ABSTRACT

Notwithstanding their asymmetry in size and power, Singapore and the People’s Republic of China enjoy a “special relationship” based on cultural affinity and close economic interdependency. The city-state was also a model of development for its giant neighbor after the latter abandoned Maoist autarchy and embarked on the road of reform. But their ties are also awkward because Singapore is strategically close to the US superpower which views a rising and rivaling China with suspicion. Singapore’s relations with Beijing may become even more awkward during an uncertain power transition in East Asia amid the bitter Sino-US decoupling over trade, technology, finance and human talent.

1 Introduction

Singapore’s relationship with China is unique. It is the only country outside Northeast Asia where 76% of its population is of ethnic Chinese descent. This is potentially a double-edged sword: many Singaporean Chinese have a comparative advantage in language and culture when they interact and do business with their ancestral kin in the Chinese Mainland. This ethnic link not only creates potential challenges for Singapore’s multi-ethnic and multicultural national identity as a young nation, but also complicates international relations between Singapore and Beijing, and possibly between Singapore and its immediate neighbors Malaysia and Indonesia. Simply put, Singapore, as a founding member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), cannot appear to be a “Third China” in Southeast Asia.

Marking their 30 years of official diplomatic relations in 2020, Beijing’s most senior diplomat Yang Jiechi visited Singapore in August and held discussions with Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong. Both countries resolved to cooperate amid the global COVID-19 pandemic. But their long-term bilateral relationship may be increasingly challenging as China and the US are engaging in a “New Cold War” amid their decoupling of trade, technology, finance and human talent exchange.

Another awkward aspect is the fact that Singapore is walking the strategic tightrope between the US superpower and a rising China. The city-state’s balancing act can be interpreted as a strategic alignment with the US on the one hand, and conscious deepening of its economic ties with the Chinese Mainland on the other. If the East Asian regional order continues to become increasingly bipolar in the 21st century, then Singapore may concomitantly become more uncomfortable as a small state caught between giants. It may be astonishing to note that Singapore has been the largest foreign investor in the world in Mainland China since 2013. Moreover, the city-state was a development model for post-Mao China and has trained more than 55,000 Chinese officials in good governanceFootnote1 No other country in the world has trained Chinese bureaucrats on such a large scale. However, Singapore’s economic closeness to China is no guarantee that its geopolitical relations with this humongous neighbor will be smooth sailing and cordial in the years ahead.

Another tricky and potentially thorny aspect of Sino-Singapore relations is the latter’s close unofficial relations with Taiwan – considered by Beijing to be a renegade province. A major dip in their bilateral relationship was when then Deputy Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong visited Taiwan in 2004 and Beijing went on to freeze official bilateral relations for about a year. Singapore is the only country in the world to conduct regular military exercises in Taiwan and has been doing so since 1975 due to the former’s lack of physical space and military training ground. But Singapore has also provided a useful and neutral platform for the 1993 Wang-Koo Talks between both sides of the Taiwan Strait, and for Xi Jinping and Ma Ying-jeou to hold a historic summit in November 2015.

However, presumably at the behest of Beijing, the Hong Kong port authorities impounded nine Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) Terrex armored vehicles en route to Singapore after their military training in Taiwan in November 2016, and only released them after two months. Apparently, Beijing was unhappy with Singapore’s affirmation of international law and freedom of navigation as fundamental principles in the disputed South China Sea, and displeased with its annual military exercises in Taiwan. Notwithstanding their “special relationship”Footnote2, bilateral ties hit a low point when Beijing’s Hong Kong underlings seized the Terrex vehicles. Obviously, China willfully put Singapore in an awkward and tight spot in that incidentFootnote3

My central argument is that the so-called special relationship between Singapore and China is mutually beneficial, but sometimes ambivalent and awkwardFootnote4 In the midst of the power transition in East Asia (in light of a rising China coupled with the US superpower in relative decline) and the “trade war” between the two giants, this unique state of affairs in Sino-Singapore relations may become even more “awkward” and difficult for the city-state.

This article adopts the four-factor analysis to explain this awkward “special relationship” in Singapore-China relations. The first section explores their geostrategic relations in the Cold War and post-Cold War eras. The next section analyzes China and Singapore’s unique economic ties. It will be followed by an examination of the city-state’s domestic politics and public opinion, and their impact on this so-called special relationship. The conclusion is that Singapore will probably be less appealing to China in the years ahead because the city-state’s economic resources and model of governance will be deemed less useful by a more powerful, confident and hubristic China. While bilateral ties may be less “special” in the future, the giant and the pigmy can still find common interests and mutual benefits.

2 Geopolitics

2.1 Cold war bipolarity: China and Singapore on the same side against USSR-vietnam

Singapore attained self-governance (except in matters pertaining to foreign affairs and defense) from its British colonial master in 1959. Subsequently, Singapore joined the Federation of Malaysia as a component state in 1963. After two acrimonious years, Singapore left Malaysia and became an independent country. But Singapore did not establish diplomatic relations with China until October 1990. It was Singapore’s policy not to establish diplomatic relations with Beijing until Jakarta had done so, as it wished to avoid giving the misimpression to the city-state’s Malay neighbors that Singapore is a “Third China” in Southeast AsiaFootnote5

During the Cold War era, Singapore was formally nonaligned. In reality, it was a noncommunist state with good relations with the US. Throughout the Cold War and post-Cold War eras, the city-state perceived the US as a superpower maintaining the regional balance of power in Southeast Asia. The US is also a key supplier of Singapore’s weapon systems.

The city-state was suspicious of China extending support to the Malayan Communist Party, which was then conducting violent armed struggle in MalaysiaFootnote6 Until 1978, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was extending material, moral and ideological support to various communist parties in Southeast Asia. Singapore’s perennial ruling party, the People’s Action Party (PAP), alleged that its main domestic political rival and opposition party, Barisan Socialis, was supported by communist united front organizations in Singapore. Nevertheless, Singapore traded with China in the 1960s and subsequent decades, and allowed the Bank of China to operate in the city-state.

Singapore supported China’s entry to the UN in 1971, even though they did not have diplomatic relations. The rupture in the Sino-Soviet alliance in 1960s and China’s Three World Theory in the late 1970s impacted Beijing’s strategic calculations and relations with Southeast Asia, including Singapore. China sought a United Front with the US, Europe and the Third World (including ASEAN states) against the USSR and its junior ally Vietnam (after the latter’s invasion of Cambodia in 1978).

The turning point in Sino-Singapore relations in the Post-Mao era was Paramount Leader Deng Xiaoping’s November 1978 visit to Singapore and China’s subsequent adoption of reforms resulting in the Open Door Policy that same year. Apparently, Deng was impressed by Singapore’s successful economic development and good social order. Deng also sought Singapore’s participation in a United Front against Vietnam and the Soviet Union. Then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew told Deng Xiaoping that China must stop supporting communist insurgencies in ASEAN states if it truly desired better relations with them. Singapore’s economic doyen and former Deputy Prime Minister Goh Keng Swee was Economic Adviser to the State Council of the People’s Republic of China on coastal development and Adviser on tourism in the 1980s.

Post-Mao China during the Cold War era did not criticize Singapore for maintaining a close strategic alignment with the US superpower. Simply put, China, the US, Japan, Singapore and other ASEAN countries were on the same side against the Soviet Union and Vietnam during that era. Singapore and other ASEAN countries did not criticize China when it clashed with Vietnam in the South China Sea in 1988 because they viewed that Sino-Vietnamese maritime conflict within the context of the Cold War.

After the 1989 Tiananmen Square Incident, the West ostracized China for a few years, but Singapore, like other ASEAN countries, did not. Then Chinese Premier Li Peng, notorious for the Tiananmen crackdown, visited Singapore in August 1990 to break through the diplomatic isolation by the West. Interestingly, Li Peng’s visit took place before official diplomatic relations were established in October that year.

2.2 Post-cold war era: Singapore between China and the US

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the US and China lacked a common enemy and were no longer strategically aligned. That Singapore continued its close strategic alignment with US is conceivably a potential problem for Singapore-China relations if Sino-US relations were to deteriorate. In the 1990s, after the Philippines asked the US military to leave Clark Air Base and the Subic Bay Naval Base, Singapore provided facilities to the US military on a rotational basis to enable it to maintain a strategic presence in Southeast Asia. These include:

A squadron of US fighter planes in Singapore

US aircraft carrier fleet’s visitation of Singapore’s Changi Naval Base

US combat littoral ships in Singapore

US Navy Poseidon P-8 maritime surveillance aircraft in Singapore

The US military’s access to facilities in Singapore is codified by the 1990 MOU (Memorandum of Understanding), the 1998 Addendum to the 1990 MOU extending the use of Changi Naval Base to the US, the 2005 Strategic Framework Agreement for a Closer Cooperation Partnership in Defense and Security, under which Singapore and the US became Major Security Cooperation Partners, and the 2015 DCA (Defense Cooperation Agreement) which provided a new framework for Singapore-US defense relations. Under this framework, both sides expanded existing defense cooperation in military, policy, strategic, technology and non-conventional security areas; and agreed to new areas of non-conventional cooperation, including humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, cyber defense, biosecurity and communications. In September 2019, the city-state and the US signed the Protocol of Amendment to the 1990 MOU, for US forces to enjoy an extension of another 15 years.

Simply put, Singapore supports the US’s “rebalancing” in East Asia to the chagrin of China. Apparently, Beijing became more annoyed with Singapore’s close strategic alignment with the US when the latter grew more critical of Chinese artificial islands in the disputed South China Sea. While Sino-Singapore ties are generally cordial, it is obviously asymmetrical in terms of power and size.

Take, for example, the July 2010 ASEAN Regional Forum meeting in Hanoi where China openly demonstrated its displeasure with Singapore over the South China Sea issue: “At one point, Yang Jiechi (Chinese Foreign Minister) mocked his hosts, the Vietnamese; at another, he declared, ‘China is a big country and other countries are small countries, and that’s just a fact.’ Yang stared down the foreign minister of Singapore, a country known in the region as one of America’s staunchest friends. The Singaporean foreign minister, a normally placid man named George Yeo, stared right back.”Footnote7 That obviously was another awkward moment for Sino-Singapore ties.

Notwithstanding their differences in outlook toward the disputed South China Sea and the hiccup in their ties over the seizure of the SAF’s Terrex vehicles in Hong Kong, both countries have adopted a friendship paradigm and pragmatically kept their relations on an even keel. Interestingly, China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the SAF have been conducting modest joint military exercises since November 2010. In October 2019, the city-state and Beijing upgraded a defense pact that will include frequent high-level dialogs and larger scale military exercises and interactions involving all three arms of their military – - the army, navy and air force. The city-state was also the coordinator of the ASEAN-China Dialogue between 2015 and 2018. Both countries established the Joint Council for Bilateral Cooperation (JCBC) – the highest-level forum between China and Singapore – which meet on an annual basis.

3 Economics: ties that bind?

Economic cooperation is central to Singapore’s strategy to accommodate and harness China’s rise for its own purposeFootnote8 A distinction should be made between the Singapore state, its corporate sector and Singaporean society when discussing their orientations toward China. As noted earlier, Singapore’s foreign policy approach is essentially one that seeks a geostrategic alignment with the US superpower while deepening economic ties with China. However, the Singapore corporate world, including bankers, property developers, entrepreneurs in industrial parks and investors in China, are primarily interested in profits rather than politics. The Singapore public, especially the Singaporean Chinese, is primarily interested in culture and tourism in the Mainland.

3.1 Three government-to-government economic projects: Singapore’s model of development

Singapore and China have three state-level projects in the Mainland: Suzhou Industrial Project, Tianjin Eco-city and Chongqing Connectivity. This mode of economic cooperation, with Singapore taking the lead, is unrivaled by any other country doing business in China. In 1992, Paramount Leader Deng Xiaoping broached the idea of developing a modern industrial township with Singapore experience. During his tour of southern China that year, Deng said: “Singapore enjoys good social order and is well managed. We should tap on their experience, and learn how to manage better than they do.” (Washington Post, March 23 2015).

After rounds of discussions, both governments established the China-Singapore Suzhou Industrial Park (CS-SIP) in February 1994. The idea was to transfer the Singapore “software” of management to its Chinese students, who would then replicate this model in other parts of China. In September 2008, the groundbreaking ceremony of Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-city – a project for the joint development of a socially harmonious, environmentally friendly and resource-conserving city in China – took place. The third government-to-government project was the Chongqing Connectivity Initiative launched in November 2015. This included a Chongqing Logistics Development Platform, the Multi-Modal Distribution and Connectivity Center, and the development of a Southern Trade Corridor running from Chongqing to the ASEAN countries via the port city of Qinzhou in southern Guangxi province.

The city-state is also a keen supporter of Beijing’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Singapore supports both these Chinese signature projects, despite US reservations on China extending its geostrategic influence through these schemes. Singapore Home Affairs and Law Minister (and former Foreign Minister) K. Shanmugam noted: “One-third of China’s total ‘Belt and Road’ related investments in all countries is in Singapore. In return, Singapore’s investments in China account for 85% of the total ‘Belt and Road’ investments made by all countries there.” (Straits Times, August 28 22017).

3.2 Trade, investments and tourism

In a landmark development, Singapore became China’s largest investor country for the first time in 2013 when its investments in China hit US$7.23 billion. The Singapore media reported in 2015: “For the second consecutive year, Singapore was China’s largest foreign investor with investments amounting to US$5.8 billion in over 700 projects last year. At the same time, Singapore is China’s largest investment destination in Asia, and one of the top investment destinations for Chinese companies investing abroad.” (Business Times, November 6 2015). By the end of 2014, Singapore’s cumulative foreign direct investment in China totaled US$72.3 billion. Investments are a two-way street between the Chinese Mainland and the city-state. By 2017, Singapore surpassed the United States to emerge as the top destination for overseas investments from China.

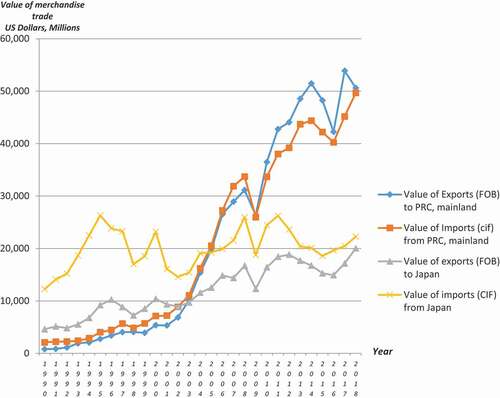

Then Singapore President Tony Tan noted that China is Singapore’s largest trading partner, with trade growing more than twenty-fold between 1990 and 2014. reveals that as the Chinese economy grew inexorably, Singapore’s trade with China rapidly outstripped that of Japan’s, even though the latter is the third largest economy in the world. The Chinese Mainland also has the most visitor arrivals to Singapore with 3.42 million people. (Channel News Asia, February 13 2019). According to the Singapore Tourism Board, Chinese visitors accounted for about 20% of total international visitor arrivals. But this is a double-edged sword. The 2020 Wuhan viral pandemic and a ban on outbound group tours from China hit the city-state’s tourism sector very badly. This viral crisis also hit some Singapore companies exposed to the Chinese domestic market rather hard. (Straits Times, February 3 2020).

Chinese FDI to Singapore is still relatively small compared to US cumulative investments. By end 2018, Chinese cumulative investment in the city-state was S$41.8 billion (US$31.4 billion) compared to US$292.5 billion. (The Star, December 2 2019). Amid Sino-US tension over trade and technology and political turmoil in Hong Kong, Singapore is becoming a hub in Southeast Asia for Chinese technological giants like Tencent, Alibaba and Tiktok owner ByteDanceFootnote9

From the perspective of trade, investment and tourism, Sino-Singapore economic relations are certainly impressive. But there is a potential strategic problem for Singapore state and society in the future: when China becomes number one economically, will Singapore become dependent on Beijing? Because of economic gains and cultural affinity, it is conceivable that the PRC may use economic “carrot and stick” in its relations with Singapore in the future. There is a real danger that Beijing could harness the corporate world and public opinion (especially Singaporean Chinese) as its United Front strategy for geo-strategic and economic gains.

Historically, China has always leveraged the so-called Overseas Chinese for its own strategic and economic interests. Indeed, this approach has continued under Xi Jinping leadershipFootnote10 Apparently, sentiments of some members of the Singapore Business Federation, Singaporean investors in China and the Singapore general public were critical of the Singapore government’s principled position on international law and the disputed South China SeaFootnote11 They probably feared, rightly or wrongly, that offending a rising China in international affairs might jeopardize their corporate and private profits. An exceptionally close economic relationship between Beijing and Singapore, as evidenced by the unique three state-to-state projects, is no guarantee that the Chinese giant will not come down hard on the Singaporean midget if offended. The seizure of the SAF’s Terrex armored vehicles in Hong Kong is a rude reminder of this hard truth in international relations.

Conceivably, China can wield the economic stick if Singapore were to give offense. But thus far, Beijing had not resorted to such coercive measures and the city-state’s vulnerability to Chinese economic pressure should not be exaggerated because its trade is global and broad based. Indeed, Singapore is less dependent on China economically than Taiwan or Hong Kong. Moreover, it has huge national reserves estimated at more than Singapore $1 trillion (US$720 billion) – - a substantial war chest which can tide over economic pressure from any great powers.

4 Domestic politics: regime-type, ideology and identity toward China

The perennial one party-dominance of the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) since 1965 and the towering influence of founding father Lee Kuan Yew have profoundly shaped Singapore’s foreign policy toward China. Lee Kuan Yew was prime minister from 1959 to 1990. He then remained in the Cabinet as Senior Minister and later as Minister Mentor until 2011. His son Lee Hsien Loong has been prime minister since 2004. It is no exaggeration to say that the foreign policy template of Singapore toward China is deeply influenced by Lee Kuan Yew’s brilliant and shrewd geostrategic thinking.

No alternation of political parties in power and weak opposition parties in parliament mean that the PAP’s leadership of the city-state’s foreign policy toward China is unchallenged at home. The consequence of perennial one-party dominance is that the military, bureaucracy, mass media, labor unions, business corporations and ethnic clan associations have rarely voiced any public criticisms of the PAP’s approach toward Beijing. Indeed, the PAP’s status as the city-state’s long-term, dominant party means that Singapore’s foreign policy toward China is marked by both profound continuity and lack of domestic contestation.

Singapore’s national ideology and identity is of a multicultural, multiethnic, meritocratic state.Footnote12 For the city-state’s domestic ethnic harmony, the island cannot be seen as favoring ethnic Chinese or being pro-China; so doing would lead to disquiet among Singaporean Indians and Malays, and may result in their repudiation of the ruling party during the general elections. Conceivably, too close a cultural relationship with a rising China may result in “Chinese chauvinism” among some Singaporean Chinese, leading to problems for Singapore’s multi-ethnic national identity. To counter that, Singapore therefore seeks to maintain balanced and good relations with India, Malaysia and Indonesia.

In the 1980s, then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew flirted with Asian values, and promoted Confucian values as an antidote to Western liberal democracyFootnote13 But promotion of Confucian values in schools among Singaporean Chinese was a very controversial public policy, as it created a backlash from non-Chinese ethnic minorities in Singapore as well as English-speaking and Christian Singaporean Chinese. The advocacy of Confucianism in schools was subsequently dropped.

The Singapore public today is mostly concerned about bread-and-butter issues, and thus appear to have little interest in international relations. Presumably, members of the general public in liberal democracies are likely to have a louder voice in foreign policy, but Singapore is not a liberal democracy. Foreign policy toward China is basically elite-driven by the top leaders of the perennial party-in-power (i.e., the PAP) and the foreign policy bureaucracy.

5 Mass public opinion, elite opinion, ethnicity, culture, values and identity

Historically, the ethnic Chinese in Singapore were sojourners. Most wanted to make money in the island and then return to their hometowns in Mainland China. But over a century, many established roots and raised families in Singapore. However, many Overseas Chinese were emotionally tied to China and supported the Chinese Mainland when Imperial Japan invaded China. During the Cold War, mass interaction between China and Singapore was very limited due to Maoist economic autarchy, the chaos of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, a lack of official bilateral diplomatic relations, and travel restrictions to a Maoist China that supported communist armed insurgency in Malaya. By the time travel restrictions were lifted and official diplomatic relations were established, Singaporean Chinese had adopted a multicultural national identity loyal to Singapore and not to China.

Since its independence, the Singapore state and PAP regime have sought to create a national identity and loyalty distinct from China by celebrating its multiculturalism and multi-ethnicity through its agents of mass socialization such as kindergartens and schools, television and radio, government-influenced newspapers, and national day parades. The state emphasizes English as the lingua franca for all Singaporeans, though Chinese, Malay and Tamil are official languages too. Education in school is bilingual: English and mother tongue. The PAP government engaged in social engineering by phasing out all Chinese-medium schools and transforming all local schools into bilingual ones.

This had a great impact on Singapore’s national identity and political culture, and indirectly influenced its relations with China. With generation change, the young who are educated in bilingual schools do not have a cultural and linguistic identity emotionally tied to Mainland China; instead, they possess the linguistic ability to access the English-speaking worldFootnote14 Today, Singaporeans have the best English speaking ability in Asia.

But there are two trends which may “resinicize” Singaporeans in the long run. Since the 1990s, the PAP government has accepted huge numbers of foreign migrants, especially from China. The economic rise of China also means that many more Singaporeans are now working in China, and are also nudging their children to be proficient in Mandarin for future job opportunities. It is unclear whether these two trends will dent Singapore’s multicultural identity in the long run.

Though the Singaporean identity appears to be strong after more than half a century of nation-building, the city-state’s foreign policy establishment elite is very concerned about China’s attitude toward the “Chineseness” of Singapore. Ambassador Tommy Koh opined that many Mainland Chinese believe Singaporean Chinese should be more sympathetic to Beijing’s core interests since the latter have Chinese ancestors and share commonality of language and cultureFootnote15 Indeed, Singapore state and society are very sensitive about China’s attempts to influence public opinion in the city-state toward international affairsFootnote16 However, Beijing has responded robustly by saying that it is not wrong for countries to engage in public diplomacy. (Channel News Asia, July 12 2018).

In August 2017, the notorious Huang Jing incident caused a stir in Singapore. The Singapore government expelled Huang Jing, a professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in the National University of Singapore, for being an alleged “agent of influence” for China (Beijing’s role was not stated publicly). Huang’s permanent ban from the city-state came at a time when Sino-Singapore relations were tense over the disputed South China Sea. Unlike Beijing, the city-state is not a claimant state. But Singapore has always advocated the rule of international law and freedom of navigation much to the annoyance of the Chinese giant.

A month earlier, there was an uncharacteristic public split in Singapore’s foreign policy establishment between Kishore Mahbubani and Bilahari Kausikan, two former permanent secretaries of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, over the country’s appropriate foreign policy toward a rising China. According to Mahbubani, Singapore must learn from Qatar, a small state which behaved like a middle power in the Middle East, and was duly put in its place by its irate and bigger neighbors. Simply put, Singapore, as a small state, should be prudent and not criticize China, a big and powerful country, over the disputed South China Sea.

Mahbubani wrote: “Mr Lee Kuan Yew never acted as a leader of a small state. He would comment openly and liberally on great powers, including America and Russia, China and India. However, he had earned the right to do so because the great powers treated him with great respect as a global statesman. We are now in the post-Lee Kuan Yew era. Sadly, we will probably never again have another globally respected statesman like Mr Lee. As a result, we should change our behavior significantly.” (Italics mine)Footnote17

Mahbubani continued: “What’s the first thing we should do? Exercise discretion. We should be very restrained in commenting on matters involving great powers. Hence, it would have been wiser to be more circumspect on the judgment of an international tribunal on the arbitration which the Philippines instituted against China concerning the South China Sea dispute, especially since the Philippines, which was involved in the case, did not want to press it.”Footnote18

Bilahari Kausikan critiqued Mahbubani’s thinking as “muddled, mendacious and indeed dangerous.”Footnote19 Bilahari opined that although Lee Kuan Yew and Singapore’s pioneer leaders were not reckless, they did not hesitate to stand up for their ideals and principles. He reiterated: “Singapore did not survive and prosper by being anybody’s tame poodle.”Footnote20

Though Singapore is not a liberal democracy, its government cannot be totally oblivious to the sentiments of the elites and masses toward China. Indeed, the city-state’s foreign policy establishment is sensitive about China’s alleged attempts to influence public and elite opinion. According to various surveys as tabulated in , mass public opinion is more positive toward China than elite opinion. Presumably, the masses are more positive about Chinese culture and economic achievements, and rather less concerned about the Chinese contest for “geopolitical hegemony” in East Asia or its nine-dashed line claims in the disputed South China Sea. Singaporean elite opinion toward China is generally skeptical and lacking in trust (). Interestingly, the greatest trust shown by Singapore and ASEAN elites is toward Japan, and not China and the US.

Figure 2. Singapore and other ASEAN states: positive perception of China’s influence on their country.

Figure 3. Elite Perception of Trust – Singapore and ASEAN toward China.

Question: How confident are you that China will “do the right thing” in contributing to global peace, security, prosperity and governance?

6 Conclusion: future bilateral ties – - less special, more awkward?

As the US and China engage in a “trade war,” the collateral damage includes a slowdown in trade-dependent Singapore’s GDP. If tension between Washington and Beijing were to intensify, it will place Singapore in a very difficult position. It can be anticipated that its so-called “special relationship” with China will become more awkward. While Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has affirmed Singapore would not take sides in this great power competition, the hard truth is that small states are often pressured by great powers to do so. (South China Morning Post, August 18 2019).

Singapore must assiduously cultivate good relations with all great powers, middle powers and its immediate neighbors. Arguably, the best approach will be safety in numbers. This may be done by promoting ASEAN cohesion and its envisaged political, cultural and socio-economic community, and instilling a sense of ASEAN-centric multilateralism in East Asia. Additionally, Singapore must pursue good ties with Japan, India, South Korea and Australia among others to maintain a regional balance of power. While nurturing a “special relationship” with China may appeal to some Singaporeans, a salutary analogy will be Icarus – one should not fly too close to the sun if one wants to survive in a turbulent world.

How do the four factors (adopted by this special feature’s methodology) impact on Singapore’s relations with China? Unless the PAP’s perennial one-party dominance were to end or severely eroded, domestic politics and public opinion carry little weight in the formulation of the city-state’s foreign policy toward China. Economic cooperation is at the heart of their bilateral relations. But it will be naïve to think that tiny Singapore has economic leverage over a rising giant. However, it is simplistic to assume that Beijing can easily pressure the affluent, deep pocketed and independent city-state to do its biding by wielding an economic “carrot and stick.” Geopolitics is more unpredictable in their bilateral relations. In a world where the US remains a superpower, Singapore can nimbly pursue a winning strategy of geopolitically aligning with Washington while nurturing closer economic ties with China. But Singapore will be in an insidious place if Pax Americana is replaced by Pax Sinica in East Asia.

What about the four-factor analysis in Beijing’s ties with Singapore? In post-Maoist China, revolutionary ideology has become irrelevant to bilateral ties. Insofar as China is helmed by a communist party, its public opinion and domestic politics are not important drivers in its foreign policy toward Singapore. While the latter’s economic contribution to Chinese modernization and growth may become relatively less important in the long run, it remains manifestly useful to the Mainland. It is not inconceivable that geopolitics in the long run may shake Sino-Singapore relations when US-China competition for regional hegemony in East Asia were to intensify.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

LAM Peng Er

Lam Peng Er obtained his PhD from Columbia University. He is the editor of three academic journals:International Relations of the Asia-Pacific (Oxford University Press), Asian Journal of Peacebuilding (Seoul University) and East Asian Policy: An International Quarterly (East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore).

Notes

1 See, for example, Ortmann and Thompson, “China and the ‘Singapore Model’,” 39–48; Ortmann and Thompson, “Introduction: The ‘Singapore Model’ and China’s Neo-Authoritarian Dream,” 930–945.

2 For instances on the Sino-Singapore special relationship, see Zheng and Lim, “Lee Kuan Yew: The Special Relationship with China,” 31–48; Wong and Chong, “The Political Economy of Singapore’s Unique Relations with China,” 31–61; Wong and Song, “China’s Special Relationship with Singapore,” 245–250.

The Singapore-China special relationship was defined by a Singapore journalist in a Business Times (November 6 2015) article thus: “The special relationship that Singapore and China enjoy is the result of trust built over the years between leaders and citizens alike. Though vastly different in size and schema, Singapore and China have established a special friendship since the mid-1970s which has evolved over time, in line with changing needs and development priorities”.

3 Foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang had this to say on its stance toward Singapore’s military exercises in Taiwan: “The Chinese side is firmly opposed to any forms of official interaction between Taiwan and countries that have diplomatic relations with us, military exchanges and cooperation included. We require the Singaporean government to stick to the one China principle.” See Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Slovenia, “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Geng Shuang’s regular press conference on November 282,016”.

4 See, for example, Tan, “Faced with the Dragon,” 245–265.

5 Former Singapore Foreign Minister George Yeo explains: “Singapore can never afford to have other countries in ASEAN see us as a Chinese state in Southeast Asia. Lee Kuan Yew made it a matter of principle that Singapore would establish diplomatic relations with China only after our neighbors had done so”. See George Yeo, “Reflections by George Yeo: Celebrating 30 years of diplomatic relations between Singapore and China”, Think China, October 282,020.

6 Yew, “The Evolution of Contemporary China Studies in Singapore,” 135–158.

7 Quoted in Joshua Kurlantzick, “The Belligerents: Meet the Hardliners Who Now Run China’s Foreign Policy.”

8 For a comprehensive study on Sino-Singapore economic relations, see Saw and Wong, eds., Advancing Singapore-China economic Relations.

9 Harper, “Singapore becomes hub for Chinese tech mid US tensions.”

10 See Suryadinata, The Rise of China and the Chinese Overseas.

11 The Singapore media reported: “Following the back-and-forth between Singapore and Chinese state-owned newspaper Global Times over the South China Sea issue, some Singapore businessmen with interests in China are being questioned by their Chinese counterparts, on where they stand on the matter. Singapore companies … are concerned that this, along with the increasingly shrill comments by Chinese netizens in response to the newspaper’s provocative articles, would eventually affect their businesses. … Ho Meng Kit, chief executive officer of Singapore Business Federation, added: ‘If this drags on, and there’s widespread anger or hostility toward Singapore products, we’ll be concerned. The Chinese are very nationalistic’”. See Tan, “Singapore businesses quizzed by Chinese counterparts over their stand on South China Sea.”

12 Though Goh Chok Tong was Prime Minister of Singapore from November 1990 to August 2004, Singapore’s foreign policy toward China during that period was marked by continuity. One reason is because Lee Kuan Yew remained highly influential in the Cabinet and was the “grandmaster” in the city-state’s external relations.

13 Lam, “The Politics of Confucianism and Asian Values in Singapore.”

14 See, for example, Sin and Ng, “The Chinese Singaporean identity.” This article noted: “While China’s soft-power charm offensive has caused some Singaporeans to hope for closer bilateral ties between the two countries, others, amid a growing sense of national identity, feel that relations should be kept as those between friendly states but without the common ethnic element coming into the picture”.

15 See, for example, Koh, “China’s perception of Singapore: 4 areas of misunderstanding.”

16 See, for example, Yong, “Singaporeans should be aware of China’s ‘influence operations’ to manipulate them, says retired diplomat Bilahari”; Qin, “Worries Grow in Singapore Over China’s Calls to Help ‘Motherland’,”.

17 Mahbubani, “Qatar: Big lessons from a small country.”

18 Ibid.

19 Nur and Chew, “Minister Shanmugam, diplomats Bilahari and Ong Keng Yong say Prof Mahbubani’s view on Singapore’s foreign policy ‘flawed’.”

20 Ibid.

Bibliography

- Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Slovenia. “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Geng Shuang’s Regular Press Conference on November 28, 2016.” Posted online on 28 November 2016. http://si.chineseembassy.org/eng/fyrth/t1419412.htm. Accessed 14 September 2019.

- Harper, J. 2020. “Singapore Becomes Hub for Chinese Tech Mid US Tensions.” BBC News, September 16. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-54172703. Accessed 11 January 2021.

- Hu Fu Center for East Asia Democratic Studies, National Taiwan University. “Asian Barometer – Surveys.” n.d. http://www.asianbarometer.org/survey. Accessed 14 September 2019.

- Koh, T. 2016. “China’s Perception of Singapore: 4 Areas of Misunderstanding.” Straits Times, October 21. https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/chinas-perception-of-singapore-4-areas-of-misunderstanding. Accessed 14 September 2019.

- Kurlantzick, J. 2011. “The Belligerents: Meet the Hardliners Who Now Run China’s Foreign Policy.” New Republic, January 27. https://newrepublic.com/article/82211/china-foreign-policy. Accessed 14 September 2019.

- Lam, P. E. “The Politics of Confucianism and Asian Values in Singapore.” In Confucian Culture and Democracy, edited by J. F.-S. Hsieh, 111–130. Singapore: World Scientific Press, 2014.

- Mahbubani, K. 2017. “Qatar: Big Lessons from a Small Country.” Straits Times, July 1. https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/qatar-big-lessons-from-a-small-country. Accessed 14 September 2019.

- Nur, A. M. S., and H. M. Chew 2017. “Minister Shanmugam, Diplomats Bilahari and Ong Keng Yong Say Prof Mahbubani’s View on Singapore’s Foreign Policy ‘Flawed.’” Straits Times, July 2. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/prof-kishore-mahbubanis-view-on-singapores-foreign-policy-deeply-flawed-ambassador-at. Accessed 14 September 2019.

- Ortmann, S., and M. R. Thompson. “China and the ‘Singapore Model.’” Journal of Democracy 27, no. 1, January (2016): 39–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0004.

- Ortmann, S., and M. R. Thompson. “Introduction: The ‘Singapore Model’ and China’s Neo-Authoritarian Dream.” China Quarterly 236, no. December (2018): 930–945. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741018000474.

- Qin, A.2018.Worries Grow in Singapore over China’s Calls to Help ‘Motherland’ New York Times. August.5.https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/05/world/asia/singapore-china.html Accessed 14 September 2019.

- Saw, S.-H., and J. Wong, eds. Advancing Singapore-China Economic Relations. Singapore: EAI & Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2014.

- Seah, S., T. H. Hoang, M. Martinus, and P. T. P. Thao The State of Southeast Asia: 2021 Survey Report. Singapore: ASEAN Studies Centre and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2021. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/The-State-of-SEA-2021-v2.pdf. Accessed 9 June 2021.

- Sin, Y., and W. M. Ng 2018. “The Chinese Singaporean Identity: A Complex Ever Changing Relationship.” Straits Times, February 14. https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/a-complex-ever-changing-relationship. Accessed 11 January 2021.

- Suryadinata, L. The Rise of China and the Chinese Overseas: A Study of Beijing’s Changing Policy in Southeast Asia and Beyond. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2017.

- Tan, S. S. “Faced with the Dragon: Perils and Prospects in Singapore’s Ambivalent Relationship with China.” Chinese Journal of International Politics 5, no. 3 (2012): 245–265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/pos012. Autumn.

- Tan, W. “Singapore Businesses Quizzed by Chinese Counterparts over Their Stand on South China Sea.” Today, October 9 (2016). Accessed 11 January 2021. https://www.todayonline.com/business/spore-businesses-quizzed-chinese-counterparts-over-their-stand-south-china-sea-issue.

- Wang, G., and J. Wong, eds. Interpreting China’s Development. Singapore: World Scientific Press, 2007.

- Wong, J., and C. Chong. “The Political Economy of Singapore’s Unique Relations with China.” In Advancing Singapore-China Economic Relations, edited by S.-H. Saw and J. Wong, 31–61. Singapore: EAI and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2014.

- Wong, J., and S. S. Teng. “China’s Special Relationship with Singapore.” In Interpreting China’s Development, edited by G. Wang and J. Wong, 245–250. Singapore: World Scientific Press, 2007.

- Yeo, G. “Reflections by George Yeo: Celebrating 30 Years of Diplomatic Relations between Singapore and China.” In Think China, 28. 2020.

- Yew, C. P. “The Evolution of Contemporary China Studies in Singapore: From the Regional Cold War to the Present.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 22, no. 1 (march2017): 135–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-016-9416-0.

- Yong, C. 2018. “Singaporeans Should Be Aware of China’s ‘Influence Operations’ to Manipulate Them, Says Retired Diplomat Bilahari.” Straits Times, June 27. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/singaporeans-should-be-aware-of-chinas-influence-operations-to-manipulate-them-says. Accessed 14 September 2019.

- Zheng, Y., and W. X. Lim. “Lee Kuan Yew: The Special Relationship with China.” In Singapore-China Relations: 50 Years, edited by Y. Zheng and L. F. Lye, 31–48. Singapore: World Scientific Press, 2015.

- Zheng, Y., and L. F. Lye, eds. Singapore-China Relations: 50 Years. Singapore: World Scientific Press, 2015.