ABSTRACT

Fossil fuel as the beacon of industrialization emits carbon dioxide more than any other source of energy. Carbon dioxide emission among other Green House Gases is the dominant gas responsible for global warming and damaging impact of climate change. Given the enormity of the impact of climate change, the United Nations General Assembly in 2015 adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of which ‘goal 13ʹ was a call for climate action to mitigate the drastic effect of climate change by reducing global warming to 2°C above pre-industrial levels or 1.5°C by 2030. Shipping in the maritime sector accounts for over 80% of the global trade and hugely dependent on Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO) and emits about 2.7% of the global carbon dioxide. Against this backdrop, the concern of this study is, therefore, to ascertain the level of progress in global decarbonization for sustainable development focusing on international shipping in the maritime sector. The documentary method of research was adopted for the study while Win-Win Solution served as the conceptual framework. The study analyzed the efforts to decarbonize the shipping industry and determine if the maritime sector will likely achieve green shipping target by 2030.

Introduction

One of the biggest global challenges facing the world before and after COVID-19 pandemic is climate change caused by Green House Gases emission, chiefly carbon dioxide, giving rise to increasing earth temperature, global warming and causing rising sea levels and extreme weather events. Taalas (Citation2020a) maintained that “2016 was the warmest year and 2019 was the second warmest while 2010–2019 was the warmest decade on record.” However, Fountain, Migliozzi, and Popovich (Citation2021) assert that “2020 was effectively tied with 2016 for the hottest year on record, as global warming linked to greenhouse gas emissions showed no signs of letting up.” According to Guterres (Citation2020), “as the new year approaches, the challenges are clear: the #COVID-19 response will consume 2021 and the climate crisis will drive the decade.” For the United Nations, “2021 can be a year of a quantum leap towards carbon neutrality.” As reiterated by the United Nations, “making peace with nature is the defining task of the 21st century. It must be the top priority for everyone everywhere.”

Currently the decarbonization targets in the maritme sector “pose challenges for a range of stakeholders, from ship owners, charterers and cargo owners to ship builders, designers, engine manufacturers, fuel suppliers financiers and policy makers (Det Norske Veritas Citation2021).” The global community under different fora such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Kyoto Protocol, Sustainable Development Climate Action, Paris Agreement, Green New Deal, etc. have sought ways to reduce global carbon dioxide emission and global warming below two degrees Celsius (2°C) or below one and half degrees Celsius (1.5°C), if possible. The highest annual decline in carbon dioxide emission since after Second World War was recorded in 2020 due to the shutdown of global economy as a result of COVID-19 pandemic. According to McSweeney and Tandon (Citation2020), experts have argued that this improvement is only temporary because climate change is not on pause and once the global economy begins to recover from the pandemic, emissions are expected to return to higher levels.

According to Global Carbon Project-GCP, “Global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fossil fuel and industry are expected to drop by 7% in 2020, as a result of the effects of Covid-19 lockdowns” (2020) estimate, “carbon dioxide emission clocked in at 34 billion tons, that is, a fall of 2.4GtCO2 compared to 2019. It further indicated that Fossil CO2 emissions had fallen in all the world’s biggest emitters – 12% in the US, 11% in the EU, 9% in India and 1.7% in China (McSweeney and Tandon Citation2020).” These biggest emitters are equally the biggest industrialized nations. Carbon dioxide “remains in the atmosphere and oceans for centuries. This means that the world is committed to continued climate change regardless of any temporary fall in emissions due to the ‘Coronavirus pandemic’ (Taalas Citation2020b).”

Shipping had been described as the most internationalized industry, and assuming it were a country, it would be the sixth biggest Green House Gas emitter. International vessels with “intricate web of multi-state ownership transverse the global commons of the high seas carrying goods that have been produced or extracted piecemeal all over the world for delivery to national and international markets. There is virtually nothing about the industry that is not international (Cowing Citation2017).” According to Schlanger (Citation2018), “roughly 90% of all internationally traded goods are a massive source of greenhouse gases, in part because they use ‘bunker fuels,’ the dregs of the fossil-fuel refining process. It’s extremely cheap, one reason you can get international goods all over the planet. But it’s also one of the dirtiest diesel fuels, with much higher carbon content than the diesel fuel used in cars.” In the view of Green (Citation2018), “ships are very fuel-efficient in terms of transporting cargo, but the Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO) used by 80% of the world’s shipping fleet is nasty stuff. It’s more carbon-intensive than other fuels and produces other Green House Gases as well as air pollutants such as sulfur dioxide, which causes acid rain.” According to International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) study, “HFO use increased by 75% between 2015–2019 (Gerretsen Citation2020).” Gallucci (Citation2017), stressed that “the industry’s reliance on high-carbon fuel poses a major stumbling block for global efforts to rein in pollution and curb global warming. If left unchecked, its carbon footprint is expected to soar in coming decades, just as emissions from cars and power plants decline that of shipping could cancel out progress in other sectors.”

International Maritime Organization (IMO) remarked that “carbon emission from shipping could rise to as much as 250% by 2050 as the world economies grow and expand due to increase in global trade.” According to International Transport Forum (Citation2017), “what drives the growth of global shipping emissions is the rise of international trade, projected to almost double by 2035 and growing at a rate of approximately 3% per year until 2050.” Cames et al. (Citation2015) “in their study of mitigation targets for international aviation and maritime transport, forecasted that the shipping industry could be responsible for 17% of global CO2 emission in 2050 if left unregulated.” International Energy Agency (IEA) in this regard had forecasted that “carbon dioxide emissions for this year will be the second biggest annual rise in history as global economies pour stimulus cash into fossil fuels in the recovery from the Covid-19 recession and will put climate hopes out of reach unless governments act quickly (Harvey Citation2021).”

Giving the internationalization and complex nature of the shipping industry which makes it difficult for its emission estimation and control to be captured by national governments, it came under the regulation of International Maritime Organization (IMO), a United Nations’ specialized agency that “continually contributes to the global fight against climate change, in support of the UN Sustainable Development Goal 13, to take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts (Organization Citation2019).” As a way of combating Green House Gases (GHGs) emission particularly CO2, the IMO in 2018 came up with the first ever initial strategy of reducing GHGs emission in the shipping industry with “the ambition of reducing the shipping industry’s greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50% by 2050 and reducing the carbon intensity of emissions by 40% by 2030, and 70% by 2050 compared to 2008 levels (Hellenic Shipping News Citation2020).” This study is, therefore, concerned with the review of the level of progress in decarbonizing the shipping industry, analyze the efforts towards decarbonizing the industry, identify barriers and determine if the maritime sector will likely achieve green shipping target by the year 2030.

Conceptual Framework

The concept upon which this study is premised is win/win solution. It is an approach in which parties collaborate or contribute towards a common plan of action to achieve a common goal for their common benefit. Decarbonization of the shipping industry is an “all hands on deck affair” to reduce global warming; achieve green shipping and safety of the planet. It requires the genuine commitment and collaboration of all stakeholders in the industry for the advantage of human community and vice versa. According to Gomersall (Citation2021), “achieving the development, maturing and scaling up of solutions will not only require significant investment but an unprecedented scale of collaboration and cooperation.”

EFFORTS TOWARD DECARBONIZATION OF SHIPPING INDUSTRY

The efforts to decarbonize “International Shipping” can best be described by International Maritime Organization (IMO), the United Nation’s agency saddled with the responsibility of regulating international shipping, as it is beyond the purview of national governments. According to Organization (Citation2019), “it fell to scientists to draw international attention to the threats posed by global warming. Evidence shows that in the 1960s and 70s concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere was increasing and that led climatologists and others to press for action.” However, record shows that it took years before international community could respond. Even at that, the responses have always been dotted by unharmonious and divergent views from stakeholders within and outside the shipping industry.

In response by the international community, an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was created in 1988 by the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), which issued first assessment report in 1990 and stated that global warming is real. The report spurred government to create the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) endorsed around 1992 followed by Kyoto Protocol adopted in 1997 in Kyoto, Japan, an international agreement linked to (UNFCCC) of which the major feature is binding targets for ‘37ʹ industrialized countries and the European community for reducing Green House Gas (GHG) emissions. Another touted global response is the 2015 Paris Agreement:

”The Paris Agreement on climate change was made in 2015 by Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and entered into force in 2016. The Paris Agreement central aim is to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by keeping a global temperature rise this century well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius. The Paris Agreement does not include international shipping, but IMO, as the regulatory body for the industry, is committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions from international shipping (IMO, Citation2019)”.

The IMO laid out its “initial climate strategy” in April 2018, with a final revised version set to come out in 2023 (Timperley Citation2017 Citation2017)). Levels of ambition directing the initial strategy are as follows:

Carbon intensity of the ship to decline through implementation of phases of the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) for new ships: to review with the aim to strengthen the energy efficiency design requirements for ships with the percentage improvement for each phase to be determined for each ship type, as appropriate;

Carbon intensity of international shipping to decline: to reduce CO2 emissions per transport work, as an average across international shipping, by at least 40% by 2030, pursuing efforts towards 70% by 2050, compared to 2008; and

GHG emissions from international shipping to peak and decline: to peak GHG emissions from international shipping as soon as possible and to reduce the total annual GHG emissions by at least 50% by 2050 compared to 2008 whilst pursuing efforts towards phasing them out as called for in the Vision as a point on a pathway of CO2 emissions reduction consistent with the Paris Agreement temperature goals.

Deducing from Talanoa Dialogue (2018), “in 2011, IMO adopted mandatory measures to improve the energy efficiency of international shipping representing the first-ever mandatory global energy efficiency standard for an international industry sector, the first legally binding instrument to be adopted since the Kyoto Protocol that addresses GHG emissions and the first global mandatory GHG-reduction regime for an international industry sector.” The Dialogue further stated that “the technical and operational requirements that apply to ships of 400 GT and above, are known as the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI), applicable to new ships, which sets a minimum energy efficiency level for the work undertaken (e.g., CO2 emissions per tonne-mile) for different ship types and sizes, and the Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP), applicable to all ships.” These mandatory requirements, according to the Talanoa Dialogue, entered into force on 1 January 2013 and the Energy Efficiency Operational Indicator (EEOI) for monitoring operational energy efficiency of the ships also remains available for voluntary application.

IMO Energy Efficiency Partnership Projects Towards GHG Reduction in Shipping Industry

IMO’s energy-efficiency measures implemented through global partnership projects includes:

Global Maritime Energy Efficiency Partnerships (GloMEEP) project supports the uptake and implementation of energy-efficiency measures for shipping, thereby reducing greenhouse gas emissions from shipping. GloMEEP was launched in 2015 in collaboration with the Global Environment Facility and the United Nations Development Programme.

Global Industry Alliance (GIA) to Support Low Carbon Shipping was launched in 2017 under the auspices of the GloMEEP project, is identifying and developing solutions that can help overcome barriers to the uptake of energy-efficiency technologies and operational measures in the shipping sector.

The Global Maritime Technology Cooperation Centres Network (GMN) project, funded by the European Union, has established a network of five Maritime Technology Cooperation Centres (MTCCs) in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, Latin America and the Pacific. Through collaboration and outreach activities at regional level, the MTCCs have been focusing their efforts since 2018 on helping countries develop national maritime energy-efficiency policies and measures, promote the uptake of low-carbon technologies and operations in maritime transport and establish voluntary pilot data collection and reporting systems.

GreenVoyage2050 project, a collaboration between IMO and the Government of Norway The project was launched in 2019, and will initiate and promote global efforts to demonstrate and test technical solutions for reducing GHG emissions, as well as enhancing knowledge and information sharing to support the IMO GHG reduction strategy.

In October 2020, a working group within IMO (Intersessional Working Group on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships (ISWG-GHG 7), during their seventh session came up with draft amendment in line with the implementation of the initial IMO GHG reduction strategy which requires ships to combine a technical and an operational approach to reduce their carbon intensity. New short-term measures were developed and forwarded to the “Marine Environmental Protection Committee (MEPC 75) in November 2020, as a decision making body in IMO which if approved by the committee would then be forwarded for adoption at the MEPC 76 session, in 2021 (International Maritime Organization Citation2020)”. According to IMO, “the draft amendment proposed that short-term measures should be those measures finalized and agreed on by the Committee between 2018 and 2023”.

Barriers to decarbonization

According to Hellenic Shipping News (Citation2020), “Shipping emissions are expected to continue to grow thereby increasing the importance of addressing barriers to decarbonisation.” There are so many barriers to international shipping decarbonization ranging from institutional, financial and technical aspects; however, a few of the fundamental barriers will be identified.

Lack of alternative fuel/renewable energy that has commercial viability for international shipping: According to, “discussions of fuels cannot be limited simply to arguments about whether ammonia is better than hydrogen, or whether methanol might be more viable than biofuels; rather, needed conversations should encompass ‘big picture’ like encouraging decarbonization actions through levies or financial mechanisms” that will finance the development of commercially viable biofuels/renewable energy. Today, “we have neither clarity nor consensus on the sustainability issues surrounding the fuels being explored for shipping’s decarbonisation, and the criteria to assess their sustainability remain undefined (Atkinson)Citation2020”.

Politics: It seems the urgency of addressing carbon dioxide and other GHG emissions does not appeal to all governments/political leaders. This is more of a concern when industrialized and big emitting nations/leaders are involved. For instance, Donald Trump (American President) announced in 2017 that America was exiting the laudable “Paris Agreement” and he did. However, on the contrary and upon being elected (Joe Biden – US President) “pledged to lead the world to lock in enforceable international agreements to reduce emissions in global shipping and aviation (Gerretsen Citation2020)”. According to Edmund Hughes, the IMO’s head of air pollution and energy efficiency, “while the IMO has received proposals from some countries that it should align itself with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal, not all governments necessarily agree with this (Timperley Citation2017 Citation2017))”. According to Green (Citation2018), “a coalition of highly ambitious nations led by small Island states in the Pacific pushed for deeper cuts by calling for full shipping decarbonization by 2050 but Brazil and Panama among the largest shipping registries in the world resisted it citing concerns about detrimental effects on trade. Likewise, neither the United States nor China signed the voluntary declaration in which states affirmed their commitment to a shipping agreement that is consistent with the Paris agreement”. According to India Energy Minister; “net zero targets are ‘pie in the sky’ due to sharp division between major global emitters at series of meetings designed to make progress on climate change. Poor nations want to continue using fossil fuels and the rich countries “can’t stop it” (McGrath Citation2021, April 1)”.

Transparency of data: Marine Environmental Protection Committee- MEPC during their 70th session in October 2016, mandated ships to record and report their fuel oil consumption.

“Ships of 5,000 GT and above (representing approximately 85% of the total CO2 emissions from international shipping) will be required to collect consumption data for each type of fuel oil they use, as well as, other specified data, including proxies for “transport work”. The aggregated data will be reported to the flag State after the end of each calendar year and the flag State, having determined that the data have been reported in accordance with the requirements, will issue a Statement of Compliance to the ship. Flag States will be required to subsequently transfer this data to an IMO Ship Fuel Oil Consumption Database. The Secretariat is required to produce an annual report to the MEPC, summarizing the data collected (Talanoa Dialogue, 2018)”.

The challenge to this data collection practice is transparency because no shipping line will report against itself. Such report should not come from shippers themselves, for no one sets an exam for him/herself and fails. However, both shipping industries and National Governments have to be transparent and sincere in their data collection and transmission knowing full well that the impact of global warning affects us all. For the safety of the planet, integrity should be premiumed over profit and safety over cost.

Capital: The major challenge to the introduction of Zero Emission Vessels (ZEVs) that will guarantee green shipping by 2030 is capital. Ships as well known are long-term capital investment, and taking older models out of commission before the end of their life span is a costly adventure. Added to this is the fact that banks are reluctant to fund technology that is yet to be developed. According to Gallucci (Citation2017), “most brands and shipping companies alike remain reluctant in doing anything that would raise the cost of transporting goods or the final price tag”.

Emission ownership dilemma: This dilemma emanate from the fact that carbon dioxide emissions from international shipping cannot be attributed to any specific nation because of the international and complex nature of shipping and vessels ownership. Estimation can hardly near accuracy. For instance: “a state cannot include shipping emissions in its reduction targets if the international community cannot figure out how these emissions should be allocated to states. In fact, Christiana Figueres, the former Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC, stated that emissions from international vessels are not even covered under the legalities of the convention simply because they are not national emissions (personal communication 2016) in Cowing (Citation2017)”.

The challenge of flag of convenience: Open registry in disguise offers ship owners the opportunity to cut corners or breach international shipping regulations for profitable interests without being held responsible, such as pollution of ocean environment. In some scenario, both flagging States and IMO are incapable of enforcing compliance from such erring ship owners. A good example is provided by Cowing (Citation2017) & DeSombre (Citation2006), thus:

“the limited enforcement capacity of flagging countries and the inability of the IMO to compel enforcement is seen with the ‘oil tanker Prestige’. This particular vessel flew a Bahamian flag, had a Greek captain, a Filipino and Romanian crew, was registered in Liberia, owned by a Swiss company that was itself owned by Russian nationals, was carrying oil from Latvia to Singapore, classified by the U.S., and insured by the United Kingdom (DeSombre Citation2006). When the ship sank in 2002, causing the largest oil spill in both Spain and Portugal’s histories, the 11 countries that had stakes in this one vessel pointed fingers at each other with no one party taking responsibility. As this exemplifies, the flag state is not always willing or able to take responsibility and the IMO did not step in to force the Bahamian hand. The Prestige also exemplifies the great need to be able to say with certainty who and what is responsible for all matters pertaining to ships so that catastrophes of all sorts may be mitigated. If that party is to be the flagging state, then mechanisms need to be put into place to ensure responsibility is carried through and to either provide support to countries that may need assistance in enforcement or preventing countries from offering open registries”.

Level of progress in decarbonizing the shipping industry

Progress is incremental; however, experts argue that “incremental progress, past and present, is unsatisfactory – in part because of the outsize influence of the shipping industry in the IMO rulemaking process. Indeed, it is common practice to have private shipping registry companies represent nation-states at the IMO (Green Citation2018).” These private interests influence regulations to fit into their business interest and programme. In doing this, they slow progress in decarbornizing shipping industry in favour of their business interest. This is more so, when carbon dioxide emissions from international shipping cannot be attributed to any specific nation. There is nothing much wrong with the incremental approach; excerpt for meddling of private interests “Ships are long-term capital investments, as such taking older models out of commission before the end of their natural life is a costly proposition (Green Citation2018)’.

Shipping industry is complex because of complex interest and huge capital involvement representing governments, NGOs, and private interests. It is part of the reason shipping industry lacks a central body that enforces regulations and IMO as the regulating body cannot be forceful in rule implementation for decarbonization. For instance, it takes a huge cost to build or own a ship, “the economical life span of an average ship is 20–30 years which means that ships built now and in recent past will be the ships sailing by 2050 and retrofitting an existing ship to a new propulsion system is, if possible, a very costly affair. So every ship built from now on, ought to be emission free, or at least almost emission free (Langelaan Citation2019).” This is creating crisis in the shipping industry as there is a fall in demand for ship by ship owners due to uncertainties about which of the renewable alternative energy will be commercially viable and technically suitable for new shipping technologies. Added to that is the acceptability by the industry in order to achieve carbon intensity emissions reduction of 40% by 2030, and 70% by 2050 compared to 2008 levels. According to the forecast of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in (Green Citation2018) “the new technologies, alternative fuels and renewable energy could almost fully decarbonize the shipping industry by 2035. That would eliminate the equivalent of the annual emissions of 185 coal plants. Though these ambitious goals are technically feasible, politics are the main constraint.”

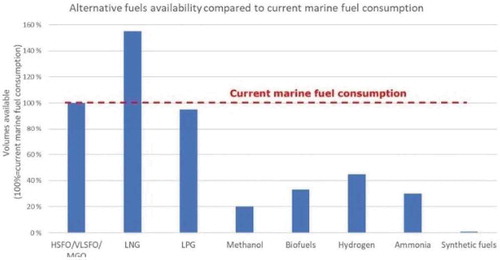

Source: DNV GL in SAFETY4SEA EDITORIAL TEAM (2020)

Much as the rest of all the alternative fuels are more expensive when compared to Heavy Sulfur Fuel Oil (HSFO), the mostly advocated fuel for shipping decarbonization is bio-fuel, the most expensive of all of them but most echo-friendly. shows that its availability is at the rate of 35%. While Liquefied Natural Gas availability at 155% appears to be a promising alternative, however, it cannot sustain international shipping and it’s not echo-friendly as bio-fuel, Methanol (20%), Hydrogen (45%) and Ammonia (30%). According to Pavlenko et al. (Citation2020, January 28), “more and more ships, including container ships and cruise ships, are being built to run on liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), which emits approximately 25% less carbon dioxide (CO2) than conventional marine fuel in providing the same amount of propulsion power. However, LNG is mostly methane, a potent greenhouse gas (GHG) that traps 86 times more heat in the atmosphere than the same amount of CO2 over a 20-year time period.”

further illustrates that LNG emits more CO2 than other conventional fuels over a long period of between 20 and 100 years. In line with , World Bank in its recent report, “rejected Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) as a sustainable fuel for shipping in the future, and the battle for climate-friendly fuels has increased. World Bank discovered that LNG has a limited role in the decarbonization of the shipping sector, and also advised member countries against new investments in infrastructure and relevant policies that support the use of LNG as a bunker fuel for international shipping (Hellenic Shipping News Citation2021).”

Table 1. Well-to-hull emissions for LNG and a selection of conventional marine fuels, in grams (g)/megajoule (MJ)

At any realm, “cost and benefit” is central to the level of progress in decarbonization of the shipping industry or in terms of IMO enforcing emission reduction, much less when IMO has no enforcement mechanism. IMO will have to implement what is generally acceptable to all parties due to cost and is usually dependent on member states for enforcement of regulations. According to Majuro (Citation2017), “IMO treaties only come into force on the basis when a certain proportion of the world fleet has backed them.” Some environmental experts have equally argued that of the major carbon emitting industries shipping is the least. Therefore decarbonization of the industry ought to be gradual and within the scope and interest of parties involved due to its capital intensity. According to, “a study conducted by University Maritime Advisory Service (UMAS), Energy Transition Commission (ETC) among others in 2020, approximately 1.4 USD – 1.9 USD trillion in investment would be required to decarbonize the shipping sector (Gomersall Citation2021).”

Findings

What is expressed here is the likelihood of achieving green shipping target between now and 2030.

For now, “no study or organization has given assurance that fully decarbonizing the shipping industry is feasible by 2030, neither is there clarity or consensus on the sustainability issues surrounding the fuels being explored for shipping’s decarbonization. The criteria to assess the fuels sustainability remain undefined as Atkinson observed.” It, therefore, implies that most of the strategy on decarbonization in the shipping industry is work in progress. Concrete progress in global or commercial sense is yet to be achieved in terms of renewable energy and compliant technology. As a result of cost, it is still business as usual for some shipping outfit. However, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) forecasted that with the new technologies, alternative fuels and renewable energy, shipping industry will almost fully be decarbonized by 2035.

The subsisting fact remains that the new technologies, alternative fuels, and renewable energies are still at the experimental and developmental stages without any indication yet about any of them being globally or commercially viable before 2035 or 2050. Even, “China as the second largest global economy and the world largest emitter of fossil fuel CO2 – 10.06 billion metric tons (Blokhin Citation2020)” is projecting 2060 as the target year to halve emissions by 50%. These ambitious emission reduction goals were usually perceived to be technically feasible but politics is seen as the main obstacle. Politics is the main obstacle because they can only be achieved with the collaboration, sponsorship, and commitment of every national government without seeking specific national interest against the common global shipping decarbonization efforts. The politics of global trade and capital accumulation has always posed an obstacle towards transparent and collaborative decarbonization of international shipping and the global economy. It is for this reason that the efforts towards decarbonization of the international shipping industry have always been dotted by divergent views from stakeholders within and outside shipping industry.

Another important note to the un-likeliness of decarbonizing the international shipping industry before 2030 is the fact that if IMO as the sole agency that is regulating shipping industry sets 2023 as year for final revision of its 2018 laid out “Initial Climate Strategy” what is the possibility of eliciting compliance from parties before 2030 without adequate capacity for enforcement? The possibility is doubtable. From every indication, the battle for climate-friendly fuels is on the raise.

Conclusion

It is obvious that the global community is not yet on the same page as to the urgency of decarbonizing the shipping sector as some national governments have failed to align themselves with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal. Even when achieving 2030 green shipping does not appear feasible, there is already dissension between major and minor players in international shipping, like Small Island states in the pacific on the one hand and Brazil, Panama, USA, and China on the other over full decarbonization by 2050 citing concerns about detrimental effects on trade. If this type of disagreement persists longer than expected, it means that 2050 green shipping is not realizable, much less 2030. The implication is increased carbon intensity from shipping vis-à-vis increase in international trade, global warming, and earth temperature.

Deducing from the findings and data from the study, we recommend thus:

Making alternative fuels available at a commercial level and matching technology should be prioritized first before setting CO2 reduction target for shipping industry.

Decarbonization involves technological transition and there are no quick fixes about it. The process has to be in phases.

Governments should undertake the funding of the research and development of alternative fuels that will be commercially viable and the technology to match. The capital demand requires that government should take the lead in this adventure.

Market forces: In the absence of a capable central body to enforce international shipping regulations, the force of the market dynamics – competition guided by government commitment and regulation – will bring the expected decarbonization result through technology innovation in alignment with low carbon alternative fuel.

Win/Win approach: International Maritime Organization (IMO) parties must imbibe win/win disposition for the decarbonization of international shipping. Collaboration, commitment, and transparency remain the approaches that shipping industry need to successfully apply to reduce carbon emission of international shipping and global warming when it is still within control.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Atkinson, G. (2020). Shipping All at Sea When It Comes to Defining Decarbonisation. Retrieved from https://splash247.com/shipping-all-at-sea-when-it-comes-to-defining-decarbonisation2/

- Blokhin, N. (2020). The 5 Countries that Produce the Most Carbon Dioxide (CO2). Retrieved from https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/092915/5-countries-produce-most-carbon-dioxide-co2.asp

- Cames, M., J. Graichen, A. Siemons, and V. Cook (2015). Emission Reduction Targets for International Aviation and Shipping. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/569964/IPOL_STU(2015)569964_EN.pdf

- Cowing, R. (2017). Conspicuously Absent: Shipping Emissions in Climate Change Policy. Retrieved from https://open.bu.edu/bitstream/handle/2144/22742/Pardee-IIB-034-Mar-2017.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- DeSombre, E. 2006. Flagging Standards: Globalization and Environmental, Safety, and Labor Regulations at Sea. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Det Norske Veritas (2021). Decarbonization in Shipping. Det Norske Veritas Group. https://www.dnv.com/maritime/insights/topics/decarbonization-in-shipping/index.html

- Fountain, H., B. Migliozzi, and N. Popovich (2021). Where 2020’s Record Heat Was Felt the Most. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/01/14/climate/hottest-year-2020-global-map.html?smid=em-share

- Gallucci, M. (2017). Uncharted Territory: The Shipping Industry Needs to Deliver Cleaner Cargo Ships, or We’re All Sunk. Retrieved from https://grist.org/article/shipping-industry-destroying-climate-progress-were-all-to-blame/.

- Gerretsen, I. (2020). As UN Action on Ship Emissions Falls Short, Attention Turns to Regions. Retrieved from https://www.climatechangenews.com/2020/11/26/un-action-ship-emissions-falls-short-attention-turns-regions/

- Gomersall, I. (2021). Decarbonisation of Shipping: Taxes, Levies, Investment. Seatrade. https://www.seatrade-maritime.com/environmental/decarbonisation-shipping-taxes-levies-investment?

- Green, J. F. (2018). Why Do We Need New Rules on Shipping Emissions? Well, 90 Percent of Global Trade Depends on Ships. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/04/17/why-do-we-need-new-rules-on-shipping-emissions-well-90-of-global-trade-depends-on-ships/

- Guterres, A. (2020). Antonio Guterres Called for Urgent #climateaction. Retrieved from @antonioguterres.

- Harvey, F. 20 April 2021. Carbon Emissions to Soar in 2021 by Second Highest Rate in History. ThGuardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/apr/20/carbon-emissions-to-soar-in-2021-by-second-highest-rate-in-history

- International Maritime Organization (2020). IMO Working Group Agrees Further Measures to Cut Ship Emissions. Retrieved fromhttps://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/36-ISWG-GHG-7.aspx

- International Transport Forum. 2017. ITF Transport Outlook 2017. Paris: OECD Publishing. 10.1787/9789282108000-en Retrieved from

- Langelaan, J. (2019). 6 Ways to Make Shipping Emission Free. Retrieved from https://ecoclipper.org/News/6-ways-to-make-shipping-emission-free/

- Majuro, M. G. (2017). The Tax-free Shipping Company that Took Control of a Country’s UN Mission. Retrieved from https://www.climatechangenews.com/2017/07/06/tax-free-shipping-company-took-control-countrys-un-mission/

- McGrath, M. (2021, April 1). Climate Change: Net Zero Targets are ‘Pie in the Sky’;. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment–56596200

- McSweeney, R., and A. Tandon (2020). Coronavirus Causes ‘Record Fall’ in Fossil-fuel Emissions in 2020. Retrieved from https://www.carbonbrief.org/global-carbon-project-coronavirus-causes-record-fall-in-fossil-fuel-emissions-in-2020

- News, H. S. (2020). Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Shipping. Retrieved fromhttps://www.hellenicshippingnews.com/greenhouse-gas-emissions-in-shipping/

- News, H. S. (2021). Is LNG’s Role in Shipping’s Decarbonization Limited? Retrieved from https://www.hellenicshippingnews.com/is-lngs-role-in-shippings-decarbonization-limited/

- Organization, I. M. (2019). Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Ships. Retrieved from https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Pages/Reducing-greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-ships.aspx

- Parker, B. (2020). IMO Charting Passage Plan for Reducing Shipping’s ‘Carbon Intensity. Retrieved from https://gcaptain.com/imo-plan-reducing-greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-ships/November6,2020

- Pavlenko, N., B. Comer, Y. Zhou, N. Clark, and D. Rutherford (2020, January 28). The Climate Implications of Using LNG as a Marine Fuel. International Council on Climate Transition. https://theicct.org/publications/climate-impacts-LNG-marine-fuel-2020#:

- Schlanger, Z. (2018). If Shipping Were a Country, It Would Be the World’s Sixth-biggest Greenhouse Gas Emitter. Retrieved from https://qz.com/1253874/if-shipping-were-a-country-it-would-the-worlds-sixth-biggest-greenhouse-gas-emitter/.

- Taalas, P. (2020a). Flagship UN Study Shows Accelerating Climate Change on Land, Sea and in the Atmosphere. Retrieved from https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/03/1059061.

- Taalas, P. (2020b). Fall in COVID-linked Carbon Emissions Won’t Halt Climate Change - UN Weather Agency Chief. Retrieved from https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1062332.

- Timperley, J., (2017) 2017 Shipping Industry Must Take Urgent Action to Meet Paris Goals. Retrived from https://www.carbonbrief.org/shipping-industry-must-take-urgent-action-to-meet-paris-climate-goals