ABSTRACT

International shipping is critical to facilitating approximately 80–90% of global trade. However, shipping accounts for a significant portion of GHG emissions, accounting for approximately 3% of total emissions. Recognising the environmental impact, Malaysia has implemented policies set by the IMO aimed at cutting GHG emissions from ships by half by 2050. By drawing analogies to the United Kingdom, the paper provides an overview of Malaysia’s current trajectory on decarbonisation pathways. Despite the numerous technical and structural challenges associated with decarbonising the shipping industry, the establishment of a strong policy framework and the implementation of a comprehensive action plan could help to meet its targets by 2050. Finally, significant paradigm shifts in technology, regulatory, and legal frameworks, as well as financial incentives, were required to accelerate Malaysia’s progress towards achieving the IMO 2050 goals.

Introduction

The shipping industry is responsible for 80–90% of global trade (Menhat et al., Citation2021; UNCTAD, Citation2023). The enormous shipping volumes and maritime trade, however, have a detrimental effect on both the marine environment and human health. International ocean-going ships currently contribute 3% of the world’s annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, thus contributing significantly to climate change. Although maritime transportation is a more carbon-efficient method of heavy and mass goods transportation when compared to terrestrial or aviation options, maritime GHG emissions are predicted to increase if no action is taken. In business as usual scenarios of doubling world trade, these emissions are projected to increase by up to 250 percent by 2050, placing pressure on the maritime industry to contribute to the significant GHG emission reductions that are necessary (IMO, Citation2020; Joung et al., Citation2020). The global community has placed a stronger emphasis on the decarbonization of the maritime industry through the United Nations agency, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), which comprises 175 member states, including the United Kingdom and Malaysia. The Paris Agreement was reached in 2015 by parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and went into effect in 2016. The main target of the Paris Agreement is to bolster the collective effort to combat climate change by ensuring that the increase in global temperature over the next century remains significantly below 2° C above pre-industrial levels. Additionally, it’s aims to actively strive for further measures to restrict the temperature rise to a maximum of 1.5 ° C (Mitchell et al., Citation2018; Wegener, Citation2020). In keeping with the UNFCCC’s strategy since the Kyoto Protocol in 1992, the Paris Agreement maintained the exclusion of international shipping from its scope for the reason that these fall within the jurisdiction of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) (Psaraftis & Kontovas, Citation2021). The aforementioned goals have encountered scrutiny from national governments, industry groups, and researchers due to their alleged absence of enthusiasm and inability to be consistent with the goal of the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit global warming to 1.5° C.

Malaysia and the United Kingdom are signatories to the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) and hence parties to the IMO’s Initial Strategy on reducing GHG emissions from ships. Thus both countries must demonstrate their commitment to reduce carbon emissions by 50% by 2050. Yet, courses of action for the Malaysian maritime industry to contribute to the aim of lowering GHG emissions by 2050 are still being questioned. There is currently no specialised policy or action plan in place for promising alternatives. Because the shipping sector is not included in the Paris Agreement, climate change mitigation efforts must be multifaceted, and no appropriate initiatives involving significant stakeholders in the shipping sector have been pursued thus far. The objective of this study is to evaluate Malaysia’s current trajectory towards achieving the net zero transition goals set by the IMO by 2050. Furthermore, the primary objective of this study is to provide policymakers and maritime stakeholders in Malaysia and other International Maritime Organisation (IMO) signatory nations with recommendations based on the well- developed maritime decarbonization policies of the United Kingdom. The aforementioned policies, known as Maritime 2050, Clean Maritime Plan, and Transport Decarbonisation Plan, have been in effect since 2019 (UK Parliament, Citation2023). Notably, the United Kingdom has implemented legally enforceable climate targets with the dual purpose of diminishing its domestic GHG emissions and fostering economic growth, thus setting a noteworthy precedent on the international stage (Keller et al., Citation2016; Ritchie & Roser, Citation2020). The United Kingdom’s objective of achieving zero emissions by 2050 is also outlined in The Net Zero Strategy and as a major economy country, the United Kingdom legally pledges to achieve net zero emissions by 2050. Serving as the host of the significant United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP26) climate summit, the United Kingdom is at the forefront of global endeavours and establishing a benchmark for other nations to emulate (UK Department for Business Energy & Industrial Strategy, Citation2021). The Net Zero Strategy delineates explicit policies and initiatives aimed at achieving the United Kingdom’s carbon budget, while concurrently presenting a vision for an economy devoid of carbon emissions by the year 2050.The implementation of various domestic policies, in conjunction with a strategic approach, reflects an acknowledgment of the necessity to emphasise the possibility of transitioning towards shipping practices in the United Kingdom that result in zero emissions. This is achieved through the mitigation of GHG emissions originating from the shipping industry, alongside the promotion of sustainable maritime activities.

Legal frameworks governing GHG emissions in the maritime industry

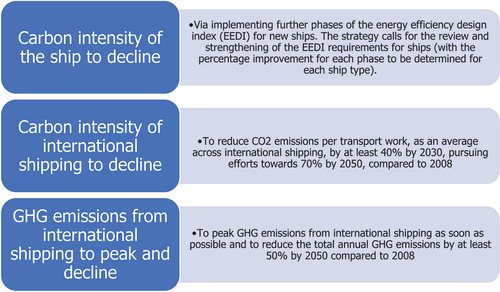

The IMO, as the regulating authority, is committed to decreasing GHG emissions from international shipping. The 2018 Initial GHG Strategy of the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) is the sole globally accepted target for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from international shipping (Marine Environmental Protection Committee, Citation2018). It is worth noting that the Paris Agreement does not clearly address the problem of these emissions. The primary objective of the initial strategy is to bolster the IMO’s role in global endeavours by effectively tackling GHG emissions originating from international maritime transportation. International initiatives aimed at mitigating GHG emissions encompass the Paris Agreement, which outlines specific objectives, and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The IMO’s Initial GHG Strategy has three interlinked ambitions: a reduction in the carbon intensity of international shipping by at least 40 percent by 2030 compared to 2008; pursuing efforts to achieve a 70 percent reduction by 2050 compared to 2008; and reducing the total annual GHG emissions from international shipping by at least 50 percent by 2050(Chen et al., Citation2019; Serra & Fancello, Citation2020) as described in .

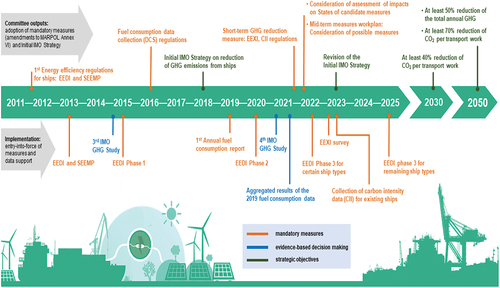

Figure 1. IMO’s work to cut GHG emissions from ships (International Maritime Organization, Citation2022).

The IMO’s Initial GHG Strategy also specifies levels of ambition for the international shipping industry, recognising that technical innovation and worldwide adoption of alternative fuels and energy sources for international shipping will be critical to meeting the overall aim. To meet the levels of ambition set out in GHG Strategy, it is expected that alternative zero-carbon and low-carbon fuels will account for more than 60% of CO2 reduction efforts by 2050. depicts the levels of ambition that guide the Initial Strategy. Earlier, the IMO had approved the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI), the most comprehensive piece of regulation relevant to maritime GHG reduction (Psaraftis, Citation2019). According to the Fourth IMO GHG Study published in 2020, shipping’s GHG emissions climbed by 9.6% from 2012 to 2018, with methane emissions increasing by 150%. IMO via the Marine Environment Protection Committee later approved the Initial Strategy on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships as a result of these escalating emissions. Strict objectives have also been set to considerably reduce NOx and SOx emissions that are linked to air quality (IMO, Citation2019). Updated emission estimates, emission reduction solutions for international shipping, and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports should all be included in future reviews.

Figure 2. Targets of the IMO’s Initial Strategy on the Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships.

During the Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC 80) meeting, the Member States of the IMO approved the 2023 IMO Strategy on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships, which includes more ambitious targets to address harmful emissions. The updated IMO GHG Strategy incorporates a strengthened collective aspiration to achieve a state of equilibrium in GHG emissions from global maritime transportation by approximately 2050. It also entails a pledge to facilitate the adoption of alternative GHG fuels that have zero or minimal emissions by the year 2030. Additionally, the strategy outlines provisional milestones for the years 2030 and 2040. Levels of ambition directing the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy are as follows (IMO, Citation2023):

carbon intensity of ships to decline through further improvement of the energy efficiency for new ships;

carbon intensity of international shipping to decline- to reduce CO2 emissions per transport work, as an average across international shipping, by at least 40% by 2030, compared to 2008;

uptake of zero or near-zero GHG emission technologies, fuels and/or energy sources to increase- uptake of zero or near-zero GHG emission technologies, fuels and/or energy sources to represent at least 5%, striving for 10%, of the energy used by international shipping by 2030; and

GHG emissions from international shipping to reach net zero- to peak GHG emissions from international shipping as soon as possible and to reach net-zero GHG emissions by or around, i.e., close to 2050, taking into account different national circumstances, whilst pursuing efforts towards phasing them out as called for in the Vision consistent with the long-term temperature goal set out in Article 2 of the Paris Agreement.

In light of global efforts towards decarbonization, the shipping sector is actively acknowledging its role in contributing to a more environmentally sustainable future. The pursuit of optimal alternative fuel alternatives and technologies has commenced. However, the utilisation of existing energy sources for the production of zero-emission fuels necessitates prudent usage and requires considerations and collaboration that extend beyond the maritime sector. One could argue that in order to effectively address the primary difficulty of achieving carbon-neutral fuel availability, the establishment of supply chains necessitates the formation of cross-industry coalitions. According to DNV (Citation2022), the best future energy sources include LNG/LPG, biofuels, electrification, methanol, ammonia, hydrogen, wind and solar power, and nuclear power. The utilisation of fuel cells in tandem with alternative fuels, such as hydrogen, has the potential to substantially diminish and potentially eradicate pollution and noise, hence enhancing energy efficiency. Hydrogen is regarded as the most basic and least massive chemical element and due to a number of distinct characteristics, it is widely acknowledged as a highly promising alternative energy source for the decarbonization of transportation in the future (Wang & Wright, Citation2021). When hydrogen is utilised as a fuel source, the resulting by-products consist solely of water and a negligible quantity of nitrogen oxides (NOx). Furthermore, hydrogen has the potential to be generated from a diverse range of sustainable sources, encompassing biomass, nuclear energy, and non-biomass renewable sources like wind and solar photovoltaics (PV).

What the United Kingdom does

The significance of addressing climate change, particularly within the transport sector, has been a subject of considerable emphasis by the government of the United Kingdom. Based on Department for Business, Energy & Industria(Citation2019), the United Kingdom has achieved a significant milestone by enacting legislation that aims to cease its role in exacerbating global warming by the year 2050, making it the first large economy to do so. The new target mandates the United Kingdom to achieve a state where all GHG emissions are balanced by removals or reductions, effectively reaching net zero emissions by the year 2050. This is a significant shift from the prior objective of reducing emissions by a minimum of 80% from 1990 levels. As per the remarks made by Chris Skidmore, the former Energy and Clean Growth Minister of the United Kingdom, as published by Twidale (Citation2019), it is asserted that the United Kingdom played a crucial part in instigating the Industrial Revolution, an era marked by substantial global economic growth. Skidmore further emphasises that the United Kingdom has demonstrated its worldwide influence by enacting legislation, placing itself as the first among the main G7 nations (seven of the world’s advanced economies, including Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, as well as the European Union) to effectively pass innovative statutes with the objective of reducing emissions and reaching a state of net zero by 2050.

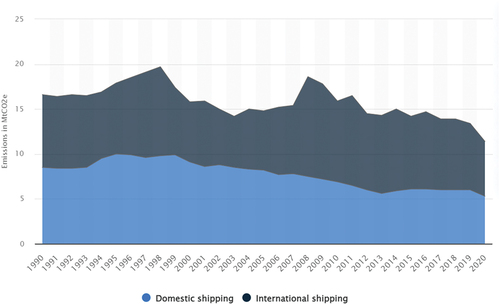

The concept of net zero entails achieving a state where emissions are effectively counterbalanced by initiatives aimed at compensating for an equivalent quantity of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. These mitigation measures may include activities such as afforestation or the implementation of technologies like carbon capture and storage. According to Ben Murray, the Chief Executive Officer of Maritime United Kingdom, the maritime industry holds significant importance in the British economy and has the potential to contribute significantly to its growth (Staines, Citation2023). In his discourse, Murray further emphasised that innovative and sustainable practices are of paramount importance in maintaining the United Kingdom’s prominent position in the maritime industry, encompassing both its competitive edge and commitment to sustainability. The shipping sector is currently witnessing a notable rise in growth and momentum. Through ongoing collaboration and unwavering dedication, the United Kingdom has the potential to forge an even more promising future for the maritime industry. Previously, the United Kingdom government updated the Climate Change Act in 2019, committing the United Kingdom to achieving net zero GHG emissions across their economy, including the domestic maritime industry, by 2050. Based on Tiseo (Citation2023)‘s findings, it can be observed that domestic shipping emissions in the United Kingdom experienced a notable reduction of over 37% during the period spanning from 1990 to 2020.

Similarly, foreign shipping emissions within United Kingdom waters witnessed a significant fall of more than 24%. According to a study conducted by the UK Government Department of Transport (Citation2023), it is hypothesised that the decrease in emissions might be attributed to the growing adoption of alternative fuels such as Hydrogen, ammonia, and liquefied natural gas (LNG). Additionally, the findings of the study have highlighted the domestic ferry business as a subsector that has substantial potential for expeditious decarbonisation. The main reason for this trend may be attributed to the fact that the domestic ferry business exhibits a higher level of emissions in proportion to the number of vessels operating within this specific subsector. The potential for decarbonization in the context of leisure boats on inland waterways has been recognised. These vessels typically engage in shorter excursions at lower speeds and demand less electricity for their operation. Consequently, there is a possibility of retrofitting them with battery propulsion systems. illustrates GHG emissions from international and domestic shipping in the United Kingdom. According to the data presented in the , it can be observed that domestic shipping emissions accounted for approximately 5.3 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e) in the year 2020. On the other hand, foreign shipping emissions were estimated to be around 6.1 MtCO2e.

Figure 3. Greenhouse gas emissions from international and domestic shipping in the United Kingdom.

Since 2008, the annual emissions from international shipping have exceeded those from domestic shipping in the United Kingdom. In order to effectively contribute to the United Kingdom’s goal of achieving net zero GHG emissions, it will be imperative to swiftly implement substantial reductions in emissions from this particular industry. The Maritime 2050 (Citation2019), the Clean Maritime Plan (Chen et al., Citation2019) and Transport Decarbonisation Plan (Citation2021b) published by the United Kingdom Department for Transport articulate the country’s aspiration to assume a prominent position in the process of decarbonizing the shipping industry. This effort is driven by the recognition of the significant societal and economic advantages associated with such a transition.

Maritime 2050

The United Kingdom Department for Transport (Citation2019) recognises the potential of decarbonizing the maritime industry as a means of rejuvenating ports and coastal communities. The enhancement of the United Kingdom’s competitive edge will be facilitated by its attainment of global leadership in emerging technologies. By implementing decarbonization measures in its maritime sector, United Kingdom have the opportunity to strategically utilise its investments in order to increase their market presence in the worldwide clean maritime technology industry. Hence, the United Kingdom Government released the Maritime 2050 strategy in January 2019, which outlines its aspirations for the British maritime industry (Department for Transport, Citation2019). The United Kingdom Government outlined its vision for the future of zero emission shipping in Maritime 2050, stating that by 2050, the prevalence of zero emission ships would be widespread on a global scale. The strategy outlined a comprehensive maritime strategy aimed at positioning the United Kingdom for sustained success over the latter part of the 21st century. The strategy put forward that the United Kingdom is adopting a forward-thinking approach, aiming to facilitate the sustained development and bolstering of the maritime sector through resolute and robust measures. The United Kingdom has actively assumed a leading position in promoting the shift towards zero emission shipping within its territorial waters. Notably, the United Kingdom has outpaced other nations and international benchmarks, demonstrating a notable level of expediency in its efforts. This proactive stance has garnered global recognition, positioning the United Kingdom as an exemplary model in this domain. Consequently, the United Kingdom has effectively acquired a substantial portion of the economic, environmental, and health advantages linked to this transformation. Via Maritime 2050, the United Kingdom has actively pursued the reduction of GHG emissions in the shipping industry, positioning itself as a leading example globally. The country has demonstrated a proactive approach in expediting the shift towards zero-emission shipping within its territorial waters, surpassing the pace set by international standards. Consequently, the United Kingdom has successfully obtained a significant proportion of the economic, environmental, and health advantages associated with this transition (Hoyland & Wood, Citation2021). Furthermore, the strategy also acknowledges the potential for substantial economic advantages for those who are proactive in taking initial steps and embracing new technologies or practices (Department for Transport, Citation2021a). Recommendations on priority areas of focus are intended to contribute to the next iteration of the United Kingdom government’s Clean Maritime Plan:

Specific sections of the United Kingdom maritime sector such as ferries, offshore service vessels and the offshore wind market present an opportunity for priority action and targeted measures.

New sources of capital will be required to fund the industry’s decarbonisation transition.

Institutional investors could be a viable source of funding with the appropriate government support.

Specific funding mechanisms (illustrated through case studies) can help to overcome the barriers to investment.

Clean maritime plan

The Clean Maritime Plan published in July 2019 serves as the environmental roadmap for Maritime 2050 and functions as the United Kingdom’s comprehensive strategy for addressing emissions in the shipping industry. With the Clean Maritime Plan, the United Kingdom becomes one of the first nations to publish its National Action Plan following the adoption of the IMO Initial Strategy. The Clean Maritime Plan outlines the United Kingdom ‘s transition to a future of zero-emission shipping, with the 2050 zero-emission goal at its core. The Clean Maritime Plan lays forth a number of goals in particular to achieve the 2050 objective. First, the United Kingdom government anticipates that all vessels operating in United Kingdom waters will maximize the use of energy efficiency options. All new vessels procured for usage in United Kingdom waters will be equipped with zero-emission propulsion (The UK Government Department of Transport, Citation2019). The United Kingdom is now constructing clean maritime clusters that prioritise innovation and infrastructure related to zero-emission propulsion technology. This includes the establishment of facilities for the storage and supply of low- or zero-emission fuel. And by 2035, the United Kingdom government expects that the United Kingdom will have built a number of clean maritime clusters. These combine infrastructure and innovation for the use of zero-emission propulsion technologies. Low- or zero-emission marine fuel bunkering options are readily available across the United Kingdom, and the United Kingdom Ship Register is known as a global leader in clean shipping. Based on the statement provided by the United Kingdom Department for Transport (Citation2023), it is anticipated that within a span of two years, United Kingdom waterways would see the operation of ferries, cruises, and cargo ships that produce zero emissions. This development is expected to generate a significant number of employment opportunities, as a result of the government’s allocation of £77 million towards the advancement of clean maritime technology. This statement points out that the United Kingdom has the potential to become a prominent hub for a zero-emission marine sector, characterised by its exceptional export industry, advanced research and development endeavours, and its status as a global epicentre for investment, insurance, and legal services pertaining to the expansion of clean maritime practices.

In April 2021, the United Kingdom Government announced the inclusion of international shipping and aviation emissions in the sixth carbon budget (UK Parliament, Citation2022). The Sixth Carbon Budget is the legally mandated cap on United Kingdom net GHG emissions for the years 2033 to 2037. It calls for a 78% drop in United Kingdom emissions from 2019 to 2035 as compared to 1990. With a trajectory that is compatible with the Paris Agreement, this will be a commitment that sets a global standard and will firmly establish the United Kingdom on the path to Net Zero by 2050 at the latest (The Climate Change Committee, Citation2020). The Climate Change Committee’s report (Citation2020) has recognised achieving a 33% adoption rate of zero-carbon fuels in domestic ships by 2035 as an important milestone. The report also recommends implementing legislative measures to encourage innovation, provide assistance for the demonstration of zero carbon technologies, and provide incentives for the widespread adoption of these technologies. Proposals to cut United Kingdom marine emissions even more include phasing out the sale of new non-zero emission domestic shipping vessels. Improvements in vessel efficiency, including the use of electricity and zero-carbon fuels, primarily ammonia generated from low-carbon hydrogen to replace fossil fuels, are mitigation approaches that have been taken into account. Consequently, starting in 2033, the United Kingdom will incorporate its share of global shipping emissions into its target of achieving net zero GHG emissions by 2050. The Plan clearly reflects the United Kingdom’s ambition and commitment to addressing critical issue at a turning point in the maritime sector’s development. In addition to the aforementioned measures, various other domestic policy initiatives have been implemented subsequent to the year (Citation2019; Department for Transport, Citation2021b):

Transport decarbonisation plan- The objective of the transport decarbonisation plan is to effectively address the carbon budgets and achieve a net zero carbon emissions target in all modes of transport, including the maritime sector. The proposed strategy outlines various commitments towards achieving a carbon-neutral state. These include conducting consultations on the feasibility of connecting more ships to a decarbonized power grid, investigating methods to gradually eliminate emissions from vessels, and exploring opportunities to leverage the United Kingdom’s expertise in the maritime industry to foster the development of environmentally friendly technologies and shipbuilding practices.

Clean Maritime Demonstration Competition - £23 million provided to 55 green maritime innovation projects in 2021. Set for a second round in 2022.

Operation Zero – An industry coalition aimed at accelerating the decarbonisation of service vessels in the North Sea offshore wind sector.

Extension of the Renewable Transport Fuels Obligation to include incentives for use of renewable fuels of non-biological origin in domestic vessels, such as ammonia and hydrogen, to be enforced from 1 January 2022.

Consultations on steps to support shore power and a potential phase-out of the sale of new non-zero emissions domestic vessels.

Extension of the CMDC to an ongoing multiyear program.

To review the United Kingdom’s Monitoring, Reporting and Verification system for GHG emissions from international shipping.

Exploring the establishment of a United Kingdom Shipping Office for Reducing Emissions

In order to attain a net zero emissions target, the United Kingdom maritime sector aims to transition towards utilising alternative fuel-powered vessels. These vessels will derive their energy from low or zero emission sources, such as ammonia, hydrogen, or highly efficient batteries (The UK Government Department of Transport, Citation2022). Additionally, the sector plans to integrate ports into the decarbonized energy network and facilitate the supply of future fuels. In addition, it is important to acknowledge the significant contribution that ports and harbours can make in decarbonizing their own operations. The United Kingdom Government has expressed a strong commitment to achieving net zero emissions for the domestic maritime sector in the country at the earliest opportunity. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that the goal of net zero emissions may be attained prior to 2050. Modelling conducted for the Department for Transport indicates that such a transition could potentially be realised in the 2040s (Baresic et al., Citation2022).

Options for Malaysia

The route to reducing GHG emissions by 2050 is a complex task that will necessitate extensive planning and concerted efforts from Malaysia. Basically, the 12th Malaysia Plan (12 MP) outlines Malaysia’s path to net zero emissions (Prime Minister’s Department, Citation2021).The 12 MP initiatives included efforts to achieve a low-carbon, climate-resilient economy based on clean, green, and resilient development. This involves achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 and phasing out coal-fired energy generation. Policymakers, business, civil society, academia, local communities, and other key stakeholders are actively participating in climate change transformation. Measures on the green agenda in Budget 2021 were aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the process will be repeated in Budget 2022, which will focus on recovery, resilience, and reform (Ministry of Finance Malaysia, Citation2021). Malaysia has acknowledged climate change as a regional priority. Enhancing Malaysia’s circular economy, placing greater focus on sustainability, and transitioning towards sustainable urban development constitute significant objectives. Moreover, it is imperative for the government to establish a pricing mechanism for carbon emissions in the country and reduce dependence on hydrocarbon resources, all the while ensuring the preservation of a minimum of 50% forest coverage. It has become imperative to look into alternative long-term decarbonisation approaches to technology through suitable methodologies, such as modelling frameworks capable of projecting the trajectory beyond 2050, in order to facilitate the transition. Consequently, it is imperative for Malaysia to establish robust collaborations with regional and international counterparts to bolster domestic capacity development, begin enduring climate-related investments, and facilitate the exchange of information and technology.

However, the current efforts and approaches aimed at enhancing Malaysia’s involvement in global and regional climate initiatives do not adequately align with the maritime industry’s commitment to the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) objective. The challenges and impediments to decarbonising the maritime sector in Malaysia include the absence of a suitable policy and legislative framework, inadequate supporting infrastructure, limited government funds and incentives, a lack of visionary leadership, the maritime sector’s failure to perceive decarbonisation as a potential business opportunity, and a lack of willingness and interest among local stakeholders. The primary driver of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reductions is the replacement of conventional fossil fuels with synthetic fuels produced from renewable energy sources. The potential for emissions reduction through further enhancements in vessel energy efficiency is limited in comparison to the substantial reductions required on a broader scale. Delaying the commencement of decarbonization efforts in the maritime industry, even if it is extended until the year 2030, leads to a more chaotic and disorderly technological shift, along with an increased financial burden associated with the total conversion process. The achievement of decarbonization in the maritime transportation industry is a highly ambitious objective. Therefore, it is imperative for stakeholders within the maritime sector to shoulder accountability in ensuring the implementation of measures that effectively reduce operational emissions to zero, aligning with global aspirations in this regard.

In line with the United Kingdom’s approach, it is recommended that Malaysia initiates legislative measures pertaining to GHG emissions. This can be achieved by developing robust policy commitments aimed at supporting the marine industry in its efforts to align with the IMO’s objective for 2050. The achievement of this objective necessitates the alignment of commercial forces, advancements in technology, and the overall regulatory policy landscape. Both the government and the private sector should collaborate to facilitate the transition towards a new fuel composition. Additional policy measures, such as the implementation of carbon pricing mechanisms and the utilisation of command-and-control approaches, have the potential to stimulate behavioural changes and mutually reinforce each other. The implementation of a carbon pricing mechanism facilitates the transfer of accountability for the adverse effects resulting from GHG emissions to the responsible parties who possess the capacity to mitigate such impacts. The implementation of a carbon price mechanism serves as an economic incentive for emitters, affording them the opportunity to modify their practices and curtail their emissions voluntarily. Alternatively, emitters may choose to persist in their emission-intensive activities but will be subject to financial penalties proportional to their emissions. This approach stands in contrast to prescriptive measures that dictate certain emission reduction targets, methods, and locations (Best & Zhang, Citation2020; Skovgaard et al., Citation2019). The provision of timely regulatory clarification has the potential to facilitate more investment in scalable zero-emission fuels and the necessary infrastructure, so potentially mitigating the adverse effects on the shipping industry. In order to facilitate the shift towards emission-free shipping, it is recommended that the government enact non-tax-based incentives and promote the adoption of low-carbon fuels within the maritime sector. To garner endorsement from stakeholders and communities within the maritime sector, it is imperative for the government to allocate initial funding for an initiative aimed at achieving zero-emission objectives within shipping clusters. There is a pressing need for grant money to support early-stage research endeavours focused on ship technology and fuel for the purpose of decarbonizing the shipping industry. This financing is particularly crucial in key domains such logistics and digitalization, hydrodynamics, equipment, energy, and carbon capture and storage technologies. Renewable energy-derived zero-carbon fuels, including solar, wind, hydropower, and geothermal energy, are widely regarded as the most viable solution for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. In the context of the maritime business, two distinct types of fuels are accessible. Initially referred to as E-Hydrogen or E-Ammonia, and afterwards as Hydrocarbon. E-fuels, such as E-Diesel, E-LNG, and E-Methanol, are alternative fuels that have gained significant attention in recent years (Lindstad et al., Citation2021).

The achievement of maritime decarbonization by 2050 would be facilitated by the sustained contributions of stakeholders, as no single industry possesses the capacity to decarbonize in standalone. Currently, the bunker market is predominantly controlled by several types of fuel oil, encompassing heavy fuel oil, marine diesel oil, marine gas oil, very low sulphur fuel oil, and liquefied natural gas (Nagrale, Citation2023). In order to achieve the target of 40% carbon-neutral fuel utilisation in the fuel composition by the year 2050, as per the existing requirements set by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), it is imperative to witness a significant rise in the adoption of carbon-neutral fuels by the mid-2030s. Consequently, it is imperative for all sectors within the marine industry, specifically shipowners, to engage in collaborative efforts aimed at making optimal decisions and allocating resources in a manner that maximises their potential to mitigate emissions. Collaboration with prominent oil corporations, such as Petroliam Nasional Berhad (Petronas), which possesses a substantial fleet dedicated to maritime logistics, is crucial in attaining carbon neutrality within their upstream operations.

Furthermore, it is crucial for Malaysia to carefully determine suitable strategies to be enacted, taking into account the repercussions on nations around the world and acknowledging the crucial importance of global maritime transportation in facilitating the ongoing growth of global trade. There exists an urgent imperative to transition towards innovative technologies that can enable a sustainable and effective energy and distribution infrastructure. The primary determinant impacting the costs related to energy transfer to a vessel is the current price of crude oil in the present-day global oil market. The oil market is distinguished by its advanced stage of development and the existence of firmly developed infrastructure. The facilitation of future fuel uptake, particularly within the port sector, will be significantly influenced by the creation of partnerships with key energy and fuel providers. The aforementioned cooperation will function as energy hubs, providing the essential infrastructure for the storage and refuelling of vessels using alternative fuels, in addition to supplying onshore electricity. Therefore, it is crucial for individuals in Malaysia to diligently monitor the advancements of the market economy and strategically position the country to efficiently capitalise on upcoming prospects.

Conclusion and way forward

Malaysia possessed ample opportunity to make a significant contribution towards climate change mitigation through the decarbonization of its maritime industry, capitalising on its substantial role as a coastal state. This study emphasises the obstacles and complexities faced by the industry in establishing a clear trajectory towards GHG reductions in the maritime sector by 2050, as mandated by the IMO. The paper elucidates that the main obstacles encompass technological constraints and a lack of legislative and regulatory frameworks that facilitate the execution of decarbonization initiatives. For Malaysia to comply with the (IMO’s, Citation2023) GHG Strategy, completely emission-free fuels would need to replace fossil fuels as the predominant energy source. However, a substantial competitiveness disparity exists between conventional fossil fuels and alternative zero-emission options, which must be addressed. The study’s findings suggest a potential course of action by recommending an embrace of the legislative procedures adopted by the United Kingdom in addressing GHG emissions. This entails establishing substantial policy commitments to bolster the advancement of Malaysia’s maritime industry in aligning with the IMO objective for the year 2050. The attainment of zero GHG emissions in Malaysia’s maritime industry necessitates a concerted effort including significant time, resources, and collaboration among key stakeholders. The potential for achieving a substantial decrease in GHG emissions can be realised through a combination of technological improvements and the regulatory policy. Furthermore, the establishment of legislative precedents for decarbonization can be facilitated by the identification and analysis of successful collaborative endeavours among stakeholders in the maritime industry is anticipated to yield synergistic effects and novel approaches. In addition, by reducing the amount of GHG emissions per unit of energy consumed, it is plausible that there could be a resultant decline in the demand for international shipping. As a result, the utilisation of renewable energy sources emits a lower quantity of GHG in comparison to alternative energy sources, making it imperative for achieving long-term GHG reduction. In addition to the current state of affairs, Malaysia possesses a multitude of prospects in the realm of establishing renewable energy production infrastructure that effectively harnesses renewable energy sources, all the while satisfying the substantial energy requirements of the maritime industry.

Financial support

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s)

References

- Baresic, D., Rojon, I., Shaw, A., & Rehmatulla, N. (2022 Closing the Gap: An Overview of the Policy Options to Close the Competitiveness Gap and Enable an Equitable Zero-Emission Fuel Transition in Shipping (London: UMAS).

- Best, R., & Zhang, Q. Y. (2020). What explains carbon-pricing variation between countries? Energy Policy, 143, 111541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111541

- Chen, J., Fei, Y., & Wan, Z. (2019). The relationship between the development of global maritime fleets and GHG emission from shipping. Journal of Environmental Management, 242(March), 31–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.03.136

- The Climate Change Committee. (2020). Sixth Carbon Budget – The path to Net Zero (United Kingdom: Climate Change Committee,).

- Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2019). (United Kingdom).

- Department for Transport. (2019). Maritime 2050—Navigating the Future.

- Department for Transport. (2021a). Decarbonising Transport—A Better, Greener Britain.

- Department for Transport. (2021b). Transport decarbonisation plan (Department for Transport).

- Department for Transport. (2023). Major milestone in UK’s race to net zero maritime with £77 million boost. Maritime and the Environment, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/major-milestone-in-uks-race-to-net-zero-maritime-with-77-million-boost

- DNV. (2022). Maritime Forecast to 2050 (DNV GL).

- Hoyland, R., & Wood, C. (2021). Decarbonisation and shipping: The UK’s position on greenhouse gas emissions from shipping. Hill Dickinson.

- IMO. (2019). The 2020 global sulphur limit: FAQ (United Kingdom: International Maritime Organization)

- IMO. (2020). Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships. Fourth IMO GHG Study 2020 - Full report. note by the secretariat. International Maritime Organization, 53(9). https://imoarcticsummit.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/MEPC-75-7-15-Fourth-IMO-GHG-Study-2020-Final-report-Secretariat.pdf

- IMO. (2023). Revised GHG reduction strategy for global shipping adopted (United Kingdom: International Maritime Organization).

- International Maritime Organization. (2018). UN Body Adopts Climate Change Strategy for Shipping. https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/06GHGinitialstrategy.aspx

- International Maritime Organization. (2022). Acting to cut emissions from ships. IMO’s Work to Cut GHG Emissions from Ships.

- Joung, T. H., Kang, S. G., Lee, J. K., & Ahn, J. (2020). The IMO initial strategy for reducing greenhouse Gas(GHG) emissions, and its follow-up actions towards 2050. Journal of International Maritime Safety, Environmental Affairs, and Shipping, 4(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/25725084.2019.1707938

- Keller, K., Bolker, B. M., & Bradford, D. F. (2016). The roads to decoupling: 21 countries are reducing carbon emissions while growing GDP. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 48(1), 723–741. https://www.wri.org/insights/roads-decoupling-21-countries-are-reducing-carbon-emissions-while-growing-gdp

- Lindstad, E., Lagemann, B., Rialland, A., Gamlem, G. M., & Valland, A. (2021). Reduction of maritime GHG emissions and the potential role of E-fuels. Transportation Research Part D: Transport & Environment, 101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2021.103075

- Marine Environmental Protection Committee. (2018). MEPC.304(72) - Initial IMO strategy on reduction of GHG emissions from ships (United Kingdom: International Maritime Organization).

- Menhat, M., Mohd Zaideen, I. M., Yusuf, Y., Salleh, N. H. M., Zamri, M. A., & Jeevan, J. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic: A review on maritime sectors in Malaysia. Ocean and Coastal Management, 209, 105638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105638

- Ministry of Finance Malaysia. (2021). 2022 Budget Speech. https://budget.mof.gov.my/pdf/2022/ucapan/bs22.pdf

- Mitchell, D., Allen, M. R., Hall, J. W., Muller, B., Rajamani, L., & Le Quéré, C. (2018). The myriad challenges of the Paris Agreement. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 376(2119). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2018.0066

- Nagrale, P. (2023). Bunker fuel market size, share industry report 2030.

- Prime Minister’s Department. (2021). Twelfth Malaysia Plan. In 12th Malaysian Plan. https://rmke12.epu.gov.my/bm

- Psaraftis, H. N. (2019). Decarbonization of maritime transport: To be or not to be? Maritime Economics & Logistics, 21(3), 353–371. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41278-018-0098-8

- Psaraftis, H. N., & Kontovas, C. A. (2021). Decarbonization of maritime transport: Is there light at the end of the tunnel? Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010237

- Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2020). CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions - Our World in Data. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-other-greenhouse-gas-emissions?source=post_page—–47fa6c394991———————-

- Serra, P., & Fancello, G. (2020). Towards the IMO’s GHG goals: A critical overview of the perspectives and challenges of the main options for decarbonizing international shipping. Sustainability, 12(8), 3220. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(8. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083220

- Skovgaard, J., Ferrari, S. S., & Knaggård, Å. (2019). Mapping and clustering the adoption of carbon pricing policies: What polities price carbon and why? Climate Policy, 19(9), 1173–1185. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1641460

- Staines, R. (2023). Maritime UK award winners announced in hull. Maritime UK.

- Tiseo, I. (2023). Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Shipping in the UK 1990-2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1301397/greenhouse-gas-emissions-international-domestic-shipping-uk/

- Twidale, S. (2019). Britain’s new net zero emissions target becomes law. Reuters.

- UK Department for Business Energy & Industrial Strategy. (2021). UK’s path to net zero set out in landmark strategy.

- The UK Government Department of Transport. (2019). Clean Maritime Plan. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/815664/clean-maritime-plan.pdf

- The UK Government Department of Transport. (2022). UK Domestic Maritime Decarbonisation Consultation: Plotting the Course to Zero.

- The UK Government Department of Transport. (2023). Domestic maritime decarbonisation: The course to net zero emissions.

- UK Parliament. (2022). International Shipping and Emissions. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/POST-PN-0665/POST-PN-0665.pdf

- UK Parliament. (2023). UK Government’s Maritime 2050 strategy (UK Government).

- UNCTAD. (2023). Review of Maritime Transport 2022 (United Nations).

- Wang, Y., & Wright, L. A. (2021). A Comparative Review of Alternative Fuels for the Maritime Sector: Economic, Technology, and Policy Challenges for Clean Energy Implementation. World, 2(4), 456–481. https://doi.org/10.3390/world2040029

- Wegener, L. (2020). Can the Paris agreement help climate change litigation and vice versa? Transnational Environmental Law, 9(1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102519000396