ABSTRACT

Background: The human resources required on large cruise ships can only be secured with crew members from different countries of origin with different health statuses. Method: The present secondary data analysis is to determine whether there is an increased frequency of treatment for crew members for certain diseases or injuries, or a difference in the frequency of treatment for certain groups and/or countries of origin; whether an increased use of dental procedures could be confirmed, and their average costs. The data were collected over six months in 2015 from a major cruise ship company. Results: There were 1,627 treatments for 1,026 crew members. The illness and injury rates were significantly different both in the occupational groups (p < .001) as well as the countries of origin (p = .004). It was confirmed that dental procedures were most frequent (n = 915 cases), in particular for Asian crew members; in contrast to Germans they had a 1.6-fold higher chance of dental procedures.Conclusions: A mixed calculation for dental and jaw treatments for the crew members and the expected passenger treatments would justify the employment of a dentist on the ship. However, medical follow-up costs for crew members on board could be minimised by a previous thorough assessment of their state of health.

Introduction

The growing demand for cruises requires additional, and even larger, cruise ships with the corresponding crew. Sufficient personnel can only be secured by recruiting crew members from different countries of origin. These crew members have different health statuses.

According to the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC) (ILO (International Labour Office). Part A. Maritime Labour Convention – Citation2006 2015a), the employer must ensure and finance medical care on board, onshore, and, if necessary, hospital care for the entire period of employment of a crew member. The period of employment on board is between 3–10 months depending on the contract. It is standard to have a ship’s doctor on the ship, but there is no medical specialist. This means all treatments by specialists (e.g., dentist; radiologist; gynaecologist; ophthalmologist; ear, nose, and throat specialist; and neurologist) must be organised for the next port, which is time-consuming and costly. Until then, usually only a bridging treatment for treating symptoms and pain by the ship’s doctor is possible.

The requirements for the working and living conditions on board, including the medical and health status of the crew, as well as the provisions for medical care by doctors and nurses, are clearly defined in the “Maritime Labour Convention”(ILO (International Labour Office). Part A. Maritime Labour Convention – Citation2006 2015b), the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Bubenzer and Jörgens Citation2015), the “medical examination standards of the International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers” (STCW 95) & Code 2010 Manila Amendments (IMO (International Maritime Organization) Citation2017; Krieg Citation2015), and the Maritime Medicine Ordinance (MariMedV) (Schepers Citation2015).

Any illness or injury of a crew member may result in the loss of medical fitness for naval work. For this reason, it is in the interest of the employer to guarantee cost-effective medical specialist care at European standards in every port where possible (if necessary by a sub-contractor/Assistance). Sick leave days should be kept as low as possible.

Already published studies (Dahl Citation2005a, Citation2005b, Citation2006, Citation2010; Dahl, Ulven, and Horneland Citation2008; Sobotta, John, and Nitschke Citation2008) show a high number of daily medical consultations for crew members and passengers in the on board hospital. Dental treatments make up the largest percentage (Sobotta, John, and Nitschke Citation2007, Citation2008).

The aim of this study is to determine the medical treatment rates (in particular frequency of treatment and type, type of illness) for the crew members on land, on the basis of a secondary data analysis (actual state analysis), using the example of a large cruise ship company. Particularly, it should be clarified whether there is an increased use of treatments for certain diseases or injuries, and whether an increased frequency of treatment for the crew members is present in certain occupational groups (job areas on board) and/or countries of origin (country group). In addition, it was necessary to determine whether an increased use of dental and jaw treatments could be confirmed and the average treatment costs for this. Conclusions for future medical care and care on cruise ships should be derived from the results and discussed from the point of view of cost-effectiveness.

Materials and methods

The data for this analysis were gained in cooperation with the Assistance “med con team” in Reutlingen in the period of May 2015 to October 2015. The primary data was collected by the Assistance “med con team.” The anonymised treatment protocol for specialist consultations on land (hereinafter consultation protocol) forms the database of this analysis. According to information from the cruise ship company, the crew of the researched cruise ships on average consists of 600 crew members.

Performing the examination

The consultation protocol was completed by the attending medical specialist on shore. In addition to socio-demographic information such as gender, nationality, age, and occupation on board, the disease diagnosis, emergency treatment, all specialist visits/treatments (internal medicine, surgical, cardiological, neurological, ophthalmological, etc.) and the diagnostics performed (including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, X-ray, ultrasound) were documented.

The job areas on board (hereinafter occupational groups) were divided amongst gastronomy (GA), management (MA), the leisure sector (LS), service (Service – Technology – Cleaning – Security, STCS), and nautical (officers – other nautical professions, ONP). For the countries of origin, the countries were grouped by continent in Europe (EU), Asia (AS), and North & South America (N/SA). Germany (GE) was separated from the continent “Europe” in order to make a comparison with the other country groups in the evaluations. For reasons of simplification, the continents of origin are called groups of countries or countries of origin in the following text.

According to the data in the consultation protocol, each case was assigned to an occupational group, a group of countries, and also to an illness group (based on the subscale 3 of the work ability index, WAI) (Hasselhorn and Freude Citation2007).

Statistical data analysis

The data analyses were performed with SPSS version 22 and Excel 2016. The ex-post facto design was chosen to examine the questions. Frequencies, averages, and standard deviations were used for the descriptive analysis. Differences in seeking treatments (mean value comparisons) between occupational groups and/or groups of countries were researched using covariance analyses (Kuckartz et al. Citation2010). Age and gender were controlled as covariates. Frequency analyses were performed with the χ2 test (Ostermann and Wolf-Ostermann Citation2005).

In addition, a binary logistic regression was calculated specifically for dental treatments. The first treatments for the two groups of countries with the most dental procedures were compared for this. It was to be examined here whether the variables occupational group and/or country group – controlled by gender and age (as a mean split) – proved to be predictors for seeking dental treatment.

Results

Sample description

On 10 cruise ships, 1,627 treatments were recorded, distributed over 1,026 crew members (male: n = 741, 72%, female: n = 285, 28%) (). The mean age of the crew members was 33 years, with the average age of the male crew members at 34 years and for the female crew members 30 years (p < .001).

Table 1. Sample characteristics by gender.

The use of the treatments by the crew members were distributed amongst the occupational groups as follows: 39% (n = 628) gastronomy, 12% (n = 201) management, 19% (n = 313) leisure sector, 23% (n = 377) service, and 7% (n = 108) nautical. In the groups of countries in the sample, 34% (n = 557) of cases were German, 14% (n = 230) European, 43% (n = 693) Asian, and 9% (n = 147) North and South American crew members.

Treatments for illness groups

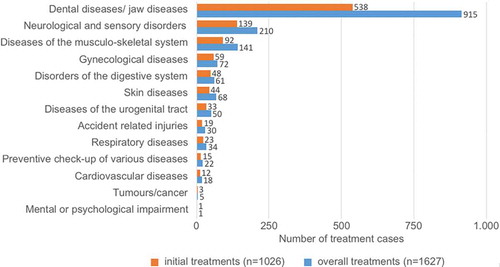

Of the 1,627 treatment cases on land, more than half were dental and jaw treatments (56%), followed by neurological and sensory disorders (13%) and musculoskeletal diseases (9%) ().

Figure 1. Number of treatment cases in the illness groups.

Remarks illness groups: Dental or jaw diseases (dental caries care, jaw abscesses, tooth extractions, root inflammation, emergency dental bridge repair); neurological and sensory disorders (tinnitus, hearing loss, eye disorders, migraine, epilepsy); diseases of the musculoskeletal system (pain in the back, limbs, joints, muscles, sciatic nerve, rheumatism, diseases of the spine); digestive diseases (gall bladder, liver, pancreas, intestine disorders); accidental injury (recreational or occupational accidents, injuries to the back and limbs, burns).

The ranking order of the first treatments did not differ from the order of the total treatments (). This was followed by 368 secondary treatments (23%), 143 third treatments (9%), and 90 four to eight subsequent treatments (5%; follow-up treatments 4–8 were summarised in a group) being necessary.

The treatment frequencies according to occupational groups from the second to the eighth subsequent treatment were found to be relatively constant (p < .001 – .223) in comparison with the first treatments. The same picture emerged in the overview of the treatment frequencies for the countries of origin. Here, too, the treatments required from the second to the eighth subsequent treatment were found to be relatively constant (p < .001–.572) compared to the first treatments.

Treatments by gender and age

Based on the present treatment number, significantly more male (n = 741) crew members sought treatment than female crew members (n = 285).

For the male crew members – with the exception of dental and jaw diseases (60%) – the most common were neurological and sensory disorders (n = 152, 13%) and diseases of the musculoskeletal system (n = 108, 9%). The tumour disease group (cancer) occurred only in men, but only in a total of five cases.

For the female crew members – besides dental and jaw diseases (47%) – treatment for gynaecological disorders (n = 72, 17%) were especially needed. Furthermore, neurological and sensory disorders (n = 58, 13%) as well as diseases of the musculoskeletal system (n = 33, 8%) had to be treated. Psychological impairments were found only in one woman.

In the overall treatments, it was shown that gender is significant in the occurrence of certain diseases (p < .001), however, age is not (p = .658).

Treatments by occupational group

A significantly increased illness rate for certain occupational groups on cruise ships was confirmed (p < .001). In the area of gastronomy, the 628 treatments (39%) for crew members on land (reflected in all illness groups) were striking (). Treatments from the service area followed in second place (n = 377; 23%). In the leisure area there were 313 (19%) treatments; in management 201 (12%) treatments and in the nautical area 108 (7%) treatments were necessary.

Table 2. Treatment cases per group of illnesses by occupation [%].

The analysis of total treatments according to gender showed increased use by male crew members, in particular in the area of gastronomy (). For women, crew members from the leisure sector in particular sought most treatments (36%; n = 156). This percentage is, however, a third lower than amongst men in the gastronomy area (46%; n = 549).

In addition to the dominant dental and jaw treatments, the neurological and sensory disorders were still present in all occupational groups (13%), but with a clear gap (). In all occupational groups, numerous treatments were also needed in the area of musculoskeletal disorders and diseases (9%). For the injuries, the manual occupations dominated in service (3%) and nautical professions (3%) ().

The identified high proportion of dental and jaw treatments occurred most frequently in the areas of gastronomy (62%) and service (58%). Considering the proportion of the other illness groups within the various occupational groups demonstrates a non-systematic picture. However, in all occupational groups an increased need for treatment for neurological and sensory disorders was observed, especially in the areas of management (16%) and the leisure sector (16%). An increased number of cases in diseases of the musculoskeletal system was found in the nautical area (18%).

Treatments by groups of countries (countries of origin)

The overall frequency of treatment differed between groups of countries significantly (p = .004). There was predominance in the use of treatments by crew members from Asian countries (43%) and Germany (34%). In comparison, the European (14%) and American crew members (9%) sought fewer treatments ().

Looked at by gender, in the countries of origin there was a significant (p < .001) difference in seeking treatments between male and female crew members (). The overall highest treatment rate was recorded for female German crew members; they accounted for more than half of female treatments (56%). Asian men dominated for the male crew members; half of them sought treatments.

For the following illness groups, significantly different treatment numbers were found in the country groups (): Dental and jaw diseases (p < .001), diseases of the musculoskeletal system (p < .001), gynaecological diseases (p < .001), digestive diseases (p = .001), neurological and sensory disorders (p = .016). For the accidental injuries (p = .049), the number of treatments, however, showed borderline significance.

Table 3. Treatment cases per group of illnesses by groups of countries [%].

Dental and jaw treatments

According to the determined increased frequency of treatment for Asian crew members (50%) compared to German (30%), it was expected that Asian heritage is a predictor of the frequency of treatment. To clarify this hypothesis, the results were further researched with a binary logistic regression (target variable: groups of countries Germany vs. Asia). To this end, the number of first treatments for Asian crew members was considered in comparison with the German crew members ()

Table 4. Odds ratio – dental and jaw diseases

For the studied model, a model quality resulted according to Nagelkerke-R2 of p = .059, according to which only 6% of the variance can be explained. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test showed a value of p = .861.

Both by gender (p = .003) and country of origin (p = .002) significant effects were shown and are thus predictors of the use of dental and jaw treatments. Age and occupational group did not prove to be a predictor of the use of dental and jaw treatments. For women there is a 0.6 times lower chance in contrast to men and for Asian crew members a 1.6 times higher chance than for German crew members that dental or jaw treatments will be sought.

Discussion

Even though most treatments are available on the boat, certain illness and injury patterns require advanced diagnostic care or treatment on shore. However, it must be considered that different languages, different laws, rules and regulations will be encountered there (Von Pritzbuer Citation2015).

For the present study, 1,627 cases of treatment were documented in ports on land during the research period on 10 cruise ships with 6,147 crew members altogether (male: 4,860; female: 1,287), with significantly more treatments being sought by men than by women. Most treatments were observed in the country groups Asia and Germany. Dental and jaw diseases were treated significantly (p < .001) more frequently than all other diseases and injuries.

In the regression model, the occupational group (job area on board) did not turn out to be a predictor for seeking treatment for dental and jaw diseases while the country group (country of origin Asia vs. Germany) and gender were identified as relevant predictors. Thus, there seems to be a 1.6-fold increased chance for the Asian crew members in comparison to German crew members and a 0.6-fold lower chance for women compared to men to seek treatment for dental and jaw diseases. In further studies an effect size check might be suitable, in order to assess the relevance of the predictors.

Necessity for treatment in the occupational groups

For certain occupational groups an increased need for treatment on cruise ships was confirmed (p < .001). Among the occupational groups, the areas gastronomy (39%) and service (23%) sought a high volume of on shore treatments at 628. In addition to dental and jaw treatments, relatively high treatment numbers for neurological and sensory disorders (11%–16%) as well as for diseases of the musculoskeletal system (6%–17%) were also found in all occupational groups. In this context, a more detailed analysis of causes might be useful, followed by possible adjustments or the adoption of preventive measures. Dahl (Citation2005a, Citation2005b) and Dahl, Ulven, and Horneland (Citation2008) also described high treatment numbers for various professions on the ship, in particular in the areas of on-board kitchens (14%–35%); cabin services (16%–20%); cleaning, food, and drink (6%–20%); as well as service (10%–19%). A breakdown of the number of treatments by illness groups within an occupational group was not made.

Treatment necessity in the country groups

Within the countries of origin, the illness occurrence in the crew members also differed significantly in each illness group (p = .004). For example, neurological and sensory diseases showed a significantly higher treatment rate among German and EU crew members than in other country groups. In the reviewed primary literature, no detailed breakdown of treatments in reference to the countries of origin was found. Dahl (Citation2005b, Citation2006) and Dahl, Ulven, and Horneland (Citation2008) and Sobotta, John, and Nitschke (Citation2007) name the number of nations of the crew on the ship, but they do not present them statistically. For Filipino crew members, a high proportion of treatments (35%) is described (Dahl, Ulven, and Horneland Citation2008), which, however, does not show a statistically higher risk of disease (p < .001) compared to the other countries of origin. In spite of the very variable treatment rates in the groups of countries, no increased treatment risk for certain countries of origin was found in the individual studies (Dahl Citation2005a, Citation2005b, Citation2006; Dahl, Ulven, and Horneland Citation2008; Sobotta, John, and Nitschke Citation2007).

When the necessary treatments as described in the present study are put in relation to the total number of crew members, the following picture emerges:

Of the 2,434 crew members (40%) coming from European countries, according to the shipping company, 524 (that is 22%; in the present study Germany + Europe) had to undergo treatment on land.

There were 3,479 crew members (57%) from Asian countries on board; 401 (12%) of them sought medical treatment on shore.

For 101 (43%) crew members out of a total of 234 (4%) from other countries, treatments had to be arranged outside the hospitals on board their ships.

Treatment necessity for dental and jaw treatments

The conspicuously frequent use of dental and jaw treatments on land by crew members that was already described by Dahl (Citation2005a, Citation2005b, Citation2006) and Sobotta, John, and Nitschke (Citation2007) (11% – 60%) was confirmed. The highest treatment figures were recorded for Asian crew members (50%) and German crew members (30%). Age and occupational group could be excluded as contributing factors for dental treatments. In addition, Dahl (Citation2005b) points out the great deal of organisational efforts for the medical staff, the port agents, and the ship crew during necessary dental treatments on land. This is also reflected in the treatment costs assessed by the employer.

For cultural reasons, it is likely that the dental status of crew members from Asian countries is worse than the dental status of the personnel from other countries at the start of employment. It is possible that dental status preventive exams are not taken seriously in Asian countries and serve more to finance the local dentists (Sobotta, John, and Nitschke Citation2007).

Since the ship’s doctor is not a licensed dentist, they can only provide emergency care in the form of pain relief. Not only a persistent strong toothache, but also the pain medications administered influence the safety in safety-related activities, such as operating machines or ship management, as well as the overall well-being of the affected crew member (Dahl Citation2005b; Sobotta, John, and Nitschke Citation2007). In addition, crew members as well as passengers often conceal their toothache, because they know there is no dentist on board. This can at worst lead to crew members or passengers cancelling their trip or undergoing overpriced treatment in one of the nearest ports (if a dentist is available there), often with poorer quality than in their home country. It can thus be assumed that once there is a dentist on board there will be more visits to the dentist than what has been ascertained here (Sobotta, John, and Nitschke Citation2008).

A dentist on board could contribute significantly to improving the health status of the crew and the passengers. The high number of dental treatments for crew members and delayed treatment as an emergency on land are expensive. The treatment of passengers could be charged privately by the dentist, since these passengers can subsequently submit an insurance claim.

Sobotta, John, and Nitschke (Citation2008) described 22 emergency treatments and three routine treatments per 1,000 persons/month for passengers. That would mean 45 treatments/month per ship on the researched fleet with an average of 1,860 passengers/ship. On the basis of a mixture treatment calculation (root treatment, tooth filling, prosthesis repair, dental implant emergency care, surgical tooth extraction), according to the currently applicable fee schedule for dentists (GOZ) (KZBV Citation2012), it can be calculated that dental and jaw treatment costs 312 euros per passenger on average.

A mixed calculation was made on a statutory insurance basis for dental treatments for the crew members. According to the uniform assessment scale for dental services (BEMA) (KZBV Citation2014), the average treatment costs on the basis of a mixed calculation for the treatment of a crew member would be 103 euros. For the expected treatment number of 45 passengers, revenues would amount to 14,040 euros/month. The cost of dental and jaw treatments of the crew members amounts to an average of 1,648 euros per ship/month. The dentist could thus finance himself through the passenger treatments on the ship. A free co-treatment for the crew could be countered by the provision of a treatment room free of charge.

In its opinion of 7 September 2009, the German Dental Association considers a dental treatment on a cruise ship by a non-dentist as necessary, but this has to be done exclusively from the point of view of general assistance and the elimination of an emergency (Ströker Citation2015). This is clearly defined in Germany in § 1 of the Act on the Exercise of Dentistry (ZHG) (BMJV Citation2015):

“Whoever wishes to continuously exercise his or her dentistry within the scope of this Act requires a licence as a dentist in accordance with this Act.” In § 18 ZHG, it states that “… whoever exercises dentistry without possessing a licence or permission as a dentist …” will be penalised.

As a result, the ship’s doctor is not only faced with greater liability issues but there are also legal licensing consequences. Medical requirements on board are increasing due to the steadily increasing number of passengers and the international composition of the crews. How emergencies are treated often differs in many areas from standard care on land and cannot be compared with the regular European standards of rescue and emergency services. If a patient must be evacuated, disembarkation must be planned in hours or even days depending on the weather conditions. In some regions, disembarkation may even be completely impossible (Seidenstücker Citation2015).

Since 2011, it is no longer possible for civilian personnel to acquire the “Maritime Medicine” certificate. The future ship’s doctor has to rely on the, currently not yet recognised, international intensive course “Maritime medicine aboard cruise ships” (Ottomann, Neidhard, and Seidenstücker Citation2015a) by the agency “Schiffsarztboerse” or on the module courses by the German company “Schiffsarztlehrgang, [Ship’s docotor course] (Citation2018). Nevertheless, he encounters more problems in his job than expected with criminal and private law. Many doctors work as freelance entrepreneurs on the ship and usually have an insurance policy from another country than the one whose flag the ship or cruise line is under (Ottomann, Frenzel, and Kirchner Citation2015b).

Limitations

According to published information from the shipping company, a total of 6,147 crew members were on the ships at the time of the study. A detailed breakdown by country groups, occupational groups, and gender could not be ascertained for individual ships. The research questions can only be answered based on the available data of onshore treatments. Illness data from the on board hospital and medical final reports are not available. No further independent evaluation and control of diseases could therefore be carried out.

The data from this study is analysed in the context of an ex post facto design, which means no causality relationships are ensured. This design has the advantage that it captures many variables with relatively little effort, but independent variables cannot be manipulated nor can all confounding variables be controlled. Along with the lack of temporal distance, only comparative statements can therefore be made.

Conclusions

Since all recorded onshore treatments of the research period were evaluated, this is a total count. Selection effects are excluded by this.

The presence of a dentist during the entire trip could ensure faster and more effective dental care both for the crew and for the passengers. This would have an impact on reducing the resulting supply costs for onshore treatments and working days lost. This would also reduce the burden of liability on the ship’s doctor – usually inexperienced in dental care.

Additional considerations and changes should focus on a more precise implementation of medical examination standards with respect to sea service fitness. This would mean certain illnesses and health problems could be identified in advance, and consequential costs during the employment phase on board could be avoided.

The expansion of the training of the ship’s doctor in the field of dental emergency care would be a discussion approach, but it is difficult to implement because of the current law on the exercise of dental care (ZHG). In further studies, the influence of time of employment and country of origin on the use of treatments on the ship and, if necessary, onshore treatments should be further investigated. This could also check whether the very high proportion of Asian men seeking treatments on land (50%, cf. ) is also confirmed in treatments in the on board hospital. It should also be clarified whether an onshore treatment in defined high-quality clinics/medical centres or with certain practising physicians in the various ports improves the health status of the crew.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- BMJV (Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz). 2015. Gesetz über die Ausübung der Zahnheilkunde [Act on the Exercise of Dentistry 2015]. Accessed 14 April, 2018. http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/zhg/index.html

- Bubenzer, C., and R. I. Jörgens. 2015. “Overview of the Maritime Labour Law.” In Praxishandbuch Seearbeitsrecht [Maritime Labour Law Practical Handbook], edited by C. Bubenzer and R. I. Jörgens, 53–79. 1st ed. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Dahl, E. 2005a. “Medical Practice during a World Cruise: A Descriptive Epidemiological Study of Injury and Illness among Passengers and Crew.” International Maritime Health 56: 115–128.

- Dahl, E. 2005b. “Sick Leave aboard - a One-Year Descriptive Study among Crew on a Passenger Ship.” International Maritime Health 56: 5–16.

- Dahl, E. 2006. “Crew Referrals to Dentists and Medical Specialist Ashore: A Descriptive Study of Practice on Three Passenger Vessels during One Year.” International Maritime Health 57: 127–135.

- Dahl, E. 2010. “Passenger Accidents and Injuries Reported during 3 Years on a Cruise Ship.” International Maritime Health 61: 1–8.

- Dahl, E., A. Ulven, and A. Horneland. 2008. “Crew Accidents Reported during 3 Years on a Cruise Ship.” International Maritime Health 59: 19–33.

- Hasselhorn, H., and G. Freude. 2007. Der Work Ability Index - Ein Leitfaden [The Work Ability Index - a Guide]. Bremerhafen: Wirtschaftsverlag NW.

- ILO (International Labour Office). Part A. Maritime Labour Convention (2006). 2015a. “Title 1. Minimum Requirements for Seafarers to Work on a Ship.” In Compendium of Maritime Labour Instruments. 2nd (rev.) ed. Genf: ILO Publications.

- ILO (International Labour Office). Part A. Maritime Labour Convention (2006). 2015b. “Title 4. Health Protection, Medical Care, Welfare and Social Security Protection.” In Compendium of Maritime Labour Instruments. 2nd (rev.) ed. Genf: ILO Publications.

- IMO (International Maritime Organization). 2017. International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers 1978. Accessed 14 April, 2018. http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/HumanElement/TrainingCertification/Pages/STCW-Convention.aspx

- Krieg, T. 2015. “Notfallmanagement [Emergency Management], Chap. 21.” In Maritime Medizin [Maritime Medicine], edited by C. Ottomann and K. H. Seidenstücker, 171–178.1st ed. Berlin: Springer.

- Kuckartz, U., S. Rädiker, T. Ebert, and J. Schehl. 2010. Stastistik - Eine Verständliche Einführung [Statistics - A Comprehensive Introduction]. 1st ed. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- KZBV (Kassenzahnärztliche Bundesvereinigung). 2012. Gebührenordnung Für Zahnärzte - GOZ 2012 [Fees for Dentists]. Accessed 14.April, 2018. https://www.kzbv.de/gebuehrenverzeichnisse.334.de.html

- KZBV (Kassenzahnärztliche Bundesvereinigung). 2014. Einheitlicher Bewertungsmaßstab Für Zahnärztliche Leistungen - BEMA [Uniform Assessment Standard for Dental Services] Pursuant to § 87 Para. 2 and 2h SGB V. Accessed 14 April, 2018. http://www.kzbv.de/gebuehrenverzeichnisse.334.de.html

- Ostermann, R., and K. Wolf-Ostermann. 2005. Statistik in Sozialer Arbeit Und Pflege [Statistics in Social Work and Nursing]. 3rd ed. Munich: Oldenbourg Verlag.

- Ottomann, C., R. Frenzel, and M. Kirchner. 2015b. “Versicherungs- und steuerrechtliche Belange des Schiffsarztes [Insurance and Tax Concerns for the Ship’s Doctor]. Chap. 6.” In Maritime Medizin [Maritime Medicine], edited by C. Ottomann and K. H. Seidenstücker, 57–66. 1st ed. Berlin: Springer.

- Ottomann, C., S. Neidhard, and K. H. Seidenstücker. 2015a. “Schiffsarztausbildung [Ship’s Doctor Training], Chap. 10.” In Maritime Medizin [Maritime Medicine]. 1st ed. by C. Ottomann and K. H. Seidenstücker, 91–96. Berlin: Springer.

- Schepers, B. F. 2015. “Seediensttauglichkeit/Seeärztlicher Dienst [Naval Service Suitability/Ship’s Doctor Services], Chap. 9.” In Maritime Medizin [Maritime Medicine]. 1st ed. by C. Ottomann and K. H. Seidenstücker, 87–89. Berlin: Springer.

- Schiffsarztlehrgang, [Ship’s docotor course]. 2018. Maritime Medizin. Von Profis. Für Profis [Maritime Medicine. By Professionals. For Proffessionals]. Accessed 14 April, 2018. http://www.schiffsarztlehrgang.de/index.html

- Seidenstücker, K. H. 2015. “Management Medizinischer Notlagen Auf See [Management of Medical Emergencies at Sea]. Chap. 18.” In Maritime Medizin [Maritime Medicine], edited by by C. Ottomann and K. H. Seidenstücker, 143–152. 1st ed. Berlin: Springer.

- Sobotta, B., M. T. John, and I. Nitschke. 2007. “Dental Practice during a World Cruise: Treatment Needs and Demands of Crew.” International Maritime Health 58: 59–69.

- Sobotta, B. A. J., M. T. John, and I. Nitschke. 2008. “Cruise Medicine: The Dental Perspective on Health Care for Passengers during a World Cruise.” Travel Medica 1 (15): 19–24. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2007.00162.x.

- Ströker, J. 2015. “Zahnmedizin [Dentistry], Chap. 35.” In Maritime Medizin [Maritime Medicine]. 1st ed. by C. Ottomann and K. H. Seidenstücker, 333–352. Berlin: Springer.

- Von Pritzbuer, J. 2015. “Ausstattung Des Bordhospitals [Onboard Hospital Facilities], Chap. 13.” In Maritime Medizin [Maritime Medicine], edited by C. Ottomann and K. H. Seidenstücker, 111–114. 1st ed. Berlin: Springer.

![Figure 2. Total treatment cases (n = 1627) by occupational group and gender [%].](/cms/asset/9c0a3288-3bdb-4384-ad2f-1b2e9cd9e4d3/tsea_a_1504469_f0002_oc.jpg)

![Figure 3. Total treatment cases (n = 1627) by country of origin and gender (frequencies [%].](/cms/asset/e7223628-c8d8-43e1-8f47-517e9d0aa276/tsea_a_1504469_f0003_oc.jpg)