ABSTRACT

China and Indonesia have undergone extreme changes throughout their relationship in the modern era. While China’s rise created both opportunities and challenges, Indonesian decision makers have experienced constant pressures from domestic and international influences when dealing with China. This article examines Indonesian-Chinese relations in the last two decades through four factors: perception, domestic politics, economic engagements, and the international environment, based on data from official documents, news, journal articles, and direct observation. This framework portrays significant development of the two countries’ partnership but not without problems. Internal factors (e.g., perceptions of elites, domestic politics) have become increasingly relevant in determining bilateral relations while international pressures filtered. China has provided many opportunities over the years, but economic and strategic relations seem to have relied more on Indonesia’s favorable domestic factors than regional and global developments. In particular, the ethnic Chinese in Indonesia variously promoted and hindered the relations. Chinese cultural diplomacy also expanded and involved a wide range of actors beyond government officials to influence Indonesian domestic factors by moderating negative sentiments about China and the Chinese. This study contributes to understanding on Indonesia’s foreign policy in the last two decades and China’s relations with its neighbors.

1. Introduction

Relations between Indonesia and China date back to centuries ago. Before becoming modern nation states after the Second World War, the two countries engaged with each other through expeditions and migrations both prior to and during the European colonialization period. As such, interactions between indigenous peoples in areas that have now become parts of Indonesia and Chinese immigrants prior to the establishment of modern nation-states still seem to shape contemporary relations.

The Chinese community has become a significant part of Indonesian society since the nation gained independence in 1945. These individuals have largely assimilated with local Indonesian peoples, but some have remained in exclusive communities, while others have even sought renewed engagements with China. Despite having experienced political discrimination, they have generally maintained a very strong role in Indonesian economy. In 2010, the Census of the Indonesian Statistical Bureau indicated that Indonesian Chinese descendants accounted for 1.2% of the total population of approximately 238.7 million personsFootnote1 These Chinese descendants in Indonesia have played very important roles in the relations between Indonesia and China. For many Indonesians, however, the term Chinese still refers to both foreigners and Chinese Indonesians.

In the modern era, Indonesia and China have undergone dynamic relations, ranging from being close alliances (1955 to 1966) to conflict (1967 to 1990) and a growing partnership (1990–2000). Under President Sukarno, especially from the middle of the 1950s to the middle of the 1960s, Indonesia established a very close partnership with the People’s Republic of China (PRC, or China). The Jakarta-Peking axis was developed upon Sukarno’s anti-capitalist and anti-Western campaigns, triggered by the United States’ interference in Indonesian domestic politics. During this period, Indonesia had striven to maintain its independent, non-block position but was pushed back to the socialist countries’ camp.

Under President Suharto, Indonesia officially froze bilateral relations with China on October 30, 1967 after accusing the PRC of being a threat to Indonesia due to its support of the Indonesian Communist Party. For more than three decades, Suharto’s military regime prohibited any dealing with the PRC and cut off almost all contact with China. During this period, the Suharto government scrutinized the Chinese community so harshly that many of them fled back to China or other countries, while others simply abided a wide range of discrimination ranging from the prevention of cultural practices and the restriction of the Chinese language and characters in printed materials to selective university and civil service processes. Nevertheless, the Chinese community was allowed to maintain their economic activities; in many cases, they even maintained strong business links with the militaryFootnote2 and political elites, including Suharto’s familyFootnote3

The end of the Cold War and the rise of China as an economic power since the early 1990s catalyzed further developments in Indonesia-China relations. China’s Open-Door Policy was perceived as opportunities and seemed to motivate the Chinese-Indonesian business community to encourage improving relations between China and Indonesia. Along with other stake holders, this group successfully convinced SuhartoFootnote4 In China, isolation from Western countries after the Tiananmen incident seems to have driven its elites to approach the surrounding countries in Southeast Asia. Politically and economically, Indonesia was important due to its strategic location, market size, and existing networks of economically dominant Chinese descendants. On August 8 1990, Indonesia and China officially normalized their diplomatic relations despite concerns among the Indonesian military.

At the end of 1990s, three important events affected Indonesia-China relations. The first was economic deprivation in Indonesia resulting from the Asian financial crisis. The second was the collapse of the Indonesian financial system which resulted in a series of events: in May 1998, political and social riots occurred in Jakarta and other big cities. Anti-Chinese rampages spread and culminated during this period of social turbulenceFootnote5 The third event was Suharto’s resignation on May 21, 1998, which was the beginning of Indonesia’s political transformation into a democratic country. This period marks the democratization of Indonesia’s foreign policy, in the sense that more stake holders were involved in the country’s external relations, including those with China. Economic relations between the two countries drastically increased after the fall of the Suharto Regime.

Existing literature varies quite greatly in explaining factors shaping Indonesia’s relations with China. Global strategic environment, in which the rising China had challenged the US’s domination in the region since the end of the Second World War, affected Indonesia’s foreign policy greatlyFootnote6 In addition, the Chinese’s economic power was identified as an important factor to push growing economic engagements between the two countriesFootnote7 Moreover, some studies highlight Indonesian domestic politicsFootnote8 or the roleFootnote9 of Chinese Indonesians in analyzing the two countries’ relations. Furthermore, a great number of studies focus on individual and group levels on how perceptions matter in the bilateral relationsFootnote10 Nevertheless, a more comprehensive study that combines those influential factors is limited.

This article examines the relations between Indonesia and China by applying a four factors model, namely perception, domestic politics, economic engagements, and the international environment (i.e., both regional and global dynamics)Footnote11 to provide a more comprehensive analysis. The study focuses on the first two decades of the 21st century with some considerations on indispensable legacies of previous periods inherited from Sukarno’s and particularly Suharto’s presidencies. The analysis evolves in three sections. The next two sections focus on the roles of the four factors in shaping Indonesia-China bilateral relations in the first and the second decades of the 21st century respectively, while the final section highlights related trends.

2. Indonesia-China relations in the first decade of the 21st century

This period began with social and political instability in Indonesia. The country suffered a devastating financial crisis that left many people impoverished, with no money or jobs. Amid this unrest, Indonesia underwent very difficult social, political, and economic transformations. However, the transformation era resulted in some positive factors that helped drive Indonesia-China relations more robustly. Thus, the role of domestic politics was very significant. On the other hand, the impacts of the international and regional environments were not to be underestimated.

In their own respective ways, two presidents set important legacies toward a democratic political transition, which in turn strongly impacted Indonesia-China relations. First, President Abdurrahman Wahid accelerated the democratic transition and abolished a great number of limitations and discriminations that had been placed on minority groups (including Chinese Indonesians) during Suharto’s government. In order to build a multicultural society in Indonesia, Wahid championed political, social, and cultural freedoms for the Chinese minority, thus allowing them to revive Chinese newspapers, radio programs, and television feeds while practicing their own cultural traditions and setting the Chinese New Year as a public holiday. Regarding foreign affairs, he strengthened Indonesia-China relations by visiting China in December 1999. He was the first Indonesian top leader to do so after President Sukarno in 1956. Thus, the Wahid presidency significantly contributed to repositioning Chinese minorities in Indonesia and developing Indonesia-China relations.

The second legacy was President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s campaign for military transformation. As one of the key military and political figures in the post-Suharto era, General Yudhoyono promoted reform throughout the Indonesian military. The transformation was designed to reposition the military in Indonesian politics and develop more ideal civil-military relations in national governance. The military reformation, along with dynamics of the international environment during the early 2000s, seemed to affect not only Indonesian military’s political position but also their perception about what posed threats to the country. The transformation also reshaped some perceptions about China. Yudhoyono was the first president directly elected by the Indonesian people. As such, he enjoyed very high legitimacy. This strong political position enabled Yudhoyono to assert his personal values and ambitions in the context of foreign policiesFootnote12, including Indonesian relations with China.

Several global and regional events occurred during this period, many of which significantly affected Indonesian-Chinese relations. First of these events was China’s responses to Indonesia when the country went through difficult times. In 1999, due to the violent process of Timor Leste’s separation from Indonesia, Indonesia received worldwide condemnation and its military was accused of human rights violations. Consequently, the US and many Western European countries sanctioned the Indonesian military by suspending security cooperation and military purchases. This was another blow to Indonesian diplomacy that came only a couple of years after the financial crisis and anti-China riots in May 1998. China’s responses to the difficult Indonesian international position seemed to appease the Indonesian elites. Unlike Taiwan, the Chinese Government limited its criticism of the anti-Chinese riots in 1998 and did not join Western nations in condemning Indonesia or sanctioning its military for poorly handling the post-referendum violence in Timor Leste.

Second, China played an important role in establishing the Chiang Mai Initiative (CMI) in 2000, which supported liquidity among Asian countries. The CMI was a bilateral (then multilateral) swap agreement created by ASEAN Plus Three (APT) countries to strengthen financial credibility among East Asian countries, prevent financial crises, and protect member countries from the hostage-status experienced by some when dealing with the IMF and World Bank during the Asian financial crisis. Despite its nature of economic cooperation, the CMI created political confidence among East Asian countries regarding many neighboring countries, particularly China and Japan as they were the two biggest contributors to the CMI system. Further, the CMI aided a growth of regional awareness among Asian countriesFootnote13 China’s indispensable participation in establishing the CMI seems to be in line with the country’s effort to enhance its economic leverage and expand its political role in the regionFootnote14 Battered Asian countries were likely to find refuge in their regional fellows after difficult times dealing with harsh structural adjustments demanded by the financial institutions dominated by Western countries.

Third, China cooperated with the association of the Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to manage conflicts resulting from overlapped claims in the South China Sea between itself, Taiwan, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Brunei by signing the Declaration of Conducts in the South China Sea (DOC) with ASEAN in 2002. The problems arose during the 1980s when China claimed an area defined by the nine-dash line (the coordinates of which were never stated), thus resulting in several incidents between itself and other claimant states. As the South China Sea had become a world hotspot and the areas of conflict were adjacent to its territorial waters, Indonesia initiated regional workshops beginning in 1990 to prevent deteriorating circumstances. Indonesia and other ASEAN countries were so concerned about China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea that they pursued Chinese commitments through a regional rather than bilateral platform. Thus, China’s approval of the DOC mitigated the notion that it intended to mistreat ASEAN countries and showed a willingness to behave peacefully, as proclaimed by President Hu Jintao. Subsequently, ASEAN countries encouraged China to negotiate a binding Code of Conduct (COC) on the Sea.

Fourth, China was the first dialogue partner that also became an ASEAN Strategic Partner in 2003. In the same year, China acceded to the ASEAN Treaty of Amity and Cooperation (TAC), which stipulated ASEAN principles and code of conduct in dealing with each other. China was the first ASEAN partner country to accede to the TAC, thus indicating its willingness to be bound by ASEAN norms, which were frequently criticized by European and other countries, mainly due to the principle of noninterference. Fifth, in the same year, the China-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) was signed. Again, China was the first country with an FTA with ASEAN. Together, these events created a conducive climate for a better Indonesia-China relationship.

The Indonesian perception of China was somewhat diverse. The domestic politics, China’s amazing economic growth, and the country’s attitude toward ASEAN and Indonesia (especially if compared to the way the US and other Western countries treated Indonesia in the early 2000s) appeared to affect how Indonesian elites perceived China. Gradually, the Chinese model of economic development attracted their attention, resulting in more positive perceptions about China. Perhaps these developments were also driven by soft power and a public policy strategy that China applied in its approach to neighboring Southeast Asian countries during the early 2000s. As such, an increasing number of Indonesian people seemed to perceive China as a growing power and thus welcomed it as an alternative to partnerships with American and European collaborators. Nevertheless, changing perceptions among the Indonesian military to China occurred more conservatively. Their positive tone to China seemed driven more by Western isolationism and sanctions rather than admiration, especially because they paid serious attention to China’s threat to the South China Sea and Indonesian territory. An influx of Chinese goods into Indonesia after CAFTA also appeared to create resentment among local businesses, who were unable to compete with Chinese products. These issues created a diversity of perceptions about China in Indonesia depending on interests, experiences, and knowledgeFootnote15

Economic relations between Indonesia and China grew deeper and wider at this time. CAFTA in 2003 and establishment of the Indonesia-China Strategic Partnership in 2005 further facilitated economic relations. shows specific numbers related to how the two frameworks boosted trade relations between Indonesia and China. Both Indonesian imports from and exports to China grew so consistently that the total trade amount in 2008 was almost eight times that of 1999 (from USD 3,251 USD million to USD 26,885 USD million) before slightly decreasing in 2009 due to the global financial crisis. However, Indonesian imports from China rose so drastically from 2007 to 2008 that it suffered a trade deficit with China amounting to as much as USD 3,612.7 USD million.

Table 1. Trade relations between Indonesia and China from 2001 to 2010

Another interesting development was related to the investment values between Indonesia and China. This horizontal development in economic relations was marked by fluctuating values. Even until the 2000s, Indonesia invested more into China than China did into Indonesia due to the capital flight of Chinese-Indonesian conglomerates into the hometowns of their ancestors in Guangzhou and Fujian. One year after CAFTA was signed in 2003, Chinese investments started coming into Indonesia (See below). However, the Chinese FDI to Indonesia was considered very small when compared to other sources of FDI for Indonesia. From 2001 to 2010, the realization of China’s investment in Indonesia was merely US$ 477.6 millionFootnote16

Table 2. Investment relations between Indonesia and China from 2001 to 2010

Security relations between Indonesia and China developed well during this period despite several challenges. In responding to global challenges, President Wahid once suggested an alliance between Indonesia, China, and IndiaFootnote17 Under President Yudhoyono, Indonesian-Chinese political and security relations expanded robustly. Yudhoyono was perceived as closely linked to the United States; however, as President, he exercised a hedging strategy toward US and Chinese competitive relations (Fitriani 2015). President Yudhoyono and President Hu Jintao signed the Joint Declaration on the Strategic Partnership between the Republic of Indonesia and the People’s Republic of China when the latter visited Indonesia in April 2005 to attend the 50th anniversary commemoration events of the 1955 Bandung Conference. Only one month later, the two countries signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on defense technology cooperation to facilitate joint efforts in the military industry. They also discussed military procurements, including jet fighters from China to Indonesia. The annual Indonesia-China Defense Security Consultation Talk began in 2006, whereas maritime cooperation did not begin until 2007. In 2008, the two countries strengthened their cooperation through joint development of the defense industry, exchange and training of military officers, and joint military exercisesFootnote18

Despite his military background and American education, Yudhoyono opted to enhance the country’s security relations with the former adversary state of China. Thereafter, perceptions about China changed dramatically, shifting from that of a conflicting nation to a security partner, not only regarding security problems but also in relation to supplying military equipment. This dramatic change among Indonesian military elites reflected a rational choice and their frustration with sanctions from the US and other Western nations.

In addition, from robust developments in economic and security relations, Indonesia and China strengthened their relations in social and cultural aspects, including their cooperation in education and technology. Academic cooperation between and among leading universities from the two countries emerged either through bilateral channels or the ASEAN University Network. The Chinese Government began providing scholarships for Indonesian students and scholars, mainly to study the Chinese language. As in other countries, the Chinese Government also promoted cultural exchanges with Indonesia through the establishment of the Confucius Institute in 2004. Nevertheless, some large universities took prudent steps in welcoming academic cooperation; some rejected the Institute.

Relations among non-state actors also slowly developed. The Chinese Government sponsored the establishment of the Network of East Asian Think-tanks (NEAT) as track two of the ASEAN Plus Three (APT) in 2003 and the Network of ASEAN-China Think-tanks (NACT) as track two of the ASEAN Plus China framework. Indonesian and Chinese think-tanks and scholars seemed to interact in those networks during that time.

The network platforms and relations in sociocultural and academic aspects expanded through actors working on bilateral issues, yet political interests embedded in those forums and through those actors were not to be overlooked. China began to undertake a soft power approach through cultural diplomacy. The success in hosting the Beijing Olympics in 2008 also seemed to boost China’s confidence in claiming itself as a major country.

Several challenges to Indonesia-China bilateral relations can also be identified during this period. The first involved a growing trade deficit on the Indonesian side. The deficit indicated Indonesia’s low terms of trade vis-à-vis China and the country’s inability either to compete with Chinese products or penetrate the Chinese market. The second involved general relations between the two countries, which were mainly confined to political leaders, diplomats, and Chinese Indonesians. During this period, bilateral relations rarely reached out to the common people or most Indonesians. The third challenge was rooted in frequent public criticism from Indonesian politicians and scholars regarding the trade deficit and influx of Chinese products in the Indonesian domestic market. This issue could have easily resulted in anti-China sentiments for either political or economic purposes. The fourth was China’s assertive behavior in the South China Sea, which not only threatened ASEAN unity and centrality (an important matter for Indonesia) but also created a dangerous hotspot right at the northern Indonesian border.

Nevertheless, despite those challenges, Indonesia and China managed to enhance their bilateral relations into a strategic partnership in 2005 and expanded the cooperation to defense affairs. One factor on the Indonesian side of the progress in the bilateral relations was the change in domestic politics to include more stake holders in foreign policy decision making, which brought in better perceptions of China than those in President Suharto’s period. These domestic developments in Indonesia were matched with new geopolitics and geoeconomics in East Asia, in which China rose as “a peaceful and friendly regional hegemon.” President Hu Jintao’s “Good Neighborhood Policy” to Southeast Asian countries had created a strong appeal for Indonesia, especially because the country was condemned by the US and European countries after the Timor Leste incidents. The condemnations included Western countries’ sanction on the Indonesian military, which forced Indonesia to search for alternative security partners and suppliers; a timely opportunity for China to step in. The development of Indonesia-China strategic and security relations was supported by the positive political atmosphere between the two governments and growing economic relations since the 1990s, too. The four factors, namely domestic politics, elite perceptions, economic relations and geopolitics, seem to work harmoniously to improve Indonesia-China relations in this period.

3. Indonesia-China relations in the second decade of the 21st century

Founded by positive experiences in the first decade of the 21st century and allowed by conducive domestic politics, the bilateral relations between Indonesia and China grew and expanded. However, perceptions about China and the Chinese in Indonesia fluctuated greatly in this decade. The democratic transformation era opened public spaces for more diverse actors, resulting in a wide range of perceptions about China and the Chinese. Rather than being dominated by the government’s perception of China (just as in Suharto’s period), in this democratic era, more voices influenced Indonesia’s policy to China. Naturally, negative sentiments frequently reemerged due to Suharto’s legacy, Chinese aggressiveness in the South China Sea (including Indonesian territory of the Natuna Sea), the influx of Chinese (cheap and poor quality) products, and narrations on “sudden inflow of Chinese workers to Indonesia.”

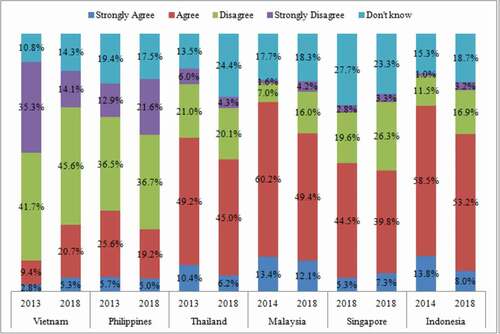

Perceptions of young Indonesians toward China in the last several years is interesting and important to note. A time-series study by SonodaFootnote19 revealed that in 2018, fewer students believed that China’s rise was peaceful when compared to those in 2014 (). Sonoda’s survey was in line with the ISEAS’ Survey 2021 that reveals 48.7% of Indonesian respondents distrust China because they perceived Chinese economic and military power could be used to threaten Indonesian interest and sovereigntyFootnote20 This was likely the result of negative sentiments against China after several incidents in Natuna as well as anti-China sentiments aroused by Indonesian politicians to support their political interests in the 2017 Jakarta Gubernatorial and 2019 Presidential elections. Those events were widely reported in the media. The latest development of China’s presence in Southeast Asia has also been a concern for some Indonesians who were worried about China’s growing political and strategic influenceFootnote21

Figure 1. The opinion of ASEAN countries’ university students on the question if China maintains peaceful relations with Asian countries despite international prominence.

Nevertheless, reveals that young Indonesian perceptions of China were generally more positive than those from other countries in Southeast Asia. This is perhaps due to several reasons. The first was the rapid development of political relations between the two states, including positive statements from political leaders of both countries during their respective visits. The second reason was intensive media coverage about recent Chinese development, China’s economic progress and modern development amid economic difficulties in some parts of the world. This included China’s diplomacy in international and regional forums and its success in international competitions (including sports and space technology). The third reason was the effective strategy and active cultural diplomacy undertaken by the China government either through the media and exchanges of people. The cultural diplomacy was undertaken to counter negative images and both anti-China and anti-Chinese sentiments in Indonesia. This reflects the Chinese strategy to enhance political, economic, and strategic relations between the two countries. Chinese diplomacy to Southeast Asian countries during the pandemic of COVID-19 was also appreciated by Indonesians who perceived China as the most helpful country in comparison with other ASEAN dialogue partnersFootnote22

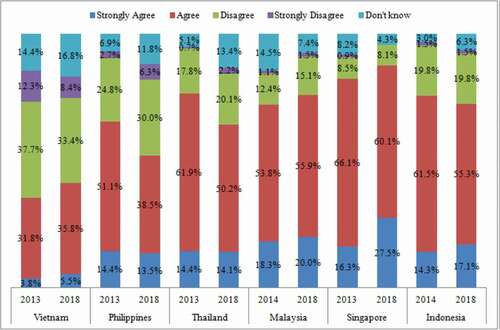

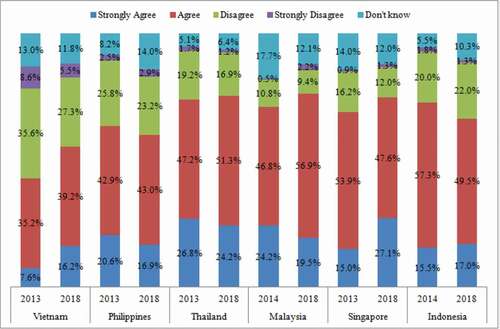

Sonoda’s study also revealed that, in addition to having relatively positive perceptions of China, elite students in Indonesia (as in other ASEAN countries, excluding Vietnam) also appreciated the opportunity offered by China’s rise. shows that China’s rise was perceived as an opportunity by most of the respondents in 2014 and 2018. They also had positive images of China as a new global power and tended to believe that China would surpass the dominant influence of the US in Asia (). These findings may result from the negative images of American hegemony and global policies in Indonesia.

Figure 2. The opinion of ASEAN countries’ university students on the question if the rise of China offers many opportunities.

Figure 3. The opinion of ASEAN countries’ university on the question if China will supersede the US in terms of Asian influence.

The dynamic perceptions of China in Indonesia are likely shaped by the country’s democratic transition. The current Indonesian political system allowed for the emergence of new actors in public discussions and in dealing with China. The diverse perceptions of China were also facilitated by the popular use of social media and availability of online information sources that spread news more rapidly and widely. In this context, perceptions of China, which were once dominated and dictated by the government, now vary widely.

Indonesian domestic politics and dynamics have played significant roles not only in diversifying perceptions about China, but also in the country’s policies toward China. There were several characteristics in Indonesian domestic politics that seemed to shape the country’s relations with China during this period. The first was the difficult democratization process that brought the country back-and-forth along the democratic spectrum. Whereas general and local elections were undertaken regularly and peacefully in Indonesia, several practices that reflected basic problems in Indonesian democracy prevailed. These practices included hoaxes and the highlighting of sensitive issues (in a multi-racial country like Indonesia) during election campaigns. For example, several politicians and political parties aroused anti-China or anti-Chinese sentiments to defame political candidates with Chinese ancestry such as former Jakarta Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnana who was accused of blasphemy during the campaign of 2017 governor election. Others criticized the ruling government and parties for the Indonesian trade deficit and influx of Chinese migrants into Indonesia by using wrong or manipulated dataFootnote23 to construct images of government weakness vis-à-vis China.

The second was democratic consolidation that brought about the diffusion of political power as the result of the country’s political transformation. As a result, the role of the military in politics and foreign policy decreased while the role of the parliament in foreign policy increased. Civil society (e.g., academia and think-tanks, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and religious elites) and the media also began to be involved in foreign policiesFootnote24 The role of Islamic groups and Moslem leaders in politics during this period should not be underestimated.

The third was a relatively stable political system despite chaotic election campaigns. The democratic political system was not only able to reelect President Yudhoyono in 2009 for a second term in office but also able to produce a peaceful government transition in 2014 from Yudhoyono to President Joko Widodo, who was reelected in 2019. Domestic political stability seemed to give Indonesian leaders more confidence in dealing with international affairs and China while adopting a hedging strategy in handling competitive relations among major powers. President Yudhoyono was so actively involved in international affairs that he was able to bring Indonesia back to the global stage after difficulties during the financial crisis and political-social transformationFootnote25 President Widodo was able to establish harmonious relations with Chinese President Xi Jinping, which recently helped the two countries develop robust economic engagements and stable political relations.

There were also several developments in Indonesia’s external environment during this period. The most remarkable was the changing geopolitics and geo-economic environment that intensified American-Chinese competition at both the global and regional levels. After two decades of paying little attention to Southeast Asia, the US returned. Concomitantly, concerns over China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea and its military modernization encouraged Southeast Asian countries, including Indonesia, to welcome US President Barack Obama’s rebalancing strategy or pivot to the region in 2010. Under US President Donald Trump, the strategy was changed to one focusing on the Indo-Pacific.

In addition, President Xi Jinping’s policy to drive his nation to pursue “Chinese Dreams” has manifested in two ways. First, China became more aggressive and assertive in South China Sea disputes by building military facilities on artificial islands in the area and using both state and non-state actors to justify China’s historical claims to conflicted areas. Second, China launched the One Belt One Road (OBOR) or Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to develop networks between China’s partners in Asia, Africa, and South Europe, thus gaining a broader sphere of influence while taking economic opportunities through infrastructural development projects along the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road and the inland Silk Road Belt. For this ambitious project, China established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2016 and employed Chinese academics, students, and cultural groups to help promote the program.

Moreover, competition between China and Japan also added to regional dynamics in Southeast Asia. Both countries applied several strategies to enhance their influence in the region. Prior to the BRI projects, China offered ASEAN countries an upgraded CAFTA in 2014 and became more accommodating to ASEAN’s interests and needs. Japan maintained its close relations with the regional countries that had developed during the 1970s, after the “Fukuda Doctrine,” through more active diplomacy and maritime cooperation. Due to its internal and external problems, Japan had limited options to balance the Chinese influence in Southeast Asia that it needed to engage regional countries like IndonesiaFootnote26

Furthermore, ASEAN countries tried to consolidate regional integration by launching the ASEAN Community at the end of 2015; however, ASEAN centrality and solidarity were frequently questioned, especially when ASEAN Foreign Ministers failed to produce a Chairman’s Statement at the end of their regular meeting in 2012 due to disagreements among ASEAN member states about the South China Sea conflict. Indonesia tried to consolidate the ASEAN position amid big-power tensions, among others by promoting the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP), which aims to turn geostrategic competition into a wide-ranging area of cooperation that includes China.

Finally, ASEAN-China relations grew deeper and wider as the two celebrated the 15th anniversary of the ASEAN-China Strategic Partnership in 2018. Due to China’s economic prowess, all ASEAN countries seem to move closer to China. This includes the Philippines and Vietnam, which once had serious and open disputes with China in the South China Sea. All have seemed to take advantage of the rich dragon just as the US commitment has been questioned under the Trump Administration.

Hence, the Indonesian regional and global position about not isolating China is not only congruent with the country’s independent-and-active foreign policy principle, but also based on its rational and pragmatic position in maintaining strong relations with the Asian giant. It is in the best interest of Indonesia to treat China as a source of opportunities, especially in economic aspects. Chinese economic strength was indeed the main attraction, especially after 2010, when it had surpassed Japan as the second biggest economy in the world and when CAFTA became effective. In 2013, leaders of the two countries also signed The China-Indonesia Five Year Development Program for Trade and Economic Cooperation. Currently, China is the most important trading partner for Indonesia, as the country ranks number one as an export destination and import source. shows significant growth in China-Indonesia goods trading once CAFTA became effective in 2010. In 2018, bilateral trading reached USD 72,664.75 USD million, a figure 22 times larger than combined total trade in 1990, when the two countries first normalized diplomatic relationsFootnote27

Table 3. Trade Relations between Indonesia and China from 2011 to 2018

Nevertheless, there have been severe criticisms about the continued development of Indonesian-Chinese trade. The first highlights the fact that increased volumes and values have also increased deficits on the Indonesian side. This indicates the Indonesian inability to seize business opportunities in China. The import of Chinese toys and textiles rose drastically, to 952% and 215%, respectively, only four months after CAFTA became effectiveFootnote28 The second criticism is that bilateral trade remains below potential considering that Indonesia is the largest regional economy while the political climate has been favorable to economic engagements. The third criticism points out that increased bilateral economic relations have mainly involved Chinese descendants in Indonesia, reflecting the special privileges they enjoy and revealing mainland Chinese preferences for fellow Chinese while ignoring other segments of the Indonesian society. While these preferences may rest on advanced Chinese economic networks in East Asia (as well as on cultural and language familiarity), such exclusive trading relations may exacerbate economic gaps in Indonesia while fueling anti-China sentiments.

Indonesian-Chinese investment relations have also developed during this period. In previous decades, more investments moved from Indonesia to China than from China to Indonesia. China was not considered an important investment source for Indonesia during the early 2010s. In 2014, investment relations between the two countries remained small; direct investments from China did not account for more than 1% of China’s total outbound FDIFootnote29 Acknowledging this problem, the governments of both countries have tried to accelerate investment from China to Indonesia, especially after the two countries enhanced their Strategic Partnership to Comprehensive Partnership in 2013 and President Xi Jinping proposed the BRI. Pointing out that the low rate of investment to Indonesia was caused by inadequate infrastructure and a poor business environment, the BRI came just in time; it was designed to facilitate infrastructural development along the Belt and Road. In addition, President Widodo made a special plea to President Xi Jinping to encourage more FDI to Indonesia so that it could catch up with other countries and improve trade relations. As a result, investments from China to Indonesia have increased quite significantly; in his farewell speech in 2017, the Chinese Ambassador to Indonesia claimed that China was the number two overall investor in IndonesiaFootnote30 Data from the Indonesian Bureau of Statistics, however, reveals that in 2017 China ranked the fourth of the biggest investors in Indonesia whereas combined investment from China and Hong Kong ranked third in 2017–2018 and second in 2019–2020Footnote31

It is also important to discuss Indonesia-China relations involving the BRI scheme as it is the highlight of Chinese regional and global policy today. In his speech before the Indonesian Parliament in October 2013, President Xi launched the BRI. However, until three years after the speech, the BRI conception remained unclear to Indonesian officials, scholars, and businesses. The Chinese scholars and authority were aware of the international society’s confusion and curiosity about the new policy. They quickly found the flaws of the country’s policymaking mechanism and the need to form wide-ranging political vision, conducive approaches, and long-term perspective in the relationship with surrounding countriesFootnote32 Subsequently, President Xi held the BRI Summit in May 2017 and the second one in April 2019. Although President Widodo attended the first summit and local Indonesian governments were quite keen to propose projects, Indonesia was prudent in taking advantage of the BRI scheme as the President also needed to consider domestic politics and problems in the South China Sea. Nevertheless, under the scheme Indonesia agreed to develop five infrastructure projects, namely tourist infrastructure in Mandalika, strategic irrigation project, dam renovation and safety improvement, regional infrastructure development, and development of slum areas. In total, the AIIB has invested USD 939.9 USD million in Indonesia since its inception in 2016 up to 2019Footnote33 Data from the Indonesian Investment Coordinating Board show that China’s investment in Indonesia from 2014 to 2020 amounted to US$ 19,430 million, a drastic increase from the pre-BRI era (2001 to 2013), which merely accounted for US$ 1,044 millionFootnote34

Despite these developments, the bilateral economic cooperation through the BRI was limited by the influx of Chinese workers to the projects in Indonesia, fear of China’s economic domination, its aggressiveness in the North Natuna Sea and the ethnic Chinese issueFootnote35 These problems, together with the Xinjiang Moslem issues have become sensitive matters in Indonesian domestic politics that hindered President Widodo’s Government’s maneuver to expand further economic relations with China.

Over the last decade, Indonesian-Chinese political and security relations have grown robustly despite several challenges and problems. The reelection of President Yudhoyono for his second term created more stable relations with China. High-level exchanges occurred more often as dialogue mechanisms in various security areas were established through Xiangshan Forums, ASEAN Defense Ministerial Meeting (ADMM) Plus, and other bilateral mechanisms. The leaders took bilateral relations to the next level when President Yudhoyono and President Xi signed the Joint Declaration on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between Republic of Indonesia and People’s Republic of China during President Xi’s visit to Indonesia in October 2013. During the same visit, President Xi gave a speech before the Indonesian Parliament, thus highlighting the importance of continued relations and offering the OBOR scheme for the first time. The Chinese leader must understand that the Indonesian Parliament plays a more significant role in foreign policy under the current democratic political system in Indonesia.

Only months after this visit, however, the two countries became involved in a series of maritime incidents in waters adjacent to Natuna IslandFootnote36 and the Banda Sea, near the border between Indonesia and Australia. Unlike previous incidents, since 2014, the Indonesian Government reacted more assertively and openly when such skirmishes happened, creating headlines in the Indonesian media. As the media were able to provoke negative sentiments against China, Chinese diplomatic staff tried to mitigate tensions by approaching various actors in Indonesia. Negative sentiments toward China were also stimulated by some Indonesian politicians and parties for political purposes in both local and national elections held from 2016 to 2019. Relations between the reemergence of anti-China sentiments and the slowdown of security cooperation between the two countries remain unclear. Cooperation through the defense industry and on non-traditional security threats has not been very robust, either.

On the other hand, cultural relations have grown drastically between Indonesia and China in the last decades. As an important element of the two countries’ Strategic Partnership, people-to-people connections are encouraged and facilitated by the two governments. There has also been increasing academic and cultural cooperation, a growing number of art performances, and significant international tourismFootnote37 The Chinese government has undertaken active and generous cultural diplomacy toward Indonesia, especially among younger generations, scholars, and the Moslem community. A China Radio International (CRI) Indonesian Program was established to reach Indonesian audiences in 2010. Through the CRI-Indonesia Program, China has tried to project not only positive images of China as a country with a long history, rich traditions, and global economic power, but as a harmonious society that is beautiful, modern, and well-managed. Further, it desires to inform the Indonesian people about the opportunities related to improved relations between the two countries and the closeness between Chinese and Indonesian MoslemsFootnote38 The diplomatic strategy through RCI served Chinese national interests by countering its negative images while showing Chinese cultural, economic, political, and media superiority to Indonesia, thereby representing China as a global power and demonstrating friendlinessFootnote39 Improved sociocultural relations between the countries also seem closely related to more positive perceptions about China amid the otherwise scary images resulting from conflicts in the South China Sea and fear of Chinese economic prowess.

In the second decade of the 21st century, Indonesia’s relations with China were quite dynamic as the development in the previous decade continued but some problems emerged such as the Natuna Sea incidents, slowing-down of Chinese construction works on the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway, and the Chinese Ambassador’s criticism of Indonesian reaction to China and the Chinese at the beginning of the pandemic outbreakFootnote40 The influence of Indonesian domestic politics on its relations with China was outstanding in this decade, especially because the China issue was used by President Widodo’s challengers and opposition parties in the 2017 Jakarta Gubernatorial election as well as in 2019 Presidential and Parliamentary Elections. Domestic politics was combined with economic relations, which had been enhanced under the BRI scheme, and with the elites’ divergent perceptions on China. Discussion in this section shows that the three factors seem to shape the two countries’ bilateral relations more significantly than the geopolitical factor.

4. Conclusion

Over the last two decades, domestic politics in Indonesia, the Indonesian perception of China and the Chinese people, the two countries’ economic engagements, and regional-global dynamics have significantly affected the bilateral relations between Indonesia and China.

Despite the prevalence of negative sentiments about China in Indonesia, Indonesia-China relations developed dramatically after the downfall of the Suharto regime. The signing of the Strategic Partnership Agreement epitomized the intensification in these relations, especially in the economic and political fields. However, China’s economic strength also created continuing deficits on the Indonesian side that provoked anti-China sentiments in Indonesia. Nevertheless, the development of dialogue and cooperation in security matters revealed perceptual changes in the Indonesian military about China. The relations also expanded from those focused upon economy to military and cultural matters. The Chinese governmental policy to undertake cultural diplomacy and to strengthen cultural relations reflected not only an awareness of the cultural roles between the two countries, but also their concerns about the prevailing negative perceptions of China and anti-Chinese sentiments in Indonesia. The consolidation of Indonesian democratic politics during this period further caused diverse perceptions about China, countering some of the old negative sentiments but not all.

Stable Indonesian domestic politics have also helped maintain the momentum needed to promote the growth of the bilateral relations between Indonesia and China; harmonious relations between leaders are seemingly very important. While bringing more people into national political discourse and creating a wider spectrum of perceptions about China, Indonesian democratic politics have also hindered the government in taking full advantage of the opportunities presented by China’s rise. In this context, bilateral economic engagements seem to have arisen, while bilateral political-security and sociocultural relations appear to interplay with both national perceptions and domestic politics. Apparently, regional, and global environments indirectly affect bilateral relations as they are perceived and processed through domestic politics. Together, the evidence demonstrates that each of the four factors have had different influences over the two decades; however, the role of domestic politics seems to have dominated.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Professor Akio Takahara of the University of Tokyo for his support and comments in writing this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Evi Fitriani

Evi Fitriani Professor of International Relations, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia.

Notes

1 Indonesian Bureau of Statistics [BPS], “Indonesian Citizens”.

2 Kosasih, “Chinese Indonesians,” 24.

3 Mackie, “Chinese Big Business in SEA,” 179; and Robison, “Economic-Political Development of Capital,” 77.

4 Suryadinata, “Indonesia-China Relations,” 685–6.

5 Kosasih, “Chinese Indonesians,” 55–9.

6 Hamilton-Hart et al., Indonesia. See also Novotny, Torn between America and China.

7 Hadi, “Indonesia, ASEAN and China”. See also Purba, “The Rise of China economic power”.

8 Suryadinata, “Indonesia–China relations”; Robison, “Indonesia”; Sukma, “Indonesia–China relations”; and Anwar, “Indonesia-China relations”.

9 Suryadinata, “The Chinese Minority”, “The Rise of China and the Chinese Overseas”; Kosasih, “Chinese Indonesians”; and Tjhin, “Indonesia’s relations with China”.

10 Kroef, “Normalizing relations with China. See also Fitriani, “Indonesian Perceptions” and Yeremia, “Guarded Optimism”.

11 Takahara, “Sino-Japanese Diplomatic Relations,” 2.

12 Fitriani, “Yudhoyono’s Foreign Policy.”

13 Fitriani, Southeast Asia and ASEM, 26, 80.

14 Wang, “Preservation, Prosperity and Power,” 689.

15 Fitriani, “Indonesian Perceptions of China,” 391–2.

16 The realization was much smaller than the APEC data listed in , which was amounted to US$7,0779.18. Indonesian Investment Coordinating Bureau [BKPM], “Investment from China 2001 to 2010”.

17 Novotny, Torn between America and China, 176.

18 “RI-Cina Intensifkan Kerjasama Pertahanan”.

19 Sonoda, “Asian Student Survey.”

20 ISEAS, The State of Southeast Asia, 43.

21 Ibid, 23.

22 Ibid., 13.

23 From 2016 until 2019 presidential election, Indonesian media, especially whose owners were politicians from opposition parties, frequently published criticism of President Widodo. Among others, Widodo was blamed to have allowed tens of millions of China workers to enter Indonesia and take the commoners’ jobs. See for example Ansam, “10 Juta Pekerja Cina Masuk ke Indonesia.” Subsequently, the President and some of his Ministers corrected the number of Chinese workers in Indonesia. The news was also classified as hoax. See for example: Kuwado, “Bantah Isu Serbuan 10 Juta TKA China.”

24 Wibisono, Political Elites and Foreign Policy, 124–133.

25 Fitriani, “Yudhoyono’s Foreign Policy,” 73.

26 Arase, “Japan’s Strategic Balancing Act,” 4.

27 It was small compared to ASEAN-China total trade, which reached USD $452.2 billion in 2016, almost 56-times larger than all ASEAN-China trade in 1991 as explained by China’s Ambassador to ASEAN, Xu, “ASEAN-China Shared Destiny”.

28 Hadi, “Indonesia, ASEAN and China,” 159.

29 Keterangan dasar hubungan RI-RRT, 20.

30 This statement was a part of the speech delivered by Ambassador Xie Feng at his Farewell Party on June 6 2017. Author was among the attendees.

31 Indonesian Bureau of Statistics [BPS], “Realization of foreign investment”.

32 Xue, “China’s Foreign Policy,” 28–9, 32–3.

33 “Infrastructure for People’s Prosperity”.

34 Indonesian Investment Coordinating Bureau [BKPM], “Investment from Tiongkok: 2001 to 2013 and 2014 to 2014”.

35 Negara and Suryadinata, “Indonesia and China’s BRI”.

36 From 2013 to 2016, there were several incidents between the Indonesian coast guard or navy and Chinese fishing fleets, which were “accompanied” by the Chinese Coast Guard in waters surrounding the Indonesian Natuna Island. The Indonesians considered the waters adjacent to this island as its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), whereas the Chinese claimed it as an historical fishing ground.

37 Approximately 2 million Chinese tourists visited Indonesia annually before the pandemic Covid-19. Chongbo, “Analysis of China-Indonesia Economic Relations”.

38 Pulungsari, “China Radio International-Indonesia”.

39 Ibid.

40 “Coronavirus Crisis; China Advises Indonesia to Not Overreact”.

Bibliography

- Ansam, H. 2016. “‘10 Juta Pekerja Cina Masuk Ke Indonesia,’ Dailami Firdaus: Jangan Sampai Kita Jadi Budak Di Negeri Sendiri” [10 million Chinese workers entered Indonesia, Dalami Firdaus (a local politician): do not become slaves in our own country]. Go Riau.com, July 15. online media. https://www.goriau.com/berita/baca/10-juta-pekerja-cina-masuk-ke-indonesia-dailami-firdaus-jangan-sampai-kita-jadi-budak-di-negeri-sendiri.html.

- Anwar, D. “Indonesia-China Relations: To Be Handled with Care.” Perspective no. 19 (2019, March): 1–7.

- Arase, D. “Japan’s Strategic Balancing Act in Southeast Asia.” Perspectives no. 94 (2019, Nov): 1–10.

- “Bilateral Linkage Database – Investment Flows between APEC Economies: Indonesia and China.” APEC Statistics. (accessed September 27, 2017 and September 2, 2020). http://statistics.apec.org/index.php/bilateral_linkage/bld_result/28.

- “Bilateral Linkage Database - Trade Flows between APEC Economies: Indonesia and China.” APEC Statistics. (accessed September 27, 2017 and September 2, 2020). http://statistics.apec.org/index.php/bilateral_linkage/bld_result/28.

- Chongbo, W. “Analysis of China-Indonesia Economic Relations under the BRI.” Slides presented at the Webinar on International Symposium to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations between China and Indonesia, organized online by the Center for Indonesian Studies of Jinan University, December 5, 2020.

- “Coronavirus Crisis; China Advises Indonesia to Not Overreact.” Tempo, February 4, 2020. https://en.tempo.co/read/1303364/coronavirus-crisis-china-advises-indonesia-to-not-overreact.

- Fitriani, E. Southeast Asia and Asia-Europe Meting (ASEM): State’s Interest and Institution’s Longevity. Singapore: ISEAS, 2014.

- Fitriani, E. “Yudhoyono’s Foreign Policy: Is Indonesia a Rising Power?” In The Yudhoyono Presidency: Indonesia’s Decade of Stability and Stagnation, edited by E. Aspinal, M. Mietzner, and D. Tomsa, 73–92. Singapore: ISEAS, 2015.

- Fitriani, E. “Indonesian Perceptions of the Rise of China: Dare You, Dare You Not.” The Pacific Review 31, no. 3 (2018): 391–405. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2018.1428677.

- Hadi, S. “Indonesia, ASEAN and the Rise of China: Indonesia in the Midst of East Asia’s Dynamics in the Post-Global Crisis World.” International Journal of China Studies 3, no. 2 (2012): 151–166. https://icsum.org.my/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/VOL3NO2-FULL-ISSUE.pdf.

- Hamilton-Hart, N., and D. McRae. Indonesia: Balancing the United States and China, Aiming for Independence. Sydney: The United States Studies Center at the University of Sydney, 2015.

- Indonesian Bureau of Statistics, “Realisasi Investasi Penanaman Modal Luar Negeri Menurut Negara” [Realization of Foreign Investment by Country]. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://www.bps.go.id/indicator/13/1843/3/realisasi-investasi-penanaman-modal-luar-negeri-menurut-negara.html

- Indonesian Bureau of Statistics. “Table 11.9: Indonesian Citizens by Age Group and Ethnicity.” In Population of Indonesia: The Result of Indonesia Population Census 2010. Katalog BPS 2102001. https://um-surabaya.ac.id/ums/assets/regulations/60222dd3-34dc-11e8-8ac5-cced40789894_Penduduk-Indonesia-Hasil-SP-2010.pdf

- Indonesian Investment Coordinating Bureau [BKPM], “National Single Window for Investment (Nswi).” Accessed June 25, 2021. https://nswi.bkpm.go.id/data_statistik

- “Infrastruktur Untuk Kesejahteraan Masyarakat [Infrastructure for People’s Welfare]: An Interview with the Vice President of the AIIB in Indonesia.” Kompas, September 7, 2019.

- Keterangan Dasar Hubungan RI-RRT [Basic Information of Indonesia-China Relations]. Beijing: The Embassy of the Republic of Indonesian, 2014.

- Kosasih, L. “Chinese Indonesians: Stereotyping, Discrimination and anti-Chinese Violence in the Context of Structural Changes up to May 1998 Riots.” Master Thesis, Utrech University, 2010.

- Kroef, J. “Normalizing’ Relations with China: Indonesia’s Policies and Perceptions.” Asian Survey 26, no. 8 (1986): 909–934. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/as.1986.26.8.01p0408q.

- Kuwado, F. 2018. “Bantah Isu Serbuan 10 Juta TKA China, Jokowi Sebut Hanya 23.000 Orang” [Countering the news on the influx of 10 million Chinese workers to Indonesia, Jokowi claimed 23,000 workers]. Kompas.com, August 8. https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2018/08/08/10590981/bantah-isu-serbuan-10-juta-tka-china-jokowi-sebut-hanya-23000-orang?page=all.

- Mackie, J. “Changing Patterns of Chinese Big Business in Southeast Asia.” In Southeast Asian Capitalists, edited by R. McVey, 161–190. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992.

- Negara, S., and L. Suryadinata. “Indonesia and China’s Belt and Road Initiatives: Perspectives, Issues and Prospects.” In Trends in Southeast Asia Series. Singapore: ISEAS, 2018.

- Novotny, D. Torn between America and China: Elite Perceptions and Indonesia Foreign Policy. Singapore: ISEAS, 2010.

- Pulungsari, R. “Representasi Tiongkok Dalam Siaran China Radio Internasional-Indonesia: Strategi Diplomasi Kebudayaan” [China representation in the China Radio International-Indonesia: Cultural diplomatic strategy]. PhD diss., Universitas Indonesia, 2017.

- Purba, M. “The Rise of China Economic Power: China Growing Importance to Indonesian.” Master thesis, the Hague’s Institute of Social Science, 2012.

- “RI-Cina Intensifkan Kerjasama Pertahanan” [Indonesia-China to intensify defense cooperation]. Antara, January 9, 2008. Accessed October 21, 2020. https://www.antaranews.com/berita/89474/ri-china-intensifkan-kerjasama-pertahanan

- Robison, R. “Industrialization and the Economic and Political Development of Capital: The Case of Indonesia.” In Southeast Asian Capitalists, edited by R. McVey, 65–88. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992.

- Sonoda, S. “Asian Student Survey.” Presented at the Workshop of Asian Countries’ Bilateral Relations with China, Tokyo, September 21, 2019.

- Sukma, R. “Indonesia–China Relations: The Politics of Re-engagement.” Asian Survey 49, no. 4 (2009): 591–608. http://www.jstor.org/stable/https://doi.org/10.1525/as2009.49.4.591.

- Suryadinata, L. “The Chinese Minority and Sino-Indonesian Diplomatic Normalization.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 12, no. 1 (1981): 197–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S002246340000507.

- Suryadinata, L. “Indonesia-China Relations: A Recent Breakthrough.” Asian Survey 30, no. 7 (1990): 682–696. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2644558.

- Suryadinata, L. The Rise of China and the Chinese Overseas: A Study of Beijing’s Changing Policy in Southeast Asia and Beyond. Singapore: ISEAS, 2017.

- Takahara, A. “Forty-Four Years of Sino-Japanese Diplomatic Relations since Normalization.” In China-Japan Relations in the 21st Century: Antagonism despite Interdependency, edited by P. Lam Er, 25–65. London: The Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

- Tjhin, C. “Indonesia’s Relations with China: Productive and Pragmatic, but Not yet a Strategic Partner.” China Report 48, no. 3 (2012): 303–315. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0009445512462303.

- Wang, F.-L. “Preservation, Prosperity and Power: What Motivates China’s Foreign Policy?” Journal of Contemporary China 14, no. 45 (2007): 669–694. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10670560500206033.

- Wibisono, A. T. Political Elites and Foreign Policy: Democratization in Indonesia. Jakarta: Universitas Indonesia Press, 2010.

- Xu, B. “Towards a Closer ASEAN-China Community of Shared Destiny.” Presented at the Seminar on ASEAN at 50: A New Chapter for ASEAN-China Relations, Jakarta, July 14, 2017.

- Xue, L. “China’s Foreign Policy Decision-Making Mechanism and ‘One Belt One Road’ Strategy.” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 5, no. 2 (2017): 23–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2016.11869095.

- Yeremia, A. “Guarded Optimism, Caution and Sophistication: Indonesian Diplomats’, Perceptions of the Belt and Road Initiative.” International Journal of China Studies 11, no. 1 (2020): 21–50.