ABSTRACT

This article explores how practice as research can be a process of inviting in the unknown. In the context of student learning on the Contemporary Performance Practice programme at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, the authors (research-led tutors on the programme) explore performance research and pedagogy, emphasising knowledge as an ongoing, open and embodied process that students can explore and create through their own artistic practices and critical reflections on their practices.

Introduction

In this collaborative co-authored article, we offer a critical-creative discussion of pedagogy and the unknown in the context of student artists developing and carrying out performance research projects. We propose a pedagogy of what we are naming ‘inviting in the unknown’, where student performance-makers are encouraged to enter a space of unknowing in order to become agents in finding and defining practice-as-research for themselves. Drawing on debates around practice-led research that resonate with working with the unknown (Nelson Citation2013; Kershaw Citation2011; Jones Citation2009) and wider philosophical perspectives on the creation of ‘knowledge’ (Ahmed Citation2017; Barad Citation2007; Salami Citation2020; Haraway Citation1991), we argue that this pedagogical approach enables students to develop distinctive research approaches and methods, which can lead to unique engagements with knowledge-generating practices both within and beyond performance studies. Through a mixture of student focus groups, student evaluations and reflections on the module, our own perspectives and experiences as artist-led and research-led teachers, and drawing from wider debates around practice-as-research and pedagogy, we argue that performance practice can uniquely embrace and work with the unknown. Through these processes, performance students can develop distinct research questions and methods which will take their practices in as-yet unknown directions.

In this research process we have followed the suggested path that we offer our students: the identification of research questions, defining our approach and methods, carrying out an ethics process, and undertaking an inquisitive, explorative and embodied process of simultaneously teaching and learning about performance research processes. This article shares our ethical considerations, research enquiries and provides information on the educational context of undertaking research within a conservatoire context, and specifically delivering this Performance Research module to students in their third year of the Contemporary Performance Practice BA (Hons) at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. By discussing the assessment modes and using case studies of student work, we aim to disseminate the expanded and ever-evolving field of performance research, undertaken by those at the forefront of new work. We acknowledge the particular ethical considerations of this research as well as the specificity and limits of this particular offering – we are researching pedagogy through our own teaching and this is a small sample of student work within the context of conservatoire education. We critically reflect on and aim to celebrate the complexities of what it means to treat practice as itself knowledge and thinking, and argue that encouraging students to be in the unknown of their practice, enquiry, and explorations, can allow for unique performance research to emerge.

Research questions

We embarked on this exploration into this module with research questions. These enquiries focused specifically on the Performance Research module (in year three of the programme), on what we wanted to find out about the learning and teaching experience for artists engaging in this process. We asked: how are student artists’ researchers identifying and defining research enquiries relating to and emerging from their own practices? How are each of them engaging with ideas of practice research specific to their own artistic processes? How as tutors can we support a process that necessitates the student to autonomously find their own way? We also connected with larger questions about the epistemology of knowing, about what kinds of knowledge performance-making specifically can provoke: as key practice-as-research theorist Robin Nelson puts it, what is at stake with practice-as-research (PaR) is the capacity for an artistic practice to ‘undertake an inquiry which yields insights of its own’ (Nelson Citation2013, 81). Acknowledging our own positionalities as a white, queer, disabled artist-researcher (Sarah Hopfinger) and a white, Scottish, feminist performance-researcher (Laura Bissell), we were also keen to enter a space of unknowing, to question what knowledge might be and where it can come from, in order to learn from our students and their creative processes. Inspired by Minna Salami’s Sensuous Knowledge, we engage with a critique of traditional euro-patriarchal systems of knowledge and consider how to develop new ways of knowing through the practice of doing and experiential learning. Guided by ecological thinking and inspired by the work carried out by student artists, we argue that performance research can enact what posthumanist thinker Karen Barad proposes; that knowledge is neither fixed nor solid, but always already ‘knowledge-in-the-making’ (Barad Citation2007, 91). With the shared belief that art-making is itself a research process and that student’s performance-making practices are their methodologies, we have framed this module as a creative research space that invites in the unknown to allow new possibilities and understandings of creative practice to emerge. We are aligned with Bruce Barton’s recognition that the field of performance research recognises and establishes ‘sites of connection, juxtaposition, and intersections between consciously diverse approaches to an undeniably diversified field of research’ (Citation2018). We want to attend to the particular kinds of knowledge that performance making can give rise to, and to tease out how those knowledge-making processes can work in the educational degree programme context: how do we teach inviting in the unknown?

Performance research and pedagogy

The Contemporary Performance Practice BA (Hons) programme (CPP) at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland is an interdisciplinary performance-making degree which aims to develop socially engaged artists who can make a contribution in the world as performance-makers, educators, advocates and active citizens. The third year of study on the CPP programme is called ‘The Researching Artist’ and the Performance Research module involves students carrying out their own performance research projects. There are diverse modes through which the students disseminate their PaR, including a performance lecture, demonstration or installation of practice, and written submission that includes critical reflection on their practice. A development of the Dissertation module, where the focus was on the written element, Performance Research instead foregrounds the process of research and the creativity that this allows artist-researcher students. We propose that it is in emphasising the process of research – similarly to how we emphasise the process of performance-making throughout the degree programme – that the Performance Research module enables students to not only invite in the unknown through initiating an enquiry but they are also able to, as it were, spend time in and inhabit the unknown of their enquiry through engaging in creative practice. It is in this process of being with(in) the unknown that students can develop, understand and articulate their artistic practices in new and unexpected ways. The emphasis is placed on the alive-ness and emergence of each student’s creative praxis, where their research question and methods can emerge from their embodied experiences and intuitions of practice. Informed by pedagogue bell hooks’ encouragement of risk-taking and critical thinking (1994), this module aims to encourage reflexivity, whereby students can embrace the vitality of, as well as reflect on and bring critical attention to the politics of, their practices.

Research in a conservatoire context

Barton acknowledges some of the anxieties around institutional validation of performance research processes, what he refers to as artistic-research in performance (ARP), and suggests that the relationship between artistic practices and the conventions of academic contexts has been historically fraught. While some HEIs such as universities have academic conventions surrounding research methods, methodologies and outputs, they also have an embedded, resourced and established research culture. Small specialist institutions usually have far less staff (and a much higher proportion of part-time hourly-paid staff due to the nature of the learning environment and smaller numbers of research-active staff overall) and frequently there is a less-established culture of research due to the aim of providing vocational training in the performing arts. With more contact time with students and a focus on excellence in teaching and highly-skilled training, the emphasis has been on the learning and teaching environment for the performance artists, musicians, dancers, film-makers and production managers and designers of the future. Despite the perception that conservatoires might be less research-driven than universities, undertaking performance research in a conservatoire has its benefits in that creative practice is at the heart of the learning environment. Because of this, the vast majority of the research is practice-based and it can also be fertile ground for interdisciplinary artistic research and collaboration. One of our ambitions of this research project is not only to disseminate the kinds of performance research that is happening in the context of our conservatoire, but also through the module to expand it and grow the research culture from within. Another aim of this research (as with many evaluative processes) is to continue to improve the student experience of the learning environment that we are creating and curating.

Ethical challenges and processes

We applied for ethical approval for this research via the Ethics Committee at RCS. This was an essential part of the project, and we also hoped that by going through own research considerations we were able to model an ethical research process to students and to expose some of the ways of working and research methods – such as focus groups – that we discuss throughout the module. For our research there were several ethical risks and challenges, which demanded specific processes to be put in place:

The key ethical risk of working with students was that they could feel that their participation would have an impact on their learning or assessment on the module. Participating students completed a consent form and were given an information sheet, prior to taking part in the research. We indicated at the outset that participation was voluntary and the information sheet explicitly states that participation will have no bearing on student grades or assessment. In order to emphasis this, any evaluations or focus groups took place after assignments and assessments were completed for the module, out with official class times, and were attended optionally by students.

Participation in the research was entirely voluntary for students and their participation could be withdrawn at any point. We were careful as tutors and researchers to put no pressure on students to participate. As there were two of us delivering the module and carrying out the research, students could speak to either one of us if they had an issue with any part of their participation in the project should they wish to. As with all CPP modules, Performance Research was risk assessed in accordance with RCS procedures.

We documented and captured some of the outputs at the Research in Process event (where students present their performance lectures and demonstration or installation of practice) and at the end of the module, we gave students anonymous evaluation forms to try to ascertain how their learning in this module had developed, what their understanding of performance research was by the end of the module, and what performance research can offer their arts practice. We also conducted a voluntary focus group at the end of the process. Using semi-structured interview questions we used this focus group to get more in-depth and specific experiences of the module and we asked permission to record this. We use excerpts of transcripts of the focus group in this article.

When writing this article the consideration of anonymity has been key, especially since the work we refer to by students is intimate and often personal. The institution is named and images of student work is also used. All student contributions from the focus groups have been anonymised by using references to ‘student A’, ‘student B’ etc. throughout. We have selected images that do not show the student artists in an easily recognisable way, and we have sent this article to each participating student with their contributions and images included. We have kept all contributions and evaluations from students anonymous. We reiterated both before and after the focus groups that their contributions could be withdrawn at any point.

Practice as research

A PaR methodology forms the basis of the module. Whilst students may research a new aspect of their practice, we encourage them to develop their research questions in response to ideas and questions that have emerged from their experiences and reflections on their own practice: that is, from the outset, we wish to treat performance as a practice that can contain and create knowledge and critical thinking. By inviting them to consider what is alive and urgent for them within their art-making practice students can self-identify a working question to frame their process. In the early stages, they attend a range of research methods sessions and have weekly one-to-one tutorials with their supervisor as well as opportunities to share practice and gain peer and tutor feedback. All students are asked to consider the ethical considerations of their work and those of them working with participants or vulnerable groups submit applications to the RCS Ethics Committee. In working with practice as the main research methodology, the module enables students to engage with the complexity and nuances of what knowledge is and where knowledge is located: it allows students to question dominant assumptions that knowledge is only located in academic and theoretical writing. This is an assumption that many students still carry when beginning the module: student feedback from the focus group implied that they associated the term ‘research’ predominantly with writing – two of the student participants commented on how the module seemed ‘so new’ to them at first, as if they were doing something different to what they had previously experienced on the programme. These assumptions may be unsurprising when considering the ambiguous position PaR still has in academia.

In the UK PaR genealogies can be traced to at least the 1960s, emerging as part of the ‘performative turn’ or ‘practice turn’ that has taken place across a range of arts and humanities disciplines (Kershaw Citation2011, 63). However, PaR in theatre and performance has only gained substantial recognition in British universities since the 1990s (Nelson Citation2013, 4; Kershaw Citation2009, 1–2). Despite being acknowledged by the sector’s research agencies and processes – PaR is funded via the AHRC and evaluated as part of HEFCE’s Research Assessment Exercises (RAE) and Research Excellence Framework (REF) – Nelson has proposed that it does not currently enjoy a wholly respected position within the academy. He suggests that it remains for some a rather elusive and/or incomprehensible mode of research (Nelson Citation2013, 4). Anxiety towards PaR is predominantly due to the ambiguity this methodology poses in terms of where ‘research’ and ‘knowledge’ can be located, and what constitutes their dissemination. By proposing that research process and findings can be embedded within the artistic practice itself, PaR implicitly disrupts institutional structures of presenting and evidencing research. Furthermore, the instabilities and impermanence of theatrical performance pose direct challenges to the long-standing notion of fixed knowledge taxonomies. Since performance is largely a live as well as ephemeral activity, it also challenges the notion of ‘reproducibility’, which is something that has been upheld by ‘the academy for the past 550 years via mechanically reproducible writing’ (Piccini and Rye Citation2009, 42). Therefore, PaR variously challenges traditional conventions of research enquiry and presentation. For us, is it is these very difficulties and complexities that make PaR a rigorous and robust research approach: an approach that the Conservatoire context is well placed to develop.

By proposing artistic practice as research methodology, PaR troubles the traditional Western binary between ‘practice’ and ‘theory’, between ‘making’ and ‘studying’ something (Nelson Citation2013, 19; 16). With the Performance Research module, we aim to encourage a productive troubling of these binaries. In emphasising performance as the principal research methodology, knowledge is understood from the outset as something that is emergent across theory and practice: this is reflected in the diversity of assessment modes (as already outlined). What is key to our pedagogy is that PaR enables students to become more aware of how their artistic practices are, in themselves, knowledge-generating practices, where knowledge within and beyond performance can emerge through the (often surprising and unpredicted) enactments of their artistic practices.

Research in process event

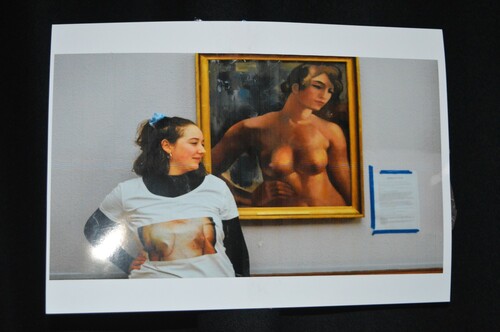

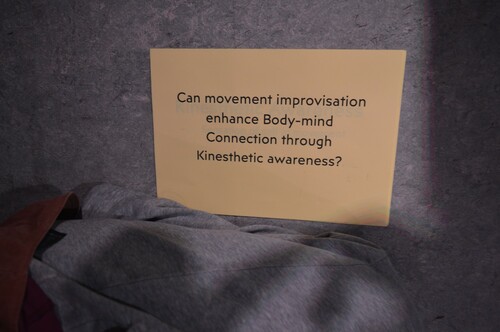

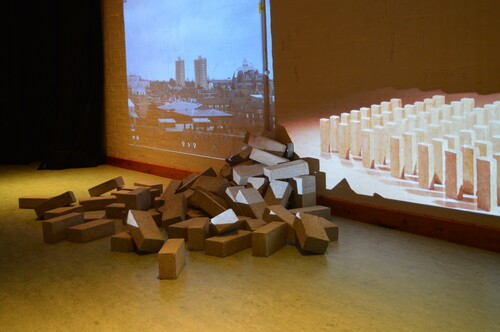

Around halfway through the ten-week Performance Research module there is a Research in Process event where students deliver a 20-minute performance-lecture and share a demonstration of their practice. This can take many forms: a live performance, workshop, installation, or any other creative demonstration of practice. It is shared with an invited audience. Nelson describes a PaR approach as one in which the ‘products’ of artistic practice are presented as a key instance of the research findings and dissemination (Citation2013, 8–9). These demonstrations of practice were varied and included a range of performative methods to both illustrate and disseminate their individual research project. Four out of the ten students in the class engaged in our evaluation of the module for this research paper. The dissemination of these research projects at the Research in Process event included: a student artist (A) exploring solo performance practices in relation to non-present beings and wider systems, and she delivered a performance lecture and performance against the backdrop of two choreographic films made in London. This artist used breeze blocks to signify the bodies of those who died in the Grenfell Towers fire in 2017 and, in one film built an unstable tower out of them (which eventually crumbled) and in the other film stood precariously at the edge of a building while her live naked body lay amongst the fallen bricks in the performance space. Another student artist (B) shared a series of films he had made with his collaborator exploring fat, queer choreography and delivered a performance lecture remotely from the RCS. Another student artist (C) combined the performance-lecture and demonstration of practice into one long session through a physical workshop exploring the concept of ‘flow’ through embodiment and somatic practice. The fourth student (D) shared a performance lecture about a protest at Kelvingrove art gallery where the artist arranged a sit-in of women wearing t-shirts with images of mastectomy scars as part of her research into feminist activism and female body image after breast cancer. In the installation space, she showed a diptych of films about the project and displayed the t-shirts they had worn for the protest ( of student Research in Process work).

Figure 1. (Student D) is an image of a performance installation, containing white T-shirts with images of breasts that have been through mastectomy surgeries printed on them. There is a painting propped up on an easel of a naked woman in the background. There are dark curtains at the back.

Figure 2. (Student D) shows a young white woman with her blonde hair tied back, who is wearing a white T-shirt with an image of breasts that have been through mastectomy surgery printed on it. She is posing in a way that imitates a painting behind her – the painting is of the top half of a naked woman with both breasts.

Figure 3. (Student C) shows an image from, cardboard square that says ‘Can movement improvisation enhance Body-mind Connection through Kinesthetic awareness?’.

Figure 4. (Student C) shows two projected images on a white brick wall in a studio with the backs of the audience visible in the foreground. The projected images are moments from video projections of various people moving in a studio dance workshop.

Figure 5. (Student A) shows two large projected images on a wall – firstly, a number of bricks placed in rows and, secondly, a video projection overlooking London near Grenfell Tower. In front of the projections are a pile of bricks placed as though they are rubble.

Figure 6. (Student A) shows two large projected images on a wall. Firstly, a number of bricks placed on top of each other with the performer (a white young woman wearing black shoes and shorts and a cream crop top) placing bricks on top of each other with one brick falling from the top of the tower. Secondly, a video projection overlooking London near Grenfell Tower. In front of the projections are a pile of bricks placed as though they are rubble, and the performer lies naked live in the space on her side with her back to the audience.

Written submission

The Research in Process event is at the midpoint of the process and provides an opportunity to get feedback and questions from a live audience. At the end of the module, students submit a 5000 word written submission formatted to the CPP presentation guidelines. Prior to submission, there is a draft deadline and then students get extensive feedback from their supervisor, redraft their work and engage in a peer-review process prior to submission. This is directly modelled on the academic publishing context and students have two of their peers review their work, offer feedback, and then they submit details of how they responded to the feedback along with their final submission. By mirroring these real-world processes of academic publishing (and running a workshop on Writing for Publication at the end of the academic year), our aim is that students who wish to submit their work to journals, edited collections or for symposium events have the understanding and tools to be able to do this. As with all of the work developed on the programme, we hope that it will have a life beyond the classroom and a wider audience beyond our community.

A key aspect of their written submissions is how each student critically reflects on their practice. One student reflected on the value of this redrafting process and how having to return to their own reflections on their practice was useful in developing their articulation abilities:

… when I was writing my first draft … I just couldn’t word it … it just sounded really rubbish … I was thinking about a conversation me and [a fellow student] had … about when you know something really well you can say it really clearly [but] if it is taking you several sentences and lots of long words to explain it maybe you don’t know it that well? … I got to a point where I realized that I don’t need to sound clever … I [need to] explain it clearly.

With PaR, documentation – films, images and reflective notes – are sometimes used in the place of the artworks in order to fully evidence the research inquiry and findings (Nelson Citation2013, 5; Piccini and Rye Citation2009, 36). With the student cohort, there was a mixture of live performance and documentation of performances that were made during the research process, so students used a mixture of embodied practice and documentation of past performance experiments. Since it is the actual doing of performance that the students’ research seeks to explore and elucidate, it does not make sense to treat the documentation as though it can fully stand in for the performance practices themselves. What is distinctive about research that is PaR, is that the research emerges from artistic practice, is carried out using that practice as the principal methodology and is (in part) evidenced through the products of that practice. We think artistic practice can explore questions that other methodologies cannot, wherein PaR is predicated on the unique type of research inquiry an artistic practice can instigate and enact, and is underpinned by the distinct kinds of knowledge which that practice can produce. What becomes key, then, is of course the demonstration of practice but also the creative methods that students use to present their documentation, and the extent to which they are able to critically reflect on their practice in their written work. The diverse student projects, and multiple ways in which students chose to disseminate their research, reflects the complexity of the wider field of PaR. There are varying perspectives within the PaR field of what it means for performance practice to itself be a theorising and thinking activity, producing what Estelle Barrett calls ‘knowledge or philosophy in action’ (Barrett Citation2007, 1).

Praxis

As already discussed, initially we ask students to negotiate and develop their research question by critically reflecting on their own practice: as part of this process, we invite them to consider the range of practices and projects they have experienced in their studies so far, which spans autobiographical performance, collaboration, devising, performance in education and multiple approaches to social practice. We have found that this emphasis on their practice, and what they are concerned with as artists and human beings, means that their research interests emerge from within the artistic practices themselves. Brad Haseman points out that this negotiation is typical of a PaR approach – creative practice itself initiates the research inquiry (Citation2007, 147). Baz Kershaw suggests that artist-researchers tend to ‘encounter hunches’ from within their professional artistic practices and that it is these that form the starting points for their research (Citation2011, 65). Student C reflected on the importance of ‘being confident in that gut feeling’. By articulating the what of their research – the question or enquiry – students are then encouraged to propose how they will go about carrying out that research. Our experience of teaching the module is that students often struggle to define what their methods will be, even when they have a clear research question: whilst the PaR methodology is clear from the outset, the specifics of their performance methods are hard to define, and often change through the process. Student D who was exploring performance as protest remembered how they ‘definitely had a lot of trial and error in my performance making and the protests’. This relates to two distinctive qualities of PaR: firstly, since the approach is particular to each artist-researcher the methods are inherently diverse (Kershaw Citation2009, 4); and, secondly, since the methods unfold through the process of the research, they are always emergent and cannot be fully defined prior to the research process (Barrett Citation2007, 6). This process of honing and specifying the research through the actual process of doing the research is, as Nelson points out, similar to all methodologies and disciplines (Citation2013, 30). What is perhaps most unique about PaR, and how our students tend to approach their research, is that the artist-researcher discovers their enquiry through embodied practice and then carries out their research chiefly through embodied practices, where they are themselves inside their research. Knowledge is, therefore, not treated as something we can objectively discover or create, rather knowledge is embodied and located: it emerges through the actualities of doing, and from reflecting on that doing. As Lynette Hunter indicates: ‘In the arts, situated knowledge becomes a situated textuality, knowledge always in the making, focusing on the process but situated wherever it engages an audience’ (Citation2009, 152). When asked what worked well in the module, one student reflected:

… knowing that there is not one way to do it so feeling ok to go with … your way of doing it … that your interest is enough to know more … There are things that are unclear, but being confident in that gut feeling … The academic is not just for certain people … it is not about doing it in a certain way … there is more you in it.

So, a key aspect to how we use and conceptualise ‘performance’ in this module is that doing performance can be a mode of theorising about performance; that making performance can be a mode of studying it. Performance-making can be a process of discovering, changing and developing the methods of practice through the doing of that performance-making – or, as Karen Christopher wrote about Goat Island’s methodology, by working in the unknown the performance material itself ‘begins to suggest certain directions’ and thus the performance begins to ‘make itself’ (Christopher in Bottoms and Goulish Citation2007, 120). Students used words such as ‘unclear’, ‘lost’, and ‘new’ when reflecting on aspects of being in the process of their research, implying their own experiences of being in the unknown. In this way, performance research could be understood to be predicated on its lack of fixed methodology. Simon Jones’ insights resonate with this idea: he argues that, what is needed with PaR, is not the courage of practitioner-researchers to predict and convict their practices, but rather ‘the courage of their lack of convictions’ (Citation2009, 22, italics in original). He proposes that PaR must resist ‘coming to know a practice apparently once and for all time’ (Citation2009, 22). We propose that it is, in part, by embracing the unknown and emergent nature of creative practice that PaR can be generative of new thinking and doing, and can produce new knowledge and insight. This approach of embracing the unknown and emergent necessarily involves an openness to the muddles and messiness of creative practice. Indeed, student C described ‘being in a bit of a puddle’ of not knowing what she was doing. Cyberneticist and ecological thinker Gregory Bateson, through his ‘metalogues’, emphasises the importance of muddle and messiness: he suggests that ‘if we … spoke logically all the time, we would never get anywhere … [and] in order to think new thoughts or to say new things, we have to break up all our ready-made ideas and shuffle the pieces’ (Citation1972, 25). Bateson implies that thoughts, ideas and findings emerge through allowing ourselves to be in the ‘messiness’ of the unknown. Students commented on discovering new ideas and understandings about their practices through their performance research. One student reflected:

… [Before this module] I felt quite stuck in autobiographical work because I felt that was all I knew [but] through this module, its completely changed … my work doesn’t feels as trapped in the autobiographical, it doesn’t have to be about my life, it has completely opened up … I feel a bit more freed in my practice … [In the next module of my third year] I have carried on this wave of interviews and speaking to other people about an experience that I don’t know … Something I have kept from my research project … is talking and listening … working with people to tell their narratives but in my way, or representing someone else’s life through my body.

Creative-critical reflections

I am sitting in a supervision tutorial with one student. She is stuck. She is not sure what the focus of her research is – it is something about statistics and how performance can bring us closer to the actuality of people than statistics can. But she does not know what field her practice research sits within. I am tempted to re-articulate her enquiry for her, to place it into a clear field – participatory performance. I do not speak though. Something tells me I need to let her – and myself – sit with this not knowing. Though it is week three and she ideally would know by now what she is researching. A week later we are back in the room having a tutorial. She tells me she has realised this is not about participatory performance, she wishes to make solo performance that attempts to ‘hold’ other bodies – the impossibility of this is interesting to her. She has been doing some practice experiments – she went to her home city and filmed herself attempting to connect with the tragedy of Grenfell Tower, a place near her home. It was only from doing her practice that she was able to find her research enquiry more clearly. She wished to research the field of solo performance and live art, to explore how solo performance can connect with ‘nonpresent’ bodies and wider political ideas. If I had given into my urge to place her research in the particiaptory performance field the previous week – my discomfort of the unknown had nearly led me to this – then I do not think she would have found this exciting, and what came to be a unique and impressive performance research project. For this student, I had needed to not speak, not suggest, not give a structure. But this was not the case with every student.

[When writing] I didn’t feel like I could find [the structure], and I really wanted to feel free and take on this approach Sarah and I talked about that things will come when you are engaged in it. So for me, it didn’t really work … I needed a structure way earlier than I had it … I don’t know how you do that with the tutor – how can you know that I need that? … The fact that we were able to meet up with you once a week and be encouraged in what we were doing … it reassured me to keep going. And the positive feedback and your approaches to tutorials also helped me … But there is also something about letting students find their own way, but some of us need more structure.

I am sitting in a supervision tutorial with another student – their research is about how to find ‘flow’ in dance practice, where the dancer can follow the ‘flow’ of movement, as opposed to a structure of choreography. Since her research is about creating ways for unstructured flow to happen through movement, I reflected back to her that perhaps her research process was like this too. She had been telling me how lost she felt, how unclear she felt about her research. I thought it may help and reassure her to follow the process by me reflecting back her research enquiry into flow in terms of how she went on the research process. But towards the end of her process, whilst she presented and wrote a very strong piece of research, I realised that really I needed to have provided or suggested more structure. In order to contain this research that was focused on the unstructured and improvised – on flow and intuition – this student needed, more than ever, to have structure and holders to work with. In order for this student to be more productively in the unknown of her research, she needed more known structures.

For me, as a supervisor, I am realising the importance of the diversity of what different students – and/or different research enquiries – need, where ‘inviting in the unknown’ needs to be facilitated differently for different projects and learning styles. Just as knowledge is always ‘knowledge-in-the-making’ (Barad Citation2007), so is the knowledge-making methods always in the making, where different students encounter knowledge differently, depending on their research enquiries and learning styles. How do I, as a supervisor, listen to the different students and their work, where one approach for one student may not work for another? For me, I need to ‘invite in the unknown’ of the diverse students I work with each year, not presupposing what will work or not work. So, pedagogy for me in this respect emerges less as a specific approach and more as an approach of un-knowing, of opening up to being surprised by what each student, and student research project, needs from me as a mentor.

My approach to mentorship and supervision has always been to ask what I hope are useful questions in order for the student to try to understand their own work better. I avoid passing comment or judgement on the performance research work they share and rarely offer suggestions of a particular artistic path to follow. My ambition in doing this is that the student can find their own way into the unknown, and that my questions are a way of them reflecting on their own artistic practice and the choices they are making. I hope that my questions offer a way of seeing their own artistic process through the eyes of another, and that in doing this, they can understand their enquiry, process and the performance they are making through a new set of eyes. I will not be there when they graduate in order to tell them what to do or make or think. But what I can do is provide them with a process of enquiry, of critical reflection, an invitation to care and consider and grapple with what they are doing until they can find their own way.

And this process is generative and rich for me too. I am on the journey with them and through this my ideas and understandings of approaches and methods are constantly expanded and evolving.

Conclusion: inviting in the unknown

In this article, we have explored the potential of practice-as-research approaches in the context of the Contemporary Performance Practice undergraduate programme at Scotland’s national conservatoire. We have outlined the module and suggested the ways in which it accounts for the complexities of what it means to treat practice itself as knowledge and thinking. We have proposed that allowing for students to be in the unknown of their practice, enquiry, and explorations, evokes unique performance research, where new insights about their own practices can emerge.

One unexpected aspect of learning that has become visible through doing this research into teaching Performance Research, is the potential for PaR to be inclusive of a wider diversity of students. One student reflected on her relationship to Higher Education as a working-class person:

I was super worried going into this project … it is psychological [and about] confidence … I feel if you are a working-class student … as soon as I heard language which I didn’t understand it was like: why am I here? … [I would think] I don’t really deserve to be at uni … because I am not at this level. So why your classes were so incredible for me … they really allowed me to feel comfortable and really calm, to shush any anxieties … There was no language that was not explained … In the lesson we were told this is difficult, we were told if you are confused or lost verbalise this. For me that calmed me so much and it didn’t allow me to sit and panic on my own … I was literally able to … reflect back on what the teachers had given us and think this is how I can put this back on my project.

My practice as a methodology allowed me to be able to articulate to the non-performers I was working with … what I was doing, who I was and what my intention was … It gave me so much more confidence to articulate my arts practice … I didn’t feel like a student … for me as a neurodiverse artist … if I just kept it to research which was quite normative, it wouldn’t have brought me to the end thing that I created, it would not have been the same process. [Doing practice] really made me understand what I need in an arts process, which is engagement.

I find myself remembering stuff and understanding stuff [later on when doing my movement practice] that I was learning over [the research methods] sessions … I know when stuff pops up in my head that I have learned earlier that it is there, I understood something and [now] my body is ready to apply it. Sometimes I need to have a bit of patience … it is ok not to get it over that project … almost everything in the [research methods] sessions was new to me, it was new knowledge, and maybe that is one of the reasons why it is only later it has been formed and cooked!

With many thanks to the Performance Research students who participated in this research project. All images by Holly Worton.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sarah Hopfinger

Sarah Hopfinger is an artist, researcher and lecturer, who works across live art, choreography, queerness, crip practice, intergenerational collaboration, and ecology. Sarah’s performance and research work has been presented nationally and internationally. Her current research project, Ecologies of Pain, is supported by a Carnegie Trust Research Incentive Grant.

Laura Bissell

Laura Bissell is a performance researcher, academic and writer whose research interests include: live art; technology and performance; feminist performance; ecology and performance; and performance and journeys. Laura is co-editor of Performance in a Pandemic (Routledge, 2021) and Making Routes (Triarchy, 2021).

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2017. Living a Feminist Life. London: Duke University Press.

- Arlander, Annette, Bruce Barton, Melanie Dryer-Lude, and Ben Spatz. 2018. Performance as Research: Knowledge, Methods, Impact. London: Routledge.

- Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Barrett, Estelle. 2007. “Introduction.” In Practice as Research, Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry, edited by Estelle Barrett Barbara, and Barbara Bolt, 1–13. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bateson, Gregory. 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Northvale: Jason Aronson Inc.

- Bottoms, Steven, and Matthew Goulish. 2007. Small Acts of Repair: Performance, Ecology and Goat Island. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Fleishman, Mark. 2012. The Difference of Performance as Research. Theatre Research International, 37(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0307883311000745.

- Haraway, Donna. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Haseman, Brad. 2007. “Rupture and Recognition: Identifying the Performative Research Paradigm.” In Practice as Research, Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry, edited by Estelle Barrett Barbara, and Barbara Bolt, 147–157. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hunter, Lynnette, and Shannon Rose Riley. 2009. Mapping Landscapes for Performance As Research. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jones, Simon. 2009. “The Courage of Complementarity: Practice-as-Research as a Paradigm Shift in Performance Studies.” In Practiceas-Research in Performance and Screen, edited by Ludivine Allegue, Simon Jones, Baz Kershaw, and Angela Piccini, 18–32. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kershaw, Baz. 2009. “Practice-as-Research: An Introduction.” In Practiceas-Research in Performance and Screen, edited by Ludivine Allegue, Simon Jones, Baz Kershaw, and Angela Piccini, 1–16. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kershaw, Baz. 2011. “Practice as Research: Transdisciplinarity Innovation in Action.” In Research Methods in Theatre and Performance, edited by Baz Kershaw, and Helen Nicholson, 63–85. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Nelson, Robin. 2013. “Robin Nelson on Practice as Research.” In Practice as Research in the Arts, Principles, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances, edited by Robin Nelson, 1–114. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Piccini, Angela, and Caroline Rye. 2009. “Of Fevered Archives and the Quest for Total Documentation.” In Practiceas-Research in Performance and Screen, edited by Ludivine Allegue, Simon Jones, Baz Kershaw, and Angela Piccini, 34–49. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Salami, Minna. 2020. Sensuous Knowledge: A Black Feminist Criticism for Everyone. London: Zed Books.