ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to observe how China’s exercise of economic statecraft changed with the growth of its economic power. While there is a widely accepted consensus that the distribution of economic capabilities has changed in favor of China over the recent decades, it still needs to be examined what effect this has had on China’s actual bargaining behavior within that new power structure. The analysis is built on the framework of complex interdependence, arguing that the expansion of China’s economic capabilities has led to greater levels of interdependence with other countries and has also tilted the power asymmetries in favor of China. The analysis operationalizes the change in China’s exercise of economic statecraft, i.e., the use of economic tools in pursuit of national objectives abroad, as a foreign policy change and observes the quantitative change (how intensively the same economic tools were utilized), the qualitative change (what means specifically were employed) and the change in goals (what national objectives these economic means were aimed at achieving). The analysis demonstrates that China used the same economic tools more intensively as a result of higher capacity. Also, it turned to unilateral economic sanctions more often since 2007. Further, China embraced multilateralism in the exercise of its economic statecraft under the current leadership. The paper concludes that in the interdependent world, a very inertial process of power asymmetry shift to China’s favor has started and China is likely to be increasingly able to translate its economic power into actual influence.

1 Introduction

China’s rise into the ranks of the world’s major powers has stirred a debate worldwide on how the country, led by the Communist Party of China (CCP), would utilize its expanded capabilities in its interactions with other countries and, as a result, what the effects of it would be on the international system. The fundamental change underlying China’s accent to a major power has been the tremendous growth of its economic capabilities. The World Bank estimates that since China began opening-up reform in 1978, its GDP growth has averaged nearly 10% a year. Last year, China was reported to rank first in terms of the size of the economy on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis, value-added manufacturing, merchandise trade, and in terms of foreign exchange reserves it heldFootnote1 As a result, its military and diplomatic power has also expanded greatly, drawing the attention of the world. While Chinese leaders have continuously adhered to their claim that increasing capabilities of the country do not change its path of peaceful development, realists like Mearsheimer argue that China’s rise cannot be peacefulFootnote2 Their assumption is that large capabilities of China would by default translate into an attempt to revise the existing international order.

Conceptually, there are two key elements at the core of this debate on the impact that China’s rise is likely to have on China’s interactions with other states and the international system in general – the structure and the process of the interactions between states. The structure refers to the distribution of capabilities among states, and the process – to the allocative and bargaining behavior of a state within that power structureFootnote3 This distinction between structure and process captures the difficulty in defining power of a country. On the one hand, it can refer to the initial power resources that provide a state with potential ability; and on the other hand, power can define the state’s actual influence over the outcomesFootnote4 That is to say, in terms of structure, China indeed has more power – larger economic capabilities or resources that could increase its potential ability. At the same time, when it comes to the process, China’s power still needs to be defined as it is not exactly clear how it uses those resources to shape the outcome of interaction with other states. Importantly, as Keohane and Nye note, the advantage in power resources does not automatically mean that it will result in a similar pattern of control over outcomes. “Political bargaining is usually a means of translating potential into effects, and a lot is often lost in the translation.”Footnote5

This paper inquires how China has used economic resources available to it to affect the behavior of other states, i.e., how it has sought to translate its potential ability into actual outcomes. Limiting the scope of the inquiry here to the exercise of economic tools only, the analysis focuses on China’s exercise of economic statecraft – the use of economic instruments to pursue broader national objectives abroad. That is, the purpose of this analysis is to observe how China’s exercise of economic statecraft has changed as the country’s economic power expanded. While there is a widely accepted consensus on the changes in the system, i.e., that the distribution of economic capabilities has changed in favor of China over the recent decades, it still needs to be examined what effect this has had on the process, i.e., on China’s actual bargaining behavior within that new power structure.

For that purpose, the analysis below observes China’s use of economic tools in its foreign policy. To capture and define the change in this practice over the time, economic statecraft is broadly defined as foreign policy action and thus analytical framework defining foreign policy change as suggested by HermannFootnote6 is applied to operationalize the changes in China’s exercise of economic statecraft. Specifically, the analysis observes qualitative change – what economic tools China utilized, the quantitative change, or how the intensity of the use of specific tools changed, and the change in goals, or what national objectives these economic tools targeted. Such analysis of China’s exercise of economic statecraft enables us to capture how China has used its expanded economic power resources to achieve the actual influence over other states.

2 China’s economic power in an interdependent world

There are several direct effects that the growth of China’s economic capabilities has had on China’s interactions with other states, and, in turn, could possibly facilitate a change in China’s exercise of its economic statecraft. First, it has led to greater levels of interdependence between China and other countries. As economic capabilities of China’s both – the state and the private – sectors expanded greatly, China’s channels of contact with other states increased both in terms of number and intensity. For example, China’s foreign aid and outward foreign direct investment (FDI) flows grew significantly, as further below indicate. The number of outbound tourists to different countries has exploded from 4.5 million in 2000 to 150 million outbound travel departures in 2018, with an average annual double-digit growth of 16%, making China the largest source market in the world already in 2012Footnote7 Similarly, the number of Chinese students studying abroad grew from 179.8 thousands in 2008 to 662.1 thousands in 2018Footnote8 These actors, according to Keohane and Nye, “are important not only because of their activities in pursuit of their own interests, but also because they act as transmission belts, making government policies in various countries more sensitive to one another.”Footnote9 And China used this greater interdependence, e.g., the influx of tourists from the mainland China to Taiwan or Chinese students in Australia, in its relations with them in other issue areas to achieve its foreign policy objectives. And this confirms that these relatively new transactions or channels of contact between China and other countries signify greater interdependence between them rather than mere interconnectednessFootnote10

Second, this trend has also tilted the power asymmetries in favor of China in most of its interactions with other states. And it is exactly the asymmetries in an interdependence relationship that are likely to provide sources of influence for states in their dealings with each otherFootnote11 There is no doubt, that the economic resources China holds now provide it with a greater ability to “get others to do something they otherwise would not do (and at an acceptable cost to the actor [i.e., China]),”Footnote12 while the degree of the asymmetry varies depending on the country. Covid-19 pandemic exposed this asymmetry more clearly than ever before. As The New York Times reported in March 2020, China made half of the world’s masks even before the coronavirus emerged there, and later some countries like France called for reducing their dependency on China in the supply of this critical item. But even aside from the current worldwide health crisis some countries are in a significantly asymmetrical relationship with China. E.g., China has been Australia’s largest trading partner for more than a decade now and recently it accounts for nearly a third of Australia’s exportsFootnote13 Supply chains of many European countries are also dependent on China.

That is, China’s potential ability to influence other countries through the use of economic tools or to employ them in pursuit of national objectives is higher than before. Indeed, China’s economic statecraft toolbox is fuller and potentially more effective as a result of the increased economic power of the country. Nonetheless, as already explained above, power can be conceived in terms of the initial power resources an actor holds, but also in terms of the actor’s actual influence over the outcomes as a result of the political bargaining process. Having established that China’s ability to influence others is more significant as a result of larger available economic resources and higher interdependence, the major focus of the analysis below is on how China has been using those economic tools to actually influence the outcomes of its relations with other states, i.e., how China has been exercising its economic statecraft.

3 Capturing the change in the exercise of economic statecraft

To capture the changes in China’s exercise of its economic statecraft, it is necessary to first operationalize it. Considering that economic statecraft is the use of economic tools in pursuit of national objectives abroad, it can broadly be defined as a foreign policy action. Thus, put very generally for the purpose of analysis, the main aim here is to capture the change in Chinese foreign policy.

The theoretical challenge, and also that observed empirically in the literature on China, is to define the degree of foreign policy change. Hermann suggests a workable frameworkFootnote14, which is greatly functional in unpacking China’ exercise of economic statecraft. He places foreign policy changes along a continuum indicating the magnitude of the shift from minor adjustment to fundamental changes as follows:

(1)Adjustment changes. Changes occur in the level of effort (greater or lesser) and/or in the scope of recipients, i.e. the intensity of the use of specific means. The means (what is done, how it is done) and the purposes remain unchanged.

(2)Program changes. Changes are made in the methods or means by which the goal or problem is addressed. While adjustment changes tend to be quantitative, program changes are qualitative and involve new instruments of statecraft. The means change, but the purposes for which it is done remain unchanged.

(3)Problem/goal changes. The initial problem or goal that the policy addresses is replaced or simply relinquished. That is, the foreign policy purposes themselves are replaced.

(4)International orientation changes. That is the most extreme form of foreign policy change redirecting the actor’s entire orientation toward world affairs. It involves a basic shift in the actor’s international role and activities rather than the actor’s approach to a single issue or specific set of other actors, as in the case with lesser forms of change. Typically, this involves shifts in alignment with other nationsFootnote15

Hermann defines the last three forms of foreign policy change – change in means (program), ends (goal) or overall orientation – as major foreign policy redirection, while the quantitative change in effort is considered to be an adjustment.

Applying this framework to measure the change in China’s exercise of its economic statecraft enables one to penetrate the level at which that change is taking place, and thus evaluate how China is translating its expanded economic power resources into actual influence over the outcomes of interaction with other states. Hardly any change in China’s international orientation can be observed during the decades of economic reform; thus, the key variables to be observed then are the means – the specific economic tools – that China chooses in pursuit of national policy goalsFootnote16 abroad, the intensity of their use, and the national goals that are addressed through these means.

4 China’s exercise of economic statecraft

As China’s economic power expanded, it gained capabilities to reward or punish other states with economic rather than any other means. There might be military, economic, political, or cultural capabilities, which are then characterized by mass (preponderance and concentration), relevance (the degree to which that capability can be brought to bear on the issue), impact (the degree to which an opponent feels an injury or inducement applied to it through a capability), irresistibility (the extent to which a capability cannot be countered or offset), and sustainability (whether the expenditure of time and national effort works to reinforce capabilities or to exhaust them)Footnote17 China’s economic capabilities certainly expanded in terms of mass. This enabled massive packages of economic aid or other official finance flows to countries often short of alternative sources of financing, also increasing amounts of state-controlled FDI by Chinese companies overseas. This, in turn, boosted the relevance and irresistibility of China’s economic capabilities. And as other states became more dependent on Chinese economy, the impact of its economic capabilities also increased to an unprecedented level. These trends made economic means efficient and thus attractive to Chinese policymakers more than any other type of tools when pursuing its national goals abroad.

Indeed, China has actively used economic instruments abroad – development finance, foreign aid, outward FDI and sanctions – to achieve a broad variety of its national goals. Importantly, these have not been limited to economic gaols, which differentiates economic statecraft from economic diplomacy, sometimes overlapping terms. Generally, economic diplomacy may be defined as those activities of a state that are aimed at protecting and promoting its own economic interests in the international environment. This is one of the ways that Chinese scholarship uses the term economic diplomacy (jingji waijiao). Yet, it does not include other but economic interests that states might pursue with economic tools in international arena, while economic tools can be used to gain political leverage over another state, international support, also to enforce specific norms, e.g. human rights, and other non-economic goals. Such broader agenda is incorporated into the term economic statecraft, which emphasizes instrumental use of economic means to achieve national strategic objectives. And this is what defines economic statecraft in this paperFootnote18

Until a seminal work on economic statecraft by David Baldwin in 1985, economics had long been considered to be “not a very useful instrument” of politicsFootnote19, with many scholars suggesting that military force is a more fundamental base of power, at least in international politicsFootnote20 Baldwin differentiates between positive and negative sanctions, or economic incentives and economic sanctions, respectively, to show how economic instruments might become effective tools for states to pursue their broader national objectives and turn away from military meansFootnote21 Since then, empirical studies of economic statecraft have mostly centered around negative means, with the literature on economic inducements surprisingly scantFootnote22 Nonetheless, scholarship on Chinese economic statecraft comes in stark contrast. It brings the exercise of economic statecraft back into the academic inquiry, focusing mainly on positive tools to pursue specific national goals. Pardo presents BRI as a tool of Chinese economic statecraftFootnote23 Urdinez et al. survey the correlation between weakening US influence in Latin America and China’s strengthening economic statecraft by observing the investments made by Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), bank loans, and manufacturing exportsFootnote24 Similarly, Morgan observes trade, FDI, and aid to show the relationship between China’s economic statecraft and its soft power in AfricaFootnote25

The analysis below offers a comprehensive survey of China’s exercise of economic statecraft over the years of economic reform.

4.1 Positive economic instruments

Existing literature on China suggests that the use of economic inducements rather than sanctions to pursue foreign policy goals has been relatively consistent practice throughout the successive leaderships since Mao Zedong eraFootnote26 And the toolbox of economic incentives has been relatively full with a variety of instruments, even if their use at various periods of time differed. Having started with allocation of foreign aid to less developed countries in Africa as early as mid-1950s, since around 2000, China utilized economic instruments increasingly more, and developed more sophisticated tools, often merging the elements of foreign aid with commercial activities. It has also expanded their applications from bilateral to multilateral settings.

As China’s economic capabilities expanded in the course of economic reforms, the intensity of the use of economic instruments as a part of its economic statecraft has increased multiple times. At different points in time, the goals these economic instruments served in China’s official strategy might have been different, but the overall set of national goals has persisted. It is beyond the scope of this paper to analyze each economic instrument employed by China, but the overview below presents the major tools; and the main trends in their use expose with more details the major changes that have occurred.

At the core, there has been foreign development finance, otherwise referred to as official development finance. It is difficult to equate China’s official development finance with the traditional practice of official development assistance (ODA) by other countries, but generally three financial instruments are considered to be China’s foreign aid – grants (foreign aid), interest-free loans and concessional (low, fixed interest) loans. Foreign aid grants and interest-free loans, the primary instruments until 1995, when concessional loans were introduced, are managed by the Ministry of Commerce and usually promote broad diplomatic objectives. The concessional loan programs, which are operated by China Eximbank, mix diplomacy, development, and business objectivesFootnote27 Alves argues that variety of forms of foreign aid provided by China since then have remained mostly the same, while only its volume, geographical patterns, and the internal mechanism have changed significantly since around 2002Footnote28

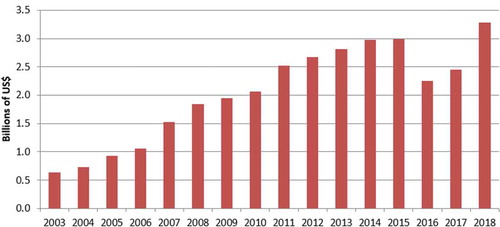

China’s reporting on its foreign aid has not been transparent, but the official statistics provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (see ) as well as independent estimatesFootnote29 indicate the same trend – China’s foreign aid has grown dramatically since early 2000s.

Figure 1. China’s official foreign aid expenditure, 2003–2018 (source: China Africa Research Initiative).Footnote30

Yet, a large proportion of China’s officially supported finance is not actually ODA. Of what China provides, only a relatively small share meets the definition of ODA, while other tools fall under a general category of “other official flows” – preferential export credits, market-rate export buyers’ credits, and commercial loans from Chinese banks, and strategic lines of credit to Chinese companies. Both China Eximbank and China Development Bank offer official loans at commercial ratesFootnote31

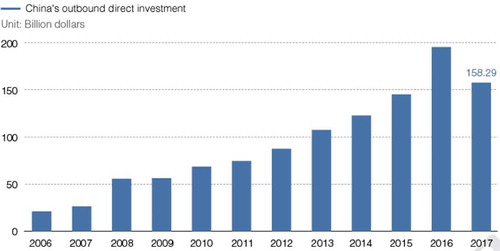

The practice of officially supported finance has served China’s domestic economic interests. These economic instruments have actively been used in the implementation of going global strategy, launched in 2001 and aimed at promoting Chinese companies overseas. Thus, the data on these financial instruments is often included as a part of statistics on China’s outward FDI, which has expanded beyond expectations since early 2000s ().

Figure 2. China’s outward FDI flows, 2006–2017 (source: Chinese Ministry of Commerce).Footnote32

In the case of Western countries, it would be difficult to argue that outward FDI is a tool of their economic statecraft, but it is exactly the case for China. Firmly regulating and guiding the investments of Chinese companies overseasFootnote33, China is able to utilize FDI as an important tool in pursuit of its national goals. This has been especially the case since 2001, after the going global strategy was launched. First, through formal regulations directing and controlling investment abroad activities and incentives to Chinese companies, the state has been able to secure natural resources, crucial for China’s economic development. Later, as China’s domestic development objectives expanded, the state directed its companies to invest in strategic sectors and technologies overseas. Next, it has been able to promote the rise of Chinese companies to the ranks of the world’s largest multinational corporationsFootnote34 Further, China utilizes or directs outward FDI to promote its soft powerFootnote35 and international image. Finally, outward FDI is used as a tool to provide incentives to other countries to follow China’s policy line, would it be recognition of TaiwanFootnote36 or consideration to China’s principles of noninterference.

Some of these objectives are said to be linked with China’s foreign aid too. First, in earlier years, it provided Chinese companies with a low-risk framework to advance their activities internationallyFootnote37 The importance China attached to it is indicated by the institutional structure – foreign aid department has long been under the Ministry of Commerce rather than the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. But for decades, foreign aid was a tool in China’s foreign policyFootnote38 Fuchs and Rudyak capture the motives behind China’s foreign aid: “the Chinese government uses aid as a foreign policy tool, which should help the country to create a favorable international environment for China’s development, support the country’s rise to global power status, influence global governance, and reward countries that abide by the One-China Policy. Moreover, aid has increasingly been used to promote trade with developing countries and loans are extended in exchange for natural resources.” There is also an element of mutual benefit, since research shows that poorer countries tend to receive more of Chinese foreign aidFootnote39 Some research also shows notable correlation between Chinese aid giving and the voting behavior of recipient countries in international organizations.

In March 2018, the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA) was established, marking the first significant change in its institutional structure of foreign aid allocation since mid-1990s. Aimed at tackling bureaucratic fragmentation of Chinese foreign aid administration, the restructuring is taken as a sign that development aid is at the forefront of Chinese policymakers’ agendaFootnote40

Further, before, often reluctant to do so, China now indicates its openness to multilateralism. CIDCA is due to facilitate more exchanges and other forms of cooperation with other donors, participating in more dialogs and international exchanges, such as UN or OECD meetings on development practicesFootnote41

CIDCA director Wang Xiaotao was quoted in an interview to China’s Central Television on March 3 2019 as saying that the agency’s major task is to serve China’s great power diplomacy and promote the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). It appears that much of China’s official financial flows, also outward FDI projects have been put under the umbrella of BRI. This signature project of President Xi is also defined by multiple objectives that to a large extent remain unchanged. China indeed remains committed to creating the international environment facilitating its domestic development. As OECD summarizes it, “China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) development strategy aims to build connectivity and co-operation across six main economic corridors encompassing China and: Mongolia and Russia; Eurasian countries; Central and West Asia; Pakistan; other countries of the Indian sub-continent; and Indochina.”Footnote42 That is exactly what is expected to open markets for China’s products in the long term and to alleviate industrial excess capacity in the short termFootnote43

While the scale of the project is unprecedented, infrastructure development, also the main focus of the BRI, has long been at the core of China’s economic statecraft. Already in 1967, it signed a 400 million USD loan agreement with Tanzania and Zambia to build the Tazara railway – a 1870 km railway linking a rich copper belt in Zambia to Dar Es Salam port in Tanzania – its first major infrastructure project on the African continent. All equipment and materials used by the thousands of Chinese technicians were shipped from China, the practice recently also characterizing China-supported infrastructure development projects overseas. Domestic financial and political constraints notwithstanding, Mao Zedong regarded the project as a unique opportunity to raise China’s profile on the continentFootnote44 In the pre-reform China, African leaders often turned to China for financing the projects that Western donors would be reluctant to finance. Under the BRI, China-led projects finance long-needed infrastructure development or modernization. But, again, the level of intensity of utilizing economic instruments under the BRI is unprecedented not only for China but for any other country.

Nonetheless, the major focal point of debate surrounding China’s BRI is what the underlying national goals are. There is no doubt that the project is shaped by China’s economic interests. 13th Five Year Plan for 2016–2020 indicates that the BRI is a key in China’s further opening of the economy. With the BRI “paving the way,” China is to “encourage more of China’s equipment, technology, standards, and services to go global,” facilitate trade, also Chinese enterprises to invest overseas. The importance of BRI in China’s domestic economic development is emphasized by the fact that in 2015 China announced it had set up a special leading group to oversee the implementation of the BRI in charge of guiding and coordinating work related to the initiative, with the office of the group placed under the National Development and Reform Commission, China’s top institution in charge of economic policies.

Further, it is aimed at stabilizing the Western region, mainly Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). The 13th Five Year Plan states the need to ensure that the BRI “is able to better drive development in this region.” It also states China’s intention “to develop Xinjiang as the core region for the Silk Road Economic Belt.” This is a relatively old domestic policy objective for China. In 1999 Beijing launched “Open up the West” (Xībù Dàkāifā) program, aimed at promoting economic development in its Western regions, then significantly underdeveloped. This gradually became one of the key efforts to stabilize XUAR.

To that extent, BRI – except for its large scale – does not suggest any significant change in China’s economic statecraft. The means seem to be very similar to before and they serve China’s long-term national goals. Yet, outside observers of China suggest that the official agenda projected into the BRI is much wider than officially presented and different arguments abound on what the arising security externalities could be. At the moment, it is still unclear whether China is indeed using the BRI instrumentally to expand its global presence and political influence. But if that is the case, then this expansion in the agenda could be attributed to the expansion of China’s economic might, and, thus, China’s own perception of its capabilities.

4.2 The use of economic sanctions

Before, China, a recipient of economic sanctions, tended to avoid imposing economic sanctions on other countries. Historically, since the establishment of the PRC in 1949, China refrained from using coercive means in its foreign relations – not only military force but also negative economic statecraft tools, i.e. sanctions, in both bilateral and multilateral settings. Arguably, in the decades following the introduction of the economic reform by Deng Xiaoping, this became “a very distinctive trait of China’s foreign policy.”Footnote45 However, Chinese economic sanctions policy seems to be at an inflection point.

To understand how China applies economic sanctions and what changes there have occurred in its policies under the current administration, it is necessary to separate multilaterally imposed sanctions from those introduced by China unilaterally.

4.2.1 China’s approach to multilateral sanctions

Before China often objected to the imposition of multilateral economic sanctions, supporting its stance by the principle of noninterference into internal affairs of other countries. Throughout 1980s and 1990s it has abstained from voting on UN Security Council resolutions that suggested economic sanctions rather than vetoing them, in this way staying on the sidelines of multilateral decision-making. After 2000, this neutral stance has changed and it vetoed several attempts to impose economic sanctions through the UN on Myanmar in 2007, Zimbabwe in 2008, and multiple times on Syria since 2011. At around the same time, changing its long-term stance, it supported economic sanctions on Iran and North Korea.

In the case of North Korea, even under the international pressure to do so, China long opposed sanctions, arguing that they would severely affect the lives of ordinary North Koreans, or even lead to regime collapse. A major shift in China’s approach to the issue came around 2006, when it supported UN Security Council resolution 1718, imposing economic sanctions. It has gradually shifted its position toward supporting multilateral sanctions, and has implemented them more faithfully since early 2017Footnote46 Earlier criticized for a loose enforcement of the sanctions, since 2013, China began implementing them in a more transparent mannerFootnote47 Throughout the UN Security Council resolutions of 2009, 2013, 2016, and 2017, sanctions on North Korea have gradually evolved from weapon embargos to financial sanctions to be strengthened further by restrictions on the import of North Korea-produced coal and to restrictions on the export of refined petroleum products and crude oil to North KoreaFootnote48, even though China was able to influence the final decision on the sanctions. As security concerns over North Korea issue increased in Beijing, so did the domestic pressure to revise China’s policy toward it. Thus, under Xi Jinping, China supported unprecedentedly harsh economic sanctions on the country. But as relations between China and North Korea improved since 2018, China advocates a more moderate approach toward the problem.

Again, in contrast to its long-term approach to multilateral sanctions, in 2010 China supported the UN Security Council resolution imposing sanctions on Iran. As with the resolutions on North Korea, initial sanction proposals were eased as a result of pressure from China and Russia, and China’s UN ambassador Zhang Yesui was quoted by BBC website on June 9, 2010 saying that sanctions were trying to prevent nuclear proliferation and would not hurt “the normal life of the Iranian people.” That is, China was satisfied with the final measures.

4.2.2 China’s unilateral sanctions

Some suggest that China has become increasingly comfortable with using sanctions unilaterally, attributing it to China’s relative economic powerFootnote49 Indeed, while opposition to sanctions has long been considered to be a core principle of Chinese foreign policyFootnote50, since 2010, China has imposed unilateral sanctions more often than ever before. below presents a list of all negative economic sanctions used by China since 1978. China has used negative economic tools – sanctions and threats of sanctions including – at least 15 times since 2007, with such cases earlier very sporadic with only four of them observed prior to 2007.

Table 1. China’s use of economic sanctions since 1949 (compiled by the author from multiple sources)Footnote51.

Often, sanctions were imposed in retaliation, often as a punishment or a threat of punishment to a country that has interfered with what China considers to be its sovereignty, e.g., meetings with the Dalai LamaFootnote52, territorial disputes, or arms transfers to Taiwan. In addition, economic sanctions were imposed in cases when a country’s actions were perceived by China to pose a threat to its security, such as THAAD deployment in South Korea in 2016. But in most cases, the sanctions were more aimed at stating China’s opposition rather than imposing real long-lasting damage on the target country.

As China’s economic impact abroad has grown, it has revised the tools available to it in pursuit of its national goals. Reilly offers an informative account on China’s new thinking on sanctions that emerged in the 2000s. Among a few examples of the domestic debate, Reilly quotes a Chinese legal scholar who calls upon the full utilization of the important tool of unilateral sanctions, in order to fully and effectively use available foreign policy and legal tools to achieve its foreign policy objectives. Reportedly, Chinese government has funded a national research project exploring new approaches to sanctionsFootnote53 And this domestic debate seems to have been turned into official policy.

5 Multilateralism in China’s economic statecraft

Overall, there is one new feature, which stands out in China’s exercise of its economic statecraft under the current administration of Xi Jinping, mainly, the multilateral element. For decades, China applied economic instruments unilaterally or through bilateral agreements. In this respect, the BRI and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) might be the most notable initiatives in China’s exercise of its economic statecraft.

China initiated the AIIB around the same time when the BRI was launched. Established in 2015 with 57 founding members, it became the first Asia-based international bank to be independent from the Western-dominated Bretton Woods institutions, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. While being a complimentary initiative to China’s regional infrastructure development plan, it is an institution, separate from the BRI. Its multilateral structure comes in a stark contrast to any of the other economic tools that China has ever used before in its foreign policy.

The most remarkable example of how China’s unilateral use of economic tools shifted toward multilateral framework is represented by the BRI. In July 2020, Chinese Ministry of Finance announced that a multilateral fund for BRI infrastructure projects had been set up. Six countries – China, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Hungary, Cambodia and the Philippines – agreed to donate 180.2 million USD to the fund. This fund was set up by the Multilateral Cooperation Center for Development Finance (MCCDC), a multilateral coordination mechanism jointly launched by the Chinese Ministry of Finance, Asian Development Bank, AIIB, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, European Investment Bank, New Development Bank, the World Bank Group, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the International Fund for Agricultural Development. According to the Memorandum of Understanding on Matters to Establish the MCCDC signed by all sides on March 25 2019, its main mandate is “to foster high-quality infrastructure and connectivity investments for developing countries” with the focus on information sharing, capacity building, and project preparation. This is the first example, when China initiated a multilateral framework for the implementation of development projects, which before used to be supported through different unilateral development-finance instruments.

Considering the needs for infrastructure development in Asia, China’s intention to attract international capital is understandable. According to the estimates by the Asian Development Bank, for Asia alone, 26 trillion USD (including climate-related needs) is needed until 2030. While the BRI could significantly contribute to financing Asia’s infrastructure needs, it is estimated that a cumulative gap of about 4.6 trillion USD would emerge by 2040Footnote54 Considering this, it is clear why in his speech at the Opening Ceremony of the BRI Forum for International Cooperation on May 14 2017, Chinese President Xi not only committed to scaling up financing for the BRI but also stated China’s intention to cooperate with international development institutions to further raise funding for the infrastructure development projects under the BRI. Against this background, China’s turn to multilateralism could be regarded as a new means to promote the same goals – regional infrastructure development, and, in turn, as Chinese leaders put it, “promote peaceful regional environment for China’s development.” What used to be achieved through China’s unilateral economic instruments, is now further diffused through multilateral arrangements at a greater scale. That is, seen in this light, China’s embrace of multilateralism is a new instrument of statecraft, but still serves the same national objectives as before.

Nonetheless, such an evaluation might be an underestimation of the actual change that has occurred in China’s exercise of economic statecraft as a result of increased power capabilities. There are some signs that indicate that the national goals that China pursues have expanded. While it seeks to secure peaceful regional environment for the domestic development, China now also intends to reshape the existing international regimes in such a way that these would better serve its national goals. China’s 13th Five Year Plan clearly stipulates that China seeks to “Participate in global economic governance,” through which China would “help reform and improve the international economic governance system, actively guide the international economic agenda, safeguard and consolidate the multilateral trade system, work to see the international economic order develop in a way that facilitates equality, fairness, mutual benefit, and cooperation, and work with other countries to deal with global challenges” (Ch. 52).

Economy notes that “Chinese President Xi Jinping has a stated and demonstrated desire to shape the international system, to use China’s power to influence others, and to establish the global rules of the game.”Footnote55 Chinese leaders have been open about their desire to shape international system for the purpose of making it suit the interests not only of China but also of other latecomers into the international arena, rather than the Western countries only. In his speech at the Sustainable Development Goals Summit in 2015, Xi Jinping called upon deeper South-South cooperation “to push forward global economic governance reform and raise the representation and voice of developing countries.” It then suggests that for China multilateralism and leadership in the global affairs is instrumental rather than being the goal in itself.

This argument is then consistent with China’s approach to multilateral sanctions. Traditionally a harsh critic of multilateral economic sanctions, since the mid-2000s, China softened its stance on the use of this negative economic tool. When sanctions on Iran or North Korea were considered at the UN Security Council, China did not abstain from voting as before, but instead joined the discussions and, as a result of its participation, initial proposals were significantly softened, which was in the interest of China. That is to say, participating in multilateral arrangements China was able to shape the multilateral use of economic instruments along its own lines.

And this is exactly what China seems to be doing through the shift of its economic resources to multilateral frameworks of regional development China itself initiates – altering the available international regimes. Keohane and Nye note that international regimes – the set of formal or informal rules and norms – are intermediary structures between the system and the process. The structure of the system, i.e., the distribution of power resources among states, affects the nature of the regime, which, in turn, affects the political bargaining and daily decision-making within the systemFootnote56 While no such pattern can be observed in China’s bilateral interactions, when it comes to multilateral setting, it appears that China utilizes its increased economic power to change the existing regime of interaction, i.e., it creates new multilateral frameworks. These frameworks then further increase the interdependence between the states and, as a result, could enable China to have even more influence on the final outcomes of interaction with other states. That is to say, while China can use its large economic power resources to shape the regimes, these regimes then further strengthen China’s ability to achieve desired outcomes.

6 Conclusion

This paper sought to expose the effect that the increase of China’s economic capabilities had on its use of economic tools in pursuit of national objectives, i.e., on China’s exercise of economic statecraft. It was assumed that the growth of economic capabilities of China significantly boosted its interdependence with other states and also shifted power asymmetries in favor of China, which then could enable China as a less dependent actor to use this interdependent relationship as a source of power to shape other issues as well.

Generally, China utilized economic instruments at its disposal – both positive and negative – increasingly more often and at a greater scale over the last two decades. This trend has been constant since the early 2000s and is a rather natural outcome of China’s growing economic might.

In addition to this quantitative change, there were also qualitative changes observed. China turned to economic sanctions more often after mid-2000s, i.e., it is increasingly comfortable with the use of negative tools in pursuit of national goals. But this indicates a limited-degree change, as China used unilateral sanctions in pursuit of the same traditional objectives as before – to reassert China’s sovereignty, territorial integrity, One-China policy or in response to perceived security threats. The recent trend indicates that China is already aware of the relevance and impact of the economic capabilities it has acquired. At the same time, it needs to be noted that in most cases, unilateral sanctions were more symbolic acts to express China’s disapproval rather than any long-term damage to the target countries. Overall, China’s use of unilateral economic sanctions was less active than the actual change in its economic power could have suggested.

Since around the same time, China became increasingly comfortable with joining multilateral sanctions. But this is attributable more to China’s intention to shape the processes from within rather than larger economic resources available to it.

Overall, the embrace of multilateralism appears to be the most remarkable change in China’s exercise of economic statecraft. Recently, under the Xi Jinping administration, China started mobilizing multilateral frameworks to exercise its economic instruments and even diffuse these instruments to be used by newly set up multilateral institutions. On the one hand, this became a new means to pursue the old goals. On the other hand, drawing from the observations on China’s behavior with multilateral sanctions, it can be concluded that China has adopted a new approach to multilateralism to shape international regimes in a way, which better suits China’s national objectives.

In this regard, the turn to multilateralism demonstrates the self-reinforcing effect of China’s economic power. As China’s economic power has expanded tremendously, the interdependence between China and other states increased. In this interdependent system, China’s potential ability to influence the others and also shape the existing international regimes has increased remarkably. For example, it has been able to establish the first Asia-based international bank independently from the West-dominated Bretton Woods institutions, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, and convince other countries to join this initiative. Such a new regime functions as an intermediary structure between China’s economic power and the actual political bargaining within that system. And since it is shaped by China, it is likely to lead to even bigger power asymmetry in favor of China, i.e., China is able to have significantly higher influence over the final outcomes than it would otherwise do without having altered the existing international regime.

In a nutshell, as China has started exercising its expanded economic power in the interdependent world, a very inertial process of power asymmetry shift to China’s favor has been started. As a result, China is likely to be increasingly able to translate its economic power into the actual influence.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Vida Macikenaite

Vida Macikenaite is an assistant professor at the Graduate School of International Relations at the International University of Japan. She holds graduate degrees from Fudan University in China and Keio University in Japan. Her major research interest focuses on Chinese politics, both domestic and foreign, and extends further to authoritarian regimes.

Notes

1 Morrison, “China’s Economic Rise,” 1..

2 Mearsheimer, “The Gathering Storm.”.

3 Keohane and Nye, Power and Interdependence, 17–18..

4 Keohane and Nye, Power and Interdependence, 10..

5 Ibid.

6 Hermann, “Changing Course.”

7 World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and China Tourism Academy (CTA), Guidelines for the Success, 12..

8 “Number of students from China going abroad for study from 2008 to 2018,” Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/227240/number-of-chinese-students-that-study-abroad/; Xinhua, “More Chinese study abroad in 2018,” March 29 2019, http://en.moe.gov.cn/news/media_highlights/201904/t20190401_376249.html..

9 Keohane and Nye, 21.

10 In their conceptualization of interdependence, Keohane and Nye differentiate between interconnectedness, which is defined simply by the existence of international transactions – flows of money, goods, people, and messages across international boundaries, and interdependence, when interconnectedness is also characterized by reciprocal potential costs (Keohane and Nye, Power and Interdependence, 7–8)..

11 Keohane and Nye, Power and Interdependence, 9..

12 Keohane and Nye, Power and Interdependence, 10.

13 According to the data provided by the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), in 2018, 35.5% of Australia’s exports went to China (https://oec.world/en/profile/country/aus/)..

14 Hermann, “Changing Course,” 5.

15 Hermann, “Changing Course,” 6–7..

16 Here in this paper, the term “foreign policy objectives/goals” is intentionally replaced with the term “national goals” or “national policy goals” to emphasize that economic statecraft may be driven not only by foreign but also domestic policy goals.

17 Freeman, Arts of Power, 2..

18 An elaborate discussion on the choice of the term economic statecraft over other similar concepts, including foreign economic policy, is offered by Baldwin in Economic Statecraft, 33–40. Baldwin points out that “No portion of the vocabulary of statecraft is more in need of conceptual tidying than that relating to economic techniques” (Baldwin, Economic Statecraft, 29)..

19 Baldwin, Economic Statecraft, 3.

20 Ibid, 21..

21 Baldwin, Economic Statecraft. As the most common examples of negative tools, Baldwin mentions embargo, boycott, tariff increase, tariff discrimination (unfavorable), withdrawal of “most favored-nation treatment,” blacklist, quotas (import or export), license denial (import or export), dumping, prelusive buying, threats of the above, and also freezing assets, controls on import or export, aid suspension, expropriation, taxation (unfavorable), withholding dues to international organization, threats of the above. For the positive tools, or economic incentives, there are tariff discrimination (favorable), granting “most favored-nation treatment,” tariff reduction, direct purchase, subsidies to export or imports, granting licenses (import or export), promises of the above, also aid, investment guarantees, encouragement of private capital exports or imports, taxation (favorable) or promises of the above. China has developed a relatively distinct set of economic tools, but Baldwin’s distinction of positive and negative tools is applicable to any country, including China..

22 Blanchard et al, Power and the Purse, 5..

23 Pardo, “Europe’s Financial Security.”.

24 Urdinez et al, “Chinese Economic Statecraft.”.

25 Morgan, “Can China’s Economic Statecraft Win.”.

26 Alves, “China’s Economic Statecraft.”.

27 For further details see Brautigam, “Aid ‘With Chinese Characteristics.”.

28 Alves, “China’s Economic Statecraft,” 213..

29 E.g. see Kitano and Harada, “Estimating China’s Foreign Aid”; Kitano, “Estimating China’s Foreign Aid”; Brautigam at al, “Chinese Loans.”

31 For an exhaustive explanation on China’s foreign aid and other official flows, see Brautigam, “Aid ‘With Chinese Characteristics”; also Brautigam, “Chinese Development Aid.”.

33 Outward FDI activities by Chinese companies were controlled and directed by the state throughout much of the time period since the going out policy was launched in 2001, with a short exception of 2014 to 2017, when there was significant deregulation in place.

34 In 2019, there were 124 Chinese companies on the Fortune Global 500 list of the world’s largest corporations, while there were only nine of them on this list in 2000..

35 See above 25

36 Current outward FDI regulations define “prohibited investments,” among them are those in countries that have diplomatic relations with Taiwan.

37 Rudyak, “The Ins and Outs,” 1..

38 Dreher et al, “Apples and Dragon Fruits.”.

39 Fuchs and Rudyak, “The Motives of China’s.”.

40 See above 37 7..

41 See above 20, 5..

42 OECD, “The Belt and Road Initiative.”

43 Ibid..

44 See above 28 218..

45 See above 20, 213.

46 Kim, “Trump Power.”.

47 Li and Kim, “Not a Blood Alliance..

48 See above 20, 2.

49 Nephew, “China and Economic Sanctions.”.

50 van Kemenade, “China vs. the Western Campaign.”

51 Compiled by the author based on Copper, “China’s Foreign Aid;” Hufbauer et al, Economic Sanctions Reconsidered; Harrell et al, “China’s Use;” Reilly, “China’s Unilateral Sanctions;” Philip Wen and William Mauldin, “China to Sanction U.S. Companies for Arms Sales to Taiwan,” The Wall Street Journal, July 12 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-to-sanction-u-s-companies-for-arms-sales-to- taiwan-11,562,937,253; Yan Hao, “‘China May Sanction Arms-selling U.S. Companies with Multifold Options, Firms Remain Silent,’” Xinhua, February 2 2010, http://english.cctv.com/20100203/101205.shtml; Chen and Garcia, “Economic Sanctions;” BBC, “Coronavirus: China warns students over ‘risks’ of studying in Australia,” June 10 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-52980637; Stephen Dziedzic, “Australia started a fight with China over an investigation into COVID-19 – did it go too hard?” ABS News, May 20 2020, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-20/wha-passes-coronavirus-investigation-australia-what-cost/12265896; “China ‘blocks’ Mongolia border after Dalai Lama visit,” Aljazeera, December 10 2016, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2016/12/10/china-blocks-mongolia-border-after-dalai-lama-visit.

52 Fuchs and Klann, “Paying a Visit.” Fuchs and Klann find that political tensions caused by country leaders receiving the Dalai Lama lead to a significant reduction of these countries’ exports to China.

53 Reilly, “China’s Unilateral Sanctions,” 122–123..

54 See above 42.

55 Economy, The Third Revolution, 186.

56 Keohane and Nye, Power and Interdependence, 18..

Bibliography

- Alves, A. C. “China’s Economic Statecraft in Africa: The Resilience of Development Financing from Mao to Xi.” In China’s Economic Statecraft: Co-optation, Cooperation, and Coercion, edited by L. Mingjiang, 213–240. Singapore: World Scientific, 2017.

- Baldwin, D. A. Economic Statecraft. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985.

- Blanchard, J.-M. F., E. D. Mansfield, and N. M. Ripsman, eds. Power and the Purse: Economic Statecraft, Interdependence, and National Security. London: F. Cass, 2000.

- Brautigam, D. “Aid ‘With Chinese Characteristics’: Chinese Foreign Aid and Development Finance Meet the OECD-DAC Aid Regime.” Journal of International Development 23 (2011): 752–764. doi:10.1002/jid.1798.

- Brautigam, D. “Chinese Development Aid in Africa: What, Where, Why, and How Much?” In Rising China: Global Challenges and Opportunities, edited by J. Golley and L. Song, 203–223. Canberra: Australia National University Press, 2011.

- Brautigam, D., J. Hwang, J. Link, and K. Acker. Chinese Loans to Africa Database. Washington, DC: China Africa Research Initiative, Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, 2020. https://chinaafricaloandata.org.

- Chen, X., and R. J. Garcia. “Economic Sanctions and Trade Diplomacy: Sanction-busting Strategies, Market Distortion and Efficacy of China’s Restrictions on Norwegian Salmon Imports.” China Information 30, no. 1 (2016): 29–57. doi:10.1177/0920203X15625061.

- Copper, J. F. “China’s Foreign Aid in 1978.” Maryland Series in Contemporary Asian Studies 8 (1979). https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mscas/vol1979/iss8/1.

- Dreher, A., A. Fuchs, B. Parks, A. M. Strange, and M. J. Tierney. “Apples and Dragon Fruits: The Determinants of Aid and Other Forms of State Financing from China to Africa.” International Studies Quarterly 62, no. 1 (2018): 182–194. doi:10.1093/isq/sqx052.

- Economy, E. C. The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- El-Khawas, M. A. “China’s Changing Policies in Africa.” Issue: A Journal of Opinion 3, no. 1 (1973): 24–28. doi:10.2307/1166311.

- Freeman, C. W., Jr. Arts of Power: Statecraft and Diplomacy. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1997.

- Fuchs, A., and N.-H. Klann. “Paying a Visit: The Dalai Lama Effect on International Trade.” Journal of International Economics 91, no. 1 (2013): 164–177.

- Fuchs, A., and M. Rudyak. “The Motives of China’s Foreign Aid.” Chap. 23 In Handbook on the International Political Economy of China, edited by K. Zeng, 392–410. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019.

- Harrell, P., E. Rosenberg, and E. Saravalle. “China’s Use of Coercive Economic Measures.” Center for a New American Security, 2018, https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.cnas.org/documents/China_Use_FINAL-1.pdf?mtime=20180604161240.

- Hermann, C. F. “Changing Course: When Governments Choose to Redirect Foreign Policy.” International Studies Quarterly 34, no. 1 (1990): 3–21. doi:10.2307/2600403.

- Hu, W. “Xi Jinping’s ‘Major Country Diplomacy’: The Role of Leadership in Foreign Policy Transformation.” Journal of Contemporary China 28, no. 115 (2019): 1–14. doi:10.1080/10670564.2018.1497904.

- Hufbauer, G., J. Schott, K. Elliott, and B. Oegg. Economic Sanctions Reconsidered. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2007.

- Keohane, R. O., and J. S. Nye. Power and Interdependence. 4th ed. Boston: Longman, 2012.

- Kim, I. “Trump Power: Maximum Pressure and China’s Sanctions Enforcement against North Korea.” The Pacific Review 33, no. 1 (2020): 96–124. doi:10.1080/09512748.2018.1549589.

- Kitano, N. “Estimating China’s Foreign Aid Using New Data.” IDS Bulletin 49, no. 3 (2018). https://bulletin.ids.ac.uk/index.php/idsbo/article/view/2980/Online%20article.

- Kitano, N., and Y. Harada. ““Estimating China’s Foreign Aid 2001–2013.” Journal of International Development 28, no. 7 (2016): 1050–1074.

- Li, W., and J. Y. Kim. “Not a Blood Alliance Anymore: China’s Evolving Policy toward UN Sanctions on North Korea.” Contemporary Security Policy (2020): 1–19. doi:10.1080/13523260.2020.1741143.

- Mearsheimer, J. J. “The Gathering Storm: China’s Challenge to US Power in Asia.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 3 (2010): 381–396. doi:10.1093/cjip/poq016.

- Morgan, P. “Can China’s Economic Statecraft Win Soft Power in Africa? Unpacking Trade, Investment and Aid.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 24 (2019): 387–409. doi:10.1007/s11366-018-09592-w.

- Morrison, W. M. “China’s Economic Rise: History, Trends, Challenges, and Implications for the United States.” Congressional Research Service, June 25, 2019 (RL33534). https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL33534.pdf.

- Nephew, R. “China and Economic Sanctions: Where Does Washington Have Leverage?” Brooking Institution, September 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/FP_20190930_china_economic_sanctions_nephew.pdf.

- Norris, W. J. Chinese Economic Statecraft: Commercial Actors, Grand Strategy and State Control. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2016.

- OECD. “The Belt and Road Initiative in the Global Trade, Investment and Finance Landscape.” Chap. 2 In OECD Business and Finance Outlook 2018, 61–102. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018. doi:10.1787/bus_fin_out-2018-6-en.

- Pardo, P. R. “Europe’s Financial Security and Chinese Economic Statecraft: The Case of the Belt and Road Initiative.” Asia Europe Journal 16, no. 3 (2018): 237–250. doi:10.1007/s10308-018-0511-z.

- Reilly, J. “China’s Unilateral Sanctions.” The Washington Quarterly 35, no. 4 (2012): 121–133.

- Rudyak, M. “The Ins and Outs of China’s International Development Agency.” Workshop on Chinese International Development Aid, the Carnegie–Tsinghua Center. September 2, 2019. https://carnegieendowment.org/files/5-29-19_Rudyak_Chinese_Aid.pdf.

- Urdinez, F., F. Mouron, L. L. Schenoni, and A. Oliveira. “Chinese Economic Statecraft and U.S. Hegemony in Latin America: An Empirical Analysis, 2003–2014.” Latin American Politics and Society 58, no. 4 (2016): 3–30. doi:10.1111/laps.12000.

- van Kemenade, W. “China Vs. The Western Campaign for Iran Sanctions.” The Washington Quarterly 33, no. 3 (2010): 99–114. doi:10.1080/0163660X.2010.492344.

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and China Tourism Academy (CTA). Guidelines for the Success in the Chinese Outbound Tourism Market. ISBN: 978-92-844-2113-8. https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284421138.