ABSTRACT

An enduring dimension of everyday life in Havana is the city’s architectural and infrastructural precarity. More than half the water supply is lost before it reaches residents, the asphalt on the streets is crumbling, and a building collapses approximately every third day. Such conditions have prompted scholars to conceive of the city as “dystopian” [Coyula, M. 2011. “The Bitter Trinquennium and the Dystopian City: Autopsy of a Utopia.” In Havana Beyond the Ruins: Cultural Mappings After 1989, edited by A. Birkenmaier, and E. K. Whitfield, 31–52. Durham, NC: Duke University Press], a “non-city” [Redruello, L. 2011. “Touring Havana in the Work of Ronaldo Menéndez.” In Havana Beyond the Ruins: Cultural Mappings After 1989, edited by A. Birkenmaier and E. K. Whitfield, 229–245. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.] or a city of “fleeting dreams” [Porter, A. L. 2008. “Fleeting Dreams and Flowing Goods: Citizenship and Consumption in Havana Cuba.” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 31 (1): 134–149], whereby the disrepair of the physical environment is symbolic of the decaying political agency of the local population [Ponte, A. J. 2011. “La Habana: City and Archive.” In Havana Beyond the Ruins: Cultural Mappings After 1989, edited by A. Birkenmaier, and E. K. Whitfield, 249–269]. Yet, residents continue to inhabit the city through practices that are at once creative, spontaneous, and collective. Building on existing discussions of Latin American informality [Fischer, B. 2014. “Introduction.” In Cities From Scratch: Poverty and Informality in Urban Latin America, edited by B. Fischer, B. McCann, and J. Auyero, 1–8. Durham, N.C, London: Duke University Press], I argue that an overlooked dimension of Havana’s everyday life emerges through tacit, communicatory practices made possible through sound and listening. Through both ethnographic writing and audio media production, this multimedia project illustrates a neighborhood response to malfunctioning water delivery infrastructure. This localized episode offers a vivid example of what ethnomusicologist Ana María Ochoa-Gautier refers to as the “aural public sphere” [2012. “Social Transculturation, Epistemologies of Purification and the Aural Public Sphere in Latin America.” In The Sound Studies Reader, edited by J. Sterne, 388–404. London: Routledge.] while giving life to a story of resilience that can resonate in cities across Latin America.

RESUMO

A precariedade arquitetônica e estrutural é uma dimensão presente e duradoura da vida cotidiana em Havana, Cuba. Mais da metade do abastecimento de água é perdida antes de alcançar os residentes, o asfalto nas ruas está desmoronando, e um colapso parcial ou completo dos edifícios ocorre aproximadamente a cada três dias. Estas condições levaram a academia de conceber a cidade como "distópica" (Coyula 2011), como "não-cidade" (Redruello 2011), ou como uma cidade de "sonhos efêmeros" (Porter, 2008), onde a deterioração do ambiente físico simboliza a agência política decadente da população local (Ponte 2002; 2011). No entanto, os moradores continuam a habitar a cidade participando de práticas criativas, espontâneas e, acima de tudo, coletivas. Considerando-se as discussões sobre a informalidade na América Latina (Fischer et al. 2014; Hernandez et al. 2012), este projeto multimídia argumenta que uma dimensão negligenciada da vida urbana informal de Havana é encenada através de práticas comunicativas tácitas, possibilitadas através do som e da escuta. Através da escrita acadêmica e da produção de um áudio documental etnográfico, este projeto comunica uma manifestação típica da vizinhança a uma infra-estrutura deficiente de fornecimento de água. Este episódio localizado oferece um exemplo vívido do que a etnomusicóloga Ana María Ochoa-Gautier refere como “esfera pública auditiva” (2012), ao mesmo tempo em que dá vida a uma história de resiliência urbana que pode ressoar em cidades da América Latina de forma mais ampla.

RESUMEN

La precariedad arquitectónica y estructural es una dimensión presente y durable de la vida cotidiana en la Habana, Cuba. Más de la mitad del suministro de agua se pierde antes de llegar a los residentes, el asfalto de las calles se está derrumbando, y un colapso parcial o completo de edificios sucede cada tercer día aproximadamente. Estas condiciones han motivado a la academia a concebir a la ciudad como “distópica” (Coyula 2011), como “no-ciudad” (Redruello 2011), o como una ciudad de “sueños efímeros” (Porter, 2008), donde el deterioro del ambiente físico simboliza la decadente agencia política de la población local (Ponte 2002; 2011). Sin embargo, los residentes continúan habitando la ciudad al participar en prácticas que son a la vez creativas, espontáneas, y sobre todo, colectivas. Considerando discusiones sobre la informalidad latinoamericana (Fischer et al., 2014; Hernandez et al., 2012), el argumento de este proyecto multimedia es que una dimensión ignorada de la vida informal en la Habana se lleva acabo a través de prácticas tácitas y comunicativas, posibilitadas por el sonido y el acto de escuchar. A través de escritura académica y la producción de un audio documental etnográfico, el presente proyecto comunica la típica respuesta que tiene una vecindad al malfuncionamiento de la infraestructura de distribución del agua. Este episodio localizado ofrece un ejemplo vívido de lo que la etnomusicóloga Ana María Ochoa-Gautier llamó la “esfera pública auditiva” (2012), asimismo da vida a una historia de resilencia urbana que resuena en ciudades a lo largo de América Latina.

KEYWORDS:

PALAVRAS-CHAVE:

PALABRAS CLAVE:

1. Introduction

An enduring and ever-present dimension of everyday life in Havana, Cuba, is the city’s architectural and infrastructural precarity. Aside from newly renovated tourist geographies in parts of Habana Vieja, El Vedado, and municipio Playa, the city is aging, weathered, and in a state of disrepair. Much of its housing stock dates back centuries and has received little in the way of maintenance or restoration. Spaces are overpopulated, sidewalks are uneven, and the asphalt on the streets is quite literally crumbling. More than half the city’s potable water supply is lost before it even reaches residents, so in certain neighborhoods, water delivery is intermittent if not altogether nonexistent. Such conditions have prompted scholars to refer to the city as “dystopian” (Coyula Citation2011), a “non-city” (Redruello Citation2011), a city of “fleeting dreams” (Porter Citation2008), and as altogether “illegible” (Rojas Citation2011). These ideas achieve their most succinct and incisive articulation in the writing of ruinologist Antonio José Ponte (Citation2002, Citation2011), who argues that Havana’s decaying physical environment is symbolic of the decaying political agency of its local population. So long as residents are surrounded by ruin, Ponte maintains, they will be unable to imagine and effect emancipatory change.

Yet somehow, the local population subsists. Through tactical practices and negotiations, residents creatively and collectively mitigate the precarity of Havana’s material conditions. These practices are not the result of collective planning or an official mode of organization. Instead, they are rehearsed informally, and are a product of the communal knowledge needed in order to sobrevivir – to survive. Often conceived of as urban informality or informal urbanism (which amount to the same thing), the practices that propel the everyday life of the city are multiple and evade succinct categorization. “Informal urbanism,” writes architect and urbanist Mehrotra (Citation2010), “is about invention within strong constraints with the purpose of turning odds into a survival strategy” (xiii). Typically, informality is conceived of as ingenuity with material objects or by exchanging resources in response to material scarcity. Often overlooked, however, is that informal life is also enacted through tacit, communicatory practices made possible through sound and listening. Informality, I argue, is quite literally an exercise in communication. What this means in Havana is that the city’s infrastructures must be conceived of not as static objects to be evaluated with the eye, but instead, as social processes to be experienced with the ear.

In this project, I present a multimedia account of Havana’s infrastructural decay and the practices of resilience that it engenders. I do so, first, by locating Havana’s material geography historically and in terms of the scholarly literature on the city. I then position sound and listening as an alternative and unexplored means through which to encounter Havana’s infrastructure and the cultural practices that comprise it. I work through an account of sonic ethnography, a methodological approach based in sound and listening aided by the use of audio media. Sonic ethnography opens up research in (and on) Havana to include sensory experience, which creates new perspectives and generates unexplored encounters with the city and its everyday life. Lastly, rather than develop an account of infrastructure and resilience using words alone, I make use of the audio recordings that I myself captured while living in Havana. Because sound can communicate the richness of lived experience where written words fall short, I produced a corresponding audio documentary using source material generated throughout my time “in the field.” Sonically narrativizing the sounds of malfunctioning infrastructure and those who live amidst it represents an effective (and hopefully, an evocative) way of communicating the creativity, tenacity, and ultimately, the political agency of Havana’s residents in light of the city’s infrastructural precarity.

2. The Origins of Havana’s precarious infrastructures

Although the story of Havana’s built environment extends back several centuries, there is no account of the city’s present-day material conditions that does not in some way include the pivotal role of the Revolutionary government. Cuba’s current government came into power in January of 1959, following the triumph of the 26th of July Movement: a vanguard Revolutionary organization led by Fidel Castro. Under the auspices of national socialism, the incoming regime dissolved the urban-centric model of development that guided much of Cuba’s twentieth century, in turn reversing the economic flows that brought the wealth created by the countryside to – and ultimately, through – the city. “A maximum of ruralism, and a minimum of urbanism” was the maxim that guided state initiatives throughout the first decade of the Revolution, initiating a process of national, social and economic leveling that historian Susan Eckstein has since referred to as Havana’s “debourgeoisement” (Citation1985). Throughout the 1960s and ‘70s, immense ruralization efforts brought social services, health care facilities, and education to previously impoverished rural dwellers. The consequence, as most scholars rightly point out, is that Cuba’s pro-provincial, pro-rural strategy came at the expense of maintaining the island’s largest and most populated city. Havana’s physical geography was left largely unattended, restoration efforts were minimal, and new housing projects were insufficient for a city of its size.

Such conditions worsened exponentially at the onset of the 1990s. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Bloc, a primary source of Cuban political and economic support for over two decades, the island entered one of the most profound economic crises in its history. Termed the “Special Period in a Time of Peace,” much of the 1990s was defined by the scarcity of material goods such as petrol, medicine, and basic necessities. To mitigate the crisis, the socialist government put in place a series of economic and political reforms aimed at remobilizing the otherwise stagnant economy. Notably, such reforms included the rebirth of the island’s once-famed tourist industry and the reintroduction of cuentapropismo, or, private entrepreneurship. However, an unintended and unforeseen consequence of these reforms was that waves of migrants from the island’s interior provinces relocated to the city in search of hard currency. Rural residents either sought employment in Havana’s rapidly growing tourist sector or aspired toward other ways of profiting from the city’s emergent open market. Internal migration from the countryside continued throughout the 1990s and was left unchecked until 1997 when a regulatory law was enacted prohibiting such movement. But by then, it was already too late: Havana’s population had risen to levels that greatly exceeded the physical capacity of the city.

Three decades removed from the onset of the Special Period, debates continue whether or not Cuba has truly recovered from this critical historical moment. The scarcity of basic necessities, pharmaceuticals, and food items are ongoing concerns across the island, and in Havana, these issues are compounded by the city’s overpopulation and its architectural and infrastructural degradation. For instance, the housing stock in Habana Vieja is in such poor condition that, as D. Medina Lasansky (Citation2004) observes, “numerous structures are on the verge of collapse” and “there is a building collapse in the city every third day” (167). A large part of the reason for such devastating consequences is on account of the city’s overpopulation: in the mid-1990s, there were about 80,000 residents living in Habana Vieja, even though it was designed to house only about half that number (Scarpaci, Segre, and Coyula Citation2002, 326).Footnote1 The pressure on the city’s housing stock is mirrored by the state of its infrastructure, which has received little maintenance or restoration since well before the triumph of the Revolution in 1959. Notably, Havana’s water delivery network is in such a state of disrepair that 60% of potable water is lost before it even reaches homes (Cocq Citation2006). These conditions, in part, comprise what Cuban studies scholar Juan Clark refers to as Havana’s “urban crisis” (Citation1998), which has scarcely improved, and in light of the city’s continued aging, it has worsened since the height of the Special Period in the mid-1990s.

3. Urban informality in Havana

The decline of Havana’s social, material, and economic conditions during the Special Period conditioned a newfound approach to everyday life in the city. Where there was once abundance there was now absence; where there was once institutional support there was now disorganization and uncertainty. Havana’s increasingly precarious reality gave rise to a lifestyle characterized by struggle and resilience. Inventar, or, “to invent,” is the term residents use to describe the enactment of ingenuity on account of the city’s adverse economic and material conditions. A definitive attribute of modernity across Latin America and the Caribbean, inventar in Havana, or urban informality as it is referred to more broadly, is an enactment of creativity and spontaneity in the face of struggle. Rarely an individual pursuit, urban informality instead is a collective endeavor. As historian Brodwyn Fischer (Citation2014) observes, “residents usually create intense networks of exchange, commerce, and small-time credit, and varying degrees of violence and exploitation can coexist with expressions of community solidarity” (2). Informality, no matter in which context, seldom exists in isolation: it is facilitated by and through networks of support and communities of interest, and it emerges by leveraging the resources of friends, family, neighbors, and/or collaborators.

Informality in Havana takes many different shapes. Commonly, it is demonstrated through ingenuity with material objects, which often entails giving new life to out-of-date and otherwise defective consumer technologies. The most famous example in this regard is the 1950s American automobiles that, since the reintroduction of tourism in the early 1990s, have become a global symbol of Cuban ingenuity.Footnote2 Informality also entails gaining access to hard currency. To do so, some residents offer specialized services such as handiwork or other forms of manual labor, while others tap into the more lucrative tourist economy. Most often, this involves engaging illicit activities such as sex work (Berg Citation2004) or street hustling (Carter Citation2008), both of which offer direct access to international currency. A third, but by no means final example of Havana’s informal life is that which emerges in response to the city’s housing crisis. As a way of “inventing” space to accommodate surplus inhabitants, residents undertake innovative projects that include the construction of barbacoas (mezzanine-like platforms) or casetas de azoteca (rooftop shacks) (del Real and Pertierra Citation2008; del Real and Scarpaci Citation2011). Such projects invariably bypass the approval of local authorities, and are manifestations of the collective need to creatively respond to the city’s precarious housing situation.

Informality and the cultural practices that condition inventar are notable, on the one hand, because they demonstrate the resolve of Havana’s residents. They generate a perspective of the city “from below,” which stands in contradistinction to the stories of despair and decay that tend to deny the political agency of the local population (as Ponte among others might argue). On the other hand, the focus on informality is notable because it cultivates a process-oriented understanding of the city. Drawing attention to the tenacity of the local population gives life not to moments of despondency born out of the precarity of the present, but rather, to moments of possibility that aspire toward a more inclusive, and perhaps even more sustainable future. These are the moments during which the city is “created” or “invented” through the collective knowledge of residents themselves. These are the future-making strategies that communicate what anthropologist Appadurai (Citation2013) might call the “politics of possibility”: everyday cultural articulations of resilience in which shared aspirations for a more egalitarian future are made tangible. There is thus the need to better understand how residents engage informal life both in Havana and in cities elsewhere, since such practices can indeed inspire a more equitable and democratic approach to urban design.

In response to the need for a more interdisciplinary approach to locating and evaluating the many contours of urban informality, I argue that in addition to the material and economic ingenuity of residents, a city’s informal life is also constituted by tacit, communicatory practices that are not only to be seen, but also to be heard. By turning a critical ear toward Havana’s everyday life, the unequal politics of the city are rendered audible. Here, I borrow from the work of ethnomusicologist Ana María Ochoa-Gautier (Citation2012), which elaborates sound and listening as a crucial realm through which Latin American modernity has been made and is being contested. “In speaking about Latin America as an aural region, I argue that under the contemporary processes of social globalization and regionalization coupled with the transformations in the technologies of sound, the public sphere is increasingly mediated by the aural” (Citation2012, 392). The “aural public sphere,” as Ochoa-Gautier terms it, denotes sound-based forms of political participation that emerge in and through public discourse. This includes Latin America’s formal and informal urban life, and the everyday contexts that comprise them. In Havana, the sound-based articulation of inventar can be conceived of as a manifestation of the aural public sphere, which emerges in response to the city’s precarious economic and material conditions.

4. Listening to the city

My research builds upon separate, but deeply related bodies of literature in the emergent field of sound studies. On the one hand, it draws from existing ethnographic research that makes use of methodological techniques based on sound and listening (Hirschkind Citation2006; Helmreich Citation2007; Chandola Citation2013; Kunreuther Citation2017, etc.). On the other, it is grounded in an emergent discussion about sound in Latin America and the Caribbean: a region in which there is no shortage of scholarly research on musical sounds (Crook Citation2005; Largey Citation2006; Moore Citation2006, etc.). However, as historians Alejandra Bronfman and Andrew Grant Wood observe, “music has practically drowned out other Latin American and Caribbean sounds” (Citation2012, xii), making the study of sound and listening a fertile point of departure for contemporary research. For instance, a dedicated focus on audio media has cultivated new understandings of the role of radio in the public sphere (González Citation2002; Casillas Citation2014) while the exploration of the historicity of sound has generated new regional histories (Bronfman and Wood Citation2012; Ochoa-Gautier Citation2014; Bronfman Citation2016). My work represents both a complement and a counterpoint to this body of research by employing an urban-centric, ethnographic approach to the study of present-day Havana, positioning it as a “sounding” city.

By thinking about Havana in and through sound, the everyday practices through which residents negotiate the conditions of economic and material precarity are rendered audible. In order to “read” these sounds as such, however, demands a robust understanding of both the city and the region’s social dynamics. What would ordinarily be interpreted as rather mundane attributes of the everyday soundscape could quite literally conceal an entire history of global relations. For instance, street vending in Havana is an auditory practice that dates back to the earliest days of the city. However, with the re-emergence of cuentapropismo in the early 1990s, and Cuba’s further incentivization of private enterprises in the early 2010s, Havana’s street vendors have begun to engage rather unconventional business practices. Vendors now sell products such as housewares (including clothes hangers, mops, and the like), used books, and some buy and sell jewelry while others offer mattress repair services.Footnote3 Each of these vendors offers an interesting contrast to the city’s more common and longstanding street vending practices, and each offers an example of entrepreneurial creativity in response to the hardship of the post-Soviet era. What then, does it mean to listen to a street vendor hawking their wares on the streets of Havana today?

Audio of Book Vendor

This raises further questions surrounding method. How does one study the everyday sounds of the city? And how does the fact that I am not a permanent, full-time resident of Havana complicate this pursuit? To develop an ethnographic account of the city in sound, I listened, I asked questions, and I engaged formal and informal conversations with others. My aim was to learn more about the general sounds of the city and how those sounds are encountered by others. Being a non-native resident challenged me to attune my ears to the various rhythms of the city. Yet, in spite of this challenge, my aural inexperience also proved advantageous. I inquired about the meanings of far more discrete sounds than a permanent resident otherwise would, and in light of my status as both a turista (or, tourist) and an ethnographer, the network of people I encountered throughout my travels tended to support my interest. This support was also articulated in an official capacity through my status as a visiting scholar at Fundación Fernando Ortiz, a research institution dedicated to studying Cuban art, folklore, and culture. There, I worked alongside Dr. Aurelio Francos Lauredo, who acted as somewhat of a gatekeeper to the city, putting me in touch with people and places of interest to my study.

As a methodological practice, sonic ethnography is grounded in the researcher’s own listening, which in turn, is used to learn about the ways that others also listen. “Acoustemology” is the term that anthropologist Steven Feld uses to refer to the potentiality of knowing through sound and listening. Feld writes, “acoustemology joins acoustics to epistemology to investigate sounding and listening in action: a knowing-with and knowing-through the audible” (Citation2015, 12). As a sonic ethnographer, it was my aim to learn more about the ways that sound and listening enable Havana’s residents to collectively negotiate the city’s precarious economic and material conditions. In doing so, however, I do not overlook the fact that embodied experience is necessarily multimodal, and that residents navigate the city using some combination of vision, touch, smell, and taste as well. Each of these sensory registers represents a fertile point of departure for scholarly inquiry and it would be a misstep to essentialize any one sense at the expense of others (Howes Citation2003; Pink Citation2009, Citation2011). Nevertheless, the distinct focus on sound and listening represents a counterpoint to more traditional scholarly approaches to exploring Latin American cities, and it offers the opportunity to locate some of the many ways the public sphere is made tangible.

An important technique that operates as both a supplement and an aid to the sonic ethnographer’s situated act of listening is that of audio recording. Developing audio documentation of one’s experiences “in the field” enables the recordist to revisit, slow down, and pause those experiences to listen to them anew. It enables a deepened form of analysis that emerges from the recordist’s control over a representation of the ethnographic moment. In this sense, my approach to sonic ethnography is that of a media-based practice, which I borrow from pioneering research in soundscape studies and sound anthropology (World Soundscape Project Citation1973; Schafer Citation1977; Feld and Brenneis Citation2004). My work in Havana embodies such an approach on two fronts: the first of which is archival. As part of my residency at Fundación Fernando Ortiz, I collaborated with Dr. Francos Lauredo on the development of a sonic archive of the city. Working on this collection of sounds offered me the opportunity to travel to dozens of neighborhoods in Havana to explore and document the soundscapes that comprise them. Today, this archive is housed in digital format at Fundación Fernando Ortiz and is available for the use of students, artists, and researchers alike.

And the second front upon which my ethnographic work functions as a media-based practice is through the work I engage as an audio media producer. Working with the raw audio I captured in Havana pushed me to think about my research in new ways and the contributions it makes to discussions about the city. The incorporation of audio media not only offers an added dimension for the reading audience, but it also creates a distinct point of access for the ideas more broadly. Because audio circulates in different ways than writing alone (e.g. podcasts, radio, online resources, etc.), scholarly work represented as audio media has the capacity to reach diverse (and potentially broader) audiences. For these reasons, I developed an audio documentary that is an aural articulation of the written ethnography that follows. In sound, it illustrates a daily episode of malfunctioning water infrastructure that took place in a neighbourhood in the district of El Vedado – the neighborhood in which I lived. The documentary not only brings to life the fragility of the city’s urban infrastructures through sound, but it also brings to life the creative and collective aural practices residents use to negotiate them.

Audio of Book Vendor

5. Sounding out Havana’s built environment

Audio Documentary

While in Havana, I woke up almost every day at the same time and in the same way. At about 6:45am, a slow, steady water drop began falling onto the air conditioner in my bedroom window. The shape and density of the air conditioner’s aluminum enclosure, combined with the height from which the water was falling, created a loud, thud-like sound that made it impossible to sleep. Bloop. Bloop. Bloop. If I listened long enough, I began to hear the sound in new ways. Smack! Then, womp womp womp. The enclosure resonates after the water lands. Initially, I thought these were the sounds of rain. But without fail, I’d walk out onto the balcony and see nothing in the sky but the hot Caribbean sun.

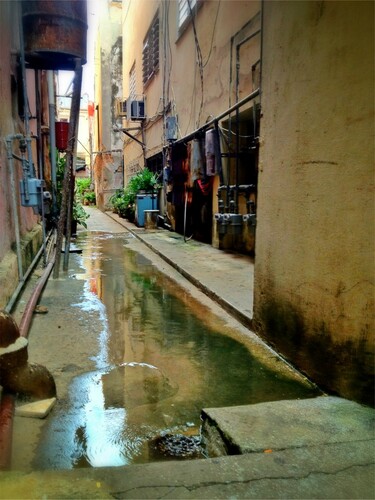

So, I asked my roommate about these sounds. His bedroom was right next to mine, so he knew exactly what I was referring to. He led me up the stairs of the apartment and out onto the rooftop. There, sat a large communal reservoir that supplies water to each apartment in the building. It’s filled twice daily, and each time, almost without fail, it overflows. The excess water makes its way across the rooftop and over the side of the building. Along its downward route is my window, where it slowly accumulates, causing the early morning dripping. Through both drainage pipes and alongside the outer wall of the building, the water then makes its way into the laneway below, which it then floods before it falls into the sewer, completing its journey through the neighborhood.

Directly affected by the errant streams and flows however, are the residents who live at ground level in the building next door. Once a single-family, fully detached home, the building has since been converted into an apartment that now houses upward of 20 or 25 people. By Havana’s standards, it’s not very old, but the numerous modifications it’s undergone over the years have put added stress on the structure – to the point that it now has a series of wooden planks leaning against the outer wall for additional support.

One such modification is that the laneway is now the entrance to a number of small makeshift apartments known as cuarterías. When the laneway is flooded, it becomes inconvenient if not altogether unmanageable for residents to enter and exit without stepping in the water. For a short period of time, an important part of their already limited living space is unusable. To make matters worse, these residents often hang their laundry to dry in the precise location where water tends to fall. More than simply an occasional, inconsequential episode, the water runoff is a daily disruption that affects a number of households in the community.

For residents, this sequence of events issues a not-so-subtle reminder of the precarity of the built environment. On the one hand, the overflowing occurs as a result of a water supply system that is less than fully functional. And on the other hand, residents most immediately affected by the overflow live in makeshift apartments that are both structurally deteriorated and situated in undesirable locations. The water overflow and runoff are therefore not just representative of a haphazard sequence of events within the confines of this neighborhood alone. Rather, this seemingly insular encounter is symptomatic of a series of broader urban and regional issues that include overpopulation and infrastructural and architectural ruination. Taken together, these conditions comprise an “urban crisis” (Clark Citation1998) that characterizes not only the city of Havana, but cities across Latin America and the Caribbean.

The conditions of ruination and overpopulation in my neighborhood compel residents to find ways of mitigating the daily overflow and runoff. One way they do so is in sound and listening. In particular, residents mobilize the community around the running water as a way of mitigating the disruption. It unfolds as follows.

Filling the reservoir usually takes place at 5 or 5:30am and then again at 2 or 2:30pm. It is looked after by our neighbor Ariel whose apartment is on the fifth and top floor, nearest the reservoir. Using a switch from inside his home, Ariel activates a motorized pump in the parking garage below (as seen in ), which draws water up through the supply lines into the tank above. Residents gain access to the water by simply turning on one of the faucets in their home or by flushing the toilet, allowing gravity to take its course. Typically, the reservoir takes a couple of hours to fill, depending on the amount of water used over the course of the day. Once the reservoir is full however, it overflows quickly and without warning.Footnote4 The water then travels across the rooftop and over the side of the building where it traverses a number of cables, windows (including my own), and pipes before it floods the laneway below. Ariel does his best to prevent the spilling by turning off the pump before the tank overflows, but even on a good day, a small amount finds its way onto this expected route.

Without fail, this series of events brings one, or even several residents who live in the makeshift apartments out of their homes and into the laneway. They immediately shout up to Ariel aiming to notify him – and everyone else in the community – of yet another overflow. One resident in particular predictably whistles three times before yelling the phrase ¡se bota el tanque! which translates to “the water is overflowing!”. At times, neighbors who live in second, third, and fourth-floor apartments will chime in. These residents either repeat the call of those in the laneway, expediting the message up to Ariel, or they express their own discontent with yet another disturbance by saying things like ¡oye llevo dos horas avisándole!, meaning “I’ve been saying [the water is overflowing] for the last two hours!”. This of course is impossible because the disruption begins and ends within a matter of about 15 minutes. But it illustrates residents’ frustration with the daily occurrence, which is expressed by community members who are not even directly affected by it. Ariel of course acknowledges the calls, first by responding vocally, then by turning off the motor.Footnote5

Clearly, sound plays an integral role in this sequence, if for no other reason than by way of the dialogue itself. By shouting into and out of the home, residents communicate with one another in a timely manner. Doing so allows those at ground level to immediately alert community members of another water mishap. So, by hollering up to Ariel from the laneway, ground-level residents declare something to the effect of “the water is overflowing, turn off the pump.” But in another sense, the act of shouting up to Ariel – and to the rest of the community – implies something more akin to “these spaces are being flooded, not only do I live here, but I am here.” It represents a means through which to redraw the limits of the neighborhood’s living spaces and recover them in a timely manner, while it is also a symbolic gesture enacted with the intent of reasserting an embodied presence in one’s own living space.

Yet, residents listen to sounds that extend beyond those of vocal communication alone. Before the shouting begins, and even before the water makes its way into the laneway, residents are already aware of the activity taking place within their neighborhood. The first and most obvious sound associated with filling the reservoir is the broadband, steady-state drone of the water pump that sits at ground level. Generated by an electric motor, this sound is quite loud and it announces to residents that the reservoir is being filled. Once full, the tank’s overflow begins to splatter on the rooftop (see ), but only those who live nearby can hear it. Following its descent, however, the water bubbles and splashes as it springs from drainage pipes and flows over the cement floor of the laneway. For ground level residents, these are the most urgent sounds. They indicate that the laneway is being flooded and are the final acoustic call to action. Eventually, the flowing water empties into the sewer, but by the time residents hear it, the water has already completed its route through the spaces of the neighborhood (see ).

The numerous sounds produced over the course of this sequence enable residents to accurately follow the water along its expected route, even if they are not physically co-present with it. Through open windows and doors, residents listen to the sounds of supply infrastructure and remain attuned to the possibility of laneway flooding. At the outset, the motorized water pump makes residents aware that the reservoir is being filled. So, by the time the water arrives in the laneway, usually about an hour and a half later, residents are prepared. This immediately brings those in ground level cuarterías outside, who then notify the rest of the neighborhood. The sooner ground level residents hear the water, the sooner everyone alerts Ariel, and ultimately, the sooner the flooding comes to an end. In so doing, residents take the opportunity to partially – and at times, almost entirely – mitigate the flooding. Long before the shouting begins, the act of listening is a means through which residents assert their embodied presence in the neighborhood. It is a tacit first step in a series of preventative measures that safeguard their living spaces. And it is accomplished through a form of everyday listening that remains attuned to the sounds of the neighborhood and its faulty water delivery infrastructure.

Audio Documentary

6. Conclusion

Turning a critical ear toward everyday life in Havana constructs a version of the city, its infrastructure, and its architecture that remains otherwise unrepresented in more traditional forms of scholarship. In sound and listening, the city’s conditions of disrepair are indeed audible, but so too are the ways that residents creatively and collectively negotiate those conditions. The daily episode explored in this paper makes tangible both versions of the city: one characterized by overpopulation and a malfunctioning water infrastructure, and one that is, quite simply, lived in by residents themselves. This highly localized account of Havana, developed in both written words and audio media, communicates an untold story about the city, its residents, and the tacit ingenuity that propels their everyday life. In so doing, it gives rise to a perspective of urban informality that both expands and challenges traditional understandings of the concept. Urban informality, I maintain, can more comprehensively be accounted for when it is conceived of as an embodied, communicatory process. For this reason, sound and the everyday act of listening offers a fertile point of departure for scholars aiming to better understand the creative and collective practices of urban dwellers both in Havana and elsewhere in Latin America.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Vincent Andrisani, PhD, is a Term Lecturer in Simon Fraser University’s School of Communication. His work has been presented at conferences and festivals internationally, and can be found in outlets such as Soundscape: The Journal of Acoustic Ecology, Sounding Out! Blog, and at TEDx. Intersecting the areas of sound studies, cultural geography, and Cuban studies, Vincent’s research explores the relationship between sound, space, and citizenship in Havana, Cuba. www.vincentandrisani.com @soundscrunchy

ORCID

Vincent Andrisani http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1542-5311

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 According to Cuba’s Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información (Citation2015), as of 2014 there were 87,305 residents living in Habana Vieja.

2 Mid-century American cars, known locally as almendrones, have perhaps more prominently become a cultural symbol read popularly in terms of Cuba’s temporality. While they remain essential transportation for everyday Cubans, these cars demarcate a historical moment of pastness for most Western observers.

3 Not only are mattress repair services useful in light of the widespread need for long-term housing and sleeping arrangements, but they also tap into the ingenuity of locals who are familiar with the restoration of an important household item.

4 The reason that it continually overflows is because the float ball assembly that regulates filling is broken. Ironically, this assembly and the motorized system are relatively new in comparison to what is used throughout the rest of the city. Presumably, because it is not widely used, finding the parts to repair the fill valve have been challenging. As such, residents have simply learned to make do with the faulty system until a new float ball assembly becomes available.

5 This type of hyperbole is not uncommon in Cuba. It’s a popular form of dialogue known as choteo: informal humour that explicitly targets authority with the aim of undermining it. About choteo, scholar Damián J. Fernández (Citation2000) writes, “The choteo deauthorizes authority by debunking it and constitutes a form of rebellion. It is undisciplined, unserious, even if the business at hand is of the utmost importance. It reflects contempt for and cynicism about higher-ups and the institutions of society … the purpose is to use humour as a way to privatize social relations by making them accessible, at least momentarily, by bringing the people and the institutions that stand above the common folk down to the level of the popular, of the streets, of “us.” This is choteo’s equalizing effect” (31).

References

- Appadurai, A. 2013. The Future as Cultural Fact: Essays on the Global Condition. London: Verso Books.

- Berg, M. L. 2004. “Tourism and the Revolutionary New Man: the Specter of Jineterismo in Late ‘Special Period’ Cuba.” Focaal 2004 (43): 46–56. doi: 10.3167/092012904782311371

- Bronfman, A. 2016. Isles of Noise: Sonic Media in the Caribbean. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

- Bronfman, A., and A. G. Wood. (Eds.). 2012. Media, Sound, & Culture in Latin America and the Caribbean. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Carter, T. F. 2008. “Of Spectacular Phantasmal Desire: Tourism and the Cuban State’s Complicity in the Commodification of its Citizens.” Leisure Studies 27 (3): 241–257. doi: 10.1080/02614360802018806

- Casillas, D. I. 2014. Sounds of Belonging: U.S. Spanish-Language Radio and Public Advocacy. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Chandola, T. 2013. “Listening in to Water Routes: Soundscapes as Cultural Systems.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 16 (1): 55–69. doi: 10.1177/1367877912441436

- Clark, J. 1998. “ The Housing Dimension in Cuba’s Urban Crisis: Havana as a Case in Point.” Accessed Vivienda en Cuba website: http://housingcuba.blogspot.ca/p/cubas-urban-crisis_23.html

- Cocq, K. 2006. Change, Continuity, and Contradiction in the Cuban Waterscape: “Privatization” and the Case of Aguas de la Habana. Queen’s University, Kingston, ON.

- Coyula, M. 2011. “The Bitter Trinquennium and the Dystopian City: Autopsy of a Utopia.” In Havana Beyond the Ruins: Cultural Mappings After 1989, edited by A. Birkenmaier and E. K. Whitfield, 31–52. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Crook, L. 2005. Brazilian Music: Northeastern Traditions and the Heartbeat of a Modern Nation. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

- del Real, P., and A. C. Pertierra. 2008. “Inventar: Recent Struggles and Inventions in Housing in Two Cuban Cities.” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 15: 78–92. doi: 10.1353/bdl.0.0002

- del Real, P., and J. L. Scarpaci. 2011. “Barbacoas: Havana’s New Inward Frontier.” In Havana Beyond the Ruins: Cultural Mappings After 1989, edited by A. Birkenmaier and E. K. Whitfield, 53–72. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Eckstein, S. 1985. “The Debourgeoisement of Cuban Cities.” In Cuban Communism. 5th ed., edited by I. L. Horowitz, 91–111. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Feld, S. 2015. “Acoustemology.” In Keywords in Sound, edited by D. Novak and M. Sakakeeny, 12–21. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Feld, S., and D. Brenneis. 2004. “Doing Anthropology in Sound.” American Ethnologist 31 (4): 461–474. doi: 10.1525/ae.2004.31.4.461

- Fernández, D. J. 2000. Cuba and the Politics of Passion. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Fischer, B. 2014. “Introduction.” In Cities from Scratch: Poverty and Informality in Urban Latin America, edited by B. Fischer, B. McCann, and J. Auyero, 1–8. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- González, R. 2002. Llorar es un Placer. La Habana: Editorial Letras Cubanas.

- Helmreich, S. 2007. “An Anthropologist Underwater: Immersive Soundscapes, Submarine Cyborgs, and Transductive Ethnography.” American Ethnologist 34 (4): 621–641. doi: 10.1525/ae.2007.34.4.621

- Hirschkind, C. 2006. The Ethical Soundscape: Cassette Sermons and Islamic Counterpublics. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Howes, D. 2003. Sensual Relations: Engaging the Senses in Culture and Social Theory. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Kunreuther, Laura. 2017. “Democratic Soundscapes.” The Avery Review 21: 17–27.

- Largey, M. D. 2006. Vodou Nation: Haitian art Music and Cultural Nationalism. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lasansky, D. M. 2004. “Tourist Geographies: Remapping Old Havana.” In Architecture and Tourism: Perception, Performance and Place, edited by D. M. Lasansky and B. McLaren, 165–186. Oxford: Berg.

- Mehrotra, R. 2010. Foreword. In Rethinking the Informal City: Critical Perspectives from Latin America (pp. xi–xiv). New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

- Moore, R. 2006. Music and Revolution: Cultural Change in Socialist Cuba. Pittsburgh, PA: University of California Press.

- Ochoa-Gautier, A. M. 2012. “Social Transculturation, Epistemologies of Purification and the Aural Public Sphere in Latin America.” In The Sound Studies Reader, edited by J. Sterne, 388–404. London: Routledge.

- Ochoa-Gautier, A. M. 2014. Aurality: Listening and Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century Colombia. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información. 2015. Anuario Estadístico La Habana 2014: La Habana Vieja.

- Pink, Sarah. 2009. Doing Sensory Ethnography. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- Pink, S. 2011. “Multimodality, Multisensoriality and Ethnographic Knowing: Social Semiotics and the Phenomenology of Perception.” Qualitative Research 11 (3): 261–276. doi: 10.1177/1468794111399835

- Ponte, A. J. 2002. Tales from the Cuban Empire (C. Franzen, Trans.). San Francisco, CA: City Lights.

- Ponte, A. J. 2011. “La Habana: City and Archive.” In Havana Beyond the Ruins: Cultural Mappings After 1989, edited by A. Birkenmaier and E. K. Whitfield, 249–269. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Porter, A. L. 2008. “Fleeting Dreams and Flowing Goods: Citizenship and Consumption in Havana Cuba.” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 31 (1): 134–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1555-2934.2008.00009.x

- Redruello, L. 2011. “Touring Havana in the Work of Ronaldo Menéndez.” In Havana Beyond the Ruins: Cultural Mappings After 1989, edited by A. Birkenmaier and E. K. Whitfield, 229–245. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Rojas, R. 2011. “The Illegible City: Havana After the Messiah.” In Havana Beyond the Ruins: Cultural Mappings After 1989, edited by A. Birkenmaier and E. K. Whitfield, 119–134. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Scarpaci, J. L., R. Segre, and M. Coyula. 2002. Havana: Two Faces of the Antillean Metropolis. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press Books.

- Schafer, R. M. 1977. The Tuning of the World. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

- World Soundscape Project. 1973. The Vancouver Soundscape (R. M. Schafer, Ed.). Burnaby, BC: World Soundscape Project, Sonic Research Studio, Dept. of Communication, Simon Fraser University.