She also emphasized on the fact that “when responses are elicited under very tight guidelines”, this may force “learners to make decisions they might otherwise avoid” (p. 93).

2.2.3. Object clitics in CEFLE corpus

This section will focus on the most prominent properties of OCs in the CEFLE corpus. As a reminder, the interlanguage is a language system that combines elements from several sources, including L1, L2 and the interlanguage itself. Therefore, we anticipate that learners will produce both correct and incorrect OCs (regardless of the origin of errors). Additionally, we predict a significant amount of avoidance, manifested through repetition or complete omission.

In CEFLE corpus, the usage of OCs is not prevalent, which reflects the typical behaviour of French L2 learners towards these pronouns (i.e. the avoidance technique). Furthermore, and as expected, some participants succeeded to accurately use the OCs, while others did not. The following sentence presents an example where the OC respects the rules of the target language:

Ils voyagent en car et un guide leur donne des explications sur plusieurs monuments. (English: They travel by car and the guide gave them information about the numerous monuments.)

OCs were also misused in several contexts by the participants in this corpus. These mistakes can be classified into two types:

The absence of the OC pronoun: occurs when participants avoided using the OC by repeating the noun phrase or by omitting the object with a verb that usually requires it.

The faulty use of the OC pronoun: this occurs either by using the correct clitic in a non-target-like position, or by using a non-clitic pronoun (e.g. a strong pronoun), or by using a clitic whose morphosyntactic (gender, person, case) or semantic (animate versus inanimate) features are faulty.

The following sentence presents an example where the OC was avoided by using repetition of the noun phrase:

*Elle a deux chiens, un noir et un blanc. Elle aimes les chiens. (Target-like sentence should be: Elle les aime. The meaning would be: She has two dogs; one black and the other is white. She likes dogs.)

*Autres hommes construent autres maisons et fabriques. (Target-like sentence should be: et les fabriquent. The meaning would be: Other men build other houses and make them.)

*Ils disent que ils veulent faire un usine à l'île de Pierre et ils le vont donner beaucup des argent. (Target-like sentence should be: ils vont lui donner beaucoup d’argent. The meaning would be: They say that they want to make a factory on Pierre’s island and that they will give him a lot of money.)

*Ils y rencontrent deux jeunes garcons qui viennent le voir. (Target-like sentence should be: qui viennent les voir. The meaning would be: There, they met two young boys who came to see them.)

As presented in examples (2) to (5), the errors made with OCs were almost always accompanied by other types of errors. For instance, in example (2), the verb “aimes” is not accurately conjugated. In example (3), the determinant is omitted twice and the verbs “construire” and “fabriques” are not properly conjugated. Therefore, multiple errors in the same sentence are detected and although the meaning conveyed by these statements is understood, these structures represent a real challenge to the formalization and to the automatic language processing systems.

Section 3 is dedicated to a literature review of studies that have undertaken to formalize and treat learner interlanguage.

3. Previous work

Since the 1990s, researchers have been interested in the automatic processing and formalization of learner interlanguage with studies focusing on English and other languages, as well as French as a second language. This classification allows us to identify relevant studies that can help us analysing the interlanguage of French L2 learners through the use of object clitic pronouns. For example, Dodigovic (Citation2003) and Maritxalar et al. (Citation1997) focus on English and Basque, while Jebali (Citation2023) and Parslow (Citation2015) concentrate on French as a second language. Pienemann (Citation1992) has a multilingual approach aimed at SLA researchers.

Dodigovic (Citation2003) discusses the development of an intelligent tutor for second language learners of English. The tutor’s goal is to identify common errors made by these learners and provide them with appropriate corrections. The study uses a corpus of academic English, and the tool is designed to focus on the most common grammatical features in that corpus. However, due to the nature of the corpus used by the researcher (that of English for Academic Purposes or EAP), the tool proved to be very limited to the subset of grammatical features found in academic English.

Maritxalar et al. (Citation1997) discuss the implementation of a psycholinguistic model of second language learners’ interlanguage in an intelligent computer-assisted language learning (ICALL) system. The paper focuses on identifying the common interlanguage structures among students at the same language level and presents the Interlanguage Level Model (ILM) based on these structures. The goal of the system is to help learners develop their interlanguage through interactive exercises and feedback. However, there are two limitations to this study: it solely focuses on word-level analysis, and it is specific the Basque language. While the study emphasizes the interlanguage of learners at the same level, which is of great interest to us, it is unclear how it can be applied to the study of clitic pronouns in the L2 interlanguage, as such an analysis cannot be limited to the word level alone and must encompass the sentence and discourse levels.

Pienemann (Citation1992) describes the development of a computational system for linguistic analysis of language acquisition data. The system, called COALA, which enables users to formulate complex queries about morphosyntactic and semantic structures found in large sets of data. COALA serves as a semi-automated tool that helps researchers in testing their hypotheses about the data they are studying. While COALA is intended to support English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish, its primary focus is on aiding researchers in second language acquisition to assist them in working with data analysis and hypotheses testing.

It should be noted that the annotation tasks carried out by COALA can be accomplished using more modern systems based on Transformers, such as Spacy (Altinok, 2021), for some of its multilingual models, as well as for French (thanks to the fr_dep_news_trf package). This package and the POS tagger of Spacy were used by Jebali (Citation2023) to browse a corpus of L2 French texts and extract contexts where object clitics were used, with the indispensable need for manual editing work.

Concerning French L2, Parslow (Citation2015) examines the development of automatic assessment tools for French language learners. The study analyses the L2 productions of learners and identifies over 50 possible metrics of vocabulary, corrections, verb use, clause use, syntax and cohesion. The paper suggests that similar opportunities exist for developing tools in French as there are in English. The paper concludes that “NLP tools designed primarily for formal L1 French are surprisingly robust when applied to (often highly unorthodox) L2 productions.” However, the specificities of the interlanguage of learners are not directly considered. Regarding object clitics, we need tools and approaches that take into account the particularities of L2 productions, which differ significantly from those of native speakers.

Jebali (Citation2023) describes a shift towards data-driven and machine learning techniques in the field of second language acquisition. The goal is to develop models that can find patterns in data and utilize these patterns to predict outcomes on new data. The paper presents a case study of 899 examples and discusses plans for a more detailed study targeting object clitics in L2 French. Despite the clear interest of this study, it should be noted that it is currently limited in scope and more resembles more to a proof of concept. Therefore, we should wait for the publication of results concerning a wider range of data and a more robust empirical coverage.

The following section presents a formal framework for OCs in the interlanguage in the context of ACCG.

4. Applicative combinatory categorical grammar

All Categorial Grammar models are founded on explicit logical rules, replacing a purely surface linguistic analysis with an inferential logical calculation. Relying more on the notion of surface structure, it leads to a logical form to express a functional meaning. One advantage of this approach is being able to represent the intricacies of phrasal units through the operation of applying an operator to its operand, which is a universal representation in itself.

Although Categorial Grammars had somewhat faded since Husserl (with concepts of categorems and syncategorems), Lesniewski (semantic categories), Adjukiewics, Bar-Hillel and Lambek (Lambek’s calculus), the filed witnessed a significant outburst of work and research in the 70s, 80s, 90s and 2000s. The “collective” can be dubbed “Flexible Categorial Grammars”, and is represented by:

Montague’s model of Universal Grammar for a categorial syntax and denotational semantics,

Steedman’s Combinatory Categorial Grammar associating a categorial syntactic analysis and a the construction of functional semantics interpretation by way of lambda-calculation,

Harris’ operator-operand grammar,

the Applicative Combinatory Categorial Grammar with the addition of metarules to direct the rules of type-raising and composition, as well as other generalizations from Lambek’s calculus.

Recent developments include the multimodal version of Combinatory Categorial Grammars (Steedman & Baldridge, Citation2011), which introduce modalities and restrictions on the application of categorial rules to eliminate ambiguity, and even the Abstract Categorial Grammar model to describe both syntax and semantics.

Despite the differences between these approaches and their applications, three notable aspects stand out in all of these models: (i) their use of logical and mathematical methods to account for language, particularly syntax; (ii) their distinction of several logical levels of language representations, including at least a linear structure of the observable level and a operator-operand structure of the construction level; (iii) their flexibility and adaptability to analyse multiple languages. To expand the trend of Categorial Grammars, recent work conducted exploratory analyses for non-Indo-European languages. Examples include the relative constructions in Turkish (Bozsahin, Citation2012), complement forms in – te in Japanese (Kubota, Citation2007), Korean (Kang, Citation2011) and the morphological agreements in Arabic (Biskri & Jebali, Citation2018).

In our work, we employ the formal model of ACCG. Within this model, we distinguish two levels of language representation. The first level is the level of observable statements, where syntagmatic organization, word order and morphology are taken into consideration. The second level encompasses the applicative representations underlying the first level where the units of the language directly apply to each other through the operation of application, independently of any morphosyntactic constraint. ACCG allows encoding the procedures to validate the morphosyntactic correctness of statements; and to construct their applicative representation.

Like the entirety of categorial models (Steedman, Citation2000), ACCG conceptualizes languages as organized linear systems of linguistic units, some of which function as operators and others as operands. To achieve this, each lexical token is assigned one (or more) category that expresses how it functions. These categories are types recursively developed from the basic types (N for noun, S for sentence, N* for noun phrase, etc.) by using two constructive operators ‘/’ and ‘\’ according to:

Basic types are types.

If X and Y are types, then X/Y (The type of an operator whose typed operand Y is positioned on the right) and X\Y (whose typed operand Y is positioned on the left) are types.

Rules of ACCG canonically associate combinatory rules with combinators of combinatory logic. Combinatory rules ensure to validate the syntactic correctness of sentences, whereas combinators allow the construction of the applicative expressions underlying the sentences.

Combinatory logic was introduced by Moses Schönfinkel in 1924, and later extended by Curry and Feys in 1958. It is a variable-free logic. It uses abstract operators know as combinators to enable the construction of more complex operators from simpler one. Each combinator is provided with a β-reduction rule to express how it applies to its operands. β-reduction rule defines the equivalence between the logical expression without combinator and the one with combinator. Each β-reduction rule serves as a rule for introducing or eliminating a combinator. represents some combinators and their β-reduction rules (for more combinators, the reader might read Curry & Feys, Citation1958; Desclés et al., Citation2016; Hindley & Seldin, Citation2008).

The composition combinator B combines two operators x and y together and constructs the complex operator B x y that acts on an operand z, z being the operand of y and the result of the application of y to z being the operand of x.

The permutation combinator C uses an operator x in to build the complex operator C x that acts on the same two operands as x but in reverse order.

The distribution combinator □ distributes an operand u to two operators y and z. The results (y u) and (z u) become the first and second operands of x.

The type raising combinator C* takes an operand x and construct the complex operator C* x that acts on the operator y.

Table 1. Examples of combinators and their β-reduction rules.

These rules are independent of the meaning of the arguments. They establish a relationship between an expression with combinators and a possible expression without combinators called the normal form. In the ACCG model, normal forms represent functional semantic interpretation or simply the applicative representation of sentences. This normal form is unique, according to Biskri and Desclés (Citation1997).

The distributive combinator S combines two operators x and y together and constructs the complex operator S x y that acts on an operand z, z being the operand of y and the first operand of x, while its second operand is the result of the application of y on z.

As shown here, combinatory logic uses combinators to compose or to transform operators to get more complex operators. It makes it possible to build more complex operators from more basic operators by a sequence of compositions or transformations carried out by the means of combinators. Combinators are defined independently of a restrictive interpretation to a specific use. They have an intrinsic semantic content. Expressions using combinators are called combinatory expressions.

Elementary combinators can be combined to construct a more complex combinator. Its global action is determined by the successive application of its elementary combinators taken from left to right. For instance, in the combinatory expression B C x y z u v, the combinator B is applied first, then C.

(1)

(1)

The resulting expression, without combinators, is called a normal form. This form, according to Church-Rosser theorem, is unique. Two other forms of complex combinators exist: the power and the distance of a combinator. Let COMB be a combinator.

The power of a combinator, noted by COMBn, represents the number n of times its action must be applied. It is recursively defined by:

In other terms, if COMB=B, then:

etc.

For example, the action of B3 in the combinatory expression “B3 x y z t u” would be:

The power of a combinator is needed when we use operators requiring more than one operand. In the expression “x (y z t u)”, y applies on three operands. This justifies why the combinator B3 was used.

The distance of a combinator, noted by COMBn, represents the number n of steps its action is postponed. It is recursively defined by:

In other terms, if COMB = B, then:

etc.

For example, the action of B3 in the combinatory expression “B3 x y z u v t” would be:

Let us now go through the rules of the ACCG model (for more details, the reader might read Biskri (Citation2018). The premises in each rule is the concatenation of linguistic units, whereas the consequence in each rule is the application of one linguistic unit to another with the possible introduction of one combinator. Let us assume that u, u1 and u2 are linguistic units.

Application rules:

(2)

(2)

Type raising rules:

(3)

(3)

Functional composition rules:

(4)

(4)

Distributive composition rules :

(5)

(5)

It is proven that rules (>), (<), (>B), (<B), (>T), (<T), (>S) and (<S) are theorems of Lambek Calculus and leads to a context-free model (Pentus, Citation1993). However, it is likely that adding rules (>Bx), (<Bx), (>Tx), (<Tx), (>Sx) and (<Sx) will induce greater expressive power than context-free grammar. Other rules can be added. Yet, they must be characterized by these three principles (Steedman, Citation2000):

The principle of Adjacency: Combinatory categorial rules may only apply to adjacent linguistic units.

The principle of Consistency: Combinatory categorial rules must be consistent with how the principal operator should apply to its operand. For instance, the principle of consistency excludes the following rule in which u1 is the operator whose operand, according to the type X\Y, must be positioned on its left.

The principle of Inheritance: if the category that results from the application of a combinatory rule is a functional category, then the constructive operator ‘/’ or ‘\’ in that category will be the same as the one defining the position of the corresponding argument in the premise. For instance, the principle of inheritance excludes the following rule in which the constructed operator (B u1 u2) applies on its left to an operand of type Z whereas this operand is positioned on the right of u2.

5. Object clitics by means of ACCG

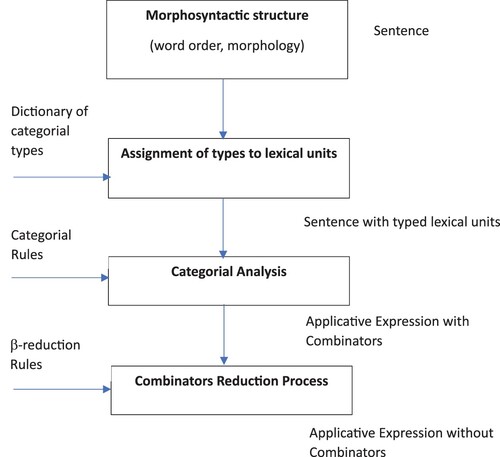

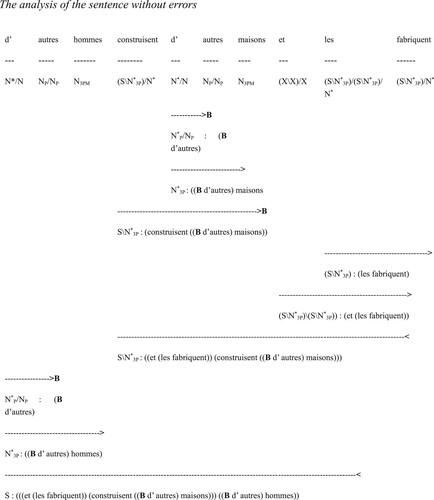

Before analysing some of the aforementioned ungrammatical sentences, let us first give a diagram of the procedure of a sentence analysis by means of ACCG and then demonstrate how ACCG analyses the valid sentence with object clitics (1) .

The analysis conducted using the ACCG involves three main steps:

The first step is illustrated by the assignment of types to each lexical unit of the sentence. These types will express how each lexical unit functions. These assigned types are returned from a categorial dictionary whose lexical units of the sentence to be analysed are inputs.

The second step is illustrated by the verification of the morphosyntactic correctness of the sentence. The output of this step indicates whether the sentence is faulty or morphosyntactically valid. In case of morphosyntactic correctness, the applicative expression underlying the sentence is constructed with the progressive introduction of combinators in the sentence. To do this, we use ACCG rules presented above.

The third step is illustrated by the elimination of combinators by means of β-reduction rules like those presented in . We, then, construct the applicative expression without combinators to express the functional semantic interpretation of the sentence.

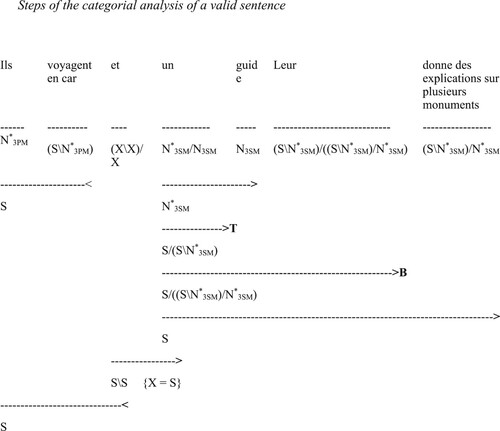

Let us now show how ACCG analyses the valid sentence with object clitics (1). The first step of analysis in involves the assignment of categorial types to each lexical unit to express their function. For example, types N*3PM and (S\N*3PM) are assigned respectively to Ils (they) and voyagent en car (travel by coach) to express: (i) how they will apply to each other; (ii) the morphological agreement between them. With its assigned type N*3PM (N* for noun phrase, 3 for third person, P for plural and M for masculine), Ils is considered as a noun phrase of the third person, plural, and masculine person. With its assigned type (S\N*3PM), the intransitive verb voyagent en car is considered as an operator whose operand is a noun phrase of third person plural masculine positioned on its left.

Applying the operator voyagent en car to the operand Ils, following the rule (<) given in (2), results in a type S. The well-constructed applicative expression ((voyagent en car) Ils) will clearly express the order in which the operator applies to its operand in the first member of the coordination. The rule (<) is applicable since the type of the expected operand of the operator voyagent en car is the same as the type of Ils. We then follow the same steps to construct the second member of the coordination before applying the conjunction et to the two members of the coordination. To give et the ability to apply to both members of the coordination, it has been assigned the type (X\X)/X, where X represents the type of each member of the coordination. et is considered as an operator whose first operand positioned on its right, and this operand must be of type X. The type of the result of applying et to its first operand is X\X, which is an operator whose operand is positioned on its left and is of type X. The type (X\X)/X is, in fact, a type scheme and we substitute the real types for each analysis through unification. In the case of the analysis in , X is replaced by S through unification. By getting the type S at the end of the analysis, the sentence is considered correct.

The object clitic leur (them) in this sentence is not a noun phrase. It is an operator whose operand is the transitive verb donne des explications sur plusieurs monuments (gives information about several monuments) whose type is (S\N*3SM)/N*3SM. Consequently, we assign it the type (S\N*3SM)/((S\N*3SM)/N*3SM). Just as a reminder, the verb donner (to give) is considered as a verb with two objects. The first one in this case is des explications sur plusieurs monuments (information about several monuments) and the second one is replaced by the clitic leur. Since leur is an anaphora of ils, they must agree morphologically on person, number and gender.

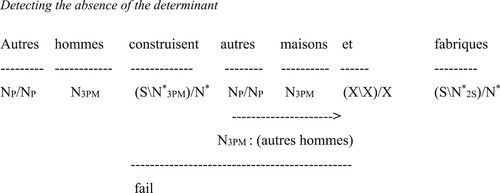

Let us now have a look at the analysis of the ungrammatical sentence in example (3) “Autres hommes construent autres maisons et fabriques”. There are four errors in this sentence. Construent (build) should have been conjugated in the 3rd person plural and the correct form is construire (to build). However, the right word should have been construisent. The word construent will therefore not be included in the dictionary entry for the categorical types and should appear as an error. To explain the detection of other errors, we will assume that construent is replaced with construisent.

In French, autres hommes (other men) and autres maisons (other houses) must be used with their respective determinants. This kind of error can be easily detected by the analyzer. The analysis in identifies this error. For instance, the operator construisent, as shown by its type, requires a noun phrase as a first operand. Yet, autres maisons is classified as a noun according to its type N3PM. Therefore, it requires a determinant to be considered as a noun phrase. The same situation applies to autres hommes. Construisent (build) needs a noun phrase as its second operand, not a noun. The categorial analysis enables the detection of both grammatical errors, and the learner can rectify them by adding the determinant d’ before autres hommes and autres maisons. The type N*/N designates d’ as an operator which takes a noun as its operand to construct a nominal phrase.

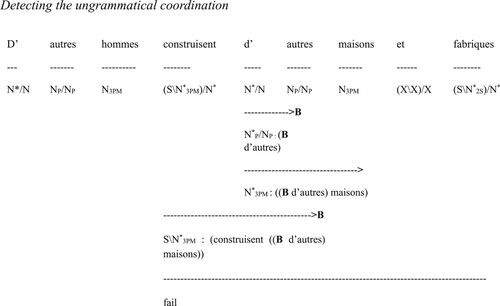

To illustrate the detection of the remaining two errors, we need to assume that the first errors have been corrected and the partially corrected sentence to be considered is d’autres hommes construisent d’autres maisons et fabriques (). In this sentence, we identify two remaining errors. The first error is morphological in nature. The verb fabriques is conjugated in the second person singular, while the subject d’autres hommes is in the third person plural. The second error is syntactic. The verb fabriques, being transitive, requires either the presence of a complement positioned to its right or a clitic to its left.

These two errors occur in one of the two members of the coordination: construisent d’autres maisons (build other houses) and fabriques (make). The derived type of construisent d’autres maisons is S\N*3PM whereas the type of fabriques is (S\N*2S)/N*. These two different types allow us to detect the syntactic error. The two members of coordination are supposed to have the same type according to the type schema (X\X)/X of the conjunction. Therefore, the analysis fails at this stage. With the type (S\N*2S)/N*, it is clearly expressed that fabriques is a transitive verb functioning as an operator, with its first operand being a noun phrase positioned to its right or an object clitic preceding it. Furthermore, fabriques is the first member of the coordination, whereas construisent d’autres maisons is the second member. With its type S\N*3PM, construisent d’autres maisons behaves as an intransitive verb. On another hand, fabriques is conjugated at the 2nd person of singular. It is the type N*2S of the expected subject in the type (S\N*2S)/N* that allows to know this. The expected subject type for the intransitive verb construisent d’autres maisons is N*3PM, which is similar to the type N*3P of the subject d’autres hommes (see ).

The correct sentence should have been : d’autres hommes construisent d’autres maisons et les fabriquent. It would have been analysed as in .

At the end of the analysis in , we get the type S. That means the sentence is correct. The analysis constructs, also, the underlying applicative combinatory expression “(((et (les fabriquent)) (construisent ((B d’ autres) maisons))) ((B d’ autres) hommes))“ of the sentence, in which we can observe how the linguistic operators apply to their operands. This first expression contains combinators. By reducing them using the β-reduction rules given in , we will get the normal form that expresses the functional semantic of the sentence “d’autres hommes construisent d’ autres maisons et les fabriquent”.

The process of reduction is the following:

(((et (les fabriquent)) (construisent ((B d’ autres) maisons))) ((B d’ autres) hommes))

et (les fabriquent) (construisent ((B d’ autres) maisons)) ((B d’ autres) hommes)

Φ∧ (les fabriquent) (construisent ((B d’autres) maisons)) ((B d’autres) hommes)

∧ ((les fabriquent) ((B d’ autres) hommes)) ((construisent ((B d’ autres) maisons)) ((B d’ autres) hommes))

∧ ((les fabriquent) (d’ (autres hommes)) ((construisent ((B d’ autres) maisons)) ((B d’ autres) hommes))

∧ ((les fabriquent) (d’ (autres hommes))) ((construisent (d’ (autres maisons))) ((B d’ autres) hommes)

∧ ((les fabriquent) (d’ (autres hommes))) ((construisent (d’ (autres maisons))) (d’ (autres hommes)))

In step 2, we remove all of the most left parentheses as well as the closing parentheses that correspond to them. In step 3, as shown in (Biskri & Desclés, Citation2006) the distributive coordinating conjunction et is replaced by the logical expression Φ ∧. The combinator Φ and the logical connector ∧ express, respectively, the distributive nature and the conjunctive role of et. Thanks to the combinatory Φ the operand ((B d’autres) hommes) is distributed to operators (les fabriquent) and ((construisent ((B d’ autres) maisons)). ((B d’autres) hommes) is, thus, clearly identified as the subject of (les fabriquent) and ((construisent ((B d’ autres) maisons)). Steps 5, 6 and 7 allow to reduce the combinator B to construct the complex linguistic operators. At the end of this reduction process. we get two clauses: ((les fabriquent) (d’ (autres hommes))) and ((construisent (d’ (autres maisons))) (d’ (autres hommes))) connected by the logical connector ∧. The first one expresses the functional semantic interpretation of d’autres hommes les fabriquent (other men make them). The second expresses the functional semantic interpretation of d’autres hommes construisent d’autres maisons (other men build other houses).

The advantage of employing a categorial approach over a standard approach based on rewriting rules primarily lies in the reduced number of rules needed to account for various cases. For instance, consider ‘autres maisons’ (other houses) as shown in , which requires the use of a determinant. This determinant can be represented by a definite article in ‘les autres maisons’ (the other houses), an indefinite article in ‘d’autres maisons’ (other houses), a possessive determinant in ‘ses autres maisons’ (his other houses), a demonstrative determinant in ‘ces autres maisons’ (those other houses), a numeral determinant in ‘trois autres maisons’ (three other houses), and so on. With a rewriting-rule-based approach, we would require a multitude of rules to cover all conceivable cases. Additional rewriting rules may need to be introduced to handle unforeseen cases. This can result in increased algorithmic complexity and potential ambiguity during analysis (Steedman, Citation2000).

In the categorial model proposed in this work, ‘les,’ ‘des,’ ‘ses,’ ‘ces,’ and the numeral ‘trois’ are considered as operators whose operand, of type name, is positioned to their right. The type notation N*/N assigned to these determinants effectively conveys their role. Essentially, any linguistic unit operating as an operator can work on another linguistic unit acting as an operand, provided that the assigned types permit the application of one of the rules outlined in section 4. For unforeseen linguistic constructions, there is no need to create new rules. Simply adding the appropriate lexical unit with the correct type to the categorial types dictionary suffices.

We believe that a model based on rewriting grammars, unlike a categorial model, would be too rigid to cover a wide range of sentences without resorting to a large number of rules.

6. Conclusion

The purpose of this study is to develop an automated system for processing learners’ interlanguage in terms of the ACCG, specifically in relation to object clitic pronouns. The suggested system aims to comprehend the difficulties faced by French L2 learners when using OC pronouns and provide automatic corrections.

The ACCG framework is highly versatile and can be easily tailored to analyse L2 interlanguage. By conceptualizing the sentences as sequences of linguistic units in terms of operators and operands, a formal framework is established for conducting a detailed analysis. Through this study, we have demonstrated how errors related to the use of OC pronouns and the morphological agreements can be detected using the ACCG approach. Additionally, we have highlited the importance of extending the categorial types to integrate morphological knowledge related to person, gender and number.

Through the use of the ACCG framework in an automated system, this research contributes to the development of tools that can help in the analysis and the correction of the interlanguage of the learners, specifically in the domain of OC pronouns. This provides valuable support for language learners, helping them overcome the difficulties in mastering the correct use of OC pronouns and ensuring more accurate language production.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Affes, A., Biskri, I., & Jebali, A. (2022). French object clitics in the interlanguage: A linguistic description and a formal analysis in the ACCG framework. In N. T. Nguyen, Y. Manolopoulos, Y., Chbeir, R., Kozierkiewicz, A., Trawiński, B. (eds.), Computational Collective Intelligence. ICCCI 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer.

- Ågren, M. (2008). À la recherche de la morphologie silencieuse [Ph.D. dissertation]. Lund University.

- Altinuk, D. (2021). Mastering spaCy. Packt.

- Biskri, I. (2018). La coordination et la subordination en français et les systèmes applicatifs typés. Verbum: Revue De Linguistique, 40(2), 173–198.

- Biskri, I., & Desclés, J. P. (2006). Coordination de catégories différentes en français. Faits de Langues, 28(1), 57–66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/19589514-028-01-900000007

- Biskri, I., & Desclés, J. P. (1997). Applicative and combinatory categorial grammar (from syntax to functional semantics). In R. Mitkov, & N. Nicolov (Eds.), Recent advances in natural language processing (pp. 71–84, Vol. 136). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Biskri, I., & Jebali, A. (2018). Categorial analysis of agreement asymmetries in arabic. In K. Shaalan, & S. R. El-Beltagy (Eds.), Procedia computer science (pp. 278–285, Vol. 142). Elsevier.

- Bozsahin, C. (2012). The combinatory morphemic lexicon. Computational Linguistics, 28(2), 145–186.

- Chbeir, A. Kozierkiewicz, & B. Trawiński (Eds.), Computational collective intelligence. ICCCI 2022. Lecture notes in computer science. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-16014-1_18

- Curry, H. B., & Feys, R. (1958). Combinatory Logic. North-Holland Publishing Company.

- Desclés, J. P., Guibert, G., & Sauzay, B. (2016). Logique Combinatoire et (Lambda)-Calcul : des logiques d’opérateurs. Cépaduès Éditions.

- Dodigovic, M. (2003). Natural language processing (NLP) as an instrument of raising the language awareness of learners of English as a second language. Language Awareness, 12, 187–203.

- Grüter, T. (2005). Comprehension and production of French object clitics by child second language learners and children with specific language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics, 26(3), 363–391. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0142716405050216

- Grüter, T. (2006). Object (clitic) and null object in the acquisition of French. McGill University.

- Helms-Park, R. (2016). Evidence of lexical transfer in learner syntax. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 23(1), 71–102. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263101001036

- Herschensohn, J. (2004). Functional categories and the acquisition of object clitics in L2 French. Language Acquisition and Language Disorders, 207–242. https://doi.org/10.1075/lald.32.11her

- Hindley, J. R., & Seldin, J. P. (2008). Lambda-calculus and combinators, an introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- Jasmin, L. (1994). Acquisition des pronoms clitiques objets par des apprenants adultes du français langue seconde [Ph.D. dissertation]. University of Ottawa.

- Jebali, A. (2018). Anxiété langagière, communication médiée par les technologies et élicitation des clitiques objets du français L2. Alsic. https://doi.org/10.4000/alsic.3164

- Jebali, A. (2023). Deep learning for the teaching of L2 French clitic object pronouns. INTED2023 Conference.

- Kang, J. (2011). Problèmes morpho-syntaxiques analysés dans un modèle catégoriel étendu: application au coréen et au français avec une réalisation informatique. [Ph.D. dissertation]. Paris Sorbonne.

- Kubota, Y. (2007). A Multimodal Combinatory Categorial Grammar analysis of –te form complementation. Colloque de syntaxe et sémantique. Paris.

- Maritxalar, M., Diaz de Ilarraza, A., & Oronoz, M. (1997). From psycholinguistic modelling of interlanguage in second language acquisition to a computational model. In T. M. Ellison (Ed.), CoNLL97: Computational natural language learning (pp. 50–59). ACL.

- Paradis, J. (2004). The relevance of specific language impairment in understanding the role of transfer in L2 acquisition. Applied Psycholinguistics, 25(1), 67–82.

- Parslow, N. L. (2015). Automated Analysis of L2 French Writing: a preliminary study. [Master dissertation]. Université de Paris Diderot, Paris 7.

- Pentus, M. (1993). Lambek Grammars are Context-free. Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Logic in Computer Science. Montreal.

- Pienemann, M. (1992). COALA - A computational system for interlanguage analysis (Report). Second Language Research, 8(1), 59–92.

- Pirvulescu, M., & Hill, V. (2012). Object clitic omission in French-speaking children: Effects of the elicitation task. Language Acquisition, 19(1), 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10489223.2011.634660

- Pirvulescu, M., & Strik, N. (2014). The acquisition of object clitic features in French: A comprehension study. Lingua, 144, 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2013.12.006

- Scheidnes, M., Tuller, L., & Prévost, P. (2020). Object clitic production in French-speaking L2 children and children with SLI. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 11(2), 259–288. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.18086.sch

- Selinker, L. (1972). Interlanguage. IRAL - International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 10, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.1972.10.1-4.209

- Steedman, M. (2000). The syntactic process. MIT Press.

- Steedman, M., & Baldridge, J. (2011). Combinatory categorial grammar. In R. D. Borsley, & K. Börjars (Eds.), Non-Transformational syntax : Formal and explicit models of grammar (pp. 181–224). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Towell, R., & Hawkins, R. (1994). Approaches to second language acquisition. Multilingual Matters.

- Wust, V. (2010). L2 French learners’ processing of object clitics: Data from the classroom. L2 Journal, 2(1), https://doi.org/10.5070/l2219061