ABSTRACT

This paper relies on the center–periphery division in the production of science and technology to discuss the glyphosate debate in Colombia as an instance of Oreskes and Conway’s tobacco strategy. The paper highlights some particularities in the implementation of the strategy in a peripheral context. Specifically, it shows that the debate here does not revolve around a product’s science and risks, but mainly around the results, consequences, and legal status of a government peace policy. To achieve this, the paper appeals to a mixed methodological approach integrating intensive methods to analyze traditional mass media and extensive methods to analyze social media.

RESUMO

Este artigo se baseia na divisão centro-periferia na produção de ciência e tecnologia para discutir o debate sobre o glifosato na Colômbia como uma instância da estratégia de tabaco de Oreskes e Conway. O artigo destaca algumas particularidades na implementação da estratégia em um contexto periférico. Especificamente, mostra que o debate aqui não gira em torno da ciência e dos riscos de um produto, mas principalmente em torno dos resultados, consequências e status legal de uma política governamental de paz. Para conseguir isso, o artigo recorre a uma abordagem metodológica mista que integra métodos intensivos para analisar os meios de comunicação de massa tradicionais e métodos extensivos para analisar as mídias sociais.

RESUMEN

Este artículo se apoya en la división centro-periferia en la producción de ciencia y tecnología para discutir el debate sobre el glifosato en Colombia como una instancia de la estrategia del tabaco de Oreskes y Conway. El documento destaca algunas particularidades en la implementación de la estrategia en un contexto periférico. Específicamente, muestra que el debate aquí no gira en torno a la ciencia y los riesgos de un producto, sino principalmente a los resultados, consecuencias y estatus legal de una política de paz gubernamental. Para lograr esto, el documento apela a un enfoque metodológico mixto que integra métodos intensivos para analizar los medios de comunicación tradicionales y métodos extensivos para analizar las redes sociales.

PALAVRAS CHAVE:

PALABRAS CLAVE:

1. Introduction

The “tobacco strategy” is a label employed by Oreskes and Conway in their book Merchants of Doubt (Citation2010) to describe the approach of a handful of scientists, politicians, and policy makers to influence public opinion in the United States regarding environmental and health issues. They affirm that the same strategy has been used for several subjects besides tobacco, such as asbestos, climate change, secondhand smoking, acid rain and the ozone hole, and it is upheld by the same individuals and institutions, such as conservative think tanks, private corporations, foundations, and the fossil fuel industry. Their main point is that the strategy targets science by relying heavily on scientists to benefit certain industries, creating doubt regarding the negative impacts of their products. This is what Oreskes and Conway understand by merchandising doubt – the application of a strategy (i.e. the tobacco strategy) to keep controversies alive through scientific means, or means that look scientific, so scientific consensus turns into a political controversy concerning environmental and health issues.

It is not clear from Oreskes and Conway’s examples nor from wider discussions about their ideas in STS circles whether this strategy to merchandise doubt has been replicated in other places outside the United States and how. In her 2015 Patten Lecture, for example, Oreskes (Citation2015) suggests that this is in fact a global trend led by the United States but does not give details about other contexts. Based on the well-known center–periphery division in the production of science and technology (Kreimer Citation2019), which identifies the United States as one of those centers, we intend to show that this strategy to merchandise doubt has been replicated in peripheral contexts outside the United States. We start by presenting what we call the strategy’s structural pattern and goal. From there, we build the argument that the strategy does not show qualitatively significant differences in its transit from the center to the periphery concerning its structural pattern, but it does concerning its goal.

We take the glyphosate debate in Colombia as a case study, with a focus on traditional mass media (such as radio shows and newspapers) and social media (such as Twitter). However, our analysis is not about licit or illicit crops, not even about glyphosate and its uses. We incorporate historical, analytical, and empirical elements about glyphosate to deal with another problem, the one just mentioned – how doubt is merchandised in the periphery. Our purpose is to indicate that the STS conceptual and methodological tools developed to study this type of controversies in the center are also adequate in the periphery. We find evidence that the same structural pattern described by Oreskes and Conway reappears in the Colombian case. Yet whereas the goal in the center has a wider scope – to neutralize what is seen as government intervention on institutions, markets and freedom- the goal in the periphery has a narrower scope, to undermine the legal status and public support of specific government policies, a peace policy in this case. We are hopeful that this analysis will help to motivate further individual and comparative studies about how merchandising doubt takes place in other peripheral contexts.

2. The strategy’s structural pattern and goal

In Oreskes and Conway’s description, the tobacco strategy relies on four main, sequential procedures to merchandise doubt. This is what we call the strategy’s structural pattern, since these procedures and their sequence reappear in the different examples studied in the book.

The first is to fight science with science. An industry may have evidence both that its product is bad/problematic for a health or environmental issue, and that there is external scientific consensus about it. Yet its response is to deny the existence or reliability of such evidence. Instead, it hires a public relations firm to challenge scientific evidence and defend the product in the public sphere. This procedure allows doubt to prevail about the product’s impacts.

The second is to convince mass media that there is a controversy on the issue, particularly by appealing to journalists’ responsibility to provide a balanced report of the facts, giving equal weight to both sides. This procedure attempts to persuade mass media’s owners and journalists that there is another point of view, in order to disseminate and promote information that helps to reinforce the industry’s position.

The third is to organize a group of experts that can serve as witnesses and support a case in favor of an industry’s product in a public debate, court, or any other relevant context. This procedure includes investments in research, academic journals, and other types of publications, which may give the idea that expert knowledge has been produced.

The last one is to use politics. This procedure consists of organizing a network of think tanks, foundations, and other organizations to disseminate favorable ideas about the product. The procedure may also include accusations of antinationalistic agendas (e.g. socialism, communism) for those in disagreement, appeals to the high costs to solve specific problems related to the product, or confidence in the power of future technology to fix any issue that may arise.

Oreskes and Conway provide a general overview of the tobacco strategy. Christensen (Citation2008) relies on this, reinterpreting it from the viewpoint of ignorance studies – specifically, agnotology, a perspective congenial to Oreskes and Conway's (Citation2008) earlier discussion. Christensen offers a framework, both chronological and analytical, to understand how the journalistic values of objectivity, fairness, balance, and facts help the strategy to enlist journalism as an accomplice in the cultural production of ignorance, even if unwillingly or unwittingly. He identifies four phases.

The first is once again to fight science with science. In this phase, the tobacco industry funded scientific research on cigarette smoking and cancer. The aim was to feed information to journalists to argue that the problem was taken seriously, though there was evidence of other factors related to lung cancer. This phase lasted until 1964, when the first Surgeon General’s report connected public evidence and internal evidence from the industry concerning the presence of carcinogens in cigarette smoke.

The second phase follows the first Surgeon General’s report and the first warning labels mandated for cigarettes, when it was harder to provide evidence denying the incidence of smoking as a primary factor in lung cancer and other diseases. The industry then focused more on spreading doubt on specific facts, appealing to journalistic values to present the other side of the story in each case. It was then possible to keep the controversy alive, without necessarily facing or fighting new facts.

The third phase starts in the 1980s and goes through the 1990s. The aim was to undermine science as a point of reference to establish facts and truths. Instead of casting doubt on specific scientific research, the attention turned to entire fields and methods, such as epidemiology, risk analysis, statistics, modeling, and forecasting. The intention was not, for instance, to show that some piece of evidence could be suspicious, but rather that a whole epidemiological model about the risks of cigarette smoking could be biased by the researchers’ interests and agendas.

The last phase started in the 2000s. It is characterized by the industry’s apparent capitulation to the overwhelming evidence against its product. The controversy has ceased, and the industry finally recognizes that cigarette smoking may cause cancer and heart disease, among other diseases, even death. Yet this comes with a new approach. The product is indeed risky, but the industry now appears as a responsible manufacturer that provides the necessary evidence for the customer to make informed decisions on its consumption. The responsibility does not lie with the industry anymore, but with the costumer, who has enough information to decide.

To sum up, Oreskes and Conway and Christensen share the following points concerning the strategy’s structural pattern. First, there is not a rejection of science, but an opportunistic use of it. The merchant of doubt still appeals to science, either to confirm his own viewpoint or to undermine those harming his product. Second, mass media and other ways to create public opinion are constituent, not accidental, parts of the strategy. They function as tools to either display the industry’s stand on the subject or simply spread doubt on what should be taken as the correct stand on the subject. Journalism and its epistemic values help to sustain a general environment of confusion. Finally, the strategy does not attempt to uncover any facts or truths, but to build a strong social and political endorsement of the industry’s view. This endorsement is constructed through private enterprises or public debate. The point is to instill the idea that problems related to the product are not in fact problems. They do not exist or can be easily solved through public policies, technology, or more informed citizens.

But what is the goal in applying this structural pattern? We have already mentioned it – the goal of merchandising doubt is to keep controversies alive through scientific means or means that look scientific, so scientific consensus turns into a political controversy. In this way, rather than addressing the environmental and health issues associated with a product, the structural pattern enables an industry to protect its product from public and legal scrutiny. The industry applies the strategy’s procedures to avoid, for instance, negative publicity for its product or even retiring it completely from a market. Yet as Oreskes (Citation2015) explains in her 2015 Patten Lecture regarding the United States, the goal has never been commercial, but political. The merchants of doubt were worried about government intervention in these industries to protect people from dangers because this implied to them that the government could also start regulating institutions, markets, and lives in general. The tobacco strategy was understood as a way to face this threat, which would lead to higher government control and the loss of individual liberties and freedom.

3. Methods

We intend to explore how doubt is merchandised in a peripheral context. For this, we analyze a particular case, that is, how the tobacco strategy becomes intricated in the glyphosate debate in Colombia and what it implies. We rely on a mixed methodological approach that combines two complementary lines of research – one intensive and another extensive.

The intensive line focuses on traditional mass media by discussing some of journalist María Isabel Rueda’s (Citation2019) opinion pieces about glyphosate in newspapers and radio shows. We chose María Isabel Rueda, a very prestigious journalist with a long history in traditional Colombian media such as newspapers, radio, and television, because she is regarded as a key figure to shape public opinion about political matters in the country, with several national prizes for her work in this area. Hence, we hypothesized that her 2019 opinion pieces could be an appropriate object for our study, due to the public debate that they provoked. We appealed to documentary research to identify the relevant pieces, and discourse analysis to understand how they become part of the glyphosate debate and how they exemplify an instantiation of the tobacco strategy.

The extensive line focuses on social media by employing digital methods to track the interactions and connections surrounding Rueda’s opinion pieces. The article here takes issue mapping (Marres Citation2015) as its main methodological orientation. We use Twitter as the main source of information.

Twitter is one of the most popular social media. By 2022, it had almost 400 million users worldwide, with about 4.3 million monthly active users in Colombia (Revista P&M Citation2022), and had become a site where journalists, politicians, and academics could follow the flow of news or the development of various topics and dialogues. According to Burgess and Baym (Citation2020), there is a general sense that Twitter is important, being instrumental in the propagation of disinformation campaigns, using troll farms, bots, and other technologies to influence political campaigns. But it is also important as a source of information for academic studies.

The present analysis combines Social Network Analysis (SNA) visualization tools with a hermeneutic approach to individual tweets. We collected data using the web scraper Parsehub and used Twitter’s advanced search function to look for different iterations of glyphosate in the months surrounding Rueda’s Citation2019 opinion pieces. We captured several of the specific markers, such as hashtags and URLs. Hashtags are valuable to follow conversations and identify important actors in a controversy (Bruns and Burgess Citation2015). Including a hashtag in a tweet is a statement of participation in a discussion. Platform features shape how networks are organized (Rogers Citation2013) and enable flexibility (Highfield Citation2018). We draw attention to both ambiguous uses of the same hashtag, different contexts, and the modularity of hashtag use (Procter, Voss, and Lvov Citation2015).

As several works within the STS community have suggested (Breslin et al. Citation2020; Marres and Gerlitz Citation2016), Twitter allows us to explore not only the production of narratives based on measures centered on the popularity of actors and their statements about themselves, but also to detect co-occurrences between keywords as signs of thematic and social convergences. We therefore track links between actors and digital objects such as hashtags and URLs. We employed Gephi to analyze the data (Bastian, Heymann, and Jacomy Citation2009) and ANTconc to read the uses of the term glyphosate within the data (Anthony Citation2020). We collected 122.846 individual tweets in Spanish containing the words glyphosate. To create the visualizations, we used ForceAtlas2, and to identify the communities we employed the modularity class module in Gephi. These strategies help to visualize the emerging thematic clusters and the characterization of discursive repertoires. The objective is to track doubt-creation maneuvers on Twitter and to provide a more comprehensive view of the consolidation of the tobacco strategy in some discursive practices surrounding Rueda’s opinion pieces.

4. The glyphosate debate in Colombia

On October 26, 2022, euthanasia was performed on retired police sergeant, Gilberto Ávila, 59, a practice that is already decriminalized in Colombia for those suffering intense physical or psychological pain due to an injury or incurable disease. Ávila requested this procedure because of the juvenile Parkinson’s disease that he had been suffering for 16 years and which, in his words, was glyphosate’s fault. Since 1987 he worked in the Police’s Anti-Narcotics Directorate and participated in the glyphosate spraying program to control illicit crops in different areas of the country: “we had to guard the terrain so that the criminals did not hit the planes and helicopters (…) the chemical fell on us.” According to Ávila, there was a “high probability that it was caused by glyphosate, since two other colleagues are sick with the same thing. We were subjected to the same spraying conditions.” Before his death, Ávila appealed to the authorities so his story would not be repeated and no other police officer would suffer the same fate (El Espectador Citation2022; Infobae Citation2022).

In Colombia, glyphosate spraying programs to control illicit crops originated in 1984, when the National Government sought to eradicate marijuana crops in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Paradoxically, not only did the number and yield per hectare increase, but cultivation moved to other regions. By 1988, Colombia was the main exporter of marijuana to the United States (Tokatian Citation1992). The repression thus served to incentivize the business.

In 1989, the U.S. Government changed its policy to reduce the entry of cocaine into its territory and provided support to local governments in the eradication of coca cultivation, its processing, and commercialization. Fumigation in Colombia was designed to eliminate coca and poppy cultivation (Torres-González and Rodríguez-Martínez Citation2022). Over the years, aerial spraying with glyphosate increased considerably, but successive spraying failed to reduce the areas planted with coca. This called into question the efficacy of this strategy (Weir Citation2005). Moreover, it brought anti-drug policy into conflict with the right to health and the environment.

The debate has turned around the convenience of spraying. According to a report prepared by CESED Uniandes (Citation2021), two positions can be identified. Those who defend the spraying claim that it helps to combat drug trafficking and illegal armed groups, reduce the number of cultivated hectares, avoid deaths caused by overdoses, improve security, and favor social and environmental conditions. They also deny that it is a dangerous substance, pointing out scientific studies showing glyphosate’s low or no toxicity, and its lower cost in lives when compared to manual eradication. Those who oppose it affirm that the program directly affects the most vulnerable, intensifying social conflict in the sprayed areas, and its effects on the drug trafficking business are very marginal. They highlight that in aerial spraying the concentration of glyphosate is almost three times higher than in conventional agriculture and present research showing that its use generates health issues. They insist that spraying has direct and indirect environmental effects on the soil, sediments, and bodies of water.

In 2003, two lawsuits were filed seeking the suspension of the program and requesting that the Colombian government adopt measures to prevent damage to the environment and harmful effects on public health. Although the lawsuits were adverse to the Colombian administration, the Government, led by President Álvaro Uribe Vélez, with the support of the U.S. Government, continued to defend the program’s efficacy (Rodríguez Citation2004; Weir Citation2005). The controversy led to an increase in studies related to glyphosate toxicity risk assessment and monitoring in the country (Bolognesi et al. Citation2009; Sanin et al. Citation2009; Solomon, Marshall, and Carrasquilla Citation2009; Varona et al. Citation2009).

In 2008, the program was once again at the center of the debate. The Ecuadorian Government filed a lawsuit against Colombia at the International Court of Justice for damages caused to its inhabitants and its territory by the spraying on the border. The dispute lasted five years and concluded with an agreement of economic compensation. This renewed discussions on the precautionary principle, the notion of risk, human rights, and environmental regulation (Ángel-Botero and Babrow Citation2013; Solano Citation2014; Torres-González and Rodríguez-Martínez Citation2022).

The payment of the compensation did not lead to a change in domestic policy regarding the use of glyphosate in the fight against illicit crops, and the Colombian Government insisted on the program. However, in 2015, the National Narcotics Council, a state entity that advises the National Government on the formulation, coordination, and monitoring of anti-drug policy, ordered the suspension of aerial spraying throughout the national territory. This occurred after WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified glyphosate as a substance that is probably carcinogenic (Idrovo Citation2015; Lozano Citation2018). Two years later, in 2017, the Colombian Constitutional Court suspended the program and ruled that any decision on the matter must be based on objective and conclusive evidence demonstrating the absence of harm to health and the environment (Torres-González and Rodríguez-Martínez Citation2022).

5. Merchandising doubt – the tobacco strategy enters the glyphosate debate

As just said, in 2017, the Constitutional Court, the highest tribunal in Colombia regarding constitutional matters, established a regulation for the use of glyphosate due to its health and environmental risks. This regulation included six conditions that government agencies had to fulfill to restart aspersions with the herbicide. In 2019, the Court reviewed the 2017 sentence and decided that the conditions were still valid, so the use of glyphosate remained forbidden, unless the conditions were met. What happened between 2017 and 2019 that led the Court to review its previous sentence, even though it finally modified nothing? We argue that the tobacco strategy entered the debate. It merchandised doubt about glyphosate’s health and environmental risks with the political goal of undermining the legal status and the public support of a government policy – the recent 2016 Peace Agreements signed between the National Government, headed by President Juan Manuel Santos, and the guerrilla group FARC-EP.

These agreements did not contain an explicit provision to eliminate aerial spraying with glyphosate. However, the need to implement comprehensive strategies to replace illicit crops and promote environmental recovery was established. This implied seeking alternatives to aerial spraying as the main method of controlling illicit crops. Several programs were launched, including the Comprehensive National Program for the Substitution of Illicitly Used Crops (PNIS), the Comprehensive Community Plans for Substitution and Alternative Development (PISDA) and the Formalization Program for Substitution (Kroc Institute Citation2018). By 2017, 54,027 families had voluntarily joined the substitution program and by 2018 the figure reached 99,097 (Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito Citation2019).

Although the interruption of spraying had been enthusiastically received in the country’s major coca-producing territories with the agreements, the transition from the Santos administration to the Duque administration in August 2018 produced an important change in Colombian drug policy – the revival of the glyphosate debate. Before the election, and with the backing of the U.S. Government, presidential candidate Iván Duque and his party insisted on the need to use glyphosate to reduce the supply of illicit crops. After the election, the Duque administration soon asked the Court to moderate the 2017 sentence, which was the main obstacle. This had a huge impact on public debate during 2018 and 2019. Vallejo Mejía and Agudelo-Londoño (Citation2019) have shown that glyphosate became a recurrent topic in Colombian periodicals, with detractors and supporters employing different rhetoric strategies to persuade public opinion of its harms and benefits respectively. In this context, María Isabel Rueda’s case stood out among the others.

She published a piece in El Tiempo, the most influential newspaper in the country, titled “Glifosato: ¡pongámosle sensatez!” (“Glyphosate: let’s put some sense into it!”) (Rueda Citation2019). The piece, which appeared online on June 22, 2019 (June 23 on paper), asked whether glyphosate was harmful to health. It argued that there was no conclusive evidence to make such a claim, and for that reason, the Santos administration’s decision not to use it, even before the Court sentence, relied on political reasons and arbitrary considerations, which led Colombia to become flooded with coca, something that could be easily prevented with the herbicide. In the following week, Rueda used her daily section “¿Qué se estará preguntando María Isabel?” (“What is María Isabel wondering?”) in W Radio’s morning show, the news show with the highest radio audience in the country, to amplify the main points highlighted in the newspaper piece. In both the newspaper article and the radio show, Rueda maintained that she relied on a study given to her by the Sergio Arboleda University, a study based on facts to establish glyphosate’s actual risks.

The responses to Rueda’s claims in the public debate that ensued were mostly unfavorable, stressing aspects like her incompetence concerning chemical matters or the doubtful nature of the facts presented. This stirred up the curiosity for the Sergio Arboleda University study. What did it say exactly? Where could it be found? A couple of radio interviews that same week, one in W Radio on June 25 (Sánchez Cristo Citation2019a) and the other in La FM on June 26 (Vélez Citation2019), helped to solve the mystery. The interviewee was Professor Alberto Schlesinger, Dean of the Faculty of Economics and member of the university’s Academic Council.

In the W Radio interview, Professor Schlesinger presents himself as the leader of the study, though he clarifies in both interviews that the study was not in fact a study. It was a document. He recognizes that the university does not have academic programs, researchers, or other experts studying the health and environmental issues related to the topic. Instead, and this reveals a piece of information absent from Rueda’s opinion pieces, the document was made with the help of Bayer, a company member of the National Business Association of Colombia (ANDI) and owner of Monsanto, the company that produced glyphosate. Together with ANDI, a business think tank, and Bayer, the producer of glyphosate, Professor Schlesinger’s team collected and organized a group of studies to offer an alternative viewpoint concerning the herbicide’s risks. Professor Schlesinger also maintains that Bayer’s collaboration consisted in providing scientific studies, without paying anything for the document, so its origin had nothing to do with money or any other transactional agreement. He describes the document as a disinterested contribution to the public debate on glyphosate and the Colombian authorities that had to decide what to do with it. He points out that the document will be sent to the Constitutional Court with this in mind.

It is clear in the interviews that journalists did not have access to the document at that point. So, the more specific details about its content and extension were unknown to them. Concerning the latter, Professor Schlesinger claims in the W Radio interview that the document has no more than 50 pages, whereas in the La FM interview, no more than 36 pages. However, in a piece published on June 25, the weekly journal Revista Semana, which had access to it, affirms that the document has 35 pages (Semana Citation2019), whereas W Radio journalist Luz Helena Fonseca, in a piece published on June 26 (Sánchez Cristo Citation2019b), describes the document as a PowerPoint presentation consisting of 29 slides, with some rather controversial statements, such as the suggestion that the risk associated with the exposition to pesticides in the human diet is like the risk of having a glass of wine every three months. Both Revista Semana and Luz Helena Fonseca present the last slide, which acknowledges ANDI’s and Bayer’s help. Hence, Rueda’s study, later a document according to Professor Schlesinger, seems to have ended up being a PowerPoint presentation.

This case exemplifies the instantiation of the tobacco strategy’s structural pattern in Colombia. There is a company (Bayer) fighting science with science through the production of empirical evidence in favor of its product. The company takes advantage of its political and institutional connections. In alliance with the think tank (ANDI) to which it belongs, the company relies on an academic partner (Sergio Arboleda University) to serve as a witness in the public debate and even in court concerning its product. The university gives an important academic and scientific status to the evidence presented, emphasizing the independence of its study/document/presentation versus the information originated in the company. Likewise, it helps to communicate the company’s perspective on its product to the public through very prestigious newspapers and radio stations thanks to the efforts of a sympathetic journalist (María Isabel Rueda).

Mass media thus becomes a constituent part in the implementation of the strategy. A journalist and a professor trigger this phase through newspaper pieces and radio interviews. They invoke journalistic values to spread the message. The study/document/presentation appeals to the facts, and so warrants objectivity, since it provides an alternative perspective for the debate. This ensures a fair and balanced approach for the public and decision makers, who finally have two sides to the story. Yet the goal is neither to uncover new facts or truths, nor to protect markets and freedom. Professor Schlesinger is clear enough on this point when he insists that they did not do a study on glyphosate, but a document that organizes information previously obtained by other sources and so contributes to the public debate. The goal is then different – to build enough social and political endorsement for the industry’s stand on glyphosate’s risks and benefits, and influence the Constitutional Court’s decision to moderate its 2017 sentence, in line with the Duque administration’s petition, which, as we saw earlier, originated as a response to the Santos administration’s 2016 Peace Agreements.

It is not our aim to establish why the tobacco strategy was unsuccessful in influencing the Court’s decision. Our aim has been to provide evidence that the use of the strategy’s structural pattern is not alien to a peripheral country like Colombia. We now explore how the debate took place on Twitter at that time, because this provides further evidence of the development of the political goal mentioned in the previous paragraph.

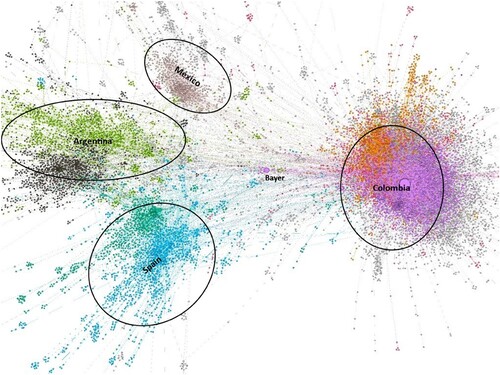

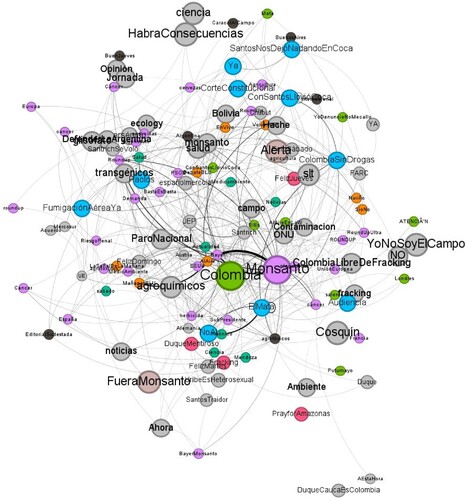

We find that the top five most mentioned hashtags for the period 2010–2019 are #glifosato, #colombia, #monsanto, #bayer, and #transgenicos. Publics utilize such hashtags to participate in the #glyphosate debate, and as part of an intertextual chain, they lead us to important markers for the conversation and the different registers of the term. Those hashtags enable us to identify the issue as a matter of public interest, discussed in several countries at different moments. thus demonstrates the existence of the glyphosate debate in several countries, including Argentina, Mexico, Spain, and Colombia. The occurrences of the debate in each country are identified with different colors, with some overlaps suggesting continuity between national contexts. The debate is clearly more important in Colombia, the bigger cluster in purple, where it revolves around the peace process with FARC-EP, politicians, and mass media. In the center of the figure, Bayer plays a broker’s role between the different communities.

In this respect, the table in summarizes the nodes (i.e. Twitter accounts) with the higher degree centrality in the debates presented in the previous figure, the sum of the edges attached to a node. There is only one node referring to an account that is not Colombian, which belongs to a Spaniard scientific popularizer. The rest are accounts belonging to Colombian institutions, politicians, and media.

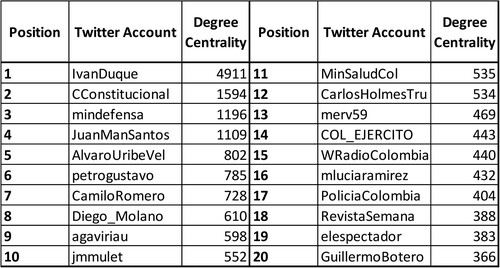

zooms in the glyphosate discussion on Twitter in Colombia. Zooming in helps us visualize the relations between the glyphosate debate. Not surprisingly, #Colombia and #glyphosate are the biggest nodes. More interestingly, following the previous assertion that #glyphosate is associated with local politics and media, the clusters revolve around Colombian issues and actors. We found that, together with glyphosate, other environmental issues are also present, such as fracking. The discussion shows glyphosate making online opposite sides engage with each other.

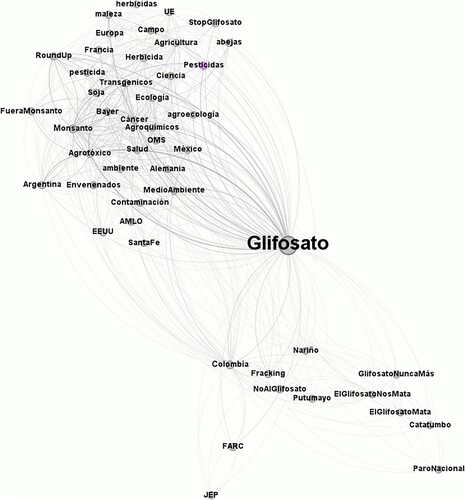

As said before, the Constitutional Court once again ruled against the glyphosate aspersions in 2019. Looking at this specific moment also allows us to move through different phases of the controversy. Around that time, some government officials, like Vice-President Martha Lucía Ramírez and Defense Minister Carlos Holmes Trujillo, weighed in on the debate, whereas journalist María Isabel Rueda invited further reflection through her discussion of the Sergio Arboleda University study/document/presentation. As demonstrates, there were spikes in the number of tweets in 2019 in relation to the Court's decision, the Defense Minister’s intervention, and Rueda’s opinion pieces. Hashtags such as “conSantosnoslloviococa” (withSantoscocarainedonus), inspired in Rueda’s opinion pieces, while not big in terms of presence and not in the graph, relate to what the media was saying about the peace process and aspersions. For instance, criticisms to the peace process, with expressions such as “FarcSantos,” and attempts to bring conspiracy theories to the debate about coca fields in Colombia.

Likewise, shows the main hashtags used during the 2019 glyphosate debate. What is interesting in these figures is the emerging connection between glyphosate and the 2016 Peace Agreements. The glyphosate debate appears connected to the local political context, particularly to oppose the 2016 Peace Agreements with FARC-EP. María Isabel Rueda’s opinion pieces reinforce this view with the assertion that Colombia became flooded with coca, “conSantosnoslloviococa” (withSantoscocarainedonus), due to the Santos administration’s decision not to use the herbicide because of the Peace Agreements.

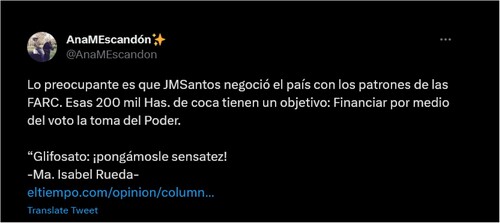

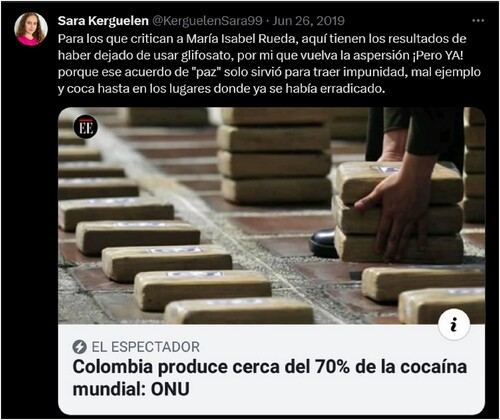

As said before, María Isabel Rueda’s intervention in the debate illustrates several features of the tobacco strategy. It created doubt and aligned mass media on its renewed interest in the topic. show examples of how her opinion pieces were used to discuss the Peace Agreements. Critics aligned with former President Uribe Vélez, who retweeted the El Tiempo piece (), whereas supporters criticized Rueda’s opposition to the agreements and her loyalty to former President Uribe Vélez’s and President Duque’s views ().

Figure 6. Former President Uribe Vélez shares Rueda’s opinion pieces (“Due to a political decision, more than a health one, [Santos] removed glyphosate, and gradually the country was flooded with coca again”).

![Figure 6. Former President Uribe Vélez shares Rueda’s opinion pieces (“Due to a political decision, more than a health one, [Santos] removed glyphosate, and gradually the country was flooded with coca again”).](/cms/asset/1dd40b8d-902c-493a-840d-0bdd0e923739/ttap_a_2297105_f0006_oc.jpg)

Figure 7. Tweet supporting Rueda’s opinion pieces (“The worrying thing is that JMSantos negotiated the country with FARC bosses. Those 200,000 hectares of coca have one objective: to finance the seizure of Power through vote”).

Figure 8. Tweet supporting Rueda’s opinion pieces (“For those who criticize María Isabel Rueda, here are the results of having stopped using glyphosate, I want the spraying to return, but NOW! because that ‘peace’ agreement only served to bring impunity, bad example and coca even in the places where it had already been eradicated.” Newspaper headline: Colombia produces about 70% of the world’s cocaine: UN).

Figure 9. Tweet criticizing Rueda’s opinion pieces (“With all due respect, Maria Isabel Rueda’s space has become her petty cash (or income cascade); she defends glyphosate with this document, she became the press chief of A.U.V. [Álvaro Uribe Vélez] She attacks peace, justifies war, in short #nomoreMariaisabelruedainLaW”).

![Figure 9. Tweet criticizing Rueda’s opinion pieces (“With all due respect, Maria Isabel Rueda’s space has become her petty cash (or income cascade); she defends glyphosate with this document, she became the press chief of A.U.V. [Álvaro Uribe Vélez] She attacks peace, justifies war, in short #nomoreMariaisabelruedainLaW”).](/cms/asset/b1d444fa-683f-49e0-bbb9-afe1d191f269/ttap_a_2297105_f0009_oc.jpg)

María Isabel Rueda’s Citation2019 opinion pieces thus contributed to the goal of keeping the controversy alive. They were discussed in terms of the accuracy of the concepts employed, but mostly they were presented without any scientific context at all, simply to express a perspective regarding the implementation of the Santos administration’s 2016 Peace Agreements with FARC-EP. In the end, glyphosate became a sort of excuse to revive the political divergences implicated in the peace process that led to the Peace Agreements. In that sense, more than a vindication of glyphosate, some markets, and freedom, Rueda’s opinion pieces worked as an attempt to spread doubts about the legal status of the Peace Agreements and undermine its public support.

6. Final remarks

In contrasting how doubt is merchandised in the center and the periphery, we can see some continuities and divergences. We find evidence that the tobacco strategy’s structural pattern, as described by Oreskes and Conway, is replicated in the peripheral context – it does not show qualitatively significant differences in its transit from one context to the other. Yet the strategy’s goal does, becoming narrower in scope. It switches from facing the more general threat of government control and intervention over institutions, markets, and freedom, to facing a more particular threat – the apparently undesirable consequences of a specific government policy. Appealing to journalists and politicians who rely on industrial and academic think tanks achieves the objective of keeping the controversy alive in the public and political sphere. The occurrences and directions of the debate in the media are thus influenced. However, the intention is not to resolve the dispute in that sphere, but to undermine the public’s trust in certain political and legal institutions, such as a government administration and even a Court, concerning their capacity to make adequate decisions about what the referred policy entails. In that way, the strategy’s goal goes from a wider scope in the center to a narrower scope in the periphery.

In the Colombian case examined here, the strategy is employed to destabilize the Santos administration’s 2016 Peace Agreements with the guerrilla group FARC-EP by means of trying to convince the Constitutional Court that its previous views on an herbicide were inadequate and supported bad government decisions. This use of the strategy to merchandise doubt took place in traditional mass media and became amplified in social networks. It is in the latter where the connection between the herbicide and the Peace Agreements became even more explicit. The environmental and health issues were discussed not to defend the herbicide as such, but to modify judicial sentences concerning the Peace Agreements. The defense of the herbicide, which helped Colombia not to be flooded with coca, thus appeared as an instrumental part of an ampler argument against the Santos administration and its Peace Agreements, the main reason why Colombia apparently became flooded with coca in the first place.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jorge M. Escobar Ortiz

Jorge M. Escobar Ortiz works at the Instituto Tecnológico Metropolitano (Medellin, Colombia) with the STS Research Group, where he was the director of the STS master's program from 2017 to 2023. He holds a PhD in Human and Social Sciences from the National University of Colombia, an MA in History and the Philosophy of Science from the University of Notre Dame, and an MA in Philosophy from the University of Manitoba. He is interested in history and philosophy of science communication, ignorance studies, science policy, and the relations between science, art, and literature.

Victoria Estrada-Orrego

Victoria Estrada-Orrego holds a Ph.D. in History from the School of Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS, France) and an MA in Humanities, Language and Culture from the Université de Bourgogne Dijon, France. Her research interests focus on the history of medicine, medical professionalization, and statistics in Colombia, particularly the use, production, and circulation of demographic and medical statistics during last two decades of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th Century.

Javier Guerrero-C

Javier Guerrero-C holds a PhD in Social Studies of Science and Technology from the University of Edinburgh (UK) and an MA in Science and Technology Studies from the University of Edinburgh (UK). He is interested in understanding the dynamics of participation and interaction in online social networks, the processes of datafication and the consequences of digital infrastructures, platforms, and algorithms.

References

- Ángel-Botero, A. M., and A. S. Babrow. 2013. “Social Construction of Health Risk: Rhetorical Elements in Colombian and US News Coverage of Coca Eradication.” Communication & Social Change 1 (1): 19–43.

- Anthony, L. 2020. AntConc (Version 3.5.9) [Computer Software]. https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software.

- Bastian, M., S. Heymann, and M. Jacomy. 2009. “Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks.” Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 3 (1): 361–362. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v3i1.13937.

- Bolognesi, C., G. Carrasquilla, S. Volpi, K. R. Solomon, and E. J. P. Marshall. 2009. “Biomonitoring of Genotoxic Risk in Agricultural Workers from Five Colombian Regions: Association to Occupational Exposure to Glyphosate.” Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A 72 (15-16): 986–997. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287390902929741.

- Breslin, S. D., T. R. Enggaard, A. Blok, T. Gårdhus, and M. A. Pedersen. 2020. “How We Tweet About Coronavirus, and Why: A Computational Anthropological Mapping of Political Attention on Danish Twitter during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The COVID-19 Forum III. University of St. Andrews, 18.

- Bruns, A., and J. Burgess. 2015. “Twitter Hashtags from ad hoc to Calculated Publics.” In Hashtag Publics: The Power and Politics of Discursive Networks, edited by Nathan Rambukkana, 13–28. New York: Peter Lang.

- Burgess, J., and N. K. Baym. 2020. Twitter: A Biography. New York, NY: New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479841806.001.0001.

- CESED Uniandes. 2021. ¿Cuáles son los argumentos a favor de la fumigación con glifosato? Y ¿qué dice la evidencia sobre por qué no fumigar?. https://cesed.uniandes.edu.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Argumentos-a-favor-de-la-fumigaci%C3%B3n-8.pdf.

- Christensen, J. 2008. “Smoking Out Objectivity: Journalistic Gears in the Agnotology Machine.” In Agnotology. The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance, edited by R. N. Proctor and L. Schiebinger, 266–282. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- El Espectador. 2022. Expolicía que accederá a eutanasia dice que enfermedad es causada por el glifosato. ElEspectador.com. September 24. https://www.elespectador.com/colombia-20/conflicto/la-historia-del-sargento-r-de-la-policia-que-se-enfermo-por-el-glifosato-y-accedera-a-eutanasia-este-lunes/.

- Highfield, T. 2018. “Emoji Hashtags//Hashtag Emoji: Of Platforms, Visual Affect, and Discursive Flexibility.” First Monday.

- Idrovo, ÁJ. 2015. “De la erradicación de cultivos ilícitos a la erradicación del glifosato en Colombia.” Revista de La Universidad Industrial de Santander. Salud 47 (2): 113–114.

- Infobae. 2022. La historia del sargento (r) de la Policía que pidió la eutanasia por enfermedad generada por el glifosato. infobae. September 25. https://www.infobae.com/america/colombia/2022/09/25/la-historia-del-sargento-r-de-la-policia-que-pidio-la-eutanasia-por-enfermedad-generada-por-el-glifosato/.

- Kreimer, P. 2019. Science and Society in Latin America: Peripheral Modernities. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Kroc Institute. 2018. Informe sobre el estado efectivo de implementación del acuerdo de paz en Colombia. Diciembre 2016 – Mayo 2018. Escuela Keough de Asuntos Globales de la universidad de Notre Dame.

- Lozano, M. 2018. “Public Participation in Science and Technology and Social Conflict: The Case of Aerial Spraying with Glyphosate in the Fight Against Drugs in Colombia.” In Spanish Philosophy of Technology. Contemporary Work from the Spanish Speaking Community, edited by B. Laspra and J. A. López Cerezo, 267–282. Cham: Springer.

- Marres, N. 2015. “Why Map Issues? On Controversy Analysis as a Digital Method.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 40 (5): 655–686. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243915574602.

- Marres, N., and C. Gerlitz. 2016. “Interface Methods: Renegotiating Relations between Digital Social Research, STS and Sociology.” The Sociological Review 64 (1): 21–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12314.

- Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito. 2019. Colombia – Monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos 2018. UNODC. https://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Colombia/Censo_cultivos_coca_2018.pdf.

- Oreskes, N., director. 2015. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists have Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Climate Change: Vol. Patten Lecture Series. March 11. https://media.dlib.indiana.edu/media_objects/x633f4845.

- Oreskes, N., and E. M. Conway. 2008. “Challenging Knowledge: How Climate Science Became a Victim of the Cold War.” In Agnotology. The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance, edited by R. N. Proctor and L. Schiebinger, 55–89. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Oreskes, N., and E. M. Conway. 2010. Merchants of Doubt. How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press.

- Procter, R., A. Voss, and I. Lvov. 2015. “Audience Research and Social Media Data: Opportunities and Challenges.” Participations: Journal of Audience Reception Studies 12 (1): 470–493.

- Revista P&M. 2022. Día Mundial de las Redes Sociales: ¿cuál es el comportamiento en social media? Revista PYM, June. https://www.revistapym.com.co/articulos/consumidor/50908/dia-mundial-de-las-redes-sociales-cual-es-el-comportamiento-en-social-media.

- Rodríguez, ÁJ. 2004. “Narcotic Drugs and the Environment: An Analysis of Recent Colombian Judicial Decisions on the Fumigation of Illicit Crops.” Review of European Community & International Environmental Law 13 (2): 227–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9388.2004.00400.x.

- Rogers, R. 2013. Digital Methods, 274. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Rueda, M. I. 2019. “Glifosato: ¡pongámosle sensatez!” El Tiempo, June 22. https://www.eltiempo.com/opinion/columnistas/maria-isabel-rueda/glifosato-pongamosle-sensatez-columna-de-maria-isabel-rueda-379552.

- Sánchez Cristo, J., director. 2019a. “Trabajamos con la ANDI y con Bayer para información sobre glifosato: Alberto Schlesinger.” La W Radio, June 25. https://www.wradio.com.co/noticias/actualidad/trabajamos-con-la-andi-y-con-bayer-para-informacion-sobre-glifosato-alberto-schlesinger/20190625/nota/3919154.aspx?rel=buscador_noticias.

- Sánchez Cristo, J., director. 2019b. “Una copa de vino es más peligrosa que el Glifosato: Informe de Universidad Sergio Arboleda.” La W Radio, June 26. https://www.wradio.com.co/noticias/actualidad/una-copa-de-vino-es-mas-peligrosa-que-el-glifosato-informe-de-universidad-sergio-arboleda/20190626/nota/3919624.aspx.

- Sanin, L.-H., G. Carrasquilla, K. R. Solomon, D. C. Cole, and E. J. P. Marshall. 2009. “Regional Differences in Time to Pregnancy among Fertile Women from Five Colombian Regions with Different use of Glyphosate.” Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A 72 (15-16): 949–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287390902929691.

- Semana. 2019. “Seis puntos para entender el polémico informe sobre el glifosato.” Semana, June 25. https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/informe-sobre-los-beneficios-del-glifosato-de-la-sergio-arboleda/620961/.

- Solano, P. 2014. “Colombia’s Herbidice Spraying in the Crucible Between Indigenous Rights, Environmental Law and State Security.” Intercultural Human Rights Law Review 9: 271.

- Solomon, K. R., E. J. P. Marshall, and G. Carrasquilla. 2009. “Human Health and Environmental Risks from the Use of Glyphosate Formulations to Control the Production of Coca in Colombia: Overview and Conclusions.” Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A 72 (15-16): 914–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287390902929659.

- Tokatian, J. G. 1992. “Glifosato y política: ¿razones internas o presiones externas?” Colombia Internacional 18 (18): 3–6. https://doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint18.1992.00.

- Torres-González, O., and C. Rodríguez-Martínez. 2022. “El debate sobre el glifosato en Colombia: Controversia científico-tecnológica y ciencia regulativa – Revista CTS.” Revista Iberoamericana de ciencia, tecnología y sociedad 17 (49): 11–37.

- Vallejo Mejía, M., and S. Agudelo-Londoño. 2019. “El glifosato alza el vuelo. Análisis retórico del discurso en la prensa nacional de Colombia (2018–2019).” Signo y Pensamiento 38 (75): 5.

- Varona, M., G. L. Henao, S. Díaz, A. Lancheros, Á. Murcia, N. Rodríguez, and V. H. Álvarez. 2009. “Effects of Aerial Applications of the Herbicide, Glyphosate and Insecticides on Human Health.” Biomedica 29 (3): 456–475. https://doi.org/10.7705/biomedica.v29i3.16.

- Vélez, J. C., director. 2019. “Alberto Schlesinger se molesta por preguntarle si Bayer financió “estudio” sobre glifosato.” La FM, June 26. https://www.lafm.com.co/colombia/alberto-schlesinger-se-molesta-por-preguntarle-si-bayer-financio-estudio-sobre-glifosato.

- Weir, J. 2005. “The Aerial Eradication of Illicit Coca Crops in Colombia, South America: Why the United States and Colombian Governments Continue to Postulate its Efficacy in the Face of Strident Opposition and Adverse Judicial Decisions in the Colombian Courts.” Drake Journal of Agricultural Law 10: 205.