ABSTRACT

The conflict between Mainland China and Hong Kong regarding the issue of how much autonomy Hong Kong would retain is becoming increasingly intense, especially after the Occupy Central Movement arose in 2014. This paper focuses on the “rule of law” policy under Xi’s government and analyzes how and why the CCP’s rule over Hong Kong was strengthened. Although Xi promotes the “rule of law,” it is different from the one in democracy. This paper, first, outlining the characteristics of the “rule of law” during Xi Jinping’s era and explaining the differences between the rule of law in democracy and the one in China. Second analysis is revealing the personal affairs and organizational structure of the party apparatus to see the linkage of the “rule of law” policy under Xi’s government with the CCP’s control over Hong Kong, and third is examining the reflection and rhetoric of the CCP’s “rule of law” governance over Hong Kong based on the politicians’ discourses. This paper reveals that the “rule of law” with Chinese characteristics implies standardizing the law, centralizing the power, and stabilizing society. The CCP has continually claimed to be “Governing Hong Kong according to Law” but the CCP would only accept the “rule of law” with these characteristics and, of course, without democratization.

1. Introduction

The characteristics of Hong Kong’s political conditions are defined in article 2 of the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR), which states that the National People’s Congress authorizes the HKSAR to exercise a high degree of autonomy and enjoy executive, legislative, and independent judicial power, including that of final adjudication, in accordance with the provision of this lawFootnote1 A capitalist economy, which is another characteristic of Hong Kong, is applied under the “One Country Two System” principle. However, it is well known that these characteristics have been disappearing due to the looming shadow of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s authority.

As the Basic Law defines that the Standing Committee of the People’s Congress has the right and power to interpret the Basic Law, the election system in Hong Kong is controlled by the Central Government in Mainland China. Half of the seats in the Legislative Council of Hong Kong are elected by direct election and the other half are restricted: only pro-Beijing businesspeople and professionals can vote. The Chief Executive is elected by a broadly representative Election Committee, in accordance with the Basic Law, and appointed by the Central GovernmentFootnote2 Based on such restrictions, only pro-Beijing politicians are appointed to the Chief Executive and always form the majority of the Legislative Council. Also, the economic supremacy in Hong Kong is declining as the economic growth in Mainland China grows stronger. Therefore, the independence of the judiciary, which is one of the most important components for creating the rule of law, becomes and is recognized as a final frontier for sustaining a high level of autonomy in Hong Kong. It has been retained because Hong Kong applies a different style of legal system compared with Mainland China.

However, the CCP has also started to interfere in the rule of law in Hong Kong. The CCP held the Fourth Plenary Session of the 19th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in Beijing at the end of October 2019, and the CCP released a communique. It mentioned that the governance over Hong Kong must be based on the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Basic Law of the HKSAR, and also stated that a legal system and law-enforcement mechanism in the special administrative regions for safeguarding national security should be established and improvedFootnote3 The CCP has constantly claimed that “Hong Kong people rules Hong Kong (Gang Ren Zhi Gang)” and the Basic Law of the HKSAR enabled the Hong Kong government to introduce a law for safeguarding national security in Hong Kong, but it failed in 2003. The CCP understood that the Hong Kong Security Law is necessary to quell the anti-China movement, and the Hong Kong government is too weak to pursue it. The anti-China movement in Hong Kong recently intensified, and the CCP’s attitude toward Hong Kong became firmer. In the end, the communique officially stated that the CCP’s motive in creating the Hong Kong Security Law through the procedure in the People’s Congress in Mainland China, not the Legislative Council of HKSAR, was to strengthen the CCP’s rule over Hong Kong. According to the explanation of the Commission of Legislative Affairs of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee about the draft law on safeguarding national security in HKSAR, the draft law defines that the Chief Executive is required to select a pool of judges from among active judges and “qualified” retired judges to hear all national security criminal casesFootnote4 Although Chief Executive Carrie Lam promised not to hand-pick individual judges to oversee specific Hong Kong National Security Law and rejected calls from the pro-Beijing camp to select only Chinese judges, the law states that the Chief Executive has a superior status to the judiciaryFootnote5 This means that the ability to separate the three powers is denied. The bill engendered severe criticism from overseas, but was finally passed by the National People’s Congress at the end of June 2020.

The battle between Hong Kong and Mainland China regarding the issue of how much autonomy Hong Kong would retain is becoming increasingly intense, especially after the Occupy Central Movement arose in 2014. Compared to the Hu Jintao era, it is widely recognized that Xi Jinping is adopting a firm attitude toward Hong Kong and that the strength of Hong Kong’s citizens’ reactions is intensifying. Regarding the current circumstances in Hong Kong, previous researchers have examined the mechanism of the protests to understand why Hong Kong’s citizens are taking actionFootnote6, as well as the CCP’s logic in strengthening the control over Hong KongFootnote7 Additionally, there are abundant studies about the legal system in Hong Kong, as this is one of the most important aspects related to installing the rule of law to realize a high level of autonomy. Their work focuses on how the legal and judicial systems in Hong Kong were defined during the negotiations between the UK and Mainland ChinaFootnote8, and whether or not these systems were transformed because of the authority of Mainland China from the perspective of Hong KongFootnote9 However, how Xi Jinping’s domestic policies influence its control over Hong Kong is rarely examined. This paper focuses on the “rule of law” policy under Xi’s government and the linkage of his domestic policy with his Hong Kong policy to analyze how and why the CCP’s rule over Hong Kong was strengthened. Zhu (2019) examined the evolution of the political strategies of Beijing’s rule over Hong Kong from a legal perspective, but focuses on neither the CCP’s logic nor the linkage between the domestic policies and the CCP’s rule over Hong KongFootnote10 This paper aims to explain that the “rule of law” with Chinese characteristics implies 1) standardizing the law, 2) centralizing power, and 3) stabilizing society. These characteristics are also connected to and appear in the CCP’s rule over Hong Kong. The CCP has continually claimed to be “Governing Hong Kong according to Law” but the CCP would only accept “rule of law” with these characteristics, and, of course, without democratization.

To analyze the research question stated above, this paper, first, outlines the characteristics of the “rule of law” in Xi Jinping’s era. Second, it reveals how the “rule of law” policy under Xi Jinping’s government reflects the personnel affairs and organizational structure in reality, picking up the Central Leading Group on Hong Kong and Macao Affairs (Zhonggong Zhongyang GangAo Gongzuo Lingdao Xiaozu), to see how the CCP is strengthening the governance over Hong Kong. Third, it traces the politicians’ discourses about the Hong Kong policy in order to understand the CCP’s logic.

2. The “Rule of Law” policy under Xi Jinping’s government

2.1. Standardizing law and centralizing the power

It is recognized that a law under an authoritarian regime is a tool for a political leader to govern a country; therefore, an authoritarian regime only accepts rule by law, and rule of law only suits a democratic regime. This understanding is based on the idea that the jurisdiction of an authoritarian regime is controlled by a political leader, so he/she is not restricted by laws. Although Xi raised “A Comprehensive Framework for Promoting the Rule of Law (Qianmian Yifa Zhiguo)” as an important political issue and explained that promoting the “rule of law” is crucial for regime survival, it is doubtful that the “rule of law” in China is synonymous with the rule of law in a democratic regime. The differences between rule by law and the rule of law relate to whether or not a legal system encourages political freedom and how far a law restricts a political leader. According to this understanding, it cannot be categorized that China enjoys the rule of law. Zhou Qiang, the President of the Supreme People’s Court, stated, during a speech that “we should resolutely resist erroneous influence from the West: ‘constitutional democracy,’ ‘the separation of powers,’ and ‘the independence of the judiciary’.”Footnote11

However, the statistical data shows that any correlation between political freedom and the level of the rule of law under authoritarianism is absentFootnote12 This indicates that there are variety of the “rule of law” in authoritarian countries. Therefore, this paper, first, illustrates what the “rule of law” is with Chinese characteristics under Xi’s government by tracing the politicians’ discourses.

The most important element in promoting the “rule of law” in Hu Jintao’s era was the judicial reform. Hu organized the Central Leading Group for Judicial Reform (Zhongyang Sifa Tizhi Gaige Lingdao Xiaozu) in 2003, and the group published “the Preliminary Opinion for Reform of Judicial System and its Mechanism (Zhongyang Sifa Tizhi Gaige Lingdao Xiaozu Guanyu Sifa Tizhi he Gongzuo Jizhi Gaige de Chubu Yijian)” in 2004. Hu repeatedly claimed to be promoting judicial reform and published the first White Paper on Judicial Reform in China. It stated that China has witnessed rapid economic and social development and the public’s awareness of the importance of “rule of law (Fazhi)” has been remarkably enhanced since the introduction of the reform and opening-up policies. It also proposed that one of the fundamental objectives of China’s judicial reform is to provide a solid, reliable judicial guarantee for safeguarding the legitimate rights and interests of people, social equity and justice, and lasting national stabilityFootnote13 The judicial function of not only controlling society but also protecting the people’s rights and interests originated in Hu’s era and he attempted to promote this idea for regime survival, not to enhance political freedom.

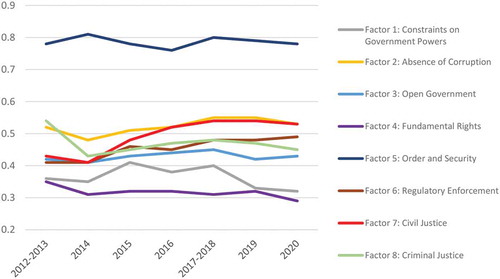

At the beginning of Xi’s government, Xi inherited Hu’s legacy regarding promoting the “rule of law.” At the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of China in November 2013, the gazette reported that it is vital to deepen the judicial reform for the construction of Chinese “rule of law (Fazhi).”Footnote14 The Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Some Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening the Reform (Decision (2013)) was also adapted at the same time. Section 9, the Promotion of Chinese “rule of law” (Tuijin Fazhi Zhongguo Jianshe), of the Decision (2013) states that that involves deepening the judicial reform, encouraging the construction of a fair, efficient and authorized socialistic judicial system, and protecting people’s rightsFootnote15 The rule of law indicator that the World Bank provides also shows improvements in civil justice, which works to protect people’s rights and interests (). Civil justice measures whether ordinary people can resolve their grievances peacefully and effectively through the civil justice systemFootnote16 The revision of the Civil Procedure Law in 2013 and the Administrative Procedure Law in 2014 had an impact in terms of improving the civil justice system.

Graph 1. Factors of the Rule of Law in China from 2012 to 2020

At the Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of China in October 2014, the Decision of the CPC Central Committee on Major Issues Pertaining to Comprehensively Promoting the “Rule of Law” (Decision (2014)) was submitted. This session was crucial, as it was the first session which focused on the construction of the “rule of law” in China. Referring to the Decision (2014), it appears that Xi considered the construction of the “rule of law” not only as deepening the judicial reform but also as covering the major important national policies. It also points out that maintaining the CCP’s leadership is the principle for actualizing the “rule of law.” As the Chinese constitution defines the CCP’s leadership, obeying the constitution and accepting the CCP’s leadership are the most basic requirements for the promotion of the “rule of law.” Therefore, the Decision (2014) remarkably describes how “the CCP’s leadership coincides with socialistic ‘rule of law,’ socialistic ‘rule of law’ should keep the CCP’s leadership, and the CCP’s leadership should rely on a socialistic ‘rule of law’.”Footnote17

To maintain the CCP’s authority, the “rule of law” policy especially focuses on two practices: standardizing the law and centralizing power. For example, in the case of judges’ professionalization, the CCP promoted the standardization of legal knowledge and judgments among judges and centralization of the court system. It is well known that judges who have not taken the National Bar Examination in China and who have served as government officials are seconded to a court. In order to professionalize such judges, the CCP revised the Judges Law and required them to participate in training in order to meet the requirements for being professional judges. To standardize the judgments, the CCP issues guidance cases and asks the local people’s court to follow theseFootnote18 Compared to the common law system, the Chinese socialist law system does not consider cases as important when delivering a judgment. As the problems of the decentralization of the people’s court system grew more severe, the judges did not follow the legal rules, and tended to protect local benefits. Therefore, similar cases produce varying results, depending on the locality.

For the centralization of the court system, the authority for managing personnel affairs in the middle level and the basic level of people's court was transferred from the party group at the same government level as the people’s court to the party group in provincial level. Xi recognized that this transformation would solve the problems of decentralization and localization.

2.2. The importance of social stability under the “Rule of Law” policy

Although Xi’s government encourages the “rule of law” as one of the most important national policies, the status of the judicial apparatus has not been upgraded. The president of the supreme people’s court has been appointed from the members of the central committee of the CCP, and their appointment to the Central Political Legal Committee (CPLC: Zhengfa weiyuanhui), which is the party political legal apparatus and guarantees the CCP’s control over the legal and public security apparatus, has been pursued. However, it was only Ren Jianxin who was the president of the supreme people’s court from 1988 to 1997 and appointed as the director of the CPLC from 1992 to 1997. Contrary to the status of the judicial apparatus, the public security apparatus has expanded dramatically. Wang and Minzer (2015) demonstrate how the party authorities increased the bureaucratic rank of public security chiefs within the party apparatusFootnote19

shows the list of the director of the CPLC from 1978 to 2020. It is clear that a person who has worked in Public Security is appointed as the director of the CPLC, especially from 2007. As a chief of Public Security usually is appointed a member of the CPLC, it can be interpreted that a person’s political rank is obviously upgraded on joining this committee.

Table 1. List of Director of the Central Political Legal Committee from 1978 to 2020

While the political rank of the Public Security is upgraded, Xi attempted to encourage not only the deepening of the judicial reform but also the expansion of the scope to include comprehensive national policies for realizing the “rule of law,” and Xi especially focused on social stability. The section on improving the public security system in the Decision (2013) stated that “we will strengthen comprehensive measures for public security, introduce a multi-tiered prevention and control system for public security, and strictly guard against and punish all sorts of unlawful and criminal activities in accordance with the law. We will establish the National Security Commission (Guojia Anquan Weiyuanhui) and improve the national security system and strategies to guarantee the country’s national security.”Footnote20 The first meeting of the National Security Commission of the CPC was held on April 2014. Xi proposed an “overall national security outlook (Zongji Guojia Anquanguan)” and stated that “we must pay attention to external security and also focus on the importance of internal security. We must seek development and reform regarding internal security and establish a stable China. We must seek peaceful cooperation and mutual benefit to create external security and construct a harmonious world.”Footnote21 Based on Xi’s speech, the definition of national security is not only external security but also internal and public security. Also, referring to the Decision (2013), it can be explained that Xi’s focus on public security is strong.

A ruler in an authoritarian regime usually faces two concerns: power sharing with political elites and social controlFootnote22 This is because there is a statistically high possibility that an authoritarian regime will be subverted by a coup d’état and uprising. Based on this theory, the CCP, without exception, observes how much support they would receive from the political elite and society, and also considerably care about their activities. In the case of Xi’s government, it especially focused on social control for their survival. The statistical data () clearly show that the fiscal expenditure on public security greatly increased after 2015, exceeding that on national security.

Graph 2. Fiscal expenditure on public security and national security from 2002 to 2018

Although Xi’s government emphasized social control, this does not mean that Xi’s government preferred to control by force rather than by legal means. The Decision (2014) stated that “to implement an ‘overall national security outlook,’ it is necessary to accelerate to build up the rule of law regarding national security, promulgate to legislate urgent laws such as anti-terrorism, promote the rule of law on public security, and establish the legal system for national security.” It can be interpreted that the concept of the “rule of law” is also important for social control, and Xi’s government attempted to legislate laws which are related to national security. This legislature aims to define and strengthen the CCP’s authority over society, and it can also be determined that Xi’s government aimed to standardize the law, and centralize the power regarding public security. According to this understanding, this paper considers that the “rule of law” policy under Xi’s government comprises 1) standardizing the law, 2) centralizing power, and 3) stabilizing society. This concept of the “rule of law” under Xi’s government also reflects the CCP’s rule over Hong Kong.

3. Linkage between the “Rule of Law” policy under Xi’s government and the CCP’s control over Hong Kong

The CCP has constantly claimed that “Hong Kong people rule Hong Kong,” but the rise of an anti-China movement in Hong Kong, especially after 2003, made the CCP emphasize “No Interference, but Play Our Role (Bu Ganshe, Yousuo Zuowei).”Footnote23 The communique of the Fourth Plenary Session of the 16th Central Committee of the CPC, released in September 2004, mentioned that “maintaining the long-term prosperity and stability of Hong Kong and Macao is a new task that the CCP faces under the new circumstances,” and it is clear that the CCP considered the Hong Kong issue was becoming increasingly important. Also, the Central Coordinating group for Hong Kong and Macao Affairs (Zhongyang GangAo Gongzuo Xietiao Xiaozu: the Coordinating Group) was organized in July 2003 and oversaw Hong Kong and Macao issue. Qian Qichen was responsible for Hong Kong issues since the return of Hong Kong to Mainland China in 1997. After the Coordinating group was established, a member of the political Bureau Standing Committee, such as Zheng Qinghong, Xi Jinping, Zhang Dejiang, and Han Zheng, became its head.

This transformation shows that Hong Kong and Macao affairs were increasingly considered more important. The government body of the PRC also has an office to deal with those affairs, named the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office of the State Council (Guowuyuan Gang Ao Shiwu Banggongshi: HKMAOSC), and the corresponding office in Hong Kong is the Liaison Office of China’s Central Government in Hong Kong (Zhongyang Zhengfu Zhu Xianggang Lianluo Bangongshi: LOCCGHK). HKMAOSC plays an important role in making policies regarding Hong Kong and Macao affairs. LOCCGHK, as a representative of Hong Kong, collects information for policy setting and takes charge of policy implementationFootnote24 It is estimated that the directors of these offices are appointed to the Coordinating Group; however, the actual operation of the Coordinating group and the relationship between these two offices remain unclear. It is a fact that the Coordinating Group, as a party apparatus, has authority and leads the two offices. Although the details and core information about the Coordinating group remain unclear, collecting information and illustrating the partial characteristics of the Coordinating group is one of the clues to understanding the tendency or transformation of the CCP’s policy regarding Hong Kong issues.

provides a list of the names of the Coordinating Group from 2008 to 2020. The Coordinating Group can be recognized as a highly important organization among those within the Central Committee of the CCP, as a member of the Political Bureau Standing Committee is appointed as director and a member of the Political Bureau is appointed as the deputy. The information for the period from 2013 to 2018 is very limited, but it can be estimated that every generation has a head of HKMAOSC. Besides, a few members occupy a position in the leading groups of Taiwan, Tibet, and “One Belt One Road,” which is related to a core interest of China. Additionally, some members were also appointed to the United Front Work Department (Tongyi Zhanxian Bu: UFWD), which takes charge of multi-party cooperation. Several democratic parties are organized as representatives of specific areas, such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, and minority regions in Mainland China. It is significant for the CCP’s survival strategy to maintain democratic parties and manage a sustainable relationship between them and the leadership of the UFWD. Therefore, the members of the Coordinating Group are also appointed to the UFWD.

Table 2. Name List of the Central Cooperation Group for Hong Kong and Macao Affairs from 2008 to 2020

The appointment of the organizations that relate to national and public security, such as the National Security Commission of the CPC Central Committee, the Central Leading Group for Foreign Affairs (Leading Group for State Security), and the Ministry of Public Security, as members of the Coordinating Group occurred particularly after Xi’s government came to power in 2013. Moreover, the coordinating Group was renamed the Central Leading Group for Hong Kong and Macao Affairs (Zhongyang Gan Ao Gongzuo Lingdao Xiaozu: The Leading Group)Footnote25 There is a significant difference “Leading” and “Coordinating” in Chinese politics. “Leading” implies the CCP’s authority and the Leading Group works on specific issues with the CCP’s leadership and control. It was also reported that Zhao Kezhi, who is a deputy head of the CPLC and a head of the department of Public Security, was appointed the first deputy head of the leading groupFootnote26 He was the fifth deputy head of the leading group when it was organized in 2019 and it seems that his position was upgraded in 2020. Based on the analysis of the first section of this paper, one of the most important aspects of Xi’s “rule of law” policy is social stability, and Xi’s government especially encourages the public security apparatus for realizing it. Although the director of the Supreme People’s Court is a member of CPLC, the People’s Court cannot be independent from the CPLC, should follow its leadership, and collaborate with the public security apparatus for social stability based on “rule of law” policy. Therefore, the appointment of Zhao to the Leading Group implies that the CCP recognizes Hong Kong affairs as a national and social security issue, and needs to deal with these affairs by standardizing the law, centralizing power, and stabilizing society, which are all “rule of law” policies under Xi’s government.

4. CCP’s “Rule of Law” policy and its Hong Kong governance

4.1. Xi Jinping’s domestic policy and the CCP’s control over Hong Kong

In April 1987, Deng Xiaoping stated that “Hong Kong’s system of government should not be completely westernized. For a century and a half, Hong Kong has been operating under a system different from those of Britain and the United States. I am afraid it would not be appropriate for its system to copy those of Britain and the United States with, for example, the separation of the three powers and a British or American parliamentary system.”Footnote27 According to this statement, the bottom line of the CCP’s requirement regarding Hong Kong is to retain “One Country Two System” principle, and democratization in Hong Kong is unacceptable. Under Hu’s government, Wen Jiabao repeatedly claimed the following three points: the “One Country Two System” principle, Hong Kong citizens rule Hong Kong, and keeping a high level of autonomyFootnote28 Additionally, Wen pointed that the government on the Mainland would not interfere in politics in Hong Kong, based on the Basic LawFootnote29 The CCP’s political leaders gradually strengthened the CCP’s authority toward Hong Kong, especially after the 10th anniversary of Hong Kong’s retrocession in 2007. Hu, at that time, stated that “‘one country’ is the prerequisite of the ‘two systems’” and “‘one country’ means that we must uphold the power vested in the central government and China’s sovereignty, unity and security.” At the same time, Wu Bangguo also stressed the following two points; first, that the high level of autonomy in Hong Kong did not originate in Hong Kong, but comes from the CCP’s authority and, second, that the most important characteristic of Hong Kong’s political system is the administrative initiative, so the Chief Secretary for Administration in Hong Kong should be responsible not only for the Special Administrative Region but also for the Central Government of PRCFootnote30

Xi had a meeting with Leung Chun-ying immediately after Xi’s government came to power. Referring to concerns over whether the recent party leadership reshuffle might affect the policy, he pointed out “I can tell you all here that the central government’s ruling policy regarding Hong Kong and Macau remains unchanged,” and “the key is to comprehensively and accurately understand and implement the ‘One Country Two Systems’ as well as respect and safeguard the Basic Law.”Footnote31 According to Xi’s comment, it can be interpreted that, initially, the CCP’s rule over Hong Kong was no firmer than that of the previous government, and Xi’s government inherited the previous government’s role toward Hong Kong. Zhang Xiaoming additionally indicated that “it is the constitutional obligation of the HKSAR to complete the legislation on article 23 of the Basic Law and to safeguard national security. As to when start this legislation, I believe the SAR government will make an appropriate choice based on the current circumstance in Hong Kong,” and “I don’t think that the legislation on article 23 of the Basic Law is a forbidden area that can’t even be mentioned.”Footnote32 His comment was supposed to indicate that the CCP’s attitude toward Hong Kong remained unchanged, as he mentioned the legislation in article 23 depended on the government of Hong Kong.

Xi, at the beginning of his government, repeatedly claimed “Realizing China’s Dream of a Great Chinese Nation Rejuvenation” as a hallmarkFootnote33, and directly mentioned that Hong Kong compatriots, with strong national self-esteem and pride, would contribute to the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nationFootnote34 Based on this political slogan, the CCP emphasized China’s sovereignty and requested that Hong Kong should respect the political regime and its system in Mainland China. Although the CCP did not enforce obedience on Hong Kong with this slogan, the CCP implicated the centralizing power. It was discussed whether the CCP’s control over Hong Kong would tighten because of the party leadership reshuffle; however, it grew firmer and prepared to exercise force when the anti-China movement intensified in Hong Kong. Also, this preparation was implemented under the concept of the “rule of law.” The next section examines the CCP’s rhetoric regarding the concept of the “rule of law.”

4.2. The conflict between the concept of the “Rule of Law” in mainland China and Hong Kong

Xi Jinping attracted severe criticism from the Hong Kong Bar Association when he stated that the legislative, judiciary, and administration must cooperate with each otherFootnote35 The Hong Kong Bar Association stated that the judiciary in Hong Kong is totally independent, based on the Basic Law, as they understood that Xi’s comment implied that the separation of power in Hong Kong does not exist. According to article 85 of the Basic Law, “the courts of the HKSAR shall exercise judicial power independently, free from any interferences.”Footnote36 Therefore, it is possible for the courts of HKSAR to deliver an unconstitutional judgment regarding the decision that other government bodies made to protect the interests and benefits of Hong Kong citizens. This is the most significant political role that the judiciary exercises. However, the Basic Law of Hong Kong also states that “National People’s Congress authorizes the HKSAR to exercise a high degree of autonomy and enjoy executive, legislative and independent judicial power, including that of final adjudication, in accordance with the provisions of this Law.”Footnote37 The Basic Law also defines the supremacy of the National People’s Congress over the other government bodies in Hong Kong, and this article, of course, restricts the independent judicial power. This relationship between the Hong Kong judiciary and the National People’s Congress becomes apparent when the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress interprets the Basic Law. The judiciary in common law is normally responsible for interpreting and enforcing the laws; however, article 158 of the Basic Law states that “the power of interpretation of the Basic Law shall be vested in the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress” and “the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress shall authorize the courts of the HKSAR to interpret on their own, in adjudicating cases, the provision of the Basic Law which are within the limits of the autonomy of the Region.”Footnote38 Zhang Xiaoming advocated that “an objection is still raised to this law and it is claimed that the judiciary in Hong Kong must have the right to reject the relevant interpretations and decisions that the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress made; however, it is totally illegal and disrespectful to the power enjoyed by the Central Government according to the law.”Footnote39

Maintaining a high level of autonomy in Hong Kong is the key to the conflict between the concept of the “rule of law” in Mainland China and Hong Kong following the introduction of the promotion of the “rule of law” and the rise of the Occupy Central Movement in 2014. Based on the definition that this paper provides, Xi’s concept of “rule of law” compromises three components: 1) standardizing the law, 2) centralizing power, and 2) stabilizing society. Therefore, Xi repeatedly claimed that the practice of the “One Country Two Systems” principle shall be guaranteed by law and that the interests of Hong Kong and Macao shall be protected by law in order to standardize the recognition of Hong Kong’s political system by legal means, as well as emphasizing “One Country” as a presupposition for centralizing power in the CCP. Additionally, Xi mentioned that the “rule of law” is an important foundation for Hong Kong’s long-term prosperity and stabilityFootnote40 This claim aimed to clarify the CCP’s attitude toward Hong Kong and also stabilize Hong Kong’s circumstances. Although the CCP repeatedly claimed the importance of the law or the “rule of law” for Hong Kong’s governance, the conception of these diverged from the Hong Kong citizens’ desires. They strongly seek a rule of law which has a strong correlative relationship with political freedom.

When the Occupy Central movement arose, the People’s Daily commented that “in order to achieve the healthy development of democratic politics in Hong Kong, we must follow the law and defend the core value of the ‘rule of law.’ If we don’t follow the law, the society in Hong Kong will be in chaos.”Footnote41 The Basic Law states that the Central Government has a right to determine how much autonomy Hong Kong keeps; therefore, Hong Kong citizens, who crave full autonomy, cannot enhance their freedom in Hong Kong. Their movement only leads the Central Government to clamp down on people’s freedom in Hong Kong at present. The more intense the movement becomes, the more control the Central Government will exert. However, it is not always possible for the Central Government to strengthen its rule over Hong Kong. The Central Government and the CCP are also restricted by the law and proceed according to the law when tightening its rule over Hong Kong.

A case where a demand by the Central Government and the CCP was restricted by the law was the unconstitutional judgment of the High Court regarding the Prohibition of Face Covering Regulation. Carrie Lam invoked colonial-era emergency powers for the first time in more than half a century and enacted a new regulation banning people from covering their faces at unlawful and unauthorized assemblies as well as riots under this legislation from October 5 2019, because she recognized that the current situation in Hong Kong had given rise to a state of serious public dangerFootnote42 This decision was strongly supported by the Central Government and the People’s Daily also commented that “enacting the regulation protects the ‘rule of law’ in Hong Kong and keeps their peace.”Footnote43 However, the High Court ruled the regulation unconstitutional. It is unclear why the High Court made this decision but it can be presumed that the High Court did not attempt to dispute with the government of Hong Kong or the Central Government and support the anti-China movement, but that the judiciary of Hong Kong executed their right based on the Basic Law to regulate the power of the Chief Executive of Hong Kong and tacitly restrict the CCP’s authority and control over Hong Kong. The judiciary of Hong Kong, as a result, secured Hong Kong citizens’ interests and benefits, based on a similar logic to the CCP’s promotion of the “rule of law” in Mainland China; however, the CCP understood that this decision violated the “One Country Two Systems” principle so they could not ignore it.

The CCP, of course, strongly resisted this, the People’s Daily reported that “the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress can make a decision about whether the law of HKSAR is appropriate, based on the Basic Law. In the past few months, the behavior of the judiciary of Hong Kong was considered problematic and was recognized to be ignoring illegal activities.”Footnote44 Han Zheng, head of the Central Leading Group for Hong Kong and Macao Affairs, suggested to Carrie Lam that the administrative body, legislature, and judiciary of Hong Kong should cooperate with each other. This meant that the CCP again strongly denied the separation of power and an independent judiciary in Hong Kong. Moreover, enacting the Hong Kong National Security Law strengthened the control over the judiciary of Hong Kong. The conflict between Mainland China and Hong Kong can assume the aspect of a legal war. As long as the Basic Law functions, the more intense the anti-China movement becomes, the faster will be the transition from enjoying a high level of autonomy to accepting the “rule of law” with Chinese characteristics in Hong Kong.

5 Conclusion

The conflict between Mainland China and Hong Kong regarding the issue of how much autonomy Hong Kong would retain is increasingly intensifying, especially after the Occupy Central Movement arose in 2014. This paper examines how the CCP’s policy toward Hong Kong was determined and how Xi Jinping’s domestic policy influenced the CCP’s control over Hong Kong. First, the analysis illustrates the components of the “rule of law” with Chinese characteristics, especially under Xi’s government. Compared to Hu Jintao’s era, Xi’s government is attempting to centralize power in the hands of the central government and stabilize the rule and laws, both to resolve the problems of decentralization. Although Xi’s government encourages the “rule of law” as one of the most important national policies, the status of the legal and judicial apparatus has not been upgraded. Instead, Xi focuses on social stability and has upgraded the status of the public security apparatus, although this does not mean that Xi’s government prefers to control by force rather than regulate by legal means. Xi’s government aimed to introduce laws to define and strengthen the CCP’s authority over society. Therefore, this paper considers that the “rule of law” policy under Xi’s government comprises 1) standardizing the law, 2) centralizing power, and 3) stabilizing society.

The second analysis revealed the personal affairs and organizational structure in the Central Coordinating and Leading Group on Hong Kong and Macao Affairs (The Group). The Group can be recognized as a highly important organization among those in the Central Committee of the CCP, as a member of the Political Bureau Standing Committee is appointed as its head and a member of the Political Bureau is appointed as its deputy. After Xi’s government came to power in 2013, the appointment of the organizations related to national and public security, as members of the Coordinating Group, occurred. Based on the first analysis, the appointment of the national and public security apparatus to the Group implies that the CCP recognizes Hong Kong affairs as a social security issue, and needs to deal with these affairs by the “rule of law” policy.

The third analysis examined the reflection and rhetoric of the CCP’s “rule of law” toward Hong Kong, based on the politicians’ discourses. The CCP’s control over Hong Kong gradually strengthened in the middle of Hu’s era. Xi’s government, at the beginning, inherited Hu’s Hong Kong policy and obviously strengthened its control over Hong Kong, especially after the Occupy Central Movement intensifies in 2014 to stabilize Hong Kong’s circumstances. At that time, Xi’s government used the “rule of law” rhetoric to tighten the high level of autonomy over Hong Kong. However, as long as the CCP claims to promote the “rule of law,” the CCP is also restricted by law. Therefore, the judiciary of Hong Kong could enjoy their right to make an unconstitutional judgment based on the Basic Law to secure Hong Kong citizens’ rights and interests, even though the CCP aggressively resisted this. The CCP, moreover, stressed the importance of the Basic Law and the sovereignty of China over Hong Kong. Finally, enacting the Hong Kong National Security Law tightened the control over the judiciary of Hong Kong.

According to the analysis, this paper shows that Mainland China is strengthening its control over Hong Kong by claiming the “rule of law,” and the components of the “rule of law” policy has become a tool for the CCP to tighten its rule over Hong Kong. The judiciary of Hong Kong has retained a certain amount of independence; however, as long as the Basic Law and the Hong Kong National Security Law are effective, the anti-China movement is intensifying, and the faster will be the transition from enjoying a high level of autonomy to accepting the “rule of law” with Chinese characteristic in Hong Kong.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Naito Hiroko

Hiroko Naito is Researcher at East Asian Studies Group, Area Studies Center, Institute of Developing Economies, Japan External Trade Organization. She received her PhD from Keio University Graduate School of Media and Governance. She was a visiting fellow of Harvard- Yenching Institute from 2014 to 2016. Her area of expertise includes Comparative Politics and Area Studies (Contemporary Chinese Politics). Her research focuses on the “rule of law” under the authoritarian regime, and especially examines the Chinese Communist Party’s leadership over the People’s Court which is a judicial branch in China. Her recent publication is Hiroko Naito and Macikenaite Vida eds., (2020) State Capacity Building in Contemporary Chinese Politics, Springer.

Notes

1 The Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. “Full Text of the Constitution and the Basic Law.” The Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. Accessed June 29 2020. https://www.basiclaw.gov.hk/en/basiclawtext/chapter_1.html.

2 Ibid.

3 “Dang de Shijiu Jie Si Zhong Quanhui ‘Jueding’ (Quanwen),” [A Communique of the Fourth Plenary Session of the 19th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (Full Text),] Huanqiu NET, November 5 2019. Accessed June 29 2020. https://china.huanqiu.com/article/9CaKrnKnC4J.

4 “Guanyu ‘Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Xianggang Tebie Xingzhengqu Weihu Guojia Anquanfa (Caoan)’ de Shuoming,” [Explanation about the Draft Law on Safeguarding National Security in HKSAR], People’s Daily NET, June 21,2020. Accessed June 30 2020. http://npc.people.com.cn/n1/2020/0621/c14576-31754045.html.; “NPCSC Releases Some Details of Draft Hong Kong National Security Law, But Withholds Information on Criminal Provisions.” NPC Observer-Covering the National People’s Congress and its Standing Committee-. Accessed June 30 2020. https://npcobserver.com/2020/06/20/npcsc-releases-some-details-of-the-draft-hong-kong-national-security-law-but-withholds-information-on-criminal-provisions/.

5 Sum Lok-kei and Gary Cheung. 2020. “National Security Law: Hong Kong Leader Carrie Lam Vows to Hand-pick Judges for Cases Brought under New Legislation.” South China Morning Post, June 23. Accessed June 30 2020. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3090218/national-security-law-hong-kong-leader-carrie-lam-rejects.

6 Kurata,” Hong Kong Kiki no Shinsou”; Chan, “A Storm of Unprecedented Ferocity”; Chan “Xianggang Shehui Zhili”; Chen “Xianggang Shehui Zhili yu Zhengzhi Zhuangxing Mianlin de Tiaozhan”.

7 Hui, “Beijing’s Hard and Soft Repression in Hong Kong”; Endo “Beichu Bouekisensou no Uragawa”; Kwong “Political Repression in a Sub-national Hybrid Regime”.

8 Yep “Negotiation Autonomy in Greater China”; Hiroe “Hong Kong Kihonhou Kaishakuken no Kenkyu”.

9 Young and Ghai “Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal”; Hiroe “Hong Kong ni okeru Houchi, Houseido oyobi Saiban Seido”.

10 Zhu “Beijing’s ‘Rule of Law’ Strategy for Governing Hong Kong”.

11 Michael Forsythe Michael, 2017. “Independent Judiciary, and Reformers Wince.” The New York Times, January 18 2017.Accessed August 4 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/18/world/asia/china-chief-justice-courts-zhou-qiang.html

12 Wang “Tying the Autocrat’s Hands”: 2.

13 Xinhua, “Full Text: White Paper on Judicial Reform in China,” China Daily, October 9 2012. Accessed August 11,2020. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2012-10/09/content_15803827_3.htm.

14 “Zhongguo Gongchandang Dishibajie Zhongyang Weiyuanhui Disanci Quanti Huiyi Gongbao,” [Gazette of the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of China], Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Zhongyang Renmin Zhengfu, November 12 2013. Accessed October 18, 2020. http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2013-11/12/content_2525960.htm.

15 Ibid.

16 World Justice Project. “Civil Justice (Factor 7).” World Justice Project. Accessed August 5 2020. https://worldjusticeproject.org/our-work/wjp-rule-law-index/wjp-rule-law-index-2017%E2%80%932018/factors-rule-law/civil-justice-factor-7.

17 “Zhonggong Zhongyang Guanyu Quanmian Tuijin Yifa Zhiguo Ruogan Zhongda Wenti de Jueding,” [Decision of the CPC Central Committee on Major Issues Pertaining to Comprehensively Promoting the “Rule of Law”], CPC News NET, October 29 2014. Accessed October 18 2020. http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2014/1029/c64387-25927606.html.

18 Guide cases can be checked at “Cases in Chinese Courts,” chinacourt.org. Accessed August 13 2020. https://www.chinacourt.org/article/subjectdetail/type/more/id/MzAwNEiqNACSYAAA.shtml.

19 Wang and Minzer, “The Rise of the Chinese Security State”.

20 “Zhonggong ZHongyang Guanyu Quanmian Shenghua Gaige Ruogan Zhongda Wenti de Jueding,” [The Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Some Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening the Reform], The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China NET, November 15 2013. Accessed November 27 2020.http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2013-11/15/content_2528179.htm.

21 “Xi Jinping: Jianchi Zongti Guojia Anquanguan Zou Zhongguo Tese Guojia Anquan Daolu,” [Xi Jinping: Hold the Overall National Security Outlook, Go to the National Security Road with Chinese Characteristics], CPC News NET, April 16 2014. Accessed November 27 2020. http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2014/0416/c64094-24900492.html.

22 Svolik, “The Politics of Authoritarian Rule.”

23 Kurata, “Chugoku Henkango no Hong Kong”: 251–252.

24 Kamo, “Naze Hong Kong Anzenho wo Rippou Surunoka”.

25 “Han Zheng Tingqu Xianggang Tebie Xingzhengqu Xingzheng Changguan Lin Zheng Yuee Dui Tequ Weihu Guojia Anquan Lifa Wenti de Yijian,” [Han Zheng Listening to the Opinion of Carri Lam, Chief Executive of Hong Kong about the Problem of Hong Kong’s National Security Law,] Xinhua NET, June 3 2020. Accessed August 17 2020. http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/leaders/2020-06/03/c_1126070383.htm.

26 Ibid.

27 Gary Cheung, “From Deng Xiaoping to Geoffrey Ma: Key movers and shakers on Hong Kong’s Basic Law,” South China Morning Post, September 16 2015. Accessed August 21 2020. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/1858740/deng-xiaoping-geoffrey-ma-key-movers-and-shakers-hong-kongs.

28 “Wen Jiabao Qiangdiao: Zhongyang Hui Yange Anzhao Xianggang Jibenfa Guiding Banshi,” [Wen Jiabao Stressed: Central Government Should Strictly Refer to Basic Law of Hong Kong,] China NET, March 14 2015. Accessed August 21.2020. http://www.china.com.cn/zhuanti2005/txt/2005-03/14/content_5810544.htm; “Wen Jiabao Huijian Zeng Yi quan,” [Wen Jiabao Meet Tsang Yam-Kuen.] Guangming Daily, December 29 2006. Accessed August 21,2020. https://epaper.gmw.cn/gmrb/html/2011-12/27/nw.D110000gmrb_20111227_4-02.htm?div=−1.

29 “Wen Jiabao Zai Shijie Renda Wuci Huiyi Jizhe Zhaodaihui Shang Dawen Neirong,” [Wen Jiabao’s Answer for a Press Conference at the National People’s Congress,] China News Net, March 16 2007. Accessed August 17,2020. http://www.chinanews.com/gn/news/2007/03-16/893627.shtml.

30 “Wu Bangguo Zai Jinian Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Xianggang Tebie Xingzhengqu Jibenfa Shishi Shizhounian Zuotanshang de Jianghua,” [Wu Bangguo’s Speech at 10th Anniversary of Basic Law of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region,] Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office of the State Council, Accessed August 21 2020. https://www.hmo.gov.cn/xwzx/zwyw/201711/t20171107_605.html.

31 Colleen Lee, “Xi Jinping backs Hong Kong chief executive Leung Chun-ying in Beijing.” South China Morning Post, December 21 2012. Accessed August 21 2020. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/article/1109441/xi-jinping-backs-hong-kong-chief-executive-leung-chun-ying-beijing; “Xi Jinping Huijian Liang Zhenying,” [Xi Jinping met Leung Chun-ying,] Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office of the State Council, Accessed August 21,2020. https://www.hmo.gov.cn/xwzx/zwyw/201711/t20171107_738.html.

32 “Zhonglianban Zhuren: Zhongyang Dui Gnang Zhengce Bu Cunzai Shoujin Bu Shoujin,“ [Director of Hong Kong Liaison Office: There is No Tightening of the Central Government’s Policy Toward Hong Kong,] Youth.cn NET, January 10 2013. Accessed August 21,2020. http://news.youth.cn/jsxw/201301/t20130110_2795587.htm.

33 “Xi Jinping: Zhongguo Gongchandang Ren de Chuxin he Shiming Jiushi Wei Zhongguorenmin Mou Xinfu Wei Zhonghua Minzu Mou Fuxing”, [Xi Jinping: To Seek the Happiness of the Chinese People is the Mission of the Communist Party of China,] Gongchangdangyuan NET, October 18 2017. Accessed August 22 2020. http://www.12371.cn/2017/10/18/ARTI1508294035259919.shtml; “Zhonglianban Zhuren: Xianggang Shi Zhongguo Meng De Zhongyao Yuansu,” [Director of Hong Kong Liaison Office: Hong Kong is the Most Important Element for Realizing China Dream,] China News NET, February 22 2013. Accessed August 22 2020. http://www.chinanews.com/shipin/cnstv/2013/02-22/news176759.shtml.

34 “Xi Jinping Huijian Liang Zhenying,” [Xi Jinping met Leung Chun-ying,] People’s Daily Net, December 21 2012. Accessed August 22 2020. http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2012/1221/c64094-19967392.html.

35 Chun Han Wong and Jeremy Page. “For China’s Xi, the Hong Kong Crisis Is Personal.” Wall Street Journal, September 27 2019. Accessed August 22 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/for-chinas-xi-the-hong-kong-crisis-is-personal-11569613304.

36 The Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. “Full Text of the Constitution and the Basic Law.” The Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. Accessed June 29 2020. https://www.basiclaw.gov.hk/en/basiclawtext/chapter_1.html.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 “Zhang Xiaoming Jiedu Gang Ao Gongzuo Zhongdian,” [Zhang Xiaoming Explained the Significant Point of Hong Kong and Macao Affairs,] People’s Daily NET, November 23 2020. Accessed August 22 2020. http://hm.people.com.cn/n/2012/1123/c42272-19677066.html.

40 “Xi Jinping Huijian Liang Zhenying,” [Xi Jinping met Leung Chun-ying,] China News NET, November 9 2014. Accessed August 24 2020. http://www.chinanews.com/ga/2014/11-09/6763899.shtml.

41 “Jianding Guanqie ‘Sange Jianding Buyi’,” [Resolutely Implement “Three Unwavering”,] People’s Daily NET, October 2 2014. Accessed October 21 2020. http://opinion.people.com.cn/n/2014/1002/c1003-25772358.html.

42 “Gov’t Introduces Anti-Mask Law.” Government News NET, October 4 2019. Accessed August 24 2020. https://www.news.gov.hk/eng/2019/10/20191004/20191004_165505_551.html.

43 “Jinzhi Mengmian, Zhibao Zhiluan,” [Forbid Wearing Mask and Stop Violence,] People’s Daily, October 5 2019. Accessed August 24 2020.

44 “Chuou ha Hongkong ga Konnan ni Uchikacu no wo Sasaeru Mottomo Kyokouna Tate” [The Central Government is the Strongest Backing for Hong Kong to Overcome Difficulties] Renminwang (Japanese Edition), November 20 2019. Accessed August 24 2020. http://j.people.com.cn/n3/2019/1120/c94474-9633938-2.html; “Hongkong Kousai no 18nichi no Hanketsu ni Zenjindai Jiaomu Iinkai Housei Katsudou Iinkai ga Danwa” [Comment on the Judgment of High Court of Hong Kong], Renminwang (Japanese Edition), November 19 2019. Accessed August 24 2020. http://j.people.com.cn/n3/2019/1119/c94474-9633673.html.

Bibliography

- Chan, J. “A Storm of Unprecedented Ferocity: The Shrinking Space of the Right to Political Participation, Peaceful Demonstration and Judicial Independence in Hong Kong.” International Journal of Constitutional Law 16, no. 2 (2018): 373–388. doi:10.1093/icon/moy053.

- Chen, D. “Xianggang Shehui Zhili Yu Zhengzhi Zhuanxing Mianlin De Tiaozhan.” [ Governing Society in Hong Kong and Challenges that Political Transformation Faces.] Wenhua Zongheng 1 (2014): 36–40.

- Endo, H. Beichu Bouekisensou No Uragawa: Higashiajia No Chikaku Hendou Wo Yomitoku. [ Background of US-China Trade Wars: Understanding Diastrophism in East Asia.]. Tokyo: Mainichi Shimbun Publishing, 2019.

- Hiroe, N. Hongkong Kihonhou No Kenkyu: ‘Ikkoku Ryousei’ Ni Okeru Kaishyakuken to Saiban Kankatsu Wo Chyushin Ni. [ Study of Hong Kong Basic Law: Focus on Interpretation and Jurisdiction under One Country and Two System Principle.]. Tokyo: Seibundoh, 2005.

- Hiroe, N. Hongkong Kihonhou Kaishyakuken No Kenkyu. [ Study of Interpretation of Hong Kong Basic Law.]. Tokyo: Shinzansha, 2018.

- Hiroe, N. “Hongkong Ni Okeru Houchi, Houseido Oyobi Saiban Seido.” [ Rule of Law, Legal System and Court System in Hong Kong.] In Hongkong No Kako, Genzai, Mirai: Higashi Ajia No Furonteia, [ Hong Kong’s Past, Present and Future,], edited by T. Kurata, 67–87. Tokyo: Bensei Shuppan, 2019.

- Hui, V. T.-B. “Beijing’s Hard and Soft Repression in Hong Kong.” Orbis 64, no. 2 (2020): 289–311. doi:10.1016/j.orbis.2020.02.010.

- Kamo, T., “Naze, Hong Kong Anzenho Wo Rippou Surunoka.” [ Why is Hong Kong National Security Law Legislated], Perspective on Chinese Politics June 15, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2020. https://www.kazankai.org/politics_list.php?no=4.

- Kurata, T. Chugoku Henkanggo No Hongkong: “Chisana Reisen” to Ikkoku Ryouseido No Tenkai. [ After the Returnee of Hong Kong to Mainland China: “Small Clod War” and the Development of One Country Two System Principle]. Nagoya: Nagoya University Press, 2009.

- Kurata, T., and A. Kurata, eds. Hong Kong Kiki No Shinsou: ‘Toubouhan Jyourei’ Kaisei Mondai to ‘Ikkoku Ryouseido’ No Yukue. [ Depth of Hong Kong Crisis: Issues of “Hong Kong Extradition Bill” and “One Country Two System.]. Tokyo: Tokyo Gaikokugo Daigaku Shuppankai, 2019.

- Kwong, Y.-B. “Political Repression in a Sub-national Hybrid Regime: The PRC’s Governing Strategies in Hong Kong.” Contemporary Politics 28, no. 4 (2018): 361–378. doi:10.1080/13569775.2017.1423530.

- Qi, P. “Zhonggong 18Da Yilai Xijinping “Yifa Zhigang” De Xin Linian, Xin Lunshu Chutan.” [ Preliminary Research about New Idea and New Perspective of Xi Jinping’s Governance over Hong Kong after the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China.] Dangshi Yanjiu Yu Jiaoxue 4 (2016): 4–16.

- Qi, P. “Jianchi Liangge Jibendian ‘Jianjue Buyi’ ‘Quanmian Zhunbei’: Shilun Xijinping Guanyu ‘Yiguo Liangzhi’ Zhi ‘Xianggang Zhili’ De ‘Dingceng Sheji’ He ‘Dixian Siwei.” [ Upholding Two Basis Points of “Unswervingly” and “Fully and Faithfully” Pursuing “One Country, Two System”: On Xi Jinping’s “Top-level Design” and “Bottom-line Thinking” in the Governance Hong Kong.] GangAo Yanjiu 4 (2017): 12–23.

- Svolik, M. W. The Politics of Authoritarian Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Wang, Y. Tying the Autocrat’s Hands: The Rise of the Rule of Law in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Wang, Y., and C. Minzer. “The Rise of the Chinese Security State.” The China Quarterly 222 (2015): 339–359. doi:10.1017/S0305741015000430.

- Yep, R. Negotiating Autonomy in Greater China: Hong Kong and Its Sovereign before and after 1997. Kopenhagen: Nordic Inst of Asia Studies, 2013.

- Young, S. N. M., and Y. Ghai, eds. Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal: The Development of the Law in China’s Hong Kong. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Zhu, H. “Beijing’s ‘Rule of Law’ Strategy for Governing Hong Kong: Legalization without Democratization.” China Perspectives 1, no. 1 (2019): 23–33. doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.8686.