ABSTRACT

This paper examines piracy and armed robbery in the Gulf of Mexico, under the framework of maritime security. The results indicate that piratic attacks are most likely underreported by the Government of Mexico. The research findings documented fourteen attacks on supply vessels and offshore platforms for the first half of 2020; only three relevant attacks were officially reported in the same period by the vessel´s (foreign) flag jurisdiction. However, the Maritime Authority of Mexico did not change the security level at any of the ports or territorial sea during the incidents. The maritime security level remained the same (level 1) during 2020, despite several alerts launched by the international maritime community. Recommendations by the respondents (shipmasters, SSO, CSO and PFSO) recommended that a permanent increased security level (level 2) should be implemented in the Southern part of the Gulf of Mexico until this specific problem is resolved. Participants suggested additional special measures to tackle the problem including the evaluation to class the area as a High Risk Area (HRA) and the establishment of a Memorandum of Agreement (MOU), for international cooperation and capacity building with the US Coastguard authorities to promote necessary collaboration towards effectively dealing with these security threats.

Introduction

Piracy and armed robbery attacks against vessels at anchoring areas of ports in the Southern Gulf of Mexico and oil platforms located in the region have increased significantly during the last three years. Only during the first seven months of 2020, research efforts have documented 14 piratical attacks, but only 3 of them were officially reported to the International Maritime Organization (IMO) by the attacked vessel’s flag jurisdiction and not by Mexico, the State where these incidents occurred.

The International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS) Code, is one of the most important sets of maritime security regulations of international law, developed by the International Maritime Organization (IMO). These provisions are established in Chapter XI-2 of the Safety of Life at Sea Convention 1974 (SOLAS Convention) and include crucial instruments to fight piracy, armed robbery and other type of transnational organized crime at sea, as the Port Facility Security Assessment (PFSA) and respective Port Facility Security Plan (PFSP), and the Ship Security Assessment (SSA) and Ship Security Plan (SSP). These solutions include a series of protocols for awareness and actions, to respond to security threats at sea, including piracy, armed robbery, terrorism, illegal trafficking of drugs, weapons, and illegal migration. The ISPS Code is a “comprehensive set of measures to enhance the security of ships and port facilities, developed in response to the perceived threats to ships and port facilities in the wake of the 9/11 attacks in the United States” (International Maritime Organization Citation2012).

Part A of the Code establishes mandatory provisions; the not mandatory (“recommended”) part B encompasses guidelines explaining how to better comply with the mandatory requirements of part A. In any case, core instruments of the ISPS Code are security incident reports and security incident investigation, as well as the IMO register of pirate attacks and armed robbery against vessels. Meeting the obligation on the part of States to report piratical attacks to IMO is vital in order to maintain transparent and reliable statistics, which are crucial as the first step in the response chain for allocation of resources by authorities and international organizations to tackle piracy.

Section 12.2, subsection 8 of the ISPS Code, establishes that among other duties and responsibilities of the Ship Security Officer (SSO) it is necessary to report all security incidents, which must be reported both to the maritime administration of the coastal State where the incident occurred and to the maritime authority of the vessel’s flag jurisdiction. Furthermore, Section 17.2 establishes the duties and responsibilities of the Port Facility Security Officer (PFSO), including “reporting to the relevant authorities and maintaining records of occurrences which threaten the security of the port facility”.

Avila-Zuñiga-Nordfjeld and Dalaklis (Citation2017) have pointed out that the analysis of security incidents’ root causes is the cornerstone of “updating” the relevant security assessment, which was previously used as the base for the development of the security plan, with the aim to remove any loopholes. Additionally, if security officers identify new security threats, they must also implement the necessary adjustments. Cutting a long way short, “it is crucial to keep security incident records updated”, as the first indicator that there is room for further improvement.

Designated Maritime Authorities have already specified the type of maritime and port security incidents that must be immediately reported to them for official investigation in certain countries. Indicative examples include terror attacks; bomb warnings; hijack, armed robbery against a ship; discovery of firearms, drugs, weapons and explosives and unauthorized access to port facilities and restricted areas. In addition, security threats, breaches of security and security incidents, including date, time, location, response to them and the person-authorities to whom they were reported must be recorded and documented in the security incidents records (International Maritime Organization Citation2012).

Then, maritime authorities from member States have the obligation to report acts of piracy and armed robbery against ships to IMO, according to the MSC/Circ.623/Rev.3,Footnote1 as approved by the Maritime Safety Committee, at its eighty-sixth session of June 2009. At the same time, they must conduct a maritime security incident investigation, which shall run parallel to the judicial investigation concerning the crime. The objective of such investigation is that the entire maritime community can learn the lesson and understand the causal factors of why a particular incident happened, preventing similar incidents from reoccurring, avoiding similar mistakes in the future. It must be highlighted that in the case of very serious security incidents, as pirate attacks and armed robbery against vessels there must be a reassessment of the PFSA/SSA and adjustment of the PFSP/SSP, accordingly, as required by the ISPS Code, which includes the increase of security levels.

As highlighted by Nordfjeld (Citation2018), the IMO, has established three different security levels:

Security Level 1(normal) requires the minimum protective security measures at all times,

Security Level 2, which requires that additional protective security measures shall be maintained for a period of time as a result of the heightened risk or a security incident and,

Security Level 3, which requires specific protective security measures which shall last only for a limited period of time when risk for a security incident is probable or imminent, even when it is not possible to identify the target.

Security Level 3 involves the strictest security measures and its priority is the security of the port, port facilities, vessels and society that may be affected by a security incident and may result in the suspension of commercial operations. Security response under Level 3 is transferred to the government or other organizations responsible for dealing with significant security threats/incidents.

The ISPS Code establishes that the process of setting security levels focuses on the alert for the perceived risk of terrorism attacks, but Member States can include other security threats in their risk assessment like pirate attacks and armed robbery against vessels and oil platforms. Maritime Security levels apply to ships sailing over the territorial sea and port facilities. However, governments can implement different security levels for different ports, port facilities and different areas of their territorial waters.

In any case, the change of security levels must be communicated to the port, its port terminals and vessels attempting to call that port or port facilities, as well as vessels in transit or attempting to transit those waters. The Maritime Authority must ensure that other relevant authorities and interested parties as terminal operators, ship owners, Flag Administration, P&I clubs and insurance´s representatives are notified in the case of serious security incidents as armed robbery against vessels, and that they are given instructions about how to handle evidence material for the subsequent security incident investigation.

Research objectives

The objectives of this paper are the following:

To study current security risks related to piracy and armed robbery against vessels and oil platforms in the Southern Gulf of Mexico;

To examine the response of the Maritime Authority concerning setting and change of maritime security levels as part of the response chain of the Maritime Authority from the Mexican Government to tackle pirate attacks and armed robbery;

To analyse the impact of the lack of the implementation of a maritime transport policy with particular focus on a maritime security policy, including the respective allocation of resources.

The scope of the research study is on the Southern Gulf of Mexico; however, it can be applicable to other countries facing similar security threats and insecurity levels in the Latin American region, where there has also been registered malpractices concerning the official report of pirate attacks and armed robbery against ships.

Theoretical background

Piracy and Armed Robbery against ships

Article 101 from the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) from 1982, establishes several conditions for what type of unlawful actions can be considered piracy. These conditions include that the incident must involve violence, detention or depredation and that it must occur on the high seas, outside the jurisdiction of any Government, as observed in the definition below:

Piracy consists of any of the following acts:

any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any act of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft, and directed:

on the high seas, against another ship or aircraft, or against persons or property on board such ship or aircraft;

against a ship, aircraft, persons or property in a place outside the jurisdiction of any State;

any act of voluntary participation in the operation of a ship or of an aircraft with knowledge of facts making it a pirate ship or aircraft;

any act inciting or of intentionally facilitating an act described in subparagraph (a) or (b).

A certain number of pirate attacks occur within territorial waters of different countries around the globe. There was an extensive disagreement among ship-owners and other shareholders with this definition since it left outside those incidents registered in the waters of a national jurisdiction. The Maritime International Bureau published their own definition of piracy, which disregarded the issue about this. As a response the Maritime Safety Committee, from IMO approved the revised circular MSC.1/Circ.1334 to revoke MSC/Circ.623/Rev.3 on guidance to ship-owners, ship operators, shipmasters and crews for preventing and suppressing acts of piracy and armed robbery against ships, at its eighty-sixth session, held from 27 May to 5 June 2009.

The revision was carried out on the guidance provided by IMO taking into consideration the work of the correspondence group on the review and updating of MSC/Circ.622/Rev.1, MSC/Circ.623/Rev.3 and resolution A.922(22), established by MSC 84.

Under the new circular, the definition of “armed robbery against ships” was restructured, to reflect the view of France and other States articulating that the definition for armed robbery against ships should not be applicable to incidents committed seaward of the territorial sea. Also the motive of the act “private ends” was added.

The new definition reads: “Armed robbery against ships” means any unlawful act of violence or detention or any act of depredation, or threat thereof, other than an act of piracy, committed for private ends and directed against a ship or against persons or property on board such a ship, within a State’s internal waters, archipelagic waters and territorial sea”. The International Maritime Bureau (IMB) accepted both definitions and started to apply them in their register of security incidents from the IMB Piracy Reporting Centre, which is manned 24 hours to receive and register reports of attacks or attempted attacks worldwide.

Circular MSC.1/Circ.1334 establishes that in addition to hijacking of ships, holding of the crew hostage, and the theft of cargo, other targets of the attackers include cash in the ship’s safe, crew possessions and any portable ship’s equipment and that therefore, the effective application of the ISPS Code is important and strongly encouraged.

It also encompasses a series of recommended practices suggested to owners or masters of ships operating in areas where attacks occur, which are based on reports of incidents, advices published by commercial organizations and measures developed to enhance ship security.

The ISPS code

The ISPS Code is an international regulation developed upon theories of risk management to secure ports, vessels, their crews and the marine environment, where information about threats, impacts and vulnerabilities are used to assess the residual risk.

Concerning maritime security Capt. Hesse (Citation2003), wrote that the rationale behind the new chapter XI-2 and the ISPS Code of the SOLAS conventions is the approach of a risk management activity by determining which security measures are appropriate and necessary upon a risk assessment for each particular case. He added that the purpose of the ISPS Code is to pride a standardised framework for the evaluation of risk to enable governments to offset changes in threat levels according to changes in vulnerability of ships and port facilities. Avila-Zuñiga-Nordfjeld (Citation2018) confirmed that “The ISPS Code represents a structural change in port and maritime security management and should be seen as a basic framework for port and maritime security, and international cooperation, covering specific standardised security measures”.

The ISPS Code demands the development of a ship/port security assessment and the respective security plan prepared through a six stage assessment, which are the following: (a) Pre-assessment; (b) threat assessment; (c) impact assessment; (d) vulnerability assessment; (e) risk scoring and; (f) risk management. The internationally known formula for risk is used, as follows: RISK = THREAT X IMPACT X VULNERABILITY.

The IMO (Citation2012) has recognised as “high”, a residual risk score of 27 or more, which is considered unacceptable, and thus the ship/port must seek and implement additional control measures. While a residual risk score of between 8 and 24 has been declared as “medium”, which requires management monitoring; a residual risk score of 6 or less is considered as “low” or “tolerable risk”, where no further control measures are needed.

Avila-Zuñiga-Nordfjeld and Dalaklis (Citation2017) explained that the ISPS Code “only applies to passenger ships, high speed passenger vessels and cargo vessels of 500 gross tonnage and upwards. As well as Mobile Offshore Drilling Units (MODUs) in transit and at ports (but not to fixed and floating platforms and MODUs on the oil field); and all type of port facilities serving vessels offered for international voyages”. The authors remarked that the “extent to which the guidelines apply on ships will depend on the type of the ship, its cargo and number of passengers, as well as its sailings routes and the features of the port of or port facilities visited by that specific ship. Regarding the application of guidelines to port facilities, it will depend on the type of carriages and vessels visiting that particular facility and its ordinary trading routes”.

As Avila-Zuñiga-Nordfjeld (Citation2018), correctly pointed out, the ISPS Code does not apply to offshore activities. The IMO has left it up to member States to decide whether to extend its application to fixed Mobile Offshore Drilling Units (MODUs) and floating oil platforms, located in the Continental Shelf. The referred author recommended that for the case of Mexico and taking into consideration its level of offshore activities related to oil and gas exploration and production, they should develop their own regulation extending the application of the ISPS Code security measures to vessels engaged in offshore activities, MODUs on location and to fixed and floating platforms.

According to the ISPS Code, the Ship Security Assessment and the Ship Security Plan must both include written procedures on measures to prevent or suppress pirate attacks and armed robbery. Circular MSC.1/Circ.1334 from IMO establishes that all ships operating in waters or ports where there has been registered piracy and armed robbery against vessels should carry out a security assessment as a preparation for development of measures to prevent an attack. The security assessment should take into account the following aspects:

“the risks that may be faced including any information given on characteristics of piracy or armed robbery in the specific area;

the ship’s actual size, freeboard, maximum speed, and the type of cargo;

the number of crew members available, their proficiency and training;

the ability to establish secure areas on board ship; and

the equipment on board, including any surveillance and detection equipment that has been provided.

The ship security plan or emergency response procedures should be prepared based on the risk assessment, detailing predetermined responses to address increases and decreases in threat levels”, IMO (Citation2009b).

Ocean governance

Ocean governance means the coordination of various uses of the ocean and protection of the marine environment. It is also defined as the necessary process to sustain ecosystem structure and functions (Pyć Citation2016). This author adds that an effective ocean governance requires the implementation of globally-agreed international rules and procedures, regional actions based on common principles, and national legal frameworks and integrated policies.

These policies shall include aspects related to maritime security as port and maritime security, piracy, terrorism, transnational organized crime, illegal migration, unlawful fisheries and proliferation of drugs and weapons. Some of the most substantial challenges of an effective ocean governance are associated to maritime security.

The United Nation Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides the legal framework for national sovereignty rights and international obligations at sea. It also serves as the fundament for regional security cooperation, which is crucial to maintain safe and secure oceans and to protect the marine environment.

National maritime security policy

The Cambridge Dictionary (Citation2020) defines policy as “a set of ideas or a plan for action followed by a business, a government, a political party, or a group of people”. It is also the driving force of an Organization (international, governmental, or non-governmental), guiding its decisions according to a strategic plan, generating rules etc., but differing from rules or law and therefore it must not be confused with politics.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development from the United Nations highlights the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 targets (adopted by world leaders in September 2015) build on the previous Millennium Development Goals aiming to achieve what the previous did not succeed. The 17 SDGs apply to all countries worldwide, which must integrate them into their national policies.

As part of the United Nations, the IMO is working towards the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the associated SDGs. Certainly, most of the SDGs can be linked directly or indirectly to maritime transport, as a natural facilitator of the world trade and global economy. “While SDG 14 is central to IMO, aspects of the Organization’s work can be linked to all individual SDGs, (IMO, Citation2020a).

The Development and implementation of a Maritime (Transport) Policy fortifies the maritime capacity, as well as the correct administration and exploitation of marine resources and appropriate protection of the marine environment, which contributes to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs). While a maritime policy is wide encompassing, a National Maritime Transport Policies (NMTP) deals with specific maritime transport issues for a particular State following its national characteristics, challenges and interests.

A NMTP must include strategies and plans for the ocean/maritime governance, which shall be overarched by the national interests, based on a sustainable development, including an integrated coastal zone management. As well as the juridical framework, encompassing both the international and national dimension, which must reflect its sectoral interests established in the guidelines and principles of the ocean/maritime governance, which must follow its constitution, laws and regulations.

On this context, a National Maritime Security Policy (NMSP) is the part of the NMTP with own plans, strategies, human and material resources and guidelines aimed to secure its ports, the ports assets, its users, maritime shareholders and its waters including its marine resources as well as vessels and their crews transiting its waters.

As mentioned before, one of the biggest challenges of an effective ocean governance are related to maritime security. Thus, it is a prerequisite to develop and implement a NMTP, including the essential part of the NMSP, since it requires international cooperation to face threats as piracy, maritime terrorism and armed robbery against vessels, bearing in mind that securing oceans and the marine environment is an international duty, as it is the combat against transnational organized crime. The NMSP must also follows national and international regulations and particularly the ISPS Code.

Methodological approach

The research methodology includes semi-structured interviews conducted to Ship Security Officers (SSO) and Company Security Officers (CSO) working in the Southern Gulf of Mexico on board vessels or shipping companies with vessels sailing in that region. From the twenty persons invited to participate five of them rejected the invitation. Qualitative semi-structured interviews, based on a questionnaire encompassing 30 different questions were employed to allow new viewpoints to emerge freely, particularly about opinions and perceptions on security threats.

The purpose of the study was described to participants in an information cover-sheet letter where the research objectives were clearly described, explaining that their participation was voluntary, confidential and without any economic contribution or gifts. The total number of interviewed participants was 15 persons, all of them practicing in areas of maritime security. The interviews were conducted in May-June 2020, taped recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data was examined line-by-line, and the main categories and themes were identified and coded using thematic analysis and constant comparison of data.

The selection of methods was chosen because of its suitability in both, law and social sciences, disciplines where they are widely used, in accordance with the exploratory nature of topics related to security and criminology. They were considered appropriate for this case, where one of the general objectives is to study the diverse risks related to piracy and armed robbery against vessels and oil platforms in the Southern Gulf of Mexico, as well as the response of the Maritime Authority of Mexico to tackle this kind of security threats.

McCracken (Citation1988) stated that structured and semi-structured questionnaires with open questions, can help the researcher to avoid being obtrusive and engaging in active listening strategies during the interview and enables to give order to the different subjects during the interviews, which simplify data analysis while developing categories or themes.

The research also employed the classical documental analysis to investigate the number of pirate attacks and armed robbery against vessels that occurred in the mentioned area during the period of 1 January–30 July 2020. The document analysis is based on data collected on armed robbery against vessels for 2020 in the Gulf of Mexico and particularly in the southern part of the gulf.

Representatives from the Secretariat of the Navy of Mexico were also asked to participate in the research effort, but they did not provide any respond to the invitation. Thus, researchers used press releases, media articles and document analysis to further analyse the response from the Maritime Authority to this growing problem in the Campeche Sound.

Results

On the basis of the semi-structured interviews 15 themes were identified. They reflect a rather poor response from the Maritime Authority of Mexico to the security threats that affect the Southern Gulf of Mexico. These themes are the following:

Authorities from the Secretariat of the Navy (SEMAR) are not making the required incident investigation for reporting to the IMO.

Piracy and armed robbery attacks increased significantly during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic.

86.6 % of the interviewed have several other roles on board the ship, in addition to SSO, as safety officers, radio operators, HLO and other administrative duties, which limits the time used for security duties.

26.6 % of them have never had access to the Ship Security Plan because the vessel and the master are from other nationalities and do not trust the SSO.

In all cases where the ship was attacked or other ships in the proximity were attacked, the SSO increased the security level to level 2.

It takes two hours or more to the authorities from the Secretariat of the Navy to arrive to the place of the attack, to provide help, but by then, the pirates have left the vessel.

The Port Security Officer and authorities of the port have never increased the port security level to level 2, even during the attacks that resulted with injured people.

100 % of the participants interviewed SSO recommended to declare the area “High Risk Waters (HRA)” for the international maritime community.

100 % of the participants interviewed recommended that the ports of the area increase the port security level to operate at level 2 always and until the number of attacks decrease to an acceptable security level.

60 % of the participants interviewed recommend vessels sailing in the Southern part of the Gulf of Mexico to sail at security level 2.

40 % of the interviewed participants mean that it is not necessary to increase the security level of the vessel while sailing in the Southern part of Gulf of Mexico, but at the anchor area.

100 % of participants interviewed recommend to increase the ship security level to level 2 while anchored at the anchor area or whenever anchored for oil exploration and production operations.

73 % of the interviewed says that the authorities from the Secretariat of the Navy lack material resources as high speed patrols and combustible/fuel to perform vigilance duties.

100 % of the interviewed participants evaluate as very bad or none the response of the Secretariat of the Navy to the armed robbery and piratical attacks.

100 % of the interviewed participants believe that the use of private military security companies will increase the security risk due to the corruption in the country.

Concerning the documental analysis, the research effort documented a total of 14 piratical attacks of armed robbery against vessels during the period of 1 January to July 30 2020; from these, only three were officially reported by the attacked vessel’s flag (foreign) jurisdiction to IMO, these are documented in , while the rest are reported with detail in below.

Table 1. Acts of maritime piracy and armed robbery against ships officially occurred in the Southern Gulf of Mexico, reported by the attacked vessel’s flag (foreign) jurisdiction to IMO and not by the Coastal (Mexico) State, period 1 January-30 July 2020

Table 2. Acts of maritime piracy and armed robbery against ships occurred in the Southern Gulf of Mexico documented through documental analysis and not officially reported by the Mexican Maritime Authority to the IMO, period 1 January-30 July 2020

The documentation of all these pirate attacks and armed robbery against vessels emphasizes another very important finding for the entire international maritime community, which is the serious underreporting of this type of maritime security incidents, committed in the ports of Mexico, its berths, anchorage areas and territorial waters by the coastal State of Mexico and its Maritime Authority to IMO.

General discussion

Due to this widespread malpractice of not reporting pirate attacks and armed robbery against vessels in the Latin-American region, there are not trustworthy statistics about maritime security incidents for this part of the globe, to make a realistic comparison with previous years. Yet, the interviewed SSO coincided that this kind of attacks against ships increased exponentially during the pandemic of COVID-19 in 2020 in the area.

An average of 16 piracy and armed robbery attacks against vessels, MODUS, oil platforms and fishing ships is registered in the Southern Gulf of Mexico, (Infobae Citation2019).

The United States through the US MARAD (Maritime Administration, Citation2020) launched the Alert 2020–004A, on Southern Gulf Of Mexico-Vessel Attacks. In this document, they established that the U.S. government is aware of at least 20 fishing vessels and 35 oil platforms and offshore supply vessels that have been targeted by pirates and armed robbers since January 2018 in the Bay of Campeche area of the southern Gulf of Mexico and that significant underreporting of attacks in this area is suspected. The alert adds that these attacks have involved the discharge of firearms, crew injuries, hostage taking, and theft, according to details provided by the Office of Naval Intelligence’s on the 30 April 2020 Worldwide Threat to Shipping (WTS) report (US MARAD).

Similar alerts about this and the related security risks of the area have been published by other maritime administrations worldwide, as the Ship Security Advisory Alert n. 04–20 by from the Republic of the Marshall Islands Citation2020. As well as the alert notice F-410 (DDCM) V.01 from the Maritime Authority of Panama Citation2020, where they remind “all Panama vessels transiting the Bay of Campeche, Gulf of Mexico and the State of Tabasco, in the Republic of Mexico to follow the PIRACY merchant marine circulars procedures and recommendations. Also, Panama Flag vessels under the SOLAS V/19 regulation must comply with LRIT and AIS requirements”.

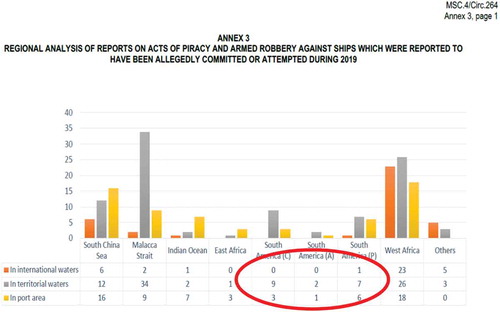

29 maritime security incidents of this type occurred in Central and South America during 2019 according to MSC 4 Circ. 264, ANNEX 3 from IMO (Citation2020b). As observed in below, it is clearly revealed that most pirate attacks occurred within territorial waters, followed by incidents committed in port areas, usually at the anchorage areas while waiting for berth and only one of them happened in international waters, at the high seas. , shows the flow diagram for attacks in coastal waters and the respective official report to IMO.

Figure 1. Acts of piracy and armed robbery against ships in South and Central America reported in 2019. Source: IMO (Citation2020b)

Figure 2. Flow diagram for attacks in coastal waters & incidents report to IMO. Source: MSC. 1/Circ. 1334 Annex

Yet, if a security incident of this type occurs, it not only must be officially reported to IMO, but additionally, an official investigation must start and be completed to share it with the IMO, so the entire maritime community can learn from that particular attack. Resolution A.1025(26) from IMO and adopted on 2 December 2009, on the “Code Of Practice for the Investigation of Crimes of Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships,” urges Governments “to implement the Code of Practice, to investigate all acts of piracy and armed robbery against ships under their jurisdiction, and to report to the Organization pertinent information on all investigations and prosecutions relating to these acts so as to allow lessons to be learned from the experiences of ship-owners, masters and crews who have been subject to attacks, thereby enhancing preventative guidance for others who may find themselves in similar situations in the future”. This circular also calls Governments to develop international, regional and national agreements and procedures to simplify and expedite cooperation for the application of efficient and effective measures to prevent acts of piracy and armed robbery against ships.

During interviews to various newspapers, representatives from the Maritime Authority of Mexico underestimated the gravity of the attacks and said that they were not considered maritime piracy, but rather robbery, since piracy must occur at the high seas.

Randrianantenaina (Citation2013), discusses the zonal approach to the concept of maritime piracy as written in article 101, from the UNCLOS and says that certainly, it depends on which part of the maritime zones is perpetrated and adds that:

“Despite the fact that the definition doesn’t specify the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) but only the high seas and a place outside the jurisdiction of any State, it applies to the EEZ in virtue of article 58(2) of the LOSC which indicates that articles 88 to 115 (Related to the high seas) are applicable to the EEZ as far as they are not contrary to the provisions regarding this maritime zone. As coastal States exercise only sovereign rights over non-living and living resources in the EEZ, it makes the provisions on piracy applicable to this maritime zone” Randrianantenaina (Citation2013).

Though, the obligation from Government States to report security incidents to IMO, addresses not only acts of maritime, but also armed robbery against vessels. While several incidents of those documented by the researchers in the Southern Gulf of Mexico were committed at the anchorage area of different ports from the area, several other against MODUS fixed at the oil field occurred in the EEZ.

From the information collected during the interviews it was subtracted that the pirates/robbers are armed with different type of weapons including assault rifles, shotguns, pistols, machetes and knives, targeting fixed MODUS and offshore infrastructure, as well as vessels anchored at the anchorage area of ports while waiting for berth, but not ships sailing. Moreover, they operate at night in small groups of 4 to 15 individuals, aboard several small fiberglass boats, hulled craft and fishing boats with multiple high-powered outboard motors enabling fast travel to the oil fields located between five and ninety-five nautical miles offshore and anchor areas. They use violence to take the crews as hostages while they steal around the vessel. It was also revealed that hey carry on frequency radios with access to the marine control and navy authorities radio bands (L Band) so they know when they are sailing and approaching the area to provide security to vessels in distress.

As part of the response from the Mexican Navy to tackle the problem, on 20 May 2020, the Secretariat of the Navy launched the “Operacion Refuerzo” (re-strengthening operation) to improve maritime security in the Campeche area. Through circular number 1631/2020 the Harbour Master from Ciudad del Carmen, Campeche, and based on circular UNICAPAM/DIGACAP/SONDA number 009/2020 from 20 May 2020, declared the establishment of “Secured Areas of Anchorage” Citation2020, which were supposed to patrolled with the high speed patrols (patrullas interceptoras) BR-17 Y BR-18 and the oceanic patrol PC ARN OAXACA PO-161 .

In the same document, the Navy established the official control measures between vessels and the MRCC. In addition, they required the application of the ISPS Code to fixed oil-platforms and fixed MODUS, offshore supply vessels operating under cabotage and other type of vessels of less of 500 GT serving in the domestic market, including fishing vessels, but without making the necessary legal reforms. Thus, that requirement neither was supported by international law, nor by national law and the shipping companies and shipmasters were not legally responsible to follow such “obligation” (Circular n. 872/20-2020).

Nonetheless, participants of this study evaluated as very poor or non-existent the response by the Mexican Navy to the security incidents, and affirmed that “the navy patrols are at berth most of the time, because of the ‘austerity programme’ from the Federal Government to save fuel and they are only moved after the incidents to collect the information,” (Respondent n.5). The limited budget allocated to the Navy by the government of Mexico might be a result of the lack of a maritime security policy. The IMO in cooperation with the World Maritime University delivered a workshop for the development of the MTP already back in November, 2018. However, it has not been made yet.

The majority of respondents recommended that ports of the area increase the security level to operate at level 2 and that shipmasters increase the ship security level to level 2 while anchored at the anchor area or whenever anchored for oil exploration and production operations.

These statements concurred with the fact that some vessels were also attacked at the “secured and guarded area” by the Secretariat of the Navy of Mexico, as the case of the Offshore Supply vessel Carson River, of Mexican flag on 13 July 2020. Indeed while the authors were doing the last revision of this article, another armed robbery occurred against the MODUS Coban A, located some nautical miles from the Port of Dos Bocas, in Tabasco Mexico, on the night of 24 November 2020. Thus the recommendation from the respondents concerning the declaration of the Southern Gulf of Mexico as a High Risk Area (HRA) seems to be rational in order to increase security measures in the region and allow the international maritime community to be better prepared to meet these threats in those high risk waters.

As Bueger (Citation2015) explains, the campaign against piracy included the work to define the affected territory and established the called “zones of exception,” which are special spaces in which particular forms of rules and regulations apply. Best Management Practices BMP3 (Citation2010), as analysed by Bueger (Citation2015) established that “the High Risk Area for piracy attacks defines itself by where the piracy attacks have taken place”.

If the notion of “piracy attacks” is a clearly definable legal term, the notion of “piracy activity” is more ambiguous and open to interpretation. “Piracy” is in the BMP4 not defined in legal terms, but as “all acts of violence against ships, her crew and cargo. This includes armed robbery and attempts to board and take control of the ship, wherever this may take place,” Bueger (Citation2015).

Some of the control measures for a HRA include the establishment of a safe zone for shipping as an International Recommended Transport Corridor, which is usually protected by international naval missions. However, the declaratory of a HRA is a lengthy process that involves the whole world maritime community and cooperation with the Security Council of the United Nations and the Safety and Security committees from the International Maritime Organization. Thus in the meantime, some of the measures included in the Best Management Practices against piracy and armed robbery could also be implemented in the area to a certain extent in order secure ships and its crews and of course the marine environment, considering that the Campeche Sound is an area with high offshore activity.

Conclusions

Maritime piracy and armed robbery against ships in the Southern part of the Gulf of Mexico has increased significantly during the last years; results indicate that piratical attacks are severely underreported by the Government of Mexico.

The Maritime Authority from the Government of Mexico is not fulfilling its duties and obligations before the international community concerning the official report of incidents involving acts of piracy and armed robbery against ships, as established in MSC.1/Circ.1334 from IMO (Citation2009a), neither are they complying with the requirements of the ISPS Code with regards to the setting of maritime security levels in accordance with the perceived risk. This prevents vessels from foreign flags secure their ships and their crews when entering such risky waters. The lack of trustworthy statistical figures creates further difficulties towards the international cooperation for the implementation of security measures to secure such waters and ships sailing in the area. It is urgent that the Government of Mexico improves the security status of the area by correcting these malpractices and reports to IMO all acts of piracy and armed robbery allegedly committed against ships within its territorial waters and the EEZ.

The lack of a Maritime Transport Policy including the Maritime Security Policy (MSP) might negatively affect the security of the region. It is crucial that the Government of Mexico improves the security of the area with effective vigilance, changing from a reactive to a proactive approach.

Recommendations

The development of a Maritime Security Policy by the Maritime Authority of Mexico, with respective strategies and specific actions to secure ports, vessels and their crews is urgent, including a proper allocation of human material resources to tackle the problem. The strategy shall include the combat of logistic infrastructure from pirates both at sea and onshore.

It is highly recommended that ports from the Southern part of the Gulf of Mexico adjust accordingly the security level under which they operate.

It is recommended that vessels sailing the Southern part of the Gulf of Mexico remain vigilant to security threats and ensure that all anti-piracy and armed robbery procedures and measures from the SSP are in effect.

It is highly recommended that vessels anchored at anchor areas of ports from the Southern part of the Gulf of Mexico or whenever anchored for oil exploration and production operations operate under an increased security level.

It is highly recommended to make the necessary reforms to extent the application of the ISPS Code to offshore activities, cabotage and ferries as previously proposed by Nordfjeld (Citation2018).

It is recommended that special security measures should be considered for implementation in the Southern part of the Gulf of Mexico, including the evaluation of the HRA classification, as suggested by respondents.

It is recommended the establishment of a Memorandum of Agreement (MOU) for international cooperation and capacity building with the US Coastguard authorities, to reduce security threats and protect the marine environment of the area, since an attack against a MODUS or a fixed platform would be a marine disaster that because of the marine streams would easily reach the US coast.

Abbreviations

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Guidance to shipowners and ship operators, shipmasters and crews for preventing and suppressing acts of piracy and armed robbery against ships.

References

- Avila-Zuñiga-Nordfjeld, A. (2018). Building a National Maritime Security Policy. WMU Research Report Series.

- Avila-Zuñiga-Nordfjeld, A., and D. Dalaklis. 2017. “Enhancing Maritime Security in Mexico: Privatization,Militarization, or a combination of both?” In Economic challenge and new maritime risks management: What blue growth?, edited by P. Chaumette. Nantes (pp. 97), France: Gomylex.

- Avila-Zúñiga-Nordfjeld, A., and D. Dalaklis (2017). “Improving Mexico’s energy safety and security framework: A new role for the Navy?” Marener 2017, Conference, Malmö, Sweden.

- BMP3. 2010. Best Management Practices 3. Piracy off the Coast of Somalia and the Arabian Sea Area (Version 3 -June 2010). Edinburgh: Witherby Seamanship.

- Bueger, C. 2015. Zones of Exception at Sea: Lessons from the debate on the High Risk Area.

- Cambridge Dictionary. (2020). “Policy meaning.” November, 27, 2020. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/policy

- Hesse, H. G. 2003. “Maritime Security in a Multilateral Context: IMO Activities to Enhance Maritime Security.” The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law 18 (3): 327–340. doi:10.1163/092735203770223567.

- Infobae. (2019). “Piratas en el Golfo de México asaltan hasta 16 barcos al mes: Fingen ser pescadores y sorprenden a sus víctimas.” November 27, 2020. https://www.infobae.com/america/mexico/2019/11/14/piratas-fingen-ser-pescadores-para-asaltar-embarcaciones-crecen-asaltos-en-el-golfo-de-mexico

- International Maritime Organization. (2009a). “Resolution A.1025(26) Code Of Practice for the Investigation of Crimes of Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships.” November 27, 2020. https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/KnowledgeCentre/IndexofIMOResolutions/AssemblyDocuments/A.1025(26).pdf

- International Maritime Organization. 2009b. MSC.1/Circ.1334. Guidance to shipowners and ship operators, shipmasters and crews on preventing and suppressing acts of piracy and armed robbery against ships. June 23. London.

- International Maritime Organization. 2012. Guide to maritime security and the ISPS Code. London: International Maritime Organization.

- International Maritime Organization. (2020a). “IMO and the sustainable development goals.” November 28, 2020. https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Pages/SustainableDevelopmentGoals.aspx

- International Maritime Organization. 2020b. MSC 4 Circ. 264, ANNEX 3 Regional analysis of reports on acts of piracy and armed robbery against ships which were reported to have been allegedly commited or attempted during 2019.

- Maritime Authority of Panama. 2020. Alert notice F-410 (DDCM) V.01 Gulf of Mexico -Bay of Campeche -Tabasco -Republic of Mexico.

- Maritime Authority of the Republic of the Marshall Islands. 2020. Ship Security Advisory Alert n. 04–20.

- McCracken, G. 1988. The long interview. London: Sage Publications.

- Nordfjeld, A.-Z. A. 2018. Building a National Maritime Security Policy. Malmo. Sweden: WMU Publications.

- Pyć, D. 2016. “Global Ocean Governance.” TransNav, the International Journal on Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation 10 (1): 159–162. doi:10.12716/1001.10.01.18.

- Randrianantenaina, J. E. 2013. Maritime piracy and armed robbery against ships: Exploring the legal and the operational solutions. The case of Madagascar. The United Nations: Division For Ocean Affairs And The Law Of The Sea Office Of Legal Affairs.

- Secretariat of the Navy. 2020. circular number 1631/2020.

- Secretariat of the Navy, Mexico, Capitanía de Puerto Regional de Dos Bocas. 2020. Circular n. 872/20 Comunicado a la comunidad marítima.

- US Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration. (2020). “MSCI Advisory, 2020-008-Southern Gulf of Mexico-Vessel Attacks.” June 18, 2020. https://www.maritime.dot.gov/msci/2020-008-southern-gulf-mexico-vessel-attacks

- World Maritime University. (2018). Maritime Transport Policy Workshop., (p. Module I). Ciudad de Mexi.