ABSTRACT

This contribution takes stock of ASEAN centrality in trade and the emerging policy area of trade infrastructure, also known as connectivity. ASEAN centrality in the East Asian and Indo-Pacific regions has increasingly been called into question, but most studies have failed to specify what ASEAN centrality is and how it can be measured. Outlining both a technical and a substantial definition, this study presents the state of affairs and current trends of ASEAN centrality in the areas of trade and connectivity. Disaggregating the concept, the paper assesses ASEAN’s role in the two policy areas as a leader, convener, convenience, and necessity. ASEAN’s central position in trade is under threat due to a changing environment, with trade ties increasing between ASEAN’s partners. In addition, ASEAN leadership in the RCEP negotiations has been symbolic rather than substantial. In connectivity, ASEAN centrality is even more questionable. Its regional connectivity vision is contested by other states and relationships act as conduits for the exercise of power.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

For many decades, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations' (ASEAN) position as a central actor in various East Asian institutional arrangements has been the topic of political and economic analysis and government rhetoric. In reporting on the East Asian conference circuit, there are frequent references to ASEAN as a central player, leading and guiding negotiations. Academic studies have supported this narrative, highlighting ASEAN centrality in the East Asian institutional architectureFootnote1 and lauding the organization’s success in “living with giants” within its macro-region.Footnote2 ASEAN’s management of powerful external actors, primarily China and the United States (US), but also Japan and, increasingly, Australia, India, South Korea, and the European Union (EU), has been seen as a major achievement of the organization, often judged to be more significant than its internal progress. ASEAN’s sophisticated system for engaging external partners, consisting of a hierarchical mechanism endowing them with access to forums led by ASEAN as well as bilateral dialogues, is unique for a regional organization in the Global South and testament to the high importance that partner relations have been accorded.

The majority of regional forums in East Asia follow the so-called ASEAN+ logic, with ASEAN at the center of a revolving constellation of partner governments, creating concentric circles of regionalism in East Asia.Footnote3 The most notable of these are certainly the nested forums of the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and the East Asia Summit (EAS), which all center on ASEAN. These dialogues are complemented by various bilateral security cooperations between individual ASEAN states and China or the US, creating a complex security network.Footnote4 A similar architecture has taken shape in the field of trade, where ASEAN has concluded a variety of ASEAN+1 FTAs from 2005 to 2009. This has been complemented with economic institution building under the ASEAN+3 (APT), which emerged as a consequence of the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) and has since become a hub for East Asian financial and economic negotiations.Footnote5

Despite these inarguable successes in establishing security and trade institutions, ASEAN centrality as a whole appears to be on the decline. This is particularly apparent in the realms of trade and connectivity. In trade, ASEAN has seen its central position overtaken by current developments. Its ASEAN+1 FTAs have only seen little usage and concurrently, its external partners have negotiated a number of bilateral FTAs, excluding ASEAN. Partly as a response to these trends, ASEAN and its FTA counterparts are in the process of negotiating a macro-regional FTA, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). It is not obvious, however, that RCEP negotiations are led or driven by ASEAN, nor that RCEP will lead to a strengthening of its centrality. Instead, the RCEP appears to consolidate a changed state of affairs in East Asian trade relations, one that is more multipolar in nature and one that relies less on ASEAN as a fulcrum and a norm provider.

The organization has also found it difficult to establish centrality in emerging policy areas, such as the area of infrastructural development frequently labeled connectivity, which utilizes negotiation processes separate from trade and security dialogues. Here, ASEAN has made attempts to establish centrality by releasing a connectivity master plan in 2010, aiming to rally external partners around a common vision. This, however, has not been truly successful for reasons that will be outlined further below. Still, ASEAN continues its efforts to consolidate its central position in the East Asian and Indo-Pacific institutional architecture. The 2019 ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific is a rhetorical device aiming to reiterate ASEAN centrality in trade, security, and connectivity, which are all prominently mentioned in the document. This is in line with past ASEAN efforts. Since 2010, ASEAN summit outcome documents have, without fail, called for a consolidation of the organization’s central position in the wider East Asian region.Footnote6 The ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific continues this trend, but is also representative of the persistent issues of ASEAN centrality: short of providing innovations to support ASEAN centrality, the document does not propose any novel institutional mechanisms. Considering its activities as a convener of forums, ASEAN deserves credit as a player punching above its weight in international politics and providing public goods, if not leadership as traditionally understood. Still, the challenge for ASEAN at the turn of this decade remains how to preserve its historically central position against a changing external environment.

Reflecting this changed state of affairs, recent academic production has increasingly called into question ASEAN centrality in general terms. Its ability to lead regional forums has been questioned in connection with the rise of ChinaFootnote7 or its persistent internal constraints in achieving organizational coherence.Footnote8 Finally, authors have questioned ASEAN’s ability to weather the increasing tensions between great powers in the region.Footnote9 It has been observed that ASEAN states continue to pursue divergent strategies both within economic and security forums, leading to issues in institutional leadership.Footnote10 Some authors chalk these constraints up to the ASEAN Way. David Martin Jones and Nicole Jenne argue that the ASEAN Way has been at once the feature on which East Asian regional institutionalization has been based, but that it also limits ASEAN’s role in these forums in the long run.

ASEAN’s crucial norm of non-interference and its practice of nonbinding consensus inhibit deeper integration either within ASEAN or the wider East Asian region. Moreover, the contradiction between official consensus and actual practice has a damaging effect. The longevity of the institutional arrangement by no means entails progress, but rather the recourse to process without resolution.Footnote11

This article seeks to assess the state of ASEAN centrality beyond the much-analyzed realm of security in the areas of trade and connectivity. In the following section, this article will outline a framework to analyze ASEAN’s contributions to institutional arrangements, providing a yardstick for how to measure ASEAN’s institutional centrality across policy areas. Following the theoretical section, this paper will outline the state of ASEAN centrality in trade and connectivity.

2. From a technical toward a substantial view of ASEAN centrality

For a term that sees such wide usage in academic and policy circles, ASEAN centrality has remained theoretically underspecified for a remarkably long time. The roles of ASEAN as a central actor in East Asian regionalism have been described in various ways, with ASEAN acting as “[…]the ‘leader’, the ‘driver’, the ‘architect’, the ‘institutional hub’, the ‘vanguard’, the ‘nucleus’, and the ‘fulcrum’[…]” of East Asian institutions.Footnote12 Only recently, some scholars have attempted to explain how ASEAN centrality has been attained and under which conditions it may persist. Promising inroads have been made by Caballero-Anthony’s social-network approach from 2014, as well as Tan’s 2017 framework focusing on the substance of ASEAN’s contributions to its forums.

Caballero-Anthony’s social network approach assesses the organization’s position in technical terms, tying ASEAN’s centrality to its high number of ties to other powers in the region as well as the constant exchange of material and ideational resources between them.Footnote13 She disaggregates centrality into two bases: centrality within ASEAN as well as centrality of ASEAN in its regional environment. Centrality within ASEAN is defined as the proximity of the ties between ASEAN member states, intra-ASEAN coherence leading to centrality by way of enabling the organization to “gain access to resources, set the agenda, frame debates, and craft policies that benefit its member states.”Footnote14 The centrality of ASEAN, meanwhile is a consequence of its high amount of ties to external partners as well as constant exchanges of resources and informationFootnote15 , a higher degree of which should enable the organization and its member states to procure resources more easily. Caballero-Anthony juxtaposes network centrality with relative power, arguing that ASEAN has the potential to shape outcomes despite its relative lack of power. This is an argument that may be criticized, as networks are agnostic to the exercise of power. In fact, networks may become conduits for the exercise of power by more powerful actors, even in the absence of centrality. In the following two chapters, the number of ties in trade and connectivity will be assessed with the aim of analyzing the degree of ASEAN centrality in a technical sense.

This contribution seeks to enrich the social-network understanding of ASEAN centrality with a more substantial view, with the aim of describing centrality not just in quantitative but also in qualitative terms. For this, Tan’s contribution provides a useful framework.Footnote16 Tan outlines five possible roles for ASEAN within its regional forums: regional leader, regional convener, regional hub, regional driver of progress, and regional convenience. Tan’s five concepts, however, exhibit significant overlaps. For reasons of simplicity, I will aggregate them into three, treating the concepts of regional leader and driver as well as those of hub and convener as analytically equivalent for the purpose of this paper. The idea of the convener or hub refers to ASEAN’s agency in providing a forum for other states to interact in.Footnote17 The hub concept is fairly close to Caballero-Anthony’s technical understanding of ASEAN centrality as a result of a higher number of ties. This concept also includes a perspective on ASEAN centrality as a way to avoid marginalization rather than providing leadership in East Asia. The concept of regional convener views ASEAN primarily as a builder of forums and a generally neutral entity, able to broker compromises. The concepts of regional leader and driver of progress focus more on ASEAN’s role as an agenda-setter as well as its performance legitimacy.Footnote18 While the concept of a regional leader takes the view of ASEAN as providing intellectual leadership through its ability to find negotiation equilibriums, the concept of regional driver rather denotes leadership through the implementation of stated aims. The concept of regional convenience, finally, sees ASEAN centrality as a path-dependent feature of East Asian regionalism, with ASEAN clinging to a largely ineffective role as a central player.Footnote19 Tan focuses only on the convenience provided to ASEAN, however, and neglects the ways in which ASEAN centrality may also be convenient to other states. One way in which ASEAN centrality can be convenient to external partners is through the provision of the ASEAN Way as a convenient foil, providing forums with the norms of sovereignty and noninterference to avoid substantial cooperation. Another convenient effect of ASEAN leadership may be the ability for powerful states such as Japan or China to lead from behind, significantly influencing negotiations and outcomes all while formally supporting ASEAN leadership. There may also be a fourth type of ASEAN centrality, which has been neglected by Tan in his assessment. In this role, ASEAN may be characterized as a regional necessity. This refers to the fact that the large geographic size and population of the region coupled with its economic dynamism are a necessary consideration for actors interested in future-proof agreements. As the states of Northeast Asia face demographic and likely economic decline in the long run, the majority of ASEAN’s member states hold continued potential as a growing base for production and consumption. ASEAN may therefore be accorded a central position because it is a necessary counterpart for forward-looking trade and connectivity institutions. The four roles contributing substantially to ASEAN centrality are outlined in below.

Table 1. Four theorized roles contributing to ASEAN centrality.

In the following sections, what will be assessed is the degree to which ASEAN’s agency in creating and maintaining regional forums in trade and connectivity is in line with the criteria of these characterizations of centrality. Before conducting this analysis, however, it is important to discuss how ASEAN’s centrality in technical terms and its substantial centrality, following the categorization just made, are related. As mentioned previously, most discussions of ASEAN centrality remain unspecific regarding the bases of the phenomenon. Many scholars have emphasized ASEAN’s role as a convener, usually coupled with its role as a broker or neutral entity of some sort. Increasingly, observers have called upon ASEAN to complement this role with substantial contributions to sustain its central position, providing more leadership. The late Surin Pitsuwan called for more “centrality of substance”, meaning to go beyond simply being the structural center of the institutional setup and providing more hands-on leadership such as “[…] setting the agenda, providing direction and resolving disputes.”Footnote20 This is also echoed by Caballero-Anthony, who sees the main challenge to ASEAN centrality as “its ability to maintain consensus, carry out collective action and achieve its stated goals.”Footnote21 It is therefore fair to assume that it is ASEAN's centrality in technical terms, e.g. a position with a high number of ties to other states, that enables it to carry out the roles described above, leading to more substantial centrality over time.

The key challenge for ASEAN therefore remains the transition from a period in which centrality could be attained simply by providing a venue for other actors, acting as a hub or a convener, toward a role as a leader or driver of negotiation processes within these forums. It is not clear, however, whether ASEAN is capable of delivering this substance in the areas of trade and connectivity. In security, Acharya has noted that proposals on regional cooperation put forward by other states always needed ASEAN modification and approval before successfully entering into the East Asian institutional architectureFootnote22, making it a sort of clearing house. It is not clear that this is the case in trade and connectivity. The RCEP negotiations have emphatically not come about due to ASEAN’s progress on the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) agenda, but rather due to ASEAN’s ties to other East Asian states and the inability of other actors to credibly launch inclusive negotiations. As the system of ASEAN+1 FTAs has given way to a more complex, interlinked network of East Asian trade agreements, ASEAN may see its centrality in trade under threat. The area of connectivity poses a different kind of challenge to ASEAN centrality. ASEAN has only recently made moves to assert its centrality within this new policy area. ASEAN’s counterparts, however, are contesting its connectivity vision, challenging ASEAN centrality. The absence of dedicated forums to negotiate East Asian connectivity means that ASEAN centrality may not be attained in the first place, despite all efforts. Using the disaggregated concept of centrality defined above, I will outline if ASEAN has been central in these policy areas, and if yes, how. In addition, I will discuss the substantial roles ASEAN has played in trade and connectivity and which of them are concretely under threat.

3. The regional comprehensive economic partnership (RCEP) and ASEAN centrality in trade

Next to the realm of security, trade is usually acknowledged as the policy area where ASEAN centrality is most clearly established. Upon closer inspection, the criteria for this centrality are not clearly laid out in much of the literature discussing ASEAN’s free trade agreements. What is clear is that ASEAN has been highly successful in building a network of FTAs within the East Asian region during the 2000s, all centering on ASEAN as an organization. These agreements with Australia and New Zealand, China, India, Japan, and South Korea have dominated the East Asian trade architecture for the past decade, weathering the storm of several alternative proposed frameworks, such as the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). This paper focuses on institutional centrality in trade rather than centrality in trade in toto. It is clear that ASEAN remains a marginal player in East Asian trade relations, with China, Japan, South Korea and various other states far outstripping ASEAN’s trade prowess. For this reason, trade institutions, primarily FTAs, are the object of this analysis, rather than trade per se.

Many regional observers see the current negotiations for the RCEP as auguring another era of ASEAN centrality, with the organization taking a leading role in consolidating its multiple agreement into a mega-regional agreement, solving the noodle-bowl problem of East Asian trade agreements.Footnote23 At the same time, however, questions remain over the commitments contained within ASEAN’s trade agreements. Many studies have noted that ASEAN FTAs are not always substantial in nature, usually hewing close to the content of WTO agreements.Footnote24 While there are indications that the RCEP may be different, including a range of WTO Plus issuesFootnote25 , it remains to be seen how much additional substance will be contained in a potential RCEP agreement.Footnote26 In the meantime, it makes sense to assess the state of ASEAN centrality in the realm of trade both in a technical as well as a substantial sense. It has been close to ten years since the conclusion of the last of the ASEAN+1 FTAs, with many additional agreements concluded since then between ASEAN’s partners. In addition, it remains to be assessed what type of substance ASEAN has provided in the realm of trade, both prior to and following the beginning of the RCEP negotiations in 2012.

3.1. ASEAN centrality in trade

ASEAN’s central role in regional trade negotiations is rooted in the Sino-Japanese regional rivalry. Following the beginning of institutionalized economic and financial cooperation in East Asian following the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis through the ASEAN+3 process, China and Japan formulated competing visions of the regional economic architecture. China’s proposal of the East Asia Free Trade Area (EAFTA) focused on the APT countries was countered by the Japanese proposal of the Comprehensive Economic Partnership of East Asia (CEPEA) with the membership of the current-day RCEP.Footnote27 In the years following the AFC, ASEAN pursued bilateral FTAs with all states proposed under the CEPEA, concentrating on achieving rapid negotiation results. Around 2010, this East Asian trade agreement architecture was fully established with ASEAN at its center. In parallel, discussions around a multilateral East Asian FTA lingered, disagreements over the EAFTA and the CEPEA persisting. Following several years of deliberations, it was the TPP negotiations that rallied East Asian states around the RCEP, bypassing the Sino-Japanese rivalry through the instatement of ASEAN as a central convener and negotiator.Footnote28 ASEAN set in motion its internal processes, reaching an intra-ASEAN agreement at its 19th summit in 2011 and agreeing on guiding principles and objectives for the negotiations in 2012.Footnote29 The entire process is reflective of ASEAN’s role as a regional convener, as theorized.

Despite ASEAN formally being in charge of the negotiations, questions have been raised over the actual centrality of ASEAN within the RCEP. Officially, all outcome documents refer to ASEAN centrality and ASEAN events are where progress on the negotiations are reported. Still, the original proposal for the structure of today’s RCEP has come from JapanFootnote30 and studies as well as sources familiar with the negotiation process bear out the strong Japanese involvement in the negotiations.Footnote31 China has also attempted to take charge of the negotiations at several points in timeFootnote32 , and Chinese elites have openly voiced skepticism of the value of ASEAN leadership in negotiations.Footnote33 Finally, India has been vocal with its requirements for a potential agreement, particularly related to intellectual property rights and market accessFootnote34 , culminating in its recent withdrawal from the RCEP. This calls into question ASEAN’s role as a leader, as crucial agenda setting has come from other participants. Individual ASEAN member states may have played a more substantial role in the negotiations. During its 2018 chairmanship and beyond, Singapore has appeared strongly interested to move forward with negotiations.

There are reasons to question substantial ASEAN centrality in trade, not just in the ongoing RCEP negotiations, but also within its concluded ASEAN+1 FTAs. First, the FTAs are not particularly ambitious and highly divergent in content, suggesting a high degree of external partner impact. Second, the FTAs are more ambitious than ASEAN’s own economic cooperation agenda, the ASEAN Economic Community, suggesting limits to ASEAN’s substantial leadership in external negotiations.

The role of ASEAN as a leader must be questioned when looking at the content of its various +1 FTAs, which have been criticized for their lack of ambition, and which differ significantly in their content and degree of commitment. ASEAN-FTAs tend to be shallow in nature and hew close to existing multilateral agreements, adding little additional value. In terms of differences between ASEAN+1 FTAs, one example is the liberalization rate of trade in goods, which is 76.5% for the ASEAN-India FTA, but above 90% for the other FTAs, suggesting a limited ability of ASEAN to negotiate more progressive agreements when faced with opposition. Rules of origin are also highly divergent across ASEAN+1 FTAs.Footnote35 It is clear that the involvement of ASEAN in these agreements did not lead to a homogenization in outcomes, calling into question ASEAN’s ability to ensure coherence in its external agreements and therefore also to act as a leader in multilateral negotiations.

The second point that challenges the notion of ASEAN centrality is the fact that many ASEAN-FTAs such as the ASEAN-Japan FTA contain more specific commitments than ASEAN’s internal economic agreements.Footnote36 ASEAN’s own trade facilitation scheme, the ASEAN Economic Community, has not made significant progress in the past years on crucial issues such as non-tariff barriers.Footnote37 This calls into question ASEAN’s ability to provide value by leveraging its own trade facilitation experience in its external relationships. It appears that the process is rather the other way around, with external partners impacting on ASEAN’s internal economic cooperation efforts. This may act as a detriment to ASEAN centrality, as it inhibits the forming of an intra-ASEAN consensus before engaging with external partners. Given the fact that ASEAN is not a customs union, it also enables member states to defect from the regional bloc, as happened in the cases of Vietnam, Singapore, and Malaysia joining the TPP negotiations without the participation of the other ASEAN member states.Footnote38

Taken together, it appears that ASEAN centrality in trade has been primarily a convenient foil for other negotiating parties, shielding them from discussions of substantial leadership and its outcome by focusing rather on centrality in a formal sense. Various counterparts such as India and Japan have managed to include their preferences in the ASEAN+1 FTAs, calling into question ASEAN’s ability to truly lead the negotiations. In the following, I will argue that threats to ASEAN centrality today do not only emanate from these limitations, but are exacerbated by contextual factors undermining the preconditions for ASEAN centrality in trade: ASEAN’s position has become less central in technical terms, undermined by a proliferation of institutional trade ties between other RCEP parties. In addition, ASEAN’s substantial centrality within the RCEP remains questionable, particularly its ability to lead, apparent in various statements on the negotiation process.

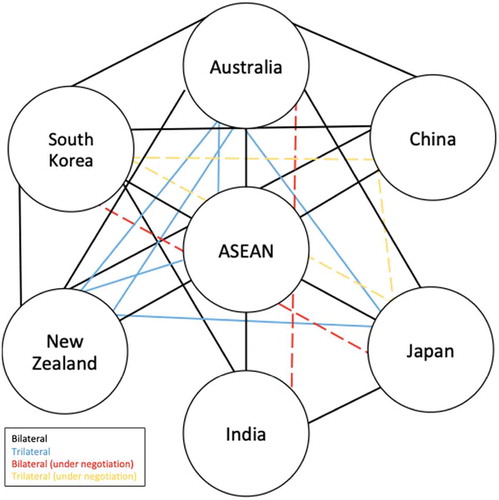

3.2. Displacement of ASEAN centrality in trade

Assessments of ASEAN centrality in trade appear to depart from an outdated state of affairs. Toward the late 2000s, when all currently existing ASEAN+1 FTAs were concluded, ASEAN found itself at the center of the East Asian trade network. Only two non-ASEAN FTAs were concluded among RCEP states prior to 2010, which were the Australia-New Zealand FTA (1983) and the New Zealand-China FTA (2008). But since then, things have changed considerably. Eight FTAs have since come into force between other RCEP states (India-South Korea in 2010, India-Japan in 2011, Korea-Australia in 2014, Japan-Australia in 2015, China-Australia in 2015, China-South Korea in 2015, New Zealand-South Korea in 2015 and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership [CPTPP] in 2018). An additional three FTAs are under negotiation (Japan-Korea since 2003, India-Australia since 2011, and China-Japan-South Korea since 2015). Not all of these are more substantial than the ASEAN+1 agreements and some of them, such as the strongly contested Japan-Korea FTA, may never come to pass. Still, these ties have repercussions for ASEAN centrality, as they challenge ASEAN as the fulcrum around which the East Asian trade system and RCEP are built. illustrates the current state of the East Asian trade network, with ASEAN at its center.

So what exactly does ASEAN centrality under the RCEP consist of? Some observers have suggested that RCEP supports ASEAN centrality due to the fact that the entirety of ASEAN’s membership is included, as opposed to the TPP negotiations, which only included some ASEAN states.Footnote39 This seems like a weak criterion for ASEAN centrality, although it does support the view that the ASEAN Way plays a role with its insistence on treating ASEAN as one. From the vantage point of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam, this may be commendable due to their difficulties in reducing their trading costs and their reliance on the ASEAN-6 states for external recognition and the conclusion of agreements.Footnote40 The insistence on an ASEAN-as-one approach may therefore preserve ASEAN centrality in the sense that it attempts to prevent divergences within the membership. It is less clear, however, what ASEAN leadership provides to non-ASEAN members of the RCEP. Generally, ASEAN has been described as a convener for RCEP negotiations.Footnote41 By this token, ASEAN is central in RCEP negotiations because it launched them and consistently provides a forum for discussion. This argument should be taken seriously as no other East Asian actor could convene such negotiations without accusations of hegemonic behavior, particularly China and Japan, but also South Korea or another actor outside the ASEAN+3. Still, ASEAN centrality being a given simply by way of ASEAN having convened the forum appears to be too weak a criterion to argue that the organization remains in the driver’s seat.

What about substantial contributions to the RCEP negotiations? While commentators from Southeast Asia as well as external analysts assert that the RCEP process is driven by ASEANFootnote42 , this is not fully clear when assessing the state of negotiations. The focus on procedural factors rather than substance within the ASEAN+1 FTAs appears to be mirrored in current RCEP negotiations. As Wang argues “[…] the level of consensus and timely completion of the RCEP negotiations are of secondary importance; for ASEAN, the key is to launch an ASEAN-centered process.”Footnote43 While Hsieh highlights various cases of cross-fertilization between existing ASEAN+1 FTAs and the RCEP, there are also some areas in which the RCEP will likely draw from the preferences of non-ASEAN members. One such issue is customs reforms, which are already a contentious issue in the existing ASEAN-Japan FTA and which Japan continues to push for during the RCEP negotiations.Footnote44 Another issue is the restrictive position by India on market access and intellectual property rights. This challenges the view of ASEAN as a substantial driver of the content of the RCEP. It also highlights that ASEAN as a provider of regional convenience may act as a foil for other actors to attain their negotiation objectives within the RCEP, all the while preserving the illusion of ASEAN centrality and avoiding public accusations of dominant or hegemonic behavior.

Substantial contributions by ASEAN are likely to come from some of its member states rather than the organization as a whole. Singapore had a leading role during its 2018 ASEAN chairmanship, during which it initially aspired to a conclusion of the agreement in the same year. Throughout the year, the Singaporean leadership frequently appeared alongside that of Japan, calling for a swift conclusion of the negotiations. This appears to suggest that individual pro-free trade ASEAN countries may occupy central positions as leaders, but not ASEAN as a whole.

ASEAN’s general focus on procedural centrality rather than substantial content does not appear to be shared by the Northeast Asian states. China, Japan, and South Korea have appeared more interested in access to each other’s markets than in access to Southeast Asian markets, a fact which has been relayed by a person familiar with the negotiations.Footnote45 The states are also more interested in substantial trade facilitation rather than symbolic agreements aiming to cement their status, unlike ASEAN, which appears to be satisfied with agreements that are primarily rhetorical in nature. This makes sense given their already high level of reciprocal trade and the impact that a potential liberalization may have on their economies. China, Japan, and South Korea are the three major economies within the East Asian trade agreement network that remain with a low number of ties between one another. From this vantage point, new institutional ties between the three countries are more attractive than a deepening or strengthening of ties to other actors within the network, the prospective growth and size of the ASEAN market notwithstanding. Such inclinations of the three Northeast Asian countries are apparent in their statements at trilateral negotiations. At the recent 15th round of negotiations on the China-Japan-ROK FTA in Tokyo in April 2019, the press release read the following:

“This round of negotiations is the first one after the three parties reached a consensus on comprehensive speed-up negotiations. […] The three parties unanimously agreed to further increase the level of trade and investment liberalization based on the consensus reached in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP) in which the three parties all participated, and to incorporate high-standard rules to create a RCEP Plus free trade agreement.”Footnote46

This highlights that substantial ASEAN centrality under the RCEP is at a minimum being questioned, with the Northeast Asian partners leveraging the RCEP negotiations to further trilateral talks, in a sort of forum shopping. In this case, it is possible that the RCEP is seen primarily as a clearing-house for Northeast Asian states to drive negotiations between themselves. This threatens ASEAN centrality in trade negotiations due to the creation of parallel structures. Nonetheless, Northeast Asian states may have an interest in keeping ASEAN at the table due to its role as a current and future growth market. Although ASEAN remains marginal for the trade amongst the APT, it will likely play a bigger role both as a producer and a consumer in the future. This suggests some merit to the centrality of necessity argument, with ASEAN retaining a privileged position due to its future potential as an economic growth engine for East Asia and the Indo-Pacific.

To summarize, ASEAN centrality in trade is being threatened by changing contextual factors. It is clear that historically, ASEAN has not played a role as a regional leader in trade. Instead, it has acted primarily as a regional convener, kick-starting negotiations on trade at a time when relations between other Asian countries were difficult. This is also true for the RCEP negotiations, which ASEAN launched in the absence of another actor capable of doing so. But despite this role, ASEAN faces a changed terrain with less centrality in a technical sense due to higher connectedness between its external partners. In addition, some countries such as China, Japan, and South Korea appear to have become more interested in and capable of conducting substantial trade negotiations. ASEAN’s role as a regional convenience, acting as a normative foil for trade agreements that, for the most part, did not see significant usageFootnote47 , may therefore have outlived its days. Modern East Asian regional trade agreements appear to be more ambitious in natureFootnote48 , which leads to a waning of ASEAN centrality. Still, this does not mean that ASEAN centrality will be a thing of the past. The envisioned growth of the Southeast Asian economies coupled with increases in competitiveness may see the region occupy a more economically attractive role for Northeast Asian countries facing a demographic and a potential economic decline. While the currently large amounts of trade in Northeast Asia disadvantage ASEAN, future developments may once again favor ASEAN centrality. This may also spell danger, however, as actors currently capable of leveraging their power, such as China, and Japan, may attempt to establish an agreement favorable to them, anticipating a more powerful and potentially more coherent ASEAN in the future.

4. Centrality without institutions? ASEAN centrality in connectivity

Over the past decade, infrastructure development, commonly referred to under the uniquely Asian term of connectivity, has emerged as a new and distinctive policy area in which states are jockeying for influence in Southeast Asia. Faced with domestic economic slowdowns, China, Japan, and recently South Korea have identified Southeast Asian countries as attractive export markets for their construction service industries. Despite broader use of the term in some contexts and also by ASEAN, this paper takes connectivity to refer primarily to physical links between states, including roads, ports, and railroads. This is consistent with the practical application of the concept within ASEAN, which rhetorically emphasizes social and institutional dimensions of connectivity, but practically prioritizes physical connectivity.Footnote49 In addition, this paper addresses centrality in connectivity institutions, not centrality in connectivity in toto. Northeast Asia generally has more developed infrastructure than Southeast Asia and many states, including the US and the EU, are well connected with East Asia, despite their geographical distance.

The majority of ASEAN member states have significant infrastructure construction and investment gaps. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has estimated an annual Southeast Asian infrastructure funding gap of US$ 184 billion.Footnote50 The majority of ASEAN states have relied on official development assistance, foreign direct investment, and infrastructure loans to make up this gap, frequently from Northeast Asian sources. In order to ensure that it remains in charge of its own infrastructural destiny, ASEAN has begun to outline regional connectivity blueprints, with the first Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity released in 2010. Following some frustration with the contents of this plan, the organization released the updated Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025 in 2016, which has been more positively received.Footnote51 Since the launch of ASEAN’s master plans, there has been a flurry of connectivity meetings, forums, strategic plans and commitments, by a variety of states and international organizations, including APEC and the Asia-Europe Meeting. The most significant of these are clearly the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as well as the Japanese Partnership for Quality Infrastructure (PQI). Activities by South Korea, the US, Australia, India, and the EU contribute to what increasingly appears to be a new arena for geo-economic competition.

Despite its efforts to set the agenda through a series of plans, ASEAN has struggled to establish institutional centrality in connectivity due to its continued high dependence on external partner funds and its lack of institutional forums to negotiate connectivity in an East Asian context. The situation in connectivity differs from that in trade in terms of context. Connectivity does not rely on bilateral agreements such as FTAs, but rather on the negotiation of individual projects between two partners. Connectivity investments tend to depend on the portfolio and the funds available by the partner in question (see ).

ASEAN has made efforts to improve its ability to fund its own regional connectivity through the establishment of an ASEAN infrastructure fund. This, however, has only been modestly successful, with the fund only mobilizing US$ 300 million from ASEAN member states and US$ 150 million of co-funding from the Asian Development BankFootnote52 and therefore only playing a marginal role. For this reason, the mobilization of external resources remains a key feature of ASEAN’s current connectivity master plan. Funding will be sought through multilateral development banks, the private sector, bilateral initiatives such as the BRI, the PQI or future EU, South Korean, or US funds.

4.1. ASEAN centrality in connectivity

ASEAN’s objective in attaining centrality in connectivity has been apparent from its first efforts to assert its agenda in the emerging policy area in 2009. At the 15th ASEAN Summit where plans for a regional connectivity blueprint were first unveiled, the Thai Prime Minister called for ASEAN connectivity “[…] to be linked with a larger East Asian connectivity where ASEAN will be connected to the rest of the Asia-Pacific region, bringing about progress and prosperity to all.”Footnote53 Most importantly, however, the Thai chair called for a connectivity master plan “plus”, to pursue connectivity beyond ASEAN, including Northeast Asia, South Asia and other regions.Footnote54 This illustrates that the organization was seeking to pursue a strategy similar to those in trade and security, with ASEAN relating to all relevant neighboring regions in a +1 fashion, with the aim of setting an agenda. Although the 2010 and 2016 master plans laid out various priorities aimed at attracting external support, ASEAN has not developed corresponding institutional coordination mechanisms. While ASEAN does conduct an annual connectivity symposium since 2010Footnote55, this is mainly seen as a venue to share information between ASEAN’s dialogue partners, rather than negotiate projects and their complementarity.Footnote56 Instead, ASEAN has pursued a typical +1 strategy, holding a series of meetings following the publication of the latest connectivity master plan in order to extract financial commitments from its partners. The first of a series of such meetings was held with Chinese counterparts, then with representatives of Japan, followed by South Korea.Footnote57 This strategy differs notably from the one taken in security and trade, where ASEAN has pursued a strategy of inclusive institutional balancingFootnote58 , aimed at involving various partners in multilateral negotiations, providing a venue for compromise. It also differs from ASEAN’s strategy in trade in another way, as relationships are not consolidated through institutional relationships like FTAs, but rather based on ad-hoc agreements.

As intra-ASEAN progress on connectivity has remained slimFootnote59 , ASEAN’s position vis-à-vis its external environment remains as important as ever. ASEAN has introduced several substantial and institutional reforms with its new connectivity master plan, aiming to assert centrality. Nonetheless, the way ASEAN plans to govern regional connectivity has constraints. Partners that back up alternative connectivity visions with resources may gain an edge over ASEAN as an organization.

4.2. Contestation of ASEAN centrality in connectivity

ASEAN’s institutional centrality in connectivity is difficult to measure and display in graphical terms. Seven of ASEAN’s ten dialogue partners (Australia, China, the EU, India, Japan, South Korea, and the US) as well as Germany are involved in ASEAN’s connectivity efforts in some fashion. ASEAN likely has the highest number of ties and hence, is at the center of a potential connectivity network. But this perspective lacks insight regarding the nature of the ties displayed. The relationships between ASEAN and the external partners in connectivity are loose, not solidified by agreements as in trade, and not institutionalized through a permanent dialogue or relationship. Instead, the ties are characterized by ad-hocism and subject to contestation by the external parties, which set alternative connectivity agendas and provide connectivity projects bilaterally. Despite it being an imperfect display of the network, provides an overview of the relevant actors in connectivity. Potential additional ties may be drawn between China and states participating in the BRI (South Korea) as well as Japan and states participating in the PQI (India), but they do not substantially alter the picture. Other connectivity initiatives are not yet sufficiently mature to draw conclusions from.

Of course, things are not black and white. ASEAN’s external partners have voiced their commitment during ASEAN-led events such as the Connectivity Symposium and have referred to the master plan in their plans of action, which guide their bilateral cooperation with ASEAN. Australia, China, South Korea, Japan and Germany have lent support to the planned activities of the master plan directly.Footnote60 Outside these efforts, however, all states have begun to set up connectivity strategies of their own. While early connectivity strategies such as the 2014 APEC Connectivity Blueprint were close to ASEAN’s own plan, more recent strategies such as China’s BRI and Japan’s PQI appear to be less coherent with the Southeast Asian connectivity agenda.

While the initiatives differ in the size of their budgets, project modalities as well as the progress of their agendas (with EU, US, and South Korea support still some way into the future), the fact remains that they all represent visions of Southeast Asian connectivity different from that of ASEAN. Only Australia and Germany provide truly demand-based support, which is minor in financial terms and focuses primarily on technical assistance to the ASEAN Secretariat and ASEAN’s formulation and project preparation activities. I will now take stock of the various partner initiatives and the ways in which they contest ASEAN’s connectivity agenda.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative is notable for its opacity, representing a combination of physical infrastructure projects, people-to-people exchanges as well as collaboration in trade facilitation, finance, and government relations. While there is considerable overlap with the ASEAN agenda, there are differences in degree such as an increased focus on financial integration.Footnote61 When it comes to physical infrastructure, there is a much-discussed risk that China may attempt to integrate its neighborhood into a hub-and-spokes type physical infrastructure architecture based on Chinese value chains, which may jeopardize intra-ASEAN integration, although some observers are cautiously optimistic.Footnote62 The conclusion of the ASEAN-China Strategic Partnership Vision 2030 at the 2018 ASEAN-China summitFootnote63 , which addresses synergies between the Belt and Road Initiative and the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity, may be seen as a move by ASEAN to defuse some of the tension inherent in the competitive visions on regional connectivity. There appears to be some movement in China’s position, with pushback to the Belt and Road Initiative in Southeast Asia resulting in strategic adjustments on China’s side. At the recent second Belt and Road Forum, China’s premier venue for negotiating its infrastructure investments abroad, China has suggested strengthening development policy synergy, with a view toward ASEAN’s and the EU’s strategies.Footnote64 Criticism of China’s ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ has been countered with the intention to multilateralize the BRI, working more closely with multilateral development banksFootnote65 , an adjustment that is closely in line with ASEAN’s master plan. In addition, China is establishing a mediation panel with the cooperation of Singapore, which should ensure more even-handed conflict resolution. If these modifications are implemented as planned, credit is at least partly due to ASEAN for its influence on the potentially revised BRI agenda.

The Japanese regional strategy appears to be closer to the connectivity vision of ASEAN, proven by high profile speeches as well as public project development cooperation roadmaps.Footnote66 Still, Japan has distinguished itself as a developer primarily of East-West links in Southeast Asia as well as maritime infrastructure, both chiefly aimed at making the region accessible to Japanese multinational companies.Footnote67 Currently, Japan stands out for its efforts to tie its connectivity support to its emerging Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy. Its regional connectivity vision is considerably more concrete than that of ASEAN, outlined in various policy guidance documents both in terms of geographic location of envisioned projects as well as implementation modalities.Footnote68 Many of the projects currently pursued by Japan's International Cooperation Agency JICA were part of the first connectivity master plan but are no longer part of the current one. Japan’s strong maritime focus, visible in its strong support for ports across the region with the aim of building a maritime corridorFootnote69 is not currently a priority of ASEANFootnote70 and therefore partly goes against the regional connectivity vision. While Japan is likely committed to ASEAN’s connectivity vision, questions remain over coherence.

Other external partners have added to this fundamental conflict on connectivity in the region, with South Korea’s New Southern PolicyFootnote71 and India’s Act East policyFootnote72 having potential effects on Southeast Asian connectivity. South Korea has so far remained sidelined from the conflict of the two large Northeast Asian countries but appears to be poised to play a larger role in regional connectivity, visible in its planned engagement in studies on infrastructure development at the national level and a US$ 200 billion infrastructure fund slated to launch in 2022.Footnote73 The Korean-led Connectivity Forum, established in 2013, potentially complicates the situation even further, adding another forum to the Chinese BRI summits and similar annual events hosted by Japan. India has likewise launched a US$ 1 billion financing line for potential ASEAN connectivity projects, which however appears to not have been used, potentially due to sub-optimal financing conditions.Footnote74 India’s flagship project remains the trilateral highway across Myanmar and Thailand, which it seeks to upgrade into an economic corridor.Footnote75

Western states have voiced concerns over getting involved with the connectivity agenda in the past but have mobilized significant political and financial capital to raise their ability to invest in Southeast Asian connectivity in 2018, highlighting increasing contestation within the policy area. In 2018, the EU has launched a new strategy titled “Connecting Europe and Asia – Building Blocks for an EU Strategy”.Footnote76 Establishing a European concept of “sustainable, comprehensive and rules-based connectivity,” the document makes several references to Asian investment needs and the ASEAN master plan. The document also explicitly ties the new EU strategy to the next edition of the multiannual financial framework (2021–2027), which sets the agenda for future EU external action funding. While the plan does not yet mention specific funding amounts, it proposes a resource mobilization mechanism built on the European Fund for Sustainable Development, which includes a US$ 70 billion fund to guarantee private sector and other investment.

Similar to the EU, the US did not appear to have a large appetite to engage with the connectivity agenda in early 2018, voicing a reluctance to launch projects in reaction to the master plan.Footnote77 Recently, however, the US has also set in motion reforms to increase its ability to engage with the connectivity agenda. With the adoption of the Better Utilization of Investment Leading to Development (BUILD) Act and the establishment of a new US development agency, the US International Development Finance Corporation (USIDFC) with a US$ 60 billion spending cap, a change has set in. The move has been interpreted as a direct response to China’s BRI and should enable the US to get more deeply involved in connectivity financing in Southeast Asia as well as other regions.Footnote78 Under current circumstances, questions remain over how ASEAN may reconcile the competitive visions of connectivity that have emerged in East Asia. It appears as if ASEAN has failed to provide much value as a regional convener, not forming any permanent institutions capable of hosting negotiations on East Asian connectivity. Its reliance on ad-hoc ASEAN+1 arrangements risks a splintering of negotiations, leading to incoherence in strategies as well as implementation of connectivity projects in Southeast Asia. ASEAN has also not acted as a regional leader. While its connectivity master plans lay out visions of regional infrastructure development, they do not elaborate on regional implementation mechanisms, hamstringing the organization and making it fully reliant on the terms of its external partners. Final judgment should be delayed, however, as ASEAN attempts to gain more leverage over its external partners by consolidating its regional agenda through new mechanisms such as its rolling priority project pipeline aimed at preparing concrete connectivity projects for external funding. The ASEAN Way is an awkward fit for connectivity, which relies on national-level implementation of distinctive projects, not consensus-based decision-making. Therefore, ASEAN may not even act as a regional convenience to its external partners. While engaging with ASEAN in the realm of connectivity may be a necessary step for Northeast Asian states eager to put their construction sectors to work abroad, as well as for Western governments not wanting to be left behind, this has also not led to ASEAN centrality. Unlike in trade, it is not yet apparent that external partners are willing to put ASEAN front and center in providing connectivity to the region, relying on their own forums and mechanisms to negotiate, select, and implement projects.

Of course, it is highly debatable whether any actor can be said to currently possess centrality in East Asian or Indo-Pacific connectivity. All initiatives mentioned in have their detractors, particularly the Chinese BRI as well as the Japanese PQI. Much more than in trade, connectivity is a clear case of multipolarity, with no apparent central actor outside of ASEAN. The recent moves by the EU, the US, South Korea, and India to get more involved in Southeast Asian connectivity may be seen as a boon to ASEAN, providing it with more options. On the other hand, they may also aggravate existing incoherence. ASEAN appears to remain committed to the pursuit of ASEAN+1 relationships in order to gain support for its connectivity projects. One may well ask whether this is counterproductive, as it opens up distinctive bargaining arenas between ASEAN and various dialogue partners instead of providing a venue for collective agenda setting. ASEAN member state representatives have suggested that in the future, APT may act as a venue to find common ground on connectivity with their Northeast Asian partners. The East Asia Summit could play a similar role with a wider set of external stakeholders. But, tellingly, the most recent ASEAN agreement with China contains no reference to partner coordination mechanismsFootnote79 , nor do any of the other plans of action of ASEAN’s external partners. Under these circumstances, we must strongly question the bases as well as the prospects for ASEAN centrality to resist external organizational pressures in connectivity.

Table 2. Competitive connectivity initiatives by ASEAN’s external partners (source: author’s own elaboration).

5. Conclusion

Assessments arguing that ASEAN centrality is under threat are nothing new. This analysis, however, has provided more substantial explanations of how centrality has been threatened and how previous and current assessments of centrality fall short of reality. The analysis of ASEAN’s centrality in trade and connectivity highlight two different aspects of the concept that remain underinvestigated. In trade, it has become clear that developments in ASEAN’s environment pose challenges to the organization. While ASEAN centrality in trade may have been fact until the early 2010s, ties between other East Asian states have caught up, creating a complex network of trade relations in East Asia that no longer relies on ASEAN as a central node. An analysis of ASEAN’s substantial role as a central actor in trade highlights that ASEAN leadership in trade and the provision of the ASEAN Way is likely becoming less useful to other East Asian partners, threatening its central role in forums.

In connectivity, the limitations of a technical view of ASEAN centrality come into view. Analysts need to be more mindful of the ties that bind ASEAN to its external environment. In connectivity, the organization may be at the center of things, but it is faced with contestation of its connectivity agenda, with actors utilizing bilateral relationships as a conduit to exercise power over ASEAN. ASEAN’s role as a regional leader through the provision of an agenda for connectivity should therefore be questioned. The organization has also failed to create adequate mechanisms to manage its external relations in connectivity, which calls into question its ability to act as a regional convener. Overall, while ASEAN remains central in connectivity, it is so in name only, and not in substance.

Centrality, just like power, may be a transient feature of international politics. Just as centrality can be gained, it can also be lost. Multiple studies have emphasized pathways for ASEAN to gain more centrality, most notably deepened commitment to its own economic integration agenda, the ASEAN Economic Community. This remains the way for ASEAN to increase its centrality in trade: by continuing its trajectory toward an economically integrated region, attaining more coherence in the process. In connectivity, centrality would likely be strengthened by way of creating regional resource mobilization mechanisms that rely less on external funds and more on intra-ASEAN sources of finance. Through an increase in self-reliance and internal coherence, ASEAN may strengthen its position in its external environment considerably, across policy areas.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lukas Maximilian Mueller

Lukas Maximilian Mueller is a research associate at the Chair of International Politics at the University of Freiburg, Germany. His work mainly concerns regional integration and the external relations of regional organizations in Southeast Asia as well as in West Africa. In addition, he has worked as a consultant for the Asia-Europe Foundation, providing capacity building on national SDG implementation in the CLMV countries. His research interests include comparative regionalism, interregionalism, EU foreign policy, and sustainable development.

Notes

1 Caballero-Anthony, “Understanding ASEAN’s Centrality.”

2 Beeson, “Living with Giants.”

3 Acharya, Constructing a Security Community in Southeast Asia.

4 Goh, “Southeast Asian Strategies Toward the Great Powers.”

5 Leifer, “Extending ASEAN’s model”; and Suzuki, “East Asian Cooperation Through Conference Diplomacy.”

6 See note 1 above.

7 Beeson, “Living with Giants”; and Jones and Jenne, “Weak States’ Regionalism.”

8 Acharya, Constructing a Security Community in Southeast Asia; Jones, “Still in the ‘Drivers’ Seat’, but for How Long?”; Jones and Jenne, “Weak States’ Regionalism”; and Le Thu, “China’s Dual Strategy of Coercion and Inducement Towards ASEAN.”

9 Kraft, “Great Power Dynamics and the Waning of ASEAN Centrality in Regional Security”; and Kuik, “Keeping the Balance.”

10 Yoshimatsu, “ASEAN and Evolving Power Relations in East Asia.”

11 Jones and Jenne, “Weak States’ Regionalism,” 234.

12 Acharya, “The Myth of ASEAN Centrality?” 273.

13 See note 1 above.

14 Ibid., 573.

15 Ibid.

16 Tan, “Rethinking ‘ASEAN Centrality’ in the Regional Governance of East Asia.”

17 Ibid., 726–730.

18 Ibid., 723–726, Ibid., 731–733.

19 Ibid., 733–735.

20 Acharya, “The Myth of ASEAN Centrality?”.

21 Caballero-Anthony, “Understanding ASEAN’s Centrality,” 566.

22 Acharya, “Competing Communities.”

23 Wilson, “Mega-Regional Trade Deals in the Asia-Pacific.”

24 Ibid.

25 Hsieh, “The RCEP, New Asian Regionalism and the Global South.”

26 Oba, “TPP, RCEP, and FTAAP”; and Hsieh, “The RCEP, New Asian Regionalism and the Global South.”

27 Ibid.

28 Oba, “TPP, RCEP, and FTAAP.”

29 Wang, “The RCEP Initiative and ASEAN Centrality.”

30 See note 28 above.

31 ASEAN Member State Official, Interview by author, Jakarta, April 18 2019.

32 Ibid.

33 Ye, “China and Competing Cooperation in Asia-Pacific.”

34 See note 28 above.

35 Fukunaga and Isono, “Taking ASEAN+ 1 FTAs Towards the RCEP.”

36 ASEAN Secretariat Official, Interview by author, Jakarta, February 27 2019.

37 See note 29 above.

38 See note 23 above.

39 See note 28 above.

40 Pomfret, “ASEAN’s New Frontiers.”

41 Fukunaga, “ASEAN’s Leadership in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership”.

42 ASEAN Secretariat Official, Interview by author, Jakarta, February 27 2019; and Hsieh, “The RCEP, New Asian Regionalism and the Global South.”

43 Wang, “The RCEP Initiative and ASEAN Centrality,” 130.

44 See note 31 above.

45 See note 31 above.

46 Chinese Ministry of Commerce. “The 15th Round of Negotiations of China-Japan-ROK FTA Held in Tokyo.”

47 See note 25 above.

48 Ibid.

49 Müller, “Governing Regional Connectivity in Southeast Asia.”

50 Asian Development Bank, “Meeting Asia’s Infrastructure Needs.”

51 See note 49 above.

52 Malaysian Ministry of Finance, “ASEAN Infrastructure Fund (AIF).”

53 Vejjajiva, “Statement by H.E. Abhisit Vejjajiva.”

54 Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Thailand’s Proposal on the ‘3Cs’ for ASEAN.”

55 ASEAN Secretariat, “Summary Record of the ASEAN Connectivity Coordinating Committee (ACCC) Consultations.”

56 ASEAN External Partner, Interview by author, Jakarta, February 13 2019.

57 ASEAN External Partner, Interview by author, Jakarta, February 16 2018.

58 He, “Institutional Balancing and International Relations Theory.”

59 See note 49 above.

60 ASEAN Secretariat, “Summary Record of the ASEAN Connectivity Coordinating Committee (ACCC) Consultations.”; ASEAN External Partner, Interview by author, Jakarta, February 13 2018; ASEAN External Partner, Interview by author, Jakarta, March 5 2018; and Australian Aid, “Our Program AADCP II.”

61 Goh and Reilly, “How China’s Belt and Road Builds Connections.”

62 Kuik, Li and Ling, “The Institutional Foundations and Features of China-ASEAN Connectivity.”

63 ASEAN Secretariat, “ASEAN-China Strategic Partnership Vision 2030.”

64 Rana and Ji, “China Is Paving a Belt and Road 2.0.”

65 Goh and Reilly, “How China’s Belt and Road Builds Connections”; and Rana and Ji, “China Is Paving a Belt and Road 2.0.”

66 Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Japan’s Assistance to ASEAN Connectivity in Line with MPAC 2025.”

67 Hong, “Chinese and Japanese Infrastructure Investment in Southeast Asia.”

68 ASEAN External Partner, Interview by author, Jakarta, May 8 2018; and Sonoura, “Japan’s Initiatives for Promoting ‘Quality Infrastructure Investment’.”

69 Sonoura, “Japan’s Initiatives for Promoting ‘Quality Infrastructure Investment’.”

70 See note 55 above.

71 The Jakarta Post, “ASEAN, South Korea to boost regional connectivity.”

72 The Diplomat, “ASEAN and India Converge on Connectivity.”

73 The Diplomat, “South Korea Eyes ASEAN’s Port Projects Amid Domestic Slowdown.”

74 See note 55 above.

75 Ibid.

76 European Commission, Connecting Europe and Asia.

77 See note 57 above.

78 CSIS, “The BUILD Act Has Passed.”

79 See note 63 above.

Bibliography

- Acharya, A. “Competing Communities: What the Australian and Japanese Ideas Mean for Asia’s Regional Architecture.” Pacnet, no. 70 (2009).

- Acharya, A. Constructing a Security Community in Southeast Asia: ASEAN and the Problem of Regional Order. Abingdon: Routledge, 2014.

- Acharya, A. “The Myth of ASEAN Centrality?” Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs 39, no. 2 (2017): 273–279.

- ASEAN Secretariat. ASEAN-China Strategic Partnership Vision 2030. ASEAN Secretariat, Jakarta, 2018.

- ASEAN Secretariat. Summary Record of the ASEAN Connectivity Coordinating Committee (ACCC) Consultations with Dialogue Partners and Other External Partners on Connectivity. ASEAN Secretariat, Singapore, September 7, 2018.

- Asian Development Bank. Meeting Asia’s Infrastructure Needs. Asian Development Bank, Manila, 2017.

- Australian Aid. “Our Program AADCP II.” Accessed February 16, 2019. http://aadcp2.org/our-program/

- Beeson, M. “Living with Giants: ASEAN and the Evolution of Asian Regionalism.” Trans: Trans -regional and -national Studies of Southeast Asia 1, no. 2 (2013): 303–322. doi:10.1017/trn.2013.8.

- Caballero-Anthony, M. “Understanding ASEAN’s Centrality: Bases and Prospects in an Evolving Regional Architecture.” The Pacific Review 27, no. 4 (2014): 563–584. doi:10.1080/09512748.2014.924227.

- Chinese Ministry of Commerce. “The 15th Round of Negotiations of China-Japan-ROK FTA Held in Tokyo.” Accessed September 9, 2019. http://fta.mofcom.gov.cn/enarticle/chinarihen/chinarihennews/201904/40325_1.html

- CSIS. “The BUILD Act Has Passed: What’s Next?” Accessed November 25, 2018. https://www.csis.org/analysis/build-act-has-passed-whats-next

- Desai, S. 2017. “ASEAN and India Converge on Connectivity.” The Diplomat, December 19. Accessed December 30, 2018. https://thediplomat.com/2017/12/asean-and-india-converge-on-connectivity/.

- European Commission. Connecting Europe and Asia - Building blocks for an EU Strategy: Joint Communication to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions and the European Investment Bank. Brussels, 2018.

- Fukunaga, Y. “ASEAN’s Leadership in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.” Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 2, no. 1 (2015): 103–115. doi:10.1002/app5.59.

- Fukunaga, Y., and I. Isono. “Taking ASEAN+ 1 FTAs Towards the RCEP: A Mapping Study.” ERIA Discussion Paper Series 2, 2013, 1–37.

- Goh, E. “Southeast Asian Strategies toward the Great Powers: Still Hedging after All These Years?” The Asan Forum, 2016. http://www.theasanforum.org/southeast-asian-strategies-toward-the-great-powers-still-hedging-after-all-these-years/.

- Goh, E., and J. Reilly. “How China’s Belt and Road Builds Connections.” Accessed May 23, 2019. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2018/01/04/how-chinas-belt-and-road-builds-connections/.

- Handayani, P. 2018. “ASEAN, South Korea to Boost Regional Connectivity.” The Jakarta Post, December 6. Accessed December 30, 2018. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2018/12/06/asean-south-korea-boost-regional-connectivity.html.

- He, K. “Institutional Balancing and International Relations Theory: Economic Interdependence and Balance of Power Strategies in Southeast Asia.” European Journal of International Relations 14, no. 3 (2008): 489–518. doi:10.1177/1354066108092310.

- Hong, Z. “Chinese and Japanese Infrastructure Investment in Southeast Asia: From Rivalry to Cooperation?” IDE Discussion Paper, No. 689, 2018.

- Hsieh, P. L. “The RCEP, New Asian Regionalism and the Global South.” MegaReg Series 4, New York: New York University School of Law, December 12, 2017.

- Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “Japan’s Assistance to ASEAN Connectivity in Line with MPAC 2025: Presentation by Kazuo Sunaga, Ambassador of Japan to ASEAN.” 2016. https://www.asean.emb-japan.go.jp/documents/20161102.pdf.

- Jones, D. M., and N. Jenne. “Weak States’ Regionalism: ASEAN and the Limits of Security Cooperation in Pacific Asia.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 16, no. 2 (2016): 209–240. doi:10.1093/irap/lcv015.

- Jones, L. “Still in the “Drivers’ seat,” but for How Long? ASEAN’s Capacity for Leadership in East-Asian International Relations.” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 29, no. 3 (2010): 95–113. doi:10.1177/186810341002900305.

- Kang, T.-J. 2019. “South Korea Eyes ASEAN’s Port Projects Amid Domestic Slowdown.” The Diplomat, February 16. Accessed June 23, 2019. https://thediplomat.com/2019/02/south-korea-eyes-aseans-port-projects-amid-domestic-slowdown/.

- Kraft, H. J. “Great Power Dynamics and the Waning of ASEAN Centrality in Regional Security.” Asian Politics & Policy 9, no. 4 (2017): 597–612. doi:10.1111/aspp.12350.

- Kuik, C.-C. “Keeping the Balance: Power Transitions Threaten ASEAN’s Hedging Role.” East Asia Forum Quarterly 10, no. 2 (2018): 22–23.

- Kuik, C.-C., L. Ran, and S. N. Ling. “The Institutional Foundations and Features of China-ASEAN Connectivity.” In Southeast Asia and China: A Contest in Mutual Socialization, edited by L. Dittmer and C. B. Ngeow, 247–278. Singapore: World Scientific, 2017.

- Le Thu, H. “China’s Dual Strategy of Coercion and Inducement Towards ASEAN.” The Pacific Review 35, no. 4 (2018): 1–17.

- Leifer, M. “The ASEAN Regional Forum: Extending ASEAN’s Model of Regional Security.” The Adelphi Papers, no. 302 (1996): 21–30.

- Malaysian Ministry of Finance. Presentation: ASEAN Infrastructure Fund (AIF). Bangkok, November 25, 2015. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/5b%20-%20ASEAN%20Infrastructure%20Fund.pdf.

- Müller, L. M. “Governing Regional Connectivity in Southeast Asia - the Role of the ASEAN Secretariat and ASEAN’s External Partners.” Occasional Paper, no. 42, 2018.

- Oba, M. “TPP, RCEP, and FTAAP: Mulitlayered Regional Economic Integration and International Relations.” Asia-Pacific Review 23, no. 1 (2016): 100–114. doi:10.1080/13439006.2016.1195957.

- Pomfret, R. “ASEAN’s New Frontiers: Integrating the Newest Members into the ASEAN Economic Community.” Asian Economic Policy Review 8, no. 1 (2013): 25–41. doi:10.1111/aepr.12000.

- Rana, P. B., and J. Xianbai “China Is Paving a Belt and Road 2.0.” Accessed May 23, 2019. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2019/05/21/china-is-paving-a-belt-and-road-2-0/.

- Sonoura, K. “Japan’s Initiatives for Promoting “Quality Infrastructure investment”.” New York City, September 19, 2017. https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/000291344.pdf.

- Suzuki, S. “East Asian Cooperation through Conference Diplomacy: Institutional Aspects of the ASEAN Plus Three (APT) Framework.” IDE APEC Study Center Working Paper Series No.7, March 2004. doi:10.1094/PDIS.2004.88.1.84A

- Tan, S. S. “Rethinking “ASEAN centrality” in the Regional Governance of East Asia.” The Singapore Economic Review 62, no. 03 (2017): 721–740. doi:10.1142/S0217590818400076.

- Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “Thailand’s Proposal on the “3cs” for ASEAN.” Accessed January 3, 2019. https://www.thaiembassy.sg/press_media/news-highlights/thailand%E2%80%99s-proposal-on-the-%E2%80%9C3cs%E2%80%9D-for-asean.

- Vejjajiva, A. “Statement by H.E. Abhisit Vejjajiva, Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Thailand, at the Opening Ceremony of the 15th ASEAN Summit and Related Summits.” Accessed January 3, 2019. https://asean.org/?static_post=statement-by-he-abhisit-vejjajiva-prime-minister-of-the-kingdom-of-thailand-at-the-opening-ceremony-of-the-15th-asean-summit-and-related-summits.

- Wang, Y. “The RCEP Initiative and ASEAN Centrality.” China International Studies, no. 42 (2013): 119–132.

- Wilson, J. D. “Mega-Regional Trade Deals in the Asia-Pacific: Choosing between the TPP and RCEP?” Journal of Contemporary Asia 45, no. 2 (2015): 345–353. doi:10.1080/00472336.2014.956138.

- Ye, M. “China and Competing Cooperation in Asia-Pacific: TPP, RCEP, and the New Silk Road.” Asian Security 11, no. 3 (2015): 206–224. doi:10.1080/14799855.2015.1109509.

- Yoshimatsu, H. “ASEAN and Evolving Power Relations in East Asia: Strategies and Constraints.” Contemporary Politics 18, no. 4 (2012): 400–415.