ABSTRACT

What occurs when a purchase is labelled as a gift by the supplier? This paper aims to unveil the dynamics of power relations enveloping gift exchange and monetary transactions in modern economies. It examines the public media discourse around the presentation and reception of surgical face masks from The People’s Republic of China, described as a paid-for gift, during the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Using Foucauldian Discourse Analysis of dominant online media in the Czech Republic, the article illustrates the public’s understanding of the implicit meanings and commitments associated with a gift. It also explores the enduring sensitivity to economic relationships formed through gift exchange between two modern societies. The interplay of the spirit of the gift, mask diplomacy, pastoral care, and the varying acceptance or resistance to these concepts are central to our analysis. Furthermore, the paper delves into the strategies used by recipients to resist such influences, both internationally and in personal resistance against domestic governance.

Introduction

Even though Western economies do not explicitly accept gifts as a valid form of payment, the notions of power and the reciprocal relationship between the gift-giver and gift-receiver are still visibly understood. This paper explores the topic of gift-giving at the level of national importance around one particular event: the reception of the supposed gift from the People’s Republic of China during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. It has already been established that the People’s Republic of China (China) is the country of origin of the disease (WHO, World Health Organization Citation2020). Although official statistics of infected and deceased people in China are not widely accepted as accurate (Oliver Citation2021), and there are good reasons to believe the number of cases there has been heavily understated (Editorial Board Citation2021), the country certainly experienced the most severe hit during the first months of the year 2020. By the time the disease had spread to the first European countries, China had claimed to be already back on its feet and offered surgical masks to help combat the disease outside its borders. In fact, their first shipment to Italy in March 2020 received worldwide coverage (Sousa-Pinto et al. Citation2020). Some experts commented on the motives for this gesture and speculated why China exported masks when its people experienced an acute shortage of this item. Nonetheless, this medical help earned the Chinese government some extra credit from their people. Chinese people claimed they perceived their country as big-hearted (Zhao Citation2021).

At the same time, China offered a helping hand to Europe and decided to choose the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Serbia, Italy, and a few other European countries, to supply surgical masks (Védeilhé et al. Citation2020). The masks – scarce goods at the time – were offered to the governments for a set price, duly paid. At the same time, the promo information, as well as the rhetoric of the Chinese government, labelled this exchange “a gift.” Such was also the information that each box of surgical masks, shipped to the Czech Republic, carried upon itself. As it would turn out later, China applied the same tactic to Argentina, Italy, and other selected countries, claiming that the nations received a gift or help from the People’s Republic of China, regardless of the fact that each government paid for the mask supply (Garrison Citation2020).

Such behaviour on the part of the Chinese government has been identified by international scholars as “mask diplomacy” and has been received with varying levels of resistance by national governments and the international community (Kowalski Citation2021; Verma Citation2020). Be it a friendly gift, opportunistic business, or an elaborate power move, the event provoked a wave of resentment in the countries in question. To illustrate the situation, the particular case of public media discourse in the Czech Republic is presented below, which shows well the ambiguity in the public attitude towards the Chinese help. This paper takes the perspective of Maussian gift-giving (Mauss Citation1924) and Foucauldian power structures (Foucault Citation1975) to look behind the motives for offering scarce goods to foreign nations and to explore the reactions of the countries in question.

Theoretical background

Blind bargain leads to blind love: how economic acts build a relationship

Each economic relationship involves a specific range of obligations that are open to (re)definition at the convenience of the two respective sides participating in the relationship. However, tension may emerge as a by-product of these undefined arrangements, possibly escalating to conflict. In this paper, we use the lens of economic anthropology (Hennink, Hutter, and Bailey Citation2011; Wilk Citation1996) and argue that the ambiguous economic issue – namely the gift-purchase and the subsequent ambiguous reception of surgical masks from China, can be viewed as an event with subtle layers of forming power relations between the two actors. Mutual collaboration – such as cooperation in times of crisis – leads to increased mutual dependency but not necessarily to increased mutual understanding and solidarity (Sleeboom-Faulkner Citation2014, 334). Subsequently, the relations are uniquely developed by the social and cultural notions in both countries, and their mutual dialogue negotiates power arrangements.

A century ago, Marcel Mauss (Citation1924) managed to capture the intriguing topic of gift-giving practices, triggering a widespread fascination with gifts in foreign and domestic cultural environments. In this sense, Mauss viewed gift-giving as a total social fact, a prototypical contract (van Baal Citation1975), and an embodiment of the relationship between the creditor and the debtor. A gift is an invitation to partnership, and to refuse it means to reject alliance or declare war. Gifts result in binding relationships, in a moral contract. Gift-giving networks operate on the notions of mutual creditors and debtors, and this network is perpetuated not only by the prestige and material value of the gifts, but also by the relationships that are maintained mainly by obligations to give, receive, and reciprocate gifts. Later, Lévi-Strauss (Citation1955) further developed the idea of forming relationships via gifts, claiming that gifts are instruments of realities of order. He theorized gifts as agents of influence, power, hierarchy, and emotion, which are used to form and to secure alliances or to articulate rivalry. As it will be shown later in the analysis section, there is an interesting dissonance between accepting the surgical masks as a plain commodity, while at the same time there is a strong resistance to accept the same shipment as a gift. From this point of view, the idea of accepting and declining an invitation to partnership and becoming a debtor is particularly strong.

As noted above, any gift implies consequential power relations for both the giver and the receiver and the subsequent struggle of power and resistance against normativity (Foucault Citation1975). The discussed topic, in particular, calls for a consideration of questions regarding governmental decisions, the peculiarities of biopower, pastoral care, and forms of resistance (Foucault Citation1976, Citation1978). To set these concepts into the course of recent events, Colombo (Citation2020) discovered how two governmentalities had monopolized the bio-economic debate in Italy during the first wave of the COVID-19. He reports that the voice of homo oeconomicus vividly exchanged opinions with the voice in defence of biological life, but both forgot to highlight the social perspective in the debate. Expert scientific as well as civil discourse voices are missing. This is particularly severe in Central and Eastern Europe, where civil society has been decimated and uprooted during previous regimes (Marzec and Neubacher Citation2020). In this sense, Colombo (Citation2020) argues, the public has only a limited choice between defending life or defending economic interests.

Furthermore, Foucault identifies the concept of biopower that denotes the techniques that governments use to gain and maintain control over the bodies of their population (1976). The idea of biopower will shed light on the issues underlying our topic, wearing masks, controlling the spread of the virus, making people live in hospitals and letting them die at home, restricting public life to make and keep our bodies healthy. All strategic interventions are carried out in the name of life necessity which characteristically entails the specific measures taken to make life or let die. Similarly, exerting power goes hand in hand with disciplinary techniques. In our context, enforcing discipline can be observed in banning people without surgical masks from restaurants and shops, sending military and police to oversee curfews, or imposing financial penalties on people and businesses defying governmental rules.

In addition, Foucault deals with the idea of power centralization (1975). Within our context, we can uncover two layers regarding the surgical masks from China: the central purchase evaluating and choosing goods that will affect many people, and central measures that will protect and restrict the bodies of the entire population. As Foucault argues, centralized activities often provoke reactions. In his later work (1982), he acknowledges the agency that people manifest in forms of subtle resistance. An individual is an object as well as a subject of power simultaneously, and one simultaneously exerts and undergoes power in both positions (Heller Citation1996). Resistance presents itself as a valid option to shift this power relationship and re-establish one’s position in that relationship.

However, resistance against the normative purchase and compliant use of surgical masks could not be disputed openly since the centralized government also exerts disciplinary control over whoever does not obey. Its disciplinary power became even more remarkable when the country announced a state of emergency, in which both legislation and public expenses conform to government decisions only. Under such governmental authorities, people need to seek subtle ways to express disagreement and to oppose centralized decisions, should they wish to avoid punishment. One of the last resorts left for expressing resistance is the public discourse that can be traced in the press. On the following pages, we will explore how gift-related discourse shaped and determined practices related to the shared ideas about power and influence between the Chinese, the Czechs, and their government. Although both nations claim to be capitalist and commodity-based, both sides recorded great controversy when the exchange was labelled as a gift. Therefore, it is crucial to answer essential inquiries about what role (if any) gift exchange played in the event in question, why (if) Czech people refused to view the exchange as a gift, and how (if) gift-giving practices related to the shared ideas about power and influence.

Methodology and sample identification

Dissecting the meaning: what goes beyond words

Our research aims to provide insight into the underlying constructions in the public discourse revolving around the shipment and reception of Chinese surgical masks during the first wave of COVID-19 in the Czech Republic. The method of this inquiry employs a qualitative approach, which does not strive to find an exact conclusion but instead aims to understand how meanings are attributed and interpreted (Hennink, Hutter, and Bailey Citation2011). We have used Foucauldian Discourse Analysis (FDA) to examine how power relations were built and responded to in public discourse regarding the reception of surgical masks from China, labelled as a gift for the people of the Czech Republic. Discourse analysis focuses on language and its relation to the external world, uncovering the interplay between discourse, power, and human subjectivity (Antaki Citation2004; Arribas-Ayllion and Walkerdine Citation2008; Willig Citation2008). This includes identifying key agents and interpreting their communication through the lens of social theories. Recognizing discourse as a body of organized statements, the FDA further analyzes how those statements are produced, what is said and what is left out, and how social space affects the production of statements (Kendall and Wickham Citation1999). Thus, the analysis comprises five steps that reflect discursive construction, identification of discourses, positioning of stakeholders, social practice, and the subjective experience of participants. This method enabled us to identify interpretative repertoires constructed on social and cultural levels, discourses that flow around disguised as common sense, and ideologies that underlie their meanings. Here, discourse denotes specific communication of worldviews and understanding of the world (Jørgensen and Phillips Citation2002). Language is perceived as a subjective tool, which, however, constructs social reality. Thus, the FDA uses language as a means of understanding how this construction of worlds manifests in everyday communication and power relations. Looking from a meta-perspective, we are suddenly able to uncover a representation of the world that is negotiated in social interaction and controlled by specific rules (Vasat Citation2009) that might not be apparent otherwise. As such, FDA helps to understand the relationship between gift/giving and a time of crisis, as well as what people have thought and felt and what actions that inspired.

Defining the field and data collection

The scope of the field was defined by the situation rather than time. Situational boundaries naturally formed around the event of the shipment, reception, and use of surgical masks from China into the Czech Republic. As a result, the temporal boundaries of the field are limited by the event itself, ranging from March 2020 to the date of analysis in March 2021, peaking in the earliest months of late spring 2020. Although we can expect that the highest peak of interest from media, public, and scholars was provoked by the reception in March and fresh personal experiences with the masks in April, articles and posts still covered the topic from different perspectives months later.

Within the situational and temporal boundaries, our scope of the field was further defined by the means of communication. We decided to focus exclusively on the online environment due to the increased use of online communication in times of mandatory social isolation. In fact, social media consumption rose by 72% during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic (Wold Citation2020) and online news recorded an increase of 14% (Newman Citation2020.). Thus, analysing online content seems a logical move to undertake, as the majority of public discourse was temporarily limited to that environment.

In the online environment, we chose to focus on two major sources of public discourse in audio-visual content: online news servers and popularization articles by academic researchers. First, let us investigate the choice and reasoning behind online news services. This category encompasses official press released by professional writers, that is, editors who make a living from writing about recent developments in politics, economy, and society, reporting on significant events domestically and abroad. This is where the mainstream opinion is shaped and refined. We chose to analyse posts on three platforms with the highest number of readers: Seznam Zprávy, Novinky, and Aktualne (Mediaguru Citation2021). Within the situational, temporal, and spatial boundaries, we proceeded further to demarcate boundaries of the content. To filter out relevant articles, we searched for keywords rouška/mask and Čína/China in the first step, gradually adding dar/gift and pomoc/help in the next steps. From a total of 65 articles found on the three respective platforms, we filtered out a third before reaching theoretical saturation.

As a secondary component of the analysis, we added articles posted on academic blogs designed for (informed) readers of the public. We searched for articles published by academic thinkers with the intention to reach a wider public. We focused on blogs that include contributions from academics in Chinese studies, political science, social science, and economic studies from three universities in the Czech Republic: Charles University in Prague, Masaryk University in Brno, and Palacky University in Olomouc. It is important to note that even though almost every school has its own blog, the space is used predominantly for posting news, and only a few schools cultivate blogs for public readers. We found three sources that aim to shape public opinion in the respective fields: Sinopsis, a public blog co-organized by the School of Sinology (Charles University), student media platform UPress (Palacky University), and e-zine Dalny Vychod published by the Department of Asian Studies (Palacky University). Only three articles were relevant for this study out of all the blog production of all three universities. Unfortunately, neither UPress nor Dalny Vychod reacted to recent developments of COVID-19 in China and are therefore not useful for our purposes.

As for filtering the material, we used relevancy and information saturation when reducing the entries for analysis by two thirds. For example, entries related to the COVID-19 pandemic but having no connection to face masks from China were ruled out. As a result, a total of 21 articles (7 articles for each medium) and one academic blog post were collected and examined using FDA for the purpose of this paper. Academic blog posts did not go through this reduction procedure since we had only one article to analyse.

All material was read in the first round to provide a sense of the topic and information richness. Then, articles were subjected to the FDA procedure as described by Willig (Citation2008) and Siena (Citation2023):

Identification of discursive constructions: In the initial stage, we identified how gifts and masks were referred to in each of the articles. Subsequently, the construction of discourse (both explicit and implicit) was tracked down. For instance, Chinese intervention was identified as an economic ability to create a surplus of masks at the time of crisis. Other discursive constructions included mask diplomacy and help. Much space was given to combating circulating disinformation, for example regarding the effects and possibilities of wearing face masks or playing down the effects of the pandemic.

Identification of particular discourses framing more general constructions, the grand narratives: At this point, discourses from stage a) were clustered into broader categories. Through these, the trajectories and genesis of general ideas become traceable and obvious. For example, several articles mentioned disinformation as a disease comparable in possible damage to COVID-19 or a gift was referred to as an instrument of propaganda and exercising power.

Analysis of action orientation: Various grand narratives have different functions and carry out different implications for action. At this stage, we concentrated on establishing the link between the narrative and its potential agency, such as reporting how European legislation should reflect circulating disinformation, or how people should take power into their own hands and stop relying on the government altogether.

Identification of position repertoire, determination of practice: Discourses identified are performed by social actors (both individuals and institutions), who carry out certain roles and symbolic values and have at their disposal appropriate practices. At this stage, we identified the social actors and their roles, as well as their practices, that are the direct outcomes of the clustered discourses. In our example, doctors and government officials were the most prominent actors who provoke or suggest action that the media reproduce.

Capturing subjectivity and individual experience: At this last stage of the analysis, the subjectivity of social actors present in the discourses (their feelings, emotions, personal statements) was looked into and positioned within the analysis. However, little subjectivity was found. This is in line with our expectation for the ethos of established media channels: journalists strive for reporting objectively.

Results and findings

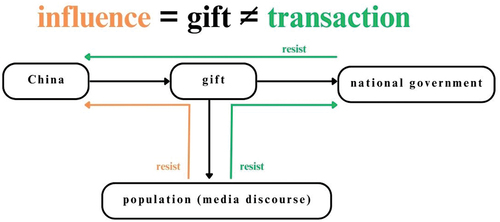

Our findings suggest that the media debate over face masks from China was clustered around three major discourses: the nature of the gift, resistance towards an external pastor, and resistance towards an insufficient internal pastor. Initially, the nature of the gift was disputed by the media. This sparked questions directed at the internal pastor (the government) and provoked the public to demarcate the boundaries between a purchase and a gift. In the second phase, resistance against the external pastor (China) was openly declared. This was followed by the third phase, where the resistance expanded to also include the internal pastor. The dynamics of these relationships are illustrated in .

The results of the analysis reveal the interplay of two modes of resistance: the first being the resistance to labelling the reception of masks as a “gift” and thus resisting all the relationships that emerge from such a transaction. China was identified as a colonizer, disguised as an external pastor. The resistance directed towards an external stimulus, such as the inscription on the boxes or the proclamations of Chinese diplomacy, was a response to the suggested subservient role emerging through Chinese mask diplomacy.

The other branch of resistance was against the insufficient pastoral care of the national state, where the shipment of masks from China became a symbolic manifestation of this insufficiency. By portraying the event as a dishonest business or a fraud, we can observe a strong critique of domestic governmental pastoral power, followed by a refusal to oblige, manifesting in various manners. The topic of Chinese face masks provoked a wave of resistance against the external pastor, but also against the national one, where the dispute over the nature of a gift provided a magnifying glass to assess the positions, despite the fact that mainly economic reasons (as opposed to ideological and value-related) were raised by the public media discourse. The following text dissects more nuanced features found in the analysis, while presenting excerpts, connections, and detailed interpretations.

Nature of a gift

In the time of crisis during the pandemic, when masks were a scarce commodity not only in the Czech Republic but also across the world, China’s economy was the fastest to produce a surplus, which could be allocated elsewhere. There were not enough masks produced by China to satisfy all the sudden world demand. The central government of China selected a few countries across the globe, made contracts with them and sold the masks to them for a settled price. The Czech Republic was one. The Chinese diplomacy labelled this transaction a gift and boxes with face masks were decorated with banners, stating lasting friendship between the Czech Republic and China. The whole event received a large media response.

China sends help against Corona virus to Europe. Czechia buys it. (SZ7)

Aerial bridge from China comes to an end. Czechia bought material for 4 billion Crowns. (N7)

Despite Despite the fact that China’s action was acknowledged in a positive sense, since this appreciation was labelled ´a help´, the impact of the help was relativized by ´being paid for´ and soon also by its questionable quality.

The office of the minister Adam Vojtěch found out that the Chinese respirators, which cost about 230 million Crowns are not of efficient quality. (SZ2)

Given the world-crisis situation, despite its questionable quality, having face-masks at disposal was an asset. At the same time, the media debate understood the decision to sell masks to the Czech Republic was not to illustrate the altruistic nature of Chinese politics but to single out a selected group of strategic indebted allies.

’Noone else could deliver such a huge amount (of face masks). Of course, China uses the advantage, as it shows it can handle a crisis that Western countries led by the USA cannot manage,’ shared with server Aktualne sinologist Stanislav Mysicka from The University of Hradec Králové. (A1)

The purpose and the nature of transaction shifted soon from help to underlining influence and power, which is connected to being a giver, while creating a feeling of commitment on the side of the receiver. Even though the Czech market economy is based upon the Western model of monetary exchange, sensitivity to the relationships formed by giving and receiving gifts survives within the nation. This nature of the gift can be summarized and illustrated upon three following qualities. First of all, as part of this understanding, gifts are free of monetary transactions, which ruled out the Chinese face masks to be perceived as such:

Face masks from China are not a gift but a transaction, said the mayor Hřib and labeled Prague lockdown a nonsense. (SZ7)

Second, for an object to be considered a gift, it ought to be of good quality, not a waste:

The most expensive face mask in the world, or a faulty respirator? . This crazy story is excusable only by the fact that we were at the state of war. That we were desperately seeking respirators and went on our knees to beg for them. (SZ3)

Third, gifts create mutual dependence and obligation, where the giver holds a superior position, until the gift is returned. The media debate showed great resistance towards this relationship.

Instead of being thankful, let us pose a question of how to avoid having to use premium relationships with the Chinese Communist Party and its lobbyists in the future. (Lomova Citation2020)

The Czech society was not the only one refusing to grant immense gratitude for their mask purchase. Czech media reported similar cases around the world, especially in South America and Italy and worries about the Chinese influence were loudly voiced.

China as a new colonizer. China hands out “gifts” in South America, exchanges masks for influence … Now China is the new colonist, just as the ones before them. They destroy the harmony of our country. (A1)

China the helper became China the threat through mingling the categories of help, gift and purchase. As noted above, only one academic blog made its way into the set of analysed data. This, however, does not mean that academics had nothing to say upon the matter. Their expertise was called upon and intertwined into the main popular media, using their statements as ´proofs´ or ´explanation´ of other parts of the text, typically written by journalists, trained in communication rather than in international politics, sinology or immunology. The researcher´s name, opinions, and photographs emerge throughout the article, to give the text additional value:

Mysicka states that healthcare is the following (industry) sector that China will target. (A1)

The analysis shows the Czech nation was well aware of the kind of relationship they would receive along with the gift and tried to resist it in the press. Although the Czech economy is based on the Western model of monetary transactions, the sensitivity to gift and reciprocal exchange on a national level perseveres in the society. One of the prominent themes that emerged surrounded obligations and possible attachment in the future, as suggested by Mauss (Citation1924) and his successors (e.g. van Baal Citation1975). We can observe politicians, media and academics refusing the gift narrative unanimously. At the same time, the gift was depicted as a costly help: an economic transaction that was part of a dishonest business in a state of emergency. Moreover, the media opposed the stream of gratitude that was expected from the Chinese authorities. The most frequent actions of the media were to discredit flawed information, voice disapproval, and search for the guilty party. The actors involved in the gift-giving were painted as profit-oriented companies, although their spokesmen positioned themselves as innocent mediators of the deal.

Resistance towards external pastor

China was the first country to be hit severely by Covid-19. By the time the pandemic spread across Europe, China already had its experience with it, which gave the country seemingly the authority to give advice and help to others. However, this rhetoric was widely questioned.

China labels this help Health Silk Road … Chinese president said: China purposefully supports Italy and has full trust in its victory over the pandemic (N4)

China offers help, but it is really propaganda, experts proclaim. (A6)

China tries to appear as a country that won against the epidemic and is worth following. China tries to persuade the world that they are victims and allowed to give advice. It is important to remember that this is an attempt to rewrite the narrative. China tries to re-narrate the story and convince their own national audience. (A6)

Mask diplomacy, disinformation, propaganda and the new Silk Road are some of the most prominent discursive constructions in the public space. Relating to Jaworsky and Qiaoan (Citation2020) analysis, we can observe battles over the COVID-19 narrative between two competing powers: China and the USA. As soon as the pandemic spread into Europe, the EU joined the battle later on too.

What are the greatest risks of Covid-19? Lies around it, says the EU … Much too often are we mystified with information, how good are Russia and China in conquering pandemics, while some European countries are collapsing. (N1)

The meaning-making processes constructed the war of narratives, where China was a new world colonizer, creating the new Silk Road of healthcare, thus supplying the goods necessary not only for immediate health comfort of European people but also for their future well-being, as it is evident from the following excerpt:

The flagship project of president Xi Jinping strives to convince states in Central and Eastern Europe about the benefits of cooperating with China and connection to the new Silk Road. (A3)

The Silk Road, a powerful symbol of Chinese political, economical, cultural, and spiritual influence upon the regions through which it runs, evoked a powerful allegory with the past, when China exercised strong economic and political influence over Europe. Taking part in the Silk Road was never a matter of course, in the past, as well as during the pandemic, it was considered a privilege, an advantage, a “gift” in a sense. Using this exact symbol by the Chinese president triggered off resistance against the external new world-wide pastor.

As a new colonizer, China is giving out “gifts” in South America … Health help, called mask diplomacy, could be, according to experts, the way through which China tries to strengthen its position in Latin America. (A1)

Experts of the Ministry warn that China was withholding information about COVID-19 and the pandemic and with the help of propaganda it tries to use it to divide the West and gain dominance. (A3)

Attempting to disclose “the true face of China,” Czech media discourse abounded with warnings against malintent and trickery, while reserving China’s role in COVID-19 to PR exercise and referring to the offered help as a disguised business and self-promotion. It reflected the global battle of narratives and tried to counterbalance the Chinese influence. Questions regarding whom to blame and whom to follow became central to the global battle of narratives and will be observed more closely in the final chapter of the analysis. We can observe various tools that are deployed in the battles: disinformation, objects, naming, diplomatic strategies, and media influence. Then, the purpose of these crafted narratives is to influence their own nations as well as foreign audiences. The Czech media responded to these tensions and tried to counterbalance the narrative that puts their nation into an unfavourable position, thus clearly taking an anti-China stance.

We are not your guberniya, the Czech politicians are sending the word back to China … Wang (ambassador) says that doubting principles of a unified China means making 1.4 billion Chinese enemies and that the Chinese government will not tolerate open provocation from the Czech Senate and anti-Chinese parties that are behind it. (SZ5)

The discourse of resistance towards the external pastor was illustrated as a threat to the sovereignty of the country and included discourses of mask diplomacy and oppression. The media actions were oriented to voice disapproval, warn against propaganda, and disgust readers. Some statesmen, local governments, and experts were positioned to warn against the chaos. Positions included diffusing propaganda and declining help. On the other hand, China was depicted as helping but also profiting and colonizing and was positioned as a leader who caught the West unprepared. The media described its actions as selling success to the national public and diffusing propaganda.

Resistance towards insufficient internal pastor

The spread of the pandemic into Europe and the Czech Republic triggered chaos and fear, where both the institutions and the people were caught unprepared, having no precedent of the situation.

One kilometer long queue of doctors. This was the first day of distributing face masks in the city of Olomouc. (N2)

All looked towards the government to provide security and care. It soon became obvious that the situation is different.

Face masks will be available next week, the government promises … “I believe the key workplaces have enough of them and more will be delivered in the days to come,” says the Minister of Health. (N1)

The good pastor ought to provide care and safety. In this particular instance, it failed badly.

While on the 28th January, minister Adam Vojtěch assured the citizens that Czechia has about a million face masks in store, today there are thousands of pieces missing most probably in every health institution across the country. The government went from promises, to vague reassurances and now, one and a half months later it has to acknowledge that safety gadgets are completely missing. (N6)

Not only were the face masks not available. Those which were, came from external sources, from China, a contract for billions of Crowns without competitive tendering. It was possible due to the state of emergency of the Czech state but still arose speculation of corruption. National government overlooked domestic possibilities, which was interpreted as another failure of a good pastor.

While the prime minister Andrej Babiš and the minister of interior Jan Hamáček were receiving the supply from China at the airport, costing billions of Crowns, a Czech producer of top safety clothes and face masks complained that it still awaits the commission from the Czech government. Hamáček says that the Czech state is interested in Czech products, the producers are however not able to supply millions of masks fast enough. (A7)

The media acted as whistleblowers and investigated the deal. The Czech government was depicted as declining help from Czech businesses and rather turning to external power. The government was identified as a middleman between Chinese power and the Czech people, and the media debate called for its acknowledged responsibility and/or the revision of the deal.

As announced recently by the Minister of Health Adam Vojtěch, the Ministry tried to complain about the low quality of the face masks, but they were not successful. (SZ2)

Minister of Interior Hamáček: Somebody made a mistake in the contract. I can fire somebody, it is not a problem … what is important to me is, that I paid for face masks and that face masks flew into the country. I have all the necessary documents to prove it. (SZ3)

The media argued with third-party analyses to show narratives and counter-narratives. The identified practice was to shame the government and voice a refusal to oblige.

The purchase of face masks from China was closely followed by the media. When – in the course of events it became obvious that face masks are still scarce goods, regardless of the billion Crown investments, the police and justice were called upon to investigate the matter.

The police are trying to uncover the background of purchases of the Ministry of Health, carried out during the state of emergency. … It is long known that Recea Prague ordered goods for 300 million. The fact that we actually paid more than a billion, as Seznam News has pinpointed, was uncovered only recently. (SZ1)

The transaction was shamed across all media platforms as unjustified expenses, dishonest business practices, and costly help. However, these notions emerge within the discourses regarding centralization, (re)distribution, governmentality, and capitalism within the domestic sphere. Simply put, the transaction was shamed for being a bad deal instead of being harmful to society and the Czech people from the symbolic perspective of a debt that accompanies a gift philosophy. At the same time, it was the dispute over the nature of the gift, which triggered off the resistance against the domestic pastor.

This kind of economic reasoning was present in the discourse surrounding the cholera epidemic in Venezuela in the 90s (Briggs Citation2004), suggesting that the narrative tended to reduce to political and economic discourses. Similarly, Colombo (Citation2020) notes that biomedical and economic governmentalities dominate the COVID-19 debate, offering justifications through careful cost-benefit analysis and monetary calculations while excluding the human and social perspective from the discourse. Such reasoning was pervasive in our analysed material as well. There are two possible topics related to homo oeconomicus perspective, as discussed above: biological life and its saving vs. prosperity and economics, that have to step aside for the moment. The Chinese masks saved the first but were a bad deal for the second.

Tightly related to governmentality, centralization, and economic reasoning, bio-power, and pastoral power discourses were apparent. Moreover, the resistance to these powers was evident in criticizing centralized purchase and distribution and voicing distrust of the government and its institutions.

On Monday, the queue (for distributing face masks to healthcare professionals) was 1.5 – 2 km long, and this opportunity did not repeat on Tuesday. So far, our surgery has received three face masks as a gift from Avenier (company) and ten masks from the state. I have no idea if there will be any other rations, so today, I ordered more face masks from a private company on my own. (N3)

As illustrated with the excerpt above, a lack of trust in centralized pastoral care, embodied in the purchase and distribution of the malfunctioning face masks, was compensated with personal strategies avoiding institutional help and relying on private companies. We can observe that the next step after voicing disagreement is to take action privately and to avoid institutional channels altogether. What followed was a massive DIY movement across the country, where households, as well as schools and businesses, began to sew textile face masks and distribute them for free to strategic positions and individuals.

Discussion

Expanding Mauss’ legacy to modern Western societies, Gregory (Citation1982) and Strathern (Citation1988) contributed to the dialogue on gifts with their distinction between gifts and commodities, where gifts occur on the grounds where relationships already exist and therefore – where further action is required, while commodity exchange prepares no such ground. Appadurai (Citation1986) described how material objects fall into our social reality with their particular and unique agency and power, such as the potential life-saving ability of surgical masks in times of a pandemic and given their scarcity worldwide, which makes them exclusive and desirable. Weiner (Citation1992) contributes with the notion of inalienable gifts. In this case, China might have secured the inalienability of the shipment with a notice on each box: “The pandemic will end, but the relationship between Czechia and China will last” (Epidemie skončí, česko-čínské přátelství přetrvá, píše se na krabicích z Čín 2020). Just as partners buy watches and bracelets with personal inscriptions that make the objects practically impossible to re-sell, so did China inscribe the essence of the relationship they wish to maintain for future times, preparing the ground for future action (Strathern Citation1988). The transaction was personalized, thus inalienable and intentionally binding on the side of the supplier. Moreover, the sentence structure referred to national history, similar to Seneca’s poem in Italy or lyrics from a patriotic song in Argentina (Chen Citation2021). In economic science, personalized data-driven economy is an area with much research attention, targeting marketing or consumer behaviour, with the aim to manipulate consumption, increase the share of the market and maximize profits (Dawn Citation2014; Morey and Krajecki Citation2016; Vesanen and Raulas Citation2006). Similarly, other social science disciplines pay much attention to both costs and benefits of personalized data-approach economy, spotlighting the issues such as power abuse and social incoherence, well-illustrated when related to e.g. health and medicine policies (Bhui, Dein, and Pope Citation2021; Gibbon Citation2009; McClean and Moore Citation2013).

For our purposes, it is advantageous to ask questions about the moral justification and ethical motives for each side: China labelling their masks as a gift, Czech people arguing the price was paid and unfairly so. We identified three main discourses forming around the purchase of the face masks: the nature of the gift, resistance towards an external pastor, and resistance against an insufficient internal pastor. The resistance targeted two clusters of subjects that could be called centralized government and China. In this sense, resistance in public discourse was aimed at two influences, inner and outer stimuli. As was already suggested by Foucault (Citation1982) and Heller (Citation1996), resistance does not have to be violent or apparent; instead, forms of resistance can be varied across society.

Besides analysing media, we were also interested in the academic discourse. Although we found only one article in one university news outlet, we found the voices of the academia in the news articles. Dosing knowledge in small amounts, the academic response seems to depend on individual actions instead of a coordinated body of researchers. In this way, the public does not have to visit separate media for expert perspectives; rather, it is the national media that tracks down the selected experts, extracts their knowledge, and presents its synopsis in a readable manner to a layman. On the other hand, the researchers have less control over the final narrative of the articles featuring their names, pictures, and ideas. Homo academicus creates knowledge that is incorporated into articles in popular media without being in full control of its use, misuse, and effects. Likewise, the content of this knowledge is fully controlled by the author of the article, rather than the academic themself. To use a theatre comparison – the author is the director, the screenwriter, the sound master, and the promoter, while the academic is limited to more or less space, presenting a much shortened version of a censored speech.

Drawing upon Mauss (Citation1924), gift theoreticians observe hierarchical machinery underlying gift-giving practices: accepting gifts makes one hierarchically inferior to the creditor, meaning one needs to position as their subordinate (Homans Citation1961). The most expected way to balance the debt is to accept commands from their superiors, whom one never forgives for the degradation and dependency (Emerson Citation1936). In these bonding relationships, receiving a gift means accepting the giver’s worldview and their idea about one’s identity, needs, and desires (Schwartz Citation1967; Steidlmeier Citation1999). Thus, the principles of gift-giving may be used as a tool to gain and maintain status and control. Schieffelin (Citation1980) further develops this idea, claiming that the gift exchange becomes a tool for social obligation and political control by manipulating meaning. He makes a reference to symbolic interactionism, which recognizes an individual interpretation of gifts that has a shared foundation in social meanings. As Rose (Citation1962) suggests, instead of analysing gifts as objects, we should view gifts as situational definitions. The malleable situational fact leaves room for variability in individual interpretations formed based on cultural norms and shared reality. In this sense, a gift becomes a rhetorical gesture of social communication (Schieffelin Citation1980). As argued above, gift-giving can be viewed from the perspective of the process regarding the exchange, formed relationships, and maintained hierarchy independent of the object in question. As demonstrated, Czech reluctance to accept masks as a gift might be viewed as an act of resistance to become subordinate and willing to receive commands from the creditors.

Throughout recent history, we can detect attempts by China to increase its influence via economic routes in Europe (Ji Citation2020; Pepermans Citation2018). Through the lens of moral economy, we can decode subtle hints about what each actor thinks is right and fair in their economic activity. Following the footsteps of Thompson (Citation1971) and his work on the belly rebellion, Scott (Citation1979) and Fassin (Citation2009) see legitimization of economic activity as a product of moral structures. Building on this ground, Wiegratz (Citation2016), views trade, fraud, and other economic activities as integrated into the moral structures of society. A shared moral logic drives each economic act, and it is helpful to analyse how the actors explain, legitimize, and justify their motivations. Pipyrou (Citation2014) shows how the notion of a gift is not excluded from stances and obligations that accompany moral economy, not letting the receiver run free from the gift obligations even in case of a free, anonymous gift. All areas of productivity, including distribution, are based on collaboration, which is rarely equal for all parties involved (Sleeboom-Faulkner Citation2014). In this particular case, the transaction, accompanied by a monetary compensation but nevertheless explicitly labelled a “gift” by the supplier, offers plentiful grounds for analysing the economic act of purchasing surgical masks from the view of perceived legitimacy, morality, and opposing resistance.

Conclusion

What happens when you call a purchase a gift? This paper uncovers the subtle layers in public media discourse surrounding the reception of Chinese face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Czech Republic, together with Italy, Argentina, and some other countries, were chosen by China as strategic partners and as such, they were provided with face masks at the time of its world-shortage, at the state of emergency, at the state of war. The face masks were of low quality and they were paid for, however, the privilege to have some, as opposed to none, was seen by the Chinese government as a “gift” and was articulated as such.

The above mentioned set the scene for the concept of the gift to be accepted, disputed, or even resisted by public media discourse. Conducting a Foucauldian Discourse Analysis according to Willig (Citation2008) and Siena (Citation2023), we have examined written material from the three most popular online news agencies and one topic-related academic blog. Predominant discursive constructions were identified as gift-giving, power, centralization, and resistance. We have discussed them in the theoretical part of the text. Resistance towards malfunctioning internal and external pastors were identified as more general constructions. We present them in the analytical part of the paper. Resistance ranged from attempts to argue and clarify terminology in order to avoid misinterpretation and misrepresentation, to public appeal to shame the national government for being an insufficient pastor, or even rejecting the pastor altogether and providing for oneself through private and DIY channels. Even though the public discourse voiced a clear understanding of the moral and ideological weight of gift-giving practices and the mutual consequences that are created by a gift, economic grounds for resisting the purchase being labelled a “gift” prevailed over the moral opposition to subordination and dependency. Rejection to call the purchase a gift was thus not the end in voicing resistance but rather a means to voicing dissatisfaction with centralized power and insufficient pastoral care from the national government.

Disclosure statements

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kamila Zahradníčková

Kamila Zahradnickova MSc. is an aspiring researcher in the field of anthropology and psychology. Her early academic endeavours focus on dissecting public discourse to identify layers of power, identity, and presented narratives.

Irena Kašparová

Irena Kašparová Ph.D is the Head of Social Anthropology at the Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social Studies, Masaryk University Brno, Czech Republic. She researches and publishes in anthropological theory, as well as ethnography, based upon her fieldwork in Slovakia, Sri Lanka and Czech Republic. She is interested in education, emotions, childhood, ethnicity, tourism and nuance of power.

References

- Antaki, C. 2004. “Analysing Talk and Text. “A Course for the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. http://www-staff.lboro.ac.uk/~ssca1/tthome.htm.

- Appadurai, A. 1986. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Arribas-Ayllion, M., and V. Walkerdine. 2008. “Foucauldian Discourse Analysis.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, edited by C. Willig, 91–108. London: SAGE publications.

- Bhui, K., S. Dein, and C. Pope. 2021. “Clinical Ethnography in Severe Mental Illness: A Clinical Method to Tackle Social Determinants and Structural Racism in Personalised Care.” British Journal of Psychiatry Open 7 (3). https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.38.

- Briggs, C. L. 2004. “Theorizing Modernity Conspiratorially: Science, Scale, and the Political Economy of Public Discourse in Explanations of a Cholera epidemic.“American Ethnologist.” American Ethnologist 31 (2): 164–187. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2004.31.2.164.

- Chen, W. A. 2021. “COVID-19 and China’s Changing Soft Power in Italy.” Chinese Political Science Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-021-00184-3.

- Colombo, E. 2020. “Human Rights-Inspired Governmentality: COVID-19 Through a Human Dignity Perspective.” Critical Sociology 47 (4–5): 571–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920520971846.

- Dawn, S. K. 2014. “Personalised Marketing: Concepts and Framework.” Productivity 54 (4): 370–377.

- Editorial Board. 2021. “Opinion: A New Report Adds to the Evidence of a Coronavirus Coverup in China.“The Washington Post, 5 March: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/a-new-report-adds-to-the-evidence-of-a-coronavirus-coverup-in-china/2020/12/06/81d880f2-366e-11eb-8d38-6aea1adb3839_story.html.

- Emerson, R. W. 1936. Emerson’s essays. Philadelphia: Spencer Press.

- “Epidemie skončí, česko-čínské přátelství přetrvá, píše se na krabicích z Číny.” iDnes, 26 March 2020. https://www.idnes.cz/zpravy/domaci/ruslan-zasoby-cina-zasilka-cesko-cinske-pratelstvi-koronavirus.A200326_101728_domaci_lre.

- Fassin, D. 2009. “Another Politics of Life is possible.” Theory, Culture & Society 26 (5): 44–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276409106349.

- Foucault, M. 1975. Discipline and Punish. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, M. 1976. La Volonte´ du savoir. Paris: Gallimard.

- Foucault, M. 1978. The History of Sexuality: The Will to Knowledge. London: Penguin.

- Foucault, M. 1982. “The Subject and power.” Critical Inquiry 8 (4): 777–795. https://doi.org/10.1086/448181.

- Garrison, C. 2020. “With U.S. Hit by Virus, China Courts Latin America with Medical Diplomacy.“ Reuters, March 26. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-latam-china-featur-idUSKBN21D346.

- Gibbon, S. 2009. “Genomics as Public Health? Community Genetics and the Challenge of Personalised Medicine in Cuba.” Anthropology & Medicine 16 (2): 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/13648470902940671.

- Gregory, C. 1982. Gifts and Commodities. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Academic Press.

- Heller, K. 1996. “Power, Subjectification and Resistance in Foucault.” SubStance 25 (1): 78–110. https://doi.org/10.2307/3685230.

- Hennink, M., I. Hutter, and A. Bailey. 2011. Qualitative Research Methods. London: SAGE publications.

- Homans, G. C. 1961. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Jaworsky, B. N., and R. Qiaoan. 2020. ““The Politics of Blaming: The Narrative Battle Between China and the US Over COVID-19.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 26 (2): 295–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/sll366-020-09690-8.

- Ji, X. 2020. “Conditional Endorsement and Selective Engagement: A Perception Survey of European Think Tanks on China’s Belt and Road Initiative.” Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 28 (2–3): 175–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/25739638.2020.1853453.

- Jørgensen, M. W., and L. J. Phillips. 2002. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: Sage.

- Kendall, G., and G. Wickham. 1999. Using Foucault’s Methods. London: SAGE publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857020239.

- Kowalski, B. 2021. “China’s Mask Diplomacy in Europe: Seeking Foreign Gratitude and Domestic Stability.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 50 (2): 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/18681026211007147.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. 1955. Tristes tropiques. Paris: Plon.

- Lomova, O. 2020. “Respirátory z Číny a PR pro systémového rivala.” Sinopsis, 20 March. Accessed 29 March at: https://sinopsis.cz/respiratory-z-ciny-a-pr-pro-systemoveho-rivala/.

- Marzec, W., and D. Neubacher. 2020. “Civil Society Under Pressure: Historical Legacies and Current Responses in Central Eastern Europe.” Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 28: 1 (1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/25739638.2020.1812931.

- Mauss, M. 1924. “Essai sur la Don, Forme Archaique de l’Echange.” Année Sociologique 1 nouvelle série :30–186.

- McClean, S., and R. Moore. 2013. “Money, Commodification and Complementary Health Care: Theorising Personalised Medicine within Depersonalised Systems of Exchange.“ Social Theory & Health 11 (2): 194–214. https://doi.org/10.1057/sth.2012.16.

- Mediaguru. 2021. “Zpravodajské weby 2020: Na čele Novinky, v TOP 10 i nový web CNN Prima.” Mediaguru, 21 January. https://www.mediaguru.cz/clanky/2021/01/zpravodajske-weby-2020-na-cele-novinky-v-top-10-i-novy-web-cnn-prima/.

- Morey, T., and K. Krajecki. 2016. “Personalisation, Data and Trust: The Role of Brand in a Data-Driven, Personalised, Experience Economy.” Journal of Brand Strategy 5 (2): 178–185.

- Newman, N. 2020. Executive Summary and Key Findings of the 2020 report. Digital News Report. Accessed 6 October at: https://www.digital-newsreport.org/survey/2020/overview-key-findings-2020/.

- Oliver, D. 2021. “Mistruths and Misunderstandings About COVID-19 Death Numbers.” British Medical Journal 372:n352. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n352.

- Pepermans, A. 2018. “China’s 16+1 and Belt and Road Initiative in Central and Eastern Europe: Economic and Political Influence at a Cheap Price.” Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 26 (2–3): 181–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/25739638.2018.1515862.

- Pipyrou, S. 2014. “Altruism and Sacrifice: Mafia Free Gift Giving in South Italy.” Anthropological Forum 24 (4): 412–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2014.948379.

- Rose, A. M. 1962. Human Behaviour and Social Processes: An Interactionist Approach. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Schieffelin, E. 1980. “Reciprocity and the Construction of Reality.” Man 15 (3): 502–517. https://doi.org/10.2307/2801347.

- Schwartz, B. 1967. “The Social Psychology of the gift.” American Journal of Sociology 73 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1086/224432.

- Scott, J. C. 1979. The Rational Peasant. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Siena, M. T. 2023. “A Foucauldian Discourse Analysis of President Duterte’s Constructions of Community Quarantine During COVID-19 Pandemic in the Philippines.” Journal of Constructivist Psychology 36 (1): 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2022.2032503.

- Sleeboom-Faulkner, M. 2014. “The Twenty-First-Century Gift and the Co-Circulation of Things.” Anthropological Forum 24 (4): 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2014.948380.

- Sousa-Pinto, B., A. Anto, W. Czarlewski, J. M. Anto, J. A. Fonseca, and J. Bousquet. 2020. “Assessment of the Impact of Media Coverage on COVID-19-Related Google Trends Data: Infodemiology Study.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 22 (8): e19611. https://doi.org/10.2196/19611.

- Steidlmeier, P. 1999. “Gift Giving, Bribery and Corruption: Ethical Management of Business Relationships in China.“ Journal of Business Ethics 20 (2): 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005960026519.

- Strathern, M. 1988. The Gender of the Gift. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Thompson, E. 1971. ““The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century.” Past & Present 50 (1): 76–136. https://doi.org/10.1093/past/50.1.76.

- van Baal, J. 1975. Reciprocity and the Position of Women. The Netherlands: van Gorcum.

- Vasat, V. 2009. Kritická diskurzivní analýza: Sociální konstruktivismus v praxi. http://www.antropologie.org/cs/pub-likace/prehledove-studie/kriticka-diskurzivni-analyza-socialni-konstruktivismus-v-praxi.

- Védeilhé, A., A. Forget, C. Wang, and C. Pellegrin. 2020. “Coronavirus: Amid a Worldwide Shortage, China Launches ‘Mask Diplomacy.” France 24. 8 April. https://www.france24.com/en/asia-pacific/20200408-focus-coronavirus-china-flaunts-mask-diplomacy.

- Verma, R. 2020. “China’s ‘Mask diplomacy’ to Change the COVID-19 Narrative in Europe.” Europe Journal 18 (2): 205–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-020-00576-1.

- Vesanen, J., and M. Raulas. 2006. “Building Bridges for Personalisation: A Process Model for Marketing.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 20 (1): 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20052.

- Weiner, B. 1992. Human Motivation: Metaphors, Theories, and Research. London: Sage.

- WHO, World Health Organization. 2020. Origins of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus. https://www.who.int/health-topics/corona-virus/origins-of-the-virus.

- Wiegratz, J. 2016. Neoliberal Moral Economy: Capitalism, Socio-Cultural Change and Fraud in Uganda. London: Rowman and Littlefield International. Ltd.

- Wilk, R. 1996. Economies and Cultures: Foundations of Economic Anthropology. CO: Westview Press.

- Willig, C. 2008. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology. London: SAGE publications.

- Wold, S. 2020. “COVID-19 is Changing How, Why and How Much we’re Using Social media.“Digital Commerce 360, 16 September. https://www.digitalcom-merce360.com/2020/09/16/covid-19-is-changing-how-why-and-how-much-were-using-social-media/.

- Zhao, X. A. 2021. “Discourse Analysis of Quotidian Expressions of Nationalism During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Chinese Cyberspace.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 26 (2): 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09692-6.