?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Scholars generally agree that regionalization and regionalism are different phenomena; however, unresolved arguments remain as to whether there is a causal relationship between the two. In particular, whether or not regionalization promotes regionalism is a subject of debate. This paper aims to comprehensively clarify and explain the relationship between regionalization as embodied in trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) and regionalism as characterized by preferential trade agreements (PTAs) using event history analyses of East Asian economic data from 1985 to 2018. The paper concludes that although a positive and significant relationship exists between FDI and some types of PTAs, trade has no relationship with the latter. This conclusion challenges extant literature, which has argued that an increase in PTAs in East Asia (the outcome of regionalism) is the consequence of economic interdependence (regionalization). Moreover, these findings indicate that political factors such as territorial disputes and joint democracy negatively affect certain types of PTAs. This result is contrary to the conventional wisdom that predicts increased cooperation and lower tariffs between democracies and therefore suggests further investigations of the determinants of PTAs.

1. Introduction

The concept of East Asian regionalism has attracted considerable attention since the end of the 1990s, as a number of policy makers, academics, and business executives have discussed the possibility of the creation of a regional institutional framework.Footnote1 In this context, as I will argue in the next section, there is mutual agreement that “regionalization” and “regionalism” are distinct phenomena; however, there are unresolved arguments as to whether there is a causal relationship between them. Whereas one perspective emphasizes that regionalization automatically promotes regionalism, others argue that regionalization is not necessarily a catalyst for regionalism. Due to the complexities of the relationship, some scholars have given up attempting to untangle this problem. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to clarify and explain the relationship between regionalization and regionalism via the use of statistical analyses of several variables related to trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) and preferential trade agreements (PTAs) in East Asian countries.Footnote2 Since a number of scholars have probed that regional trade arrangements (the outcome of regionalism) lead to regionalization (increasing trade), this paper focuses on the reversed vector to investigate whether regionalization promotes regionalism. Moreover, this research also attempts to discover other factors that promoted East Asian regionalism.

2. Existing research on regionalization and regionalism

Since the mid-1990s, a certain number of economics and international relations analysts have emphasized the necessity of distinguishing between regionalization and regionalism as analytical constructs and clarifying the relationship between the two phenomena.Footnote3 Regionalization is defined as an increase in the cross-border flow of capital, goods, ideas, and people within a specific geographical area. Regionalization can be called a spontaneous, bottom-up process in that its core players are firms or individuals and it develops through societally driven processes deriving from markets, private trade, and investment flows, none of which is strictly controlled by governments. The development of regionalization means an increase in the number of regional economic transactions such as people, trade, and FDI. In contrast, regionalism is defined as a political will (hence ism is attached as a suffix) to create a formal arrangement among states on a geographically restricted basis. Since its main participants are governments, it can be expressed as an artificial, top-down process. “Regionalism in progress” refers to the agreement of regionally close governments to establish formal institutions such as the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation, the East Asia Summit, or bilateral and multilateral PTAs in order to cooperate with each other on various issues.

Few scholars have opposed the idea that whereas regionalization in East Asia has been developing since the mid-1980s (particularly after the historic 1985 Plaza Accord), regionalism mainly began to be promoted later, around the time of the Asian financial crisis of 1997.Footnote4 From this time onward, scholars have wrestled with the question of how these phenomena interact. There is a widely shared view among some analysts that the existence of trade institutions (regionalism) leads to growth in trade, that is, regionalization is a demonstration of economic regionalism.Footnote5 According to this perspective, as a result of decreases in tariffs and non-tariff barriers between two or more countries that have finalized trade arrangements, a so-called trade creating effect would cause an increase of commerce among members. For example, the influential empirical work by Baier and Bergstrand demonstrated that on average, a PTA approximately doubles two members’ bilateral trade after 10 years.Footnote6 In Asia, according to Kawai and Wignaraja’s research using a CGE (computable general equilibrium) model, the establishment of East Asian-wide PTAs (i.e., the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)+3, or ASEAN+6) would result in increased economic growth for each member.Footnote7 Moreover, some analysts have argued that not only trade but also FDI would increase if trade agreements were concluded. Since international institutions such as PTAs enable governments to make more credible commitments to a liberal economic policy and prevent even developing countries from making arbitrary interventions such as regulation, taxation, or tariff increases, foreign investors can safely make investments in countries joining regional trade arrangements.Footnote8 All of these views seem to be based on a conventional international relations thesis – institutions lower transaction costs, reduce uncertainty, monitor compliance, and enhance opportunities for more cooperation.Footnote9

However, the economic effect of some individual PTAs in East Asia has not been so clear, and there are cases in which participation in a regional trade arrangement does not necessarily lead to an increase in economic interaction in East Asia. For example, Ando concluded that the Japan-Singapore EPA (Economic Partnership Agreement) has had little impact on trade.Footnote10 Similarly, Dent inferred that the expected annual trade and investment liberalization “gains” accruing from the Singapore-Peru PTA are possibly less than the actual administrative cost of negotiating and implementing the agreement itself.Footnote11 Although somewhat beyond the scope of this paper, the reason states attempt to conclude PTAs despite their expected low economic effects is notable and merits further research.

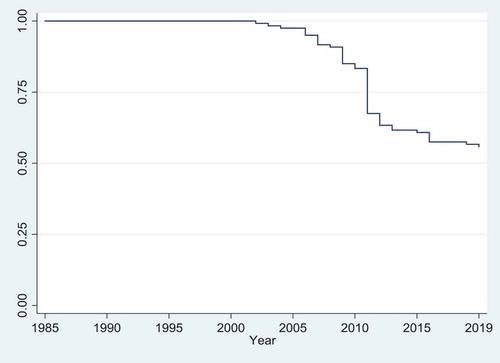

Now let us consider the reversed vector – that is, whether increased regional economic interdependence (regionalization) encourages involved governments to conclude or join economic arrangements such as PTAs (regionalism). The number of PTAs has been increasing worldwide since the early 1990s, and this tendency is particularly remarkable in East Asia after 2000 (). Can the emerging proliferation of PTAs be explained by enlarged economic interdependence in the region?

Figure 1. Number of PTAs since 1948 (Source: WTO)Footnote12

In fact, there are two competing views on this issue. The dominant view asserts that regionalization is an inevitable driving force for regionalism. For example, Kawai argued that “[the] most fundamental rationale behind the emergence of recent economic regionalism is the deepening of regional economic interdependence inFootnote12. East Asia.”Footnote13 Similarly, Munakata emphasized that the intensity of economic interaction contributes substance and depth and thereby a forms basis for institutionalized intergovernmental cooperation, including preferential trade agreements.Footnote14 Lincoln expressed a negative view as to the necessity and economic effect of East Asian regional trade arrangements, arguing that intra-regional trade has been decreasing rather than increasing and identifies Japan’s economic decline as the main factor in the shrinkage.Footnote15 This logic derives its meaning from the assumption that growth in regional economic interaction drives regionalism. Progressing from a simple trade relationship, Manger proposed that FDI by multinational firms is a key driving force behind the growth of North–South (developed–developing countries) PTAs.Footnote16 Particularly, the greater the volume of FDI between two countries, the more likely they are to conclude a PTA due to lobbying from their respective multinational firms, in particular, those conducting service in trade. Based on this hypothesis, Manger examined cases such as the North American Free Trade Agreement, the Japan–Mexico FTA and the Japan–Thailand FTA in detail, concluding that the greater the amount of vertical intra-industry trade among country pairs, the more likely those governments are to sign PTAs.Footnote17

In contrast to the above view, some scholars have become skeptical about this simple, linear relationship, particularly during the last decade. Ravenhill has shared Lincoln’s view in insisting that regionalization in East Asia has indeed been decreasing if we consider low shares in trade, which show the region’s changing share of global commerce via the trade intensity index and are not consistent with the widely shared view that both regionalism and regionalization in East Asia have been increasing since the late 1980s.Footnote18 Jetschke and Katada also pointed out what they consider the puzzling high levels of regionalization as compared to low levels of regionalism in the region, and Solís similarly argued that most of the current bilateral PTAs in East Asia are between small trading partners.Footnote19 Twenty years ago, Haggard even suggested the possibility that regionalization may prevent regionalism, stating that “despite – and arguably because of – the extremely rapid growth of trade and investment, there has not been strong demand within Asia for greater policy coordination.”Footnote20

Although the existing research presents some useful arguments on both sides of the debate, they do not comprehensively examine the relationship between the two phenomena. If a conclusion is derived from a few cases, any argument is possible. For example, to insist that an increase in economic interdependence was not a factor to promote PTA formation, we could use cases that suit the hypothesis, for instance, no agreements between China, Japan, and South Korea. To challenge this view, we could select opposite cases that can easily disprove the argument. Consequently, the argument that regionalization promotes regionalism is merely a policy recommendation with insufficient empirical evidence (and makes no effort to probe its own arguments). The argument that refutes simple linear relations between regionalization and regionalism has a similar problem. For example, Ravenhill pointed out the odd relationship (from the perspective of existing studies) whereby countries that have experienced trade increases with China while also eschewing PTAs with it as an illustration of his arguments.Footnote21 However, his illustration was drawn from a small number of cases and outcomes, thus suggesting that possibility of sample selection bias. Moreover, Ravenhill’s main argument is to reject increased economic interdependence (regionalization) in East Asia, not the relationship between regionalization and regionalism itself.Footnote22 Similarly, although the argument that an increase in FDI brings about PTAs is interesting and persuasive, case studies alone do not reveal the whole picture,Footnote23 and thus, the influence of regionalization over regionalism has not been fully examined. It is natural for some studies to avoid attempting to clarify causes versus consequences and instead simply describe these relations as a “mutual reinforcement process”.Footnote24 The aim of this paper, therefore, is to settle the dispute by comprehensively examining the relations between regionalization (as embodied by trade and FDI) and regionalism (as represented by PTAs) using statistical analyses of East Asian trade data from 1985 to 2018. Furthermore, this study also attempts to provide one of the factors that affect East Asian regionalism.

3. Types of PTAs and regionalization

3.1. Three types of PTAs as dependent variables

In light of the complex PTA network in the East Asian region, which sometimes called the “noodle bowl,” some caution is needed to analyze this theme. First, three types of trade frameworks exist defined by the WTO in the East Asian region, namely FTAs, EIAs (economic integration agreements), and PSAs (partial scope agreements).Footnote25 As the name suggests, a FTA is a free trade agreement for goods, whereas an EIA is a free trade agreement for service, as defined in Article V of General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). A PSA is an agreement that only covers specific products and is not defined or referred to in the WTO. PSA includes the Global System of Trade, which was joined by Myanmar and Indonesia in 1989; however, the fact that it is not referred to by the WTO shows that this agreement is not strictly binding on members. Therefore, this study focuses on FTAs and EIAs, which restrict the discretion of national trade policies.

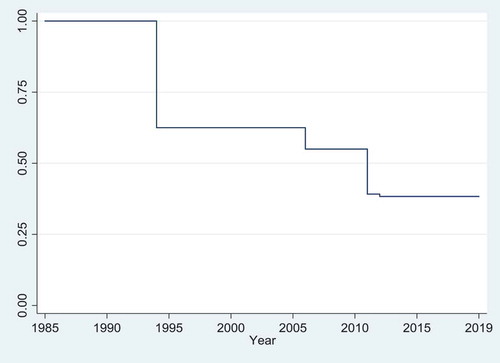

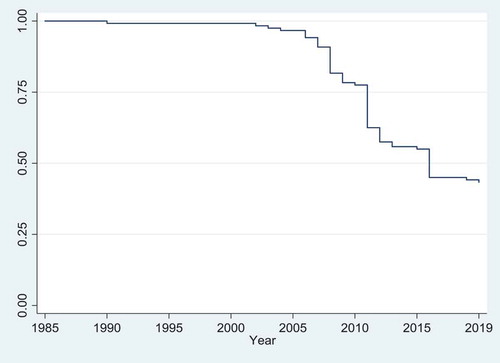

Second, two types of FTAs are recognized by the WTO: those falling under Article XXIV of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and those falling under the enabling clause. The two major requirements of the former are that (1) duties and other restrictive regulations on commerce should be eliminated on “substantially all trade” in products between members, and (2) external tariffs or other regulations on commerce must not be raised above or be more restrictive than those prior to the PTA’s formation. In contrast, the enabling clause does not impose these conditions. Whereas PTAs among developing countries (such as ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA)) were established under the enabling clause, developed countries such as Japan and Singapore are not permitted to establish PTAs under this clause. A key point regarding Article XXIV of GATT concerns the range of “substantially all trade.” The word “substantially” indicates that some allowances can be made; however, the extent of such latitude has been a controversial issue with no clear resolution. In general, as the Japanese government once suggested, tariff elimination needs to cover at least 90% of trade.Footnote26 In contrast, this requirement is not necessary under the enabling clause. Therefore, concluding PTAs among developing countries is considered to be relatively easier than among developed nations. That AFTA was established in 1992, which is rather early for East Asia, reflects the nature of the enabling clause.Footnote27 Therefore, this study distinguishes between the enabling clause and GATT XXIV FTAs.Footnote28 Third, in East Asia, most FTAs (whether Article XXIV or enabling clause) and EIA are concluded simultaneously. The only exceptions are AFTA in 1993 and Japan-ASEA FTA in 2008. Therefore, FTAs can be characterized as a subset of EIAs. – show the matrix of East Asian PTAs.

3.2. Regionalization and regionalism in East Asia reconsidered

Does regionalization (increase in trade and FDI) promote regionalism? To answer that question, it is necessary to consider the impact of the trade and FDI when a PTA is signed. A high degree of trade means that each country is also economically large, which leads to an increase in the number of social and economic actors – veto players – who have a vested interest in foreign trade and therefore tend to make policy change difficult.Footnote29 More specifically, the higher the level of trade, the more likely industries that compete with imports will be damaged through their increase. Thus, pressure from such sectors may prevent governments from promoting PTAs.Footnote30 In East Asia, Saxer shed light on the deep negative domestic impact that brought massive resistance from societies in the South Korea after concluding the Korea-United States FTA.Footnote31 Jones proposed that even in ASEAN, where economic integration is considered to be the highest in the region especially after the new millennium, social, and political forces have become hurdles hindering the smooth establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community in East Asian.Footnote32 In contrast, export firms have relatively less incentive to lobby for liberalization if trade volumes are sufficiently large, and generally only push hard for their governments to conclude PTAs when they expect significant losses in the absence of such agreements.Footnote33 The main purpose of trade arrangements is to increase trade; however, as regional economic ties are already strong in East Asia (de-facto integration), the incentives for policy makers and business elites to create formal arrangements should be weak. Why do governments need to conclude new agreements when economic transactions are already increasing sufficiently? Consequently, large trading partners should have fewer PTAs than small ones. This situation can be observed in all three types of PTAs. The first hypothesis, which is consistent with the recent literature, is as follows.

H1: An increase in trade does not promote regionalism in East Asia.

Conversely, the relationship between FDI and PTAs is not as direct as that between trade and PTAs. Nonetheless, multinational firms that have FDI in a host country have the incentive to require their governments to conclude PTAs with the host country. First, as Manger argued, if a firm has established bases overseas through FDI, it is the first mover’s interest to shut out late-comer competitors by demanding to conclude PTAs between their home country and the host country.Footnote34 Second, investment chapters have been one of the features of PTAs since the 2000s. If a multinational company in a home country has already managed business in a host country through FDI and there is no investment agreement between the two, then that company’s government will seek to create a better investment environment and legal protections for its own firms by signing PTAs with the host country. Even if a bilateral investment treaty has already been concluded between the home and host countries, the latter government should demand the same status as other countries by updating it in a PTA. For example, Keidanren, the largest economic organization in Japan, already proposed a policy proposal “establishing international investment rules and improving the domestic investment environment” as of 2002, in which it insisted on the conclusion of bilateral and/or regional agreements.Footnote35 Such domestic demands are not negligible for the government, thus leading to the finding of the quantitative analysis that the greater the degree of FDI between the two countries, the more likely they are to conclude a PTA. The second hypothesis is as follows.

H2a: An increase in FDI promotes GATT XXIV FTAs and EIA in East Asia.

However, the above explanations are not applied to the relations between FDI and the enabling clause FTAs. Since FDI basically flows from developed to developing countries, FDI among the mainly developing enabling clause partners is not large. Therefore, multinational firms (if they exist) in developing countries do not have an incentive to pressure their governments to form enabling clause FTAs. In particular, when AFTA was entered into force in 1993, investment among ASEAN countries was very small relative to that to non-ASEAN countries.Footnote36 Thus, the following hypothesis was derived.

H2b: An increase in the amount of FDI does not promote enabling clause FTAs.

3.3. Other factors to promote PTAs

Prior to conducting the statistical analysis, I considered other factors that influence PTAs, including why and when governments choose to enter PTAs with other governments. Scholars have attempted to answer this question. The most well-known research on this topic is a series of studies by Mansfield and Milner.Footnote37 They argue that democracies are more likely to pursue trade agreements, though this effect is lessened by the number of veto players. Chase presented that the trade preferences of domestic actors served as a primary dependent variable to focus on scale economies.Footnote38 This work argued that producers who benefit more from an increase in plant size are likely to support trade blocks because they will gain higher profit if they sell abroad rather than stay in the domestic market. On the contrary, firms who compete with imports and do not benefit from economies of scale probably oppose opening their domestic markets. Baldwin and Jaimovich and Baccini and Dür have argued that regionalism exerts a “domino” or “contagious” effect and have attempted to test and prove this hypothesis statistically.Footnote39

Apart from the aforementioned factors, this study proposes a territorial problem between the two countries as a factor that affects PTAs. Territorial disputes are likely to cause deterioration in bilateral relations and remain the greatest cause of militarized interstate disputes (MID).Footnote40 In particular, for a government in democratic states that may lose its power because of an election, the rapid establishment of a PTA would be difficult with a country that has a territorial dispute. Specifically, East Asia has more territorial disputes than any other region in the world.Footnote41 Thus, the third hypothesis is proposed.

H3: Territorial disputes negatively affect PTA formation.

4. Method and variables

The dyad year is the unit of analysis whereby the dyad comprises cross-country data. East Asia is defined herein as ASEAN+6 – i.e., countries that are members of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Therefore, the dyad is a pair of 16 countries, and the sample period is 1985–2018. The statistical method employed in this study is called “event history analysis” or “survival analysis.” Since this paper aims to estimate the influence of regionalization over regionalism (PTAs), the dependent variable is a binary outcome denoting whether or not a PTA exists – the variable equals one if a PTA exists between two states and zero otherwise. Survival analysis was deemed to be the most appropriate statistical method for the purposes of this paper,Footnote42 as a normal maximum likelihood method such as logistic regression raises the problem of endogeneity – that is, if two countries concluded a PTA in 2005, for instance, the amount of trade after 2006 would be affected by the agreement, which is the dependent variable. Since this paper analyzes the influence of economic factors over PTAs and not vice versa, the analysis should end once partner countries enforce a PTA. Therefore, the finalization of a PTA is read as the occurrence of the event (this is also called “failure”) and its probability estimated. Data for any two country pairs that have not signed PTAs, such as China-Japan, are called “right censored” data. In that sense, the sample is unbalanced panel data. Equation (1) presents the formula of the Cox proportional hazards model.

where is the hazard function of subject i,

is the baseline hazard, and

represents the covariates. This model investigates the effect of covariates on a subject’s survival time.

4.1. Dependent variable

PTA data as a binary dependent variable are drawn from the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) website.Footnote43 – above and – below show various features in East Asian Regionalism.Footnote44 First, the number of PTAs of each type is different: as of July 2019, there are 30 (54 pairs) GATT Article XXIV FTAs, six (76 pairs) enabling clause FTAs, and 32 (69 pairs) EIAs in East Asia. Second, nearly all of the enabling clause FTAs involve countries within ASEAN, with the exceptions of the India-Malaysia FTAs. Third, combing three types of PTAs, a substantial proportion of 115 PTAs (out of 120 possible pairs;Footnote45 ) have already been concluded, thus indicating that bilateral and multilateral PTAs networks have been stretching around the region.Footnote46 Fourth, there are some variations among individual countries: whereas Singapore has PTAs with all of the countries in the region, India seems too hesitant to move forward in a similar manner. Fifth, except for the Australia–New Zealand FTA (concluded in 1983), all GATT XXIV FTAs were formed after 2000. Sixth, some countries have finalized PTAs more than twice. For example, New Zealand and Singapore concluded FTAs (or AEIs) four times (at first bilaterally, and then as members of the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership (TPP), ASEAN-Australia New Zealand FTA, and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)). Considering the endogeneity mentioned above, when coding dependent variables, if a country has PTAs with the same country more than twice through bilateral or multilateral negotiations, I have chosen the earlier agreement.

4.2. Independent variables

The most important variable is an enlarged economic interdependence (regionalization), which I measured as the volume of trade and FDI between two countries.Footnote47 If the argument that regionalization leads to regionalism is correct, then a higher amount of trade and FDI will bring a greater likelihood that a pair of countries will conclude a PTA. To test this, I introduced the volume of trade (imports plus exports, expressed in thousands of US dollars) between two countries as an independent variable named TRADE.Footnote48 Trade data were taken from the IMF Direction of Trade Statistics database.Footnote49 Moreover, not only nominal value but also shared value (the amount of trade between country j and country i divided by the sum of the total amount of j’s and i’s worldwide trade) is taken as an independent variable, named TRADEshare, thus reflecting the idea that regionalization occurs in comparison with globalization.

Along with trade, I examined the relationship between FDI and PTAs. Since no standardized data set of FDI exists (particularly in the case of developing countries), I calculated the stocks (positions) of FDI between two countries using the following methods. (1) Data from Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) members (such as Australia and Japan) were collected from the OECD website,Footnote50 whereas those for developing countries were taken from a data book published by Japan’s Institute for International Trade and Investment (IITI).Footnote51 (2) If only flow data existed, I summed up those data from the earliest period available. (3) The unit is billions of US dollars; in cases when only local currency data were available, amounts was exchanged into US dollars based on the annual average exchange rate. Subsequently, the value is changed to real value (constant 2010 US$). (4) Since inward and outward FDI data from two economies do not normally coincide, I used only inward data. Thus, FDI data in my calculations are the sums of the inward data from both partners. The name of this variable is FDI.

and show time series transitions of top trade and FDI partners for 16 East Asian countries. Whereas Japan was the top trading partner in terms of the number of countries from the late 1980s to 2000, China has been in that position since the beginning of the new millennium, which clearly indicates China’s rise and Japan’s fall for trade. In contrast to trade, however, Japan is still in at the top as an FDI home country; thus, that situation remains one of “Asia in Japan’s embrace”.Footnote52 Singapore also actively invests in several countries, including India, Indonesia, and Japan.

Table 1. Top trading partners for East Asian countries.

Table 2. Top FDI (stock of inward) partners for East Asian countries.

In addition to the relations between regionalization and regionalism, I test H3 by introducing a dummy variable 1 if a dyad has problem of territorial dispute, and 0 otherwise. The data are from Taylor Fravel.Footnote53

4.3. Control variables

Other independent variables are introduced in order to control the above-mentioned main variable. First, following the argument of previous studies that democracies cooperate more and tend to reduce tariffs more, a dummy variable JDEMO was added. Polity II data, which are indicators of degrees of democracy,Footnote54 are used for this measure, such that I counted one if pair countries are both defined as democracies (with scores of more than six on a scale ranging from −10 to 10) and zero otherwise. Second, I took the relationship between trade and geographic distance into consideration. If the gravity model, which theorizes that the amount of trade has inverse proportion to distance, is correct, then the trade volume of two countries is a function of distance. To control this, the geographic distance between capitals (the unit is 1000 kilometers) was included. The name of this variable is DIST, and data were taken from the CEPII (Center d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales) website.Footnote55 Third, I consider the contagious or domino movement of regionalism, which is by nature a defensive action to PTAs established by other countries. The variable, World PTA (EIA), is the number of FTAs (or EIA) in each year. This variable also controls the time trend factor. Fourth, some studies have argued that when the difference between the market sizes of a pair of countries decreases, their possibility of concluding a PTA increases.Footnote56 Taking this argument into consideration, I introduced the variable DIFGDP, which measures an absolute value of difference of nominal GDPs (gross domestic products) between pair countriesFootnote57 as taken from the World Bank’s Data Catalog.Footnote58

All variables except JDEMO and World PTA (EIA) were logarithmically transformed. As PTA negotiations normally take two to five years from initiation to completion, I took three years’ lag as an independent variable except for DIST, which is the time invariant variable.Footnote59 shows descriptive statistics for all variables.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for the variables.

5. Regression results

Regression results are shown in –.

Table 4. Statistical results of survival analysis (Cox proportional hazards model).

Table 5. Statistical results of Survival Analysis (Cox proportional hazards model).

Table 6. Statistical results of survival analysis (Cox proportional hazards model).

The following are derived from the survival analyses. First, the trade volume has not influenced the formation of PTAs at all in East Asia, as neither nominal nor shared amounts of trade are statistically significant (whether GATT XXIV FTAs, the enabling clause FTAs, or EIAs) in the region. This result challenges the widely shared view in the literature. Second, in contrast to trade, the amount of FDI is statistically significant at the 1% level for all models. However, the FDI for the enabling clause FTA is negative (). These results confirm the two types of second hypotheses: an increase in the amount of FDI promotes GATT XXIV FTAs and EIA but does not promote enabling clause FTAs in East Asia.

Third, territorial disputes negatively affect the formation of GATT XXIV FTAs and EIA, but this is not statistically significant with the enabling clause FTAs. This finding can be partly explained by China’s strategic behavior. In November 2000, China proposed forming an FTA with ASEAN, and this was actualized in 2005 despite China’s territorial disputes with many ASEAN countries.

Fourth, whereas the democracy factor is not statistically significant for GATT XXIV FTAs and EIAs ( and , respectively), it is negatively significant at the 10% level for enabling clause FTAs. This result may reflect that some non-democratic countries in the region have been core participants in the enabling clause FTAs. Together with the empirical results presented by Remmer, which indicate that democratic factors have little effect on the promotion of cooperation among Mercosur nations,Footnote60 this result also challenges the recent literature on the relationship between democracy and PTAs. Previous studies may have been excessively Eurocentric, thus overlooking some dynamics of trade agreements involving non-democratic nations. Fifth, whereas DIFGDP is not significant at all in GATT XXIV and the enabling clause FTAs, it is significant when EIAs form the dependent variable (). Since there is no enabling clause-type outlet in EIAs, ASEAN countries have EIA agreements with all developed countries, China, and India, whose GDPs are larger. sixth, the influence of geographic distance on both FTAs and EIAs is positively significant, which means that the greater the distance between the two countries, the more likely they are to conclude a PTA. This unexpected result is explained by the small number of GATT XXIV FTAs and EIAs within ASEAN; only Brunei-Singapore and Singapore-Vietnam have those agreements. Consequently, ASEAN countries and their long-distance partners participate in GATT XXIV FTAs or EIAs. This also explains the negative significance of the relationship between the distance and enabling clause FTAs, in which ASEAN countries are the main participants.

6. Conclusion and implications

The relationship between regionalization and regionalism in East Asia is revealed here by survival analyses. The conclusion is that whereas there are positive and significant relationships between FDI and two types of PTAs (GATT XXIV FTAs or EIA), trade has no relations with all types of PTAs. Neither the amount of trade nor shared value is significant. This conclusion challenges the literature, which argued that an increase of PTAs in East Asia (the outcome of regionalism) is the outcome of economic interdependence (regionalization) and thereby presents a source of future research concerning the determinants of PTAs. The results of this study suggest that we should understand that regionalization is not a simple, single phenomenon and its effects are divergent. Regionalization entails not only trade but also the total of economic activities such as investment and emigration, all of which have been increasing in East Asia; however, their impacts on international politics are not always the same. Particularly, the increase of trade is not necessarily the driving force of PTAs.

This study represents an attempt to comprehensively clarify the relationship between regionalization and regionalism in East Asia. Therefore, the research made academic contributions in the sense that it provided clear evidence to the situation of previous studies, which formed conclusions based largely on impressionism and examined only a few cases. Furthermore, although the main purpose of this paper was not to identify contributing factors to the formation of PTAs in East Asia, I confirmed territorial disputes hinder the promotion of PTAs.

Finally, this paper only examines trade and FDI data; however, as mentioned above, regionalization also refers to other economic transactions such as labor emigration, and I need to incorporate this data into the model. Furthermore, the reason(s) that the results of East Asia vary from those of other parts of the world remains to be explained. The next step is to tackle these problems not only by the use of statistical analysis but also with specific case studies.

Acknowledgements

This study is a part of the research results of Social Science of Crisis Thinking, initiated by the Institute of Social Science, the University of Tokyo (https://web.iss.u-tokyo.ac.jp/crisis/en/). I wish to thank Professor Mie Oba and Momoko Nishimura for their helpful comments, and Matsuoka Tomoyuki and Yalezi Lee for research assistance.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this paper, “East Asia” refers to members of RCEP, namely, the ASEAN 10 countries (Brunei Darussalam (hereafter Brunei), Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic (hereafter Laos), Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam) and Australia, the People’s Republic of China (hereafter China), India, Japan, the Republic of Korea (hereafter South Korea) and New Zealand.

2 This definition is consistent with that of Mansfield and Milner, “The New Wave of Regionalism,” 592.

3 Fishlow and Haggard, The United States and the regionalization of the world economy; Haggard, “Comment”; Wyatt-Walter, “Regionalism, globalization, and world economic order”; Frankel, Regional Trading Blocs in the World Economic System; Kim, “Regionalization and Regionalism in East Asia”; Pempel, “Introduction: Emerging Webs of Regional Connectedness”; Söderbaum, Rethinking Regionalism; Börzel and Risse, The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism; and Acharya, “Asia is not one”.

4 Bernard, Mitchell and John Ravenhill, “Beyond Product Cycles and Flying Geese”; Hatch and Yamamura, Asia in Japan’s Embrace; Kim, “Regionalization and Regionalism in East Asia”; Green and Gill, Asia’s New Multilateralism; Ba, Kuik and Sudo, Institutionalizing East Asia ; and Yoshimatsu, Comparing Institution-building in East Asia, 41.

5 Aitken, “The Effect of the EEC and EFTA on European Trade”; Frankel Regional Trading Blocs; Winters and Wang, Eastern Europe’s International Trade; and Carrère, “Revisiting the Effects of Regional Trade Agreements.”

6 Baier and Bergstrand, “Do free trade agreements actually increase members’ international trade?”

7 Kawai and Wignaraja, “Asian FTAs: Trends and Challenges,” 19–20.

8 Büthe and Milner, “The Politics of Foreign Direct Investment into Developing Countries.”

9 Keohane, After Hegemony.

10 Ando, “Impacts of Japanese FTAs/EPAs”.

11 Dent, East Asian Regionalism, 218.

12 WTO, “Regional Trade Agreements Database.” Accessed July 14, 2019. http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/region_e/region_e.htm.

13 Kawai, “East Asian Economic Regionalism,” 30.

14 Munakata, Transforming East Asia, 29. See also Lim, “ASEAN: New modes of economic cooperation,” 21.

15 Lincoln, “Trade Links.”

16 Manger, Investing in Protection.

17 Manger, “Vertical Trade Specialization and the Formation of North-South PTAs,” 622–658.

18 Ravenhill, “The ‘new East Asian regionalism’,” 182.

19 Jetschke and Katada, “Asia,” 228; and Solís, “Global Economic Crisis,” 321. See also Searight, “Emerging Economic Architecture in Asia,” 205.

20 Haggard, “Regionalism in Asia and the Americas,” 45.

21 Ravenhill “The ‘New East Asian Regionalism’,” 185.

22 Ravenhill appeared to accept the argument that PTAs are negotiated in response to the policy challenges posed by increasing interdependence. He pointed out that East Asian countries have concluded or are currently negotiating with states outside the region that have been experiencing growth in economic interactions with the East Asian countries. Ravenhill “The ‘New East Asian regionalism’,” 185.

23 For example, Büthe and Milner, using a global data set and controlling endogeneity, demonstrated that PTAs cause an increase in FDI but not vice versa. Büthe and Milner, “The Politics of Foreign Direct Investment into Developing Countries”.

24 Dent, East Asian Regionalism, 8.

25 Other types include CU (custom unions); however, no country in East Asia has this type of PTA as of 2019.

26 World Trade Organization (WTO), “Submission on Regional Trade Agreements: Paper by Japan, TN/RL/W190.”

27 Tariffs among the AFTA members are currently moving toward zero; however, they were still high when AFTA was established in the early 1990s. Therefore, I estimated the two types of FTAs separately.

28 Thus, East Asian PTAs have more variations than the distinction between these two types. Although an analysis that considers such subtle differences is desirable, it is beyond the scope of this paper. This topic will be the theme of further research.

29 Tsebelis, Veto Players.

30 Grossman and Helpman, Interest Groups and Trade Policy.

31 Saxer, “Foreign Policy as a Socially Divisive Issue.”

32 Jones, “Explaining the Failure of the ASEAN Economic Community.”

33 In this regard, Katada and Solís (“Domestic Sources of Japanese Foreign Policy Activism”) argued that Japan’s export firms pushed hard for the Japanese government to conclude the Japan–Mexico PTA because otherwise they would have lost significant profits. Katada and Solís, “Domestic Sources of Japanese Foreign Policy Activism.”

34 Manger, “Vertical Trade Specialization and the Formation of North-South PTAs.”

35 Keidanren, “Kokusaitōshi rūru no kōchiku to kokunaitōshi kankyō no seibi wo motomeru (Requirement for establishing international investment rules and improving domestic investment environment),” July 16, 2012. Accessed August 12, 2019. http://www.keidanren.or.jp/japanese/policy/2002/042/honbun.html#s1.

36 Nesadurai, Globalization, Domestic Politics and Regionalism.

37 Mansfield, Milner, and Rosendorff, “Why Democracies Cooperate More”; Milner and Kubota, “Why the Move to Free Trade?”; and Mansfield and Milner, Votes, Vetoes, and The Political Economy of International Trade Agreements.

38 Chase, Trading Blocs, States, Firms, and Regions in the World Economy.

39 Baldwin, “A Domino Theory of Regionalism”; Baldwin and Jaimovich, “Are Free Trade-Agreements Contagious?”; and Baccini and Dür, “The New Regionalism and Policy Interdependence.”

40 Vasquez and Henehan, “Territorial Disputes and the Probability of War, 1816–1992”; and Lektzian, Prins, and Souva, “Territory, River, and Maritime Claims in the Western Hemisphere.”

41 Fravel, “Territorial and Maritime Boundary Disputes in Asia.”

42 This method was also employed by Baccini and Dür. Baccini and Dür, “The New Regionalism and Policy Interdependence.”

43 WTO, “Regional Trade Agreements Database.” Accessed July 16, 2019. http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/region_e/region_e.htm .

44 When a country has a PTA with ASEAN, I counted one between that country and individual ASEAN countries. Since ASEAN-South Korea and India-South Korea PTAs were notified under GATT Article XXIV as well as the enabling clause, I counted one in both FTAs.

45 (16 countries * 15 partners)/2 PTAs.

46 Exceptions are Australia-India, China-India, China-Japan, Japan-South Korea, India-New Zealand.

47 As mentioned above, regionalization refers to a general term that encompasses increased trade, FDI, and emigration within a specific region. Therefore, the amount of emigration should be incorporated into the independent variables. However, due to difficulties of data accessibility (Fitzgerald et al., Defying the Law of Gravity) particularly in the case of data for Southeast Asian nations, I used only trade and FDI data here. I will try to include emigration data in future research.

48 As two countries’ data (export of country i to country j and import of j from i) normally do not correspond, I calculated this as follows.1/2 [1/2(Export + Import of country i to country j) + 1/2(Export + Import of country j to i)]. When data of country i do not exist or are counted as zero, I only use country j’s data.

49 IMF, “Direction of Trade Statistics.” Accessed July 10, 2019. https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61013712.

50 OECD, ”FDI statistics.” Accessed July 15, 2019. https://stats.oecd.org/. After 2012, compiling FDI statistics was shifted from the 3rd edition of the OECD Benchmark Definition of Foreign Direct Investment (BMD3) to BMD4. Therefore, data from 1985 to 2012 were derived from the BMD3 and data from 2013 (2014 for Japan) were gained from the BMD4.

51 These data are collected from the Department of Commerce (China), the Department of Industrial Policy & Promotion (India), the Bank of Indonesia, the Malaysian Industrial Development Authority (Central Bank of Malaya), the Central Statistical Organization (Myanmar), the Central Bank of the Philippines, the Board of Investment of Thailand (Bank of Thailand), and the Ministry of Planning and Investment (Vietnam).

52 Hatch and Yamamura, Asia in Japan’s Embrace.

53 Fravel, “Territorial and Maritime Boundary Disputes in Asia.” I changed the data when the information was obviously incorrect (e.g., a dispute between Japan and the Philippines). Furthermore, because the data ends in 2012, I updated the data by referring to media sources.

54 Center for Systemic Peace, “POLITY IV dataset.” Accessed July 29, 2019. http://www.systemicpeace.org/.

55 Center d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales,”GeoDist.” Accessed February 13, 2012. http://www.cepii.fr/anglaisgraph/bdd/distances.htm.

56 Baier and Bergstrand, “Do free trade agreements actually increase members’ international trade?”; Endo, “Quality of Governance and the Formation of Preferential Trade Agreements.”

57 | GDPi – GDPj |.

58 The World Bank. ”GDP data.” Accessed July 26, 2019. https://data.worldbank.org/. Data unit are constant 2010 US$.

59 For instance, the average and median number of days that the Japanese government has spent on PTA negotiations are approximately 1,300 and 1,100 (as of November 2019), respectively, but these numbers will be much larger when the deadlocked negotiations with South Korea and RCEP are included. Moreover, Freund and McLaren have argued that trade increases before PTA formation. Thus, I also analyze the four-year and five-year lags as a robustness check, following Freund and McLaren (1999).

60 Remmer, “Does Democracy Promote Interstate Cooperation?.”

Bibliography

- Acharya, A. “Asia Is Not One.” The Journal of Asian Studies 69, no. 4 (2010): 1001–1013. doi:10.1017/S0021911810002871.

- Aitken, N. D. “The Effect of the EEC and EFTA on European Trade: A Temporal and Cross-Section Analysis.” American Economic Review 63, no. 5 (1973): 881–892.

- Ando, M. “Impacts of Japanese FTAs/EPAs: Post Evaluation from the Initial Data.” RIETI Discussion Paper Series 07-E-041 (2007).

- Ba, A. D., C.-C. Kuik, and S. Sudo. “Introduction.” In Institutionalizing East Asia: Mapping and Reconfiguring Regional Cooperation, edited by A. D. Ba, C.-C. Kuik, and S. Sudo, 1–8. Abingdon: Routledge, 2016.

- Baccini, L., and A. Dür. “The New Regionalism and Policy Interdependence.” British Journal of Political Science 42, no. 1 (2012): 57–79. doi:10.1017/S0007123411000238.

- Baier, S. L., and J. H. Bergstrand. “Do Free Trade Agreements Actually Increase Members’ International Trade?” Journal of International Economics 71, no. 1 (2007): 72–95. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2006.02.005.

- Baldwin, R. “A Domino Theory of Regionalism.” Working Paper 4465 of National Bureau of Economic Research, MA: Cambridge, September, 1993.

- Baldwin, R., and D. Jaimovich. “Are Free Trade Agreements Contagious?” Journal of International Economics 88, no. 1 (2012): 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2012.03.009.

- Bernard, M., and J. Ravenhill. “Beyond Product Cycles and Flying Geese: Regionalization, Hierarchy, and the Industrialization of East Asia.” World Politics 47, no. 2 (1995): 171–209. doi:10.1017/S0043887100016075.

- Bhagwati, J. “Regionalism versus Multilateralism.” The World Economy 15, no. 5 (1992): 535–556. doi:10.1111/twec.1992.15.issue-5.

- Börzel, T. A., and T. Risse. “Introduction: Framework of the Handbook and Conceptual Clarifications.” In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism, edited by T. A. Börzel and T. Risse, 3–15. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Büthe, T., and H. Milner. “The Politics of Foreign Direct Investment into Developing Countries: Increasing FDI through Trade Agreements?” American Journal of Political Science 52, no. 4 (2008): 741–762. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00340.x.

- Carrère, C. “Revisiting the Effects of Regional Trade Agreements on Trade Flows with Proper Specification of the Gravity Model.” European Economic Review 50, no. 2 (2006): 223–247. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2004.06.001.

- Chase, K. A. Trading Blocs, States, Firms, and Regions in the World Economy. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2005.

- Dent, C. M. East Asian Regionalism. Abingdon: Routledge, 2008.

- Dent, C. M. “Free Trade Agreements in the Asia-Pacific a Decade On: Evaluating the Past, Looking to the Future.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 10, no. 2 (2010): 201–245. doi:10.1093/irap/lcp022.

- Emmers, R., ed. ASEAN and the Institutionalization of East Asia. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

- Endo, M. “Quality of Governance and the Formation of Preferential Trade Agreements.” Review of International Economics 14, no. 5 (2006): 758–772. doi:10.1111/roie.2006.14.issue-5.

- Fishlow, A., and S. Haggard. The United States and the Regionalisation of the World Economy. Washington, DC: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 1992.

- Fitzgerald, J., D. Leblang, and J. C. Teets. “Defying the Law of Gravity: The Political Economy of International Migration.” World Politics 66, no. 3 (2014): 406–445. doi:10.1017/S0043887114000112.

- Frankel, J. A. Regional Trading Blocs in the World Economic System. Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics, 1997.

- Green, M. J., and B. Gill, eds. Asia’s New Multilateralism: Cooperation, Competition, and the Search for Community. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

- Grossman, G. M., and E. Helpman. Interest Groups and Trade Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Haggard, S. “Comment.” In Regionalism and Rivalry: Japan and the United States in Pacific Asia, edited by J. A. Frankel and M. Kahler, 48–52. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993.

- Haggard, S. “Regionalism in Asia and the Americas.” In The Political Economy of Regionalism, edited by E. D. Mansfield and H. V. Milner, 20–49. New York: Colombia University Press, 1997.

- Hatch, W., and K. Yamamura. Asia in Japan’s Embrace: Building a Regional Production Alliance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Institute for International Trade and Investment (ITI). Sekai shuyōkoku no chokusetsu tōshi tōkei [Direct investment statistics for major countries in the world], Tokyo: ITI, various year.

- Jetschke, A., and S. N. Katada. “Asia.” In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism, edited by T. A. Börzel and T. Risse, 225–249. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Jones, L. “Explaining the Failure of the ASEAN Economic Community: The Primacy of Domestic Political Economy.” The Pacific Review 29, no. 5 (2016): 647–670. doi:10.1080/09512748.2015.1022593.

- Katada, S., and M. Solís. “Domestic Sources of Japanese Foreign Policy Activism: Loss Avoidance and Demand Coherence.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 10 (2010): 129–157. doi:10.1093/irap/lcp009.

- Katada, S. N., and M. Solís, eds. Cross Regional Trade Agreements: Understanding Permeated Regionalism in East Asia. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2008.

- Kawai, M. “East Asian Economic Regionalism: Progress and Challenges.” Journal of Asian Economics 16, no. 1 (2005): 29–55. doi:10.1016/j.asieco.2005.01.001.

- Keohane, R. After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Kim, S. S. “Regionalization and Regionalism in East Asia.” Journal of East Asian Studies 4, no. 1 (2004): 39–67. doi:10.1017/S1598240800004380.

- Lektzian, D., B. C. Prins, and M. Souva. “Territory, River, and Maritime Claims in the Western Hemisphere: Regime Type, Rivalry, and MIDs from 1901 to 2000.” International Studies Quarterly 54, no. 4 (2010): 1073–1098. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2010.00627.x.

- Lim, L. Y. C. “ASEAN: New Modes of Economic Cooperation.” In Southeast Asia in the New World Order: The Political Economy of a Dynamic Region, edited by B. Burton and D. Wurfel, 19–35. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

- Lincoln, E. J. East Asian Economic Regionalism. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2004.

- Manger, M. S. Investing in Protection: The Politics of Preferential Trade Agreements between North and South. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Manger, M. S. “Vertical Trade Specialization and the Formation of North-South PTAs.” World Politics 64, no. 4 (2012): 622–658. doi:10.1017/S0043887112000172.

- Mansfield, E. D., and H. V. Milner. “The New Wave of Regionalism.” International Organization 53, no. 3 (1999): 589–627. doi:10.1162/002081899551002.

- Mansfield, E. D., and H. V. Milner. Votes, Vetoes, and the Political Economy of International Trade Agreements. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.

- Mansfield, E. D., H. V. Milner, and B. Peter Rosendorff. “Why Democracies Cooperate More: Electoral Control and International Trade Agreements.” International Organization 56, no. 3 (2002): 477–513. doi:10.1162/002081802760199863.

- Masahiro, K., and G. Wignaraja. “Asian FTAs: Trends and Challenges.” ADBI Working Paper No. 144, Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute, August 2009.

- Milner, H. V. with Keiko Kubota. “Why the Move to Free Trade? Democracy and Trade Policy in the Developing Countries.” International Organization 59, no. 1 (2005): 107–143. doi:10.1017/S002081830505006X.

- Munakata, N. Transforming East Asia: The Evolution of Regional Economic Integration. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2006.

- Nesadurai, H. Globalisation, Domestic Politics and Regionalism: The ASEAN Free Trade Area. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Pempel, T. J. “Introduction: Emerging Webs of Regional Connectedness.” In Remapping East Asia: The Construction of a Region, edited by T. J. Pempel, 1–30. New York: Cornell University Press, 2005.

- Ravenhill, J. “The ‘new East Asian Regionalism’: A Political Domino Effect.” Review of International Political Economy 17, no. 2 (2010): 178–208. doi:10.1080/09692290903070887.

- Remmer, K. L. “Does Democracy Promote Interstate Cooperation? Lessons from the Mercosur Region.” International Studies Quarterly 42, no. 1 (1998): 25–51. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00068.

- Saxer, C. J. “Foreign Policy as a Socially Divisive Issue: The KORUS Free-trade Agreement.” The Pacific Review 30, no. 4 (2017): 566–580. doi:10.1080/09512748.2016.1264461.

- Searight, A. “Emerging Economic Architecture in Asia.” In Asia’s New Multilateralism: Cooperation, Competition, and the Search for Community, edited by M. J. Green and B. Gill, 193–242. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

- Söderbaum, F. Rethinking Regionalism. New York: Palgrave, 2016.

- Solís, M. “Global Economic Crisis: Boon or Bust for East Asian Trade Integration?” The Pacific Review 24, no. 3 (2011): 311–336. doi:10.1080/09512748.2011.577232.

- Tsebelis, G. Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2002.

- Vasquez, J., and C. S. Leskiw. “The Origins and War Proneness of Interstate Rivalries.” Annual Review of Political Science 4, no. 1 (2001): 295–316. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.295.

- Winters, L. A., and Z. K. Wang. Eastern Europe’s International Trade. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994.

- Wyatt-Walter, A. “Regionalism, Globalization, and World Economic Order.” In Regionalism in World Politics: Regional Organization and International Order, edited by L. Fawcett and A. Hurrell, 74–121. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Yoshimatsu, H. Comparing Institution-building in East Asia: Power Politics, Governance, and Critical Junctures. Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.