ABSTRACT

This research examines the impact that China’s economic development has had on the political system that shapes the CCP-led single-party regime. In pursuit of this inquiry, this research focuses on the delegate composition in the people’s congress – China’s democratic institution. Previous research argues that China’s democratic institutions contribute to the stability of the single-party regime. However, when considering political functions of those democratic institutions, it does not give sufficient consideration to the possibility that the system itself and its political functions might change over the time. By analyzing 20-year materials of five consecutive terms from 1998 to 2018 on the delegates to the people’s congress of Yangzhou city in Jiangsu province, this research observes the changes in the delegate composition.

1 Introduction

Since the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) opted for the path of economic reform in the 1980s, it has been trapped in the contradiction between the unified politics of a single-party rule and along with economic development diversifying society. At the 14th Party National Congress convened in October 1992, the CCP officially recognized that socialism and market economy are not contradictory, and thus converged “Xin She Xin Zi” (the distinction of what is socialism and what is capitalism in the economic reform). However, the CCP has still not been able to overcome the contradiction between centralized politics and pluralized society. Thus, there remains an open question of how the CCP has confronted the contradiction between politics and society, moreover, how it has maintained its single-party rule.

This research examines the impact that China’s economic development has had on the political system that shapes the CCP-led single-party regime. In pursuit of this inquiry, this research focuses on the delegate composition in the people’s congress – China’s democratic institution. Previous research argues that China’s democratic institutions contribute to the stability of the single-party regime. However, when considering political functions of those democratic institutions, it does not give sufficient consideration to the possibility that the system itself and its political functions might change over the timeFootnote1 By analyzing 20-year materials of five consecutive terms from 1998 to 2018 on the delegates to the people’s congress of Yangzhou city in Jiangsu province, this research observes the changes in the delegate composition. Thus, the object of this research is domestic politics in the period of time when the CCP leadership, having gone through a long-term rapid economic development, has come to recognize China as a major country (Daguo). This research focuses on domestic politics in the same period of timeFootnote2

2 Significance of this research

Just like in a democracy, in an authoritarian state, there is often a political party, elections are held and there exists a parliament. Scholars interested in democratic institutions in authoritarian states have raised a question whether more active functioning of the parliament in authoritarian regimes would bring about democratization. Existing research suggests that in authoritarian states democratic institutions perform a political function of contributing to the maintenance of authoritarian regimeFootnote3 In China studies, some research addressing the same problem argues that the people’s congresses, i.e., China’s democratic institution, contributes to the maintenance of the single-party regimeFootnote4

The research on China’s democratic institutions in Japan can be broadly divided into two approaches, mainly, the research on the elections to the people’s congresses (electoral studies) and studies focusing on the characteristics and behavior of the delegates in the people’s congresses (delegate studies)Footnote5

Delegate studies focusing on delegate activities, such as submission of legislative bills (yi’an) and opinions (jianyi, piping, yijian), activity reports of state institutions and deliberations of personnel in the state institutions and draft laws, also, the decisions after deliberation (voting), analyze the motivation behind them. Generally, the reports, personnel, and draft laws presented for discussion at the people’s congress, are reviewed by the CCP in advance. Thus, it has been argued that a large number of “against” votes in the stage of voting signifies the disagreement between the CCP and the people’s congress, the weakening of CCP’s lead over it, and, even more, suggests a tremble in the CCP’s single-party rule. However, existing scholarship deems that such behavior of the people’s congress delegates performs a function of transmitting to the leadership the problems of society’s concern, and it points out that increasingly active behavior of people’s congress delegates contributes to upholding the single-party regime. It explains that the functions embedded into the political institution of people’s congresses are not only to transmit policies to the society but also to inform policymakers about the issues of concern to the society.

Yet, in the existing delegate studies, a few problems remain to be addressed. The most crucial one is that there has not been sufficient attention paid to how political institutions have changed with the passage of time. The delegates to the people’s congress change with each term. If there is a change in the delegate composition, it is necessary to examine the effect this change has on the political functions of the people’s congress. If there has been no change, then it is necessary to explain the reasons behind the lack of it. In a nutshell, the puzzle is whether political institutions adapt to social development in light of economic growth.

Since 1992, China has gone through rapid economic growth. In response to the resulting changes in the society, the CCP has revised party constitution, rewriting it at the 16th National Party Congress in November 2002. By adding the important Thought of Three Represents, it has changed the concept of what party the CCP is. Preceding party constitutions declared the CCP to be “the vanguard of the Chinese working class, the loyal representative of the interests of the people of the various nationalities of China, and the leading core of the Chinese socialist cause.” This was revised to define the CCP as “the vanguard both of the Chinese working class and of the Chinese people and the Chinese nation. It is the core of leadership for the cause of socialism with Chinese characteristics and represents the development trend of China’s advanced productive forces, the orientation of China’s advanced culture and the fundamental interests of the overwhelming majority of the Chinese people.” So, as a result, has the composition of the people’s congress changed over time and with the development of the economy?

Considering the above research questions, this research observes the changes in the people’s congress delegate composition through the analysis of 20-year materials covering five consecutive terms from 1998 to 2018 on the delegates to the people’s congress of Yangzhou city in Jiangsu province. This study is a preparatory work for the analysis of the change in the political function of the people’s congress that has contributed to the maintenance of the CCP’s single-party rule.

3 Delegate composition of the Yangzhou municipal people’s congress

3.1 The data

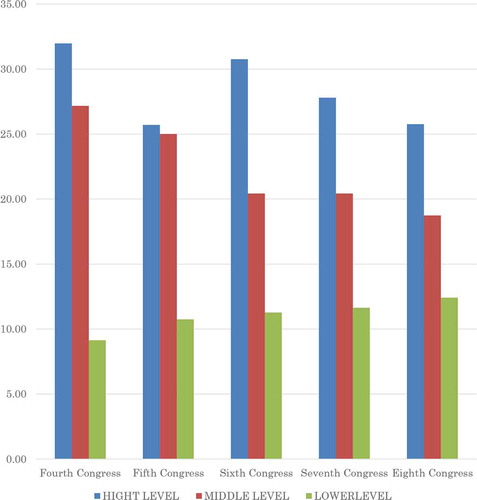

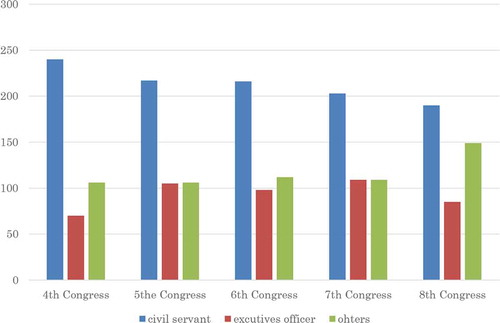

Yangzhou is a prefecture-level city (di ji shi) located in the lower reaches of the Yangtze river in Eastern China with a population of 4.58 million (2018). There are three districts (qu: GL, JD, WY), two county-level cities (shi: HJ, GY), and one county (xian: BY) in Yangzhou (see ), covering 6591 sq.km. as of 2020 (economic indicators see ).

Figure 1. Economic Indicators (GDP per capita, Yangzhou)

Figure 2. Economic Indicators (per capita disposable income, Yangzhou)

Table 1. Subregional GDP, Yangzhou (2018)

CLC: indicates a county-level city.

Source: Yangzhou Statistical Yearbook (2019), http://tjj.yangzhou.gov.cn/nj2019/nj2.htm

One of the reasons why this research takes Yangzhou as a case study is the availability of data. The Standing Committee of the Yangzhou municipal people’s congress (MPC) has made publicly available data on the delegates during five terms of the people’s congress starting in 1998 (one term is generally 5 years, see .).

Table 2. The terms of Yangzhou MPC since 1998

Further, in this period, Yangzhou was under continuous economic growth. Moreover, since 2003 it has achieved even faster economic growth rates. It has followed the typical pattern of China’s economic development.

As and consecutive ones demonstrate, publicly available data are rather detailed. The Standing Committee of Yangzhou MPC made public the names, gender, year of birth, affiliation and employment unit, ethnic identity, education, party affiliation, and other information of the delegates to the 4th (January 1998-January, 2003), 5th (January 2003 – January 2008), 6th (January 2008 – June 2012), 7th (June 2012 – February 2012), and 8th (since February 2017) people’s congress, as well as the information regarding bills and recommendations, comments, and opinions (hereinafter, recommendations) they submitted (title, date of submission, names of signatories, contents, the party and state institution they were submitted to, and also their response). There is no other standing committee of the people’s congress like that of Yangzhou, which would have made available such detailed and diverse information for over two decades.

Table 3. The shifts in delegate group size

The term of the 6th Yangzhou MPC was shortened to 4 years and 4 months. Based on the notification issued by the General Office of the CCP Central Committee in March 2011 that required to adjust the starting time of the terms of the city-, county-, and township-level people’s congresses, Jiangsu provincial party committee changed the date of the election so that the term of the 7th Yangzhou MPC would start by June 2012Footnote6

Electoral Law of the People’s Republic of China for the National People’s Congress and Local People’s Congresses provides that the delegates to the Yangzhou MPC are elected through indirect elections. This people’s congress is composed of representatives from one-level lower administrative regions, i.e. districts, counties, county-level cities (CLC), and the representatives of PLA Yangzhou sub-military district. That is, Yangzhou MPC is composed of representatives of interest groups, with regional representatives chosen from three district-level people’s congresses, one county-level people’s congress, two county-level city people’s congresses, and the representatives chosen from the PLA. These seven groups are referred to as “constituency groups (daibiaozu).” Starting with the 7th congress, the number of electoral district groups was reduced from eight to seven (see ).

shows the number of bills that were submitted and the recommendations that were made in each session of the Yangzhou MPC between 2001 and 2019. The bills submitted to address a wide range of concerns and questions, including cultural and educational issues, environmental protection issues, urban development issues, such as road construction and maintenance, bridge, or port construction projects, and requests for establishing economic development zones, and also administrative issues, such as taxation, public transportation management, and road management, garbage disposal management, social security issues in aging society, measures to improve the living conditions of residents. As suggests, the delegates of Yangzhou MPC have become increasingly active every yearFootnote7 An analysis of the bills and proposals submitted by the delegates has been conducted in the past in a rudimentary study. This representative study will be conducted at another time.

Table 4. Bills and recommendations to the Yangzhou MPC (2001–2019)

3.2 Changes in the basic attributes of the delegates

As demonstrates, from 1998 to 2018, there was no major change in the age of the delegates. It is commonly pointed out that the age of the delegates in Chinese people’s congresses is decreasingFootnote8, but no significant changes can be observed in the Yangzhou MPC. In recent years, the average age has even increased. Moreover, as shown in , from 1998 to 2018, there was no major change in the gender composition either.

Table 5. The age of the delegates

Table 6. Gender composition of the delegates, %

shows that from 1998 until 2012 the share of the CCP members in the municipal people’s congress increased steadily. After that, in 2018 it went down. indicates that in the period from 1998 to 2018 a significant rise in the level of education of the delegates can be observed. The number of delegates with a graduate degree increased eight times, while that of university or college degree – twice. Further, many of the graduate and college degrees were obtained by studying at the party school.

Table 7. The share of CCP members among the delegates, %

Table 8. Education level, % of the total no. of delegates

3.3 Dynamics in the affiliation and employment unit of the people’s congress delegates

The delegates’ affiliation and employment unit are an important key in understanding political function of the people’s congress. Often, categories of “cadres” (ganbu) and “intellectuals” (zishifenzi) are used to define the affiliation and employment unit of delegates the affiliation and employment unit of delegates. Nonetheless, they are of limited use for the analysis here. There are numerous professional characteristics that fall under the term ganbu, and they are also vagueFootnote9 Further, highly educated delegates can be classified as both cadres and intellectuals.

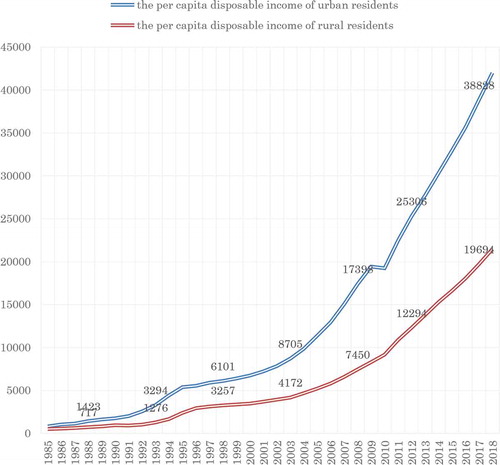

This research divides the delegates of Yangzhou MPC into six main categories, that is, civil servants (as defined by the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Civil Servants), PLA military personnel, enterprise staff (qiye danwei renyuan), public institutions staff (shiye danwei zhiyuan), people’s organizations (renmin tuanti), association members, and farmers or workers. Analysis focuses especially on civil servant and enterprise staff. The definition of civil servant is based on the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Civil Servants, that is mainly leader/staff of party institutions, delegate of people’s congresses, government institutions, court officials, prosecutor’s office staff, members of the political consultative conference, and members of the democratic parties (minzhudanpai). There are also delegates from the PLA. Their position in the party has remained more or less the same over the past 20 years (there were 12 in the 4th, 13 in the 5th, 12 in the 6th, 12 in the 7th, and 12 in the 8th people’s congress.).

Among the delegates to Yangzhou MPC, there were 284 (68.27%) civil servants in the 4th, 264 (61.68%) in the 5th, 265 (62.21%) in the 6th, 249 (59.14%) in the 7th, and 241 (56.44%) in the 8th people’s congress.

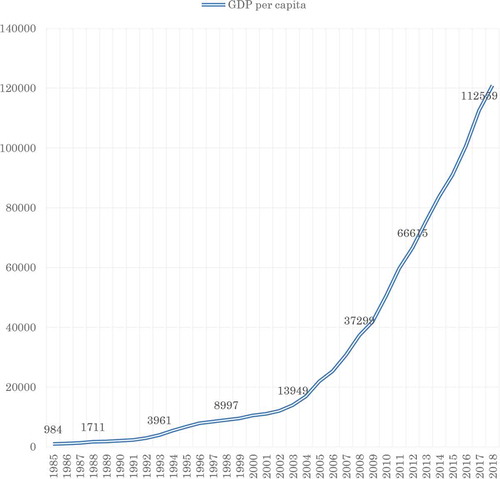

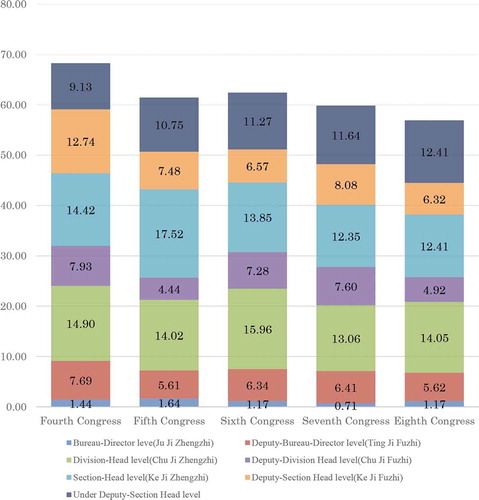

Civil servants can be classified by rank based on the Civil Service Posts and Grade Regulations (Gongwuyuan jiwu yu jibie bingxing guiding). Civil servants among the Yangzhou MPC delegates were classified into seven ranks (see ). These are the ranks of bureau-director level (ju ji zhengzhi), deputy-bureau-director level (ting ji fuzhi), division-head level (chu ji zhengzhi), deputy-division head level (chu ji fuzhi), section-head level (ke ji zhengzhi), deputy-section head level (ke ji fuzhi), and under deputy-section head level. presents the dynamics of the seven ranks of public servants (as provided in the Civil Service Posts and Grade Regulations) among the Yangzhou MPC delegates from the 4th until the 8th congress.

Table 9. The ranks of government officials

CLC: indicates a county-level city.

Source: Yangzhou Renda, http://rd.yangzhou.gov.cn

According to , the share of civil servants at the Yangzhou MPC has declined over the past 20 years, going down from 68.27% at the 4th congress to 56.44% at the 8th. This change was especially significant at the bureau-director level and deputy-bureau-director level, the cumulative share of delegates with these ranks decreasing from 9.13% to 6.56% from the 4th to the 8th congress respectively, thus, a 30% decrease in 20 years. Such a significant decrease in bureau-director level and deputy-bureau-director level officials, who are responsible for making policy decisions in the Yangzhou government departments, is remarkable. At the same time, the share of the division-head level and deputy-division head level officials among the delegates was also on a downward trend, declining from 27.16% at the 4th congress to 17.80% at the 8th.

Seeking to expose the changes in the number of civil servants more clearly, this research suggests an alternative three-level classification of civil service ranks, with bureau-level and division-level ranks defined as high-level civil servants, section level – as middle-level civil servants, and all the remaining ranks below section level marking the regular lower-level civil servants. presents the data on civil servants among the delegates classified based on these three groups. As can be seen from , high-level government officials among Yangzhou MPC delegates decreased during the observation period from 31.78 to 27.75%. Similarly, the share of middle-level officials also went down. At the same time, the share of officials below section level among the delegates increased significantly from 9.13% in the 4th congress to 12.41% in the 8th(see ).

On the other hand, over the two-decades observation period, a few trends in the share of government officials among the delegates have not changed. First, there is a large share of public servants among delegates. From the identified seven occupations of the delegates to Yangzhou MPC, public servants constitute the largest one. Second, the share of the high-level officials is the largest when compared with the middle-level or lower-level officials.

According to , civil servants among delegates of people’s congress are evenly distributed in each constituency. Interestingly, the proportion of civil servants elected from GL district (see ), which is located in the political and economic center of Yangzhou, and the proportion of civil servants elected from GY CLC and BY County, which are relatively less economically developed in Yangzhou, is higher than in other constituencies. This suggests that the Communist Party Yangzhou municipal Committee has paid attention to the city’s political and economic core and to the areas with relatively slow economic development.

Table 10. The share of civil servant among the delegates of the Yangzhou MPC

While the share of civil servants among the delegates has decreased, the share of corporate executives and company employees has risen. At the 4th congress, there were 26.68% of them, then 28.97% at the 5th, 28.87% at the 6th, 30.87% at the 7th, and 27.35% at the 8th congress. Especially the share of executives has been growing. Further, the number of non-state-owned enterprise staff is increasing (see ).

Figure 3. The share of civil servant at the Yangzhou MPC (as a ratio of the total number of the delegates to Yangzhou MPC)

Table 11. The share of corporate executives and employees’ delegate at the Yangzhou MPC, %

4 Discussion and conclusion

An important point in the literature on democratic institutions in authoritarian regimes is whether democratic institutions contribute or not to sustaining the regime. Research on democratic institutions in China as an authoritarian country have also centered around this question. Existing research shows that Chinese people’s congresses provide policymakers, i.e., the party and the government, with the information necessary for identifying policy issues, drafting policies, making policy decisions, and executing policies. Further, research also shows that people’s congress offers policymakers policy assessment. Previous research shows that delegates to the people’s congresses perform three functions, mainly, they act as representatives of policymakers transmitting the will of the policymakers to the society (agents), as advocates transmitting society’s assessment of policies to the policymakers (remonstrators), and as representatives transmitting society’s demands to the policymakers (representatives).

Taking Yangzhou MPC as a case study, this research observed how the composition of the people’s congress changed in the course of 20 years. The efforts of this research have raised a new research topic, showing the direction for further research on Chinese peoples’ congresses.

As this research revealed, over the past 20 years, there has been a change in the delegate composition at the Yangzhou MPC. The share of delegates with university or higher degree rose dramatically from 30% to 80%. Next, the proportion of government officials decreased, with the number of high-level officials going down and those of lower-level rising. Further, there was an increase in the number of company staff among the delegates, especially those from non-SOEs. Furthermore, while the number of top-level company staff rose, there were fewer general staff employees among the delegates. The ratio between male and female delegates changed from 8 to 2 toward 7 to 3.

When seen from the perspective of economic development and social change accompanying it, these changes in the composition of the delegates to Yangzhou MPC are very gradual. It can be even said that, actually, over two decades no big changes occurred in this regard. The average age of the delegates was around 40 years old. The number of CCP members among delegates remained stable at around 70%. The share of government officials among the delegates was maintained above 50%. Among the delegates to Yangzhou MPC, civil servants remained to be the largest group. Company staff delegates, when divided by their position level, remained to be dominated by top-level company executives.

So, why was there a lack of change in the people’s congress delegate composition, while there was a significant change in the economy and society of Yangzhou? Over the past 20 years, the economy of Yangzhou developed dramatically, society has also changed. And this should have brought about a change and diversification in the demands of the people of Yangzhou. Why did the CCP not change the delegate composition of the people’s congress in response to such changes in the society?

In regard to this question, this research offers the following tentative answers. As previous studies have pointed out, China’s democratic institutions, i.e., the people’s congresses, have contributed to the maintenance of the regime. The CCP has actively utilized the political authority and power of the political and economic elites of Chinese society to maintain its rule. People’s congress has been the place for the elite of the Chinese society to display their support to the one-party rule, the place where the voice (policy) of the CCP is transmitted to the society and the place where the CCP gathers the voices of the society (support and criticism of its policies) and delivers it to the policymakers, the CCP. The People’s Congress served as one of the bridges between the party and the society. It would not have been easy for the CCP to change the composition of the People’s Congress, which has played an important role. Therefore, it may be necessary to add the qualifier “so far” to the results of the analysis presented by previous studies. The changes in the composition of the Yangzhou MPC delegates observed by this study do not appear to have adapted to the rate of social structural change following economic development.

To verify this tentative answer, delegates, who are officials at the bureaucratic and departmental levels and executives of state and non-state enterprises, are an important key of study. To understand the relationship between China’s socioeconomic development and the development of the people’s congress system, it will be necessary to determine what their activities in the people’s congresses are and how they have changed. And we need to identify the reasons behind the changes. This new research agenda provides the approach needed to understand the mechanisms (and their weaknesses) that allow the CCP to maintain its one-party rule.

This study is only a case study of a people’s congress in a municipal city on the east coast of China. The results of this study are not meant to be representative of the realities of people’s congresses in different parts of China. However, because public access to data on the activities of people’s congresses is still limited and understanding of the system is highly fragmented, this study’s attempt to understand the people’s congress system through changes in delegate composition over two decades provides important insights into the political functioning of China’s democratic institutions. This study also represents a new area of research on the Chinese people’s congress system.

This research is the result of joint research with He Junzhi, Professor, School of Government, Sun Yat-sen University.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tomoki Kamo

Dr. Tomoki Kamo is a professor of Chinese politics at the Faculty of Policy Management at Keio University. His research and teaching focus on Chinese politics and foreign policy, comparative politics, and international relations of East Asia. He was appointed as a consul to the Consulate-General of Japan in Hong Kong (2016-2018). He was a visiting scholar Graduate Institute of Political Science, National Taiwan Normal University (Taiwan) (2010) and Center of Chinese Studies, University of California, Berkeley (2011-2012) and a visiting associate professor of College of International Affairs, National Chengchi University (Taiwan) (2013-2013). Previously he served as a research fellow at Consulate-General of Japan in Hong Kong (2001-2003) and studied at Fudan University (1995-1996). He received his B.A., M.A. and Ph.D. of Media and Governance from Keio University. His recent publication includes: Political Institutions in Contemporary Chinese Politics: The Politics of Temporality and the Rule of the Chinese Communist Party (in Japanese) ,Tokyo: Keio University Press, 2018. ; The Sources of China’s Foreign Policy (in Japanese), Tokyo: Keio University Press, 2016. ; The Rise of China as a major power (in Japanese), Tokyo: Ichigeisya Press, 2016 ; From the Revolution to the Open Door Policy (in Japanese), Tokyo: Keio University Press, 2011 ; Transition of China's Party-State System: Demands and Response (in Japanese), Tokyo: Keio University Press, 2012. ; and Contemporary Chinese Politics and People’s Congresses: Reforms of People’s Congresses and Changes in the “Guiding-Guided” (Lingdao–Bei Lingdao) Relationship (in Japanese), Tokyo: Keio University Press, 2006.

Notes

1 Kamo, and Takeuchi, “Representation and Local People’s Congress”; Kamo, “Chinese People’s Liberation Army.”

2 Having sustained high-speed economic development over a long term, building on its expanded economic power China has stretched its global presence. To protect its national interests that have spread globally along with China’s economic development, also to uphold international environment favorable for its economic development, the current leadership has developed diplomatic line of the so-called “major country diplomacy with distinctive Chinese features” (Zhongguo Tese Daguo Waijiao). The leadership is increasingly aware of their country as daguo. But what is daguo? In China’s official discourse, it is translated as a “major country,” see Xi, “Break New Ground.” On the other hand, in the book published by the CCP Publicity Department, which explains the remarks by the President Xi Jinping, daguo is defined as “a decisive power for world peace” (Daguo shi Yingxiang Shijie Heping de Juedingxing Loliang), See Publicity Department of the Communist Party, Xijinping Zongshuji Xilie:268. It is reasonable to think of the term daguo as inclusive of the term power. Thus, the current leadership considering that there exist institutions that can exercise foreign policy fitted for daguo, has promoted a discussion on the reform of China’s foreign policy decision-making mechanism, also see Li Xue “China’s Foreign Policy”.

3 Jennifer Gandhi and Ruiz-Rufino Ruben, Routledge Handbook of Comparative Political Institutions; Milan W. Svolic, The Politics of Authoritarian; Keiichi Kubo, “Tokusyu ni Atatte”.

4 Kevin J. O’Brien, “Agents and remonstrators”; Kevin J. O’Brien, “Chinese People’s congresses”; Kevin J. O’Brien, “Local people’s congresses,” and Ming Xia, The People’s congresses.

5 Mari Nonaka, “Chugoku Chihou Jinmin”; Tomoki Kamo, “Gendai Chugoku ni okeru Minyi”.

6 Guanyu Quansheng Shixianxiang Sanji Renda Huanjie Xuanju Sange Jueding Caoan de Shuoming [Three draft decisions on the province’s municipal, county and township people’s congress general elections], The Standing Committee of Jiangsu Provincial People’s Congress, December 9. 2011. http://www.jsrd.gov.cn/zyfb/hygb/1124/201112/t20111209_64049.html;

Jiangsusheng Renmin Daibiao Dahui Changwu Weiyuanhui Guanyu Quansheng Shixianxiang Sanji Renmin Daibiao Dahui Huanjie Xuanju Wenti de Jueding [Decision of the Standing Committee of the People’s Congress of Jiangsu Province on the Election of People’s Congresses at the Three Levels of City, County and Township in Jiangsu Province], The Standing Committee of Jiangsu Provincial People’s Congress, December 9. 2011, http://www.jsrd.gov.cn/zyfb/hygb/1124/201112/t20111209_64046.shtml.

7 See footnote 1. These studies analyzed the bills and proposals submitted by delegates of the Yangzhou MPC between 2001 and 2005. Bills and proposals submitted since 2006 will be analyzed in the future.

8 Weiming Shi and Zhi Liu, Jianjie Xuanju: 346–354.

9 Weiming Shi and Zhi Liu, Jianjie Xuanju: 367–421.

Bibliography

- Gandhi, J., and R. Ruiz-Rufino. Routledge Handbook of Comparative Political Institutions. NY: Routledge, 2015.

- Kamo, T. “‘Gendai Chugoku Ni Okeru Minyi Kikan No Seijiteki Yakuwari: Dairisha, Kangensha, Daihyousha Soshite Kyouen.’ [The Political Roles of China’s Democratic Institutions: Agents, Remonstrators and Representatives, and Collaboration between Democratic Institutions.].” Ajia Keizai 54, no. 4 (2013): 11–46.

- Kamo, T. “Chinese People’s Liberation Army in China’s People’s Congresses: How the PLA Utilizes People’s Congresses.” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 7, no. 1 (2018): 35–49. doi:10.1080/24761028.2018.1498313.

- Kamo, T., and T. Hiroki. “Representation and Local People’s Congress in China: A Case Study of the Yangzhou Municipal People’s Congress.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 18, no. 1 (2013): 41–60. doi:10.1007/s11366-012-9226-y.

- Kubo, K. ““Tokushu Ni Atatte: Kenni Shugi Taisei Ni Okeru Gikai to Senkyo No Yakuwari.” [Introduction to the Special Issue: The Role of Parliament and Elections in Authoritarian Regimes.].” Ajia Keizai 54, no. 4 (2013): 2–10.

- Nakaoka, M. “Chugoku Chihou Jinmin Daihyou Taikai Senkyo Ni Okeru ‘Minshyuka’ to Genkai. [Democratization and Limits in Local People’s Congress Elections in China: Independent Candidates and Chinese Communist Party Control.].” Ajia Kenkyu 57, no. 2 (2011): 1–18.

- O’Brien, K. J. “Agents and Remonstrators: Role Accumulation by Chinese People’s Congress Deputies.” China Quarterly 138 (1994a): 359–380. doi:10.1017/S0305741000035797.

- O’Brien, K. J. “Chinese People’s Congresses and Legislative Embeddedness: Understanding Early Organizational Development.” Comparative Political Studies 27, no. 1 (1994b): 80–107. doi:10.1177/0010414094027001003.

- O’Brien, K. J. “Local People’s Congresses and Governing China.” The China Journal 61 (2009): 131–141.

- Publicity Department of the Communist Party of China. Xijinping Zongshuji Xilie Zhongyao Jianghua Duben (2016 Nianban) [General Secretary Xi Jinping Important Speech Series]. Beijing: Xuexi Chubanshe, 2016.

- Svolik, W. M. The Politics of Authoritarian Rule. NY: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Weiming, S., and Z. Liu. Jianjie Xuanju (Shang) [Indirect Election I]. Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe, 2004.

- Xi, J. “Break New Ground in China’s Major-Country Diplomacy, June 22, 2018,” the Governance of China III, 495–499. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 2020.

- Xia, M. The People’s Congresses and Governance in China: Toward a Network Mode of Governance. London: Routledge, 2005.

- Xue, L. “China’s Foreign Policy Decision-Making Mechanism and ‘One Belt One Road’ Strategy.” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 5, no. 2 (2016): 23–35.