ABSTRACT

Background. Although China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has received increasing attention at the global level, there is, however, little information about how and with what implications it is being enacted on the ground. This is partly because existing scholarship has primarily focused on Chinese interests and motives behind the grand proposal, while perspectives of other countries participating in the BRI remain understudied.Purpose. The study seeks to bridge this gap by contextualizing the land-based component of the BRI, Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB), in Central Asia. Its purpose is two-fold: (1) to discuss how Beijing perceives the role of Central Asia in general and Kazakhstan in particular in advancing its New Silk Road proposal; (2) to explore how the SREB is being implemented and perceived in Kazakhstan, where it was first announced in September 2013. In particular, it offers a detailed account of how Kazakhstan is trying to integrate its infrastructure development program “Nurly Zhol” for 2015-2019 into the SREB, which is missing from the current scholarly literature. Main Argument. The paper argues that, notwithstanding power asymmetries, the BRI participant/recipient countries do have the agency to develop their own agenda and relevant policies for interactions with Beijing. Conclusion. The case study analysis suggests that there is little evidence that China unilaterally imposes its agenda upon Kazakhstan. Moreover, a shared understanding between the two states about the complementarity of mutual interests provides a solid foundation for overall Kazakh-Chinese cooperation. Yet, the strengthening of relations between the two neighbors, especially in the economic domain, has not led to an improvement of Kazakh popular perceptions of China, whose image is further worsened by the ongoing securitization of ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, including Kazakhs.

1. Introduction

Given the possibility that President Xi Jinping will stay in power after his second presidential term ends in 2023, his Belt and Road Initiative (“Yidai, yilu” in Chinese, hereafter the BRI), sometimes referred to as the New Silk Road, will most likely continue to be pursued as the centerpiece of China’s foreign policy and domestic economic strategy for at least another decade. Consisting of two parts – Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road – BRI is now enshrined in a new version of CPC Constitution (as amended in October 2017), which underpins its importance to the Xi administration.

Although the BRI received little attention when its land and sea components were first announced in Kazakhstan and Indonesia, separately, in September–October 2013, there has been considerable discussion about China’s strategic and economic motives behind its new grand initiative (i.e. why-questions)Footnote1 as well as discursive practices, operational approaches, and mechanisms – both old and new – that Beijing uses and/or draws on to advance the BRI agenda both at home and abroad (i.e. how-questions).Footnote2 Many scholars and pundits commonly point to the overstretching and vagueness of the BRI concept. As the initiative was set up to promote connectivity along the New Silk Road in five key areas – policy coordination, infrastructure connectivity, trade facilitation, financial cooperation, and people-to-people contacts, it incorporates under its ever-expanding umbrella virtually all of China’s diplomatic and economic activities. Even past achievements and successes that predate the launch of BRI are sometimes encompassed under the BRI banner. Despite or perhaps because of this all-encompassing conceptual framework, the BRI has neither clearly articulated concrete objectives nor specific time frame, which, however, provides sufficient space and flexibility to serve multiple purposes of the Chinese foreign policy. After all, the Chinese official discourse insists on presenting the BRI not as a strategy, agenda, or project but as an initiative (changyi).Footnote3

Meanwhile, it is widely acknowledged that BRI is the top-level design for China’s foreign relations, closely linked to its national development agenda, and the state plays a leading role in mobilizing all available resources (financial, human, intellectual, etc.) for its implementation.Footnote4 It is also increasingly acknowledged that one should not undervalue the possible impacts – both positive and negative – the unfolding of the BRI may have for its participant (or recipient) states as well as for international governance.Footnote5 In particular, the recent debates raise the question of whether the cooperation between China and other (much smaller) nations within the BRI framework or the BRI’s goal, a “community of common destiny” (mingyun gongtongti), is and/or will be a “win-win” based on the principles of “equality and mutual benefit.”Footnote6 This question is embedded at the heart of the ongoing debate on the trajectory of China’s rise. Although probably there can be no definite answer to this question (at least anytime soon), however, in order to gain a better understanding about the present state and possible future trajectories of the interactions within the BRI, more empirical research should be done. Moreover, greater scholarly attention should also be directed to the perspectives of the regions and nations participating in the BRI (their interests, policies, perceptions, etc.), because most existing scholarship has primarily focused on the Chinese perspective and therefore does not provide us a richer and more nuanced picture of the dynamics, contours, and effects of the BRI-related moves on the ground.

The present study seeks to bridge this gap by contextualizing the land-based SREB in Central Asia. Its aim is two-fold: (1) to discuss how Beijing perceives the role of Central Asia and especially Kazakhstan in developing the SREB (see Section 2 of this paper) and (2) to explore how this grand proposal is being enacted and perceived in Kazakhstan, the SREB’s key partner (zhongdian hezuo guojia) (see Section 3 of this paper). In so doing, it seeks to contribute to a political analysis by providing a more nuanced and comprehensive picture of current Sino-Central Asian interactions that have yet to be sufficiently addressed in the existing literature.

Most experts agree that the SREB has become a “term accentuating China’s existing economic and strategic relationships” in Central Asia,Footnote7 while recognizing that “a new dynamic has been unleashed and cooperation has reached new levels, at least in terms of the number of contracts signed.”Footnote8 Recent research has extensively focused on geopolitical and geo-economic factors behind the current Sino-Central Asian engagement – i.e. great power relations, national and regional security, infrastructure projects and regional connectivity, bilateral trade, etc.Footnote9 (just as at a time prior to the launch of the BRI), whereas much less attention has been paid to the ways in which these interactions take place and evolve.Footnote10 Moreover, although the BRI may accelerate the consolidation of Beijing’s overall foreign policy approach toward Central Asia,Footnote11 China’s engagement in the region is not a one-way road but rather a process of constant negotiation and bargaining in which Central Asian states are not passive bystanders but proactive agents working to affect the course of the “game.” Yet, hitherto, there have been very few studies tracing these processes on the ground, which gives us only fragmentary clues to such complex and multifaceted phenomena and their possible outcomes. This is, however, partially explained by limited access to publicly available information, as BRI-related projects – especially at their initial stages – often lack transparency.

This paper therefore attempts to uncover the complex nature of how the “New Silk Road” is being jointly built in Central Asia by using Kazakhstan as a case study. The author fully acknowledges that the importance and agency of the Central Asian states in dealing with the SREB differ significantly across the region, and therefore Kazakhstan’s case cannot be representative for the whole Central Asian region. Nevertheless, it informs us about some principles, practices and patterns that are common for China’s engagement with Central Asia and beyond. As Gerring has put, a single case study is not a tout court but “a single example of a larger phenomenon.”Footnote12 It is “a useful means to closely examine the hypothesized role of causal mechanisms in the context of individual cases,” as argued by George and Bennett.Footnote13 In order to strengthen causal inference, the paper employed data triangulation by using multiple sources of primary and secondary data published or obtained via interviews in Kazakhstan and China.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 seeks to address the following questions: What strategic and economic significance does Central Asia have for Chinese policymakers in safeguarding and implementing the land component of the BRI? What implications did the launch of SREB have on Chinese thinking about Central Asia? Why does China perceive Kazakhstan as the SREB’s key cooperation partner in the region? I argue that, with the launch of the BRI, the strategic importance of Central Asia has increased in the Chinese foreign policy thinking, largely due to the region’s geographic location in the middle of Eurasia and in close proximity to China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (hereafter Xinjiang) that has designated as the “core area” (hexin qu) of the SREB. In this regard, Kazakhstan’s importance is particularly apparent. This Central Asian nation not only demonstrates the potential to become a major trans-Eurasian transport and logistics hub along the SREB, but it is also Xinjiang’s foremost partner in both security and economic matters. Moreover, Kazakhstan is Moscow’s closest partner in a given region and a co-founder of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), which is certainly taken into account in Beijing as well.

But Kazakhstan was chosen for the case study not only because of its strategic importance as a crucial nodal point for China’s “march westwards” (Xi jin),Footnote14 but also because of its role of being a trailblazer in shaping contours and “stuffing-up” the obscure New Silk Road proposal with concrete measures and time frame in the region and even among the countries along the BRI. The KazakhFootnote15 government was quick to respond positively to the Chinese initiative by integrating its infrastructure development program “Nurly Zhol” (“Bright Path” in English, BP hereafter) for 2015–2019 into the SREB.Footnote16 However, a detailed account of such coordination between the BP and SREB is missing from the current scholarly literature. Section 3 therefore seeks to shed light on the content and progress of the SREB-related moves in Kazakhstan as well as to explore how the current engagement with China is perceived in Kazakh society. The central argument here is that, notwithstanding power asymmetries, the BRI participant/recipient countries do have the agency to set their own priorities and develop their own agenda and relevant policies for interactions with Beijing, and the case of Kazakhstan serves as a good illustration to this. At the same time, though, the lack of transparency in interactions between Kazakhstan and China makes it difficult to assess accurately the benefits and costs that accrue to various interest groups in Kazakhstan, which, in turn, contributes to growing concerns about the potential negative impacts of China’s increased economic linkages on the country.

The conclusion section reflects on the findings from previous sections and offers a tentative answer to the question of whether Kazakhstan–China engagement under the BRI rhetoric is a win–win.

2. Contextualizing the SREB in Central Asia: a Chinese perspective

This section discusses why Central Asia is important in the Beijing eyes, whether, or how, the launch of the BRI strategy impacts Chinese thinking of the region, and why China sees Kazakhstan as the SREB important partner. It thus seeks to present an overview of Chinese perspectives about Central Asia’s role and place in the unfolding of the SREB in Eurasia.

2.1. Why is Central Asia important for China?

The Central Asian region does not rank high in the list of Beijing’s foreign policy priorities, and China’s trade with five Central Asian countries still represents only about 1% of its total foreign trade.Footnote17 Unequivocally, the Asia-Pacific region has been and still remains the top priority in Chinese foreign policy in both strategic and economic dimensions. Nevertheless, the strategic significance of Central Asia to China should not be underestimated at least with regard to the following aspects.

2.1.1. The Xinjiang factor

First, Central Asia’s importance lies in its geographic location, which makes the region an integral part of China’s surrounding areas and thus a target of Chinese diplomacy toward neighboring countries (zhoubian waijiao). The region’s strategic value becomes evident even more due to its geographic proximity to and close historical and cultural ties with Xinjiang, the PRC’s largest administrative unit and frontier territory with a complex ethnic composition, which, along with Taiwan and Tibet as well as later added China’s maritime territorial claims in the South China Sea, constitutes what Beijing refers to as “core interests” (hexin liyi) related to the matter of national sovereignty and territorial integrity.Footnote18 Chinese policymakers think that a stable external environment is necessary for safeguarding security and economic development of Xinjiang and thus the territorial integrity of the PRC. Specifically, the Central Asian-Chinese border, about 3300 km, constitutes over half length of Xinjiang’s international border (which total length is over 5600 km),Footnote19 while Xinjiang’s trade with the Central Asian region accounts for over half of its total foreign trade.Footnote20 Xinjiang’s importance in China’s Central Asia policy is well illustrated by Beijing’s role in the establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO),Footnote21 for which the main driver at the time was China’s purpose to secure regional cooperation in tackling the so-called “three evils” – religious extremism, ethnic separatism, and international terrorism.Footnote22

2.1.2. Russia’s presence

Second, Central Asia is of particular importance with regard to Chinese diplomacy toward major powers (daguo waijiao), because, in a given region, China needs to come to terms with Russia, which regards the territory of the former Soviet Union (including the Central Asian region) as its “area of special interests.” The Kremlin fears that China’s increasingly formidable economic presence in the Central Asian region will translate into increased political influence at the expense of Russia, especially if combined with the decline in loyalty of the Central Asian states to Moscow. This is probably best reflected in Russia’s obstruction of China’s initiatives to expand the economic component of the SCO, such as establishing a Regional Development Bank or Anti-Crisis Fund. China is well aware of such sensitivity on the Russian side.Footnote23 Beijing recognized Moscow’s “special status” at the very outset of its engagement in the region while simultaneously expanding the scope of its ties with Central Asian countries through bilateral agreements. Meanwhile, Russia increasingly realized that it is not in a strong position vis-à-vis China’s economic power. On the basis of this understanding, the two major powers have so far managed to establish a certain Sino-Russian division of labor in the region: whereas China’s major advances in the region have come in the economic realm, Russia keeps its preeminence in the political, military and, importantly, cultural realms.Footnote24

2.1.3. Energy resources and pipelines

Third, Central Asian hydrocarbon resources are of crucial importance to Beijing regardless of the SREB’s progress. China has built its first international oil pipeline that directly imports crude oil from Kazakhstan, where Chinese companies hold a significant stake in the oil sector. It has also built three lines (A, B, C) of the Central Asia-China gas pipeline (CACGP) that runs from Turkmenistan via Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan to Khorgos in China’s Xinjiang. Here, I want to specifically highlight that natural gas imports from abroad are of increasing importance to the Chinese state, which is intensifying its purchases of overseas supplies in order to combat air pollution, probably the most serious social problem confronting the ruling party at the moment. The CACGP, too, is the first gas pipeline built by China, and its first line (A line), with designed capacity 30 billion cubic meters a year (bcm/year), began operation in December 2009. Line B (30 bcm/year) and Line C (25 bcm/year) began operation in October 2010 and May 2014, respectively.Footnote25 The construction of Line D is planned. According to the China National Petroleum Corporation, Chinese imports of Central Asian gas – mainly from Turkmenistan – account for over 15% of total Chinese gas consumption, which ensures gas supply to about 300 million Chinese citizens.Footnote26 For instance, when shipments of Central Asian gas (from all three countries – Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan) dropped in January 2018, China’s winter gas shortage was significantly worsened so that Beijing was forced to increase its LNG purchases from Qatar. In the meantime, Kazakhstan agreed to increase its gas supplies to China from 5 to 10 bcm/year.Footnote27 Thus, put shortly, Central Asian gas supplies have the long-term strategic importance for China.

2.2. The SREB’s implications for China’s Central Asia thinking

So, what implications did the launch of the BRI have for Beijing’s thinking of its western neighbors? As China’s leading Central Asia and Russia scholar Zhao Huasheng has noted, there is a continuity (yi mai xiang cheng) between the SREB and China’s Central Asia policy prior to the BRI’s announcement, as the “five connectivities” proposed by the SREB did not start from scratch but based on the previous foreign policy strategies and practices.Footnote28 However, from a strategic point of view, the new grand initiative has certainly enhanced Central Asia’s significance, since the region’s geographic location – its location in the middle of the Eurasian continent and in close proximity to China’s Xinjiang – now holds greater value in the eyes of Chinese policymakers with respect to both external and domestic components of the BRI.

2.2.1 Central Asia and the Xijin strategy

Firstly, given that one of the most clearly articulated goals of the BRI is to diversify China’s land and sea connections with countries throughout Afro-Eurasia, Beijing now appears to pursue omnidirectional foreign policy by placing greater focus on periphery diplomacyFootnote29 that is increasingly “‘rebalancing’ westwards.”Footnote30 To put more accurately, as Li Mingjiang has pointed out, the BRI “represents a major substantive move” in the emerging new strategic thought “Act West” (xijin, sometimes also translated as “March West”).Footnote31 XijinFootnote32 was proposed by Wang Jisi, Dean of the School of International Studies at Peking University and China’s one of the most influential America scholars, who called China for rebalancing its geopolitical strategy westwards following the Obama administration’s announcement of the “pivot to Asia.”Footnote33 It is however important to note here that Wang did not propose to abandon China’s East Asia policy vector, but he rather suggested to “rebalance” Chinese geopolitical thinking in order to pursue a new overarching strategy that “carry on both land power and sea power at the same time” (luquan yu haiquan bing xing bubei de). As the BRI’s composition of the land and sea routes suggest, Xi indeed decided to pursue both directions. In this new thinking, therefore, Central Asia is naturally perceived as both entrance doors and a first stop on China’s Xijin. Moreover, compared with Afghanistan and Pakistan, as a scholar from Xinjiang Sun Hui notes, Central Asia represents a more stable environment in China’s immediate western neighborhood,Footnote34 and officials in Beijing are surely well aware of it.

2.2.2 The Central Asia-Xinjiang nexus

Furthermore, the BRI should not be regarded as a solely counter-hedging strategy in the Asia-Pacific, since domestic development is one of the most important factors, if not the most important, in shaping the direction of this grand proposal. As noted in the beginning, one of the key objectives of the BRI is to help address the country’s regional development disparity by giving a substantial boost to the “Great West Development Program” in general and by designating Xinjiang as a “core area” of the SREB in particular. More specifically, this frontier region is supposed to become a hub for three out of the six proposed economic corridors – namely, the New Eurasian Land Bridge (NELB), the China-Central Asia-West Asia corridor (CCAWA), and the China-Pakistan economic corridor. Importantly, one should not overlook the role and agency of Xinjiang itself in promoting its “core area” status and its position of being “the bridgehead of opening to the west” (xiang xi kaifang de qiaotoubao) along the New Silk Road by putting forward an idea and then a set of concrete plans to build “five centres, three bases, and one corridor” (wu zhongxin, san jidi, yi tongdao) in the region.Footnote35 Therefore, I argue that Central Asia holds strategic value for China’s opening to west from both central (Beijing) and local government (Xinjiang) perspectives. For instance, Sino-Central Asian oil and gas pipelines and railway connections are Xinjiang’s only existing operational international pipeline and rail links. This advantage of the Central Asian region with regard to the BRI’s objective to intensify regional interconnectivity and to facilitate trans-continental trade is certainly taken into account by the current inhabitants of Zhongnanhai in their policy calculations.

However, there is the other side of the coin to remember as well: Xinjiang’s continued opening-up of the economy is combined with the intense securitization process, especially since Chen Quanguo, former party chief in Tibet, stepped in as the new leader of Xinjiang in August 2016. What is particularly remarkable in this worsening situation is that the Chinese authorities began to systematically persecute ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, including Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, by sending them to the so-called “re-education camps” not only because of the real and/or perceived threats of the abovementioned “three evils,” but also for “politically incorrect” views. This new security policy is negatively affecting the interaction between ordinary citizens between China’s Xinjiang and the Central Asian states in the first place. Such tightening control stands in sharp contrast to the Chinese official rhetoric that declares promotion of people-to-people bonds as one of the BRI’s five major goals,Footnote36 so that its discursive legitimation in Central Asia’s societies appears to be rather difficult.

2.2.3. Russia and the SREB

Finally, Chinese SREB’s Eurasian ambitions, with Central Asia placed at its center, certainly have implications for both the Sino-Russian relationship in the Central Asian region in particular and Moscow’s reconsideration of its own interests and ambitions in Eurasia in general. Beijing’s announcement of its grand project in Astana without informing Russia beforehand seemed to have caused some uneasiness in Moscow, at least in the beginning.Footnote37 In particular, Russia was concerned over whether China’s SREB would hamper the further development – both an institutionalization and an enlargement – of the ongoing Eurasian integration project which would finalize its formation as the EEU only in the years 2014 and 2015. On the other hand, Chinese policymakers probably think that the unfolding of the SREB in Central Asia does not contradict the unwritten rules of the abovementioned Sino-Russian division of labor, as the Chinese grand initiative is predominantly positioned as a development proposal with a major focus on economic matters. Moreover, importantly, the SREB did not propose an objective of building a free economic zone (FEZ), at least for the time being. According to Zhao, it is not only deemed unrealistic to build a FEZ in such a vast territory along the SREB, but it also shows that China wants to avoid contradiction with the Moscow-led Eurasian Union.Footnote38

However, the deterioration of Russia’s relations with the West following the annexation of Crimea has left Moscow little choice but to bandwagon with the Chinese Eurasian plan by proposing the linking up of the EEU and the SREB.Footnote39 Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, the Russian government views China’s BRI through the prism of its resentment toward the West (especially, the US), portraying “Russo-Chinese Eurasian partnership” as a counterbalance to the US hegemony.Footnote40 Interestingly, in contrast to Russia, China understands that its own development depends on its integration into the global economy and especially its access to Western technologies, although the current China-US trade skirmishes serve to intensify the Chinese leadership’s efforts to develop indigenous innovations in order to reduce its reliance on Western (in particular, American) markets. Nevertheless, it is clear that China seeks to build stronger connections with dozens of economies across Afro-Eurasia and beyond by putting forward the BRI. Therefore, Moscow’s support for the BRI serves China’s interests not only to keep cooperative relationship with Russia in their common Central Asian neighborhood but also to engage Russia in the New Silk Road agenda with broader relevance.Footnote41

2.3. Kazakhstan: the SREB’s key cooperation partner

It seems to be no mere coincidence that President Xi chose Astana to announce the SREB in his historic speech at Nazarbayev University in September 2013. This section therefore focuses on the question of why Kazakhstan (among other Central Asian states) is important to Xi’s proposal from the Chinese perspective by discussing a combination of geopolitical and geo-economic reasons.

2.3.1. Transportation interconnectivity

First and foremost, as “the entrance doors to west” on China’s march westward, located literally between Europe and Asia, Kazakhstan serves as an increasingly important bridge connecting China with Europe (Russia), the Caucasus, and Western Asia through both land and the Caspian Sea. This strategic quality is only reinforced by the country’s terrain of vast flat land areas combined with relatively decent transport infrastructure, which gives great advantage to Kazakhstan over other China’s neighbors to the west – Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and to some extent Pakistan – due to their topographic features and poor infrastructure. For instance, in his analysis concerning the three economic corridors traversing Xinjiang, Pan Zhiping, China’s veteran scholar on Central Asia and former director of Xinjiang Academy of Social Sciences highlights that the China-Kazakh economic corridor is the most promising part of the CCAWA.Footnote42 Abovementioned Zhao Huasheng goes even further, stating that “Kazakhstan is located on a main axis of the SREB’s land corridor, so that if it is obstructed it will also be difficult to run smoothly for the SREB as a whole.”Footnote43

Of particular importance in this regard is Sino-Kazakh railway connectionsFootnote44 – the only existing railway links from China westward via Xinjiang, which constitutes a key element of the middle corridor of the regular direct China-Europe rail freight (CERF) services, which are dramatically increasing in frequency.Footnote45 Having said that, however, for China, the economic profitability or efficiency of the CERF seems to be a long-term goal, since most of these freight trains “return to China with their containers empty,” so that such services are heavily subsidized by the Chinese government (mainly at the local level).Footnote46 In other words, the current state over the CERF services suggests that geopolitics overshadows geo-economics in Beijing’s calculus, although it is unclear how long China can sponsor such economically irrational policy.

But Kazakhstan’s importance is not limited to its linchpin role in strengthening regional interconnectivity (hulian hutong) via the railway: roads and pipelines are also of strategic significance. The “West Europe-West China” international highway corridor (WE-WC highway) is a good example. Its construction began in 2009, and the highway corridor is planned to run from the port of Lianyungang, on the Yellow Sea in China, to the port at St. Petersburg, on the Baltic Sea in Russia, spanning 8,445 km. China and Kazakhstan completed their parts of the WE-WC highway in November and December 2017, 3425 and 2787, respectively, whilst the Russian section, 2233 km, is expected to be completed in 2018.Footnote47 In addition, and no less importantly, Kazakhstan is a central link of Central Asian-Chinese energy connectivity, because all oil and gas pipelines from Central Asia pass through Kazakhstan to enter the Chinese territory. Unsurprisingly, thus, the SREB’s two proposed economic corridors – the NELB and the CCAWA – run through Kazakhstan’s territory.

2.3.2. Kazakhstan as Xinjiang’s major partner

Kazakhstan also holds the utmost importance for China’s zhoubian diplomacy in Central Asia, as it is Xinjiang’s foremost partner in both security and economic matters. The Kazakh-Chinese border is 1783 km long, which is Xinjiang’s longest international border and nearly half the length of the Central Asian-Chinese border.Footnote48 There are five land border crossings currently operating along this borderline, whilst two of them are connected by both roads and railways.Footnote49 To add, over 20 transboundary rivers flow across Kazakh-Chinese border, and the sustainable management and protection of them create the potential for both tension and cooperation between the two countries. Kazakhstan’s significance for Xinjiang’s economy should not be overlooked as well. In 2015, for example, Xinjiang’s trade with Kazakhstan alone accounted for about 30% of its total foreign exports and imports as well as for over half of its overall trade with the Central Asian region.Footnote50

Kazakhstan and Xinjiang are also connected by cross-border populations and their migrations. Meanwhile, the largest overseas Kazakh community – about 1.59 million people as of 2015Footnote51 – resides in Xinjiang, whilst Kazakhstan is home to the largest Uyghur diaspora with a population of about 261,000 people as of the beginning of 2017.Footnote52 The abovementioned ongoing securitization in Xinjiang has direct impact on them. In particular, China’s Kazakhs are under increasing pressure for having “foreign contacts” abroad (i.e. relatives and friends in Kazakhstan). There have even been cases reported in which Xinjiang-born Kazakhs who currently reside in Kazakhstan (some with Kazakhstan’s citizenship) were detained and sent to re-education camps during their short-term visits to China.Footnote53 Although Beijing’s sensitivity over Xinjiang-related issues suggests that the normalization of grassroots cross-border contacts is not likely to happen very rapidly, but China also cannot ignore growing discontent in Kazakh society over the current situation of their co-ethnics in Xinjiang, as Kazakhstan’s officials (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) began to raise the Kazakh diaspora issue at talks with their Chinese counterparts.Footnote54

2.3.3. Kazakhstan in the Eurasian geopolitics

From the viewpoint of major power diplomacy, Chinese policymakers have always taken into account Kazakhstan’s geopolitical importance due to its strategic location between China and Russia. For instance, prominent Chinese scholar Xing Guangcheng describes Kazakhstan as a “strategic buffer” between the two major Eurasian powers.Footnote55 Moreover, for both geographical and historical reasons, Kazakhstan is also Moscow’s number one partner in Central Asia and a co-founder of the EEU. In particular, Kazakhstan is of critical importance for the EEU’s enlargement in the region as it connects Russia with the rest of Central Asia – more specifically, Kyrgyzstan, the EEU member and further Tajikistan, the candidate for accession to the EEU. In this regard, one should not forget that at the time of Xi’s announcement of the SREB in September 2013, Kazakhstan was the only Central Asian participant of the then Eurasian Economic Space (EES), now the EEU,Footnote56 and thus the only country in the region that could provide China with direct access to common market of the Russia-led Eurasian economic integration.

Moreover, Kazakhstan’s special place in Eurasian geopolitical space is defined not only by specific geographic settings but also by Astana’s agency in creating this geopolitical landscape. As well known, an idea of economic integration in post-Soviet space, the Eurasian concept, was first enunciated (already in 1994) and staunchly supported by President Nazarbayev. Kazakhstan also played an important role in continuation of the Shanghai Five process by insisting on holding the 1998 Almaty Summit, which marked a turning point in further enhancing of cooperation agenda between China and its post-Soviet neighbors.Footnote57 Importantly, the term “Greater Eurasia” – which has later developed into the flagship concept of Russia’s geostrategic policy – was first introduced to the political lexicon by President Nazarbayev, when he called for “rallying around the idea of Greater Eurasia that will unite the EEU, the BRI and the EU into one integration project of the 21st century” at the UN Sustainable Development Summit in September 2015.Footnote58

3. How is the SREB being enacted in Kazakhstan? Toward a synergy of Kazakh-Chinese developmental strategies

Zhao Huasheng wrote the following comments with regard to the role of the SREB participants in Central Asia:

For the SREB, it is more important to have Central Asian states not as mere participants but as its ardent supporters and promoters (reqing zhichizhe he tuidongzhe). In other words, China should make Central Asia states its ‘allies’ (‘tong meng jun’) but not merely objectives (duixiang) in building the SREB.Footnote59

Seen in this light, Kazakhstan’s stance toward the SREB should thus be of particular significance for the Chinese leadership, due to the country’s strategic properties discussed in the previous chapter. So, is Kazakhstan a mere objective or an ally in building the SREB? This chapter argues that Kazakhstan is rather China’s “tong meng jun” by presenting a detailed account of Astana’s response to the SREB. Specifically, it explores why and how Kazakhstan coordinating its national development with the SREB as well as how such efforts are perceived in Kazakh society.

3.1. Kazakhstan’s response: the Nurly Zhol – SREB linking-up

On May 22, 2012, in his closing remarks at the 25th meeting of Kazakhstan Foreign Investors’ Council, Kazakh President Nazarbayev stated the following: “Today I want to propose to jointly launch the large-scale project, the ‘New Silk Road’. Kazakhstan must revive its historic role and become the largest business and transit hub of the Central Asian region as well as a unique bridge between Europe and Asia.”Footnote60 The proposal has placed a strong emphasis on infrastructure development projects along the east-west direction (most of them were already underway), which naturally indicates the particular importance of cooperation and coordination on transport matters between Kazakhstan and its eastern neighbor, China. There is, however, nothing particularly novel about this proposal, both conceptually and operationally: Kazakhstan has long used the Silk Road metaphor to articulate its historical interconnectedness with China as well as its land bridge function connecting different parts of the Eurasian continent. Symbolically, the first train that traveled from Almaty (the then capital of Kazakhstan) to Urumqi via Alashankou on 20 June of 1992 was named “Silk Road.”Footnote61 Needless to say, since then, Kazakhstan and China have developed close cooperation in transport and energy infrastructure connectivity matters, and all large-scale infrastructure projects between the two neighbors started before the BRI was announced. It is therefore unsurprising that Kazakhstan welcomed the SREB from the very beginning: Xi’s proposal not only perfectly matches Kazakhstan’s self-perception of being a linchpin of the modern Silk Road, but also fits well with Kazakhstani government’s consistent efforts to upgrade domestic transport infrastructure and effectively integrate it into international transport systems.

But what is particularly outstanding about the Kazakh case is that Astana went well beyond a mere passive response to the Chinese grand proposal and exercised active agency to fill it with a concrete plan. Specifically, Kazakh leadership proposed to link up (úilestīru in Kazakh, duijie in Chinese) the country’s domestic developmental program “Nurly Zhol” (BP) to the SREB. Of peculiar importance here is that this linking-up not only focuses on transportation infrastructure connectivity matters, but also initiates a coherent plan to organize industrial cooperation between the two countries on a broader range of areas such as metallurgy, agriculture, chemical industry, machinery manufacturing, and so on (see ).

Table 1. China’s trade turnover with Kazakhstan and Central Asia, Unit: Billion, USD.

Table 2. Kazakh-Chinese joint projects.

So what were Kazakhstan’s motives and interests in the BP-SREB linking-up? To better understand them, it is necessary to briefly elucidate here on what the BP plan is and why it was adopted. The BP plan was first announced in a presidential address in November 2014 and confirmed as ‘the state program for infrastructure development for 2015-2019ʹ in April 2015. Accompanied by a number of separate programs in various areas,Footnote62 the BP aims to create a single economic market in Kazakhstan by integrating the country’s macro regions through the construction of an effective infrastructure based on the hub principle to ensure sustainable and long-term growth.Footnote63 The sharp decline in oil prices since mid-2014 and the resultant deterioration of Kazakhstan’s oil-dependent economy were the main drivers behind the adoption of these measures. In this regard, Kazakh expert on China Kaukenov’s following remarks appear to echo the Kazakhstan government’s stance: “In the face of internal capital shortage that is forcing [the government] to wind down all initiatives for the coming years, China can become a lifesaver for the Nurly Zhol.”Footnote64 In other words, Kazakhstan sees the SREB initiative as an opportunity to acquire new capital inflows and new technologies which are now urgently needed to carry out the country’s developmental reforms and programs.

Thus, just a few months after the BP’s official adoption, Astana and Beijing took a first step toward the BP-SREB linking-up. During President Nazarbayev’s visit to China in August 2015, a Kazakh-Chinese Joint Declaration on the new phase of the comprehensive strategic partnership was signed, in which the two leaders stressed the complementarity (xiang fu xiang cheng) of the BP and SREB.Footnote65 Then, in December of the same year, the heads of government of the two countries announced the launch of the BP-SREB coordination, and a joint working group between Kazakhstan’s Ministry of National Economy and China’s National Development and Reform Commission (CNDRC) was established to draft a plan for synergizing the two countries’ developmental strategies.Footnote66 In September 2016, when Kazakhstan’s delegation visited Hangzhou during the G-20 summit, the joint plan was finally signed. It highlighted the three priority sectors of bilateral cooperation: transport infrastructure, trade, and manufacturing industries, which I will discuss in more detail further in the paper.

3.2. Mechanisms and platforms

An important aspect to mention is the establishment of special negotiation bodies – new mechanisms and platforms – by the two countries in order to effectively carry out the linking-up coordination.Footnote67 Arguably, the Kazakh-Chinese Coordination committee on industrial and investment cooperation (hereafter the CCIIC), co-chaired by Kazakhstan’s Ministry for Investments and Development and CNDRC, has become a major body for working-level talks between the parties. The CCIIC is responsible for preparing a list of joint investment projects and organizing overall coordination of the activities between the involved organizational structures. This mechanism was officially established in August 2015,Footnote68 but it took its origin in a meeting between Kazakhstan’s Prime Minister Karim Massimov and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang in December 2014 in Astana. So far, 15 meetings have already been held, and a list of joint projects has been presented (which will be discussed in the following section).

Another example is the Kazakh-Chinese Business Council (KCBC) that was established at the instruction of Presidents Nazarbayev and Xi during the latter’s visit to Kazakhstan in September 2013 when the SREB was first aired. This structure aims to provide a dialogue platform between Kazakh and Chinese business communities and is co-chaired by Kazakhstan’s National Welfare Fund “Samruk-Kazyna” (Samruk-Kazyna) and China Council for Promotion of International Trade. For instance, during the latest 5th meeting of the KCBC on June 8, 2018, a total of 40 business agreements were signed between the two countries’ business representatives, for a value of 13 billion USD.Footnote69 Without doubt, support for the coordination of Kazakh-Chinese developmental strategies at the highest level – at the level of heads of state – plays a crucial role in framing the policies and facilitating more or less coherent actions but also in speeding up the decision-making process.

Finally, it is worth noting here that the current Kazakhstan-China cooperation under the SREB banner has been primarily bilateral in nature, even though both countries engage in multilateral cooperation within the EEU-SREB linking-up framework. From a conceptual viewpoint, there was a lack of understanding about the BRI at the initial stage, probably not only among the EEU members but also even in China, especially in regard with Russia’s place in the SREB (Central Asia has, however, been presented as the SREB’s key partner from the very outset). Moreover, the linking up between the two Eurasian projects – the EEU and SREB – was initiated by Russia in a unilateral manner, without coordination with other EEU members, in the spring of 2015.Footnote70 This unilateral act was perceived by Moscow’s EEU partners as disregard for their interests, which is especially relevant for Kazakhstan since this country perceives itself as both a key member of the EEU and a key partner of the SREB in Central Eurasia. But at the same time, Moscow’s official embrace of the Chinese initiative was interpreted or/and employed as “a welcome reception” of the SREB-related moves in the EEU space, so that other EEU member states were encouraged not to shy away from advancing their cooperation with the SREB at the bilateral level.

From an operational viewpoint, this is because the two parties (Kazakhstan and China) find the bilateral approach more effective not only in terms of its flexibility to accommodate a wider variety of areas of cooperation at a faster pace, but also with regard to its output. The efficiency of bilateral approach is especially remarkable when compared to multilateral cooperation within the EEU-SREB framework. Although the recent developments around the EEU-SREB linking-upFootnote71 suggest that the EEU members and China all understand that multilateral cooperation in Central Eurasia is needed to enhance connectivity across the region and benefit all interested parties, no substantial results have yet been produced.

3.3. Priority areas of the BP-SREB linking up: progress and hurdles

3.3.1. Transportation infrastructure

The abovementioned join plan for BP-SREB linking-up states that, in order to strengthen Kazakh-Chinese cooperation in transportation infrastructure interconnectivity, the two countries put efforts to promote the building of international transport corridors transcending both countries – such as “China-Kazakhstan-West Asia,” “China-Kazakhstan-Russia,” and “China-Kazakhstan-South Caucasus/Turkey-Europe,” upgrade their transportations systems, increase rail and road capacity, enhance logistics capacity of the Lianyungang terminal and further develop the Khorgos International Border Cooperation Centre (KIBC), actively support the participation of business in the construction and modernization of road and rail systems as well as logistics terminals, and so on.

According to the BP, the following projects in Kazakhstan are considered to be a part of the SREB: (1) construction and/or upgrading of the railway system: e.g. the Zhezkazgan-Beineu railway, the Arqalyq-Shubarkol railway link, and the second tracks of the Almaty 1-Shu section, a new railway hub in Astana; (2) building and/or development of the logistics hubs: e.g. the Khorgos Eastern Gate SEZ, a new Caspian port at Quryq, modernization of the Aqtau port, logistics hubs in Astana and Shymkent; (3) further development of the abovementioned WE-WC highway, etc.

As often is the case with the BRI-related moves, many of these projects in Kazakhstan predate the SREB announcement, but are now encompassed under the BRI banner. Yet, it is not without reason: the implementation and/or further development of these projects are of fundamental relevance to temporal framework of the BP-SREB linking-up. Many of the projects are still ongoing. For instance, although Kazakhstan has completed the construction of the WE-WC highway within its territory, it still needs to build service stations along the road, which requires considerable amounts of funds and time. Another example is the Khorgos Eastern Gate SEZ. Launched in the Hu era, it is a new development area at the Kazakh-Chinese border which is still being built. The SEZ contains a dry port for handling cargo, railway station, warehousing facilities, KIBC, etc. To add, nearby the Altynkol’ station, a new town for the rail hub workers, Nurkent, has been built from scratch. Meanwhile, the construction of hard and soft infrastructure in a given area is still ongoing, aiming at making Khorgos into a main gateway for the SREB.

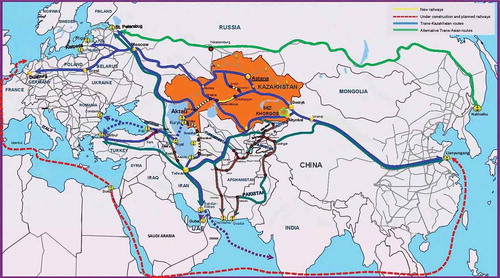

With regard to international transport corridors transcending Kazakhstan and China, the railway system plays a central role in connecting different parts of the Eurasian continent. As shown in , indeed, Kazakhstan’s transit potential is increasingly reinforced by its enhancing railway network. Of particular importance in this respect are the newly built domestic railroads such as the connections between Altynkol’ (Khorgos, at the border with China) and Almaty and between Zhezqazgan and Beineu. The former is the second railway that directly connects China with Kazakhstan’s largest city, financial and business center from where railways run to different parts of the country. The latter, built in 2012–2016 and worth 1203 million USD, is probably the most expensive among the BP-related infrastructure projects. This railroad connects the country’s central part to south-west and further accesses the ports of the Caspian Sea as well as the Persian Gulf via the newly built Ozen (Kazakhstan)-Gorgan (Iran) railway. It thus provides enhanced connectivity between the domestic and international railway systems along the “China-Kazakhstan-West Asia” and “China-Kazakhstan-South Caucasus/Turkey-Europe” international transport corridors. As for the China-Kazakhstan-Russia corridor, the fact that Kazakhstan and Russia are already closely connected through both several railroads and a single economic space provides good ground for further development of this north direction. In other words, Kazakhstan’s BP plan puts greater focus on improvement of the underdeveloped east-west connectivity of the country’s transport system in order to diversify its transit potential but also to broaden its access to international markets.

3.3.2. Optimization of trade and cooperation in the agriculture sector

It is perhaps too soon to evaluate the impact of the SREB-BP linking-up on general patterns of Kazakh-Chinese trade. As demonstrates, the trade volume between the two countries in 2015–2016 significantly decreased comparing to the previous years, largely due to the falling oil prices. As for the structure of Kazakhstan-Chinese trade, there is a well-established complementarity of the supply-demand chain between the two countries. Kazakhstan is China’s supplier of raw materials (i.e. crude oil, metals, etc.), while Chinese-manufactured goods (i.e. electronic equipment, textile products, etc.) are in demand in Kazakh society. However, there is an understanding among the Kazakhstani elites about the need of diversification of the economy and lessening the country’s (over)dependence on oil extractions. Yet, the previous governmental programs to address the issue have borne little fruit.

Against this backdrop, it is then understandable that the Kazakh government seeks to optimize and diversify the structure of its exports to China. The Joint plan has included such concerns of the Kazakh side into its agenda, according to which, the two parties agreed to stimulate and optimize bilateral trade by “increasing the share of high-tech products and coordination of certification policies.”Footnote72 Worthy of note in this respect is Kazakhstan’s efforts to achieve agreements with the Chinese side on the certificate and sanitary norms for agriculture products. Specifically, the negotiations have been held on the export of such Kazakhstani products like wheat, meat, vegetable seeds and oil, honey, etc. to the Chinese market, which is experiencing an increasing demand for organic food products. Thus, for example, in fall of 2016, China lifted a ban on the export of meat from nine regions of Kazakhstan.

Nevertheless, there are hurdles on the way as well. One of the problems often pointed out by Kazakh business representatives is the slow progress in the easing of the export regulations as well as a limited volume for the export of certain Kazakh products (such as wheat) set by the Chinese side. Moreover, there is a strong sensitivity in Kazakh society over agricultural cooperation with China, since there are growing concerns, albeit often alarmist, among the masses over the use of Kazakh lands by the Chinese. These attitudes were revealed and further reinforced during the popular protests against amendments in the land legislation that took place in spring 2016. The amendments aimed to extend the lease of farmlands by foreigners from 10 to 25 years. Notably, the demonstrations quickly mobilized large numbers of peoples and spread to several cities, making it one of the largest in the history of independent Kazakhstan. Protestors expressed their fear of the influx of the Chinese and their “harmful” environmental practices, although many of them even were not fully informed about the content and details of the new law.Footnote73 Aware of the danger of the protest escalation, the government put a moratorium on the law, while trying to silence those protesters with a proactive stance. Yet, the protests have contributed to worsening of a general image of China among Kazakhs which has not been particularly favorable from the outset.

These protests have made the Kazakh government adopt a more sensitive approach toward presenting its agricultural cooperation with the Chinese – at least in respect of the land use – to the public. Thus, already in May 2016, Kazakhstan’s deputy agriculture minister Isayeva reported that the potential Chinese investors (participants of the BP-SREB linking-up) would not be allowed to own Kazakh lands, but instead would be partnering with their Kazakh counterparts to jointly invest in the processing of agricultural products.Footnote74 As shown in , seven joint Kazakh-Chinese projects in the agriculture sector have been chosen. Kazakh business elites actively welcome partnership with their Chinese counterparts, because they offer not only investments and technologies but often an opportunity to enter the Chinese market. For example, a newly built joint venture producing vegetable oil in Northern Kazakhstan region began to export its products to China’s Shaanxi province. Another example is the construction of a meat processing factory by “EurasiaAgroHolding” (Kazakhstan) and “Rifa Investment” LLP (China) in the Eastern Kazakhstan region.Footnote75 This joint venture likewise aims to orient its production to the Chinese market. In the following, I will provide more details on the Kazakh-Chinese joint projects.

3.3.3. Building-up manufacturing capacity and Kazakh-Chinese industrial cooperation

Unlike the transport connectivity matters, cooperation between the two countries in the area of manufacturing industries has received little attention. Meanwhile, being implemented within the quickly developed mechanism of Kazakh-Chinese industrial cooperation, it has become the most dynamic component of the BP-SREB linking-up. As pointed out above, the Masimov-Li meeting in December 2014 gave a start to official negotiations in this area. Interestingly, such cooperation between Astana and Beijing has set an example for China’s engagement with other BRI participant countries, which was developed to become what is now called the Belt and Road International Capacity Cooperation (guoji channeng hezuo), also known as a “new business card” (xin mingpian) of Premier Li Keqiang’s diplomacy.Footnote76

One remarkable aspect of the development of Kazakh-Chinese cooperation in this area is the shift in the use of language in official discourse. While the term “industrial transfers from China” was used at the very outset of talks between the two countries,Footnote77 later, both governments began to increasingly use the phrase “industrial capacity cooperation” instead. What this seems to indicate is that officials on both sides seek to prevent the formation of negative images among the masses, as Kazakhstan’s public began to raise certain questions, for example, whether China’s excess production capacities are outdated and harmful for the environment.Footnote78 Furthermore, the Kazakh government’s unwillingness to make public a full list of joint projects with China (even after its finalization) only creates an informational void that is easily filled with rumor and speculation.

So what are results of the current Kazakh-Chinese industrial cooperation? An analysis of published sources – i.e. official and semi-official reports, media coverage – in both Kazakhstan and China suggests that the two governments have agreed on the list of joint projects: a total of 51 projects have been selected, valued at about 27.7 billion USD.Footnote79 As of the beginning of 2018, four projects worth 372 million USD started operation.Footnote80 shows that the joint projects are being or planned to be implemented in areas such as machinery construction, metallurgy, chemical industry, agriculture, electric power industry, and so on. Geographically, these projects are located in different regions across the country. For instance, the Zhambyl region in southern Kazakhstan hosts 7 out of 51 projects, most of which focus on development of the Chemical Park “Taraz” SEZ.Footnote81

Unsurprisingly, the Chinese investments are the major financial source for these projects, although the Kazakh side too allocates capital to the joint fund. Moreover, Kazakhstan agreed to simplify the obtaining of a labor visa for the Chinese labor force involved in the projects (especially, managing and technical staff).Footnote82 Despite these arrangements, it seems there are still some difficulties in getting a Kazakh visa, though.Footnote83 In the meantime, the Kazakh leadership seeks to provide local people with more jobs in a long-term perspective by putting massive efforts to develop the country’s industrial production capacities. According to the current Prime Minister Sagyntaev, the Kazakh-Chinese joint projects allow to create over 20,000 new workplaces for local population.Footnote84

Yet, there is a gap between the elite (political and business) and popular visions of what the Kazakh-Chinese industrial cooperation may represent for the country and its people. The abovementioned land protests are telling. Meanwhile, the tightened control over ethnic minorities, including Kazakhs, in Xinjiang only reinforces the negative popular sentiment toward China. Besides, there are shared concerns on the potential problems in the Kazakh-Chinese engagement – such as corruption, environmental damage, ownership and management of strategic assets, the repayment of the Chinese credits, and so on – across different groups of society. However, there is also an understanding that China has become an indispensable partner for Kazakhstan’s development.

4. Concluding remarks

Based on a case study of Kazakhstan, the paper has attempted to contribute to the current scholarly discussion concerning the BRI progress by presenting an analysis of China’s engagement in its western neighborhood, Central Asia. Section 2 has offered an overview of a Chinese perspective on why the Central Asian region is important for Beijing’s agenda to safeguard and implement the SREB by discussing a combination of geopolitical and geo-economic factors. It has pointed out that the launch of the SREB has implications on three levels of China’s Central Asia policy formulation: Xijin strategy, China’s diplomacy toward neighboring countries and major powers. By applying this three-level analysis, it further highlighted Kazakhstan’s importance in developing the SREB in Central Asia.

Moreover, Section 3 has demonstrated that Kazakhstan’s value for Beijing lies not only in its material properties but in its active support of the SREB through a set of concrete steps. By presenting a thorough account on how the SREB is being enacted in Kazakhstan, it argues that Astana exercises a considerable agency in shaping the contours of the SREB development on the ground by setting its own priorities and putting forwards its own agenda. Although one cannot deny the structural effects of the power asymmetry on China’s interactions with smaller states, there is, however, little evidence in the case of Kazakhstan that China imposes its own vision or unilaterally shapes the negotiation agenda. Moreover, a shared understanding between the two states about the complementarity of mutual interests provides a solid foundation for overall Kazakh-Chinese cooperation. Yet, the strengthening of relations between the two neighbors, especially in the economic domain, has not led to an improvement of Kazakh popular perceptions of China, whose image is further worsened by the ongoing securitization of ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, including Kazakhs.

Finally, the question is: can we define the Kazakh-Chinese cooperation under the SREB plans being a win-win based on mutual benefit? As noted in Section 1, one cannot answer this question with a simple yes or no, and we do not know, with certainty, how the outcomes of the current interactions between Astana and Beijing will play out in the future. So far, the findings of the present study have shown that the Kazakh-Chinese engagement is based on the “mutual gains approach.” Nevertheless, due to the complexity that arises from the diversity of potentially involved actors (the state, business representatives, and local society), it will be more productive to look at concrete examples of joint collaboration in order to assess benefits of all interested parties.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Assel G. Bitabarova

Assel G. Bitabarova is currently a Ph.D. student at Graduate School of Letters of Hokkaido University. Her PhD research focuses on Sino-Central Asian engagement in post-Soviet era based on a comparative analysis of three case studies – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. Her research interests also include China’s foreign and security policies, international relations and politics of Central Asia, and the relations between domestic and international politics.

Notes

1 Cai, Understanding China’s Belt and Road Initiative; Callahan, “China’s ‘Asia Dream’”; and etc.

2 Yeh and Wharton, “Going West and Going Out”; Zhao, “‘Sichou zhi lu jingji dai’”; etc.

3 Guanchazhe, “’Yidai Yilu’ Zhongyu You le Guanfang Yingyi.”

4 Rolland, China’s Eurasian Century?.

5 Bartosiewicz and Szterlik, “Łódź’s benefits”; Zhou and Esteban, “Beyond Balancing”; etc.

6 See, for instance, Chajdas, “BRI Initiative”.

7 Pantucci and Lain, “China’s Eurasian Pivot,” 2.

8 Laruelle, “Introduction,” x.

9 Clarke, “Beijing’s March West”; Pantucci and Lain, “China’s Eurasian Pivot”; etc.

10 Bizhanova, “Can the Silk Road Revive Agriculture?”

11 Reeves, “China’s Silk Road Economic Belt Initiative.”

12 Gerring, Case Study Research, 42.

13 George and Bennett, Case Studies and Theory Development, 19.

14 Wang, “Xijin, Zhongguo diyuan zhanlue de zaipingheng.”

15 The word “Kazakh” is used as the state-centric meaning rather than ethnic-based definition.

16 Kassenova, “China’s Silk Road and Kazakhstan’s Bright Path.”

17 According to Chinese official statistics, in 2016 China’s total international trade amounted to USD 3.7 trillion, while its trade with Central Asian countries was valued at about USD 30 billion, i.e. it constituted only 0.9% of the total value of Chinese exports and imports. See Zhongguo Tongji Nianjian 2017.

18 Indeed, most studies have highlighted that the Xinjiang factor has been a key component of China’s Central Asia policy from the very beginning. See, for instance, Clarke, Xinjiang and China’s rise in Central Asia; and Tukmadiyeva, “Xinjiang China’s Foreign Policy”, etc.

19 Wu and Guo, Xinjiang Gaige Kaifang 30 Nian Tonglan, 152.

20 In 2015, Xinjiang’s trade with the five Central Asian states reached nearly USD 11 billion, which accounted for over half (56%) of its total trade volume of the same year (USD 19.7 billion). See Xinjiang Tongji Nianjian 2016.

21 The SCO is a regional organization founded by China, Russia and four Central Asian states – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan – in 2001.

22 Yuan, “China’s Role in Establishing and Building.”

23 Interviews with Chinese experts in Beijing and Shanghai in September 2013 as well as in Lanzhou and Urumqi in January 2016.

24 See, for instance, Kaczmarski, Russia-China Relations.

25 China’s second international gas pipeline is Myanmar-China gas pipeline that began operation in July 2013. Its designed capacity is 12 bcm/year. Data obtained from The Institute of Energy and Economics, Japan (https://eneken.ieej.or.jp/).

26 Zhongguo Shiyou Xinwen Zhongxin, “Zhongya Tianranqi Guandao.”

27 Interestingly, Kazakhstan began to import it natural gas in considerable volumes to China in October 2017. See KazTransGas, “Kazakhstan to Start Natural Gas Exports.”

28 Wen Wei Po, “Yidai, Yilu.”

29 For instance, Chinese prominent IR scholar Yan Xuetong thinks that China’s neighborhood has become increasingly important against the backdrop of its rise and that Beijing needs to focus on its periphery diplomacy in a narrower sense – as opposed to the concept of “Great neigbourhood ” (da zhoubian) – in order to avoid the pitfalls of foreign policy overextension. Yan, “Zhengti de ‘zhoubian’.”

30 Boon, “New trends in Chinese Foreign Policy.”

31 Li, “From Look-West to Act-West.”

32 Xijin is mainly used in the academic discourse, whereas the official lexicon employs the term “opening to the west” (xiang xi kaifang). Zhao, ‘“Sichou zhi lu jingjidai”,” 29.

33 Wang, “’Xijin, Zhongguo diyuan zhanlue de zaipingheng”.

34 See note 28.

35 The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). “Xinjiang Touze Jijian Chao 8000 Yi.”

36 National Development and Reform Commission of the PRC. 2015. “Vision and Actions“.

37 See, for instance, Uyanaev, “Initsiativa KNR “Odin Poyas, Odin Put””, 21–22.

38 Zhao, “Qianping Zhong-E-Mei Da San Zhanlue Zai Zhongya de Gongchu”, 103.

39 On Russia’s moves to link-up the EEU with the SREB, see Gabuev, “Crouching Bear, Hidden Dragon,” 68–71.

40 For instance, see Zuenko, “Odin ‘Poyas’, Dva Puti: Vospriyatie Kitaiskih Integratsionnyh Proektov.”

41 For example, of particular relevance is the future trajectory of Sino-Russian relations in the Arctic, as there is a significant divergence in Chinese and Russian attitudes toward the Arctic issue. Specifically, Russia’s stance is important with regard to China’s plan of building a “Polar Silk Road.”

42 Pan, “Sichou Zhi Lu Jingji Dai,” 16.

43 Zhao, ‘“Sichou Zhi Lu Jingjidai,” 31.

44 China and Kazakhstan linked their railway systems via the two major links at the Alashankou/Dostyk and Khorgos/Altynkol crossings in 1990 and 2012, respectively.

45 There is also the northern corridor of the CERF via Russia’s Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR), however, China is increasingly using the middle corridor, with Urumqi functioning as its domestic transport hub, in order tackle regional economic disparities at home. See Hillman, “China-Europe Railways”.

46 Huang, “China-Europe Trains on Track.”

47 Kazcomak, “The Construction of Kazakhstan Section”; China News, “Xi Ou-Zhongguo Xibu Guoji Gonglu Zhongguo Duan Guantong.”

48 Wu and Guo, Xinjiang GaigeKkaifang, 152.

49 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, “Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo He Hasakesitan Gongheguo Zhengfu Guanyu Zhong-Ha Bianjing Kouan Ji Qi Guanli Zhidu de Xieding.”

50 The total trade turnover between Xinjiang and Kazakhstan amounted to USD 5.7 billion. See Xinjiang Tongji Nianjian 2016.

51 Ibid.

52 According to data from the Committee on Statistics of Kazakhstan.

53 Media reports, interviews, briefings of the Kazakhs who experienced detention in re-education centers in Xinjiang in 2017–2018. For their protection, their names shall not be disclosed.

54 Bocharova, “Problema Etnicheskih Kazakhov Ne Shodit s Povestki Dnya Diplomaticheskih Sluzheb.”

55 Xing, “China’s Foreign Policy toward Kazakhstan,” 111.

56 Kyrgyzstan joined the EEU in 2015.

57 Chinese scholars and experts often highlight Kazakhstan’s active engagement in regional political processes. For instance, Ding Xiaoxing, Director of Division for Central Asian Studies at China Institute of Contemporary International Relations, highly evaluated Kazakhstan’s foreign policy for its omnidirectional flexibility. Interview, Peking, September 2013.

58 UN News. “Kazakhstan prizyvaet ‘splotit’sya vokrug idei Bol’shoi Evrazii.’” In academia, the term Greater Eurasia was first used by Michael Emerson in “Towards a Greater Eurasia: Who, Why, What, How? Eurasia Emerging Markets Forum”. Nazarbayev University, National Analytical Center, Astana, 2013.

59 Zhao, “Sichou zhi lu jingji dai”, 32.

60 Official Site of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan. “Zaklyuchitel’noe Slovo Prezidenta Respubliki Kazakhstan Nazarbaeyv N. A. na 25-m Zasedanii Soveta Inostrannyh Investorov.”

61 Ju, ““Sichou Zhi Lu” Hao Guoji Lieche Tongche.”

62 “100 concrete steps to implement five institutional reforms”, “State program of development and integration of transport system infrastructure until 2020”, “The state program of industrial-innovative development of Kazakhstan for 2015–2019”, “Roadmap for business – 2020”, “Employment roadmap – 2020”, etc.

63 For more information see Ministry of National Economy of Kazakhstan, “The State Program of Infrastructural Development.”

64 Tengrinews, “V Slozhivsheisia Situatsii Kitai dlya Kazakhstana Mozhet Stat”.

65 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, “Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo He Hasakesitan Gongheguo Guanyu Quanmian Zhanlue Huoban Guanxi Xin Jieduan de Lianhe Xuanyan.”

66 See Xinhua, “Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo He Hasakesitan Gongheguo Zhengfu Lianhe Gongbao (Quan Wen).”

67 The established bodies of bilateral interactions between the two countries include regular meetings of heads of state, heads of government as well as the Kazakhstan-China cooperation committee with its 11 subcommittees set up in 2004.

68 See “Ramochnoe soglashenie mezhdu Pravitel’stvom Respubliki Kazakhstan i Pravitel’stvom Kitaiskoi Narodnoi Respubliki ob ukreplenii sotrudnichestva v oblasti industrializatsii i investitsii [A framework agreement between the government of the Republic of Kazakhstan and the government of the PRC on strengthening industrial and investment cooperation]”. The text of the agreement can be found at egov.kz portal.

69 Zakon.Kz, “President Kazakhstana Podvel Itogi Svoego Vizita v Kitai.”

70 The EEU-SREB coordination was officially launched in May 2015 at the Russo-Chinese bilateral talks, when Presidents Putin and Xi signed the Russo-Chinese Joint Declaration on the coordination of the construction of the EEU and the SREB. See Gabuev, “Crouching Bear, Hidden Dragon.”

71 In December 2017, the EEU member states have finally presented a list of projects to the Chinese side for co-financing, which consists of 38 transport infrastructure projects that seek to enhance transportation logistics between China and the EU via the territory of the EEU member states. Eurasian Economic Commission, “Transport i Logistika Mogut Stat.” Moreover, the EEU and China signed an agreement on economic and trade cooperation (a lengthy document consisting of 13 chapters) in May 2018, which aims to improve coordination of economic activities and facilitate trade between the parties but does not propose free trade.

72 Kassenova, “China’s Silk Road,” 112.

73 See Burkhanov and Chen, “Kazakh perspective on China.”

74 For a more detailed discussion on the potential of Kazakhstan’s agriculture, see Bizhanova, “Can the Silk Road Revive Agriculture?”.

75 Masanov, “Vyplavim i obuzdaem reki.”

76 See Official Website of the BRI, “Guoji Channeng Hezuo [International Capacity Cooperation].”

77 Kazinform, “Kitai Pereneset Desyatki Predpriyatii Nesyr’evogo Sektora v Kazakhstan.”

78 This question is one of the most asked by Kazakh netizens in their reaction to the news on Kazakh-Chinese industrial cooperation progress.

79 Ministry for Investments and Development of the Republic of Kazakhstan, “2018 Zhyly 6 Qazaqstan-Qytai Investitsiialyq Zhobasyn.”

80 Mazorenko, “Infrastruktura, Syr’e i Metallurgiya.”

81 Masanov, “Kakie Proizvodstva Pereneset KNR v Zhambyl’skuiu Oblast’.”

82 Tengrinews, “Ob utverzhdenii Soglasheniia mezhdu Pravitel’stvo Respubliki Kazakhstan i Pravitel’stvom Kitaiskoi Narodnoi Respubliki.”

83 Tengrinews, “Kitaiskie biznesmeny priznalis’, chto bol’she vsego ih razdrazhaet v Kazakhstane.”

84 BNews Kazakhstan, “Bolee 20 Tys Rabochih Mest Obespechit Zapusk Kazakhstansko-Kitaiskih Proektov.”

Bibliography

- Bartosiewicz, A., and P. Szterlik. “Łódź’s Benefits from the One Belt One Road initiative.” International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications (2018): 1–17 (online version). doi:10.1080/13675567.2018.1526261.

- Bizhanova, M. “Can the Silk Road Revive Agriculture? Kazakhstan’s Challenges in Attaining Economic Diversification.” In China’s Belt and Road Initiative and its Impact in Central Asia, edited by M. Laruelle, 51–66. Washington, DC: The George Washington University, 2018.

- BNews Kazakhstan. 2018. “Bolee 20 Tys Rabochih Mest Obespechit Zapusk Kazakhstansko-Kitaiskih Proektov.” [The Launch of Kazakh-Chinese Projects Provides over 20 Thousand Working Places.] February 27. Accessed June 25, 2018. https://bnews.kz/ru/news/bolee_20_tis_rabochih_mest_obespechit_zapusk_kazahstanskokitaiskih_proektov

- Bocharova, M. 2018. “Problema Etnicheskih Kazakhov Ne Shodit s Povestki Dnya Diplomaticheskih Sluzheb.” [The Problem of Ethnic Kazakhs in China has been on the Agenda of the Foreign Service.] Vlast’, November 28. Accessed June 1, 2018. https://vlast.kz/novosti/25898-problema-etniceskih-kazahov-v-kitae-ne-shodit-s-povestki-dna-diplomaticeskih-sluzb.html

- Boon, H. T., M. Li, and J. Char. “New trends in Chinese Foreign Policy.” Asian Security 13, no. 2 (2017): 81–83. doi:10.1080/14799855.2017.1286158.

- Burkhanov, A., and Y. Chen. “Kazakh Perspective on China, the Chinese, and Chinese Migration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies Review 39, no. 12 (2016): 2129–2148. doi:10.1080/01419870.2016.1139155.

- Cai, P. Understanding China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Sydney: Lowy Institute for International Policy, 2017. Accessed April 2, 2018. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/documents/Understanding%20China’s%20Belt%20and%20Road%20Initiative_WEB_1.pdf.

- Callahan, W. “China’s ‘Asia Dream’: the Belt Road Initiative and the new regional order.” Asian Journal of Comparative Politics 1, no. 3 (2016): 226–243. doi:10.1177/2057891116647806.

- Chajdas, T. “BRI Initiative: a New Model of Development Aid?” In The Belt and Road Initiative: Law, Economics and Politics, edited by J. Chaisse and J. Górski, 416–453. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2018.

- China News. 2017. “Xi Ou-Zhongguo Xibu Guoji Gonglu Zhongguo Duan Guantong.” [The Chinese Section of the WEWC International Highway is Linked Up.] November 18. Accessed May 25, 2018. http://www.chinanews.com/gj/2017/11-18/8380089.shtml

- Chu, D. “Gas Imports from Central Asia Set to Rise.” Global Times, January 17. Accessed April 5, 2018. http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1085093.shtml

- Clarke, M. “Beijing’s March West: Opportunities and Challenges for China’s Eurasian Pivot.” Orbis 60, no. 2 (2016): 296–313. doi:10.1016/j.orbis.2016.01.001.

- Clarke, M. E. Xinjiang and China’s Rise in Central Asia – A History. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Tengrinews. 2016. “Ob Utverzhdenii Soglasheniia Mezhdu Pravitel’stvo Respubliki Kazakhstan i Pravitel’stvom Kitaiskoi Narodnoi Respubliki o Poryadke Oformleniia Viz s Delovymi Tselyami v Ramkah Sotrudnichestva v Oblasti Industrializatsii i Investitsii.” [On Ratification of the Agreement between the Republic of Kazakhstan and People’s Republic of China Concerning the Procedures for the Business Visa Application within the Framework of Industrial and Investment Cooperation.] April 7. Accessed December 10, 2018. https://tengrinews.kz/zakon/pravitelstvo_respubliki_kazahstan_premer_ministr_rk/mejdunapodnyie_otnosheniya_respubliki_kazahstan/id-P1600000193/

- Eurasian Economic Commission. 2017. “Transport i Logistika Mogut Stat’ Draiverami Ekonomicheskogo Rosta v EAES.” [Transport and Logistics May Become Drivers of Economic Growth in the EEU.] December 8. Accessed May 25, 2018. http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/nae/news/Pages/8-12-2017-2.aspx

- Gabuev, A. “Crouching Bear, Hidden Dragon: ‘One Belt One Road’ and Chinese-Russian Jostling for Power in Central Asia.” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 5, no. 2 (2016): 61–78. doi:10.1080/24761028.2016.11869097.

- George, A. L., and A. Bennett. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004.

- Gerring, J. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Guanchazhe. 2015. “‘Yidai Yilu’ Zhongyu You le Guanfang Yingyi: Jiancheng B&R.” [One Belt, One Road has Finally had its Official English Translation: Hereinafter called B&R.] September 24. Accessed March 18, 2018. https://www.guancha.cn/politics/2015_09_24_335434.shtml

- Hillman, J. “The Rise of the China-Europe Railways”. Accessed May 25, 2018. https://www.csis.org/analysis/rise-china-europe-railways

- Huang, G. 2017. “China-Europe Trains on Track”. Global Times, April 23. Accessed May 5, 2018. http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1043740.shtml

- Ju, M. 1992. ““Sichou Zhi Lu” Hao Guoji Lieche Tongche.” [International Train ‘Silk Road’ to Open to Traffic.] Renmin Ribao, June 22.

- Kaczmarski, M. Russia-China Relations in the Post-Crisis International Order. London: Routledge, 2015.

- Kassenova, N. “China’s Silk Road and Kazakhstan’s Bright Path: Linking Dreams of Prosperity.” Asia Policy 24 (2017): 110–116. doi:10.1353/asp.2017.0028.

- Kazcomak. 2017. “The Construction of Kazakhstan Section of the Road WE-WC was Completed.” December 21. Accessed May 25, 2018. https://www.kazcomak.kz/en/press-centre/news/186-the-construction-of-kazakhstan-section-of-the-road-western-europe-western-china-was-completed

- Kazinform. 2014. “Kitai Pereneset Desyatki Predpriyatii Nesyr’evogo Sektora v Kazakhstan.” [China Transfers Dozens of Companies in Non-raw Material Sector to Kazakhstan.] December 17. Accessed May 25, 2018. https://www.inform.kz/rus/article/2732890

- KazTransGas. 2017. “Kazakhstan to Start Natural Gas Exports to China on 15 October.” Accessed April 5, 2018. http://www.kaztransgas.kz/index.php/en/press-center/press-releases/1297-kazakhstan-to-start-natural-gas-exports-to-china-on-15-october

- Laruelle, M. “Introduction. China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Quo Vadis?” In China’s Belt and Road Initiative and its Impact in Central Asia, edited by M. Laruelle, x–xii. Washington, DC: The George Washington University, 2018.

- Li, M. “From Look-West to Act-West: Xinjiang’s role in China-Central Asian relations.” Journal of Contemporary China 25, no. 100 (2016): 515–528. doi:10.1080/10670564.2015.1132753.

- Masanov, Y. 2017. “Kakie Proizvodstva Pereneset KNR v Zhambyl’skuiu Oblast’: Fosfor, Gaz i Ammiak.” [What Kind of Production PRC relocates to the Zhambyl Region: Phosphorus, Gas and Ammonia.] Today. Kz, June 12. Accessed June 25, 2018. http://today.kz/news/ekonomika/2017-06-12/744196-kakie-proizvodstva-knr-pereneset-v-zhambyilskuyu-oblast-fosfor-gaz-i-ammiak/

- Masanov, Y. 2017. “Vyplavim i obuzdaem reki – predpriyatiya s kitaiskimi investitsiyami v VKO.” [Will Smelt and Control Rivers – Ventures with Chinese Investments in the Eastern Kazakhstan Region.] Today.Kz, May 19. Accessed June 25, 2018. http://today.kz/news/ekonomika/2017-05-19/742506-vyiplavim-med-i-obuzdaem-reki—predpriyatiya-s-kitajskimi-investitsiyami-v-vko/