ABSTRACT

Since 2017, China has actively proposed a number of joint development schemes in the South China Sea (SCS), namely with the Philippines and Vietnam. Both economic and strategic incentives lie behind China’s development of these schemes. China’s economic incentives include its domestic demand for energy, “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” construction, Hainan the pilot free trade zone construction, construction of a common market and the future economic integration among the SCS coastal States. China’s strategic incentives include achieving its goal of becoming a leading maritime power, playing its constructive role in maintaining a peaceful and stable SCS, developing good relations with other coastal States, and reducing the intensity of China-U.S. competition in the SCS. China’s policy choices on the SCS joint development are as follows: first, to promote good faith in the SCS; second, to limit unilateral activities in disputed areas; third, to focus on less sensitive areas of the SCS; fourth, to reach joint development arrangements by establishing relevant working mechanism; fifth, to begin the process in areas where there are only two claimants; sixth, to define sea areas for the joint development by seeking consensus; seventh, to discuss the feasibility of setting up a Spratly Resource Management Authority (SRMA) with supranational character.

1. Introduction

Joint development in the South China Sea (SCS) has been suggested as a solution to the Spratly Islands disputes since the 1980s. China was one of the earliest proponents of “pursuing joint development while shelving disputes”. Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping made his proposal for solving disputes over Nansha (Spratly) Islands in June 1986 and April 1988 meetings with Philippines leaders.Footnote1

Chinese government has actively discussed with other coastal States over the joint development of the SCS since 2017. China and Vietnam agreed to conduct follow-up works of the joint inspection in waters outside the Beibu (Tonkin) Gulf as addressed in the joint statement in November 2017.Footnote2 China and the Philippines signed Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation on Oil and Gas Development in November 2018.Footnote3

Two conditions are necessary before there can be serious discussions on joint development arrangements.Footnote4 First, joint development arrangements tend to be concluded in periods where good relations existed amongst the relevant parties. China and other coastal States in the SCS have taken steps to build confidence and trust among the claimants. New progresses in the SCS such as the ASEAN-China Single Draft Negotiating Text of the Code of Conduct (COC) are conducive to creating benign bilateral relations, which serves as a prerequisite to joint development. If the benign relations can be established between China and other coastal States in the SCS, the first condition for joint development will be basically met. Second, the parties must have the political will to make decisions that may face opposition within their countries. China and other coastal States in the SCS are taking steps to reinforce the underlying rationale for joint development and are articulating the advantages of pursuing this option to the public, indicating the second condition for joint development is in a consensus process.

Joint development may be defined as an inter-governmental arrangement of a provisional nature between two or more countries, designed for functional purposes of joint exploration for and/or exploitation of onshore or offshore hydrocarbon resources. It is especially crucial in areas with overlapping or disputed claims or in areas where countries have not achieved agreement on delimitation.Footnote5

2. China’s economic and strategic incentives

Both economic and strategic incentives exist behind China’s development of these schemes. China’s economic incentives include its domestic demand for energy, “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” construction, Hainan the pilot free trade zone construction, construction of a common market and the future economic integration among the SCS coastal States. China’s strategic incentives include achieving its goal of becoming a leading maritime power, playing its constructive role in maintaining a peaceful and stable SCS, developing good relations with other coastal States, and reducing the intensity of China-U.S. competition in the SCS.

2.1. China’s economic incentives

The increasing demand for energy that China and other SCS coastal States are facing can be viewed as the most important economic incentive for them to jointly exploit oil and gas resources. China is the world’s second-largest oil consumer. China’s oil demand will grow at an annual rate of 2.7% until 2020 and is estimated to reach a ceiling of 690 million tonnes a year by 2030.Footnote6 China becomes the world’s largest natural gas importer by 2019 and with 171 billion cubic meters (bcm) of imports by 2023.Footnote7 China’s natural gas consumption will rise to 620 bcm in 2030.Footnote8 Oil remains the largest source of energy in Southeast Asia and oil consumption grows by 40% over the period from 2016 to 2040, Oil demand expands from 4.7 million barrels per day (mb/d) in 2016 to around 6.6 mb/d in 2040.Footnote9 Natural gas consumption in Southeast Asia also increases strongly, by 60% from 2016 to 2040, mainly due to its increased use in industry and power generation.Footnote10 The presumed large offshore oil and gas reserves in the SCS had sometimes been labeled as the “new Persian Gulf” (see ). China Geological Survey of Ministry of land and Resources assumed that in China’s dotted line of the SCS deposits at least between 23 and 30 billion tonnes (between 169 and 220 billion barrels) of oil reserves and 20 trillion cubic meter (706 trillion cubic feet) of gas reserves, which is up to one third of China’s total oil and gas reserves.Footnote11

Figure 1. Illustration map of oil and gas-bearing basin in the SCS.

Source: The drawing of this map referenced the following sources: Wang, Ocean Geography of China, 415; China Geological Survey of Ministry of Land and Resources, Marine Geological Work Memorabilia of P.R. China (1949–1999), 26; Li, World Atlas of Oil and Gas Basins, 47.

Building “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” is another important economic incentive for China to initiate joint development in the SCS. The SCS has been an important hub of the Maritime Silk Road since ancient times and plays a significant role in boosting the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” cooperation. There are three sea routes planned for “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” initiative, including China-Indian Ocean-Africa-Mediterranean Sea Blue Economic Passage, China-Oceania-South Pacific Blue Economic Passage, and blue economic passage leading to Europe via the Arctic Ocean.Footnote12 For the first sea route, the SCS is a channel linking the Indian Ocean; for the second sea route, the SCS is a channel linking the Pacific Ocean. Thus, the SCS is a key sea area for “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” construction.

Hainan pilot free trade zone construction can be viewed as a domestic economic incentive for China to initiate joint development in the SCS. The land area of Hainan is 35,400 square km; the permanent resident population of Hainan is 9.1 million by the end of 2015. Chinese government decided to build the whole island of Hainan into a pilot free trade zone in April 2018. In April 2018, Chinese President Xi Jinping urged Hainan to explore and promote the establishment of a free trade port. Xi also said, “The pilot free trade zone will implement high-level trade and investment liberalization and facilitation policies, and overseas businesses there will receive pre-establishment national treatment with a negative list management system.”Footnote13 It could be foreseen that Hainan will implement a more proactive opening-up strategy, leading to the benefits of Hainan’s opening-up radiating to other coastal States in the SCS. In the process of the pilot free trade zone construction, Hainan could become a service guarantee base for resources joint development in the SCS.

Construction of a common market and the economic integration is a future economic incentive for China to initiate joint development in the SCS. As for the SCS coastal States, they all strive to reduce trade tariffs and remove discriminatory practices. In the process of reaching consensus on establishing a Common Market and realizing economic integration, establishing a Common Market for oil and gas can be a first step for the SCS coastal States. Cooperation in the field of oil and gas resource will generate spillover effect, and the cooperation among the six coastal States will set a good example for the ASEAN 10 + 1 and ASEAN 10 + 3 cooperation. Conforming to the regional integration goal advocated by the ASEAN, the path of economic integration is conducive to China’s Hainan the pilot free trade zone construction and“21st Century Maritime Silk Road” initiative.

2.2. China’s strategic incentives

China’s first strategic incentive is achieving its goal of becoming a leading maritime power. As a major maritime as well as land country, China maintains its sustainable development with immense space and abundant resources provided by the seas and oceans. In November 2012, former Chinese President Hu Jintao declared that “building China into a maritime power.”Footnote14 In October 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping declared that “stepping up efforts to build China into a strong maritime country.”Footnote15 Modern marine economy is an important support for becoming a leading maritime power. China’s gross oceanic product exceed 8.34 trillion RMB (about 1.26 trillion U.S. dollars) in 2018, the gross product value generated by China’s marine industry accounted for 9.3% of the country’s GDP that very year.Footnote16 The joint development and marine industry cooperation in the SCS will be conducive to achieving China’s goal of becoming a leading maritime power.

China’s second strategic incentive is playing its constructive role in maintaining a peaceful and stable SCS. Turning the SCS into the sea of peace is a shared vision of the SCS coastal States, including China. The SCS dispute has been regarded as one of China’s external factors that hinder the pursuit of China’s two centenary goals. China’s two centenary goals are as follows: finishing the building of a moderately prosperous society as China’s first centenary goal by 2020; from 2020 to the middle of this century, to embark on a new journey toward the second centenary goal of fully building a modern country.Footnote17 In the near future, China’s core task of internal and foreign affairs is the above-mentioned two centenary goals. A peaceful and stable SCS fits the interests of all the coastal States, including China.

China’s third strategic incentive is developing good relations with other coastal States. The South China Sea (SCS) dispute in the period of 2009–2016 has affected China-ASEAN relations. When a verdict was given on the SCS arbitration in July 2016, tensions in the SCS reached an apex. The ASEAN claimants believed that China had become increasingly assertive regarding the SCS issues over the past few years.Footnote18 To balance China’s increasing influence in the SCS, the ASEAN claimants propelled the internationalization of the SCS disputes and became more reliant on the United States and other external States to deal with their security concerns. Considering the ASEAN States as its important neighbors, China hopes to deepen relations with its ASEAN neighbors in accordance with the principle of amity, sincerity, mutual benefit, and inclusiveness. That’s why China has initiated joint development proposals with other coastal States since 2017. China also intends to use joint development arrangement to reduce the SCS tension and to improve good relations with the ASEAN claimants.

China’s fourth strategic incentive is reducing the intensity of China-U.S. competition in the SCS. China-U.S. competition in the SCS includes island building, military deployment, and freedom of navigation. From China’s perspective, U.S. Navy warships deliberately entered China claimed waters and conducted close-in reconnaissance activities against China in the SCS, which may cause for security hazards and potential incidents in the air and at sea between China and the U.S.Footnote19misjudgment From U.S.’s view, China’s island-building activities are “unilaterally” altering the status quo of the SCS. If conflicts between China and the U.S. erupt in the SCS, the situation will rapidly deteriorated and become uncontrollable. China-U.S. needs to build a new military communication mechanism to manage potential crisis, to avoid military, and to minimize the risk of confrontation. In the perspective of the U.S., whether it chooses to support the SCS joint development is determined by two factors: the appropriate place for the U.S. considered by the joint development arrangement, and the restriction of China’s power imposed by the mechanism of joint development. If China can accommodate the two concerns of the U.S., the U.S. has no reason to object to the joint development in the SCS.

3. China’s policy choices on the SCS joint development

China’s Policy choices on the SCS joint development are as follows: first, to promote good faith in the SCS; second, to limit unilateral activities in disputed areas; third, to focus on less-sensitive areas of the SCS; fourth, to reach joint development arrangements by establishing relevant working mechanism; fifth, to begin the process in areas where there are only two claimants; sixth, to define sea areas for the joint development by seeking consensus; seventh, to discuss the feasibility of setting up a SRMA with supranational character. The above-mentioned seven policy choices can be classified into three types: clear government policies (No. 1, 2, 3, 4), implicit government policies (No. 5, 6), and a possible policy choice (No. 7) (see )

Table 1. Three types of China’s policy choices on the SCS joint development.

3.1. To promote good faith in the SCS

The obligation of good faith in the context of the SCS means that claimants are willing to negotiate maritime boundaries or joint development zones with an open mind. The acts of a lack of good faith would include, for example, drilling in the seabed for oil and gas and arresting vessels of the other State fishing in the area concerned. Less intrusive activities, such as seismic testing and other forms of marine scientific research, may be permissible, but may require the State conducting or authorizing the testing or research to share the information obtained thereby at some stage with the other State.Footnote20

China has been devoted to promote good faith in the SCS in recent years. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi proposed to establish a South China Sea littoral states cooperation mechanism in March 2016.Footnote21 Hainan Province proposed to establish a Pan-South China Sea Tourism Economic Cooperation Rim by 2020, which will be focused on starting new international services and opening new cruise lines.Footnote22 China has reaffirmed with the Philippines that it will address territorial and jurisdictional disputes by peaceful means, increasing mutual trust and confidence and to exercise self-restraint.Footnote23 Chinese high-level diplomats have also demonstrated goodwill to the ASEAN claimants in recent years. For example, Cui Tiankai, Chinese Ambassador to the U.S., said China is not trying to take back the islands and reefs that are illegally occupied by others.Footnote24 Chinese mainstream media have played close attention to the conception of “pursuing joint development while shelving disputes” since 2017. Chinese government has made great efforts to manage domestic politics and tone down nationalistic rhetoric associated with the SCS dispute. Chinese government has also educated the public on the benefits and importance of joint development and emphasizes the fact that it does not involve a surrender of sovereignty.

China still has plenty more work to promote good faith in the near future. For example, China should make the other claimant States believe that China’s joint development proposal is also in their interest. China needs to provide more public goods such as navigation safety, environment protection, maritime salvage and weather forecast. For example, China can open the Mischief Reef for emergency relief. China should try to negotiate fair and equal JDAs with the ASEAN claimants in the future, which will contribute to a long-standing public support on joint development among the SCS coastal States. China needs to positively negotiate with ASEAN on the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea in the near future. China also needs to accommodate the interest of the relevant maritime powers in the institution designing process.

3.2. To limit unilateral activities in disputed areas

The unilateral development in the disputed areas does not meet the “spirit of understanding and cooperation” initiated by the UNCLOS. Exploration and exploitation in the disputed waters is politically sensitive, lawfully uncertain, technically challenging and financially risky. If one party conducts unilateral exploitation in waters that have overlapping claims of maritime rights and interests between two parties, the other party will certainly take corresponding actions, which will complicate the maritime situation, and even escalate the tension, leading to no exploitation by either party.Footnote25 In short, the unilateral activities in disputed area will make obstacles for the negotiations of JDA in the future.

China is the only one state that owns technology and capital for deep-water drilling among the SCS coastal States. In May 2012, China National Offshore Oil Corporation launched a massive deep-water drilling rig, the RMB 6 billion Haiyang Shiyou 981 (HYSY 981). The increasing economic appetite of Chinese oil companies pushes the Chinese government to respond by undertaking unilateral exploration and development. Some analysts in China have called for unilateral measures to pressure uncooperative parties.Footnote26

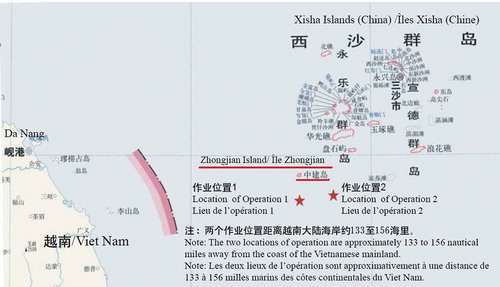

The China-Vietnam oil rig standoff is a case to observe the two countries responses of drilling rig in the area near the Paracel Islands. The HYSY 981 drilling rig in May–July 2014 caused the China-Vietnam oil rig standoff. From China’s perspective, the two locations of operation are 17 nautical miles from both the Zhongjian Island of Xisha Islands and the baseline of the territorial waters of Xisha Islands; yet approximately 133 to 156 nautical miles away from the coast of the Vietnamese mainland (see ).Footnote27 From Vietnam’s perspective, the HYSY 981 was situated 120 nautical miles east of Vietnam’s Ly Son Island and 180 nautical miles south of Hainan.Footnote28 Chinese government claimed that the HYSY 981 drilling location being inside the contiguous zone of China’s Xisha Islands,Footnote29 while Vietnamese government claimed that the drilling location being inside Vietnam’s Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf. In July 2014, China claimed the rig had completed its mission and decided to relocate it in the sea area near Hainan Island. But some scholars argued that Vietnam’s persistence and risk acceptance appear to have convinced China to withdraw the oil rig early.Footnote30

Figure 2. Map of the operation locations of the HYSY 981.

Source: Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “The Operation of the HYSY 981 Drilling Rig: Vietnam’s Provocation and China’s Position,” Accessed August 31 2019. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1163264.shtml.

After the HYSY 981 standoff in 2014, China has refrained its oil companies from unilateral exploration or development. The HYSY 981 has returned to northwestern portion of the SCS several times since June 2015. However, on none of these occasions did it cross over to the Vietnamese side of the assumed median line between the two countries (excluding the Paracel Islands).Footnote31 For example, in June 2015, HYSY 981 was again deployed to an area of the Paracel Islands, the coordinate of 17°03′45″N/109°59′03″E, 139 km south of Hainan Island.Footnote32 Vietnam claimed that the rig location is located in an overlapping sea area, but it is on the Chinese side of the assumed median line between the two coasts, so Hanoi largely remained mute this time.Footnote33

China also urges Vietnam to stop its unilateral actions. In July 2017 and March 2018, the Vietnamese government twice suspended Repsol’s drilling in the area adjacent to Block 136/03 following pressure from China.Footnote34 Block 136 is near Vanguard Bank which is both claimed by China and Vietnam.

To manage and control the differences concerning maritime issues, China and Vietnam agreed to refrain from taking actions that will make the situation complicated and the disputes enlarged.Footnote35 China and the Philippines have agreed that the two States will restrain their unilateral development in the overlapping area.Footnote36

Considering the significant legal and political risks created by unilateral development in the disputed areas, the six coastal States have the obligation to restrain each oil companies’ unilateral actions in disputed areas. States are under an obligation not to take any unilateral actions which would permanently alter the situation in disputed areas. This includes unilateral drilling and the unilateral exploitation of resources.Footnote37 Joint development arrangements are the only way that the claimants can acquire legitimate access to resources in certain areas of the SCS.

3.3. To focus on less sensitive areas of the South China Sea

Since not all countries are ready to co-develop oil and gas resources in their EEZs, claimants could consider cooperating in less sensitive areas of the SCS as starters. To create an atmosphere conducive to joint development in the SCS, Chinese government has proactively initiated less sensitive areas cooperation with other coastal States in the SCS since 2011.

In October 2011, China and Vietnam signed a principle agreement aimed at solving maritime Issues. Both sides will positively promote less sensitive maritime cooperation, such as marine environmental protection, scientific research, search and rescue, disaster reduction and prevention, the principle agreement said.Footnote38 Chinese government has established the Experts’ Working Group for Maritime Cooperation in Less Sensitive Areas with Vietnam government. From May 2012 to December 2018, the Experts’ Working Group for Maritime Cooperation had held 12 rounds of consultation.Footnote39 In October 2013, China and Vietnam signed research on cooperation in the management of marine environment in Beibu Gulf and the environment of its islands, which had achieved positive outcomes. China and Vietnam have conducted joint search and rescue exercises in the areas of Beibu (Tonkin) Gulf, the two countries are positively taking measures to promote the signing of a China-Vietnam maritime search and rescue cooperation agreement.Footnote40

China and the Philippines have convened Bilateral Consultation Mechanism on the South China Sea (BCM). Part of the BCM was discussed is less sensitive areas cooperation. The First Meeting of the China-Philippines BCM was held in Guiyang, Guizhou Province, China on May 19 2017. In the Fourth BCM in April 2019, China and the Philippines exchanged views on ways to enhance maritime cooperation in areas such as maritime search and rescue, maritime safety, marine environmental protection/marine scientific research, and fisheries in relevant Working Group meetings under the framework of the BCM.Footnote41

3.4. To reach joint development arrangements by establishing relevant working mechanism

According to the Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation on Oil and Gas Development between China and the Philippines signed in Manila on November 20 2018, the two governments have decided to negotiate on an accelerated basis arrangements to facilitate oil and gas exploration and exploitation in relevant maritime areas.Footnote42 The two governments also agreed to establish relevant working mechanism, such as a Committee and one or more Working Group.Footnote43

The two governments will establish an Inter-Governmental Joint Steering Committee (“Committee”) and one or more Inter-Entrepreneurial Working Group (“Working Group”). The Committee will be co-chaired by the Foreign Ministries, and co-vice chaired by the Energy Ministries, with the participation of relevant agencies of the two governments, and will comprise an equal number of members nominated by the two governments. Each Working Group will consist of representatives from enterprises authorized by the two governments.Footnote44

The Committee will be responsible for negotiating and agreeing the cooperation arrangements and the maritime areas to which they will apply (“cooperation area”), and deciding the number of Working Groups to be established and for which part of the cooperation area each Working Group is established (“working area”). Each Working Group will negotiate and agree on inter-entrepreneurial technical and commercial arrangements that will apply in the relevant working area.Footnote45

China authorizes China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) as the Chinese enterprise for each Working Group. The Philippines will authorize the enterprise(s) that has/have entered into a service contract with the Philippines with respect to the applicable working area or, if there is no such enterprise for a particular working area, the Philippine National Oil Company – Exploration Corporation (PNOC-EC), as the Philippine enterprise(s) for the relevant Working Group.Footnote46

In August 2019, the two governments have announced the establishment of Inter-Governmental Joint Steering Committee and Inter-Entrepreneurial Working Group.Footnote47

The Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation on Oil and Gas Development between China and the Philippines is the first joint development MoU that is released of full text. CNOOC and Petrovietnam once signed and implemented a framework agreement on oil and gas cooperation in the agreed offshore area of the Beibu (Tonkin) Gulf on October 31 2005.Footnote48 It should be noted that China and Vietnam have signed an Agreement on the Delimitation of the Territorial Seas, Exclusive Economic Zones and Continental Shelves in the Beibu Gulf (Gulf of Tonkin) on December 25 2000, which was entered into force on June 30 2004.Footnote49 China and DPRK once signed an Agreement on the Joint Exploitation of Offshore Oil between the two governments on December 24 2005, aiming to jointly exploit oil in their adjacent maritime areas,Footnote50 which is considered to be the first time for China to substantially cooperate with an adjacent country to exploit oil and gas in disputed area.Footnote51 The above-mentioned CNOOC-Petrovietnam framework agreement and China-DPRK Agreement on the Joint Exploitation of Offshore Oil have not been released of full text yet.

Looking from Chinese government open statements and released MoU, there are two legal issues on joint development arrangements which Chinese government has insisted. First, joint development and cooperation between China and the state concerned shall be conducted in accordance with the respective national laws and regulations of both countries and international law, including the 1982 UNCLOS, and without prejudice to the respective positions of the two countries on sovereignty rights and jurisdiction.Footnote52 Second, joint development is a provisional arrangement that conflicting states establish prior to the final settlement of maritime disputes, without prejudice to the final delimitation.Footnote53

3.5. To begin the process in areas where there are only two claimants

In general, it is more likely for the parties to reach JDA on the overlapping claim areas which are claimed by two states. There are some areas involving only two claim states in the SCS, such as certain waters in the northwest of the SCS only claimed by China and Vietnam. China and Vietnam have reached consensus on joint development in the area off the mouth of the Beibu (Tonkin) Gulf. In the future, China and Vietnam can negotiate the possibility of jointly developing the Wan’an Tan (Vanguard Bank). Only China and the Philippines claim the certain waters in the east of Liyue Tan (Reed Bank), so the two states can negotiate and reach a fair JDA. The Philippines in March 2018 identified two areas in the SCS where joint exploration for oil and gas may be undertaken with China, including one in territory that both sides have argued over for years.Footnote54 The 880,000 ha (8,823.5 sq km) SC-72 at the Reed Bank is the one claimed by China and the Philippines.

In order to reduce the difficulty in the oil and gas development in the SCS, the following technical aspects should be paid attention to: First, to initiate from the less sensitive areas, and develop gradually. The less sensitive areas include marine environmental protection, marine scientific research, the detection of oil and gas reserve, the prevention and treatment of oil pollution, etc. Second, in order to weaken the influence of geography and sovereignty in the share of different states, funds, technology and the location of a factory should be added more into the negotiation, which will be beneficial for the government to report the concerning issues to its citizens and thus gain their support. Third, in order to lower the difficulty of the negotiation, the agreement of the joint development should set a transitional period of 5–10 years to reduce the obstacles.

3.6. To define sea areas for the joint development by seeking consensus

One of the major difficulties of reaching JADs is the lack of clarity on the overlapping claim area. The SCS coastal States, including Brunei, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, and the Philippines, lay overlapping claims in the South China Sea (see ). Indonesia insists it being a non-claimant state in the South China Sea and refuses to recognize any existing maritime delimitation dispute with China. But China insists that Indonesia’s EEZ and Continental Shelf off the coast of Natuna overlapped China’s “nine-dash line”. So this article argues that Indonesia is a coastal State in the South China Sea. All the SCS coastal States have made claims to a territorial sea, EEZ and continental shelf from their mainland. But at present, there is a significant lack of clarity on the basis, nature, and extent of the maritime claims in the Spratly Islands area. It is not clear what maritime zones, if any, are being claimed from the Spratly features by the various claimants. The ASEAN claimants, at least for now, appear to be treating the Spratly features as either “rocks” entitled only to a 12 nm territorial sea or low-tide elevations that are not entitled to any maritime zone, but they have not expressly stated this.Footnote55

Figure 3. Illustration map of the claims of SCS coastal States.

Source: Qi, “China’s Presence and Challenges in the South China Sea in Recent Years and China’s SCS Policies in the Future,” 9; Permanent Mission of China to the UN, Note Verbale CML/18/2009; Damrosch & Oxman, “Agora: The South China Sea, Editors’ Introduction”, 96; U.S. Department of State, Spratly Islands in the South China Sea; United Nations Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, Brunei Darussalam’s Preliminary Submission concerning the Outer Limits of its Continental Shelf.

The main concern of the ASEAN claimants is on the coordinates and legal basis of China’s dotted line (nine-dash line). The other claimants feared that joint development before agreeing on the disputed areas would amount to legitimizing China’s nine-dash line.Footnote56 Chinese government stated in July 2016 that China has territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea, including, inter alia:

China has sovereignty over Nanhai Zhudao, consisting of Dongsha Qundao, Xisha Qundao, Zhongsha Qundao and Nansha Qundao; China has internal waters, territorial sea and contiguous zone, based on Nanhai Zhudao; China has exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, based on Nanhai Zhudao; China has historic rights in the South China Sea.Footnote57

But Chinese government still keeps ambiguity by clarifying neither the coordinates nor legal basis of that line. The reasons for this are as follows: one is China want to keep friendly relations with the ASEAN claimants. If China clarifies the coordinates of its nine-dashed line, the Chinese public will accordingly demand their government to take back the islands and reefs that are occupied by others. If Chinese government takes military action in the disputed Spratly Islands, a destruction of relations between China and the ASEAN claimants will be generated. The other is China has no intention to change the freedom of navigation. If China announces its territorial sea baselines of the Spratly Islands, a disruptive influence on the freedom of navigation in the SCS will thus emerge. Based on the above-mentioned two reasons, it’s not realistic to expect Chinese government to clarify its dotted line claims in the SCS in the near future.

Although it is difficult for China to publicly clarify its dotted line, it can clarify claims close-door in some areas where there are only two claimant States. For example, area off the Mouth of Beibu (Tokin) Gulf, area near Wan’an Tan (Vanguard Bank), area of Liyue Tan (Reed Bank). China and Vietnam could define overlapping claims in the area outside the mouth of the Gulf of Tonkin by following customary international law and UNCLOS principles during closed-door consultations. In exchange, Vietnam might refrain from trying to open talks on the Paracel Islands.Footnote58

In principle, it is axiomatic that clearly defined areas of overlapping claims significantly contribute to the conclusion of joint development arrangements. But in reality, especially in the Spratly Islands area, it is very hard to define the overlapping areas.

In the future, the six coastal States in the SCS could define their maritime claims and decide the joint development zones through consensus seeking approach. Considering the exploration and exploitation of hydrocarbon resources in offshore areas being a capital intensive venture predicated on the funding and technical expertise of oil companies, a successful joint development should ensure political, legal and fiscal certainty over a disputed area claimed by two or more States. Deciding the joint development zones by consensus seeking approach among the six coastal States in the SCS can make up for the uncertainty of “provisional arrangement of a practical nature” in the context of Article 74 and 83 of UNCLOS, which will be conducive to guarantee the massive commercial investments of oil companies.

3.7. To discuss the feasibility of setting up a Spratly Resource Management Authority (SRMA) with supranational character

The proposed Spratly Resource Management Authority (SRMA) will be an institute of joint resource development administration with supranational character. The SRMA is referred to a proposal of “Spratly Management Authority”, which was firstly initiated by Mark J. Valencia and his colleagues in 1991.Footnote59 The member states of the SRMA are going to include six coastal States in the Spratly Islands area: Brunei, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, and the Philippines. The SRMA would be empowered to take the following actions: designing plans for the exploration of oil and gas resources in the Spratly Islands area independently; deciding the distribution quota of the oil and gas resource development in the Spratly Islands area for member states; establishing a unified technical standard for member states’ energy trade; levying taxes, collecting loans and granting funds for the oil and gas development; imposing penalty upon those enterprises which evade the obligations. The SRMA will mainly manage the resources in the Nansha Qundao (Spratly Islands) sea which claimed by three or more claimants.

The author designed the organizational structure of the SRMA (see ) by drawing from Valencia’s book.Footnote60 The SRMA can be composed of a Council of Ministers, a Secretary-General, a Secretariat and six sub-committees. The Council would be the decision-making body which was consisted of six representatives of the six coastal States in the Spratly Islands area. The role of the Council was to harmonize the activities of the Secretariat and the general joint development policy of the governments. The Council’s approval was required for important decisions taken by the Secretariat and the Secretary-General. Apart from the coastal States, the other five member States of the ASEAN (Burma, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Singapore), each State can also dispatch a representative to attend the Council. The five non-claimants of ASEAN states can voice their opinions on the related issues, but they have no right to vote. The relevant maritime powers, such as Australia, the European Union, India, Japan, South Korea, and the United States, might be considered as interested observers. The relevant maritime powers could make their views known through diplomatic channels outside the SRMA. The ASEAN and the UN might also be considered as interested observers. The SRMA needs to submit an annual public report to the above-mentioned international organizations, to summarize the SRMA’s work and how the SRMA maintain its goal in particular.

The Secretary-General will be appointed by the Council and responsible to the Council. The Secretary-General should execute the Council’s orders and take charge of the daily operation of the SRMA. Considering that China is the largest coastal State in the SCS, the Secretary-General might always be a Chinese citizen.Footnote61 The Deputy Secretary-Generals would be citizens from the other five coastal States in the SCS. The secretariat of the SRMA will be consisted of six sub-committees from the six coastal States in the SCS (see ). The members of the six sub-committees are appointed by the six coastal States in the SCS according to the principle of equals. At the same time, the six sub-committees should submit advisory opinions to the Council.

Figure 4. Possible organizational structure of a spratly resource management authority.

Source: Qi, et al., Cooperative Research Report on Joint Development in the South China Sea: Incentives, Policies & Ways Forward, 22; Valencia, et al., Sharing the Resources of the South China Sea, 207.

Scholars from the six coastal States in the SCS can propose feasible plans by track II dialogs, and then reach to consensus through track 1.5 dialogs. On the basis of the consensus of scholars, the governments of the six coastal States will establish the common scheme of the SCS joint development. The decision-making process of the SCS joint development should moderately reflect supranational principle. When the decision-making system is being designed, on one hand, the hegemonic position of great powers should be avoided; and on the other hand, it should also prevent that small powers stand together to object the great powers.

Decision-making process of the SMRA might be through unanimity, consensus, weighted voting, or chambered voting, or through some combination of these methods. Decision could be taken by simple majority, or a two-thirds or three-quarters majority, with or without equal or special veto powers.Footnote62

4. Conclusion

For the jurisdiction solution of the disputed resources in the SCS, the joint development is a kind of provisional arrangement, but it is the only pragmatic approach for the six coastal States. Since 2017, thanks to the concerted efforts made by China and regional countries, the situation in the SCS has cooled down and returned to stability. Good relations amongst the SCS coastal States and the political will to make decisions are the two conditions prior to serious discussions on joint development arrangements. The first condition for joint development has been basically met; the second condition is in a consensus process. So the serious discussion of joint development is entering a window period.

To seize the rare historical opportunity, China, as the largest coastal State in the SCS, has actively initiated joint development proposal with the Philippines and Vietnam since 2017. China’s policy choices on the SCS joint development can be classified into three types: clear government policies, implicit government policies, and a possible policy choice (see ). The clear government policies include four points: to promote good faith in the SCS; to limit unilateral activities in disputed areas; to focus on less sensitive areas of the SCS; to reach joint development arrangements by establishing relevant working mechanism. The above-mentioned four policies can be found in the statements and released MoU by the Chinese government. The implicit government policies include two points: to begin the process in areas where there are only two claimants; to define sea areas for the joint development by seeking consensus. The above-mentioned two policies may not be found in open statements by the Chinese government, but can be testified by the actual behaviors of the Chinese government during the joint development negotiation. The possible policy choice is to discuss the feasibility of setting up a SRMA with supranational character. Perhaps Chinese government will not accept this policy choice in the near future, but it is the very path worthy of China’s consideration.

The ASEAN claimants should also seize the rare historical opportunity of joint development in the SCS. Joint development between the ASEAN claimants and China can bring greater confidence to the South China Sea to alleviate some of the uncertainties that have plagued the area for the past two decades. The spillover effect, generated by the cooperation in the field of oil and gas resource, will create a more stable environment for future maritime delimitation negotiation among the SCS coastal States. More importantly, the way of gradual functionalism, beginning with the cooperation in the field of oil and gas resource, will finally lead to the interdependence among the SCS coastal States and the regional permanent peace.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Huaigao Qi

Huaigao Qi is an Associate Professor of International Relations and Vice Dean of Institute of International Studies at Fudan University.

Notes

1 Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “China Adheres to the Position of Settling Through Negotiation.”

2 Xinhua, “China, Vietnam Reach Consensus on Trade.”

3 Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation on Oil and Gas Development.”

4 Beckman et al., “Moving Forward on Joint Development,” 312.

5 Miyoshi, “The Joint Development of Offshore Oil and Gas,” 3; Qi, et al., Cooperative Research Report on Joint Development, 3.

6 CNPC Economics & Technology Research Institute, “2050 World and China Energy Outlook”; Reuters, “China’s Energy Demand to Peak in 2040.”

7 International Energy Agency, “Gas 2018: Analysis and Forecasts to 2023.”

8 See note 6 above.

9 International Energy Agency, “Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2017,” 11 & 55.

10 Ibid., 55.

11 Li, “Policy Adjustment in Resources Development,” 106; Hainan Daily, “Oil and Gas Resources Development.”

12 Chinese National Development and Reform Commission and State Oceanic Administration, “Vision for Maritime Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative.”

13 Xinhua, “China Plans to Build Hainan into Pilot Free Trade Zone.”

14 Hu, “Hu Jintao’s Report at 18th CPC National Congress.”

15 Xi, “Xi Jinping’s Report at 19th CPC National Congress.”

16 Chinese Ministry of Natural Resources, “China Marine Economy Statistical Bulletin in 2018.”

17 See note above 15.

18 Xue and Cheng, “China’s Window of Opportunity in the South China Sea.”

19 Qi, “China’s Presence and Challenges in the South China Sea,” 12.

20 British Institute of International Law and Comparative Law, Report on the Obligation of States under Article 74(3) and 83(3), 19.

21 Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Foreign Minister Wang Yi Meets the Press.”

22 Xinhua, “Hainan Plan to Build a Pan-South China Sea.”

23 Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Joint Statement between the Government of the People’s Republic of China.”

24 Chinese Embassy in the U.S., “Remarks of Ambassador Cui Tiankai at Center for Strategic and International Studies.”

25 Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s argument, See: Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Chinese Foreign Minister and Philippine Foreign Secretary Talk.”

26 International Crisis Group, “Stirring up the South China Sea (IV),” i.

27 Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “The Operation of the HYSY 981 Drilling Rig.”

28 Green, “Countering Coercion in Maritime Asia,” 207.

29 See note 27 above.

30 Green, “Countering Coercion in Maritime Asia,” 223.

31 Ibid., 223.

32 Global Times, “China Redeploys HYSY 981 in South China Sea.”

33 International Crisis Group, “Stirring up the South China Sea (IV),” 8.

34 Hayton, “South China Sea.”

35 See note 2 above.

36 Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Chinese Foreign Minister and Philippine Foreign Secretary Talk.”

37 Beckman, et al., “Moving Forward on Joint Development in the South China Sea,” 318.

38 GOV.cn, “China, Vietnam Pledge to Properly Settle.”

39 Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “China and Vietnam Held the Twelfth Round Consultation.”

40 Ibid.

41 Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “China, Philippines Convene the Fourth Meeting.”

42 See note 3 above.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid.

47 Xinhua, “China and the Philippines Announced the Establishment.”

48 CNOOC, “CNOOC and Petrovietnam Signed Framework Agreement.”

49 McDorman, “Agreement on the Delimitation of the Territorial Seas,” 3745–3758.

50 Xinhua, “China and DPRK Signed Agreement between the Government.”

51 Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Maritime Affairs in the Eyes of the Director-General.”

52 See note 23 above.

53 Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “China Adheres to the Position of Settling Through Negotiation.”

54 Reuters, “Philippines Earmarks Two Sites for Possible.”

55 Beckman, “Legal Framework for Joint Development in the South China Sea,” 261.

56 International Crisis Group, “Stirring up the South China Sea (IV),” 17.

57 Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Statement of the Government of the People’s Republic of China.”

58 International Crisis Group, “Stirring up the South China Sea (IV),” 25.

59 Valencia, et al., Sharing the Resources of the South China Sea, 206–209.

60 Ibid.

61 Valencia, et al., Sharing the Resources of the South China Sea, 209.

62 Valencia, et al., Sharing the Resources of the South China Sea, 208.

Bibliography

- Beckman, R. “Legal Framework for Joint Development in the South China Sea.” In UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the South China Sea, edited by S. Wu, M. Valencia, and N. Hong, pp.: 251-266. Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2015.

- Beckman, R., C. Schofield, I. Townsend-Gault, T. Davenport, and L. Bernard. “Moving Forward on Joint Development in the South China Sea.” In Beyond Territorial Disputes in the South China Sea: Legal Frameworks for the Joint Development of Hydrocarbon Resources, edited by R. Beckman, I. Townsend-Gault, C. Schofield, T. Davenport, and L. Bernard. Cheltenham, pp. 312-331. UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2013.

- British Institute of International Law and Comparative Law. Report on the Obligation of States under Article 74 (3)and 83 (3)Of UNCLOS in Respect of Undelimited Maritime Areas. London, UK: The British Institute of International Law and Comparative Law, 2016.

- China Geological Survey of Ministry of Land and Resources. Xinzhongguo Haiyangdizhi Gongzuo Dashiji: 1949-1999 [Marine Geological Work Memorabilia of P.R. China (1949-1999)]. Beijing: Haiyang Chubanshe, 2000.

- Chinese Embassy in the U.S. “Remarks of Ambassador Cui Tiankai at Center for Strategic and International Studies.” July 13, 2016. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.china-embassy.org/eng/zmgxss/t1380730.htm

- Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “Maritime Affairs in the Eyes of the Director-General of the Department of Treaty and Law of Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs.” May 15, 2006. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://newyork.fmprc.gov.cn/web/wjbxw_673019/t255507.shtml

- Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “The Operation of the HYSY 981 Drilling Rig: Vietnam’s Provocation and China’s Position.” June 8, 2014. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1163264.shtml

- Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “China Adheres to the Position of Settling through Negotiation the Relevant Disputes between China and the Philippines in the South China Sea.” July 13, 2016. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1380615.shtml

- Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “Foreign Minister Wang Yi Meets the Press,” March 8, 2016. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1346238.shtml

- Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “Statement of the Government of the People’s Republic of China on China’s Territorial Sovereignty and Maritime Rights and Interests in the South China Sea.” July 12, 2016. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/nanhai/eng/snhwtlcwj_1/t1379493.htm

- Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “Chinese Foreign Minister and Philippine Foreign Secretary Talk about the Joint Exploitation of South China Sea,” July 25, 2017. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1480543.shtml

- Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “Joint Statement between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Republic of the Philippines.” Manila. November 16, 2017. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/2649_665393/t1511299.shtml

- Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “China and Vietnam Held the Twelfth Round Consultation of the Experts’ Working Group for Maritime Cooperation in Less Sensitive Areas.” December 11, 2018. Accessed August 31, 2019. https://www.mfa.gov.cn/nanhai/chn/wjbxw/t1620705.htm

- Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation on Oil and Gas Development between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Republic of the Philippines.” November 20, 2018. Accessed August 31, 2019. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/nanhai/eng/zcfg_1/t1616644.htm

- Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “China, Philippines Convene the Fourth Meeting of the Bilateral Consultation Mechanism on the South China Sea.” April 3, 2019. Accessed August 31, 2019. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjbxw/t1651097.shtml

- Chinese Ministry of Natural Resources. “China Marine Economy Statistical Bulletin in 2018,” April 11, 2019. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://gi.mnr.gov.cn/201904/t20190411_2404774.html

- Chinese National Development and Reform Commission and State Oceanic Administration. “Vision for Maritime Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative.” Xinhua. June 20, 2018. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-06/20/c_136380414.htm

- CNOOC. “CNOOC and Petrovietnam Signed Framework Agreement on Oil and Gas Cooperation in the Beibu Gulf.” Website of State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council. November 1, 2005. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.sasac.gov.cn/n2588025/n2588124/c4104044/content.html

- CNPC Economics & Technology Research Institute. “2050 World and China Energy Outlook.” Beijing, August 16, 2017.

- Damrosch, L. F., and B. H. Oxman. “Agora: The South China Sea, Editors’ Introduction.” American Journal of International Law 107, no. 1(2013): 95–97, January.

- Global Times. “China Redeploys HYSY 981 in South China Sea.” Huanqiu. June 27, 2015. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://world.huanqiu.com/exclusive/2015-06/6784218.html

- GOV.cn. “China, Vietnam Pledge to Properly Settle Maritime Issues.” October 15, 2011. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.gov.cn/misc/2011-10/15/content_1970431.htm

- Green, M., K. Hicks, Z. Cooper, J. Schaus, and J. Douglas. “Countering Coercion in Maritime Asia: The Theory and Practice of Gray Zone Deterrence,” The Center for Strategic and International Studies. May 2017. Accessed August 31, 2019. https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/170505_GreenM_CounteringCoercionAsia_Web.pdf?OnoJXfWb4A5gw_n6G.8azgEd8zRIM4wq

- Hainan, Daily. “Oil and Gas Resources Development in the South China Sea Will Be a New Economic Growth Momentum,” Hainan Daily. July 9, 2012. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://hnrb.hinews.cn/html/2012-07/09/content_2_8.htm

- Hayton, B. “South China Sea: Vietnam ‘Scraps New Oil Project’.” BBC News, March 23, 2018. Accessed August 31, 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-43507448

- Hu, J. “Hu Jintao’s Report at 18th CPC National Congress.” November 8, 2012. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2012cpc/2012-11/18/content_15939493_9.htm

- International Crisis Group. “Stirring up the South China Sea (IV): Oil in Troubled Waters.” Crisis Group Asia Report 275: 1-28. January 26, 2016. https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/north-east-asia/china/stirring-south-china-sea-iv-oil-troubled-waters

- International Energy Agency. “Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2017.” Paris, October 2017. Accessed August 31, 2019. https://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/WEO2017SpecialReport_SoutheastAsiaEnergyOutlook.pdf

- International Energy Agency. “Gas 2018: Analysis and Forecasts to 2023.” June 2018. Accessed August 31, 2019. https://webstore.iea.org/download/summary/1235

- Li, G. “Policy Adjustment in Resources Development in the South China Sea.” Guoji Wenti Yanjiu (International Studies), no. 6 (2014): 104-115.

- Li, G. World Atlas of Oil and Gas Basins. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

- McDorman, T. L. “Agreement on the Delimitation of the Territorial Seas, Exclusive Economic Zones and Continental Shelves in the Beibu Gulf (Gulf of tonkin) between the People’s Republic of China and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.” In International Maritime Boundaries, edited by D. A. Colson and R. W. Smith, Vol. V. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2005: 3745-3758.

- Miyoshi, M. “The Joint Development of Offshore Oil and Gas in Relation to Maritime Boundary Delimitation.” Maritime Briefing 2, no. 5 (1999). Accessed August 31, 2019. https://www.dur.ac.uk/ibru/publications/download/?id=236.

- Permanent Mission of China to the UN. Note Verbale CML/18/2009. May 7, 2009. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/vnm37_09/chn_2009re_vnm.pdf

- Qi, H. “China’s Presence and Challenges in the South China Sea in Recent Years and China’s SCS Policies in the Future.” Guoji Luntan (International Forum) 20, no. 1 (2018): 8–13, January.

- Qi, H., S. Xue, J. Liew, E. Fitriani, C. B. Ngeow, A. Rabena, T. H. BuiThi, and N. Hong. “Cooperative Research Report on Joint Development in the South China Sea: Incentives, Policies & Ways Forward.” May 27, 2019. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.iis.fudan.edu.cn/_upload/article/files/9f/21/992faf20465fae26c23ccce1ecc6/f003a68f-eb6a-4b09-a506-3c00897b0862.pdf

- Reuters. “China’s Energy Demand to Peak in 2040 as Transportation Demand Grows: CNPC.” August 16, 2017. Accessed August 31, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-cnpc-outlook/chinas-energy-demand-to-peak-in-2040-as-transportation-demand-grows-cnpc-idUSKCN1AW0DF

- Reuters. “Philippines Earmarks Two Sites for Possible Joint Oil Exploration with China.” Reuters. March 2, 2018. Accessed August 31, 2019. https://uk.reuters.com/article/philippines-china-southchinasea-energy/philippines-earmarks-two-sites-for-possible-joint-oil-exploration-with-china-idUKL4N1QK4CW

- U.S. Department of State. Spratly Islands in the South China Sea. Washington, D.C.: Department of State, 2015. Accessed August 31, 2019. https://cdn.loc.gov/service/gmd/gmd9/g9237/g9237s/2016587286.pdf.

- United Nations Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea. Brunei Darussalam’s Preliminary Submission Concerning the Outer Limits of Its Continental Shelf. May 12, 2009. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/preliminary/brn2009preliminaryinformation.pdf

- Valencia, M. J., J. M. V. Dyke, and N. A. Ludwig. Sharing the Resources of the South China Sea. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1991.

- Wang, Y., ed. Zhongguo Haiyang Dili [Ocean Geography of China]. Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe [China Science Publishing House], 2013.

- Xi, J. “Xi Jinping’s Report at 19th CPC National Congress.” Xinhua net. October 18, 2017. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/download/Xi_Jinping’s_report_at_19th_CPC_National_Congress.pdf

- Xinhua. “China and DPRK Signed Agreement between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea on the Joint Exploitation of Offshore Oil,” Website of the Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China, December 24, 2005. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2005-12/24/content_136430.htm

- Xinhua. “China, Vietnam Reach Consensus on Trade, Maritime Cooperation: Joint Statement,” Xinhua net, November 13, 2017. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-11/13/c_136749356.htm

- Xinhua. “Hainan Plan to Build a Pan-South China Sea Tourism Economic Cooperation Rim by 2020,” Xinhua net, July 26, 2017. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.xinhuanet.com/fortune/2017-07/26/c_1121383348.htm

- Xinhua. “China Plans to Build Hainan into Pilot Free Trade Zone,” April 13, 2018. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-04/14/c_137109412.htm

- Xinhua. “China and the Philippines Announced the Establishment of Inter-Governmental Joint Steering Committee and Inter-Entrepreneurial Working Group.” August 29, 2019. Accessed August 31, 2019. http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/leaders/2019-08/29/c_1124938959.htm

- Xue, L., and Z. Cheng. “China’s Window of Opportunity in the South China Sea.” The Diplomat, July 26, 2017. Accessed October 23, 2019. https://thediplomat.com/2017/07/chinas-window-of-opportunity-in-the-south-china-sea/