How should the world deal with a rising China? This is perhaps the question of the century, which national leaders are facing and contemplating daily all around the world. For some, China has become the most important economic partner, whose loans, investments and markets prompt them to deepen friendly relations. Many countries have joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative with high expectations for the construction of infrastructure and other development projects. However, economic engagement can cause tension, since it usually entails the inflow of Chinese people as well as money into local societies and China has not shown any hesitation in employing economic coercion to achieve its political goals. The political opposition to the government tends to take advantage of the resultant anti-China sentiments among the local population. For other countries, China’s increasing military capabilities and especially its maritime expansion and assertive actions in disputed waters create a dilemma between rising security concerns and expanding business interests. The political, economic and security interests and concerns in each country’s bilateral relations with China are inevitably affected by the shift in the international environment, especially the state of US-China relations, as well as relations with neighbors and their own China policies. It seems likely that the competition between China and the United States will intensify in the foreseeable future, and few countries will escape its effects.

We easily get the impression that many countries have gone through ups and downs in their relations with China. Probably this is truly so. However, is it the case that entire relationships go through cycles of improvement and deterioration, or only a part of them changes while other aspects remain stable or even develop in the opposite direction? For example, was it not a widely accepted perception at one point in time that “politics are cold but economics are hot in Japan-China relations”? In fact, it is not easy to define “bilateral relations” between countries, although they are discussed daily as if people have a common understanding of what this term means. Are we talking about diplomatic, government-to-government relations, or, are economic and people-to-people relations included? Government-to-government relations have different aspects, too. It is possible for economic and environmental or health ministers of two countries to conduct constructive dialogs while defense and foreign ministers are at each other’s throats. Bilateral relations with China are invariably complicated and multi-faceted.

In order to find a way to deal with China, we must first understand how different countries have been handling their relations with it until now. The papers collected in this special issue stem from a joint project entitled “A Comparative Study of Asian Countries’ Bilateral Relations with China: An Approach from the Four-factor Model,” which was organized by a team at The University of Tokyo and joined by scholars from Indonesia, the Philippines, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, Vietnam and JapanFootnote1 The idea was to deepen our understanding of Asian nations’ relations with China by comparing them using a common analytical framework.

This study is unique in the following ways. First, it adopts a comprehensive and balanced approach to the study of bilateral relations. If narrowly defined, bilateral relations would amount to the diplomatic relations between the central governments of two countries. However, our study adopts a broader definition and considers them as a bundle of relationships between two nations in a variety of areas. The actors concerned are not only central governments and also include local governments, enterprises, NGOs, academic institutions, the military, etc. Since the policy-making process in China is rather opaque, the study inevitably devotes most attention to the other side of the bilateral relationship. However, where possible, the study attempts to look into the factors on the Chinese side as wellFootnote2

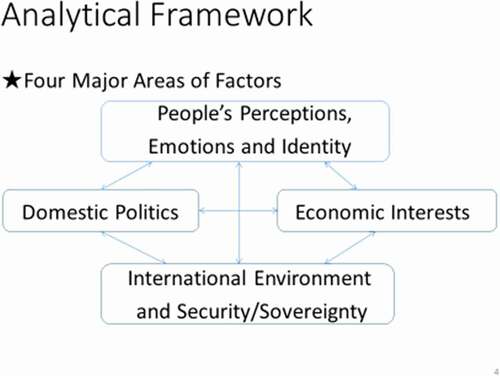

Second, the study pays attention to several distinct factors in the development of bilateral relations and to their interactions. Needless to say, in reality various actors in a bilateral relationship will take a multitude of factors into consideration in their decision-making. Based on an earlier study organized by the members of The University of Tokyo team on the history of Japan-China relations from 1972 to 2012Footnote3, this study adopts a Four Factor Model as its analytical framework. This model classifies into four areas the factors that shape decision-making in relations with China: domestic politics; economic interests; international environment and security; and people’s emotions, perceptions and identity (). Domestic politics can play an important role as nationalist sentiments tend to rise as a result of increasing economic dependence on China and growing Chinese presence in and around a country. This is especially the case in countries with a history of tension between locals and Chinese immigrants, and in those that have experienced a recent and rapid influx of Chinese goods and people. Economic interests usually play a positive role in stabilizing the bilateral relationship as a whole. However, they can also lead to frictions in domestic politics, as mentioned above. In addition, they can function as a source of diplomatic leverage in the manner of geoeconomics, in which economic means such as trade restrictions and tariff hikes or the threat of them are employed to coerce an opponent to change his behaviorFootnote4 Threat perceptions have also increased in some countries due to China’s military buildup and maritime expansion. Considering the importance of the US alliance network and its military presence in East Asia, we place international factors and security factors in the same category. In addition to the above three factor areas, we finally highlight the importance of people’s emotions and perception about the other side of the bilateral relations and identity, which refers to people’s understanding of what their country’s posture and position in the region should be. The study explores these four factors in its analysis of East Asian countries’ bilateral relations with China.

There are two further points to make about this analytical framework. First, of course the relative size of national power of two countries is a fundamental factor in their bilateral relations. However, changes in the balance of power take a long time to make themselves felt and are hard to connect to short-term variations in inter-state relations. Therefore, we shall forgo this aspect and focus on the four factor areas in our analyses. Second, as is indicated by the dual-directional arrows that connect the four factor areas in , there is in reality a lot of interaction between them. For example, clashes over territory can heighten security concerns and deteriorate people’s perceptions about the other side, in turn impacting domestic politics and economic exchanges. Although it is not easy to measure the impact of one factor on another, the study attempts to identify and explain such linkage.

The third characteristic of this study is the way it combines IR and area studies. We find this necessary and important not only in contributing to academic debates but also in informing practitioners. Since the end of the Cold War, one trend in IR studies has been to move away from a narrow focus on international power structures as the determinant of states’ external behavior. In recent years, there has been a growing tendency to attach more weight to the domestic political conditions that policy-makers are actually facing. While maintaining their basic neo-realist perspective, neo-classical realists, notably, have focused on the internal factors that impact external policy-making and its implementationFootnote5 Some argue for more “analytic eclecticism,” advocating for social science research that addresses complicated, concrete issues of policy and practice in the real world This trend is related to another, namely discarding the premise that the state is the only actor in international relations and start looking into the role of other agents such as local governmentsFootnote6 and state-owned enterprisesFootnote7 We are also witnessing efforts to shift the focus of study from big power relations to what goes on in the relationship between China and smaller nationsFootnote8 This new attention is undoubtedly related to China’s rise and the need and difficulty for smaller countries to deal with itFootnote9 All of these developments require a close collaboration between IR and area studies. As far as previous works on bilateral relations from area studies experts are concerned, they tend to adopt a historical approach and usually lack a clear analytical framework. This study fills this gap through the application of the Four Factor Model.

This special issue contains four papers analyzing the bilateral relations between China and Indonesia, the Republic of Korea, Singapore and Vietnam, focusing mainly on the period starting in 2000. These papers are authored by academics from said countries. They are followed by three papers from members of the Japanese team making horizontal comparisons of the four countries, evaluating the functions and importance of three factor areas, namely, domestic politics, economic interests, and people’s emotions, perceptions and identity. In these papers, the Japanese authors introduce the case of Japan-China relations where appropriate to enrich the comparison.

Finally, I would like to mention a most painful loss that we suffered toward the end of the project. Our beloved colleague, Professor Aileen Baviera, left us on March 21 2020 due to complications resulting from COVID-19. Aileen was a wonderful friend, an excellent scholar, and an extremely kind person. Insightful, calm, even-handed, sincere and most reliable, she was an ideal colleague to work with. Her sudden passing is a huge loss for us, for the Philippines, and for the world. She had written her first draft for this study, but was unable to finish it for publication. We dedicate this special issue to her memory. May her soul rest in peace.

Notes

1 The non-Japanese participants were: Evi Fitriani, University of Indonesia; Aileen Baviera, University of the Philippines; Jaeho Hwang, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies; Lam Peng Er, National University of Singapore; John Chuan-tiong Lim, Academia Sinica; Thanh Hai Do, Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam. The Japanese participants were: Kiichi Fujiwara, The University of Tokyo; Haruo Hirano, The University of Tokyo; Hiroshi Itagaki, Musashi University; Tomoki Kamo, Keio University; Shin Kawashima, The University of Tokyo; Masa Kohara, The University of Tokyo; Kazuko Kojima, Keio University; Tomoo Marukawa, The University of Tokyo; Yasuhiro Matsuda, The University of Tokyo; Shigeto Sonoda, The University of Tokyo; Akio Takahara, The University of Tokyo. Antoine Roth, The University of Tokyo, provided research assistance. The project was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

2 One attempt to analyze both sides by applying the Four Factor Model described below, is Takahara, “Forty-four Years of Sino-Japanese Diplomatic Relations Since Normalization”.

3 Takahara and Hattori, Nittchu Kankeishi. Besides Volume I that focused on the political/diplomatic relationship, Volume II on the economic relationship was edited by Marukawa (together with Kenji Hattori). Volume III on the social and cultural relationship and Volume IV on other non-governmental areas were edited by Sonoda.

4 Blackwill and Harris, War by Other Means: Geoeconomics and Statecraft.

5 Ripsman, Taliaferro and Lobell, Neoclassical Realist Theory of International Politics.

6 Sil and Katzenstein, “Analytic Eclecticism in the Study of World Politics”.

7 Hameiri and Jones, “Rising powers and state transformation”.

8 Goh, Rising China’s Influence in Developing Asia; Kuik, “How do Weaker States Hedge?”.

9 There is a quickly growing literature on how Southeast Asian nations are dealing with China’s Belt and Road initiatives. For example, see: Oh, “Power Asymmetry and Threat Points”; Liu and Lim, “The Political Economy of a Rising China in Southeast Asia”; and Soong, “Perception and Strategy of ASEAN’s States on China’s Footprints under Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (sic)”.

Bibliography

- Blackwill, R., and J. Harris. War by Other Means: Geoeconomics and Statecraft. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Goh, E., ed. Rising China’s Influence in Developing Asia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Hameiri, S., and L. Jones. “Rising Powers and State Transformation: The Case of China.” European Journal of International Relations 22, no. 1 (2016): 72–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066115578952.

- Kuik, C. C. “How Do Weaker States Hedge? Unpacking ASEAN States’ Alignment Behavior Towards China.” Journal of Contemporary China 25, no. 100 (2016): 500–514. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2015.1132714.

- Liu, H., and G. Lim. “The Political Economy of a Rising China in Southeast Asia: Malaysia’s Response to the Belt and Road Initiative.” Journal of Contemporary China 28, no. 116 (2019): 216–231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1511393.

- Oh, Y. A. “Power Asymmetry and Threat Points: Negotiating China’s Infrastructure Development in Southeast Asia.” Review of International Political Economy 25, no. 4 (2018): 530–552. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2018.1447981.

- Ripsman, N. M., J. W. Taliaferro, and S. E. Lobell. Neoclassical Realist Theory of International Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Sil, R., and P. J. Katzenstein. “Analytic Eclecticism in the Study of World Politics: Reconfiguring Problems and Mechanisms across Research Traditions.” Perspectives on Politics 8, no. 2 (2010): 411–431. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592710001179.

- Soong, J. “Perception and Strategy of ASEAN’s States on China’s Footprints under Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): Perspectives of State-Society-Business with Balancing-Bandwagoning-Hedging Consideration.” The Chinese Economy 54, no. 1 (2021): 1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10971475.2020.1809813.

- Takahara, A. “Forty-four Years of Sino-Japanese Diplomatic Relations since Normalization.” In China-Japan Relations in the 21st Century: Antagonism despite Interdependency, edited by P. E. Lam, 25–65. Singapore: The Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

- Takahara, A., and R. Hattori, eds. Nittchu Kankeishi 1972–2012 I Seiji [The History of Japan-China Relations 1972–2012 I Politics]. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 2012.