ABSTRACT

Using the official data of the ASEAN Secretariat, this paper applies a data-based approach to present the general trends of use of legal instruments in building the ASEAN Economic Community and ASEAN integration as a whole. ASEAN has intensified the use of legal instruments in the last five decades to reach 240 signed legal instruments by December 2020. With the frequent use of supplementary instruments, ASEAN takes a gradual and practical approach to integration. Consensus remains the key principle of decision-making in making legal instruments. There is no single legal instrument signed without consensus, even in the economic pillar. By contrast, ASEAN allows phased implementation. While a majority of ASEAN legal instruments enter into force only with full membership, many instruments also allow flexible participation (i.e., effective only among certain members). Such mechanism of flexibility is probably a way to progress integration in a group of diversity while continuing to respect the consensus principle in decision-making.

1 Introduction

In 1967, the leaders of five Southeast Asian countries, namely Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand gathered in Bangkok and issued a short document with only five articles, called the Bangkok Declaration, which established the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)Footnote1 Joined by Brunei in 1984, its membership further expanded in the 1990s to include Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam.

The Bangkok Declaration stipulated the aims and purposes of the Association in a broad manner. The wording used in the document did not appear legally bindingFootnote2 With focus on cooperation, the Declaration provided for economic, social, cultural, technical, scientific and administrative spheres of cooperation. Ever since, ASEAN has deepened and substantiated its activities over the decades. In 1997, ASEAN leader issued the ASEAN Vision 2020 in which they envisioned to establish an ASEAN communityFootnote3 Several key documents to realize the Community were agreed by leaders in the 2000sFootnote4. In 2007, the ASEAN Leaders signed the Charter of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN Charter) which strengthened the legal status and streamlined the institutional setting of the Association. In the same year, the leaders adopted its first blueprint for the ASEAN Economic Community, followed by two Blueprints adopted in 2009: one for the Political Security Community and the other for the Socio-Cultural Community. Those Blueprints were succeeded by new and advanced version of blueprints in 2015, the target year of the original blueprints. As such, ASEAN has shifted, over the decades, its center of gravity from cooperation toward integration.

ASEAN has come up with many legal instruments such as treaties, agreements, arrangements, and protocols to implement these wide range of activities. Hsieh and Mercurio point out that “[a]lbeit derived from soft law origins, ASEAN states have placed their obligations in economic agreements of a hard law nature.”Footnote5 Thus, analysis of legal instruments gives us a better understanding of changing nature of ASEAN initiatives.

More and more legal scholars recently look at this volume of legal instruments. Some even call it “ASEAN Law” and provide detailed analysis about these instrumentsFootnote6 Those academic literatures, based on a legal perspective, often discuss whether and to what extent ASEAN becomes a “rule-based ASEAN.” Also, many papers analyzes the implementation and challenges thereof by specific areas of economic integration, such as air transport or financial integration.

To complement these studies, this paper applies a data-based approach to present the general trends of use of legal instruments in building the ASEAN Economic Community and ASEAN integration as a whole. By using the official data provided by the ASEAN Secretariat, this paper analyzes the general trends of the use of legal instruments in ASEAN and discusses the following questionFootnote7 What features of ASEAN integration do these trends suggest, especially to what extent ASEAN exerts flexibility in the adoption and implementation of legal instruments to address diversity in regional integration?

This paper is structured as follows. Section II explains the database, the ASEAN Legal Instruments, especially in terms of the coverage of legal instruments. The coverage itself is critically important as it indicates the ASEAN Member States’ views on which documents are legally binding. Section III shows the general trends of use of legal instruments by decade, by pillars of ASEAN community, and by elements of ASEAN Economic Community. Section IV presents the trends of those instruments by status (i.e., whether in force or not). It further analyzes the scope of application of these instruments and discusses how the consensus principle of decision-making is respected and to what extent flexible implementation is actually taken in practice. Section V concludes.

2 Database

The ASEAN Legal Instruments is an official database run by the ASEAN SecretariatFootnote8 It collects 240 legal instruments which were signed by ASEAN Member States. To be more precise, the explanatory notes of the database provides as followsFootnote9

“The Matrix covers “legal instruments”, which, within this context, is ASEAN legal instruments concluded among and between ASEAN Member States. There are various understandings and interpretations of what is considered international legal instruments. As such, the Matrix only focuses on legal instruments by which the consent to be bound is expressed through either signature of the authorized representatives of Member States or the signature is subject to ratification and/or acceptance in accordance with the internal procedures of respective Member States.” Footnote10

There are several points to note in terms of data coverage as it indicates the ASEAN’s view on legally binding documents.

First, it does not cover declarations or statements by ministers and leaders. It is because those documents, although issued or adopted by ASEAN Member States, “appear to reflect their aspirations and/or political will”Footnote11 A notable exception is the Bangkok Declaration (1967), the founding document of the ASEAN itselfFootnote12 Judging from the fact that an instrument is listed in the database, one can reasonably assume that ASEAN Member States consider it legally binding. Most importantly in the context of regional integration, the six Blueprints are not deemed legally bindingFootnote13 While two “rules” prepared under the ASEAN Charter are also incorporated via “instruments,”Footnote14 six other “rules” are not collected in the databaseFootnote15 There is no specific explanation for this exclusion.

ASEAN categorizes the legal instruments into 83 basic instruments and 157 supplementary instrumentsFootnote16 Nearly half of the listed instruments (i.e., 116) are “protocols” to amend basic legal instruments such as “agreements.” For example, the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services (AFAS) concluded in 1995 has 31 different Protocols to implement various packages or to amend the Framework AgreementFootnote17 Similarly, The ASEAN Framework Agreement on the Facilitation of Goods in Transit (AFAFGIT) has nine protocols stipulating the detailed rules. The second largest category of legal instruments after the “protocols” is “agreements” (73), followed by and 23 “arrangements” and 14 “understandings.” Just like “protocols,” “arrangements” and “understandings” are often used as supplementary documents to the “agreements”.

The frequent use of supplementary instruments indicate that ASEAN’s integration process is gradual and practicalFootnote18 Services liberalization is a good example. While the basic legal instrument (i.e., AFAS) was signed in 1995, the substances of liberalization were formed and agreed overtime by adopting protocols. The final general package under the AFAS was adopted in 2018. For the ASEAN Multilateral Agreement on Air Services, six protocols were adopted together with the main agreement in the same year. By splitting the commitments into protocols, ASEAN facilitated the implementation step by step rather than trying to implement all the obligations simultaneously.

Second, there is no clear consistency in the naming of legal instrumentsFootnote19 While “protocols” are heavily used as supplementary instruments for services and transport, the same terminology is used for basic legal instruments in dispute settlement (both political and economic issues) and tariff nomenclatureFootnote20 For the European Union, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union stipulates four types of legal instruments, i.e., regulations, directives, decisions and recommendations, each of them differs in the legal effect and procedures to adopt themFootnote21 On the other hand, the ASEAN Charter does not provide the definition of “agreements,” “protocols” or “arrangements.” Unlike the supranational nature of the European Union, there is only one method in practice, i.e., signature by leaders, ministers or the Secretary-General, for ASEAN to have legal instruments. Thus, the ASEAN legal instruments are closer to the primary legislation, rather than the secondary legislation, of the European Union which require ratification by member states. As the contexts are quite different between the two regional bodies and there is little urgent needs for ASEAN to have a clear definition of those legal instruments. As a result, the practice of legal institutions have been “fragmented and incremental”Footnote22

Third, the database does not cover sub-regional or bilateral agreements, even if they are signed by ASEAN Member StatesFootnote23 The Protocol to the ASEAN Charter on Dispute Settlement Mechanisms (Art. 1) defines the ASEAN instrument as “any instrument which is concluded by Member States, as ASEAN Member States, in written form, that gives their respective rights and obligations in accordance with international law” (underline was added by the author). Sub-regional agreements, such as the Cross-Border Transportation Agreements among the Mekong countries are not covered in this database due to limited membership although they have real impact on the groundFootnote24 A notable exception may be the “Memorandum of Understanding” for the pilot project of self-certification. Although a memorandum was signed by Brunei, Malaysia and Singapore in 2010,Footnote25 it is registered in the ASEAN Legal Instruments database because the pilot project was implemented with the endorsement of the ASEAN Economic MinistersFootnote26 Many bilateral agreements signed between ASEAN members such as tax treaties are not covered either in the ASEAN Legal Instruments.Footnote27 Interestingly, the two bilateral agreements called the “ASEAN minus X agreements” are not recognized regionally despite the fact that these agreements have legal basis in the ASEAN Framework Agreements on Services (Art. IV bis)Footnote28

Fourth, the database does not cover, in principle, the agreements between ASEAN Member States and non-ASEAN countries. Most importantly in the economic sphere, the five ASEAN+1 FTAs are not recorded in this data setFootnote29 Interestingly, on the other hand, the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (TAC), signed by ten ASEAN Member States and subsequently by 30 non-ASEAN states including Japan, the United States, the European Union, and China, is on the listFootnote30

Last, the database counts four agreements signed between the ASEAN Secretariat and Indonesia regarding the hosting of the Secretariat.

The ASEAN Legal Instruments database also provides information about (a) the place and date of signature, (b) procedures required for the instrument to enter into force as stipulated in the instrument, (c) status (e.g., whether the instrument is in force or not) and (d) date of entry into force. While some data are missing, the data is pretty comprehensive and thus provides good basis for analysis. Those instruments are classified in one of the three communities: ASEAN Political-Security Community (APSC); ASEAN Economic Community (AEC); and ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC). The description below follows this official classification.

3 General trends of ASEAN Legal instruments

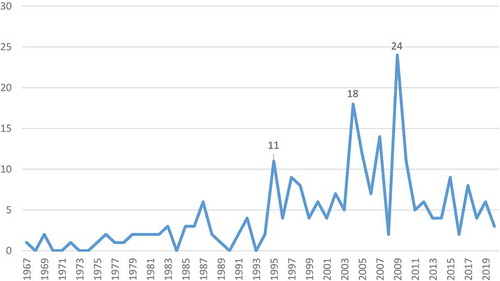

The first ASEAN legal instrument was the Bangkok Declaration adopted in 1967. Two agreements were signed in 1969, including the Agreement for the Promotion of Cooperation in Mass Media and Cultural Activities, the first agreement in the socio-cultural area.

This rather slow pace of crafting of new agreements continued in the early 1970s, when only two new instruments were introduced in five years. The first “economic” agreement, the Agreement for the Facilitation of Search for Aircrafts in Distress and Rescue of Survivors of Aircraft Accidents, was signed in 1972 but has not entered into force for almost half a century.

We started to see some pace-up after two major agreements were signed in 1976: the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia; and the Agreement on the Establishment of the ASEAN Secretariat. The former, participated not only by ASEAN members but subsequently also by many more non-ASEAN countries, functions as the fundamental document for peace in the region. The latter for the first time institutionalized the regional secretariat in Jakarta as a body to support ASEAN initiatives. The Agreement on the ASEAN Preferential Trading Arrangements inked in 1977 was also historic one with which the ASEAN made a small but first step going beyond pure economic cooperation for economic integration. In total, 10 agreements were signed between 1971 and 1980.

In the decade of 1981–1990, ASEAN has marked 22 new legal instruments. While six legal instruments were introduced for APSC, most of them regarded administrative issues of the ASEAN Secretariat or the Fund for ASEAN. In the same period, ASEAN deepened its economic cooperation with 16 newly instruments. Those cooperation projects were called ASEAN Industrial Cooperation (AICO), and ASEAN Industrial Joint Ventures (AIJV) and Brand-to-Brand Complementation (BBC), in which duty is reduced but only with the project approval by the host governments. At the same time, ASEAN introduced legal instruments for the first time in energy and tourism in the 1980s.

The real take-off happened in the decade of 1991–2000 when 50 legal instruments were inked. Many substantive economic rules were brought into the ASEAN context during this period with 44 economic instruments. In 1992, the Framework Agreement on Enhancing ASEAN Economic Cooperation was adopted. While the Agreement itself “does not contain any specific binding legal obligations on economic cooperation,” many legal instruments with specific legal rights and obligations were adopted in the next yearsFootnote31 Those instruments introduced to set up basic legal frameworks are the Agreement on the Common Effective Preferential Tariff Scheme for the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) (1992) for trade in goods; the AFAS (1995); the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Intellectual Property Cooperation (1995); and the Protocol on Dispute Settlement Mechanism (1996)Footnote32 One can reasonably assume that the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995 urged the six ASEAN Member States at the time, who were all original members for the WTO, to come up with their own agreements mirroring the WTO rules such as the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), the Agreement on the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs), and the Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes. At the same time, cooperation projects remain an important element for the ASEAN Economic Ministers' process as evidenced by supplementary and revision agreements for the AIJV and BBC. Naturally, 1995 was the first peak year with 11 newly signed legal instruments and the high trends continued until 1998. In this decade, eight APSC instruments including the Treaty on the Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone as well as two ASCC instruments were introduced.

The ASEAN leaders approved the plan to realize the ASEAN Community comprising the three pillars in 2003, which boosted the adoption of as many as 18 legal instruments in 2004Footnote33 As a result, the decade from 2001 to 2010 is the highest time with 104 newly signed instruments to realize those three communities. Those were nine legal instruments for APSC, 92 for AEC, and three for ASCC. The most important legal instrument in the APSC pillar, and much more broadly in the whole ASEAN context, was the ASEAN Charter signed in 2007. As Hsieh and Mercurio explain, the Charter “alters the nature of the legal foundation for the institutional structure of ASEAN,” by codifying the established practices and established the legal personality of ASEAN SecretariatFootnote34 This key document came into force in December 2008. Several legal instruments were signed to support the Charter, such as the Agreement on the Privileges and Immunities of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (2009) and the Protocol to the ASEAN Charter on Dispute Settlement Mechanisms (2010).

ASEAN leaders also endorsed detailed plan of actions for three communities in 2007 (AEC) and 2009 (APSC and ASCC). The original AEC Blueprint, aiming for a single market and production base, was particularly concrete in setting the policy targets and actions with specific timelines for adopting the legal instruments to deliver the targets. With the adoption of the AEC Blueprint in 2007, ASEAN intensified its efforts even more which led to the peak of 24 new instruments in 2009. The ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) (2009) was an updated version of the AFTA (1992). Unlike AFTA which primarily focused on tariff “reduction,” ASEAN aims at tariff “elimination” which was achieved in principle in 2010 for ASEAN-6 countries and 2015 for the CLMV countries. ASEAN has also updated the AIA (1998) to the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement in 2009. In addition to these fundamental agreements, ASEAN introduced an initiative to accelerate integration efforts in the twelve priority integration sectors for which 17 legal instruments were prepared. Open sky policy was also introduced with the ASEAN Multilateral Agreement on Air Services and the ASEAN Multilateral Agreement on the Full Liberalization of Air Freight Services, both signed in 2009, associated with eight protocols. Also, many arrangements for mutual recognition of professional services as well as products were introduced during this period. While at much small scale, three agreements were signed for ASCC to cover haze problem, biodiversity and disaster management.

After the peak in 2009, the pace of signing of new instruments slowed down in the 2010s (51 new instruments) to the level of 1990s (50). One may argue that, with all the efforts in the 1990s and 2000s, ASEAN has been equipped with major legal instruments covering wide range of integration agendas and hence does not need to add many more. Most new instruments were protocols and arrangements for the implementation of basic agreements or revision of those agreements. New basic agreements were introduced, however, for the movement of natural persons (2012) and electronic commerce (2019). AFAS (1995) was renovated to the ASEAN Trade in Services Agreement (ATISA) in 2020. It should be noted that many action plans were adopted to achieve the community goals of 2025Footnote35

To sum up the description above, visually shows the general trends of newly signed legal instruments in the 53 year history of ASEAN. further exhibits these figures by the three pillars of ASEAN Community and by decade. AEC has the vast majority with 198 out of 240 ASEAN legal instruments, followed by APSC (33) and ASCC (nine).

Table 1. Number of legal instruments (by year of signature and by community pillar)

Figure 1. Number of newly signed legal instruments (by year of signature)

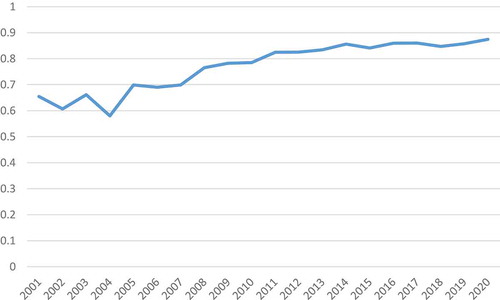

Figure 2. “In force” ratio of ASEAN legal instruments

To have a comparative view, it is useful to take a look at other regional integration initiatives in the neighborhood, namely the South Asia Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), established in 1985 with the signing of the SAARC CharterFootnote36 SAARC comprises eight Member States: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. According to the SAARC Secretariat, there are 29 legal instruments by 2020Footnote37 Thus, ASEAN takes more legalistic approach than the SAARC for regional integrationFootnote38

The 198 AEC-related legal instruments can be classified by the key elements of the AEC Blueprint 2025, which consists of: (a) a highly integrated and cohesive economy; (b) a competitive, innovative and dynamic ASEAN; (c) enhanced connectivity and sectoral cooperation; (d) a resilient, inclusive, people-oriented and people-centered ASEAN; and (e) a global ASEAN. summarizes the result.

Table 2. Number of legal instruments by the AEC elements

In this exercise, I allow double-counting or triple-counting as one instrument can contribute to different goals stipulated in the Blueprint. For example, the ASEAN Mutual Recognition Arrangement on Tourism Professionals is certainly an important document for the sectoral cooperation in tourism (C6). As the objective of the arrangement provides, at the same time, it also facilitates the movement of skilled labor (A5). The arrangement, however, has legal basis in the AFAS (A2). Similarly, seven protocols adopted under the AFAS to liberalize financial services are counted for trade in services (A2) and financial integration, financial inclusion, and financial stability (A4).

The first pillar, a highly integrated and cohesive economy, is rich in terms of the number of ASEAN legal instruments. There are 42 instruments regarding trade in services, followed by trade in goods (35), finance (14), movement of skilled labor (12) and investment (nine). One of the reasons for having so many legal instruments is a gradual approach of economic integration. In the context of services liberalization, ASEAN adopted the framework agreement to start with, followed by many protocols to implement “packages” of liberalization and “arrangements” for facilitating movement of skilled labor (i.e., mode 4 of services liberalization)Footnote39 Overtime, such approach is considered as “a good and realistic example of what the regional approach can achieve”Footnote40

Among the third pillar, enhanced connectivity and sectoral cooperation, transport has large number of agreements and protocols, i.e., 36 in total. Energy, (10), food, agriculture and forestry (nine) and tourism (five) involve good number of legal instruments.

Relative to these two pillars, the second pillar, a competitive, innovative and dynamic ASEAN, has only one agreement on intellectual property cooperation. This pillar heavily relies on action plans, e.g., “2016–2025 ASEAN Competition Action Plan” and “2016–2025 ASEAN Strategic Action Plan for Consumer Protection,” rather than legal instruments in deepening cooperation. Taxation cooperation (B5) needs special attention in this context. The AEC Blueprint 2025 urges the ASEAN Member States to sign tax treaties to avoid double-taxation. There are indeed many tax treaties among ASEAN countries. Those are not considered as ASEAN legal instruments, however, as bilateral treaties are outside the scope the regional database.

No legal instruments are registered for the fourth and fifth pillars that are recorded in the ASEAN Legal Instruments database. However, as discussed above, so-called ASEAN+1 FTAs were signed by all the ten countries. Another key development was made in November 2020. ASEAN and five partners signed a new region-wide FTA, called the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

4 “In force” vs. “not in force”

Legal instruments “in force”

The entry into force is equally and probably even more important than signing of legal agreements. According to the database, 178 legal instruments (i.e., 74.1%) are currently in force. It should be noted, however, that 37 legal instruments are recorded as “terminated,” meaning replaced by subsequent agreementsFootnote41 For example, the Framework Agreement on the ASEAN Investment Area of 1998 was replaced by the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement of 2009. If we also exclude four legal instruments for which legal status data are missing, the effectuation ratio of ASEAN legal instruments becomes as high as 89.4% (i.e., 178 out of 199).

As and show, entry into force of legal instruments took place relatively recently: 82 during 2001–2010 and 57 during 2011–2020. It is natural because many more instruments were introduced in the 1990s, 2000s and 2010s, and member states need time to ratify. It should be noted that although the figures of 1980s and 1990s look small, probably there were more instruments once in force yet terminated later on, in which case the ASEAN Legal Instruments database do not provide the date of entry into force.

Table 3. Number of legal instruments in force (by year of entry into force and by community pillar)

It took 528 days on average for ASEAN legal instruments to enter into force after signing. It does not differ much across the three pillars of ASEAN Community: 551 days for APSC; 522 days for AEC; and 552 days for ASCC. As many as 58 legal instruments came into force on the date of signature because they do not require ratification, acceptance or notification.

Some instruments took years, on the other hand, for their entry into force. The longest one was the Protocol 9 (Dangerous Goods) of AFAFGIT. The Protocol was signed on September 2 2002, and came into force on September 13, 2017. As Art. 7 of the Protocol (Final Provision) requires all contracting parties’ ratification or acceptance, although eight Member States completed their respective domestic procedures and notified the ASEAN Secretariat by 2007, they needed to wait for Thailand (2016) and Malaysia (2017), the key counties with respect to land transport. Three other AFAFGIT Protocols took more than a decade to become in force for the same reason: Protocol 3 (Types and Quantity of Road Vehicles); Protocol 4 (Technical Requirements of Vehicles); and Protocol 8 (Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures to Implement the AFAFGIT). Thailand was the last one for Protocols 3 and 4, while Malaysia was the last for Protocol 8. Just like the AEC, some APSC agreements take years for their entry into force. The Agreement on the Privileges and Immunities of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations signed in 2009 requires ratification by all the ten Member States (Art. 13). The Agreement became effective in 2017 when Malaysia completed its domestic procedures.

It should be noted here that some legal instruments are in force only among the Member States who have ratified or accepted them as further discussed later in this paper.

The frequent use of unanimous requirement for the entry into force of treaties may be a unique character of ASEAN legal instruments. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties of 1969 provides an option for unanimity requirement for the entry into force of a treaty (Art. 24(2)). As it is practically difficult, however, this method is rarely used in the United Nations multilateral treaties. Instead, Art. 24(3) of the Vienna Convention is a common practice in the United Nations, which allows a treaty to become effective only among the states who have completed their procedures for consent to be bound by it.

(2) Legal instruments “not in force”

Out of 202 ASEAN legal instruments, 21 ASEAN legal instruments are recorded as “not in force”: 20 for AEC and one for APSC.

Six of 20 “not in force” instruments pertain to trade in services. Four of them were signed relatively recently in 2017, one in 2019 and 2020, respectively, including the ASEAN Trade in Services Agreement signed in October 2020. It looks disappointing to find that the other two have been on hold for more than a decade: second package on financial services, and fourth general package. Yet newer packages were adopted and came into force subsequently for both packages, which practically cover those earlier commitments.

Other than services, those “not in force” instruments exist in areas like investment, intellectual property, transport, energy, e-commerce, and dispute settlement but only one instrument each. Transport used to have many signed but unimplemented protocols but such a problem has dramatically improved in the last five years with three protocols came into force.

It should be noted that the “not in force” status does not mean that the contents of such instruments are not implemented in reality. To give an example, the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Intellectual Property Cooperation was signed in 1995. While nine Member States completed their domestic procedure by 1999, Malaysia has not completed her process and thus the Agreements holds at the “not in force” status. Actually, however, the intellectual property cooperation of ASEAN is quite active with several regional action plans adopted in 2004, 2010, and 2015 among the ten Member States including MalaysiaFootnote42 Likewise, although the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Visa Exemption signed in 2006 is not in force yet for Malaysia’s domestic procedure is incomplete, many ASEAN countries provide visa exemption in practice to the citizens of other ASEAN members by signing and implementing bilateral agreementsFootnote43 ASEAN even tries to establish ASEAN Visa which will allow non-ASEAN citizens’ travel in ASEAN countriesFootnote44 As described above, while waiting for the entry into force of agreements, the aim of some legal instruments have already started to bear fruits via other means such as legally non-binding action plans and bilateral legal instruments.

(3) Flexible participation of ASEAN Legal Instruments

The basic principle of ASEAN’s decision-making is consensus and consultation (ASEAN Charter, Art. 20.1). Thus, as described in section II of this paper, most ASEAN legal instruments were signed by all the ASEAN Member States with the exception of legal instruments on self-certification pilot projects signed by small groups of members under the regional consensus of 10 members.

On the other hand, flexible approach is found relatively often in the implementation of legal documents. The Charter (Art. 21.2) allows for “flexible participation” where there is a consensus to do soFootnote45 Majority of ASEAN legal instruments either require or presuppose application of the rules among all members. Some instruments, by contrast, apply only among the countries who have ratified or accepted them.

There are a variety of approaches, especially in the AEC to realize the flexibility participation.

The first approach is setting a minimum membership requirement for entry into force. The ASEAN Framework Agreement on the Facilitation of Inter-State Transport was signed by ten transport ministers in 2009. The final provision (Art. 31.3) stipulates that the agreement enters into force with ratification or acceptance by at least two Member States. As a result, it became effective in 2011 but only between Lao PDR and Thailand. The Agreement by now is valid among seven countries but Brunei, Indonesia and Malaysia have not completed their domestic procedures for ratification or acceptance. Likewise, the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Multimodal Transport signed in 2005 came into force in 2008 only between the Philippines and Thailand. The Agreement is currently applied to seven countries except Brunei, Malaysia and Singapore. The minimum requirement of two members, however, is limited. Focusing on the legal instruments signed in the last twenty years (i.e., 21st century)Footnote46, the minimum requirement of three country ratification is much popular (14 legal instruments) especially in the transportation sector. Air transport services protocols tend to require at least six countries (five protocols) or seven countries (two protocols). It does not mean that some ASEAN countries do not participate in the initiatives forever. All the air transport services protocols are actually already effective among all the member states although with delays for some countries. In this, ASEAN has not become two-tiered.

This minimum requirement approach can be found in the APSC and ASCC. In the APSC, the ASEAN Convention Against Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children signed in 2015 requires only six members’ ratification for its entry into force. It became effective in March 2017 among six but soon joined by three more members in the same year. The last one to complete its domestic procedure was Brunei in 2020. The ASEAN Convention on Counter Terrorism also sets a minimum requirement of six members. An example for ASCC is the ASEAN Agreement on Trans-boundary Haze Pollution signed in 2002 came into force among seven countries in 2003. Lao PDR, Singapore and Indonesia completed their procedures in 2005, 2010 and 2015, respectively, and thus the Agreement applies among all the ASEAN members since 2015. The Agreement on the Establishment of the ASEAN Center for Biodiversity also requires six members’ ratification.

The second approach assumes full membership for entry into force but allows delays. Interestingly, some legal instruments enter into force automatically when certain number of days pass after the date of entryFootnote47 Although Member States are expected to complete their respective national procedures before the “deadline,” they become effective even if some members are unsuccessful. In such cases, the legal instruments apply to the late comers only after they complete their ratification or acceptance requirement. Financial package protocols of AFAS often apply this methodology.

The third approach is opt-in or opt-out often found in the mutual recognition arrangements for professional services. Taking an example, the ASEAN Mutual Recognition Arrangement on Engineering Services was signed in 2005 by all the members. The Arrangement came into force on the same date of signature automatically (Art. 8.2). “[Any] ASEAN Member Country which wishes to participate in this Arrangement […] shall notify the ASEAN Secretary-General in writing […]” (Art. 8.3). In other words, this arrangement takes an “opt-in” approach. Although all the members taken steps to join this endeavor by now, the year of participation differs from 2006 to 2013. An “opt-out” approach is taken for mutual recognition arrangements for professional qualification in the healthcare and accountancy service.

In sum, there are many ways to allow flexible participation across the three pillars. Out of 178 legal instruments in force, 41 apply only among limited member states.

It should be noted here that flexible participation does not mean that ASEAN are split between two groups with different speed of implementation. Many legal instruments which became effective only among limited members once are now effective among the full membership. In other words, ASEAN Member States often complete their domestic procedures to implement the agreed rules at the end of the day, while sometimes with long delay. The latest mover differs from an instrument to another. Thus, such flexible mechanism can be understood as a means to progress integration in a regional group consist of diverse members.

(4) Consensus-based decision-making and flexible participation in ASEAN

The analysis in this paper suggests ASEAN’s strong preference for unity and unanimity. When signing legal instruments, ASEAN adheres to the consensus-based decision making. Indeed, almost all the ASEAN legal instruments are signed by all the members. Although limited exception can be found in the protocols for self-certification pilot projects, these projects are recognized by the economic ministers of all the ten countries. Bilateral or sub-regional agreements, including the two “ASEAN minus X agreements” signed by two member states for services liberalization, are not listed in the ASEAN legal instrument database and thus are not recognized as ASEAN agreements. This practice differs from the European Union’s “enhanced cooperation”Footnote48 As stipulated in Art. 20 of the Treaty of European Union, the enhanced cooperation refers to an initiative by limited membership of at least nine countries. The decision at the Council is voted only by the members representing the Member States participating in the enhanced cooperation (Art. 20(3)). While the ASEAN Charter provides for an option other than consensus (Art. 20) for decision-making, it has never been invoked.

When implementing the legal instruments which are approved by consensus of the ten countries, ASEAN in general sticks to the unanimity by requiring full member participation before entry into force, which is not a typical practice of multinational treaties in the United Nations. On the other hand, flexible participation mechanism is applied in terms of implementation of consensus-based instruments. This flexibility measure can be found not only in economic but also political-security and socio-cultural agreements.

5 Conclusion

Using the official data of the ASEAN Secretariat, this paper applies a data-based approach to present the general trends of use of legal instruments in building the ASEAN Economic Community and ASEAN integration as a whole.

ASEAN heavily uses legal instruments in progressing its integration efforts. Such approach intensified in the 1990s due to the establishment of the WTO. ASEAN further accelerated the use of legal instruments in the 2000s. Although the adoption of the ASEAN Charter in 2007 was a key turning point for ASEAN’s shift toward a rule-based regional initiative, the leaders’ vision for the ASEAN Community as well as the three Blueprints was also a critical factor. By December 2020, as many as 240 legal instruments were signed. 198 of 240 legal instruments focus on the economic sphere where ASEAN takes a “slow but practical” approach as evidenced by the frequent use of supplementary instruments.

Nearly 90% of these ASEAN legal instruments have actually entered into force. ASEAN instruments take 528 days on average from signing to entry into force while some took more than a decade for the effectuation.

Consensus remains the key principle of decision-making in making legal instruments. There is no single legal instrument signed without consensus, even in the economic pillar. By contrast, ASEAN allows phased implementation. While a majority of ASEAN legal instruments enter into force only with full membership, many instruments also allow flexible participation (i.e., effective only among certain members). Such mechanism of flexibility is probably a way to progress integration in a group of diversity while continuing to respect the consensus principle in decision-making.

Entry into force of legal instruments will not be sufficient in realizing the high ambition of ASEAN Community. To ensure compliance with the agreed rules by member states, the existence of dispute settlement mechanism is criticalFootnote49 Here, ASEAN has engineered several legal instruments on dispute settlement. For political security, the Protocol to the ASEAN Charter on Dispute Settlement Mechanisms was signed in 2010, followed by two supplementary instruments. For the disputes on economic matters, ASEAN has renewed its original protocol of 1996 for three times. The latest revision took place in 2019 which address shortfalls of the 2004 protocolFootnote50 The 2019 protocol applies to disputes arising from 105 AEC instruments and future agreements. As those mechanisms, either political or economic, have never been invoked, it is not clear whether they actually function. However, the regular revision of dispute settlement mechanisms indicate a strong will of ASEAN in adhering to the rules set in the legal instruments.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yoshifumi Fukunaga

Yoshifumi Fukunaga is a Consulting Fellow of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry. He received LL.M. from Harvard Law School and M.A. (International Relations) from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University.

Notes

1 ASEAN Secretariat’s Website, “History”, available at https://asean.org/asean/about-asean/history/(last access on December 14 2020)..

2 Ewing-Chow and Tan, “The Role of the Rule of Law in ASEAN Integration”, 11. Legal scholars often see the Declaration as legally non-binding. Interestingly, however, the ASEAN countries by now recognizes the Declaration as the first legal instrument of ASEAN as discussed in this paper..

3 ASEAN Vision 2020, adopted at the ASEAN Summit on December 15 1997.

4 Charter of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN Charter), signed on November 20, 2007, available at https://asean.org/storage/November-2020-The-ASEAN-Charter-28th-Reprint.pdf; ASEAN, ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint; ASEAN, ASEAN Political Security Community Blueprint; and ASEAN, ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community Blueprint.

5 Hsieh and Mercurio, eds., ASEAN Law in the New Regional Economic Order, 416.

6 For example, Ibid; Desierto and Cohen, eds., ASEAN Law and Regional Integration.

7 Tan, “ASEAN Law: Content, Applicability, and Challenges,” at 41. Tan uses older version of the ASEAN Legal Instruments matrix as of 2015 which covered 81 instruments.:

8 ASEAN Legal Instrumets, available at https://agreement.asean.org/ (last access on March 25, 2021). The National University of Singapore (Center for International Law) also creates a comprehensive database (NUS Database) on ASEAN’s public documents including legal instruments..

9 ASEAN Legal Instruments, “Explanatory Notes”, http://agreement.asean.org/explanatory/show.html (last access on December 13 2020), para 1.:

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid. It should be noted, however, the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties of 1969 provides that “‘treaty’ means an international agreement […] whatever its particular designation”. Thus, those declarations and statements could be deemed legally binding by international tribunals..

12 See supra note 2.

13 The original AEC Blueprint (2007) was actually signed by the leaders. For the other blueprints, the leaders signed the declarations, the Cha-Am Hua Hin Declaration on the Roadmap for an ASEAN Community (2009–2015) and the Kuala Lumpur Declaration on ASEAN 2025: Forging Ahead Together, but not the Blueprints..

14 Those are: (a) Instrument of Incorporation of the Rules for Reference of Unresolved Disputes to the ASEAN Summit to the Protocol to the ASEAN Charter on Dispute Settlement Mechanisms; and (b) Instrument of Incorporation of the Rules for Reference of Non Compliance to the ASEAN Summit to the Protocol to the ASEAN Charter on Dispute Settlement Mechanisms.

15 NUS database lists eight “rules”..

16 While the ASEAN database clearly distinguishes all the legal instruments to two categories, it does not use the wordings of “basic” and “supplementary”. Kuijper, Mathis and Morris-Sharma, From Treaty-making to Treaty-breaking, 6. The authors call them as “core agreements” and “related or collateral” agreements. Tan, “ASEAN Law: Content, Applicability, and Challenges,” at 41, refers to “81 key legal instruments”..

17 Here I count not only protocols to implement general packages but sectoral packages on financial and air transport services..

18 Lee, “ASEAN Air Transport Integration and Liberalization”, 200–201. By finding the good results albeit slow progress in ASEAN’s air transport integration, positively values the ASEAN’s approach as a “gradual approach”..

19 Desierto and Cohen, ASEAN Law and Regional Integration, xiv. The authors further points out that “ASEAN does not have a coherent set of ‘rules,’ nor any mechanism for their authoritative drafting, adoption, interpretation and implementation.”.

20 This problem is a present one. The ASEAN Protocol on Enhanced Dispute Settlement, a basic instrument, was signed in 2019, while several protocols are inked in the same year as supplementary instruments in the areas of trade in goods and services..

21 European Union, “EU Legal Instruments”, available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/summary/glossary/community_legal_instruments.html (last visit on March 13, 2021)..

22 Kuijper, Mathis and Morris-Sharma, From Treaty-making to Treaty-breaking, 6..

23 There are three major sub-regional cooperation initiatives within ASEAN: Brunei-Indonesia-Malaysia-Philippine East Growth Area (BIMP-EAGA), Indonesia-Malaysia-Thailand Growth Triangle (IMT-GT) and the Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS)..

24 Asian Development Bank (2011), “Greater Mekong Subregion Cross-Border Transport Facilitation Agreement: Instruments and Drafting History”, Manila: Asian Development Bank.”.

25 Memorandum of Understanding between the Governments of the Participating Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) on the Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self-Certification System, signed on August 30 2010. There is one more legal instrument regarding the self-certification project with partial membership.

26 ASEAN, “Joint Media Statement of the 42nd ASEAN Economic Ministers’ Meeting,” Da Nang, Viet Nam, August 23–25, 2010..

27 Tan, “ASEAN Law: Content, Applicability, and Challenges.” 43–44.

28 Those two agreements are: (a) ASEAN-X Agreement between the Governments of the Republic of Singapore and Lao PDR on Education Services, singed on December 9 2005; and (b) Agreement between the Governments of Brunei Darussalam and Singapore to Further Liberalize Trade in Telecommunication Services, signed on September 10 2014..

29 Those are: (a) ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Agreement; (b) ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement, (c) ASEAN-India Free Trade Agreement; (d) ASEAN-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, and (e) ASEAN-Korea Free Trade Agreement. Hong Kong, China also has a similar agreement as an independent customs territory..

30 Three protocols to amend the TAC are also listed in the database..

31 Ewing-Chow and Tan, “The Role of the Rule of Law in ASEAN Integration”, 6..

32 This 1996 protocol applies only to economic disputes (Art. 1.1)..

33 Declaration of ASEAN Concord II (Bali Concord II), adopted on October 7 2003..

34 Hsieh and Mercurio, eds, ASEAN Law in the New Regional Economic Order, 5..

35 ASEAN (2018). The consolidated action plan refers to many sectoral action plans for instance about trade in goods (Strategic Action Pan for Trade in Goods (2016-2025), trade facilitation (AEC 2025 Trade Facilitation Strategic Action Plan), services (Strategic Action Plan for Services 2016-2025), financial integration (AEC Strategic Action Plans for Financial Integration 2016-2025), competition (ASEAN Competition Action Plan (2016-2025)), consumer protection (ASEAN Strategic Action Paln for Consumer Protection 2016-2025), intellectual property (ASEAN Intellectual Property Rights Action Plan 2016-2025), taxation (Strategic Action Plan 2016-2025 for ASEAN Taxation Cooperation), minerals (ASEAN Minerals Cooperation Action Plan 2016-2025) and SME development (Strategic Action Plan for SME Development 2016-2025)..

36 SAARC Secretariat, “About SAARC”, available at https://www.saarc-sec.org/index.php/about-saarc/about-saarc (last access on December 18 2020)..

37 SAARC Secretariat, “Agreements and Conventions”, available at https://www.saarc-sec.org/index.php/about-saarc/about-saarc (last access on December 18, 2020)..

38 Due to the huge difference in the nature of integration, a simple comparison with the European Union could be misleading, as many scholars point out. Having this said, the European Union introduced, in the year of 2020, 163 regulations, 16 directives and 763 decisions. European Union, legal acts – statistics, available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/statistics/legal-acts/2020/legislative-acts-statistics-by-type-of-act.html (last access on March 10 2021)..

39 GATS (Art. I) provides the definition of four modes of trade in services. “Mode 4” refers to the presence of natural persons..

40 Lee, “ASEAN Air Transport Integration and Liberalization”, 203–204..

41 It is not clear from the database that these “terminated” instruments entered into force before replaced by newer legal instruments..

42 Those are: (a) ASEAN Intellectual Property Right Action Plan 2004–2010, (b) ASEAN IPR Action Plan 2011–2015 and (c) ASEAN IPR Action Plan 2016–2025..

43 The outcome documents of the Meeting of the ASEAN Directors-General of Immigration Department and Heads of Consular Affairs Division of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs (DGICM) used to mention the ratification status of the regional agreement as well as signing of bilateral agreements. The Philippines and Singapore completed their ratification/acceptance processes in 2018..

44 ASEAN, ASEAN Political Security Blueprint 2025, 4..

45 ASEAN Charter (Art. 21.2) refers to the “ASEAN minus X formula.” Although the definition of such formula is not provided in the Charter, it is evident that the formula is a way for flexible implementation rather than flexible decision-making..

46 This is because of membership expansion in the late 1990s. For the agreements of the 1980s, “six” meant full membership.

47 This automatic entry into force certain days after the signing can be found in five instruments for 90 days and six instruments for 180 days. Some other instruments provide fixed date for the entry into force..

48 Aimsiranun, “Comparative Study on the Legal Framework on General Differentiated Integration Mechanism”. While Aimsiranum also uses the pathfinder initiatives of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) as an example of differentiate integration mechanism, this aspect is not relevant in this paper because APEC does not develop legal instruments in the first place..

49 Hsieh and Mercurio, ASEAN Law in the New Regional Economic Order, 416, explains that ASEAN also uses other means to ensure compliance by its member states..

50 For detail, see Sim, “ASEAN Further Enhances Its Dispute Settlement Mechanism.”.

Bibliography

- Aimsiranun, U., “Comparative Study on the Legal Framework on General Differentiated Integration Mechanism,” ADBI Working Paper Series No. 1107, 2020

- ASEAN, “ASEAN Economic Community 2025 Consolidate Strategic Action Plan”, endorsed by the ASEAN Economic Ministers Meeting and the ASEAN Economic Council on February 6, 2017 and updated on August 14, 2018. Accessed January. 20, 2021. https://asean.org/storage/2017/02/Consolidated-Strategic-Action-Plan.pdf.

- ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint, Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, 2007.

- ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN Political-Security Community Blueprint, Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, 2009a.

- ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN Socio-Cultural Blueprint, Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, 2009b.

- ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN Political-Security Community Blueprint 2025, Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, 2015a.

- ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN Economic Blueprint 2025, Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, 2015b.

- ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN Socio-Cultural Blueprint 2025, Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, 2015c.

- ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN Services Report 2017, Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, 2017.

- Desierto, D. A., and D. J. Cohen, eds. ASEAN Law and Regional Integration: Governance and the Rule of Law in Southeast Asia’s Single Market. Abingdon: Routledge, 2021.

- Hsieh, P. L., and B. Mercurio, eds. ASEAN Law in the New Regional Economic Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Kuijper, P. J., J. H. Mathis, and N. Y. Morris-Sharma. From Treaty-Making to Treaty-Breaking: Models for ASEAN External Trade Agreements. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Lee, J. W. “ASEAN Air Transport Integration and Liberalization: A Slow but Practical Model.” In ASEAN Law in the New Regional Economic Order, edited by P. L. Hsieh and B. Mercurio, 186–206. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Ewing-Chow, M., and H.-L. Tan. “The Role of the Rule of Law in ASEAN Integration”, EUI Working Papers RSCAS 2013/16, European University Institute, 2013.

- United Nations,Final Clauses of Multilateral Treaties Handbook, 2003. Accessed on March 10, 2021. https://treaties.un.org/doc/source/publications/FC/English.pdf.

- ASEAN Secretariat,“ASEAN Legal Instruments,” available at https://agreement.asean.org/(last access on Dec 6, 2020).

- Sim, E. “ASEAN Further Enhances Its Dispute Settlement Mechanism.” Indonesia Journal of International and Comparative Law 7, no. April (2020): 279–292.

- Tan, K. Y. L. “ASEAN Law: Content, Applicability, and Challenges.” In ASEAN Law and Regional Integration: Governance and the Rule of Law in Southeast Asia’s Single Market, edited by D. A. Desierto and D. J. Cohen. Abingdon: Routledge, 2021, 39-56.