ABSTRACT

This exploratory article discusses the politics of promoting women’s trade unionism in Hungary and at the World Federation of Trade Unions from the late 1940s to the late 1950s. It examines the factors that propelled and restricted the development of these politics on, and shaped their travel between, the workplace and the national and international scales. In Hungary, a network of women trade unionists combined their alignment with the political and productivist sides of the project of “building socialism” with activities aimed at the cultural and social “elevation” of women workers and the promotion of their trade unionism. On the international plane, the position of the Central and Eastern European politics of women’s trade unionism was likewise, though very differently, impacted by the emphasis on “building socialism.” Within the women’s politics pursued by the WFTU internationally, the distinctions made between socialist, capitalist, and colonial countries translated into rather restrictive roles envisioned for Central European women’s trade unionism. For a variety of reasons, which were related to all scales of action, the connection between the WFTU’s politics of promoting women’s trade unionism and the activities developed by the Hungarian women trade unionists remained rather weak during the period.

KEYWORDS:

- World Federation of Trade unions (WFTU)

- Nationwide Council of Trade Unions (Szakszervezetek Országos Tanácsa, SZOT)

- women’s trade unionism in the state-socialist world

- women’s trade union training

- Central and Eastern European women trade unionists in the WFTU

- WFTU Women’s trade union seminar Zlenice Czechoslovakia 1957

- workers’ education

This article, which is exploratory, discusses the politics of promoting women’s communist-aligned trade unionism in Hungary and at the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU), one of the three principal communist-aligned international so-called mass organizations (i.e., women’s, youth, and trade union organizations), between 1947 and 1959.Footnote1 The period was bookended by two Hungarian women’s trade union conferences, the “1st Nationwide Trade Union Women’s Conference” in 1947 and the “Nationwide [first] Women’s Conference of the Trade Unions” in 1959. In between these two events, in 1956, the Hungarian capital city of Budapest hosted the “[First] World Conference of Women Workers,” organized by the WFTUFootnote2 (Szakszervezeti Tanács Citation1948; Citation1955; Supplement, November Citation1955, 1; WFTU Citation1957, 43; Népszabadság 13 February Citation1959; Népszava 28 February Citation1949; Magyar Nemzet 12 February Citation1959; Postás Dolgozó 1 March Citation1959). Promoting women’s trade unionism was deemed a relevant policy goal for communist-aligned trade unionism during the period, and such efforts included two major elements: winning working women over to trade unionism and converting them into active and politically engaged workers and trade unionists; and training women trade unionists so they could stand their ground as effective and professional union cadres on the shop floor, the national stage, and beyond, as participants in international leadership.

Contrary to what might be assumed at first glance, the three conferences were not indicative of the smooth development of the communist-aligned politics of promoting women’s trade unionism. This article examines the development of these politics at the workplace and national levels in Hungary and in the international sphere of the WFTU, discussing the factors that propelled and restricted the development of these politics on, and shaped their travel between, the workplace and the national and international scales. There is a flourishing historiography on both communist-aligned internationalism in the post-1945 period and women’s organizing and activism in the state-socialist world, and this research has addressed trade unionism, women’s work, and the politics of scale (e.g., Jarska Citation2018; Grabowska Citation2017; Fidelis Citation2010; Nowak Citation2005). I am not aware of research, however, that has aimed to “think together” the different scales of action of the politics of promoting women’s communist-led trade unionism in Central and Eastern Europe and internationally in the period discussed here.

Putting aside simplified ideas about the top-down character of communist-led trade unionism, this article presents three main arguments. First, an activist network of Hungarian women trade unionists engaged with women’s trade unionism from the shop floor to national leadership combined their alignment with both the political and productivist sides of the project of “building socialism” with activities and initiatives aimed at promoting women workers’ trade unionism, and the cultural, educational, and social “elevation” of women workers. Second, on the international plane, the position of the Central and Eastern European politics of women’s trade unionism was likewise, though very differently, impacted by the emphasis on “building socialism.” The women’s politics pursued by the WFTU were characterized by a triple distinction between socialist, capitalist, and colonial countries, which translated into rather restrictive roles envisioned internationally for Central and Eastern European women’s trade unionism. Third, for a variety of reasons related to all scales of action, the connection between the WFTU’s politics of promoting women’s trade unionism and the activities developed by the Hungarian women trade unionists remained rather weak during the period considered in this article.

The article proceeds chronologically. Foregrounding key events, innovations, and changes as they occurred consecutively on, along, and across the international, national and enterprise scales, I repeatedly briefly juxtapose key changes occurring on one level to the state of the politics of organizing and training women trade unionists on those scales that were less eventful at the given moment. I conclude by situating my findings within the emerging comparative and global history of women’s trade unionism in the twentieth century.

In the Service of a New Political Economy: Women’s Trade Unionism in Hungary from the Shop Floor to National Leadership, 1947–1954

In the period before the advent of the WFTU’s politics of promoting women’s trade unionism from 1953 onwards, Hungary witnessed two waves when women’s trade unionism was promoted. The first one, spanning the period between late 1947 and summer 1949, was strongly motivated by the combined political goal of transforming women workers into – as prevailing discourse put it – cultivated socialist citizens who would consent to or actively support the emerging political system. The second wave, beginning in 1951 and ending in winter 1953/1954, more visibly foregrounded economic and specifically productivist goals. The ups and downs of women’s trade union activism during the period were, in part, a result of repeated shifts of responsibility at the workplace for all issues related to working women; these shifts involved, on the one hand, trade unions, and, on the other, the Democratic Alliance of Hungarian Women (Magyar Nők Demokratikus Szövetsége, MNDSz; replaced 1957 by the National Council of Hungarian Women [Magyar Nők Országos Tanácsa]) (Schadt Citation2007).Footnote3 The back and forthFootnote4 was, as we shall see in the following discussion, related to top-level party decisions and likely changing directions within the Women’s International Democratic Federation (WIDF), the communist-led international women’s “mass” organization. It undoubtedly speaks to the regime’s neglect of the politics of women’s work and the women engaged in it, as well as the inefficacy of some of the actions directed at women in the workplace.

The Hungarian development had no straightforward anchor in international communist-led trade unionism as institutionalized in the WFTU. Before 1953, the WFTU did not display a pro-active interest in promoting and building women’s trade unionism internationally, i.e., beyond its principal support for the cause. At the same time, both before and after 1953, the WFTU pursued an internationally highly visible women’s politics that was focused on key international organizations including the ILO and various UN-forums where WFTU representatives pressed for global commitments to labour-related demands and resolute women’s equality politics (Wolf CitationForthcoming; Cobble Citation2021; Boris Citation2018).

Within Hungary, the emphasis on women’s trade unionism signalled that communist-linked actors recognized how proactive trade-unionist women’s politics could serve important purposes in and on behalf of the emerging state-socialist state. Self-confident women trade unionists seized the opportunity to expand their own scope of action at their workplaces in particular, and they aimed to promote certain interests of women workers.

The “1st Nationwide Trade Union Women’s Conference” in November 1947 signalled that communist-led women’s trade unionism and trade union education for women workers were to play prominent roles in the political and economic transition underway in the country. The only agenda item of the conference defined by content was devoted to “education,” which was described as the “most important” task of trade union women’s work. Both keynote speakers, Matild B. Tóth and Erzsébet Ács, who served as secretary and deputy secretary in the “national leadership of the trade union women’s movement,” respectively, addressed the education of women. Education served to free women from the “harmful teachings” of the past; it drew them into the service of constructing the country, and it made them aware of their duties, including work discipline. Returning to their duties after the conference, the three hundred participants were called to do their best to awaken in all fellow women “the love of a strong, united trade union movement” (Szakszervezeti Tanács Citation1948).

The vision thus publicized assigned to women’s trade unionism a special mission in support of the country’s ongoing political-economic transformation. The Trade Union Women’s Conference took place soon after the first three-year plan went into effect in August 1947, only weeks after the Hungarian Communist Party (Magyar Kommunista Párt) had committed to a politics of marginalizing “right-wing social democrats” in the trade union movement. “Unification” of the social democratic and the communist party under the name the Hungarian Working People’s Party (Magyar Dolgozók Pártja) would be completed in June 1948. From the summer of 1947, dominant trade unionism began to foreground the role of trade unions in the “support of production.” The workplace committees (üzemi bizottság), which increasingly came under trade union – and thus gradually communist – control, engaged with tasks related to production (the implementation and monitoring of the fulfilment of the plan, work competitions, the brigade movement), the education of workers (the improvement of work discipline, political instruction), the promotion of trade unionism (cadre work and training), and workers’ welfare. The transition to the communist-dominated political and economic regime was completed in the first half of 1949 (Lux Citation2008, 92–103; Kun Citation2004; Belényi Citation2000b, esp. 62, 65; Horváth Citation1949).

Within the Trade Union Council (Szakszervezeti Tanács), which from late 1948 had transformed into the Nationwide Council of Trade Unions (Szakszervezetek Országos Tanácsa, SZOT), the women guiding the Hungarian trade union women’s network had at their disposal a central secretariat populated (in 1949) by the “political staff members” Erzsébet Ács, Ibolya Dankó,Footnote5 Rózsi Hazai, Blanka Sándor, and Matild Tóth. In spring Citation1949, two members of this staff were away for full-time training at the SZOT school and the party school, respectively (Szakszervezeti Tanács Citation1948, 18; “Feljegyzések” Citation1949; “Jelentés” Citation1949). Throughout the late 1940s and the early 1950s, (women’s) trade union work in Hungary visibly built on Soviet models and practices as they travelled within the evolving world of communist-led trade unionism across Central and Eastern Europe. This concerned the training of women trade union leaders, the assignment of tasks and the division of labour among them, and the policies of production aimed at “building socialism,” which included the transition to payment-by-results, socialist labour competitions, norm management, and so on.Footnote6

The Hungarian trade union women’s network, as it engaged with the move towards communist-led (trade union) politics and the transformation of trade union institutions in factories, carried the momentum of late 1947 into 1949. The trade union women persistently aimed to further women’s representation in trade union life in the enterprises and beyond. In the run-up to the elections for the new style of workplace trade unions committees in spring 1949, they made every effort to ensure the representation of committed women trade unionists engaged with enterprise-level women’s work within these new representational bodies in order to spread knowledge about and propagate the ensuing changes, and to enrol women in much greater numbers in SZOT training courses (Bars Citation1949, “Jegyzőkönyv” Citation1949b). Later, before the national elections, which took place in the spring of 1949, the trade union women’s network conducted a campaign aimed at the “mobilisation and activation of the more than 400,000 organised working women,” which entailed many types of activities (SZOT NBO Citation1949).

Workplace-based activities played a key role. This included training women employed in enterprises to do their best as workers to foster the economic element of “building socialism,” support women workers through workplace-based activities in their everyday lives, and to jolt them out of their lack of ambition and ignorance – characteristics identified by seasoned women trade unionists as the main features of a large strata of mostly first-generation women workers – so as to awaken and increase their cultural aspirations and political awareness. Early in 1949, more than six hundred factory-level trade union women committees – installed in enterprises where women composed more than half the workforce – had been established, even if some existed “only on paper” in places outside the greater Budapest region. Factories with less than fifty female personnel had to instal a Representative in Charge of Women’s Issues (nőfelelős) (“Jelentés” Citation1949; “Feljegyzések” Citation1949).

Education that was tailored to women workers’ special needs, interests, and position served as the guiding star of many activities happening at the workplace or grounded in workplace-based action. Women workers who “did a good job” in the workplace trade union women’s committees were sent to trade union training and then installed as trade union functionaries. The women’s trade union network was involved in standard “general” education, often organized in mixed-gender settings, and it was responsible for the organization of educational activities for those women workers whose training did not reach an “elementary level.” The women made every effort to reach out to “the most backward strata … in each enterprise of each branch” to address these women via “political education,” with the aim of wresting them from the influence of “pacifism” and “clericalism.” The monthly organization of “workplace women’s days” (üzemi nőnap) constituted a key instrument of women’s workplace-based mass education. These were dedicated to “the resolution of local problems and the discussion of the general questions.” One 1949 report claimed that women trade unionists in 1948 organized seven hundred “women’s days.” “Women’s circles” (asszonykör) constituted another educational genre considered similarly important, where groups of fifteen to twenty-five women heard a series of six lectures. There were other types of training too, including lecture series labelled “Mothers’ schools” (anyák iskolája) and shorthand-writing, tailoring and sewing, cooking, and other “special women’s training courses,” all of which “attracted much (igen nagy) interest” (“Üzemi MNDSZ csoportok” [likely Citation1949]; “Nők”; “Citation1949. február 4”; “Jegyzőkönyv” Citation1949c; “Jelentés” Citation1949). Clearly, these hands-on activities were multipurpose, generating, through a politics of practice, access to women workers, supporting them in some of their most immediate interests, educating them to become more “cultured” citizens, and appealing to them to participate in “building socialism.”

The activities of the trade union women’s network and the women-only trade union structures and initiatives within enterprises encountered manifold challenges. Trade union women steadily criticized the obstructionist attitudes they encountered in the masculinist world of trade unionism and the male-dominated world of work more generally. “In many places, [trade union] women’s work in the workplace, regardless of whether the women’s committee works well or badly, is looked down upon and is belittled” (“Jelentés ” Citation1949).

In sum, between late 1947 and summer 1949, trade union women, pursuing a complex set of purposes, emphatically made use of the opportunities produced by the imposed “unification” of the political landscape under communist leadership. By contrast, the WFTU during the periodFootnote7 was characterized by a disconnect between the organization’s proactive women’s equality politics directed at various international organizations and an obvious indifference regarding the promotion of women’s trade unionism. The regionally specific role of women’s trade union activism in Central and Eastern Europe, showcased by the first wave of women’s trade union activism in Hungary, was visibly irrelevant for shaping the WFTU’s policies.

After the completion of the political regime change in Hungary in the summer of 1949, the extended network of women’s trade union work, with its focus on workplace organization and action, was “replaced” by MNDSz activism, which was now formally extended to the workplace. The second wave of pronounced trade union activities aimed at women workers and systematically involving women cadres began in late 1951, when MNDSz was asked to withdraw from workplaces (“A SZOT Elnökség” Citation1952). It was, as compared to the first wave, centred in a more one-dimensional manner on economic and production-oriented goals. In preparation for and during the First Five Year Plan (1950–1954), the trade unions under the leadership of SZOT were forcefully enlisted as key actors who were to assist in realizing the employment of an ever-expanding workforce and achieving the maximum performance of workers. Between late 1949 and into 1951, the production and investment targets to be reached under the Plan, which already originally demanded intense effort from the workforce, were repeatedly increased. A figure equivalent to 26.5 percent of the generated resources dedicated to reinvestment in 1951 (with a strong focus on heavy and military-oriented industries) marked an all-time high (a figure that was high also compared to other Central and Eastern European countries) (Pető and Szakács Citation1985, 151–178; Politikatörténeti Intézet Citation1950a; Citation1950b).

In 1952 these policies linked to a nation-wide campaign, orchestrated by the SZOT-leadership, to again “better mobilise women into the work of the trade unions” (Pellek Citation1952). A series of top-level decisions made in April and May 1951 stipulated that large numbers and proportions of women be among the future new hires and those to be enrolled in vocational training in 1951, as well as the instalment of “responsible person[s] (felelős) … distinctly concerning themselves with the women employed in production” in many enterprises. These decisions combined the vision that women were to “take part in the building of socialism in a manner identical to men” with plans for the massive expansion and improvement of childcare and other facilities to “ensure the prerequisites” of the new policy (“153/7/Citation1951, N. T. sz.”; ”1.011/Citation1951 , MT Citation1951”; see also Palasik Citation2005, 92–96). Between October Citation1951 (Belényi Citation2000a) and May 1952, SZOT came up with a new framework for workplace-level trade union women’s work. In early 1952, the flagship trade union journal Munka (Work) emphasized that in “places where women are still marginalised in production (e.g., they complete various vocational training courses with good results but are still assigned to sweeping or similar work), the [workplace trade union] women’s committee has the task of securing, through the [trade union’s] workplace committee, that women are assigned to posts commensurate with their skill” (Pellek Citation1952). The May 1952 SZOT decision decreed that the workplace trade union committees were to elect from their midst a Representative in Charge of Women’s Issues who, in turn, was to serve as the head of the women’s committee. In many places during the period, this tended to translate to the inclusion of a woman trade unionist dedicated to proactive engagement with the politics of women’s work in the workplace trade union committees, which played a key co-managerial role in enterprises. “Particular care” was to be taken to involve women in “the leading trade union organs,” and systematic attention was to be paid to the newly arrived women workers “so they get acquainted with and become attached to (megszeret) factory work” (SZOT Elnökség Citation1952; “Szakszervezetek” Citation1952). In retrospect, Mrs. Ernő Déri (Erzsébet Hideg), a long-term key trade unionist engaged with women issues, described the May 1952 SZOT decision as determining, “in essence for the first time” after 1945 and national in its scope, the overall content and structure of trade union women’s work on the enterprise level (Déri Citation1970).

The engagement of the trade union women’s network with the task of tying women to their economic role(s) in “building socialism” through educational and other actions centred at the workplace reached back to 1948. As women’s trade unionism – now under closer local trade union supervision but with de facto greater local powers – was assigned a key role in workplace action aimed at women workers starting from 1952 onwards, the women at the helm of the trade union women’s network set in motion a whole machinery of actions. Describing 1952 as the “central year of the Plan,” the trade union women’s leadership, working now from the new full-scale Women’s Committees Division (Nőbizottságok Osztálya) of SZOT as its institutional platform,Footnote8 instantly devised plans for encouraging women’s vocational training; “monitoring” women’s participation in trade union and party training; ensuring that the trade union Representatives in Charge of Women’s Issues were enrolled in such training in the “important larger” enterprises; “promoting women’s increased activity in work competition”; and organizing women’s “reading circles” and “mass lectures” (Veres Citation1952b). Workers “in plants and plant divisions lagging behind should be dealt with separately by the women’s committee in the form of individual and group meetings” (“T. Szakszervezetek” Citation1952).Footnote9

The SZOT women developed detailed instructions regarding the curriculum for the (many) trainings to be held for the Representatives in Charge of Women’s Issues in enterprises and members of the women’s committees. The curriculum of one-day courses, for example, consisted of six units covering many specified topics, and detailed teaching materials were provided. Some units were composed of thirty-five to forty-minute lectures followed by ninety minutes of discussion, whereas others were kept shorter. A two-hour session was foreseen as the “festive closing” of the day (“Vázlat” Citation1952).

The Representatives in Charge of Women’s Issues in enterprises and other women occupying different positions in the network of trade union institutions were repeatedly brought together in various constellations at nationwide meetings. They reported regularly to the SZOT Women’s Committees Division. SZOT women, in turn, developed lively monitoring and reporting activities down to the enterprise level.Footnote10 They relentlessly identified an array of grave problems relating to, for example, women’s enterprise-based vocational training and explained women’s reluctance to engage in (re-)training programmes, their staggering dropout rates, and so on (see also Schadt Citation2007). They documented and criticized the attitudes of women workers and proposed realistic explanations for these problems, referring to the life circumstances of certain groups of women workers. In the main, however, their critique focused on the attitudes of skilled men workers, trade union bodies and functionaries, and management as the key reasons for the underdeveloped state of things.

[The trade unions] did not provide the assistance necessary for organising vocational training courses (szaktanfolyamok) and conducting them at an appropriate level. The [workplace trade union] committees and the [trade union] women’s committees did not take a strong and militant stand against the backwardness, professional chauvinism, underrating of women, and machinations of the enemy that were evident among individual long-standing skilled workers and foremen … . [T]hey told the women not to learn the welding profession because they would not have children and [because] it kills the red blood cells …

It is common that the devaluation of women is no longer characterised by sending them back to the wooden spoon but by entrusting them with work beyond their physical strength and professional (knowledge) … . [In the Stalin Municipal Waterworks] … only 5 out of 34 skilled women workers are working in the trade because the old skilled workers did not bring them into the brigade …

… In some factories … the women were assigned to afternoon or night shifts also during the [vocational training] course, which, on the one hand, hindered their continuous acquisition of the theoretical (knowledge), and, on the other, again led to dropouts.

This was accompanied by frequent changes of the teaching personnel, the lack of premises …

Another reason for the shortcomings … is the lack of a proper link between … theoretical and practical training. Consequently, the majority of course graduates perform below 100% for several months. (Veres Citation1952a; see also SZOT NBO Citation1952)

Another focus of critique concerned the relationship between the trade union apparatus and the trade union women’s work more generally. One report gave a sobering evaluation of the reality:

The consolidation of the [trade union] women’s committees is hindered by the fact that the [trade union] workplace committees do not make use of [the women’s committees’] work, do not entrust them with concrete tasks … . The fact that not the best working women are placed in [the sphere of trade union women’s work] contributes to the fluctuation … those who don’t know well enough the problems of the working women … [or] don’t have the appropriate education and experience in the movement work … .

[T]he higher organs also treat [the work related to women] as a compartmentalised task … . The comrades working in the [branch] trade unions also do not call to account the [trade union] workplace committees concerning this work. (“Jelentés” Citation1953)

By the end of 1953, another party decision was made which was intended to revive the MNDSz workplace committees (Schadt Citation2007, 181–182); a few months later, in early 1954, the dissolution of the workplace trade union women committees was underway (“Határozat” Citation1954; Cseterki Citation1954). This happened in tandem with a sea change on the international level, namely the turn of the WFTU to a proactive politics of promoting women’s trade unionism.Footnote11

The WFTU Promoting Women’s Trade Unionism in Central and Eastern Europe? 1953 to 1957

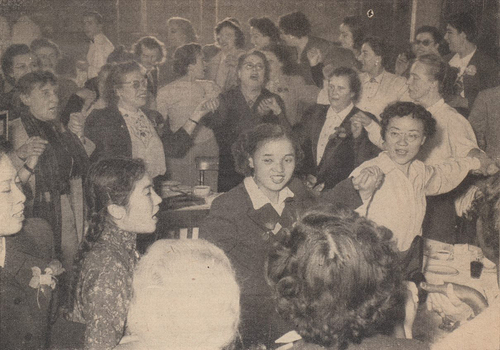

Central and Eastern European state-socialist countries, or, more precisely, trade unions and women trade unionists in state-socialist countries who engaged with women politics were visibly involved in the developments taking place within the WFTU from 1953 on (). However, these actors were neither the key addressees nor (in all likelihood) the key driving forces of the new WFTU politics of promoting women’s trade unionism. These global politics, to a large degree, were determined by agendas focused on Western capitalist countries and the Global South. Women trade unionists in Eastern Europe did the best they could to use these changes to advance their cause in both the domestic and international context.

Figure 1. Women’s meeting at the WFTU’s Third World Trade Union Congress 1953. “During their impressive meeting, the women express their common will in song.” In the background, among others, Nina Popova (secretary of the Central Council of the Soviet Trade Unions) and Teresa Noce (secretary general of the Trade Unions International of Textile and Clothing Workers)Footnote12.

The WFTU’s international activities aimed at a communist-led unionization en masse of working women and trade union training for women (Harisch Citation2018; Citation2023) were informed by the pursuit of the WFTU’s principle of the “unity-of-action-from below” as it translated into the international context after the split between the WFTU and the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) in 1949. This entailed carefully orchestrated tactics, including a focus on the rank and file within non-communist (dominated) trade unions, calling on them to both adhere to the trade union tradition of unity of action and participate energetically in broader movement actions or initiate such action. One of the important goals was to “undermine rival trade-union leadership” on the national, local, and workplace levels (Lichtblau Citation1958,Footnote13 esp. 11–12, 18, 25–28).

The decision to convene a world conference of women trade unionists was made by the WFTU’s General Council in December 1954 (Josselson Citation1956) in tandem with the adoption, “after a long and much publicised campaign” (Facts Citation1957, 29) of a Charter of Trade Union Rights which was to give “fresh impetus to the participation of women in the struggles for demands and in trade union life” (WFTU Citation1957, 43).Footnote14 The General Council was strongly preoccupied with the struggle against a new world war, the outbreak of which it considered imminent. For WFTU General Secretary Louis Saillant, this transformed the pursuance of a proactive “unity of action” politics into the single most important question. The WFTU should not, he noted, try to spell out internationally specific steps and statements “valid” for all times and places. Yet the WFTU was to adhere to and advance one guiding principle, namely the strategy “[t]o unite the largest possible number of workers in trade unions, i.e., to involve the unorganised in active trade union work as often as possible and to receive them into an effective trade union membership” (Saillant Citation1955).

The proposal to hold a world conference of women trade unionists and the suggestions for its main agenda items were fully informed by this renewed emphasis on “unity-of-action-from-below.” The proposition was advanced by Benoit Frachon, the general secretary of the French General Confederation of Trade Unions (Confédération générale du travail), who, again with a focus on capitalist countries, declared: “I … believe that the WFTU should pay more attention to the situation of women than it has done so far. It is true that we have the [WIDF]. But there are also women in the ranks of the WFTU. There are many women in the factories, and it is these women in particular who are being exploited by the escalation of war politics”; the conference should “put forward a plan for a major campaign of action throughout the world … to secure equal pay for women” (Fracon Citation1955, i.o. partly in bold letters). Nina Popova – the vice-president of the WIDF, president of the Soviet Women’s Committee, and present at the WFTU General Council meeting in her capacity as secretary of the central council of the Soviet trade unions – instantly expressed her gratefulness. “We … believe that the launch of a major international campaign for the rights enshrined in the [WFTU] Charter [of Trade Union Rights] would develop organised trade union action to defend the rights of women and young people” (Popova Citation1955).

Women’s trade unionists in the state-socialist countries clearly were not the main addressees of the conference initiative and the new international politics of the WFTU. In Hungary, the SZOT Presidency at the time emphasized in a formal decision that the “desire for unity was first and foremost expressed in the majority of the capitalist and colonial countries through the common struggles and movements for common demands” (“Az SZVSZ” Citation1956). The WFTU Executive Bureau soon recommended that the women’s conference “be held on a united basis,” meaning that it “has to be open to all wage-earning working women, whatever their trade union affiliation, whether or not members of trade unions and regardless of whether they were leaders or active trade unions members.” The conference was to “encourage” women “to take a more and more active part in the struggles and activities of all the workers.” Accordingly, the Executive Bureau specified that, besides the issue of equal pay, a second major agenda item would address the “more active participation of working women in the life and leadership of the trade unions” and their “wider recruitment to the trade unions” (WFTU Citation1957, 43–44). In his widely publicized report laid before the WFTU Presidency in May 1955, WFTU Secretary Luigi Grassi pointed to the various functions the conference was to fulfil in terms of promoting women’s trade unionism. Working women from “countries with different social systems” were to meet, compare their life and work circumstances, gain mutual understanding, and develop friendships. In addition, the conference would “provide a further incentive to involve working women in the business (intézés) and leadership (irányítás) of trade union affairs and … encourage trade unions to recruit new female members” (Luigi Grassi Citation1955).

A committee installed to organize the conference met three times: from September 29 to 2 October 1955 (Bucharest), May 10 to 12, 1956 (Budapest), and on the eve of the conference itself. The composition of the Preparation Committee was not entirely stable. Representatives of trade unions belonging to the WFTU and “trade unionist women workers” from a few non-socialist countries took part in the first meeting. From Eastern Europe, Romania, Czechoslovakia, and the Soviet Union contributed to the work of the committee at various stagesFootnote15 (WFTU Citation1957, 43–44; Supplement, November Citation1955, 1; May Citation1956, 2; Madeleine Grassi Citation1955; “A Dolgozó Nők”).

WFTU activities at the time signalled there were larger motivations and purposes informing the organization of the women’s conference. A WFTU press conference in Vienna in November 1955 connected the intention to promote trade union women’s politics to efforts to temper international political tensions. The WFTU advocated for “limited agreements, at least on certain issues, between the three major international trade union centres,” considering equal pay for women and men “[o]ne such issue.” At the forthcoming international women’s conference, such an agreement could be discussed without stipulating “any preconditions” other than an atmosphere of mutual respect for each other’s commitments and frank and open information and discussion (“Az SZVSZ Titkárság” Citation1955). The preparation work for the women’s world conference was widely publicized via issuing a Supplement to the WFTU’s World Trade Union News starting in November 1955; this Supplement was dedicated solely to the conference and disseminating information on women trade union issues and activities around the world (WFTU Citation1961, 21). Focusing strongly on exploitation, struggles, and conference preparations in Western countries and countries in the Global South, the Supplement repeatedly contrasted, e.g., “wage discrimination in capitalist countries” with “complete equality in socialist countries” (Supplement, January Citation1956, 8).

The preparations for the women’s world conference in Hungary showcase the status assigned to Central and Eastern European women’s trade unionism in relation to the WFTU world event. SZOT’s international division defined the role of the conference in relation to Hungarian women and the Hungarian delegation: “For the Hungarian working women too, the World Conference of Women Workers is of great importance because here they can become acquainted with the difficult life of struggle of working women living in capitalist and colonial countries, and [the conference] gives [them] the opportunity to make known their own changed lives, which before liberation was similar to the situation of women” living in those other parts of the world (SZOT Citation1956). Thus, Hungarian representatives to the international gathering were called on to embody Central and Eastern European progress rather than the ongoing women’s trade union struggle in the region. Still, this large international event gave them an opportunity to make their voices heard within the WFTU-led international women’s network and to try to advance their cause in their respective domestic contexts. Moderate critique of the state of things on domestic Hungarian soil even made it into the Supplement, narrowing the often extremely wide gap between information about state-socialist countries spread internationally within the WFTU and confrontations that took place on the enterprise and national levels within state-socialist countries. The Supplement reported that in Hungary “[m]eetings” were “held at the place of work … discussing the problems of women workers in different enterprises, and examining the possibilities of further improving the social amenities designed for the benefit of women at work.” In “interesting meetings in the Houses of Culture belonging to various enterprises,” the “‘old hands’ have been telling the young workers about the difficulties they had before the Liberation … They are discussing what still needs doing in order to put an end to shortcomings, and to solve the problems that still persist, so as to go on improving the conditions they now enjoy”Footnote16 (Supplement, May Citation1956, 8).

Within the Hungarian trade union women’s network there was a clear understanding and critique of the limitations of the role foreseen for trade unionists from state-socialist Central and Eastern Europe on the international stage. The speech of the Hungarian delegate at the conference (“Drága Barátnőink” Citation1956)Footnote17, given in response to the two main reports presented, used harsh words to criticize the side-lining of their concerns:

I need to note, however, that the reports would have needed to engage more with the position of the working women in the countries that build socialism. Because we, too, have problems—even if they present themselves differently than in the capitalist countries, these are living (élő) problems, which our trade union movement needs to resolve. It is for this reason that we Hungarian working women greeted with joy the [WFTU] initiative that those with the biggest interests (legérdekeltebbek): the working women, gather together (összeül). (“Drága Barátnőink” Citation1956)

After this opening remark and “deviating from the custom,” the speech restricted references to “our results” to less than one manuscript page of the contribution, only to turn to a presentation of “ our difficulties, the problems which the Hungarian trade unions must resolve,” which ran for a length of nearly five manuscript pages.

Preceding various contributions to the conference debate, including the above Hungarian contribution, Preparatory Committee member Tsune Deushi from Japan presented the main report on the second agenda item, women’s trade unionism to the conference attendees. The report proposed “ask[ing] the national trade union centres and the international trade union organisations to include women in their leaderships”; that “a greater effort … be made to let women workers attend trade union schools and even to organise special sessions for militant women trade unionists”; and that trade unions should work towards establishing and expanding social facilities, e.g. nurseries, to allow women “to take a more active part in trade union and social life” (Bell Citation1956; “World Conference of Women Workers” Citation1956). The general resolution adopted by the conference referred to the WFTU’s “great recruiting campaign among the women workers” and the “bolder promotion of women cadres to leading positions in the trade union movement at all levels” (“General Resolution” Citation1956).Footnote18

On the international stage, the World Conference indeed constituted a key event in the WFTU’s turn to a proactive promotion of women’s top-level trade unionism. This included several key innovations. First, the WFTU bade farewell to the men-only composition of its own leadership. From November 1955 at the latest, the Italian Maddalena Grassi (born Secco, first name also given as Madelena and Madeleine, wife of WFTU functionary Luigi Grassi) served as the leader of the division of women’s affairs within the WFTU Secretariat, the administrative head of the organization, taking up a key role in preparations for the conference. In September Citation1956, Elena Teodorescu, a member of the executive committee of the Romanian trade union federation and a “long-time fighter of the labour movement,” was elected to the WFTU Secretariat, serving as one of six WFTU secretaries, i.e., “full-time salaried officials” within the executive leadership of the WFTUFootnote19 (Népszava 27 September Citation1956; 2 October Citation1956; Előre 10 September Citation1957; Bell Citation1956; Facts Citation1957).

Second, after the World Conference of Women Workers, the WFTU made every effort to exhibit the turn to women’s trade union leadership as it continued to pursue its international politics of promoting women’s equality. Before the conference, a WFTU delegation comprised of the men-only WFTU executive board, at a meeting with the Director-General of the ILO, extended an invitation for an ILO official to attend the World Conference. Louis Saillant, Secretary-General of the WFTU, felt the need to state that next time, the WFTU “hoped to rectify an omission in the present delegation and to have with them a qualified spokesman for women’s interests” (“Minutes” Citation1956). In November 1956, after the World Conference, leading officers of the International Labour Office indeed received a four-women WFTU delegation to discuss “problems of mutual interest concerning women workers.” Besides Teodorescu and Grassi, the group included the leading French trade unionist Germaine Guillé and Teresa Noce, the secretary of the Trade Unions International of Textile and Clothing Workers, who represented the Trade Department of the WFTUFootnote20 (Alvarado Citation1956).

Third, the WFTU aimed to elevate trade union involvement in the international politics of women’s work to a higher status. The World Conference of Women Workers adopted and presented a memorandum to the ILO Director-General in which it proposed the establishment of a Tripartite Committee for Women’s Work. Tripartite committees constituted the highest-ranking type of expert committee attached to and advising the International Labour Office; with a guaranteed proportion of trade union (and employers’ and state) representatives, their tripartite constitution replicated a fundamental design principle of the ILO. The WFTU women’s delegation to the ILO mentioned above followed up on the memorandum, demanding the inclusion of “an item concerning women’s problems” in one of the sessions of the International Labour Conference. It also inquired about the possibility that the International Labour Office could facilitate the convocation of “a Conference of the different world trade union organisations” to take action in support of the ILO’s equal pay convention adopted in 1951 (Alvarado Citation1956).

Fourth, at the World Conference of Women Workers, the idea to organize an international training seminar for women trade unionists was proposed (WFTU Citation1961, 21). A few months later, in February Citation1957, the WFTU Executive Committee, wishing to “consolidate” the “encouraging” results of the conference and “to contribute towards the training of women trade union cadres and to a more active participation by women workers in the life and leadership of trade unions,” approved the plan for a seminar “for active women trade unionists of different countries”Footnote21 (WFTU Citation1957, 47). The two-week event took place in a trade union training centre in Zlenice, not far from Prague, the capital of Czechoslovakia, from 15 to 30 September 1957 (WFTU Citation1957, 104). Among the more than thirty participants, many came from the Global South; participants from Eastern Europe included trade unionists from Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The seven topics discussed there were carefully chosen as an ensemble to be truly global and inclusive in their outlook. Under the heading “equal rights for women workers; the role and responsibilities of the trade unions in the socialist countries” the state-socialist world region was given a visible place. Other agenda points addressed – always in relation to women’s work and trade unionism – the “capitalist, colonial and semicolonial countries,” plantation workers, national independence movements, and the WFTU’s own “campaigns and responsibilities”Footnote22 (WFTU Citation1961, 21, 104).

Fifth, the WFTU, following the World Conference, engaged in a highly publicized campaign (W.F.T.U. Citation1957) to bring “women … more into the life and leadership of the unions,” with the aim of stimulating women’s trade unionism on the national and local levels as well. The campaign built and expanded on the insight that there existed “the need not merely for trade union organisation but also for [women’s] own wider share in the life and activities of the trade union movement.” In preparation for the WFTU’s World Trade Union Congress in Leipzig in October 1957, specific problems standing in the way of achieving this goal and the means to resolve them were identified and discussed in a widely circulated brochure (W.F.T.U. Citation1957). Men, for example, did not yet realize women’s capabilities and thus did not entrust them with relevant tasks, or, they failed to consider women’s “lack of experience,” so women were “given too many duties at a time,” resulting in high drop-out rates. Remedies included a reliance on “active women trade union members who already hold posts of responsibility” to “help trade unions to carry on activities” among the large groups of still unorganized women workers. While foregrounding other world regions, the socialist countries were explicitly included in the global campaign. The conditions of women workers in these countries were “made very much easier by an extensive network of social amenities with the result that they take a more active part in the life and leadership of their trade union organisations than women do elsewhere and are demanding ever greater participation.” In the socialist countries, the “problem of the day” was “to overcome difficulties arising from the building of a new society.”

The WFTU’s World Trade Union Congress, convening only a few days after the closing of the women’s seminar, advocated, in globally unspecified terms, for the spread of specialized measures to promote and develop women’s trade unionism in all countries. The trade unions were asked, e.g., “to pay careful attention to finding appropriate ways to overcome the practical difficulties met by women because of their numerous family duties” (Texts Citation1957, 44). With a view to guiding national centres accordingly, the WFTU published a “pamphlet” after the Congress which aimed to popularize (together with many other aims and plans) the relevant decisions and recommendations made at the Congress. “Congress stated that ‘the trade unions should see women workers’ problems as an integral part of trade union activities as a whole. Consideration of their aspirations and demands will greatly help … women to take their rightful place at all levels in the trade unions.” The pamphlet also informed readers that the “Congress recommended trade unions” train and support “women trade union leaders,” organize “more events such as the First International Seminar for Women Trade Unionists,” and “strengthen educational and propaganda work among women” (Review Citation1957, esp. 15).

WFTU and SZOT Strangely in Sync: The Hungarian Coda, 1956 to 1959

In Hungary, in the years following the 1956/1957 peak of WFTU action, SZOT activities regarding women’s trade unionism unmistakably resonated with key international activities and credos newly adopted by the WFTU, at least from a formal point of view. SZOT actions produced a national trade union scene that was evidently less dynamic compared to earlier peaks of women’s trade unionism.

Back then, more than a year before the publication of the lively 1957 WFTU pamphlet, the Hungarian speech for the 1956 World Conference of Women Workers spoke in detail about the multiple severe problems working women confronted in Hungary. This was directly related to ongoing changes in Hungarian women’s politics. A series of party decisions between April and June 1956 – which following the tumultuous Hungarian autumn of 1956 would be reconfirmed in February 1957 – once again gave trade unions responsibility for women’s politics at the workplace (Sipos Citation1996, 329; Szervezési és Káder Osztály Citation1956). The emphasis of the speech of the Hungarian representative at the 1956 World Conference of Women Workers on trade unions as the key institution to address working women’s problems speaks to the intention to use the international platform to re-build Hungarian women’s trade unionism from the shop floor to the national level.Footnote23

The autumn of 1956 changed the Hungarian context fundamentally. Following friction with the WFTU in late 1956 – when (factions of) SZOT likely had vacillated instead of straightforwardly pursuing Moscow-loyal policies (Berán and Kajári Citation1989, 356–60) – SZOT aimed to muster women into the overarching political and stabilization goals of the post-1956 years. SZOT’s national congress, which assembled in February 1958, only a few months after the WFTU’s World Trade Union Congress, issued a vehement appeal to all working women to support various society-wide causes and “with all your talent, diligence, and woman’s heart serve the cause of the big family – the working people” (“Dolgozó nők! Asszonyok! Lányok!” Citation1958).

In March 1958, SZOT issued new Guidelines for trade union women’s work (SZOT NB Citation1958, 42–49). SZOT acknowledged that the “frequent organisational changes” of the past had produced “impatience” and other difficulties hampering workplace trade unions’ work. The Guidelines were fully in sync with the key formal benchmarks of WFTU policies for promoting women’s trade unionism. This concerned the goal that women’s work must “assert itself (érvényesül) in all areas of trade union work,” a focus on “political education” and the “effort (törekvés) that skilled woman … ’ gain positions according to their proportion [in the workforce] in trade union leadership and economic management alike.”

The SZOT Guidelines and other materials produced at the time were devoid of any engagement with practical problems that hindered working women’s full participation and leadership in trade union life, an element fully present in some of the WFTU materials discussed above. SZOT’s women’s committee turned to new popularization strategies, publishing a “booklet” entitled We Speak About Women – We Address Women in 1958 (SZOT NB Citation1958). With a print run of ten thousand copies, the brochure was intended to help trade union Representatives in Charge of Women’s Issues across the country with the “political education” of the working people. Resembling the WFTU’s discourse, which on the international stage mainly assigned representative functions to women trade unionists from state-socialist countries, the booklet embodied this distance from active women’s trade unionism in Hungary. The brochure defined “political education” as “as important” as the representation of interests. But the only reference to actual trade union educational work was contained in the full version of the 1958 SZOT Guidelines, which was included in the booklet. The main content of the brochure was divided into three parts. In a short section entitled “On the Past …,” the iconic leader of the pre-1918 socialist women’s movement Mária Gárdos (born 1885); Mária Palankai (born 1895), who had served in the metallurgical trade union’s central leadership since 1957 (Garamvölgyi Citation1968); and Erzsébet Futó, who was elected to SZOT leadership in September 1956 (“Szervezeti kérdések” Citation1956) discussed their pre-1945 activism exclusively. Next came portrayals of the contemporary struggles of women in the non-state-socialist world, replete with examples from many countries and short quotes from speeches given at the 1956 World Conference of Women Workers. After these sections about the non-socialist Hungarian past and the non-socialist global present followed the third section, “From Our Laws,” which, representing the Hungarian state-socialist present, simply listed the relevant legal regulations concerning women’s work and its protection.

In sum, making use of WFTU approaches to women’s trade unionism in state-socialist contexts on the national level, SZOT ushered in a phase of sterile formality regarding women’s trade unionism in Hungary by the late 1950s.

Fitting into this pattern – in terms of the character of the overall event – the 1959 Nationwide Women’s Conference of the Trade Unions appears as the coda of women’s trade unionism in Hungary in early state socialism.Footnote24 The conference was organized on short notice in the run-up to International Women’s Day; trade union women functionaries belonging to the more activist group that was deeply engaged with the politics of women’s work were not visibly involved. The main speech was given by SZOT secretary Mrs. János Bugár, who was responsible for trade union propaganda and campaign work. In the press, including the main trade union outlets, reporting related to the Nationwide Women’s Conference was scarce. (Népszava 28 February Citation1959; Berán and Kajári Citation1989, 448). SZOT’s flagship journal Munka made a fleeting reference to the Women’s Conference in only one article, a “progress report” from a site visit at Hazai Fésűsfonó, a large textile factory that employed 2,800 women (Pongör Citation1959). The report revealed the workplace-level implications of SZOT’s politics of women’s trade unionism as “translated” by SZOT from the WFTU global stage into the Hungarian national context of the late 1950s. At its core, the report expanded on the most classical of mainstream trade union discourses, construing the woman worker herself – described as unwilling and unfit to make use of all the opportunities offered to her – as the principal reason trade unionism did not work for her and why she was incapable of benefiting from either education or progress. Following this example, the report explained that women workers in the Hazai Fésűsfonó largely ignored various devices and schemes implemented for them in the factory including a sewing machine, a take-home pre-cooked dinner option, and a cleaners’ shop. This was not the “fault” of the trade union committee and the management; rather, it showed “that women are often backward, unable to take advantage of all the opportunities.” The same was true for the educational openings available to workers. Of the nine hundred to one thousand women who – having grown up before socialism – had no more than four to six years of schooling, “only 15 signed up for evening school!” True, many of them were commuters, and this constituted an objective difficulty; nevertheless, “there are also distance learning courses and educational lectures. Unfortunately, even these are not attended.” A large majority of women workers did not care or had different, dubious, priorities, and as a result, “those come to the fore who practically abuse (szinte visszaél) the possibilities offered by the people’s democracy.”

At Hazai Fésűsfonó, the reporter also met the worker Mrs. István Földi, who as a speaker at the Nationwide Women’s Conference had been “very successful” with her “simple, heartfelt words.” Serving as the rare counter example of an aspirational and educated everyday heroine successfully juggling all balls at once, Mrs. Földi was depicted in the illustration of the article as “screening the performance of Mrs. Sándor Magó, spinner.”

Women’s trade unionism in the period strongly surfaced as a top-down activity more exclusively aimed at governing and disciplining women workers and, in all likelihood, remained, a less lively arena of women’s trade union action, at least on the national level.Footnote25 In February 1960, the WFTU published a report by SZOT secretary Mrs. János Bugár, who claimed that “after the counter-revolution” it had taken time for “cultural life” to regain its dynamism, adding that “[i]t is doubtless, however, that women’s participation has advanced though more slowly, and with greater difficulty” (Bugar [Bugár] Citation1960). The WFTU credo that women’s trade union work was to form an “integral part” of all trade union activities in Hungarian practice brought about the marginalization of women’s trade unionism. Until well into the 1960s there would be few traces (in the multiple archives I have consulted so far) of the activities of SZOT’s women’s committee.

Conclusion

The politics of promoting women’s trade unionism discussed in this article formed part of a cross-Iron Curtain, global, multi-scale history of women’s trade unionism. The WFTU’s emphasis on spurring women to trade union action in the middle of the 1950s was driven, insofar as the men-dominated leadership was concerned, by a combination of motives. Exchange between women from across the globe was aimed not only at promoting communist-aligned activism in capitalist and post/colonial countries. Such exchange was also regarded as a less-politicized programme that lent itself to promoting top-level political collaboration across ideological divides, a key policy goal of the WFTU during the period. The WFTU considered issues regarding women’s work an innocuous platform for their hoped-for politics of collaboration with the ICFTU and the International Federation of Christian Trade Unions, and it intended to lend political weight to this endeavour through a visible upsurge of communist-aligned international women’s trade unionism. Finally, the WFTU, as it advocated women’s full equality, globally sought to showcase the progressive character of the state-socialist project.

WFTU-aligned women trade unionists took the chance, just as their colleagues did in the ICFTU. Here, as Dorothy Sue Cobble (Citation2021, 320–327) has shown, the scope of action for dedicated women widened dramatically in response to WFTU overtures; ICFTU women aimed to actualize and expand, with partial success, the new opportunities opening for them as the ICFTU reacted directly to what it considered “the climax” of an obstinate and mendacious WFTU campaign (“Preparatory Committee” Citation1956): the WFTU preparations for the World Conference of Women Workers. The international documents produced by the WFTU at the time speak to its serious and informed engagement concerning the real-life obstacles to women’s participation in trade union life and practical measures to overcome them,Footnote26 just as was the case at the ICFTU.

Women’s trade unionism stemming from the state-socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe confronted difficulties on the growing international stage of women’s WFTU-aligned trade unionism. Central and Eastern European women trade unionists acquired institutional standing and presence on the international stage, in the first place, as representatives of the advanced status of working women in the countries “building socialism.” Within an international policy framework that did not put centre stage their trade unionist practices, the de facto struggles of these women in their respective domestic contexts were present only to a limited degree. This concerned the formats and activities of trade union work for women in which they were engaged – especially in enterprises and at their workplaces, and in the variegated domestic contexts in the state-socialist countries, which either could be conducive to or hindered women trade unionists’ position and influence in the management of women’s work and their (trade union women’s) engagement with women workers’ problems.

Still, women trade unionists from the region partook in the new international politics of spurring women into action. They gained international standing and additional experience, and they aimed to make use of the international platform provided by the WFTU to advance their domestic agendas. Hungarian policies for mobilizing women into trade unions and providing trade union training for them were closely intertwined with both economic and political needs and the interests driving the project of “building socialism” while, at the same time, shifting their emphasis and changing formats as they addressed specific tasks. The rapidly growing female labour force played an important role in this project and was subjected to significant burdens as it was put into the service of this project. Women trade unionists, who while dedicated to the project of ”building socialism” aimed to alleviate some of these burdens, repeatedly encountered the entrenched disinterest of the main actors and their unwillingness to engage substantively on the issue of improving the position of women at the socialist workplace as compared to men. Regarding the resistance they encountered in their struggle for substantive improvement of the condition of women workers, the experience of Hungarian women trade unionists, again, was rather similar to that of their many trade colleagues around the world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Susan Zimmermann

Susan Zimmermann is a historian of labour and gender politics and movements in the international context and in Austria-Hungary. Her most recent monograph (in German) is Women’s Politics and Men’s Trade Unionism: International Gender Politics, Women IFTU-trade Unionists and the Labour and Women’s Movements of the Interwar Period (Löcker Verlag 2021), and together with Eloisa Betti, Leda Papastefanaki and Marica Tolomelli, she co-edited Women, Work, and Activism. Chapters of an Inclusive History of Labor in the Long Twentieth Century (CEU Press 2022). She holds the European Research Council Grant “Women’s Labour Activism in Eastern Europe and Transnationally, From the Age of Empires to the Late 20th Century” (Acronym: ZARAH).

Notes

1. I would like to thank Selin Cagatay and Olga Gnydiuk, who have made important material related to the WFTU available to the ZARAH team, and also the ZARAH team for their discussion on the long version of the present (abbreviated) text. All translations into English are mine, including (re-)translations of WFTU materials I was able to access in other languages.

2. The formal title of the 1956 conference did not carry the misnomer “first.” Yet the WFTU made a great effort to present the conference as no. 1. The various editions of the special supplement to the WFTU journal World Trade Union News carried the title “Towards the First World Conference of Women Workers!” in several issues published in the run-up to the conference, and the WFTU similarly used as section title “The 1st World Conference of Women Workers” in its activity report. The formal title of the 1947 conference in Hungary, just like the WFTU’s misleading statements, ignored pre-World War II histories of women trade unionists’ organizing. In 1959, the leading Hungarian papers refrained from, once again, using the misnomer.

3. Similar shifts happened in other state-socialist countries too, but with different timing. See, e.g., Jarska Citation2018.

4. Women activists and functionaries were repeatedly advised or directed to follow the changes; for trade union women this meant they were asked to move into MNDSz structures when MNDSz acquired a greater role in the workplace (see, e.g., Berán and Kajári Citation1989, 110). There is ample documentation that indicates such changes were not easy, were unwelcome, or did not work out at all.

5. Some of the leading trade union women, including Dankó, had participated in the movement already in the interwar period (Anyáink, Asszonyaink, Leányaink Citation1958; “Piroska Szabó” Citation2023).

6. In the original material documenting the structure, discourse, and practices shaping the work of the Hungarian women trade unionists, direct reference to the “Soviet connection” is scarce (e.g., “Jegyzőkönyv” Citation1949a). Further research is needed to establish in a more specific manner the associated travel of organizational principles of communist-led trade union training and trade union work with a focus on women’s trade unionism and trade union work within Central and Eastern Europe including, of course, the Soviet Union.

7. After early signs of a rift in late 1947, the de facto split between the (pro)communist and anticommunist camps within the WFTU took place in January 1949. The strongly anticommunist International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) was founded in December 1949 (Bosch Citation1983, 60–64; Devinatz Citation2013, 348–349, 351–354).

8. The proposal to establish a higher-level entity equipped with three rooms, its own telephone, and a division head (Mrs. Pál Bodonyi was suggested) was dated June 1952. According to Schadt, the division head became a member of the SZOT Presidency and Secretariat with consultative status (SZOT Szervezési Osztály Citation1952; Schadt Citation2007, 177).

9. I do not discuss women workers’ resistance against the strained efforts to increase their productivity, which was encountered and recorded by the trade union women, for which there is ample documentation.

10. SZKL 2. F. 19, 1952, box 1, folders 1 and 2, PIL, contains rich documentation.

11. This is not to say that the WFTU did not support women’s trade unionism before 1953. When the – still united – WFTU deeply engaged with the issue of equal pay in 1948, its detailed “Statement of Principle and Survey of the Question of the Remuneration of Female Labour” included a section advocating for women’s trade unionism; the “one thing certain” was that women’s own initiative, as well as “a great campaign” to be organized to “encourage women to join trade union organisations in large numbers,” were key to overcoming the manifold obstacles to wage equality (WFTU Citation1949, 416–417). When at the height of political tensions around the ongoing split the WFTU’s second world congress assembled in summer 1949 in Milan, speeches by women trade unionists from Central and Eastern European countries were enlisted, which pointed, e.g., to key social developments advancing the status of women workers in their countries (WFTU Proceedings Citation1949, 169–172, 353–355). After the split and until 1953, women’s trade unionism was much less emphasized.

12. The photograph, published in Als wenn Ihr dort gewesen wäret (Citation1953), was kindly provided by the Swedish Labour Movement’s Archives and Library, Stockholm.

13. A contemporary propaganda brochure gives 1951 as the year when the WFTU turned to “‘smile’ tactics” also in its relations with the ICFTU leadership (Facts Citation1957, esp. 27). Lichtblau’s article, while heavily driven by anticommunist ideology, gives relevant information about the WFTU during the period, including the varieties of the “unity of action” strategy; the author claims that at the time of writing, the from-above variant again became more important “wherever this is feasible, especially in the Afro-Asian countries.”

14. A renewed emphasis on working women’s rights is documented in the WFTU monthly World Trade Union Movement from the middle of 1953 onwards; this was directly connected to the strong emphasis on this large topic, which characterized the WIDF-led World Congress of Women held in Copenhagen in June that year. The WFTU closely engaged with the event and the Declaration on the Rights of Women adopted by the Copenhagen Congress (World Trade Union Movement [8, April 16–30] Citation1953: 30–32; [14, July 16–31] Citation1953: 12–15; [1, January 1–15] Citation1954: 14–15). I have not yet been able to explore this connection further, and the specific reasons for the WIDF’s turn to this topic and the related mutual engagement between the WFTU and WIDF.

15. Other committee members included women, and some men, from Western and Eastern Germany, Sweden, Great Britain, Italy, France, Japan, and India. A Hungarian participant is mentioned in an inconsistent manner and was not included in the list contained in the Hungarian archival material which lists names; it lists “TROJANOVA” (secretary, Czechoslovakian trade union federation), “BANU Ileanu” (Romanian trade union federation and health workers’ trade union), and “MOTOVA” (secretary, greater Moscow central council of trade unions.

16. Women from Bucharest, Romania likewise reported that they were “taking action … to improve the arrangements for women to qualify and gain promotion to posts of responsibility in their trades and in the unions.” In addition, they “organised an exhibition showing different aspects of the struggle of women workers in our own and other countries, for peace and a better life; and a series of ten films. From May 15 to June 20 there will be a radio programme entitled Women Worker’s Hour.” (Supplement, May Citation1956, 9–10).

17. The document quoted here does not give the name of the speaker. According to one document, Hungary planned for 41 delegates; the delegation was to be led by Gizella Hegyi (Lackó Citation1956).

18. I have not yet been able to identify the resolution as adopted. It is neither contained in the documents issued by the WFTU (WFTU Citation1957) nor in Ganguli Citation2000.

19. For some time, Grassi and the women’s division in the WFTU Secretariat were still mentioned after the Women’s World Conference. Teodorescu served for many years as one of the WFTU’s secretaries, functioning as a full-time employee at the WFTU Secretariat. Here she was responsible for and played a highly visible role in the WFTU’s liaison activities with the ILO, the UN, and other international organizations. Teodorescu was replaced by Stana Dragoi in March 1964, only a few weeks before the opening of the 2nd International Trade Union Conference on the Problems of Working Women in Bucharest; Teodorescu had played an important role in the planning of this conference (Előre, 22 March Citation1964; Alvarado Citation1956; Facts Citation1957, 20–22). In 1960, Irena Brzozowska, secretary of the Polish trade union federation, and Tatjana Nyikolajeva, secretary of the Soviet trade union federation, are mentioned as members of the WFTU General Council and the WFTU Executive Committee, respectively (Nyikolajeva Citation1960).

20. The delegation also included the Permanent Representative of the WFTU to the ILO and the UN’s European Office.

21. With the exception of the term “encouraging,” the quotes indicate the precise wording of the Executive Committee’s original decision.

22. So far, I have not been able to find a full list of participants.

23. Related SZOT guidelines would indeed be issued in August 1956 (Szervezési és Káder Osztály Citation1956).

24. I have not been able to establish with certainty the specific context(s) of the organization of the conference. Several speakers’ contributions, in part handwritten, are preserved in the SZOT archives.

25. Two brochures, published in 1961 and 1962, respectively, illustrate some of these restrictive tendencies. One gave the curriculum and contents of a one-day training course for “women’s committee activists”; the other brochure, published in the series “Handbooks of the Trade Union Activist,” summarized the “tasks” of the trade union women’s committees (SZOT Citation1961; Sőtér Citation1962).

26. Further research needs to and can be done to flesh out the interests, interventions, and activities of key women trade unionists from Central and Eastern European countries in the WFTU, the ILO, the UN, and other international arenas. I hope that this article can serve as a springboard for this work.

References

- “1.011/1951, MT.” = “A Magyar Népköztársaság minisztertanácsának 1.011/1951. (V. 19.) számú határozata.” 1951. Magyar Közlöny (May 19): 438–440.

- “153/7/1951, N. T. sz. A termelésben résztvevő nők számának emelése.” 1951. A Népgazdasági Tanács Határozatainak Tára (May): 174–178.

- “1949. február 4-i értekezlet” [this item clusters several documents]. February 4, 1949 [date of meeting]. Szakszervezeti Levéltár Szervezés (Nőmozgalom) (= SZKL in the following) 2. f. 19, 1949, box 1, folder 3. (Politikatörténeti Intézet Levéltára (= PIL).

- “A Dolgozó Nők Világkonferenciája Előkészítő Bizottságainak tagjai.” SZKL 2. f. 19, 1954–1960, box 1, folder 2. PIL.

- “A SZOT Elnökségének határozata az üzemi MNDSz szervezetek megszüntetésével létrehozandó nőbizottságokkal kapcsolatban.” May 19, 1952. SZKL 2. f. 19, 1952, box 1, folder 1. PIL.

- Als wenn Ihr dort gewesen wäret. 3. Weltgewerkschaftskongress [1953] (= Die Weltgewerkschaftsbewegung, double issue 21/22 [1953]). Collection No. 3373, Fackliga Världs Federation En, box 3. Swedish Labour Movement’s Archives and Library (= ARBARK), Stockholm, Sweden.

- Alvarado, L. 1956. “The Director General.” November 22, 1956. Z 1/1/1/22 (J.1), International Labour Office, Archives (= ILOA).

- “Anyáink, Asszonyaink, Leányaink.” 1958. Vasas. A Magyar Vas- és Fémipari Dolgozók Szakszervezetének Lapja. March 1, 1958. Arcanum Digitális Tudománytár / Arcanum Digital Sciences Database (= ADT).

- “Az SZVSZ Elnöksége 29. ülésszakának határozata.“ 1956. A Szakszervezeti Világszövetség Hírei (April): [1].

- “Az SZVSZ Titkárságának első sajtófogadása.” 1955. A Szakszervezeti Világszövetség Hírei (December): 16–17.

- Bars, S. 1949. “Nőtitkárság 1949, március 1-i osztályértekezletének határozatai.” March 1, 1949 [date of meeting]. SZKL 2. f. 19, 1949, box 1, folder 4. PIL.

- Belényi, Gy., ed. 2000a. A nők munkába állításával kapcsolatos tapasztalatok. A SZOT jelentése. Oktober 14, 1951. In Munkások Magyarországon 1948–1956. Dokumentumok, 183 -186. Budapest, Hungary: Napvilág Kiadó.

- Belényi, Gy. ed. 2000b. “A szakszervezeti mozgalom munkájának mérlege 1948 őszén s feldatai az új helyzetben. Apró Antal feljegyzése.“ In Munkások Magyarországon 1948–1956. Dokumentumok 58–74. Budapest, Hungary: Napvilág Kiadó.

- Bell, E. 1956. “World Conference of Women Workers. Vienna, 14–17 June 1956.” Z 1/1/1/22 (J.1), ILOA.

- Berán, Mrs. (Beránné) É. Nemes, and E. Kajári, eds. 1989. Útkeresés. 1953–1958. Vol. 9, A magyarországi szakszervezeti mozgalom dokumentai. Budapest: Népszava.

- Boris, E. 2018. “Equality’s Cold War. The ILO and the UN Commission on the Status of Women, 1946–1970s.” In Women’s ILO. Transnational Networks, Global Labour Standards and Gender Equity, 1919 to Present, edited by E. Boris, D. Hoehtker, and S. Zimmermann, 97–120. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Bosch, G. K. 1983. The Political Role of International Trades Unions. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bugár [Bugar], Mrs. (Bugár Jánosné). 1960. “Hungary. How Working Women are Realizing Equality with Men.” [reprint of extracts, in English translation, from Revue Syndicale Hongroise, December 1959]. International Bulletin of the Trade Union and Working Class Press. (7, February 1–15): 4.

- Cobble, D. S. 2021. For the Many: American Feminists and the Global Fight for Democratic Equality. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Cseterki, L. 1954. “Feljegyzés Kristóf elvtársnak.” January 18, 1954. SZKL 2. f. 19, 1954–1960, box 1, folder 1. PIL.

- Déri, Mrs. (Déri Ernőné). 1970. “A nők egyenjogúsításának 25 éve.” Munka. A szakszervezeti mozgalom folyóirata 20 (2): 28–29.

- Devinatz, V. G. 2013. “A Cold War Thaw in the International Working Class Movement? The World Federation of Trade Unions and the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, 1967–1977.” Science and Society 77 (3): 342–371.

- “Dolgozó nők! Asszonyok! Lányok!” 1958. Munka. A szakszervezeti mozgalom folyóirata 8 (3–4): 34.

- ”Drága Barátnőink! Kedves Elvtársak!” [draft of oral contribution of Hungarian representative delivered after hearing the two main speeches]. [1956]. SZKL 2. f. 19, 1954–1960, box 1, folder 2. PIL.

- Előre, September 10, 1957; March 22, 1964. (ADT).

- Facts about International Communist Front Organisations. April, 1957.

- “Feljegyzések Gács elvtárs részére.” May 14, 1949. SZKL 2. f. 19, 1949, box 1, folder 1. PIL.

- Fidelis, M. 2010. Women, Communism, and Industrialization in Postwar Poland. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Fracon, B. 1955. “Néhány sürgős, megoldásra váró kérdés. Benoit Frachon, a Francia Általános Munkásszövetség (CGT) főtitkára beszédéből.” A Szakszervezeti Világszövetség Hírei (February): 19–20.

- Ganguli, D. 2000. History of the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU). New Delhi: D. Ganguli on behalf of World Federation of Trade Unions.

- Garamvölgyi, G. 1968. “Arckép.” Csili (4): 7. (DT).

- “General Resolution. Draft Adopted by the Commission. 1st. World Conference of Women Workers (Budapest, June 14–17, 1956.” Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, (KCLMDA), Collection No. 5595, box 3, folder 20. Cornell University Library (CUL), Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, United States of America.