ABSTRACT

Existing research reveals the existence of objective (factual) and subjective (perceived) political knowledge among voters. However, we know little about their determinants, especially among people who have not voted before. This article aims to explain the factors influencing the objective and subjective political knowledge of first-time voters. Our analysis uses individual level data from an original survey conducted in the aftermath of the 2019 presidential elections in Romania on 664 first-time voters. The study distinguishes between three components of knowledge – motivation, ability and opportunity – and argues that they may have divergent effects. The empirical evidence based on ordinal logistic regression only partially supports these theoretical expectations, but it does reveal a rich picture.

Introduction

Knowledgeable citizens can contribute to the quality of democracy in a country. They are usually attentive to politics, engaged in various forms of participation, committed to principles, opinionated, engaged and able to ensure the representation of their interests (Anderson Citation1964; Banwart Citation2007; Christensen Citation2018). Political knowledge has impact on the political system because it gives people the power to control and improve political conditions. It is thus essential to a well-functioning democracy. Political knowledge has three core elements: motivation, ability and opportunity (S. Lee and Xenos Citation2019). The variation of these elements generates two types of political knowledge: objective and subjective. Objective or factual knowledge is defined as the range of factual information about politics stored in someone’s long term memory (Carlson et al. Citation2009). Subjective or perceived knowledge refers to individuals’ degree of confidence and self-perception about how much they know (Aertsens et al. Citation2011; Schäfer Citation2020).

So far, research has analysed the differences between objective and subjective political knowledge, how these can produce an impact on various behaviours, e.g. in terms of political participation, and how these two types of political knowledge are formed. Earlier studies show the importance of civic and university education or media exposure in acquiring political knowledge. For example, exposure to different types of media such as newspapers or radio leads to higher levels of political knowledge (G. G. Lee and Cappella Citation2001). Also, the transition from traditional media to social media changes the ways in which citizens learn about politics (Ekström and Shehata Citation2018). In spite of the extensive attention paid to the emergence of objective and subjective political knowledge, we still know little about what determines these types of knowledge among first time-voters. These are citizens who do not carry with them experiences and assessments from previous interactions such as information bias (including echo chambers), party identification, or socialization with candidates and with political processes in general.

To address this gap in the literature our article aims to explain the effect of motivation, ability, and opportunity on the objective and subjective political knowledge of first-time voters in the 2019 presidential elections in Romania. We seek to understand the circumstances in which these young voters acquire information or perceive that they have information. Our case selection regarding the country and election rests on three grounds: the Romanian presidential elections are popular contexts, with turnout that is regularly higher than for parliamentary elections; the 2019 elections came after three years of tensions between the government and the country president; and young people had been actively engaged in Romanian politics in the recent period. We distinguish between the three components of knowledge – motivation, ability, and opportunity – and argue that they have divergent effects. First, we hypothesize that political interest, importance of elections and following campaigns are likely to boost objective more than subjective knowledge. Second, we expect that acquiring information from traditional media (TV and newspapers) and online news can enhance subjective political knowledge more than objective political knowledge. This can be partially linked to the issues of fake news and disinformation that we discuss further in the article.

Our analysis uses individual level data from an online survey conducted in November-December 2019 on 664 first-time voters. The survey includes young people who were eligible to vote for the first time in this election at national level and who actually voted. We restrict the sample of respondents to actual voters because these are politically active citizens who are likely to use their knowledge to inform their voting decision. The identification of drivers for objective and subjective knowledge among future generations of voters has both scientific and societal relevance. At the scientific level, the analysis can reveal if the sources of the two types of knowledge are similar. If that is the case, then the objective and subjective knowledge are closely related, and this diminishes the risk of observing Dunning-Kruger or impostor effects in the population. At the societal level, the identification of the sources of objective and subjective knowledge may help to inform a series of stakeholders in their communication with citizens. For example, political parties during campaigns will know how to shape their message and what to emphasize depending on how far people’s perceptions of what they know are from what they actually know. If this discrepancy is large, then more room is left open for manipulation and the use of misinformation during election campaigns.

The first section of the article reviews the literature and formulates six testable hypotheses. Next, we present the research design with an emphasis on the data and methodology. The third section sets out the analysis and interpretation of the main findings in relation to the empirical realities in Romania. The conclusion reflects on the implications of this analysis for research on political knowledge and discusses avenues for further research.

Motivation, ability, and availability

This section builds on the three core elements of political knowledge and formulates two sets of hypotheses. On the one hand, we argue that motivation and ability contribute to objective political knowledge to a larger extent than to subjective knowledge. We identify three potential determinants: political interests, perceived importance of elections, and campaign following. On the other hand, we argue that availability favours the increase of subjective knowledge to a larger extent than objective knowledge. In this sense, the sources of information can play a decisive role.

Causes of objective knowledge

Citizens’ political interest has an important role in managing political behaviour, especially in terms of their political engagement, and is thus important to the functioning of contemporary representative democracies. Political interest is usually described as the extent to which politics is attractive to people (Dostie-Goulet Citation2009), or as citizens’ willingness to pay attention to political phenomena (Lupia and Philpot Citation2005). It involves curiosity towards and familiarity with policies, political institutions, politicians, or political processes. When applied to politics, interest can provide individuals with the motivations they need to make a choice.

Political interest can feed both objective and subjective political knowledge, but we expect this to happen considerably more for the former than the latter. In terms of objective knowledge, people with a high interest in politics are more likely to actively seek information about the political system. Interest drives their desire to acquire information from various sources, and to engage in debates and discussions (Dubois and Blank Citation2018). Their interest will also codify the information in facts that can be written down, easily learned, or diffused (Groza, Locander, and Howlett Citation2016). Regarding subjective knowledge, people with high political interest may have a higher self-assessment of what they know about politics. The feeling of knowing can originate in gathering more information about political facts, along with personal experiences or prior knowledge.

However, it is possible that some people with high political interest may overestimate what they know and not update their information. This could happen because they see themselves as more competent than they are and may have a low level of political knowledge. As a corollary, individuals’ perceptions about their knowledge differ from an objective assessment of ability (Liu et al. Citation2007; Sullivan, Ragogna, and Dithurbide Citation2019). Those with high levels of political interest may neglect obvious information, have inaccurate self-perception, and overestimate the depth or accuracy of their knowledge about a certain political issue. Self-perceived knowledge has a limited value until is substantiated by facts (Lehmann Citation2005). Those with a high level of political interest often have higher exposure to information. They may overestimate their knowledge, but their political interest makes them open to new information that might change their views. Consequently, we expect that:

H1:

The first-time voters with high levels of political interest will have more objective than subjective knowledge.

Election campaigns are the main arena in which politicians and voters interact before the elections take place. They centre around communication and acquiring information (Lipsitz et al. Citation2005). During a campaign, voters have access to a large amount of information, and get to know details about the candidates, such as their policies and stances. There are two categories of voters: those who look for factual information in official documents (encyclopaedic voters) and those who acquire information via shortcuts like discussions with co-workers or friends, political parties, or other groups (Lupia Citation1994). Encyclopedic voters are often interested in the subject of the election and are likely to acquire objective knowledge. They often take advantage of the amount of information available online and may consult open sources (grey literature) such as legal documents, reports, or scientific papers related to parties and campaigns. This behaviour may mean they are less vulnerable to disinformation or manipulated messages, and may enhance their knowledge. Encyclopaedic voters will better understand the power of their vote as they have factual information about it and possess the required tools to make a rational choice. A voter with a high level of objective knowledge will often decide which candidate or option to vote for based on the researched facts and data, and with limited subjectivity.

At the same time, voters who get their information through shortcuts feel confident about their knowledge and have the feeling that they understand elections. Traditional and social media are known for spreading subjective messages and sometimes inaccurate content (Anspach, Jennings, and Arceneaux Citation2019; Guo, Chao, and Lee Citation2019; Schäfer Citation2020). Exposure to media channels contributes to self-perceived knowledge (Mondak Citation1995; Park Citation2001) due to the reasons mentioned above, to which we can add the role of emotions. For these types of voters, the use of shortcuts and subjective sources of information can be justified by the low saliency of elections for them. Thus, we expect that:

H2:

The first-time voters who consider elections to be important will have more objective than subjective knowledge.

Election campaigns convey a large amount of political information because political parties and politicians compete to inform voters about themselves, the values they stand for, and how they plan to address important issues in the future. In doing so, the campaigns cover current political issues, send simplified messages to voters, open the door to political discussions with friends and acquaintances, sometimes offer facts and data, and provide the possibility to learn about candidates (Lau and Redlawsk Citation2006; Nadeau et al. Citation2008). As such, people who pay attention to the campaign are likely to increase their objective knowledge. Earlier research illustrates that some people use election campaigns to acquire information about candidates (Redlawsk Citation2004). At the same time, the existence of negative rhetoric in many elections (Lipsitz and Geer Citation2017; Nai Citation2020) can enhance objective knowledge. Negative campaigning is characterized by attacking opponents both on personal and professional grounds, which means that it provides additional information about the candidates and issues (Kahn and Kenney Citation1999). In this sense, voters receive new information that conflicts with their existing knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about a certain candidate or party (Lilleker Citation2014). All these contribute to higher levels of objective knowledge. Following all these arguments, we expect that:

H3:

First-time voters who follow campaigns will have more objective than subjective knowledge.

Causes of subjective knowledge

Previous research shows that the average citizen possesses limited knowledge about public affairs. The media provide citizens with opportunities to access and acquire information (Carpini, Michael, and Keeter Citation1991). When voters live in a media scarce environment, the levels of knowledge decline (Mondak Citation1995). Even though the media environment has changed in recent years regarding information on political topics, newspapers and TV continue to be rich sources of political content (Goldberg and Ischen Citation2020; Hollander Citation1995; Wagner and Elena Citation2017). TV and newspapers continue to be relevant sources of political information despite the threats of disinformation and fake news. This happens because they are considered to represent one-way, top-down, sender-driven, time-specific routes through which news consumers can receive the information provided by news organizations and professional journalists (Ekström and Shehata Citation2018). Those who watch TV and read newspapers have the perception of being knowledgeable and capable of judging political issues because they believe that the TV channels and newspapers are legitimate sources of information. However, news media may mislead the public into feeling informed rather than actually informing it (Park Citation2001), and they tend to frame politics as a strategic game rather than focusing in depth on political issues (Aalberg, Strömbäck, and de Vreese Citation2012).

The way in which information is framed makes that information more noticeable, meaningful, or memorable to audiences (Segvic Citation2005). It involves emotions, certain perspectives, and a subjective representation of reality (Entman Citation1993; Entman, Matthes, and Pellicano Citation2009). Exposure to framing may create an illusion of information, as people may overestimate their degree of political knowledge (Anspach Citation2017; Weber and Koehler Citation2017) and refrain from seeking additional information on political issues (Hollander Citation1995).

In some instances, the media can enhance objective knowledge, but these are rarer than subjective knowledge. For example, when citizens are interested in the topic or have pre-existing knowledge about it, they may watch TV and read newspapers to gain supplementary information and become more knowledgeable (Prior Citation2005). TV and newspapers can provide in-depth analyses of a particular event, introduce savvy political commentators, and enable direct experiences with current events or political figures. In spite of these potential benefits, there is little evidence to indicate that TV and newspapers increase objective political knowledge. Instead, the coverage and framing of particular news stories increases confusion and generates apathy (Feldman Citation2016). Therefore, we expect that:

H4:

The first-time voters who use TV for their political information will have more subjective than objective knowledge.

H5:

The first-time voters who use newspapers for their political information will have more subjective than objective knowledge.

Meanwhile, unlike TV and newspapers, social media content is a multi-feed, algorithm filtered, personalized activity. It exposes people to news whether or not they actively seek it (Gil de Zúñiga, Weeks, and Ardèvol‐Abreu Citation2017). The Internet reinvigorates political knowledge because it creates opportunities to access and acquire information (Anspach, Jennings, and Arceneaux Citation2019; Gil de Zúñiga, Weeks, and Ardèvol‐Abreu Citation2017). Through online sources, citizens can engage in information acquisition at a reduced cost, acquire information faster, have unmediated access to facts and figures, and may even engage in a political dialogue/exchange of ideas with a virtual social network that would not be accessible otherwise. In theory, social media can contribute to the creation of well-informed citizens with greater political knowledge.

In spite of these apparent strengths, social media also has the potential to influence subjective knowledge, for several reasons. First, the echo chambers created in social media mean that people will generally be exposed to a large extent to pro-attitudinal communication (Boulianne, Koc-Michalska, and Bimber Citation2020; Flaxman, Goel, and Rao Citation2016). The selective exposure to personalized content, characterized by like-mindedness (Sunstein Citation2001), leads to political similarity in information (Boulianne, Koc-Michalska, and Bimber Citation2020). In essence, individuals who find themselves in echo chambers perceive that their level of knowledge is increasing, while in reality they are simply receiving different versions of the same information that they already favour. Second, and partially related to echo chambers, social media content can be highly repetitious. The more that people hear about a topic, even if it is the same information, the more familiar they believe they have become with it. Familiarity creates overconfidence (Schäfer Citation2020) and leads to the perception of knowing more. Overconfidence often results in a lack of interest in the acquisition of political knowledge (Ortoleva and Snowberg Citation2015). Overconfident people often stop searching for information to cope with the overload of information and consider themselves informed (Ortoleva and Snowberg Citation2015). Third, social media are identified as the main gateway through which people are exposed to fake news (Allcott and Gentzkow Citation2017; Rhodes Citation2022). In the absence of mechanisms to challenge misinformation and identify fake news, social media can give the illusion of knowledge without contributing in reality to it. As a result, we expect that:

H6:

The first-time voters who use social media for political information will have more subjective than objective knowledge.

In addition to these main effects, we control for two variables that can produce an effect on voters’ types of political knowledge: the left-right self-placement, and the degree of political participation.Footnote1 First, depending on how voters position themselves on the political spectrum, they may be more inclined to gain objective versus subjective knowledge. Second, voters who are politically involved may have higher levels of objective knowledge. Their connectivity to various events, frequent involvement in decision-making processes, and active attitude towards politics can make politically involved voters more attentive to what is happening around them. Or, on the contrary, they may have higher levels of subjective knowledge if they consider that their degree of activity is equivalent to knowledge – meaning that they may stop seeking factual information.

Research design

This article uses individual-level data from an original online survey conducted among Romanian first-time voters in November-December 2019. The survey was launched immediately after the second round of the presidential elections and closed three weeks later. The survey includes 664 young people who voted in the presidential elections. The respondents were born between 1999 and 2001, which meant that they were entitled to vote in national elections for the first time. Our analysis focuses on first-time voters in the Romanian presidential elections for two reasons. First, we want to understand the effects on voters who are presumed to have limited political knowledge. By definition, first-time voters have not experienced voting before and thus do not use their political knowledge in elections. Second, Romanians elect their president through a popular vote and turnout is usually higher than in the legislative elections. This is the election in which political knowledge can be used more than in other types of elections (such as legislative, local).

The survey uses maximum variation sampling. In the absence of official reliable statistics regarding the profile of young voters, the features of the entire population cannot be known, and thus no representative sampling can be drawn. Maximum variation sampling is a purposive sampling technique used to increase the variation in several key variables. In our case, there is great variation in the respondents’ profile across all the variables included in this analysis (Appendix 1). Such a sampling strategy confines the findings presented in this article to our respondents, i.e. there can be no generalization to a broader population. Nevertheless, we consider the results to be highly informative and to have important implications for the study of first-time voters and types of knowledge. The respondents were neither pre-selected nor part of a pool of available individuals. We distributed the online survey mostly through messages on Facebook groups or discussion forums, and emails sent to organizations or associations. The dataset only included the respondents who completed the survey. The questionnaire was in Romanian and the average time needed for completion was nine minutes.

The dependent variables of this study are objective and subjective knowledge. Objective knowledge is a cumulative index based on five questions about Romanian politics that respondents were asked to classify as true or false. These questions were about the country’s EU membership, the length of the Romanian president’s term in office, the co-habitation between president and prime minister, the bicameral structure of the Romanian parliament, and whether the government must resign after a vote of no confidence in parliament. All correct answers were coded 1, while the incorrect ones were coded 0, resulting in a six-point ordinal scale with values between 0 and 5. Subjective knowledge is measured on a five-point ordinal scale as per the answers to the following question: ‘In your opinion, how well informed are you about what happens in Romanian politics?.” Answer options ranged between “not at all” (coded 1) and “very much” (coded 5).

Political interest (H1) is measured on a five-point ordinal scale based on the following question: “How interested are you in Romanian politics.” The possible answers ranged between “not at all” (1) and “very much” (5). The importance of elections (H2) is operationalized as the answer to the question: “How important were the 2019 presidential elections for you?.” The answers were recorded on a four-point ordinal scale with values between “not at all” and “very important.” The level of campaign following (H3) is measured on a similar scale with H1 as the answer to the question: “To what extent did you follow the campaign for the presidential elections in November 2019?.” The remaining three independent variables (H4-H6) are measured on a five-point ordinal scale using the answers to the question “How often do you use TV/newspapers/social media as sources as information?.” Possible answers ranged between “never” and “daily or almost daily.” The first control variable is the self-placement of respondents on an 11-point left-right axis where 0 stands for left and 10 for right. The degree of political participation is measured on a four-point ordinal scale. It is a cumulative index of three possible actions: voting in referendums, protesting, and signing petitions (both online and offline). The index takes values between 0 for no involvement in any of these, and 3 for engagement in all three activities.

For all the variables, the “DK/NA” answers were treated as missing values and excluded from the analysis. The analysis uses ordinal logistic regression to test the main hypothesized effects (see Model 1 in Appendix 2), and also includes the controls (see Model 2 in Appendix 2). Before running the regression, we tested for multicollinearity and the results indicate no highly correlated predictors, as the highest value is 0.49. This is also reflected by the values produced by the VIF test for multicollinearity, which are smaller than 1.67.

Analysis and results

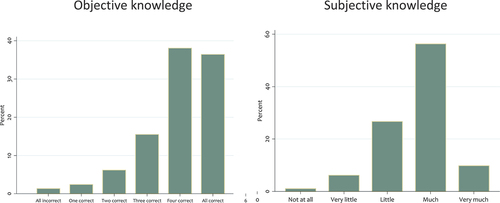

The distribution of objective and subjective knowledge () provides some preliminary insights into the profile of Romanian first-time voters. The percentages for objective knowledge reflect that a large share of the respondents provided correct answers to four or five of the items. Very few of them did not answer any question correctly, or only provided one or two correct answers. Overall, the young voters who took part in the survey can be said to possess high levels of knowledge about Romanian politics. This result is quite intuitive since we may expect that those who vote for the first time will gather information that can help with their choice. Very few respondents identified no or one correct answer.

More than half of the respondents assessed their knowledge to be good. The bars for subjective knowledge indicate that roughly one quarter of the surveyed first-time voters claimed to have little knowledge of Romanian politics. Very few were at the extremes in claiming none or very high levels of knowledge. The distribution for both types of knowledge is skewed to the right, which could imply that they are highly correlated. The Spearman correlation coefficient between objective and subjective knowledge is positive (0.32) and statistically significant at the 0.01 level. However, this value is not as high as might have been assumed from the aggregate representation in .

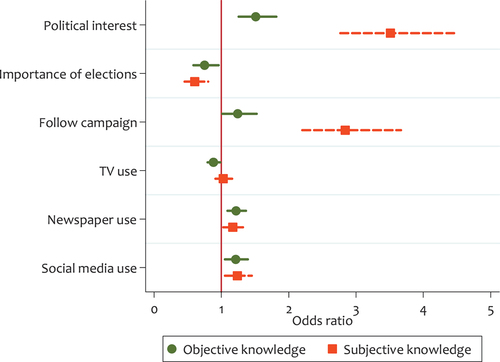

We ran two different ordinal logistic regression analyses (Appendix 2): one without and one with the controls. Starting with the model without control variables, depicts the effects of the six independent variables on both objective and subjective political knowledge. There is partial empirical support for H1, in that the regression coefficients indicate that the surveyed first-time voters with high political interest are 1.5 times more likely to have objective political knowledge compared to those respondents with no political interest. The effect is also positive but considerably stronger for subjective knowledge as first-time voters with high political interest are 3.5 times more likely to perceive the existence of political knowledge. While both effects are positive, this result goes against our expectation that interest boosts objective knowledge to a higher rate that subjective knowledge. One possible explanation for this result is that respondents may put an equivalence sign between interest and knowledge. In other words, if they have an interest in a political matter then they also consider that they have knowledge about it. This can lead to a mild learning curve, which translates into low factual knowledge.

Figure 2. The effects on objective and subjective knowledge.

The empirical evidence for H3 tells a similar story. Regularly following the campaign increases the objective knowledge (OR = 1.24) of those first-time voters who do so. The campaign has a much stronger effect (OR = 2.84) on the perception of political knowledge. Consequently, while following the campaign contributes to both types of knowledge, it increases the subjective knowledge more, contrary to our hypothesis. One possible explanation lies in the content of the campaign for the 2019 Romanian presidential elections. These took place using a two-round system, with the top two candidates from the first round moving into the second round of voting. There were 14 presidential candidates, of whom only three stood a chance of getting into the second round. The campaign of these top three candidates was marked by attacks and criticisms to a larger extent than policy issues or programmatic politics. The incumbent president and the recently dismissed prime minister, who had been in a process political of co-habitation for more than 18 months,Footnote2 used negative rhetoric against each other. The country’s president also refused to have a televised debate with the former prime-minister before the second round. The third candidate, the leader of a party that was formed before the most recent parliamentary elections, also failed to provide an informative campaign and often limited himself to attacking his opponents. Consistent with the arguments presented in the theory section, the negativity of the Romanian presidential campaign enhanced the perception of political knowledge without boosting factual knowledge much.

The evidence generated for H2 goes against the theoretical expectation. The first-time voters who answered our survey and who considered the 2019 presidential elections as being very important had lower levels of both objective and subjective knowledge. One possible explanation for this result may be that citizens with a broad understanding of the Romanian political system do not attach much importance to the presidential elections. The country has a semi-presidential system in which the president has relatively limited formal powers (Elgie and Moestrup Citation2008). The situation was different between 2004 and 2014, when the president (Traian Băsescu) used several informal powers to interfere with domestic politics in general and executive actions in particular (Raunio and Sedelius Citation2020). Since 2014, President Klaus Iohannis has acted more within formal parameters in office, and this may have lowered the political stakes of the 2019 presidential elections. In this context, the surveyed first-time voters who attach importance to these elections may be disconnected from the political realities of the country.

The evidence nuances the theoretical expectations that we formulated about the use of various sources of information. There is partial empirical support for H5 and H6: that the use both of newspapers – online and offline – and social media increases both types of knowledge. In contrast to our hypotheses, these effects are similar. On average, a Romanian first-time voter included in our study who uses these two sources of information on a regular basis is 1.2 times more likely to know more and to perceive that they have higher knowledge about politics compared to those who do not use them at all. This result is consistent with earlier findings that indicate the importance of these sources of information in augmenting individuals’ political knowledge (G. Anspach, Jennings, and Arceneaux Citation2019; Gil de Zúñiga, Weeks, and Ardèvol‐Abreu Citation2017; G. Lee and Cappella Citation2001). In the case of Romanian first-time voters who answered the survey, no difference could be observed between the effect of traditional print media (newspapers) and that of social media on political knowledge. This similarity is especially important in the context of the higher use of social media for information purposes (as compared to newspapers) as indicated in Appendix 1.

The use of TV for information purposes (H4) has a negative impact on objective knowledge and no effect on subjective knowledge. The surveyed first-time voters who use visual media on a daily basis for information purposes have lower factual knowledge than the respondents who do not use it at all. One explanation for this result is the partisan bias of the media in Romania. A large number of media outlets are linked with political parties, which undermines independent and neutral journalism (Coman and Gross Citation2012). Often, media owners pursue their own financial interests and establish strong and usually long-lasting ties with like-minded political actors. The relatively high level of electoral volatility in Romania rests on the low level of partisanship and ideological consistency within the population (Gherghina Citation2014). Voters are open to change, and the media exploit this to provide their services to different politicians and parties. As such, the visual media often serves for propaganda purposes and sometimes is attached to a political party. For example, the Conservative Party has never gained parliamentary seats on its own but only due to an electoral alliance with the Social Democrats. The main reason why the Social Democrats formed these alliances was because the founder of the Conservatives owned a TV station. In the 2012 legislative elections, a business-firm party emerged around the owner of a small TV station and came third in parliament (Gherghina and Soare Citation2017). All these features indicate that the visual media has a limited role for information in Romania, instead often fulfilling other functions.

The statistical models with controls (Model 2 in Appendix 2) do not change the strength and significance of the effects discussed for the independent variables. The fit of the model is also similar, although there are fewer cases due to missing values on the left-right self-placement. The controls have a positive effect on both objective and subjective knowledge among the surveyed first-time voters, but these effects are neither strong nor statistically significant. The respondents who position themselves more to the right of the political spectrum can be seen to have slightly higher levels of political knowledge and to perceive their knowledge as higher. One possible explanation for the limited effect is that differences in knowledge may appear between moderate and radical voters rather than between those on the left and right. One explanation for the small effect of political participation on objective and subjective knowledge is that many of the surveyed first-time voters were passive (see Appendix 1).

Conclusions

This article has aimed to explain which factors influenced the objective and subjective political knowledge of first-time voters in the 2019 presidential elections in Romania. We used individual-level data from a survey conducted on a maximum variation sample in the aftermath of these elections. Our main argument was that motivation, ability, and opportunity are likely to have divergent effects. The empirical evidence only partially supports our theoretical expectations, but it does reveals= a rich picture with several relevant details. One of these is that many respondents display high levels of objective and subjective knowledge – but the two are not highly correlated. This means that the surveyed first-time voters who know a lot about the Romanian political system underestimate their knowledge, while those who know somewhat less have a tendency to overestimate what they know. A second observation is that objective and subjective knowledge are driven to a large extent in the same direction by the independent variables of this study. There is a positive impact on both from higher political interest, campaign following, and the use of newspapers and social media to gather political information. There is a negative effect of the importance attached by citizens to these specific elections. The only exception to this rule is the use of TV, which lowers objective knowledge and has no effect on subjective knowledge.

Third, with the exception of the use of newspapers, the effects are consistently stronger for subjective knowledge. This is also reflected in the fit of the statistical models in the analysis. Another relevant detail, which directly addresses the goal of this article, is that knowledge among the first-time voters covered by our analysis is enhanced by a combination of motivation (political interest), ability (attention paid to the campaign), and opportunity (using the available information). These are ranked in order of their importance for the effects observed in our analysis. Finally, our findings illustrate that the use of different sources of information has a different impact on political knowledge. Although young people extensively use social media for information purposes, as is also confirmed by the distribution described in Appendix 1, that source has a similar effect with the regular reading of online or offline newspapers. Newspapers are the least used source of information, and our result indicates that their benefits in terms of producing knowledge are underrated by many. The use of TV does not produce consistent effects, and it must be noted that the objective knowledge is lower among heavy TV users.

The implications of this analysis reach beyond the single-case study investigated here. At a theoretical level, our study illustrates that the causes of objective and subjective knowledge are often similar. This article therefore nuances and complements existing theories that differentiate between the mechanisms that lead to the two types of political knowledge. We propose an analytical framework which is not context sensitive, that includes specific elements of motivation, ability, and opportunity. The findings indicate that most of the variables included in the framework shape the factual knowledge of first-time voters and their positive perception about how much they know, in the same direction and often with comparable intensity. At an empirical level, our analysis contributes to building a deeper understanding of objective and subjective knowledge among first-time voters, who are at the beginning of their contact with politics. In addition, this is one of the first studies comparing the drivers of the two types of political knowledge. Some of the findings are counter intuitive. For example, motivation and ability are strong predictors for objective knowledge, but not always in the direction in which we may expect. Another example is that the availability of information has a differentiated impact on knowledge depending on the source of that information. In this particular case, the extensive use of social media for information purposes – which is highly popular among young people – is less effective than many would expect.

Despite the originality of our study, one limitation is the use of a non-representative sample that confines the results to the respondents. Further research can address this by using similar questions via a probabilistic survey that can cover both voters and non-voters from different age cohorts. Such an approach would allow the generalization of findings and may reveal the robustness of the observations presented here. At the same time, our analysis emphasized the existence of statistical relationships. Further qualitative analysis could explain the mechanisms through which motivation contributes to both objective and subjective political knowledge. The identification of causal linkages and explanations can take the form of in-depth case studies or cross-country analyses with the help of qualitative data. Focus groups or semi-structured interviews could provide the rich data required to generate meaningful insights into how objective and subjective knowledge is formed. Such an approach would allow future researchers to check for the importance of some variables such as the importance of emotions, which could not be included in the present survey, in cognitive development. The inclusion of emotions in addition to rationality would provide a more comprehensive picture of the process and could investigate the effects that the two different types of knowledge can have on political participation.

Disclosure statements

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sergiu Gherghina

Sergiu Gherghina is an Associate Professor in Comparative Politics at the Department of Politics, University of Glasgow. His research interests lie in party politics, legislative and voting behavior, democratization, and the use of direct democracy.

Claudiu Marian

Claudiu Marian is an Associate Professor at the Department of International Studies and Contemporary Politics, Babes-Bolyai University Cluj. His research interests are political parties, political marketing and electoral sociology.

Notes

1. Apart from the controls included in the analysis, we also tested the effect of other variables that could have influenced voters’ objective or subjective knowledge. Some of these variables are urban/rural residence, living with parents, and gender. There is no empirical support for any of these variables. Consequently, we do not report the findings here, in order to keep the statistical models parsimonious.

2. Co-habitation in Romania has a history marked by conflicts between the country’s president and prime-minister, who share the executive power. For details of previous conflicts, see Gherghina and Mișcoiu (Citation2013) and Raunio and Sedelius (Raunio and Sedelius Citation2020).

References

- Aalberg, T., J. Strömbäck, and C. H. de Vreese. 2012. “The Framing of Politics as Strategy and Game: A Review of Concepts, Operationalizations and Key Findings.” Journalism 13 (2): 162–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911427799.

- Aertsens, J., K. Mondelaers, W. Verbeke, J. Buysse, and G. van Huylenbroeck. 2011. “The Influence of Subjective and Objective Knowledge on Attitude, Motivations and Consumption of Organic Food.” British Food Journal 113 (11): 1353–1378. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070701111179988.

- Allcott, H., and M. Gentzkow. 2017. “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31 (2): 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211.

- Anderson, W. 1964. Man’s Quest for Political Knowledge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Anspach, N. M. 2017. “The New Personal Influence: How Our Facebook Friends Influence the News We Read.” Political Communication 34 (4): 590–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1316329.

- Anspach, N. M., J. T. Jennings, and K. Arceneaux. 2019. “A Little Bit of Knowledge: Facebook’s News Feed and Self-Perceptions of Knowledge.” Research & Politics 6 (1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018816189.

- Arthur, L., and T. S. Philpot. 2005. “Views from Inside the Net: How Websites Affect Young Adults’ Political Interest.” The Journal of Politics 67 (4): 1122–1142.

- Banwart, M. C. 2007. “Gender and Young Voters in 2004: The Influence of Perceived Knowledge and Interest.” American Behavioral Scientist 50 (9): 1152–1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764207299362.

- Boulianne, S., K. Koc-Michalska, and B. Bimber. 2020. “Right-Wing Populism, Social Media and Echo Chambers in Western Democracies.” New Media & Society 22 (4): 683–699. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819893983.

- Carlson, J. P., L. H. Vincent, D. M. Hardesty, and W. O. Bearden. 2009. “Objective and Subjective Knowledge Relationships: A Quantitative Analysis of Consumer Research Findings.” Journal of Consumer Research 35 (5): 864–876. https://doi.org/10.1086/593688.

- Carpini, D., X. Michael, and S. Keeter. 1991. “Stability and Change in the U.S. Public’s Knowledge of Politics.” Public Opinion Quarterly 55 (4): 583. https://doi.org/10.1086/269283.

- Christensen, H. 2018. “Knowing and Distrusting: How Political Trust and Knowledge Shape Direct-Democratic Participation.” European Societies 20 (4): 572–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2017.1402124.

- Coman, I., and P. Gross. 2012. “Uncommonly Common or Truly Exceptional? An Alternative to the Political System–Based Explanation of the Romanian Mass Media.” The International Journal of Press/politics 17 (4): 457–479. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161212450562.

- Dostie-Goulet, E. 2009. “Social Networks and the Development of Political Interest.” Journal of Youth Studies 12 (4): 405–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260902866512.

- Dubois, E., and G. Blank. 2018. “The Echo Chamber is Overstated: The Moderating Effect of Political Interest and Diverse Media.” Information, Communication & Society 21 (5): 729–745. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1428656.

- Ekström, M., and A. Shehata. 2018. “Social Media, Porous Boundaries, and the Development of Online Political Engagement Among Young Citizens.” New Media and Society 20 (2): 740–759. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816670325.

- Elgie, R., and S. Moestrup, eds. 2008. Semi-Presidentialism in Central and Eastern Europe. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Entman, R. M. 1993. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x.

- Entman, R. M., J. Matthes, and L. Pellicano. 2009. “Nature, Sources and Effects of News Framing.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by K. Wahl-Jorgensen and T. Hanitzsch, 175–190, London, New York: Routledge.

- Feldman, L. 2016. “Effects of TV and Cable News Viewing on Climate Change Opinion, Knowledge, and Behavior.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.367.

- Flaxman, S., S. Goel, and J. M. Rao. 2016. “Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Online News Consumption.” Public Opinion Quarterly 80 (S1): 298–320. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw006.

- Gherghina, S. 2014. Party Organization and Electoral Volatility in Central and Eastern Europe: Enhancing Voter Loyalty. London: Routledge.

- Gherghina, S., and S. Mișcoiu. 2013. “The Failure of Cohabitation: Explaining the 2007 and 2012 Institutional Crises in Romania.” East European Politics & Societies 27 (4): 668–684. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325413485621.

- Gherghina, S., and S. Soare. 2017. “From TV to Parliament: The Successful Birth and Progressive Death of a Personal Party the Case of the People’s Party Dan Diaconescu.” Czech Journal of Political Science 24 (2): 201–220. https://doi.org/10.5817/PC2017-2-201.

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., B. Weeks, and A. Ardèvol‐Abreu. 2017. “Effects of the News-Finds-Me Perception in Communication: Social Media Use Implications for News Seeking and Learning About Politics.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 22 (3): 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12185.

- Goldberg, A. C., and C. Ischen. 2020. “Be There or Be Square – the Impact of Participation and Performance in the 2017 Dutch TV Debates and Its Coverage on Voting Behaviour.” Electoral Studies 66:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102171.

- Groza, M. D., D. A. Locander, and C. H. Howlett. 2016. “Linking Thinking Styles to Sales Performance: The Importance of Creativity and Subjective Knowledge.” Journal of Business Research 69 (10): 4185–4193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.03.006.

- Guo, L., S. Chao, and H. Lee. 2019. “Effects of Issue Involvement, News Attention, Perceived Knowledge, and Perceived Influence of Anti-Corruption News on Chinese Students ’ Political Participation.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 96 (2): 452–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699018790945.

- Hollander, B. A. 1995. “The New News and the 1992 Presidential Campaign: Perceived Vs. Actual Political Knowledge.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 72 (4): 786–798. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909507200403.

- Kahn, K. F., and P. J. Kenney. 1999. “Do Negative Campaign Mobilize of Suppress Turnout? Clarifying the Relationship Between Negativity and Participation.” The American Political Science Review 93 (4): 877–889. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586118.

- Lau, R. R., and D. P. Redlawsk. 2006. How Voters Decide. Information Processing During Election Campaigns. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lee, G., and J. N. Cappella. 2001. “The Effects of Political Talk Radio on Political Attitude Formation: Exposure versus Knowledge.” Political Communication 18 (4): 369–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600152647092.

- Lee, S., and M. Xenos. 2019. “Social Distraction? Social Media Use and Political Knowledge in Two U.S. Presidential Elections.” Computers in Human Behavior 90 (1): 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.006.

- Lehmann, J. 2005. Social Theory as Politics in Knowledge. Stamford: JAI Press.

- Lilleker, D. G. 2014. Political Communication and Cognition. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lipsitz, K., and J. G. Geer. 2017. “Rethinking the Concept of Negativity: An Empirical Approach.” Political Research Quarterly 70 (3): 577–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912917706547.

- Lipsitz, K., C. Trost, M. Grossmann, and J. Sides. 2005. “What Voters Want from Political Campaign Communication.” Political Communication 22 (3): 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600591006609.

- Liu, Y., S. Yanjie, X. Guoqing, and R. C. K. Chan. 2007. “Two Dissociable Aspects of Feeling-Of-Knowing: Knowing That You Know and Knowing That You Do Not Know.” Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 60 (5): 672–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470210601184039.

- Lupia, A. 1994. “Shortcuts versus Encyclopedias: Information and Voting Behavior in California Insurance Reform Elections.” American Political Science Review 88 (1): 63–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/2944882.

- Mondak, J. J. 1995. “Newspapers and Political Awareness.” American Journal of Political Science 39 (2): 513. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111623.

- Nadeau, R., N. Nevitte, E. Gidengil, and A. Blais. 2008. “Election Campaigns as Information Campaigns: Who Learns What and Does It Matter?” Political Communication 25 (3): 229–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600802197269.

- Nai, A. 2020. “Going Negative, Worldwide: Towards a General Understanding of Determinants and Targets of Negative Campaigning.” Government and Opposition 55 (3): 430–455. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2018.32.

- Ortoleva, P., and E. Snowberg. 2015. “Overconfidence in Political Behavior.” American Economic Review 105 (2): 504–535. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20130921.

- Park, C.-Y. 2001. “Research Notes News Media Exposure and Self-Perceived.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 13 (4): 419–425. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/13.4.419.

- Prior, M. 2005. “News Vs. Entertainment: How Increasing Media Choice Widens Gaps in Political Knowledge and Turnout.” American Journal of Political Science 49 (3): 577–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00143.x.

- Raunio, T., and T. Sedelius. 2020. “Presidents and Cabinets: Coordinating Executive Leadership in Premier-Presidential Regimes.” Political Studies Review 18 (1): 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929919862227.

- Redlawsk, D. P. 2004. “What Voters Do: Information Search During Election Campaigns.” Political Psychology 25 (4): 595–610. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00389.x.

- Rhodes, S. C. 2022. “Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Fake News: How Social Media Conditions Individuals to Be Less Critical of Political Misinformation.” Political Communication 39 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2021.1910887.

- Schäfer, S. 2020. “Illusion of Knowledge Through Facebook News? Effects of Snack News in a News Feed on Perceived Knowledge, Attitude Strength, and Willingness for Discussions.” Computers in Human Behavior 103:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.031.

- Segvic, I. 2005. “The Framing of Politics: A Content Analysis of Three Croatian Newspapers.” Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands) 67 (5): 469–488. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016549205056054.

- Sullivan, P. J., M. Ragogna, and L. Dithurbide. 2019. “An Investigation into the Dunning–Kruger Effect in Sport Coaching.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 17 (6): 591–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2018.1444079.

- Sunstein, C. R. 2001. Echo Chambers: Gore V. Bush Impeachment, and Beyond. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Wagner, A., and W. Elena. 2017. “TV Debates in Media Contexts: How and When Do TV Debates Have an Effect on Learning Processes?” In Voters and Voting in Context: Multiple Contexts and the Heterogeneous German Electorate, edited by H. Schoen, S. Rossteutscher, R. Schmitt-Beck, B. Wessels, and C. Wolf, 71–89. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Weber, M., and C. Koehler. 2017. “Illusions of Knowledge: Media Exposure and Citizens’ Perceived Political Competence.” International Journal of Communication 11: 2387–2410. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5915.