ABSTRACT

Although a considerable amount of research on the Lampung language has been done, little attention has been paid to the use of technology-based Lampung language maintenance. Therefore, academic and practical efforts should be made to contribute to the local language maintenance and one of the possible solutions is through technology. The aim of the present study was to develop an Android-based bilingual dictionary application for smartphones for language maintenance. This study adopted developmental research with three phases (analysis, product design and development, and product try-out and evaluation). The data was collected through instruments including literature reviews, interviews, expert judgments, and questionnaires followed by descriptive analyses. The results indicate that the development of an Android-based Lampung language dictionary application for smartphones has successfully contributed to Lampung language maintenance and preservation. The Android-based application is positively perceived as a form of minority language maintenance and preservation in the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) era. The study’s implications and recommendations are also discussed for future research.

ABSTRATO

Embora uma quantidade considerável de pesquisas sobre a linguagem Lampung tenha sido feita pouca atenção tem sido dada ao uso da preservação da linguagem Lampung baseada em tecnologia. Portanto, esforços reais, tanto acadêmicos quanto práticos, devem ser feitos para contribuir com a manutenção do idioma local e uma das soluções possíveis é através da tecnologia. O objetivo do presente estudo foi desenvolver um aplicativo de dicionário bilíngue baseado em Android para smartphones com o objetivo de manutenção do idioma. Este estudo adotou a pesquisa de desenvolvimento com três fases (análise, design e desenvolvimento do produto, e try-out e avaliação do produto). Os dados foram coletados por meio de instrumentos incluindo revisão de literatura, entrevistas, julgamentos de especialistas, e questionários seguidos de análises descritivas. Os resultados indicam que o desenvolvimento de um aplicativo de dicionário do linguagem Lampung baseado em Android para smartphones contribuiu com sucesso para a manutenção e preservação da linguagem Lampung. O aplicativo baseado em Android é positivamente percebido como uma forma de manutenção e preservação de linguagens minoritárias na era da Quarta Revolução Industrial (4IR). As implicações do estudo e recomendações para pesquisas futuras também são discutidas.

RESUMEN

Aunque se ha hecho una cantidad considerable de investigación sobre el lenguaje Lampung, se ha prestado poca atención al uso del mantenimiento del lenguaje Lampung basado en tecnología. Por lo tanto, se deben realizar esfuerzos reales, tanto académicos como prácticos, para contribuir al mantenimiento del idioma local y una de las posibles soluciones es a través de la tecnología. El objetivo del presente estudio fue desarrollar una aplicación de diccionario bilingüe basada en Android para teléfonos inteligentes con el objetivo de preservar el idioma. Este estudio adoptó la investigación del desarrollo con tres fases (análisis, diseño y desarrollo de productos y prueba y evaluación de productos). Los datos fueron recolectados a través de instrumentos, incluyendo revisión de literatura, entrevistas, juicios de expertos y cuestionarios seguidos de análisis descriptivos. Los resultados indican que el desarrollo de la aplicación de diccionario de idioma Lampung basada en Android para teléfonos inteligentes ha contribuido con éxito al mantenimiento y preservación del idioma Lampung. La aplicación Android se percibe positivamente como una forma de mantenimiento y preservación de idiomas minoritarios en la era de la Cuarta Revolución Industrial (4IR). También se discuten las implicaciones del estudio y las recomendaciones para futuras investigaciones.

1. Introduction

It is widely accepted that technology can be used to assist a minority language population in maximizing the benefits of language maintenance depending on their cultural and linguistic circumstances (Little Citation2020; Palviainen Citation2020; Villa Citation2002). In so doing, a language can be electronically stored, documented, preserved, and maintained (Bosch and Griesel Citation2020; Stahlberg Citation2021; Wamalwa and Oluoch Citation2013).

There is now much evidence to support the argument that technology plays an essential role in language maintenance and preservation. As mobile applications have mushroomed in recent years, they have become some of the most progressive technologies (Murdianto, Abdillah, and Panjaitan Citation2015). Social media and new technology are now considered powerful tools for language maintenance and revitalization that enable native speakers to use their language in new domains and connect with other speakers in the world (Jany Citation2018). These processes infuse a beleaguered minority language with new linguistic forms or social functions that enhance its uses or users (Eisenlohr Citation2004; Xu Citation2020). One of such minority languages in Indonesia is the Lampung language in Lampung province, located on Sumatra island, Indonesia.

It is reported that Lampung's indigenous people are said to be in the minority (Rusminto et al. Citation2021; Warganegara and Waley Citation2021). They do, however, hold a favorable opinion of their native language (Ariyani, Rusminto, and Setiyadi Citation2018; Rusminto, Ariyani, and Setiyadi Citation2018; Widodo, Ariyani, and Setiyadi Citation2018; Wulandari Citation2019). However, three facts can put Lampung language at risk of not being used, including shifts in language domains, lack of written or printed linguistic information, and limited numbers of speakers (Astuti Citation2017).

The full extent of technology is therefore a potential pathway for Lampung language maintenance and preservation. An Android-based dictionary, for example, can be an alternative tool for learning regardless of place and time (Wirawan and Paryatna Citation2018). Additionally, studies indicate that 40% of adults and teenagers own a smartphone and use it for more than four hours every day for calls and messaging (Cha and Seo Citation2018; Dong et al. Citation2020; Enthoven et al. Citation2021; Gonçalves, Dias, and Correia Citation2020). In Indonesia, according to reports, every university student from a high socioeconomic position owned a smartphone by 2016, while 94.12% of those from a middle to low socioeconomic strata owned a smartphone (Pratama Citation2017). Every day, over five hours are spent on these devices (Pratama Citation2018).

Although a considerable amount of research on the Lampung language has been done (see, among others, Ariyani Citation2015; Ariyani et al. Citation1999; Ariyani, Kadaryanto, and Rahmansyah Citation2015; Ariyani, Rusminto, and Setiyadi Citation2018; Katubi Citation2006; Rusminto, Ariyani, and Setiyadi Citation2018, Citation2021; Widodo, Ariyani, and Setiyadi Citation2018; Wulandari Citation2019), little attention has been paid to the use of technology-based Lampung language maintenance, and using an Android-based application in particular. Therefore, the purpose of the present study is to contribute to Lampung language maintenance electronically through the development of an Android-based bilingual dictionary application for smartphones.

2. Literature review

2.1. Lampung language

Lampung is a province located in the southernmost tip of Sumatra island, Indonesia. The province is multi-ethnic and multilingual, inhabited by various ethnic groups (Sunarti et al. Citation2019). According to the 1980 state census, Lampung was inhabited by 4,624,238 people, with 65% transmigrants (outsiders) from other provinces in Indonesia, and the rest native to Lampung (Rusminto et al. Citation2021). The native people of Lampung are divided into Saibatin and Pepadun traditions (Mustika Citation2020; Thomas Citation2014), and their Lampung language is a part of Western Malayo-Polynesian (Frawley Citation2003; Solleveld Citation2020).

The Lampung language, with about 1.5 million native speakers, has two and/or three dialects: Lampung Api (Pesisir or A-dialect), Lampung Nyo (Abung or O-dialect), and Komering. The Komering dialect is sometimes included in the Lampung Api dialect, but also sometimes considered an entirely different language. Ethnically, Komering people see themselves as separate from the Lampung people (Sudirman Citation2019).

The Lampung Api dialect, spoken by 979,000 native speakers (Joshua Project Citation2020a), can be found in areas including Pubian, Sungkai, Way Kanan, Kayu Agung, Komering, Belalau, Ranau, Pesisir Krui, Pesisir Semaka, Pesisir Teluk, Pesisir Rajabasa, Melinting-Maringgai, and Sekala Brak (Imron Citation2021; Sujadi Citation2012; Sunarti et al. Citation2019). Lampung Nyo, spoken by 204,000 native speakers (Joshua Project Citation2020b), can be found in the areas of West Tulang Bawang, Menggala/Tulang Bawang, Sukadana, and Abung (Imron Citation2021; Sujadi Citation2012; Sunarti et al. Citation2019). The Lampung language map is given in .

Figure 1. Lampung language map (Lampung Api is in the upper circle, Lampung Nyo is in the middle, and Komering is in the lower circle). Source: Glottolog Citation2020.

2.2. Language maintenance in Lampung

Language maintenance (and language shift) is closely related to “the correlation between change or continuity in routine language use, on the one hand, and ongoing psychological, social, or cultural processes, on the other hand, when communities of different languages come into contact among each other” (Fishman Citation1964, 32). In Indonesia, language maintenance appears paradoxical today. A few major local languages in the western part of Indonesia have much better prospects for language maintenance than those in the eastern part (Musgrave Citation2014). Since the 1990s, due to concern about the loss of linguistic diversity and local language issues, including minority languages, maintenance has received considerable attention (Cohn and Ravindranath Citation2014). Native speakers of a language should form a cohesive group, capable of resisting linguistic and social pressure from outside the group (Riagáin Citation1994). Wright (Citation2018, 18) argued that, in the modern era, even when moving into “new communities of communication,” people should be given “the right and the opportunity to integrate” their native language and cultures into their new settings.

Although the Lampung language is spoken by a relatively large number of native speakers, it is a minority language in the province (Rusminto et al. Citation2021; Warganegara and Waley Citation2021). A considerable amount of real effort has been taken to maintain the native language of Lampung (see, for example, Abidin, Permata, and Ariyani Citation2021; Ariyani Citation2015; Ariyani et al. Citation1999; Ariyani, Kadaryanto, and Rahmansyah Citation2015; Ariyani and Rahmansyah Citation2015). The situation has also led the local government to maintain the Lampung language through local regulations and public policies. The Lampung language, its script, and its cultural wealth must be maintained and developed (Local Regulation of Lampung Province on Cultural Maintenance of Lampung Citation2008, para. 7) through its use as a medium of instruction at schools and government meetings (para. 8). The local government also released other local regulations for Lampung language maintenance, e.g. Local Regulation of the Governor of Lampung Province Number 39/Citation2014 on Lampung Language as a Mandatory Local Content Lesson in Elementary, Primary, and Secondary Schools and Local Regulation of the Governor of Lampung Province Number 4/Citation2011 on Maintenance, Development, and Preservation of Lampung Language.

2.3. Technology, language maintenance, and Android-based dictionary application

A large body of data concerning the use of technology for informal online learning has been reported. Putrawan and Riadi (Citation2020) found in their study that participants predominantly perform their online informal learning activities in Indonesian, English, and both Indonesian and English. In other words, they do not perform their online activities using their local language; the Lampung language, for example. In contrast, technology and social media nowadays, according to Jany (Citation2018), can be used as beneficial instruments to maintain native and heritage languages. Bettinson and Bird (Citation2017) argue that today it is of importance to integrate technology and language maintenance.

Language communities, for example, can develop attractive websites, or integrate online language learning platforms to invite potential speakers to their languages (Ngo and Eichelberger Citation2020; Schreyer Citation2011), suggesting technology is a beneficial instrument for language maintenance and language learning. Another form of technology that can be used for native language maintenance and learning today is an Android-based application (see, for example, Aziz and Harafani Citation2016; Kasema, Sentinuwo, and Sambul Citation2019; Koen and Bulan Citation2018; Murdianto, Abdillah, and Panjaitan Citation2015) as an alternative tool that can be used for learning from anywhere and at anytime. Most adults and adolescents in Indonesia have a smartphone and use it for many hours per day (Pratama Citation2017) and the most popular mobile operating system in Indonesia is Android, with a total of 92.65% market share (StatCounter Citation2020). The number of smartphone users in Indonesia was estimated to reach 81.87 million users in 2020, and Indonesia itself is one of the largest smartphone markets in the world after China, India, and the United States (Statista Citation2020).

The advancement of the Internet and digital technology may thus open up new avenues for language preservation (Guskaroska and Elliott Citation2021). For instance, online games can be an extremely beneficial resource for children developing literacy in their native language (Eisenchlas, Schalley, and Moyes Citation2016). Attitudes toward digital games among heritage language families are motivated by issues of identity construction and language maintenance (Little Citation2019). New technology and social media platforms are now viewed as vital tools in the effort to preserve and revitalize endangered languages (Holton Citation2012; Jany Citation2018). To save endangered languages, there are two broad categories of technologies. It begins with “products” created by a team of developers or authors for a specific user community, for example, multimedia, computer-assisted language learning, and electronic dictionaries. Technology that helps people learn and use languages, such as emails and chat rooms, falls into the second category of “online technologies” (Holton Citation2012, 375). User feedback, as stated in the literature, indicates that there are numerous advantages to making indigenous language learning apps available on smartphones and tablets. Apps are emerging as a promising tool for the revitalization and maintenance of indigenous languages in everyday life (Cassels and Farr Citation2019).

3. The study

A substantial amount of research has been done on the Lampung language (see, among others, Ariyani Citation2015; Ariyani et al. Citation1999; Ariyani, Kadaryanto, and Rahmansyah Citation2015; Ariyani, Rusminto, and Setiyadi Citation2018; Katubi Citation2006; Rusminto, Ariyani, and Setiyadi Citation2018, Citation2021; Widodo, Ariyani, and Setiyadi Citation2018; Wulandari Citation2019). However, little attention has been paid to the use of technology-based Lampung language maintenance in general and to the use of an Android-based application in particular. Due to the minority status of Lampung language native speakers (Rusminto et al. Citation2021; Warganegara and Waley Citation2021), a language shift is occurring. If continued, the language will become endangered and eventually extinct (Putri Citation2018). Additionally, significant academic and practical efforts should be made to contribute to language preservation, and one possible solution is to use technology. As a result, conducting research on Lampung language maintenance via technology is of interest. The purpose of this project is to electronically contribute to the Lampung language maintenance by developing a bilingual dictionary application for smartphones based on the Android operating system.

This study used design and development research (DDR), defined as a systematic investigation involving design, development, and evaluation processes to establish an empirical foundation for the development of instructional and non-instructional products and tools, as well as new or enhanced models that govern their development (Richey and Klein Citation2014). DDR has two major categories of research projects: “research on products and tools” and “research on design and development models” (Richey and Klein Citation2014), which were previously referred to as Type 1 and Type 2 developmental research (Richey and Klein Citation2005). The developmental research is also known as design research (van den Akker et al. Citation2006) in which the term design research itself is with abundant labels that can be found in the literature, such as design studies, design experiments, development/developmental research, formative research, formative evaluation, and engineering research (van den Akker et al. Citation2006). DDR can be done through quantitative and qualitative research methods, but most tend to be dependent more on qualitative methods and techniques to deal with real-life projects (Richey and Klein Citation2014) and problem-solving functions (Richey and Klein Citation2005).

3.1. Participants

The research involved different types of participants depending on the research stage (Richey and Klein Citation2005). details the participants involved in each stage.

Table 1. Types of participants taking part in this present study.

Participants in the analysis phase, which included needs and context analyses, were students, young adults (Android users), and Lampung natives. Participants in the product and development phase included designers, developers, young people (Android users), and Lampung natives. The final stage of the study involved evaluators, young people (Android users), students, and the Council of Traditional Lampung Elders. The participants were chosen based on the following criteria: university students born and raised in Lampung, Android users who were native or non-native Lampung speakers, and Lampung native speakers. Additionally, designers and developers of Android applications were consulted to evaluate the project's dictionary for Android. Finally, Lampung traditional elders and evaluators with backgrounds in linguistics (Lampung, Indonesian, and English), culture, and information and technology were invited to assess the application's content, design, and functionality. The study enrolled 40 students, ten young people, 40 Lampung native speakers, three linguists, three designers and developers, and ten Lampung traditional elders.

3.2. Research design

The project employed the first category of DDR, which is research on products and tools (Richey and Klein Citation2014), during the design and development of an Android-based dictionary application for smartphones in three languages: Lampung, Indonesian, and English. This project adopted a comprehensive first category of DDR, which included an analysis phase, a design and development phase, and a try-out and evaluation phase (Richey and Klein Citation2005, Citation2014) conducted from February to November 2020.

The present study also adopted various research methodologies and designs (Richey and Klein Citation2005) adequate for each of the phases of the project. gives information about the research methods and designs used in each phase.

Table 2. Types of research methods and designs in different phases.

The analysis phase was structured using literature review and document analysis, survey, and in-depth interviews. The product design and development phase used a case study research design. The evaluation research technique, survey, interviews, and expert review were adopted to determine the product's effectiveness (Android-based dictionary application) and test the application.

3.3. Data collection and analysis

The data collection took various forms because the validity of the conclusion is dependent on the richness of the data set and research design quality (Richey and Klein Citation2005). illustrates the instruments used for data collection, including literature review, survey, and interviews with native people of Lampung in the analysis phase conducted to answer the main questions: (1) What do you think about Lampung language maintenance today? (2) May an Android-based dictionary application be able to address one of Lampung language challenges currently faced by Lampung people in terms of language maintenance? (3) If so, who should be the target audience? (4) When should it be offered to users? In addition, we also asked them to list ten Lampung words that they use daily, along with a sample sentence for each word. They were then alphabetically compiled and translated into Indonesian by those fluent in Lampung and Indonesian and into English by English scholars fluent in Lampung and English. To ensure the data's validity and accuracy, they were cross-checked with key informants.

Table 3. Instruments for data collection and data analysis.

In the second phase, the findings of the first phase were used to guide the design and development. The product design, with contents that had been evaluated, was distributed to the team of experts for review. They were asked to evaluate the design and provide comments and/or feedback. After their evaluation and feedback, a date was set with each expert for interviews. Finally, all data collected from the evaluation and interviews were carefully analyzed and discussed.

In the last phase, the Android-based dictionary application, evaluated and reviewed by the experts, was implemented over two weeks with 40 student participants, ten young people, and ten traditional Lampung elders. Their perceptions toward the application were studied, and the difficulties and obstacles during their use of the application were determined. Data were collected from their responses during the implementation of the application, questionnaires, and interviews after completing the application implementation. Finally, the final version of the application was created, and additional functionality was added based on the users’ input. The last phase was aimed more at gaining insights related to the potential impact the application that had been developed could make.

4. Results

An Android-based bilingual dictionary application for smartphones was developed through DDR, including analysis, product and design development, and product try-out and evaluation phases.

In the analysis phase, we, first of all, undertook a context analysis through a literature review. It is evident that the Lampung language maintenance through technology, Android-based application especially, is underexplored even through a considerable amount of practical and academic efforts have been made to contribute to its maintenance (see, for example, Ariyani Citation2015; Ariyani et al. Citation1999; Ariyani, Kadaryanto, and Rahmansyah Citation2015; Ariyani and Rahmansyah Citation2015). The local government has also issued local regulations and public policies to address this situation (see, for example, Local Regulation of Lampung Province on Cultural Maintenance of Lampung Number 2/2008; Local Regulation of the Governor of Lampung Province Number 39/Citation2014 on Lampung Language as a Mandatory Local Content Lesson in Elementary, Primary, and Secondary Schools; Local Regulation of the Governor of Lampung Province Number 4/Citation2011 on Maintenance, Development, and Preservation of Lampung Language). Therefore, other technology-based efforts can also be considered to electronically contribute to the Lampung language maintenance. After a context analysis, we conducted interviews with 40 native Lampung people to additionally run a needs analysis. Four questions were asked related to Lampung language maintenance. They were also asked to list 400 commonly used words, with 286 lexicons obtained after data reduction and validation. Their sample responses to the questions are summarized below (our translations).

What do you think about Lampung language maintenance today?

Honestly speaking, I never speak in Lampung language. Neither do my friends. (Informant 5)

More efforts are in need to maintain Lampung language. Although I know it is hard to “insist” people to speak a language. Indonesian dominates, really! (Informant 13)

In the family domain, I use Lampung and Indonesian. (Informant 18)

My grandparents and parents frequently use Lampung in the family domain. I think it is well maintained in the family domain. (Informant 24)

I don’t think it is well maintained. My friends speak in Indonesian and Javanese most of the time. (Informant 35)

Might an Android-based dictionary application be able to address one of Lampung language challenges currently faced by Lampung people in terms of language maintenance?

Yes, we need to provide some space for the inclusion of technology to maintain this local language. (Informant 8)

Why not! I believe we all agree that technology plays a vital role in every part of life. (Informant 15)

I totally believe. Technology should take part in Lampung language maintenance. (Informant 22)

It is one of the supporting efforts for language maintenance. (Informant 33)

Yes, no doubt. Don’t ignore technology; otherwise, the language is forgotten. (Informant 40)

If so, who should be the target audience?

Young generation. To my knowledge, only a very small number of young people speak Lampung language. (Informant 24)

Young people. Like us! (Informant 25)

As we know that Lampung is multicultural and multilingual. I have a lot of friends coming from various ethnic groups. Thus, it is for young people. (Informant 36)

University and school students. (Informant 39)

Anyone in Lampung. If I can suggest, the tourists coming from overseas should be targeted as audience. (Informant 40)

When should it be offered to users?

As soon as possible. (Informant 2)

The day after tomorrow. (Informant 6)

The sooner the better. (Informant 8)

I know it takes a lot of time for an Android-based development, but if you can make it quicker, that is better. (Informant 22)

Soon. I am looking forward to it. (Informant 36)

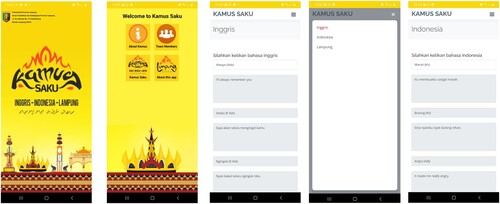

In the product design and development phase, we designed, developed, evaluated, and revised the Android-based dictionary application for smartphones through interviews and expert reviews. The product design with its contents was distributed to the experts team (linguists, cultural experts, IT experts) for review. They were asked to evaluate the design and provide feedback, followed by in-depth interviews. The initial user interface of the Android application is shown in .

The initial product design with its contents was distributed to the team of experts for review to evaluate the product in terms of its content, design, and functionality. They provided us with comments and feedback to improve the product. After that, interviews were carried out to gain further information. A summary of their feedback is given in .

Table 4. Expert judgment.

Once the second phase had been completed, we moved on to the last phase, which was product try-out and evaluation. We evaluated the revised version of the product (see ) through a two-week tryout with 40 student participants and ten traditional Lampung elders. This tryout examined their perceptions of the Android-based application in terms of its design, content, and functionality. illustrates their perceptions.

Figure 3. Android-based dictionary application for Lampung language maintenance (final version). Source: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=io.kodular.apiprahman013.Kamus3Bahasa.

Table 5. Perceptions of Android-based dictionary application for Lampung language maintenance.

gives information about the participants’ perceptions of the Android-based dictionary application for Lampung language maintenance. It can be seen that the first three statements have a similar pattern, in which most participants strongly agreed that the Android-based application is well designed, using representative coloring with a simple yet elegant look. Regarding the adequacy of its content, lexemes, and sentence examples, perceptions are significantly similar. More than half of them agreed on the adequacy of the content and sentence examples; however, less than half agreed on the adequacy of lexemes. Regarding functionality, most agreed on the enjoyment of the Android-based application and strongly agreed on its accessibility. Half of them agreed that this application helps them learn Lampung language, and most agreed that this Android-based dictionary application is useful for Lampung language maintenance. Overall, it is apparent that they welcome and support the development of this Android-based dictionary.

In addition, we also asked them an open-ended question related to their overall perception of the application. Here are several excerpts of their feedback (our translations).

I know it takes a lot of time to include both dialects of Lampung language. However, my suggestion remains the same. Please include both dialects in future improvement. Overall, this application is well done! Keep up the good work! (Participant 1)

Overall, this application looks good. If you can make this application available for iPhone users on App Store, it would be much better. (Participant 6)

Please include more complete lexemes for future improvement! (Participant 8)

It would be much better if you provide users with the pronunciation of each lexeme. (Participant 10)

Nice. I love it. Thank you! (Participant 13)

Cool! Please allow me to share this app with my WhatsApp groups for them to download it! (Participant 16)

5. Discussion

All participants favored the Android-based dictionary application development for Lampung language maintenance. It is widely known that people around the world are now familiar with mobile applications, which have mushroomed and are now the most progressive technology among all technological products (Cassels and Farr Citation2019; Murdianto, Abdillah, and Panjaitan Citation2015). Moreover, even social media now serves a significant role for language preservation and maintenance (Alencar Citation2018; Guskaroska and Elliott Citation2021; Holton Citation2012; Jany Citation2018). In addition, our findings also imply that participants, though not all of them, are native speakers of Lampung, have positive attitudes towards the Lampung language, and are motivated to learn and use the language (see Rusminto, Ariyani, and Setiyadi Citation2018; Widodo, Ariyani, and Setiyadi Citation2018; Wulandari Citation2019). In other words, that the application contributes to language preservation can be demonstrated by the positive feedback received from the users or participants. This finding is in line with Guskaroska and Elliott (Citation2021), who claim that despite digital tools for learning heritage languages still being limited, participants express an interest in using them, with educational apps being preferred (Guskaroska and Elliott Citation2021).

The design and content of the application were revised and reconstructed based on experts’ advice. Among their constructive suggestions, one of them (suggesting both dialects of Lampung language) was impossible to follow up due to time constraints. In addition to time constraints, there is an argument for not including Lampung Nyo, also known as Abung or O-dialect of Lampung language. The Lampung Api dialect is spoken by 979,000 native speakers (Joshua Project Citation2020a), while the Lampung Nyo is spoken by 204,000 native speakers (Joshua Project Citation2020b). Looking at the fact, and after some careful consideration, we finally decided only to include the Lampung Api dialect in this preliminary move.

The participants of the current study have positive perceptions of this Android-based dictionary, believing that this application can contribute to Lampung language maintenance. Today, technology has the potential to preserve, maintain, and teach a minority language, and minority language members can derive much benefit from it (Villa Citation2002). Our Android-based dictionary can contribute to storing written linguistic information of Lampung language electronically (Eisenlohr Citation2004; Wamalwa and Oluoch Citation2013) because, according to Astuti’s (Citation2017) findings, the Lampung language is now at risk of no longer being used due to shifts in language domains, a small number of (native) speakers, and lack of written and printed information. These three facts concern us greatly. Therefore, the development of this Android-based dictionary “attempts to add new linguistic forms or social functions to an embattled minority language with the aim to increase its uses or users” (King 2001, p. 23 as cited in Eisenlohr Citation2004, 21). In so doing, minority language communities now have increased access to resources to expand the domains in which they use their language. Technology and social media platforms can be used to promote the use of indigenous and heritage languages and connect speakers and learners worldwide (Jany Citation2018). Additionally, it is found that technology facilitates electronic mediation practises by intervening in and contributing to ideological constructions that connect linguistic practise, social identities, and sociocultural valuations. This type of electronic mediation results in the creation of artefacts, such as the archiving and documentation of lesser-used language elements (Eisenlohr Citation2004).

6. Conclusion

Technology plays an essential role in minority language preservation and maintenance. The development of an Android-based Lampung language dictionary application for smartphones has successfully contributed to Lampung language maintenance and preservation. Based on the context analysis, it is evident that the Lampung language maintenance through technological inclusion, especially the Android-based application, is underexplored. Our prototype, which received abundant constructive feedback from experts, has been well developed in terms of its design, content, and functionality. The final Android-based application is positively perceived as a form of minority language maintenance and preservation in the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) era.

In addition to Lampung language maintenance in a broader context, the findings of this study have several implications. The Android-based dictionary can be used as a tool for preserving and maintaining Lampung language in a more specific context, in educational settings, as a resource for learning. In other words, this can be used in either a formal or informal learning setting. Technology can be developed in harmony with humans and education (Hussin Citation2018). It is believed that technology makes quite an impact on education in a broad sense (Hariharasudan and Kot Citation2018) and language learning in a narrower sense (Samira Citation2011). Moreover, technology in the form of a smartphone, for example, can boost one’s creative and critical thinking to increase one’s communication and collaboration abilities (Ramamuruthy and Rao Citation2015). In addition, the development of a broader range of digital tools for minority language maintenance and preservation is critical to assisting language maintenance efforts (Guskaroska and Elliott Citation2021), with a greater emphasis on familiar and user-friendly digital tools (Jany Citation2018). Local languages, particularly in the Indonesian context, have lost their significance and functions due to Indonesian's hegemony. Maintaining a local language, on the other hand, is not impossible. Indonesian, as the national language, will inevitably have a much more dominant position and function than the Lampung language. As a result, efforts to preserve the Lampung language frequently collide with efforts to foster and develop Indonesian as the national language, and so the Lampung language cannot be maintained and preserved in the same way that Indonesian can (Rusminto et al. Citation2021). Technology can be used to support informal language learning online, self-directed learning that takes place outside of the classroom and is unrelated to any courses or institutions is poorly structured, and is frequently unintentional/coincidental (Trinder Citation2017).

However, the current project does have its limitations: (1) the focus is on one dialect, Lampung Api (also known as Pesisir or A-dialect); (2) a limited number of lexicons; (3) it is not equipped with the Lampung language pronunciation; and (4) a limited number of participants. Therefore, future studies should include both dialects (A- and O-dialects) with more lexicons equipped with pronunciations. A more significant number of participants should be included in future studies to make more valid and reliable findings. Finally, we believe that this study is undoubtedly only a beginning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Farida Ariyani

Farida Ariyani is an Associate Professor in the Department of Language Education and Arts at Universitas Lampung, Bandar Lampung, Indonesia. She is also a cultural activist who advocates for the preservation of local languages and cultures. Lexicology, lexicography, sociolinguistics, the teaching of Indonesian language and literature, as well as the education of indigenous languages and cultures, are among her research interests. She would love to hear from you via email at [email protected].

Gede Eka Putrawan

Gede Eka Putrawan is a lecturer at the Department of Language Education and Arts at Universitas Lampung in Indonesia. His research interests include translation, translation and ELT, translanguaging, and language maintenance. He can be reached via email at [email protected].

Afif Rahman Riyanda

Afif Rahman Riyanda is a lecturer at Universitas Lampung, where he teaches in the Information Technology Education Study Program. He is currently pursuing a PhD degree from Padang State University in the subject of technology and vocational education. He has been involved in research on technology and vocational education, multimedia development, and information technology education in recent years. To reach him, write an email to [email protected].

As. Rakhmad Idris

As. Rakhmad Idris is a researcher of the Lampung Provincial Language Office, the Agency for Language Development and Cultivation of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, Indonesia. In 2017, he earned a doctorate from the University of Indonesia. His scholarly interests are primarily in ancient texts and literature. Additionally, he is engaged in the inventory of religious manuscripts in Indonesia. He would be quite grateful to receive an email from you at [email protected].

Lisa Misliani

Lisa Misliani is a technical reviewer of language and literature at the Lampung Provincial Language Office, the Agency for Language Development and Cultivation of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, Indonesia. She is particularly interested in textual and discourse analysis, as well as literary studies. She is also actively involved in Indonesian philological studies. Her email address is [email protected].

Ryzal Perdana

Ryzal Perdana is a lecturer in the Department of Educational Sciences at Universitas Lampung. He is actively involved in both academic and non-academic activities. He serves as an editor and reviewer for a number of national and international journals. Education and technology, learning and critical thinking, developmental research, and teacher professional development are some of his research interests. He may be reached at [email protected].

References

- Abidin, Z., Permata, I. Ahmad, and Rusliyawati. 2021. “Effect of Mono Corpus Quantity on Statistical Machine Translation Indonesian – Lampung Dialect of Nyo.” Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1751: 12036. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1751/1/012036.

- Abidin, Z., P. Permata, and F. Ariyani. 2021. “Translation of the Lampung Language Text Dialect of Nyo into the Indonesian Language with DMT and SMT Approach.” INTENSIF: Jurnal Ilmiah Penelitian Dan Penerapan Teknologi Sistem Informasi 5 (1): 58–71. https://doi.org/10.29407/intensif.v5i1.14670.

- Alencar, A. 2018. “Refugee Integration and Social Media: A Local and Experiential Perspective.” Information Communication and Society 21 (11): 1588–1603. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1340500.

- Ariyani, F. 2015. Kamus dwi bahasa Indonesia Lampung dialek Way Kanan [A Bilingual Dictionary of Indonesian – Lampung Way Kanan Dialect]. Dinas Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Pemkab. Way Kanan.

- Ariyani, F., B. Kadaryanto, and S. Rahmansyah. 2015. Percakapan sehari-hari dengan tiga bahasa: Bahasa Lampung – Indonesia – Inggris [Daily Conversation in Three Languages: Lampung – Indonesian – English]. Graha Ilmu.

- Ariyani, F., and S. Rahmansyah. 2015. Buku saku percakapan sehari-hari bahasa Lampung [Daily Conversation in Lampung Language: A Pocket Book], edited by Bakhril and Djufri. Majelis Penyimbang Adat Lampung Kabupaten Way Kanan.

- Ariyani, F., N. E. Rusminto, and A. B. Setiyadi. 2018. “Language Learning Strategies Based on Gender.” Theory and Practice in Language Studies 8 (11): 1524–1529. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0811.19.

- Ariyani, F., N. Udin, N. N. Wetty, I. Hilal, and H. M. Junaiyah. 1999. Kamus bahasa Indonesia-Lampung Dialek A (A-Z) [A Dictionary of Indonesian-Lampung Dialect A (A-Z)]. Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa.

- Astuti, I. K. 2017. Vitality of Lampung Language and its Maintenance Efforts Through Cultural Exposure in Educational Program. Semarang: Diponegoro University.

- Aziz, I., and H. Harafani. 2016. “Aplikasi Kamus Bahasa Betawi Berbasis Android Menggunakan Metode Sequencial Search.” Penelitian Ilmu Komputer Sistem Embedded Dan Logic 4 (1): 27–35. https://doi.org/10.33558/piksel.

- Bettinson, M., and S. Bird. 2017. “Developing a Suite of Mobile Applications for Collaborative Language Documentation.” Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on the Use of Computational Methods in the Study of Endangered Languages, 156–164. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/w17-0121.

- Bosch, S. E., and M. Griesel. 2020. “Exploring the Documentation and Preservation of African Indigenous Knowledge in a Digital Lexical Database.” Lexikos 30: 1. https://doi.org/10.5788/30-1-1603.

- Cassels, M., and C. Farr. 2019. “Mobile Applications for Indigenous Language Learning: Literature Review and App Survey.” Working Papers of the Linguistics Circle of the University of Victoria 29 (1): 1–24. https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/WPLC/article/view/18769

- Cha, S. S., and B. K. Seo. 2018. “Smartphone Use and Smartphone Addiction in Middle School Students in Korea: Prevalence, Social Networking Service, and Game Use.” Health Psychology Open 5: 1. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102918755046.

- Cohn, A. C., and M. Ravindranath. 2014. “Local Languges in Indonesia: Language Maintenance or Language Shift?” Linguistik Indonesia 32 (2): 131–148.

- Dong, H., F. Yang, X. Lu, and W. Hao. 2020. “Internet Addiction and Related Psychological Factors Among Children and Adolescents in China During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) Epidemic.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00751.

- Eisenchlas, S. A., A. C. Schalley, and G. Moyes. 2016. “Play to Learn: Self-Directed Home Language Literacy Acquisition Through Online Games.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 19 (2): 136–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2015.1037715.

- Eisenlohr, P. 2004. “Language Revitalization and New Technologies: Cultures of Electronic Mediation and the Refiguring of Communities.” Annual Review of Anthropology 33 (1): 21–45. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143900.

- Enthoven, C. A., J. R. Polling, T. Verzijden, J. W. L. Tideman, N. Al-Jaffar, P. W. Jansen, H. Raat, L. Metz, V. J. M. Verhoeven, and C. C. W. Klaver. 2021. “Smartphone Use Associated with Refractive Rrror in Teenagers.” Ophthalmology 128 (12): 1681–1688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.06.016.

- Fishman, J. A. 1964. “Language Maintenance and Language Shift as a Field of Inquiry: A Definition of the Field and Suggestions for its Further Development.” Linguistics 2 (9): 32–70. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1964.2.9.32.

- Frawley, W. J. (Ed.). 2003. International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford University Press.

- Glottolog. 2020. “Lampungic.” In edited by H. Hammarström, R. Forkel, M. Haspelmath, & S. Nordhoff. GitHub. https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/lamp1241.bigmap.html#6/-4.764/105.217

- Gonçalves, S., P. Dias, and A.-P. Correia. 2020. “Nomophobia and Lifestyle: Smartphone Use and its Relationship to Psychopathologies.” Computers in Human Behavior Reports 2: 100025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2020.100025.

- Guskaroska, A., and T. Elliott. 2021. “Heritage Language Maintenance Through Digital Tools in Young Macedonian Children – an Exploratory Study.” Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education 00 (00): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595692.2021.1907329.

- Hariharasudan, A., and S. Kot. 2018. “A Scoping Review on Digital English and Education 4.0 for Industry 4.0.” Social Sciences 7: 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7110227.

- Holton, G. 2012. “The Role of Information Technology in Supporting Minority and Endangered Languages.” The Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages, 371–400. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511975981.019.

- Hussin, A. A. 2018. “Education 4.0 Made Simple: Ideas for Teaching.” International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies 6 (3): 92–98. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.6n.3p.92.

- Imron, A. 2021. “The Development of Iqra’ Lampung Script Teaching Materials for Primary School Levels in Bandar Lampung City.” International Journal of Educational Studies in Social Sciences (IJESSS) 1 (1): 38–43. https://doi.org/10.53402/ijesss.v1i1.5.

- Jany, C. 2018. “The Role of New Technology and Social Media in Reversing Language Loss.” Speech, Language and Hearing 21 (2): 73–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/2050571X.2017.1368971.

- Joshua Project. 2020a. Language: Lampung Api, Languages. Colorado: Joshua Project. Accessed 26 March 2020. https://joshuaproject.net/languages/ljp

- Joshua Project. 2020b. Language: Lampung Nyo, Languages. Colorado: Joshua Project. Accessed 26 March 2020. https://joshuaproject.net/languages/abl

- Kasema, L. O., S. R. Sentinuwo, and A. M. Sambul. 2019. “Aplikasi Kamus Bahasa Daerah Pasan Berbasis Android.” Jurnal Teknik Informatika 13 (2): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.35793/jti.13.2.2018.22489.

- Katubi, 2006. “Lampungic Languages: Looking for New Evidence of the Possibility of Language Shift in Lampung and the Question of Its Reversal.” In Tenth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics (10-ICAL), 17-20 January, 1–10. Puerto Princesa: Linguistic Society of the Philippines and SIL International.

- Koen, R., and S. J. Bulan. 2018. “Aplikasi Kamus Bahasa Helong Berbasis Android.” Jurnal Teknologi Terpadu 4 (2): 49–55.

- Little, S. 2019. “‘Is There an App for That?’ Exploring Games and Apps among Heritage Language Families.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40 (3): 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2018.1502776.

- Little, S. 2020. “Social Media and the Use of Technology in Home Language Maintenance.” In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development, 257–273. Berlin: De Gruyter. doi: 10.1515/9781501510175-013.

- Local Regulation of Lampung Province on Cultural Maintenance of Lampung, Pub. L. No. 2. 2008.

- Local Regulation of the Governor of Lampung Province on Lampung Language as a Mandatory Local Content Lesson in Elementary, Primary, and Secondary Schools, Pub. L. No. 39. 2014.

- Local Regulation of the Governor of Lampung Province on Maintenance, Development, and Preservation of Lampung Language, Pub. L. No. 4. 2011.

- Murdianto, M., F. A. Abdillah, and F. Panjaitan. 2015. “Dictionary of Prabumulih Language-Based Android.” In The 4th ICIBA 2015, International Conference on Information Technology and Engineering Application, 20–21 February 2015, 230–235. Palembang.

- Musgrave, S. 2014. “Language Shift and Language Maintenance in Indonesia.” In Language, Education and Nation-building, 87–105. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/9781137455536_5.

- Mustika, I. W. 2020. “Exploring the Functions of Sakura Performance art in West Lampung, Indonesia.” SAGE Open 10 (4): 215824402097302. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020973027.

- Ngo, H. T. P., and A. Eichelberger. 2020. “Learning Ecologies in Online Language Learning Social Networks: A Netnographic Study of EFL Learners Using Italki.” International Journal of Social Media and Interactive Learning Environments 6: 181–199.

- Palviainen, Å. 2020. “Future Prospects and Visions for Family Language Policy Research.” In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development, 236–254. Berlin: De Gruyter. doi: 10.1515/9781501510175-012.

- Pratama, A. R. 2017. “Exploring Personal Computing Devices Ownership Among University Students in Indonesia.” IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, 504: 835–841. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59111-7.

- Pratama, A. R. 2018. “Investigating Daily Mobile Device Use Among University Students in Indonesia.” IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 325: 1. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/325/1/012004.

- Putrawan, G. E., and B. Riadi. 2020. “English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Learners’ Predominant Language Use for Online Informal Learning Activities Through Smartphones in Indonesian Context.” Universal Journal of Educational Research 8 (2): 695–699. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.080243.

- Putri, N. W. 2018. “Pergeseran Bahasa Daerah Lampung Pada Masyarakat Kota Bandar Lampung (Lampung Language Shift in Bandar Lampung City).” Prasasti: Journal of Linguistics 3 (1): 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- Ramamuruthy, V., and S. Rao. 2015. “Smartphones Promote Autonomous Learning in ESL Classrooms.” Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Technology 3 (4): 23–35.

- Riagáin, P. 1994. “Language Maintenance and Language Shift as Strategies of Social Reproduction.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 15 (2–3): 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.1994.9994565.

- Richey, R. C., and J. D. Klein. 2005. “Developmental Research Methods: Creating Knowledge from Instructional Design and Development Practice.” Journal of Computing in Higher Education 16 (2): 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02961473.

- Richey, R. C., and J. D. Klein. 2014. “Design and Development Research.” In Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology, edited by J. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. Elen, and M. J. Bishop, 141–150. New York, NY: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3185-5_12.

- Rusminto, N. E., F. Ariyani, and A. B. Setiyadi. 2018. “Learning a Local Language at School in Indonesian Setting.” Journal of Language Teaching and Research 9 (5): 1075–1083. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0905.23.

- Rusminto, N. E., F. Ariyani, A. B. Swtiyadi, and G. E. Putrawan. 2021. “Local Language vs. National Language: The Lampung Language Maintenance in the Indonesian Context.” Kervan 25 (1): 287–307.

- Samira, H. 2011. “The Effects of ICT on Learning/Teaching in a Foreign Language.” In 4th International Conference ICT for Language Learning, 20–21 October. Florence.

- Schreyer, C. 2011. “Media, Information Technology, and Language Planning: What Can Endangered Language Communities Learn from Created Language Communities?” Current Issues in Language Planning 12 (3): 403–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2011.604965.

- Solleveld, F. 2020. “Expanding the Comparative View.” Historiographia Linguistica 47 (1): 52–82. https://doi.org/10.1075/hl.00062.sol.

- Stahlberg, S. 2021. “Internet-Based Resources and Opportunities for Minority and Endangered Languages.” Tehlikedeki Diller Dergisi 11 (19): 418–438.

- StatCounter. 2020. Mobile Operating System Market Share in Indonesia. OS Market Share.

- Statista. 2020. Number of Smartphone Users in Indonesia from 2011 to 2022. Technology & Telecommunications.

- Sudirman, A. M. 2019. “Language Kinship Between Komering Variation and Lampung Menggala.” SASDAYA: Gadjah Mada Journal of Humanities 3 (1): 1. https://doi.org/10.22146/sasdayajournal.43883.

- Sujadi, F. 2012. Lampung sai bumi ruwa jurai [Lampung is the Descendant of Two Ancestors]. Yogyakarta: Cita Insan Madani.

- Sunarti, I., S. Sumarti, B. Riadi, and G. E. Putrawan. 2019. “Terms of Address in the Pubian Dialect of Lampung (Indonesia).” Kervan 23 (2): 237–264.

- Thomas, K. S. K. 2014. “Revitalisation of the Performing Arts in the Ancestral Homeland of Lampung People.” Sumatra. Wacana SeniJournal of Arts Discourse 13: 29–55.

- Trinder, R. 2017. “Informal and Deliberate Learning with New Technologies.” ELT Journal 71 (4): 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccw117.

- van den Akker, J., K. Gravemeijer, S. McKenney, and N. Nieveen. 2006. “Introducing Educational Design Research.” In Educational Design Research, edited by J. Van den Akker, K. Gravemeijer, S. McKenney, and N. Nieveen. Oxon: Routledge.

- Villa, D. J. 2002. “Integrating Technology into Minority Langugage Preservation and Teaching Efforts: An Inside Job.” Language Learning and Technology 6 (2): 92–101.

- Wamalwa, E. W., and S. B. J. Oluoch. 2013. “Language Endangerment and Language Maintenance: Can Endangered Indigenous Languages of Kenya be Electronically Preserved?” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 3 (7): 258–265.

- Warganegara, A., and P. Waley. 2021. “The Political Legacies of Transmigration and the Dynamics of Ethnic Politics: a Case Study from Lampung.” Indonesia. Asian Ethnicity, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2021.1889356.

- Widodo, M., F. Ariyani, and A. B. Setiyadi. 2018. “Attitude and Motivation in Learning a Local Language.” Theory and Practice in Language Studies 8 (1): 105–112. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0801.14.

- Wirawan, I. M. A., and I. B. M. L. Paryatna. 2018. “The Development of an Android-Based Anggah-Ungguhing Balinese Language Dictionary.” International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies 12 (1): 4–18. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v12i1.7105.

- Wright, S. 2018. “Planning Minority Language Maintenance: Challenges and Limitations.” In The Oxford Handbook of Endangered Languages, edited by K. L. Rehg and L. Campbell, Issue August, 636–656. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wulandari, C. 2019. “Maintenance of Lampung Language in Padang Cermin District.” Teknosastik 16 (2): 73–79.

- Xu, K. 2020. “The Development of Mongolian as a Minority Language in Digital Spaces.” Journal of Contemporary Educational Research 4 (2): 73–76. https://doi.org/10.26689/jcer.v4i2.1016.